#Wilderlands of High Fantasy

Text

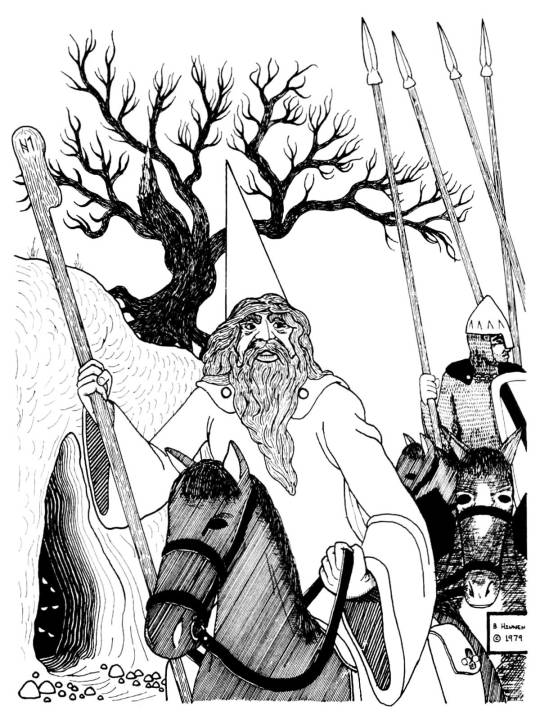

The wizard takes point, ever alert for hidden dungeons and enemies in unexpected places (Bryan Hinnen wrote and illustrated The Mines of Custalcon, Wilderness Book One for the Wilderlands of High Fantasy / City-State D&D campaign, Judges Guild, 1979)

#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#Bryan Hinnen#The Mines of Custalcon#wizard#mage#magic user#Judges Guild#wilderness adventure#Wilderlands of High Fantasy#City State campaign#campaign setting#Anglo Norman#dnd#Dungeons and Dragons

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old school multiracial anarchism

In the mid-eighties, after I graduated from high school, I found myself far from my old HS buddies and no longer had anyone to play AD&D with and I found myself soloing with my own ideas and thoughts.

So, there was this character I picked up from the Judges Guild’s Wilderlands of High Fantasy supplement . . . Azarit the Anarchist. He was one of the NPCs listed for Haghill near to the City State.

I took Azarit and travelled him to a different universe (for some reason), placing him in a randomly generated wilderness. In the center of the wilderness was a settlement at what I named Castle Odo. Azarit, being an anarchist, turned this settlement into an autonomous collective in which good and evil races could co-exist without the feudal system pushing them into conflict with each other. There was more than enough resources for everyone, of course, once you eliminate the nobility and the gentry sucking off the peasant and adventuring classes.

As far as I worked it out at the time, there was a sizeable goblin/orc demographic living with humans with a few elves and dwarves thrown in. There was also a small weretiger demographic. Things like property and marriage were abolished.

It is neither here nor there, but my version of Azarit met his end when attempting to either convert or clear out nearby monsters . . . he was burned alive by dragon fire. Apparently dragons are regressive and reactionary. They just are not going to see themselves as equals to those little bipedal races they see as food.

Thus ended the experiment in anarchistic autonomous collectives in my old school universe. I don’t know what ever happened to Castle Odo, but I assume it became a retreat center in the nineties, was bought out and commercialized in the early 2000s, only to go bankrupt and abandoned by the 2010s.

0 notes

Photo

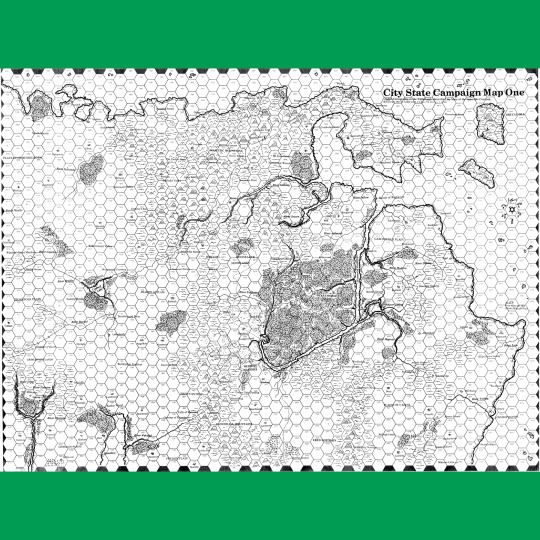

Wilderlands of High Fantasy (1977) is a massive step forward in terms of what we now know as a campaign setting. It lays out regions of the world totaling about the square miles of Cuba, organized in such a way as to be similar to areas surrounding the Mediterranean. It is a massive sandbox largely unrivaled at the time. By way of comparison, the Greyhawk campaign folio was still three years off.

Wilderlands comes with two booklets. We’re still in the period where the school of thought centers on helping facilitate players in the creation of their own world, so there isn’t a ton of concrete information laid out here. Instead, you have nested random tables, lots of them, to use in filling out the landscape yourself. They work the same basic way as the Random Dungeon Generator in the Dungeon Masters Guide (still a year off!), with the designer moving from table to table, filling in details as indicated, until the thing seems finished. Wilderlands provides tables for tons of fine detail.

With the broad strokes of the world laid out, JG was free to fill it in over time from one end while players did the work in their home campaigns from the other end, meeting, eventually, theoretically, in the middle. Judges Guild would do this in two ways: releasing stuff like Modron, where the details are pre-defined (a nice thing about Wilderlands, too, is that it shows you where the City-State, Tegel Manor and Modron are relative to each other). Then there were more products like this, full of modular tools for creating your own stuff. And so it went, for DOZENS of products. Ground breaking stuff!

Like most other Judges Guild products, Wilderlands was in a state of constant revision. This is the first edition, far as I can tell. Later ones add color to the cover. They might have gotten revised and expanded over the years too – most of the other popular products did.

#RPG#TTRPG#Tabletop RPG#Roleplaying Game#D&D#dungeons & dragons#Judges Guild#Wilderlands of High Fantasy

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image ID: The words Sagas of Stawold written in a stylized font, yellow on a background of deep green scale texture. Beneath the text, bright orange flames arise and reach up toward the text. End ID]

Title: Sagas of Stawold

Status: On Hiatus

Genre: High fantasy, D&D-based

POV: Third (whatever specific type I feel like at the time lol)

Setting: Stawold; germanic-esque town on the border between the civilized Hinterlands and the untamed Wilderlands. Part of the Kingdom of Jurmundy which is a part of the much larger Prendacian Empire. Despite the Emperor being the official ruler, the Imperial Church holds the real power.

Themes: magic, adventure, enemies-to-lovers, found family, dragons, deities, fantasy races, extra-planar travel, religious skepticism, mortality/immortality, extremely grey morality

Synopsis, characters, and post links below the cut

Synopsis: Sadie, K'lai'a'la, and Kireen form a fast bond on a quest to retrieve Ser Taerand Calentavar's stolen emerald from the swampy Wraefen. The adventure goes as wrong as you could imagine but once the emerald is retrieved, the story is only just beginning. Through a political coup, orc siege, and church prosecutions, the story climbs to apocalyptic crescendos and continues until Sadie faces the gods themselves. This story unfolds as played out over 3 years of tabletop game and continues until the current day as a messenger RP. My character, Sadie, has grown from an orphan of Stawold to the matriarch of a rebellion and she won't stop until she rises past the bounds of mortality.

Main characters: Since this is based off a D&D campaign, I keep as true to the story as possible. This means that over the years, players or their characters have come and gone. The cast rotates a bit but Sadie and a few non-player characters will stick around consistently. I’ll list current characters here and give them just a few sentences each. I think I’ll make a character post later.

Sadie: She is my beloved character. Halfling bard of lore.

Kireen: Red dragonborn bright-lord (a less religious paladin basically)

K’lai’a’la: Wood-elf ranger

Brimir: Human fighter

Taerand: High-elf quest-giver, member of the Stawold elite

Find links to all posts below, linked in order and grouped by Chapter (chapter titles were created by the DM and given to us before we started that chapter. Each chapter was 5 sessions long)

Writing on the Wall [chapter summary]

[Post 1] [Post 2] [Post 3] [Post 4] [Post 5] [Post 6] [Post 7] [Post 8] [Post 9] [Post 10] [Post 11] [Post 12] [Post 13] [Post 14] [Post 15] [Post 16] [Post 17] [Post 18] [Post 19] [Post 20] [Post 21] [Post 22] [Post 23] [Post 24] [Post 25] [Post 26] [Post 27] [Post 28] [Post 29]

To Kill a Manticore

[Post 30] [Post 31] [Post 32] [Post 33] [Post 34]

Taglist: (adds/removes always open!) @betwixtofficial @taerandcalentavar @talesfromaurea @faelanvance @definitelyquestionit @drippingmoon @dontcrywrite @a-wild-bloog

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kindly forgive a random burst of ego, but I’m reading back through Northern Babylon, a dieselpunk LotR AU I wrote back in 2015, and … okay. I think I did pretty good on the worldbuilding? I mean, looking at it with D&D on the brain for the past year or so, I feel like the city of New Rhovanion would make a pretty good Eberron-ish campaign setting.

A Metropolis-esque dieselpunk fantasy city, built by a semi-forced alliance of elves, men and dwarves driven from their previous homes (Moria, Mirkwood) by the encroaching Southern Powers, some of them very dark (Dol Guldur).

A city of vertical layers, the vast stone-and-ironworks of the dwarves at the base, carved into the stone of the mountain the city rings, the vast transplanted forestscape of the elves at the top, a towerscape of gardens and glasshouses and aqueduct gondolas, and then the homes and markets of men in the lakeside district and the middle heights of the towers.

A city torn apart in recent memory both by the occupation by a dragon in elven disguise which temporarily drove out the dwarven and human inhabitants, and resulted in significant structural and racial damage during the insurrection that followed, and then later the results of a vast continental war that, while it didn’t do too much direct damage to the city besides airstrikes on the elven towers, still left a lot of scars.

A city struggling to rebuild itself, both in terms of buildings and relationships, in the new and sudden peace, where almost all the old enemies have been defeated, and it’s time for old grudges to possibly be laid aside and new cooperation build once again. Possibly.

Like, this bit:

The city had been spared most of the ravages of the war in the south. They'd held off Mordor's advance south of the Running, managing to avoid military occupation, though the Lake District, the still-extant swathes of Mirkwood Forest, and the surface towers of the city itself had taken some damage. The first two had been the cost of stopping the Easterling ground advance, something Gimli knew had a much higher cost in lives, dwarven, elven and human alike, than it had in infrastructure. The latter had been the result of Nazgul airstrikes relatively early in the war, before the Thornhoth Eagles had driven them back south and the land war in Gondor had taken up too much of the Witch-King's attention to bother with anything north of Dol Guldur.

The strikes hadn't done too much serious damage. Not to the structures themselves, at least. New Rhovanion's towers had held strong against dragonfire bombs less than a generation ago, things that could melt rock and steel and concrete as easily as flesh. They'd withstood the explosive anarchy of Smaug's terrorist campaign, when over half the city's dwarven and human populations had been forcibly expelled, and urban fighting in the undercity had killed hundreds more. Nazgul overflights, for all their potency as a terror weapon, just didn't have the same kind of destructive power.

They'd taken chunks out of the city-top forestscape, though. Now that he had the eye for it, Gimli could see the places where it was still under repair. Several of the vast tiered balconies and the street-spanning aqueducts had given way altogether, even now still in the process of being rebuilt, and there were a thousand strange shards of sunlight to be seen as the great glasshouses and refracting mirrors were moved and repaired across the upper city. Worse than that, though, at least for those to whom mattered, were the vast barren stretches where the forests and gardens themselves had been burned away, leaving only cold concrete, melted steel and blacked earth behind them. The great hanging gardens of New Rhovanion, the city-top cathedral of light, had apparently taken the brunt of the city's physical blows this time.

It was strange for Gimli to find himself noticing that, to find himself understanding the pain of it. Dwarves in New Rhovanion didn't spend a lot of time looking upwards, after all. They had their own section of the city to be thinking about, the vast underground mines and thoroughfares, the lower reaches of the towers and the surface streetscapes where the city monorails and the vast ironworks lived. The Ereborean District, carved back into the mountain and the rock beneath the city, its oldest and purest part, was where Gimli had spent so much of his life. It was strange for him to spend so much time looking upward, moving upward.

He'd changed, though. The war had changed him, the things he'd seen, the things Legolas had shown him. He had an idea, now, what that damage meant to the elves of New Rhovanion. He'd seen his elf's face when their train had finally pulled into sight of the city and the scars across its upper reaches had become obvious. He'd seen the blankness that had slipped into Legolas' eyes.

And somehow, because of it, here he was. Gimli Glóinson, an Ereborean dwarf born and bred, standing on a balcony on the side of the Greenwood Oropherion Tower, trying desperately not to think about how many hundreds of feet too high into the air he was. Below him, down at street level and just above it, the great central depot of the Iron Rail Company spewed trains out onto the raised tracks above Oakenshield Avenue, and lighter engines onto the magnetic monorails a few storeys above them. With the repaired mirrors on the upper reaches of the tower filling the street canyon with light almost all the way to the bottom, it was terrifyingly obvious exactly how many feet above that familiar sight he now was.

It wasn't the same, the heights compared to the depths. He'd looked into chasms hundreds of feet deep in Khazad-dûm without a qualm, the great bridge spans of the subterranean Dwarrowdelf inspiring more awe in him than terror. That had been no less of a fall. With the artificial electric suns, no less visible a one either. He knew that. It was just ... it was different up here. It was different on the surface, on one of the tallest towers in New Rhovanion, on some flimsy elven balcony that had blasted tree roots sticking out of the bottom of it. He could see half the city from here. More to the point, he could see how it was all beneath him.

He should have stayed inside, he thought desperately. He should have kept to the interior atrium. The balconies and rooftops and external terraces were the realms of the elves, but the towers that bore them all up were still dwarven construction. The internal shafts, insulated from the sheer external drop and lit exclusively by light refracted from above, had managed to stay comfortably subterranean in feel despite the best efforts of their human and elven occupants. Even the Greenwood Oropherion, the great bastion of Wilderland Elvendom, full of light and water and greenery and with as much of the exterior reaches open to the elements as elvenly possible, hadn't been able to disguise the solid, quintessentially dwarven nature of the stone it was built in.

Like. I feel like I did good there? I feel like that has teeth and potential. Heh. A dieselpunk fantasy city, with a lot of wars behind it, and a tentatively hopeful future.

And this little description of High Elven Councillor Thranduil:

He'd seen Thranduil Oropherion before, of course. Mostly in newsreels, but from a distance as well. The Elven High Councillor had a talent for being seen looking imperiously downwards from various heights, and had a particular fondness for the skycars and the aqueduct gondolas. He was easily recognisable, wearing those long, almost archaic greatcoats the elves favoured, all bronze and green, with his long golden hair bizarrely braided back with something that looked for all the world like live ivy. Even the most deep dwelling, surface-averse dwarves could recognise Thranduil on sight.

He looked a little different now. Some of it was the informality of his dress. Gimli was almost positive that few, if any, dwarves had ever seen the Elven Councillor in shirtsleeves and waistcoat before, his hair looped back into a tail that was, yes, held with an actual trailing plant, for reasons probably only an elf would know. It made him look smaller, somehow, maybe a little bit more fragile. Not quite the distant, impressive creature he usually appeared.

Why do I have so much more fun with worldbuilding and characters than I do with things like, you know, actual plot?

#fanfic#worldbuilding#my ego#lotr#dieselpunk#alternate universe#old fanfic#i like dieselpunk fantasy settings

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hither Yonder, Chapter 5

The Wild Roads

Halli awoke soon after sunrise, roused by the warming air and ground. She stirred, still sore from the night’s run and the fall that ended it. She sat up stiffly and listened for a while. Aside the pleasant sighing of boughs in the morning wind and distant bird calls the forest was silent, serene. She no longer feared capture, overtly at least, and took time to eat some of Sador’s provisions before starting off again. Climbing out of the ditch, she consulted the map as to her course. The Irdon forest, as it was named, stretched off west and south along the slopes of the Adorn mountains, the spine of Dumbria, running with them for many miles before ending at a sundered range called the South Spur, which formed the mountain-gap watched over by the fortress of Lake Tirgon. Rather than going immediately south-west and risk becoming lost in the forest, Halli went due-west toward the mountains, where she thought to have a sure marker to follow beside. Using any roads as a runaway slave was not an option.

This was the first course of her journey. Two days she spent walking into, then through, the heart of the forest, the mountains ever before her. The land rose gradually for the most part, then more so as she neared the pine and spruce-covered foothills of the range, rising in folds of green up and up to the bare flanks of the mountains proper, cloven by dales and valleys sheltered between rocky arms. Halli now went southerly west, on ground high enough to see down the surrounding lands, but low enough to avoid steeper terrain that would only hinder her. Away back east, in the fading light, she thought she could almost see the topmost battlements of Thargorod tiny and black on the far horizon, and thought of Sador and Siri in that moment. She wondered what punishment they stood to suffer because of her escape, if it would end with them. Here on the third day, more than on the previous two, the weight of her actions pressed on her shoulders as keenly as her roll-kit, and it was brought to her, concisely, what it would mean to be alone and to carry on. The sun set, leaving her under a blanket of night and stars.

The fourth day unfolded very much like the others; calm, boring even, in the shade of tall and ancient trees high enough to shut out the world beyond the forest. The air was scented with pine sap when the wind came in from the west. Northward, it smelled crisp from the mountain airs. Her aloneness was so apparent, the fear of being found completely left her.

By late afternoon Halli came to the source-waters of the Olgon River, the largest in Dumbria; a river she crossed once before, when the wagon train carrying her and Yuta rolled past its lowland fords to Thargorod. Here she refilled her water-skin, for it was fresh from the mountain springs, and stood about to take in her surroundings. The Olgon roared and splashed down bare stony banks worn smooth by its tide, falling downhill as rapids through ravines into the deeper forest. The foam glinted in the sunlight. The mountains were to her right, marching onward out of sight, catching the sky on their peaks as if they alone suspended it, keeping the separation of heaven and earth. The trees, clustered among the rocks, swayed in the mildest breeze, and she breathed it in.

Downstream from her, near the brink of the rapids, an ibex emerged from the trees and trotted to the river, fairly large, with great curved horns. Halli crouched low and watched him drink before deciding this an opportune time to test her bow. She unfurled her roll-kit and pulled it out slowly, bending it to notch the string. She had an arrow ready when she saw, lying stealthily on a shelf overlooking the bank, a mountain lioness in wait from above, her hind legs tensed for a jump. She sprang from her rocky perch and landed squarely on the ibex, who collapsed from the attack. He kicked and bleated, but she pinned him with a bite to the windpipe as he fought, then feebly writhed, then stilled. There was rustling in the trees behind; his pack heard his calls and bolted, bounding up to the safety of the steeper slopes. The lioness looked at Halli, who stood awestruck with her arrow slacked impotently on its string, suddenly feeling like prey herself.

“The kill is yours. I offer no contest.”

The lioness hauled her meal back into the wood, toward her mountain den undoubtedly nearby. That in mind, Halli crossed the shallow arm of the river by the spring and continued on her way.

Halli walked on in caution for the remaining day and those thereafter, while the forest lasted. Her bow was out, and she made a nightly shelter to help shield her from predatory eyes. Her guard lessened, however, when the forest began to open out, the hills only partly covered. Shrubs took advantage and grew in bunches in the glades, those that flowered and those that prickled. Ivy curled through them here and there, and little rodents scurried.

Nine days after entering the Irdon, the forest’s bulk finally thinned out to a few solitary pines along tumbled lands, and Halli could see the plains below. To the immediate south ran a separate range of hills, green and roving, the peaks grayish-brown and bare; the South Spur, a bulwark of rock across the neck of Dumbria. Just before her, a league away and beside the hills, was the fortress of Tirgon, unceasing in its watch of the plains. Calvary was afield in exercises, and white smokes wafted from the chimneys of barracks. There were no trains of slaves today, but Halli knew many more had come this way since she and Yuta went through its gates that summer long ago; Hananin from the steppes and the Kundish Mounds, and others from Ipsaria, Doria and beyond from Wilderland to the north. Halli backed into the sparse protection of Irdon’s westernmost reaches and went on her way, nursing blunted fantasies of revenge against that hated fortress.

Halli followed the flanks of a great shoulder in the range that hid her from the fortress, and down she went into the lower hills. Here Lake Tirgon sat against the mountains, buffered by a narrow and rocky land populated with holly bushes, beds of dry grasses and rough thickets. Trees were sparse, and were old and stunted. Nevertheless, this was Halli’s road as she chose it. The only other way, across the plains south of the lake, would mean almost certain capture while the cavalry was out.

She scrambled down the slopes and into a defile, going along ground that alternated between sandy, gravely, rocky, and sandy again. Her bare feet were sore before much trudging, yet on she went, walking through what grass she could find, stopping only a few times to rest. The lake at least was a beautiful bluish-gray, spanning many leagues south and west, ruffled by spouts of wind, otherwise reflecting mirror-like the mountain tips under a sapphire sky. The risk of exposure in this landscape was plain to her, but she took solace in one thing: there were no trails along Tirgon’s north banks, meaning this part of the mountains were seldom visited by the Dumbrians, maybe their soldiers too, despite the presence of their fortress. Halli certainly hoped it.

For two and a half days Halli plodded through that strip of waste, her palms, knees and soles callused by the rocks, and white from a chalky powder that coated the boulders and pebbly expanses. By noon she came to the eaves of the Farrow Wood, and her spirits lightened, not only because it meant an end to this unpleasant land, but also because past the woods was the West Reach, the extent of Dumbria’s borders. The borders of her own country were near.

The difference between the Farrow Wood and the mountain waste was abrupt. Up a few shelves of layered rock hung the roots of the outermost trees, stout and gnarled, at least by the lake. Further on, Halli saw taller, leaner trees as the land became less stony further west. She delighted in feeling the softer grasses under her feet again and decided to make camp early, resting and sleeping a long while.

Halli remained in the forest’s northern marches, to keep the mountains at her side. Then, after nearly fifteen days of constant hiking within the shadow of the Ardon range, over lands easy and difficult, they began to run down into a descent, hilly with many valleys, to the adjacent lowlands of the Hananin Steppes. The forest ended, and the Ardon sank into gentle rises. Here sprawled the West Reach, the beginning of the expansive, near featureless grasslands of inner Hinterland, bare under the noontime sun. Flatness, with subtle rolls, went off as far as the eye could see, except to the north where the Morrow Wood lay, a line of green against the wheat-color of the plains, and the Kundish Mounds further on. In the north, too, were brooding cloud fronts gray with rain, as colder airs from Wilderland mingled with warmer airs from the Sea of Ahn, rising to cumulus towers black-bottomed and foreboding, as far as they were. But this was not Halli’s road. From the eaves of Farrow, she turned south in a gradual meander westward, and came after a few day’s march under the Hinterland sun to the old Imperial Road.

The Road was built ages ago by the auxiliary legions of the Tarmaril Imperium in the years of its greatest extent, to connect the conquered lands with the mother-kingdom; to speed trade, culture, and the armies not the least. In those times the Imperial Road extended unbroken from the Sheerim Mountains to the gates of Tirgon, was tended to by a dedicated legion, and was punctuated every twenty miles with manmade watering holes. Every forty miles, or every other watering hole, was a courier station with inns, stables, and a fortified garrison.

In these later times, the Road was little more than an overgrown track of stones choked by weeds and grass, covered over entirely in some sections, marked along its way by the ruins of those courier stations and reed-studded pools frequented more by wildlife than any rider, much less a cavalry of thousands. Decay and disuse aside, the Road was not completely abandoned. After Tarmaril’s fall and the decline of Dumbria, the Hananin reclaimed their country and took from the Road what purpose they could find for it: irrigation ditches were dug to drain the watering holes for farmland, then blocked up for the spring rains to fill again, then drained as before. Stones were removed from the crumbling garrisons to build bridges and homes, though not from the Road itself. The Road was never repaired to its first glory, but parts of its length between villages were tended to and cleared, especially those parts near the Hills of Hanan and Lake Onu, where Hanan’s chief villages lay.

So Halli went west, following a way as sure as the mountains, though subtler. However, she walked along beside it at a distance, staying in the long grass; the threat of Dumbrian raiders still patrolling the West Reach was too great to ignore, making it unwise for her to travel directly on the Road. She remained a furlong’s breadth away day and night, far enough to dart and hide in the grass if need be.

And on she walked, and walked. The miles were covered in good pace, but there were many of them, each identical to the last. The occasional acacia tree was approached and passed, Halli using its dry, umbrella-like canopy for the shade it offered against the relentless sun when she rested, maybe twice a day for eating, seldom at length. She also came by several watering holes, or delves in the ground where one once was. They were brackish and warm, gathered over by birds and beasts; wild oxen and kingfishers, caribou and white flamingos migrating from the wetlands of Ahn. Even if she wished to use them, she doubted room would be made for her through their herds with so many young about, and under watch. Worse, the banks would be horribly muddy and mucked with filth by their tramping, making her think better of it than wasting one of Sador’s purifying tablets. And on she walked.

There was no marker or indicator to show where the West Reach ended and Hanan proper began, besides the words on her map. Halli guessed she was close; the lands here, hardly distinguishable to a traveler, were familiar to her as a local. She knew these fields. Her village was near here. As if to remind her of her present danger, not far off the Road was the site of a small homestead of yurts and tents. Their remnants, at least. Halli dared approach for a closer look. Burnt, brittle timbers and torn cloth were strewn everywhere. The people and their flocks were gone, the ground gouged and scorched in places. A few arrows stood staggered in the grass. This was not a fresh scene of massacre, however. The pillaging of this homestead was months ago, the bones of the slain picked clean by scavengers and carrion fowl.

Halli stood silent a moment, then pressed her hands together and bowed low, speaking softly and backing away. In Hananin tradition, a place of murder not purified remained unclean, and perilous for the living to trespass. This site would remain unclean for a long time yet, and Halli, in a mix of reverence and wariness, dared not disturb the uneasy sleep of the ill-rested.

Halli moved on, with no other sign of Dumbrian menace for the day’s remainder, or much of the next. She noticed that game was starting to become scarce around the watering holes, and that her food supplies were running low. Before she lost the chance, Halli camped by one of the pools and, after a short stalk, shot a heron through the reeds. She spent precious hours plucking the carcass and preparing a modest fire, gutting the entrails (an old chore she hadn’t really missed) and holding it suspended for the blood to drain, but it would be worth it. A good catch earns a good preparation, she remembered her barn’s caretaker telling her, and a good catch it was. Aside what she would eat today, there would still be enough to last her three or so more days, if she rationed it so.

Just as the bird was ready for spitting, Halli looked behind her shoulder to see a thin black line on the Road, growing to become a rank of black forms in the twilit evening. In the stillness, she heard the beat of hooves and the snorting of horses. It was Dumbrian cavalry, and they were riding fast, in her direction. Halli quickly blotted the fire and darted into the reeds, leaving her catch in the open.

The troop of horsemen, twenty with their captain, steered their horses to where they saw the faint wisp of smoke spied from afar, and dismounted to investigate. Halli watched them while hidden away. The captain sifted through the cinders with his boot, giving the plucked bird a kick into the soot. The rest ambled about, scanning the ground for clues to this riddle. Some murmured and pointed to imprints in the grass. They were fresh, meaning the one who made them, and made the meal, was nearby –but the light was fast fading, and Halli was well hid. They paced the spot a few more times, then as the stars outshone the slender gleam of orange against the west, they remounted and continued down the Road, leaving their riddle unsolved. What was one lowly Hananin vagabond to them? Their job was to scout the outer fields and return to Tirgon, and return they would. They galloped off in speed, leaving as swiftly as they approached.

Halli waited until the thudding of hooves was gone before coming out, checking over what was to be dinner and extra rations. It was dirty but salvageable, were she bold enough to start another fire. She risked her luck terribly already with the first, and decided not to again. Instead she resumed walking, feeling more secure in the cover of dark, wanting to put as many miles as she could between herself and the reach of Dumbria before the night ended.

On the days went, drawn, hot and trudging as before, with one noticeable change: the northerly thunderheads ever present against the horizon rolled down in haste on a southern gale, darkening the afternoon. Halli was relieved at first by the sun’s veiling, despite the thunder booming overhead, and welcomed the rain. She held her water-skin open to collect some of it, and it poured, and it blew. Then, it hailed. Halli wrapped her cloak tightly about herself and hunkered down, muttering as she was pelted, watching through her hood as the plains were pelted with little stinging balls of ice, waiting for it to pass. That was how the rest of that day went, shifting between rain and hail till early evening, when Halli found a battered acacia tree to sleep under. The night proved cold in her dampened cloak, her only protection against the wind. Come morning, she would welcome the humid sun.

Then, on the fourteenth day since leaving the Adorn range, Halli saw the rising shapes of the Hills of Hanan in the distance, and her heart lifted at the sight. An afternoon’s march, and she would come to villages outside Dumbria’s reach (she hoped) who could help her, refresh and restock her, give her rest and a little friendship. She was sick of being alone. By late afternoon she was at the Hill’s eastern ends, and wandered to the southern slopes toward Lake Onu blue and placid, crowded in by pockets of forest.

Halli looked on and frowned. The villages scattered across its banks appeared empty. She investigated each in turn, walking the dirt tracks branching to and off the Road openly, if cautiously. Long lanes ran beside tilled farmlands between fingers of forest, prepared for the planting season. The fields were abandoned, as were the villages; home, hut and barn. The livestock were also gone. Halli didn’t think this the work of Dumbrian raiders coming to collect slaves for Thargorod’s markets; none of the buildings were looted or torched, none of the fields ravaged. It was as if every villager to the last child had simply vanished.

Not quite. They had fled, and taken their livestock with them. News of incursions from the West Reach would have spread far and wide soon after the initial raids that took Halli and Yuta as spoils. That was almost a year ago. So the Hananin, most being semi-nomadic, gathered their livelihoods and mobile goods, and dispersed to wherever hope or safety led them within the Hinterlands, be it north to the eaves of Wilderland, or south to Kundanar, with whom they had a common ancestry. Anything that could be resown, rebuilt, or replaced was left where it was.

Halli lingered among the ghost towns, partly wanting to scavenge what supplies she could yet find, partly because she wanted to believe that they weren’t as empty as they seemed; that she might still find someone to give her tidings, or just talk to her. She peered into the houses, even exploring inside them, but saw only field mice nibbling on crumbs, and a few broken jars. The docks on Lake Onu were bare, moored with empty fishing rafts. Finding nothing else, Halli took some water from the wells for her water-skin, and continued on.

Westward on from the Hills of Hanan, the Imperial Road slanted a little north while keeping its heading, still dotted by watering holes, still watched over by crumbling outposts. The days were consistently bright and sunny without the threat of rain, a monotonous continuum of sunrise and sunset, with all the hours blurring into a plodding haze. Halli reckoned she was getting rather good at solitary marching, and even better at food rationing.

Before the Hills fell from sight, the long grasses gave way to shorter prairie ones, then failed altogether. The lands got tougher, with pasture shrubs becoming thistle thickets and other hardy weeds, and the occasional wildflower grove. Animal herds were sparse to nonexistent –though vultures could at times be seen wheeling about hither and yon, gliding on the high winds in a perpetual search for carrion. Now and again, Halli heard their lonely cries.

So came and went another eleven days; but on the morning of the twelfth, she saw rising suddenly over the flats of Hanan, purple in the wan light of dawn, the rugged peaks of the Sheerim Mountains, the border separating the Hinterlands from the Hither. Taller and mightier than the Adorn range, The Sheerim, where Halli stood, spread out in a great arc stretching north and south, falling with the bend of the horizon to immeasurable leagues. Though it didn’t mean an end to her journey, Halli was glad to see some change, any change, to the landscape, even if it was an obstacle so great, it suffered no rival formation this side of the world. As the map showed, it spanned over five hundred miles arm to arm, nearly sundering the two halves of the western continent. This would mean two-hundred and fifty miles just to go around, no matter which way she took –more months of joyless wandering, if not for one curious feature: right through the middle of the range was an opening in the mountains, called the Mistgap, which offered itself, on paper, as a most convenient shortcut. Halli didn’t have the rations to last going around the mountains, nor the patience at this point. It was either risk an unknown way, or possible starvation. As far as she made out, there wasn’t really a choice to be discerned. Besides, the Imperial Road continued right on up to the Mistgap on the map, and so maybe went through it as well. She put her faith in that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde Color Maps

Publisher: Bat in the Attic Games

Important Note: The PDF for the Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde Guidebook is included in this product. You only need to buy the separate guidebook if you want a print copy of the guidebook.

In 1976, Bob Bledsaw and Bill Owen went into business as Judges Guild. Their initial offering was centered on a magnificent 34" by 44" map of the City State of Invincible Overlord. First appearing at Gen Con IX, it was sold literally out of the trunk of a car during the convention.

This map launched Judges Guild which began working on even more ambitious project, the Wilderlands of High Fantasy. This became an ambitious project of 18 22" by 17" maps covering a total area 800 miles from west to east, and 1,000 miles from north to south. Each individual map was divided into 5 miles hexes covering an area of 260 miles west to east, and 170 miles from north to south.

Now forty years later those maps have been redrawn in full color. These maps preserves the original detail and applies known errata and corrections. Each was drawn as part of single 6 foot by 8 foot map encompassing the entire Wilderlands then subdivided and cropped.

These maps are not a scanned images of the original but have been redrawn from scratch. The guidebook is also not a scanned image but has been relaid out from the original text with errata and corrections applied.

The Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde Guidebook

This product contains a 38 page Guidebook for the five maps of the Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde. The books has an introduction and commentary by Robert S. Conley who has used the Wilderlands as his main fantasy campaign for nearly forty years. Each map is detailed with the following listings: Villages, Castles & Citadels, Idyllic Isles, Ruins & Relics, and Lurid Lairs.

This product contains

5 PDFs of the following 22" by 17" maps: City State of the World Emperor Map Six, Desert Lands Map Seven, Sea of Five Maps Map Eight, Elphand Lands Map Nine, and Lenap Map Ten.

1 PDF of the Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde.

The print option adds the following:

Ten overlapping full scale maps of each half of the maps.

There is a separate print product available for the Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde Guidebook if you want a print copy of the Guidebook. Otherwise the PDF for the guidebook is included in this product.

This product is a authorized Judges Guild release for the Wilderlands of High Fantasy.

Price: $9.99

Fantastic Wilderlands Beyonde Color Maps published first on https://supergalaxyrom.tumblr.com

0 notes

Photo

Source: Wilderlands Of High Fantasy (Books 1 & 2) (Judges Guild)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tweeted

Wilderlands of High Fantasy Judges Guild 1977 Dungeons & Dragons Book NO MAPS https://t.co/VScean6TMb #JudgesGuild #dungeonsanddragons #DnD #Vintage #TabletopGaming #Gaming #Gamer #WilderLandsOfHighFantasy #RPG #RolePlaying #1970s

— DRG (@eBayToHouse) January 7, 2019

0 notes

Text

Game 307: Legends of the Lost Realm (1989)

Legends of the Lost Realm

United States

Avalon Hill (developer and publisher)

Released in 1989 for Macintosh

Date Started: 26 October 2018

A few hours in to Legends of the Lost Realm, I’m trying to decide if the creators were just clueless or actually sadistic. Given that the developers never seem to have worked on another RPG before or after, I’m inclined towards the former, but I think I would find deliberate cruelty more forgivable. They basically started with the difficulty level of Wizardry, which featured permadeath, and then decided to make it harder.

Wizardry, for all its difficulty, did a good job balancing that difficulty with the occasional ray of hope. Sure, Level 1 characters got slaughtered so often that you had to replace your party about six times before you achieved any stability, but at least when you lost a combat, you only lost by a little. One fewer orc would have made the difference. The game didn’t pit you against three vampires and a basilisk right out of the main gate. It didn’t make you slowly die of hunger, thirst, and fatigue. When a character died, you probably couldn’t afford to resurrect him, but you didn’t have to pay extra gold for his burial. You didn’t have to go into debt to buy your starting equipment. There wasn’t a “tax man” roaming around who took a random percentage of your hard-earned gold. And Level 2 was maybe 5 battles away, not 50. All of those latter things are true of Legends of the Lost Realm.

Legends (subtitled A Gathering of Heroes in some places but not the title screen) takes place in the land of Tagor-Dal, a formerly peaceful kingdom that was conquered by neighboring Malakor 300 years ago. The characters are given as part of a Tagor-Dalian resistance, tasked with learning the forgotten ways of sword and sorcery, and with finding the last known remaining Staff of Power, which will hopefully throw off the Malakorian yoke. Legends of the Lost Realm II: Wilderlands, released the same year, is not a sequel but rather an expansion that requires the original game files. In it, the characters are able to explore an outdoor area to find two additional Staves of Power.

Exploring the hallways of the king’s citadel.

The developers clearly played both Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale, both of which featured permadeath and a clear distinction between saving the characters (back at a central location) and saving the party. The use of base and prestige classes comes from Wizardry, but the specific terms for the attributes, the spell names, the “review board,” and the use of spell points rather than slots seem more inspired by The Bard’s Tale. In either case, the developers deserve some credit for adding a lot of elements–the manual boasts that the game is “the most complete and accurate fantasy role-playing game every written”–although most of those elements just make the game more difficult and frustrating rather than adding enjoyment.

The player begins by creating a party of six characters (from a roster that can hold up to 30) from four base classes: fighter, thief, shaman, and magician. Later, they can switch to prestige classes of barbarian, samurai, blade master, monk, ninja, healer, enchanter, witch, and wizard. Attributes are strength, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, constitution, and luck, and although the values are technically from 3 to 18, the rolls are very generous and it’s easy to get two or three attributes at 18 and the others only a few points lower. Characters start with one weapon, one piece of armor, and 25 gold pieces. The roster is seeded with an existing Level 4 fighter named “Pete” that a player like me is determined not to use he actually starts playing and experiences the difficulty of early-game combat.

Character creation. Don’t be fooled by the equipment–that’s still showing from when I clicked on “Pete.”

The game starts in the barracks of the Citadel, the only place to save characters and store excess goods. Elsewhere on the main floor of the Citadel are a supply shop, an armory, a bank, a magic shop, several temples, and a “review board” for leveling and changing classes. In an interesting addition, you can buy items from the shops on credit, which is tracked in a “debt” statistic. You can pay off the debt at the bank, and if you don’t do so within a reasonable amount of time, you start getting attacked by thugs hired by the stores to collect. (Theoretically, anyway; I haven’t had it happen yet.)

Buying items in the armory. Apparently, it’s not a problem if I don’t have enough money.

Simply getting to these various locations is almost impossible at the first level because you keep running into enemies. “Retreat” almost always works when you do, but the game remembers the position and composition of enemy parties, so retreating doesn’t help much. You’ll still face the same party if you try to continue in that direction. It’s easy to get boxed in a corridor by two parties at either end that you cannot defeat.

Enemies on the first level include wild dogs, thieves, fighters, archers, and magicians, and they almost always seem to attack in multiple groups with at least 9 total foes. Combat uses a Wizardry base but is a bit different overall. Using radial buttons, each character chooses whether to attack, hide, cast a spell, or use an item. Only the first three characters can attack with regular weapons. You click “Attack” to begin the round. Your attacks are threaded with the enemies’ based on initiative rolls. But unlike Wizardry, you don’t specify what enemy to attack or cast spells against until the action executes in the combat.

Setting combat options against a group I have no chance of defeating.

I tried just about every combination of spells and moves available. I went into debt to buy shields and helms. And I still couldn’t survive even a single battle against any of the enemy parties that attack me on the first level. There are no easy combats with single fighters or three dogs. They’re all overwhelmingly deadly.

I finally gave in and added Pete to the party, and this allowed me to defeat a few groups, but my non-Pete characters were still vulnerable. I spent all of my money healing them at temples until I had no more money (you can’t heal or raise on credit), and one by one they died, and then finally Pete died.

It’s tempting to clear dead characters off your roster, but here the game introduces a new level of sadism: you have to pay to get rid of a dead character, with the cost shared among the characters who have money. And if that isn’t enough, every once in a while a “tax man” approaches the party, and if he thinks a particular character has too much gold, he takes something like 20%. Why would anyone add such an obnoxious element to a game? Did they not think it was “complete and accurate” without him?

With the corridors so deadly, I haven’t even been able to map the first level yet, but a map provided in the manual helps me fill in the holes. In addition to the shops I’ve described, there are four towers: the Magicians’ Keep, the Tower of War, the Thieves’ Tower, and the Tower of Pain. Each presumably has multiple levels. Each has a courtyard guarded by one high-level foe who gives you a chance to turn back when you enter. A message in a hallway on Level 1 tells me that “sixteen may be found, four in each corner tower.” However, there’s at least one more area accessible via the magic shop, and perhaps others beyond that.

Every major square has something fierce guarding it.

If I can survive for more than 15 minutes, the game promises some interesting elements to come. It supports dual- and multi-classing as well as completely changing classes. The prestige classes sound a lot cooler than their Wizardry counterparts, each with special abilities, such as berserking for the barbarian, critical and dual-wielding for the samurai and ninja, and the ability to cure poison and disease without spells for the healer. Blade masters can sharpen everyone’s weapons for extra damage. Thieves can try to pilfer enemy gold during combat. NPCs can join the party and assist in combat.

No first-person blobber would be complete without messages scrawled on the walls.

A lot of character types have special skills, both combat and non-combat, that can be “cast” like spells; for instance, the samurai can “cast” ARROW to make arrows, barbarians can HUNT for food, and thieves can CLIMB walls. Sorcerers can create their own spells by combining effects from the included spells. You can add modifiers to spell names to double their effects (and cost) or to force the character to wait until the end of the round to cast it.

But enjoying all of this requires that I get my characters to at least Level 4 or 5, and with Level 2 requiring 1,000 experience points, each successful battle delivering about 50 points, and my losing almost every battle, that seems like a long way off. I will be happy to take liberal hints from any player who has successfully gotten anywhere in this game.

Time so far: 3 hours

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/game-307-legends-of-the-lost-realm-1989/

0 notes

Text

After Hours: Wilderlands Vacation Special - Part 1

After Hours: Wilderlands Vacation Special – Part 1

The Wilderlands of High Fantasy is billed as the most detailed fantasy setting ever written. I own the boxed set, which contains 2 books (over 500 pages altogether) and 9 double-sided maps, depicting 18 regions. Each map has a hex grid and each hex is numbered. The books largely consists of descriptions of various hexes in each region. Wouldn’t it be amazing to have a vacation in the Wilderlands?…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

There are great piles of treasure in the crypts below the city, waiting to be plundered (Wes Crum, Tarantis, campaign supplement detailing a port city of pirates and merchants in the Wilderlands of High Fantasy setting for D&D or other fantasy RPGs, Judges Guild, 1983)

#D&D#Wes Crum#Dungeons & Dragons#Tarantis#Wilderlands of High Fantasy#Judges Guild#skeletons#undead#skeleton#dungeon#dnd#Wilderlands#City State campaign#campaign setting#treasure#treasure chest#treasure hoard#gp#Dungeons and Dragons#1980s

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

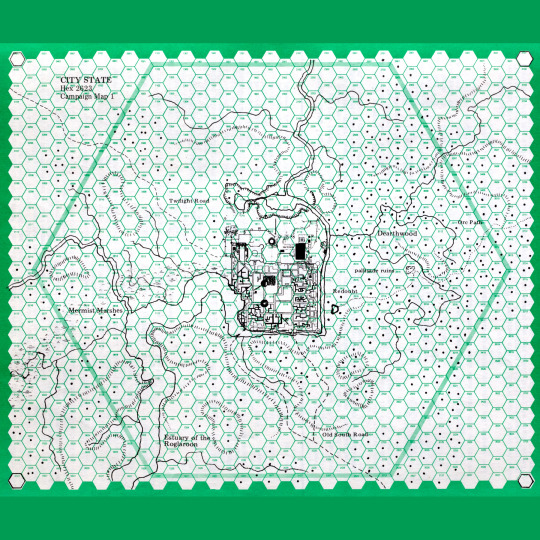

Smartly, around the same time they essentially created the hex crawl style of D&D exploration adventure with Wilderlands of High Fantasy (1977), Judges Guild realized that folks would need hex paper to fully enjoy the experience. Thus, the Campaign Hexagon System (1977), a booklet of blank hex paper. Thrilling!

So, D&D used a standard of five miles per hex. So, the big Wilderlands maps, those hexes are five miles across. These map sheets have a large hex superimposed over the small hexes that represents the 5-mile hex. The smaller hexes — all 625 of them — are 0.2 miles each (about the same length as a block in my town), allowing you to fill in the fine grain detail of the terrain. Or, maybe ultra-fine. Each big hex takes about an hour to traverse, so the number of hexes you’d go through feels like too many. While also feeling like maybe not enough. I have trouble with scaling this kind of abstraction, though, so maybe it is just me.

There are some random tables that supplement the Wilderlands tables. Other than that, though, just empty hexes here!

#RPG#TTRPG#Tabletop RPG#Roleplaying Game#D&D#dungeons & dragons#Judges Guild#Hex Map#Campaign Hexagon System

49 notes

·

View notes

Link

this is the real shit right here. do you want to create a fantasy area suitable for hex crawling with reasonable (probably not fully realistic) geography? this is your jam.

this also goes into detail on how much detail (see what i did there) you should put into various portions of the setting. it's pertinent to reference Wilderlands of High Fantasy!

0 notes

Text

When you roll randomly for your new character's starting gold sometimes you cant afford all the gear you want at 1st level (Kevin Siembieda, Tarantis, D&D campaign supplement in the Wilderlands of High Fantasy, Judges Guild, 1983)

#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#Kevin Siembieda#skeleton#dnd#Tarantis#Wilderlands of High Fantasy#Wilderlands#City State campaign#undead#ruins#loincloth#Dungeons and Dragons#1980s

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

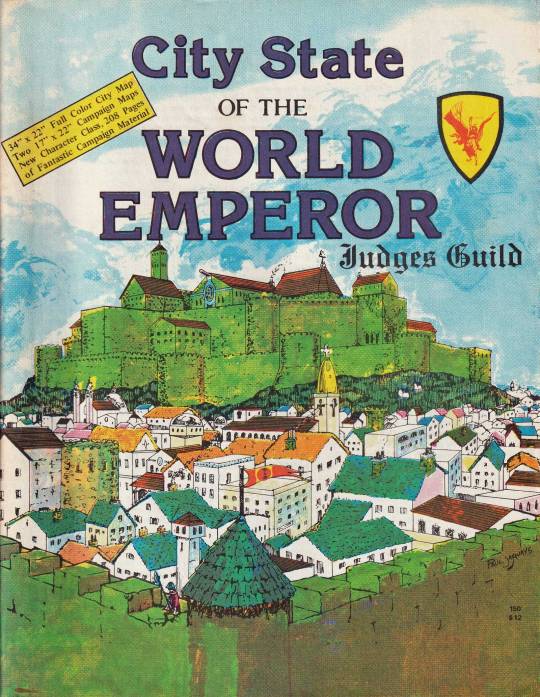

Viridistan, the City State of the World Emperor -- Jennell Jaquays cover for Judges Guild's 1980 campaign setting with 3 books and 3 large maps of the city and surrounding countryside, west of the City State of the Invincible Overlord, in the larger setting of the Wilderlands of High Fantasy, often called the "City State Campaign" (1982 fourth printing; designed by Creighton Hippenhammer and Bob Bledsaw)

#City State of the World Emperor#Jennell Jaquays#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#Judges Guild#fantasy city#City State Campaign#campaign setting#Wilderlands of High Fantasy#Creighton Hippenhammer#Bob Bledsaw#dnd#Viridistan#Dungeons and Dragons

130 notes

·

View notes