#Textile Rolling Machine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why Quality Matters When Selecting Mat Rolling Machine Suppliers

With the rise in demand for the rolling of mats, carpets and other materials, mat rolling machines have become essential in companies that require these services. Choosing a supplier for mat rolling machines is critical to the textile, gym equipment and industrial matting businesses because it determines their quality of production and efficiency of operations. These suppliers directly determine the quality of the machines which influences performance, maintenance costs and most importantly, durability. If you are looking for Mat Rolling Machine Suppliers, Dashmesh Jacquard & Powerloom is one of the leading & registered manufacturer, supplier eligible under T.U.F.S. for weaving and allied machinery like looms, jacquards, warping, winding & rolling machine.

#Mat Rolling Machine Suppliers#Mat Rolling Machine Suppliers in India#Mat Rolling Machine#textile machine#best rapier loom machine manufacturers#carpet weaving machine manufacturers

0 notes

Text

“By 1900 child mortality was already declining—not because of anything the medical profession had accomplished, but because of general improvements in sanitation and nutrition. Meanwhile the birthrate had dropped to an average of about three and a half; women expected each baby to live and were already taking measures to prevent more than the desired number of pregnancies. From a strictly biological standpoint then, children were beginning to come into their own.

Economic changes too pushed the child into sudden prominence at the turn of the century. Those fabled, pre-industrial children who were "seen, but not heard," were, most of the time, hard at work—weeding, sewing, fetching water and kindling, feeding the animals, watching the baby. Today, a four-year-old who can tie his or her own shoes is impressive. In colonial times, four-year-old girls knitted stockings and mittens and could produce intricate embroidery; at age six they spun wool. A good, industrious little girl was called "Mrs." instead of "Miss" in appreciation of her contribution to the family economy: she was not, strictly speaking, a child.

But when production left the houschold, sweeping away the dozens of chores which had filled the child's day, childhood began to stand out as a distinct and fascinating phase of life. It was as if the late Victorian imagination, still unsettled by Darwin's apes, suddenly looked down and discovered, right at knee-level, the evolutionary missing link. Here was the pristine innocence which adult men romanticized, and of course, here, in miniature, was the future which today's adult men could not hope to enter in person. In the child lay the key to the control of human evolution. Its habits, its pastimes, its companions were no longer trivial matters, but issues of gravest importance to the entire species.

This sudden fascination with the child came at a time in American history when child abuse—in the most literal and physical sense—was becoming an institutional feature of the expanding industrial economy. Near the turn of the century, an estimated 2,250,000 American children under fifteen were full-time laborers—in coal mines, glass factories, textile mills, canning factories, in the cigar industry, and in the homes of the wealthy—in short, wherever cheap and docile labor could be used. There can be no comparison between the conditions of work for a farm child (who was also in most cases a beloved family member) and the conditions of work for industrial child laborers. Four-year-olds worked sixteen-hour days sorting beads or rolling cigars in New York City tenements; five-year-old girls worked the night shift in southern cotton mills.

So long as enough girls can be kept working, and only a few of them faint, the mills are kept going; but when faintings are so many and so frequent that it does not pay to keep going, the mills are closed.

These children grew up hunched and rickety, sometimes blinded by fine work or the intense heat of furnaces, lungs ruined by coal dust or cotton dust—when they grew up at all. Not for them the "century of the child," or childhood in any form:

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.

Child labor had its ideological defenders: educational philosophers who extolled the lessons of factory discipline, the Catholic hierarchy which argued that it was a father's patriarchal right to dispose of his children's labor, and of course the mill owners themselves. But for the reform-oriented, middle-class citizen the spectacle of machines tearing at baby flesh, of factories sucking in files of hunched-over children each morning, inspired not only public indignation, but a kind of personal horror. Here was the ultimate "rationalization" contained in the logic of the Market: all members of the family reduced alike to wage slavery, all human relations, including the most ancient and intimate, dissolved in the cash nexus. Who could refute the logic of it? There was no rationale (within the terms of the Market) for supporting idle, dependent children. There were no ties of economic self-interest to preserve the family. Child labor represented a long step toward that ultimate "anti-utopia" which always seemed to be germinating in capitalist development: a world engorged by the Market, a world without love.”

-Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women

611 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newsies AU where it's 1899 but none of the boys are newsies; they have other period-appropriate jobs instead.

Jack is a stableboy. He mucks out the stalls and sings to the horses while he brushes them.

Crutchie is a bootblack, so he doesn't have to walk too much.

Albert is a telegraph messenger. His crew is feuding with the Western Union messengers, who knock them off their bikes when they see them.

Buttons and Finch both work in a textile factory. Finch is always getting in trouble for going too slow. Last year, Buttons caught two fingers on his right hand in a machine and lost them, but he's healed up now and is faster than Finch again.

Elmer helps his ma and siblings roll cigarettes in their tenement.

Mush repairs shoes.

Romeo works at a laundry next to a brothel. All the ladies are really nice to him when they see him.

Specs is the lookout for a gang of older boys who are housebreakers. They give him a cut of their take. He has been in the Refuge six times.

Jojo is apprenticed to an illiterate jeweler, and does the books. His boss beats him if he thinks he's made a mistake.

Racetrack is an oyster shucker. He has never seen a pearl.

Albert seems to know everyone in Lower Manhattan, but most of the other boys are lonely. Buttons and Finch aren't allowed to talk at work. Kids steer clear of Specs. Crutchie once saved Romeo from getting soaked by some toughs and now he sometimes says hi when he sees Crutchie set up on the corner, but none of the rest of them are even friends.

#history is depressing#idk whats wrong with me#newsies#livesies#newsies au#newsies fanfiction#child labor au#bonnie's newsies aus#newsies headcanons

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art References for Chapter One of underneath the sunrise (show me where your love lies)

(aka this is the nerdiest thing I've done for this fandom)

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1560

"Monty didn’t know what it felt like to fly through the air, the wind between your wings, the sun kissing your skin, until now. He didn’t know what it felt like for the wax to burn away and melt itself into your skin, searing your flesh, until now.

And he didn’t know why anyone would risk such a thing until now.

Until them."

The Two Fridas, Frida Kahlo, 1939

"How the fuck is Monty supposed to reply when he finally has the thing that he’s ached for so long and he can’t even enjoy it? When his heart is ratcheting up his throat, a ticking time bomb that Frida Kahlo would adore?"

Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymous Bosch, 1490-1510

"Monty is being torn apart in the hell panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights. He is some abomination that Bosch dreamed up to fill the inferno, to be tortured for all eternity, because both of the only two things that Monty has ever loved are being ripped from his trembling fingers by his mother and used against him, just because she can’t handle the fact that he wanted something, anything, to call his own."

Textiles of South Asia (Fictional Exhibit, but here are photos of the clothing in question)

"But mostly, Monty spent his time drinking in Edwin’s knowledge, the way that that he went into professor-mode when explaining the symbolism behind certain artworks. Monty devoured the bits about artwork that Charles knew about, like a discussion in the Textiles of Southern Asia special exhibit where Monty had the privilege of seeing Charles get excited explaining the differences and purposes of lehengas and saris and sherwanis. The way that though they were surrounded by masterpieces, all Monty could stare at is the two muses in the middle of the room, holding hands, more breathtakingly beautiful than any of the painting surrounding them."

Lehenga

Sari (Maharashtraian sari)

Sherwani (Painting of the last Nizam of Hyderabad)

Snow Storm, J. M. W. Turner, 1842

"His fingers catch under Monty’s jaw, guiding Monty’s mouth to his like a brushstroke of lightning hitting the mast of a J. M. W. Turner ship, all storm, all sensation"

I will post another archival set for chapter 2- we've got plenty more coming!

@deadboy-edwin @icecreambrownies @anonymousbooknerd-universe @ashildrs

@tragedy-machine @just-existing-as-you-do-blog @orpheusetude @mj-irvine-selby

@pappelsiin @itsbitmxdinhere @rexrevri @sweet-like-h0ney-lavender @saffirez

@the-ipre @sunnylemonss @days-light @agentearthling @helltechnicality

@sethlost @catboy-cabin @secretlyafiveheadeddragon @vyther15

@anything-thats-rock-and-roll @queen-of-hobgobblers @every-moment-a-different-sound

@nix-nihili @mellxncollie @tumblerislovetumblerislife @lemurafraidofthunder

@likemmmcookies @wr0temyway0ut

#art history references#listen this is so niche#dead boy detectives#monty the crow#monty finch#edwin payne#charles rowland#ghostcrow#cricketcrow#montwin#fanfic#my fics#aletterinthenameofsanity#ao3#frida kahlo#j m w turner#pieter bruegel the elder#icarus#hieronymous bosch#didn't know they were dating au#art references

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a recent afternoon, a dressmaker named Sergio Guadarrama rummaged through a pile of fabric. He and his partner had converted the living room of their home, in Hudson, New York, into a bridal atelier. Rolls of satin were stacked under a worktable; a mannequin in a strapless gown made of Chantilly lace stood near an armoire. Scattered around were five sewing machines and hundreds of yards of organic linen, greige hemp canvas, ombré silk brocade, and all manner of other textiles. Guadarrama had the look of a man at ease—leather slippers, a loose denim shirt, and a big, bright smile—though his eyes betrayed a hint of exhaustion. After a few minutes, he found what he was searching for and held it up: a swatch of vintage flower-printed silk voile from Christian Dior. “This one is to die for!” he said.

The Dior fabric would be sewn into a custom wedding dress for a twenty-five-year-old bride-to-be, Keelie Verbeek, who had just driven down from New Hampshire. Verbeek arrived at Guadarrama’s house with her sister, her mother, two pairs of high heels, and her mother’s wedding gown (bespoke, purchased at a bridal shop in Cicero, New York, in the eighties), which she wanted to incorporate into her own dress, somehow. Guadarrama suggested that he could remove tiny pearls from the old gown’s surface and sew them onto the new one. “I can kind of sprinkle them in,” he said. Verbeek nervously glanced at her mother, who shrugged. Then she disappeared into Guadarrama’s bathroom for her first fitting, with a prototype made from cotton muslin. Kade Johnson, Guadarrama’s business partner and fiancé, cautioned, “We had to leave the toilet seat up, because the cat pees in the toilet here.”

A few minutes later, the bride emerged. Guadarrama eyed her up and down, took some measurements, made a few quick alterations, and then began to pepper her with questions about her bra. The dress, which cost nearly thirteen thousand dollars—typical for a couture bridal gown—would require six fittings in all.

As Verbeek changed back into her street clothes, the conversation turned to other elements of the wedding, which was going to be held, in eleven months, at the former estate of the sculptor Daniel Chester French, in the Berkshires. The reception would feature biodegradable confetti, small-batch Albanian olive oil, and, as Verbeek put it, “emotional-support chocolate.” Although she had already picked most of her wedding venders, including a celebrity makeup artist—recommended by Guadarrama—and a hairdresser from Maryland, she still needed a florist and a photographer, she said, and had been browsing the Knot, a popular wedding-planning platform. In addition to hosting gift registries and wedding websites, and offering reception ideas and relationship advice (“What to Know About Walmart Wedding Cakes,” “How to Prepare for Sex on Your Wedding Night,” “Dislike Your Spouse’s Last Name? Here’s What to Do”), the Knot is used by millions of couples to find their wedding venders, who pay to advertise on it. When Verbeek mentioned the Knot, Guadarrama shook his head and frowned.

“Should I not do that?” Verbeek asked.

“They’re doing some baaaad, shady stuff behind the scenes,” Guadarrama said. He started to explain, but the bride told him that she was running late for her next appointment, at the venue. She needed to decide whether to order custom floating lily pads for the fish pond, and to review where the turreted sailcloth tent and dance floor would be constructed.

After the bridal party left, Guadarrama and Johnson sat down at their dining table and told me that before coming to Hudson they had run an atelier in Manhattan. “We were having success after success after success,” Guadarrama said. They had dressed Kesha, JoJo, Tiffany Haddish. For the 2019 Tony Awards, they made Billy Porter a velvet Elizabethan gown from actual Broadway stage curtains. After a financial setback, the couple decided to move upstate and begin again—right as the pandemic all but shut down the bridal industry. Business tanked. On a chilly winter day in 2022, a saleswoman from the Knot called Guadarrama, in response to a form he’d filled out online. If he signed up for a premium advertising package, the saleswoman said, he could expect between eighty and two hundred and forty brides to contact him each month. Johnson thought this sounded implausible, but, despite his misgivings, the couple signed a yearlong advertising contract with the Knot, for five thousand eight hundred dollars. “We were looking at the Knot as a beacon of hope,” Johnson told me. “And it was the complete opposite.”

Guadarrama said, “The Knot was, like, the final nail in the coffin.”

Couples who are getting married tend to hear the same advice over and over: “Get good at forgiveness.” “Learn the wisdom of compromise.” “Don’t forget to chill the champagne.” When it comes to the wedding itself, the National Association of Wedding Professionals insists that every reception is better with balloons. The Association of Bridal Consultants recommends stocking extra toilet paper, just in case. If you want a quick cure for a rehearsal-dinner hangover, you can hire registered nurses to arrive with the hair and makeup professionals, carrying I.V. bags infused with vitamins or anti-nausea medicine. Cold feet? A man from Spain might be available to crash your wedding. (Going rate: five hundred euros.) “I’ll show up at the ceremony, claim to be the love of your life, and we’ll leave hand in hand,” he told a Spanish TV station. Marcy Blum, a wedding planner who has orchestrated celebrations for LeBron James, members of the Rockefeller family, Bill Gates’s oldest daughter, and, once, a woman who demanded that no other brides be present in the same Italian town on the day of her ceremony, told me, “I will spend whatever it takes of my client’s money to make sure there’s enough bartenders before I’ll put a flower on the table.”

Each year, Americans drop roughly seventy billion dollars hosting weddings. Most people think that this is too much—that couples are overspending, that venders are overcharging, and that the wedding-industrial complex verges on unethical. After all, many weddings are excessive and wasteful. (In New York City, the average cost is eighty-eight thousand dollars.) The wedding planner Colin Cowie, whose clients range from Tiësto (“Happily married,” Cowie boasted) to Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck (“I get them down the aisle fabulously, but they’re on their own thereafter”), told me that he hires hundreds of venders for every event: invitation managers, shoe-check attendants, babysitters, ice carvers, drone operators, and caviar servers. “Once, we built a church,” he said.

Even more modest affairs can involve a phalanx of venders; the average number brought on per wedding is fourteen. These small-business owners often begin as amateurs pursuing a side gig: students moonlighting as wedding photographers, cashiers doing calligraphy after work. Typically, surges of new venders follow layoffs in corporate America. “People cash in their 401(k)s, and they start a business,” Marc McIntosh, a wedding guru who regularly speaks at conferences like WeddingMBA, told me. “A lot of people go into this industry because they’re good at something—they bake good cakes, and their family says, ‘You should go into the wedding-cake business!’ ” But being good at something doesn’t mean you’re good at running a business. And running a wedding business is especially tough: there are hundreds of thousands of competitors; costs are rising, owing in part to inflation; and, for many venders, bookings and budgets have decreased by about twenty-five per cent. According to a recent industry survey, a third of all wedding venders said that they are doing poorer financially than they were a year ago. “Florists are the worst,” McIntosh said. “There are so many broke florists.”

A reliable way for a florist to avoid going broke used to be by advertising in glossy magazines like Brides or Martha Stewart Weddings. By the early two-thousands, wedding marketing, like everything else, was increasingly shifting online. When Blum started her planning business, in Manhattan, in 1987, she took out a small ad in New York. Ten years later, she had become the city’s unofficial wedding czar, and four friends who’d met at N.Y.U.’s film school approached her for advice. “They were, like, ‘We’re going to start this website about weddings,’ ” Blum recalled. “And I said, ‘That’s the cutest thing that I’ve ever heard. Let me introduce you to everybody.’ ” The website was the Knot, and the four friends created it with about one and a half million dollars in seed funding from AOL. “In those days, it was a joke,” Blum said.

Within a few years, the Knot was a juggernaut—the Yellow Pages of the wedding industry. By 1999, when it went public, two of the company’s co-founders, Carley Roney and David Liu, who are married, had become veritable wedding moguls. The couple started a reality show about wedding planning, launched a magazine, and purchased weddingchannel.com, an online bridal registry. Roney appeared regularly on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and “The View.” In an episode during Season 2 of “The Apprentice,” contestants raced to open a bridal shop and sell wedding dresses. One team spent its entire marketing budget with the Knot—and won. “Our phone went off the hook after that,” Liu told me. “I’m almost ashamed, but, like, some of our success has to be attributed to idiot Trump and that show.”

In 2018, XO Group, the Knot’s corporate parent, was acquired by its biggest competitor, a company called WeddingWire, in a private-equity-backed deal worth almost a billion dollars. By then, Roney and Liu were out. The Knot Worldwide became a privately held company.

Last year, the Knot facilitated four billion dollars in consumer spending via advertising on its platforms. Most of the company’s revenue comes not from brides and grooms but from wedding venders. Nine hundred thousand venders in more than ten countries use the Knot, and many pay to be advertised to couples—“leads,” in industry parlance—seeking their services. Ronnie Rothstein, who, at eighty-two years old, is the C.E.O. of Kleinfeld Bridal, one of the largest wedding-dress retailers in America and a mainstay on the reality show “Say Yes to the Dress,” told me, “Every wedding vender needs a qualified lead.” He went on, “Most of these businesses are family businesses, and they need help to get as many people into the door as possible.”

After Guadarrama signed his advertising contract with the Knot, he started receiving a flood of inquiries from couples. Many of the messages seemed bland or formulaic. “Hello—we are getting married,” one groom wrote. A bride asked, “Could you send over some more info about the products and services you offer?” Guadarrama always responded immediately, and repeatedly followed up. At first, he was optimistic. But, week after week, he never heard anything in return.

Curious to learn more about the vender experience, and being a weekend cake baker myself, I decided to fill out a vender contact form on the Knot’s website to get some basic information about the contract terms. A Knot representative soon called me. She was encouraging about the brides and grooms who would be spending money on my fictitious wedding operation. “People do go over budget sixty-two per cent in your particular area,” she said. After a long discussion about pricing and placement, she said that, if I wanted to take my business to the next level, a twelve-hundred-dollar-per-month advertising package might be appropriate. (Later, the Knot characterized this call as an attempt to “entrap and bait our salesperson” and accused me of being “ethically challenged.”) I also spoke at length with dozens of wedding venders across the United States. David Sachs, a wedding photographer in Northern California, started advertising with the Knot in 2016, after giving up on becoming an actor. “The Knot was the biggest directory at the time, so I figured I would just do what everyone else was doing,” Sachs told me. Initially, he got some clients from the site. “Sales were higher than expenses, and that was good enough for me,” he said. But after a few years brides stopped reaching out, and he called his sales rep to complain. A new, pushier rep talked him out of closing his account and persuaded him to upgrade to the most expensive advertising tier. “I started spending a thousand dollars a month,” he told me. Then a torrent of leads arrived, via the Knot’s online vender portal. Often, he’d talk to the potential customers by phone. “It felt like all the brides were reading from a script,” he said. “I could hear other calls in the background, and they all had the same lilting tone. That’s when I realized, they have a literal phone bank of people who are faking leads.”

When I asked the Knot about this, a spokeswoman said, “We do not tolerate fraudulent practices.” She went on, “The Knot Worldwide does not employ any individuals or teams who act as fake couples to send fake leads to venders. We have no financial incentive to engage in such conduct, and it is antithetical to our business.” But more than twenty wedding venders who advertise with the Knot told me that they’ve received inquiries from what they believe are fake brides. Matt Pierce, a wedding photographer in Texas, said that he’d exchanged e-mails with someone who was getting married in a few days. Pierce called the wedding venue, he told me, and the woman who ran it said, “You, too, huh? You’re about the twelfth photographer that’s called here today about a wedding this weekend.” There was no wedding.

Documents I obtained from the Federal Trade Commission reflect that, since 2018, more than two hundred formal complaints have been made about allegedly fraudulent activity on the Knot and WeddingWire. One vender wrote, “I paid around $12,000 and got absolutely nothing to show for it.” Another said, “My business is on the verge of going bankrupt. I would happily pay for the service [if] it was providing me what was promised, but it has not.”

Venders have also shared their grievances on several private Facebook groups, one of which features a stock photo of an enraged bride wielding a pistol. (Sample posts: “Hi! New victim here!”; “I’m in a war with the Knot”; “Can we get together for a class-action lawsuit?”; and “You know what would be more powerful than a lawsuit? A Netflix documentary . . .”) Venders in the group suspected infiltration by Knot employees. A post read, “We found two spies here who worked for The Knot. They know about us. And, they should be scared.” A couple of years ago, an online petition was launched in an effort to spur regulatory action. “This petition is going to congressional leaders,” the organizer wrote. Comments from signatories include:

Mike Cassara, a wedding photographer, influencer, and podcast host, told me that he and his co-host, Lauren O’Brien, regularly receive D.M.s on Instagram from wedding venders who complain about “fake brides” and “bad leads” from the Knot. He told me, “Their stories are endless! If this was five people, I’d question it. If it was ten people, twenty people, even a hundred people, I’d question it. But we’ve had thousands of people saying the same thing: ‘They’re ripping me off.’ ”

As I was reporting this story, the Knot had multiple outside communication firms correspond with me. One of them got in touch through a representative who had a résumé that included “successful presidential pardons” and “hostage and kidnapping recovery.” In the past six months, I contacted more than seventy current and former employees of the Knot, because I wanted to better understand the wedding venders’ claims. Almost all who agreed to speak with me requested anonymity, citing N.D.A.s or fear of retaliation. One former saleswoman said that, after her venders had complained to her about lead troubles, she recognized that many of the leads seemed like they might be fake. But she was working on commission, and it wasn’t in her interest to let clients out of their annual contracts; if she lost too many, she might lose her own job. Bretta Thompson, an Indianapolis-based wedding planner and officiant who advertised on the site, told me, “It was like pulling teeth to get anyone at the Knot to contact me. It would take weeks to get a response back, via e-mail, and then it was always my fault.” Another former saleswoman put it more plainly: “We fucked over venders.” (“We strongly dispute these claims,” the spokeswoman for the Knot said.)

Many venders I spoke with told me variations of the “fake brides” story, and took it upon themselves to conduct investigations, which produced results that were sometimes difficult to verify. Nicole Hobbs, who worked as a wedding photographer in Nashville, said that she had been contacted by people who, upon further inquiry, had already exchanged vows. “I was even able to confirm that one of the ‘grooms’ was actually a married minister in a different state,” she claimed. Darryl Cameron II, a part-time d.j. in Cleveland, Ohio, said that he’d received dozens of fake leads from the Knot. “These folks are real,” he told me. “But I’ve looked several up in the county database, and they’re married already!” Jeffrey Caddell, who owns a wedding venue in Alabama, told me, “All I can say is, it’s very fishy when you have hundreds and hundreds of leads and only a handful of responses.”

In David Mamet’s play “Glengarry Glen Ross,” a beleaguered real-estate salesman explains that he isn’t closing deals because his boss has been giving him bad leads. “I’m getting garbage,” he says. “You’re giving it to me, and what I’m saying is, it’s fucked.” Most leads for most venders in most industries don’t ever amount to anything—it’s hard work chasing down a lead, as any salesperson will attest—and the wedding industry is particularly challenging. Brides are regarded by wedding professionals as fickle and elusive. Marc McIntosh, the wedding guru, told me, “A couple planning a wedding has a to-do list, and everything on that list is something they’ve never bought before, from a company they’ve never heard of before. And they don’t have a lot of time.” Ronnie Rothstein, of Kleinfeld Bridal, said, “When a girl gets engaged, she’s gonna talk to everyone.”

Not every wedding vender hates the Knot. Allison Shapiro Winterton, a wedding-cake baker, considers it a “very honest business.” Steven Burchard, a d.j. and magician who runs a nationwide entertainment company, said that during engagement season—between Thanksgiving and Valentine’s Day—he usually receives about a dozen leads a week from the Knot. He follows up with each of them numerous times, and many do end up booking him. “You’ve gotta remember, there are tire kickers,” he told me. “Is that a fake lead? Or is it just someone who isn’t interested?”

Jeff MacGurn, who owns a wedding venue in the San Jacinto Mountains, told me, “The Knot’s great! And I’m uniquely positioned to comment on that.” In addition to operating the venue, MacGurn works for a digital-marketing firm. “When I’m judging the Knot, it’s not me saying, ‘I think it’s working.’ I know it’s working,” he said. “There’s a return on investment, for sure.” By his estimate, each lead from the Knot costs between twenty-two and thirty dollars. Most couples reach out once, then never again; booking a single wedding might require as much as nine hundred dollars in ad spend. “I can sit here and blame the Knot for bad leads,” MacGurn said. “But oftentimes I would look at my process, and I’d be, like, this is why we’re not closing”—not following up enough, not following up quickly enough, asking a prospective bride too many questions. Other venders, he noted, could stand to improve their tactics.

But, for many venders, so few leads have worked out that their tactics seem beside the point. They believe that the Knot inflates its lead numbers by allowing couples to simultaneously send form-letter inquiries to multiple venders. “People are getting leads that aren’t really for them,” McIntosh told me. “But, when it comes time to renew, the Knot can say, ‘We sent you five hundred leads this year,’ even though only five were really for you.” The company’s spokeswoman explained, “We have a tool that makes it easier for couples to reach out and start a conversation with venders using templatized language.” For instance, if a couple browsing the site decides to ask for a quote from their dream d.j., they will afterward be presented with a pop-up that invites them to send auto-populated messages to several other venders. The spokeswoman cautioned that venders “may misinterpret” such messages as spam, but that “spam is not a widespread problem” and “less than one per cent of leads delivered to venders in the U.S. were reported by venders as spam.”

Rothstein, who has advertised with the Knot for more than two decades, told me he was confident that the company wasn’t intentionally sending bad leads. “We don’t find them to be dishonest whatsoever,” he said. Rather, in recent years, the Knot simply stopped working well for them as a lead-generation platform. “They’ve become less effective,” he said. Jennifer Shipe, Rothstein’s chief marketing officer, said that she could spend Kleinfeld’s advertising dollars better elsewhere. Recently, she had her team manually compare every e-mail that originated from the Knot with the e-mail addresses of brides who booked appointments at their stores. “I don’t think we got anything out of it,” she told me.

Several days after I spoke with Shipe, Rothstein called me back—“I spoke to the Knot today!” he said—and clarified that a few of the leads might have led to appointments, about one tenth of one per cent of them, not zero. “We have a fucking phenomenal relationship with the Knot,” he said. “Neither one of us wants to fuck up that relationship.” He went on, “The leads don’t work, but I get great editorial from them. There aren’t that many magazines anymore. They’re it—numero uno! There’s no place else to go.” Many unhappy venders were reluctant to have me publish their names—or even their stories—in this article, for fear of retaliation by the Knot. Laura Cannon, who runs the International Association of Professional Wedding Officiants, told me, “They dominate the market.” Dozens of Cannon’s members have received suspicious leads from the Knot, but were too scared to say anything publicly. She continued, “You feel like you’re in an abusive relationship. I’ve thought about leaving the wedding industry, because what else can I do? It’s their industry now.”

Recently, I asked Tamas Kadar, the C.E.O. of a fraud-prevention firm, to review a few hundred e-mail addresses associated with suspicious leads from the Knot. He told me, “It seems like ten per cent of them are not real. We look at their digital footprint—their social-media profiles, how old is the e-mail account, does it appear elsewhere on the internet. And for ten per cent of them it’s, like, someone just opened an e-mail account.” Kadar also identified what he described as a significant vulnerability: unlike many other online services, the Knot doesn’t require users to verify their e-mail addresses when they sign up. “You don’t even have to have access to the e-mail account,” he said. “This could be why venders are facing so many nonexistent leads. The Knot doesn’t conduct the right kind of verification to make sure they don’t give fake leads to their customers. This is a basic step.” He went on, “I could just ask ChatGPT Operator to go to this website, type in a fully random e-mail address, and open an account and send a hundred inquiries to random wedding venues.”

Rich Kahn, another ad-fraud expert, told me, “It’s possible they know they have a problem and they’re doing nothing about it. And it’s also possible they don’t know.” Kahn explained that more than twenty per cent of the six hundred and forty billion dollars spent globally on digital marketing each year was effectively stolen via bots and “human fraud farms”—people at computer terminals, often overseas, who generate web traffic and inflate marketing metrics by making fake Facebook profiles, clicking on Google ads, or even sending fake leads. “In digital marketing, a portion of what you’re buying is not a real audience,” he said. “But that’s not a defense. It’s on you to do something about it. If you’re a big brand, you’re supposed to be protecting your clients.”

One night last fall, after a rooftop business mixer at a hotel in Manhattan, a woman in a long, flowery dress looked down at her heels and grimaced. “These puppies are barking!” she said. A few colleagues laughed knowingly. The women, who all worked at a Mississippi dress boutique, had been on their feet for days, at previews and runway shows connected with Bridal Fashion Week. Outside the hotel, as the group waited for their Ubers, one of them turned to a woman standing nearby and, making small talk, asked, “What store do you own?” The woman, Jennifer Davidson, was dressed in a chic black dress and gold-studded heels and carrying a Chanel purse that she had borrowed from a friend for the evening. She replied that she had spent about two decades working at the Knot. The woman from Mississippi laughed, then said that she had closed her Knot account after receiving dozens of dubious leads. “We were, like, ‘There’s no way these are legitimate,’ ” she told Davidson. The woman’s daughter, who co-owns the shop, chimed in: “We still get fake leads! It’d be, like, ‘Can you tell me more about your services?’ And I’d be, like, ‘Well, we’re a bridal store—what do you think we do?’ ”

Davidson, who was for many years one of the Knot’s top salespeople, was not about to defend the company. In 2015, she came to believe that it had been defrauding its biggest advertisers. By her account, the digital ads that she and her colleagues were selling were not reliably showing up on the Knot’s website. Macy’s, David’s Bridal, Kleinfeld Bridal, Justin Alexander, and even the N.F.L., she felt, had together been duped out of millions of dollars. When she alerted a vice-president at the company, John Reggio, who now works at TikTok, he told her that the Knot’s technology was flawed. “The website is duct-taped together,” Davidson recalled him saying. (I repeatedly reached out to Reggio for an interview; he declined, then said, “Please stop emailing me.”)

Davidson’s colleague Rachel LaFera reported the same issue to an executive, who exploded, LaFera recalled. “She grabbed me by both of my arms, and she started shaking the shit out of me, red-faced, spitting, saying, ‘You have to stop, just stop! You’ve got to stop bringing all this up. Stop it!’ ” LaFera said. “I was so in shock.” (When I reached out to the executive for comment, she replied, “😩,” and then said that she had mistook me for someone else. Later, she said that LaFera’s recollection was “untrue.”)

In 2017, Proskauer Rose, a prominent white-shoe law firm, was brought on to investigate the alleged advertising fraud. Executives and employees, including Davidson and LaFera, were interviewed, and the firm found no evidence of “widespread misconduct.” The Knot told me that, in the course of investigating Davidson’s allegations, a “material weakness” was identified in the “internal controls for the national advertising business” which affected approximately a hundred and sixty thousand dollars in ad purchases, and that advertisers were made whole. The Securities and Exchange Commission also conducted an investigation, according to the Knot, “and did not pursue any action.” But Davidson believes that employees lied to government officials and mucked up the S.E.C. investigation. (The Knot said, “There is no evidence to support an assertion that any employees were untruthful.”)

Davidson, LaFera, and Cindy Elley, who is Davidson’s sister and also worked at the Knot—the trio call themselves “the Knot Whistleblowers”—have an end-to-end encrypted e-mail account to field tips. In the past eight years, they say that they have contacted more than a hundred and fifteen current and former employees and secretly recorded many of the conversations with the aim of persuading the S.E.C., and possibly other government agencies, to mount a new inquiry into the company. (If the S.E.C. collects damages from the Knot, the trio stands to make up to thirty per cent of any potential recovery, thanks to a program that rewards whistle-blowers for coming forward.)

I went to visit Davidson at her home, near Charleston, South Carolina. She and I sat on her patio, and she played me several of the recordings, all of which she insists were obtained legally. (“We put our Nancy Drew hats on,” she said.) In one tape, LaFera can be heard chatting with a former Knot executive at a restaurant in New York. The two had met up to share war stories from their time with the company, and LaFera had worn hidden mikes that were taped to her shoulders. “Getting out was the best thing,” the former executive said. Another recording featured a former employee, Dave Harkensee, who oversaw a team of sales reps at the Knot. Harkensee said to Davidson, “We actually send out messages on behalf of these couples that don’t even realize we’re doing it.” He went on, “It’s almost, honestly, gaslighting these venders, saying, ‘Hey, we’re sending you leads. You’re just not able to convert them.’ But it’s actually, like, these are not viable leads. These aren’t legit at all.” (Harkensee denied that this conversation took place. The spokeswoman for the Knot said, “We do not send leads on behalf of couples without their consent.”)

In 2023, the New York Post published an article about Davidson’s initial allegations. “The Knot has been accused of systematically swindling clients for years,” the piece read. Weeks later, Forbes followed up: “How Wedding Giant the Knot Pulled the Veil Over Advertisers’ Eyes.” That year, the trio reached out to the office of Charles Grassley, a U.S. senator from Iowa who is an advocate for whistle-blowers. (Grassley is also known around Capitol Hill as something of a matchmaker. Per the Washington Post: “Forget dating apps. Sen. Grassley’s office has produced 20 marriages.”) Last week, Grassley, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent a letter to the acting chairman of the S.E.C. and the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, asking them about wrongdoing at the Knot. “I have recently been alerted of alleged deceptive business practices by the Knot from several Iowa small businesses that suspect they have been defrauded,” he wrote. “What steps have you taken to investigate the allegations? I would like to know, and I’m sure all these small businesses would as well.”

In the living-room bridal atelier in Hudson, Sergio Guadarrama elaborated on the setback that had led him to the Knot. In 2019, he was cast on the reality show “Project Runway.” The appearance backfired; he came across as a villain, and the dress orders for his business, Celestino Couture, plummeted. “People came up to me randomly in the street and said, ‘Oh, you’re that fucking guy,’ ” Guadarrama recalled. Moving upstate had seemed like the best way to get a fresh start. Then came the pandemic, and then came the Knot.

After signing up, Guadarrama and Johnson sent their first payment to the Knot—about five hundred dollars, money that should have gone toward their rent. “That was a lot of fucking money at the time, especially when we had no money coming in,” Johnson said. They got fifteen leads, but a month went by with no responses. One spring afternoon, Guadarrama called the phone number listed on a lead. He said that the woman who picked up told him, “I never signed up for the Knot! I’m not even getting married. Who are you?”

I contacted all the suspicious leads that Guadarrama had received from the Knot, and only a few people replied. Of those who did, one woman told me that she would not have sent a message to him because she had already bought her dress—and her ex-fiancé lived in Hudson. “It makes zero sense that I would want to go to Hudson,” she said. Then she logged into her account and found that a message had been sent to Guadarrama, likely via the pop-up template outreach feature, which she had forgotten all about. Another woman told me, “I never heard of Celestino Couture.” She wouldn’t have contacted the business, she said, because when Guadarrama received her supposed inquiry she had already made plans to buy a wedding dress in Europe.

Guadarrama tried to cancel his contract with the Knot, but the company refused to let him out of his yearlong commitment. So, like many venders I spoke with, he closed his bank account to prevent the Knot from continuing to withdraw payments. When I asked the Knot about this, the spokeswoman said that “contract terms are clearly disclosed by our sales representatives,” who are “trained to specifically mention that no number of leads are guaranteed.” Other venders told me that they’d cancelled their credit cards; some uploaded banners to their Knot profiles that read “DON’T USE THE KNOT” and filed complaints with the Better Business Bureau.

Carley Roney and David Liu, the company’s co-founders, trace the increasing number of lead complaints to the private-equity acquisition. Liu stepped down from the Knot’s board a few months before the deal. (Roney left the company in 2014.) “We felt like twenty years of our lives had been flushed down the drain,” Liu said.

“It’s a tragedy to us what’s become of our life’s work,” Roney added.

Before the acquisition, the Knot was generating about twenty million dollars in cash flow each year; as part of the deal’s financing, the Knot Worldwide took on hundreds of millions in debt. “To pay the interest on that much debt would essentially cripple a business,” Liu said. Any company in that position would need to cut costs and generate a lot of revenue. Liu wouldn’t comment directly on the allegations of fake leads or fraud, but that kind of financial obligation, he said, would mean that “the experience of the consumers is gonna suffer.” He added, “Who ultimately loses? The brides—and the local venders.”

In March, a Knot employee named Thomas Chelednik addressed a ballroom full of wedding venders at a Hyatt Regency in Huntington Beach, California. He said that the company was not sending fake leads to people, and that he would quit his job if it were. The next day, Raina Moskowitz, the Knot’s new C.E.O., held a virtual town hall. “We’re in a moment where I think celebration and communication and community matter more than ever,” Moskowitz said. She then answered pre-submitted questions, which were read aloud by a colleague: “A planner named Dolly asked, ‘What are you doing to stop the fake leads created by the company and giving false hope to venders?’ ” Moskowitz suggested that the venders were mistaken. “You get a lead, but you don’t hear back—and that can be incredibly frustrating,” she said. “It might be perceived as fake, but I just want to name it as ‘ghosting.’ ” She went on, “It doesn’t feel great, ” and announced that the company is testing a new tool that she hopes will address the problem. (The Knot’s spokeswoman said, “We are continually improving our spam-filter capabilities.”)

Before Guadarrama and Johnson extricated themselves from their contract with the Knot, they were selling their possessions to get by—“our clothes, our shoes, anything that we could,” Johnson told me. But their circumstances have since changed. In 2023, the couple, along with a business partner, opened two slow-fashion boutiques, which have been successful. Their wedding-dress business is, for now, a side hustle. They still chase every lead.

Keelie Verbeek, the twenty-five-year-old bride-to-be, had been window-shopping for chocolates and antique glassware in Hudson when she wandered into one of Guadarrama and Johnson’s boutiques. She tried on a vintage Ulla Johnson dress, as Henry, her fiancé, lingered nearby. The dress wasn’t for her, but before she left Johnson commented on her engagement ring. “Did you know we also make wedding dresses?” he asked.

Verbeek laughed. She had spent six months trawling Instagram, TikTok, Facebook Marketplace, and even the Knot, searching for the perfect dress. As Henry drove them home, Verbeek scrolled through Guadarrama and Johnson’s Instagram page. That afternoon, Guadarrama and Johnson received an e-mail from Verbeek: “I was hoping to be able to book a bridal consultation.” Excited, they followed up immediately, and, to their surprise, someone actually replied.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw a post earlier where someone was talking about the joys of doing crafts/textile/fibre art and it made me want to maybe pick up embroidery again and maybe commit to learning to crochet more than just a granny square (perhaps finish the shawl I started 3 years ago lol) but it's also go me waxing poetic a bit about crafts and fibre arts specifically like I sit and do my little needlepoint and am reminded of the generations of women and others that came before me who also sat and drank tea while doing their needlepoint as well. I wonder how many hands have made these same movements done, these same stitches, stopped to take a break and brew some more tea to let the warmth of the mug warm their hands. I am reminded of sitting on my grandma Margarets rug by my mom's feet as she crocheted/sewed late into the evening, the sound of the sewing machine or crochet hooks clacking softly in the background as she explains how to turn the fabric to get the stitches just so or how to maintain good yarn tension without holding too tightly while handing me a skein of yarn to roll into a ball to keep my hands busy and when I tired of that handing me a soft ball of yarn and a crochet hook to practice doing chains of whatever stitch she had shown me that struck my fancy at the time. I wonder how many children through the ages have fallen asleep to the soft sounds of someone lovingly making something soft and warm, how many little hands have wound up balls of yarn while sitting by their mother's feet as I did.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

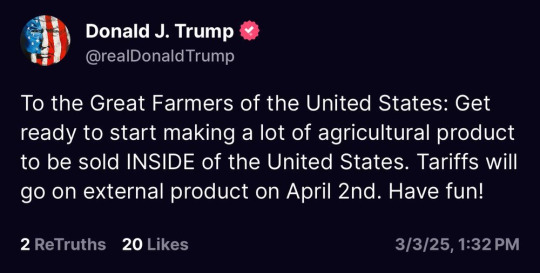

Donald fucked around, we get to find out

Via Narcity: "Starting Tuesday, Canada is slapping new counter-tariffs on U.S. products, targeting $30 billion worth of American goods. And that's just the beginning — Trudeau says an additional $125 billion in tariffs will roll out in the next three weeks if things don't de-escalate."

What follows is the full list of affected American products:

Food & drink

Poultry & eggs — chicken, turkey, goose, duck and their byproducts (fresh, frozen, preserved)

Dairy products — milk, cream, butter, ice cream, yogurt, cheese

Fruits & vegetables — tomatoes, beans, snap peas, citrus fruits, melons, peaches, nectarines, berries

Coffee & tea

Spices & flavourings — pepper, vanilla, dried spices (cinnamon, turmeric, curry, etc.)

Sauces & condiments — soy sauce, ketchup, mustard, mayonnaise, salad dressing, peanut and nut butters

Grains & baking essentials — wheat, rye, rice, barley, oats, flour, mixes and doughs

Oils & fats — canola, sunflower, safflower, palm, peanut and nut oils; margarine and butter substitutes

Sugars & sweeteners — honey, cane sugar, beet sugar, maple sugar and syrup, sugar syrups, molasses

Packaged foods — pasta, pizza, bread, cakes, biscuits, cereal-based foods, soup and broth, pickles, gum, candies, chocolate

Supplements — whey powder, casein, fish oil

Beverages & alcohol — orange juice, soda beer, wine, cider, spirits, liqueurs, coolers, bitters

Tobacco products

Raw & processed tobacco — unmanufactured tobacco, tobacco extracts, chewing tobacco, pipe tobacco

Cigarettes & cigars — cigars, cheroots, cigarillos and cigarettes

Nicotine products — vapes, e-cigarettes, nicotine patches and other smokeless tobacco products

Personal care products

Cosmetics & skincare — makeup, nail polish and manicure tools, hair care, deodorants, soaps and cleansers, razors, shaving products, bath products

Electronic tools — electric razors and clippers, hair dryers, curling irons, flatirons

Fragrances — perfumes, room deodorizers

Oral care — toothpaste, dental floss

Paper products — toilet paper, tissues, napkins

Home & office items

Kitchenware — paper and plastic tableware, storage containers, glassware, cutlery and utensils, kitchen knives, scissors

Furniture & home goods — metal, wooden and plastic furniture; chairs; mattresses and bedding; lighting; storage racks

Home textiles — carpets, rugs, blankets, bed linens, table and kitchen linens, curtains, cleaning cloths

Paper & books — stationery, notebooks, memo pads, binders, file folders, carbon sets, albums, printed materials

Office supplies — letter openers, pencil sharpeners

Artwork — paintings, drawings, pastels

Clothing & accessories

Clothing — shirts, pants, dresses, suits, underwear, hosiery, pyjamas, sweaters, activewear, swimwear, outerwear, baby clothes

Activity-specific attire — diving suits, ski suits, protective gear, life jackets, climbing harnesses, work belts, safety headgear, animal saddlery

Accessories — footwear, hats, gloves, scarves, belts, neckties, jewelry

Bags & luggage — handbags, wallets, suitcases, briefcases, backpacks

Electronics & appliances

Household appliances — refrigerators, freezers, dishwashers, washing machines and dryers, stoves, barbecues, fans, humidifiers, vacuum cleaners, fabric steamers

Countertop appliances & kitchen gadgets — blenders, food mixers, juicers, microwaves, grills, rice cookers, coffee makers, toasters

Gaming & entertainment — video game consoles, board games, card games

Vehicles & machinery

Motorcycles & recreational vehicles — motorbikes, sidecars, recreational boats, drones

Yard equipment — snowblowers, lawnmowers

Tools — saws, pliers, wrenches, spanners, hammers, drills, cutting tools, screwdrivers, staple guns, vices, lighters, pneumatic tools, padlocks

Rubber tires

Building materials

Silica & quartz sands

Plastic wall, floor & ceiling coverings

Window and door fixtures — window and door components and frames, shutters, blinds

Bathroom fixtures — plastic and ceramic baths, showers, sinks and wash basins, toilets, bidets, urinals

Plastic packaging

Wood products — planks, chips, veneer sheets, particle board, MDF, fibreboard, laminated wood, posts, beams, floor panels, wood pulp

Cardboard & paper — cartons, boxes, cases, paper bags

Textiles — tarps, tents, canopies, sails, woven fabric

Precious metals & gemstones — diamonds, silver, palladium

Weapons & ammunition

Firearms — pistols, revolvers, rifles, shotguns, air guns

Ammunition — bullets, cartridges, pellets

"Have fun!"

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Impact of the British Industrial Revolution

The consequences of the British Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) were many, varied, and long-lasting. Working life in rural and urban settings was changed forever by the inventions of new machines, the spread of factories, and the decline of traditional occupations. Developments in transportation and communications meant life in the post-industrial world was more exciting and faster, with people more connected than ever before. Consumer goods became more affordable to more people, and there were more jobs for a booming population. The price to pay for progress was often a working life that was noisy, repetitive, and dangerous, while cities grew to become overcrowded, polluted, and crime-ridden.

The impact of the Industrial Revolution included:

Many new machines were invented that could do things much faster than previously or could perform entirely new tasks.

Steam power was cheaper, more reliable, and faster than more traditional power sources.

Large factories were established, creating jobs and a boom in cotton textile production, in particular.

Large engineering projects became possible like iron bridges and viaducts.

Traditional industries like hand weaving and businesses connected to stagecoaches went into terminal decline.

The cost of food and consumer goods was reduced as items were mass-produced and transportation costs decreased.

Better tools became available for manufacturers and farmers.

The coal, iron, and steel industries boomed to provide fuel and raw materials for machines to work.

The canal system was expanded but then declined.

Urbanisation accelerated as labour became concentrated around factories in towns and cities.

Cheap train travel became a possibility for all.

Demand for skilled labour, especially in textiles, decreased.

Demand for unskilled labour to operate machines and work on the railways increased.

The use of child and women labour increased.

Worker safety declined and was not reversed until the 1830s.

Trade unions were formed to protect workers' rights.

The success of mechanisation led to other countries experiencing their own industrial revolutions.

Coal Mining

Mining of tin and coal has a long history in Britain, but the arrival of the Industrial Revolution saw unprecedented activity underground to find the fuel to feed the steam-powered machines that came to dominate industry and transport. The steam-powered pump was invented to drain mines in 1712. This allowed deeper mining and so greatly increased coal production. The Watt steam engine, patented in 1769, allowed steam power to be harnessed for almost anything, and as the steam engines ran on coal, so the mining industry boomed as mechanisation swept across industries of all kinds. This phenomenon only increased with the spread of the railways from 1825 and the increase in steam-powered ships from the 1840s. Coal gas, meanwhile, was used for lighting homes and streets from 1812, and as a source of heat for private homes and cookers. Coke, that is burnt coal, was used as a fuel in the iron and steel industries, and so the demand for coal kept on growing as the Industrial Revolution rolled on.

There were four principal coal mining areas: South Wales, southern Scotland, Lancashire, and Northumberland. To get the coal to where it was needed, Britain's canal system was significantly expanded as transportation by canal was 50% cheaper than using roads. By 1830, "England and Wales had 3,876 miles in 1760" (Horn, 17). Britain produced annually just 2.5 to 3 million tons of coal in 1700, but by 1900, this figure had rocketed to 224 million tons.

Continue reading...

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

📝 Velour

Ding.

Ding.

Ding.

The notifications on Velour's phone had been non-stop for the past week. Such is what happens every time this season rolls around.

The kitsune troll, on the other hand, was ignoring them for the time being. He didn't need to respond immediately, as all he could say was a generic response that he currently was not taking reservations for ball outfit slots, and that he will announce when commissions are open and how many he will be taking once the theme is revealed. He'd already posted that on all of his social medias, and while normally he would take the time to respond individually, all he could hear was the tiny voice of his moirail in the back of his head going 'Who cares? Their fault for not reading! Ignore those idiots!'

And, for once, he agreed. He guesses this is just what it means to practice self-care?

Speaking of self-care, that was something he was currently indulging in - If one could call practicing magic a form of self-care. He certainly does, when he's found inspiration to try out new illusions.

Velour's new spell had received praise from everyone he had showed it to so far. Which was only Hazard and Jamie, but still! They loved the floating word illusions! And he thought it was fun too, but... How could he make it better?

Or - what might be equally as fun, - how can he turn it into a prank to impress his mentor?

Kizuna was a lot more difficult to please, especially when it came to minor illusions like the sparkles that Velour enjoyed creating so much, and easily saw through his more complex attempts. It seemed like the more difficult the illusion was to create, the more likely the other kitsune noticed the smaller things that he had overlooked: The texture of an apple disguised as an orange being incorrect, the light hitting a projection of a spooky ghost incorrectly, and Velour's general inability to create illusions with weight and sound.

But, while planning out his design for a poncho he was making for Hazard, Velour had gotten an idea. What if he was able to combine his textiles knowledge with his illusions as a base, just like how he can use ink and paper to write wards? Now that has to impress his mentor, surely!

The cuspblood was sitting at the desk in his sewing room, carefully hand-embroidering a small strip of black fabric with bronze thread. It appeared to be an ordinary bundle of thread upon first glance, but he had asked Jikiro to enchant it for him so that he would be able to channel his own magic through it, similar to the ink pen Jamie had made him. It was only a hunch, and he wasn't sure how well it would work, but it was worth a shot.

If it didn't work, at least Kizuna would have a pretty scrunchie with an interesting pattern on it, he guesses?

Once the elastic is fed through and the loop is sewn up, it might be difficult to tell that the embroidered design is a repeating pattern of the kanji for talk: 話. Or, at least, a very close approximation to the kanji, it was rather difficult to get the strokes correct at both a small scale and using thread.

Not that the symbol mattered, as the entire time he had been sewing the scrunchie together, he was pouring his magic into the threads, weaving the spell into the fibres. He wanted the spell to last as long as possible, even if the scrunchie got no mileage out of it outside of the initial prank.

He stifled a yawn as he fed the elastic into the fabric tube, then used his sewing machine to finish the final steps. He'll definitely need a nap after this, but for now...

"There, done!" Velour exclaimed to himself, looking proudly at his latest creation. "Now, let's try it out!"

He stood up, and made his way over to the full-length mirror so he could witness his own magic in action. As he walked, he took the scrunchie and tied his hair back with it to the best of his ability. In hindsight, maybe a scrunchie wasn't the best idea since Kizuna's hair is about the same length as his own, but he has seen people wear them as bracelets as a fashion statement before. Maybe he can present it to his mentor and say it's that instead?

Anyway, staring at his reflection while feeling glad he cannot see the sad attempt at a ponytail from this angle, Velour took in a deep breath.

"Ah, maybe I should have prepared a proper speech to test, or somethi- Oh!"

As the cuspblood spoke, letters began to pop up and float around him, forming every word that left his mouth. There was a slight delay between what was said and what he could see, but otherwise the spell functioned exactly how he wanted it to.

"Oh! Yes! It's working! It's- Ah, it's taking a while for the words to fade away, maybe I used too much magic after all."

The reflection in the mirror would have shown Velour's embarrassed expression, had it not been for the fact that there was now words floating all around his head and blocking his vision. He waved them away, using another spell to force the illusion to dissipate.

There's definitely a lot more work that'll need to be done with the enchanted thread once he makes a start on making the ponchos for himself and Hazard, but for Kizuna? This prank is annoying enough to be perfect.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pattern

Warbled glass having decided to let light through but declining to say much else,

hard-hearted like argyle's squabbles with plaid designed to distract from the disdain for a homogenous plain unadorned and infinite like the factory never gets to the last of the roll, the engine just keeps going and out comes more of the same,

and we find any pattern we can to distract from that,

we patter like the hearts of the workers who won't last but for a while make the textiles go, the exile of knowing the need of cloth and all the things contributing to it and to every other need, how the machines need feeding and we have sympathy, and how ashamed that makes us,

how plentiful the secondary reasons could be and we won't see even one.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The main event, the wool market, starts in the gymnasium of the Floccesy school, spilling out into the halls and even behind the building. Vendors from all over have come to sell their textile wares or handicraft goods. There is a constant flow of people coming in, with patrons stopping to shop or watch craftsmen work at their booths.

Gymnasium Vendors:

The main area for textile vendors. They have sections roped off for various displays to educate potential customers about the processes involved with their wares.

Fleece Dyer: They have set up a stand with their dye pots to show the process. While the rovings used in the display are not for sale, they have a rainbow of pre-dyed rovings to purchase.

Plush vendor: A vendor who has crocheted a whole pokedex has them on display in national dex order and quite a few shiny variants.

Fluff Station: Various tables of freshly cleaned fluff from Pokemon. The fluff rolls are arranged by the typings of Pokemon it came from. Staff are at each table to explain how the fluff is gathered and what are various uses for it.

Spinning: The station with the most action. The worker is using a machine to spin fluff into yarn. Their daughter is using yarn to make kumihimo braids when she is not manning the cash register. The braids she does finish are being sold as “friendship bracelets”. If people ask, the girl can show them how to make twist braids for quick custom bracelets.

Hallway Vendors:

These vendors have various handicraft goods. As the halls are more cramped than the gymnasium, the vendors have smaller stands and are not able to make custom goods on the spot. Some are willing to make custom orders that would be mailed.

Painter: A local artist has set up their table of paintings and advertisements for their studio. Browsing their works, you see that they have been all over Unova, getting paintings of the Relic Castle, the Pokemon League, and Skyarrow Bridge. They have framed paintings, full size prints, and miniature canvases on sale.

Stained Glass: A glass artisan has various sun catchers of various designs hanging on the wall. They have a form for making custom pieces, with price ranges for various sizes and complexities.

Pokeball Painter: A custom Pokeball painter. There are balls for sale with designs according to types, some painted to look like Pokemon, and others are painted to mimic other pokeballs. There are a couple that look like the masterball. Despite the lack of space, the artist has their station set up to paint simple designs on Pokeballs on the spot.

Custom jewelry: Different racks of jewelry section off the space this seller occupies, all crowded with different charms, pendants, and earrings. The majority of the charms that make the jewelry have Unovan sports team logos or semi-precious stones. The children’s racks have plastic cartoon characters on them.

Face painter: The most popular booth for kids! Two painters are set up with their kits and a book of designs to pick from. Many kids are just hopping up onto the provided stools and asking for something without looking.

Outside:

The area in the back is noisy, with a roped off path that leads the crowd around a petting zoo.

Duck Slide: recently hatched duckletts are hopping down a slide! They waddle back up on ramps on both sides of the slide. There’s a quaxly mixed in with them for some reason.

Skiddo feeding station: For a small fee, visitors can buy a handful of feed for skiddo. The grass types are raised by local children to be shown in the summer fairs later.

Wooloo pen: A pen of freshly shaved wooloo. These Pokemon will headbutt the fencing to try to get pets from visitors.

Yamper run: Yampers are chasing a Boltund who is teaching them how to herd. The smaller yampers will run to the fencing to beg for treats or pets.

Buneary Den: Several buneary are let out to hop around freely. A farmhand is nearby to help show off the tricks the buneary learned! They even have treats for people to feed the pokemon.

Wool Market Starters here!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unsold clothing may no longer be destroyed in Europe

More than 100,000 tons of discarded clothing ends up in a desert in Chile

Europe is putting a stop to the throw-away culture through a ban on destruction[1] and a digital product passport with information about shelf life and repairability. No more mass destruction of clothing and other unsold merchandise.[2]

Every second in Europe, a full garbage truck of clothing is burned or dumped[3]. And every year, an estimated 11 to 32 million unsold and returned garments are destroyed. Europe has been wanting to reduce this gigantic waste for some time. The European Member States and the European Parliament reached an agreement to this end on Monday evening 4-12: Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation[4]. The aim of the 'eco design law' is to make many products more repairable, reusable and recyclable. A product passport and a ban on destruction of unused goods are the key measures.

1. What is a digital product passport?

Consumers are already somewhat familiar with this: the energy label on refrigerators and washing machines gives an indication of their sustainability. That label (or product passport) has had an enormous impact on making those appliances more energy efficient.

The European Parliament and the EU member states now have an agreement to roll out the digital passport more widely and to deepen its content. First of all, almost all products on the European market will have to have such a passport: from car tires and steel to washing tablets and cosmetics to clothing or smartphones. The only exceptions are food, medicine, cars and weapon systems, for which there are separate regulations.

In addition to any energy consumption, the passport also contains information about the origin, composition, repair and disassembly options of the product. This should also make it easier to repair and recycle them. “People can know at a glance which product is the most durable or easiest to repair,” said MEP Sara Matthieu (Green), who was rapporteur in the negotiations.

2. What does the ban on destruction mean?

Initially, the ban applies to textiles. Globally, 92 million tons of textile waste are produced annually. A large portion of these are returned or unsold goods. In two years' time, they may no longer be destroyed, but must be reused or recycled. This ban will eventually be extended to electronics and electrical appliances. Massive quantities of these are also destroyed every year, especially cheaper items that are not sold or have been returned to the manufacturer.

The new rule goes hand in hand with stricter requirements for composition, repairability and disassembly of goods. The details will be worked out product by product by the European administration, but some guiding principles are a ban on adhesives, the absence of toxic substances, the obligation to have spare parts available and, above all, to offer them at an affordable price. The passport should eventually lead to a 'repair score', comparable to the energy label.

Matthieu (Green) expects a huge impact on the consumer market. 'Instead of offering disposable products for mass consumption, companies will offer many more services through robust devices. So to speak, you will no longer buy a washing machine, but an number of wash cycles.'

3. How comprehensive are the measures?

That depends on the control. The product passport is also an important instrument for this. Europe is counting on the famous 'Brussels effect': foreign producers will have to adapt their products if they want to maintain access to the gigantic European consumer market. Although the European consumer organisation BEUC[5] warns against loopholes. The organisation mainly sees a risk that international online platforms such as Amazon or Alibaba will circumvent the new law.

4. Is this agreement now final?

It has already rounded the most important cape. The agreement was finalised in the so-called trialogue negotiations between the European Parliament, the European Council and the Commission. Now it must be approved by Parliament and the Member States, but that counts as a formality.

Source

Lieven Sioen, Onverkochte kledij mag niet meer vernietigd worden in Europa, in: De Standaard, 6-12-2023, https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20231205_96579697#:~:text=In%20eerste%20instantie%20is%20het,ze%20hergebruikt%20of%20gerecycleerd%20worden.

[1] Deal on new EU rules to make sustainable products the norm; https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20231204IPR15634/deal-on-new-eu-rules-to-make-sustainable-products-the-norm

[2] Read also: https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/722179599996534784/towards-a-circular-and-more-sustainable-fashion?source=share

[3] Read also: https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/723895455727157248/new-report-clothes-are-mercilessly-downcycled-or?source=share & https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/720260226679488512/hms-answer-about-the-dumped-clothes-article?source=share

[4] The proposal for a new Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), published on 30 March 2022, is the cornerstone of the Commission’s approach to more environmentally sustainable and circular products. The proposal builds on the existing Ecodesign Directive, which currently only covers energy-related products. https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/sustainable-products/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en

[5] The European Consumer Organisation (BEUC, from the French name Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs, "European Bureau of Consumers' Unions") is an umbrella consumers' group, founded in 1962. Based in Brussels, Belgium, it brings together 45 European consumer organisations from 32 countries (EU, EEA and applicant countries). BEUC represents its members and defends the interests of consumers in the decision process of the Institutions of the European Union, acting as the "consumer voice in Europe". BEUC does not deal with consumers’ complaints as it is the role of its national member organisations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The baby made a faint grunting noise before it did something unspeakable down the front of Sugafana’s shirt. Sugafana barely flinched. “I’ll be fine; I’ve done it before! Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to clean up and get this baby something to wear.”

When Sugafana’s street was flooded by human rebels trying to short out the circuits of headphone guards, she didn’t take much. Just the essentials: a blanket, her water refillable condensation bottle, and her mother’s box of wedding jewelry. She also took her roommate.

“Afternoon, Nani,” Sugafana greeted her grandmother as she pushed aside the curtains that gave their small cave a tiny bit of privacy. Home was two rolled-up sleep mats on the floor with bedding, a box filled with clothing, and a small hissing and spitting machine standing in the corner. Natural grooves and holds in the lava stone walls had been used to display jars filled with buttons and thread. An embroidered tapestry depicting a little girl holding a cat hung from the ceiling.

“You’re back early,” Nani remarked, barely looking up from a dress shirt she was busy repairing.

“Yes, I found something expensive on the field,” Sugafana admitted, and Nani looked up, her hand still instinctively stitching away at the shirt's tear. Looking at Nani was like looking into her future. They both had the same round faces, amber eyes, and warm beige skin. Nani’s eggplant purple hair, however, had long ago turned ashy white with faint streaks of black. Her suspicious eyes were now surrounded by thick lines.

“You found a baby,” Nani said flatly, as Sugafana gently placed the baby in the center of the sleep mat.

“I found a maternity droid and sold it to Bappa; the baby was locked inside,” Sugafana replied as she shed her filthy shirt, switching it for a plain black blouse.

“We can’t keep a baby! I barely have time to keep up with all the clothes people drop off, and you’re out working twelve hours a day,” Nani grumbled. Many of the refugees in the camp had spent decades using A.I. appliances to clean and repair their outfits. Most of them found washing their socks baffling and panicked at the thought of torn trousers. Thankfully, before the war, Nani had worked as a historical preservationist at the Museum of Ancient Textiles.

“I never said I was keeping her, Nani! I’m taking her into the city to find her family,” replied as she grabbed an old scarf, wrapping it around the baby's bottom like a makeshift nappy.

“The city,” Nani said flatly, “It’s not like this camp has genetic testing pods lying around,” Sugafana pointed out. “We avoid the city for a reason!” Nani said, tapping her legs.

Nani’s legs hadn’t worked right since she caught Martian Polio as a child. The machines insisted that those who couldn’t run to generate power had to be “recycled.”

“I’ll be fine, Nani! I go to the city's teleportation pod every week for ice deliveries,” Sugafana said firmly, and Nani sniffed, glancing down at the baby.

“Odd little thing, isn’t she? Her hair is green! You don’t see that much around here,” Nani remarked.

“No, you don’t,” Sugafana admitted. Almost everyone she knew had hair that was either black or in various shades of deep purple. Green hair belonged to tourists from the outer planets. The baby's skin, however, was darker than hers, and she stirred slightly, her eyes opening a crack, revealing black eyes.

“She’ll need feeding,” grunted Nani, turning to the spitting machine in the corner. The Creatrix was an essential household item that could be found in almost any home. Using electrified sand from the moon of Titan and computer codes, it had the ability to generate almost any inorganic material. Sugafana’s Creatrix was a small portable camping one that her grandfather took on hiking trips. It couldn’t create clothing and only had fifty recorded codes, but it had its uses.

“I’m sure the machine still has the baby formula codes in it; we used to make bottles for your sister when she was tiny,” Nani remarked, and Sugafana pursed her lips together.

“Then that means those codes are at least twenty years old,” Sugafana pointed out, refusing to think about her sister.

“Codes are codes! You’ll need four bottles for a trip into the city and back, and an ever-cleaning nappy! Not a filthy scarf,” Nani said, scooping four cups of glittering black sand out of a flour bag.

“You need that sand for your pain tea, Nani!” Sugafana protested, and Nani waved her away with annoyance before punching in several numbers.

“I can handle leg twitches! You won’t be able to handle a screaming, filthy newborn,” Nani said firmly.

“Fine! But as soon as I get back, we are packing to head to Harris Park, and you will need to drink four cups of tea for that journey,” Sugafana said as Nani handed her an ever-cleaning diaper. Sugafana still remembered dressing her baby sister in one when she was ten years old. The diapers were supposed to clean a soiled baby automatically forever, but they tended to break down after a few weeks.