#Cretaceous fish fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Fossil Chalk Fish Scales (Osteichthyes) | Grey Chalk Cretaceous Clyde Sussex UK | Genuine Specimen with COA

Own a rare and scientifically valuable specimen of fossil fish scales (Osteichthyes) from the Grey Chalk Formation of the Cretaceous period, collected in Clyde, Sussex, UK. These scales represent part of the bony fish group (Osteichthyes), a major vertebrate lineage that dominated Mesozoic marine environments.

Fossil Type: Fish Scales (Osteichthyes – Bony Fish)

Geological Period: Late Cretaceous (~100.5 to 89.8 million years ago)

Formation: Grey Chalk Formation

Location: Clyde, Sussex, United Kingdom

Scale Rule: Squares/Cube = 1cm (Please refer to the photo for full sizing)

Specimen: The actual specimen in the listing photo is the one you will receive

Authenticity: All of our fossils are 100% genuine specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity

Geological and Paleontological Context

These fossil fish scales belonged to Osteichthyes, or bony fish, a major group of marine vertebrates that thrived in the Cretaceous seas. The Grey Chalk is known for preserving delicate microfossils, vertebrate remains, and marine invertebrates from shallow, warm seas rich in calcium carbonate sediments.

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned bony fishes)

Geological Stage: Most likely Cenomanian stage (~100.5–93.9 Ma), based on regional stratigraphy of the Grey Chalk

Depositional Environment: Calm, shallow marine shelf with low-energy sedimentation; fossilisation occurred within fine calcareous sediments of the chalk sea

Morphological Features: Small, shiny or mineralised scales often showing fine ridges, growth rings, or peg-and-socket articulation patterns typical of actinopterygian fishes

Notable: Fossil fish remains in the Grey Chalk are rare compared to invertebrate fossils, making vertebrate microfossils like these valuable for collectors and paleontologists

Biozone: May be associated with the Lower to Middle Cenomanian ammonite or inoceramid zones (e.g., Mantelliceras or Inoceramus zones)

Identifier: Osteichthyan microremains have been recorded in UK chalk studies since the 19th century; formal identification to genus level often requires microscopic examination

Why This Fossil is Special

Fossil fish scales like these are a window into the vertebrate life of the Cretaceous chalk seas—often overlooked yet scientifically important. These remains can be used to reconstruct fish diversity and ecology in ancient marine ecosystems.

Why Buy From Us?

100% genuine fossil with Certificate of Authenticity

The exact item shown is the one you’ll receive

Carefully sourced from reputable UK fossil sites

Excellent for microfossil collectors, educators, and vertebrate paleontology enthusiasts

Own a piece of ancient marine vertebrate history with this Osteichthyes fossil fish scale specimen from the Grey Chalk of Clyde, Sussex—a rare glimpse into bony fish evolution from over 90 million years ago.

#fossil fish scales#Osteichthyes fossil#chalk fish fossil#Cretaceous fish fossil#Grey Chalk fossil#Clyde Sussex fossil#UK fish fossil#bony fish fossil#fossil with certificate#certified fossil#genuine fossil#prehistoric fish scale#natural history fossil#microfossil#Cretaceous marine life#vertebrate fossil

0 notes

Text

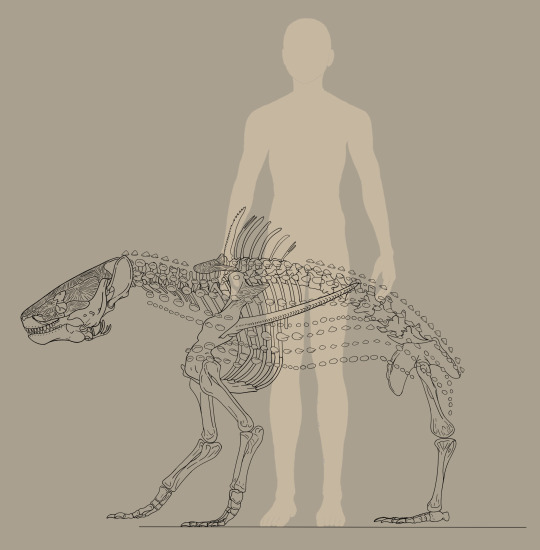

Spinosaurus drama is cool and things, but do you know what's even cooler? Better fossils of animals that lived with Spinosaurus!

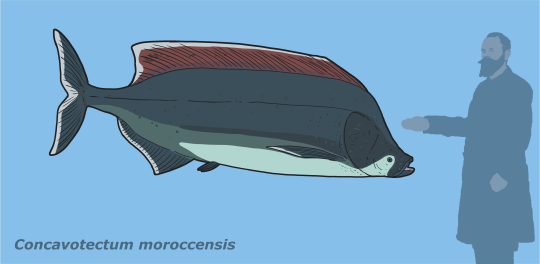

There is a new specimen of Concavotectum currently on display in Tuscon. BigSkyFossils took some photos of it and I had to doodle it! It's been a while since I did a tselfatiform and now we have finally an idea how the postcranium looked like!

So far we only had a few fragments and this pretty good skull. As some people noted though, the eye is reconstructed in the wrong corner.

#sciart#paleoart#paleostream#palaeoblr#cretaceous#spinosaurus#kem kem#morocco#fossil fish#concavotectum

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Fossil Friday! Let’s swim back in time about 85 million years to the Late Cretaceous to meet Xiphactinus, a gigantic predatory fish. This species could reach lengths of 17 ft (5.2 m) and was capable of swallowing a 6-ft- (2-m-) long fish whole! The Museum’s Xiphactinus fossils come from Logan County, Kansas, which is home to 70-ft- (21.3-m-) tall sedimentary formations. Though that might not sound like an ideal home for an ocean-dweller, the entire area was covered by a vast inland sea during the Cretaceous. See Xiphactinus in the Museum’s Hall of Vertebrate Origins!

Photo: Image no. ptc-6634 © AMNH (taken 1996)

#science#amnh#museum#fossil#nature#natural history#animals#fact of the day#did you know#fish#paleontology#late cretaceous#cretaceous#sea creatures#marine biology#marine animals#natural history museum#american museum of natural history

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

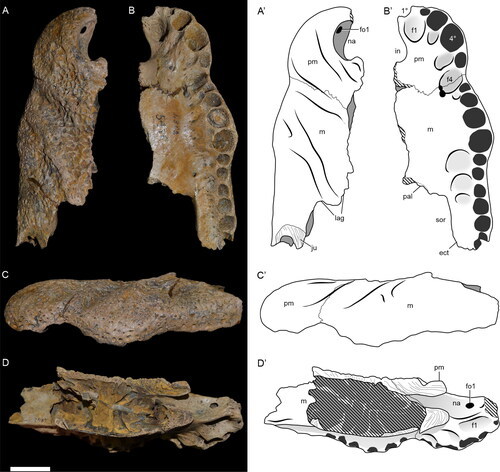

A partial Cretaceous coelacanth jaw of an Axelrodichthys lavocati from the Kem Kem Group in Hassi Zguilma, Morocco. This species of mawsoniid coelacanthiform was formally, and may still be, assigned to the genus Mawsonia. These giant lobe-finned fish were likely a vital food source for the larger piscivorous predators in the deposit such as Spinosaurus, Sigilmassasaurus, and Elosuchus.

#fish#coelacanth#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#axelrodichthys#mawsonia#mawsoniidae#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#fossil friday#fossilfriday#アクセルロディクティス#マウソニア#シーラカンス#化石#古生物学#マウソニア科

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yutyrannus by Reiimon.

#paleoart#paleontology#dinosaur#theropod#yutyrannus#tyrannosaur#feathered dinosaurs#cretaceous#fossil#fish#ice#cold weather

494 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pteranodon - a large Late Cretaceous pterosaur with wingspans over 6 meters. Known for its sexual dimorphism, males had long, backward-facing crests and were significantly larger than females, whose crests and body sizes were smaller. Interestingly, not all males had large crests; only the largest, fully mature males displayed them. With female fossils outnumbering males 2:1, Pteranodon was likely polygynous, with dominant males mating with multiple females that took care of young, like elephant seals.

Pteranodon lacked teeth, a trait shared by many large Cretaceous pterosaurs. As a piscivore, it fed mainly on fish. Strong neck muscles and the ability to take off from water suggest it hunted by diving, similar to modern seabirds like pelicans and gannets.

With light bones and long wings, Pteranodon was adapted for dynamic and thermal soaring, enabling it to cover great distances with ease. This efficient flight likely expanded its hunting grounds and may have facilitated migration, similar to modern storks and condors.

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Charadriiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of birds are the diverse Charadriiformes, collectively called “shorebirds”. This large order contains the families Burhinidae (“stone-curlews” and “thick-knees”), Pluvianellidae (“Magellanic Plover”), Chionidae (“sheathbills”), Pluvianidae (“Egyptian Plover”), Charadriidae (“plovers”), Recurvirostridae (“stilts” and “avocets”), Ibidorhynchidae (“Ibisbill”), Haematopodidae (“oystercatchers”), Rostratulidae (“painted-snipes”), Jacanidae (“jacanas”), Pedionomidae (“Plains-wanderer”), Thinocoridae (“seedsnipes”), Scolopacidae (“sandpipers”, “snipes”, “curlew”, and kin), Turnicidae (“buttonquails”), Dromadidae (“Crab-plover”), Glareolidae (“coursers” and “pratincoles”), Laridae (“gulls”, “terns”, “skimmers”, and kin), Stercorariidae (“skuas”), and Alcidae (“auks”, “puffins”, “guillemots”, and kin).

Charadriiformes are small to medium-large birds that typically live near water, however, some live in the open sea, some live in dense forest, and some living in deserts. Most eat small animals ranging from invertebrates to fish to other birds. The order was formerly divided into three suborders based on behavior, the “waders”, the “gulls”, and the “auks”, but these three groups were paraphyletic. However, they represent a good summary of the main forms charadriiformes can take. The “waders” are generally long-legged, long-beaked birds which tend to feed by probing in the mud or picking items off the surface in both coastal and freshwater environments (however, terrestrial shorebirds like the Woodcock [Scolopax minor] and thick-knees [family Burhinidae] would also be considered “waders”). The “gulls” are generally larger species which catch fish from the sea, scavenge, or steal food from other animals. The “auks” are coastal species which nest on sea cliffs and dive underwater to catch fish, on flipper-like wings that can swim as well as fly. Now, it is generally understood that the auks are closer related to the gulls than any other family, and birds traditionally considered “waders” exist in all three suborders. Charadriiformes are one of the most, if not the most, widely dispersed bird orders, living on every continent and in almost every habitat.

Charadriiformes demonstrate a larger diversity of reproduction strategies than do most other bird orders (see propaganda below the cut for more). In most species, both parents take care of the young, but in some, the father is the main caretaker. Some breed and raise young in large colonies, while others nest alone.

Alongside the waterfowl, the Charadriiformes are the only other order of modern bird to have an established fossil record within the Late Cretaceous, living alongside the other dinosaurs. The modern groups of charadriiformes emerged around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary, roughly 35–30 million years ago.

Propaganda under the cut:

Many of the “stone-curlews” or “thick-knees” (family Burhinidae) are nocturnal, singing their eerie wailing songs at night. Suiting their nocturnal habits, they have very large, yellow eyes. They are effective hunters of insects, and some farmers will keep tamed thick-knees around their fields for pest control.

Like flamingos, the rare Magellanic Plover (Pluvianellus socialis) lives and breeds near saline lakes.

The unique Sheathbills (genus Chionis) are the only Antarctic birds without webbed feet.

Sheathbills and the Spur-winged Lapwing (Vanellus spinosus) have rudimentary spurs on their “wrists”, in place of wing claws, which they use for defense.

The “Trochilus” or “Trochilos”, sometimes called the “Crocodile Bird”, is a mythical bird first described by Herodotus (c. 440 BC), and later by Aristotle, Pliny, and Aelian, which was supposed to have been in a symbiotic relationship with the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), supposedly cleaning parasites and debris from the crocodile’s mouth and teeth. Various charadriiformes have been suggested as the inspiration for the Trochilus, including the Spur-winged Lapwing and Egyptian Plover (Pluvianus aegyptius). These birds are the most likely to feed around basking crocodiles, and tend to be tolerated by them, but this “tooth-cleaning” behavior has never been witnessed in the modern day. Nevertheless, the legend has become so prominent that these birds are sometimes still used as examples of symbiotic relationships!

The European Golden Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) spends its summers in Iceland, and in Icelandic folklore, the appearance of the first plover in the country means that spring has arrived. The Icelandic media always covers the first plover sighting.

The avocets (genus Recurvirostra) (image 2) are some of the only birds with upturned beaks. They use their strange beaks to feed on small invertebrates such as brine shrimp (genus Artemia) and brine fly (family Ephydridae) larvae.

The unique Ibisbill (Ibidorhyncha struthersii) has evolved a convergent appearance to the unrelated Ibises (subfamily Threskiornithinae), which are Pelecaniformes. Its long, downward-curved bill is used similarly to the ibises, as it probes under rocks or gravel for aquatic insect larvae.

Another charadriiform to convergently evolve with a pelecaniform is the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea). While it is the size of a typical sandpiper, it has the spoon-shaped bill of a Spoonbill (genus Platalea). It has a similar feeding behavior to spoonbills, moving its bill side-to-side as it walks forward with its head down. However, this sandpiper typically feeds on tundra mosses, as well as small animals like mosquitoes, flies, beetles, and spiders, as well as brine shrimp occasionally. The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is critically endangered, and its population has been decreasing since the 1970s. It is estimated the species may become extinct in 10–20 years if its habitat is not protected. The Spoon-billed Sandpiper was the milestone 13,000th animal photographed for Joel Sartore’s The Photo Ark.

While oystercatchers (genus Haematopus) are monogamous and tend to return to the same nesting site every year, some have been observed “egg dumping”, laying their eggs in the nests of other birds such as gulls.

The Jacanas (family Jacanidae) (image 4) are sometimes referred to as “Jesus Birds” or “Lily Trotters” due to their highly elongated toes and toenails that allow them to spread out their weight while foraging on floating vegetation, giving them the appearance of walking on water. They are one of the rare groups of birds in which females are larger, and several species maintain harems of males in the breeding season with males solely responsible for incubating eggs and taking care of the chicks.

A “snipe hunt” is a type of practical joke or hazing, in existence in summer camps and scout groups in North America as early as the 1840s, in which an unsuspecting newcomer is duped into trying to catch an elusive animal called a snipe, a creature whose description varies. However, snipes (three separate genera in the family Scolopacidae) are actual birds, who search for invertebrates in marshland mud with their long, sensitive bills, and are highly alert. They would be hard to catch in a pillow case.

The Ruff (Calidris pugnax) is notable for having 4 separate sexes: 1 female and 3 types of male. The most common male, called the “territorial male” has a black or chestnut ruff, is much larger than the female, and stakes out a small mating territory in the lek. They perform elaborate displays that include wing fluttering, jumping, standing upright, crouching with their ruff erect, or lunging at rivals. The second type of male is the “satellite male”, which have white or mottled ruffs, are larger than females but smaller than territorial males, and do not occupy territories. Satellite males enter leks and attempt to mate with the females visiting the territories occupied by territorial males. Territorial males tolerate the satellite males because, although they are competitors for mating with the females, the presence of both types of male on a territory attracts additional females. The rarest type of male is the cryptic male, or "faeder", which permanently mimics the females in both size and plumage. Faeders migrate with the larger males and spend the winter with them, but use their appearance to “sneak” into leks and gain access to females. Females often seem to prefer mating with faeders to the more common males, and those males also copulate with faeders (and vice versa) relatively more often than with females. Homosexual copulations may attract females to the lek, like the presence of satellite males. Satellite males seem to be more attracted to faeders, and in homosexual encounters, the faeders are usually “on top”, suggesting that the satellite males know their true identity. The behaviour and appearance of each male Ruff remains constant through its adult life, and is determined by genetics.

The unique buttonquails (family Turnicidae) convergently evolved the small, round shape of the galliform quails. Unlike true quails, the female buttonquail is the more richly colored of the sexes. Both sexes cooperate in building a nest in the earth, but normally only the male incubates the eggs and tends the young, while the female may go on to mate with other males.

The stork-like Crab-plover (Dromas ardeola) is unique among waders for the shape of its bill, specialized for eating crabs, and for making use of ground warmth to aid the incubation of its eggs. The nest burrow temperature is optimal due to solar radiation and the parents are able to leave the nest unattended for as long as 58 hours, protected by large colonies of up to 1,500 pairs. The chicks are also unique for for being less precocial than other waders, and are unable to walk and remain in the nest for several days after hatching, having food brought to them. Even once they fledge they have a long period of parental care afterwards.

The skimmers (genus Rynchops) are the only birds which have a built-in underbite, where the lower mandible is longer than the upper. This adaptation allows them to fish in a unique way, flying low and fast over streams, letting their lower mandible skim over the water's surface, ready to snap shut the moment it touches a fish.

The Black Skimmer (Rynchops niger) is the only species of bird known to have slit-shaped pupils.

Gulls, Skimmers, and Noddies can see ultraviolet light.

The snow-white, pigeon-like Ivory Gull (Pagophila eburnea) breeds in the high Arctic and is an opportunistic scavenger. It has been known to follow Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) and other predators to feed on the remains of their kills.

Some species of gull, such as the Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla) and Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) have adapted to live alongside humans in places where humans have overtaken their habitat. These gulls have little fear of humans, and will pirate food from them just as they would any other animal.

Auks are superficially similar to penguins, having black-and-white colours, upright posture, and adaptations for swimming underwater. However, they are an example of convergent evolution, and are not closely related to penguins. Auks fill the niche of penguins around the arctic, while penguins fill the niche of auks around the antarctic.

In fact, the extinct, flightless Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) was the original “penguin”. Penguin was the Spanish, Portuguese and French name for the species, derived from the Latin pinguis, meaning "plump". The penguins of the Southern Hemisphere were named after it because of their similar appearance and flightlessness. The last two confirmed Great Auks were killed on Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, on June 3, 1844.

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Crocs of 2024

Another year another list of new fossil crocodilians that greatly expand our knowledge of Pseudosuchia across deep time. Happy to say that this is my third time doing this now, so I'm not going to bog you down with the details and get right into it.

Benggwigwishingasuchus

Our first entry, sorted by geological age of course, is Benggwigwishingasuchus eremicarminis (desert song fishing crocodile) from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of Nevada. It was a member of the clade Poposauroidea, which some of you might recognize as also containing such bizarre early croc cousins like Arizonasaurus and Effigia. Also notable about Benggwigwishingasuchus is that it was found in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation. Why is that notable? Well the Fossil Hill Member preserves an environment deposited 10 km off the Triassic coastline and also yielded fossils of animals like Cymbospondylus, the giant ichthyosaur. Despite this however, Benggwigwishingasuchus shows no obvious signs of having been a swimmer or diver. Instead, its been hypothesized that it was simply foraging around the coast and might have been washed out to sea.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe (@knuppitalism-with-ue) and Jorge A. Gonzalez

Parvosuchus

Fast forward some 5 million years to the Ladinian - Carnian of Brazil, specifically the Santa Maria Formation. Here you'll find the one new genus on the list I did not write the wikipedia page for: Parvosuchus aurelioi (Aurélio's Small Crocodile). With only a meter in length, Parvosuchus is amongst the smallest pseudosuchians of the year and a member of the aptly named Gracilisuchidae. Santa Maria was actually home to multiple pseudosuchians, including the mighty Prestosuchus (and its possible juvenile form Decuriasuchus), the small erpetosuchid Archeopelta and larger Pagosvenator and one more...

Artwork by Matheus Fernandes and Joschua Knüppe

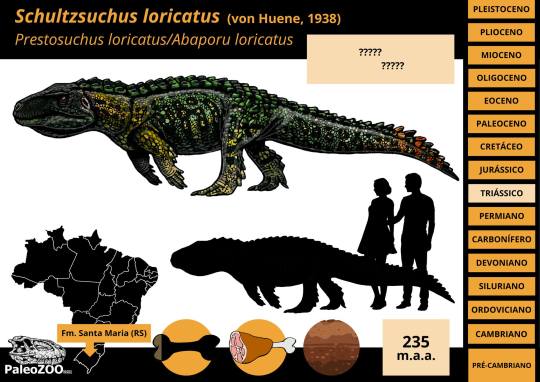

Schultzsuchus

Yup, Santa Maria has been eating good this year. Before the description of Parvosuchus, scientists coined the name Schultzsuchus loricatus (Schultz's Crocodile). Now this one's not entirely new and has long been known under the name Prestosuchus loricatus (by which I mean since 1938). What's interesting is that this new redescription suggests that rather than being a Loricatan, Schultzsuchus was actually an early member of Poposauroidea like Benggwigwishingasuchus. Even if it was no longer thought to be close to Prestosuchus, it was liekly still a formidable predator and among the larger pseudosuchians of the formation.

Artwork by Felipe Alves Elias

Garzapelta

Our last Triassic pseudosuchian and our only aetosaur of the year came to us in the form of Garzapelta muelleri (Mueller's Garza County Shield). It comes from the Late Triassic (Norian) Cooper Canyon Formation of, you guessed it, Garza County, Texas. As an aetosaur, the osteoderms are already regarded as diagnostic, tho unlike some other recent examples there is a little more material to go off from. It's still primarily osteoderms, but at least a good amount and even some ribs.

Artwork by Márcio L. Castro

Ophiussasuchus

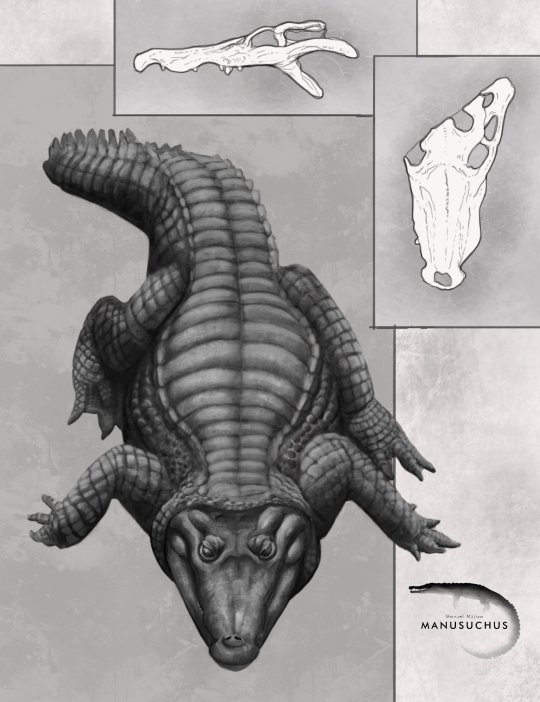

Our only Jurassic newcommer is Ophiussasuchus paimogonectes (Paimogo Beach Swimmer Portuguese Crocodile), but arguably you couldn't find a better posterchild for Jurassic crocodyliforms. This new lad is a goniopholidid from the Kimmeridgian to Tithonian Lourinhã Formation, yup, Europe's Morrison. It's anatomy is perhaps not the most exciting, like other goniopholidids it had a flattened, very crocodilian-esque snout and was likely semi-aquatic like its relatives.

Artwork by @manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

Enalioetes

Another quintessential group of Jurassic crocodyliforms are the metriorhynchoids, however, 2024's only new addition to this clade was actually Cretaceous, specifically from the earliest Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Germany. Like Schultzsuchus, Enalioetes schroederi (Schroeder's Sea Dweller) is new in name only, as fossil material has been found at the latest in 1918 and given the name Enaliosuchus "schroederi" in 1936. This kickstarted a whole series of taxonomic back and forth until the recent redescriptoin finally just gave it a new name and settled things (for now). Looking back I realize that I really need to take the time and fix up the Wikipedia page. Tho I've written its current status, I was kinda limited by being on vacation and never dived into the description section.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Jackosaurus

Varanosuchus

Another Early Cretaceous crocodyliform is Varanosuchus sakonnakhonensis (Monitor Lizard Crocodile from the Sakon Nakhon Province), described from Thailand's Sao Khua Formation. It lived around the same time as Enalioetes, but otherwise couldn't have been more different. Where Enalioetes was fully marine, Varanosuchus was more a land dweller as evidenced by the deep skull and long, slender legs. At the same time, some other features, like its more robust limbs compared to its kin, might suggest that Varanosuchus could have still spent some time in the water like some modern lizards. Tho one might be reminded of Parvosuchus from earlier, Varanosuchus is a much more recent example of small terrestrial croc-relatives, the atoposaurids, which are much closer to todays crocodiles and alligators.

Artwork once again by Manusuchus

Araripesuchus manzanensis

Yet another example of a small, gracile land "crocodile" comes to us in the form of Araripesuchus manzanensis (Araripe Basin Crocodile from the El Manzano Farm). And once again, it belonged to a completely different group, this time the notosuchian family Uruguaysuchidae. Now Araripesuchus is well known as a genus, in part due to the work of Paul Sereno and Hans Larsson (who popularized the names "dog croc" and "rat croc" for two species). Tangent aside, A. manzanensis is known from the upper layers of Argentina's Candeleros Formation, corresponding to the Cenomanian (earliest Late Cretaceous). The same locality also yielded A. buitreraensis, from which A. manzanensis can be distinguished on account of its blunt molariform teeth in the back of its jaw. This dentition, which corresponds to a durophageous diet of hardshelled prey, could explain how it coexisted with the related A. buitrensis at the same locality, allowing the two to occupy different niches. There is a neat little animation done for this animal you can watch here.

Artwork by Gabriel Diaz Yantén

Caipirasuchus catanduvensis

We're staying in South America but moving to Brazil's Adamantina Formation for our next entry: Caipirasuchus catanduvensis (Caipiras Crocodile from Catanduva). This one is a little more recent, tho the age of the Adamantina Formation is a bit of a mess far as I can tell, ranging anywhere from the Turonian to the Maastrichtian. One could also argue that C. catanduvensis is part of the "lanky small croc club" that Parvosuchus, Varanosuchus and A. manzanensis belong to, but I feel that the very short snout helps it stand out from that bunch more easily. Anyhow, Caipirasuchus catanduvensis is a member of Sphagesauridae, related to Armadillosuchus, and herbivorous. What's really interesting tho is that the internal anatomy suggests the presence of resonance chambers not unlike that of hadrosaurs, possibly suggesting that these animals were quite vocal. This could also explain why baurusuchids appear to have had very keen hearing.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Guilherme Gehr

Epoidesuchus

We're staying in the Adamantina Formation for our last Mesozoic croc of the year, Epoidesuchus tavaresae (Tavares' Enchanted Crocodile). Tho also a Notosuchian like Araripesuchus and Caipirasuchus, this one belongs to the family Itasuchidae (or the subfamily Pepesuchinae depending on who you ask), which stand out as being rare examples of semi-aquatic members of this otherwise largely terrestrial group. Epoidesuchus was fairly large for its kin and had long, slender jaws. Like I said, Epoidesuchus and its relatives were likely more semi-aquatic than other notosuchians, something that might explain the relative lack of semi-aquatic neosuchians across Gondwana. They aren't absent mind you, but noticably rarer than they are in the northern hemisphere.

Artwork by Guilherme Gehr

And thus we move into the Cenozoic and towards the end our or little list. From here on out, say goodbye to Notosuchians or other weird crocodylomorphs and get ready for Crocodilia far as the eye can see.

Ahdeskatanka

The first Cenozoic croc we got is Ahdeskatanka russlanddeutsche (Russian-German Alligator), which despite its name comes from North Dakota, specifically the Early Eocene Golden Valley Formation. Ahdeskatanka is similar to many early alligatorines like Allognathosuchus in being small with rounded, globular teeth that suggest that it fed on hardshelled prey. This would have definitely helped avoid competition in the Golden Valley Formation, which also housed a second, similar form not yet named, a large generalist with a V-shaped snout similar to Borealosuchus and the generalized early caiman Chrysochampsa, also large but with a U-shaped snout.

Artwork by meeeeeeee

Asiatosuchus oenotriensis

We had an alligatoroid, so now its time for a crocodyloid. Asiatosuchus has been recognized from the Late Eocene Duero Basin of Spain for a while now, but now we have a name: Asiatosuchus oenotriensis (Asian Crocodile Belonging To The Land Of Wine). Asiatosuchus is a complex genus, most often not really forming a monophyletic clade and likely representing several distinct or at least successive taxa that form the "Asiatosuchus-like complex". Within this complex, A. oenotriensis is thought to have been close-ish to Germany's Asiatosuchus germanicus.

Artwork by Manusuchus

Sutekhsuchus

Rounding out the trio of major crocodilian clades is Sutekhsuchus dowsoni (Set's Crocodile/God of Deception Crocodile), representing our only gavialoid of the year. Originally described as Tomistoma dowsoni in 1920 based on fossil remains from the Miocene of Egypt, Sutekhsuchus has been at times regarded as distinct and at other times lumped into Tomistoma lusitanica. It was one of several early gavialoids to inhabit the coast of the Tethys during the Miocene and appears to have been most closely related to the genus Eogavialis, clading together just outside of the American and Asian gharials. A fun little personal anecdote, I prematurely learned about this one due to a friend highlighting the name in a study on Eogavialis. Never having heard of "Sutekhsuchus" I took to google scholar, where I found a single result: a reference to the then unpublished description, which naturally I ended up eagerly awaiting.

Artwork by Manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

Paranacaiman

Two more and we're done. First, completely arbitrarily, Paranacaiman bravardi (Bravard's Caiman from Parana) from the Miocene Ituzaingo Formation of Argentina. Material of this genus has originally been referred to Caiman lutescens, described in 1912 but now considered a nomen dubium. Paranacaiman is known from limited material only, just the skull table, but that would indicate a "huge" animal. My personal scaling recovered a size of almost 5 meters in length, similar to large black caimans today.

Once again, credit to me

Paranasuchus

Last but not least, Paranasuchus gasparinae (Gasparini's Crocodile from Parana). Coming from the same deposits as Paranacaiman, this one too has been known as a species of Caiman for some time before being assigned its own genus, though it at least got to retain its old species name. Alas, I have not scaled it myself, tho its material is at least more extensive than that of Paranacaiman, including even parts of the snout. A little nitpick because I don't have much to say, but I personally think the name was ill conceived. On its own both Paranacaiman and Paranasuchus are fine names don't get me wrong, but together, coined by the same authors in the same study no less, they strike me as needlessly confusing to non experts. Both are caimans, both are from Parana, so the distinction between "Parana Caiman" and "Parana Crocodile" is entirely arbitrary and doesn't really distinguish them. Not helped by the fact that they are even closely related in the original description. Other than that tho another good addition to our understanding of fossil crocs.

No artwork on this one, but fossil material from Bona et al. 2024

And that wraps up 2024. I hope This post, or my posts throughout the year or even my work on Wikipedia has helped to make these fascinating animals just a little bit more approachable and a massive thanks to all the artists who took their time to create fantastic pieces featuring these incredible animals. Special shout outs to Manusuchus, who diligently illustrated a lot of the featured animals and Joschua Knüppe, who had to listen to me suggest Ahdeskatanka every Sunday for about two months straight now.

Fossil Crocs of 2023

Fossil Crocs of 2022

#paranasuchus#paranacaiman#ahdeskatanka#sutekhsuchus#ophiussasuchus#epoidesuchus#caipirasuchus#araripesuchus#enalioetes#parvosuchus#benggwigwishingasuchus#schultzsuchus#garzapelta#varanosuchus#paleontology#prehistory#palaeoblr#long post#fossil crocs of 2024#paleo#paleonotlogy#crocodilia#crocodylomorpha#pseudosuchia#fossils#2024

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atterran Terrestrial Catfish (also known as whisker fish) are a lineage of non-teleost fish that have successfully transitioned to terrestrial life, like the ancestors of tetrapods on Earth and Atterra.

Like Earth, the oldest currently known catfish fossils date back to the late cretaceous period of Atterra, which, according to Old World archives, was found in the western continent. While the original fossil was lost during The Fall, the surviving data indicates that the fossil was from a species of armored catfish with similar morphological adaptations to modern-day armored catfish. Atterran biologists theorize catfish evolved between 100-110mya at the beginning of the late Cretaceous period or near the end of the middle Cretaceous period. Unlike the terrestrial teleost fish lineages, the ancestors of the terrestrial catfish did not develop within the hollows of Atterra but instead on the evolved deserts of the surface. These basal catfish would move between bodies of water across the desert sands, like the armored catfish of Brazil, to find food and reproduce. Whenever these fish could not find a suitable body of water, they would hunker down in the mud and hibernate until the wet season arrived, bringing more pools for the fish to inhabit.

Over time, during the late cretaceous, as the desert slowly began to become drier and the catfish had to traverse farther and farther to find suitable pools of water, the catfish's branchial tissue behind their gills slowly became more robust. Taking up larger portions of the body behind the head as the gills began to become smaller from less time spent in water. At the same time, the skin of the ancestral terrestrial catfish became thicker and more resistant to water loss, allowing the catfish to spend more time traversing the dunes in search of water or cool places to hide. Eventually, the armor plating of the ancestor's body became less rigid and sparser, allowing the catfish more flexibility as it raffled across the desert, leading the fish to incorporate its tail into its locomotion and utilize it as a powerful springboard to hop forward. As the catfish's gait and locomotion improved, the brachial tissue moved down into the fish's chest cavity to form primitive lungs. The gill arches began to ossify into the ear and hyoid bones to aid the fish in detecting predators and swallowing food. Alongside the new ear bones, the gill cover slowly became less ossified and flexible to turn into external ears.

Terrestrial catfish are believed to have survived the end cretaceous extinction event on Atterra by being generalists that would eat anything they could fit in their mouths and being just armored enough to ward off many potential would-be predators. Like their ancestors, terrestrial catfish still possess mobile venomous dorsal and pectoral spines to ward off predators should their armored hide prove not enough to deter would-be predators. The stings of terrestrial catfish are excruciating and often cause redness and severe swelling around the area of the sting. In some species, tissue necrosis may also occur, making them a dangerous prey item many predators approach with caution when hunting.

#art#artwork#digital art#drawing#illustration#creature#creature art#creature design#monster design#monsters#fantasy art#my art#drawings#digital 2d#digital illustration#digital drawing#digitalart#clip studio paint#artist#sketches#sketch#doodle#skeleton art#skulls#anatomy#fish#speculative ecology#speculative biology#speculative zoology#speculative evolution

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently found out a show I liked is 10 years old now so to not be the oldest thing on this blog I'm talking coelacanths for Wet Beast Wednesday. Coelacanths are rare fish famed for being living fossils. While that term is highly misleading, it is true that coelacanths are among the only remaining lobe-fined fish and were thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago before being rediscovered in modern times.

(image id: a wild coelacanth. It is a large, mostly grey fish with splotches of yellowish scales. Its fins are attached to fleshy lobes. It is seen from the side, facing the top right corner of the picture)

Coelacanth fossils had been known since the 1800s and they were believed to have gone extinct in the late Cretaceous period. That was until December 1938, when a museum curator named Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was informed of an unusual specimen that had been pulled in by local fishermen. After being unable to identify the fish, she contacted a friend, ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith, who told her to preserve the specimen until he could examine it. Upon examining it early next year, he realized it was indeed a coelacanth, confirming that they had survived, undetected, for 66 million years. Note that fishermen living in coelacanth territory were already aware of the fish before they were formally described by science. Coelacanths are among the most famous examples of a lazarus taxon. This term, in the context of ecology and conservation, means a species or population that is believed to have gone extinct but is later discovered to still be alive. While coelacanths are among the oldest living lazarus taxa, they aren't the oldest. They are beaten out by a genus of fly (100 million years old) and a type of mollusk (over 300 million years old).

(image: a coelacanth fossil. It is a dark brown imprint of a coelacanth on white rock. Its skeleton is visible in the imprint)

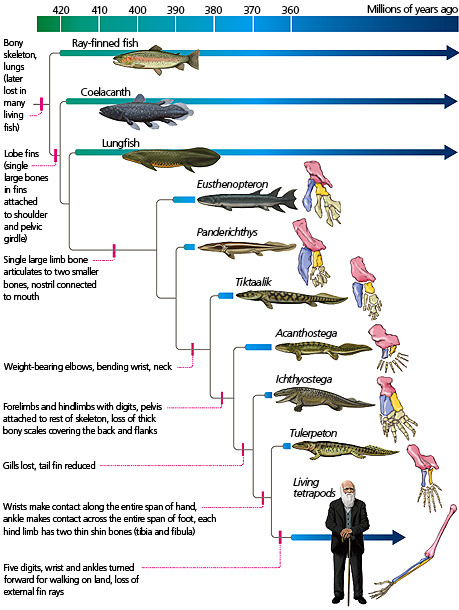

Coelacanths are one of only two surviving groups of lobe-finned fish along with the lungfishes. Lobe-finned fish are bony fish notable for their fins being attached to muscular lobes. By contrast, ray-finned fish (AKA pretty much every fish you've ever heard of that isn't a shark) have their fins attached directly to the body. That may not sound like a big difference, but it actually is. The lobes of lobe-finned fish eventually evolved into the first vertebrate limbs. That makes lobe-finned fish the ancestors of all reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, including you. In fact, you are more closely related to a coelacanth than a coelacanth is to a tuna. Coelacanths were thought to be the closest living link to tetrapods, but genetic testing has shown that lungfish are actually closer to the ancestor of tetrapods.

(image id: a scientific diagram depicting the taxonomic relationships of early lobe-finned fish showing their evolution to proto-tetrapods like Tiktaalik and Ichthyostega, to true tetrapods. Source)

There are two known living coelacanth species: the west Indian ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (L. menadoensis). Both are very large fish, capable of exceeding 2 m (6.6 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lbs). Their wikipedia page describes them as "plump", which seems a little judgmental to me. Their tails are unique, consisting of two lobes above and below the end of the tail, which has its own fin. Their scales are very hard and thick, acting like armor. The mouth is small, but a hinge in its skull, not found in any other animal, allows the mouth to open extremely wide for its size. In addition, they lack a maxilla (upper jawbone), instead using specialized tissue in its place. They lack backbones, instead having an oil-filled notochord that serve the same function. The presence of a notochord is the key characteristic of being a chordate, but most vertebrates only have one in embryo, after which it is replaced by a backbone. Instead of a swim bladder, coelacanths have a vestigial lung filled with fatty tissue that serves the same purpose. In addition to the lung, another fatty organ also helps control buoyancy. The fatty organ is large enough that it forced the kidneys to move backwards and fuse into one organ. Coelacanths have tiny brains. Only about 15% of the skull cavity is filled by the brain, the rest is filled with fat.

(image id: a coalacanth. It is similar to the one on the above image, but this one is blue in color and the head is seen more clearly, showing an open mouth and large eye)

One of the reasons it took so long for coelacanths to be rediscovered is their habitat. They prefer to live in deeper waters in the twilight zone, between 150 and 250 meters deep. They are also nocturnal and spend the day either in underwater caves or swimming down into deeper water. They typically stay in deeper water or caves during the day as colder water keeps their metabolism low and conserves energy. While they do not appear to be social animals, coelacanths are tolerant of each other's presence and the caves they stay in may be packed to the brim during the day. Coelacanths are all about conserving energy even when looking for food. They are drift feeders, moving slowly with the currents and eating whatever they come across. Their diet primarily consists of fish and squid. Not much is known about how they catch their prey, but they are capable of rapid bursts of speed that may be used to catch prey and is definitely used to escape predators. They are believed to be capable of electroreception, which is likely used to locate prey and avoid obstacles. Coelacanths swim differently than other fish. They use their lobe fins like limbs to stabilize their movements as they drift. This means that while coelacanths are slow, they are very maneuverable. Some have even been seen swimming upside-down or with their heads pointed down.

(image: an underwater cave wilt multiple coelacanths residing in it. 5 are clearly visible, with the fins of others showing from offscreen)

Coelacanths are a vary race example of bony fish that give live birth. They are ovoviviparous, meaning the egg is retained and hatches inside the mother. Gestation can take between 2 and 5 years (estimates differ) and multiple offspring are born at a time. It is possible that females may only mate with a single male at a time, though this is not confirmed. Coelacanths can live over 100 years and do not reach full maturity until age 55. This very slow reproduction and maturation rate likely contributes to the rarity of the fish.

(image: a juvenile coelacanth. Its body shape is the same as those of adults, but with proportionately larger fins. There are green laser beams shining on it. These are used by submersibles to calculate the size of animals and objects)

Coelacanths are often described as living fossils. This term refers to species that are still similar to their ancient ancestors. The term is losing favor amongst biologists due to how misleading it can be. The term os often understood to mean that modern species are exactly the same as ancient ones. This is not the case. Living coelacanth are now known to be different than those who existed during the Cretaceous, let alone the older fossil species. Living fossils often live in very stable environments that result in low selective pressure, but they are still evolving, just slower.

(image: a coelacanth swimming next to a SCUBA diver)

Because of the rarity of coelacanths, it's hard to figure out what conservation needs they have. The IUCN currently classifies the west Indian ocean coelacanth as critically endangered (with an estimated population of less than 500) and the Indonesian coelacanth as vulnerable. Their main threat is bycatch, when they are caught in nets intended for other species. They aren't fished commercially as their meat is very unappetizing, but getting caught in nets is still very dangerous and their slow reproduction and maturation means that it is long and difficult to replace population losses. There is an international organization, the Coelacanth Conservation Council, dedicated to coelacanth conservation and preservation.

(image: a coelacanth facing the camera. The shape of its mouth makes it look as though it is smiling)

#wet beast wednesday#coelacanth#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#fish#fishblr#old man fish#lobe-finned fish#sarcopterygii

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily fish fact #792

Palauan primitive cave eel!

This eel species was discovered in a single cave in a single reef off the coast of Palau in 2009. This single species is a sister group to all other extant eels, having diverged from all others 200 million years ago! It retains several primitive features like a retained pseudobranch (the very first reduced gill arch), certain jaw bones, distinct caudal fin rays and toothed gill rakers, some features being even more primitive than those found in eel fossils from the Cretaceous!

#fish#fish facts#fishfact#fishblr#marine biology#marine animals#marine life#sea animals#sea creatures#sea life#zoology#biology#eel#eels#palauan primitive cave eel

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results from the Flocking #paleostream Protobalistium, Ikrandraco, Yangchuanosaurus and Jeholops.

#sciart#paleoart#paleostream#palaeoblr#dinosaur#dinosaurs#jurassic#cretaceous#pterosaur#fish#fossil#triops

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Fossil Friday! Let’s swim back in time about 85 million years to the Late Cretaceous Period to meet Xiphactinus, a gigantic predatory fish. This species could reach lengths of 17 ft (5.2 m) and was capable of swallowing a 6-ft- (2-m-) long fish whole!

The Museum’s Xiphactinus fossils come from Logan County, Kansas, which is home to 70-ft- (21.3 m-) tall sedimentary formations. Though that might not sound like an ideal home for an ocean-dweller, the entire area was covered by a vast inland sea during the Cretaceous.

Photo: Image no. ptc-6634 © AMNH (circa 1996)

#science#amnh#museum#fossil#natural history#nature#paleontology#fish#cretac#xiphactinus#did you know#fact of the day#cool animals#ancient animals#ocean life

829 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Cretaceous lungfish tooth plate of a Neoceratodus africanus or Ceratodus sp. from the Elrhaz Formation in Gadoufaoua, Niger. These giant Mesozoic lungfish would have been prey for genera like Suchomimus tenerensis and Sarcosuchus imperator.

#fish#lungfish#dipnoi#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#neoceratodus#ceratodus#ceratodontidae#neoceratodontidae#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#ネオケラトドゥス#ケラトドゥス#ネオセラトーダス#セラトーダス#ハイギョ#化石#古生物学#ケラトドゥス科

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

A piece of fossilised vomit, dating back to when dinosaurs roamed Earth, has been discovered in Denmark, the Museum of East Zealand said on Monday. The find was made by a local amateur fossil hunter on the Cliffs of Stevns, a UNESCO-listed site south of Copenhagen. He then took the fragments to a museum for examination, which dated the vomit to the end of the Cretaceous era some 66 million years ago. According to experts, the vomit is made up of at least two different species of sea lily, which were likely eaten by a fish that threw up the parts it could not digest.

Continue Reading.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suchomimus, meaning "crocodile mimic," was a spinosaurid dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 125 to 112 million years ago. Its name reflects its crocodile-like skull, which was long and shallow, ideal for catching fish. Discovered in Niger, Africa, by paleontologist Paul Sereno and his team in 1997, the dinosaur's remains were found in the Elrhaz Formation, a region known for its rich fossil deposits. Suchomimus was a large theropod, measuring between 9.5 and 11 meters (31–36 feet) in length and weighing up to 3.8 metric tons. Its forelimbs were robust, equipped with giant claws, and it had a low dorsal sail along its back formed by elongated neural spines.

This dinosaur's diet primarily consisted of fish, supported by its specialized teeth and jaw structure. It likely inhabited fluvial environments, such as floodplains, alongside other dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and aquatic creatures like bony fishes and turtles. Some paleontologists suggest that Suchomimus might be an African species of the European spinosaurid Baryonyx, or even a junior synonym of Cristatusaurus lapparenti, though these classifications remain debated. Its discovery has provided valuable insights into the diversity and adaptations of spinosaurid dinosaurs.

Suchomimus' anatomy suggests it was well-suited for a semi-aquatic lifestyle, wading in shallow waters to hunt prey. Its powerful arms and claws may have been used to catch fish or other small animals. The discovery of Suchomimus has highlighted the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and modern reptiles, showcasing how certain species adapted to specific ecological niches. This fascinating creature continues to be a subject of study, shedding light on the complex ecosystems of the Early Cretaceous.

#art#drawing#illustration#sketch#artwork#artist#dino#dinosaur#dinosaurs#prehistoric#extinct#paleoart#paleontology#theropod#spinosaurid#suchomimus#baryonyx#reptile

25 notes

·

View notes