#Forgotten Realms

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Alliance (PS5)

#Dungeons & Dragons: Dark Alliance (PS5)#dark alliance#drizzt do'urden#forgotten realms#gif : dnd dark alliance 2021#gaming#video games#game gifs#dungeons and dragons#dungeons & dragons#dailygaming#gamingnetwork#Forgotten Realms#[ gif game : mine ]#[ gif ]#gif : dnd#gif : RPG#gameplaydaily#gif : favorite

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galathil

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Definitive Case for a Romantic Reading of Manshoon and Fzoul's Relationship

Allow me to preface this: yes, I'm well aware of what the surface reading of the text says, and that on all levels but physical I am this guy:

Memes aside, this is (finally) the ship meta I’ve been threatening my friends with for months and this blog with for the last week, in which I intend to argue that by canonical text across multiple sourcebooks and novels, one can (and perhaps should) read the dynamic between Manshoon and Fzoul as much more intimate, and indeed potentially romantic, than the intended surface-level reading of the text implies. To this end, what follows will analyze both tabletop sourcebooks, including a published adventure module, and several novels and short stories for what their subtext actually says about the nature of their relationship.

Fair warning: this is long, and continues below the cut to spare your dashes.

Introduction: Shadow, who exactly are Manshoon and Fzoul?

For those of you who haven't spent the last year and a half at least marinating at the bottom of a heap of older Forgotten Realms lore, Manshoon of Zhentil Keep and Fzoul Chembryl are the founders of the Zhentarim, the most infamous espionage, covert ops, and (lately) mercenary organization in the Realms. Manshoon is regarded as one of the most dangerous mortal mages in the region, capable of going toe-to-toe with the likes of Elminster and other Chosen of Mystra; Fzoul began as a powerful priest of Bane and eventually was elevated to the status of Bane’s Chosen. The pair of them comprised two-thirds of the original Inner Circle of the Zhentarim, and led the organization from its founding in 1261 DR to their deaths in 1383 DR. They are first introduced in the original Forgotten Realms Campaign Set boxed set for AD&D 1e, making their initial appearances in the DM’s Sourcebook of the Realms from that set, on pages 22 (Fzoul) and 25/26 (Manshoon), and appear as a set up through D&D 3e. Fzoul's most recent appearance in published tabletop material is in the 4e Campaign Guide, which describes him as having been elevated to the status of an exarch (4e’s demipower equivalent) after his death; Manshoon’s situation is more complicated but at least two of his clones are active as of 5e, one operating covertly in Waterdeep (Waterdeep: Dragon Heist), the other a vampire in Westgate. They're among the longest-running NPCs, antagonistic or otherwise, in the setting. Outside of tabletop sourcebooks, Manshoon and Fzoul make appearances together or separately across a dozen or so novels and short stories, with their first novel appearance in Spellfire, originally published within a year of the Campaign Set’s production.

Officially, source texts claim their relationship is antagonistic, describing them as “[respecting] the power each holds, though each despises the other personally” (Ruins of Zhentil Keep, p. 34), or that “[Manshoon was] hated and mistrusted by his ally Fzoul, [while] Manshoon calmly manipulated the priest as he did all others…” (Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting for 3e, p. 283). However, these self-same texts repeatedly undercut these statements, suggesting implicitly a high degree of interpersonal intimacy and no small amount of trust, which I will dissect in the rest of this essay.

We’ll begin with sourcebook material, which I will be taking chronologically in-universe, analyzing the following texts: Ruins of Zhentil Keep for 2e, which is and remains my primary source, Villains’ Lorebook for 2e, Cloak and Dagger for 2e, and what little is mentioned in the Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting for 3e, with brief dips as relevant into other sources. After this, we’ll turn our attention to a handful of relevant novels and short stories: “Lord of the Darkways”, “So High a Price” (both the original Realms of Infamy publication and the revised version from Best of the Realms 2), and Spellfire and Crown of Fire from the “Shandril’s Saga” series.

Canon gives us very little on Manshoon and Fzoul's early years. Our original description comes from the article “Something is Rotten at the Citadel of the Raven” from Polyhedron #83, published in 1992, but the information is repeated largely unchanged in Ruins of Zhentil Keep, which being the tabletop supplement takes precedence. We don't even have an official birth year given for Fzoul, but given that he and Manshoon are described as “childhood friends” in both sources, he’s likely within a few years of Manshoon’s given birth year of 1229 DR. Manshoon’s father was First Lord of the Council of Lords, while Fzoul is described as “the only child of a minor noble of Zhentil Keep” (Ruins p. 107), which certainly places their formative years in close proximity to one another despite Fzoul's early entry into the priesthood of Bane. In 1258 DR, as the son of a council lord, Manshoon—along with his brother, Asmuth, and a close friend, Chess son of Calkontor—was dispatched from the Keep to prove himself worthy of inheritance. While the lord-princes were abroad, their fathers were slain, and their seats on the council usurped; one of the usurpers, Ulsan Baneservant, was Fzoul's own high priest. Upon their return to the Keep in 1260, Ulsan attempted to have the lord-princes assassinated, and it is only after this—and despite the risk—that Manshoon reached out to Fzoul to secure his aid in deposing Ulsan so Manshoon could reclaim his rightful seat. I've already gone on about this at length on this blog, because I'm normal about them.

In 1263 DR, Fzoul schismatized the Church of Bane. The orthodox stance of the church is that it exists solely to “do Bane’s will, kill his enemies, and bring more followers into the nest” (Ruins, p. 65). Fzoul, described at the time as “an intrepid young priest of middling experience” (p. 65) held a different stance: that “the proper worship of the god of tyranny was to support a tyrant, and the most efficient tyrant around was Manshoon,” (Ruins, p. 107) and that they might “reap great profits” (p. 65) by allying with him. The problem with this, of course, is that Manshoon was only 34 and had held his council seat for just three years at that point, and wouldn't be named First Lord of Zhentil Keep for another 70 years (1334 DR). Regardless, Fzoul's doctrinal difference proved popular—other Banites recognized the benefits of both doctrine and collaboration with the Zhentarim, and his faction waxed as the Orthodoxy under the High Imperceptor waned. Ruins says the High Imperceptor “tolerated Fzoul and his followers, despite what he considered blasphemy by these Banites” up until 1357 DR, though several other sources (to be discussed in greater depth in the novels section) mention multiple attempts on Fzoul and Manshoon’s lives during the decades between 1263 and 1357.

While Ruins of Zhentil Keep is quick to reassure us that the two of them dislike each other, it also describes Fzoul as “careful to remain necessary to and friends with Manshoon” (p. 107), the two of them as having “thrown [their] lots in with [each other]” (p. 67), and that Manshoon considers Fzoul “invaluable” (p. 107). Additionally, Villains’ Lorebook describes them as “as close as two evil men can ever be” (Villains’ Lorebook p. 26).

With that all laid out: the pair of them ran the Zhentarim together in this way for nearly a century before the Godswar in 1358 DR. Both of them are quite lethal—Fzoul is described as being perfectly willing to wade into combat himself, and Manshoon is, as described above, capable of going toe-to-toe with some of the greatest spellscasters in the Realms. If the two of them genuinely wanted each other dead, they're more than capable of killing each other. Additionally, we have an example of a genuinely antagonistic relationship within the Inner Circle of the Zhentarim: Fzoul and Sememmon, the third member of their trio and one of Manshoon's former apprentices. Fzoul and Sememmon's relationship is best described as contentious—an “all-consuming (and time-consuming) obsession” (Ruins of Zhentil Keep p. 112) which has led the two of them to multiple attempts on each other's life, and led Fzoul to “[work] out contingency plans with Manshoon in case Sememmon ever makes a play to depose his former teacher as leader of the Zhentarim.” (Villains’ Lorebook, p. 26)

This is, of course, the point where anyone familiar with the lore goes “wait, hang on, Shadow, didn't Fzoul actually kill Manshoon at one point?”

And well. Yes. He did. Ches 6, 1370 DR.

However. The same source, Cloak and Dagger for 2e, that describes the event and that gives us our nice, clear timeline on the lead-up to the assassination and the beginning of the Manshoon Wars (wherein many of Manshoon's clones awakened at once, were driven mad by it, and fought each other all over the Realms) also calls into question just how voluntary this was on Fzoul's part.

I am speaking, of course, of Iyachtu Xvim, the demipower son of Bane. In the early months of 1369 DR, after the destruction of the northern half of Zhentil Keep by forces commanded by Cyric, Xvim made contact with Fzoul, leading Fzoul to turn to his worship and begin leading holdout Banites and forcibly converted formerly Banite Cyricists into Xvim’s faith as an alternative to Cyric. Concurrent with that initial contact, Xvim also begins possessing Fzoul, beginning in Ches 1369 (Cloak and Dagger, p. 9) and recurring throughout that year to accomplish Xvim’s goals. Under Xvim’s control, Fzoul locates the High Imperceptor in Mulmaster and publicly decries him as a traitor to the faith (Cloak and Dagger p. 11), establishes an alliance with Teldorn Darkhope of Mintar (p. 12) and begins work on the artifact that will eventually become the Scepter of the Tyrant’s Eye (p.12). And on Ches 3, 1370, “Fzoul receives a vision from Xvim, demanding the ‘death of the failed tyrant more interested in money and secrets than might’.” (Cloak and Dagger, p. 13) That is, to say: Manshoon. Additionally, Cloak and Dagger does not fully detail the clash between Manshoon and Fzoul that resulted in Manshoon’s death at his hands—Fzoul may have been possessed at the time, or otherwise forced or coerced into it.

Regardless, what Fzoul chose to do afterwards is also interesting—he lies to his and Manshoon's subordinates, claiming first that “Manshoon suffered grievous injuries in this long night of attacks and magically travelled to Zhentil Keep to convalesce” (p. 13) while “revealing” to select high-ranking individuals that “Manshoon had been driven mad by unknown forces, and they were not to trust or obey him until Fzoul gets the chance to cure him” (p. 14, emphasis mine). The claim of madness is not inaccurate—the clone debacle certainly did drive a number of them mad—but the stated interest in curing that madness does not match up with the assassination attempt. Nor does it match up with Manshoon’s ultimate return to the Zhentarim in 1372—notably, after Xvim’s death and Bane’s resurrection—which Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting for 3e describes as “some kind of secret accommodation” and “having arrived at an understanding” (p. 282, 283). If Fzoul truly wanted Manshoon dead or permanently ousted, why allow him to return at all, let alone give him free access to the resources of the Zhentarim?

As a final point, which fits neatly in none of the above sections, in the Curse of the Azure Bonds module for 1e, we get a description of Fzoul's tower which mentions a portrait of him, Manshoon, and Chess as young men, which is hanging in his dining room (p. 59). By this point, 1357 DR, Fzoul and Manshoon have long since fallen out with Chess, but the portrait remains. Additionally, Manshoon is notorious for hiding his face and disguising himself at all times, to the point where "only those who knew him in his youth know his true face" (that is to say, Fzoul); yet he sat for this portrait, a process that would have taken hours and several days' worth of sittings, and historically speaking was not done by people who were not incredibly close. Make of this what you will.

Having exhausted our sourcebooks, we turn now to the novels and short stories I mentioned above. My sample size here is, admittedly, small—I’ve only been reading the novels since December, and the pair appear together quite infrequently—so I will accept contributions from people who have read other novels or short stories which feature both Manshoon and Fzoul’s in-person appearances. I am also taking book recommendations. Please. As above, we’ll take this chronologically in-universe, noting gaps in publication; the original “So High a Price” was published in 1994, Spellfire and Crown of Fire in 1988 and 1994, while the reprint of “So High a Price” was in 2005, and “Lord of the Darkways” wasn't published until 2010 and features a radical shift Greenwood made in Manshoon’s characterization beginning in the 2000s (in my humble opinion, to the detriment). This section, unfortunately, will be without page numbers; I have only ebook copies rather than physical ones of the sources I reference herein.

The original printing of “So High a Price” (‘94), set in 1334 DR during Manshoon’s bid for the seat of First Lord, features very little in the way of direct Manshoon and Fzoul interactions, but mentions that the two of them are said to “meet often” in secret. During the climactic scene in the council chamber the two indeed work together—while appearing to not be doing so at all—until the conspiracy is outed by Chess and the scene devolves into violence. Afterwards, with their collaboration revealed, Manshoon is openly seen convincing Fzoul to stand down from further violence, “[leaning] over the priest and murmuring a few words” to bid him cease. The 2005 printing includes a new scene between the two of them at the beginning of the short story, where Fzoul calls on Manshoon in the Tower High to discuss their plan. Manshoon speaks openly and honestly with Fzoul about his aims, and is generally solicitous with him, inviting Fzoul to stay and share a glass of wine, which Fzoul declines. The other added scene to note features a coterie of assassins, sent by the High Imperceptor, to target Manshoon—intending to remove him so he cannot continue to fortify Zhentil Keep against them.

“Lord of the Darkways” (‘10, published in Dragon issue #390) is set later in 1334 DR, and focuses on Elminster thwarting Manshoon’s bid to control a portal network leading between Zhentil Keep and Sembia. Before I go any further with this analysis, I would like to note that Manshoon’s interest in and concerns about this network are valid—a portal network controlled by certain powerful merchants of Zhentil Keep is, in fact, a threat to their security, as well as a means for these merchants to cheat the government of Zhentil Keep of the taxes they would owe on imported goods via smuggling—though his…methodology is dubious (and, in my opinion, out of character for Manshoon as he is otherwise portrayed during this period). However, my primary focus at this point is on the scenes where he and Fzoul are on-page together. In the first, he and Fzoul have met over lunch to discuss Manshoon’s bid for control of the portal network; Fzoul is rightly angry with him for acting without telling him first, while Manshoon reassures him that he didn't mean to do so and intends to make sure Fzoul is more involved with the decision-making going forward. Manshoon is charming and solicitous with Fzoul, yet again, for the whole interaction, and is described as “eager” and with “a smile as bright as it was genuine”. Fzoul, for his part, is quickly settled by the explanation, and the pair of them get quite drunk together. In the final scene of the short story, the pair of them face off against Elminster together, and it's made quite clear that without Mystra’s intervention on his behalf they might well have destroyed him.

Lastly, we come to the novels from Shandril's Saga, Spellfire and Crown of Fire. While notably the two of them do little face-to-face interaction in this series, a lot is said around those spaces—namely, their knowledge of each other's works and the way Manshoon behaves towards Fzoul.

Spellfire is thin on the ground for both of them, but it does set up two interesting points. Firstly, the High Imperceptor makes another strike against Zhentil Keep, this time on Fzoul himself—but, notably, states that “[they] cannot move against the traitor Fzoul with Manshoon in the city, or [they] shall know certain defeat,” and indeed only acts against him while Manshoon is missing and presumed dead after a battle with the protagonists. Secondly, I want to note the lead-up to the said battle, namely because it sets up an interesting pattern in Manshoon's behavior that carries out through the rest of Spellfire and into Crown of Fire. I’ve already discussed elsewhere on this blog how I feel about Greenwood's use of female “love interests” for Manshoon—namely, that I don't find them at all believable, and he mostly introduces them just to kill them off—but the one in this series, Symgharyl Maruel (also known as the Shadowsil), is the only one I find plausible as a person Manshoon actually cares for. His involvement in the plot is entirely due to her death—he’s magically notified of it when the protagonists slay her, and immediately drops everything he's doing and leaves Zhentil Keep to go after her. This is not the only time in this series we see him set out to retrieve someone he considers valuable to him: later in Spellfire he intervenes to prevent Sememmon and Fzoul's feuding (which has already seen Fzoul dropped into his own blade barrier) from proving fatal to either of them, and when Fzoul is slain by the protagonists in Crown of Fire, he bullies one of Fzoul's subordinate priests into retrieving his body to have him resurrected.

The excuse for Fzoul's resurrection is also…incredibly flimsy. He claims, to one of Fzoul's subordinates, that he wants Fzoul resurrected because Fzoul is “thrice the administrator you'll ever be”—when despite the casualties the Zhentarim face in this novel, Manshoon has had no one else raised from the dead. Not one other person. Only Fzoul.

While Fzoul is less overt, his behavior during Crown of Fire is no less interesting. Early in the novel, he and Manshoon negotiate separately with their beholder allies for control of a lichnee (a sort of failed lich) with the intention of using it against the protagonist Shandril. It’s clear the beholders intend to play Manshoon and Fzoul against one another in this—the beholder offering Fzoul the second method states that “[his] identity and mind will be shielded from Manshoon” if he uses it, to give Fzoul opportunity for treachery (a note: at no point do either of them use the lichnee against anyone other than Shandril). Later in the book, after Manshoon is temporarily slain by the protagonists, Fzoul implies to the same beholder allies that it was permanent, and that he had a hand in destroying Manshoon's remaining stasis clones. This is a lie. It’s revealed at the end that not only did Manshoon have four remaining, but that they were in Zhentil Keep, and guarded by a human guard in Manshoon's employ. If Fzoul had wanted, it wouldn't have been difficult to track down said guard—yet the clones remained unmolested.

A final point. In the lead-up to Fzoul's confrontation with Shandril, he makes use of a spell engine Manshoon had set up in the Citadel of the Raven as part of a trap. The relevant passage follows:

Then he descended to the forehall of the tower, stood on a paving stone that had been enchanted by Manshoon years ago, and spoke one of the words the mage had taught him. An almost inaudible singing sound answered him as the hidden spell engine Manshoon had prepared spun silently out of another plane and into solid existence in Faerûn. It could appear only in this place, but Fzoul—being the spellfire maid’s target—was just the bait to bring her here to face it.

Fzoul could not see the spell engine, but he knew that it now filled most of the room behind him: a great wheel that would begin to spin if spells struck it, absorbing the magic to power itself. Manshoon’s greatest work. It drank all magic cast at it.

The purpose of a spell engine is to siphon off magical energy in the vicinity, effectively preventing spellcasting. If Manshoon truly distrusted Fzoul, Fzoul wouldn't even have known it existed, in order to give Manshoon an edge in a fight, should it come to it. Not only does Fzoul know it exists, he’s explicitly been taught how to use it, and is using it to set a trap of his own.

If you've read this far (...over 3,000 words), I think I've made my point clear. While the text claims Manshoon and Fzoul distrust and dislike each other, what it demonstrates, time and time again, is that they do trust each other a great deal, and are more than willing to lie to protect each other. The question remains, then: if they actually do care for each other (or are, indeed, romantically entangled), why hide it? Out of universe, the answer is obvious: the Forgotten Realms as a setting debuted in the 80s, and many of the works I've referenced in this essay were published in the 90s. Queer characters were non-existent in that space at that time; indeed, Greenwood himself makes a dig at queer men in Spellfire. Nowadays, of course, this relationship couldn't possibly be canonized—they’re villains, after all. In-universe, Zhentil Keep is markedly more conservative than many of its neighbors (they didn't have a woman on the Council of Lords until the late 1340s or early 1350s DR), and even if that weren't a factor, Manshoon and Fzoul both have a lot of enemies. An open relationship would be a death sentence.

Fortunately for them, they seem to have done well to hide it.

#forgotten realms#forgotten realms meta#manshoon#fzoul chembryl#zhentarim#...this thing is 3.5k long and it is 1:30 in the morning my time as I post this#anyway I'm normal about them. this is normal and I'm fine#in conclusion: there is no heterosexual explanation for any of this

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drow House Glyphs

Art for The Drow of the Underdark

Artist Unknown

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE APPLE AND THE TREE.

My piece for @silkandsulphur !!! A retelling of Brian Valenzuela's Glasya and Asmodeus portrait.

#bg3#bg3 fanart#bg3 raphael#raphael the cambion#baldur's gate 3#baldurs gate 3#dnd mephistopheles#mephistopheles dnd#brian valenzuela#forgotten realms#dungeons and dragons#dnd#nine hells#silk and sulphur#raphael bg3#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

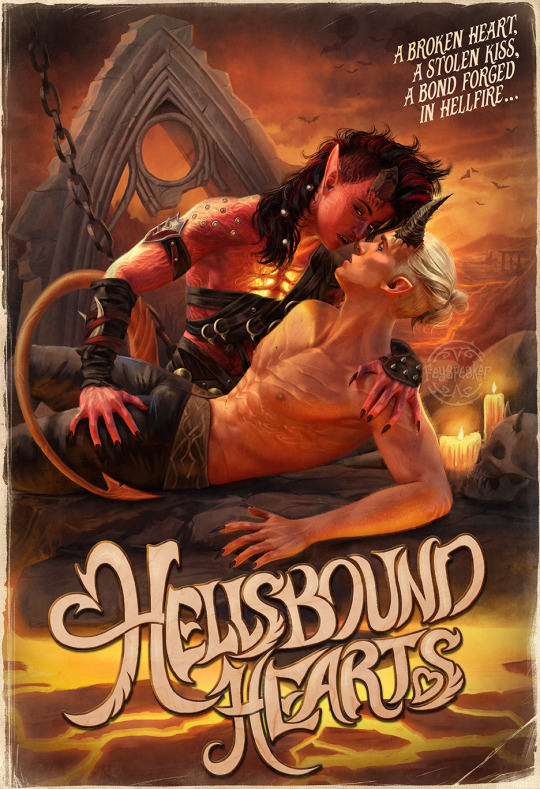

She came to him with a broken heart; little did he know that fixing it would bond theirs both together to the hells and back… oh yes, i did that

prints | patreon (has version without lettering for download)

#karlach#dammon#karlach x dammon#bg3#bg3 fanart#tiefling#baldur's gate#baldurs gate 3#baldur's gate 3#karlach cliffgate#gaming#forgotten realms

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

New outfits for Millifein - one could say Millifits✨

#art tag#oc: millifein#dnd#half drow#moon elf#dungeons and dragons#forgotten realms#ttrpg#drow#bg3#bard#bladesinger#dnd elf#fantasy outfits#bg3 tav#pastels#faeryl

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

My dm gave me a mimic and I said what does it look like and he said uh idk I guess you can decide and this is what happened

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

opening up a few slots for rendered portraits!

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

While reading the third book about Drizzt, I thought that he could have avoided his suffering from the sun by wearing sunglasses. 💅🏻

#drizzt do'urden#forgotten realms#legend of drizzt#drizzt#drow#the forgotten realms#the legend of drizzt

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made an oil painting of my forgotten realms d&d character, Faerelith Obarskyr! She's a Cormyrian princess cursed to be a harengon by Silvanus, and currently trapped in the Tower of Stars

#tower of stars#harengon#dungeons and dragons#dnd oc#dnd art#dnd5e#forgotten realms#cormyr#my art#artists on tumblr#furry#rabbit#knight#oilpaint#oil on canvas#oil painting#traditional media#oc: radish

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Travel with Gale...

To a beach

A Goblin Camp

The Underdark

Moonrise Towers

Shopping

High Hall

To bed

...ready to head back to Waterdeep.

#dekarios family#baldur's gate 3#forgotten realms#gale of waterdeep#gale dekarios#bg3 gale#travelling#bg3 photomode#bg3 photography#gale x tav#gale bg3

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

eilistraeean "We ought to take care and use our words respectfully so that our peers may feel comfortable and safe." vs vhaeraunian "I'm a 🗣❤️STUPID JALUK!!🗣❤️ I LOVE🫶♥️ being a 💕STUPID JALUK!!💕 and all my fellows are STUPID JALUKS!!!🥰🥰"

Hmmm, now I'm curious. How do you think a word like "jaluk" would be handled among those like the worshippers of Vhaeraun? Would they maybe kind of reclaimed it and use it in a more playful, joke-y manner, or would it be a banned word?

Oh I think it's 1000% reclaim.

Nevermind that I don't think you can actually tell most Vhaeraunites what to do. How does the wiki phrase it. ("seemed to have a rather lax attitude towards divine commandments") I'm also under the personal impression they're a group that would take a lot of delight in being a little vulgar at times (I've mentioned this before, but group dynamic wise they seem based off? Anarchist. Punk-esc.) I'm not unaware of the irony of a stealth group being able to be described as "Groups that are loud." but you know. They'd carry themselves in a way that would be a little jarring and off-putting to some people, because the ability to have that self expression is in itself a point of pride.

This feels like it would also be one of those massive cultural differences between Eilistraee and Vhaeraun's church too, especially during the masked lady era. It's the one of those...

Eilistaee worshiper voice: "Okay. We should be careful about some of the language we use. A lot of people coming from Lolth's church need to feel welcomed here. They need to see that life can be more then the suffering and horrors found in those caverns..."

Vhaeraunite worshiper convert, up out of reach: "What's wrong sister, afraid a jaluk will outshine you?" Sticks tongue out as a taunt.

Eilistraee worshiper almost breaks her cup in frustration.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jergal Outfit

3D render for Baldur's Gate 3

Art by Anton Grigoriev and Sergei Gereev

#anton grigoriev#sergei gereev#art#concept art#fantasy#forgotten realms#d&d#baldurs gate#bg3#baldurs gate 3#baldur's gate 3#jergal

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rolls to Alarm Your Players

Want to spice the game up? Why not try alarming your players for no real reason? Make sure to make a show out of counting the dice before you roll.

#dnd#dungeons and dragons#rollingtable#forgotten realms#dungeon master#dm#rpg#ttrpg#d12#rolling rolling table#dice

31K notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you mean that Forgotten Realms is a romantic fantasy setting masquerading as high fantasy?

(With reference to this post there.)

Exactly what it says on the tin – the Forgotten Realms is clearly principally inspired by romantic fantasy, not high fantasy.

In this context, when I say "romantic fantasy", I'm referring to a specific, relatively short-lived genre of fantasy literature that was wildly popular in the 1980s and 1990s, but abruptly fell almost entirely off the map after about 1998, due to a variety of economic and cultural factors which are way too complicated to go into in a Tumblr post. This is distinct from the more contemporary usage of "romance novels with fantasy settings", though there's definitely a lot of overlap.

If you're looking for a romantic fantasy reading list, Mercedes Lackey's Valdemar series – especially the early stuff – is probably the easiest to get your hands on these days; it's practically the only example that still has any real name recognition in 2025, for all that Lackey was a latecomer to the genre. Other names worth checking out include Margaret Ball, Carole Nelson Douglas, Tanya Huff, Holly Lisle, Jennifer Roberson, and Elizabeth Ann Scarborough, off the top of my head, though not all of them worked exclusively within the genre.

(Elizabeth Moon is an interesting edge case, in that her stuff is principally military science fiction, but very much adheres to the forms of romantic fantasy. Her Deed of Paksenarrion trilogy, one of her few pure fantasy works, is a fun snapshot of an era because it was written explicitly in response to what Moon perceived as the shortcomings of the fantasy worldbuilding on display in then-contemporary Dungeons & Dragons settings, and hit the shelves at just about exactly the same time as the earliest Forgotten Realms material.)

#gaming#tabletop roleplaying#tabletop rpgs#dungeons & dragons#d&d#forgotten realms#media#literature#fantasy#romantic fantasy#worldbuilding

3K notes

·

View notes