#american institute for marxist studies

Text

I keep on saying that historians ARE looking at what you want them to but a lot of it is behind paywalls and not in your high school curricula or tbqh many museums but! here's a collection of freely available research from academics on normal people over the centuries (mainly british and imperial history because language and sources etc).

Obv I've only read a couple examples but yay it exists without institutional access needed, is short, and pretty accessibly written. Things like Henry VIII's Black African trumpeter petitioning for a pay rise, the life of a 17th century woman from being apprenticed by her stepfather's executor to making caps to turning to begging, or a servant testifying as a "voluntary prostitute" in the sodomy trial of his aristocratic master.

#little case studies of the type of history that I try to focus on#it's only a fragment but it's what you can get from unpaid spare time and only published out of a conviction that it /should/ be available#ghost.post#now i will say in critiques of historians: American historians have a tendency to not do this type of history from below work#but that's another can of worms and there is loads of actually challenging American history research out there mainly from black historians#(history from below came from british marxist historians so it uh... didn't catch on at many us institutions lmao)

0 notes

Text

The Unofficial Black History Book

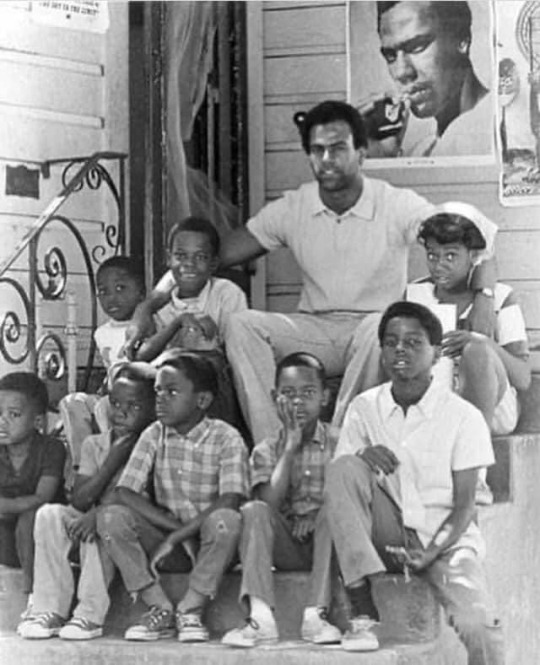

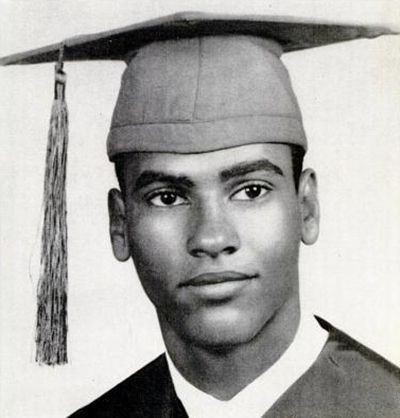

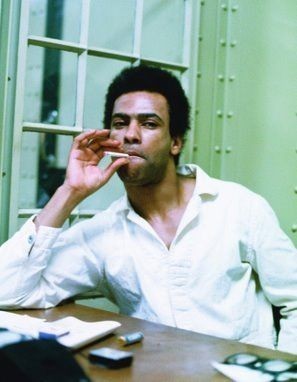

Huey P. Newton (1942-1989)

'The Revolution has always been in the hands of the young. The young always inherit the revolution.' - Huey Newton

This is his story.

Huey Percy Newton was born on February 17th, 1942, in Monroe, Louisiana. The youngest of seven children to Armelia Johnson and Walter Newton, he was named after former Governor of Louisiana, Huey Long.

His family relocated to Oakland, California, in search of better economic opportunities in 1945. His family struggled financially and frequently relocated, but he never went hungry or homeless.

Growing up in Oakland, Newton recalled his white teachers making him feel ashamed for being African-American, despite never being taught anything useful. In his Autobiography, ‘Revolutionary Suicide’, he wrote – “Was made to feel ashamed of being black. During those long years in Oakland Public Schools, I did not have one teacher who taught me anything relevant to my own life or experience. Not one instructor ever awoke in me a desire to learn more or to question or to explore the worlds of literature, science, and history. All they did was try to rob me of the sense of my own uniqueness and worth, and in the process nearly killed my urge to inquire.”

He also had a troubled childhood; he was arrested several times as a teenager for gun possession and vandalism.

Huey was illiterate when he graduated from high school, but he taught himself to read and write by studying poetry before enrolling at Merritt College.

During his time there, he supported himself by breaking into homes in Oakland and Berkeley Hills and committing other minor offenses. He also attended Oakland College and San Francisco Law School, ostensibly to improve his criminal skills.

He joined Pi Beta Sigma Fraternity while still a student at Merritt College and met Bobby Seale, a political activist and engineer. Huey also fought for curriculum diversification, the hiring of more black instructors, and involvement in local political activities in the Bay Area.

In addition, he was exposed to a rising tide of Black Nationalism and briefly joined the Afro-American Association, where he studied Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, Mao Zedong, E. Franklin Frazier, James Baldwin, Karl Marx, and Vladimir Lenin.

Huey had adopted a Marxist/Leninist viewpoint in which he saw the black community as an internal colony ruled by outside forces such as white businessmen, City Hall, and the police. In October 1966, he and Bobby Seale founded The Black Panther Party for self-defense, believing that the black working class needed to seize control of the institutions that most affected their community.

It was a coin toss that resulted in Newton becoming defense minister and Seale becoming chairman of the Black Panther Party. Newton’s job as the Minister of Defense and main leader of the Black Panther Party was to write in the Ten-Point Program, the founding document of the Party, and he demanded that blacks need the “Power to determine the destiny of our Black Community”. It would allow blacks to gain “Land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.”

The Panthers took advantage of a California law allowing people to carry non-concealed weapons and established armed patrols that monitored police activity in the Black Community.

One of the main points of focus for the Black Panther Party was the right to self-defense. Newton believed and preached that sometimes violence, or even the threat of violence, is required to achieve one's goals.

Members of the Black Panther Party once stormed the California Legislature while fully armed in order to protest the outcome of a gun bill.

Newton also established the Free Breakfast for Children Program, martial arts training for teenagers, and educational programs for children from low-income families.

The Black Panthers believed that in the Black struggle for justice, violence or the potential for violence may be necessary.

The Black Panthers had chapters in several major cities and over 2,000 members. Members became involved in several shoot-outs after being harassed by police.

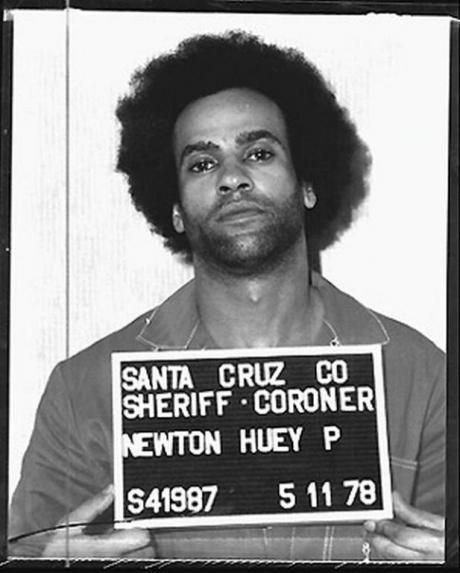

On October 28, 1967, the Panthers and the police exchanged gunfire in Oakland. Huey was injured in the crossfire, and while recovering in the hospital, he was charged with killing an Oakland police officer, John Frey.

He was convicted of voluntary manslaughter the following year.

Huey was regarded as a political prisoner, and the Panthers organized a 'Free Huey' campaign led by Panther Party Minister Eldridge Cleaver. And Charles R. Geary, a well-known attorney who was in charge of Newton’s legal defense.

Newton was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter in 1968 and sentenced to 2-15 years in prison. However, the California Appellate Court ordered a new trial in May 1970. The conviction was reversed on appeal, the case was dismissed by the California Supreme Court, and Huey was acquitted.

Huey renounced political violence after being released from prison. Over a six-year period, 24 Black Panther members were killed in gunfights with the police. Another member, George Jackson, was killed in August 1971 while serving time in San Quentin Prison.

The Black Panther Party, under the leadership of Newton, gained international support. This was most evident in 1970 when Newton was invited to visit China. Large crowds greeted him enthusiastically, holding copies of "Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung," as well as signs supporting the Panther Party and criticizing US imperialism.

In the early 1970s, Newton's leadership of the Black Panther Party contributed to its demise. He oversaw a number of purges of Party members, the most famous of which was in 1971 when he expelled Eldridge Cleaver in what became known as the Newton-Cleaver split over the party's primary function.

Newton wanted the party to be solely focused on serving African-American communities, whereas Cleaver believed the party should be focused on developing relationships with international revolutionary movements. The schism resulted in violence between the factions and the deaths of several Black Panther members. The Black Guerrilla Family (BGF) was one of several factions that had broken away from the main party.

Then, in 1974, Newton was accused of assaulting a 17-year-old prostitute named Kathleen Smith, who later died, raising the charge to murder. Instead of facing trial, Huey fled to Cuba with his girlfriend at the time, where he remained for three years. The key witness in the trial was Crystal Gray. And three Black Panther members attempted to assassinate her before she gave her testimony.

Huey returned to the States in 1976 to stand trial but denied any involvement. The jury was deadlocked, and Newton was eventually acquitted after two mistrials.

In 1978, he enrolled in the History of Consciousness program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and earned his Doctorate in 1980.

"War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America," his dissertation, was later turned into a book.

On charges of embezzling Panther Party funds, Huey P. Newton was sentenced to 6 months in prison followed by 18 months on probation in 1982.

On August 22, 1989, Newton was assassinated by a member of the BGF, named Tyrone Robinson.

Huey was 46 years old at the time of his assassination. Robinson was convicted of Huey’s murder in 1991 and sentenced to 32 years to life in prison.

His wife, Fredricka Newton, carried on his legacy. 'Revolutionary Suicide,' his autobiography, was first published in 1973 and then republished in 1995.

Huey Newton was not perfect, but he did fight to protect the rights of the Black Community. The rights that we're still fighting for today.

__

Previous

Ruby Bridges

Next

Henry "Box" Brown

___

My Sources

#huey p newton#black community#the unofficial black history book#black activism#black history#black female writers#black history matters#black history is american history#black stories#black tumblr#black culture#history#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#black power#black consciousness#black liberation#learn your roots#learn your history#black leaders#writeblr#black writblr#black writers of tumblr#black history 365#know your history#black panther party

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://stateofthenation.co/?p=245803

THE BARBARIANS ARE INSIDE THE GATE ! ! !

Posted on August 16, 2024 by State of the Nation

BOLSHEVIK BOMBSHELL!

Father of Khazarian-Installed Congressional Hitman and Closet Communist Jamie Raskin

Was Founder of the Marxist Institute

for Policy Studies

SOTN Editor’s Note: You know how all the most dangerous flamethrowers in the House of Representatives all hail from a certain tribe (so they say).

Jamin Ben “Jamie” Raskin

Adam Bennett Schiff

Debbie Wasserman Schultz

Jerrold Lewis Nadler

Daniel S. Goldman

Jared Evan Moskowitz

David Nicola Cicilline

Really, why is it that the most dangerous political bolsheviks in the U.S. Congress all act like Khazarian Mafia hitmen?! Legal and legislative hitmen, of course.

KEY POINTS: All any Patriot has to do is watch any hearing in the House where any of those seven political mafiosos are speaking. You talk about an endless spewing of outright lies and equivocation, falsehoods and prevarications, deceits and deceptions, mendacities and misinformation, duplicities and disinformation, etc. All of them are living truth that when virtually any lawyer liar moves their lips, they are lying. The real problem here is what they’re lying about. Honestly, does it get any more perilous than this: THE COMING AMERICAN BOLSHEVIK REVOLUTION?!

Now we see that congressional Mafia don Jamie Raskin was well prepared to complete the communist takeover of the American Republic… … …by his own father, no less!

Was Jamie Raskin’s closet communist

father actually guilty of sedition?

The following graphic depicts what’s really going on in these once United States of America. The problem is, however, that’s it all so friggin complicated you have to be “Dr. John Coleman” to figure it all out and keep it all straight. See: 21 Goals of the Illuminati and The Committee of 300

The crucial point for every NWO researcher and Illuminati investigator is that the Khazarian Cabal reigns supreme above all of the evil-doing secret societies because of the absolute ruthlessness and savagery of their henchman who populate the Khazarian Mafia. There is simply no act of terror or act of war, no staged calamity or engineered cataclysm they will not perpetrate in the furtherance of their nefarious agenda toward a totalitarian One World Government. See: Who is really pulling the strings at the very top of the global power structure?

State of the Nation

August 16, 2024

N.B. The following analysis provides further context proving that: “THE BARBARIANS ARE INSIDE THE GATE ! ! !”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.6.2 What are the social consequences of such a system?

The “anarcho” capitalist imagines that there will be police agencies, “defence associations,” courts, and appeals courts all organised on a free-market basis and available for hire. As David Wieck points out, however, the major problem with such a system would not be the corruption of “private” courts and police forces (although, as suggested above, this could indeed be a problem):

“There is something more serious than the ‘Mafia danger’, and this other problem concerns the role of such ‘defence’ institutions in a given social and economic context.

”[The] context … is one of a free-market economy with no restraints upon accumulation of property. Now, we had an American experience, roughly from the end of the Civil War to the 1930’s, in what were in effect private courts, private police, indeed private governments. We had the experience of the (private) Pinkerton police which, by its spies, by its agents provocateurs, and by methods that included violence and kidnapping, was one of the most powerful tools of large corporations and an instrument of oppression of working people. We had the experience as well of the police forces established to the same end, within corporations, by numerous companies … (The automobile companies drew upon additional covert instruments of a private nature, usually termed vigilante, such as the Black Legion). These were, in effect, private armies, and were sometimes described as such. The territories owned by coal companies, which frequently included entire towns and their environs, the stores the miners were obliged by economic coercion to patronise, the houses they lived in, were commonly policed by the private police of the United States Steel Corporation or whatever company owned the properties. The chief practical function of these police was, of course, to prevent labour organisation and preserve a certain balance of ‘bargaining.’ … These complexes were a law unto themselves, powerful enough to ignore, when they did not purchase, the governments of various jurisdictions of the American federal system. This industrial system was, at the time, often characterised as feudalism.” [Anarchist Justice, pp. 223–224]

For a description of the weaponry and activities of these private armies, the Marxist economic historian Maurice Dobb presents an excellent summary in Studies in Capitalist Development. [pp. 353–357] According to a report on “Private Police Systems” quoted by Dobb, in a town dominated by Republican Steel the “civil liberties and the rights of labour were suppressed by company police. Union organisers were driven out of town.” Company towns had their own (company-run) money, stores, houses and jails and many corporations had machine-guns and tear-gas along with the usual shot-guns, rifles and revolvers. The “usurpation of police powers by privately paid ‘guards and ‘deputies’, often hired from detective agencies, many with criminal records” was “a general practice in many parts of the country.”

The local (state-run) law enforcement agencies turned a blind-eye to what was going on (after all, the workers had broken their contracts and so were “criminal aggressors” against the companies) even when union members and strikers were beaten and killed. The workers own defence organisations (unions) were the only ones willing to help them, and if the workers seemed to be winning then troops were called in to “restore the peace” (as happened in the Ludlow strike, when strikers originally cheered the troops as they thought they would defend them; needless to say, they were wrong).

Here we have a society which is claimed by many “anarcho”-capitalists as one of the closest examples to their “ideal,” with limited state intervention, free reign for property owners, etc. What happened? The rich reduced the working class to a serf-like existence, capitalist production undermined independent producers (much to the annoyance of individualist anarchists at the time), and the result was the emergence of the corporate America that “anarcho”-capitalists (sometimes) say they oppose.

Are we to expect that “anarcho”-capitalism will be different? That, unlike before, “defence” firms will intervene on behalf of strikers? Given that the “general libertarian law code” will be enforcing capitalist property rights, workers will be in exactly the same situation as they were then. Support of strikers violating property rights would be a violation of the law and be costly for profit making firms to do (if not dangerous as they could be “outlawed” by the rest). This suggests that “anarcho”-capitalism will extend extensive rights and powers to bosses, but few if any rights to rebellious workers. And this difference in power is enshrined within the fundamental institutions of the system. This can easily be seen from Rothbard’s numerous anti-union tirades and his obvious hatred of them, strikes and pickets (which he habitually labelled as violent). As such it is not surprising to discover that Rothbard complained in the 1960s that, because of the Wagner Act, the American police “commonly remain ‘neutral’ when strike-breakers are molested or else blame the strike-breakers for ‘provoking’ the attacks on them … When unions are permitted to resort to violence, the state or other enforcing agency has implicitly delegated this power to the unions. The unions, then, have become ‘private states.’” [The Logic of Action II, p. 41] The role of the police was to back the property owner against their rebel workers, in other words, and the state was failing to provide the appropriate service (of course, that bosses exercising power over workers provoked the strike is irrelevant, while private police attacking picket lines is purely a form of “defensive” violence and is, likewise, of no concern).

In evaluating “anarcho”-capitalism’s claim to be a form of anarchism, Peter Marshall notes that “private protection agencies would merely serve the interests of their paymasters.” [Demanding the Impossible, p. 653] With the increase of private “defence associations” under “really existing capitalism” today (associations that many “anarcho”-capitalists point to as examples of their ideas), we see a vindication of Marshall’s claim. There have been many documented experiences of protesters being badly beaten by private security guards. As far as market theory goes, the companies are only supplying what the buyer is demanding. The rights of others are not a factor (yet more “externalities,” obviously). Even if the victims successfully sue the company, the message is clear — social activism can seriously damage your health. With a reversion to “a general libertarian law code” enforced by private companies, this form of “defence” of “absolute” property rights can only increase, perhaps to the levels previously attained in the heyday of US capitalism, as described above by Wieck.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Published: Apr 26, 2024

The hysteria in the Ivy League does not start there. Those students shrieking Hamas slogans in the squares of New York were not radicalized overnight. It is in schools that civilization is built or destroyed. Schooling determines the calibre of a nation’s governing class, if not its ideology. This is well understood by the Left, which has transformed Western pedagogy since the 1968 publication of the third most-cited work of social science of all time, Pedagogy of the Oppressed by the Brazilian Marxist Paolo Freire. Freire’s book took the USA by storm in the 1970s, helping to decimate such tyrannical norms as the authority of the teacher over the pupil, the memorization of knowledge, and even the idea that knowledge is good for its own sake (he claimed that the sole value in teaching is to reveal the “oppressive nature of reality” to children). So, while the unholy trinity of Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity (D.I.E.) has enjoyed a growth spurt in the last decade, we can trace its roots back to good old-fashioned 20th century Marxism. Soviet-funded subversive ideology surviving its mother’s demise, yet again.

D.I.E. is, in turn, the mother of poor standards: dumbing down logically proceeds from the ideology of “emancipatory education,” which attacks “logocentric” (or, more recently, “Eurocentric”) knowledge for being the fruit of Dead White Male labor. This explains the lack of classroom rigor and teaching authority that underpins the appalling standards in American public schools. US literacy and numeracy scores have now dropped to their lowest level in decades. (Though there is some evidence suggesting this has partly to do with demographic changes.) This decline preceded 2020 but was undoubtedly worsened by the closure of schools during the pandemic.

But poor test scores are only part of the problem: the ideological equivalent of paranoid schizophrenia, poorly concealed by woke buzzwords like “inclusion,” now has a stranglehold on the schools. Children are being fed ideas which are not just nakedly ideological, but bewildering: there are as many genders as there are numbers and racial color-blindness is oppressive. This allegedly pastoral education eats into the time that children might otherwise spend learning a language.

Top institutions are not invulnerable to the ideological madness and philistinism of D.I.E. In some cases, they lead the charge: flagship independent schools like Eton and its American parallel, Philipps Exeter (attended by now-disgraced Harvard President Claudine Gay), have officially DIEd a demeaning death.

At Eton, English master Will Knowland was fired in 2020 for refusing to retract his statements in a lecture entitled “The Patriarchy Paradox,” in which he challenged the idea that masculinity is by nature toxic. In defending masculinity, Knowland sought to emancipate a classroom full of boys from the idea that their sex is irrevocably stained with the sin of “patriarchy.” Knowland’s goal – and crime – was to encourage boys to have confidence. This was too much for the school: Knowland was fired at the hands of Head Master Simon Henderson, who, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, pledged to teach a school of English boys the fanatical dogma of the American left: that society is plagued with “systemic racism” and (in a nation which abolished slavery throughout much of Africa) must be “decolonized.”

The events in May 2020 likewise prompted a period of insanity at Phillips Exeter. “Intersectional” studies of science and race abound, as do “queer readings” of Shakespeare; most alarmingly, children are subject to cynical “anti-racist training,” based on the idea that white children are inherently racist – an idea which is sure to shatter the self-confidence of those children.

It may sound elitist to mourn top institutions like Eton and Exeter rather than focussing on the abject conditions of state-funded schools in the Anglosphere. To that I say: yes! The health of the body politic depends on the health and caliber of its political elite. It is in any nation’s best interest to be governed by men and women who know right from wrong, are well-versed in the languages and literatures of their global allies, and conduct themselves with responsibility rather than racially motivated neurosis or self-victimization. At the very least, can’t politicians possess the basic knowledge required to do their jobs? It seems not: last month, it was revealed that the chief secretary to the Treasury in the UK, educated at top grammar school Oxted and Pembroke College, Oxford, doesn’t know how to interpret statistical data.

But education isn’t just instrumental. Knowledge may be power, but it is also true “emancipation.” The perversion of D.I.E is that it removes the real freedom which excellence and emotional robustness gives children, shackling them with poor-quality learning and a host of neuroses. This particularly betrays children from unstable backgrounds, whom D.I.E. claims to help. The distress which anti-colorblind dogma brings children is palpable: parents have reported that their children leave classrooms in tears because they are white, therefore monstrous oppressors. Chaya Raichik, known for her Twitter account “LibsofTikTok,” has drawn attention to dozens of cases of overt anti-white propaganda in American schools, many of which are elementary schools; typical occurrences include schools hosting playdates which exclude white children. Despite her primary tactic being to simply repost content which teachers and schools willingly publish themselves, Raichik has come under fire for “inciting hatred” (as a glance over her outrageously partisan Wikipedia page reveals). Since her platform has such a wide reach, her critics claim she is irresponsibly drawing attention to humble elementary school teachers; it doesn’t occur to them that these teachers should probably restrain themselves from posting about their ideological schemes on TikTok, the most popular mobile app in the USA.

Perhaps even more pressing is the explosion of transgenderism in schools. As a recently censored study shows, “rapid onset gender dysphoria” is a real and growing phenomenon. The contagious nature of trans identities contradicts the claim that these identities are innate; evidence of exploding numbers of insecure, pubescent children identifying as transgender in social clusters shows otherwise.

The social contagion effect in schools is compounded by ideologically driven teachers who work to alienate parents from their children by concealing and abetting their young pupils’ new identities. In April 2022, Chaya Raichik exposed footage of an 8th grade English teacher in Owasso, Oklahoma, who stated in a video "If your parents don't accept you for who you are, f*ck them. I'm your parents now. I'm proud of you. Drink some water. I love you." Tyler Wrynn, the teacher in question, is far from alone in his stated mission to “emancipate” children from parents who are concerned that their children might seek out and access cross-sex hormonal therapy, which risks sterilization and myriad permanent ailments. In this way, D.I.E. in schools poses a threat to fundamental unit of society which overwhelmingly determines outcomes for children: the nuclear family.

[ Katherine Birbalsingh. ]

Parents are waking up. Demand is growing for classical schools where great books will be devoured rather than dismissed as relics of a world of Dead White Men. Schools which champion the principles of authority, stability, order, and emotional fortitude are already boasting unusual academic success and good discipline: Michaela Community School in London, run by the effervescent Katherine Birbalsingh, is a testament to how strict authority can transform the prospects of children who come from deprived, largely nonwhite backgrounds. Birbalsingh discourages the victimhood mentality which is typical of Generation Z, eschewing appeals to “mitigated circumstances” if homework is late.

Often described by the British press as the “strictest school in Britain,” Michaela attained among the best GCSE results (the rough British equivalent of the Iowa tests) in the country in its very first student cohort. In 2022 and 2023 the school boasted the highest “value-added” (or progress) score in the country, all while autocratically banning mobile phones and making it compulsory to sing the National Anthem. In Alberta, Canada, Caylan Ford (who has written incisively about the pernicious philosophy underpinning Freire’s Pedagogy) has been overwhelmed by the demand for her newly-founded classical charter school, Calgary Classical Academy. The Great Hearts School network, exploding across the American southwest, is another heartwarming example.

Stuffy, strict, concerned parents: take stock. You are not alone.

#Ayaan Hirsi Ali#diversity equity and inclusion#diversity#equity#inclusion#DEI bureaucracy#DEI must die#low standards#elite schools#ideological corruption#corruption of education#academic corruption#religion is a mental illness

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

liberals have also fallen for it but the conservative hysteria re: the chinese weather balloon I hope comes as a useful lesson for the post-liberal marxists that haven’t fallen for the lib culture war bullshit. the thing with ideologues is that they’re often capable of some really reasonable, clever social analysis when they remain within the confines of their ideology. an American republican has the ability to criticize gender ideology, the russiagate hoax, elite pedophilia, and the ukraine proxy war with a lot fewer restraints than the average liberal. I’ve seen a lot of very intelligent arguments come out of the right on certain subjects, which is why i make a point to take every argument based on its merits rather than the ideology of the person espousing it. an emerging strain of marxists are also getting better at recognizing this, following the money behind many progressive liberal causes, and coming to their own conclusions that sometimes more closely align with the right than the authoritarian, so-called “progressive” left. but the difference between the republicans and democrats comes down to who’s currently in power more than anything— who controls the media and other influential institutions. the republicans are leveraging their underdog status to recruit working class people who are disillusioned by war and the erosion of their quality of life, which they blame solely on democratic policy. they can criticize the democratic party lines that contribute to war, coercion, and impoverishment. but their hawkish china policy reveals their hand. the “red-pilled” normie republicans falling in line behind it reveal the intellectual limits of being an ideologue. if you study the political climate during the iraq war you’ll understand that better, too. if you’re so ideologically driven that you can turn your brain off when the elite frame their pro-war messaging in a way that appeals to your sensibilities (radblr and iran too, lol) you expose your weak spots to them. they only intensify their assault on your mind from there. dogmatism is a valuable tool in psychological warfare, don’t give it to them

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

The reasons for the outsized influence on the academic humanities of the French poststructuralists (as opposed to the more moderate critics of scientism such as Midgley) is no doubt overdetermined, but which explanations do you find most convincing?

I can only speak for the English department, but the most convincing answer is the most benign one, the one that least involves "Cultural Marxist" subversion of the west or CIA anti-communist skullduggery, the one immanent to the institution of academic criticism itself: the humanists had no theory of their practice, no global meta-discourse to guide individual instances of their discourse. This left them at a disadvantage in explaining themselves to their students and to the public in the face of scientific hegemony. They needed a system.

Academic criticism felt too amateurish, too gentlemanly, even after certain modernist assumptions had been assimilated by the middle of the century. New Criticism had rigor but you ran against its limitations very quickly, not even so much because of its ahistorical and Christian presuppositions, but because it only really works at all on certain types of texts, i.e., lyric poems of a riddling disposition, as well as the few larger forms that can look like such poems if you squint (early modern drama, for example, or modernist fiction). Psychoanalysis and Marxism in their pre-theory forms were too reductive, not even textual hermeneutics really, and therefore left the critic too little to say (Hamlet wants to sleep with his mother, Dickens is petit bourgeois: so what?); this goes, too, for the pre-theoretical attempts at identity politics, like early feminist criticism of the "images of women in literature" type. Myth criticism had a certain visionary appeal, but too often decayed into a predictable game of spot-the-archetype (another Christ figure in a modern novel? tell me a new one).[*]

On the other hand, the structuralist and poststructuralist ideas coming out of France promised a theory of language that was also a theory of society—even a theory that language was society and vice versa—and a therefore promised a systematic science of the literary text qua text as well as an Archimedean lever with which to shift the political (and indeed the scientific) in language. "Il n’y a pas de hors-texte." It opened up the whole world of European philosophy to Anglophone literary criticism and glamorously updated everything they were already doing with a self-conscious methodological sophistication. Close reading for balanced ambiguities became textual analysis aimed at subversive aporias.

This turn to englobalizing method would in the long run dissolve any plausible mission for literary studies per se as opposed to an "everything studies" that doubles as a "nothing studies," even as it ironically became the new cultural lingua franca of the whole educated class, supplanting the literary itself. I went to see the horror film It Lives Inside the other day. In the genre-obligatory high-school classroom scene, our heroine, her loyalties painfully divided between white American assimilation and her immigrant family's Hindu culture, tells her teacher that John Winthrop's city-on-a-hill sermon is, and I quote, "a normative fantasy." (The film then labors, with mixed success, to supply a rival normative fantasy.) 40 years ago, in A Nightmare on Elm Street, the teens in their English class just recited a scary speech from Shakespeare.

_______________________

[*] When I used to teach this class, I would look at various handbooks for undergraduates, and it was always interesting to see how they'd characterize the pre-theory era. Terry Eagleton in Literary Theory and Peter Barry in Beginning Theory tendentiously called it "liberal humanist," with their skeptical eye on the Arnoldian idea that literature could unify and redeem an otherwise class-ridden society; but Nicholas Birns in Theory After Theory more persuasively said it was the era of the "resolved symbolic," when critics had faith they could provide a final interpretive answer to the riddle of the isolated text, as opposed to theory's later claims that everything is a text and that texts by their nature are permanently open-ended.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Hanson

In a 1949 paper published in the Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors, the liberal philosopher Sidney Hook described a certain species of mid-century intellectual who, having long looked to the Soviet Union as a grand experiment in human emancipation, was impelled, for one reason or another, to doubt and ultimately abandon that conviction. The flight of the fellow travelers, including the likes of W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, André Gide, and Bertrand Russell, was born not out of mere disappointment or embarrassment but, Hook insisted, something deeper and far more troubling: a kind of religious disenchantment that upset the foundations of a shared political identity. What resulted from this “decay of faith,” as Hook termed it, was a “literature of political disillusionment,” a subgenre in the confessional style in which that failure was put on full display, examined, and ultimately transformed into maturity. The primary language in which this maturity expressed itself was liberalism.

More often than not, when we hear about political disillusionment in the polling and punditry of our moment, it is disillusionment with liberalism itself. Against all and sundry foes, from autocratic putsches at home and abroad to leftward agitation on the labor and electoral fronts, self-described centrists, realists, and liberals find themselves on their guard, in the uncomfortable position of having to defend an apparently crumbling status quo.

Though Hook, who also began his career as a Marxist, focused primarily on the implosion of the Soviet star in the eyes of left-leaning Western intellectuals, this trajectory from left to center (and beyond) as a process of realization is an important device in ideological self-narration. From Immanuel Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “man’s emancipation from self-imposed immaturity” in the forms of political and religious authoritarianism to Irving Kristol’s description of a neoconservative as a liberal (though here he meant anyone left of the American center) who has been “mugged by reality,” the ideal of much of mainstream political thought has been the gradual escape from imposed demands and Icarian fantasies into a utopia of grown-ups, making decisions not on the basis of received opinion, or even of principles, but in accordance with the transparently “rational.”

What carries us on the way to this besotted realm? For many Enlightenment and 19th-century liberal thinkers, it was Christianity—especially in its Protestant, bourgeois forms—that provided a kind of ladder to political maturity that could, eventually, be kicked away. But with the slow erosion of that faith, as well as a general skepticism about the inevitability of progress, could a literature of political disillusionment serve that role? And what do we make of this alternative, which brings us to maturity not by hope but by disappointment? Is there, in the end, a choice between the two?

In the course of his decades-long career, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has added much to this literature. His early novels, such as 1966’s The Green House and 1969’s Conversations in the Cathedral, explored the sources of decay that lead to both institutional corruption and personal despair. And in his essays, articles, and speeches, Vargas Llosa has long been among the most prominent literary defenders of the Western liberal order. Now the octogenarian Nobel laureate and newly elected member of the Academie Française (the first non-Francophone member in its history) offers a summation and justification of that effort in The Call of the Tribe, a study of seven key thinkers who helped him shed his youthful socialist idealism and oriented his soul toward the light of republican democracy and market capitalism. That list of luminaries includes the Scottish economist and “father of liberalism” Adam Smith; the Spanish existentialist José Ortega y Gasset; the Austrian American economist Friedrich Hayek; the Austrian British philosopher of science Karl Popper; the French philosopher Raymond Aron; the Russian British political theorist Isaiah Berlin; and the French public intellectual Jean-François Revel.

In the book’s introduction, Vargas Llosa offers general reflections on his own political experience and his disenchantment with leftism, as well as more pointed comments on the role of the state as a protector of individual liberty and administrator of education, both public and private. (Education, for Vargas Llosa, is an important data point in the reliability of competition as an engine for quality and progress; he’s particularly fond of voucher systems. He attributes these ideas to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, one of the godfathers of neoliberalism.)

The story that Vargas Llosa tells of his political formation is that of a young man, born into a middle-class but well-connected family, and who spent time in Cuba in the 1960s, only to find himself increasingly alienated by what he took to be Castro’s autocratic tendencies. The breaking point was what is now known as the Padilla Affair, in which the poet and public intellectual Herberto Padilla—an initial supporter of Castro’s government, who became its increasingly strident critic—was arrested in 1971 on the grounds of making counterrevolutionary statements, as well as accusations that he was acting in the employ the CIA (an “absurd accusation,” according to Vargas Llosa).

Padilla’s link to American intelligence remains in dispute (a letter to The Guardian in response to the paper’s glowing obituary of him in 2000 suggests conflicting evidence), but, as far as I can tell, that was neither the charge that got him arrested nor what caused Vargas Llosa, along with other public intellectuals in the West, to break with Cuba. A self-evidently coerced public confession by Padilla followed his arrest, which was far too reminiscent of the Stalinist show trials that an earlier generation of intellectuals had condemned, and this led Vargas Llosa—alongside Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others—to publish an open letter denouncing Castro’s apparent authoritarian turn. Padilla himself lived in a tense détente with the regime for another decade before moving to the United States and teaching at Princeton, but for Vargas Llosa, not only the Cuban project but leftist politics as a whole were now irredeemably tainted.

It is in this context that Vargas Llosa’s principle of selection in The Call of the Tribe becomes clearer: The thinkers he examines are exclusively European and male, an indication not so much of Eurocentrism and sexism (at least not immediately) as of the kind of thinking that he finds most compelling. When drawing up a list of thinkers who took liberalism seriously as perhaps the only remaining political possibility in the 20th century, excluding the likes of Hannah Arendt and Judith Shklar would be a damnable oversight. But strict theorizing is not exactly the terrain Vargas Llosa wants to cover here. Instead, as his career has shown (in addition to his literary and journalistic work, Vargas Llosa has also been a highly visible political figure, even running in Peru’s 1990 presidential election at the head of the center-right Frente Démocratico), he is most alive at the boundary of thought and action. He is therefore drawn to the thinkers who, either by intervention or influence, crossed that line and became unofficial spokesmen for world events. And though Vargas Llosa is at pains to portray liberalism as a “big tent” (his phrase), certain themes emerge to offer a rough-and-ready outline of what, for him, constitutes liberal thinking.

Liberalism’s key virtue, Vargas Llosa insists, is the primacy it grants to the individual over the collective. The title of the volume, The Call of the Tribe, comes from Popper, who is perhaps most famous for The Open Society and Its Enemies, his critical-historical account of the intellectual origins of authoritarianism. This study, which attacks Plato, Hegel, and Marx for their “historicism” (Popper’s curiously misapplied term for social theory aimed at the prediction of future events), is still taken seriously by many liberals, despite a broad consensus that Popper’s thesis is based on a profound misreading of both political and intellectual history. Vargas Llosa cites him, along with Hayek and Berlin, as having had the greatest influence on his own political development, particularly in coming to understand the role of liberal society as the protector of the individual against the ever-present dangers of primitivism and irrationality, the anti-civilizational “call of the tribe.”

For Vargas Llosa, as for all of the thinkers he explores, the history of the 20th century is the fight of the liberal West against various manifestations of that call, which, in modern societies, takes the form of the mass or crowd. Citing Ortega’s Revolt of the Masses, in which the emergence of the crowd in modern times is analyzed and warned against, Vargas Llosa writes: “The ‘mass’…is a group of individuals who have become deindividualized, who have stopped being freethinking human entities and have dissolved into an amalgam that thinks and acts for them, more through conditioned reflexes—emotions, instincts, passions—than through reason.” Crucially here, the liberal ideal is not a goal to be achieved but a neutral state to be protected. It is, in this telling, the natural form of human life, as opposed to the imposed structures of any other kind of social organization. Such naturalism is not merely a tendency but a main tenet of Vargas Llosa’s liberalism, and it accounts not only for the vehemence with which he attacks the thought that he believes threatens it (above all, the leftist positions he claims once to have held), but also for the means by which he defends what is now the mainstream—not to say hegemonic—social order.

Beginning with Adam Smith—who, we are told, “emphasizes that state interventionism is an infallible recipe for economic failure because it stifles free competition”—Vargas Llosa insists on the link between unencumbered economic activity and human freedom generally, a conviction that determines his assessment of each of his key thinkers. In all, Hayek seems to win out as the greatest among them: “Nobody,” Vargas Llosa writes, “has explained better than Hayek the benefits to society, in all areas, of this system of exchanges that nobody invented, that was born and perfected by chance, above all by that historical accident called liberty.” If fascism (or related forms of despotism), in Vargas Llosa’s estimation, is a threat on the grounds of its irrationality, then leftism, from democratic socialism to Soviet communism, remains a greater threat still for its overestimation of human reason. Given liberalism’s defeat of its rival systems (this, of course, is the historical account we’re working with here, despite the crucial Soviet role in destroying the Third Reich and the subsequent absorption of former Nazis into the liberal West, from Kurt Waldheim to Klaus Barbie), the enemy to be resisted is the specter of planning.

The rejection of planning, which Vargas Llosa attributes to both Hayek and Popper, is a difficult idea to hold philosophically in your mind. After all, human affairs do not simply unfold. People respond to stimuli and instruction, however implicit, and it is governments and social institutions, among other things, that form the conditions of the lessons we learn. The critique of planning, then, seems not to be the choice of freedom over determination, but rather the preference for certain kinds of decisions over others.

But I think this is not a question of argumentative slippage, much less of hypocrisy on Vargas Llosa’s part. In keeping with his selection of thinkers, his interest is not in dissecting the arguments for liberalism but simply in defending them, by whatever means prove efficacious. The Call of the Tribe is as much a manifesto and a homage as it is a study.

Vargas Llosa’s rejection of the left, then, is largely based on the bad actions committed by some leftists, which he takes to be indicative of the rot at the heart of the entire enterprise. When he learns of Castro’s detention centers, he sees them as evidence of the regime’s fundamental nature. By contrast, the regimes of both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are praised for introducing a new dynamism into British and American life—and as for their funding of death squads from Ulster to El Salvador, the flourishing of private prisons, or the more or less constant state of crisis we have lived under since this neoliberal revolution, these are, to the extent that Vargas Llosa addresses them at all, so many broken eggs in the world-historical omelet. In less triumphant moments, the book’s message seems to be that when a liberal government commits crimes and human rights abuses, it is simply failing to understand or live up to its own ideals.

But the contents of liberalism itself are subject to similarly shifting sands, even contrary tendencies. When Ortega fails to acknowledge the superiority of free-market capitalism to central planning, Vargas Llosa deems his liberalism “partial,” whereas Hayek’s liberalism consists precisely in his transcending the merely economic. And when Hayek praises the murderous, repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, this is simply an example of one of his “convictions [that] are difficult for an authentic democrat to share.” No more discussion is given to the matter. Perhaps Vargas Llosa is remembering who the real enemy is: When Pinochet was arrested for crimes against humanity in 1999, Vargas Llosa penned an op-ed for The New York Times asking why, if the world was willing to condemn the right-wing dictator, it was not also willing to condemn the left-wing dictators of the world, chief among them Castro.

Vargas Llosa retains much of his power as a prose stylist, and there are moments when The Call of the Tribe provokes a genuine thrill of discovery—a sense that, for good or ill, it was these men whose ideas have driven the history of the last half-century. Nevertheless, there are just as many moments when these accounts of intellectual adventure and individual liberty begin to sag, when the insistence that no system or ideal other than free-market capitalism and liberal democracy can ensure the conditions for individual and social flourishing becomes almost a mantra, an utterance unanswerable not because it is flawless, but because it doesn’t seem made with dialogue in mind.

What does such a hagiographic approach offer to anyone who is not already a believer? This question returns us to what we can learn from the literature of disillusionment. Why, when liberalism is merely the natural and rational position to hold, does it require such a defense? Vargas Llosa allows us a glimpse behind the curtain in his discussion of the argumentative style of the outwardly modest Isaiah Berlin: “Fair play,” he writes, “is only a technique that, like all narrative techniques, has just one function: to make the content more persuasive. A story that seems not to be told by anyone in particular, that purports to be creating itself, by itself, at the moment of reading, can often be more plausible and engrossing for the reader.”

So why disillusionment? It’s a narrative mode with obvious religious connotations; it is a story about the revelation of the true religion, the smashing of false idols and the embrace of pure faith, at which point “religion,” as such, becomes the enemy, or at least a danger to be wary of. This same structure played out in colonial encounters—colonists described natives first as having no religion and then, once European Christianity gave way to secular humanism, as being slaves to it. So it is perfectly consistent to point to Marxism or leftist politics generally, as Vargas Llosa does (drawing especially on Popper and Raymond Aron), as primitive, tribal, religious. “Religion,” in this tradition, is what other people do.

It is this historical double play that illuminates the real power of the narrative of disillusionment. It aids in the creation not of two sides of an argument, but of a natural (that is, a non- or even subhuman) phenomenon and a neutral observer. Such an observer may have a commitment to “flexibility,” as Varga Llosa insists that all liberals—whether individual thinkers or governments—must, but such a duality nevertheless depends on a carefully guarded wall between the wildness out there and the reason in here. It is the complexity of a world of actions and relations, decisions and consequences, congealed into a world of determined possibilities that will remain hidden unless you simply, though perhaps painfully, grow up. When the demand is made so insistently, one begins to wonder what measures might be justified in dragging the reluctant into the light.

I have to admit that by the end of The Call of the Tribe, I felt a kind of malaise, having read the litany of liberal virtue in so many iterations. Why, the question nagged, in its fourth (or, arguably, eighth) decade of nearly unchallenged global hegemony, do the representatives of Western liberalism feel the need to defend it against threats that have been for so long neutralized? And then it occurred to me that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup d’état, the death of Salvador Allende, and the beginning of a decades-long tyranny supported and praised by, among others, Hayek, Friedman, and the US government. Allende, as it happens, is one democratically elected socialist for whom Vargas Llosa, if this book is any indication, retains some sympathy, if only in retrospect. Perhaps, he seems to suggest, the transition to a more fully liberal economy could have been accomplished more smoothly, less forcefully. Still, the Chicago Boys took over, the left was destroyed, and it is in the nature of stories to be retold, of rituals to be performed, of victories to be commemorated.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dr. Robin Davis Gibran Kelley (born March 14, 1962, in New York City) is a historian and academic, who is the Gary B. Nash Professor of American History at UCLA.

He was a Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at USC and he was the William B. Ransford Professor of Cultural and Historical Studies at Columbia University. He was a professor of history and Africana Studies at NYU and the chair of NYU’s history department. He has served as a Hess Scholar-in-Residence at Brooklyn College. He was honored as a Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College, as well as wrote the majority of the book Freedom Dreams.

He served as Harold Vyvyan Harmsworth Professor of American History at Oxford University, the first African-American historian to do so. He was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 2014. He is the author of a biography of Thelonious Monk.

He earned his BA from California State University, Long Beach, and earned an MA in African History and a Ph.D. in US History from UCLA.

He began his career as an Assistant Professor at Southeastern Massachusetts University, Emory University, and the University of Michigan, where he was promoted to Associate Professor with tenure. He moved to the Department of History at New York University, where he was promoted to the rank of professor and taught courses on US history, African-American history, and popular culture. At the age of 32, he was the youngest full professor at NYU. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford.

He has spent most of his career exploring American and African-American history, with a particular emphasis on radical social movements and the political dynamics at work within African-American culture, including jazz, hip-hop, and visual arts.

He has eschewed a doctrinaire Marxist approach to aesthetics and culture, preferring a modified surrealist approach. He has described himself in the past as a “Marxist surrealist feminist who is not just anti-something but pro-emancipation, pro-liberation.”

He has used the concept of racial capitalism in his work. He is married to actress LisaGay Hamilton. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #alphaphialpha

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jack Hanson

In a 1949 paper published in the Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors, the liberal philosopher Sidney Hook described a certain species of mid-century intellectual who, having long looked to the Soviet Union as a grand experiment in human emancipation, was impelled, for one reason or another, to doubt and ultimately abandon that conviction. The flight of the fellow travelers, including the likes of W.H. Auden, Edmund Wilson, André Gide, and Bertrand Russell, was born not out of mere disappointment or embarrassment but, Hook insisted, something deeper and far more troubling: a kind of religious disenchantment that upset the foundations of a shared political identity. What resulted from this “decay of faith,” as Hook termed it, was a “literature of political disillusionment,” a subgenre in the confessional style in which that failure was put on full display, examined, and ultimately transformed into maturity. The primary language in which this maturity expressed itself was liberalism.

More often than not, when we hear about political disillusionment in the polling and punditry of our moment, it is disillusionment with liberalism itself. Against all and sundry foes, from autocratic putsches at home and abroad to leftward agitation on the labor and electoral fronts, self-described centrists, realists, and liberals find themselves on their guard, in the uncomfortable position of having to defend an apparently crumbling status quo.

Though Hook, who also began his career as a Marxist, focused primarily on the implosion of the Soviet star in the eyes of left-leaning Western intellectuals, this trajectory from left to center (and beyond) as a process of realization is an important device in ideological self-narration. From Immanuel Kant’s definition of enlightenment as “man’s emancipation from self-imposed immaturity” in the forms of political and religious authoritarianism to Irving Kristol’s description of a neoconservative as a liberal (though here he meant anyone left of the American center) who has been “mugged by reality,” the ideal of much of mainstream political thought has been the gradual escape from imposed demands and Icarian fantasies into a utopia of grown-ups, making decisions not on the basis of received opinion, or even of principles, but in accordance with the transparently “rational.”

What carries us on the way to this besotted realm? For many Enlightenment and 19th-century liberal thinkers, it was Christianity—especially in its Protestant, bourgeois forms—that provided a kind of ladder to political maturity that could, eventually, be kicked away. But with the slow erosion of that faith, as well as a general skepticism about the inevitability of progress, could a literature of political disillusionment serve that role? And what do we make of this alternative, which brings us to maturity not by hope but by disappointment? Is there, in the end, a choice between the two?

In the course of his decades-long career, the Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has added much to this literature. His early novels, such as 1966’s The Green House and 1969’s Conversations in the Cathedral, explored the sources of decay that lead to both institutional corruption and personal despair. And in his essays, articles, and speeches, Vargas Llosa has long been among the most prominent literary defenders of the Western liberal order. Now the octogenarian Nobel laureate and newly elected member of the Academie Française (the first non-Francophone member in its history) offers a summation and justification of that effort in The Call of the Tribe, a study of seven key thinkers who helped him shed his youthful socialist idealism and oriented his soul toward the light of republican democracy and market capitalism. That list of luminaries includes the Scottish economist and “father of liberalism” Adam Smith; the Spanish existentialist José Ortega y Gasset; the Austrian American economist Friedrich Hayek; the Austrian British philosopher of science Karl Popper; the French philosopher Raymond Aron; the Russian British political theorist Isaiah Berlin; and the French public intellectual Jean-François Revel.

In the book’s introduction, Vargas Llosa offers general reflections on his own political experience and his disenchantment with leftism, as well as more pointed comments on the role of the state as a protector of individual liberty and administrator of education, both public and private. (Education, for Vargas Llosa, is an important data point in the reliability of competition as an engine for quality and progress; he’s particularly fond of voucher systems. He attributes these ideas to the Chicago economist Milton Friedman, one of the godfathers of neoliberalism.)

The story that Vargas Llosa tells of his political formation is that of a young man, born into a middle-class but well-connected family, and who spent time in Cuba in the 1960s, only to find himself increasingly alienated by what he took to be Castro’s autocratic tendencies. The breaking point was what is now known as the Padilla Affair, in which the poet and public intellectual Herberto Padilla—an initial supporter of Castro’s government, who became its increasingly strident critic—was arrested in 1971 on the grounds of making counterrevolutionary statements, as well as accusations that he was acting in the employ the CIA (an “absurd accusation,” according to Vargas Llosa).

Padilla’s link to American intelligence remains in dispute (a letter to The Guardian in response to the paper’s glowing obituary of him in 2000 suggests conflicting evidence), but, as far as I can tell, that was neither the charge that got him arrested nor what caused Vargas Llosa, along with other public intellectuals in the West, to break with Cuba. A self-evidently coerced public confession by Padilla followed his arrest, which was far too reminiscent of the Stalinist show trials that an earlier generation of intellectuals had condemned, and this led Vargas Llosa—alongside Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others—to publish an open letter denouncing Castro’s apparent authoritarian turn. Padilla himself lived in a tense détente with the regime for another decade before moving to the United States and teaching at Princeton, but for Vargas Llosa, not only the Cuban project but leftist politics as a whole were now irredeemably tainted.

It is in this context that Vargas Llosa’s principle of selection in The Call of the Tribe becomes clearer: The thinkers he examines are exclusively European and male, an indication not so much of Eurocentrism and sexism (at least not immediately) as of the kind of thinking that he finds most compelling. When drawing up a list of thinkers who took liberalism seriously as perhaps the only remaining political possibility in the 20th century, excluding the likes of Hannah Arendt and Judith Shklar would be a damnable oversight. But strict theorizing is not exactly the terrain Vargas Llosa wants to cover here. Instead, as his career has shown (in addition to his literary and journalistic work, Vargas Llosa has also been a highly visible political figure, even running in Peru’s 1990 presidential election at the head of the center-right Frente Démocratico), he is most alive at the boundary of thought and action. He is therefore drawn to the thinkers who, either by intervention or influence, crossed that line and became unofficial spokesmen for world events. And though Vargas Llosa is at pains to portray liberalism as a “big tent” (his phrase), certain themes emerge to offer a rough-and-ready outline of what, for him, constitutes liberal thinking.

Liberalism’s key virtue, Vargas Llosa insists, is the primacy it grants to the individual over the collective. The title of the volume, The Call of the Tribe, comes from Popper, who is perhaps most famous for The Open Society and Its Enemies, his critical-historical account of the intellectual origins of authoritarianism. This study, which attacks Plato, Hegel, and Marx for their “historicism” (Popper’s curiously misapplied term for social theory aimed at the prediction of future events), is still taken seriously by many liberals, despite a broad consensus that Popper’s thesis is based on a profound misreading of both political and intellectual history. Vargas Llosa cites him, along with Hayek and Berlin, as having had the greatest influence on his own political development, particularly in coming to understand the role of liberal society as the protector of the individual against the ever-present dangers of primitivism and irrationality, the anti-civilizational “call of the tribe.”

For Vargas Llosa, as for all of the thinkers he explores, the history of the 20th century is the fight of the liberal West against various manifestations of that call, which, in modern societies, takes the form of the mass or crowd. Citing Ortega’s Revolt of the Masses, in which the emergence of the crowd in modern times is analyzed and warned against, Vargas Llosa writes: “The ‘mass’…is a group of individuals who have become deindividualized, who have stopped being freethinking human entities and have dissolved into an amalgam that thinks and acts for them, more through conditioned reflexes—emotions, instincts, passions—than through reason.” Crucially here, the liberal ideal is not a goal to be achieved but a neutral state to be protected. It is, in this telling, the natural form of human life, as opposed to the imposed structures of any other kind of social organization. Such naturalism is not merely a tendency but a main tenet of Vargas Llosa’s liberalism, and it accounts not only for the vehemence with which he attacks the thought that he believes threatens it (above all, the leftist positions he claims once to have held), but also for the means by which he defends what is now the mainstream—not to say hegemonic—social order.

Beginning with Adam Smith—who, we are told, “emphasizes that state interventionism is an infallible recipe for economic failure because it stifles free competition”—Vargas Llosa insists on the link between unencumbered economic activity and human freedom generally, a conviction that determines his assessment of each of his key thinkers. In all, Hayek seems to win out as the greatest among them: “Nobody,” Vargas Llosa writes, “has explained better than Hayek the benefits to society, in all areas, of this system of exchanges that nobody invented, that was born and perfected by chance, above all by that historical accident called liberty.” If fascism (or related forms of despotism), in Vargas Llosa’s estimation, is a threat on the grounds of its irrationality, then leftism, from democratic socialism to Soviet communism, remains a greater threat still for its overestimation of human reason. Given liberalism’s defeat of its rival systems (this, of course, is the historical account we’re working with here, despite the crucial Soviet role in destroying the Third Reich and the subsequent absorption of former Nazis into the liberal West, from Kurt Waldheim to Klaus Barbie), the enemy to be resisted is the specter of planning.

The rejection of planning, which Vargas Llosa attributes to both Hayek and Popper, is a difficult idea to hold philosophically in your mind. After all, human affairs do not simply unfold. People respond to stimuli and instruction, however implicit, and it is governments and social institutions, among other things, that form the conditions of the lessons we learn. The critique of planning, then, seems not to be the choice of freedom over determination, but rather the preference for certain kinds of decisions over others.

But I think this is not a question of argumentative slippage, much less of hypocrisy on Vargas Llosa’s part. In keeping with his selection of thinkers, his interest is not in dissecting the arguments for liberalism but simply in defending them, by whatever means prove efficacious. The Call of the Tribe is as much a manifesto and a homage as it is a study.

Vargas Llosa’s rejection of the left, then, is largely based on the bad actions committed by some leftists, which he takes to be indicative of the rot at the heart of the entire enterprise. When he learns of Castro’s detention centers, he sees them as evidence of the regime’s fundamental nature. By contrast, the regimes of both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan are praised for introducing a new dynamism into British and American life—and as for their funding of death squads from Ulster to El Salvador, the flourishing of private prisons, or the more or less constant state of crisis we have lived under since this neoliberal revolution, these are, to the extent that Vargas Llosa addresses them at all, so many broken eggs in the world-historical omelet. In less triumphant moments, the book’s message seems to be that when a liberal government commits crimes and human rights abuses, it is simply failing to understand or live up to its own ideals.

But the contents of liberalism itself are subject to similarly shifting sands, even contrary tendencies. When Ortega fails to acknowledge the superiority of free-market capitalism to central planning, Vargas Llosa deems his liberalism “partial,” whereas Hayek’s liberalism consists precisely in his transcending the merely economic. And when Hayek praises the murderous, repressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, this is simply an example of one of his “convictions [that] are difficult for an authentic democrat to share.” No more discussion is given to the matter. Perhaps Vargas Llosa is remembering who the real enemy is: When Pinochet was arrested for crimes against humanity in 1999, Vargas Llosa penned an op-ed for The New York Times asking why, if the world was willing to condemn the right-wing dictator, it was not also willing to condemn the left-wing dictators of the world, chief among them Castro.

Vargas Llosa retains much of his power as a prose stylist, and there are moments when The Call of the Tribe provokes a genuine thrill of discovery—a sense that, for good or ill, it was these men whose ideas have driven the history of the last half-century. Nevertheless, there are just as many moments when these accounts of intellectual adventure and individual liberty begin to sag, when the insistence that no system or ideal other than free-market capitalism and liberal democracy can ensure the conditions for individual and social flourishing becomes almost a mantra, an utterance unanswerable not because it is flawless, but because it doesn’t seem made with dialogue in mind.

What does such a hagiographic approach offer to anyone who is not already a believer? This question returns us to what we can learn from the literature of disillusionment. Why, when liberalism is merely the natural and rational position to hold, does it require such a defense? Vargas Llosa allows us a glimpse behind the curtain in his discussion of the argumentative style of the outwardly modest Isaiah Berlin: “Fair play,” he writes, “is only a technique that, like all narrative techniques, has just one function: to make the content more persuasive. A story that seems not to be told by anyone in particular, that purports to be creating itself, by itself, at the moment of reading, can often be more plausible and engrossing for the reader.”

So why disillusionment? It’s a narrative mode with obvious religious connotations; it is a story about the revelation of the true religion, the smashing of false idols and the embrace of pure faith, at which point “religion,” as such, becomes the enemy, or at least a danger to be wary of. This same structure played out in colonial encounters—colonists described natives first as having no religion and then, once European Christianity gave way to secular humanism, as being slaves to it. So it is perfectly consistent to point to Marxism or leftist politics generally, as Vargas Llosa does (drawing especially on Popper and Raymond Aron), as primitive, tribal, religious. “Religion,” in this tradition, is what other people do.

It is this historical double play that illuminates the real power of the narrative of disillusionment. It aids in the creation not of two sides of an argument, but of a natural (that is, a non- or even subhuman) phenomenon and a neutral observer. Such an observer may have a commitment to “flexibility,” as Varga Llosa insists that all liberals—whether individual thinkers or governments—must, but such a duality nevertheless depends on a carefully guarded wall between the wildness out there and the reason in here. It is the complexity of a world of actions and relations, decisions and consequences, congealed into a world of determined possibilities that will remain hidden unless you simply, though perhaps painfully, grow up. When the demand is made so insistently, one begins to wonder what measures might be justified in dragging the reluctant into the light.

I have to admit that by the end of The Call of the Tribe, I felt a kind of malaise, having read the litany of liberal virtue in so many iterations. Why, the question nagged, in its fourth (or, arguably, eighth) decade of nearly unchallenged global hegemony, do the representatives of Western liberalism feel the need to defend it against threats that have been for so long neutralized? And then it occurred to me that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup d’état, the death of Salvador Allende, and the beginning of a decades-long tyranny supported and praised by, among others, Hayek, Friedman, and the US government. Allende, as it happens, is one democratically elected socialist for whom Vargas Llosa, if this book is any indication, retains some sympathy, if only in retrospect. Perhaps, he seems to suggest, the transition to a more fully liberal economy could have been accomplished more smoothly, less forcefully. Still, the Chicago Boys took over, the left was destroyed, and it is in the nature of stories to be retold, of rituals to be performed, of victories to be commemorated.

0 notes

Text

JUDGING CRITICAL THEORY, III

[Note: This posting is subject to further editing.]

An advocate of critical theory continues his/her presentation[1] …

This current series of postings is reporting on the basic elements of critical theory, the main antithetical view to the dominant natural rights view that Americans mostly favor when it comes to governmental/political thought. Critical theory is a view that focuses its concern on political qualities of domination and authority. Readers are invited to review the last two posting of this blog for how it, the blog, has introduced this construct.

Part of that reportage was describing how critical theory grew out of the efforts of a multidisciplinary group of scholars who established the Frankfurt Institute. Their initial efforts, due to German politics during the 1930s, found these scholars moving the Institute eventually to New York City. After the ensuing years in which World War II transpired plus some stabilizing years, the Institute moved back to Frankfurt, Germany.

Changing its name once again – to the Frankfurt School – they were able to skillfully advocate their political positions and garnered a good degree of influence in a conservative West Germany. With this re-establishment in their original location, this group during the 1950s and ’60s aimed most of its efforts at attacking positivism. That is, these scholars found a good deal of fault with the trend among the social sciences to adopt more rigorous scientific protocols in conducting their studies.

This specifically meant that social sciences – which relied heavily, up to that time, on more narrative/historical forms of research – focused on hypothesis testing methods in which observations of human behaviors were measured to discover significant correlations between independent and dependent variables. This was deemed to be a major obstruction to the School’s main aim, i.e., to change society.

Why? Because the behavioral approach objectified the study of politics while the Frankfurt group’s change-oriented aim relied heavily on normative questions – change presupposes value determinations. And adding fuel to this disaffection of the prevalent social sciences was, at that time, a highly emotional development, that being the student anti-war movement – mostly a reaction to the Vietnam War – that both Europe and the US was experiencing.

The resulting disruptions between those in power and anti-war demonstrators with allies like leftists from the Frankfurt School, grew and featured concerns over the various forms of subjugation the School was highlighting which mostly affected either low-income groups or targeted groups of prejudicial policies or both. And this fed into the School’s concern with social science modes of research.

The “establishment” – made of those who belonged to privileged groups – was adopting behavioral approaches in their analyses of social realities and they stood in support, for the most part, with the war footing against Communism. Partly due to World War II lessons – appeasing aggression from “foreign” invaders – and capitalist aims to expand their markets across the world, there seemed to be tunnel vision among the power centers as to what appropriate policy should be adopted concerning such developments as those being witnessed in Southeast Asia.

The School found itself, again, in an uncomfortable domestic environment in Germany due to the disruptions associated with the anti-war movement. At that time, though, new blood was making its way into the School’s ranks. One such newcomer was Jurgen Habermas, who introduced a very influential communication theory.

That theory points out the necessity for participating actors of various social arrangements – whether they be federated (in agreement) or antagonistic – to recognize the intersubjective validity among their claims so that social cooperation can be achieved.[2] This is veering critical thought further from pure Marxist thinking (a trend pointed out in previous posting), albeit not in contradiction to it.

Was there a complete divorce between Marxists and critical theorists by what critical theorists were promulgating through the School or other platforms? One area that these critical scholars seem to have maintained a strong link with Marxist thinking was their rejection of purely objectified social science research.

And by transcending the boundaries among the various social sciences – becoming highly interdisciplinary – and other related disciplines (such as linguistic or aesthetic studies), these writers started to find fault with segregating these objectified studies from normative political theory as indicated above.

In so doing, they fell squarely with Marx and his views that it is essential to keep social science protocols (of either historical or behavioral-based types) and social criticism relatable to each other. The former provides the means, but the latter keeps such efforts along justifiable rationales which, in turn, help those involved in exerting the energy and expending the resources such research demands.

Despite this link, Marxist scholars, for their part, found it offensive that critical theorists would be disposed to seemly leave behind Marxist focus on proletarian revolution and the energetic adoption of going into other non-Marxist sources of scholarship to inform the substance of their research and writings.