#Celt.

Photo

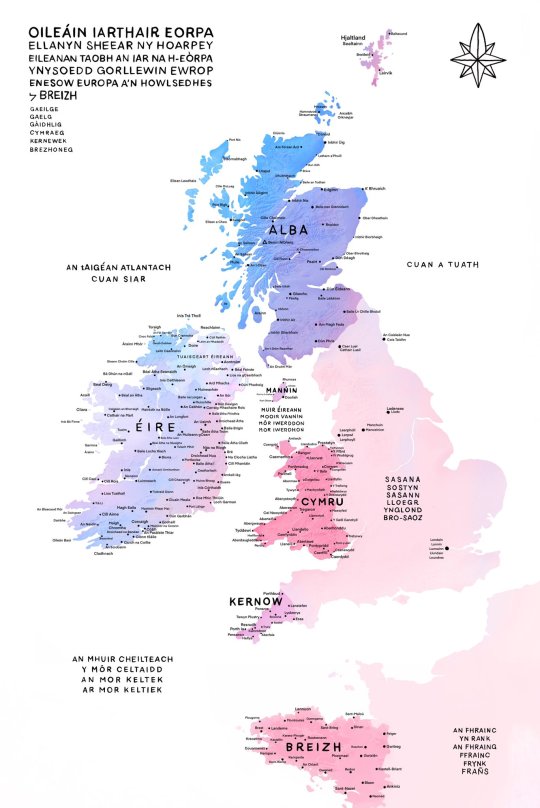

The Celtic Nations with their native place names.

by oglach

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

they dont get enough love

#the secret of kells#song of the sea#wolfwalkers#cartoon saloon#animation#movies#tuatha dé danann#aos sí#selkie#ireland#irish mythology#celts#celtic mythology#personal

739 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unfinished portraits of Irish gods from 2021

#celtic#celtic paganism#celtic mythology#celtic polytheism#irish paganism#irish mythology#irish#paganachd#pagan#paganism#druidism#druidry#irish culture#ireland#eire#ancient ireland#ancient celts#mythology#digital art#digital illustration#portrait#art wip#unfinished

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oak Statuette of the Goddess Epona from Winchester, England dated to the 1st Century CE on display at the Winchester City Museum in Winchester, England

This small statue is thought to be the Gallo-Roman goddess Epona who was a protector of horses and goddess of fertility. While Epona's origins are from Celtic peoples the goddess proved to be very popular amongst the cavalry regiments in the Roman army. She was the sole Celtic diety worshipped in the city of Rome due to this.

Photographs taken by myself 2023

#art#archaeology#history#celts#celtic#england#english#ancient#roman empire#winchester city museum#winchester#barbucomedie

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Iron Age sword hilts, from Ballyshannon, Donegal, Ireland & Yorkshire, England

426 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arms and Armor of the Hallstatt Celts: A (not-so) Brief Overview

The Hallstatt culture is an archaeologically-defined material culture group. The typesite for this group is in Hallstatt, Austria, where a deep salt mine which had been in use since the Neolithic served as the lifeblood of the local community. A substantial cemetery of approximately 1,300 burials near the mine has helped to clearly define artistic trends associated with this cultural group. The culture is associated with early Celtic or proto-Celtic language speaking groups, and for a long time, was thought to have been the origin of the proto-celtic language. This idea has since been debunked, as it is now known the first proto-Celtic speakers predated the Hallstatt culture.

The Hallstatt culture is divided into four phases, A-D (henceforth abbreviated as Ha. A-D). The first two of these phases are associated with the end of the bronze age in the region, the last two, with the beginning of the iron age.

Since the defining of the culture in 1846, Hallstatt influence has been found from Eastern France to Hungary, as far south as Serbia and as far North as Poland. The core Hallstatt region covers much of Austria and Southern Germany. By the Ha. C period, distinct practices had arisen in the Hallstatt sphere of influence: distinct enough for academics to split the culture into two “zones”, the East and the West.

Unfortunately, due to the antiquity of this culture and the utter lack of any written records concerning them, the archaeological record is both relatively thin, and the only source of information available for these people. As such, in constructing a timeline of Hallstatt arms and armor, there will be substantial gaps which we can only hope will be filled by future discoveries.

Armor

Three types of armor are commonly found in Hallstatt contexts: belts, cuirasses, and helmets.

That broad belts (both of leather and of bronze) are considered armor in the ancient Mediterranean is clear from references in which these items are placed in context with other armor. In the Iliad, for example, in book 7 after Ajax and Hector meet on the field of battle and fight to a stalemate, they exchange equipment. Hector “gave over his silver-studded sword, bringing with it the sheath and well-cut baldric” (l. 303-304), while Ajax reciprocated with “his war-belt bright with crimson” (l. 305). Additionally, a short list of military equipment issued by the Neo-Assyrian empire recovered in Tel Halaf lists 10 leather belts alongside bows, swords, spears, and other arms and armor.

A number of bronze and gold belt plates survive from both the Eastern and Western zones, though most of these plates date to the Ha. D period.

While the majority of these plates are decorated with embossed and incised geometric patterns, some (particularly from the Eastern zone) include scenes of warriors on foot and on horseback.

The cuirasses of the Hallstatt period exhibit an interesting progression. In their most basic form, these bronze cuirasses remain essentially the same from Ha. A-D. They are characterized by essentially simple forms: a tubular breast and backplate which terminates at the waist and includes a tall standing collar to defend the neck. The earliest examples, however, include substantial embossed decoration in much the same manner as appears on the belt plates.

Only in the late Ha. B to early Ha. C period does this decoration begin to take on a more anatomical form; a group of seven cuirasses recovered in Marmesse, France in 1974 shows this evolution nicely. These cuirasses retain the same form, though a slight taper is now evident near the waist. The circular embossing closely resembles that of the previous period, however embossed lines are now apparent, and the placement of the embossing is such as to evoke the musculature of the warrior wearing it.

The final stage of the cuirasse’s evolution arrives in Ha. D. This form is much more plain, lacking the apparent horror vacui which typified earlier iterations of this style. Instead, the anatomical element is even more pronounced: embossing emphasizes the warrior’s pectoral and abdominal muscles, and additional circular bronze plates are riveted to the upper chest to simulate nipples.

The final element of armor with substantial enough evidence in a Hallstatt context to be addressed is the helmet. Unfortunately, surviving helmets are extremely scarce, and there is no pictorial evidence to consult prior to the Ha. D period.

Four helmet types appear both archaeologically and artistically in Hallstatt contexts. We will call these the crested, the plated, the double-crested, and the Negau.

Only one artistic example of the crested helmet is to be found, and no archaeological examples. It is to be found on a grave good in the shape of a wagon adorned with many figures made ca. 600 BC and recovered in Strettweg, Austria.

A find from Normandy (outside the Hallstatt sphere of influence) dated ca. 1200-700 BC shows what this type of helmet may have looked like.

The plated type is nearly as obscure, represented by only a single survival and a single artwork. The helmet, recovered in Šentvid, Slovenia and dated ca. 800-450 BC, is curious for the distinct pearly texture of its surface.

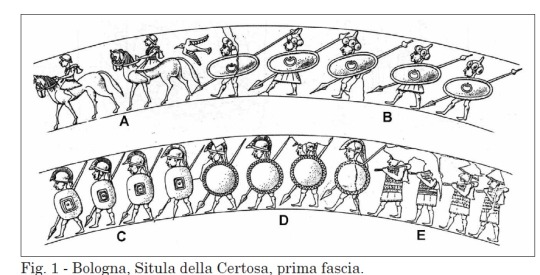

A number of similar helmets appear on a situla recovered from the Certosa Necropolis in modern Bologna, Italy. This situla is dated ca. 600 BC, and bears a striking resemblance to other situlae found in Hallstatt contexts.

The most well attested form of Hallstatt helmet is the double-crested type. This type appears with the onset of Ha. D, and sees use until the end of the Hallstatt period. It is attested to by several survivals

and numerous depictions on a number of situlae

and belt plates.

This type is so-called for the twin crests that adorn the helmet’s skull; crests which, as is attested by the pictorial evidence, served as anchors to large plumes likely made from horse hair.

The final type is named for a town in Slovenia where a large cache of helmets of this type was found in 1812. The Negau type appears at the very tail end of Ha. D, and primarily in Etruscan and Italic contexts. However a number of finds (including the eponymous horde) come from regions of Hallstatt (and eventually La Téne) influence.

Weapons

The weapons which can be found in Hallstatt contexts are very much the same as those found elsewhere in Europe, consisting primarily on spears, axes, swords, and daggers. The spears and axes of the period are very similar to those found elsewhere in Europe and across the Mediterranean in the late bronze to early iron age, and as such will not be discussed further.

Indeed, even the swords of the Hallstatt bronze age (Ha. A-B) bear no significant differences from other swords found in Central and Western Europe at the time.

It is not until Ha. C, and the advent of the iron age, when two new types unique to the culture emerge. Though similar, these sword types, called Gündlingen

and Mindelheim, are distinguished by a number of factors.

First and foremost is size, with Mindelheim swords averaging around 85 cm or 33.5 in in length, while the Gündlingen type only averages 70-75 cm (27.5-29.5 in). Another striking feature of the Mindelheim type which is almost non-existent on Gündlingen swords is a pair of deep grooves on either side of the blade. Additionally, Gündlingen swords are only ever found in bronze, while Mindelheim can be found in either bronze or iron. Gündlingen swords seem to have been tremendously greater in popularity, with only 27 examples of the Mindelheim type being known to over 240 of the Gündlingen. There is also a geographical element: the majority of Mindelheim swords have been found in the east from Austria to Germany, Poland, and as far north as Sweden. Gündlingen swords, by contrast, have mostly been found in the west, as far as Britain and Ireland. Neither type, however, can be found in the core Hallstatt Regions after the advent of Ha. D, when daggers become the primary funerary good of the elite.

Daggers, of course, were not unknown in Hallstatt regions prior to 620 BC. A number of survivals from Ha. A-B attest to the fact that single-edged daggers were popular.

With the advent of the iron age and the rise in popularity of the peculiar Hallstatt sword types, daggers become more rare, until once again they spring back to the fore in Ha. D. At this time, a particular dagger type is almost ubiquitous. This dagger has long, straight quillons mirrored by a tubular pommel. The grip is thin, and the blade is broad and double-edged. This same basic form is present, both plain and with various embellishments, until the end of the Hallstatt period.

#arms and armor#weapons#armor#ancient history#hallstatt culture#celts#iron age#art#history#ancient celts#sword#axe#dagger#spear

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blair Drummond Iron Age Hoard, Gold Torc (with a hoop of twisted wires, its terminals decorated with filigree and granulation), 3rd to 1st Century BCE, National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#iron age#prehistoric#prehistory#neolithic#mesolithic#paleolithic#iron age living#metalwork#metalworking#torc#celtic#celt#jewellery#gold#filigree#archaeology#ancient cultures#ancient living#Scotland

92 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Like the mushroom in the woods, we may appear to be a single entity, but we are invisibly connected by a network as wide as the forest floor.

Mara Freeman, Kindling the Celtic Spirit

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Still more important is the realization that all those generations of British people (largely men), who were educated in the classics, were being taught to understand and sympathize with the Greeks and Romans. When thinking of the long confrontation between the Celts and Romans, therefore they instinctively sided with the Romans. They would have all read Tacitus' warning: "Remember, they are barbarians..." For the Romans were seen as the bearers of civilization and the ancient Britons as the uncivilized.....

All manner of pressure was brought to bear to ensure that British schoolboys empathized with Rome. From the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth, every educated person was required to learn Latin. Caesar and Tacitus were among the very first authors which all those pupils were obliged to read. Yet no one taught them anything about the Celts, let alone a Celtic language. Even today, when the teaching of classics in the United Kingdom has sharply declined and Celtic studies receive a measure of official support, for every British schoolchild that learns even a little about the native Celtic heritage, there are a hundred that still learn about the heritage of Rome.

A whole literary genre was devoted to strengthening the bond of identity between the modern Britons and the Ancient Romans. Any number of books and poems have been written to invite the reader to stand in Roman shoes, to put oneself shoulder to shoulder with the legions in the eternal struggle of civilization against barbarity.

-Norman Davies, The Isles

#So this book presents an interesting view of modern England that claims that Englands obsession with colonization imperialism and conquest#is directly descended from Britains own colonization by Rome#The modern Englishman according to Davies knows more about Greece and Rome than the pre Roman history of his own land#Even modern English people believe that the Celts Picts and Gauls (their own ancestors) were savage barbarians#whose conquest by the more “civilized” Romans was NECESSARY to make the isles civilized.#cycle of violence etc#colonization#colonialism#roman history#british history

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 2: Irish tattoos

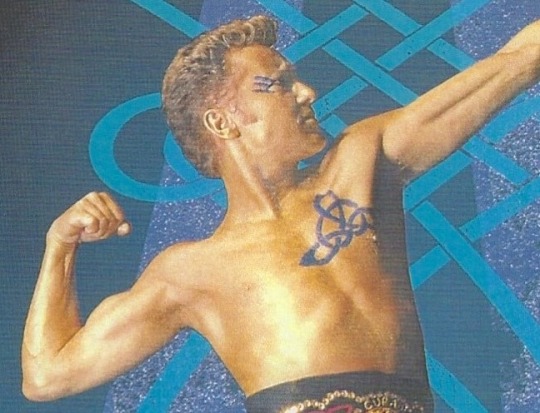

Clockwise from top left: Deirdre and Naoise from the Ulster Cycle by amylouioc, detail from The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife by Daniel Maclise, a modern Celtic revival tattoo, Michael Flatley in a promotional image for the Irish step dance show 'Lord of the Dance'

This is my second post exploring the historical evidence for our modern belief that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves with blue pigment. In the first post, I discussed the fact that body paint seems to have been used by residents of Great Britain between approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. In this post, I will examine the evidence for tattooing.

Once again, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group who lived in the British Isles, this time from the Roman Era to the early Middle Ages. The relevant text sources range from approximately 200 CE to 900 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’, ‘Scot’, and ‘Pict’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Continental Written Sources:

The earliest written source to mention tattoos in the British Isles is Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire written circa 208 CE. In it, Herodian says of the Britons, "They tattoo their bodies with colored designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decorations on their bodies" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Herodian is probably reporting second-hand information given to him by soldiers who fought under Septimius Severus in Britain (MacQuarrie 1997) and shouldn't be considered a true primary source.

Also in the early 3rd century, Gaius Julius Solinus says in Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium 22.12, "regionem [Brittaniae] partim tenent barbari, quibus per artifices plagarum figuras iam inde a pueris variae animalium effigies incorporantur, inscriptisque visceribus hominis incremento pigmenti notae crescunt: nec quicquam mage patientiae loco nationes ferae ducunt, quam ut per memores cicatrices plurimum fuci artus bibant."

Translation: "The area [of Britain] is partly occupied by barbarians on whose bodies, from their childhood upwards, various forms of living creatures are represented by means of cunningly wrought marks: and when the flesh of the person has been deeply branded, then the marks of the pigment get larger as the man grows, and the barbaric nations regard it as the highest pitch of endurance to allow their limbs to drink in as much of the dye as possible through the scars which record this" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

This passage, like Herodian's, is clearly a description of tattooing, not body staining or painting. That said, I have no idea of tattoos actually work like this. I would think this would result in the adult having a faded, indistinct tattoo, but if anyone knows otherwise, please tell me.

The poet Claudian, writing in the early 5th c., is the first to specifically mention the Picts having tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). In De Bello Gothico he says, "Venit & extremis legio praetenta Britannis,/ Quæ Scoto dat frena truci, ferroque notatas/ Perlegit exanimes Picto moriente figuras."

Translation: "The legion comes to make a trial of the most remote parts of Britain where it subdues the wild Scot and gazes on the iron-wrought figures on the face of the dying Pict" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

Last, and possibly least, of our Mediterranean sources is Isidore of Seville. In the early 7th c. he writes, "the Pictish race, their name derived from their body, which the efficient needle, with minute punctures, rubs in the juices squeezed from native plants so that it may bring these scars to its own fashion [. . .] The Scotti have their name from their own language by reason of [their] painted body, because they are marked by iron needles with dark coloring in the form of a marking of varying shapes." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

Isidore is the earliest writer to explicitly link the name 'Pict' to their 'painted' (Latin: pictus) i.e. tattooed bodies. Isidore probably borrowed information for his description from earlier writers like Claudian (MacQuarrie 1997).

In the 8th century, we have a source that definitely isn't Romans recycling old hearsay. In 786, a pair of papal legates visited the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (Story 1995). In their report to Pope Hadrian, the legates condemn pagans who have "superimposed most hideous cicatrices" (i.e gotten tattoos), likening the pagan practice to coloring oneself "with dirty spots". The location of the visit indicates that these are Anglo-Saxon tattoos rather than Celtic, but some scholars have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have adopted the practice from the Brittonic Celts (MacQuarrie 1997).

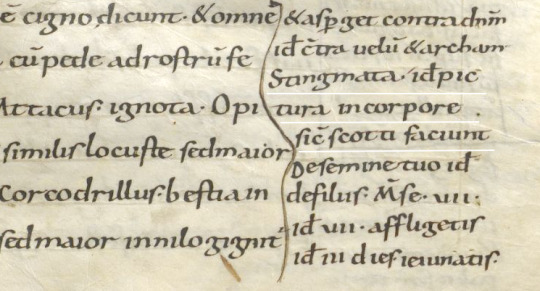

A gloss in the margin of the late 9th c. German manuscript Fulda Aa 2 defines Stingmata [sic] as "put pictures on the bodies as the Irish (Scotti) do." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997).

Fulda Aa 2 folio 43r The gloss is on the left underlined in white.

Irish Written Sources:

Irish texts that mention tattoos date to approximately 700-900 CE, although some of them have glosses that may be slightly later, and some of them cannot be precisely dated.

The first text source is a poem known in English as "The Caldron of Poesy," written in the early 8th c. (Breatnach 1981). The poem is purportedly the work of Amairgen, ollamh of the legendary Milesian kings. In the first stanza of the poem, he introduces himself saying, "I being white-kneed, blue-shanked, grey-bearded Amairgen." (translation from Breatnach 1981)

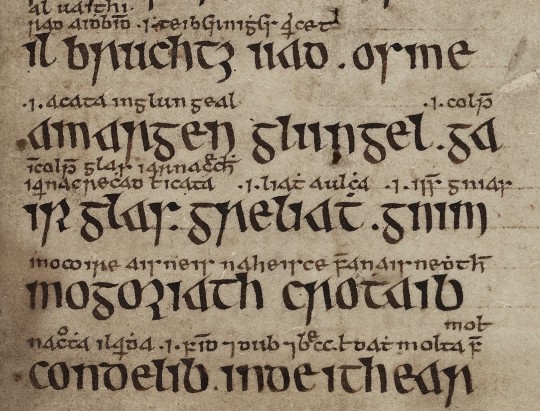

The text of the poem with interline glosses from Trinity College Dublin MS 1337/1

The word garrglas (blue-shanked) has a Middle Irish (c. 900-1200) gloss added by a later scribe, defining garrglas as: "a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank" (Breatnach 1981).

Although Amairgen was a mythical figure, the position ollamh was not. An ollamh was the highest rank of poet in medieval Ireland, considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1981). The fact that a man of such esteemed status introduces himself with the descriptor 'blue-shanked' suggests that tattoos were a respectable thing to have in early medieval Ireland.

The leg tattoos are also mentioned c. 900 CE in Cormac’s Glossary. It defines feirenn as "a thong which is about the calf of a man whence ‘a tattooed thong is tattooed about [the] calf’" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

The Irish legal text Uraicecht Becc, dated to the 9th or early 10th c., includes the word creccoire on a list of low-status occupations (Szacillo 2012, MacNeill 1924). A gloss defines it as: crechad glass ar na roscaib, a phrase which Szacillo interprets as meaning "making grey-blue sore (tattooing) on the eyes" (2012). This sounds rather strange, but another early Irish text clarifies it.

The Vita sancti Colmani abbatis de Land Elo written around the 8th-9th centuries (Szacillo 2012) contains the following episode:

On another time, St Colmán, looking upon his brother, who was the son of Beugne, saw that the lids of his eyes had been secretly painted with the hyacinth colour, as it was in the custom; and it was a great offence at St Colmán’s. He said to his brother: ‘May your eyes not see the light in your life (any more). And from that hour he was blind, seeing nothing until (his) death. (translation from Szacillo 2012).

The original Latin phrase describing what so offended St Colmán "palpebre oculorum illius latenter iacinto colore" does not contain the verb paint (pingo). It just says his eyelids were hyacinth (blue) colored. This passage together with the gloss from the Uraicecht Becc implies that there was a custom of tattooing people's eyelids blue in early medieval Ireland. A creccoire* was therefore a professional eyelid tattooer or a tattoo artist.

A possible third reference to tattooing the area around the eye is found in a list of Old Irish kennings. The kenning for the letter 'B' translates as 'Beauty of the eyebrow.' This kenning is glossed with the word crecad/creccad (McManus 1988). Crecad could be translated as cauterizing, branding, or tattooing (eDIL). McManus suggests "adornment (by tattooing) of the eyebrow" as a plausible interpretation of how crecad relates to the beauty of the eyebrow (1988). The precise date of this text is not known (McManus 1988), but Old Irish was used c. 600-900 CE, meaning this text is of a similar date to the other Irish references to tattoos.

Kenning of the letter 'b' with gloss from TCD MS 1337/1

There is a sharp contrast between the association of tattoos with a venerated figure in 'The Caldron of Poesy', and their association with low-status work and divine punishment in the Uraicecht Becc and the Vita. This indicates that there was a shift in the cultural attitude towards tattoos in Ireland during the 7th-9th centuries. The fact that a Christian saint considered getting tattoos a big enough offense to punish his own brother with blindness suggests that tattooing might have been a pagan practice which gradually got pushed out by the Catholic Church. This timeline is consistent with the 786 CE report of the papal legates condemning the pagan practice of tattooing in Great Britain (MacQuarrie 1997).

There are some mentions of tattooing in Lebor Gabála Érenn, but the information largely appears to be borrowed from Isidore of Seville (MacQuarrie 1997). The fact that the writers of LGE just regurgitated Isidore's meager descriptions of Pictish and Scottish (ie Irish) tattooing without adding any details, such as the designs used or which parts of the body were tattooed, makes me think that Insular tattooing practices had passed out of living memory by the time the book was written in the 11th century.

*There is some etymological controversy over this term. Some have suggested that the Old Irish word for eyelid-tattooer should actually be crechaire. more info Even if this hypothesis is correct, and the scribe who wrote the gloss on creccoire mistook it for crechaire, this doesn't contradict my argument. The scribe clearly believed that eyelid-tattooer belonged on a list of low-status occupations.

Discussion:

Like Julius Cesar in the last post, Herodian of Antioch c. 208 CE makes some dubious claims of Celtic barbarism, stating that the Britons were: "Strangers to clothing, the Britons wear ornaments of iron at their waists and throats; considering iron a symbol of wealth, they value this metal as other barbarians value gold" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). If the Britons wore nothing but iron jewelry, then why did they have brass torcs and 5,000 objects that look like they're meant to attach to fabric, Herodian?

Brass torc from Lochar Moss, Scotland c. 50-200 CE. Romano-British trumpet brooch from Cumbria c. 75-175 CE. image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Trumpet brooches are a Roman Era artifact invented in Britain, that were probably pinned to people's clothing. more info

Although Herodian and Solinus both make dubious claims, there are enough differences between them to indicate that they had 2 separate sources of information, and one was not just parroting the other. This combined with the fact that we have more-reliable sources from later centuries confirming the existence of tattoos in the British Isles makes it probable that there was at least a grain of truth to their claims of tattooing.

There is a common belief that the name Pict originated from the Latin pictus (painted), because the Picts had 'painted' or tattooed bodies. The Romans first used the name Pict to refer to inhabitants of Britain in 297 CE (Ware 2021), but the first mention of Pictish tattoos came in 402 CE (Carr 2005), and the first explicit statement that the name Pict was derived from the Picts' tattooed bodies came from Isidore of Seville c. 600 CE (MacQuarrie 1997). Unless someone can find an earlier source for this alleged etymology than Isidore, I am extremely skeptical of it.

Summary of the written evidence:

Some time between c. 79 CE (Pliny the Elder) and c. 208 CE (Herodian of Antioch) the practice of body art in Great Britain changed from staining or painting the skin to tattooing. Third century Celtic Briton tattoo designs depicted animals. Pictish tattoos are first mentioned in the 5th century.

The earliest mention of Irish tattoos comes from Isidore of Seville in the early 6th c., but since it seems to have been a pre-Christian practice, it likely started earlier. Irish tattoos of the 8-9th centuries were placed on the area around the eye and on the legs. They were a bluish color. The 8th c. Anglo-Saxons also had tattoos.

Tattooing in Ireland probably ended by the early 10th c., possibly because of Christian condemnation. Exactly when tattooing ended in Great Britain is unclear, but in the 12th c., William of Malmesbury describes it as a thing of the past (MacQuarrie 1997). None of these sources give much detail as to what the tattoos looked like.

The Archaeology of Insular Ink:

In spite of the fact that tattooing was a longer-lasting, more wide-spread practice in the British Isles than body painting, there is less archaeological evidence for it. This may be because the common tools used for tattooing, needles or blades for puncturing the skin, pigments to make the ink, and dishes to hold the ink, all had other common uses in the Middle Ages that could make an archaeologist overlook their use in tattooing. The same needle that was used to sew a tunic could also have been used to tattoo a leg (Carr 2005). A group of small, toothed bronze plates from a Romano-British site at Chalton, Hampshire might have been tattoo chisels (Carr 2005) or they might have been used to make stitching holes in leather (Cunliffe 1977).

Although the pigment used to make tattoos may be difficult to identify at archaeological sites, other lines of evidence might give us an idea of what it was. Although the written sources tell us that Irish tattoos were blue, the popular modern belief that woad was the source of the tattoo pigment is, in my opinion, extremely unlikely for a couple of reasons:

1) Blue pigment from woad doesn't seem to work as tattoo ink. The modern tattoo artists who have tried to use it have found that it burns out of the person's skin, leaving a scar with no trace of blue in it (Lambert 2004).

2) None of the historical sources actually mention tattooing with woad. Julius Cesar and Pliny the Elder mention something that might have been woad, but they were talking about body paint, not tattoos. (see previous post) Isidore of Seville claimed that the Picts were tattooing themselves with "juices squeezed from native plants", but even assuming that Isidore is a reliable source, you can't get blue from woad by just squeezing the juice out of it. In order to get blue out of woad, you have to first steep the leaves, then discard the leaves and add a base like ammonia to the vat (Carr 2005). The resulting dye vat is not something any knowledgeable person would describe as plant juice, so either Isidore had no idea what he was talking about, or he is talking about something other than blue pigment from woad.

In my opinion, the most likely pigment for early Irish and British tattoos is charcoal. Early tattoos found on mummies from Europe and Siberia all contain charcoal and no other colored pigment. These tattoos range in date from c. 3300 BCE (Ötzi the Iceman) to c. 300 CE (Oglakhty grave 4) (Samadelli et al 2015, Pankova 2013).

Despite the fact that charcoal is black, it tends to look blueish when used in tattoos (Pankova 2013). Even modern black ink tattoos that use carbon black pigment (which is effectively a purer form of charcoal) tend to look increasingly blue as they age.

A 17-year-old tattoo in carbon black ink photographed with a swatch of black Sharpie on white printer paper.

The fact that charcoal-based tattoo inks continue to be used today, more than 5,000 years after the first charcoal tattoo was given, shows that charcoal is an effective, relatively safe tattoo pigment, unlike woad. Additionally, charcoal can be easily produced with wood fires, meaning it would have been a readily available material for tattoo artists in the early medieval British Isles. We would need more direct evidence, like a tattooed body from the British Isles, to confirm its use though.

As of June 2024, there have been at least 279 bog bodies* found in the British Isles (Ó Floinn 1995, Turner 1995, Cowie, Picken, Wallace 2011, Giles 2020, BBC 2024), a handful of which have made it into modern museum collections. Unfortunately, tattoos have not been found on any of them. (We don't have a full scientific analysis for the 2023 Bellaghy find yet though.)

*This number includes some finds from fens. It does not include the Cladh Hallan composite mummies.

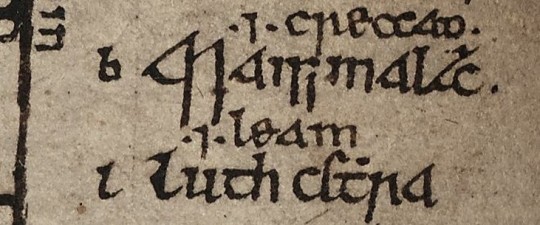

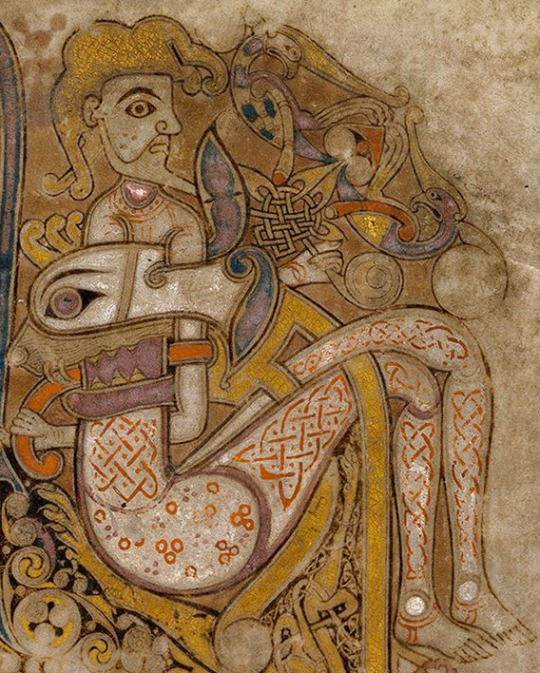

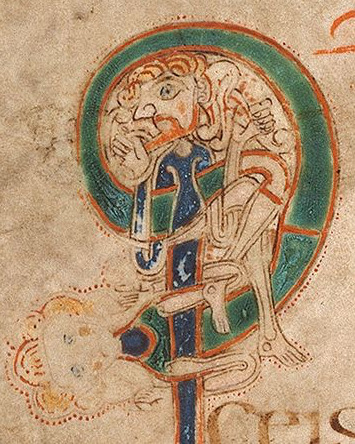

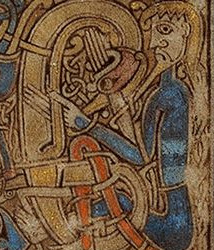

Tattoos in period art?

It has been suggested that the man fight a beast on Book of Kells f. 130r may be naked and covered in tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). However, Dress in Ireland author Mairead Dunlevy interprets this illustration as a man wearing a jacket and trews (Dunlevy 1989). Looking at some of the other figures in the Book of Kells, I agree with Dunlevy. F. 97v shows the same long, fitted sleeves and round neckline. F. 292r has long, fitted leg coverings, presumably trews, and also long sleeves. The interlace and dot motifs on f. 130r's legs may be embroidery. Embroidered garments were a status symbol in early medieval Ireland (Dunlevy 1989).

Left to right: Book of Kells folios 130r, 97v, 292r

A couple of sculptures in County Fermanagh might sport depictions of Irish tattoos. The first, known as the Bishop stone, is in the Killadeas cemetery. It features a carved head with 2 marks on the left side of the face, a double line beside the mouth and a single line below the eye. These lines may represent tattoos.

The second sculpture is the Janus figure on Boa Island. (So named because it has 2 faces; it's not Roman.) It has marks under the right eye and extending from the corner of the left eye that may be tattoos.

I cannot find a definitive date for the Bishop stone head, but it bears a strong resemblance to the nearby White Island church figures. The White Island figures are stylistically dated to the 9th-10th centuries and may come from a church that was destroyed by Vikings in 837 CE (Halpin and Newman 2006, Lowry-Corry 1959). The Janus figure is believed to be Iron Age or early medieval (Halpin and Newman 2006).

Conclusions:

Despite the fact that tattooing as a custom in the British Isles lasted for more than 500 years and was practiced by at least 3 different cultures, written sources remain our only solid evidence for it. With only a dozen sources, some of which probably copied each other, to cover this time span, there are huge gaps in our knowledge. The 4th century Picts may not have had the same tattoo designs, placements or reasons for getting tattooed as the 8th c. Irish or Anglo-Saxons. These sources only give us fragments of information on who got tattooed, where the tattoos were placed, what they looked like, how the tattoos were done, and why people got tattooed. Further complicating our limited information is the fact that most of the text sources come from foreigners and/or people who were prejudiced against tattooing, which calls their accuracy into question.

'The Cauldron of Posey' is one source that provides some detail while not showing prejudice against tattoos. The author of the poem was probably Christian, but the poem appears to have been written at a time when Pagan practices were still tolerated in Ireland. I have a complete translation of the poem along with a longer discussion of religious elements here.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

BBC (2024). Bellaghy bog body: Human remains are 2,000 years old https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-68092307

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowie, T., Pickin, J. and Wallace, T. (2011). Bog bodies from Scotland: old finds, new records. Journal of Wetland Archaeology 10(1): 1–45.

Cunliffe, B. (1977) The Romano-British Village at Chalton, Hants. Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society, 33(1977), 45-67.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

eDIL s.v. crechad https://dil.ie/12794

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Halpin, A., Newman, C. (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://archive.org/details/irelandoxfordarc0000halp/page/n3/mode/2up

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Lambert, S. K. (2004). The Problem of the Woad. Dunsgathan.net. https://dunsgathan.net/essays/woad.htm

Lowry-Corry, D. (1959). A Newly Discovered Statue at the Church on White Island, County Fermanagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 22(1959), 59-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20567530

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

McManus, D. (1988). Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings. Ériu, 39(1988), 127-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024135

Ó Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Pankova, S. (2013). One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD. Zurich Studies in Archaeology, 9(2013), 75-86.

Samadelli, M., Melisc, M., Miccolic, M., Vigld, E.E., Zinka, A.R. (2015). Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16(2015), 753–758.

Story, Joanna (1995). Charlemagne and Northumbria : the in

fluence of Francia on Northumbrian politics in the later eighth and early ninth centuries. [Doctoral Thesis]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1460/

Szacillo, J. (2012). Irish hagiography and its dating: a study of the O'Donohue group of Irish saints' lives. [Doctoral Thesis]. Queen's University Belfast.

Turner, R.C. (1995). Resent Research into British Bog Bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 221–34). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Ware, C. (2021). A Literary Commentary on Panegyrici Latini VI(7) An Oration Delivered Before the Emperor Constantine in Trier, ca. AD 310. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Literary_Commentary_on_Panegyrici_Lati/oEwMEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

#early medieval#roman era#pict#tattoos#ancient celts#apologies to people who wanted a shorter post#archaeology#art#anecdotes and observations#statutes and laws#irish history#gaelic ireland#medieval ireland#anglo saxon#insular celts#romano british

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Celtic Nations

by Thessiz

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hellenistic sculptor: Epigonus (Greek: Ἐπίγονος), born in Pergamon, Türkiye

Ludovisi Gaul (The Galatian Suicide), 2nd century AD

National Roman Museum – Palazzo Altemps, Rome

This dramatic statue epitomizes the mixing of cultures in the Hellenistic Age. The statue is a Roman copy in marble of a now lost Greek bronze original made at Pergamum in Anatolia by a Greek sculptor. The artist tells the tragic story of a defeated Celt (Gaul). Rather than be captured alive, he has just killed his wife and is at the precise moment of taking his own life. In typically Hellenistic style, the artist combines anatomical accuracy with psychological agony.

#The west encounters & transformations third edition#Hellenistic#Epigonus#greek#pergamon#turkey#classical art#ludovisi gaul#the galatian suicide#gaul#gaulish#celtic#celt#germanic tribes#art#fine art#european art#europe#european#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#western civilization#the west#sculpture#statue#male figure#galatian celt#marble statue#marble

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween originated from the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the transition from the harvest season to winter. Celts believed that on this night, the boundary between the living and the dead blurred. To ward off spirits, they lit bonfires and wore costumes. Over time, it evolved into modern Halloween traditions.

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ancient Celtic Ritual of Killing a Sword,

During the early iron age up to the rise of the Roman Empire the ancient Celts dominated most of Europe, their tribal societies stretching from Spain in the west to Turkey in the east. One ancient Cetlic tradition was the ritual of “killing” the sword of a deceased chieftain or warrior for burial. Often the sword would be heated, then bent into either a circle or “S” shape thus making it irreparable and useless. In hundreds of Celtic graves throughout Europe such ritually killed swords have been uncovered, one of the most well preserved being a iron sword uncovered near Oss in the Netherlands dating to 700 BC.

There are many possible reasons such a ritual was done by the ancient Celts. The sword could have been killed as a ritual sacrifice to speed the soul of the deceased into the afterlife. Indeed a sword would have made an excellent sacrifice considering the expense and labor needed to craft a quality iron sword in that age. In addition, it may have been a special honor for a particularly brave warrior, and while the warrior rests peacefully in death, likewise his sword should be permanently retired. Kind of like how today we retire the jersey of a famous athlete who passes away. Finally, killing the sword may have a more practical and down to earth purpose, to make it useless if uncovered by thieves and grave robbers.

By around the 1st century AD most Celtic tribes had been overrun by Germanic peoples or conquered and assimilated by the Roman Empire. However the tradition of sword killing continued with many German tribes, and during the early Middle Ages was commonly practiced by the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings.

707 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every day I get closer to writing a long essay on how the constructed racial identity of 'Celt' is utter tosh and subsequently doing more harm than good in the Welsh Independence movement.

#people out here sounding like Britain First wankers but for Wales instead#luke's originals#celts#celticist#cymblr

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scenic Views of Ireland

According to one legend, Ireland takes its name from the Gaelic Eire, derived from Eriu, the daughter of the Mother Goddess Ernmas of the mystical Tuatha De Danaan and, for anyone who has spent any time there, this seems fitting in explaining the enchanting beauty of the land.

Continue reading...

137 notes

·

View notes