#Yuan dynasty

Text

portrait practice with the general

#yix gallery#digital art#ancient china#chinese eunuch#the radiant emperor#she who became the sun#he who drowned the world#general ouyang#yuan dynasty

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the largest conflicts in naval history, the Battle of Lake Poyang forever changed the course of medieval China. This monumental clash in 1363 AD, amidst the scenic expanse of Lake Poyang marked a pivotal moment in the rise of the Ming Dynasty.

This strategic battle unfolded against the backdrop of the Red Turban Rebellion, where former Buddhist monk Zhu Yuanzhang rose to challenge the Mongol-based Yuan Dynasty's rule. Amidst shifting alliances and power struggles, the battle unfolded as a clash of naval supremacy in the Yangtze River Basin when hundreds—if not thousands—of warships maneuvered amidst a storm of arrows and cannon fire. This epic clash has been remembered for the innovative tactics employed. From fire vessels to formidable tower ships, this was a testing ground for naval weapons which yielding devastating effects.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scalloped-Rim Dish with Cranes and Clouds

China, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

Bowl with sky-blue glaze and purple splashes, Jun ware [China, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)]

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

"Yuan art is Chinese art, but it is also part of a larger, pan-Asian phenomenon of Mongol culture that could only exist due to the geographic reach of the Mongol empire."

Eiren L. Shea - Mongol court dress, identity formation, and global exchange

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bottle with Peony Scroll, mid-14th century

Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), China

Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under a transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware)

H. 17 1/2 in. (44.5 cm)

The structured surface of this bottle ultimately derives from the Islamic cultures of West Asia. The designs painted on the surface of the bottle also illustrate the complicated ties between China and other regions in the fourteenth century: the patterns on the neck parallel the cloud-collar designs often found in textiles and clothing in China and the Islamic world; the scrolling peonies that decorate the center of the bottle derive from longstanding Chinese traditions; and the stylized lotus petals on the base allude to imagery found in Indo-Himalayan art.

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

#Chinese#Yuan dynasty#art#art history#ceramic#porcelain#Jingdezhen ware#monochrome#blue#cultural amalgam#pattern#design#textile art#flowers#peony#lotus#leaves#14th century#The Met#metropolitan museum of art

23 notes

·

View notes

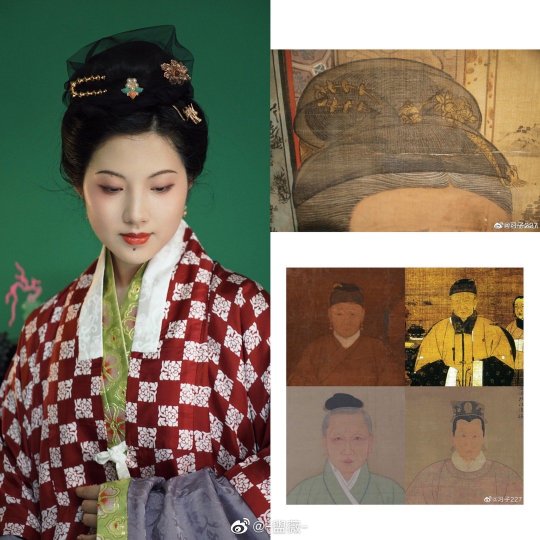

Photo

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

Portraits and Mural of Women in the Late Yuan-Early Ming Dynasties

Chinese Ming Dynasty Yongle period(1360–1424) Hanfu Relic: 长袖夹衣&素纱单裙

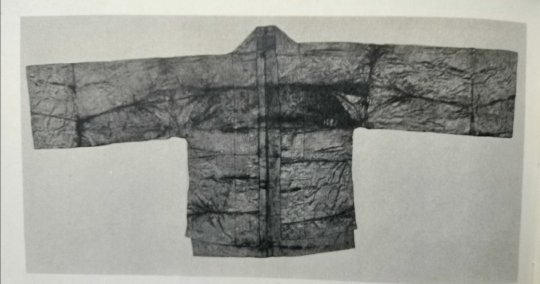

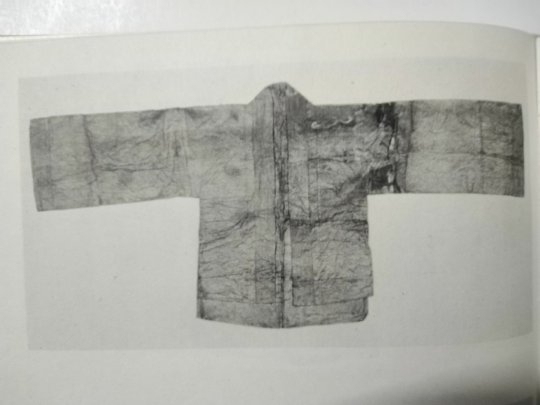

Yuan Dynasty Clothing Relics: 妆花凤戏牡丹纹绫夹衫,Unearthed from the tomb of Wang Shixian(汪世显)'s family in Zhang County,Gansu Provincial Museum Collection

Yuan Dynasty Clothing Relics: 印金团花图案夹衫

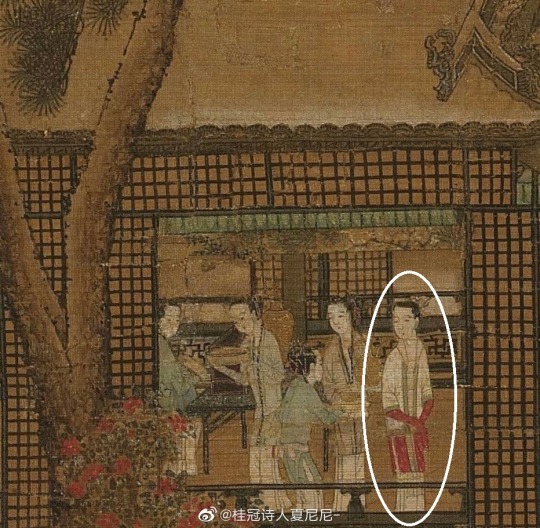

[Hanfu · 漢服]China Late Yuan to Early Ming Dynasties Traditional Clothing Hanfu Refer to Portraits and Mural of Women in the Late Yuan-Early Ming Dynasties

Typical styles of Han ethnic Women in the Late Yuan and Early Ming Dynasties

And it seen that the jacket has a certain connection with the jacket of the Southern Song Dynasty to some extent as blow:

Cotton jacket unearthed from the tomb of Huang Sheng(黄昇) in the Southern Song Dynasty in Fuzhou

Chinese Southern Song Dynasty Painting<仙馆秾花图>,Collection of National Palace Museum, Taipei

_______

📸Recreation Work: @-盥薇-

👗Hanfu: @YUNJIN云今

💎Earring:@江琛复古生活馆

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/3942003133/N6t86nHOM

_______

#chinese hanfu#Late Yuan and early Ming Dynasty#southern song dynasty#Yuan Dynasty#hanfu#chinese fashion#China History#historical fashion#historical hairstyles#hanfu accessories#-盥薇-#YUNJIN云今#@江琛复古生活馆#china

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Yuan Dynasty helmet, probably belonging to a high-ranking officer or general involved in the Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274. Invasion was unsuccessful due to typhoon which destroyed Mongolian fleet”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Turban Rebellion was a momentous event in Chinese history which took place from 1351 to 1368. Driven by social upheaval and Mongol oppression, peasants rose up under the Red Turban Society's banner, donning crimson turbans as symbols of resistance. Learn of their struggle for freedom, and the birth of the Ming Dynasty.

At the heart of the Red Turban Rebellion, Mongol rule collided with Han Chinese defiance. This is the story of how oppressive policies and cultural clashes ignited a revolution, leading peasants to take arms against their oppressors and using the red turban a powerful emblem of resistance.

Discover how Zhu Yuanzhang, a former monk turned revolutionary leader, united the masses, and overthrew the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. Delve into the legacy of this pivotal uprising, a reminder of the enduring quest for liberty and the resilience of the human spirit.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foliate Dish with Bovine (Xiniu) Gazing at a Crescent Moon

China, Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), late 13th century

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: The Troubled Empire

The Troubled Empire: China in the Ming and Yuan Dynasties, by Timothy Brook. I’m giving this history five out of five, this is exactly the ground-level info I wanted on climate, culture, and the rest of the time period for my points of historical divergence in Colors of Another Sky. And I plan to look up other books and articles by this author. Especially Vermeer’s Hat and everything he wrote on Xu Guangqi. For one thing, this author not only has an extensive bibliography, he sorts it into primary and secondary sources, so you can go straight to the source or read a myriad of interpretations....

Ahem. This is a book Jason would have read, given it covers large chunks of the Little Ice Age in Asia. That gives me not just world-background, but character background. If I take this book as “what he knows”, I then have a good basis for what he’ll see looking around in this world’s present and notice that things are Not Quite Right.

As you can imagine, I have sticky-notes all over my copy. Not just for Jason. Chae would have lived through about a third of these events!

...But mostly because there is so much neat stuff.

A few examples. The author pays particular attention to Chinese records of dragons. Because they were written down as real history, and accounts tend to coincide with upset, upheaval, and all kinds of nasty weather hitting the Empire in both Yuan and Ming.

And we often hear of Chinese referring to places to get rich overseas as “Gold Mountain”. But apparently gold was actually the civilized way to refer to silver. Which was money. Money coming from Spain and Portugal by way of galleons from South America... yet at the time, at least until about 1630, there was just as much silver coming to China from Japan. Especially since Japan had gotten hold of the mercury amalgam process from foreign traders.

(Chae is probably several kinds of ticked about that. She’s a cultivator, from a tradition that now actually works; she knows how nasty cinnabar really is.)

Not to mention that in times when things were going well, and there were times even in the Little Ice Age that it was... there were markets for antiquities that, somehow, always had a few more antiques laying around to show wealthy collectors. To the point that some collectors found spotting the fakes to be part of their fun!

One of the facts I want to chew more on (which also agrees with bits of a book on William Adams, who was in Japan in late Ming) is the fact that mathematics, particularly geometry that helped shape maps, astrological calculations, and artillery fire, is one of the things China and Japan both found most impressive about European areas of knowledge. Hmm.

All told this book is fascinating. I’m definitely going to reread it, and it’s giving me lots of story fodder!

7 notes

·

View notes

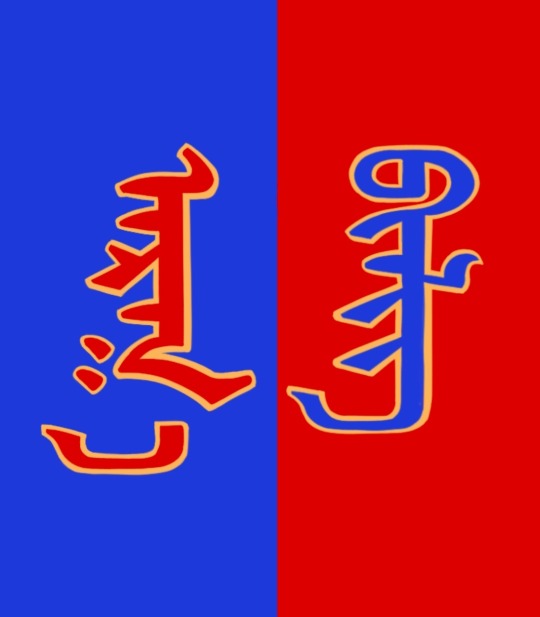

Text

Safe conduct pass stating that the bearer is under the protection of the Mongol Empire, Yuan Dynasty, 13th century

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

825 notes

·

View notes

Text

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

273 notes

·

View notes