#John Smeaton

Text

In keeping with my All-Action blog title here is some windmill action.

Stoneferry by John Ward (1798–1849). Stoneferry is near Hull and the mills depicted, which both had five sails, were possibly a seed oil mill and a whiting mill (to crush chalk).

Four sail windmills were the most common types although there were examples with five, six and even eight sails. Civil engineer John Smeaton found the five sails were more powerful than those with four but harder to manufacture and repair. If a sail on a four sail mill was damaged the sail and the one opposite were removed and the mill continued to run with two. If one of the five sails was damaged then the windmill couldn't operate until it was repaired.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Temple, Crow Nest Park, Dewsbury

When first built the handsome gazebo in the grounds of Crow Nest in Dewsbury would have had views over the estate’s fine gardens and pleasure grounds. At the end of the 19th century Crow Nest was bought for the people of Dewsbury, and has now been a public park for 130 years. The Temple remains an ornament to the park, but sadly today it has a rather forlorn appearance.

Continue reading The…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

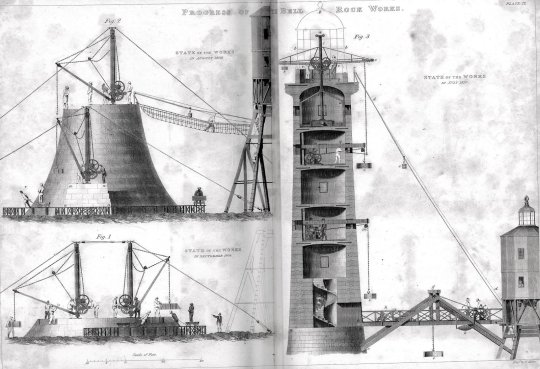

The Bell Rock Lighthouse, off the coast of Angus, was first lit on the 1st of February 1811.

Over 200 years after it was first built, the Bell Rock Lighthouse still stands - proudly flashing its warning light. Eleven miles out to sea off the east coast of Scotland, it is a remarkable sight - a white stone tower over 30m (100ft) high, rising seemingly without support out of the North Sea.

In fact, it is precariously poised on a treacherous sandstone reef, which, except at low tides, lies submerged just beneath the waves.

The treacherous reef on which it stands is in the North Sea, between the Firths of Forth and Tay, some 12 miles south of Arbroath and 14 miles south east of St Andrews. The red sandstone outcrop is 435m long and the lighthouse is founded on the main section, 130m long and 70m wide, and only 1.2m above the surface at low water spring tide.

The reef was known originally as Inchcape Rock or Cape Rock. According to tradition, in the 14th century the Abbot of Aberbrothok (Arbroath) placed a floating bell on it to warn mariners, hence its present name. Legend has it that sometime later a Dutch pirate removed the bell but he was later shipwrecked and perished on the same reef. The rocks were dangerous to ships sailing along the east coast of Scotland and by the end of the 18th century the need for a lighthouse was clear.

A severe storm in December 1799, in which about 70 vessels were wrecked, prompted Stevenson to propose a beacon-style lighthouse on six cast iron pillars.

Stevenson submitted a scale model of his idea to the Northern Lighthouse Board in summer 1800 — accurate physical modelling was to become something he often employed subsequently on important projects.

Stevenson drew the inspiration for his lighthouse design from the Eddystone Lighthouse, off the coast of Cornwall.

Built 50 years earlier by John Smeaton, this was a milestone in lighthouse design. Shaped with the now classic wide base, tapering to a narrow tower (Smeaton had modelled it on an oak tree he had witnessed defying a storm), it was the only off-shore structure that had until then managed to survive for any length of time against the constant battering of the seas.

Stevenson elaborated on this design. His lighthouse would have to be higher, over 30m (100ft), if it was to survive the cruel waves of the North Sea. He also incorporated more efficient reflectors, using the latest oil lighting technology, which would make his beacon the brightest yet seen.

But the Northern Lighthouse Board rejected the plan outright; in their eyes Stevenson was attempting the impossible, and besides, it was going to cost the huge sum of £42,685 and 8 shillings.

The rock had to claim another victim before the Board revisited Stevenson's plans. In 1804 the huge 64-gun HMS York was ripped apart on the rock, with the loss of all 491 crew. The NLB could delay no longer. Britain's most eminent engineer, John Rennie, was invited to give his advice.

Rennie had never actually built a lighthouse, but the Board was so impressed by his record that he was given the job of chief engineer. Robert Stevenson was to work as his resident engineer.

History does not record Stevenson's reaction to the news, but it must have come as a bitter blow to this ambitious young man. What history does record is that the structure on Bell Rock came to be known not as Rennie's but as Stevenson's Lighthouse.

Work started in 1807 and what followed was a four-year epic, with work severely restricted by tides that on occasion submerged the rock’s surface to twelve feet. The offshore activity only proceed during the summer months, and even then only with difficulty. Poor weather in the summer of 1808 allowed only 80 hours of work were completed.

To avoid time lost in shuttling workers to and fro Stevenson built a temporary wooden “Beacon House” on the rock and this served as both a base of operations and living quarters for fifteen men. As this structure (see illustrations) was also exposed to storms during the construction period, residence on it must have in itself have been a nightmare. During the winter months Stevenson kept his crews busy ashore, dressing the individual granite blocks needed for the tower. The total number required was some 2500 and all were drawn to the dockside by one of the unsung heroes of the project, a horse called Bassey.

The lighthouse came into service in 1810 and was to fulfil its purpose very effectively. Between then and 1914 only a single ship was lost on the rock, a steamer called the Rosecraig that ran aground during a fog in 1908, fortunately without loss of life.

The light has now operated for 212 years and has undergone many significant and ingenious upgrades and changes, some of them even being undertaken by non-Stevenson engineers. It was a manned light for 177 years, the lives of those keepers on their temporary Alcatraz being a source of equal fascination

The lighthouse was manned until 1988, when the station turned automatic and the last men were withdrawn.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

A light on a reef

Until the end of the 17th century one of the threats facing shipping heading to Plymouth on the southern coast of England was the isolated and treacherous Eddystone reef, 23km directly offshore. Much of the hazard is underwater, creating complex currents, and extraordinarily high seas are often kicked up when conditions are very windy. In 1620 Captain Christopher Jones, master of Mayflower described the reef: "Twenty-three rust red [...] ragged stones around which the sea constantly eddies, a great danger [...] for if any vessel makes too far to the south [...] she will be swept to her doom on these evil rocks." As trade with America increased during the 1600s a growing number of ships approaching the English Channel from the west were wrecked on the Eddystone reef.

King William III and Queen Mary were petitioned that something be done about marking the infamous hazard. Plan to erect a warning light by funding the project with a penny a ton charge on all vessels passing initially foundered. Then an enterprising character called Henry Winstanley stepped forward and took on the most adventurous marine construction job the world had ever seen. Work commenced on the mainly wooden structure in July 1696. England was again at war, and such was the importance of the project that the Admiralty provided a man-o-war for protection.

The Winstanley Lighthouse, by English School, 17th century (x)

On one day, however, HMS Terrible did not arrive and a passing French privateer seized Winstanley and carried him off to France. When Louis XIV heard of the incident he ordered his release. " France is at war with England, not humanity," said the King. Winstanley's was the first lighthouse to be built in the open sea. It was a true feat of human endeavour. Work could only be undertaken in summer and for the first two years nothing could be left on the rock or it would be swept away. There was some assistance from Terrible in transporting the building materials, but much had to be rowed out in an open four-oared boat in a journey that could take nine hours each way. Winstanley's lighthouse was swept away after less that five years, during the great storm of 1703.

John Rudyerd's wooden lighthouse of 1708, by Issac Sailmaker, c. 1708 (x)

Winstanley was in it at the time supervising some repairs- he had said that he wished to be there during " the greatest storm that ever was." The next lighthouse was built by John Rudyerd and lit in 1709. Also made largely of timber and with granite ballast, it gave good service for nearly half a century until destroyed by fire in 1755. During the blaze the lead cupola began to melt, and as the duty keeper, 94- old Henry Hall, was throwing water upwards from a bucket he accidentally swallowed 200g of the molten metal. No one believed his incredible tale, but when he died 12 days later doctors found a lump of lead in his stomach.

Smeaton's Eddystone Lighthouse, by John Lynn (active 1826-1869) (x)

John Smeaton, Britian's first great civil engineer, was the next to rise to the challenge of Eddystone. He took the English oak as his design inspiration - a broad base narrowing in a gentle curve. The 22m high lighthouse was built using solid discs of stone dovetailed together. Work began in 1756, and from start to finish the work took three years, nine weeks and three days. Small boats transported nearly 1000 tons of granite and Portland stone along with all the equipment and men.

Sir James N. Douglass's Eddystone Lighthouse, Plymouth, England, photochrome print, c. 1890–1900. The remnants of John Smeaton's lighthouse are at left. (x)

The Smeaton lighthouse stood for over 100 years. In the end it was not the lighthouse that failed; rather that the sea was found to have eaten away the rock beneath the structure. In 1882 it was dismantled and brought back to Plymouth, where it was re-erected stone on the Hoe as a memorial, and where it still stands.

The Eddystone lighthouse today (x)

It had already been replaced by a new lighthouse, twice as tall and four and a half times as large, designed by James Douglas, which now gives mariners a beacon of light visible for 22 nautical miles (40,78km).

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792)

While he may be known as the father of civil engineering, John Smeaton simultaneously made significant strides in the field of materials science and engineering as well. An English engineer, he experimented with building materials, pioneering the use of hydraulic lime in cement. While cement and concrete long predate Smeaton, they fell out of use in Europe after the Roman empire. Smeaton is credited as the one to revitalize their usage, also earning him the title of the father of modern concrete. While he didn't invent Portland cement, created after Smeaton's death in the 1820s, his research and own "Roman cement" laid the groundwork for its discovery and the future of concrete.

Sources/Further Reading: (Image source - Wikipedia) (Popular Mechanics) (Science Museum) (My Learning) (History 1700s)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was going to make a longer post about it but I'll summarise.

Areas of agreement between Wolsey, Cromwell AND More:

1) Peace is more advantageous than war*

2) Renaissance humanism is good. Humanist scholarship deserves patronage

3) More preaching please. And expand education.

4) Enclosures are bad for the poor. Limit the practice as much as possible.

5) You can use violence to intimidate the vulnerable into saying what you want them to say. If not by actual torture, then certainly corporal punishment.**

6) Execute religious dissidents. Burning heretics is OK.***

7) It would be good for people to have an English bible.****

8) The justice system is a complex mess that needs reforming so ordinary people can better access justice for their suits.

*this policy is different to the wishes of young noblemen who want military glory

**Case in point: Richard Purser, Mark Smeaton, "prick him with pains".

*** The area of disagreement here is not "is burning heretics OK?" but "what is heresy and what isn't?" Case in point: Wolsey appointing More to the heresy commission, recommending More as his successor, and the John Lambert case of 1538.

****The disagreement is NOT "would people benefit from a vernacular Bible?" But "how would this bible be translated and who should translate it?"

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Let no one deceive you with empty words, for because of these things the wrath of God comes upon the sons of disobedience.” Ephesians 5:6

“Some people like to think that although the wrath of God is a reality in the Old Testament era, it disappears in the teaching of Jesus, where God’s love and mercy become the only expressions of his attitude toward his creatures. Jesus clearly refuted that notion: "Whoever rejects the Son will not see life, for God’s wrath remains on him" (John 3:36, NIV). And he frequently referred to hell as the ultimate, eternal expression of God’s wrath. (See, for example, Matthew 5:22; 18:9; Mark 9:47; Luke 12:5.)

In the inspired letters of Paul, we read of God’s wrath being "stored up" for the day of judgment (Romans 2:5) and that God’s wrath is coming because of sin (Colossians 3:6). And the whole tenor of Revelation warns us of the wrath to come.

Having then established the grim reality of God’s wrath, how are we to understand it? God’s wrath arises from his intense, settled hatred of all sin and is the tangible expression of his inflexible determination to punish it. We might say God’s wrath is his justice in action, rendering to everyone his just due, which, because of our sin, is always judgment.

Why is God so angry because of our sin? Because our sin, regardless of how small or insignificant it may seem to us, is essentially an assault on his infinite majesty and sovereign authority. As nineteenth-century theologian George Smeaton wrote, God is angry at sin "because it is a violation of his authority, and a wrong to his inviolable majesty."

Here we begin to realize the seriousness of sin. All sin is rebellion against God’s authority, a despising of his law, and a defiance of his commands.”

~ Jerry Bridges

“Put to death therefore what is earthly in you: sexual immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry. On account of these the wrath of God is coming. In these you too once walked, when you were living in them. But now you must put them all away: anger, wrath, malice, slander, and obscene talk from your mouth. Do not lie to one another, seeing that you have put off the old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator.” Colossians 3:5-10

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The party that pushed forward Jane Seymour remains rather obscure, in part because the main beneficiary of Jane's rise was her brother Edward, a man of too little influence in 1536 to have engineered Anne's destruction alone. It seems probable that the real leaders of the faction seeking to topple the Boleyns were second-ranking political figures at court.

The leading figure in terms of status was Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter, a man of high rank and noble blood but rather slim power at court. Exeter's main goal in replacing Anne with Jane Seymour seems to have been to restore Mary to the succession and halt the religious progressivism the 'Lutheran' Boleyns represented.

A less prestigious, but actually more powerful, member of the group was Nicholas Carew, Master of the Horse, a household official and royal companion. Carew was particularly angry with the Boleyns because Anne had persuaded Henry to select her brother George for a recent vacancy in the Order of the Garter which Carew coveted. He was supported by Anthony Browne, Thomas Cheney, and John Russell, all Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber.

The importance of the locus of the conspiracy is shown by the status of the men destroyed with Anne, all of them (save her brother and Mark Smeaton) members of Henry's househod.

The Life of Thomas Howard, Third Duke of Norfolk (1995)

#and two of them dead within three years...woof#also i thought george didn't receive that vacancy...? he was thought to be the candidate for it which is maybe what he's getting at here.#idk...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

MODERN HISTORY

2. The Industrial Revolution (18th century - 19th century)

The Industrial Revolution was a period of rapid economic, social, and technological change that took place in Europe and North America between the 18th and 19th centuries. These changes had a significant impact on water use, as the industry required large amounts of water for its processes.

The importance of the Industrial Revolution to contemporary water conservation problems is that it established a precedent for the intensive use of water by industry. The water conservation challenges we face today, such as water scarcity and water pollution, are related to the intensive use of water by industry.

The Industrial Revolution began in England in the second half of the 18th century. It was characterized by the development of new technologies, such as the steam engine, which allowed the mass production of goods. The textile industry was one of the first sectors to adopt these new technologies, and soon became a large consumer of water.

The industry's intensive use of water spread to other sectors, such as mining, steel production, and paper production. Demand for water increased rapidly, straining the water resources of many regions.

One of the earliest advocates of water conservation during this historic event was civil engineer John Smeaton, who in 1758 published a report on the pollution of the River Thames in London.

In 1863, the British government established the Royal Commission on Drinking Waters, which investigated the state of drinking water in the United Kingdom. The commission recommended a series of measures to improve water quality, including building wastewater treatment plants and regulating the discharge of industrial pollutants.

In the United States, the water conservation movement was led by civil engineer Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted was an advocate for the preservation of natural resources, and believed that water conservation was essential to sustainable development.

The Industrial Revolution had a number of results on water conservation practices and policies. First, urban population growth and industrialization increased the demand for water. This led to the construction of new water supply and sewage systems, which were often inefficient and polluting.

Secondly, the Industrial Revolution led to water pollution. Industrial and domestic waste was dumped into rivers and lakes, contaminating the water and endangering public health.

In response to these actions during the Industrial Revolution, a series of advances in water conservation occurred. These advances included:

• The construction of wastewater treatment plants to improve water quality.

• Regulating the discharge of industrial pollutants to reduce water pollution.

• The development of efficient irrigation technologies to reduce water consumption in agriculture.

Thanks to these advances, the environmental impacts of the industry's intensive use of water were mitigated.

Today, the challenges and opportunities of water conservation remain the same as in the 19th century. Water pollution, increasing water demand and the need to protect aquatic ecosystems remain major issues.

The Industrial Revolution taught us that sustainable water management is essential for economic and social development. The technological and social advances that took place during this period provide us with the necessary tools to meet the current challenges of water conservation.

In short, the Industrial Revolution marked a turning point in the history of water conservation since this period marked the beginning of a new era in water use, characterized by an increase in consumption and a degradation in quality. These changes posed new challenges for sustainable water management; challenges that remain valid today.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Review of “Seashaken Houses”

As a teenager in the 90s, I was interested in lighthouses, and visited a couple (Hook Head and Mew Island) before they were automated. I think what I found appealing was the 19th Century technology, the neatness and definiteness of the constructions. Lighthouses are popular with the public for their ‘nautical gaiety’, although, as workplaces, they are solemn. If I had been in America, I might have studied NASA rockets instead. Irish lighthouses represented a relatively accessible, if anachronistic, form of high tech. So I think, when I read about them, that I was after a shot of technology, precision and good order, not gaiety. Looking back, I wonder now whether I was completely immune, though, to the main appeal of lighthouses, which is their civility. This quality is sometimes emphasized by wild surroundings, but it doesn’t have to be. The politeness and formality of a lighthouse stands out in any setting. In black and white photographs and section drawings, from old illustrated books, their solidity and precision appealed to something in my personality.

I’ve moved on from my lighthouse enthusiasm, but recently picked up Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet by Tom Nancollas. It’s an interesting book to me for a few reasons. Nancollas works in building conservation. He is a graduate in classical studies and a self-described antiquary: though in his mid 30s, he uses the letters FSA after his name. It will come as no surprise that he is a bit of a young fogey. The book is a selective history of the rock lighthouses of these islands from the perspective, primarily, of architectural history.

The first thing to note is that focusing on rock lighthouses is a bit like focusing on express locomotives or thoroughbred horses. These buildings form an elite category among lighthouses. Even more than the typical lighthouse, they are high-end engineering projects, on which money, attention, and craftsmanship was lavished. The first wave-washed towers were civil engineering marvels. As such, they are compatible with the values of the ancien régime: the marvellous rather than the uniform. Every rock lighthouse is a bespoke item, a custom job, consisting of thousands of precisely tailored stone blocks, dovetailed into the bedrock. These towers are notable for their symmetry and crystalline order.

After a couple of freakish and inadequate attempts which lasted only a few years, the design of rock lighthouses settled into a pattern. The archetype was the third Eddystone lighthouse, designed by John Smeaton. Constructed of granite blocks, it was a tapering circular tower with a lantern at the top. Smeaton’s tower established the compelling architectural image of a hollow, inhabited pinnacle of rock, almost completely unadorned. The development of a new building type is the most exciting event in architecture. It is to the representatives of this once new genre of tower that Nancollas devotes his book: Eddystone, Bell Rock, Haulbowline, Perch Rock, Wolf Rock, Eddystone (again), Bishop Rock, Fastnet.

As an antiquary, Nancollas comes to his subject with somewhat vague qualifications. He knows a bit about architectural history, though he is not an architect. He has a taste for authentic idioms, though he doesn’t pick up some of the most distinctive lighthouse terminology—wave-washed, for example. He is neither an engineer nor a seaman. People who like the book seem not to object to the gentlemanliness of his project. He is a personable narrator, and people seem inclined to entertain his pretensions to history writing, particularly the insinuation of his own experiences into the story. Though he can come across as a bit privileged, it would be a trap to conclude that due to having been well brought-up he must be an upper-class twit. He is temperamentally suited to recording what defines lighthouses from an architectural point of view: their civility, their good form.

So the book, even if it is, in truth, less a passion project than a vehicle for Nancollas’ writerly ambitions, is successful. He covers all the bases, as far as the architectural history of the buildings goes. I am not sure than he is so strong on placing the wave-washed towers into context. They exemplify the endlessly mysterious dictum “form follows function”. Nancollas doesn’t mention the slogan, and I don’t think he would perceive it as a mystery, so much as a glib banality.

The towers were machines and participants in a proliferating network of signalling and navigation. Cooped up inside, the keepers led dreary lives of unrelenting solitude, slaves to the machinery. What is missing in this world of duty and responsibility is a sense of exuberance or expansiveness. The engineering of any one of these towers may have been a virtuoso performance, but occupying them was not. Physically restricted to a small compass, the keepers could scarcely give free rein to any aspect of their personality, while, outside, the ungovernable sea did its own thing, day and night.

As a teenager I read, in a book about Scottish lighthouses, about a keeper who was studying mathematics in the evenings. This fact seemed resonant and stayed with me. In addition to possessing the circular symmetry of most lighthouses, the wave-washed towers reflect a complex, orderly process of assembly. The premeditated, scripted sequence of operations was a way to guarantee the unshakable soundness of the towers. This is a property which it shares with the 19th Century development of mathematical formalisms, intended to place mathematical proof on an unassailable foundation. But there is a more psychological relevance of mathematics to the life of a lighthouse keeper. Mathematics—reason’s dream—is a mental practice of domination, of control. The mathematician is always the wrangler, never the subdued, always the buttoner-up, never the buttonee. It is a form of agency which is available even in the most isolated and confined quarters, when one is “bounded in a nutshell”.

A preoccupation with fallibility infuses the whole operation of lighthouses. In the 1850s Michael Faraday remarked that “There is no human arrangement that requires more regularity and certainty of service than a lighthouse.” The seriousness of the task in hand justifies the omission of ornament. Foibles and fripperies are excluded. But from the architectural historian’s perspective, the 19th C towers still have some traces of politeness, some flourishes, some relics of old decency. Looking at them, it is easy to understand the spirit of Horatio Greenough’s statement—“In nakedness I behold the majesty of the essential instead of the trappings of pretension”. The order of the day is structural necessity, not ornamental contingency, forms that relate to the job of exhibiting a light high above the water rather than extemporized curlicues. In that sense, the towers obey the modernist logic of form following function. The philosophy of their design is an appeal to “fixed and unchangeable laws” and a dismissal of “eccentric opinions” (Laugier). It is an ambiguous perfection.

Nancollas doesn’t seem to appreciate the notion of modernism in this sense. He doesn’t use the term in a positive sense, except to remark, bizarrely, that an Irish Lights helicopter looks “reassuringly modern and functional”.

The structural integrity of the towers visited by the narrator is a prerequisite for the continuity of the service they provide. It is just one aspect of their reliability. In gentlemanly style, Nancollas suppresses the technicalities of the lights’ construction and operation. For example, he seems unaware that an ellipse has two unequal axes, and thus mangles a description of the geometrical definition of the shape of Wolf Rock’s tower. Lamenting the modernization of Bell Rock, he claims “it requires only a little ingenuity to let the old coexist with the new, even offshore.“ There is a risk, in avoiding technicalities, that the achievement becomes indistinct and dull, the account facile.

In the early days of mass production, the perfect precision of a machine’s construction was understood to mean perpetual reliability. We are less inclined to make this connection now—the possibility of human error in manufacturing has receded as a cause of failures, replaced by more exotic problems due to complexity and economic constraints. Little expense was spared in the construction of the rock lighthouses, and their designers were cautious and conservative in their technical specifications. It’s clear that this quality is part of their particular appeal. Studies suggest that the towers have a good chance of surviving future rough seas, even with climate change. They have become monuments.

Less appealing is the human story of their inhabitants. Nancollas remarks of the Bell Rock lighthouse: “The tower is painted a pure white, blotched in places by liquids cast from the windows (probably coffee and urine, from the time when it was inhabited), smoke damage (from a fire in the 1980s), and a big streak of green-black wave-spatter on one side.” A dour, dangerous life. Automation was a relief. Let these obdurate things enjoy the solitary life that suits them.

Nancollas has a bit more personality than the topic of his book suggests. Alcohol and nicotine are part of his stories; there is a slight loucheness that goes along with the fogeyishness, for better or worse. When smells are mentioned they tend to be repellent rather than sweet. He is more-or-less oblivious to politics; where he could espouse a firm position on the Troubles he prefers to tell a conciliatory story. Despite visiting two Irish lighthouses, he apparently manages to miss the fact that Irish Lights is a cross-border body. Rather than sticking to the facts, his writing involves a certain amount of self-indulgence. His style is unbuttoned and a little verbose, sometimes drifting into grandiloquence—but then, I’m not his target audience. The style does, however, seem unsuited to the plain subject matter. It leaves me expecting to see something more decorative, perhaps more feminine. That is what his language promises. The radical uncosiness and stern splendour of the lighthouses evokes the emotionally toxic, a characteristic not to be dwelled on.

The chief fault of Nancollas' book, though, is his airy indifference to science and technology. This is all too predictable, coming as it does from a classicist and a conservationist. The spirit of modernity, of systems and methodical processes, seems to have passed him by, along with the World Wars. He is enviably untroubled by the imperatives of keeping technology running. When he alludes to such processes, it is in dismissive terms: the daily routine of preparing the light is like "solving a Rubik's cube"; the technician's job of disassembling and reassembling a generator is a “puzzle". Nancollas doesn’t articulate the modernist metanarrative—the idea that a single correct solution can be derived quasi-mathematically from the statement of the problem, and that if the designer gets it right it will last forever. He doesn’t place the complex and demanding process of the masonry construction of the towers in the context of development toward digital technology, of carefully designed units assembled into reliable machinery. A basic premise of studying the classics is that human nature doesn’t change—that there is nothing new under the sun. But society and culture do change and new technologies bring radically new experiences. The rock lighthouses are of their time, redundant now. Nancollas doesn’t address the question of how to value this old hardware in the context of our new software. For him, it is yet another “puzzle”. New illumination technologies have made the flashing lights of navigational aids more abrupt, less gradual, an example of the kind of creeping qualitative change and dilution of historic character that makes conservationists despair.

0 notes

Photo

Smeaton’s Bridge

#Smeaton's bridge#john smeaton#smeaton#perth#perthshire#scotland#canon#70d#canon 70d#tim dennis.tumblr#tim dennis#fade#graduated merge#merge to black and white#panorama#photomerge#Black and White#b&w#pws - photos worth seeing#pws#original photographers#lensblr#bridge#river#river tay#water#colour#color#architecture#landscape

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sixtended OC's Height Chart

I think this was long overdue. This is a height chart to all of the current Sixtended Verse OCs on Tumblr. I will update once new ones are made. I did both types just in case. Updated (July 30, 2024)

I like to thank @altairtalisman for the chart I used as a reference and both them and Finch for the help

Amalia “Mali” by @pandora-dusk - 5'3ft or 160.02cm (160)

Anne “Anya” by @toasty-owl-arts - 5'2ft or 157.48cm (157.5)

Anne “Ann” by yours truly - 5'8ft or 172.72cm (172.7)

Arthur Tudor by @djts-arts - 6′2ft or 187.96cm (188)

Cathryn Carey by @weirdbutdecentart - 5'1 or 154.94cm (154.9)

Christina of Denmark by @the-fox-arts - 5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Dorothy"Roth" by @altairtalisman - 5'4ft or 162.56cm(162.6)

Edward VI by @ratscraftz -5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Elisabeth "Sisi" by @ratscraftz - 5'6ft or 167.64cm(167.6)

Elizabeth "EB" by @spooner7308 - 5'11ft or 180.34cm (180.3)

Elizabeth ‘Liz’ Seymour by @vancsssa - 5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Elizabeth “Ellie” Tudor by @me-tizi - currently 4′3ft or 129.54cm (129.5), but will be 5′4ft or 162.56cm (162.6)

Ferdinand II by @weirdbutdecentart - 6'3ft or 190.5cm

George Boleyn by @ellielovesdrawing - 6'4ft or 193.04cm (193)

Guilford Dudley by @ratscraftz 5'8ft or 172.72cm (172.7)

Hans Holbein the Younger by @podsn - 6′0ft or 182.88cm (182.9)

Hans Holbein the Younger by @redlover411 - 5’9ft or 175.26cm (175.3)

Henry Carey by @weirdbutdecentart - 5'0ft or 152.4cm

Henry “Hal” by @blackdiamondwrites127 - currently growing, but will be 6'2ft or 187.96cm (188)

Henry "Fitz" FitzRoy by @maths-is-my-religion - 5'11ft or 180.34cm (180.3)

Henry Percy by @cheemken - 6'3ft or 190.5cm

Isabella of Castille by @weirdbutdecentart - 6'2ft or 187.96cm (188)

Isabella Trastamara by @lexartsstuff - 5'5ft or 165.1cm

Isabella “Izzi” Trastàmara by @weirdbutdecentart - 3'7ft or 109.22cm (109.2)

Jane "Janey" Grey by @ratscraftz - 5'1ft or 154.94cm (154.9)

Jane “JP” by @altairtalisman - 5'8ft or 172.72cm (172.7)

John Astley by @yourdeepestfathoms - 6′0ft or 182.88cm (182.9)

Juan Trastàmara by @weirdbutdecentart - 6'1ft or 185.42cm (185.4)

Juana “Ju-Ju” by @ellielovesdrawing - 5'11ft or 180.34cm (180.3)

Katherine “Kat” Ashley by @yourdeepestfathoms - 5'11ft or 180.34cm (180.3)

Katherine “Kath” Tudor by @ellielovesdrawing - 5'0ft or 152.4cm

Lillia "Lily" Trastamara by @ellielovesdrawing - currently 4'11ft or 149.86cm (149.9), but will be 5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Margaret “Maggie” of Austria by @weirdbutdecentart - 6'0ft or 182.88cm (182.9)

Margaret Beaufort by @redladydeath - 5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Margaret “Meg” by @me-tizi - 5′8ft or 172.72cm (172.7)

Maria of Jülich-Berg by @blackdiamondwrites127 - 5'1ft or 154.94cm (154.9)

Maria Trastámara by @blackdiamondwrites127 - 5′7ft or 170.18cm (170.2)

Marion Trastámara by @vancsssa - 5'2ft or 157.48cm (157.5)

Mark Smeaton by @ellielovesdrawing - 6'1ft or 185.42cm (185.4)

Mary “Mara” Boleyn by @mariegreythepoet - 5′6ft or 167.64cm (167.6)

Mary Fitzroy-Howard by @maths-is-my-religion - 5′3ft or 160.02cm (160)

Mary Stuart by @to-the-world-we-dream-about - 6′0ft or 182.88cm (182.9)

Mary “Marie” by @me-tizi - 5′5ft or 165.1cm

Mary I "Mari" by @crimsonnight186 - 5'9ft or 175.26cm (175.3)

Robert Dudley by @ratscraftz 5'9ft or 175.26cm (175.3)

Sibylle of Cleves by @blackdiamondwrites127 - 6′4ft or 193.04cm (193)

Thomas More by @spooner7308 - 5′6ft or 167.64cm (167.6)

William of Jürich-Cleves-Berg by @lexartsstuff - 6′0ft or 182.88cm (182.9)

Will Parr by @weirdbutdecentart - 6'1ft or 185.42cm (185.4)

Willie Strafford by @weirdbutdecentart - 5'9ft or 175.26cm (175.3)

#six the musical#Six OC#Sixtended verse#Amalia of Cleves#Anya Askew#Ann Parr#Arthur Tudor#Christina of Denmark#Elizabeth Barton#Elizabeth Seymour#Elizabeth Tudor#George Boleyn#Hal Aragon#Hans Holbein#Henry Percy#Isabella Trastamara#Jane Parker#John Astley#Juana de Castille#Katherine Ashley#Katherine Tudor#Margaret Beaufort#Margaret Tudor#Mary Boleyn#Mary Fitzroy-Howard#Mary Stuart#Maria Trastamara#Mark Smeaton#Mary Tudor#Sibylle of Cleves

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Smeaton Kimdir 8 Haziran 1724 yılında İngiltere’de Austhorpe, Leeds’de doğmuş olan John Smeaton önce bilimsel araç gereç yapımıyla başlamış, sonra aralarında İskoçya’da Forth ve Clyde nehirlerini birleştiren kanal (1790) olmak üzere büyük yapılar inşa etmiştir.

0 notes

Text

i’m bored so here are the magnus locations i have been to/ been within a few minutes of in the case of like specific streets etc

- birmingham new street/ station where Masato Murray died (MAG70)

- smeatons pier/ beach where Enrique MacMillian found the Leitner (MAG88)

- bootle/ town where Leanne Denikin lived (MAG24)

- lost johns cave/ cave where Laura Popham and Alena Sanderson were trapped (MAG15)

- aberdeen/ city where Ross Davenport lived (MAG90)

- charlestown MA/ town where Nathaniel Thorp gambled with Death (MAG29)

- portsmouth/ city where Vincent Yang was held captive by Mikaele Salesa (MAG66)

#txt#i havent actually been inside lost johns cave bc its pretty deep in the cave complex but ive been in the cave its a part of#smeatons pier and birmingham new street are the worst bc like. i was at that very specific location rather than just. the same city#idk i was just interested#i will have been to the town from we all ignore the pit in a few weeks too!!

12 notes

·

View notes