#J. Marion Sims

Quote

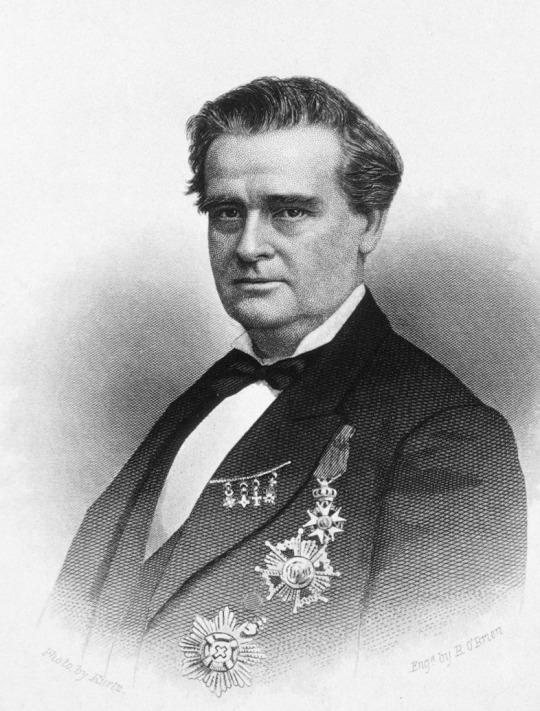

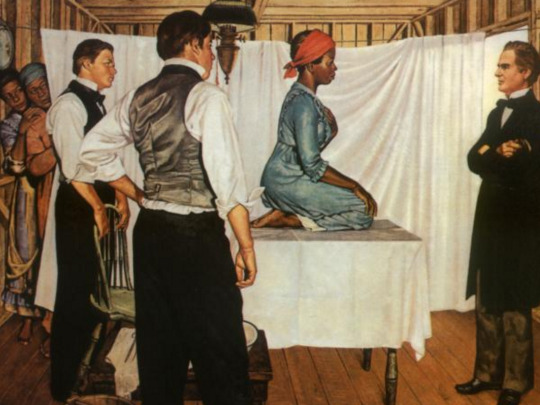

Dr. Marion Sims, who many consider "The Father of American Gynecology", bought and raised female slaves for the express purpose of using them for experimentation (Washington 55). Slave quarters and backyard shacks were the setting for his reproductive experiments pertaining to vesicovaginal fistula, cesareans, bladder stones, and ovariotomy, for example.

from Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World by Zakkiyyah Iman Jackson

#Zakiyyah Iman Jackson#hegemonic violence#hegemonic knowledge#the roots of the hold#antiblackness as the foundation of the world#J. Marion Sims

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

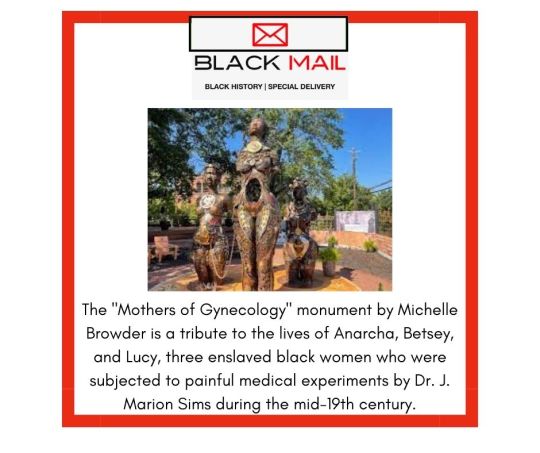

The “Mothers of Gynecology” Monument: Honoring The Lives Of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy

The "Mothers of Gynecology" monument by Michelle Browder, stands as a powerful testament to the exploitation and suffering of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy— enslaved women, mothers who endured tortuous pain in the name of medical advancement.

Welcome to Black Mail, where we bring you Black History—Special Delivery!

The “Mothers of Gynecology” monument by Michelle Browder, unveiled in Montgomery, Alabama, in 2021, stands as a powerful testament to the resilience and suffering of Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy—three enslaved black women, mothers who bore the burden of J. Marion Sims’ brutal medical experiments during the mid-19th century,…

View On WordPress

#Black History#Black History Month#blackmail4u#Enslaved Women#J Marion Sims#medical racism#Michelle Browder#Racism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity by C. Riley Snorton

The story of Christine Jorgensen, America’s first prominent transsexual, famously narrated trans embodiment in the postwar era. Her celebrity, however, has obscured other mid-century trans narratives—ones lived by African Americans such as Lucy Hicks Anderson and James McHarris. Their erasure from trans history masks the profound ways race has figured prominently in the construction and representation of transgender subjects. In Black on Both Sides, C. Riley Snorton identifies multiple intersections between blackness and transness from the mid-nineteenth century to present-day anti-black and anti-trans legislation and violence.

Drawing on a deep and varied archive of materials—early sexological texts, fugitive slave narratives, Afro-modernist literature, sensationalist journalism, Hollywood films—Snorton attends to how slavery and the production of racialized gender provided the foundations for an understanding of gender as mutable. In tracing the twinned genealogies of blackness and transness, Snorton follows multiple trajectories, from the medical experiments conducted on enslaved black women by J. Marion Sims, the “father of American gynecology,” to the negation of blackness that makes transnormativity possible.

Revealing instances of personal sovereignty among blacks living in the antebellum North that were mapped in terms of “cross dressing” and canonical black literary works that express black men’s access to the “female within,” Black on Both Sides concludes with a reading of the fate of Phillip DeVine, who was murdered alongside Brandon Teena in 1993, a fact omitted from the film Boys Don’t Cry out of narrative convenience. Reconstructing these theoretical and historical trajectories furthers our imaginative capacities to conceive more livable black and trans worlds.

#black on both sides#black on both sides: a racial history of trans identity#c. riley snorton#transfem#transmasc#trans book of the day#trans books#queer books#bookblr#booklr

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity by C. Riley Snorton

goodreads

The story of Christine Jorgensen, America’s first prominent transsexual, famously narrated trans embodiment in the postwar era. Her celebrity, however, has obscured other mid-century trans narratives—ones lived by African Americans such as Lucy Hicks Anderson and James McHarris. Their erasure from trans history masks the profound ways race has figured prominently in the construction and representation of transgender subjects. In Black on Both Sides, C. Riley Snorton identifies multiple intersections between blackness and transness from the mid-nineteenth century to present-day anti-black and anti-trans legislation and violence.

Drawing on a deep and varied archive of materials—early sexological texts, fugitive slave narratives, Afro-modernist literature, sensationalist journalism, Hollywood films—Snorton attends to how slavery and the production of racialized gender provided the foundations for an understanding of gender as mutable. In tracing the twinned genealogies of blackness and transness, Snorton follows multiple trajectories, from the medical experiments conducted on enslaved black women by J. Marion Sims, the “father of American gynecology,” to the negation of blackness that makes transnormativity possible.

Revealing instances of personal sovereignty among blacks living in the antebellum North that were mapped in terms of “cross dressing” and canonical black literary works that express black men’s access to the “female within,” Black on Both Sides concludes with a reading of the fate of Phillip DeVine, who was murdered alongside Brandon Teena in 1993, a fact omitted from the film Boys Don’t Cry out of narrative convenience. Reconstructing these theoretical and historical trajectories furthers our imaginative capacities to conceive more livable black and trans worlds.

Mod opinion: I haven't read this book yet, but it sounds very interesting and is on my tbr.

#black on both sides#black on both sides a racial history of trans identity#c. riley snorton#polls#trans lit#trans literature#trans books#lgbt lit#lgbt literature#lgbt books#nonfiction#history#trans studies#to read

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truly understanding that male dominant society has long striven to define "woman" as a discrete biological category: female, with the purpose of stripping certain people of personhood can really challenge so much of the pro-gender/sex binary bull we are all fed from childhood.

We can no longer ignore how biology, biological discourse, and the terms and words we use to refer to our corporeal "reality" are structured by historic and current social and political views. A biological reality becomes cognitively significant through this discourse and these terms we use and concepts we engage with. So, defining “women” as “females” -- and thus emphasizing a label that is ascribed to all at birth along patriarchal standards of "correct" genitalia and "best" fertility -- is itself a political choice influenced by one’s socialization rather than one that can claim to neutrally reflect what the world is “really” and "materially" like.

The fact society defines "women" as ova producers and child bearers (i.e. the very definition of human female; the sex that has the ability or potential to bear offspring or produce eggs) or even as vagina havers and uterus havers (i.e. the insistence that, "only someone with a uterus or vagina is a woman") is a result of socialization in a male dominant society that has striven to define "woman" as a discrete biological class.

Even radical feminist Catharine MacKinnon understood that to be defined as female is to be an object. You do not get to consent to yourself; to your femaleness. It has been defined and ascribed to you. Because male dominant society must see to it that female is a woman and "clearly" a woman, opposite that of "man." It must see to it that women are women and men are men and that the two ought be separate because this allows said society to prescribe certain bounds to each group.

Certain bounds of behavior.

Certain bounds of public life.

Certain bounds of private life.

Certain bounds of presentation.

And this all helps foster the reification of gendered associations that decrease the perception of women as empowered agents and even human. These bounds of behavior assign to men the role of Aggressor and to women the role of passive Recipient, helping to reproduce sexual violence against women by decreasing their agency. These social prescriptions encourage men to act on behalf of women from making financial or relationship decisions, to deciding when and where and how a woman has sex, to the definition and social prescription of "female," and to the reproductive alienation of those assigned female.

Thus, female is far from a neutral scientific observation. It was defined by the patriarchy and the white supremacist power structure and it was designed to strip certain people of their agency and humanity. It is a classification that popped up during the period of post-enlightenment rationality as the European colonial system controlled the world. Enlightenment rationality brought to Europeans a renewed fascination with analyzing and categorizing the world, most especially its people. The enlightenment fascination with categorization was the justification for the colonization of and dominance over non-white, non-European people.

But from the enlightenment also emerged the idea that a “natural law” governed all people; that we were subject to a natural hierarchy; that there were some individuals more human than others. The modern definitions of "male" and "female" evolved alongside our creation of the definitions for "black" and "white" and alongside our definitions of and prescriptions of personhood.

“In the United States, the man known as the father of gynecology, J. Marion Sims, built the field in the antebellum South, operating on enslaved women in his backyard, often without anesthesia—or, of course, consent. As C. Riley Snorton has recently documented, the distinction between biological females and women as a social category, far from a neutral scientific observation, developed precisely in order for the captive black woman to be recognized as female—making Sims’s research applicable to his women patients in polite white society—without being granted the status of social and legal personhood. Sex was produced, in other words, precisely at the juncture where gender was denied. In this sense, a female has always been less than a person.”

Females

Andrea Long Chu

The terms and words we use to refer to our material reality; to our sex, are structured by the patriarchy and white supremacy. And this cannot be ignored.

#txt#feminism#transgender#I am going to tag this#radical feminism#simply because#it mentions MacKinnon#sexism#misogyny#patriarchy#white supremacy#gender#radblr#terfblr#but not radfem safe#check yourselves#defining women as 'females' is not the feminist take you think

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

J. Marion Sims is called the "Father of Gynecology" due to his experiments on enslaved women in Alabama, who were often submitted as GUINEA PIGS by their plantation owners who could not use them for sexual pleasure.

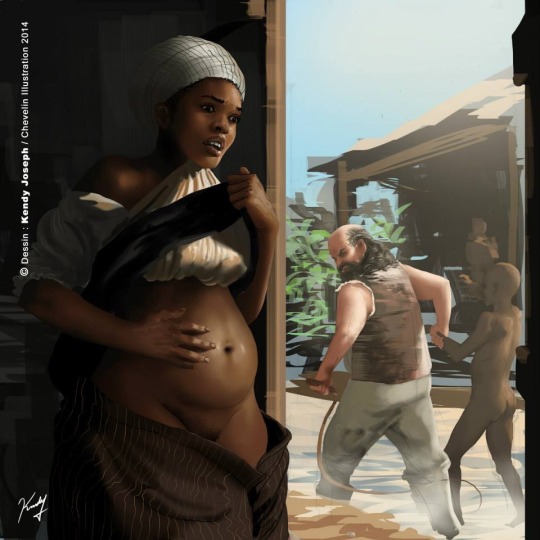

Anarcha, one of those women, was an African-American slave woman who was forced to regularly undergo surgical experiments while positioned on Sims' table, squatting on all fours and FULLY AWAKE without the comfort of ANY anesthesia.

It's been calculated that Anarcha was operated on roughly 34 times between 1845 - 1849. These operations helped Dr. Sims hone his techniques and create his gynecological tools.

It would be more than appropriate to credit Anarcha, along with other nameless slave women, as the "MOTHERS OF GYNECOLOGY"

x since the day i heard of this man and what he did i have hated his guts and prayed that he is burning in the hottest section of hell. one of the many great things to come out of the black lives matter protests was that we took down that disgusting statue dedicated to him.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wrote this poem for my Root Beer patron (20$). This is a very short poem about the refusal of the Human, the seizing of the body, and the surveillance of the flesh.

Illustration of Dr. J. Marion Sims with Anarcha by Robert Thom. Anarcha was subjected to 30 experimental surgeries.

The illustration above best visually describe the poem. Here is an excerpt to whet your appetite:

She wants to know everything

there's to blaze;

a bare scribble of wiry veins,

a crucible of steel,

a marrowed blackberry.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

the new statesman recently published dueling essays by richard dawkins and jacqueline rose. dawkins' essay is entitled "Why biological sex matters" and rose's is "The gender binary is false"

i'm not envious of rose's position here at all. dawkins, for all his issues, is a very clear science writer, which redounds to him being a better writer in general. but it's beyond frustrating to see someone defending a position i agree with with extremely low quality argumentation.

rose writes:

"What is a woman?” The formulation has the merit of suggesting that to be a woman, far from being obvious, is a question, and one susceptible to more than a single reply. This is encouraging at a time when the fight over the definition of what a woman is has taken on such virulence. Being a woman is at risk of becoming a protected category, as the binary man/woman hardens into place.

at risk... of becoming... a protected category... well, i have some news for you that you're not going to like. i'm not sure how it's evaded you for this long, but better late than never, huh?

i'm inferring here that rose is using it in a more colloquial sense than i'm reading this. but "protected category" has a very specific (and legal) definition so. i'm not sure why you'd verbalize your point this way. but even that colloquial usage doesn't work! rose is a feminist professor, and i'm sure she'd agree that women have to deal with some metric of vulnerability.

she continues:

This is happening even though it has always been a central goal of feminism to repudiate the very idea of womanhood, as a form of coercive control that means the end of freedom.

holy fuck, this is so stupid. or more fairly, this is highly debatable and it comes down to what she's talking about when she says "womanhood". and she never spells it out.

and. um. let's get to the "best" part...

In fact, the term “female”, as distinct from women, has its own tale. As the New York Magazine critic Andrea Long Chu has written in her book Females (2019), the biological category “female”, as it is understood today, was developed in the 19th century as a way of referring to black slaves. A female black slave was someone refused “the status of social and legal personhood”. To that extent, Chu observes, “a female has always been less than a person”. To assume that “female” is a neutral biological category is, therefore, historically naive and racially blind.

uh. alright. this isn't true. like at all. don't even get me started on andrea long chu dude. sure, she went to duke, but that doesn't exonerate her from being a bullshit artist. which she is. and from what i've read of her work, i seriously don't understand why she transitioned at all. in her mind, women are pretty much empty holes for the world to abuse. maybe she, like, hates herself and the "women are the lowest thing on earth, this is what i deserve" thing is an insane projection. who knows? you couldn't make me bother wanting to figure it out if you paid me.

but this also isn't an accurate reading of that part of chu's book either... this is what it actually says.

As far back as the 14th century, the word female was used to refer to women, with a particular emphasis on their childbearing capacity. But it arguably didn't acquire the technical sense of "a human mammal of the female sex" until the rise of the biological disciplines of the 19th century. In the United States, the man known as the father of gynecology, J. Marion Sims, built the field in the Antebellum South, operating on enslaved women in his backyard, often without anesthesia or, of course, consent. As C. Riley Snorton has recently documented, the distinction between biological females and women as a social category, far from a neutral scientific observation, developed precisely in order for the cap to block women from being recognized as female, making Sims' research applicable to his women patients in polite white society without being granted legal personhood. Sex was produced, in other words, precisely at the juncture that gender was denied. In this sense, a female has always been less than a person.

so, c riley snorton is a black trans scholar at uchicago. chu's referencing chapter 1 of his book called "Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity". i read that chapter, and i cannot for the life of me figure out where she got this idea that snorton is arguing that sims invented a new meaning for the term "female" for racist reasons or for any other reason. i don't speak theory, so maybe i missed it, but i think what's happening here is that jacqueline rose is misreading andrea long chu, who's misreading c rily snorton, who may very well be misreading j marion sims for all i know. snorton says in the introduction to his book, quote: "This is not a history per se, so much as it is a set of political propositions, theories of history, and writerly experiment." so there's that. and if you look up the etymology for the term female (which i did, i've gotten this far), it comes from the latin word for young woman or girl. so even in the 14th century, the term was applied to people.

this is just... laughable, honestly. is jacqueline rose going senile? are we human or are we dancer? i just wish people wouldn't throw up all this smoke to make these bullshit arguments. you can support trans rights without doing this shit.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

well this is gonna be a semi disturbing post but it’s in my head so. woe horrible medical knowledge be upon yee all I guess

#abuse tw#medical tw#medical abuse tw#medical trauma tw#racism tw#there aren’t enough tws in the world honestly#but I do think this is a thing everyone should know about

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

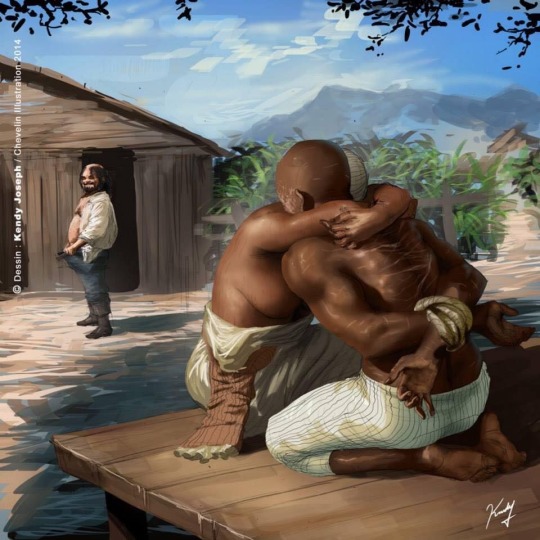

To combat the high rate of death among slaves, plantation owners demanded females start having children at 13.

By 20, the enslaved women would be expected to have about five children.

An enslaved woman was a sex tool beneath the level of moral considerations.

She was an economic good, useful, in addition to her menial labor, for breeding more slaves. To attain that purpose, the master mated her promiscuously according to his breeding plans.

The Master, his son(s) and other members of his family took turns with her to increase the family's fortune and to satisfy his extramarital sexual desires. Guests and neighbors were also invited to this luxury.

As an inducement, plantation owners promised freedom for enslaved female once she bore 15 kids.

Also the brutal enslavers also castrated black males and use black females for gynecological research all while not providing them with anesthesia.

J. Marion Sims "the father of modern gynecology" purchased black women slaves and used them as guinea pigs for his untested surgical experiments. He repeatedly performed genital surgery on black women without anesthesia because according to him, "Black women don't feel pain."

Anarcha, one of those women, was an African-American slave woman who was forced to regularly undergo surgical experiments while positioned on Sims' table, squatting on all fours and fully awake without the comfort of any anesthesia.

It would be more than appropriate to credit Anarcha, along with other nameless slave women, as the "MOTHERS OF GYNECOLOGY".

Slave masters also had sex farms where they would rape black men, women, and children. The raping of black men was called buck breaking.

Marriages among the African slaves were also not recognized by their white enslavers.

•••

Para combatir la alta tasa de mortalidad entre los esclavos, los dueños de las plantaciones demandaban que las mujeres se embarazaran a los treces años.

A la de edad de los veinte años, se esperaba que las mujeres negras tuviesen por los menos cinco hijos.

La mujer esclavizada era una herramienta sexual por debajo del nivel de las consideraciones morales.

Ella era un bien económico, útil, además de su trabajo para criar más esclavos. Para lograr ese propósito, el dueño la apareaba promiscuamente de acuerdo con sus planes de crianza.

El dueño, su(s) hijo(s) y otros miembros de la familia se turnaban con ella para aumentar la fortuna familiar y satisfacer sus deseos sexuales extramatrimoniales. Huéspedes y vecinos también fueron invitados a este lujo.

Como incentivo, los dueños de las plantaciones prometían libertad a la mujer esclavizada una vez que diera a luz a quince hijos.

Además, los esclavizadores también castraban a los hombres negros y utilizaban a las mujeres negras para la investigación ginecológica sin proporcionarles anestesia.

J. Marion Sims, "el padre de la ginecología moderna", compró esclavas negras y las usó como conejillos de indias para sus experimentos quirúrgicos nunca antes probados. En repetidas ocasiones realizó cirugías genitales en mujeres negras sin anestesia porque, según él: “Las mujeres negras no sienten dolor".

Anarcha, una de esas mujeres, era una esclava afroamericana que se vio obligada a someterse a experimentos quirúrgicos regularmente mientras estaba colocada en cuatro en la mesa de Sims, completamente despierta sin el uso de ningún tipo de anestesia. Sería más que apropiado acreditar a Anarcha y a otras esclavas no mencionadas, como las "MADRES DE LA GINECOLOGÍA".

Los dueños de esclavos también tenían granjas sexuales donde violaban a hombres, mujeres y niños negros. A la violación de hombres negros se le llamaba “romper el dinero”.

Los matrimonios entre los esclavos africanos tampoco fueron reconocidos por los esclavizadores blancos.

#blacklivesmatter#history#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#knowyourhistory#blackbloggers#black history is american history#blackwomenmatter#blackchildrenmatter#gynecology#newpost#long reads#black women#blacklivesalwaysmatter#english#spanish#share#read#blackpeoplematter#like#follow#historyfacts#blackblogger#translator#warning#read and learn

19 notes

·

View notes

Audio

(Southern Vangard)

Episode 365 - Southern Vangard Radio

BANG! @southernvangard #radio Ep365! Summer is here in the A and your guys Doe and Meeks are very happy. Crack open the Hamm’s and let’s get busy! We have TWO WORLD EXCLUSIVES this week, Vangardians: First up - NAPOLEON DA LEGEND, J SCIENIDE and our own DJ JON DOE with “LUXURIOUS APARTHEID”, which drops this Friday 6/9. This is the first single from their upcoming album “GOAT VS. SHEEP.” Right behind it is the 2nd single from the SPEAKER BULLIES (SUPASTITION X PRAISE) upcoming album. This cut features the incomparable SKYZOO, and drops 6/16. Cop both of these heat rocks when they drop. Other than that, it’s that uncut raw ish, it’s that Smithsonian Grade ish, it’s that Memphis meets Glasgow ish and it’s that YOU WAAAAALCOME!!!!! #SmithsonianGrade #WeAreTheGard // southernvangard.com // @southernvangard on all platforms #undergroundhiphop #boombap #DJ #mixshow #interview #podcast #ATL #WORLDWIDE #RIPCOMBATJACK

Recorded live June 4, 2023 @ Dirty Blanket Studios, Marietta, GA

southernvangard.com

@southernvangard on all platforms

#SmithsonianGrade #WeAreTheGard

twitter/IG: @southernvangard @jondoeatl @cappuccinomeeks

"Round N Round" - Talk Break Inst. - Es-K & Type.Raw

"Summer School" - DOECINO (DJ Jon Doe & Cappucino Meeks)

"Luxurious Apartheid" - Napoleon Da Legend X J Scienide ft. DJ Jon Doe ** WORLD EXCLUSIVE **

"Godspeed" - Speaker Bullies (Supastition X Praise) ft. Skyzoo ** WORLD EXCLUSIVE **

"Fruit" - Dex (prod. Praise)

"I'm Coolin'" - Spoda x VStheBest215

"Nice Weather" - Termanology

Talk Break Inst. - "About Me" - Es-K & Type.Raw

"Sitting Duck" - J Scienide ft. Damu The Fudgemunk

"We Can Do That" - Verbz, Nelson Dialect & Mr Slipz

"Big Foot" - Squeegie O

"Marion Barry" - The Architect ft. Mickey Diamond & Cochise MC

"C-H-O-P" - Tone Chop & Frost Gamble

"Window Pain" - Termanology ft. Reks

"Midnight Express" - Maze Overlay & Sadhugold ft. Snotty

Talk Break Inst. - "M.V.P." - Es-K & Type.Raw

"DOECINO" - DOECINO (DJ Jon Doe & Cappucino Meeks)

"Preemo On Drugs" - Al-Doe & Spanish Ran

"Casket Suit" - Bub Styles x Retrospec ft. $auce Heist & Dot Demo

"Gadzooks! (Em Eff Yoom)" - Eff Yoo x Level 13

"Stockholm Syndrome" - Lord Juco & Finn ft. Ty Da Dale

"Methadone" - Rufus Sims

"Summers Eden" - Let The Dirt Say Amen, Sean Born, Damo Hicks

"Change My Mind" - Domo Genesis & Graymatter

Talk Break Inst. - "Nobody Better" - Es-K & Type.Raw

** TWITCH ONLY SET **

"Tha Realness" - Group Home (prod. DJ Premier)

"Brownsville" - M.O.P. (prod. DJ Premier)

"The Game" - Pete Rock ft. Raekwon, Prodigy, Ghostface Killah

SOUNDCLOUD

https://soundcloud.com/southernvangard/episode-365-southern-vangard-radio/

https://on.soundcloud.com/7bTps (SHORT LINK)

APPLE PODCASTS

https://itun.es/us/QyyX9.c/

SPOTIFY PODCASTS

http://bit.ly/svrspotifypodcasts

YOUTUBE

https://youtu.be/UnQSD5AgGs8

GOOGLE PODCASTS

http://bit.ly/svrgooglepodcasts

TWITCH

http://twitch.tv/southernvangard

MIXCLOUD

https://www.mixcloud.com/southernvangard/episode-365-southern-vangard-radio/

#SoundCloud#music#Southern Vangard#Hip-Hop#Rap#Underground Hip-Hop#Boom Bapradio#SouthernVangard DJJonDoe EddieMeeks EsK TypeRaw DOECINO NapoleonDaLegend JScienide SpeakerBullies Supastition Praise Skyzoo Dex Spoda VStheB

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anarcha Westcott (c. 1824 – 1869/70) was an enslaved woman who underwent a series of painful experimental surgical procedures conducted by physician J. Marion Sims, without the use of anesthesia, to treat a combination of vesicovaginal fistula and rectovaginal fistula. Sims's medical experimentation with her and other enslaved women, and its role in the development of modern gynecology, has generated controversy among medical historians. She was illiterate (by law), and most information comes from records kept by her enslavers and Sims' records of his experiments. She first turns up in the autobiography of J. Marion Sims as a "little mulatto girl" living in the doctor's house; as he says on the following page, "a little negro girl would sleep in the room with me, and hand me a drink of water occasionally." She next turns up as "a young colored woman, about seventeen years of age, well developed" belonging to Mr. Wescott, who lived in Montgomery. Sims was called in to assist after her labor lasted three days. No comments on how she became pregnant, so the unidentified father of her stillborn child may well have been Mr. Wescott or Dr. Sims. She was brought to Sims because she had several unhealed tears in her vagina and rectum – a vesicovaginal fistula and rectovaginal fistula. Which caused her to have excruciating pain from her uncontrollable bowel and urine movements flowing through her open wounds. Sims performed 30 experimental, nonconsensual operations. She was given no anesthesia. Sims administered opium, which was then an accepted method to treat pain. The experimental procedures that Sims performed on her and other enslaved people revolutionized gynecological surgery; the technique Sims developed became the first-ever treatment for vesicovaginal fistulae. On December 21, 1856, she was admitted to Sims' Woman's Hospital in New York, with the notation that she stayed about a month and was discharged as cured. A tombstone for an "Annacay", wife of Lorenzo Jackson, was found by chance in King George County, Virginia. In the 1870 Census, her name is spelled Anaky Jackson, and on her death record, Ankey. #africanhistory365 #Africanexcellence #womenshistorymonth https://www.instagram.com/p/CpuoCYLOWT0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary Louise Booth (April 19, 1831 – March 5, 1889) was an American editor, translator, and writer. She was the first editor-in-chief of the women's fashion magazine, Harper's Bazaar.

At the age of eighteen, Booth left the family home for New York City and learned the trade of a vest-maker. She devoted her evenings to study and writing. Booth contributed tales and sketches to various newspapers and magazines but was not paid for them. She began to do reporting and book-reviewing for educational and literary journals, still without any pay in money, but happy at being occasionally paid in books.

As time went on, she received more and more literary assignments. She widened her circle of friends to those who were beginning to appreciate her abilities. In 1859, she agreed to write a history of New York, but even then, she was unable to support herself wholly, although she had given up vest-making and was writing twelve hours a day. When she was thirty years old, she accepted the position of amanuensis to Dr. J. Marion Sims, and this was the first work of the kind for which she received steady payment. She was now able to do without her father's assistance, and live on her resources in New York, though very plainly.

In 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, she procured the advance sheets, in the French language, of Agénor de Gasparin's Uprising of a Great People. By working twenty hours a day, she translated the whole book in less than a week, and it was published in a fortnight. The book created a sensation among Unionists, and she received letters of thanks for it from U.S. Senator Charles Sumner and President Abraham Lincoln. But again, she received little compensation for her work. While the war lasted, she translated many French books into English, calculated to rouse patriotic feeling, and was, at one time, summoned to Washington, D.C. to write for the statesmen, receiving only her board at a hotel. She was able at this time to arrange for her father the position of clerk in the New York Custom House.

At the end of the civil war, Booth had proved herself so fit as a writer that Messrs. Harper offered her the editorship of Harper's Bazaar – headquartered in New York City – a position in which she served from its beginning in 1867 until her death. She was at first diffident as to her abilities, but finally accepted the responsibility, and it was principally due to her that the magazine became so popular. While keeping its character of a home paper, it steadily increased in influence and circulation, and Booth's success was achieved with that of the paper she edited. She is said to have received a larger salary than any woman in the United States at the time. She died, after a short illness, on March 5, 1889.

#Mary Louise Booth#women in history#women in literature#xix century#people#portrait#photo#photography#Black and White

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AAMC: Racism — not race — drives health disparities

When Linda Villarosa was pregnant with her daughter, she was surprised when her doctor recommended she go on bed rest and interrogated her about her health habits because her unborn baby was not growing as expected.

Villarosa, who had served as an editor for Essence, a lifestyle magazine for Black women, had written about healthy habits and strove to live a healthy life herself. She’d encouraged other Black women to change their diets and exercise regimens to help combat health disparities.

But despite her efforts, her baby was born at a low birth weight — an issue that impacts Black parents and babies at disproportionately high rates in the United States, even when accounting for education and socioeconomic status.

“How did my lived experience [as a Black woman in America] affect my own [birthing experience]?” Villarosa recalled wondering, speaking to attendees of Learn Serve Lead 2022: The AAMC Annual Meeting on Nov. 13 in Nashville, Tennessee.

Her personal experience was reflected in the data she gathered and the personal stories she encountered during her reporting for the New York Times Magazine on maternal mortality rates and disparities in this country and in writing her book, Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation.

“There has never been a time in this country when Black people have had equal health to White people and often other people of color,” Villarosa said.

She identified the sources of myths about Black bodies and people that, throughout American history, have labeled them as inferior and not needing or worthy of appropriate care: the so-called “father of modern gynecology,” J. Marion Sims, who operated on enslaved women without anesthesia, contributing to the myth that Black people do not feel pain as acutely as White people; Thomas Jefferson, who likely perpetuated the myth that Black people had inferior lung function to White people; and countless medical journals that validated racist studies as evidence-based science.

These myths have seeped into today’s health systems, contributing to persistent biases that label Black people as lazy and aggressive and make them less likely to receive appropriate health care, Villarosa said.

But the outlook isn’t all bleak, she added.

Medical students who are working to make anti-racism a priority at their institutions and administrators who respond to those calls to action give her hope for the future of medicine.

“They’re the future,” she said. “They’re the ones trying to know better and do better.”

Several weeks ago, Villarosa spoke with AAMCNews about her research and how academic medicine can foster change.

What role have you found racism itself, as opposed to socioeconomic status, plays in racial health disparities?

It’s the long-standing idea that it was something about the Black body or something about Black culture that was causing poor health outcomes and racial disparities, that it was genetics — in other words, that we were inferior in some ways to White people, whether it was a lack of education or high levels of poverty, with less interrogation of societal and institutional barriers. So that’s why I really set out to write the book — to disprove that there’s something wrong with us in some inherent way. And the first chapter is basically called, “Everything I thought was wrong,” because I believed that too.

When I was a young editor at Essence, I was really looking at these poor health outcomes and looking at racial health disparities obsessively and thinking if I just tell people or help educate people that are reading Essence magazine, who are in the millions, that we can change the health outcomes of Black people in the country. And my idea was, "If you know better, you do better." Then I realized, after going to public health school and really doing a lot of reporting in this area, that this kind of one-note idea that it was just poor people who were sick was wrong. And it really came to the front of my mind in 2017, when I was reporting on maternal and infant mortality among Black women for the New York Times Magazine and I started seeing these statistics that said we’re the only country where the number of birthing people and pregnant people who die or almost die related to pregnancy and childbirth is rising. And that Black women are three to four times more likely to die or almost die, and then that a Black woman with a master’s degree or more is still more likely to die or almost die than a White woman with an eighth-grade education. And I started to [think], “Wait, this cannot be only about education or lack of money or 'if you know better, you do better.' There's something else going on.”

Can you share any stories about how structural racism plays out in the health care system?

Well, I think I just want to mention two of them. The first is Simone Landrum, whom I was following for my 2018 story “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis.” When I met her, she had two children. She had just lost a baby and almost died, at least partially because her doctor didn’t listen to her and her legitimate complaints.

And then when I was at her child’s birth, I saw that happening again. I was in the labor and delivery room watching the medical providers who were all White really treat her with disrespect, ignore the things she was saying, and not treat her with the kind of care and kindness you would treat someone who had gone through a trauma the year before with a stillborn baby. … And I saw how distressed she was, and that kind of distress impacted her body and her baby. Luckily, she had a healthy baby, but I still was so surprised that everything I’d been researching unfolded in front of me.

Then when my current book Under the Skin was reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, it was a Black woman writing about the book and in the middle of the review, she talked about her own birth[ing experience], and she said that she had read my 2018 story and she was trying to do everything right. She was expecting to have a positive birth outcome, but how she herself was treated during the process led her to question herself, to blame herself, and to ultimately be happy that she had a healthy baby but also feel bad about the process and the experience. And I was surprised because right in the middle of a book review, it’s unusual to get this kind of really intense, personal story, but I appreciated it and it really confirmed much of what I have been looking into for the last few years.

Why do you think there is resistance to seeing racism as a health risk factor?

Well, I think it’s in the DNA of American character to assume that everybody has responsibility. They’re responsible for themselves and for their own health, wealth, and well-being, without questioning the forces of society and discrimination and other kinds of harm that are baked into the system. And it’s almost “un-American” to say anything bad about the country. What I learned, especially working on the [New York Times] 1619 Project, was it is Black folks who are questioning what’s going on in America and who are demanding a closer look at it, not because we don’t like the country, but because we care and want to engage in the system and work toward social change.

When I talk about discrimination and racism in the health care system itself, I’m very careful to cite a lot of evidence — and there is a lot out there — because I don’t want it to feel like I’m accusing individual physicians, nurses, midwives, health care providers, or policymakers of racism, because it’s not a question of individuals blaming individuals for their own health. It’s also not fair to blame individual health care providers for a problem in the system. And I think one of the solutions is to just admit that something is going on that is giving marginalized people a bad experience when we enter the health care system — not always but too often, and it’s been well documented. So it’s time to stop looking away from the problem and to figure out how to face it. One of the things that I’m really interested in is hospital systems and health care commissions mandating anti-racism or anti-bias, implicit bias training for its employees and to say everyone needs to go through this just as a matter of course to make sure we’re not poisoning the experience and the service that we’re giving people because they’re different from us. And I think there is a growing awareness of this and a growing acceptance of this as a solution.

What can medical schools do to start making these changes?

One thing to focus on is listening to students themselves. Many students who are in medical school and nursing school and midwifery school right now were learning about racism and discrimination against people of color — especially Black people — in high school or in college. So many of them are very aware of this and are wanting to do better and to be a different kind of provider and not take the old biases and prejudices into their practices-to-be. I think that’s really exciting, that there’s this swell of students who are trying to make a difference. And I think there are also medical educators and people that work on training medical students and nursing students who are trying to make a difference, and we have to lift up these stories and hold them up and say thank you and I’m really excited about that.

We know that medical research has abused people of color. Is there anything you’d like to see change in academic research to gain trust and stop perpetuating discrimination and abuse?

When you talk about vaccine hesitancy or Black people reluctant to enter the health care system or avoiding it, there’s this discussion of the Tuskegee syphilis study — which was in the 1930s through the 1970s — without much thought about how many people are reluctant to enter the health care system because something happened to them yesterday or something happened last week to someone that they love when they went to a doctor or went to some kind of health care provider, whether it was an extremely long wait or it was disrespect. And I think one of the things to think about is to listen to the stories. Oftentimes, I’ve seen where hospital systems, sometimes where I did initial reporting — I went back and they’re doing a restorative justice project to both acknowledge the stories of harm and to teach the people who are working in these systems that are often busy and hurried and sometimes underfunded that you have to listen to the folks’ stories and do better and not make the same mistakes over and over.

I think one thing that I learned over the last few years doing lectures and listening to seminars about these topics is how often Black researchers are overlooked, even when the research is about topics of interest to Black people or about diseases or problems that affect us. And I think we also have to look at who gets to study what and whose research is lifted up and whose gets celebrated — and even published. That’s one thing that I didn't know so much about, but I heard heartbreaking stories from Black researchers talking about how they were overlooked and how their research was less respected than other researchers’, even when the topic was something about Black people. So I think it’s important to also look at the ways we choose who is published and who is celebrated and who isn't.

#Racism — not race — drives health disparities#us health disparities#health disparities in Black and White#Black Lives Matter#Black Health Matter#US Racism Racism drives health disparities

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌈History Is Gay Books🌈

Black On Both Sides

A Racial History of Trans Identify

By: C. Riley Snorton

"The story of Christine Jorgensen, America’s first prominent transsexual, famously narrated trans embodiment in the postwar era. Her celebrity, however, has obscured other mid-century trans narratives—ones lived by African Americans such as Lucy Hicks Anderson and James McHarris. Their erasure from trans history masks the profound ways race has figured prominently in the construction and representation of transgender subjects. In Black on Both Sides, C. Riley Snorton identifies multiple intersections between blackness and transness from the mid-nineteenth century to present-day anti-black and anti-trans legislation and violence.

Drawing on a deep and varied archive of materials—early sexological texts, fugitive slave narratives, Afro-modernist literature, sensationalist journalism, Hollywood films—Snorton attends to how slavery and the production of racialized gender provided the foundations for an understanding of gender as mutable. In tracing the twinned genealogies of blackness and transness, Snorton follows multiple trajectories, from the medical experiments conducted on enslaved black women by J. Marion Sims, the “father of American gynecology,” to the negation of blackness that makes transnormativity possible.

Revealing instances of personal sovereignty among blacks living in the antebellum North that were mapped in terms of “cross dressing” and canonical black literary works that express black men’s access to the “female within,” Black on Both Sides concludes with a reading of the fate of Phillip DeVine, who was murdered alongside Brandon Teena in 1993, a fact omitted from the film Boys Don’t Cry out of narrative convenience. Reconstructing these theoretical and historical trajectories furthers our imaginative capacities to conceive more livable black and trans worlds."

~Alice 🌌

#nerd humor#nerdy memes#nerd#bookblr#book recommendations#book reccs#history is gay#black on both sides

2 notes

·

View notes