#analytical essay

Text

ok people here's my essay. (also note that this was for my english class so it is written in a different style than i usually would. it had to be all formal and grammatically correct and such)

2212 words, analytical essay

She-Ra and the Princesses of Power: A Queer Allegory for Religious Trauma

ND Stevenson’s She-Ra and The Princesses of Power is an animated Netflix original series rebooting the classic 80s show Shera: Princess of Power. This time, however, the show is chalk-full of diversity, varied body types, queer representation, pleasing colour palettes, and a friends-to-enemies-to-lovers lesbian romance. The first four seasons follow Adora (aka She-Ra) and the princesses of Etheria’s fight against the Evil Horde, using their magic to try bringing peace and justice to the planet. A portal is opened at the end of the fourth season, however, bringing the planet of Etheria out of the isolated dimension of Despondos. No longer separated from the rest of the universe, Horde Prime arrives at Etheria- not only bringing higher stakes than any season preceding it, but an entirely new layer of symbolism to the series. The final season was a clear allegory for religious trauma, an especially relevant topic for the show’s majorly queer audience.

When his armada arrives at Etheria, Horde Prime sends his army of clones and robots down to take the planet by force. Unlike the Evil Horde that had been trying to take the planet before Prime’s arrival, who were disorganized, messy, and industrial, everything under Prime is sleek, elegant, efficient, and most importantly: white. Horde Prime’s ships are white, Horde Prime’s robots are white. Horde Prime’s skin is white, his hair is white, his clothes are white, as are all his clones. Pure, unblemished white, with only sparing accents of grey or green.

In colour theory, white has a few meanings. The colour can represent purity, cleanliness, innocence, and even righteousness. This colour theory is heavily incorporated into biblical verses, metaphors, and artwork (and some might even argue that our modern idea of white comes from the Bible). In art, God and angels are almost always depicted wearing white, as is Jesus in his resurrection. Halos of white or light yellow are shown adorning holy figures' heads. Several bible verses use white robes or other white objects as a metaphor of the wearer’s purity. White is still used in several Christian rituals/customs today, such as weddings, baptisms, and more. White is one of (if not the) most important colour in Christian lore. Even in instances where pure white isn’t used, there is a clear correlation between light versus dark and good versus evil.

White has more than one meaning, however- on the opposite side of the coin, white can also represent coldness, blankness, emptiness, and loneliness. The most interesting thing about the show’s use of white is that it encapsulates both facets of its representation. Horde Prime uses white to represent his purity and perfection, but to the people of the colourful, messy world Etheria, this is a cold, eerie colour. As are Horde Prime’s ideals. His perfection and purity is synonymous to coldness. The white represents both- not only simultaneously, but as the same thing.

Horde Prime’s empire being entirely white is no coincidence- neither in-story by Prime, nor in real life by the writers. Horde prime uses white to represent everything he stands for, and the writers use white to represent everything Christianity stands for.

Horde Prime is a being that has lived an amount of lifetimes beyond comprehension- every time his body starts to grow old and fail, he selects a new clone of his to insert his memory and very essence into. So even though he has a new body, he is still him. And the reason for this? To fulfill his self imposed purpose of bringing peace and perfection to the universe. To thousands of planets he has been, one at a time, to reach this. Horde Prime believes there is only one right way to do things, and that humanity cannot be trusted to govern themselves.

Every planet he takes goes the same: he arrives with his ships, and slowly implants chips into the neck of each and every being on a planet. These chips take away the autonomy of the host, and they are left blank. No personality, no choices, no person. All their actions are perfectly automated and controlled by a hive mind, and Horde Prime can take specific control of and see through the eyes of any individual at any given time. With Horde Prime in control, there is no war, no famine, no pain. There is only peace, perfection, and purity. And anyone who does not conform, does not accept his gracious rule, are dealt with accordingly. Entire planets have been left desolate and barren, entire peoples subjected to genocide for not accepting Horde Prime. All dead in the name of peace.

These ideals upheld by Horde Prime are strikingly similar to Christianity. Perfection and purity are two of the main ideals of Christianity, in hand with righteousness. Christians strive to “be like Jesus,” to be their idea of a good person, to be loyal to their religion, and to make it into Heaven. Several rituals to “repent” exist when they feel they have not upheld these standards correctly- including prayer, confessionals, sacrament, and baptism. Even though true perfection, purity, and righteousness are typically seen as unattainable to everyone but the Godhead, it is common belief that constant trying will at least get you as close to it as possible. Conformity is another key aspect of Christianity, though it is not advertised, and to the exact extent it is upheld depends on the sect. In general, though, Christianity pressures every one of its followers (and even those who aren’t) to behave a certain way, to think a certain way, and to only associate with others among themselves.

Horde Prime’s way of upholding these ideals isn’t dissimilar to Christianity’s either. Much like Horde Prime’s Galactic Empire, Christianity has had a long history of forced assimilation. From the Spanish conquistadors to the pilgrims and other colonial settlers of North America, death and pain has come in the wake of the spread of Christianity for hundreds of years, amongst various sects of the religion. Native peoples have been murdered for their loyalty to their “savage” non-Christian ways, land has been stolen, and indigenous religions and other important cultural traditions have been changed past recognition or completely erased, all in the name of “saving,” all in the name of “love,” all in the name of “what’s right,” all in the name of God. Christianity is the only right way, Horde Prime is the only right way.

Its likeness to Christianization isn’t the only resemblance Horde Prime’s ways share with Christianity, however. When Horde Prime arrives at Etheria, three people are brought aboard his ship- Queen Glimmer, one of the Etherian rebels that had been fighting against the Evil Horde (and now the Galactic Empire), Catra, a high-ranking member of the Evil Horde that had been taking over Etheria before the Galactic Empire arrived (but is in love with Adora, who is one of the rebels), and Hordak, the leader of the Evil Horde. Hordak was a clone of Horde Prime’s that had been stranded on Etheria, which was in an isolated dimension. He spent his time in isolation trying to take the planet so that if he was ever reunited with Horde Prime, he would be seen as “worthy”. Horde Prime, however, is displeased by Hordak’s actions- claiming that Hordak was trying to take the planet for selfish reasons rather than for Horde Prime, and for giving himself a name. As such, Hordak must be “purified.”

In this purification process, Hordak’s mind is wiped, and he begs for forgiveness and to complete the process. He is then dressed in white and walks into a circular pool with liquid that reaches his waist. The liquid is electrified for several moments, and his screams can be heard, and then it stops. He is left blank, and Horde Prime and the other clones watching praise him for being the purest among them. Later, Catra is subjected to the same process against her will, and is now a mindless servant of Horde Prime as well. This process is almost identical to the Christian concept of Baptism. While exactly how baptism is carried out varies between sects (full submersion under water versus just a sprinkling, infant versus child, etc), the purpose remains the same- to purify past sins.

A more abstract similarity between Horde Prime’s empire and Christianity is the use of titles. Prime’s clones refer to each other as “brother” (and to Catra as “sister,” once she has been “purified”), and Horde Prime as “big brother.” Not all sects of Christianity use such titles to refer to each other, but some do; notably Catholic nuns or members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons). But even those sects who do not refer to each other as brother and sister often view Jesus as their “older brother” and God as their “heavenly father.”

Horde Prime himself has many more titles than simply “brother” or Emperor of the Galactic Horde, however. Other titles given to him include Ruler of the Known Universe, Regent of the Seven Skies, He Who Brings the Day and the Night, Revered one of the Shining galaxies, and Promised one of a Thousand Suns. In Christianity, Jesus also is referred to by many names. The Saviour, the Redeemer, the Son of God, the Son of Man, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, the Prince of Peace, the Lamb of God, and several more. In addition to titles, some of the phrases in general used by Christians and the Galactic Empire are common. Both use the word “rejoice” when telling of their faith. Amongst Christians, “glory to God in the highest” and “[God] is the same yesterday, today, and forever” are not uncommon phrases. “Glory be to Horde Prime” is a common phrase expressed by the clones, and even more so, the infamous mantra “Horde Prime sees all, Horde Prime knows all” repeated so many times throughout the season.

The titles used for each other perpetuate a feeling of conformity and a feeling of “otherness” concerning those who do not conform. The titles used for their leaders perpetuate subservience, power imbalances, respect, and devotion. The phrases used in relation to their leaders perpetuate devotion and omnipotence. These are true of both Horde Prime’s Galactic Empire and Christianity.

Horde Prime was a genuinely disturbing villain who represented every painful thing Christianity is made of- toxic perfectionism and purity, conformity, obedience, control, and omnipotence. Loss of expression and individuality. The fear of being constantly watched. These are things that anyone with religious trauma may deal with, but it’s especially true of queer people. Queer people have had a long history of oppression at the hand of Christianity (and colonialism in general). From outright murder to conversion therapy and other abuses, from abandonment to dismissal, Christianity has perpetuated all of it for centuries. And it’s still something that happens today.

She-Ra and the Princesses of Power has a majorly queer audience, due to both the creative process of the show and the representation within the series itself. Not only is the creator of the series (ND Stevenson) queer, but so was practically every character- whether they were a main character, side character, or background character with only a few seconds of screen time. One of the main plots of the show is the complicated lesbian romance between Adora and Catra. As such, the series attracted a good number of queer fans, and religious trauma (or at the very least, religious fear) is a topic that hits uncomfortably close for many.

Other pieces of media that incorporate religious imagery have a tendency to be unclear about how it is framed. Is the imagery shown to be wrong and the victim is right and prevails? Is the imagery shown to be right, and the pained victim in terrified denial? Is the imagery shown to be truly wrong but inevitably triumphant anyways, no matter what the victim tries? It is so muddy in so many pieces of media. The important thing about the fifth season of She-Ra and the Princesses of Power was how it was framed. Perhaps it was because it was a kids show, or perhaps it was the queer creators’ spirit and defiance, but the series was clear in their framing of Horde Prime. The perfect white make the audience uneasy. Horde Prime’s retelling of his victories fill the audience with dread and then hollowness. The “baptisms” of Hordak and Catra are disturbing. Every aspect of Horde Prime and everything he stood for was presented as wrong. Without any doubt.

And even more importantly, the people of Etheria were able to prevail. She-Ra and the other princesses were able to defeat Horde Prime and his empire, and free those forced into subservience by his chips. Catra (and Hordak) were saved. The ships were destroyed. The people of Etheria were allowed to be free and express themselves and be people. This message was something very important to the queer audience. Not only was the fifth season an expression of queer pain, but an expression of queer hope. Neither thing should be ignored. Pain is valid. Hope is needed. To be healthy, both need to be recognized. To have a series that expressed both, and in such a queer way, was extremely important to so many people.

#long post#unityrain.txt#tw christianity#religious trauma#christian religious trauma#ex mormon#shera#she-ra#she ra#spop#shera spop#she ra spop#she ra and the princesses of power#she-ra and the princesses of power#shera and the princesses of power#meta#analysis#analytical essay#horde prime#the galactic empire#hordak#spop meta

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I wrote an essay series breaking down the lyrics, symbolism and messages of The Oh Hello’s Four Seasons EP’s, would anybody read them? I like analyzing lyrics and poetry as a hobby and I was curious if anyone else would follow along with me.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

bondage and binaries: autonomy recontextualised as a narrative device in science fiction

increasingly popular in mainstream media, science fiction has deep roots in both ancient storytelling and the gothic. the genre covers an expanse of themes that remain socially relevant throughout the entirety of its career; autonomy, transgression, transformation, and corruption. these themes originate from the gothic, the heart of many modern genres. science fiction repurposes gothic themes in fantastical, dystopian and extra-terrestrial contexts and serves as both a well-received source of entertainment and a mode of social commentary. consistent through various eras of sci-fi is the theme of autonomy. much like the gothic, sci-fi stories reflect the social fears prevalent at the time of writing: the fear of a loss of autonomy has always remained an anxiety of western audiences. this fear presents itself in various contexts throughout time. for instance, western societies have dreaded losing autonomy to religious figures abusing their authority (1790s), eastern european immigrants (1890s), and the corruption of the state and technology (1990s). matthew gregory lewis’ ‘the monk’, bram stoker’s ‘dracula’ and the wachowski sisters’ ‘the matrix’ address all these, respective to their time period. bondage has it’s place as a narrative device when it comes to depictions of autonomy as many authors use restraints as a tool to create a sense of helplessness against threat, or to symbolise social or interpersonal constraints. the core difference, of course, between restrains and bondage is that bondage exists in a sexual context and provides gratification for one or both of the parties involved. another key trope of the gothic, and by extension science fiction, is the involvement of taboo, perverse or otherwise transgressive behaviours. the atypical, ‘transgressive’ nature of bdsm gives it’s use in media that relevance, fulfilling two notions of the genre at once. additionally, both styles, at least in their earlier stages, utilise what is referred to as ‘dark romanticism’. this involves taking the stylised language of romantic literature, characterised by purple prose, decadent architecture, etc, and recontextualising it in darker, more morbid settings. the contrast between this lyrical writing and the macabre, violent, alien or taboo content that it is used to describe creates an uneasy, disjointed feeling for audiences. the dynamic between language and content weaves uncanniness into the structure of both genres, which defines them and distinguishes them from other forms of storytelling. for this reason the nature of bondage is integral to the discomfort that sci-fi relies on.

to understand the significance of this writing style and how it characterises science fiction, we need to first understand the chronology of the genre and what impacted its development over time. while sci-fi as we know it today is largely influenced by the gothic, we see fantastical elements in some of the earliest works of fiction, such as the epic of gilgamesh (around 2000 bce) and the indian poem ramayana (5th-4th century bce). ramayana tells of vimana, which are mythological flying palaces or machines that have the ability to travel underwater, into outer space, and to use advanced weaponry to decimate cities. these early references to technology, often used as narrative devices, are a common theme among ancient works of literature. similar examples include the rigveda collection of sanskrit hymns from approximately 1700-1100 bce; the first book contains a depiction of ‘mechanical birds’ that are ‘jumping into space speedily with a craft using fire and water…containing twelve pillars, one wheel, three machines, three hundred pivots and sixty instruments.’ descriptions of technological inventions like this can be found both in early literature, and in later works such as mediaeval stories. it was just prior to the era known as the ‘enlightenment’, which is credited to have begun in 1685, that science fiction started to morph into the form that we see today. 16th century european works such as thomas moore’s ‘utopia’ (1516) and ‘the faust legend’ served as early prototypes of science fiction tropes. moore’s work was the basis for the utopia motif used in sci-fi, similar to how the ‘faust legend’ exemplified the emerging ‘mad scientist’ trope. when the enlightenment era began in europe, it signalled a dramatic shift in thinking, from blind religious faith to knowledge obtained by ‘means of reason and evidence of the senses.’ this was largely influenced by the separation of the church and state, and sparked a wave of speculative fiction concerning the sciences, including: jonathan swift’s ‘gulliver’s travels’ (1726), exploring alien cultures and unusual applications of science, and margaret cavendish’s ‘the description of a new world, called the blazing-world’ (1666), describing a noblewoman’s discovery of an alternate world in the arctic. however, mary shelly’s 1818 ‘frankenstein’ is widely regarded as a major turning point for modern science fiction. shelly’s gothic horror text is the moment where sci-fi and the gothic converge and began to share core elements before developing in their own separate directions again.

shelly’s use of science, and of technology beyond the scope of scientists in her time period as a conceit to drive the narrative is a hallmark of science fiction as we engage with it in the twenty-first century. she develops upon the notion of a ‘crazed scientist’, using the contrast between technology and religion as an extended rhetorical device to alienate frankenstein’s monster. brian aldiss, in ‘billion year spree’ makes the case that ‘frankenstein’ represents ‘the first seminal work to which the label [science fiction] can be logically attached.’ he goes on to argue that science fiction in general derives from the gothic horror novel. the usage of science as a narrative device is one among multiple tropes and elements that shelly imparted to sci-fi with her work. in having an ‘alien’ character fulfil the role of antagonist, shelly comments on the human condition from a new perspective. as put by kelley hurley, ‘through depicting the abhuman, the gothic reaffirms and reconstructs human identity.’ frankenstein’s monster, referred to often as ‘the creature’ is born into bondage; a popularised image from the novel, and several film adaptations, is that of the creature strapped to a board surrounded by rudimentary scientific equipment. from his first introduction to the world, he has no autonomy. these restraints strip him of humanity and reduce him to an experiment. they are not only physical and have practical use, but are symbolic over his general lack of control over the creation of his body, this perverse ‘otherness’ and the public’s decision to outcast him. frankenstein’s monster is an alien in every sense of the word, and it is the subjugation he is born under that characterises him as such. shelly’s work emerged just prior to the fin de siecle (turn of the century), where western science experienced rapid development, which in turn increased the volume of speculative fiction being produced. after ‘frankenstein’, the gothic and science fiction generally parted ways again, but sci-fi now had a host of characterising traits lended to it by shelly’s novel. the general recipe for modern science fiction is a combination of fantasy literature, gothic horror, and advances in western science, allowing us to pinpoint the fin de siecle as a catalyst for the development of the genre. as the era continued, more proto-science fiction was published; most notably was ‘journey to the centre of the earth’ (1864), by jules verne. the tale combines adventure, romance, current technology and predictions of future technology. lyon sprague de camp, an author active in the ‘golden age’ (1940/50s) of science fiction, refers to verne as ‘the world's first full-time science fiction novelist.’

understanding the outlined framework that modern science fiction operates under, we have space to explore the relationship between bondage and sci-fi in detail. in ‘aesthetic violence and women in film’, joseph h kupfer describes violence as having three framings: ‘symbolic, structural and as a narrative essential.’ as previously discussed, violence is an integral factor in the structure of science fiction, starkly contrasting the writing style to create unease. as a narrative device, restraints are often used in conjunction with rising conflict, to create adversity for characters that drives the plot onwards; this is how it functions as a ‘narrative essential.’ the final facet of the relevance of violence is symbolic. typically, women, queer men and ethnic minorities in fiction experience violence on a symbolic level; their identities are seen as purely political, and thus they face adversity against an themselves as an idea rather than as individual people. both the gothic and science fiction rely on the use of the ‘Other’, usually referring to uncanny or supernatural creatures, and often minority characters are ‘Othered’ to code them as a threat to audiences. in this instance, physical restraints are often representative of social, interpersonal or systemic barriers against a character, and by extension, against the minority that they belong to. to exemplify this, we can turn once again to shelly’s ‘frankenstein.’ while frankenstein’s monster is not immediately recognisable as a minority, lennard j davis has insisted the ‘creature’ is disabled or at least treated as such: ‘hideous appearance...inarticulate, some- what mentally slow, and walks with a kind of physical impairment.’ this interpretation of the character leans more towards the social model of disability, rather than defining disability as an impairment of the body or mind, making his argument somewhat controversial. frankenstein’s monster is not functionally hindered, but he is characterised by his disfigurement and unconventional appearance, which davis refers to as ‘a disruption in the visual, auditory, or perceptual field as it relates to the power of the gaze.’ his estrangement from society reinforces his animosity towards people; bound by the physical limitations of his disability, he develops into a ‘monstrosity’ as a result of his ableist environment. this reading sees ableism through the lens of bondage, as a social restraint or barrier that alienates the creature. he is born into physical restraints, strapped to an operating table, and is followed by metaphysical constraints that bar him from social function and acceptance. in his initial creation, what defines our understanding of the use of bondage is the power dynamic; victor is the dominant authority, controlling the movements of the creature, while the creature himself is subordinate to him, with no birthright to autonomy. his inability to control what victor inflicts upon him is illustrated by his restraints, and becomes an extended metaphor for his alienation and lack of autonomy throughout the novel. shelly’s work serves as a commentary, intentional or not, on the estrangement and ‘othering’ of disabled peoples and the impacts this has on their wellbeing and understanding of themselves. additionally, the novel functions almost as a warning tale surrounding the concept of abusing the development of science, and ‘playing god’ as victor does.

adjacent to science fiction is the genre of magical realism. it utilises the fantasy aspects of sci-fi and combines them with a realistic worldview to blur the lines between magic and reality. angela carter’s ‘the erl king’ (1979) is a prime example of using fantasy to illustrate social and systemic bondage in similar ways to sci-fi. carter uses imagery of caged birds to create a visceral picture of female entrapment. interestingly, the metaphor of caged birds can be likened to that of emerging feminism. in mary wollenstonecraft’s ‘a vindication of the rights of women’(1792), she argues that women of the eighteenth century were ‘confined in their cages like the feathered race.’ similarly, carter refers to ‘larks stacked in their pretty cages you’ve lured.’ rather than reinforce the idea that femininity is inherently trapping, carter uses this concept to create an almost tangible illustration of the narrator breaking the cycle of this ingrained imagery. in freeing the erl king’s victims and usupring his position of sexual power, the narrator subverts traditional tropes of female submission and prevents violence against women rather than indulging in it. this is evidence of carter’s signature feminist twist: she writes from the perspective of second-wave feminism. the use of ‘caged bird’ imagery as an allegory for violent and sexist systems is reminiscent of the usage of restraints in science fiction and indicates its relevance across similar genres. sexism and female entrapment are forms of social bondage in ‘the erl king’ the same way ableism is in frankenstein. genre differences aside, carter’s work is an example of how bondage as a narrative device has developed throughout literature. while in more traditional texts, it is used to trap and villainise ‘Othered’ characters, or to demonstrate an antagonist is a threat to audiences autonomy, more modern texts take the approach of reclamation. not only does carter subvert the roles of bondage to allow minorities to shift the power dynamic, she holds up a mirror to society and allows them to witness the abuse of power that she is dismantling. this subverted approach to bondage as a narrative device began to emerge in western literature in the 1970s. second wave feminism and the beginning of what is known as the ‘post civil rights movement’ era in the united states shifted the dynamics of western society in a way that we see reflected in media. as more legislation was put into place in both the united states and united kingdom to protect the rights of more marginalised groups, media produced at the time began to reflect these sentiments. while this does not apply to all movies and literature, many authors began depicting the state as the topic of fear, rather than villainising minorities.

a core example of dystopian fiction that comes to mind is margaret atwood’s ‘the handmaid’s tale’ (1985). themes of subjugation, autonomy and reproductive rights run through the novel. atwood stated that the novel is speculative fiction, rather than science fiction, as she ‘didn't put in anything that we haven't already done, we're not already doing, we're seriously trying to do, coupled with trends that are already in progress... so all of those things are real, and therefore the amount of pure invention is close to nil.’ while this distinction has massive significance in terms of the social commentary atwood is offering, her work still operates, in part, under the writing structure of science fiction. the year of the book’s release, reviewers commented on ‘the distinctively modern sense of [a] nightmare come true, the initial paralyzed powerlessness of the victim unable to act.’ atwood depicts the social bondage enforced upon women by the theonomic, totalitarian state by building an environment full of physical limitations; women are treated as commodities and are stripped of the right to chose clothing, sexual partners, pregnancy, and so on. these are all forced upon them in very particular ways, to the sexual benefit of both men domestically and men in authority. ‘the handmaid’s tale’ combines two core aspects when it comes to control. the fear of religious figures abusing their authority, which has deep roots in both traditional gothic literature and true historical events, and the fear of a surveillance state, often utilised in modern science fiction.

the 2017 television adaptation of ‘the handmaid’s tale’ uses forms of physical bondage as a clear symbol of control: red or leather ‘masks’ are worn by handmaidens as ritualistic punishment for ‘disobedience’ or ‘independent thought’, covering their mouths, and handmaidens are often forced to wear veils. this use of bondage is multi-dimensional; it prevents women from seeing and being seen, from speaking and being heard. it removes the humanity of the individual and solidifies their objectification.

similarly, a well-loved trilogy in modern sci-fi, the wachowski sisters’ ‘the matrix’ (1999) truly leans into socially relevant anxieties surrounding the corruption of the state. the movie itself was ‘born out of anger at capitalism and the corporate structure and forms of oppression’, according to lilly wachowski. the film’s core message is one of reclamation and rebellion against a controlling state; aside from the anti-capitalist rhetoric driving the plot, many of the constraints shown represent social barriers preventing the population from experiencing reality or affirming their own identities. twenty three years from it’s release, ‘the matrix’ is more widely understood now as an allegory for the sisters’ experiences as transgender women in an unaccepting society. there are various uses of bondage and unbalanced power dynamics built into the plot, largely where the ‘agents’ of the state hold authority and dominance whereas the ‘rebels’ and general population are the subordinates being controlled. an example of this is a scene where the protagonist, neo, refuses to cooperate with these agents. in retaliation, they fuse his lips together, removing his ability to speak for himself and creating a terrifying, mangled version of his original face. neo is then pinned down as a ‘tracking bug’, shown to be a robotic centipede, is implanted in his torso. the agents, the dominant force, take his display of autonomy as a threat, and immediately respond with physical restraints in an effort to control it, or at the very least discourage it with scare tactics. this sentiment is echoed in other media, such as the aforementioned masks in ‘the handmaid’s tale.’ forms of gags are often utilised as the ability to speak opinions, call for help, express oneself holds an incredible volume of inherent social value, and having that ability supressed or blocked creates a far more tangible image of the loss of autonomy that resonates strongly with audiences.

a popular image from ‘the matrix’ comes from the infamous ‘red or blue pill’ scene, where neo is exposed to the physical system used to keep the population in a simulated reality while their ‘bioelectric power’ is harvested by machines. gasping for air in a pod filled with liquid not dissimilar to that of the womb, neo is shown to be one of millions of humans being held in pods and kept alive via medical tubes. this is a particularly visceral method of depicting the world’s population as enslaved; humans are stripped of the ability to experience the ‘real world’ and are not even able or permitted to breathe on their own. the way humans are tied into their ‘pods’ that feed their consciousness into the matrix is an example of sci-fi utilising forms of restraint to represent vulnerability and abuse of power. while this is not, by definition, bondage as it does not include sexual arousal it does exemplify why restraints are a vital narrative device. in the context of the wachowski sister’s film, the constrains represent systemic barriers preventing the population from experiencing reality and affirming their own identities. even in instances like this where restraints are used against a protagonist who does not find pleasure in the experience, the perpetrator, such as the agents in the matrix, tend to react with pleasure and almost delight at having someone captive, and the arousal is on their end of the experience as the dominant figure in this interaction. modern sci-fi often has plots rooted in a protagonist or group of protagonists’ journey to dismantle corrupt systems, systems which are reflected as binding or restricting population’s bodies, choices and autonomy. the agents of these systems take pleasure in enacting this restriction as it is a method of maintaining their power and control. consequently, protagonists reclaiming control serves as a natural way for the tables to turn on oppressors and for the narrative to reach its’ hope-filled conclusion.

the aesthetics of bdsm have their place in modern science fiction, but specifically in the matrix. western gothic and alternative fashion appear to be culturally associated with bdsm accessories, namely chokers, harnesses, garters, and so on. kym barrett, the costume designer for the matrix, has stated ‘[the costumes are] reflecting back more obviously to what’s really going on in the world, so maybe subconsciously people are connecting to it.’ the cast sports ensembles comprised of latex, leather, harnesses and accessories; while their clothes must serve a practical purpose and be appropriate attire for action, this also comes across as a co-opting of bondage gear as an act of reclaimation. barrett goes on to explain, ‘when they go into the matrix, they create their persona, which is how they see themselves.’ the depth of these characters centres around their reactions to their oppression, and co-opting symbols of this oppression helps to reinforce their fight against it.

other iconic fashion uses of bondage such as vivienne westwood’s alternative lines of clothing follow a similar vein, described as ‘clothing and imagery that appear dirty, ripped, scarred, shocking, spectacular, cruel, traumatised, sick, or alienating.’ this description matches western societal perspectives on bdsm, specifically the practice of bondage. uses of bondage in the mainstream are often a tool in shock fashion, largely influenced by both the gothic and by punk. punk subculture in particular is built upon shock culture, and utilises bondage alongside the themes of anarchy and anti-capitalism to promote a deeply political message. again, bondage gear and physical restraints are co-opted to form an anti-establishment narrative that jeers in the face of social restraints. despite music and fashion not being the same as literature, we can still see bondage being used as a narrative device. westwood’s sado-masochistic inspired clothing saw the addition of a punk line, named seditionaries, in 1976 after the designer met with the sex pistols. as previously discussed, what defines the gothic genre is the uncanny relationship dynamic between two binaries: romantic language and horror content. this translates to the worlds of both fashion and music, where gothic or alternative content relies on the uneasy contrast between the glamour of fashion or the melodic sound of a song and the shocking, counter-culturalist ‘traumatised’ method of presentation, be it the bdsm influence in the design of a garment or the macabre lyrics. this places bondage at the forefront of alternative media and reinforces its’ relevance as a narrative device.

the history of science fiction narratives is peppered with taboos, bent social conventions and abuses of power. the genre’s framework is inherently a development of gothic framework, recontextualised in a fantasy setting. we rely upon science fiction as a means of coping with capitalism; it is therapeutic to see an unlikely hero burst into the office of a space warlord, a corrupt government, a rogue machine, and blow the fucking place up. in order to experience this catharsis, we have to be able to visualise the constraints that they are dismantling, and to see the perverse nature of them in the first place. bondage traps the core sentiment of a narrative in manacles and allows it to violently break free and confront audiences head-on. it asks the audience, do you feel restrained? do the systems restraining you take pleasure in holding you in place? do you see how unjust it is to be controlled? and as our protagonist triggers an exodus of people ripping off the duct tape, loosening the rope, and unlocking the manacles, our narrative device turns to the audience again and asks, do you see how just it is to be free?

i.k.b

#essay#analytical essay#film analysis#literature analysis#literature essay#books and literature#literature student#film student#copyright ikb#the matrix 1999#the matrix analysis#the matrix trilogy#narrative design#frankenstein#frankenstiensmonster#mary shelley#angela carter#the bloody chamber#the handmaids tale#margaret atwood#vivienne westwood#science fiction#sci fi#scifibooks#scifinovel#gothic#gothic novel#gothic literature#gothic architecture#wachowski sisters

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

BS Analysis no. 2: The Parody of Thick as a Brick

“Really don’t mind if you sit this one out…”

This may be the most ambitious analysis I’ve done yet, which is going to be a breakdown and analysis of Jethro Tull’s 1972 album Thick as a Brick, notable in the prog community for being an entire album comprising of a singular song: the titular “Thick as a Brick”. This song is divided into two parts, however, the only reason for the split was due to the limitations of vinyl records: a singular side of vinyl can only hold around 20 minutes of music, therefore the song needed to be split in two. “Thick as a Brick” pt.1 and pt.2 are a combined 43 minutes in length, with the album package as well meant to be taken as part of the piece. To highlight the meticulous creation of the iconic newspaper album cover, the album's recording took less time than the cover!

The newspaper album cover is important because it relays the story of Gerald Bostock: a fictional 8-year-old child prodigy whose poem, “Thick as a Brick” was disqualified from winning an award due to being too abrasive and, according to the article on the album cover, “unwholesome”. Bostock’s character was made up by frontman and flutist Ian Anderson, who wrote the lyrics to the song in character, describing Bostock’s choices as a young man: either to become a soldier and go into the military like his father or to follow his own wishes and to become a poet. Already present is this sort of layered story of creating a character, writing from that character’s perspective, creating a newspaper article detailing the character's life, and including an article in the newspaper that claims that the band set Bostock’s poem to music. It’s honestly a bit convoluted, which may have been on purpose.

The song itself criticizes British society, specifically that of the middle and upper classes, both satirizing the concept of being a proper gentleman that went into the military, and also being self-aware that poets, artists, and musicians can be too idealistic. The title of the song is essentially calling out the pretentiousness of supposed wisemen in society that assume they know everything with the lines, “So you ride yourselves over the fields/ And you make all your animal deals/ And your wise men don’t know how it feels/ To be thick as a brick”. These lines are in the song's first verse and are repeated at the very end, emphasizing the message and tying the whole piece together. It is interesting that the song deals so explicitly with class and one’s place in society, when prog rock itself primarily developed from people with middle-class British backgrounds, with a few exceptions, and that the main character is a prodigy, and several prog musicians have been called virtuosos at their instruments. This is especially notable since Ian Anderson has claimed in the past that the song is a self-aware parody of the genre, coming about after critics interpreted Aqualung as a concept album (which I’ll definitely share my opinions on at some point!). In response, he created Thick as a Brick.

Now, what is notable about Thick as a Brick is that it is a relatively early development in the history of prog: it was released on January 7th, 1972, which was before:

Foxtrot by Genesis (released in the spring of 1972)

Close to the Edge by Yes (released in the summer of 1972)

Trilogy by ELP (released in the summer of 1972)

Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd (released the winter of 1973)

Larks’ Tongue in Aspic by King Crimson (released in the spring of 1973)

Tales from Topographic Oceans AND Brain Salad Surgery, by Yes and ELP respectively (both released in the autumn of 1973)

This begs the question: if this is indeed a parody… what was it parodying?

Now, there were epic songs and concept albums in existence before Thick as a Brick: both of ELP’s prior albums had contained an epic song (“Tarkus”, released in 1971, and “Take a Pebble”, 1970), Pink Floyd had already done “Echoes”, and The Nice had done “Ars Longa Vita Brevis” all the way back in the 60s. However, the epic wasn’t really central to the prog genre yet, although the suite had existed for some time, and bands were experimenting with longer song forms. Besides, Jethro Tull wanted to move in a more progressive direction anyway, so why parody the form of music?

The parody of Thick as a Brick is not necessarily the music itself, although you could argue that it was exaggerating the music that already existed for comedic effect. However, Jethro Tull is considered a prog band after all, and this would not be the last of their prog works; what it is primarily parodying is the attitude of some prog musicians during the time period: to make their music longer, more experimental, more difficult to play, and more inaccessible to audiences. It does this by using jarring time signature changes, studio effects, some odd experimental sections, specifically in the second half, and of course, the length being double anything that came prior. Part of the parody, as well, is the concept: a child prodigy, writing about class conflict is reminiscent of both the backgrounds of many prog musicians and also reflective of how underqualified many of them are for making statements on political affairs, while also being the creation of a prog musician. They are simultaneously the overly confident and pretentious “wise men” that are described in the lyrics, and Bostock himself, making fun of the “wise men” while being a literal child and debating his own place in life. It is not a scathing criticism, however: the whole album does come from a place of respect for the musicians. Jethro Tull toured with several other prog bands and struck up friendships with various members of those bands, so it’s more of a reminder for prog musicians to take themselves less seriously.

Did they do that? Well… uh… no, not really. As evidenced by seeing what came out after Thick as a Brick, the music the prog musicians were making became even more ambitious and challenging, creating almost a self-fulfilling prophecy of Thick as a Brick being a parody. In fact, I’m willing to bet that at least one member of Yes saw this album, went, “Shit, Jethro Tull just made an album consisting entirely of one song, we’ve got to one-up Ian and the lads!”, and then proceeded to make Tales from Topographic Oceans. That’s not a diss towards Tales…, by the way, because I do love that album, but it is basically the very thing that Thick as a Brick was parodying, and it came out over a year after Thick as a Brick.

The unique thing about Thick as a Brick is that it is simultaneously a parody of the genre, while also making a genuine effort to make a prog album, so there is some sincerity in the themes that Anderson wrote about. It is comedic: how could anyone not laugh a little at the lines, “Your sperm’s in the gutter/ your love’s in the sink”, especially coming from a character that’s supposed to be a child? But, like any good parody, it also does have real messages and criticisms of not only progressive rock, but also British society in the 20th Century.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

clicky da linky

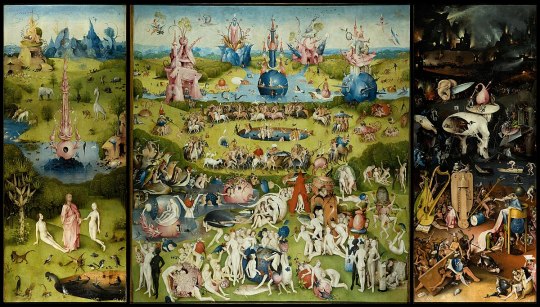

so excited to share my 13 page 12pt times new roman font single spaced analysis of The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch...... like literally even if no one reads it I get to know that I wrote the worlds most baller Bosch analysis essayyyyy ever bitchhhh likee.... just saying .. spent many hours slaving away at this (my first time writing an essay since high school?) just out of my own free will and it was incredibly rewarding wow....

opening and closing statements, to give you a taste:

"When first confronted with a painting as phantasmagorical in nature as The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1490-1510), the viewer will undoubtedly feel overwhelmed. The imagery that Bosch executes in fantastical detail depicts the rise of Man, his experience of transcendent earthly pleasure, and consequential fall. This narrative arc is splashed in a bawdy display of hedonism across the work, fabricated solely to instill a fear of God in its viewer"

... entire essay here...

"An incredibly complex work of art, The Garden of Earthly Delights was groundbreaking for its time, and is a strikingly beautiful display of well thought out thematic visuals and artistic knowledge. However wildly creative Bosch’s Garden is though, he was still confined to the boundaries of knowledge of the time he was in though, as well as late-medieval Christian morality and the desires of his patron. One can only imagine what Hieronymous Bosch might have conjured with the magic of his paintbrush in another time. Shrouded in mystique, this work is both a wonderland and hellscape of enigmatic creatures, lovers, and landscapes drenched in lust. Is it an honest and vulnerable look into Man’s defect of sin? A heavily dramatic warning on overindulgence? Or could it even be a sardonic mockery of the religious ideals of the time surrounding such things? Decide for yourself. This is a piece that has been notoriously debated for centuries, yet Hieronymous Bosch’s masterpiece still eludes factual explanation, and that is precisely what makes it so impressive to every generation of humans since its creation. This painting, and its lavish world within, will continue to nimbly evade any notions of earthly (or heavenly) actuality under the disguise of a ghastly premonition of what will befall Man for his birthright Sin for the rest of its existence. Bosch has created a masterpiece meant to evade explanation, strike terror into hearts, and expand minds."

#art history#art analysis#analytical essay#the garden of earthly delights#hieronymous bosch#renaissance art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing an essay in 6 easy steps

Despite Shakespeare's assertion that "the pen is mightier than the sword," the pen alone is insufficient to produce a successful writer. In truth, while we all want to be the next Shakespeare, creativity alone is not the secret to excellent essay writing. The norms of English essays, you see, are more formulaic than you may imagine - and, in many respects, they might be as basic as counting to five.

How to Write an Essay

For the best results, follow these 6 steps:

Read and comprehend the following prompt:

Understand exactly what is expected of you. It's an excellent idea to break down the prompt.

Plan:

Brainstorming and organising your thoughts will make writing your essay much simpler. Making a web of your ideas and supporting details is a smart approach.

Cite and use the following sources:

Do your homework. Cite your sources using quotations and paraphrases, but NEVER plagiarise.

Create a compelling thesis:

The most significant item you'll write in the essay is the thesis (primary argument). Make it a focal point.

Answer the prompt:

You may begin drafting the final draft of your essay once you have sorted out any bugs in your draft.

Proofread:

Read your response carefully to ensure that there are no errors and that you did not overlook anything.

Of course, each essay assignment is unique, and it is critical to keep this in mind. If one of these phases isn't relevant to the essay you're working on, skip it and go on to the next.

#essay#essaywriting#college essay#analytical essay#dissertation#thesis#programming#best assignment help#case studies#helpdesk#students

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m not sure when exactly this happened, but I think it’s clear that the aro community really is a community, now.

For the longest time I’ve felt like we were still in stasis, not quite there; a proto-community, yes, but not quite a community. But we have more history now to lean back on, more of each other to talk to and laugh with and cry with and learn from. More people that’ll go forward and make a part of modern aro history. More people that believe us, believe in us, will stand with us if we ask them.

I wouldn’t consider myself an aro elder yet, though each year I’m surprised at how long aromanticism has been a part of my life, how long I’ve been free of doubt or insecurity about my aromanticism, how far we’ve come since I was questioning. Then again, when I was questioning, some of the people I looked up to for guidance were probably close to the age I am now, so I might be there sooner than I think.

And, I’m so so hopeful for all aros, young or old, new or not, because we’ve come so far. Day by day, progress is slow (and yes, it’s unfair, it should be so much faster), but looking back it feels fast. We are our own role models, the people we look up to for guidance. We carve our own path through life, making things up as we go. I used to find that terrifying, because I had no idea what the future would bring. But it’s actually amazing, because I can ignore all these silly “rules” and guidelines about what my life should be, and instead ask, “what do I want my life to be?”

Younger me, you have no idea how awesome your future is gonna be. I’m sorry about the pain and hardship you’ll go through first; it won’t be fair and you shouldn’t have to deal with it. But you’ll make it through, and one day you’ll be me. I can’t wait for you to get here.

#aromantic#aro#aspec#queer#lgbtq#original#text#can't believe i was busy on a day when aromantic got super trending#also on the topic of history: history is super important and we should make sure we're good custodians of it!#make backups of your tumblr blogs/wordpress sites/fanfiction/analytical essays/whatever!#save links into the internet archive/wayback machine!#future aros will thank us for every thing we save from link rot#current aros will thank us for keeping our resources alive and accessible

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Suletta and Miorine's story is a romance: A Mobile Suite Gundam: The Witch from Mercury story structure analysis by Sodasa

So, I recently watched The Witch from Mercury, and I felt compelled to write an analysis of the show's use of the story structure of romances. I'm a hobbyist in the history of trends in genre fiction with a particular interest in romances. I thought it would be fun to use my area of expertise to talk about how the budding relationship between Miorine and Suletta is intertwined with the story of G-Witch.

Something particular about the romance genre is that, unlike other genres of fiction, it's mostly defined by its story structure. This means that just because a story is about two people getting together does not automatically make it a romance in the same way having magic in a story qualifies it as a fantasy. The flip side of this is that while you can't have a fantasy without fantastical elements, a romance can be put in any setting. As long as the story hits the required plot beats, it's still a romance. This makes Romance simultaneously one of the strictest and most versatile genres, as the plot can be anything as long as it ties into the main characters' developing relationship. Use this structure in a story about financial politics and mechs, and you get a story like The Witch from Mercury.

I think the show uses this structure very effectively. In my opinion, a great romance should, first and foremost, be an exploration of the part of the human condition where previous bad experiences make us reject intimacy. The romance story structure is designed to have the characters come face-to-face with their inner demons by giving them a reason to overcome them. Something that's a lot harder to pull off outside of romances, as not many things in life require us to overcome some of our deepest insecurities instead of just pushing them down.

G-Witch is a great show to use as an example of what makes a romance a romance as it follows the story structure almost to a tee, but it's also not the kind of story that most people usually think of when picturing a romance. I also believe that seeing the show through the lens of the romance structure leads to some juicy character psychoanalysis for Suletta and Miorine. I'll go over all the plot beats of a romance and explain how they apply to G-Witch and, if applicable, why I think you don't see those plot beats outside of romances. The names of the plot beats are taken from "Romancing the Beat: Story Structure for Romance Novels" by Gwen Hayes, which is also my primary source, along with my own extensive experience with the romance genre.

I hope someone gets something out of this. I have seen some excellent analyses and theories for this show, but they have been on things I don't know much about myself. Since the only part of story analysis I excel at is the structure of romances, I thought I'd lend my own area of expertise. I want to clarify that while I might sound matter-of-fact, this is just my opinion. I'm by no means saying that you have to think that G-Witch is a romance. I'm just arguing for why I personally consider it to be one.

#mobile suit gundam: the witch from mercury#g witch#the witch from mercury#suletta mercury#miorine rembran#sulemio#suletta x miorine#honestly I had too much fun making this#I can't write an analytical essay to safe my life#but I'll write a 7500+ words media analysis just to justify calling a mecha show a romance

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

I used to be one of those guys when I first joined the Kirby fandom, but everytime I hear a discussion of the series writing that starts with "So the Lore is InSaNe-" and not like, "Kirby has a fun writing style that takes advantage of its cute exterior to tell cool stories that reward player's curiosity and leave lots of room for imagination-" I cringe so goddamn hard.

I kinda just hate that people approach things that encourage investment when they don't expect it as inherently absurd. Like it is fun to joke about how absurd Kirby lore can be, but it really often comes with an air of disrespect or exhaustion rather than like, appreciation that these games are made by people who want to tell interesting stories when they could easily make as much money just making polished enough fluffy kiddy platformers. And when it's not met with exhaustion, it's met with - like I said before - that tone that it's stupid for a series like this TO have devs who care about writing stuff for it. Which is a whole other thing about people not respecting things made to appeal to kiddie aesthetic or tone.

Maybe the state of low-stakes YouTube video essays just blows cause people play up ignorance and disbelief for engagement, but like I STG I hear people use this tone for like actual narrative based games sometimes. Some people don't like... appreciate when a game is made by people who care a shitton in ways that aren't direct gameplay feedback. And they especially don't appreciate it when it comes from something with any sense of tonal dissonance intentional or not.

Anyways, I love games made by insane people. I love games made by teams who feel like they wanna make something work or say something so bad. I love that energy, especially when invested into something that could easily rest on its laurels or which obviously won't be taken seriously. I love this in a lot of classic campy 2000s games, I love this in insanely niche yet passionate fanworks, and I love it in the Kirby series and its writing. Can we please stop talking about it like it's an annoyance or complete joke?

#shut the heck up#kirby#kirby lore#fandom#midnight rambles#im quite talkative today cause my rambling bestie is busy#im also bitter cause im too burnt out to make the things i want to properly express my adoration for this series#but i can waffle about it ig#ive been relying on prose and essay ro express myself a lot in leiu of my usual creative outlets...#i always wanted to make a video edsay series about kirby lore with this expressed ethos#maybe i should just start with essay-essays somewhere#still need to replay all the games for that first though#more streams coming up eventually i swear#tag talking#i read a cool analytical article today that had the same tone as a video essay and i was like 'ah thats the origin of the essay part'#so now i wanna explore that world more of article game and media journalism and such

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I've said this and many variations countless times before, but just a reminder:

responding to fandom analysis posts of a show with "haha or it's just bad writing 🤣", "wow the writers must have written this by accident because they're bad 😛", or "wow one interesting thing managed to happen despite how bad the writing is 😆" is... grating.

I get it. You don't like the show, and no matter what happens in it, you'll never change your opinion of that. So why are you even interacting with analysis posts? What do you get out of it if you think literally everything in this show is written by accident? Why do you think the OPs of these posts want to hear about how much you don't care and don't want to even try to engage with it at all?

Make your own post. And tag it with the appropriate salt tags so I can blacklist.

#''it's bad writing'' as a knee-jerk reaction reply to literally any post ever discussing literally anything that happens in the show at all#is just...... i don't get it. do you think you sound analytical? that it makes you sound smart to be so negative?#that by completely refusing to analyze or engage w the text at all it makes you better than it?#it's nothing. you're saying nothing. you're making no points at all. just watch something else. engage in a different fandom.#get Fs on your lit essays. leave me out of it. lol#ml fandom salt#like you can criticize the writing all you want on your OWN POST but... c'mon... this isn't even criticism...#it's just an echo chamber of Nothing

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Deciding to write my analytical paper for my english class on She-Ra (spop) season 5 and religious trauma. My (probably unreadable) bullet point list of things i could talk about so far:

Visual:

wearing all white

Dialogue:

"rejoice"

refering to everyone as brother/sister

Plot/Other Elements:

"Baptism"

purification, purity, perfection

Conquistador (missionary + invasion)

Omnipotence, all-seeing

also planning on touching on the relevenance of queerness + religious trauma, too.

It's been a while since i've watched it though plus i'm really bad at noticing symbolism (like, really really bad. even obvious stuff. the only reason i recognized all this was bc someone else pointed it out)(woohoo neurodiverse). So anyways, anyone else have anything to add on

#unityrain.txt#spop#shera#she ra#she ra spop#she ra and the princesses of power#queer#religious trauma#horde prime#analysis#analytical essay

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a lot of feelings about Benedikt's grief in the first bit of Our Violent Ends and how he deals with it/how it affects his relationships with other people, but I don't know how to put it eloquently so I'll sum it up by saying I want that shit injected into my veins

#p.s. the way roma describes benedikt screaming when he realizes marshall is dead haunts my thoughts every day#these violent delights#our violent ends#secret shanghai#chloe gong#benedikt montagov#marshall seo#roma montagov#alisa montagova#im tagging those three bc it involves them too#should i bust out a multi thousand word analytical essay like i did for kerch + ghezenism + the van ecks#perhaps#but not now#anyway#benmars

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

BS Analysis no. 1: “Tarkus” as an Allegory for the Vietnam War

TW: Mentions of warfare and imperialism

Hello beloved progblr, today I am back with my first BS analysis, which is going to be on Emerson, Lake, and Palmer’s (ELP) 1971 prog epic “Tarkus”. For the unfamiliar, this is what I do on my blog: I primarily write essays analyzing progressive rock, or writing fan essays. Occasionally, I’ll make some shitposts and reblog cool shit, but if you like stupidly in-depth analyses on prog bands that reached their peak in popularity 50 years ago or stupid fan theories about those same bands, then you’ll like it here!

Now, for those unfamiliar with ELP (which I can’t imagine there are very many of you, as this is a prog blog), I’ll do my best to explain, however they aren’t my very favorite band, (I like them a lot, obviously, but I’m still kinda new to them) so if I make any mistakes, let me know! Emerson, Lake, and Palmer (more commonly called ELP) was basically prog’s first supergroup: all three members came from other bands prior to forming ELP in 1970. The only reason why I’m bringing this up is because their prior work, specifically Emerson’s (with The Nice) and Lake’s (with King Crimson), are going to be relevant in this essay.

Tarkus is the second album released by the group in 1971, following the live debut of the group in 1970, and the whirlwind success of their eponymous debut album released that same year. The album begins with a ~20 minute long Level Two Prog Epic, and one of the first prog epics, also titled “Tarkus”. This epic is what I’ll be focusing on, and is divided into 7 sub-sections, each with their own title:

i. “Eruption”,

ii. “Stones of Years”,

iii. “Iconoclast”,

iv. “Mass”,

vi. “Battlefield”,

and vii. “Aquatarkus”.

This helps to organize the events of “Tarkus” into something resembling a plot structure. Now, “Tarkus” (the song) doesn’t really have a plot itself, however, the inside cover of the album suggests something of a plot. Notably, the cover of the album contains an armadillo on tank treads, with the inside of the cover also containing a manticore and some sort of mechanized pterodactyl being destroyed by Tarkus (the creature). There are also several scenes depicting this plot: there is a volcano eruption out of which Tarkus is hatched (“Eruption”), a depiction of Tarkus destroying several animals, and then a scene depicting the Manticore challenging Tarkus, then a scene depicting the Manticore injuring Tarkus, causing it to retreat back into the water (“Aquatarkus”). Clearly, Tarkus is not meant to be the hero of the story: it is depicted as going on a rampage against innocent creatures, only to be stopped by the Manticore (side note: when ELP created their own label, they called it Manticore). On the surface, it appears to be a sci-fi/fantasy song about an evil creature, forged by fire, that is eventually quelled by an unlikely, organic hero, and forced to retreat. Sound familiar? An evil, mechanized creature that goes around, subjugating smaller creatures, until it is eventually forced to withdraw by an unlikely hero?

From the illustrations, one can infer that Tarkus is meant to symbolize the United States and their imperialist actions in Southeastern Asia, and the Manticore, Vietnam. As depicted in the album artwork, Tarkus is a high-tech character (noted by the use of guns and the tank treads) that is defeated by an unlikely hero, the Manticore. Furthermore, Tarkus is based on an armadillo, an animal unique to North America, whereas the Manticore comes from Old World mythology, with similar creatures being found everywhere from Greece to East Asia. When the album was released in 1971, the U.S. was still embroiled in Vietnam, and began an operation into Cambodia, further destabilizing the region, and causing another round of protests against these actions.

"Tarkus" being an allegory for the Vietnam War is further exemplified by the lyrics, which begin after the instrumental “Eruption” section, which questions whether “the days have made you so unwise” and whether the listener “can hear anything at all”. The song goes on to criticize religious institutions during a section called “Mass”, during which the phrase “the weaver in the web that he made” is repeated several times, and finally criticizes the futility of warfare in general during “Battlefield”, during which Lake sings the lyrics “You talk of freedom/starving children fall”. Section by section, it appears that “Stones of Years” is a direct address to those in power, questioning if they have learned anything from history, and whether they care to learn, “Mass” is criticizing those in power who have got themselves into a situation they cannot back out of without damaging their already ruined reputations, and “Battlefield” talks of the horrors of war. If the lyrics recorded on the studio version weren’t enough proof, when ELP performed the “Tarkus” epic live, they would often include “Epitaph” by King Crimson, which was written while Lake was still in King Crimson, in the “Battlefield” section. “Epitaph” is also an anti-war protest song that criticizes the leadership of humanity, with lyrics that state: “The fate of all mankind, I see/Is in/The hands of fools”, a pretty harrowing addition to the piece.

Speaking of careers before ELP, during his work with The Nice, Emerson was involved in an incident during The Nice’s performance at the Royal Albert Hall during their cover of “America” from West Side Story involving the American flag being defaced in some way. According to Jay Keister and Jeremy L. Smith in their work “Musical Ambition, Cultural Accreditation and the Nasty Side of Progressive Rock” (2008), he “repeatedly stabbed an American flag and burnt it onstage,” whereas according to Emerson himself, he only set light to it, and it was only an image of the American flag that was burnt without being stabbed. However, The Nice did intend for “America” to be “the world’s first instrumental protest song." Either way, The Nice did this intentionally while the American ambassador was present, leading to Emerson and The Nice receiving a lifetime ban from the venue (later revoked). In the aforementioned article as well, the authors also believe that “Tarkus” was indeed meant to be a protest piece due to Emerson's previous actions, as well as the actual content of the song and album.

When looked at holistically, it becomes evident that what appears to be a peculiar piece of progressive rock with a rather quirky cover of an armadillo on tank tracks is actually a defiant statement against the horrific actions taken by the US military in the name of “freedom”. Was ELP alone in making such statements during the late 1960s and early 1970s? Not at all, many artists protested against the Vietnam War in the form of songs. However, what makes "Tarkus" stand out is that it's meant to be digested as a package: without the album illustrations, the song becomes a lot more vague and unconnected, however without the song, "Tarkus" is merely the creature on the cover of the album, without any further depth.

I feel that one thing that people tend to forget about progressive rock, in general, is that it's never simply just music about wizards and shit. All these long suites and epics portray something deeper than just their plots, and that is especially poignant for something like "Tarkus" to get the respect it deserves.

.

.

.

If anyone is interested, please look up that paper I mentioned! It’s an excellent, short read. The interview in which Emerson gives his perspective on the Royal Albert Hall incident is here, around 11:31 to 12:23.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

dustfinger spends 90% of his life seeing how close to getting his ass beat he can get without actually getting hurt and guessing wrong almost every time

#hes only vaguely right wrt mo#meggie coming into the workshop asking why mo won't read to her and mo's like#looking at his paper knives and thinking really hard lmfao#if i collect all the times he goes 'what are you gonna do stab me' do y'all want that#i have so many actually good analytical posts to share but i cant decide which one to post so i dont post any#i probably have an essay already ready to go on any character any topic so if you have a request lmk#inkheart#dumbass lomfl#says kenna#dustfinger#this is the third ans final time im editing my phrasing shhhhh#and

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's so disappointing that i can't read korean. i would love SO much to look around and see if korean orv fans have any good essays on the work but I DON'T SPEAK THE LANGUAGEEEEE

#narrates#orv#this is so sad i BET theres such good essays. i BET.#but unfortunately i am stuck solely with like. me and the six other english speaking orv fans who like writing analytic posts

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very funny thing to me is my only IRL trekkie fan friend (who is an OG watched-it-as-a-kid-with-his-dad-whos-also-an-OG-trekkie and has rewatched multiple times) keeps being SHOCKED by how fast I am not only powering through TNG, but how rapidly and more in-depth my knowledge of the characters and their backgrounds has outpaced his.

And I'm just sitting here waiting for him to put 2 and 2 together and realize... It's bc I read the fanfics and he doesn't 🤣

Like we watched S07E03 "Interface" together the other day and he goes "Oh man I forgot Geordi's parents were also Starfleet." And immediately I'm like "Yeah he's a legacy. His mom's a captain and his dad's a doctor." And I could just feel him squinting at me in disbelief like how the fuck do you know that, but I didn't have the heart to tell him it was because of a fic where Data meets Geordi's parents when they tell them they're engaged.

#Like sure its smut but also it's like reading dozens of in depth analytical essays on the characters#heh in depth#daforge#star trek tng

145 notes

·

View notes