#Jurisprudenz

Text

-weise und wegweisend!

Die Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft ist -weise und wegweisend, sie weiß -weise und visuell. Das heißt nicht unbedingt sichtbar, das ist das etwas durch das Wissen zieht, vis, und das Wissen teilweise wahrnehmbar macht, immer nur -weise. Versteht man Sichtbarkeit als teilweise Sichtbares, als Chance und Kanzel dessen, was zu sehen sein soll, dann ist Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft sichtbar. Man kann sie sichten, man kann sie richten, ein- und ausrichten, immer und durchgehend -weise. Wer hat's erfunden? Vismann.

Sie ist phasenweise, stellenweise, fallweise, glücksweise und beispielsweise. Es gibt nichts Gesetzesweises, entweder ist etwas legal oder illegal, entweder ist etwas ein Gesetz oder kein Gesetz. Das Gesetz ist ganz oder gar nicht, das ist nicht phasenweise, stellenweise, fallweise oder glücksweise Gesetz. Das Gesetz ist abstrakt und allgemein.

Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft ist nicht das Gesetz und nicht wie das Gesetz. Sie ist -weise und wegweisend. Ein älterer Name für sie ist Jurisprudenz. Ein älteres Bild ist die prudentia bifrons, eine, die dabei ist und immer nur bei bei sagt, falls wir das ausnahmsweise einmal richtig verstanden haben, sie nuschelt und nöselt so.

1 note

·

View note

Text

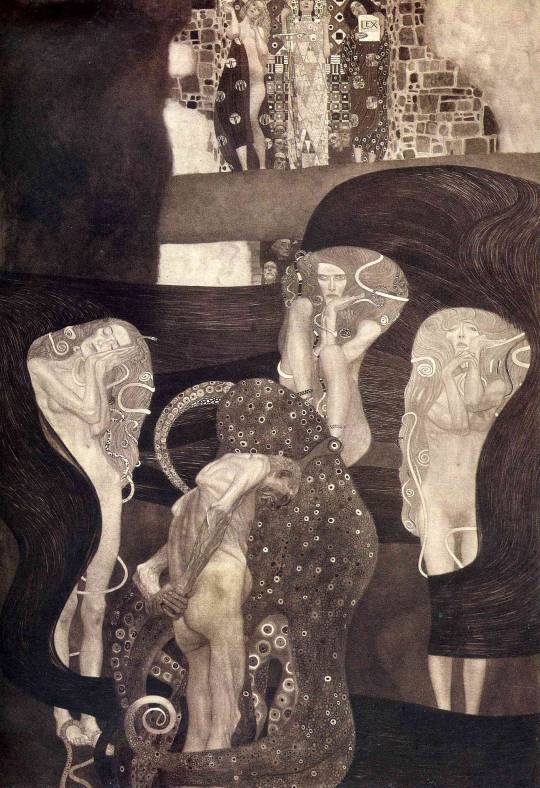

Gustav Klimt

Jurisprudenz (1903-1907)

Destroyed in a 1945 fire at Immendorf Castle

#Wiener Secession#Secessionsstil#Wiener jugendstil#jugendstil#gustav klimt#painting#lost painting#oil painting#oil on canvas#art#fine art#art history#artist#austrian art#sezessionsstil

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Footnotes, 151 - 200

[151] See Post, Afrikanische Jurisprudenz, Oldenburg, 1887. Münzinger, Ueber das Recht und Sitten der Bogos, Winterthur” 1859; Casalis, Les Bassoutos, Paris, 1859; Maclean, Kafir Laws and Customs, Mount Coke, 1858, etc.

[152] Waitz, iii. 423 seq.

[153] Post’s Studien zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Familien Rechts Oldenburg, 1889, pp. 270 seq.

[154] Powell, Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnography, Washington, 1881, quoted in Post’s Studien, p. 290; Bastian’s Inselgruppen in Oceanien, 1883, p. 88.

[155] De Stuers, quoted by Waitz, v. 141.

[156] W. Arnold, in his Wanderungen und Ansiedelungen der deutschen Stämme, p. 431, even maintains that one-half of the now arable area in middle Germany must have been reclaimed from the sixth to the ninth century. Nitzsch (Geschichte des deutschen Volkes, Leipzig, 1883, vol. i.) shares the same opinion.

[157] Leo and Botta, Histoire d’Italie, French edition, 1844, t. i., p. 37.

[158] The composition for the stealing of a simple knife was 15 solidii and of the iron parts of a mill, 45 solidii (See on this subject Lamprecht’s Wirthschaft und Recht der Franken in Raumer’s Historisches Taschenbuch, 1883, p. 52.) According to the Riparian law, the sword, the spear, and the iron armor of a warrior attained the value of at least twenty-five cows, or two years of a freeman’s labor. A cuirass alone was valued in the Salic law (Desmichels, quoted by Michelet) at as much as thirty-six bushels of wheat.

[159] The chief wealth of the chieftains, for a long time, was in their personal domains peopled partly with prisoner slaves, but chiefly in the above way. On the origin of property see Inama Sternegg’s Die Ausbildung der grossen Grundherrschaften in Deutschland, in Schmoller’s Forschungen, Bd. I., 1878; F. Dahn’s Urgeschichte der germanischen und romanischen Völker, Berlin, 1881; Maurer’s Dorfverfassung; Guizot’s Essais sur l’histoire de France; Maine’s Village Community; Botta’s Histoire d’Italie; Seebohm, Vinogradov, J. R. Green, etc.

[160] See Sir Henry Maine’s International Law, London, 1888.

[161] Ancient Laws of Ireland, Introduction; E. Nys, Études de droit international, t. i., 1896, pp. 86 seq. Among the Ossetes the arbiters from three oldest villages enjoy a special reputation (M. Kovalevsky’s Modern Custom and Old Law, Moscow, 1886, ii. 217, Russian).

[162] It is permissible to think that this conception (related to the conception of tanistry) played an important part in the life of the period; but research has not yet been directed that way.

[163] It was distinctly stated in the charter of St. Quentin of the year 1002 that the ransom for houses which had to be demolished for crimes went for the city walls. The same destination was given to the Ungeld in German cities. At Pskov the cathedral was the bank for the fines, and from this fund money was taken for the wails.

[164] Sohm, Fränkische Rechts- und Gerichtsverfassung, p. 23; also Nitzsch, Geschechte des deutschen Volkes, i. 78.

[165] See the excellent remarks on this subject in Augustin Thierry’s Lettres sur l’histoire de France. 7th Letter. The barbarian translations of parts of the Bible are extremely instructive on this point.

[166] Thirty-six times more than a noble, according to the Anglo-Saxon law. In the code of Rothari the slaying of a king is, however, punished by death; but (apart from Roman influence) this new disposition was introduced (in 646) in the Lombardian law — as remarked by Leo and Botta — to cover the king from blood revenge. The king being at that time the executioner of his own sentences (as the tribe formerly was of its own sentences), he had to be protected by a special disposition, the more so as several Lombardian kings before Rothari had been slain in succession (Leo and Botta, l.c., i. 66–90).

[167] Kaufmann, Deutsche Geschichte, Bd. I. “Die Germanen der Urzeit,” p. 133.

[168] Dr. F. Dahn, Urgeschichte der germanischen und romanischen Völker, Berlin, 1881, Bd. I. 96.

[169] If I thus follow the views long since advocated by Maurer (Geschichte der Städteverfassung in Deutschland, Erlangen, 1869), it is because he has fully proved the uninterrupted evolution from the village community to the medieval city, and that his views alone can explain the universality of the communal movement. Savigny and Eichhorn and their followers have certainly proved that the traditions of the Roman municipia had never totally disappeared. But they took no account of the village community period which the barbarians lived through before they had any cities. The fact is, that whenever mankind made a new start in civilization, in Greece, Rome, or middle Europe, it passed through the same stages — the tribe, the village community, the free city, the state — each one naturally evolving out of the preceding stage. Of course, the experience of each preceding civilization was never lost. Greece (itself influenced by Eastern civilizations) influenced Rome, and Rome influenced our civilization; but each of them begin from the same beginning — the tribe. And just as we cannot say that our states are continuations of the Roman state, so also can we not say that the mediæval cities of Europe (including Scandinavia and Russia) were a continuation of the Roman cities. They were a continuation of the barbarian village community, influenced to a certain extent by the traditions of the Roman towns.

[170] M. Kovalevsky, Modern Customs and Ancient Laws of Russia (Ilchester Lectures, London, 1891, Lecture 4).

[171] A considerable amount of research had to be done before this character of the so-called udyelnyi period was properly established by the works of Byelaeff (Tales from Russian History), Kostomaroff (The Beginnings of Autocracy in Russia), and especially Professor Sergievich (The Vyeche and the Prince). The English reader may find some information about this period in the just-named work of M. Kovalevsky, in Rambaud’s History of Russia, and, in a short summary, in the article “Russia” of the last edition of Chambers’s Encyclopædia.

[172] Ferrari, Histoire des révolutions d’Italie, i. 257; Kallsen, Die deutschen Städte im Mittelalter, Bd. I. (Halle, 1891).

[173] See the excellent remarks of Mr. G.L. Gomme as regards the folkmote of London (The Literature of Local Institutions, London, 1886, p. 76). It must, however, be remarked that in royal cities the folkmote never attained the independence which it assumed elsewhere. It is even certain that Moscow and Paris were chosen by the kings and the Church as the cradles of the future royal authority in the State, because they did not possess the tradition of folkmotes accustomed to act as sovereign in all matters.

[174] A. Luchaire, Les Communes françaises; also Kluckohn, Geschichte des Gottesfrieden, 1857. L. Sémichon (La paix et la trève de Dieu, 2 vols., Paris, 1869) has tried to represent the communal movement as issued from that institution. In reality, the treuga Dei, like the league started under Louis le Gros for the defense against both the robberies of the nobles and the Norman invasions, was a thoroughly popular movement. The only historian who mentions this last league — that is, Vitalis — describes it as a “popular community” (“Considérations sur l’histoire de France,” in vol. iv. of Aug. Thierry’s Œuvres, Paris, 1868, p. 191 and note).

[175] Ferrari, i. 152, 263, etc.

[176] Perrens, Histoire de Florence, i. 188; Ferrari, l.c., i. 283.

[177] Aug. Thierry, Essai sur l’histoire du Tiers État, Paris, 1875, p. 414, note.

[178] F. Rocquain, “La Renaissance au XIIe siècle,” in Études sur l’histoire de France, Paris, 1875, pp. 55–117.

[179] N. Kostomaroff, “The Rationalists of the Twelfth Century,” in his Monographies and Researches (Russian).

[180] Very interesting facts relative to the universality of guilds will be found in “Two Thousand Years of Guild Life,” by Rev. J. M. Lambert, Hull, 1891. On the Georgian amkari, see S. Eghiazarov, Gorodskiye Tsekhi (“Organization of Transcaucasian Amkari”), in Memoirs of the Caucasian Geographical Society, xiv. 2, 1891.

[181] J.D. Wunderer’s “Reisebericht” in Fichard’s Frankfurter Archiv, ii. 245; quoted by Janssen, Geschichte des deutschen Volkes, i. 355.

[182] Dr. Leonard Ennen, Der Dom zu Köln, Historische Einleitung, Köln, 1871, pp. 46, 50.

[183] See previous chapter.

[184] Kofod Ancher, Om gamle Danske Gilder og deres Undergâng, Copenhagen, 1785. Statutes of a Knu guild.

[185] Upon the position of women in guilds, see Miss Toulmin Smith’s introductory remarks to the English Guilds of her father. One of the Cambridge statutes (p. 281) of the year 1503 is quite positive in the following sentence: “Thys statute is made by the comyne assent of all the bretherne and sisterne of alhallowe yelde.”

[186] In mediæval times, only secret aggression was treated as a murder. Blood-revenge in broad daylight was justice; and slaying in a quarrel was not murder, once the aggressor showed his willingness to repent and to repair the wrong he had done. Deep traces of this distinction still exist in modern criminal law, especially in Russia.

[187] Kofod Ancher, l.c. This old booklet contains much that has been lost sight of by later explorers.

[188] They played an important part in the revolts of the serfs, and were therefore prohibited several times in succession in the second half of the ninth century. Of course, the king’s prohibitions remained a dead letter.

[189] The mediæval Italian painters were also organized in guilds, which became at a later epoch Academies of art. If the Italian art of those times is impressed with so much individuality that we distinguish, even now, between the different schools of Padua, Bassano, Treviso, Verona, and so on, although all these cities were under the sway of Venice, this was due — J. Paul Richter remarks — to the fact that the painters of each city belonged to a separate guild, friendly with the guilds of other towns, but leading a separate existence. The oldest guild-statute known is that of Verona, dating from 1303, but evidently copied from some much older statute. “Fraternal assistance in necessity of whatever kind,” “hospitality towards strangers, when passing through the town, as thus information may be obtained about matters which one may like to learn,” and “obligation of offering comfort in case of debility” are among the obligations of the members (Nineteenth Century, Nov. 1890, and Aug. 1892).

[190] The chief works on the artels are named in the article “Russia” of the Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th edition, p. 84.

[191] See, for instance, the texts of the Cambridge guilds given by Toulmin Smith (English Guilds, London, 1870, pp. 274–276), from which it appears that the “generall and principall day” was the “eleccioun day;” or, Ch. M. Clode’s The Early History of the Guild of the Merchant Taylors, London, 1888, i. 45; and so on. For the renewal of allegiance, see the Jómsviking saga, mentioned in Pappenheim’s Altdänische Schutzgilden, Breslau, 1885, p. 67. It appears very probable that when the guilds began to be prosecuted, many of them inscribed in their statutes the meal day only, or their pious duties, and only alluded to the judicial function of the guild in vague words; but this function did not disappear till a very much later time. The question, “Who will be my judge?” has no meaning now, since the State has appropriated for its bureaucracy the organization of justice; but it was of primordial importance in mediæval times, the more so as self-jurisdiction meant self-administration. It must also be remarked that the translation of the Saxon and Danish “guild-bretheren,” or “brodre,” by the Latin convivii must also have contributed to the above confusion.

[192] See the excellent remarks upon the frith guild by J.R. Green and Mrs. Green in The Conquest of England, London, 1883, pp. 229–230.

[193] See Appendix X.

[194] Recueil des ordonnances des rois de France, t. xii. 562; quoted by Aug. Thierry in Considérations sur l’histoire de France, p. 196, ed. 12mo.

[195] A. Luchaire, Les Communes françaises, pp, 45–46.

[196] Guilbert de Nogent, De vita sua, quoted by Luchaire, l.c., p. 14.

[197] Lebret, Histoire de Venise, i. 393; also Marin, quoted by Leo and Botta in Histoire de l’Italie, French edition, 1844, t. i 500.

[198] Dr. W. Arnold, Verfassungsgeschichte der deutschen Freistädte, 1854, Bd. ii. 227 seq.; Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Koeln, Bd. i. 228–229; also the documents published by Ennen and Eckert.

[199] Conquest of England, 1883, p. 453.

[200] Byelaeff, Russian History, vols. ii. and iii.

#organization#revolution#mutual aid#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#a factor of evolution#petr kropotkin

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#gleimposting#Gleimwald#holy shit ich kann nimmer#gleimhaus you did it again#the feels#'Sie sollen mein Schutzgeist sein'#dann kommt er mit Apoll um die Ecke#die hatten doch was#johann wilhelm ludwig gleim#deutsches zeug#Ich entschuldige mich btw dafür so lange nüscht mehr gepostet zu haben hihi

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, jurispru... jurisprudens? is like, um, when peepl talk about laws n stuff. It's like, sumthing to do with how law werk, but I dunno much. Peepl who study jurisprudenze are like, super smart law peepz. They, uh, figure out wut laws mean n how to use them. Itz kind of like a big puzzel with rules, n they haf to figure it out. But, ya know, I only no a lil bit, so, yeah, jurisprudesense is sumthing law-ish.

0 notes

Text

Der Verfremdungseffekt von Teubners Rechtssoziologie

0 notes

Text

Habeck will Coronahilfen von Unternehmen zurück

Tichy:»Juristen, aber auch Historiker, nutzen gerne das Wort „präzedenzlos“. Hierbei ist ein Vorgang zu verstehen, den es so noch nicht gab und der bislang ohne Vergleich in die Jurisprudenz bzw. in die Geschichte eingeht. So bezeichnete der Historiker Rolf Peter Sieferle Merkels Grenzöffnung als präzedenzlos, da kein Staatschef eine solche Entscheidung zuvor jemals getroffen hatte.

Der Beitrag Habeck will Coronahilfen von Unternehmen zurück erschien zuerst auf Tichys Einblick. http://dlvr.it/T3h6ms «

0 notes

Text

IVSTI ATQUE INIVSTI SCIENTIA

Detail of the ceiling of the Festive Hall of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW). The eleborate ceiling frescos were created by Gregorio Guglielmi in 1755, the architectural paintings by Domenico Francia. The sculptures in the hall are attributed to Johann Gabriel Müller, called Mollinarolo, professor of sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

Auschnitt aus der Decke des Festsaals der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW). Das Deckenfresko schuf Gregorio Guglielmi 1755, die Architekturmalereien Domenico Francia. Die Skulpturen des Saales werden Johann Gabriel Müller, genannt Mollinarolo, Professor für Bildhauerei an der Akademie der bildenden Künste in Wien, zugeschrieben.

OeAW, Dr. Ignaz Seipel-Platz 2, 1010 Wien, Österreich

#ÖAW#Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften#Austrian Academy of Sciences#Festsaal#festive hall#ceiling#frescos#Deckenfresko#jurisprudence#Jurisprudenz#Gregorio Guglielmi#1755#Domenico Francia#paintings#architecture#Architektur#Malereien#Mollinarolo#Johann Gabriel Müller#sculptures#Skulpturen#Wien#Vienna#Вена#Vienne#Vídeň#Wiedeń#Bécs#Viedeň#OeAW

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Philosophie und Jurisprudenz, John Armleder, 1993, MoMA: Drawings and Prints

Gift of Dan Redmon

Size: overall: 1 1/4 x 12 3/4 x 12 7/8" (3.2 x 32.4 x 32.7 cm)

Medium: Multiple of mixed media on fabric in cardboard box

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/68665

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Muppet Show: Koozebanian Mating Ritual

youtube

Letter

Liebes Tagebuch,

heute habe ich geträumt, dass ich ein junger Architekturstudent vom Planeten Koozebane bin. Ich hatte exakt 2000 koozebanische Rupien gespart, nach dem Bachelor 15 Tage frei und mir für 1987 Rupien ein Pauschalreise mit geführter Tour, Übernachtung, Hin- und Rückflugticket zur Erde gekauft, um einmal in meinem Leben, und zwar 14 Tage lang, die Architektur dort zu studieren. 235 Städte in 12 Tagen, 2 Tage zur freien Verfügung, unbegrenzt Cola und Blockschokolade inklusive. Seltsamer Traum. Muss jetzt los, der Tag beginnt und die Tagung setzt fort.

P.S. Quid est roma? Contubernium Romanorum.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Haering: „Philosophie“

Studie zu den 3 Fakultätsbildern von Gustav Klimt:

Philosophie, Medizin und Jurisprudenz

Destroyed by burning 1945

Ink drawing, 2012

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Footnotes, 101-150

[101] Gill, quoted in Gerland and Waitz’s Anthropologie, v. 641. See also pp. 636–640, where many facts of parental and filial love are quoted.

[102] Primitive Folk, London, 1891.

[103] Gerland, loc. cit. v. 636.

[104] Erskine, quoted in Gerland and Waitz’s Anthropologie, v. 640.

[105] W.T. Pritchard, Polynesian Reminiscences, London, 1866, p. 363.

[106] It is remarkable, however, that in case of a sentence of death, nobody will take upon himself to be the executioner. Every one throws his stone, or gives his blow with the hatchet, carefully avoiding to give a mortal blow. At a later epoch, the priest will stab the victim with a sacred knife. Still later, it will be the king, until civilization invents the hired hangman. See Bastian’s deep remarks upon this subject in Der Mensch in der Geschichte, iii. Die Blutrache, pp. 1–36. A remainder of this tribal habit, I am told by Professor E. Nys, has survived in military executions till our own times. In the middle portion of the nineteenth century it was the habit to load the rifles of the twelve soldiers called out for shooting the condemned victim, with eleven ball-cartridges and one blank cartridge. As the soldiers never knew who of them had the latter, each one could console his disturbed conscience by thinking that he was not one of the murderers.

[107] In Africa, and elsewhere too, it is a widely-spread habit, that if a theft has been committed, the next clan has to restore the equivalent of the stolen thing, and then look itself for the thief. A. H. Post, Afrikanische Jurisprudenz, Leipzig, 1887, vol. i. p. 77.

[108] See Prof. M. Kovalevsky’s Modern Customs and Ancient Law (Russian), Moscow, 1886, vol. ii., which contains many important considerations upon this subject.

[109] See Carl Bock, The Head Hunters of Borneo, London, 1881. I am told, however, by Sir Hugh Law, who was for a long time Governor of Borneo, that the “head-hunting” described in this book is grossly exaggerated. Altogether, my informant speaks of the Dayaks in exactly the same sympathetic terms as Ida Pfeiffer. Let me add that Mary Kingsley speaks in her book on West Africa in the same sympathetic terms of the Fans, who had been represented formerly as the most “terrible cannibals.”

[110] Ida Pfeiffer, Meine zweite Weltrieze, Wien, 1856, vol. i. pp. 116 seq. See also Müller and Temminch’s Dutch Possessions in Archipelagic India, quoted by Elisée Reclus, in Géographie Universelle, xiii.

[111] Descent of Man, second ed., pp. 63, 64.

[112] See Bastian’s Mensch in der Geschichte, iii. p. 7. Also Gray, loc. cit. ii. p. 238.

[113] Miklukho-Maclay, loc. cit. Same habit with the Hottentots.

[114] Numberless traces of post-pliocene lakes, now disappeared, are found over Central, West, and North Asia. Shells of the same species as those now found in the Caspian Sea are scattered over the surface of the soil as far East as half-way to Lake Aral, and are found in recent deposits as far north as Kazan. Traces of Caspian Gulfs, formerly taken for old beds of the Amu, intersect the Turcoman territory. Deduction must surely be made for temporary, periodical oscillations. But with all that, desiccation is evident, and it progresses at a formerly unexpected speed. Even in the relatively wet parts of South-West Siberia, the succession of reliable surveys, recently published by Yadrintseff, shows that villages have grown up on what was, eighty years ago, the bottom of one of the lakes of the Tchany group; while the other lakes of the same group, which covered hundreds of square miles some fifty years ago, are now mere ponds. In short, the desiccation of North-West Asia goes on at a rate which must be measured by centuries, instead of by the geological units of time of which we formerly used to speak.

[115] Whole civilizations had thus disappeared, as is proved now by the remarkable discoveries in Mongolia on the Orkhon and in the Lukchun depression (by Dmitri Clements).

[116] If I follow the opinions of (to name modern specialists only) Nasse, Kovalevsky, and Vinogradov, and not those of Mr. Seebohm (Mr. Denman Ross can only be named for the sake of completeness), it is not only because of the deep knowledge and concordance of views of these three writers, but also on account of their perfect knowledge of the village community altogether — a knowledge the want of which is much felt in the otherwise remarkable work of Mr. Seebohm. The same remark applies, in a still higher degree, to the most elegant writings of Fustel de Coulanges, whose opinions and passionate interpretations of old texts are confined to himself.

[117] The literature of the village community is so vast that but a few works can be named. Those of Sir Henry Maine, Mr. Seebohm, and Walter’s Das alte Wallis (Bonn, 1859), are well-known popular sources of information about Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. For France, P. Viollet, Précis de l’histoire du droit français. Droit privé, 1886, and several of his monographs in Bibl. de l’Ecole des Chartes; Babeau, Le Village sous l’ancien régime (the mir in the eighteenth century), third edition, 1887; Bonnemère, Doniol, etc. For Italy and Scandinavia, the chief works are named in Laveleye’s Primitive Property, German version by K. Bücher. For the Finns, Rein’s Föreläsningar, i. 16; Koskinen, Finnische Geschichte, 1874, and various monographs. For the Lives and Coures, Prof. Lutchitzky in Severnyi Vestnil, 1891. For the Teutons, besides the well-known works of Maurer, Sohm (Altdeutsche Reichs- und Gerichts- Verfassung), also Dahn (Urzeit, Völkerwanderung, Langobardische Studien), Janssen, Wilh. Arnold, etc. For India, besides H. Maine and the works he names, Sir John Phear’s Aryan Village. For Russia and South Slavonians, see Kavelin, Posnikoff, Sokolovsky, Kovalevsky, Efimenko, Ivanisheff, Klaus, etc. (copious bibliographical index up to 1880 in the Sbornik svedeniy ob obschinye of the Russ. Geog. Soc.). For general conclusions, besides Laveleye’s Propriété, Morgan’s Ancient Society, Lippert’s Kulturgeschichte, Post, Dargun, etc., also the lectures of M. Kovalevsky (Tableau des origines et de l’évolution de la famille et de la propriété, Stockholm, 1890). Many special monographs ought to be mentioned; their titles may be found in the excellent lists given by P. Viollet in Droit privé and Droit public. For other races, see subsequent notes.

[118] Several authorities are inclined to consider the joint household as an intermediate stage between the clan and the village community; and there is no doubt that in very many cases village communities have grown up out of undivided families. Nevertheless, I consider the joint household as a fact of a different order. We find it within the gentes; on the other hand, we cannot affirm that joint families have existed at any period without belonging either to a gens or to a village community, or to a Gau. I conceive the early village communities as slowly originating directly from the gentes, and consisting, according to racial and local circumstances, either of several joint families, or of both joint and simple families, or (especially in the case of new settlements) of simple families only. If this view be correct, we should not have the right of establishing the series: gens, compound family, village community — the second member of the series having not the same ethnological value as the two others. See Appendix IX.

[119] Stobbe, Beiträg zur Geschichte des deutschen Rechtes, p. 62.

[120] The few traces of private property in land which are met with in the early barbarian period are found with such stems (the Batavians, the Franks in Gaul) as have been for a time under the influence of Imperial Rome. See Inama-Sternegg’s Die Ausbildung der grossen Grundherrschaften in Deutschland, Bd. i. 1878. Also, Besseler, Neubruch nach dem älteren deutschen Recht, pp. 11–12, quoted by Kovalevsky, Modern Custom and Ancient Law, Moscow, 1886, i. 134.

[121] Maurer’s Markgenossenschaft; Lamprecht’s “Wirthschaft und Recht der Franken zur Zeit der Volksrechte,” in Histor. Taschenbuch, 1883; Seebohm’s The English Village Community, ch. vi, vii, and ix.

[122] Letourneau, in Bulletin de la Soc. d’Anthropologie, 1888, vol. xi. p. 476.

[123] Walter, Das alte Wallis, p. 323; Dm. Bakradze and N. Khoudadoff in Russian Zapiski of the Caucasian Geogr. Society, xiv. Part I.

[124] Bancroft’s Native Races; Waitz, Anthropologie, iii. 423; Montrozier, in Bull. Soc. d’Anthropologie, 1870; Post’s Studien, etc.

[125] A number of works, by Ory, Luro, Laudes, and Sylvestre, on the village community in Annam, proving that it has had there the same forms as in Germany or Russia, is mentioned in a review of these works by Jobbé-Duval, in Nouvelle Revue historique de droit français et étranger, October and December, 1896. A good study of the village community of Peru, before the establishment of the power of the Incas, has been brought out by Heinrich Cunow (Die Soziale Verfassung des Inka-Reichs, Stuttgart, 1896. The communal possession of land and communal culture are described in that work.

[126] Kovalevsky, Modern Custom and Ancient Law, i. 115.

[127] Palfrey, History of New England, ii. 13; quoted in Maine’s Village Communities, New York, 1876, p. 201.

[128] Königswarter, Études sur le développement des sociétés humaines, Paris, 1850.

[129] This is, at least, the law of the Kalmucks, whose customary law bears the closest resemblance to the laws of the Teutons, the old Slavonians, etc.

[130] The habit is in force still with many African and other tribes.

[131] Village Communities, pp. 65–68 and 199.

[132] Maurer (Gesch. der Markverfassung, sections 29, 97) is quite decisive upon this subject. He maintains that “All members of the community... the laic and clerical lords as well, often also the partial co-possessors (Markberechtigte), and even strangers to the Mark, were submitted to its jurisdiction” (p. 312). This conception remained locally in force up to the fifteenth century.

[133] Königswarter, loc. cit. p. 50; J. Thrupp, Historical Law Tracts, London, 1843, p. 106.

[134] Königswarter has shown that the ferd originated from an offering which had to be made to appease the ancestors. Later on, it was paid to the community, for the breach of peace; and still later to the judge, or king, or lord, when they had appropriated to themselves the rights of the community.

[135] Post’s Bausteine and Afrikanische Jurisprudenz, Oldenburg, 1887, vol. i. pp. 64 seq.; Kovalevsky, loc. cit. ii. 164–189.

[136] O. Miller and M. Kovalevsky, “In the Mountaineer Communities of Kabardia,” in Vestnik Evropy, April, 1884. With the Shakhsevens of the Mugan Steppe, blood feuds always end by marriage between the two hostile sides (Markoff, in appendix to the Zapiski of the Caucasian Geogr. Soc. xiv. 1, 21).

[137] Post, in Afrik. Jurisprudenz, gives a series of facts illustrating the conceptions of equity inrooted among the African barbarians. The same may be said of all serious examinations into barbarian common law.

[138] See the excellent chapter, “Le droit de La Vieille Irlande,” (also “Le Haut Nord”) in Études de droit international et de droit politique, by Prof. E. Nys, Bruxelles, 1896.

[139] Introduction, p. xxxv.

[140] Das alte Wallis, pp. 343–350.

[141] Maynoff, “Sketches of the Judicial Practices of the Mordovians,” in the ethnographical Zapiski of the Russian Geographical Society, 1885, pp. 236, 257.

[142] Henry Maine, International Law, London, 1888, pp. 11–13. E. Nys, Les origines du droit international, Bruxelles, 1894.

[143] A Russian historian, the Kazan Professor Schapoff, who was exiled in 1862 to Siberia, has given a good description of their institutions in the Izvestia of the East-Siberian Geographical Society, vol. v. 1874.

[144] Sir Henry Maine’s Village Communities, New York, 1876, pp. 193–196.

[145] Nazaroff, The North Usuri Territory (Russian), St. Petersburg, 1887, p. 65.

[146] Hanoteau et Letourneux, La Kabylie, 3 vols. Paris, 1883.

[147] To convoke an “aid” or “bee,” some kind of meal must be offered to the community. I am told by a Caucasian friend that in Georgia, when the poor man wants an “aid,” he borrows from the rich man a sheep or two to prepare the meal, and the community bring, in addition to their work, so many provisions that he may repay tHe debt. A similar habit exists with the Mordovians.

[148] Hanoteau et Letourneux, La kabylie, ii. 58. The same respect to strangers is the rule with the Mongols. The Mongol who has refused his roof to a stranger pays the full blood-compensation if the stranger has suffered therefrom (Bastian, Der Mensch in der Geschichte, iii. 231).

[149] N. Khoudadoff, “Notes on the Khevsoures,” in Zapiski of the Caucasian Geogr. Society, xiv. 1, Tiflis, 1890, p. 68. They also took the oath of not marrying girls from their own union, thus displaying a remarkable return to the old gentile rules.

[150] Dm. Bakradze, “Notes on the Zakataly District,” in same Zapiski, xiv. 1, p. 264. The “joint team” is as common among the Lezghines as it is among the Ossetes.

#organization#revolution#mutual aid#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#a factor of evolution#petr kropotkin

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

❗ Запоминаем: Слова, употребляемые в немецком языке только в единственном числе. die Milch - молоко die Schokolade - шоколад das Fleisch - мясо die Baumwolle - хлопок das Leder - кожа das Eisen - железо das Kupfer - медь das Gold - золото der Schnee - снег die Kindheit - детство die Jugend - молодость der Hass - ненависть der Neid - зависть die Furcht - страх der Fleiß - прилежание die Kälte - холод die Wärme - тепло die Ruhe - спокойствие die Treue - верность das Vertrauen - доверие das Bewusstsein - сознание das Glück - счастье das Pech - неудача die Musik - музыка die Erziehung - воспитание die Jurisprudenz - юриспруденция die Nähe - близость das Gute - хорошее

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fundstück

Shylock, Die Geschichte einer Figur

von Hermann Sinsheimer

Zur Vorgeschichte dieses Buches

Ich habe dieses Buch in den Jahren 1936 und 1937 geschrieben – in einer Welt, die es heute nicht mehr gibt: in der ehemaligen Hauptstadt des Deutschen Reiches, Berlin, in der Welt der Nazis, der Konzentrationslager und Pogrome, der Folterungen und Morde. Kein Wunder, daß dieses Buch, wenn es jetzt erscheint, bereits eine Geschichte hinter sich hat, die zu erzählen sich lohnt.

Der Schauspieler Edmund Kaen als Shylock (1814)

Ich hatte gerade einen zwei Jahre währenden Kampf um die Befreiung eines älteren Bruders hinter mir, den das Nazi-Regime wegen angeblichen Landesverrats eingesperrt hatte. Der von den Nazis im April 1934 eingesetzte Volksgerichtshof üblen Angedenkens sprach meinen Bruder so gut wie frei. Ja, jener Volksgerichtshof tat sogar das Seine, um ihn vor der Gestapo zu bewahren – am 22. Dezember 1935! Ich werde diesen Tag so wie die vorausgegangenen zwei Jahre des Kampfes nie vergessen.

Nun versuchte ich, Deutschland zu verlassen. Es gelang mir nicht. In meiner äußeren und inneren Bedrängnis beschloß ich, wenn ich schon nicht aus dem verpesteten Land entkommen konnte, so doch wenigstens aus der verpesteten Zeit zu fliehen. Auf dieser »Flucht« in das Abenteuer der Literatur und der Geschichte begegnete mir – fast zwangsläufig – Shylock, das Spiegelbild des europäischen Juden, wie er niemals war, und Widerspiel alles Jüdischen, wie es wirklich war. Ich beschloß, seine Figur zu ergründen, soweit es in meinen Kräften stand. Das heißt: während die Nazis ringsum ihre blutrünstigen, barbarischen Shylockiaden inszenierten, suchte ich die Gefilde Shakespeares und der jüdischen Geschichte auf.

Wenn das eine Flucht war, so darf man es auch zugleich eine Art von Heimkehr nennen – Heimkehr in die Welt der Dichtung und des Spiels, denen die besten Kräfte meines bisherigen Lebens gewidmet waren, in die Vorwelt des jüdischen Volkes, zu dem ich selbst gehöre, und auch in das Gebiet der Jurisprudenz, der ich vor vielen Jahren eine Reihe meiner Studien- und Berufsjahre gewidmet hatte. Ja, es war in der Tat eine Rück- und Heimkehr zu fast allem, das mein Leben ausgemacht und mein Wesen gebildet hat, bevor die Nazis nach uns griffen, um uns zu vernichten.

Als das Buch fertig war, fand ich, wenn auch nicht sehr rasch, einen Verleger, einen jüdischen natürlich, denn bei anderen durfte ich ja als Jude nichts veröffentlichen. Auch so war es für uns schwierig genug, das Buch herauszubringen. Denn das Manuskript mußte einer Nazi-Stelle zur Vorzensur unterbreitet werden, die dem »Judenvogt«, dem Juden-Geßler Hinkel unterstellt war. Verleger und Autor sandten das Manuskript nicht ohne geheimes Bangen ein. Aber – es wurde zur Veröffentlichung zugelassen! Wahrscheinlich ist der Nazi-Zensor in seiner Lektüre nicht über das erste Kapitel, das von Shakespeare handelt, hinausgekommen.

Verleger und Autor veranstalteten nun eine Subskription unter den deutschen Juden, die Erfolg hatte. Dann übergab der Verleger das Manuskript einer Druckerei in Munkacz, Tschechoslowakei. Aber was sich heute so rasch erzählt, nahm damals viel Zeit in Anspruch. Und so war inzwischen das Frühjahr 1938 gekommen. Die Ungarn besetzten – von Hitler ermuntert – die Stadt Munkacz und bliesen der dortigen jüdischen Druckerei das Lebenslicht aus. Im gleichen Frühjahr war es mir endlich gelungen, Deutschland zu verlassen und mich in London niederzulassen.

Hier bot ich das Manuskript dem einen oder anderen englischen Verleger an – ohne Erfolg. Sie erklärten, es sei jetzt nicht die Zeit für solch ein Buch (denn es war ja die Zeit der »Befriedungspolitik« unseligen Angedenkens), sie wollten warten, bis die europäische »Krise« vorüber sei. Die »Krise« war im September 1939 vorüber! Nun wurde nicht nur das Interesse, sondern auch das Papier knapp. Shakespeare und die Juden – ein Buch über sie konnte warten, bis wieder Friede sein würde.

So bekam mein Manuskript seinen Teil vom Londoner Bombenregen ab. Ich selbst begab mich wieder auf eine »Flucht« – nicht aus London, sondern in eine lange Krankheit. Nun war wirklich keine Zeit für Shylock!

Aber kaum konnte ich mich wieder einigermaßen rühren, begann ich (es war ein Unternehmen, dem ich ohne den guten Rat und Beistand englischer Freunde nicht gewachsen gewesen wäre) das Manuskript selbst ins Englische zu übersetzen und es für englische Leser zu bearbeiten. Das war, um eine private Bagatelle mit der schauerlichsten Untat der Weltgeschichte zu synchronisieren, zu der Zeit, als die Nazis Millionen Juden in Gasöfen hinmordeten. Wieder einmal, wie einst und je, aber kaltblütiger als je vorher, wurde der Jude, weil er Jude war, verbrannt.

Dann, endlich, ging der Krieg zu Ende – freilich nicht die »Krise«, von der die englischen Verleger im Frühjahr 1938 gesprochen hatten, ganz gewiß nicht die Krise für die europäischen Juden. Jetzt nahm der Londoner Verleger Victor Gollancz meine englische Version zur Veröffentlichung an.

Während ich diese Geschichte meines Buches niederschreibe, ist die englische Ausgabe noch nicht erschienen. Um so ungeduldiger wende ich mich der Aufgabe zu, eine deutsche Ausgabe vor deutsche Leser zu bringen – Juden und Christen. Für sie habe ich es vor fast zehn Jahren geschrieben, auf sie habe ich es gezielt.

Ich trete mit gutem Gewissen vor das Forum der Literatur-, Geschichts- und Rechtswissenschaft. Allerdings ist das Buch nicht für Gelehrte geschrieben. Ich habe daher, vom Literaturverzeichnis abgesehen, auf den wissenschaftlichen Apparat verzichtet. Es ist ein Buch für Laien, die einen der fürchterlichsten Auswüchse unserer Zeit, den Antisemitismus, in seinem frühen Stadium kennen und verstehen lernen wollen. Es ist ein Buch für Menschen, die den großen Dichter Shakespeare lieben, aber denen die Wahrheit noch höher steht – die Wahrheit, ohne die die Menschheit verkommen muß. Dieses Buch ist geschrieben als ein bescheidener Beitrag zur Abwendung der infernalischen Gefahr, in die der Nationalsozialismus Deutschland und die Welt gebracht hat.

Wer zum Verständnis scheinbar unverständlicher Zeiterscheinungen beiträgt, tut damit etwas zur Verständigung der Menschen untereinander. So ist dieses Buch, nach der Absicht seines Autors, durchaus kein Kampfbuch, sondern ein Versuch, zum Frieden der Welt beizutragen.

London, im Jahre 1946.

H. S.

Einleitung

Jedes bedeutende Kunstwerk hat auch geschichtliche Bedeutung. Es verzeichnet Geschichte und hat teil an der Geschichte. Shakespeares »Kaufmann von Venedig« aus diesem Blickwinkel zu betrachten, ist die Absicht dieses Buches. Shakespeare hat die ›haltbarste‹ nachbiblische Judenfigur geschaffen. Er hat in ihr notwendig über das Judentum berichtet und gerichtet. Er hat mit ihr jüdische Geschichte geschrieben und gemacht.

Dieses Buch will ihm, vom jüdischen Standpunkt aus, den Zoll dafür erstatten, indem es die Geschichte seines Shylock schreibt und erklärt. Indem es diese Geschichte schreibt, muß es den Shylock nicht nur literarisch, sondern auch historisch und mythologisch zu ergründen suchen. Ihr Spielraum ist das 16. Jahrhundert. Ihr Lebensraum aber ist das Schicksal des jüdischen Volkes von der biblischen Zeit an bis heute.

Während der Arbeit an dem Buch bin ich oft gefragt worden, ob ich ein »aktuelles« Buch zu schreiben vorhabe.

Die Antwort darauf lautet: Es ist mir nicht bekannt, daß etwa dänische Staats- und Hofmänner auch heute noch als geschwätzige Poloniusse gelten oder Mohren als eifersüchtige Othellos. Aber die Juden, auch wenn sie weder habgierig noch grausam sind, gelten immer noch als Shylocks. Richtiger: Shylock gilt für sie.

Somit ist dieses Buch aktuell.

Es wäre ein Leichtes gewesen, die folgenden Seiten mit einer Unzahl von Anmerkungen und Hinweisen zu pflastern. Ich habe davon abgesehen. Der Leser ohne wissenschaftliches Interesse würde davon nur gestört werden. Der gelehrte Leser aber wird aus dem Literaturnachweis am Schlusse des Buches die Quellen und Belege leicht herausfinden.

Berlin, im März 1937.

H. S.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Gustav Klimt. 1899–1907. Philosophie. (1945 zerstört)

Gustav Klimt. 1899–1907. Medizin. (1945 zerstört)

Gustav Klimt. 1899–1907. Jurisprudenz. (1945 zerstört)

1 note

·

View note