#academic Publishing

Text

Himalayan Linguistics turns 20: Celebrating two decades of Diamond Open Access publish

The publication of Himalayan Linguistics issue 23(1) marks 20 years of the journal. To celebrate this milestone, the current team of editors, including myself, teamed up with two key former editors to write a special editorial about the history of the journal. Below are some excerpts from this history, as well as the article list for HL23(1) and a newly published Archives piece.

In early 2004, the first issue of Himalayan Linguistics was published. This first issue contained a single article: “An Analysis of Syntax and Prosody Interactions in a Dolakhā Newar: Rendition of The Mahābhārata”, by Carol Genetti and Keith Slater. In 2024, with the publication of Issue 23.1, Himalayan Linguistics celebrates twenty years of publishing fee-free Open Access research scholarship on the languages of the Himalayas. In these twenty years, Himalayan Linguistics has published almost 200 pieces of scholarship, all freely available online. In this special introductory article, we chart the history of the journal and look to its future.

In its twenty years of publication, Himalayan Linguistics has published 144 original research articles, 18 review articles, and 14 Archive and Field Reports. The Archive publications include grammars, dictionaries, text collections and extended descriptive works.

Himalayan Linguistics is well-placed to continue into the next twenty years. Indeed, the need for accessible online journals, which do not gatekeep with article processing charges, is even greater. The rise of digital-first research publication has seen an even contraction and concentration in the publishing market, which is now predominantly an oligopoly of a few giant commercial publishers (Larivière et al. 2015). This landscape creates a barrier, particularly for scholars who cannot afford processing fees.

Himalayan Linguistics, Volume 23, Issue 1, 2024

Editorial: Twenty years of Himalayan Linguistics

Lauren Gawne, Gregory Anderson, You-Jing Lin, Kristine A. Hildebrandt, Carol Genetti,

Spoken and sung vowels produced by bilingual Nepali speakers: A brief comparison

Arnav Darnal,

A corpus-based study of cassifiers and measure words in Khortha

Netra P. Paudyal

The grammar and meaning of atemporal complement clauses in Assamese: A cognitive linguistics approach

Bisalakshi Sawarni, Gautam K. Borah

Possessive prefixes in Proto-Kusunda

Augie Spendley

Expressing inner sensations in Denjongke: A contrast with the general Tibetic pattern

Juha Sakari Yliniemi

New in Archives and Field Reports

Facts and attitudes: on the so-called ‘factual’ markers of the modern Tibetic languages [HL ARCHIVE 14]

Bettina Zeisler

You can read all of Himalayan Linguistics, always Open Access at: https://escholarship.org/uc/himalayanlinguistics

#linguistics#language#journal#open access#Himalayan Linguistics#academic publishing#diamond open access#research article

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

An analogy for academic publishing (as used to explain it to my roommate):

You are a Twitch streamer. You are hired by a separate company to a) do your stream and b) teach newbies how to play the games you stream.

You are expected to help with the administrative work for the company paying you. You receive no additional pay for this work.

Twitch keeps all of the money that you make on their platform. They take almost all rights to your streaming, and charge so much to view it that you cannot afford to do so. You are not allowed to cross-publish your stream to another platform.

If you need money to upgrade your equipment for newer games, you have to beg your company or another organization (often a game publisher) to give you that money. If you get money from a game publisher, they are likely to pressure you to give excellent reviews for their game on stream. Twitch will not give you any funding for this.

You are further expected to moderate other people's streams to ensure that they meet the quality standards that Twitch expects. You receive no compensation for this work.

Your own stream is moderated in this way. If the mods decide (based on their own standards for what the quality of streams should be) that your stream is not good enough, your stream will be canceled. If your stream is canceled, you will be fired by the company that is actually paying you.

If your stream is not popular enough on Twitch, you will be fired by the company that is actually paying you. If you only manage to get your stream picked up by a streaming service less prestigious than Twitch, you will be fired by the company that is actually paying you.

You have thousands of dollars of debt, because that is the only way you could afford to have someone else teach you how to play the games you are streaming. You can theoretically stream on Twitch if you are self-taught, but they still will not pay you, and the companies pay streamers will not hire you.

There are an extremely limited number of paying positions for streamers. You can take work just teaching new gamers how to play, but you will be paid in peanuts.

Everyone insists that this is the only possible way to ensure that streams are high-quality.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source: Pullum 1984: Punctuation and human freedom

#linguistics#linguisthumor#lingblr#typography#copyediting#academic publishing#linguist humor#punctuation marks

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really, truly hope this case results in some positive changes. These publishers have had a stranglehold on academic publishing and budgets for far too long.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Got a crush on the really cool professor in my major that I absolutely do not expect to go anywhere but I see other students be normal friendly with him and want to do that too without exposing my horrific secret, what do I do?

what you need to do is put him on the back foot as much as possible. best way to do this is to confuse him with whatever slang is too new or too online for him to be aware of. use this constantly in his presence so he's always thinking damn, i'm not hot shit at all, i don't even know what this student is saying to me. knock him down a few pegs.

another thing i think you should do is look up his publications. see if he has beef with any other academics in the field (has anyone written a letter to the editor disagreeing with one of his articles? if he's submitted to journals that publish reviewer comments, has he gotten any scathing peer reviews?), then cite his nemeses incessantly in your papers. has he published in the field's high-impact factor journals? if not, ask him for tips on getting published. (this is like "do you even lift, bro?" but for academics.) if you're not comfortable saying any of this stuff to him, it should be sufficient just to have the information yourself. you need to reduce the mental real estate allocated to being impressed with him. if you cut him down to size, chances are your crush will diminish proportionately and then you can act like a regular human in his presence.

#damn it was really hard not to give good advice to this one and the last one but we're not here for that are we#as it is this is dangerously close to being regular advice. it has a nugget of truth#asks#anon#academic publishing#dear imprudence

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I get contradictory comments from my peer reviewers...

#phd#phd life#phd life in gifs#grad#grad school#academia#college#university#publishing#Academic publishing#academic life#research#peer review#succession#cousin greg

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

where would i be able to read your monograph? especially about the ‘you are nothing without me’ incident

The Protracted Reality of Writing Academic Shit 😂

First, and assuming the asker means my Hephaistion-Krateros book, the quick answer is: It’s still in process, not even close to being in print. In the meantime, a number of my articles are available on academia-edu.

Now, to explain why the book is “still in process,” let me explain the monograph writing progression. IME, the average person uninvolved in academia is often surprised by the sheer complexity and time involved. (After all, why would you know if you don't need to?)

Below, I talk only about academic monographs, although I’ve also edited academic collections, and of course, have published a number of articles. I started to tackle fiction publishing too, but that quickly devolved into a long-ass post (even for me), so I’m sticking only to the topic the asker requested. It's long enough! Maybe I’ll do fiction later, assuming anybody wants to read that. (If so, put it in an ask.)

To write an academic book in the humanities typically takes years. There are several stages just to produce the initial manuscript, never mind getting it into print. I’ll outline the general process below, using my current project to illustrate the steps. One thing I’ve found consistently among both students and non-academics is utter surprise at just how extensive research/writing is. New grad students often think writing a thesis/dissertation is akin to writing a really long term paper. Oh, no. You will write it, submit it, get critique and feedback, go research some more and revise it, get critique and feedback, go and research yet more and revise it again … rinse and repeat. How long? Until it’s cooked. There’s not a set timeframe. It will always take longer than you expect. Always. I’ve been teaching grad students almost 25 years. I have yet to have any require less time than they first assumed.

Writing a monograph (including the thesis/dissertation, which is a type of monograph) is one of the toughest forms of academic writing. Papers/articles are much easier, and not just because they’re shorter, although that’s some of it. They also generally have a simpler point. They’re proving ONE thing, like a string.

A monograph presents a coherent, complex argument like a rope woven from several strings (the chapters). It’s not an edited collection by multiple authors in a single volume (or two), or even a collection of various essays by a single author. Collections may have a general topic, like, say, Macedonian Legacies (the collection we did for Gene Borza), or the one I’m editing now, Macedon and It’s Influences. Just trying to figure out a decent order for the varied papers can prove a challenge in these. If some of the papers actually do bear on each other … bonus! But the papers aren’t necessarily expected to come together at the end in any cogent way. A monograph’s concluding chapter should, however, bring together the chapters into a solid conclusion, like the arch’s capstone, holding it all together.

Yet the researcher may not know the answer to that until done with much of the research. After reading everything, and considering it, she may wind up in a different place from where she started. Like any good, responsible research, the researcher must be prepared to follow the data and facts, not cram them into a preconceived notion. I’ve changed some of my ideas and goals for my current monograph, as I no longer think I can do the project I originally intended because the nature of the sources get in the way too much. But I have a more interesting project as a result.

The first phase is research: pretty much for any academic field, period. How this progresses, and how quickly, varies with the individual, field, and topic. Furthermore, some of us are planners (that’s me), others are pantsers (e.g., they dive in and figure it out as they go: by the seat of the pants). But we all start with a question or observation, then go out to track down information about it. In history, sometimes we just read the primary sources/archival material and see what we find. Something strikes us, so we go on to read more, which produces either refined questions or entirely new ones.

Right now, I’m finishing up the initial stages of the research. Then I’ll start work on the chapters, which, yes, I’ve outlined as a result of my initial research. But those chapters may (and probably will) morph as I write them. It’s during the writing phase that the other, “attendant” research comes into play: chasing down all the references in other secondary sources for smaller points. Rabbit-hole time.

My initial research tends to be more measured. I read a while, stop to think—sometimes do stuff like write replies to asks on Tumblr while my brain churns. 😉 Then I go back and read some more. But the writing phase is where I can lose all track of time while running down just-one-more-citation-then-I’ll-stop. The last time I looked at a clock it was 3pm and now it’s 9pm, I’m weak with hunger, I really have to pee because I’m drinking too much tea, and the cats are mad because I’ve not fed them in hours. 😆 It’s two really different types of research for me.

Anyway, for the initial (pre-writing) stage, there are really two substages. The first is what I think of as archival work: e.g., getting down and dirty with the original (primary) sources, including digging into the Greek and Latin to see what it actually says, and if there’s something noteworthy in the phrasing. At this point, I may not really know what I’m looking for, except in the broadest sense. For my current project, I collected every single mention of Hephaistion and Krateros in the original sources. For all five ATG bios, I read them front to back, tagging all sorts of things, plus large chunks of important other books (e.g., the first part of book 18 of Diodoros, the extant fragments of Arrian’s After Alexander, plus a couple bios, esp. Plutarch’s Eumenes, etc.) in order to get a FLOW, not just collect things piecemeal. There are some passages that may not name Hephaistion or Krateros specifically, but they would include them. Piecemeal will always be incomplete, like trying to see a clear image in a broken mirror (a mistake I made with my dissertation, in fact, but I was young).

Then I assembled all that collected data on huge sheets, arranged by author for each man, so I can cross-reference and compare. I also did a deep-dive across 4 days, grabbing everything in Brill’s New Jacoby (BNJ), so I can also tag the original (lost) author cited in our surviving sources, where we know who it is. Not actually that many, but it’s useful and can prove significant. I want to see where the same information, or anecdote, crosses sources, and how it changes.

All of that (except adding the BNJ entry #s to my big sheets) is now done. The next step is figuring out what it all means. For that—and where I am right now—involves historiographic reading/rereading of secondary sources on the ancient authors. What is Curtius’s methodology? Arrian’s? Plutarch’s? What are the themes of each? What is the story they’re telling? They’re not just cut-and-pasters from the original (now lost) histories; they have agendas. What are they? How do Hephaistion and Krateros fit into those agendas? How do the sources use them? This is, to me, the really interesting piece.

It's also why this book will not be just a cleaned-up version of my dissertation, but a completely new look at Hephaistion, and now Krateros too. I haven’t even consulted my old dissertation chapters. I started over from scratch. Sure, I remember my main conclusions, and as I write, I’m sure I’ll go back to check things, but the same as I’d check anybody else’s.

I’d hoped to start writing by May, but I’m not quite there yet, in part because, between the Netflix series plus helping to write/edit a grant that I didn’t expect to have to do, I lost virtually all of February. Now, about half of April has been eaten by home repair/yard stuff plus small family crises. That’s just the nature of a sabbatical, especially if you don’t have a spousal unit or SO to take care of everything for you while you just write. 😒

Now I hope to start writing by mid/late May. But as this 9th International ATG Symposium is looming in early September, plus I go back to teaching in the fall, I’ll have to knock off by the end of July, if not sooner. Ergo, not a long writing time. I can do some more during winter break, but I probably won’t have a draft done until next summer. If I’m lucky. It is just not possible, at least for me, to write while teaching! As I do plan to present at least one (startling!) piece of my research as the ATG conference, I have a concrete deadline for a subchapter bit. Ha.

So, what happens after a draft is done? Well, if one is smart, one finds a reader or three. One just to read it for sense, but (if possible) another specialist to start poking holes in the arguments, noting secondary sources one forgot, and to offer general pushback in order to refine it all. This assumes your friends/colleagues actually have time to look at it, as they, also, are teaching and writing their own stuff. (I’ll go after my retired colleagues.) At the same time, one may also begin seeking an academic publisher.

It’s important to match the project to what the publisher is already publishing. It can also help, but isn’t necessary, to have an in: somebody known to/trusted by the editor of one’s broad field (ancient history, in my case) who can vouch for the scholarship. Submitting means writing up a summary of the work, perhaps including letters from colleagues/readers, etc., etc. I’m not even close to this stage yet, so I’m primarily going by the experiences of friends. At this point, it starts to dovetail a bit with fiction publishing. You’re on the hunt and do some of the same homework.

Once a publishing house requests the manuscript, they’ll farm it out to 2-3 readers to evaluate. This is the “refereed” part, as the readers will be specialists in the field. The publisher, who can’t be a specialist in everything, may ask for a list of names for these potential readers.

As with academic papers/book chapters, the book will come back from these readers with a vote on publishability, plus suggestions for improvement. The basic choices range from, “Go back to the drawing board; this has major issues and here they are” (e.g., not ready yet for publication). To, “It’s got good bones but here are improvements on chpts X and X, oh, and go read ___ works you forgot,” (e.g., revise and resubmit). To, “this is pretty solid as-is but could use a few more things” (e.g., revise but ready for a contract). You will NEVER get a “Publish it right now.” 🤣 It’s hard to say how much time this revising phase will take, as it depends entirely on the level of revisions requested. This is why it’s often wise to find a reader or three in advance, to make this phase less lengthy. Yes, books do sometimes get turned down entirely, with no “revise-and-resubmit,” but more often it’s one of the three above. And yes, sometimes an author may be unwilling to make the requested changes, so finds a different publisher, with different readers, hoping for a more positive outcome. Sometimes, with the revising stage, there’s a non-binding contract involved, but this seems to be usefully mostly for younger scholars who need some sort of proof for their RPT (Reappointment, Promotion and Tenure) committees.

Once a publisher gets a manuscript they believe is worthy, the author receives a (real) contract and is provided with in-house editors to fix grammar, sense, etc.: copy- and line-editing. What would (in fiction) be called “developmental editing” is what the refereed part entailed. This is the simple part. Getting TO the contract stage is the tough part.

The publishing house will then schedule the book with a publication date and discuss things like page-proofs, cover art, permissions, formatting, etc., including indexing, which most publishers either don’t do, or charge a high fee for. It’s almost always cheaper to hire an indexer separately. I’ve already got mine lined up for the Hephaistion-Krateros book. But that can’t be done until it’s typeset and through page-proofs as one needs, yeah, the page numbers. Ha. From contract to the book hitting shelves can take a full year, or more.

So, with the exception of those folks who are just writing machines, the average monograph is c. 5+ years, at least in the humanities. This assumes the luck to get a sabbatical, not trying to do it all crammed into summers or breaks.

So yes, I’m still a couple years from this book seeing print. And that assumes there’s not a lengthy revise-and-resubmit process because my readers don’t like my conclusions.

#asks#Hephaistion#Krateros#monograph on Hephaistion and Krateros#Hephaestion#Alexander the Great#writing an academic monograph#academic publishing#Macedonian Court

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am so envious of people whose brains don’t jump from zero to panic at the drop of a hat. Because my current new panic of the day is about how I had my dissertation participants read/watch and react to excerpts from two books and one tv show and now I’m convinced I’m going to be sued for copyright violations by two major publishers and Netflix for using their content.

And why did this come up? Because I was like “I should do the right thing and request permission to add the written excerpts to my appendices” and now I’m freaking out (irrationally) that they’re going to penalize me for using them in the first place. I didn’t even send participants a copy because I just shared my screen. Logically, I know that this doesn’t violate copyright but my brain has dug its anxiety claws into proving that wrong. Why is copyright law so terrifying?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resources for Academic Publishing

This post I made a while back got quite popular. One of the things that showed up often in the tags is "what about paying for academic publishing?"

Basically, the same idea applies. If a journal approaches you and says "hey, we'll publish your article super fast and your just need to pay us this fee," be wary. Academic publishing is slow by design to allow for the peer review process. Predatory journals will take your money and publish your article, but skip the peer review process that makes sure your research is sound. So if you publish with them, not only will you be out a boatload of money, but your integrity as a researcher will be tainted.

That being said, there are many academic journals that do charge fees to publish with them. This article does a good job explaining the different fees that a journal might have.

Since we live in a capitalist society, academic publishers need to make money. To do this, they have to charge the reader and/or the author. Because the potential audience of an academic article is much smaller than the potential audience for, say, the latest vampire romance, publishers by necessity often have to charge authors to publish.

In the rest of this very long post, I'll try my best to give you an overview of ways to publish your research without breaking the bank.

So what's an aspiring academic to do? You are probably not swimming in cash (I just finished grad school, l feel your pain). That's where the magical world of grants comes in. If you are associated with a college or university, see if they offer publication grants. These are often administered through the library, but they can also be available by a department. At my university, the Graduate and Professional Student Association offered quarterly publication grants of up to $1,200 for graduation students to publish their research. There were several funding cycles a year where nobody would apply, which was always sad. There's money out there, if you know where to look!

Also look at professional organizations in your field. Many offer financial assistance to graduate students through grants or fellowships. When you are applying for a grant, make sure to include publishing expenses in your cost breakdown!! This is something that so many people forget to do. And don't just look at the biggest, national/international organizations in your field. There are probably smaller regional organizations that offer funding as well, and they probably aren't as competitive as those national ones.

A pro tip from me is to think outside of the box in terms of what grants/fellowships you apply to. For example, my research focus is the historical archaeology of caves in the southeast US. So I can apply to grants for research in archaeology, caves, history, historical archaeology, cave archaeology, cave history, southeast American history, southeast American archaeology, etc. Look at your research topic and make a list of all of the different umbrellas it can fit under. Then search for organizations that are related to those projects. You might be surprised by what's out there! And if you're unsure if you research topic fits into the scope of a program, it never hurts to send the coordinator a quick email.

Another option is to carefully consider what journals you submit to. A highly prestigious journal is likely to have higher fees than a less prestigious one. As long as your article is peer reviewed, the prestige of a journal is not as important as you might think (The only time is might be important is if you're trying to get tenure).

If you take nothing else from this post, take this: do not self reject! Imposter syndrome is real, and you might feel that you don't deserve funding. That's the devil talking. You, my friend, are an academic badass. Your research is awesome, you're awesome, and you deserve to share your awesomeness with the world. So apply to that grant, even if you don't think you'll get it. You might be surprised.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's celebrate World Environment Day!

And reinforce our commitment this year's theme of World Environment Day - Land restoration, desertification and drought resilience and preserve nature and natural resources! Get to know how to fulfill this commitment through our books. https://shorturl.at/WwcuF

#phibooks#philearning#phibookclub#phi#eee#Eastern Economy Edition#college textbooks#textbook publishing#academic publishing#education#books#undergraduate#environmental science#biodiversity#renewable energy

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

43 notes

·

View notes

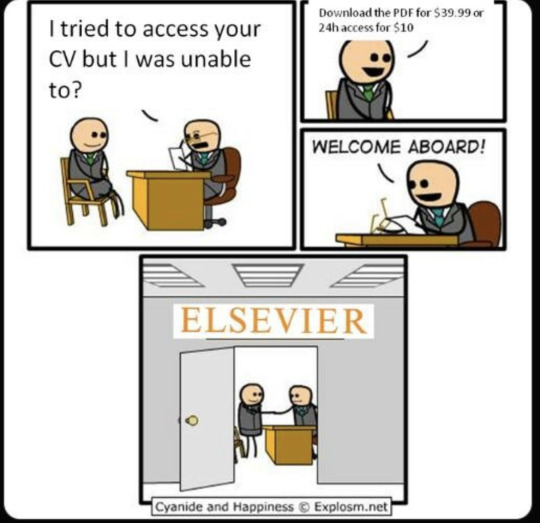

Text

Source

#linguistics#academia#academic publishing#elsevier#academia life#academic writing#publishing#open access

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

An academic question for youse. I'm reading about "grey literature" for work, i.e. material not produced by commercial publishers, and it includes conference proceedings as an example. But then it says that grey literature is not peer reviewed. I've submitted twice to conference proceedings and both articles have undergone peer review; I also know of conference papers that have been rejected by peer reviewers, suggesting a level of selectivity. When it comes to citing articles, I've never particularly distinguished between conference proceedings and journals, as in my field they seem to fulfil very similar functions.

Is this medieval studies being weird and other fields having a wildly different approach, or is this a broader STEM/humanities difference? Or is this page simply incorrect?

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having been wholly and completely immersed in academia for the past three months, I can confirm three very important and three very related things:

1. Academics fucking love when people want to read their work.

2. Authors don’t get any money from subscriptions to journals they’re published in.

3. Because paywalls directly prevent people from reading their work, authors tend not to like paywalls; similarly, because they receive 0 money from having their work paywalled, they have 0 incentive to encourage subscriptions. In many cases, authors will actively subvert the paywall by posting the article elsewhere or just... sending it to anyone who asks.

So tl;dr literally if you want an article, see if one of the authors has uploaded it to Researchgate. If not, email the authors and ask for them to send it to you.

It’s almost a guarantee that (if they see your email and answer it) they will happily send you the article and maybe a few others that they like. They probably hate paywalls as much as you do and will happily stick it to the greedy subscription journals that limit the paper’s potential audience.

#academia#academic publishing#academic articles#i know this has been said before on this website#but I think it bears repeating.#scientists WANT you to read their work#they don't WANT it to be limited to other academics#if you take the time to contact someone to tell them that you want to read their paper#it will make their entire fucking month

13 notes

·

View notes