#Rudolf Rocker

Text

The whole horror of the much-praised capitalist order lies just in this: Without pity and devoid of all humanity it strides across the corpses of whole peoples to safeguard the brutal right of exploitation, and sacrifices the welfare of millions to the selfish interests of tiny minorities.

— Rudolf Rocker

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

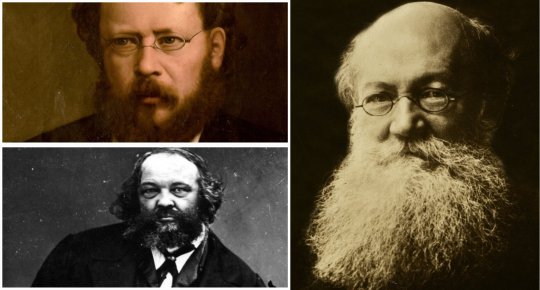

Happy birthday, Rudolf Rocker! (March 25, 1873)

An influential German anarchist, Rudolf Rocker is known for his impact on syndicalist theory, although he never described himself as a syndicalist. Initially a socialist, influenced by his uncle, Rocker joined and campaigned for the Social Democratic Party in Germany before breaking with Marxism and becoming an anarchist. Rocker became known for his close association with the Jewish anarchist community, especially in London, although he was not a Jew himself, and campaigned against antisemitism and pogroms. After some time abroad, after World War I he returned to Germany and helped to organize the Free Workers’ Union of Germany, a syndicalist trade union. As the Nazis took power in Germany, Rocker fled, and ended up in the United States. There, he would continue to write and contribute to anarchist thought and literature while living in the Mohegan Colony, an anarchist commune in New York. He would die there in 1958.

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Wherever Protestantism attained to any influence it revealed itself as a faithful servant of the rising absolutism and granted the state all the rights it had denied to the Roman Church. That Calvinism fought absolutism in England, France and Holland is not significant, for, with this exception: it was less free than any other phase of Protestantism. That it opposed absolutism in those countries is explained by the special social conditions prevailing in them. At its source it was unendurably despotic, and determined the individual fate of men far more completely than the Roman Church had ever tried to do. No other religion has had such a deep and permanent influence on men’s personal lives. [Calvin] continued to convert till nothing was left of humanity.

Calvin was one of the most terrible personalities in history, a Protestant Torquemada, a narrow-hearted zealot, who tried to prepare men for God’s kingdom by the rack and wheel. Crafty and cunning, destitute of all deeper feeling, like a genuine inquisitor he sat in judgment upon the visible weaknesses of his fellowmen and instituted a regular reign of terror in Geneva. No pope ever wielded completer power. The church ordinances regulated the lives of the citizens from the cradle to the grave, reminding them at every step that they were burdened by the curse of original sin, which in the murky light of Calvin’s doctrine of predestination assumed an especially sombre character. All joy of life was forbidden. The whole land was like a penitent’s cell in which there was room only for inner consciousness of guilt and humiliation.... An army of spies infested the land and respected the rights of neither home nor family. Even the walls had ears, for all the faithful were urged to become informers and felt obliged to betray their fellows. In this respect too, political and religious 'orthodoxy' always reach the same result.

Calvin’s criminal code was a unique monstrosity. The least doubt of the dogmas of the new church, if heard by the watchdogs of the law, was punished by death. Frequently the mere suspicion was enough to bring down the death sentence, especially if the accused for some reason or other was unpopular with his neighbours. A whole series of transgressions which had been formerly punished with short imprisonment, under the rulership of Calvinism led to the executioner. The gallows, the wheel and the stake were busily at use in the 'Protestant Rome,' as Geneva was frequently called. The chronicles of that time record gruesome abominations, among the most horrible being the execution of a child for striking its mother, and the case of the Geneva executioner, Jean Granjat, who was compelled first to cut off his mother’s right hand and then to burn her publicly because, allegedly, she had brought the plague into the land. Best known is the execution of the Spanish physician, Miguel Servetus, who in 1553 was slowly roasted to death over a small fire because he had doubted Calvin’s doctrines of the Trinity and predestination. The cowardly and treacherous manner in which Calvin contrived the destruction of the unfortunate scholar throws a gruesome light on the character of that terrible man, whose cruel fanaticism is so uncanny because so frightfully calm and removed from all human feeling." - Rudolf Rocker, Nationalism and Culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The growth of technology at the expense of human personality, and especially the fatalistic submission with which the great majority surrender to this condition, is the reason why the desire for freedom is less alive among men today and has with many of them given place completely to a desire for economic security.

-- Rudolf Rocker

#Rudolf Rocker#leftistquotes#book quotes#quotes#quotable#quoteoftheday#book quote#life quote#beautiful quote#quote#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#growth#technology#economics#economy#economic security#class war#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#anti capitalism#antiwork

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin no eran "amoralistas" como algunos de los rumiadores sosos de Nietszche en Alemania que se titulan anarquistas y son bastante modestos con considerarse "super-hombres". No han construido con habilidad una llamada "moral señorial y esclava" de la que toda clase de conclusiones se pueden sacar, pero al contrario se preocuparon de investigar el origen de los sentimientos morales en el hombre y lo hallaron en la convivencia social. Estando lejos de dar a la moral un significado religioso y metafísico, vieron en los sentimientos morales del hombre la expresión natural de su existencia social que se cristalizó lentamente en determinadas conductas y costumbres y servía de pedestal para todas las formas de organización que salían del pueblo.»

Rudolf Rocker: Anarquismo y organización. Ideas, pág. 6. Barcelona, 1982.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dias-de-la-ira-1

#rudolf rocker#proudhon#bakunin#kropotkin#nietzsche#anarquismo#moral#moral señorial y esclava#moral de los señores#moral de los amos#moral de los esclavos#amoralismo#amoralistas#sentimiento moral#conducta#costumbre#organización#super-hombre#superhombre#pueblo#existencia social#formas de organización#amoral#amoralidad#anarquismo y organización#anarquismo individualista#teo gómez otero

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Participation in the politics of the bourgeois states has not brought the labour movement a hairs’ breadth closer to Socialism, but, thanks to this method, Socialism has almost been completely crushed and condemned to insignificance. The ancient proverb: 'Who eats of the pope, dies of him,' has held true in this content also; who eats of the state is ruined by it. Participation in parliamentary politics has affected the Socialist labour movement like an insidious poison. It destroyed the belief in the necessity of constructive Socialist activity and, worst of all, the impulse to self-help, by inoculating people with the ruinous delusion that salvation always comes from above."

- Rudolf Rocker

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Always it is the illusion to which the real essence of man is offered as a sacrifice; the creator becomes the slave of his own creature without ever becoming conscious of the tragedy of this.

Nationalism and Culture, Rudolf Rocker

0 notes

Text

Everybody googling 'what is anarchy' ... Yes ... yes ... welcome to all the best ideas :3

#louis' tattoos#for beginner book recs let me suggest:#Peter Kropotkin - Fields Factories and Workshops#Mikhail Bakunin - God and the State#Rudolf Rocker - Anarchism and Anarcho-syndicalism#and especially#Ursula K. LeGuin - The Dispossessed

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s a purely “extended hc”, but Sirius's fanon leather jacket never was about punk/rocker style for me. I like the idea that his jacket references leather bars (an important phenomenon of gay history), which he initially didn't realise because he wasn't familiar with that scene.

So, the motorcycle, even though modified, is also part of the leather subculture, representing heightened masculinity. Marlon Brando in "The Wild One" had a significant influence on gay men and the representation of masculine gays (Brando himself didn't hide his bisexuality). Leather bars and the leather subculture were about appropriating sexual power, heightened masculinity, and moving away from mainstream sexual culture. Among gay men, leather symbolized a rejection of the stereotypes of effeminacy and passivity that had been associated with homosexuality since the mid-19th century. It was a deliberate move away from the image of the “sweater queens” and embraced a more rugged and masculine aesthetic.

In London during the 70s, there was the famous leather bar The Coleherne, which even had visitors like Rudolf Nureyev (a famous ballet dancer) and Freddie Mercury.

I like this because Sirius also had a pronounced masculinity that he saw as something absolutely normal, and it fits well with him, much more than the idea of him being influenced by punk culture and aesthetic. I mean, of course, canon Sirius never visited leather bars, but if we step a bit into fanon, this influence could be there – hence the motorcycle, the leather jacket, and so on.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

1938 Mercedes-Benz W154

In September 1936, the AIACR (Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus), the governing body of motor racing, set the new Grand Prix regulations effective from 1938. Key stipulations included a maximum engine displacement of three liters for supercharged engines and 4.5 liters for naturally aspirated engines, with a minimum car weight ranging from 400 to 850 kilograms, depending on engine size.

By the end of the 1937 season, Mercedes-Benz engineers were already hard at work developing the new W154, exploring various ideas, including a naturally aspirated engine with a W24 configuration, a rear-mounted engine, direct fuel injection, and fully streamlined bodies. Ultimately, due to heat management considerations, they opted for an in-house developed 60-degree V12 engine designed by Albert Heess. This engine mirrored the displacement characteristics of the 1924 supercharged two-liter M 2 L 8 engine, with each of its 12 cylinders displacing 250 cc. Using glycol as a coolant allowed temperatures to reach up to 125°C. The engine featured four overhead camshafts operating 48 valves via forked rocker arms, with three cylinders combined under welded coolant jackets, and non-removable heads. It had a high-capacity lubrication system, circulating 100 liters of oil per minute, and initially utilized two single-stage superchargers, later replaced by a more efficient two-stage supercharger in 1939.

The first prototype engine ran on the test bench in January 1938, and by February 7, it had achieved a nearly trouble-free test run, producing 427 hp (314 kW) at 8,000 rpm. During the first half of the season, drivers such as Caracciola, Lang, von Brauchitsch, and Seaman had access to 430 hp (316 kW), which later increased to over 468 hp (344 kW). At the Reims circuit, Hermann Lang's W154 was equipped with the most powerful version, delivering 474 hp (349 kW) and reaching 283 km/h (176 mph) on the straights. Notably, the W154 was the first Mercedes-Benz racing car to feature a five-speed gearbox.

Max Wagner, tasked with designing the suspension, had an easier job than his counterparts working on the engine. He retained much of the advanced chassis architecture from the previous year's W125 but enhanced the torsional rigidity of the frame by 30 percent. The V12 engine was mounted low and at an angle, with the carburetor air intakes extending through the expanded radiator grille.

The driver sat to the right of the propeller shaft, and the W154's sleek body sat close to the ground, lower than the tops of its tires. This design gave the car a dynamic appearance and a low center of gravity. Both Manfred von Brauchitsch and Richard Seaman, whose technical insights were highly valued by Chief Engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut, praised the car's excellent handling.

The W154 became the most successful Silver Arrow of its era. Rudolf Caracciola secured the 1938 European Championship title (as the World Championship did not yet exist), and the W154 won three of the four Grand Prix races that counted towards the championship.

To ensure proper weight distribution, a saddle tank was installed above the driver's legs. In 1939, the addition of a two-stage supercharger boosted the V12 engine, now named the M163, to 483 hp (355 kW) at 7,800 rpm. Despite the AIACR's efforts to curb the speed of Grand Prix cars, the new three-liter formula cars matched the lap times of the 1937 750-kg formula cars, demonstrating that their attempt was largely unsuccessful. Over the winter of 1938-39, the W154 saw several refinements, including a higher cowl line around the cockpit for improved driver safety and a small, streamlined instrument panel mounted to the saddle tank. As per Uhlenhaut’s philosophy, only essential information was displayed, centered around a large tachometer flanked by water and oil temperature gauges, ensuring the driver wasn't overwhelmed by unnecessary data.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Participation in the politics of the bourgeois states has not brought the labour movement a hairs’ breadth closer to Socialism, but, thanks to this method, Socialism has almost been completely crushed and condemned to insignificance.

— Rudolf Rocker

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.5 What are some examples of “Anarchy in Action”?

A.5.3 Building the Syndicalist Unions

Just before the turn of the century in Europe, the anarchist movement began to create one of the most successful attempts to apply anarchist organisational ideas in everyday life. This was the building of mass revolutionary unions (also known as syndicalism or anarcho-syndicalism). The syndicalist movement, in the words of a leading French syndicalist militant, was “a practical schooling in anarchism” for it was “a laboratory of economic struggles” and organised “along anarchic lines.” By organising workers into “libertarian organisations,” the syndicalist unions were creating the “free associations of free producers” within capitalism to combat it and, ultimately, replace it. [Fernand Pelloutier, No Gods, No Masters, vol. 2, p. 57, p. 55 and p. 56]

While the details of syndicalist organisation varied from country to country, the main lines were the same. Workers should form themselves into unions (or syndicates, the French for union). While organisation by industry was generally the preferred form, craft and trade organisations were also used. These unions were directly controlled by their members and would federate together on an industrial and geographical basis. Thus a given union would be federated with all the local unions in a given town, region and country as well as with all the unions within its industry into a national union (of, say, miners or metal workers). Each union was autonomous and all officials were part-time (and paid their normal wages if they missed work on union business). The tactics of syndicalism were direct action and solidarity and its aim was to replace capitalism by the unions providing the basic framework of the new, free, society.

Thus, for anarcho-syndicalism, “the trade union is by no means a mere transitory phenomenon bound up with the duration of capitalist society, it is the germ of the Socialist economy of the future, the elementary school of Socialism in general.” The “economic fighting organisation of the workers” gives their members “every opportunity for direct action in their struggles for daily bread, it also provides them with the necessary preliminaries for carrying through the reorganisation of social life on a [libertarian] Socialist plan by them own strength.” [Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-Syndicalism, p. 59 and p. 62] Anarcho-syndicalism, to use the expression of the I.W.W., aims to build the new world in the shell of the old.

In the period from the 1890’s to the outbreak of World War I, anarchists built revolutionary unions in most European countries (particularly in Spain, Italy and France). In addition, anarchists in South and North America were also successful in organising syndicalist unions (particularly Cuba, Argentina, Mexico and Brazil). Almost all industrialised countries had some syndicalist movement, although Europe and South America had the biggest and strongest ones. These unions were organised in a confederal manner, from the bottom up, along anarchist lines. They fought with capitalists on a day-to-day basis around the issue of better wages and working conditions and the state for social reforms, but they also sought to overthrow capitalism through the revolutionary general strike.

Thus hundreds of thousands of workers around the world were applying anarchist ideas in everyday life, proving that anarchy was no utopian dream but a practical method of organising on a wide scale. That anarchist organisational techniques encouraged member participation, empowerment and militancy, and that they also successfully fought for reforms and promoted class consciousness, can be seen in the growth of anarcho-syndicalist unions and their impact on the labour movement. The Industrial Workers of the World, for example, still inspires union activists and has, throughout its long history, provided many union songs and slogans.

However, as a mass movement, syndicalism effectively ended by the 1930s. This was due to two factors. Firstly, most of the syndicalist unions were severely repressed just after World War I. In the immediate post-war years they reached their height. This wave of militancy was known as the “red years” in Italy, where it attained its high point with factory occupations (see section A.5.5). But these years also saw the destruction of these unions in country after county. In the USA, for example, the I.W.W. was crushed by a wave of repression backed whole-heartedly by the media, the state, and the capitalist class. Europe saw capitalism go on the offensive with a new weapon — fascism. Fascism arose (first in Italy and, most infamously, in Germany) as an attempt by capitalism to physically smash the organisations the working class had built. This was due to radicalism that had spread across Europe in the wake of the war ending, inspired by the example of Russia. Numerous near revolutions had terrified the bourgeoisie, who turned to fascism to save their system.

In country after country, anarchists were forced to flee into exile, vanish from sight, or became victims of assassins or concentration camps after their (often heroic) attempts at fighting fascism failed. In Portugal, for example, the 100,000 strong anarcho-syndicalist CGT union launched numerous revolts in the late 1920s and early 1930s against fascism. In January 1934, the CGT called for a revolutionary general strike which developed into a five day insurrection. A state of siege was declared by the state, which used extensive force to crush the rebellion. The CGT, whose militants had played a prominent and courageous role in the insurrection, was completely smashed and Portugal remained a fascist state for the next 40 years. [Phil Mailer, Portugal: The Impossible Revolution, pp. 72–3] In Spain, the CNT (the most famous anarcho-syndicalist union) fought a similar battle. By 1936, it claimed one and a half million members. As in Italy and Portugal, the capitalist class embraced fascism to save their power from the dispossessed, who were becoming confident of their power and their right to manage their own lives (see section A.5.6).

As well as fascism, syndicalism also faced the negative influence of Leninism. The apparent success of the Russian revolution led many activists to turn to authoritarian politics, particularly in English speaking countries and, to a lesser extent, France. Such notable syndicalist activists as Tom Mann in England, William Gallacher in Scotland and William Foster in the USA became Communists (the last two, it should be noted, became Stalinist). Moreover, Communist parties deliberately undermined the libertarian unions, encouraging fights and splits (as, for example, in the I.W.W.). After the end of the Second World War, the Stalinists finished off what fascism had started in Eastern Europe and destroyed the anarchist and syndicalist movements in such places as Bulgaria and Poland. In Cuba, Castro also followed Lenin’s example and did what the Batista and Machado dictatorship’s could not, namely smash the influential anarchist and syndicalist movements (see Frank Fernandez’s Cuban Anarchism for a history of this movement from its origins in the 1860s to the 21st century).

So by the start of the second world war, the large and powerful anarchist movements of Italy, Spain, Poland, Bulgaria and Portugal had been crushed by fascism (but not, we must stress, without a fight). When necessary, the capitalists supported authoritarian states in order to crush the labour movement and make their countries safe for capitalism. Only Sweden escaped this trend, where the syndicalist union the SAC is still organising workers. It is, in fact, like many other syndicalist unions active today, growing as workers turn away from bureaucratic unions whose leaders seem more interested in protecting their privileges and cutting deals with management than defending their members. In France, Spain and Italy and elsewhere, syndicalist unions are again on the rise, showing that anarchist ideas are applicable in everyday life.

Finally, it must be stressed that syndicalism has its roots in the ideas of the earliest anarchists and, consequently, was not invented in the 1890s. It is true that development of syndicalism came about, in part, as a reaction to the disastrous “propaganda by deed” period, in which individual anarchists assassinated government leaders in attempts to provoke a popular uprising and in revenge for the mass murders of the Communards and other rebels (see section A.2.18 for details). But in response to this failed and counterproductive campaign, anarchists went back to their roots and to the ideas of Bakunin. Thus, as recognised by the likes of Kropotkin and Malatesta, syndicalism was simply a return to the ideas current in the libertarian wing of the First International.

Thus we find Bakunin arguing that “it is necessary to organise the power of the proletariat. But this organisation must be the work of the proletariat itself … Organise, constantly organise the international militant solidarity of the workers, in every trade and country, and remember that however weak you are as isolated individuals or districts, you will constitute a tremendous, invincible power by means of universal co-operation.” As one American activist commented, this is “the same militant spirit that breathes now in the best expressions of the Syndicalist and I.W.W. movements” both of which express “a strong world wide revival of the ideas for which Bakunin laboured throughout his life.” [Max Baginski, Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth, p. 71] As with the syndicalists, Bakunin stressed the “organisation of trade sections, their federation … bear in themselves the living germs of the new social order, which is to replace the bourgeois world. They are creating not only the ideas but also the facts of the future itself.” [quoted by Rudolf Rocker, Op. Cit., p. 50]

Such ideas were repeated by other libertarians. Eugene Varlin, whose role in the Paris Commune ensured his death, advocated a socialism of associations, arguing in 1870 that syndicates were the “natural elements” for the rebuilding of society: “it is they that can easily be transformed into producer associations; it is they that can put into practice the retooling of society and the organisation of production.” [quoted by Martin Phillip Johnson, The Paradise of Association, p. 139] As we discussed in section A.5.2, the Chicago Anarchists held similar views, seeing the labour movement as both the means of achieving anarchy and the framework of the free society. As Lucy Parsons (the wife of Albert) put it “we hold that the granges, trade-unions, Knights of Labour assemblies, etc., are the embryonic groups of the ideal anarchistic society …” [contained in Albert R. Parsons, Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis, p. 110] These ideas fed into the revolutionary unionism of the I.W.W. As one historian notes, the “proceedings of the I.W.W.‘s inaugural convention indicate that the participants were not only aware of the ‘Chicago Idea’ but were conscious of a continuity between their efforts and the struggles of the Chicago anarchists to initiate industrial unionism.” The Chicago idea represented “the earliest American expression of syndicalism.” [Salvatore Salerno, Red November, Black November, p. 71]

Thus, syndicalism and anarchism are not differing theories but, rather, different interpretations of the same ideas (see for a fuller discussion section H.2.8). While not all syndicalists are anarchists (some Marxists have proclaimed support for syndicalism) and not all anarchists are syndicalists (see section J.3.9 for a discussion why), all social anarchists see the need for taking part in the labour and other popular movements and encouraging libertarian forms of organisation and struggle within them. By doing this, inside and outside of syndicalist unions, anarchists are showing the validity of our ideas. For, as Kropotkin stressed, the “next revolution must from its inception bring about the seizure of the entire social wealth by the workers in order to transform it into common property. This revolution can succeed only through the workers, only if the urban and rural workers everywhere carry out this objective themselves. To that end, they must initiate their own action in the period before the revolution; this can happen only if there is a strong workers’ organisation.” [Selected Writings on Anarchism and Revolution, p. 20] Such popular self-managed organisations cannot be anything but “anarchy in action.”

#unions#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common to all Anarchists is the desire to free society of all political and social coercive institutions which stand in the way of development of a free humanity.

Rudolf Rocker

— AnarchistQuotes.com

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The dream of the formation of a world empire is not only found in ancient history: it is the logical outcome of all the activities of power, and it is not limited to any specific period.

Though it has gone through many variations, the vision of global domination connects with the rise of new social conditions and has never disappeared from the political horizon...”

— Rudolf Rocker

#Rudolf Rocker#leftistquotes#book quotes#quotes#quoteoftheday#book quote#life quote#beautiful quote#quote#quotable#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#jewish antizionism#antizionist#antinazi#antiauthoritarian#anti capitalism#antifa#antifascist#anti slavery#anti colonialism#anti cop

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Si los portavoces del nacionalismo fuesen capaces todavía de un mejor conocimiento, el desarrollo de las cosas en el último siglo les habría tenido que mostrar claramente que todas sus aspiraciones se basan en un completo desconocimiento de los hechos políticos y sociales y que especialmente son una ficción vacía para los pueblos menores. En realidad, ¿qué significación tiene el sueño de una soberanía nacional y de una llamada independencia nacional en la época de una ilimitada política de fuerza de los grandes Estados, que intentan subordinar siempre los Estados menores a sus esferas de poder y utilizarlos como vasallos de sus propios intereses? La mayor parte de las nacionalidades menores que han obtenido su supuesta independencia nacional, favorecidas por la momentánea traslación de las condiciones del poder en Europa, han pasado de ese modo de la lluvia al chaparrón. Su soberanía política no les ha proporcionado ninguna protección contra las pretensiones de los grandes Estados y no ha hecho sino volver más opresiva a menudo su situación. La casta de sus nuevos gobernantes y políticos profesionales puede haber logrado alguna ventaja de la unidad nacional, pero para los pueblos mismos la situación general no ha mejorado.»

Rudolf Rocker: Nacionalismo y cultura. Ediciones La Piqueta, pág. 711. Madrid, 1977.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#rudolf rocker#nacionalismo y cultura#nacionalismo#soberanía nacional#soberanía política#independencia nacional#unidad nacional#estado#estados#grandes estados#estados menores#gobernantes#políticos#políticos profesionales#casta política#poder#esferas de poder#europa#subordinación#anarquismo#teo gómez otero#fermin rocker

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malatesta is easily my fav!

#read malatesta#also Rudolf Rocker#and Bookchin#but like bookchin with a critical lens#still some good thoughts but his latter program def deviates from anarchism

0 notes