#Urban Policy

Text

This quote comes from Dan Immergluck's great book "Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First-Century Atlanta." Recommended reading.

Atlanta saw a 28% increase in its tech talent pool from 2013-18. During that boom, we missed a huge opportunity for equitable outcomes.

Instead of transforming that economic growth into critical public services such as subsidies for housing for lower-income Atlanta, the inflow of higher-wage workers just ended up driving local rents higher, hurting low-income folks the most.

I'm glad to see the city make good efforts toward affordable housing in recent years. We're moving in the right direction.

But going forward, we need to think of growth and investment as a tool for truly equitable outcomes, with measurable success. We're not at that point yet.

City leaders are constantly getting an earful of demands from the local elite about remaining "business friendly" and not disturbing the status quo of investment returns for powerful interests. They need to hear from the rest of us.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eating houses in Singapore | Our public living room

One of the most beautiful traits of the coffee houses (or eating houses) in Singapore is that anyone come in and feel at ease over a hot meal or drink.

There is no gender divide: women are just as welcome as men. There is little class consciousness: in fact, strangers across social strata often share a table (my photoessays here and here expose the diversity of people donning suits to slippers).…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

LARGEST-EVER EVICTION IN L.A. (SINCE CHAVEZ RAVINE)

Mike Bonin of What’s Next, Los Angeles joins us to talk about the impending eviction of at least 500 renters at the Barrington Plaza in West Los Angeles this September. We also discuss the expiration of affordable housing at the Hillside Villa in Chinatown and its implications for L.A.’s affordable housing supply overall, and how the city attorney’s office can do more to defend L.A.’s renters…

View On WordPress

#barrington plaza#ellis act#evictions#homelessness#la city hall#Los Angeles#los cuentos#podcast#renters#urban policy

0 notes

Link

Public transit systems face daunting challenges across the U.S., from pandemic ridership losses to traffic congestion, fare evasion and pressure to keep rides affordable. In some cities, including Boston, Kansas City and Washington, many elected officials and advocates see fare-free public transit as the solution.

Federal COVID-19 relief funds, which have subsidized transit operations across the nation at an unprecedented level since 2020, offered a natural experiment in free-fare transit. Advocates applauded these changes and are now pushing to make fare-free bus lines permanent.

But although these experiments aided low-income families and modestly boosted ridership, they also created new political and economic challenges for beleaguered transit agencies. With ridership still dramatically below pre-pandemic levels and temporary federal support expiring, transportation agencies face an economic and managerial “doom spiral.”

Free public transit that doesn’t bankrupt agencies would require a revolution in transit funding. In most regions, U.S. voters – 85% of whom commute by automobile – have resisted deep subsidies and expect fare collection to cover a portion of operating budgets. Studies also show that transit riders are likely to prefer better, low-cost service to free rides on the substandard options that exist in much of the U.S.

Why isn’t transit free?

As I recount in my new book, “The Great American Transit Disaster,” mass transit in the U.S. was an unsubsidized, privately operated service for decades prior to the 1960s and 1970s. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, prosperous city dwellers used public transit to escape from overcrowded urban neighborhoods to more spacious “streetcar suburbs.” Commuting symbolized success for families with the income to pay the daily fare.

These systems were self-financing: Transit company investors made their money in suburban real estate when rail lines opened up. They charged low fares to entice riders looking to buy land and homes. The most famous example was the Pacific Electric “red car” transit system in Los Angeles that Henry Huntingdon built to transform his vast landholdings into profitable subdivisions.

However, once streetcar suburbs were built out, these companies had no further incentive to provide excellent transit. Unhappy voters felt suckered into crummy commutes. In response, city officials retaliated against the powerful transit interests by taxing them heavily and charging them for street repairs.

Meanwhile, the introduction of mass-produced personal cars created new competition for public transit. As autos gained popularity in the 1920s and 1930s, frustrated commuters swapped out riding for driving, and private transit companies like Pacific Electric began failing.

Grudging public takeovers

In most cities, politicians refused to prop up the often-hated private transit companies that now were begging for tax concessions, fare increases or public buyouts. In 1959, for instance, politicians still forced Baltimore’s fading private transit company, the BTC, to divert US$2.6 million in revenues annually to taxes. The companies retaliated by slashing maintenance, routes and service.

Local and state governments finally stepped in to save the ruins of the hardest-strapped companies in the 1960s and 1970s. Public buyouts took place only after decades of devastating losses, including most streetcar networks, in cities such as Baltimore (1970), Atlanta (1971) and Houston (1974).

These poorly subsidized public systems continued to lose riders. Transit’s share of daily commuters fell from 8.5% in 1970 to 4.9% in 2018. And while low-income people disproportionately ride transit, a 2008 study showed that roughly 80% of the working poor commuted by vehicle instead, despite the high cost of car ownership.

There were exceptions. Notably, San Francisco and Boston began subsidizing transit in 1904 and 1918, respectively, by sharing tax revenues with newly created public operators. Even in the face of significant ridership losses from 1945 to 1970, these cities’ transit systems kept fares low, maintained legacy rail and bus lines and modestly renovated their systems.

Converging pressures

Today, public transit is under enormous pressure nationwide. Inflation and driver shortages are driving up operating costs. Managers are spending more money on public safety in response to rising transit crime rates and unhoused people using buses and trains for shelter.

Many systems are also contending with decrepit infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives U.S. public transit systems a grade of D-minus and estimates their national backlog of unmet capital needs at $176 billion. Deferred repairs and upgrades reduce service quality, leading to events like a 30-day emergency shutdown of an entire subway line in Boston in 2022.

Despite flashing warning signs, political support for public transit remains weak, especially among conservatives. So it’s not clear that relying on government to make up for free fares is sustainable or a priority.

For example, in Washington, conflict is brewing within the city government over how to fund a free bus initiative. Kansas City, the largest U.S. system to adopt fare-free transit, faces a new challenge: finding funding to expand its small network, which just 3% of its residents use.

A better model

Other cities are using more targeted strategies to make public transit accessible to everyone. For example, “Fair fare” programs in San Francisco, New York and Boston offer discounts based on income, while still collecting full fares from those who can afford to pay. Income-based discounts like these reduce the political liability of giving free rides to everyone, including affluent transit users.

Some providers have initiated or are considering fare integration policies. In this approach, transfers between different types of transit and systems are free; riders pay one time. For example, in Chicago, rapid transit or bus riders can transfer at no charge to a suburban bus to finish their trips, and vice versa.

Fare integration is less costly than fare-free systems, and lower-income riders stand to benefit. Enabling riders to pay for all types of trips with a single smart card further streamlines their journeys.

As ridership grows under Fair Fares and fare integration, I expect that additional revenue will help build better service, attracting more riders. Increasing ridership while supporting agency budgets will help make the political case for deeper public investments in service and equipment. A virtuous circle could develop.

History shows what works best to rebuild public transit networks, and free transit isn’t high on the list. Cities like Boston, San Francisco and New York have more transit because voters and politicians have supplemented fare collection with a combination of property taxes, bridge tolls, sales taxes and more. Taking fares out of the formula spreads the red ink even faster.

0 notes

Text

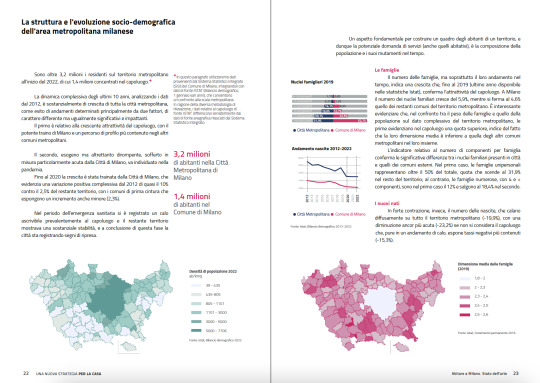

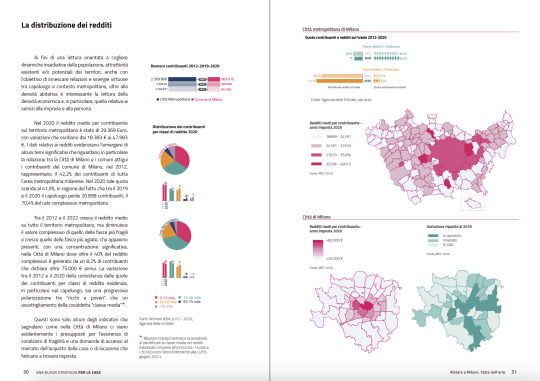

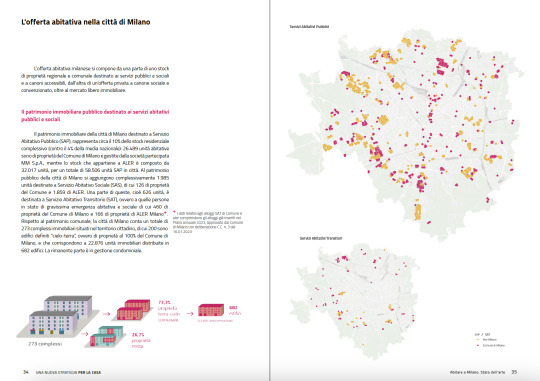

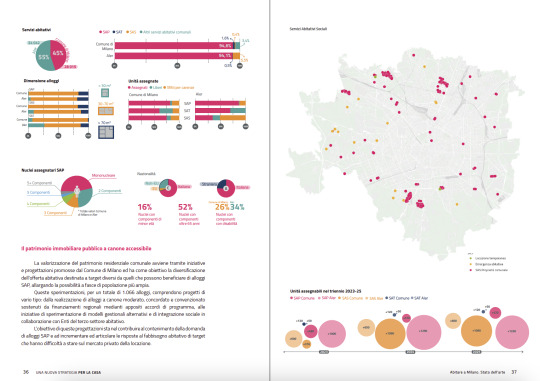

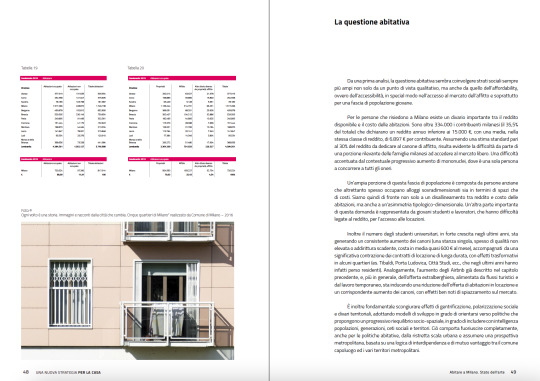

La strategia abitativa di Milano in un documento

Ho affiancato in questi intensi mesi di lavoro l'Assessorato Casa del Comune di Milano nello sviluppo e stesura del documento di visione strategica "Una nuova strategia per la casa" che l'Assessore Pierfrancesco Maran ha presentato alla città in occasione del Forum dell'Abitare, dal 20 al 22 marzo 2023, per discuterne i contenuti e aprire a contributi, come punto di partenza di un processo di riflessione comune.

La Nuova strategia per la Casa è online e accessibile qui:

https://www.forumabitaremilano.it/nuova-strategia-per-la-casa

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Normalize updating laws and regulations that are no longer fit for purpose.

Normalize working with powerful enemies to find a solution where everybody wins.

Normalize mutual compromise.

Normalize collaboration over opposition.

Normalize civil discourse on divisive issues.

Normalize good faith and the principle of charity.

Normalize discussion of specific social, political, and economic issues.

Normalize advocacy for specific and implementable policy reforms to to tackle said issues.

Normalize imperfect solutions.

Normalize civic engagement.

Normalize public sector action.

Normalize incremental success.

Normalize improving society instead of destroying and rebuilding it from the ground up.

NORMALIZE PROGRESS!!!

#solarpunk#hopepunk#politics#political discourse#public policy#civic engagement#civic duty#georgism#transit#urban planning#accessibility#disability justice#disabled#healthy politics#policymakers#social justice#societal improvement#retain hope#societal progress#climate change#climate action#advocacy#trains#political activist#political action#activism#hanlon's razor#good regulations work#good faith arguments#good faith

227 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re zoning regulation reform: could you go into detail as what that would look like in terms of wiping the slate clean. I feel like it would be better to go the houston route and just be zoning free

You do not want to go the Houston route.

youtube

Houston may claim to be "zoning-free" - and to be fair, it doesn't have some of the more common regulations on land use, or density, or height restrictions (more on this in a minute) - but the reality is far more complicated and the status quo is not one that's friendly to the interests of working-class and poor residents, or to the possibility of sustainable urbanism.

The answer to NIMBYism isn't to abolish all regulations and let the free market rip, it's to surgically target zoning, planning, and litigation that is used against affordable housing, public/social housing, mass transit, clean energy, and walkable neighborhoods, and to replace it with new forms of regulation that encourage these forms of development.

So let's take take these categories in order.

Zoning

As I tell my Urban Studies students, zoning is both one of the most subtle and yet comprehensive ways in which the state shapes the urban environment - but historically it has been used almost exclusively in the interests of racism and classism. Reforming zoning requires going over the code with a fine-toothed comb to single out all the many ways in which zoning is used to make affordable housing impossible:

The most important one to tackle first is density zoning and building heights limitations. The former directly limits how many buildings you can have per unit of land (usually per acre), while the latter limits how big the buildings can be (expressed either as the number of stories or the number of feet, or as both). Closely associated with these zoning regulations are minimum lot size regulations (which regulate how much land each individual parcel of real estate has to cover, and thus how many how many housing units can be built in a given area), and lot coverage, setbacks, and minimum yard requirements (which limit how much square footage of a lot can be built on, and what kinds of structures you can build).

the other big one is use zoning. To begin with, we need to phase out "single use" zoning that designates certain areas as exclusively residential or commercial or industrial (a major factor that drives car-centric development, makes walkable neighborhoods impossible, and discourages the "insula" style apartment building that has been the core of urbanism since Ancient Rome) in favor of "mixed use" zoning that allows for neighborhoods that combine residential and commercial uses. Equally importantly, we need to eliminate single-family zoning and adopt zoning rules that allow for a mix of different kinds of housing (ADUs, duplexes and triplexes, rowhouses/terraced houses, apartment buildings).

finally, the most insidious zoning requirements are seemingly incidental regulations. For example, mandatory parking minimums not only prioitize car-dependent versus transit-oriented development but also eat up huge amounts of space per lot. The most nakedly classist is "unrelated persons" zoning, which is used to prevent poorer people from subdividing houses into apartments, which zaps young people who are looking to be roommates and older people looking to finance their retirements by running boarding houses or taking in lodgers, as well as landlords looking to convert houses from owner-occupied to rental properties.

So I would argue that the goal of reform should be not to eliminate zoning, but rather to establish model zoning codes that have been stripped of the historical legacies of racism and classism.

Planning

Similar to how zoning shouldn't be abolished but reformed, the correct approach to planning isn't to abolish planning departments wholesale, but to streamline the planning process - because the problem is that right now the planning process is too slow, which raises the costs of all kinds of development (we're focusing on housing right now, but the same holds true for clean energy projects), and it allows NIMBY groups to abuse the public hearings and environmental review process to block projects that are good for the environment and working-class and poor people but bad for affluent homeowners.

As those Ezra Klein interviews indicate, this is beginning to change due to a combination of reforms at both the state and federal level to speed up the CEQA and EPA environmental review process in a number of ways. For example, one change that's being made is to require planning agencies and environmental agencies to report on the environmental impact of not doing a project as well, to shift the discussion away from petty complaints about noise and traffic and "neighborhood character" (i.e, coded racism and classism) and towards real discussions of social and environmental justice.

At the same time, more is needed - especially to reform the public hearing process. While originally intended by Jane Jacobs and other activists in the 1970s as a democratic reform that would give local communities a voice in the planning process, "participatory planning" has become a way for special interests to exercise an unaccountable veto power over development. Because younger, poorer and more working class, and communities of color often don't have time to attend public hearing sessions during the workday, these meetings become dominated by older, whiter, and richer residents who claim to speak for the whole of the community.

Moreover, because community boards are appointed rather than elected and public hearings operate on a first-come-first-serve basis, an unrepresentative minority can create a false impression of community opposition by "stacking the mike" and dialing up their level of militancy and aggression in the face of elected officials and civil servants who want to avoid controversy. (It's a classic case of diffuse versus concentrated interests, something that I spend a lot of classroom time making sure that my students learn.)

Again, the point shouldn't be to eliminate public hearings and other forms of participatory planning, but to reform them so that they're more representative (shifting public hearings to weekends and allowing people to comment via Zoom and other online forums, conducting surveys of community opinion, using a progressive stack and requiring equal time between pro and anti speakers, etc.) and to streamline the review process for model projects in categories like affordable housing, clean energy, mass transit, etc.

Litigation

Alongside the main planning process, there is also a need to reform the litigation process around development. In addition to traditional tort lawsuits from property owners claiming damage to their property from development, a lot of planning and environemntal legislation allows for private groups to sue over a host of issues - whether the agency followed the correct procedures, whether it took into account concerns about this impact or that impact, and so forth.

As we saw with the case of Berkeley NIMBYs who used CEQA to block student housing projects over environmental impacts around "noise," this process can be used to either block projects outright, or even if the NIMBYs eventually lose in court, to draw out the process until projects fall apart due to lack of funding or the proponents simply lose their patience and give up.

This is why we're starting to see significant reforms to both state and federal legislation to streamline the litigation process. The categorical exemptions from review that I discussed above also have implications for litigation - you can't sue over reviews that didn't happen - but there are also efforts to speed up the litigation process through reducing what counts as "administrative record" or by putting a nine-month cap on court proceedings.

Again, this is an area where you have to be very surgical in your changes. Especially when the politics of the issue divide environmental groups and create odd coalitions between labor, business, climate change activists, and anti-regulation conservatives, you have to be careful that the changes you are making benefit affordable housing, clean energy, mass transit and the like, not oil pipelines and suburban sprawl.

#public policy#housing#zoning#policy history#urban planning#public housing#social housing#yimbys#yimbyism#affordable housing#urban studies#urbanism#houston#nimbyism#nimbys#environment#climate change#clean energy

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

writing a research paper and I cannot find sources for a fact that I KNOW is true. so dude just trust me

#the problem with finding a citation for really basic facts in your field#is that they’re too obvious to dwell on in research papers so people don’t bring them up#PLEASE just give me a good short historical overview of the automobile as an urban policy object post WWII PWEASE

228 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Specifically they demolished black neighborhoods, car infrastructure is inherently racist. From here.

#fuck cars#urban planning#public transit#public transportation#orange pilled#not just bikes#walkable cities#racist policies

552 notes

·

View notes

Text

not to sound like a 13 year old but i've got particular beef with the idea of the districts of panem lining up with the geography of north america like i Get it i've seen the maps i understand the intent of the author and how it makes sense culturally but deep down inside it just feels wrong to me and i can't do it.

it's like u say "nuclear war wiped out most of the planet" and that's supposed to make me accept that the extraordinarily strong culture of american statehood just collapsed into 12 regional districts like that?? fine i guess if we account for a long long gap of time between nuclear war and the original inception of panem. maybe.

but also. the way it's described clearly implies each district is able to gather its entire population in one square on one day for reaping day and honestly strongly implies that each district + the capitol are comprised of only one urban center (of varying sizes) each implying that the area of these districts Has to be so much fucking smaller than it appears on any of the maps that float around. where is all the empty space. the north american landscape is Huge even with the amount of coastline taken away due to oceans rising and that space is like. a huge huge factor in living here. there is not that sense of geographic scale and empty spaces between districts except like. the forests outside of 12 (speaking of like. katniss is able to walk the entire fence by herself in less than a day to check for weak points. these districts are small. even if 12 is smaller than say 11. that's ridiculously tiny all of these districts have to be small and definitely not entire regions of the continental united states)

also many many other ppl have made this point lmao but. the foreign policy of panem is not mentioned except for those vague notions of a nuclear war in the distant past and it is just. stretching imagination beyond belief to imagine that if panem truly is north america president snow literally is only concerned with domestic policy even the most isolated authoritarian regimes on earth today still have to deal with foreign policy on some level (and north america is lucky to have near self sufficiency w resources bc oil and such but. we do not have rare earth metals to sustain the technology level of panem. i'd be willing to discuss the hypothetical that panem has zero computers and batteries it's not impossible but.)

all in all it's very clear that culture/resources of 12 is inspired by and modeled on appalachia and that the more extreme repression/resources of 11 are inspired by and modeled on agriculture and racist government styles of the deep south etc etc and that makes sense bc like. suzanne collins is deeply entrenched in american culture and so is the hunger games as a series and she absolutely nails the culture and political connections bc it's an extremely adept commentary on modern american society but. the geography just doesn't make sense and raises too many questions and i wish you all would accept like me that it takes place in a fantasy land of pure allegory

#the handmaid's tale version of america and the uglies version of america i do accept.#bc they both have clear ties to the past Before dystopia got put in place and have govt's concerned w foreign policy!!!#and in the uglies series for example there is a sense of the geographic scale of the north american continent despite the current populatio#being packed into self sufficient urban centers#plus!! other countries!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! they go to japan!#the hunger games

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love citing my sources in politics. "These are unproven policies!" Bitch here are studies from multiple universities, and here are some states and municipalities that have implemented them, and their benefits, in numbers. And these examples are all within the United States because I know the idea of doing something Europe does will give you an aneurysm (even though these polcies also exist in Scandinavia)

#and honestly I do get it at times#I am genuinely fed up with dutch public transport discourse#just becaus it often feels less like a good example and more like shaming places that aren't Amsterdam for not being Amsterdam#plus I prefer Copenhagen#policy#politics#urbanism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

CAN A HOTEL ROOM BE HOME?

A few weeks ago, Ali Rachel Pearl and I went to the grand opening of a new housing project in our neighborhood, the Avenida. Last week, on August 4th, we had a conversation in the recording studio at the Robinson Space where we reflected on this specific housing project. More specifically we discussed what, exactly, constitutes a home or a community when it comes to housing those most in need in…

View On WordPress

#culture#east hollywood#homelesness#Housing#koreatown#L.A. Metro#Los Angeles#los cuentos#new beginnings#podcast#urban policy

0 notes

Text

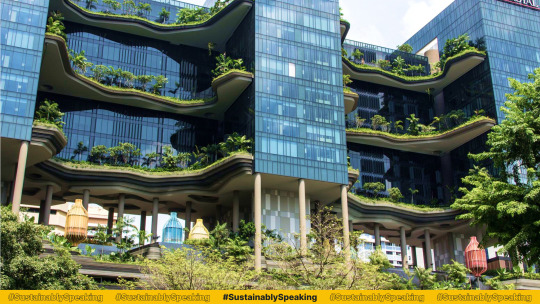

Sustainable Development in Singapore: An Exemplar of Modern Urban Ecology

Strategic Advancement in Green Building: In an ambitious endeavor, Singapore aims for 80% of its buildings to be green-certified by 2030, a significant milestone considering its urban density. Changi Airport, an epitome of this initiative, integrates a myriad of eco-friendly features, including the Rain Vortex, the world's tallest indoor waterfall, enhancing its reputation as the "World's Best Airport" for eight consecutive years.

Solar Energy Initiatives: Singapore's commitment to renewable energy is evident in its solar power achievements. Surpassing 820 megawatt-peak (MWp) in solar capacity at the end of 2022, the nation is on track to reach its 2025 target of 1.5 gigawatt- (GWp).

Enhancements in Public Transportation: Singapore's sustainable transport strategy aims for 75% of peak-hour commutes to be via public transport by 2030. The expansion of the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system and the introduction of eco-friendly buses are pivotal in this endeavor, aiming to reduce reliance on private vehicles and lower carbon emissions.

Promotion of Electric Vehicles (EV): The government's extension of the Electric Vehicle Common Charger Grant until December 2025 underscores its commitment to enhancing EV infrastructure. This initiative, covering up to 50% of the cost of smart chargers, has led to the approval of 267 EV charger applications across 107 condominiums since July 2021.

Vision of a "City in a Garden": Singapore's approach to urban development harmoniously blends with environmental stewardship, as seen in its goal to plant one million trees by 2030. The iconic Gardens by the Bay, with its Supertrees, symbolizes this blend of ecological innovation and urban living, integrating features like solar energy collection and rainwater harvesting.

Singapore's multifaceted approach to sustainability is a testament to its visionary leadership, integrating technology, policy, and community involvement to create a living model of a sustainable urban future.

#sustainability#urban ecology#Singapore#renewableenergy#public transport system#electricvehicles#environmentallyfriendly#green building#ev#urban development#green policy#urban greenery#electric cars

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have got to become insaner about things.

#if I had any time rest assured I would be watching a lot of supernatural just to feel soemthing#or bare minimum making effortposts about urban policy#but I do not <3#personal#it’s so boring to not be insane how are people just rawdogging life without a buffer of derangement syndrome#‘you do have any time you’re on here’ well. I am on here stealthily at work while it’s slow and supernatural episodes are not stealthy

8 notes

·

View notes