#Graphite-Daydreams

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i have been told that it is soon (end of next month) the Tenth anniversary of that time that my blorbo and @randomoranges' blorbo became a ship

it occurs to me that while i sometimes remember to gather everything together under the it is the monmonton tag... WHAT is the monmonton exactly? i mean, beyond the simple seed of 'two short pudgy nhl hockey bros' it sprouted from?

this marks the beginning of my journey to understand and perhaps even communicate... what it is and where it's at. you know i don't typically do shipping and whatever but for some reason these blorbs captivate me and i enjoy torturing them with Situations so there's a lot of built up lore over TEN YEARS [scream] so this is a look back at the current "canon" accepted chronology between Windex and I, but like, as bad and hard to understand as possible. You gotta start somewhere I guess.

#it is the monmonton#projectcanada cities#pc: montreal#pc: edmonton#hapo doodles#graphite#traditional art#pc: calgary#edward murphy#étienne maisonneuve#calvin mccall#if there's things we can clarify or answer now's the time to ask#i keep daydreaming about making an infographic about it which is WEIRD for me

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romantic - cw; 141 + alejandro (bc those are all my boys <3) short sappy fluff, marriage mentions. Just me putting some daydream thoughts out to the void <333

Soap is romantic in that he draws you. He has a whole shelf full of old sketchbooks and half of them are filled with you. From mindless, messy doodles to works that took hours. Charcoal and graphite. With his hands he conveys to paper your beauty, and his love is seen in every stroke.

Gaz is romantic in that he always buys you flowers. From single roses to bouquets of carnations, barely three days go by without flowers in your home. Each one seems to speak volumes. He keeps them all, hanging them to dry in the garden shed. He's waiting for one bouquet in particular to join them.

Price is romantic in that he's always ready with a helping hand. You can do things on your own, sure, but he's always letting you know he's there. He always offers. Meals, cooking. cleaning, groceries. he's your shadow - because he cannot have you working yourself too hard.

Alejandro is romantic in that he plays you music. He hadn't touched a guitar in a long time until you moved in together, but he decided to play it once more before it would've gone back to a corner to collect dust. When he saw how your shoulders relaxed, and how you swayed when you recognized the song, that guitar never got dusty again.

And Ghost. The unreadable enigma. Ghost is romantic in that he writes about you. A single notebook stashed away in some dark corner holds his deepest secrets - poems that are all about his love for you. They're sweet, gentle, and they're passionate. Someday he'll read them to you, when he finally write one he thinks is good enough. In reality the first you hear isn't a poem at all. They're vows.

Remember to support your favourite writers! If you liked reading it, reblog it <3

#cod headcanons#john mactavish headcanons#kyle garrick headcanon#john price headcanons#alejandro vargas headcanons#simon riley headcanons#soap x reader#gaz x reader#price x reader#alejandro x reader#ghost x reader

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Angela ¦ "05 ¦ Her ¦ Bi ¦ INFP ¦ Artist ¦ Did I say artist?

ABOUT :

Call me Angel / she-her. this is @angelaness — the essence of me in pixels and words.

Currently 19. Black asf. 180cm tall and very proud of it.

artist, muse, menace.

i draw myself so the world never forgets what it lost when it tried to shrink me. self-portraiture is my love letter to existence. yes I'm obsessed with art like it’s religion.

currently: painting w acrylic, cutting up old jeans, passioning my project (coming soon x) and daydreaming about a future lover I already miss.

.a shrine to girlhood that bites back.

.thoughts too tender for main.

LIKES :

graphite-stained hands. old art masters. kpop, krnb, gl + bl (biased, unashamed). vintage cams + handycam diaries. jazz loops in dim rooms. sims 2 aesthetics, messy art desks, cigarette ash in candle jar. pretty men n women who look like heartbreak. dirt, rex rats, glass hearts, and everything chicly broken. fashion that's slashed + stitched with story. solo dates, long showers, secret blogs. the art kids nobody gets but everybody wants to be. baking. pinterest + spotify combo. stray kids. ive. red velvet. DPR IAN.

DISLIKES :

✧ art theft ✧. nosy people who don’t listen. when people make me explain the magic. over-filtered lives + over-sanitized thoughts. “why don’t you smile more?”/“i don't like what you're wearing”. boys who think height intimidates me; babe, i love towering over you. always. Subconscious bigotry. when 2+ ppl are talking to me/trying to get my attention at the same time irl 💔. bad handwritting. weaponized incompetence.

DNI (DO NOT INTERACT) :

racist, ableist, queerphobic, transphobic, fatphobic, misogynistic, islamaphobic etc (obviously). if you mock kids, art, or dreams. fetishizers (i see you. i block you.). anti-oc / anti-self ship / anti-whimsy. cops + copycats. no age-inappropriate behavior. keep it classy or keep it gone.

BOUNDARIES :

i am not your therapist, your savior, or your fetish. you can trauma dump but plz provide/tell me b4 hand a warning for graphic details. don’t repost or edit my art. ask before using, actually don't use my art for ANYTHING. respect my silence. you can flirt, but know your place. don't be a dumb keyboard warrior spreading hate on my blog, you're just a fictional thing in my phone and i bite back. not gently. usually.

if you stay, stay sweet.

stay strange. stay whimsy.

stay #angelaness.

if you vibed, reblog. if you didnt, scroll. (leave a like blessing tho)

#angelaness#intro post#pinned post#pinned intro#black girls of tumblr#wonyoungism#pinned info#girlblogging#this is a girlblog#motivation#girlblog aesthetic#glow up#that girl#it girl#diary entry#dividers by dollywons

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

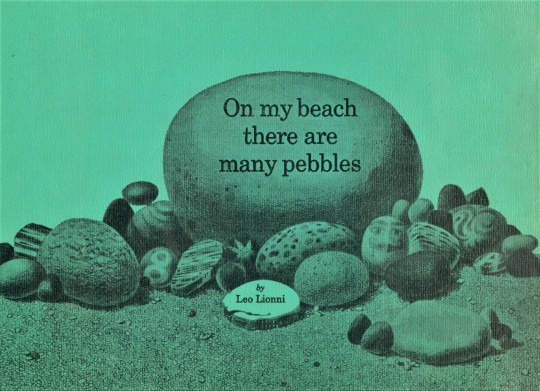

Staff Pick of the Week

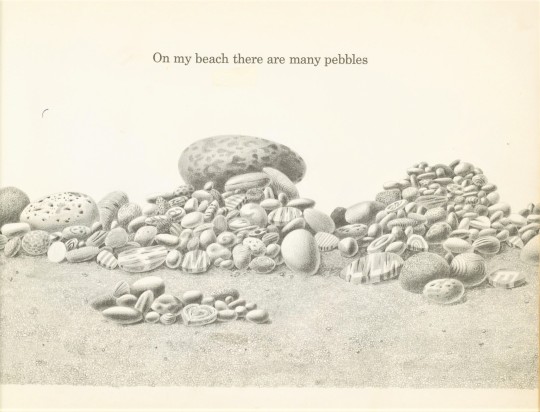

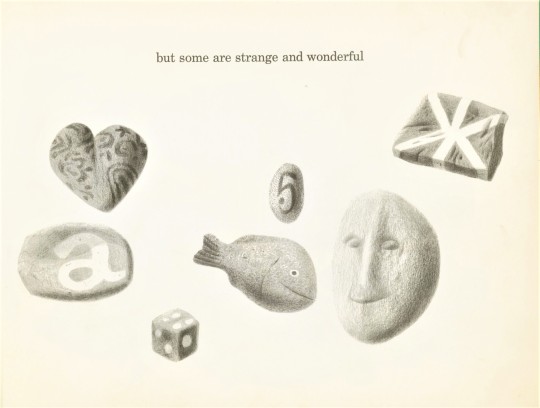

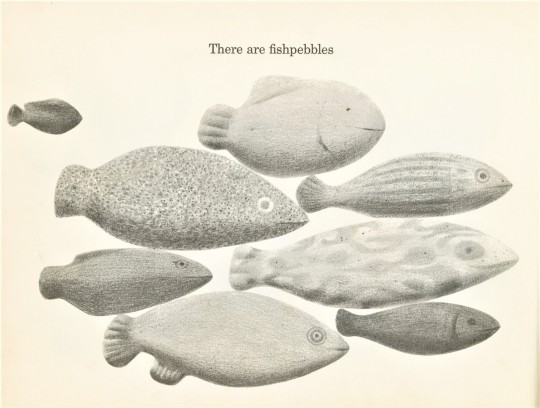

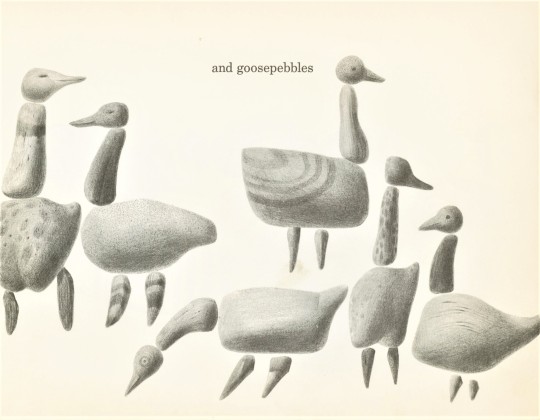

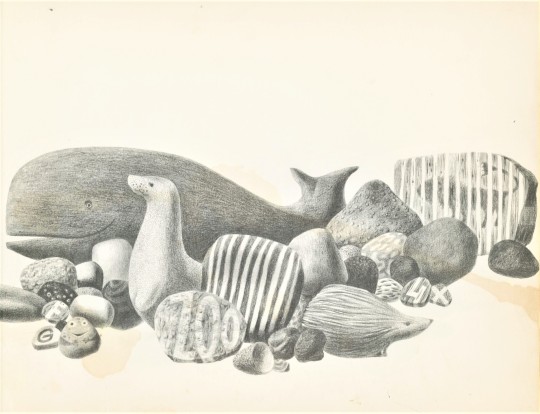

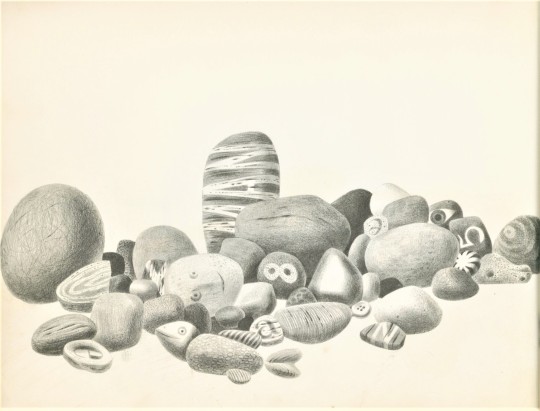

My first Staff Pick of the Week is Leo Lionni’s whimsical children’s book On My Beach There Are Many Pebbles published in 1961 by Ivan Obolensky, Inc. In this book, Lionni (1910-1999) takes readers on a walk by an imaginative shoreline where he encounters a wide variety of anthropomorphized pebbles including fishpebbles, goosepebbles, and peoplepebbles to name a few. With brief text, readers are left to daydream over his intricate graphite illustrations of beach treasures.

Lionni was an Italian American who was well known for his accomplishments in painting and advertising designs. While living in Philadelphia in the 1940s he worked on advertising campaigns for Ford Motors and Chrysler Plymouth before accepting the arts director position at Fortune magazine.

Later in life, Lionni moved back to Italy and began his career as a children’s book author and illustrator. He produced over forty children’s books and received numerous awards for his efforts, including the Caldecott Medal on several separate occasions. He is also credited with being the first children’s book author/illustrator to use collage as the main medium for his illustrations. While On My Beach There Are Many Pebbles does not feature collage, one can certainly experience Lionni’s playful use of shapes and composition and appreciate his passion for simple storytelling.

View more children's books from our Historical Curriculum Collection.

View more Staff Picks.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#staff pick of the week#leo lionni#on my beach there are many pebbles#Ivan Obolensky#Inc.#pebbles#illustration#children's books#illustrated books#Historical Curriculum Collection

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

More queer fangrrrl daydreaming with my two favorite space lesbians 🧡🤍💖😶🌫️

@wolfwrenweek

Graphite drawing on paper

#star wars#ahsoka#wolfwren#shinbine#shin hottie#shin x sabine#sabine x shin#queer artist#queer artwork#queer representation#natasha liu bordizzo#ivanna sakhno#space lesbians#sabine wren#shin hati#sapphic#i ship them#i ship these two so much#graphite drawing#drawing#wolfwrenweek#wolfwrenweek2023

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 to 7—choose your fighter!💪☺ Are you Team Bee, Butterfly, Bird, Bat… or maybe Dragon?! 🐝🦋🐦🦇🐉 Whether you're into magical creatures, winged wonders, or just things that defy gravity, these whimsical sketches might just flutter their way into your heart.💛🥰 Swipe through and tell me your favorite! These pencil babies are now flying solo on my website—ready to bring some magic to your walls → www.camilladerrico.com (link in bio!)🤗✍🖤

•

P.S. Warning: staring too long may cause sudden daydreaming or art collecting. You’ve been warned.😉😅

•

•

•

•

•

#camilladerrico #PopSurrealism #drawing #SketchbookMagic #ButterflyArt #BeeLover #BirdNerd #FantasyArt #CuteAndCreepy #flightsoffancy #bats #graphite #pencils #sketch

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

day one: devouring heavenly bodies ART: graphite drawing on paper by queer-fangrrrl-daydreaming ☆ obsession by shipping1addict ☆ devouring heavenly bodies by thedivergentbatch ☆ with teeth by cmbdragon98 ☆ excuse for physical contact by im-yotsu ☆ Possessive Love by ali-mart ☆ Bandit Shin by rainestorm-days ☆ sick and tired by rubidimum ☆ they did not let it linger by kokonut713 ☆ devouring heavenly bodies by grimdarkqueen ☆ bites bites bites by somewillwin ☆ 🤍💜 by karasyelena ☆ sketches by rainestorm-days ☆ the wolf and her moon by endoplight ☆ scars and bites by luciouz ☆ Devouring Heavenly Bodies by light-fawn ☆ blood by natchosfarfaraway

WRITING: i am all alone and my only judge is me by nightincarnate ☆ biting + blood by oftenlyshitposting ☆ New haircut? by rainestorm-days ☆ Sugar, We’re Going Down Swinging by tamoline ☆ her mausoleum by shinhatisgirlfriend ☆ devouring heavenly bodies by how-do-i-do-words ☆ Miód Malina by mandalorianfleshenjoyer ☆ Chapter 1: The Hunt by asianscaper ☆ you were the one (I’d have starved with) by schlo-300 ☆ A Biting afFair by veditas ☆ moon-drunk monster by the-lovely-lady-luck ☆ Scars by MJTatch ☆ tongues and teeth by tonsillessscum ☆ It's a Long Way to Peridea by melanie-ohara ☆ Artemis’s Possession by kalevalakryze

EDITS/MUSIC: wolfwren playlist by shipping1addict ☆ Wolf Cento by kalevalakryze ☆ shin hati by triangulore ☆ possessive love by erisyuu ☆ hungry eyes by ssapphos ☆ wish by twocrowssinatrenchcoat ☆ the wren by bailey41 ☆ raw with love by armoralor ☆ Where it Begins by tonsillessscum

Thank you to all the amazing creators that participated in #wolfwrenweek2023! 🗡️❤️ to see a full list of all submissions in one place, we've also created a spreadsheet with of participants [here]. Our blog also has a tab that lists all creations [here]! Special thank you to the amazing event mods that helped make this event week possible: @sapphicsparkles, @coldcutfruit, and @armoralor ❤️

#wolfwren#sabine wren#shin hati#ahsoka#star wars#sapphic star wars#star wars wlw#shinbine#sabine x shin#sabine wren x shin hati#wolfwrenweek2023#wolfwrenweek#shin hati x sabine wren#admin post

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macworld December 2001

A major upgrade to Mac OS X bumped up its performance, and this issue insisted Apple's new operating system was now more than something to test every once in a while. I did daydream about putting a bigger hard drive in my G3 All-In-One to make the upgrade leap (which would have involved connecting the old hard drive to where the CD drive hooked up to transfer files off it); when I was informed I'd been hired for a steady job not that long afterwards, though, I went ahead and bought a new graphite iMac (reviewed inside this month). For the first little while I did still boot back into OS 9 to run a Usenet newsreader, but after a while I didn't do that any more (and not just because I'd finally stopped reading Usenet).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“NEANDERTHALS WERE HIGH TECH AND LIKED THEIR FINERY. Recent discoveries have dramatically narrowed the formerly-perceived chasm in technological abilities and cultural accomplishments between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. For instance, Neanderthals used complex techniques to manufacture strong hafting glues from birch tar (Mazza et al. 2006). They made three-ply cord (Hardy et al. 2020). They probably used chemical accelerants to help start fires (Heyes et al. 2016). They burned coal (Dibble et al. 2009). Neanderthals had medicines that likely included naturally occurring aspirin and penicillin substances (Weyrich et al. 2017). Whether for fashion, camouflage or other reasons, they used at least seven different minerals (graphite, buserite (MnO2), hematite, goethite, limestone, chalk and pyrite for the black, red, yellow, white, and sparkling gold colors (Sykes, 2020). They also used charcoal and feathers (preferring black colors). Toolmarked and polished eagle claws found in Croatia that date to 130,000 years are the oldest evidence of jewelry in Europe (Radovcic et al. (2015). Neanderthals also wore seashells stained with hematite (Srsen et al. 2015). They made complex cave art and may have made flutes. They had burials and ceremonial sites (it's hard to explain the 174K-year-old Bruniquel site any other way). It's ever-clearer that the "chasm" has narrowed to perhaps a small stepover.”

- Neil Bockoven

A collage of Neandertal faces as imagined by artists and exhibited in museums during the genome era. Artists include Alfons and Adrie Kennis, John Gurche, Elisabeth Daynès, Tom Björklund, Oscar Nilsson, and Fabio Fogliazza.

Artwork and words by Tom Björklund

The Löwenmensch figurine – a toy or a religious treasure

Yet another version of the image, slightly different from the ones I posted on Twitter and Instagram. Inspired by the around 40k years old iconic Löwenmensch sculpture of the Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany.

Too often the role children had in ancient societies has been unnecessarily neglected, according to a growing number of researchers. As a result many objects that could very well have been made for children, and even by children, have been interpreted to be religious objects, created to be worshipped in order to gain good luck and prosperity. Both alternatives are plausible – it can be hard to tell the diferrence. In a way it's perhaps possible that they sometimes were both.

In ancient, and not necessarily that ancient, cultures, things were not just things, they had a meaning and a function beyond their physical appearance and form. Perhaps children's toys were not just for fun but they were also portals to an unvisible world, allowing a contact with the ancestors or mythical creatures that could offer protection and guidance.

And even today, a daydreaming child acquires the unnatural powers of the precious superhero collectible, offering a moment of relief from the challenging reality.

If you wish, you can also follow me on Twitter and Instagram, for different versions of the images, news and background stories.

https://www.instagram.com/tombjorklundart/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stars are meant to burn

Chapter 3: Fractious

fractious

[ frak-shuhs ]

adjective

refractory or unruly: a fractious animal that would not submit to the harness. Synonyms: difficult, stubborn

1993 – University of Bologna

The lecture was supposed to be about inclusive education. Instead, it was half a joke.

Professor Rinaldi stood at the chalkboard, dry-voiced and impatient, gesturing vaguely at a handout that looked like it had been mimeographed in the 70s. “So — there is what we now call 'minimal brain dysfunction,' sometimes referred to as attention deficit disorder, with or without hyperactivity. These children often exhibit difficulty concentrating, are impulsive, and struggle to follow directions. It’s very common in boys.”

Záfiro’s spine tightened, but she kept writing. It was automatic. Her hands moved; her ears shut down.

Another student asked, “And autism? Is it the same?”

Rinaldi sighed. “No. Autism is a more severe disorder. Poor eye contact, repetitive behaviors, significant language delay. Most autistics are nonverbal, and most require lifelong care. We don’t typically see them in normal classrooms. That’s a very different condition.”

Then came the one that always made her freeze.

“And Asperger’s?”

Rinaldi nodded. “Yes — more recently described by Dr. Hans Asperger. High functioning, but socially awkward. Obsessive interests. These children may seem intelligent, even precocious. But they’re often isolated, difficult to teach. They struggle with empathy and adapting to classroom norms.”

Záfiro looked down at her paper.

The chalk scraped.

“You won’t likely encounter many such children,” Rinaldi added. “They don’t typically go far in traditional education.”

A few students chuckled.

And all Záfiro could think was:

What if they knew who I really am?

What if they could see inside her head — the knots, the broken circuits, the whole unstable network she walked around carrying like a glass plate she couldn’t drop?

She looked normal. That was the trick.

That had always been the trick.

Mexico, 1984 – Age Eleven

She’d been brought in for being "unruly."

That was the word her teacher used. Unruly, distractible, impulsive, lazy. Her mother cried in the waiting room. Her father crossed his arms, scowling at the floor.

The doctor wore a white coat that smelled like bleach. He gave her puzzles. Asked her to repeat number sequences backwards. Then forwards. Then faster.

“Do you always interrupt others when they speak?”

She looked at her mother, confused.

“Do you often lose your things? Forget your instructions?”

She nodded, ashamed.

“Do you daydream during class?”

She didn’t say anything. What was she supposed to say? That daydreaming was the only thing that made class bearable? That her mind chewed through the silence like it had teeth?

She was eleven years old, with skinned knees and graphite under her fingernails. She sat in the corner chair and heard the word for the first time:

“Deficit.”

Specifically: “Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad.”

The phrase sounded like a punishment. Like something she had done wrong.

Later they would call it ADHD.

Back then, it was barely understood.

Especially not in girls.

The school agreed to let her stay — with conditions. Her parents were told she needed “discipline.”

Her mother bought a plastic timer.

Her father took away her books.

They all tried to make her someone else.

1993 – Bologna

Back in the classroom, the lecture droned on, but Záfiro was far away. She stared at the margin of her notebook where she had drawn rows of tiny birds without realizing it.

She still did that — doodled, scribbled, rocked her foot under the desk. She still mixed up left and right when she was nervous. She still needed to rehearse simple things in her head three times before saying them aloud. And when the professor said, “struggles with empathy,” she flinched. No, she thought. I feel too much. That’s the problem.

Maybe she wasn’t autistic.

But maybe she wasn’t not.

She hadn’t been assessed for anything since that first time. Back in Mexico, a girl like her was lucky to even get diagnosed at all.

Her grades were fine. Her work was good. Nobody noticed.

They just saw the bombshell with the accent and the bright ideas. The fast-talking, over-prepared one. The one who never slept.

They didn’t know what it cost her.

They didn’t see her zoning out mid-sentence.

They didn’t see her chewing the skin off her fingers after class.

Záfiro wrote in the margin, looping the letters over and over:

“Not broken. Not broken. Not broken.”

She pressed her forehead to the bus window, the cool glass grounding her. The streets of the city passed by in soft motion — narrow alleys, laundry lines, ochre stone, mopeds weaving like mosquitoes. She could still feel the chalk dust from class on her fingertips. She liked that. Proof that she’d been there.

It hadn’t always been so easy to sit in a classroom.

“Your daughter may never speak,” the doctor had said once. She was two and a half years old, purple and bird-boned, born too early and against the odds. She didn’t cry like the others. She didn’t babble. She just watched.

Her mother refused the word retarded — even when other women whispered it behind her back at church, even when the pediatrician insisted on “realistic expectations.” Her mother took her home. Started her own damn curriculum.

Záfiro remembers picture books. Word cards. Shadows of words taped to the fridge. Her first sentence — not at two, not at three, but nearly four years old — had been:

“No quiero dormir.”

Her mother wept with joy, not frustration.

And then reading — they said it wouldn’t happen. That her brain just didn’t “process language properly.” That she wouldn’t catch up. That reading comprehension would be beyond her.

But her mother brought her books from tianguis markets and taught her to break them apart. Picture. Phrase. Pattern. Prediction.

By the time she was eight, she had a dictionary beside her bed and a Bible with underlined verbs. And when her cousins said she was strange, she didn’t flinch. She knew she was. But strange was not the same as broken.

The bus stopped.

She pulled her scarf tighter. Kept walking.

UNAM had been the first real test. Third place on the national entrance exam. They'd told her not to get her hopes up — “the homeschool girl? The one with the funny voice and nervous hands?” But she’d made it. All of it. And when she opened her acceptance letter, she ran straight to her mother’s room, yelling.

People still muttered.

They said her mother had ruined her. That she was too sensitive. That she was strange, unstable, that she could never handle real school, real work, real people.

Even after she'd gotten her degree, even after the papers and awards and fieldwork — they still couldn’t see her. As if their voices were more real than her proof.

When she flew to the U.S. for her Bologna exams, she heard it in the airport.

“Cleaning crew’s that way, honey.”

“Did you get lost, sweetheart?”

Someone even called her a beaner to her face. Another person asked if she’d been trafficked. Like she didn’t belong in a waiting room full of European hopefuls with expensive luggage and expensive voices.

But she passed.

And now she was here.

She looked at her own reflection in the glass of the faculty building’s doors. Curly hair pulled into a bun, a cardigan too big on her, bag heavy with folders, her mother’s silver cross around her neck. She looked — to the average eye — like any other Latin girl abroad. Unremarkable.

But she knew what this body had survived.

The intubators. The misdiagnoses. The hours of speech therapy. The tears over textbooks. The violence of being almost seen. The ache of knowing she had to prove herself twice just to stand where others arrived by default.

She was the kind of girl people underestimated. The kind they laughed at, or forgot.

And still.

She stepped through the door.

Záfiro Santiago had made it to Bologna.

Not because they let her.

But because she took the walls they tried to build around her

—and studied until she could walk right through them.

She didn’t know how to stop. Not really.

Záfiro Santiago — no. Alma Záfiro Xochiquetzal Castillo del Campo — always the full name, always the “del Campo” too. Because it was her mother’s. Because she owed her everything. Her voice. Her books. Her hunger.

If her mother hadn’t stayed — hadn’t read and wept and taught and fought — Záfiro would have never made it past six, much less twenty-three. Her mother had gone to war for her, in skirts and sandals.

Záfiro walked fast, heels clicking. Her notepad was already half full.

She didn’t pace herself. She had no pace. Just ignition and flame.

Arturo walked beside her, cool and clean as ever, wool coat sharp at the shoulders. When they reached the modest apartment, it was Arturo who knocked, but it was Záfiro the girl’s mother noticed first.

"You’re the assistant?” the woman asked, giving her a once-over. Her voice curled slightly — Irish, half-buried under years of Italian.

“She looks so young.”

Arturo answered smoothly, “She has a degree in education, graduated at twenty-one. She’s continuing her studies here — cognitive development.”

Záfiro added, a bit brightly, “UNAM, originally. First in my family. I started at seventeen.”

The woman blinked. “Oh. Good for you.”

Záfiro only smiled.

Inside, the flat smelled of bread and polish. On the couch sat the girl: Argelia. Around twelve. Dark curls and freckled skin, eyes that didn’t bother hiding their boredom. She was slumped like she wanted to be anywhere else.

Záfiro sat beside her. “May I ask you a few questions?”

Argelia didn’t answer.

Záfiro tried again. “What’s your diagnosis?”

Argelia snapped her eyes toward her. “What’s yours?”

A pause.

Záfiro raised an eyebrow, unfazed. “ADHD and anxiety. Are you on meds?”

Argelia tilted her head, watching her with sudden curiosity. “Wait. Are you retarded?”

Záfiro didn’t even blink. “No. I have ADHD and anxiety.”

“…Then how do you go to school?”

Záfiro folded her hands neatly over her notebook. “With my feet. Or by bus, if I have coins.”

Argelia snorted.

“Are you not stupid?” she asked, testing, cruel in the way only brilliant kids with bruises could be.

Záfiro smiled — not kindly, but not unkindly either.

“All adults are.”

Argelia stared. Her mouth twitched. “How do you do at school?”

“I’m the best in my class,” Záfiro said, plain as prayer.

“Me too,” the girl muttered, then louder: “I get bored a lot. People are boring. Teachers are boring. I don’t like people touching my stuff.”

Záfiro nodded. “I used to line up my pencils by color. My cousin once messed them up. I cried for an hour.”

Argelia looked at her again — really looked, for the first time.

From the hallway, Arturo’s voice: “Signora O’Brien, may I ask about her birth history?”

Záfiro turned. She hadn’t noticed he was listening.

When their eyes met, Arturo looked almost amused. No mockery — just the flicker of recognition. Of two halves snapping into symmetry.

Záfiro looked back at Argelia. “Do you want to keep talking?”

“Maybe.”

“Would it help if I wasn’t wearing a skirt suit?”

“…Probably.”

“I have jeans,” Záfiro said solemnly. “And a sweater with a hole in the sleeve.”

The girl cracked a grin.

Záfiro didn’t write anything else down. She just nodded and tucked the pen away.

She could see it already: the pattern.

Girls like this. Like her. Prickly, fast, furious. Called difficult. Called rude. Called wrong.

But there was nothing wrong with this girl.

Not that anyone would believe it. Not unless someone like Záfiro showed up and stayed.

Argelia was slumped back on the couch, arms crossed, hair frizzed at the ends like she’d tugged at it too much. Her foot tapped restlessly. Then, suddenly, she blurted:

“I can’t do anything. I’m too stupid.”

Záfiro didn’t flinch. But her tone sharpened.

“Don’t say that.”

“Why not?” Argelia shot back. “Because it’s a bad word? Adults say it all the time.”

Záfiro leaned in a little. “Do you call your friends stupid?”

“No. That’s different.”

“Would you call Gloria Gaynor stupid?”

Argelia’s eyes darted to the poster on her wall — the one with Gloria standing in sequins and power.

“Of course not,” she said, almost offended.

“Why not?”

“Because she’s… she’s my idol. She survived everything. She sings like she means it.”

“And your friends?” Záfiro asked softly.

“They’re my friends. I mean—sometimes. When they’re not being fake.”

Záfiro nodded. She could feel the weight in the girl’s voice. “People leave,” she said quietly.

“I know,” Argelia muttered, staring at her knees.

There was a long pause.

Then Záfiro said, more gently now, “You’re the only person who’s going to be with you your entire life. You have to learn how to be your own friend. Your own idol.”

Argelia didn’t answer right away. But her tapping foot slowed. Her arms unfolded just a little.

Záfiro gave her a tiny smile. “It’s hard. I’m still figuring it out. But the way you talk to yourself matters. That voice in your head? That’s the one you hear the most. Make it kinder.”

“…Even if I mess up a lot?”

“Especially then.”

A silence. Argelia looked back at her poster. “She did mess up a lot.”

“And she still stood up and sang,” Záfiro said. “So will you.”

They’re walking back through campus. The late afternoon light stretches long on the stone paths, soft gold against ivy and old walls. Arturo walks quietly beside her, hands in the pockets of his coat. Then, gently, he says:

“Záfiro…”

She looks up.

“I wanted to ask you something,” he says, tone still measured, but different — more careful, more personal. “About your diagnosis. ADHD, you said?”

She slows her pace. Her chest tightens — not from shame, but from the sudden shift in atmosphere.

“Yes,” she says, guarded. “Since I was very young.”

Arturo nods, but doesn’t break eye contact. “I’m not asking out of curiosity. I’ve been thinking. About the project. The patterns we’re seeing in children like Argelia, and in adults who made it past the noise, like you. I’d like to interview you. Formally.”

Záfiro stops walking. “You want me to be a participant?”

“Off the record, if you prefer,” he adds quickly. “But yes. You’re deeply informed, self-aware, and honest. That’s rare.”

She frowns slightly, considering. “Isn’t that a little unethical? You’re my supervisor.”

He raises a brow. “Only if I abuse the information. Which I won’t.”

Záfiro narrows her eyes. “You sure about that?”

“I think,” he says slowly, “you could help more people than you think. But it’s your decision.”

She sighs. “I’ll do it. But I want veto power over what’s published.”

“Agreed.”

They keep walking. For a moment, it’s quiet. Then Arturo speaks again, voice lower:

“I’ve been stuck, lately. With the framework. With meaning. Too many variables.”

Záfiro glances at him, then smirks. “That’s not what the doctors said.”

He pauses, confused. “What?”

She stops in front of him, turning fully. “Doctors also said I’d never speak in public. And now I never shut up. My mom felt scammed.”

Arturo laughs softly — not mocking, just surprised by her energy. “Why did you do it?” he asks. “Why did you keep pushing?”

She lifts her chin. “Other people’s lies are not my truth.”

His gaze lingers on her. Intently. “Did they ever close doors to you?”

“Of course they did.”

“And what did you do in response?”

She doesn’t even blink. “I came through the window. I blew a hole in the wall. I kicked them open.”

A pause. Then she adds, voice fierce and low:

“Everything is possible. I did everything — but let myself be satisfied. I was never going to bother with scraps or crumbles.”

Arturo is still. Like she knocked the breath out of him.

He nods, eventually — once, like he’s memorizing her.

“I believe you.”

The recorder clicks on with a soft hum. They’re alone in the office. The lamp casts a warm light over Arturo’s notes, and Záfiro sits across from him — not as an assistant this time, but as a subject.

Arturo adjusts his glasses. “We’ll begin with context. For the purposes of this interview, can you tell me briefly about your upbringing?”

She leans back slightly, then speaks with clarity — voice measured, not defensive.

“My father was the pastor of our congregation. A small evangelical church in Mexico. Because of that, all eyes were on me. At all times. I wasn’t just a child. I was expected to be the standard.”

“Were you committed to the role?”

“Yes,” she says. “I had a Bible on my nightstand. By the time I was ten, I had read it cover to cover.”

Arturo nods. He keeps his tone neutral. “Did your faith community make space for your neurodivergence?”

Her gaze hardens slightly. “No.”

“But do you still consider yourself a believer?”

“Yes.”

“Despite,” he hesitates only slightly, “your diagnosis?”

“Yes.” Her voice is firmer now. “Absolutely.”

He pauses. “May I ask how you reconcile the two?”

Záfiro doesn’t flinch. “I don’t need to reconcile them. The problem isn’t my condition. It’s ignorance.”

Arturo’s pencil hovers. “Can you elaborate?”

She breathes in. “There’s a passage. John, chapter 9. Jesus heals a man who was blind from birth. His disciples ask, ‘Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?’ And Jesus answers, ‘Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but this happened so that the works of God might be displayed in him.’”

She meets Arturo’s eyes directly.

“So no,” she says. “I don’t see my neurodivergence as a curse. I believe it was given to me for the glory of God.”

There’s a silence between them. A heavy, reverent kind.

“You believe,” he says slowly, “that your condition is not just incidental, but… intentional.”

“Yes,” she replies. “I am who the Lord says I am.”

Arturo looks down, taking notes. But something about the way his brow knits says he’s processing more than data.

“And how do you reconcile that,” he asks, “with the treatment you described? The exclusion from the congregation?”

Záfiro’s mouth presses into a thin line, but her eyes burn brighter.

“There’s another passage,” she says. “Matthew 20. Two blind men are sitting by the roadside when they hear Jesus is passing by. They start shouting, ‘Lord, Son of David, have mercy on us!’ The crowd tells them to be quiet. But they shout louder. Jesus stops, calls to them, and heals them.”

“And in Luke 18,” she adds, “a similar moment. A blind beggar calls to Jesus, and everyone tries to shut him up. He keeps going. Jesus hears him.”

She leans forward now, elbows on the table.

“The crowd is not the voice of God,” she says. “Just because they walk near Him doesn’t mean they know Him, even Judas Iscariot once was Jesus’ disciple, student and close friend.”

Arturo’s voice is soft. “You relate to them.”

“I am them,” she says. “They were told to stay silent. I was told to sit still, to try harder, to stop being a burden. I didn’t listen.”

She gives a little shrug, almost defiant. “I kept shouting.”

Arturo doesn’t speak right away. His pencil is still. The recorder hums quietly between them.

“…Thank you,” he says eventually. “For your honesty.”

Záfiro gives a faint, lopsided smile. “You asked.”

Arturo flips the page in his notebook.

“Let’s talk about your own education. You’ve mentioned having academic difficulties growing up, yet your trajectory is—well. You’re sitting in front of me.”

Záfiro chuckles quietly. “That’s one way to put it.”

“Tell me,” he prompts gently, “what were you like in school?”

She exhales slowly, eyes tracing the window behind him, as if watching a memory form.

“I was the kind of kid who got everything right and still got sent outside. I could recite three poems and forget my backpack. I was constantly... too much and not enough.”

She pauses, then smirks.

“There was this one time, in fourth grade, I got put in charge of organizing the school’s Independence Day play. I had everyone’s lines memorized, color-coded scripts, full schedules. Teachers thought I was some mini-prodigy. But I also forgot to bring the costumes.”

She laughs at herself now, but there’s an edge beneath the joke. Arturo picks up on it.

“I made a huge spreadsheet for the props,” she adds. “But I couldn’t for the life of me remember which bag I’d put them in. My teacher said I had a ‘beautiful mind trapped in a messy room.’”

Arturo smiles. “Was that when they diagnosed you?”

She nods. “They started with ADHD when I was nine. Later came the dyslexia. But back then they just said I had a ‘scattered temperament.’ I was reading Don Quixote and misspelling my name.”

He watches her hand absentmindedly curl a corner of the folder in front of her — left hand.

“You write with both hands?”

Záfiro blinks. “Sometimes.”

“You’re ambidextrous.”

She snorts. “Against my will.”

“How so?”

She stretches her fingers. “I used to write with my left. But my teacher—one of those old-school types—thought it looked ‘uncivilized.’ She tied my left wrist to the chair until I learned to use my right. So now I do both.”

Arturo’s eyebrows lift. “Which hand do you consider dominant now?”

Záfiro doesn’t hesitate. “Left. Always was.”

He nods, quiet amusement in his tone. “Makes sense.”

She glances up.

He gestures with his pen. “That hand’s always smudged with ink.”

Záfiro looks down — sure enough, a gentle crescent of black on the side of her palm. She huffs, more fondly than embarrassed.

“I guess I smear through the world,” she says. “Even when I try not to.”

Arturo’s gaze lingers a moment too long.

“You don’t need to try not to,” he says, quietly.

She shifts, caught slightly off guard.

Then — before it gets too personal — she flips a page in her notes. “So. Are we interviewing the next subject tomorrow morning or afternoon?”

The office was thick with late-night silence, lit only by the amber glow of a desk lamp. Záfiro’s handwriting danced erratically across the page—brilliant, but breathless. Arturo noticed. He always noticed.

“You’re doing it again,” he said quietly, circling behind her. She paused, pen mid-stroke. “What?” “You’re rushing ahead. You’re trying to outpace your own mind.” He leaned forward, voice even. “Slow down. I want all of you here with me.”

She blinked, obedient without meaning to be.

“That’s better,” he said softly. “Now—let me take care of this part. You just watch.”

He took the pen from her fingers, brushing her hand in the process. She inhaled sharply but didn’t move. He wrote something on the edge of her page—tidy, deliberate. Then returned the pen.

“There. Now do it again. Slower this time.”

Záfiro’s lips parted. She looked down, then back up at him, as if seeking confirmation that she was allowed to take her time.

“You’re doing so well for me,” he added. “Exactly what I wanted.”

She swallowed. “I—I don’t know how you always know what I need.”

“Because I pay attention.” He circled to her side, and his voice dropped just slightly. “You don’t have to be perfect. Just be mine for this project. Let me lead. I won’t let you fall behind.”

Her eyes darted to the papers, then to him, then away again.

“Look at me when you answer.”

She obeyed, startled.

“Good girl,” he said. And this time, there was no undoing it.

Silence cracked between them.

She flushed, but didn’t look away.

“You think I’m not aware of how hard you try?” he continued. “Of course I see it. That’s why I push you.” “But I’m tired,” she admitted. “I know. So let me guide you through the rest. You don’t have to think—just do what I tell you.”

Záfiro pressed her knees together beneath the desk, hiding the way her legs trembled.

“Why do you care?” she asked quietly. Arturo looked at her—genuinely looked. “Because I know how it feels to be the smartest one in the room and still feel completely lost. You deserve more than that.” He reached for a dried mango slice from his drawer and offered it. “Eat.”

She took it. Obedient again. Hating how much she liked it.

“Breathe,” he said, watching her chew. “I’ve got you.”

She types in bursts — staccato lines, interrupted by sighs, frowns, whispers of "No, that’s not right." Arturo pretends to stay absorbed in his notes, but he’s watching her in the reflective glass of the cabinet.

Her hair is falling into her eyes again.

He leans forward — not enough to cross a line, but enough for her to feel him.

She doesn’t look up, but she still stills.

A pause.

Then his hand, flat and quiet, slides a few centimeters closer. Not touching hers. Just enough for her pinky to feel the hum of heat nearby.

“Here,” he murmurs. “You skipped a line of logic. May I?”

He doesn’t wait. Leans in — chest close to her shoulder, his breath warming the edge of her cheek. His hand ghosts above hers, not touching the keyboard, only hovering, like a conductor above a symphony.

She nods once, barely.

“Better,” he whispers. “You always land the thought. But you don’t trust the flight.”

The young studen nods and goes for a book, but Arturo’s bookshelf is far too high for her.

She’s on her toes, fingers skimming the spine of La coscienza di Zeno, just out of reach. Arturo is beside her before she can exhale.

“Allow me,” he says lowly.

His arm comes up behind her, his chest nearly brushing her shoulder. She doesn’t dare move. The book comes down — and he doesn’t pass it to her. He holds it for a second. Looking at the cover. Looking at her.

“You’ll like this one,” he says. “He overthinks so much he forgets he has a body.”

They sit side by side now. It’s not even strange anymore. A shared desk, two minds, two laptops. But his chair creaks closer every time.

She’s rereading a sentence aloud — she does this when she doesn’t trust herself — and Arturo, without thinking, places a hand near her wrist.

Not on. Near.

“Try again,” he says. “This time, trust that you’re right.”

She breathes out — steady now.

Then types.

And doesn’t say a word about how she never noticed she wasn’t cold until just now.

Záfiro clutched Marceline’s forgotten bag to her chest like a shield as she climbed the last steps toward the thudding bass. The party pulsed through the walls — not music so much as vibration. The door was half open. Warm light spilled out.

Inside, someone was trying too hard to look like they hadn’t tried at all. Boys in oversized jackets smoking indoors. Girls whose eyeliner shimmered like oil slicks. Everything was oversaturated — the light, the perfume, the sheer volume of existence.

Marceline spotted her and beamed from the kitchen doorway, a bottle of something too sweet in her hand. "Záfiro! You angel—my bag!"

“I didn’t want you to lose your notebook,” Záfiro said, voice small under the music.

Marceline, flushed and joyful, leaned in for a cheek kiss. “Stay a bit. Come on. You look stunning—don’t tell me you’re just dropping it off?”

Záfiro hesitated. She hadn’t intended to stay. Her sweater smelled like laundry and chalk dust, not like the sharp florals bleeding through the apartment. But it felt cruel to turn around now.

“…Maybe ten minutes.”

Ten minutes in, her skin itched from the smoke. The kitchen was too loud, the hallway too narrow. She kept having to step aside for couples mid-flirtation, laughter bursting from mouths like corks off bottles.

Someone handed her a drink she didn’t want. She took it politely. Sipped it once. Too sugary. Her tongue felt coated.

She leaned against a wall near the balcony door, where the air was thin and a bit more real.

That’s when he approached.

Tall. Clean-shaven. Handsome in a textbook way. A tan coat, a tight jaw. The kind of man that carried his teeth like a threat when he smiled.

“You don’t look like you’re having fun,” he said.

Záfiro looked up from her untouched drink. “Is that your opening line?”

“I’m just saying, you’re too pretty to look so serious.”

A pause. She blinked slowly. “That’s a recycled compliment.”

He chuckled. “I’m trying to be nice.”

“It’s not working.”

He tilted his head. “So, what’s your story then? Let me guess. You’re one of those girls who reads Anna Karenina and thinks she’s better than everyone.”

“No,” she said. “I read Anna Karenina and know I don’t belong in the train station.”

He didn’t get it. He grinned anyway. “Feisty. I like that.”

She gave him a look that could curdle wine, left the cup on the nearest table, and walked out.

Outside the building, the city was hushed and yellow-lit. Her ears rang from the change in pressure. She walked toward a corner bench, arms crossed, coat pulled tight, letting the night soak back into her skin.

Her payphone card was still in her bag. She crossed the street, slid into a booth. Dialed home.

The phone rang twice.

“Aló?” Her father’s voice—rich, warm, unmistakably gentle.

“Hi, Daddy.”

“Mi amor… You sound tired. Are you alright?”

“Just stepped out of a party. It was… too much. Too loud.”

“Of course it was. You're not a girl made for noise—you’re made for ideas.”

She laughed softly. “You always say that.”

“It’s always true.”

Then her mother’s voice, layered with a sleepy laugh. “Is she still awake? Zafie, corazón, are you wearing your scarf? It’s cold this time of year in Bologna, no?”

“I have my coat. Marceline forgot her bag. I went to give it back.”

“That was kind of you.”

“I didn’t like it there. Everyone talked too loud and said nothing.”

“Then you left. Good. You don’t need to stay in rooms that shrink you.”

Her throat tightened a little. She blinked hard. “Mamá… do you think I’m difficult?”

Her parents said nothing for a heartbeat, then her father answered, quiet and certain.

“No. You are precise.”

“And radiant,” her mother added. “And ours.”

Záfiro stared at her shoes. Her left sock had slipped down inside the heel.

She wasn’t sure what she felt. Maybe a little homesick. Maybe a little proud.

“Thank you,” she said.

And meant it.

Outside the building, the city was hushed and yellow-lit. Her ears rang from the change in pressure. She walked toward a corner bench, arms crossed, coat pulled tight, letting the night soak back into her skin.

Her payphone card was still in her bag. She crossed the street, slid into a booth. Dialed home.

The phone rang twice.

“Aló?” Her father’s voice—rich, warm, unmistakably gentle.

“Hi, Daddy.”

“Mi amor… You sound tired. Are you alright?”

“Just stepped out of a party. It was… too much. Too loud.”

“Of course it was. You're not a girl made for noise—you’re made for ideas.”

She laughed softly. “You always say that.”

“It’s always true.”

Then her mother’s voice, layered with a sleepy laugh. “Is she still awake? Zafie, corazón, are you wearing your scarf? It’s cold this time of year in Bologna, no?”

“I have my coat. Marceline forgot her bag. I went to give it back.”

“That was kind of you.”

“I didn’t like it there. Everyone talked too loud and said nothing.”

“Then you left. Good. You don’t need to stay in rooms that shrink you.”

Her throat tightened a little. She blinked hard. “Mamá… do you think I’m difficult?”

Her parents said nothing for a heartbeat, then her father answered, quiet and certain.

“No. You are precise.”

“And radiant,” her mother added. “And ours.”

Záfiro stared at her shoes. Her left sock had slipped down inside the heel.

She wasn’t sure what she felt. Maybe a little homesick. Maybe a little proud.

“Thank you,” she said.

And meant it.

Záfiro walked home in the quiet hum of Bologna’s old streets. The warm voices of her parents still lingered in her ears, like a shawl draped over her shoulders. Her father — so gentle, always defending her before she even needed defending. Her mother — fierce in her softness, making Záfiro feel chosen every day.

That was why the boys at the party had no effect on her. Their teasing, their half-hearted insults wrapped in compliments — they didn’t scratch. Her smooth, golden-brown skin had been tempered in better hands. She didn’t hunger for male approval the way they seemed to assume. Her dad had taught her to expect kindness. Her mom, to walk away from anything less.

But Arturo…

She turned the corner to her apartment and walked up the creaky stairs. Her key trembled slightly in the lock. She let herself in, dropped her bag, toed off her shoes. The kitchen light glowed dimly. She poured a glass of water but didn’t drink it.

Arturo was different.

He didn’t flatter. He observed. And somehow that made everything he said land with more weight.

“You’re fractious. Unruly. Brilliant.”

It wasn’t flirting. Not in the way she was used to. It wasn’t cheap. It wasn’t even warm. It was just true. And that… that was the problem.

Because now she was lying in bed, blanket pulled to her chin, toes cold but not moving to fix it, thinking about the way he’d hovered beside her earlier — the subtle gravity of his presence. The way he’d leaned to read what she was writing, eyes scanning her annotations like they were rare text. The warmth of his palm, light but certain on the small of her back when she’d hunched too long over her notes.

Nothing had been said. Not really. But her body still remembered it.

And the worst part was…

It wasn’t about his body. Not yet. It was the way she felt around him. Like her brain was the most seductive thing in the room. Like everything she’d been starved of in years of being the weird, precocious girl — every gold star, every rare compliment she had to wrestle from the world — suddenly poured out of him without even trying.

It made her want to earn more. Made her sit up straighter. Argue harder. Show off the full power of her thoughts just to hear his low hmm of approval.

She turned on her side and buried her cheek in the pillow, eyes wide open in the dark.

Was this how it started?

He probably didn’t know. He was probably like her. So used to not being praised, not being told good girl, not being looked at like he was a thing to be cherished — that when someone did make the effort, it rewired something.

She pulled the blanket over her face and groaned softly into it.

“Stop it,” she whispered to herself.

But her pulse didn’t listen.

0 notes

Text

A little queer fangirl daydreaming 😶🌫️ while sketching Star Wars baddie Shin Hati 🧡🤍💖 Next I’m drawing her lover Sabine 😉

Graphite drawing on paper

#wolfwren#star wars#shin hati#sabine x shin#shin x sabine#shinbine#ivanna sakhno#ahsoka#lgbtq#representation matters#sabine wren#sapphic#sith lord#space lesbians#dark side#shin hottie#redemption arc#portrait#graphite#graphite drawing#enemies to lovers#i ship it#i ship it so hard#pining#Spotify

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I'm not sure if you're still open fkr requests, but if your are, could I request a TWST matchup? (if not, feel free to ignore this <3)

I'm 5ft 3, female, ginger (longish pixie cut), pale, have blue eyes, and I have freckles. My style is a spectrum between cute/elegant and goth/edgy. It's kind of whiplash inducing tbh, lol. I go by Fae (short for my full name).

I'm an artist (even going to school for it). I work both traditionally and digitally, but I'm best with just simple graphite (suck at painting tho).

I also love just about anything crafty. I bind my own sketchbooks, weave bracelets, crochet, and do oragami. I also adore the outdoors. It's all so beautiful and I love photographing the beauty I see in it (working on learning to draw landscapes too). Reading and writing are also some of my hobbies. (Instruments too I guess. I play trombone and am learning flute)

If I was in TWST I think I'd either join the science club or the mountain lovers club (or make my own art club cause they really need one). Dorm wise, I really think ramshackle fits me best. I love how much character the place has and I'm just a sucker for old houses. That and I feel like Ramshackle is a dorm for misfits that don't fully fit into common categories.

My resting face is kinda menacing, but I swear I'm nice. I don't usually approach people first cause that's awkward, but once you get me talking I YAP. All of my friends kinda just took me in like a stray cat they found in a dumpster. Apparently I look upset a lot, but I'm usually not. I'm a realistic optimist (if that makes sense). I'm always daydreaming.

Anyway, feel free to ignore this! Thank you for taking the time to read and consider it!

I love your writing regardless and hope you have a lovely day <3

Thanks for the compliments and the request. Unfortunately normal requests are currently closed because I’ve got too much stuff going on rn between working on Scrapbook Memories, Ramadan, and the dreaded adult task of *gags* jury duty. Im only taking matchup exchanges and finishing already pending requests right now. Feel free to resend this request when matchups are open again. ❤️

#multi fandom blog#multifandom account#multifandom#multifandom writer#multi fandoms posts#multifandom fanfiction#multifandom x reader#multifandom imagines#matchups#anon ask

0 notes

Text

Does anyone get struck with the need to create something, but nothing fills the need u till you turn of your brain and your body does it for you?

Eg: doodling on paper, doodling online, knitting, music, daydreaming, writing

Turns out graphite doodling works if I stop trying and let the vibes guide me

#art#doodle#vibes#I think this is autism#I think this is adhd#I can’t tell the diff#maybe I’m just deaf and this is how I cope#deaf not dead btw

1 note

·

View note

Text

Who: Rocky Barnes

What: Vehla Dixie Sunglasses in Honey Tort/Graphite (200.00€) Where: Instagram - August 7, 2024

Worn with: Daydreamer tank, Rhode pants, M.Gemi sandals, Paris/64 bag

#rocky barnes#fashion#vehla#2024#sunglasses#august 7 2024#august 2024#instagram 2024#instagram#fashion inspo

0 notes

Text

The Diary of a Ghost Girl.

As the working week blended into the calendar, I found myself becoming more and more enthralled with the thought of finally being alone. To be left in solitary confinement with my obscure fantasies, a dark shadow casted onto the sunlit pavement. Like a diary at my fingertips, ready to be printed on my bed sheets and smeared against my mirror. Those periods of being by myself pulled me into moments of bliss that have convinced me that loneliness is a drug. An orange bottle full of tiny blue pills labeled: self indulgence.

Once the weekend came, my own ghost of isolation followed behind me and whispered sweet solitudes in my ear. It haunted my subconscious with daydreams that tamed my soul into consolation. Whenever I was lonesome I was able to conform into whatever I wanted, feel whatever I saw pleasurable, and reside wherever my mind decided to plant its seed.

On Saturday, I went swimming. It was not until I was neck deep in the ocean that I realized I had never learned how to. I kicked my legs and flailed my arms, but anchors were tied to my feet and handfuls of seaweed filled my palms. It was not long before my limbs deemed themselves exhausted, and the waves engulfed me entirely. My consciousness was stuck between the limbo of eagerness and relief, flickering like the indecisive flame of a candlestick pooling with wax. Alone I traveled the sea; facedown I stared at the dark abyss that was beneath me.

My hair flew around in gusts of wind like a tattered sail as my corpse floated across the water. It was as if I were a corked bottle made of glass, stuffed to the brink with angst and secrets. The pages inside were left dry and untouched, only for the ocean's eyes to consume. I was headed in the direction of a serene storm. My body was a hostage to the rain clouds pumped full with gasoline, ready to spill out of the tank and light my mind on fire.

I could not help but bask in that moment of tranquility, letting the feeling of loneliness sink into my skin and embrace me from the inside out. I fell in love. The sun drank my body in, swallowing me whole and gulping me down like it had never touched a drop of water. Soft whistles of wind and lullabies of waves sang me to sleep. Compelling tides siphoned me further away from reality as blackness tugged at my heartstrings like a naïve puppet. I felt like Emily Dickinson ready to exclaim, “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” into the fishy air, my voice fading away like my own identity was.

My eyes blinked back tears of salt and my lungs inhaled hot toxic air. I exhaled slowly like I had just breathed in the last draw of a cigarette, the ashy filter burning my fingertips as time evaporated with the smoke that swirled around me. It felt almost as if that very moment was where I was always destined to dissipate. I was finally set free.

On Sunday morning I woke up with ocean water caked in my hair and fishing twine wrapped around my wrists. I unraveled myself from the restraints and walked to my mirror streaked with hidden desires and affliction. The girl looking back at me now had paint splattered on her overalls and graphite smudged across her cheeks. It felt like Sylvia Plath’s mirror was before me, the frosted glass whispering my insecurities back to me.

My reflection transformed into a blank canvas, the burnt cigarette bud had now converted into a wooden handled paint brush. Shades of red, yellow, and blue seethed out of my pores, dripping down my body like a temple coated in a golden hue. The colors mixed together to create purples, oranges, and greens as a labyrinth of rainbows bled down my arms.

The fate of a new creation was placed into my hands, a sacred role that made my stomach churn with excitement. I grasped onto my brush and ran it down my forearm, collecting a bundle of achromatic violet. I closed my eyes and inhaled the scent of paint thinner, while the silence that surrounded me buzzed in my ears like pollinating bees. Once my eyes were level with the white slate that was in front of me, I picked up my hand and began plastering my vulnerability all over the four walls.

With each stroke of my brush I felt more and more at ease. A sense of contentment resided inside me, filling up my cup of isolation with spectrums of pigment. There was no question that what I created was thought to be right or wrong; whatever my brain constructed was pure and permissible. Nobody else was around to convince me otherwise, and I became an ill minded patient at the mercy of my own recovery.

I was sick off of paint fumes but fueled by my yearning to design a paradoxical reality that replaced my brains gray matter with color. I took a step back to admire the blotches of my soul that decorated my self stretched canvas. As nightfall came and the moon illuminated through my window, my walls were once again washed clean.

When Monday came around again, I was back behind the wheel driving to my unavoidable occupation crowded with gossiping people. The thought of being alone became a distant dream once again, and I was left begging for Saturday to embrace me one more time. I spent the commute reliving what the oceans kelp felt like threaded between my fingers, and what the shade of teal looked like stained all over my walls. Until I was reunited with my fantasies, blueprints of fervorous solitude brought my mind solace. Although at the time being, my creations were bound inside the diary of a ghost girl.

- S.R.G. (2022)

0 notes

Photo

Oh my gosh. It’s been almost six months, but it’s finally finished! I cannot express how thrilled I am with this piece.

2 notes

·

View notes