#Napoleonic Code

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code, also known as the Civil Code of 1804, is one of Napoleon Bonaparte's most significant and enduring legacies. It is a comprehensive system of laws that aimed to reform and standardize the legal framework of France. Before the Napoleonic Code, France's legal system was a patchwork of regional laws, feudal customs, and royal edicts, which created inconsistency and confusion. The code had a profound impact on not only France but also many other countries, serving as a model for modern legal systems around the world.

Key Features of the Napoleonic Code:

Equality Before the Law:

The Napoleonic Code ensured legal equality for all male citizens, meaning that laws would apply equally to everyone, regardless of their birth, class, or wealth. This abolished the feudal privileges that had been enjoyed by the aristocracy under the old regime.

It established the principle that nobles, clergy, and commoners were all subject to the same laws.

Abolition of Feudalism:

The code abolished feudal obligations and privileges, including serfdom and manorial dues, ensuring that people were free from feudal bonds and that property rights were more clearly defined.

Civil Rights and Liberties:

The code affirmed individual rights, such as the right to own property, the freedom of contract, and the right to be free from arbitrary arrest and imprisonment.

It supported the idea of religious freedom, although it retained certain restrictions on freedom of the press and political dissent.

Property Rights:

The code placed a strong emphasis on the protection of private property. Property ownership was seen as a fundamental right, and the code established clear guidelines for acquiring, transferring, and inheriting property.

The inheritance laws introduced by the code were particularly significant: they established that property must be divided equally among all heirs (children) upon the death of a property owner, rather than allowing for primogeniture (where the eldest son inherits everything). This was intended to prevent the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few families.

Secular Law:

The Napoleonic Code was secular, separating the legal system from the influence of the Catholic Church. It made civil marriage the only legally recognized form of marriage, and divorce was legalized, although with more restrictions than under earlier revolutionary laws.

Family Law and Patriarchy:

The code placed significant emphasis on the family, which Napoleon saw as the foundation of society. It gave fathers considerable authority over their children and wives.

Women were largely subordinate under the code. A wife was legally required to obey her husband, and her ability to manage property or engage in legal contracts was limited without her husband’s permission. Women also had fewer rights in divorce and child custody matters.

Codification and Clarity:

One of the Napoleonic Code’s most revolutionary aspects was its clarity and simplicity. Napoleon sought to replace the confusing and inconsistent legal systems of pre-revolutionary France with a single, coherent, and easily understandable legal framework.

The code is written in clear, accessible language, making it more understandable for the public, rather than being limited to legal professionals.

Merit-Based Society:

By ensuring equality before the law and abolishing hereditary privileges, the Napoleonic Code supported a merit-based society, where individuals could advance based on talent and achievement, rather than birth or status.

Influence of the Napoleonic Code:

The Napoleonic Code had a significant influence not only in France but also abroad. Napoleon implemented it in the territories he conquered, and its principles spread to parts of Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, and Spain. Over time, many other countries, including those in Latin America and parts of Africa and the Middle East, adopted or adapted aspects of the code into their own legal systems.

Global Legacy:

The Napoleonic Code is widely regarded as one of the most influential legal documents in the world. It served as the basis for civil law systems in many countries, particularly in continental Europe and Latin America.

Its emphasis on equality before the law, property rights, and a secular legal framework has shaped modern legal traditions in many countries. It is still the foundation of civil law in France and has been a model for legal codes around the world, particularly in countries with civil law systems, as opposed to common law systems (like the UK or the US).

The Napoleonic Code was a transformative legal document that codified the principles of the French Revolution—equality before the law, meritocracy, and secular governance—while also promoting a strong, centralized state and patriarchal family structure. Its impact extended far beyond Napoleon's reign, influencing modern legal systems across Europe and beyond, and it remains a foundational element of civil law to this day.

#Napoleonic Code#Civil Code of 1804#Napoleon Bonaparte#French legal system#Equality before the law#Legal reform#Abolition of feudalism#Private property rights#Meritocracy#Secular law#French Revolution#Family law#Patriarchy#Civil law system#European legal history#Codification of law#Inheritance law#Divorce law#Legal clarity#Global legal influence#new blog#today on tumblr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tapestry of History, 18 – The Rise of the West, 13 – The Enlightenment, 5 – the French Revolution

(Image – Napoleon, crowned Emperor of the French, 1804, painting by David. Wikipedia) From 1792 to 1815, Europe was engulfed in a series of great conflicts resulting from the shattering consequences of the French Revolution. It is estimated that as many as ten million died in these conflicts – the most terrible war death toll in history before World War One. These wars were heavily influenced in…

#Christianity#Enlightened Despotism#Enlightenment#Enlightenment and Christianity#French Revolution#History of the West#Levee en masse#Napoleon#Napoleonic Code#Secularism

0 notes

Text

Haley Bennett is Stoically Powerful and Raw in Widow Clicquot

Did you know that Veuve Clicquot was invented by a a woman - the Grand Dame of Champagne - Barbe Nicole Ponsardin? #widowclicquot #vertical #podcast

Ever wonder where some of your favorite bottles of champagne originated from and did you ever once think they many have been invented by a woman? Yup, the elegant bottle with the orange label, engineered by methods still used today by all champagne producers is courtesy of the “Grande Dame of Champagne” – Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin. Based on the best-selling book The Widow Clicquot by Tilar J.…

#black podcat#champagne#france#haley bennett#herstory#napoleonic code#podcast#Tom Sturridge#veritcal pictures#veuve clicquot#widow clicquot

0 notes

Text

TW: Animal Gore and Blood

Sunday Best

>

>

Something about the thought of Sock having some form of religious trauma and him getting his family ostracized from the church. As if this kid didn’t have a shit ton of issues already.

#tw blood#tw dead animal#welcome to hell#w2h2#erica wester#sock sowachowski#w2h fanart#procreate#homicidal twink#napoleon maxwell sowachowski#sock w2h#he has a fear of providence expecting her to be this riotous being that would probably kill him again if she knew what he did when alive#possible correlation to Take Me to Chruch by Hozier#His parents have all those little metal crosses around their house-#also trans sock coded

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

imn tired

#lord castlereagh#klemens von metternich#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#history#19th century#history art#babygurl coded#my art#wish i could go to europe and distract myself with a funny lil austrian guy who is not a good person#but neither am i so it's cool

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thought I was so funny for making this

#it was for an assignment#had to choose 3 words and use them in a sentence#i chose coded street wear and upcycle#napoleonic era#jean lannes#louis nicholas davout#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic shitpost#my art

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bro let himself be whisked away to sate his insatiable hyperfixation. Mad respect, honestly.

#ikemen vampire#ikevamp sebastian#mild spoilers that kinda already pop up in the loading messages#ikevamp napoleon's route#ikevamp#ikemen vampire sebastian#i love how so many cybird characters are neurodivergent-coded 'cause it helps me feel more justified about my 130+ pages of ikevil notes

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Die Kaiserin | 2.05 – “Der Wald in uns”

#diekaiserinedit#perioddramaedit#theempressedit#die kaiserin#the empress#the empress netflix#johannes nussbaum#maximilian of mexico#mine#again this show is not good so im cherrypicking scenes that fit my narrative#and max & sophie is everything. to me#he is sooo son of napoleon ii coded. look at him.#multiple anna mentions!!! and still no karl ludwig lol good for him#he and franz karl are living their best lives off screen

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

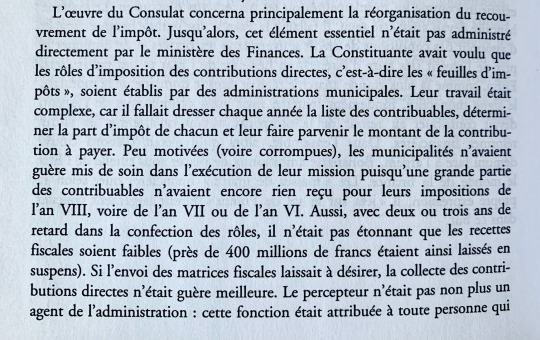

Changes to the Tax Collection System in Revolutionary and Napoleonic France

My translation from Le prix de la gloire: Napoléon et l’argent by Pierre Branda.

This part is specifically about the reforms made to the tax collection system. Problems with taxation had been the source of many woes, so it went through major changes.

“The [tax] work of the Consulate mainly concerned the reorganization of tax collection. Until now, this essential element was not administered directly by the Ministry of Finance. The Constituent Assembly had wanted the tax rolls for direct contributions, that is to say the ‘tax slips’, to be established by municipal administrations. Their work was complex, because each year it was necessary to draw up a list of taxpayers, determine each person’s share of tax and send them the amount of the contribution to pay. Poorly motivated (or even corrupt), the municipalities had put little care in the execution of their mission since a large part of the taxpayers had not yet received anything for their taxes of year VIII, or even of year VII or year VI. Also, with two or three years of delay in preparing the rolls, it was not surprising that tax revenues were low (nearly 400 million francs were thus left outstanding). If the sending of tax matrices left something to be desired, the collection of direct contributions was hardly better. The tax collector was also not an agent of the administration: this function was assigned to any person who agreed to collect taxes with the lowest possible commission (otherwise called ‘collecte à la moins-dite’). With such a system, there were numerous inadequacies, often due to incompetence, but also due to the prevailing spirit of fraud. However, in their defense, the profits of the collectors were most of the time too low to provide such a service; also, to compensate for their losses, they were ‘forced’ to multiply small and big cheats. In any case, in such a troubled period, letting simple individuals carry out such a delicate mission could only be dangerous for the regularity of public accounts. In short, the mode of operation of taxation that Bonaparte and Gaudin inherited was failing on all sides and threatened to sink the State.”

“One month after Gaudin’s appointment, on December 13, 1799, the Directorate of Direct Contributions was created with the mission of establishing and sending tax matrices. This administration, dependent on the Ministry of Finance, was made up of a general director, 99 departmental directors and 840 inspectors and controllers. The organization of direct contributions became both centralized and pyramidal, the opposite of the previous system, decentralized and with a confused hierarchy. The work of preparing the rolls, for so long entrusted to local authorities, passed entirely ‘in the hands of the Minister of Finance’ and in this way the taxpayer found himself in direct contact with the administration. The tax system no longer having any obstacles, the beneficial effects of such a measure did not take long to be felt. With ardor, the agents of this new administration carried out considerable work: three series of rolls, that is to say more than one hundred thousand tax slips, were established in a single year. It must be said that the ministry had not skimped on their pay (6,000 francs per year for a director, 4,000 for an inspector and 1,800 for a controller), which was undoubtedly not unrelated to such success.”

“Tax reform was slower. It was not until 1804 that all tax collectors were civil servants. The consular system gradually replaced the collectors of the departments, then of the main cities and finally of all the municipalities whose tax rolls exceeded 15,000 francs. At the end of the Consulate, the entire tax administration was thus entirely dependent on the central government. Subsequently, the one in charge of indirect contributions (taxes on tobacco, alcohol or salt) created on February 25, 1804 and called the Régie des droits réunis was built on the same pyramidal and centralized model. It was the same later for customs.”

“According to Michel Bruguière, historian of public finances, ‘Napoleon and Gaudin can be considered the builders of the French tax administration. [...] They had also developed and codified the essential principles of our tax law, so profoundly derogatory from the rules of French law, since the taxpayer has nothing to do with it, while the administration has all the powers’. Basically, after having clearly understood the true cause of the ‘financial wound’, Bonaparte wanted an effective, almost ‘despotic’ instrument to avoid experiencing the unfortunate fate of his predecessors. As a good soldier, he created a fiscal ‘army’ responsible for providing the regime with the sinews of war. It was also necessary to definitively break the link between private interests and state service in everything that concerned public revenue. The time of the farmer generals of the Ancien Régime or the ‘second-hand’ collectors of the Directory was well and truly over. Napoleon Bonaparte, with his fierce desire to centralize power in this area as in many others, undoubtedly gave his regime the means to last.”

French:

Page 208

Page 209

Page 210

#Le prix de la gloire: Napoléon et l’argent#Le prix de la gloire#Napoléon et l’argent#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#19th century#first french empire#1800s#french empire#france#history#reforms#finance#economics#french revolution#frev#la révolution française#révolution française#Gaudin#tax#tax collection system#taxation#law#napoleonic code#source#french history#branda#Pierre branda

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The world suffers a lot, not because of the violence of bad people, but because of the silence of good people."

Napoleon Bonaparte, later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars.

Born: 15 August 1769, Ajaccio, France

Died: 5 May 1821, Longwood House, Longwood, Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

#Military Leader#Emperor of France#French Revolution#Napoleonic Wars#Corsican General#Historical Figure#French Emperor#French Revolution Era#European History#Bonapartism#Emperor Napoleon#Political Leader#Napoleonic Code#Continental System#Waterloo#Elba#St. Helena#French Conquest#War Strategist#Legacy of Napoleon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

have to honor my url as well as my blog title and post my other personal bit of all time banter between them

#so good on so many fucking levels. illya automatically pulling out the handkerchief. him all but growling out ''her noble rescuer''.#the little shadow box napoleon does in response to ''youre so dashing.''#when napoleon hit him with the ''i was actually rather embarrassed for you'' illya should have jumped on him and started#violating the code of good practice right there and then. thats all i'll say.#tmfu#the man from uncle#tmfu tv#illya kuryakin#napoleon solo#napollya

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Perfect Protagonist in a Horror Campaign:

Every other mech in Lancer is designed like a slasher movie killer or a cosmic horror monster. But Harrison Armory's Napoleon frame is Final Girl coded. Wearing this suit of powered armor guarantees that you will survive to see the end credits. Every scary thing that a GM could throw at you, you'll be able to say "Nuh Uh" to:

"You'll have to dismount from your mech in order to access the control room!"

Nope, you're Size 1/2. Whatever wants to kill you is going to have to get through your armor.

"The crazed space-pirate can inflict 20 points of damage in one hit thanks to their ship-killer cannon!"

Thanks to Heavy Shielding and Flash Aegis that's probably going to be reduced to 1 point of damage. Maybe even less if Stasis Bolt is active.

"The MONIST class entity can hack any electronic device, even your mech, and turn it against it's user!"

Can't hack a brick, which is what the Napoleon become when you Activate Aegis. Also you'll only be taking 1 point of damage, thank you... maybe even less thanks to Stasis Bolt.

"Your Friend is going to be murdered right in front of you!"

Your Stasis Barrier mildly disagree. Stasis Generator and Blinkshield vehemently and in the strongest terms disagrees. Stasis Bolt is in the back, shaking its figurative head disapprovingly, but it's not clear if it's actually going to do anything. But if your friends DO die, that's fine, it's necessary for the narrative, can't have a horror movie without a body count.

"I'm sorry but the Displacer isn't that great..."

What happened to the other guy? Whatever. That's a great point to end on. Look, the Napoleon's Displacer is not supposed to be used at the start of the movie, when your friend hears something and says "I'm going to go check it out, brb." It's supposed to be used after the killer has taken so much damage that his mask has been ripped off, he's bleeding out, and he wants to score one last kill. It is the gas tank rigged to explode. It is the dead cop's shotgun with one last shell in the chamber. It is the big red self destruct button that sets off an ominous countdown.

In conclusion: The Napoleon is for you if you want to survive in the most dramatic way possible.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

#stupid Napoleon and Josephine coded characters#this made my nerd history brain laugh for a good minute enjoy

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films Watched in 2024: 99. The Mummy's Curse (1944) - Dir. Leslie Goodwins

#The Mummy's Curse#Leslie Goodwins#Lon Chaney Jr.#Peter Coe#Virginia Christie#Kay Harding#Dennis Moore#Martin Kosleck#Kurt Katch#Holmes Herbert#Napoleon Simpson#Ann Codee#The Mummy#Universal Monsters#Classic Horror#Films Watched in 2024#My Edits#My Post

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Given that you are more knowledgeable than me in these matters, how problematic adopting a child during the Napoleonic Era was? And let's say, a child was born from a secret affair, what would have happened if it was discovered? What kind of issues the wife and the child would have encountered? Lastly, how hard would have been for the real biological father to adopt their child, after the death of the supposed father?

Feel free to contradict me if I say anything nonsensical; once again, I’m not infallible.

The short answer: I have no idea about adoption. During napoleonic era if the wife were caught in flagrante delicto with an adulterous child, the husband could, in addition to requesting a divorce, have the wife imprisoned, and it’s possible that the court would grant the husband’s request since adultery for a women is punishable by a prison sentence while the husband will only be entitled to a fine . (This is why I think that Jacques-Marie Botot, despite becoming bitter towards Sophie, the widow Momoro, according to some sources, because he fell from disgrace during napoleonic era, still had enough decency to let her go with her lover and not cause her trouble. The fact that she had a child by her lover and was not pursued by the police might be why Botot never mentioned in his records that he had divorced his wife, among other things but like I said before it was not the villain Sophie or the villain Jacques-Marie, I think the wrongs were shared). The child would have lost much of their inheritance.

Well, the third response is very complicated, as you’ll see in the long answer I’m about to give. But yes, the father can acknowledge his child, although there are several obstacles and issues with that, even though he will have certain prerogatives.

By the way, for some courts under Bonaparte, there was an estimation that children from adulterous relationships were considered "monstrosities in the social order" and a "real calamity for morals," according to the terms of the tribune Lahary. This shows how much this weighed on their shoulders.

Warning: I will discuss the rights of natural children during the Revolution before addressing Bonaparte

Napoleon once said, "Society has no interest in recognizing bastards," and he ordered this in the Civil Code. During the Revolution, some revolutionaries fought to ensure equality between illegitimate and legitimate children. Speaking of Prieur (since this is the origin of the question😊 due to my comment about his goddaughter/daughter in your excellent post ), an interesting point about the city of Dijon is that some of cahiers de doléances, such as those from the Third Estate of Dijon, expressed the desire to improve the conditions (of natural children) so that they would be useful to the state. Others, like those from certain communities of Aix, demanded that they be granted civil and political existence. These demands were realized early in the Revolution: the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen abolished "bastardy," and the law of 12 Brumaire, Year II (1793), granted natural children the same inheritance rights as legitimate children.

On June 4, 1793, Cambacérès, on behalf of the Committee of Legislation, presented a draft decree aimed at granting rights to natural children. In his speech to the Convention, he emphasized the importance of restoring equality that had been destroyed by the old law, asserting that the Convention must "restore the rights to natural children that had been so unjustly taken from them." However, it should be noted that not all revolutionaries agreed on granting rights to natural children.

Cambacérès' draft decree was part of a political will to grant all citizens, including children, their civil rights, regardless of age, gender, or status. This marked a significant step forward, as it recognized rights for children, beings naturally dependent on adults, thus realizing the revolutionary principle that "all men are born free and equal in rights." This initiative fulfilled the promise of 1789.

The question of inheritance rights for natural children was first raised on September 20, 1792, by Léonard Robin, who proposed that they inherit from their parents, though not on equal footing with legitimate children. This debate, centered on inheritance, concerned not only the rights of natural children but also those of their mother and the restrictions imposed by the presumed father.

However, the initial decree by the Committee of Legislation did not go as far. It granted natural children inheritance rights from their father, but with restrictions: if legitimate children existed, they should not be disadvantaged. In 1793, a proposal was made to eliminate the term "bastard," a term seen as insulting, replacing it with "natural child."

Léonard Robin's proposal, on the other hand, went further by granting mothers the exclusive right to designate a father for their child, believing that women were the only ones who could judge paternity. This position sought to protect mothers from the abuses of men trying to claim the inheritance of a child born out of wedlock, particularly those trying to claim a significant inheritance.

However, in August 1793, Cambacérès' new draft rejected the possibility of paternity investigations. This draft prioritized the rights of the father, allowing him to choose whether or not to recognize his natural child, without the mother being able to force recognition. This was based on the idea that paternal recognition should be the free will of the man, not an obligation imposed by the law.

The reasons for this restriction were mainly economic: once natural children had the same rights as legitimate ones, recognition of paternity had significant consequences, especially regarding inheritance and family name. As a result, fathers now had the right to choose whether or not to recognize a child and include them in their family, while mothers remained solely responsible for the child.

Berlier, a member of the Committee of Legislation, justified this position by stating that the mother alone was responsible for the situation of her natural child, as she had not secured a "paternal status" beforehand, meaning a marriage contract. Although Berlier was sympathetic to the suffering of natural children and their mothers under the Ancien Régime, he believed that paternity recognition should remain a father's right to prevent abuses and fraud. He also highlighted the practical and economic consequences of recognition: once a natural child was recognized, they were entitled to a share of the inheritance, which represented a significant "cost" to the father. (This once again shows the limits of revolutionary ideas, and I say this without bashing).

As an example, historian Suzanne Desan, after studying the decisions of the Committee of Legislation and the Court of Cassation between 1794 and 1804, shows that the few natural children whose cases were examined by the authorities were systematically deprived of their rights. Provincial courts strictly applied the law of 12 Brumaire, making it very difficult to recognize paternity. For instance, a 40-year-old woman, Marie-Catherine Dampville, tried to prove her paternity with her deceased father by producing a baptismal certificate and witnesses, but these were deemed insufficient. The law now required more rigorous written proof, such as a marriage promise or demonstration of "continuous care," which she could not provide.

Now let’s return to the subject of Bonaparte, the Civil Code, and the rights of natural children.

Aside from the phrase he said about natural children (it is worth noting that he used the term "bastards," a word considered insulting by the revolutionaries who tried to erase it by using the term "natural children"), here is what Bonaparte said: "As soon as there is a possibility that the child might be the husband's, the legislator must turn a blind eye." But he also says, "There must be a fixed rule to remove all doubts," Napoleon Bonaparte continues. "It is said that this is against morality. No; because if the absolute principle were not adopted, the woman would say to her husband: 'Why do you want to limit my freedom? If you suspect my virtue, you can prove that the child is not yours.' This must not be tolerated. The husband must have absolute power and the right to tell his wife: 'Madam, you will not go out, you will not go to the theater, you will not see such and such a person; because the children you bear will be mine.'"

Now, the legal articles: "A child conceived during the marriage has the husband as its father. The law does not accept exceptions to this paternity, neither the wife’s adultery nor the husband's natural or accidental impotence." The Civil Code, through principles like the wife’s obedience and her obligation to follow her husband, as well as harsher penalties for female adultery, tends to limit women's rights. Paternity presumption and the prohibition of questioning paternity are in effect.

The evolution of paternal rights in France, particularly through the laws of Year II and the 1804 Civil Code, highlights that these laws, which were supposed to offer more rights to natural children, actually reinforced the rights of fathers to the detriment of unmarried mothers and their children. Historians have identified a conflict between equality among children, regardless of their origin, and the father's liberty, with the father generally holding dominion.

Despite these inequalities, the laws of Year II are sometimes considered a precursor to modern fatherhood, emphasizing paternal will rather than biological reality. The 1804 Civil Code, with its presumption of paternity, perpetuated this logic, allowing the father to assert his paternity regardless of biological truth. This legislation, while emphasizing the appearance of a legal union, also strengthened the surveillance of women by their husbands, particularly to prevent non-biological children from being attributed to a father.

Natural children, born out of wedlock, do not have the same inheritance rights as legitimate children and are excluded from their parents' inheritance unless they are legally recognized. The legislation emphasizes social stability and the preservation of public order through the family, which is seen as a foundational pillar of society. The Civil Code reinforces the authority of the father within the family, aiming to restore the order disturbed by the excesses of the Revolution.

In summary: The legitimization of natural children through the marriage of their parents is allowed, which enables them to acquire the same rights as legitimate children. However, this legitimization assumes that the parents intended to marry at the time of the child’s birth, which is seen as a means to preserve moral and social order. In contrast, children born of adultery or incest are excluded from any form of legitimization and cannot benefit from family-related rights, as their situation is judged to be too contrary to social order.

In short, the 1804 legislation, while granting some possibilities for reintegration for natural children, primarily seeks to maintain social stability and paternal authority, emphasizing the clear distinction between legitimate and natural children.

Although legitimate children, born within marriage, benefit from full inheritance rights, natural children cannot claim total equality. Their share of inheritance depends on several factors, including the presence of legitimate children or ascendants, and is generally less than that of legitimate children. The 1804 legislation provided specific rules for natural children: in the presence of legitimate children, their share of the inheritance is reduced to one-third of what they would have received if they were legitimate. If the parents have no legitimate descendants or ascendants, their share is larger, up to half of the estate. Some proposals from appellate courts, such as from the Tribunals of Grenoble or Brussels, suggested increasing this share in certain cases, especially if the natural child was the sole heir or if the parents had no legitimate children.

Overall, the 1804 Civil Code recognizes a right to inheritance for natural children, but this right is limited compared to that of legitimate children. This solution aimed to strike a balance between fairness for natural children and the preservation of social order, which favored legitimate families.

Some courts contested a provision of the 1804 Civil Code that limited the inheritance share of natural children, even when they had already received a significant portion of their parents' estate during their lifetime. The Lyon and Bourges Tribunals considered this restriction unjust, as it added an additional inequality to natural children, already deprived of the benefits of legitimacy. Moreover, the legislation prevented parents from making donations or wills in favor of their natural children without reducing their inheritance share, which was also deemed unfair. Some courts called for the advance payment of succession liquidation costs by the heir, so as not to penalize natural children, who were often in precarious situations.

Some lawmakers in 1804 addressed the issue of children born of adultery and incest. Although considered a "monstrosity" and a "calamity for morals" by some, lawmakers felt that these children should not be left in poverty. Figures like Chabot de l'Allier and Siméon insisted that, despite their disapproved birth, these children remained human and deserved pity and support. However, the framers of the 1804 Code did not recognize the rights of adulterine or incestuous children on par with legitimate natural children. They were granted "aliments" (support), but these were strictly regulated and proportional to the parents’ income and the number of legitimate children. Society was required to provide them with support to enable them to lead a useful life, but recognition of their right to a fair share of inheritance was excluded, except in cases of donations or wills that respected the hereditary reserve.

Portalis also stated about natural children, "They belong to no family, but to the State." He also said, "When children, whether natural or legitimate, reach adulthood, they become arbiters of their own destiny; their will suffices." Legislators acknowledged that both children born within marriage and natural children, as long as they had not reached adulthood, deserved protection, particularly in terms of marriage. Parental consent was deemed essential, not only for the public interest but also for the child's welfare, as marriage was seen as a fundamental institution for social and family order. However, natural children, being deprived of legitimate recognition, were considered differently. Some, like Defermon, believed that natural children should be free to dispose of their rights, particularly regarding marriage. However, others, such as Tronchet and Boulay, felt that these children, lacking stable family support, required special protection, especially in contractual matters and marriage. Thus, parental consent was required for minor natural children, and in the event of the parents’ death, a guardian had to be appointed, preventing marriage before the age of 21 without such authorization.

Recognition of paternity was still in place. The father who recognized his natural child had rights over the child's education and, in particular, the right of correction: "The examples of parents, their exhortations, are not always sufficient means to keep certain children, who may have developed vices or bad inclinations, in line with duty: public authority then joins the paternal magistracy, but with precautions compatible with the family’s interest." This is why natural children could not be excluded from measures aimed at overseeing their education and behavior. In particular, the father, whether legitimate or natural, had disciplinary power over his child, including in cases of delinquency. Thus, just as with legitimate children, natural children under the age of 16 could be arrested at the father’s request, by order of the district court president, and imprisoned for up to one month. For children aged 16 to adulthood, detention could be extended to six months, depending on the severity of the situation. This measure aimed to strengthen parental authority and maintain social order, giving fathers the power to control their children's behavior, even when those children were born out of wedlock.

However, don't forget one thing: if the father recognizes his adulterine child from a married couple, the child loses much of their inheritance. Furthermore, as we can see in the post, they are sometimes treated with various insults. So, it’s possible that some fathers may decide to care for them but not recognize them to avoid further problems.

Sources:

Mathilde Larrère

Josée Bloquet

The Civil Code

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

if anyone out here remembers the man from uncle movie, that scene where gaby and illya erotically try to beat the shit out of each other in the hotel room? that's harringrove

#otherwise napoleon is steve coded and illya is billy naturally#it is perfect for whatever ot3 you want as long as two of the 3 are billy and steve#harringrove

15 notes

·

View notes