#Ancient Historiography

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note about periodization

I am going to start describing time periods in Chinese history with European historical terms like medieval, Renaissance, early modern, Georgian and Victorian and so on, alongside the standard dynastic terms like Song, Ming and Qing I usually use. So like something about the Ming Dynasty I will tag Ming Dynasty and Renaissance. I already do it sometimes but not consistently. Here’s why.

A common criticism levied against this practice is that periodization is geographically specific and that it’s wrong and eurocentric to refer to, say, late Ming China as Renaissance China. It is a valid criticism, but in my experience the result of not using European periodization is that people default to ‘ancient’ when describing any period in Chinese history before the 20th century, which does conjure up specific images of European antiquity that do not align temporally with the Chinese period in question. I have talked about my issue with ‘ancient China’ before but I want to elaborate. People already consciously or subconsciously consider European periodizations of history to be universal, because of the legacy of colonialism and how eurocentric modern human culture generally is. By not using European historical terms for non-European places, people will simply think those places exist outside of history altogether, or at least exist within an early, primitive stage of European history. It’s a recipe for the denial of coevalness. I think there is a certain dangerous naivete among scholars who believe that if they refrain from using European periodization for non-European places, people will switch to the periodization appropriate for those places in question and challenge eurocentric history writing; in practice I’ve never seen it happen. The general public is not literate enough about history to do these conversions in situ. I have accumulated a fairly large pool of examples just from the number of people spamming ‘ancient China’ in my askbox despite repeatedly specifying the time periods I’m interested in (not antiquity!). If I say ‘Ming China’ instead of ‘Renaissance China’ people will take it as something on the same temporal plane as classical Greece instead of Tudor England. How many people would be surprised if I say that Emperor Qianlong of the Qing was a contemporary of George Washington and Frederick the Great? I’ve seen people talk about him as if he was some tribal leader in the time of Tacitus. European periodization is something I want to embrace ‘under erasure’ so to say, using something strategically for certain advantages while acknowledging its problems. Now there is a history of how the idea of ‘ancient China’ became so entrenched in popular media and I think it goes a bit deeper than just Orientalism, but that’s topic for another post. Right now I’m only concerned with my decision to add European periodization terms.

In order to compensate for the use of eurocentric periodization, I have carried out some experiments in the reverse direction in my daily life, by using Chinese reign years to describe European history. The responses are entertaining. I live in a Georgian tenement in the UK but I like to confuse friends and family by calling it a ‘Jiaqing era flat’. A friend of mine (Chinese) lives in an 1880s flat and she burst out in laughter when I called it ‘Guangxu era’, claiming that it sounded like something from court. But why is it funny? The temporal description is correct, the 1880s were indeed in the Guangxu era. And ‘Guangxu’ shouldn’t invoke royal imagery anymore than ‘Victorian’ (though said friend does indulge in more Qing court dramas than is probably healthy). It is because Chinese (and I’m sure many other non-white peoples) have been trained to believe that our histories are particular and distant, confined to a geographical location, and that they somehow cannot be mapped onto European history, which unfolded parallel to the history of the rest of the world, until we had been colonized. We have been taught that European history is history, but our history is ethnography.

It should also be noted that periodization for European history is not something essentialist and intrinsic either, period terms are created by historians and arbitrarily imposed onto the past to begin with. I was reading a book about medievalism studies and it talked about how the entire concept of the Middle Ages was manufactured in the Renaissance to create a temporal other for Europeans at the time to project undesired traits onto, to distance themselves from a supposedly ‘dark’ past. People living in the European Middle Ages likely did not think of themselves as living in a ‘middle’ age between something and something, so there is absolutely no natural basis for calling the period roughly between the 6th and 16th centuries ‘medieval’. Despite questionable origins, periodization of European history has become more or less standard in history writing throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, whereas around the same time colonial anthropological narratives framed non-European and non-white societies, including China, as existing outside of history altogether. Periodization of European history was geographically specific partially because it was conceived with Europe in mind and Europe only, since any other place may as well be in some primordial time.

Perhaps in the future there will develop global periodizations that consider how interconnected human history is. There probably are already attempts but they’re just not prominent enough to reach me yet. Until that point, I feel absolutely no moral baggage in describing, say, the Song Dynasty as ‘medieval’ because people in 12th century Europe did not think of themselves as ‘medieval’ either. I am the historian, I do whatever I want, basically.

#I was watching an unrelated video about dnd worldbuilding#and out of nowhere someone in the comment section called 1300s chinese people 'ancient asians'#*facepalm*#so I was reminded of this again#rant#colonialism#orientalism#chinese history#historiography

927 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see you talk a lot about historiography! What would you consider the most important development of Alexander’s historiography?

What the Hell is Historiography? (And why you should care)

This question and the next one in the queue are both going to be fun for me. 😊

First, some quick definitions for those who are new to me and/or new to reading history:

Historiography = “the history of the histories” (E.g., examination of the sources themselves rather than the subject of them…a topic that typically incites yawns among undergrads but really fires up the rest of us, ha.)

primary sources = the evidence itself—can be texts, art, records, or material evidence. For ancient history, this specifically means the evidence from the time being studied.

secondary sources = writings by historians using the primary evidence, whether meant for a “regular” audience (non-specialists) or academic discussions with citations, footnotes, and bibliography (sometimes referred to as “full scholarly apparatus”).

For ancient history, we also sometimes get a weird middle category…they’re not modern sources but also not from the time under discussion, might even be from centuries after the fact. Consider the medieval Byzantine “encyclopedia” called the Suda (sometimes Suidas), which contains information from now lost ancient sources, finalized c. 900s CE. To give a comparison, imagine some historian a thousand years from now studying Geoffry Chaucer from the 1300s, using an entry about him in some kid’s 1975 World Book Encyclopedia that contains information that had been lost by his day.

This middle category is especially important for Alexander, since even our primary sources all date hundreds of years after his death. Yes, those writers had access to contemporary accounts, but they didn’t just “cut-and-paste.” They editorialized and selected from an array of accounts. Worse, they rarely tell us who they used. FIVE surviving primary Alexander histories remain, but he’s mentioned in a wide (and I do mean wide) array of other surviving texts. Alas this represents maybe a quarter of what was actually written about him in antiquity.

OKAY, so …

The most important historiographic changes in Alexander studies!

I’m going to pick three, or really two-and-a-half, as the last is an extension of the second.

FIRST …decentering Arrian as the “good” source as opposed to the so-called “vulgate” of Diodoros-Curtius-Justin as “bad” sources.

Many earlier Alexander historians (with a few important exceptions [Fritz Schachermeyr]) considered Arrian to be trustworthy, Plutarch moderately trustworthy if short, and the rest varying degrees of junk. W. W. Tarn was especially guilty of this. The prevalence of his view over Schachermeyr’s more negative one owed to his popularity/ease of reading, and the fact he wrote on Alexander for volume 6 of the first edition (1927) of the Cambridge Ancient History, later republished in two volumes with additions (largely in vol. 2) in 1948 and 1956. Thus, and despite being a lawyer (barrister) not a professional historian, his view dominated Alexander studies in the first half of the 20th century (Burn, Rose, etc.)…and even after. Both Mary Renault and Robin Lane Fox (neither of whom were/are professional historians either), as well as N. G. L. Hammond (with qualifications), show Tarn’s more romantic impact well into the middle of the second half of the 20th century. But you could find it in high school and college textbooks into the 1980s.

The first really big shift (especially in English) came with a pair of articles in 1958 by Ernst Badian: “The Eunuch Bagoas,” Classical Quarterly 8, and “Alexander the Great and the Unity of Mankind,” Historia 7. Both demolished Tarn’s historiography. I’ve talked about especially the first before, but it really WAS that monumental, and ushered in a more source-critical approach to Alexander studies. This also happened to coincide with a shift to a more negative portrait of the conqueror in work from the aforementioned Schachermeyr (reissuing his earlier biography in 1973 as Alexander der Grosse: Das Problem seiner Persönlichtenkeit und seines Wirkens) to Peter Green’s original Alexander of Macedon from Thames and Hudson in 1974, reissued in 1991 from Univ. of California-Berkeley. J. R. Hamilton’s 1973 Alexander the Great wasn’t as hostile, but A. B. Bosworth’s 1988 Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great turned back towards a more negative, or at least ambivalent portrait, and his Alexander in the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (1996) was highly critical. I note the latter two as Bosworth wrote the section on Alexander for the much-revised Cambridge Ancient History vol. 6, 1994, which really demonstrates how the narrative on Alexander had changed.

All this led to an unfortunate kick-back among Alexander fans who wanted their hero Alexander. They clung/still cling to Arrian (and Plutarch) as “good,” and the rest as varying degrees of bad. Some prefer Tarn’s view of the mighty conqueror/World unifier/Brotherhood-of-Mankind proponent, including that He Absolutely Could Not Have Been Queer. Conversely, others are all over the romance of him and Hephaistion, or Bagoas (often owing to Renault or Renault-via-Oliver Stone), but still like the squeaky-nice-chivalrous Alexander of Plutarch and Arrian.

They are very much still around. Quite a few of the former group freaked out over the recent Netflix thing, trotting out Plutarch (and Arrian) to Prove He Wasn’t Queer, and dismissing anything in, say, Curtius or Diodoros as “junk” history. But I also run into it on the other side, with those who get really caught up in all the romance and can’t stand the idea of a vicious Alexander.

It's not necessary to agree with Badian’s (or Green’s or Schachermeyr’s) highly negative Alexander to recognize the importance of looking at all the sources more carefully. Justin is unusually problematic, but each of the other four had a method, and a rationale. And weaknesses. Yes, even Arrian. Arrian clearly trusted Ptolemy to a degree Curtius didn’t. For both of them, it centered on the fact he was a king. I’m going to go with Curtius on this one, frankly.

Alexander is one of the most malleable famous figures in history. He’s portrayed more ways than you can shake a stick at—positive, negative, in-between—and used for political and moral messaging from even before his death in Babylon right up to modern Tik-Tok vids.

He might have been annoyed that Julius Caesar is better known than he is, in the West, but hands-down, he’s better known worldwide thanks to the Alexander Romance in its many permutations. And he, more than Caesar, gets replicated in other semi-mythical heroes. (Arthur, anybody?)

Alfred Heuss referred to him as a wineskin (or bottle)—schlauch, in German—into which subsequent generations poured their own ideas. (“Alexander der Große und die politische Ideologie des Altertums,” Antike und Abendland 4, 1954.) If that might be overstating it a bit, he’s not wrong.

Who Alexander was thus depends heavily on who was (and is) writing about him.

And that’s why nuanced historiography with regard to the Alexander sources is so important. It’s also why there will never be a pop presentation that doesn’t infuriate at least a portion of his fanbase. That fanbase can’t agree on who he was because the sources that tell them about him couldn’t agree either.

SECOND …scholarship has moved away from an attempt to find the “real” Alexander towards understanding the stories inside our surviving histories and their themes. A biography of Alexander is next to impossible (although it doesn’t stop most of us from trying, ha). It’s more like a “search” for Alexander, and any decent history of his career will begin with the sources. And their problems.

This also extends to events. I find myself falling in the middle between some of my colleagues who genuinely believe we can get back to “what happened,” and those who sorta throw up their hands and settle on “what story the sources are telling us, and why.” Classic Libra. 😉

As frustrating as it may sound, I’m afraid “it depends” is the order of the day, or of the instance, at least. Some things are easier to get back to than others, and we must be ready to acknowledge that even things reported in several sources may not have happened at all. Or at least, were quite radically different from how it was later reported. (Thinking of proskynesis here.) Sometimes our sources are simply irreconcilable…and we should let them be. (Thinking of the Battle of Granikos here.)

THIRD/SECOND-AND-A-HALF …a growing awareness of just how much Roman-era attitudes overlay and muddy our sources, even those writing in Greek. It would be SO nice to have just one Hellenistic-era history. I’d even take Kleitarchos! But I’d love Marsyas, or Ptolemy. Why? Both were Macedonians. Even our surviving philhellenic authors such as Plutarch impose Greek readings and morals on Macedonian society.

So, let’s add Roman views on top of Greek views on top of Macedonian realities in a period of extremely fast mutation (Philip and Alexander both). What a muddle! In fact, one of the real advantages of a source such as Curtius is that his sources seem to have known a thing or three about both Achaemenid Persia and also Macedonian custom. He sometimes says something like, “Macedonian custom was….” We don’t know if he’s right, but it’s not something we find much in other histories—even Arrian who used Ptolemy. (Curtius may also have used Ptolemy, btw.)

In any case, as a result of more care given to the themes of the historians, a growing sensitivity to Roman milieu for all of them has altered our perceptions of our sources.

These are, to me, the major and most significant shifts in Alexander historiography from the late 1800s to the early 2100s.

#asks#historiography#alexander the great#arrian#curtius#plutarch#diodorus#justin#w.w. tarn#fritz schachermeyr#a.b. bosworth#peter green#n.g.l. hammond#mary renault#robin lane fox#j.r. hamilton#ernst badian#classics#ancient history#ancient macedonia

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s your opinion—do you think there are ACTUALLY parallels between the late Roman Republic and contemporary America, or do you think that is too ahistorical to stand up to scrutiny? I’m torn personally, curious for your thoughts

I'd be shocked if there weren't. The US constitution is loosely based on the Roman republic's government. And the republic lasted so long - about 500 years, by traditional accounts - that there's a massive log of potential similarities to cherry-pick from.

However. That does not mean the USA is "going down the same path" as Rome did. For one thing, history doesn't have a logical path. We see only the version of events that we remember happening. Not the version that actually happened. Not the versions that were equally likely, but didn't happen.

Robert Morstein-Marx deconstructs this in Julius Caesar and the Roman People, a book that is as much about analyzing how we "create" history through our own biases, expectations and cultural baggage, as it is about Julius Caesar himself. He first points out that the Roman republic might not have been "falling apart" just before Caesar's civil war, and that we might have merely been looking at evidence that supports that narrative because we have the benefit of hindsight.

(RMM, Julius Caesar and the Roman People, p.19)

We don't pay much attention to the numerous times the end of the republic could have been averted. Caesar and Pompey nearly reached a peace settlement before their civil war broke out, and only Cato's interference stopped it. Caesar almost died at Dyrrhachium, whereupon the Pompeians would have retaken Rome. Octavian couldn't have taken control of Italy if not for the bizarre coincidence of both his superior officers dying in quick succession. Even as late as 14 CE, Tiberius attempted to return some power to the Senate, and he might've succeeded if not for his incredibly poor communication skills.

(RMM, Julius Caesar and the Roman People, p.14)

Also, Americans tend to focus on the end of the republic, because we are afraid of our own democracy being undermined. This impulse is understandable. But we don't think about how much turmoil the republic survived for 500 years. Machiavelli devoted chapters of Discourses on Livy trying to figure out why the republic didn't break down sooner. (I won't go into his answer here, but among other things, he's hilariously pro-rioting. For any reason, no matter how stupid. Keeps the government on its toes, you see.)

If we look at Roman history through the lens of our own time, we are likely to misunderstand what really happened. That can be dangerous. The American founding fathers were afraid of an "American Julius Caesar" subverting democracy, so they studied history...concluded the problem was that Caesar was too popular with the masses...and reduced the power of the popular vote by giving us the goddamn electoral college.

Looking for parallels can be fun. I've been mentally comparing Cato the Younger to certain politicians while reading about him. But don't take it too seriously.

Also, Julius Caesar and the Roman People is a great look into how the "sausage" of historical narratives is made - sometimes at the expense of the truth.

#just roman asks#roymerceni#historiography#julius caesar and the roman people#robert morstein-marx#ancient rome#jlrrt essays

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top five history books?

Thank you for the ask! ✨

Some of my favourites may be well known at this point after the book ask, but I'll try not to repeat myself too much!

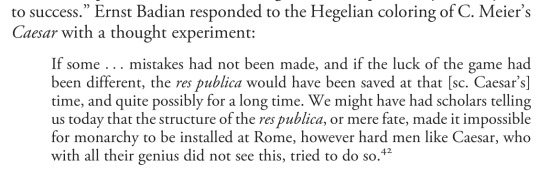

1. Ghosts in the Middle Ages: The Living and the Dead in Medieval Society by Jean-Claude Schmitt

A fascinating book on a rather niche topic which explores the changes in people's belief about ghosts/souls of the dead coming back to life. Schmitt does not only focus on obscure anecdotes however; he analyses what role the so called 'revenants' came to play in medieval society (spoiler alert: the Catholic church used stories about them to their advantage to pressure people into paying indulgences and/or spread Catholic doctrine).

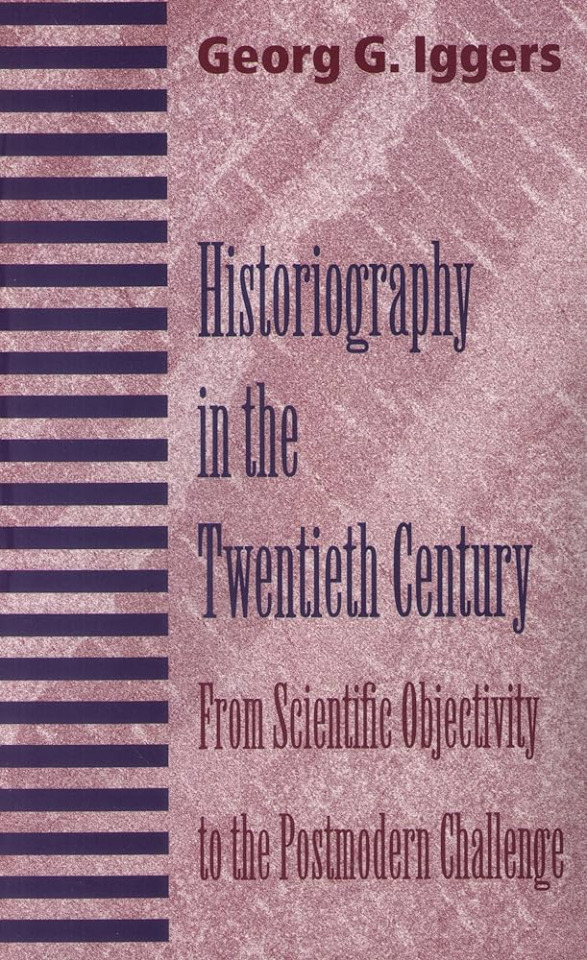

2. Historiography in the Twentieth Century: From Scientific Objectivity to the Postmodern Challenge by Georg G. Iggers

Not sure if this is cheating or not, since I had to read it for uni? The title sounds quite bland, but I actually enjoyed reading it quite a bit! It gives you a framework for how to think about other history books in terms of reliability and potential biases. The author also explores the question where is the line between history and fiction (and whether it is as clear-cut as we would like to think). (It also defends the Age of Enlightenment legacy from postmodern criticism which I appreciate, though I'm not sure this would be of much interest to people who don't study/aren't into philosophy.) Still, it's quite a short, comprehensive read and a great place to start when one wants to learn more about historiography imo.

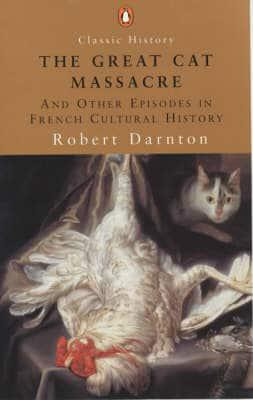

3. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History by Robert Darnton

Probably my favourite book on this list, since it hits so many of my areas of interest (French history, the 1700s, cultural and especially book history). It includes six essays which analyse different aspects of French culture across different social classes, ranging from villagers' fairy tales to analysing the texts of the Encyclopédistes. It's also very engaging and fun to read, though be warned, if you like cats, maybe skip the titular chapter, the name is quite literal I'm afraid!

4. Jean Paul Marat: Tribune of the French Revolution by Clifford Conner

Okay, I'll confess, I'm only about half-way through, but I'm really liking it so far! It reads more like an apology/ a text that tries to correct some of the problems with previous biographies on Marat, but I actually quite like it. It makes for an interesting read.

The author definitely has biases on his own, since it is clear that he shares much of Marat's political views, but a) he's upfront about the fact b) I don't think that the goal of all historical books should be to be as objective as possible - there's a room for subjectivity in my opinion, as long as it is reflected c) he cites his sources much more meticulously than - let's say - Scurr d) his biases are also my biases

Plus, Marat is such an interesting figure to read about! That said, this Goodreads commenter puts it much better than I ever could:

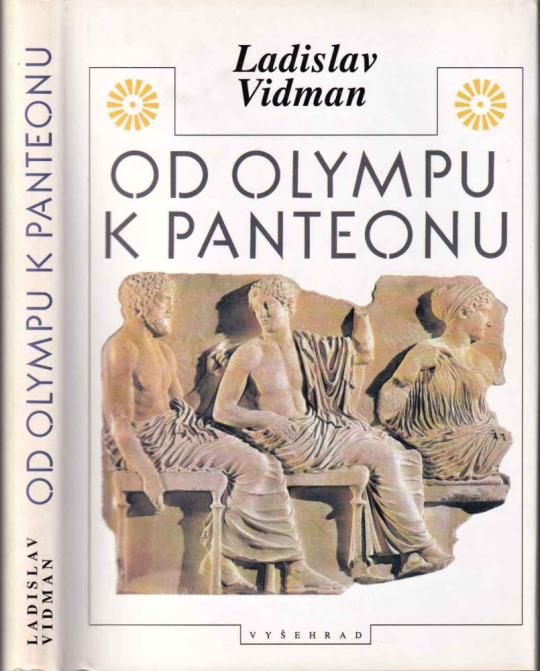

5. From Olympus to Pantheon: The Religion and Ethics in Ancient Times by Ladislav Vidman

A super interesting and accessible overview of the religious practices of ancient Greece and Rome! The author explains that many books focus on mythology, but his aim is to explore the lesser known aspects of the Greek and Roman religiosity, such as the ritual sacrifices, the oracles, the mysteries etc. It was a fascinating read, though the chapter on the sacrifices was very, very vivid in its descriptions.

(The author also seems to low-key have a crush on Vergil, explaining how he was a great role model and essentially beautiful inside and out. Not a deciding factor, but definitely a bonus!)

I unfortunately don't think the book was ever translated from Czech though, which is a shame. It would be certainly worth it!

#thanks for the ask!#ask game#history#historiography#Lin reads#1700s#18th century#tagamemnon#ancient rome#ancient greece#roman religion#greek religion#frev#french revolution#jean paul marat#middle ages#french history#bookblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sparta: Savage or Noble?

My name is LauraJean, and as the Special Collections Classics Intern for this semester, I will be researching and writing about Classical antiquity through materials preserved in Special Collections.

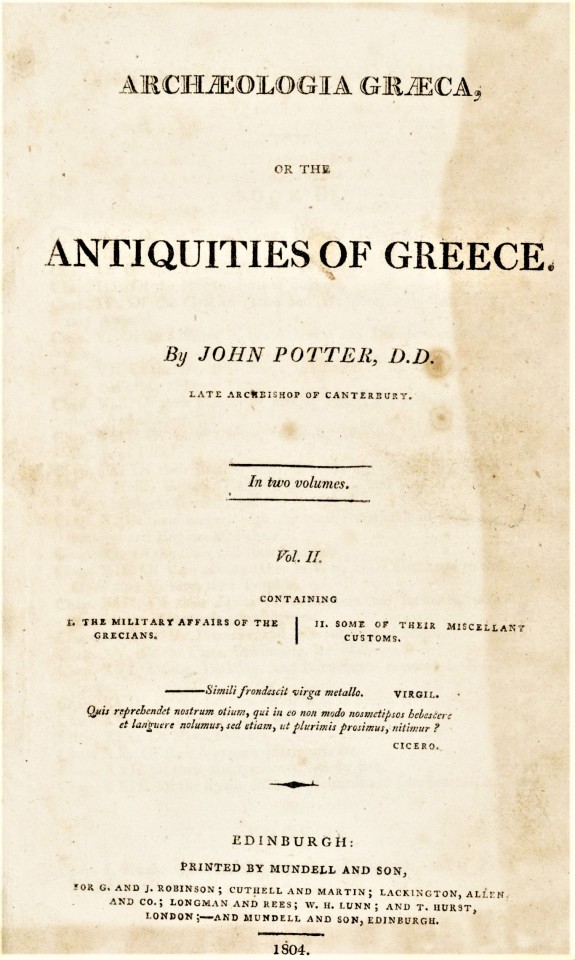

Today I would like to discuss English Archbishop John Potter’s view of the Spartans and how that view has persisted over time. In 1697, Potter published his highly influential work, Archaeologia Graeca, or, The Antiquities of Greece, which continued to be republished in numerous editions well into the 19th century. Our copy is an 1804 edition printed in Edinburgh by Mundell and Sons for themselves and for a number of London booksellers. The various editions would become a contributing force for the next generation’s understandings of these ancient cultures, a sentiment that would be positive if it weren’t for the fact that Potter’s writings are dangerously biased.

Despite citing the works of the ancient Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides, Potter speaks in near opposition to their writings, most notably when describing Sparta. Instead of the relationship-based, decisive, organized culture described by the ancient historians, the archbishop morphs them into a jealousy-driven, impulsive, tyrannical state.

On the opposite side of the ancient civilization, Potter praised the Athenians as civilized, well-meaning allies to those in their empire, despite Thucydides' histories depicting the many betrayals the democracy committed against their allies.

These biases were not born from any ancient sources listed by Potter, so this raises the question of where these ideas originated. Though it's impossible to pinpoint the motivations of this or any individual accurately, we can make some inferences by looking at the current events of the time. The early 18th century saw England at the height of its colonial power, but with that power came a distrust of their European neighbors, especially Spain and France. Their neighbors would be only one of their many problems. As with Athens, the people subjected by English rule were not always compliant, the results of which would come to pass in the next handful of decades.

These biases would continue into the next generations of scholars and with the influence of France only growing with the rise of Napoleon, the disdain shown by English scholars for the Spartans only increased, influencing the popular imagination about the Spartans even to our own day..

-- LauraJean, Special Collections Undergraduate Classics Intern

#Classics#classical antiquity#classical history#Sparta#Athens#Classical historiography#Ancient Greece#John Potter#Archaeologia Graeca or The Antiquities of Greece#Mundell and Sons#LauraJean

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

As with other history women's history begins with kings and battles for very specific reasons:

One of the various elements that goes into all history, not just women's history, is that history begins with a vastly different world where less than 5% of the population could read and write, and where histories worked very differently and reflected the literate audience of the time. As a general rule scribes were overwhelmingly masculine and had some of the usual cliquish elements of such groups then and now. This is why an overwhelming number of the women who appear in more traditional, as opposed to the harder and deeper work of social histories, are elites, rulers and nobles, and why the view of women's lives is shaped by that of an elite caste who were not necessarily typical by any means of how most women lived, any more than their male counterparts were of men at the time.

This is also why women's history tends to zero in on specific personalities who rose both in spite and because of these biases in specific ways, a pattern that lasts well into the 20th Century in different parts of the world. In this case a bartender named Kubaba became one of the rulers of Kish, which at the time was the central hegemon of all Sumer, and in this sense could retroactively be called the first Empress. She predates Sobeknefru and Hatshepshut by a millennium, and this too makes a point about the nature of elites and power. The women who were parts of these groups were always able to fit into various holes, so to speak, in how power worked and to seize and hold it in various ways.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I suspect people miss my header image and assume its a Greek temple. If you look at the pillars for a second though, you'll see that it's very modern looking, even surreal. It is, in fact, a Serbian monument called "The Mausoleum of Struggle and Victory" from the socialist era. The aesthetic combines Modernism and Neo-Classicism. The photo itself is by Yang Xiao, as part of a series combining artificial lights with decaying socialist-era monuments at night, called "Eternal Monuments in the Dark."

By framing socialist bloc architecture as classical ruins, and placing the democratic revolutions of Greece along side modern socialist revolutions, I'm making a point about historical narratives and associations. Ancient Mediterraneans didn't associate themselves with Northern Europeans, and to this day people are shocked by how "Eastern" Greek culture is. In many ways Islamic culture is more Roman than Western Culture. The Fascist fantasy of the past is just that: a fantasy. A tool they use for their political goals. They homogenize the diversity of Rome, they whitewash Greek statues, and they impose modern Classical music on cultures that wouldn't recognize it.

youtube

Liberals talk about how Ancient Greece is the foundation of Western Civilization™️, but they have no greater claim to it than Muslims or Buddhists. (The Greeks got around.) There is nothing in bourgeois political forms that's reminiscent of Athens, except perhaps for their hypocrisy towards their slaves. Many of the things the peasants and proletarians of Greece and Rome fought for were actively despised by Hamilton, Jefferson, and that whole lot of grifters. They hated universal male suffrage, they hated mass assemblies, they hated ballot measures, they hated rotation and sortition, and they hated land reform and debt abolition. They didn't love "the ancients," they loved their aristocrats.

Socialists have long loved the defeated reformers and revolutionaries of the ancient past. The first modern communist called himself "Gracchus Babeuf." What I'm doing isn't special. The point is to take the things the bourgeois order claims it's built on, and show how fake it all is.

One day, the role the Classical Mediterranean plays in the modern superstructure will be replaced by the Socialist Bloc: a defeated experiment whose ruins global Communism will rest on. Their monuments, now covered in graffiti, will one day be visited by tourists the way the Parthenon is, to marvel at their glorious ambitions.

#socialism#communism#Marxism#history#Ancient Greece#Ancient Rome#architecture#historiography#Youtube#Soviet Union#Serbia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The annoying part of this Master’s program is that the theoretical courses are also studied by archaeology (in the general sense, not just ancient archaeology) students and they’re the majority, which means that most of the lectures/seminars are focusing on archaeology and I’m so boreddd.

#personal#I don’t give a shit about gis im sorry#give me my historiography back#i mean I kind of get it#because my master’s called classical archaeology and ancient history#but im more interested in the ancient history part u feel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now, how real this is, is dubious and Piedimonte isn't giving me the direct source for his quote ... but there is something very funny about the idea that Emperor Nero let ever more Egyptians settle in Naples (and other places, I assume), because he liked the way they flatter him.

What I like the most about this tidbit is that it shows that Mohammed learned only from the best to flutter his eyelashes.

#beablabbers#I wonder what Hima's idea is of when Ancient Egypt disappeared as a personification.#either way. momma knows best. and this makes me miss my Jerusalem AU with the Egyptians as peddlers#storie nostre#mohammed#aph#aph egypt#aph ancient egypt#also we're operating on thoodleo and horrible histories rules: I'll let historiography slide if it's funny enough

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Im just gonna talk about epistemology here.

"How one man rewrote a thousand years of history"

https://youtu.be/4k6r5Kkts0s?si=FGw_qosf2jiiW_8b

This is just a video about how sources all cite each other and they ultimately are going off of another few sources from a few hundred years ago that used vague language and misinterpreted each other.

Because knowledge can be a ridiculous game of telephone.

How do you know what you know?

Your senses aren't actually trustworthy.

How would you recognize truth if you saw it? You have nothing to compare it to as a baseline.

But it isn't Wikipedia or the internet that is the problem.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge, and how we know what we know.

But I think it is equally accurate to say it is the study of doubt.

If you believe that true knowledge is impossible than you are an epistemological nihilist.

Or pyrrhonian skeptic as we are sometimes called.

But that does not mean you can't or shouldn't work on your suppositions. If something seems like a positive thing to do, than you should still do it.

But questioning what you know will not hurt you, because we are all just casting about in the dark anyway.

So you don't have to feel bad for not knowing the right answer.

(Pyrrho was a Greek philosopher circa 270 b.c. who may have traveled to, or had contact with the linguistically/culturally Greek kingdom of Bactria, in what is now called the Indian subcontinent ---and therefore been exposed to Buddhism. But it is really hard to verify anything about it. Which is not irony. It's the opposite. He would, I'm sure, be very happy with that. Smug even.)

#irony#philosophy#nihilism#epistemology#historiography#history#ancient greek#greek philosophy#classical literature#buddhism#classical period

1 note

·

View note

Text

SUMMARY

Why did human beings first begin to write history? Lisa Irene Hau argues that a driving force among Greek historians was the desire to use the past to teach lessons about the present and for the future. She uncovers the moral messages of the ancient Greek writers of history and the techniques they used to bring them across. Hau also shows how moral didacticism was an integral part of the writing of history from its inception in the 5th century BC, how it developed over the next 500 years in parallel with the development of historiography as a genre and how the moral messages on display remained surprisingly stable across this period. For the ancient Greek historiographers, moral didacticism was a way of making sense of the past and making it relevant to the present; but this does not mean that they falsified events: truth and morality were compatible and synergistic ends.

Moral History from Herodotus to Diodorus Siculus

Lisa Irene Hau

2016

Published by: Edinburgh University Press

Lisa Irene Hau is Lecturer in Classics at the University of Glasgow

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Melian Dialogue

Of all the history-defining moments written about in Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, by far my favorite is the Melian Dialogue. It’s a quick read if you want to be fully informed: http://academics.wellesley.edu/ClassicalStudies/CLCV102/Thucydides--MelianDialogue.html

Back from reading it? Alright great. Now you understand why it is more than a little funny to me.

Melians: spouting philosophy and political rhetoric

Athenians (supposedly the kings of that stuff): if you don’t surrender we will just kill you

Melians: yes but if we live will we be slaves?

Athenians: yeah but that’s better than being killed

Melians: truly a fate worse than death

Athenians: yeah if you’re dumb as shit, we’re just gonna kill you and we’re gonna do it painfully. Just make this easy and surrender.

This is, of course, a summary, but the funny thing is how it ends. The Melians fight cleverly and bravely and all that, but in the end the Athenians get in and what they said they’d do they did. They kill the men and sell the women and children into slavery, which was an increasingly common practice at this point in the war.

There’s no lofty historical conclusion to make here. Maybe I could say that if there’s a huge ass army and they say “we’re going to kill you” maybe make the pragmatic decision and don’t get killed, but you know that’s not very romantic.

I’m just saying though the Athenians definitely had a track record of doing this at this point; like that was definitely something that was gonna happen.

Thanks for reading, a bit more conversational with this one but I hope you don’t mind.

1 note

·

View note

Note

In some of your posts, you've said we can't believe the speeches in the original sources like Plutarch and Arrian. And I get it, that they wouldn't have ways to record exactly what people said, but wouldn't they try to get it at least close? Didn't orators publish their speeches, so they'd know what they said? Demosthenes published speeches about Philip, I know. And wouldn't readers back then get angry if they realized the writers were just making things up?

When it comes to ancient texts, particularly ancient historical texts, speeches, dialogue, and letters are especially problematic. Why? Authenticity.

As the asker indicated, a lack of recordings automatically problematizes this. But their memories were generally better. The real issue centers on ancient ideas of WHAT HISTORY WAS FOR.

Ancient historians were writing to entertain, as well as to educate, and promote their notions of how the past should be understood, often to school people in their present. “Cautionary tales,” if you will. Or models to emulate. When they do say where they got their information (frustratingly rarely), it’s as much to show off their education/how well-read they are, rather than to assure their readers they know what they’re talking about.

It’s critical to understand that ancient history was akin to modern creative nonfiction. I don’t say that to diss creative nonfiction (says the historian who also writes historical fiction). But it’s crucial to recognize it was nothing like modern academic history with footnotes, peer reviews, and fact-checks.*

In terms of preserved speeches (or orations), we have two types. The first (often forensic) were published after the fact by the orator himself.** Those are indeed their words, but their edited words. Unlike now, ancient speeches were typically composed aloud, not in writing. But at least speeches published by the orator are authentically their ideas, if not, perhaps, what was actually said (in court, the assembly, etc.). Nobody is putting words in their mouth.

By contrast, the orations and dialogue in our histories are the creations of the authors of those histories. Why goes back to the first (Greek) historians: Herodotos and Thucydides (and Xenophon). They set a pattern that later generations deliberately followed. All put speeches into the mouths of their major players. This is called oratio recta (direct speech), or what we’d call a quotation. Another form is oratio obliqua (indirect speech), or what we’d call a summary or a paraphrase. In general, the use of the former characterizes the Greek historians, while Roman historians preferred the latter. (There are any number of exceptions, however.)

Incidentally, these writers didn’t lie about it. Their readers/listeners realized it highly unlikely Herodotos knew what Darius or Xerxes said back in Susa or in the Persian camp, but they were there for the drama. Thucydides even admits (1.22.1) he has no clue what was said in the speeches he records from the Peloponnesian War, but he wrote what he thinks would have been proper for the situation.

Why make it up?

Orations were entertainment.

Just as modern fiction authors craft a story to forward themes and motifs, so also with ancient authors. When an author writes out a speech, PAY ATTENTION. It usually contains key points.

In our modern world with lowered attention spans, we can forget that people might listen to orations (especially longer ones) for fun.

Yet this is extraordinarily recent. For as long as we’ve been human, we’ve gathered to hear good storytellers and be inspired by good speakers. Sometimes the art of rhetoric is equated with intentional lying. That’s cynically silly. The art of rhetoric just means getting across your point clearly, and powerfully. A goodly chunk of Barack Obama’s appeal was his fine rhetoric. Ironically (and like it or not), the same can be said of Trump; the Maga crowd adores his word-salad “oration” style. Similarly, in some religious traditions, “good preachin’” is considered essential to good pastoring. And monologues, whether comedic, newsy, or folksy can develop cult followings, as The Rachel Maddow Show proves, or Stephen Colbert, or the much earlier “News from Lake Wobegon” from Prairie Home Companion (Garrison Keillor). You can probably name another half-dozen without breaking a sweat.

Because the oration was a form of entertainment in antiquity, many ancient authors sought to prove their own creative brilliance by writing speeches. That’s why you should never, ever, ever assume a verbatim speech in ANY Classical Greek or Roman text is what the speaker actually said. If you’re lucky, it may at least represent the gist. But it also might not. Dialogue is similar. They make it up.

With letters, one might think at least they could copy it—no need to remember. Like orations, letters were sometimes published by one of the authors, for posterity. (The letters of Cicero, or the Younger Pliny are good examples.) Yet the same principle applies. Letters were a way for an historian to display creative chops so “tweaked” letters were not uncommon, even if based on an original. And sometimes letters were invented whole-cloth, at need.

Yet there’s another issue with letters that moderns aren’t aware of: accidental forgeries.

How can a forgery be accidental?

It’s a rhetorical-school lesson that “escaped.”

A popular assignment for students was to write a letter (or oration) “in the style of ___ famous person,” or “as if from the point-of-view of ___ famous person.” Lessons weren’t just to learn how to turn a phrase, but also to instill proper morals. So, for instance, some ancient schoolboy’s essay prompt might be: “Illustrate pistos/fides (loyalty) in a letter from Alexander to his mother, Olympias.” To get a good grade, he had to show he knew something about Alexander, about proper pistos/fides, as well as how to write like a king.⸸

Some of these letters got confused later with the real thing. Remember, record-keeping was rather haphazard.

So…recorded speeches, dialogue, and letters in our ancient histories should be regarded much the same as you’d regard such in modern creative non-fiction: dramatization to increase reader interest.

——————————————-

* This isn’t to say ancient historians never critiqued each other; they most certainly did. Sometimes quite brutally—and from the beginning. Thucydides is our the second surviving Greek historian and he begins his history by, in his very first chapter, including an oblique criticism of Herodotos, who invented the discipline!

** Male gender used on purpose. Greek women weren’t allowed to make public speeches, and Hortensia was considered a weirdo who pissed off the Second Triumvirate. She certainly gave a speech, but Appian put words in her mouth—like most ancient writers.

⸸ Ironically, I do something very similar in my own classes on Alexander. We put him on trial for war crimes, and students write either as Alexander in his own defense, or as the prosecutor, whoever that might be (Demosthenes, the King of Tyre, a Persian noble, etc.). They must write their speech demonstrating the morals of the ancient world, not the modern, using the primary sources. To get a feel for it, they must read a couple Greek forensic speeches too, in order to understand how to properly frame their arguments. This allows them “to get into the heads” of the ancients themselves. It’s not only more fun, but more effective as a learning tool, imo.

#asks#ancient literature#speeches in ancient literature#letters in ancient literature#historiography#Classics#Greek historians#Roman historians#ancient history#tagamemnon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern historian: I will portray this complex person in a nuanced and even-handed way

Sallust: Catilina is a BITCH with heart black as TAR and I hate his ugly stinky FACE

#sallust is hilariously judgey#big 'old man yells at cloud' vibes#it's especially funny when he almost gives the catilinarians a good reason for their rebellion#but he's so wrapped up in shit-talking catiline he fails to notice it#you're so close to class-consciousness sallust. so close#sallust#catiline conspiracy#historiography#ancient rome#jlrrt speaks#Bellum Catilinae

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

If any of the really smart classics people that are here on Tumblr see this, I'd really appreciate your help!

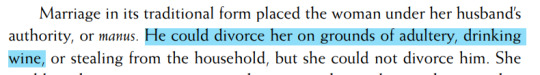

It seems kind of hilarious but... was it really possible to divorce your wife just based on her wine drinking habits? Do we know if it ever actually happened?

I've read this wild fact in the preface to the Other Voice in Early Modern Europe series introduction and would love to know if there's any truth to it/if there's any more context

(If it's any help, it should refer to the earlier period of the Roman Republic, before women were allowed to apply for a divorce as well.)

#classics#classical studies#ancient rome#roman history#roman republic#tagamemnon#need help#women's history#historiography#I realise this is not really significant but I'd love to know#roman empire#latin#classics memes#classics major#annoyingly there are no sources in the book I could find

6 notes

·

View notes