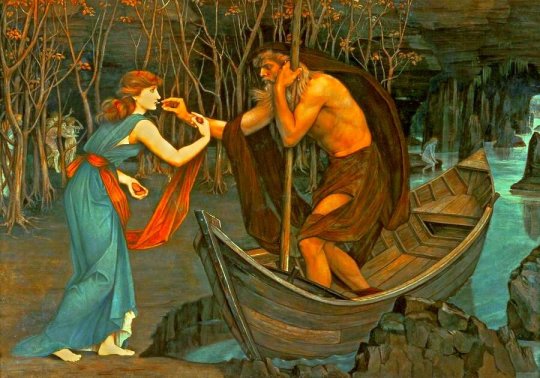

#athenian bride

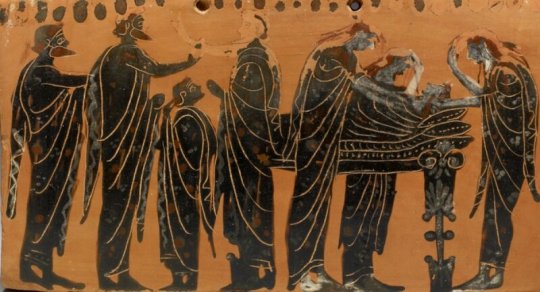

Photo

The Athenian bride.

Photo by Michael Pappas.

#greece#europe#historical fashion#traditional dress#traditional clothing#folk clothing#folk dress#folk costumes#traditional costumes#fashion#old#athenian bride#athens#attica#sterea hellas#central greece#mainland#greek culture

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dissecting ancient Greek wedding customs (or “How to adapt the clusterfuck they are into something somewhat doable for the 21st century”)

This post is going to be a bit different. I could stick to writing about the customs we know of from a purely historical perspective, and while it would be informative, it wouldn’t reflect what I’ve actually been up to. Some of you might already know, but I’m getting married, so I approached this topic with the intent of seeing what I could do (and get away with).

So this post is going to be more about method and the practical challenges that come with doing the groundwork of adapting very old (and often outdated) traditions in a way that makes sense for our modern times.

I do have some disclaimers to make before I get started:

Most (if not all) of the literature around ancient Greek marriage is hetero-normative. However, this does NOT mean that marriage rites shouldn’t be adapted for queer marriages or that queer marriages can’t be done within Hellenic paganism. It’s our job as reconstructionists and revivalists to rework and adapt to our needs.

Similarly, this post is bound to mention or detail cult practices that are no longer in line with our modern sensibilities. I also want to make it clear that this post is not a tutorial. I’m not saying how things should be done, I’m only exposing elements that I consider reworkable and propose suggestions so that it can help others make their own research and decisions, with the level of historicity that they deem fit.

While the wedding customs from fifth century BC Athens are decently known, the ones from other cities and regions of Greece are much more obscure outside of anecdotal and fragmentary details (with the exception of Sparta). For this reason, the Athenian example is what I’ll be using as foundation. If you reconstruct practices from other areas of the Greek World, you might find something valuable in this article: The Greek Wedding Outside of Athens and Sparta: The Evidence from Ancient Texts by Katia Margariti.

Basic/simplified structure

The typical Athenian wedding would spread over three days, and be marked by several steps, some of which are listed below. Note that the order of these steps is not precisely known and might have been flexible:

Pre-wedding:

Decorating: korythale at the door, decoration of the nuptial bedroom

The Proteleia

Filling of the loutrophoros

Wedding day

Nuptial bath

Adornment of the bride

Wedding Feast

Hymenaios

Anakalypteria

Nymphagogia

Katachysmata

Day after

Epaulia

Gamelia

Final sacrifices

Some of these steps included specific customs and traditions, not all of which are reconstructible for various reasons.

Decorations

The korythale: the korythale was a sprig, usually from an olive tree (or laurel), which was placed at the groom’s door (and perhaps the bride’s too). The word in interpreted as deriving from “koros” and “thallein”, which would translate “youth-blossom”.

The korythale is very reminiscent of the eiresione, which was a similar kind of branch of laurel used during the Thargelia and/or the Pyanepsia that had apotropaic purposes. Athenian weddings included a procession from the bride’s home to the groom’s house, so the presence of the korythale at the doors would indicate that a wedding was taking place involving the decorated homes.

While I haven’t seen any one make this interpretation, I would still be tempted to argue that decorating the thresholds of houses has a similar protective and luck-bringing purpose than the eiresione, which was also hung above the door of Athenian houses.

The thalamos (nuptial bedroom): While there is no doubt the houses were properly decorated for the occasion, we have mention of special care given to the nuptial bedroom.

It’s important to understand that the procession from the bride’s house to the groom’s went up to the bedroom door, it was generally an important location and its preparation is seen represented on ancient pottery. Euripides mentions the adornment of the bed with fine fabrics, while Theocritus mentions the smell of myrrh (sacred to Aphrodite). There is also evidence that, in the Imperial period, the practice of hanging curtains to create a canopy above the bed was adopted, very likely from Egypt.

When it comes to adapting this today, it is pretty straightforward and there is plenty of room for personalization. The korythale could be challenging depending on how easily available olive or laurel are in your area. I would also argue that the custom could be more loosely adapted so that instead of being at the houses’ doors, it could take the form of a floral arrangement at the door of whatever venue you are using.

Proteleia

In short, the proteleia refers to sacrifices and offerings that would be made to various gods before the wedding. The exact timing of these is more or less unknown, but we have reasons to believe they could be done a day or a few days before the wedding, and perhaps also on the day of the wedding. These offerings were made independently by each family.

It is in this context that the offering of a lock of hair and of childhood items is best known for brides. The recipients of the offerings are varied: In Athens the most mentioned are the Nymphs and Artemis, but various sacrifices to Aphrodite, Hera, Athena and Zeus were also performed. In other parts of Greece, pre-nuptial customs often included sacrifices to local heroines. Plutarch, in the 2nd century AD (and therefore way after the focus of this post) mentions the main five nuptial deities to be Zeus Teleios, Hera Teleia, Aphrodite, Peitho and Artemis.

Today, I believe the exact choice of who to offer to and what to offer very much comes down to personal preferences and circumstances. While we assume that both families made prenuptial sacrifices, we know very little of the groom’s side of things, since the focus was on the bride, and the rite of passage aspect was not present for the groom in Ancient times. This is a gap that leaves room for modern innovation eg. including Apollon to either replace or accompany Artemis or choosing a group of deities that is more couple-centric rather than family-centric.

Personally, I have settled on Aphrodite, Hera and Artemis and have integrated a Spartan custom that includes the mother of the bride in the sacrifice to Aphrodite. Hera Teleia will receive a lock of my current hair, while Artemis will receive a lock of hair from my first haircut as a child (that my mother has kept all these years), alongside some other trinkets. The groom will honour Zeus Teleios in a passive way. And I will honour the Nymphs through the the rite I will explain next.

Nuptial baths

Both bride and groom had a ritual bath before the wedding. Its purpose was of cleansing and purificatory nature, and is consistent with other water-based pre-sacrifice purifications. What made the bride and groom's baths distinctive was their preparation. The bath water used to be drawn at a specific spring or river. At Athens, the water for bridal baths came from the Enneakrounos, the fountain house for the spring Kallirrhoe, but each city had its dedicated source. The water was carried in a special vase named the loutrophoros (bathcarrier) and the act of fetching the water and bringing it back to the homes constituted a procession. The loutrophoros was often given as offering to the altar of the Nymphs after the wedding. It was an important symbol of marriage, to the point that, if a woman died before being married, she would often be buried with a loutrophoros.

This will be more or less difficult to adapt depending on circumstances and environment, but the logic of a purifying bath (or shower even) can be kept (though I would discourage bathing in water you are not sure of the cleanliness of). The idea of having a specific vessel can also be kept. Personally, I plan to have a special vessel for some type of purified water, and while I may not bathe in it, I plan to sprinkle it and/or wash my hands with it.

Adornment of the bride (and groom)

Traditionally, the bride would have a nympheutria (which we could equate as a bridesmaid, but seems to have often been a female relative) charged of helping the bride get ready. I won’t get into the details of the clothing we know about, mostly because there seems to be a lot of variation, and because I consider this to be a very personal choice. However, we can note that both groom and bride were adorned with a wreath or a garland of plants that were considered to have powers appropriate for the occasion (sesame, mint, plants that were generally considered fertile or aphrodisiac). Perfume is also something attested for both bride and groom, especially the scent of myrrh. The bride would wear a crown, the stephane, which could be made out of metal or be vegetal (the stephane is now the object of its own crowning ceremony in Greek Orthodox weddings). The bride’s shoes were also particular for the event, and named nymphides. The bride’s veil was placed above the crown.

Hymenaios and Feast

I am grouping these two since they are linked. The feast was more or less the peak of the wedding ceremony and lively with music and dances, as Plutarch indicates (Moralia, [Quaest. conv.] 666f-67a):

But a wedding feast is given away by the loud cries of the Hymenaios and the torch and the pipes, things that Homer says are admired and watched even by women who stand at their doors.

The hymenaios was a sung hymn in honour of the couple and the wedding, and there were other songs that were specifically sung at weddings. However the hymenaios wasn’t only for the feast, these songs would be sung also during the processions. The hymenaios also had the purpose of ritually blessing the couple, a ritual that bore the name of makarismos.

As for the feast, it was obviously abundant with food and the prenuptial sacrifices provided the meat that would be served. There is otherwise very little difference with what a modern wedding feast would be like: food, drink, music and dance around which gathered friends and relatives of the couple. Like today, the wedding cake(s) was an important part of the celebration. It was called sesame and consisted of sesame seeds, ground and mixed with honey and formed into cakes to be shared with the guests.

Anakalypteria

Note that there is a bit of a debate around this step, which is the unveiling of the bride. Some believe the bride kept her face veiled until this part of the wedding, where her face would be uncovered for the groom to see. Others interpret this step the other way around, where the bride is then veiled as a result of being now married. The timing of the unveiling is also up for the debate. It might have been during the feast (at nightfall), or after once the couple was escorted to the bridal chamber. There doesn’t seem to be a clear consensus.

The concept of unveiling the bride is otherwise something that isn’t unknown to us as a modern audience. As with everything else, how to interpret and modernize it is up to personal preference.

Nymphagogia and Katachysmata

The nymphagogia aka the act of “leading the bride to her new home” took place at night, likely after the feast. It is at this point that the groom ritually led the bride to his home by taking her by the wrist in a ritual gesture known as χεῖρ’ ἐπὶ καρπῷ (cheir’ epi karpo). The relatives and friends of the couple formed a festive procession that accompanied them to their new home accompanied by music and songs. The mother of the bride led the procession carrying lit torches, while the groom’s mother awaited for the new couple in their home, also bearing lit torches.

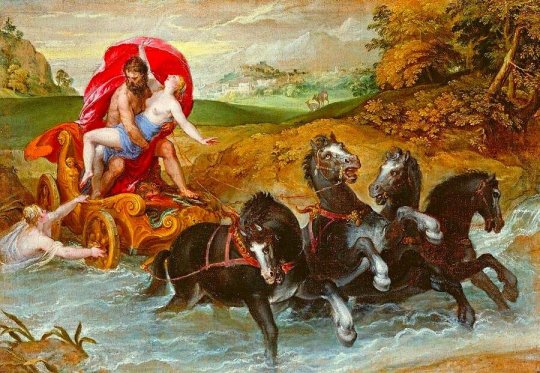

Once there, the rite of the katachysmata would happen. The couple would be sat near the hearth and the guests would pour dried fruits, figs and nuts over the bride and groom as a way to incorporate them into the household and bless the union with prosperity and fertility. As part of this rite, the bride ate a fruit (either an apple, quince or pomegranate). It is only after this step that the couple would be escorted to the bridal chamber.

These two rites are tricky to adapt in a modern context because of how location-specific they are (and that’s not even taking into account the implications of having family escort you to your bedroom etc). My take would be that the katachysmata is not too far off from the custom of throwing rice/flowers at the couple after the ceremony, and could probably be incorporated as such. The torches could also be replaced by any source of light placed in a meaningful location, depending on the where the wedding is being held. The nymphagogia could also do with an update, the easiest of which could simply be holding hands while leaving the wedding ceremony.

The day after (Epaulia, Gamelia & sacrifice)

The epaulia refers to wedding gifts to the couple, which would be given the day following the ceremony. At this point, it is implied that the couple has consummated their marriage and are officially newly-weds. Pausanias informs us that the term “epaulia” (also?) refers to the gifts brought by the bride’s father in particular and included the dowry.

After the epaulia, the bride's incorporation into her husband's house was complete. This might have been when the groom held a feast for his phratria (aka direct family), as a way to conclude the wedding.

As for final sacrifices, the bride herself may have marked the end of her wedding by dedicating her loutrophoros at the sanctuary of Nymphe, south of the Acropolis.

The epaulia could be adapted, in modern terms, with having a registry. Should someone choose to have a specific vessel linked to the ritual bath today, it could very well be kept, dedicated to the Nymphs and used as a small shrine. Considering how symbolic the object is, there is also room for it to become a piece of family heirloom.

Final words

This is really only a small summary of what a wedding could have looked like, sprinkled with a few ideas of how to manage the gaps, discrepancies and limitations. As I said in my introductions, there are details I haven’t mentioned. Some of the customs detailed here have clear modern counterparts, but others don’t. I’d like to conclude by addressing these.

First, the ancient Greek (Athenian) wedding is completely devoid of priestly participation. It was entirely planned, organized and led by the two families. Religious responsibilities were entirely self-managed. I find this point important to remember because it makes it much more accessible than if modern Hellenic pagans had to seek out an external authority.

Some of you might have noticed the absence of wedding vows, at least in a formal form like the one we are used to in our modern days (derived from Christian and Jewish traditions), this is not an oversight, there simply were none that we know of. As a sidenote, I would also advise against turning a wedding vow into a formal oath. I’m still debating on what to do myself, but I’m leaning towards a religiously non-binding vow that won’t curse me should things go wrong.

Adapting the structures and rites of the ancient wedding to today’s framework of ceremony will naturally lead to changing the order of things, on top of sacrificing elements for the sake of simplicity, practicality, personal preferences and, very likely, visibility. Unless you’re lucky enough to do a private elopement, chances are that relatives and friends might be there, and not all might know or even approve of your faith. I hope this post shows that there can be ways to include traditional religious elements that will go unnoticed to the untrained eye, like I hope it showed that the private nature of the ancient Greek wedding rites is a significant advantage for modernization.

#hellenic polytheism#hellenic paganism#hellenic pagan#heradeity#greek history#ancient greece#zeus deity#aphrodite deity#artemis deity#hellenic reconstructionism#wedding rites

752 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok i wrote an entire essay on this for class but i keep thinking about it and i really need to get off my chest how utterly devastating it is that antigone truly is doomed by the narrative.

a lot of academics look at her story as an example of athenian literature which opposes the normative gender ideology of their society because antigone is a woman inserting herself into a political sphere with no conventional place for women, especially as it was often held in athenian society that obedience to men was a feminine virtue, which antigone directly subverts by not only standing against creon but doing so publicly.

but, antigone's actions were driven by her will to adhere to the social norm of surviving women in a family performing funerary rites for the deceased men. this isn't really touched upon in sophocles from what i remember, but antigone isn't just determined to complete polynices' funerary rites because he's her brother—the completion of these rites was a position normally held by women of a family, and the responsibilities of daughters to their families wasn't considered extinguished by marriage or any such thing, so even if antigone had been married to haimon by this point the responsibility still would have fallen to her—but she would have felt a duty imposed by the societal norms placed upon women to honour polynices. this therefore obviously creates a conflict — on one hand (μὲν) society expects her to honour her brother's funerary rights, but on the other hand (δὲ) if she does so she's not only publicly disobeying a male authority figure but in a way which threatens to prevent her from marrying and preserving her family line, which was also considered a daughter's responsibility.

in choosing to disobey creon, antigone has been rendered useless as a bride in his eyes, because this rejection of the status quo has resulted in her trespass of the societal boundaries of her gender and she's therefore no longer considered able to serve the expectations of women, so creon declares that she's to die. but if she hadn't disobeyed him, socially she's still failed to uphold the familial responsibilities demanded of her following the normative gender ideology, and so even if no one would have spoken up directly about it because she's followed creon's command, either by wilful perception or subconscious judgment she likely would have been seen as a traitor to her family on some level regardless.

what this means is that not only is antigone truly doomed by the narrative, where her choices render her a servant to social expectations of women whether she outright defies authority or unwillingly defies her womanly responsibilities, but that her entire narrative is ingrained with the very gender ideology that dooms her to begin with.

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way in which Aphrodite was worshipped at her numerous cult sites throughout Athens and Attica was often personal and intimate, and thus gives us a sense of how Aphrodite figured in the lives of the average Athenians. What develops is a picture of Aphrodite's worship as highly integrated in Athenian society. The common theme in her worship was unification: between brides and grooms, between prostitutes and customers, and between the Attic demes, or townships. City officials and local merchants sought Aphrodite's aid in creating harmony in the workplace and throughout society. The goddess was associated with a number of personifications that represented various types of good fortune, harmony, and prosperity; all who worshipped her benefited from their blessings as well. As a result, Aphrodite contributed to the overall well-being of Athens.

- Worshipping Aphrodite: Art and Cult in Classical Athens by Rachel Rosenzweig

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

“With the consolidation of private property and the father-family, not only the matriarchy but the fratriarchy fell in ruins. The mothers' brothers, abandoning their sisters, became the fathers of their own families and the owners of their own property. This left women with no male allies; they were completely at the mercy of the new social forces unleashed by property-based patriarchal society.

How women felt about this can be gleaned from a passage in the Arabian Kamil, cited by Robertson Smith. He calls it "a very instructive passage as to the position of married women."

"Never let sister praise brother of hers; never let daughter bewail a father's death;

For they have brought her where she is no longer a free woman, and they have banished her to the farthest ends of the earth."

(Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia, p. 94, emphasis in the original)

In reality women were not banished to the ends of the earth; they were on the contrary cloistered in the private households of their husbands, to serve their needs and bear their legal sons. But to women who were once so free and independent this must indeed have seemed like the end of the world.

With the advent of slavery, which marks the first stage of civilized class society, the degradation of women was completed. Formerly exchanged for cattle, they were now reduced to the chatteldom of domestic servitude and procreative functions. The Roman jurists’ definition of the term "family" is a clear expression of this:

Famulus means a household slave and familia signifies the totality of slaves belonging to one individual. Even in the time of Gaius the familia, id est patrimonium (that is, the inheritance) was bequeathed by will. The expression was invented by the Romans to describe a new social organism, the head of which had under him wife and children and a number of slaves, under Roman paternal power, with power of life and death over them all. (Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, p. 68)

The downfall of women brought about a sharp reversal in their "value" as wives. In place of the bride price, the payment made by a husband to secure a wife, we now come upon the dowry. "The Athenians," says Briffault, "offered a dowry as an inducement for men to marry their daughters, and the whole transaction of Greek marriage centered around that dowry" (The Mothers, vol. II, p. 337).

Tylor, one of the few anthropologists to notice this reversal, found it an "interesting problem in the history of law" to account for this curious transposition of bride price into dowry (Anthropology, p. 248). But the law was merely a reflection of the new social reality. Once women lost their place in productive, social, and cultural life, their worth sank along with their former esteem. Where formerly the man paid the price for a valuable wife, now the dependent wife paid the price to secure a husband and provider.

How women felt about this humiliation heaped upon degradation is recorded in Euripides' drama, where Medea mourns:

"Ay, of all living and of all reasoning things

Are women the most miserable race;

Who first must needs buy a husband at great price,

To take him then for owner of our lives."

Even this was not all. After reducing women to economic dependency and to merely procreative functions, the men of early civilized society declared that women were only incidental even in childbearing. No sooner was the paternal line of descent fixed by law than men began to claim that the father alone created the child. According to Briffault, Greek thinkers in the classical period viewed the mother's womb as "but a suitable receptacle"—a bag—for the child; the mother was subsequently its nurse, but "the father was, strictly speaking, the sole progenitor" (The Mothers, vol. I, p. 405). Lippert writes that, while "no historian has turned his attention" to this subject, the evidence shows that matrilineal descent gave way to "the opposite extreme," which he describes this way:

She who for untold thousands of years had been the pillar of the history of young mankind now became a weak vessel devoid of a will of her own. No longer did she manage her husband's household; these services were forgotten in a slave state. She was merely an apparatus, not as yet replaced by another invention, for the propagation of the race, a receptacle for the homunculus. (Evolution of Culture, pp. 355, 358)

This idea that men alone created children indicates that even at this late date, the beginning of civilization, men were still ignorant of the facts about reproduction. Whatever vague speculations they engaged in on the subject, genetic fatherhood had played no part in the victory of the father-family and patriarchal power. Men had won on the basis of their private ownership of property. It was not biology but the Roman law that laid down the dictum patria potestas—"all power to the father." And, as Briffault's description shows, property was the father of this patriarchal legality.

The patriarchal principle, the legal provision by which the man transmits his property to his son, was evidently an innovation of the "patricians," that is, of the partisans of the patriarchal order, the wealthy, the owners of property. They disintegrated the primitive mother-clan by forming patriarchal families, which they "led out of" the clan - "familiam ducere." The patricians set up the paternal rule of descent, and regarded the father, and not the mother, as the basis of kinship -"patres ciere possunt." (The Mothers, vol. I, p. 428)”

-Evelyn Reed, Woman’s Evolution: From Matriarchal Clan to Patriarchal Family

#evelyn reed#patriarchy#women as property#human history#female oppression#male entitlement#history of fathers

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Young women have always been for sale. In the fifth century bc, Herodotus describes the practice of selling Babylonian daughters at a yearly auction in his Histories. He wrote:

They used to collect all the young women who were old enough to be married and take the whole lot of them all at once to a certain place. A crowd of men would form a circle around them there. An auctioneer would get each of the women to stand up one by one, and he would put her up for sale. He used to start with the most attractive girl there, and then, once she had fetched a good price and been bought, he would go on to auction the next most attractive one. They were being sold to be wives, not slaves. All the well-off Babylonian men who wanted wives would outbid one another to buy the good-looking young women, while the commoners who wanted wives and were not interested in good looks used to end up with some money as well as the less attractive women.

The Babylonian men paid a bride price, but some of their money would come back to them because the young women were given dowries, which their husbands would administer even if they could not raid it. This exchange seems odd but was not so unusual in the classical world, where women served to cement together two male-controlled families. If a married daughter died without children, her money would go back to her family, which removed any incentive to harm her.

At the time, virginity was not always necessary to a girl’s successful marriage—the Lydians prostituted their daughters to raise money for their dowries. Because of the dangers of childbirth and high rate of early mortality in ancient Greece, it was common for wealthy relatives to provide not just their daughters but also their poor relations with dowries. Athenian law even required that the State dower poor women of just passable attractiveness; teeth were all that were required. Because Athens was under constant threat from its rivals, it depended on its young women to provide it with a constant stream of new soldiers.

Classical literature is filled with accounts of creative daughter disposal. In some memorable verses of The Odyssey, the father of Penelope, Odysseus’ wife, then thought to be a widow, urges her to marry the suitor with the most gifts. Greek fathers took care not to raise more daughters than they could dower. Outright infanticide was abhorrent to ancient Greeks, but they did practice “exposure,” wherein parents intentionally left unwanted infants exposed to the elements. They believed that the gods could choose to save the abandoned children, thereby eliminating their agency while achieving their aims. Husbands were not permitted to run through their wives’ dowries but neither could the wife.

A Greek woman’s dowry yielded about 18 percent per year, and if the couple got divorced, either party could request the dowry. It was returned to a woman’s guardian or, in certain cases, kept by the husband, who paid 18 percent interest to his former wife’s guardian for her support. The wealthier the family, the more likely it was that a marriage would take place between two young first cousins. Such marriages keep money in one family and tended to correlate with periods of cultural instability, when power was held by a few important families. Cousin marriage was particularly popular among the higher echelons in Elizabethan England, the Antebellum South, and in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain.

Greek girls who died in childhood were mourned specifically because they did not fulfill their destiny as wives and mothers. Their epitaphs make reference to their failure to marry, and the girls were quickly writ into myth. Like Persephone before them, they were considered married to Hades and dwelled, as wraiths, in the underworld.

In the Roman period, women did not fare better. Catullus sums up the Roman attitude toward marriage, writing, “If, when [a young woman] is ripe for marriage, she enters into wedlock, she is ever dearer to her husband and less hateful to her parents.”

The middle class continued to sell their daughters at regional markets throughout most European countries during the Middle Ages. For the upper middle classes, the social stasis of the period made marrying an heiress one of the only means to improve one’s social status, and it was nearly impossible to do without deception. The middle classes began to consult marriage brokers—a growing cottage industry in Europe—who would help them plot their rise, reconstruct their family histories, then help them relocate in order to achieve success in another part of the country. If a woman did marry up, she would find that she had much less control over both her body and her daily life—where she walked and even what she ate—than she had in a middle-class environment. In the upper classes, the legitimacy of heirs continued to be of primary importance, and as such women’s movements were intensely regulated.

Women were progressively more visible during the Renaissance. Increased trade created a new culture of conspicuous consumption, propped up by merchants and explorers who transported new goods through Genoa and Venice, Zanzibar and Constantinople, outward to European capitals and the known world. Newly available luxury goods made life easier and more enjoyable—tobacco, tea, coffee, silks, and spices facilitated a culture of male comfort in which wives and daughters played an important though entirely passive role. In ancient Greece and Rome women were kept mostly in the home, but during the Renaissance men put their velvet-swaddled wives and daughters on display, trotting them out in public, where they would often sit separately, saying little if anything but fulfilling a necessary decorative function. A woman’s beauty, or wealth, was most of all a statement about the social status of her presiding male, be he husband, father, or brother.

For much of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, sumptuary laws on food and goods defined and limited social space. By legislating who could obtain specific fabrics, foods, drink, and other luxuries, governments prevented servants and the middle classes from masquerading as aristocrats by denying them access to the materials necessary to appear richer than they were. Pre-Reformation Europeans were just beginning to let go of feudal social organization.

Though more people now lived in cities, family patriarchs had long made decisions for their large clans and were not interested in giving up a privilege that had served them so well. Daughters were married to create important and lasting connections between families. Those who could not be married off in a way that would benefit the clan were often forced into nunneries. For a noble family, sending a daughter to a convent or forcing her into spinsterhood was far preferable to tainting a family line by permitting her to marry beneath her station.

This system of dispensing with daughters worked peaceably for hundreds of years, until Henry VIII came to need a son and heir. When his attempts to have his first marriage, which had produced no sons, annulled by the pope failed, Henry charged ecclesiastical and secular legal scholars in England with finding a way to divorce his consort Catherine and marry his pregnant mistress Anne Boleyn. Their solution was divorce and breaking away from the Catholic Church. Henry began the violent dissolution of Catholic monasteries in 1536. It lasted for four years, during which the crown plundered church lands, sold them off to rich allies, and used the surplus cash to wage dubious wars in France. For wealthy young women, newly Anglican, there was an additional change, perhaps the single most significant social change women would see until suffrage. Their safe haven—the convent—was now gone.

The absence of nunneries sent numerous marriageable aristocratic young women into circulation. When once they would have been in the country, awaiting the marriages arranged for them, or preparing to enter a convent, these young girls were now brought to court, which is where they were most likely to find husbands. By the time Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I began her reign in 1558, the atmosphere surrounding marriage had a new urgency.

Elizabeth’s rule began in religious chaos after her predecessor, her half sister Mary, violently restored Roman Catholicism to England. Elizabeth spent the better part of her first years on the throne fighting for her father’s Protestantism in an effort to fend off those who wished to depose her. Her legitimacy was questioned with every decision she made, and she understood that her courtiers were her key to maintaining the throne. She tightened her control over the aristocracy by reducing its size to a new low. She stripped disloyal aristocrats of their titles or made it known they were not welcome at court.

It was against this tumultuous backdrop that Elizabeth, in an effort to form beneficial social and political alliances, began having young ladies ceremonially presented to her at court. These presentations were small affairs and limited to the daughters of Elizabeth’s most important courtiers. They took place in the queen’s “withdrawing room,” a private room, but located next to larger public rooms, where she could go with a smaller party. The girls were led from a public stateroom into the smaller adjoining room at Hampton Court palace, so that other courtiers would know who was being favored.

At the more private ceremony of presentation, the young girls curtsied to the queen. The young girls had a vivid experience of being watched and assessed, enhanced by the fact that of the roughly 1,500 people in regular attendance at court, only fifty were women. These presentations came to be referred to as “drawing rooms,” and they engendered a curious experience that blended ostentatious display with the familial and private, a mix that would continue to characterize the debutante ritual for its duration

Many of the presented young women served her as attendants and became intermediaries between Elizabeth and the wider circle of her court. They helped Elizabeth to exert control over the nobility by creating an elegant buffer between the monarch and her courtiers. In order to present a petition to the queen, one first gave it to a lady-in-waiting, along with a fee that the lady in question would determine based on her closeness with the queen. Elizabeth encouraged her ladies to charge exorbitantly for this service—not so much because they’d have some independence, but so they would have enough money to be able to gamble with her.

She also regularly rejected petitions based on their lack of generosity toward her ladies. The queen could also be capricious—Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting could not marry of their own volition. Elizabeth Vernon spent a week in prison (with her new husband the Earl of Southampton) for marrying without the queen’s permission. Lettice Knollys was banished permanently for marrying Elizabeth’s favorite courtier, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. When Elizabeth discovered that another lady-in-waiting, Mary Shelton, was secretly married, she attacked her and broke her finger.

Elizabeth’s social standards and rituals persisted after her death, with queens taking over control of drawing rooms and social presentations even when there was a king on the throne. Elizabethan presentations-at-court served a very clear political purpose. Though they bore little resemblance to the feverish social theater that characterized the fully developed debutante ritual of the nineteenth century, these court presentations provided the foundation for modern debutante culture and served, too, as its myth of origin.

They show the important link between society and politics, a symbiotic relationship that only deepened as the ritual became institutionalized and spread outward to all corners of the British Empire. Elizabeth’s backroom maneuvers—quick conferences with her ladies or political advisers—provided the precedent for the many political meetings that took place at debutante parties in later centuries, and emphasized the soft power of social settings, which were controlled by women who understood that the way to power was not always hard work or even fortunate birth, but judicious conversation next to a sloshing punch bowl or quivering trifle.

The Stuart monarchs who followed Elizabeth continued the tradition of the drawing room (“with” was dropped from “withdrawing room” in the late seventeenth century), which retained its function as a matchmaking tool. Elizabeth’s successor, James I, arranged the marriage of his favorite courtier, the charming spendthrift James Hay, to Honoria Denny by granting Honoria’s reluctant father a title and royal patent. While these high-level marriages took strategy, marriage law remained chaotic. There was no legislation that defined marriage, and there were no protections for women after they were married. Rather, the absence of law meant that women might be forced into marriage by their fathers, married by capture, or tricked into marriage.

The age of consent to marriage was twelve for women and fourteen for men, and contracts were often made during the “unripe years.” It was a particularly dangerous time to be an heiress. During these years women could inherit property. Inheritance law was not clear on whether her property would become her husband’s upon marriage. Without knowing if they could control their property, many women resisted marriage.

Restrictive regulations for daughters intensified after they were wives, especially if they were considered to have broken proper codes of behavior. If a wife were to be convicted of adultery, she would lose her dowry or marriage portion and her husband could make a good case that she could punitively lose her property as well. There was no comparable financial forfeiture for adulterous men, and courts habitually disbelieved women who tried to defend themselves against claims of adultery. It is not difficult to explain widespread female acquiescence.”

- Kristen Richardson, “Marriage (Market Price).”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

my Classical Athenian history professor who just talked shit about Xenophon for the last 30 minutes: I gotta hand it to him, though. He may be a horrible historian, but at least he's against child brides :)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

greek mythology au! sakusa x reader

SAKUSA AS THESEUS, retelling of theseus and the minotaur, original myth is changed to fit my narrative, mentions of death (the minotaur eats people!!), mentions of child marriage (ancient greece was sick), flirty and charming sakusa, hero!sakusa, 2.5k words.

the flowers were blooming early this year, speckles of color in the fields of green behind your small home. a sign of good fortune, the prophets of apollo had proclaimed, hard work will certainly be highly rewarded; the year of the bull. you grit your teeth and pulled harder, the weeds pestering your small garden uprooted entirely, their evil roots still gripping the flecks of soil that had nurtured them.

with deep reverence, you send a prayer to demeter, thanking her for an early spring.

sweat beaded at your hairline, curtesy of helios and his mighty chariot brining light to the sky overhead. it was just before noon now, with the sun directly overhead. collecting the clump of weeds you had uprooted, along with a few parcels of lavender, your feet carry you away from the forrestline and back to shelter.

inside your home lived your younger sister and father, your mother residing in the realm of hades after king minos had sent his navy to decimate athens. unlike most men in greece, your father was an honorable man, and his heart thumped only for his two daughters. though you were a girl, you were his eldest, and therefore his most prized possession in all of his lifetime. you were worth more than gold, in his eyes, more than any ore or meat or plant or man could offer. his pride and joy, a title you wore with honor.

lost in your thoughts, a series of screams tore you from your revere, the cries of your father to let her go, please! take me instead!

you hadn't thought twice before your feet carried you up the hill, powerful legs pumped full of adrenaline that pushed you to the forefront of your small home.

six cretan soldiers stood in the doorway, you could spot their royal purple linens from miles out. in their hands was your sister, tears spurting from her eyes like palace faucets, her arm contorted unnaturally under the pressure of the soldier's hands.

"let her go." you demanded, eyes aflame, "she is my sister, not a sacrifice. i suggest you find another family to tear apart."

you had thought your distance from the main city would protect your family, but the evil of minos extends everywhere, you suppose. once a year, fourteen athenian children are sent as sacrifices to feed the minotaur living under the cretan palace floors, trapped in a maze designed by the world's greatest engineer. there was no point to it, really, other than a cruel display of power, a boast to the world that one man could bring the great city of athens to its knees.

it was cruel, you know. to try and gift tragedy to another family, as if it were bread at a dinner table. but you would welcome the selfishness, just this once, if it meant preserving your sister's life.

"king minos was clear in his decree," the biggest one smiles down at you, his soul more rotten than his brown teeth, "seven girls and seven boys. your sister makes the last sacrifice. though, i wouldn't mind having her as my bride."

the soldiers laugh at his comment, their greedy eyes hungrily taking in your sisters figure. she visibly trembled under their touch, fear falling from her in waves.

you and her were different in that regard, the brutality of the world forging stubbornness and bravery in the chasms of your heart, instead of the petrefying fear that plagues your sister. you were not afraid of the world; you would burn it with your bare hands. if it meant preserving her smile, you'd destroy the earth ten times over; you'd set olympus aflame.

she's so young, too young, and terribly afraid of the world, not fully understanding what it means to be a woman or the shackles that come with marriage and children. she's already lost so much.

you clench your hands, stepping forward, muscles tense not from fear but from anger. poised, one might call it, in the way a mountain lion stalks its prey, ready to strike at even the smallest of openings.

"you will not touch her," you spit, harsh enough that the soldiers were unnerved, just for moment, "you will take me instead."

women were not protectors, you had been told, they are homemakers. gentle, subservient creatures to serve as vessels in aiding the next generation in conquering the world. you were no such thing. you were headstrong and unshakable, stubborn in a way that made men hate you, and you would protect what was left of your family with everything in you.

"it makes no difference to me," another soldier grinned again, wider and more terrible than the last, "you'll be dead before the end of the week."

in a quick exchange, your sisters life had been swapped for yours, the mark of death transferred to your head. you father wailed and hiccuped, you sister torn between shouting thanks and mourning her living sister; her only sister.

with the courage of a roman gladiator, you offer a warm smile to your father, and a gentle nod to your sister. it's okay, the crinkle of your eyes told them, take care of each other. don't forget to say your prayers. there's bread and cheese out on the table. don't forget to put it up after dinner.

with a rough yank, the band of soldiers marched you from your childhood home and down the way to the athenian port. there was no fear in your heart, you'd realized, only pride. your sister was safe and taken care of. the cretan solders never took from the same houses.

chin held high, you would sail from your home in athens to a foreign grave, and you wore your crown of death with pride. a bruise of honor.

as you approached the dock, you saw that there were more cretan soldiers than just the six escorting you, as there were at least forty more aboard the massive cretan ship and scattered around the port.

there, you saw the other sacrifices, six other girls and seven boys, perfectly lined by the shore, shackled to each other and teary-eyed. the youngest child was easily six or seven years of age, distraught and confused as to what was happening; to what would eventually become of his delicate life. with a sudden shove, you were pushed in line with them, the unexpected force knocking you on your knees. you feel skin break, exposing the soft tissue underneath, warm blood pinpricking the fabric of your lose clothing.

rough hands grip you by your shoulders, and you quickly lift your head to spit in the face of your assaulter. it lands right underneath his eye, and satisfactions burns in your stomach at the way it oozes down his cheek. cretian scum.

"almost. i'd say an inch higher and you would have really blinded me."

you blink away the haze of your hatred and take in his appearance. normal clothing, athenian features, metal shackles binding him to the other children down the shoreline. he was a sacrifice, you realized, and you had spit on him. his grip was so strong, you had thought he was one of the soldiers for sure.

but he was just a boy, easily the eldest of the athenian scarifies, but a boy nonetheless.

"i'm sorry," you rush to apologize, "i reacted too quickly. i thought you were a soldier."

his hands were rough to the touch, but gentle in nature, as he carefully helped you stand back to your feet, "it's quite alright," he wipes the glob of spit from his cheek, "if anything, i'm impressed by your aim."

at this you smile, "my sister taught me. she's the worst."

the stranger laughed, tall and broad-shouldered, but still soft in the face in the way all boys are. his clothes were dirty, his hands and feet shackled, but his skin glowed in a way that could only be described as divine.

the athenian people were distinct in their features, and there were no new faces in a city you've resided in for a lifetime, so who was this strange man, offering himself as an athenian sacrifice? athenian by blood but foreign otherwise.

"who are you?" you suddenly ask, speaking lowly as not to be heard by the patrolling cretan soldiers, "in all my years in athens, i have never met you, foreigner. you are not from here."

"well, i have never seen you before," he presses, "why is it that i am the foreigner and you are not?"

his quick remark catches you off guard, and you search for a witty response, "because i have lived in the heart of the city my whole life. i would have remembered a face such as yours." that damn glow.

the implication of your words are not lost on him. he wants to tease you, take your mind away from the metal around your wrists. "why?" he asks, "because you find me handsome?"

"because you are different," your face burns at his accusation, "you are unlike any man i have known."

"i thought i was a stranger," he says, "now you claim to know me?"

"i know enough," you huff, eyes pressing him for more information, "call it intuition." he smiles and you're heart nearly stops. you avert your eyes.

"i lived in the outskirts," he reveals, more serious, "as a fisherman. rarely did i ever find myself in the city."

you accept his answer, considering for a moment. the fishermen really only came to the city to sell their catches. it's likely that he simply sent a younger brother or apprentice to sell what he caught. strange, but anything was possible.

"why are you here then, if you aren't in the city often? and you are too old to be an ideal sacrifice."

"you have a brilliant mind, princess." he continues, noting your observance, "i was on my way to the palace steps, when i saw a few soldiers dragging a boy away from his mother. i traded myself in place of him."

you're at a loss for words. sure, you had done the same, but it was for blood, your only sister. this man, this foreigner, had traded his life for a stranger's, and still has the heart to joke and laugh about.

"i did the same," you say, "for my sister."

"i thought she was the worst?" he asks.

"she is," you confirm, "but she's still my sister and i am still hers."

it's quiet for a moment, your ears only catching the sound of poseidon's mighty waves folding against the shoreline. this would be the last time you see these waters, hear the ocean surrounding your motherland.

"it's honorable," he speaks suddenly, snapping you from your daze, "to trade her place for yours. to ultimately decide that her life was worth more." he turns to you, curiosity and adoration lighting his face, "what is your name? your bravery moves me."

"yours first." it isn't a question.

his eye catch yours and something like lighting flashed within them, offering a sly smile as if you'd solved his riddle, "i am kiyoomi, son of king aegus, and i have come to destroy that which ails my people."

laughter finds you easily, bubbling from your throat in dry chuckles, "athens does not have anyone to inherit the throne," your eyes narrow into slits, "and king aegus certainly does not have a son. why lie, with such little time to live?"

"you were right to say i was different from other men," he smiles, "but it makes no difference whether you chose to believe me. you will see soon enough."

his vagueness baits you, "see what? what are you planning? we will sail to crete and die under the palace like the multitude of athenian children before us. it has been the same story for years; there is no other ending."

"we will sail to crete, yes," he says, "but no more blood will be shed at the hands of that beast. i will kill the minotaur and return to athens as crown prince," he turns to look at you, "then athens will be free."

"how do you plan to kill the minotaur? you'd have to find him before he finds you in his maze of tunnels."

"you ask a lot of questions, princess," he chides, "and i'll forever be sorry that i cannot give you all of the details, but please, rest assured that my plan will come to fruition. athena is on my side, the battle already won. the fates have already declared it centuries ago."

the wind whispers comforts to his ears, that can be the only reasoning for the calmness that shrouds him. his inky hair curls gently at the movement. you want to believe him, and a small part of you does. he is different; perhaps there is some truth in his tale. you're touched by his declarations, the fires of his determination. he reminds you of yourself.

"my name is y/n, daughter of y/f/n," you say, and his eyes crinkle happily at the sound of your name, "and my father was a blacksmith. i am no princess."

"you will be." kiyoomi says, certain, "when you return from crete as my bride."

you flush at his flirtation, your body betraying you, "did the fates tell you this, too?" you snap.

"no," he says cooly, "i decided it when you spat in my eye with the precision of an archer. surely, there is no other woman for me."

"again, you have my sister to thank for that."

"i most certainly will," he clarifies, "when she dances at our wedding."

and with the blow of a horn, the fourteen of you are escorted onto the foreign ship, with the promise of death on the other side of the ocean.

you smile down to yourself, the metal binding your wrists feeling less heavy, less permeant. perhaps he is who he says he is: the son of a king, in the lineage of a god. maybe he can save athens. maybe he can save you. regardless, you have little else to lose; why not play into his tale?

"slay the minotaur," you say, placing one footing front of the other, "before you even think of asking for my hand."

"please," he playfully scoffs ahead of you, "at least give me a challenge. you're as good as mine now."

take this as my apology for disappearing :((( i fell out of love with writing, but i'm slowly gaining it back. i have some drafts i want to put out soon but this is my favorite :))) i hope u don't hate me im so sorry

#sakusa drabbles#sakusa kiyoomi#sakusa x reader#kiyoomi#kiyoomi sakusa#msby sakusa#sakusa drabble#sakusa#sakusa fluff#haikyuu kiyoomi#haikyuu

287 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm curious about the ancient greek burial rites you draw on in your comics, like Pallas being buried as a child bride and her displeasure with it, to Erigone and her grief, and that makes me wonder how were women buried back then? I tried to search but I only keep finding about how it was expected for women to arrange the funerals but not how they themselves were buried, can you point me to some sources please?

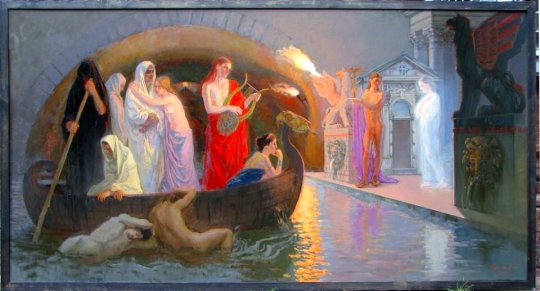

The Greek Way of Death by Robert Garland has a chapter about funeral practices. There doesn't seem to have been much difference between men's and women's burials. The body of the dead person was washed, clothed and laid out on a bed (and like you say, this was usually done by the women of the household). This part of the funeral was called prothesis.

"The funeral garment worn by the deceased in Geometric prothesis is represented as a long ankle-length robe. Later we hear of the corpse being wrapped in a shroud (endyma), supplemented by a looser covering known as an epiblêma." The usual color of the shroud was white. It was also a widespread custom to place a crown on the head of the deceased. According to Plutarch, this crown was most commonly made of celery, but in some fourth-century and Hellenistic Athenian burials wreaths of gold have been found. "Women's hair was arranged as in life, and women are sometimes shown wearing earrings and a necklace."

However, Garland mentions that certain categories of the dead were especially attired for the prothesis. For instance, the unmarried or recently married dead were laid out in wedding attire. That was my inspiration for Pallas being dressed as a child bride, even though we don't know if this was a tradition already among the Mycenaeans.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I turn at last to the gods situated in and around the house. From various allusions in the Homeric Hymns—not of course in the main Athenian texts— we learn that Hestia has ‘an everlasting seat’ in ‘the middle’ of the house of every mortal, and receives the first and last libation at every banquet; like her friend Hermes she ‘lives in the fair houses’ of men. Early in the fifth century the East Locrians still spoke of a household or family as a hearth. The hearth remained the symbolic centre of the Athenian household, to which new members of all types were in different ways introduced. Brides (but also grooms) and newly bought slaves were led to it, made to sit, and greeted with a shower of light foodstuffs such as nuts and figs ‘as a symbol of prosperity’; children were informally acknowledged a few days after birth at the Amphidromia, which took its name from an act of ‘running around’ the hearth. Offerings to Hestia were in theory shared only among members of the household, if we may trust the explanation offered of the proverb ‘he’s sacrificing to Hestia’, which meant ‘you’ll get nothing from him’. The dying Alcestis in Euripides entrusts her children to the charge of Hestia in a moving prayer. … The wife of the exiled general Phocion prayed to ‘dear hearth’ and laid beside it the remains of her husband, brought home at last from Megara. Hestia, the fixed centre, can be seen as a symbol of the oikos’ continuity over time. The child is born of a mother presented to the hearth, and is presented to the hearth itself; the boy child eventually leads a bride ‘from her paternal hearth’ to his own and begets a child to perpetuate the process, the girl child eventually goes out to another hearth in exchange. …

Hestia sat in the seclusion of the oikos, like the women who guarded its property, and may have been seen as stewardess of its riches. (She bears that title, though in a public context, in Hellenistic Cos. But the power explicitly associated with the wealth of the household was a different god, Zeus Ktesios. ‘If the property of a house is destroyed, it may be replaced, by grace of Zeus Ktesios, says the Argive king in Aeschylus’ Supplices (443–4); rage seizes me, says a character in Menander, ‘when I see a parasite entering the women’s quarters, and Zeus Ktesios not keeping the storeroom locked, and little whores running in’. Zeus Ktesios was concerned, therefore, both with the acquisition of property and with its preservation, in that storeroom where his own image was set. A typical prayer to him was ‘to grant health and prosperous acquisition/ ownership’. … One of the rare surviving fragments of exegetical literature concerns his cult: ‘This is how to set us symbols of Zeus Ktesios’. What follows is corrupt in detail, but the main action certainly concerned a new two-handled jar with a lid, which was to be hung with white wool and filled with a mixture, known as ‘ambrosia’, of pure water, olive oil and ‘all fruits’. Pots were sometimes used, perhaps as foundation offerings, to ‘set up’ statues, but it looks as if the jars of Zeus Ktesios were themselves the tokens of the god’s presence, the only ones apart perhaps from small altars. If so, Zeus Ktesios was within the means of any household. …

Zeus Herkeios is more complicated. Every candidate for an archonship at Athens was asked ‘if he had an Apollo Patroos and a Zeus Herkeios, and where these shrines were’. Every citizen—or at least every citizen from the higher property classes—had therefore an association of some kind with Zeus Herkeios. The herkos is the wall or fence that surrounded the external courtyard of the Homeric house—and by extension the courtyard itself—and we regularly find an altar located there in the Homeric poems and in myths which reflect that world (above all that of the death of Priam). … Possibly the cult of Zeus Herkeios, like that of Apollo Patroos, was attached to the larger kinship groups, phratry or genos (or even to the deme)—as the obscure expression ‘gennetai of Apollo Patroos and Zeus Herkeios’ might suggest. (This would not preclude individual altars in the courtyards of prosperous households.) However this may be, we have a clear item of evidence that for the Athenians Zeus Herkeios was not merely a form of Zeus located conveniently close to hand (as he may appear to be in Homer), nor merely a guardian of the physical space of the household, but specifically associated with the social ties holding together the close family. ‘Whether she is my sister’s child or closer in blood than the whole (family linked by) Zeus Herkeios, she and her sister shall not escape a dreadful death’, says Sophocles’ Creon, terribly, of his niece Antigone. Demaratus’ appeal to his mother by Zeus Herkeios to tell the truth about his birth implies something similar.

In the porch of many Athenian houses stood some among three further gods. Apollo Aguieus is familiar to readers of drama, but the physical form in which he was manifested is controversial. An ‘Aguieus’ was, according to lexicographers, a ‘pillar ending in a post’, a ‘conical pillar’. But some ancients believed that these pillars were ‘proper to the Dorians’ and that the Athenians had altars instead: in Harpocration’s words, ‘the Aguieus mentioned by Attic authors must be the altars in front of the houses mentioned by Kratinos and Menander and Sophocles in the Laokoon, where he says, transferring Athenian customs to Troy, The aguieus altar gleams with fire, steaming with drops of myrrh, perfumes of the barbarians.’ Certainly, it is not strictly demonstrated that the Attic Aguieus was a pointed column, of the kind that can be seen on the coins of (for instance) Megara and Apollonia. But greetings such as ‘lord Aguieus, neighbour, guardian of my front door’, common in tragedy and comedy, imply the presence of an emblem of the god, not an altar alone. …

A comic oracle in Aristophanes declares that one day every one of the litigious Athenians will have a little private law court outside his porch ‘like a Hecataeum everywhere in front of the doors’. Small Hecataea have been found in Attica in good numbers, though perhaps few if any antedate the Hellenistic period. Almost all take the form of the ‘triple-bodied Hecate’ round a pillar, an iconographical type said by Pausanias (whom archaeology has not refuted) to have been invented by Alcamenes in the second half of the fifth century ‘for the Hekate Epipurgidia of the Athenian acropolis’. … How frequent Hecataea may have been we do not know. We can apply to them the usefully vague expression applied by Thucydides to the last of the doorstep gods, the ‘stone herms of native, four-cornered form’: of these, he said, there stood in the city of Athens ‘many, both outside private houses and in shrines’. …

The main household gods have now been reviewed. Hestia is the oikos itself, its permanence; Zeus Ktesios its wealth; Zeus Herkeios (wherever precisely located) the bond of kinship. The gods of the porch have something to do with the transition from the private space of the house to the public world. Hermes promises safe journeys (though he may also have some connection with the material prosperity of the house); Apollo and Hecate are probably there as protectors from intrusive evil. Hecate was herself an ambiguous figure, and by planting her as a protectress at the threshold one perhaps insisted that she did not enter the house. It was no amiable trait in Euripides’ Medea to have a Hecate who ‘lives in the recesses of my hearth’, actually within the house."

- Polytheism and Society at Athens by Robert Parker

#greek gods#hestia#zeus#apollon#apollo#hermes#hekate#hecate#ancient greek religion#ancestral gods#household gods#ancient athens#excerpts#quotes

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Τα μεν γαρ άλλα δεύτερα αν πάσχη γυνή, ανδρός δ’ αμαρτάνουσα, αμαρτάνει βίου.*

- Euripides

*Other misfortunes are secondary for a woman, but if she loses her husband, she loses her life.

Queen Anne-Marie of Greece is the widow of the late King Constantine II of Greece, who reigned from 1964 until 1973. She was born Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark on 30 August 1946.

Anne-Marie is the youngest daughter of King Frederick IX of Denmark and his wife Ingrid of Sweden. She is the youngest sister of the reigning Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and cousin of the reigning King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

In 1961, she spent a year at an English boarding school in Switzerland - the Chatelard School for Girls. In 1963, to improve her French, Queen Anne-Marie attended a Swiss finishing school, 'Le Mesnil', until the Spring of 1964. She also speaks Greek, English and of course Danish.

Queen Anne-Marie first met King Constantine of Greece as a young girl in 1959, when he visited Copenhagen on a journey to Sweden and Norway, as Crown Prince, with his parents, King Paul I and Queen Frederica.

She met him again in Denmark in 1961. He had declared to his parents that he intended to marry her.

On 14 May, 1962, Crown Prince Constantine's elder sister, Princess Sophia, married the Spanish Prince Juan Carlos in a double ceremony in Athens at the Roman Catholic Cathedral and the Orthodox Cathedral.

More than 100 royal guests came to Athens, and Princess Anne-Marie was a bridesmaid. Queen Frederica of Greece recorded that, at the reception, her son Crown Prince Constantine 'would dance only with Anne-Marie'.

In 1963, centenary celebrations of the Greek Royal Family began with a State Visit from Princess Anne-Marie's parents, King Frederick and Queen Ingrid of Denmark.

In March 1964, King Paul I died after a short illness, and Constantine succeeded him to the Greek throne.

King Constantine came to the throne with much goodwill, which was expressed in abundance when, on 18 September 1964 (six months after his accession) he married his beautiful Danish Princess in what was described at the time, as 'the most radiant of Athenian royal weddings'. Even an old republican, the 76 year old Prime Minister, George Papandreou, was seen to be enjoying himself thoroughly with the bride and bridegroom.

Queen Anne-Marie devoted much of her time as Queen of Greece to 'Her Majesty's Fund'. This was a charitable foundation started by her mother-in-law, Queen Frederica. It helped people in rural areas of Greece and supported crafts such as embroidery and weaving. She also worked closely with the Red Cross, and various charities.

On 21 April, 1967, political problems in Athens intensified with the Colonel's coup. A month later, Queen Anne-Marie gave birth to Crown Prince Pavlos at the family's country estate, Tatoi.

In December, after his attempt to restore democracy failed, King Constantine and his family left Greece from Kavalla for Rome. With the King, the Queen and the two children were King Constantine's mother, Queen Frederica and his younger sister Princess Irene. They landed at a military airport in Italy because they were running out of fuel.

Queen Anne-Marie and her family stayed first at the Greek Embassy in Rome for 2 months and then took a house at Olgiata on the outskirts of the city.

Later in 1968, they moved to 13, Via di Porta Latina - where they lived until 1973. On 1 October 1969, Queen Anne-Marie gave birth to Prince Nikolaos in the Villa Claudia Clinic near her home in Rome.

In 1974, Queen Anne-Marie moved with King Constantine to England, after a brief stay with her mother in Denmark. King Constantine had been officially deposed by the military Government on 1 June 1973 and a Republic declared by colonel Papadopoulos.

The family's first home was in Chobham in Surrey. Then they moved to a house in Hampstead in North London, where they have lived ever since. Queen Anne-Marie calls it her 'Home away from home'.

Queen Anne-Marie's family grew larger with the birth of Princess Theodora at St. Mary's Hospital, Paddington, in London on 9 June 1983, and Prince Philippos on 26 April 1986.

Queen Anne-Marie helped to start this remarkable bilingual educational initiative in 1980. She is now Honorary Chairman of the school, and devotes a lot of her time to it.

Her first visit to Greece since she left with her family in 1967, was for a few hours, for the funeral of King Constantine's mother, Queen Frederica, in 1981.

Queen Frederica died suddenly in Madrid. Her wish had been to be buried beside her husband, King Paul, at the family estate at Tatoi. The family was given permission to attend - but could not spend a night in their country. They landed at a little airfield near Tatoi, and were welcomed by large crowds. It was, for Queen Anne-Marie and her family, a moving and sad occasion.

She visited Greece again with King Constantine and her family on a private visit by sea in 1993. They went, 'Not knowing what to expect. Wherever we went, people came out to greet us. It was extraordinary and very moving'. It was the first visit for her younger children.

In 2013, The Greek government allowed the ex-monarch to come back to Greece. Constantine returned to reside in Greece. He and his wife Anne-Marie purchased a villa in Porto Cheli, Peloponnese, residing there until they relocated to Athens in the spring of 2022

Wherever they were in the world, Queen Anne-Marie was a constant source of support and stability not just for her exiled husband but also their five children. She made sure that the family spoke Greek at home with all her children learning to be fluent.

She was the one also the family retained close links with all the royal families of Europe - and particularly with the British, Spanish and Danish Royal Families.

Queen Anne-Marie's father, King Frederik IX of Denmark was an accomplished musician and she has inherited his love of classical music - Beethoven, Bach, Tchaikowsky, Wagner. She has always been fascinated by historical biographies.

She had been, above all, the greatest support to her husband over many years of change. They had been happily married for 58 years until the King Constantine II died on 10th January 2023. She remains the last Queen of Greece.

#euripides#greek#classical#quote#wife#husband#marriage#royalty#greece#queen anne-marie#denmark#king constantine II#monarchy#history

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Khoes! On this second day of Anthesteria the Athenians celebrated a ritual marriage of Dionysus and the Anthesteria Queen, possibly in homage to Dionysus and Ariadne. I’m no scholar and I can’t vouch for the veracity of anything, but I love the idea of celebrating my favorite divine couple! Let’s have a toast to Dionysus and his lovely bride!

#hellenic devotion#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic reconstructionism#helpol#hellenic paganism#hellenic polytheist#hellenic gods#hellenic community#prayer#dionysus worship#ariadne#hellenic worship

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since the thought of ancient Athenian play Dracula wouldn’t leave me alone...

It is a lovely spring day in Athens and the citizens are heading - just as they were yesterday, just as they will tomorrow - towards the Theatre of Dionysos. The sun is bright in the sky and the playwright’s frowning at it - he’d been hoping for overcast, looming clouds, but it’s a beatiful spring day by the Mediterranean and a group of respectable Athenian citizens are preparing for the first play of the day’s trilogy.

The play opens and we are introduced to Jonathan, a young man of good family about to embark on a business journey to the Barbaric North. He’s receiving the final instructions from his father, the letter of introduction to their family’s contact, the local prince, who has apparently expressed an interest in establishing stronger trade connections with Athens - and we meet Mina, Jonathan’s bride-to-be, respectfully veiled and offering her bethrothed well-wishes and blessings as a priestess initiated in the mysteries of Athena herself.

We meet the chorus - Scythians, singing of our friend Jonathan’s departure in cheerful tones, extolling the virtues of their wild homelands, where the mountains are tall and the woods are deep and the rivers run strong and free.

We follow Jonathan on his journey north, leaving behind civilized Athens and then leaving behind civilized Hellas entirely, journeying north and ever north. As he goes, he is accompanied by another traveller, a wandering merchant we the audience can tell is probably Hermes himself in disguise. It is from their conversations that we first hear the name Dracula, as Jonathan names the man he’s journeying to meet.

And it is the “fellow traveller’s” worried reaction that clues us in that something is wrong. He advices Jonathan to travel elsewhere, but Jonathan is a dutiful son and adamant. After all, what does he have to worry about? Xenia is a sacred bond and he’ll be arriving as a guest.

They part, Hermes gifting Jonathan a token and asking him to always keep it close.

Jonathan finally reaches the lands of the host, the Lord Dracula, commenting on the wild beauty of it, the hooting owls and howling wolves. A storm draws near, thunder and lightning crashing like drums and cymbals, and he arrives at the gates utterly soaked.

His host is a gracious man. He is, of course, a Barbarian, a Scythian, and the actor is dressed to suit, but he speaks Greek, albeit with an accent that’s played for laughs in the first scene, and he’s running to and fro, being a good host, doing everything himself, and the audience is almost wondering if there’s been a mix-up, if perhaps this is not a tragedy at all, but a play intended for the final day of the festival, the day of back to back comedies.

Except something’s off.

Slowly, gradually, it becomes clear that this Lord Dracula is the only person in his estate, and the estate itself seems neglected. He is the perfect host, but his accent seems less and less funny, his quotes of the Odyssey and Iliad start referencing ill omened events.

And then Jonathan realizes that he’s trapped. That there’s literally no way out. He’s alone with a stranger and the estate gate is locked and surrounded by flocks of slavering wolves.

(The playwright is particularly pleased with the howling - the young hunter hiding backstage has a perfect wolf imitation).

On a full moon night Jonathan decides to go exploring, braving the wolves - that seem quiet tonight - and the chorus follows, singing back and forth with him as he talks about making his way through the dark woods, tripping over roots and dropping his token, fumbling for it in vain before giving up and moving on, following an instinct - until finally, finally he arrives at a clearing where there’s light, torches and a bonfire and people.

And his host, the Lord Dracula, standing among them.

And here’s where the bit that the playwright’s particularly proud of comes, when the chorus of Scythians come forth and in a whirl of robes and a quick huddle to hide the change of masks, they transform into a chorus of wild and blood-thirsty women.

Of Amazons.

Dancing and singing like wild things around Lord Dracula, praising Ares the bloody god of war, and we get poor Jonathan, hiding in the shadows, commenting on what happens next.

The dance stops, the chorus starting a slow chant.

A woman - an Amazon - walks forward. In her arms she’s cradling an infant, tiny, wrinkled, swaddled to hide the tiny animal playing the part - and as she walks the chorus parts, until she comes to a halt before Lord Dracula, standing like the parody of a priest in front an altar.

She takes forth the “child” - a boy, we learn from Jonathan addressing the audience, and she no doubt the Amazon mother - and places it on the altar. And here comes the piece of proper grand guignol, as Lord Dracula raises his knife - and perhaps the chorus do another huddle to hide the actual kill, or perhaps they do not.

Perhaps there is the shrill shriek of a small piglet or kid dying, then abruptly cut off. Then the chorus parts and we see Dracula once more, carrying a goblet of something red. He makes a libation for the gods, praising Ares above them all, then raises the goblet to his lips.

Of course, this is the part where Jonathan can no longer keep silent, but cries out in horror - drawing the attention of the Barbarian priest - or is it Ares himself, playing at his own priesthood? - and the Amazons.

He flees off stage and they pursue. Oh, how they pursue.

We hear Jonathan’s screams off-stage as the wild women catch him.

And then a single woman walks back on stage, adjusting her martial dress in a manner implying that she’s putting it back on.

The chorus follows, singing a song of Amazons and their many conflicts with the Greeks and their heroes.

The chorus parts on the final act, and we find Jonathan awakening back at Dracula’s estate, his clothes torn. He laments, likening himself to characters like Pentheus and Orpheus, making absolutely sure through his implications that any person in the audience who didn’t catch what was happening off stage is now perfectly clear that our friend Jonathan suffered the ultimate unmanly fate at Amazonian hands.

Dracula enters - long gone is the slightly comedic foreigner of his first scenes, before us stands a warlord or possibly a god of war, in full Scythian martial dress. He reveals his plans for Jonathan’s future, to stay a captive at Dracula’s estate, for his “beloved daughters” to entertain and keep captive (there’s some heavy implications that the Amazons and the wolves are one and the same) while Dracula himself intends to journey south, to infiltrate Hellas starting with Athens itself, bringing his blood and barbarism and horror with him.

And there’s nothing Jonathan’s going to be able to do about that.

Dracula leaves and Jonathan is left guarded by a pair of spear-wielding Amazons, never left alone as the days pass. He laments, he worries for his family, his bethrothed, for the entire civilized world.

Finally, the full moon rises and the wolves howl, and he is escorted out of the estate by his two guards. The chorus arrives from the other side of the scene, some of them crawling at first before rising, many throwing wolf pelts on the ground as they sing of the first Amazon, daughter of Ares the blood handed, and how one Amazon became many.

The two guards give Jonathan a shove and he runs off stage, once more pursued by the howling women.