#but then the narration attributes it to the human within the monster

Text

excerpt from The Incredible Hulk by Peter David, based on the screenplay by Edward Norton and Zak Penn

#I like this moment between Betty and the Hulk#it’s interesting to me that Betty is screaming ‘Bruce!’#and the Hulk’s response is ‘Betty needs us calling us’#he’s not making the distinction that she’s calling out to Bruce ergo not him#the idea of ‘Bruce Banner’s smile played along the Hulk’s lips’#hmm#I don’t really like it when in the comics the Hulk makes a decision that aligns with his own moral code#but then the narration attributes it to the human within the monster#because in those moments it’s not really necessary to take that credit away from the Hulk#here they’re doing something with Bruce’s scientific knowledge that the Hulk wouldn’t have on his own#but tbh I’m reading that last bit as Betty’s bias misinterpreting something positive from the Hulk as being from Bruce#marvel#mcu#bruce banner#my posts#books

1 note

·

View note

Text

Notes

Just gonna jot down some notes for things I want to include in the Story.

World: Terran, AKA Planet O-2496, AKA New Earth.

Celestial attributes: Orbits a Binary Star System. A Red Giant and a Blue Giant orbiting each other. The planet has three moons,

Date: Undecided. Hundreds of Thousands of Years into our Future.

Calendar: 36 hours in a day, 10 days in a week, 10 weeks in a season, 4 seasons in a year.

Wildlife: Similar creatures and environments to Earth, with the exception of added monsters.

Inhabitants: Terranians. Anthropomorphic creatures. Half human, half animal. Furries.

Hybrids: A combination of two different Terranian Races, created through the use of Magic. Example: Dog/Cat, Fox/Eagle, Hampster/Frog, etc.

Chimera: An advanced form of Hybridization. Same principle, but with 3 or more Races. Sometimes dangerous/unstable. Often seen as untrustworthy. Commonly ostracized from society.

Monsters: Many different kinds of Monsters. Kobolds, Dragons, Slimes, etc. Some intelligent, some Feral.

Continents: 5 separate land masses, split up into Kingdoms by the dominating Races. Smaller Islands surround them, both inhabited and uninhabited.

Kingdoms: Ruled by a specific race. Lupine, Ursine, Vulpine, Lapine, Leonine, etc. Not all Races have a Kingdom. Some have smaller regions within a ruling race's Kingdom.

Main Character: Krystal Woods. A young Hybrid girl, Rabbit/Lion with minor shapeshifting abilities. Throughout her youth, she would shift between the male and female sexes interchangeably, before eventually settling as female. Once settled, she did not shift again for many years, eventually forgetting she even had the ability. The next time she shifts will occur near the beginning of the story, when she is in a fight. This is when she will discover that she has two different forms, passive and aggressive. When in her passive form, she has more Lapine (rabbit) features present, while in her aggressive form, she has more Leonine (lion) traits present.

Narrator: The Eternal One. An immortal being who lives in a floating castle in the sky. They are known around the globe as an amazing storyteller. Some call them the Watcher, or the Collector, because they spend their days collecting stories and observing the world, documenting what they see, and filling thousands of journals. In their castle, a massive library full of stories both Factual and fictional. The Eternal One has been alive for Eons. So long, in fact, that they don't even remember how old they are, where they came from, or what their name was. They were once the last living human. At the very center of their floating castle, is the old space station, where they and the other members of their science team lived while seeding and terraforming the planet. They found the planet after leaving the Milky Way and heading for the Andromeda Galaxy where they found what they called New Earth or Planet O-2496. created the Terranians as a way to preserve intelligence, since humanity was actively going extinct.

The extinction of the human race: The downfall began in the Earth year of 6072. At this point, humanity had spread out among the stars, colonizing many different planets throughout the galaxy. One day, an accident occurred at the warp gate of the planet Agrocier. The warp gate had a quantum detonation that blew a massive chunk out of the planet's moon, which fell to the planet's surface, making it uninhabitable. Bits and pieces of the moon still fall as meteorites to this day. Before this tragedy occurred, Agrocier was the Galaxy's largest export of food. Without its necessary resources, famine began to spread throughout the colonized planets. Because of this lack of vital resources, people began to fight each other for scraps. War was brewing, and the high council of the Galaxy assembled to find a solution. They eventually settled on a plan of randomized culling via a genetically modified disease.

The Virus: The virus that would wipe out humanity began in a lab with scientists intending to create a disease that would infect 1/3 of the population, and kill anyone it infected. Unfortunately, the virus escaped containment before it was ready, mutating and beginning to kill everyone with a 100% infection and death rate. The way the virus worked was especially malicious. It could stay in one's system for weeks without showing any symptoms, and then shut down your organs in a day, long after you had infected everyone you came into contact with. It spread like wildfire, killing billions seemingly overnight, wiping entire planets off the map in waves. A small team of scientists from Earth saw the impending extinction coming, and decided to leave, in order to create a new race of intelligent beings who would be immune to the virus.

The creation of Terran: The planet was seeded and terraformed by the scientists using plants and animals from Earth which they grew using DNA samples. The Terranians were created by splicing that same animal DNA with that of Humans, since animals (excluding that of chimps and other close relatives to humans) are immune to the virus.

The Creation of Monsters: Monsters evolved naturally on Terran as a result of the large amounts of magic emanating from the Planet's core. This is how a simple puddle of sludge could gain consciousness, how a Terranian lizard could evolve into a kobold, how a panther could evolve into a displacer beast, and how a common fly trap could become a giant man-eating plant.

Magic system on Terran and the wider universe: Magic in this future of ours can be explained through science. What is something that would be considered magical in our world today? You might not be able to think of much, but there are a few things if we take cursed objects into account. Think about an orb that any who get too close are drained of their life force, and are cursed to die a slow and painful death. Think about a cursed piece of jewelry that causes wounds that never heal. These are real things that exist in our world today. That orb is more commonly known as the Demon Core. That jewelry had paint with trace amounts of Radium in it. Curses are simply radiation. But then, so is light, and so is heat, so who's to say that magic, the kind of magic that has not been seen on Earth for centuries, is not just another type of Radiation?

The discovery of Draconium: The element that is responsible for magic in our universe was discovered in the Earth year of 2578, at the IO particle accelerator. It was discovered by Dr. Markus Draco and his team after experimentation with collisions of the heaviest of elements. The single atom that was created existed in our universe for only five seconds before decaying, and when it decayed it emitted a new kind of energy. A form of radiation never before seen, which had mysterious and strange effects on the surrounding landscape. In a ten mile radius around the facility, a new breed of never-before seen flowers began growing over everything in sight. The element was named Draconium, after the scientist who discovered it, and the energy, which was found to fit ancient descriptions of magical energy known as Mana, was name "Manalistic Radiation". It was found that this element may once have been present in Earth's core, from which the energy would radiate out, allowing people to manipulate it and shape the reality around them. This element, which could only be forged in the mightiest of star deaths would not be able to exist unless under extreme pressure constantly. while all of Earth's Draconium decayed long ago, Terran is uniquely abundant in the element, and so is the perfect place to mess with the genomes of creatures. After all, radiation is great at fucking up our DNA and creating cancers. Who's to say Manalistic radiation wouldn't be helpful in splicing the DNA of other creatures?

0 notes

Text

By the fin de siecle, literary depictions of the spider produced uneasy messages about the precise nature of arachnid horror. Spidery forms were distinctive in narratives of imperial encounter, expressing fears of invasion, concerns about the morality of colonialism, and suspicions about the alien other in the corners of empire. [...]

By the 1850s, the representation of the spider in Victorian natural history was beginning to change. No longer associated solely with ingenuity and industry, the spider took on more disturbing connotations in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Unable to pin down the creature's precise rhetorical and metaphorical function, naturalists could not decide whether the spider ought to be loved or feared [...] in popular fiction. [...] In the Gothic empire fiction of Bertram Mitford and H.G. Wells, the spider takes on the role of the harbinger of death on both sides of the colonial encounter. [...]

---

[T]he eighteenth-century spider was viewed in a positive light in natural philosophy [...]. [W]riting also praised the spider's character for its skill and creativity [...] [and] the ‘industry’ of its nest-building abilities. Celebrating its intelligence and good judgement [...], clever engineering. [...] Within a hundred years, however, the metaphorical associations of the spider had changed significantly. By the 1860s [...] its ingenuity had become cunning and the sense of industriousness had come to be seen as working against the well-being of humankind. [...] Although British spiders were relatively harmless as far as humans were concerned [...] [t]he spider took on a sinister rhetorical function, as the naturalist Philip Henry Gosse's popular Life in Its Lower, Intermediate, and Higher Forms (1857) showed. [...]

---

Conversely, children's educational literature about the natural world attempted to challenge, if not overturn, Gosse's opinion of arachnids.

G.L.M.'s Spider Spinnings, or Adventures in Insect-Land (1870), told from the perspective of a spider, constructs a fictional world in which spiders and other insects have the capacity for human feeling, while humanity is portrayed as ‘the ungainly two-legged monster called man’ and the human is a ‘treacherous and bloodthirsty monster’. In the introductory chapter the spider narrator - the significantly foreign-named Ranio - openly attacks Gosse's description of spiders in Life.

‘Even some naturalists’, he asserts indignantly, ‘who ought to know better, instead of trying to combat this absurd prejudice, have joined in the vulgar outcry against us’.

---

Yet despite Ranio's vexation, Victorian naturalists collectively agreed with Gosse and his spider theory. In 1901, for instance, Grant Allen, the Canadian-born novelist and science writer, described the grass-spider as a sly and scheming creature [...]. The spider, then, was becoming a phobic object partly because it was seen to have a merciless nature, as Gosse and Allen pointed out. Naturalists' descriptions of spiders proved them to be territorial, possessive, and intelligent in ordering their dominion, highlighting the exact attributes required to be the imperial and colonial aggressors that Mitford and Wells would later describe in their fin-de-siecle fiction. [...] Allen was also quick to point out the insalubrious features of foreign species in his description of the Brazilian spider [...]. The sheer number of species that were found to exist beyond British shores [...] was constructed as excess in much Victorian natural history. [...]

---

Traditionally, the spider has, nevertheless, been difficult to define in terms of its cultural meanings. [...] Although naturalists had to admit that there was nothing particularly frightening for humans about the British spider, when located in far-off lands, it became a compelling cultural symbol of the imperial world ‘gone wrong’ and nature working to humankind's downfall. Distinguishing between English and foreign spiders in British Spiders: An Introduction to the Aracheidae of Great Britain and Ireland (1866), E.F. Staveley argued that although spiders are ‘ferocious in their habits’, there is ‘no English species capable of inflicting on man a poisoned wound of any severity’. However, there are ‘some foreign species of which the poison is very virulent, their bite being sometimes followed by death’. Calling attention to this disparity between English spiders, which are harmless, and foreign ones, which clearly are not, reveals a tension between what is perceived to be ‘out there’ and therefore dangerous, and what is located on British shores, and therefore safe, even if this was a factual as well as conceptual difference. [...]

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the spider was imagined as domestic and alien, harmless and dangerous, intelligent and evil and these seemingly oppositional categorizations led to it becoming a [...] symbol of anxiety [...].

---

All text above by: Claire Charlotte McKechnie. “Spiders, Horror, and Animal Others in Late Victorian Empire Fiction.” Journal of Victorian Culture Volume 17, Issue 4, December 2012, pages 505-516. At: doi dot org slash 10.1080/13555502.2012.733065. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#ecology#landscape#abolition#haunted#ghost#spiders#imperial#colonial#multispecies#interspecies#tidalectics#temporality#archipelagic thinking#victorian and edwardian popular culture#insects

615 notes

·

View notes

Text

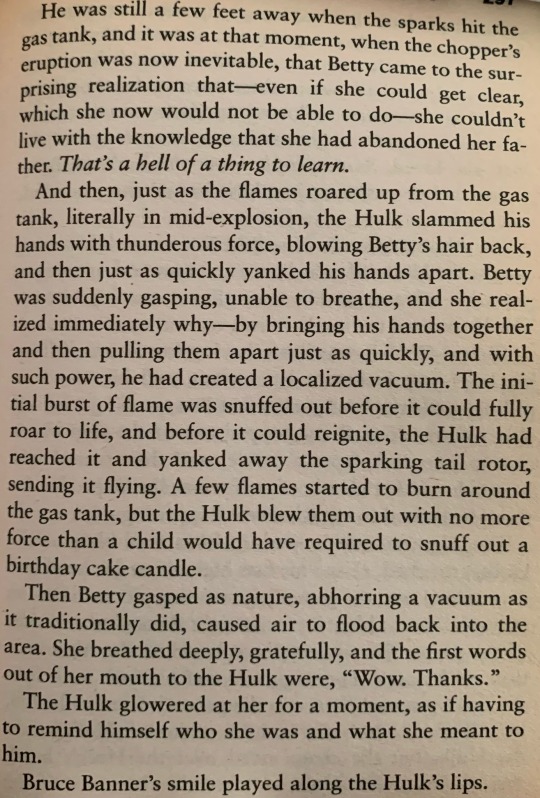

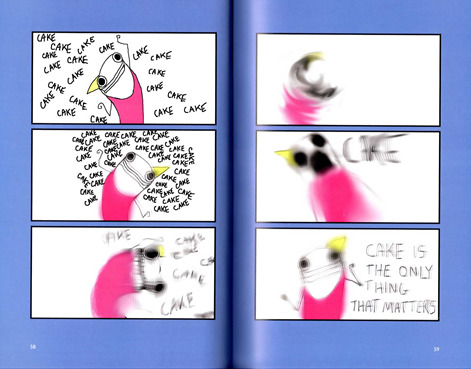

Hyperbole & A Half; Illustrated Novels as Gateways to More Traditional Comics

Hyperbole and a Half, autobiographical webcomic blog, turned illustrated novel; One! Hundred! Demons!, autobiographical comic compilation of personal “demons;” both detail the funny, heartwarming, and often ugly parts of the human experience as they unfold for each author as an individual. Both are told in short story form, with an intra-homodiagetic narrator (the author serves as both narrator and active character), accompanied by illustrated panels that invoke a sense of physical and emotional movement that the reader can easily conceptualize. With so many major similarities, why does each work receive such different classifications? What makes a comic a comic and not an illustrated novel? How do these seemingly disparate definitions affect the way we read them? Can illustrated novels be considered gateway materials to comics? I think so. Before we jump into that exact why, let’s look at the defining characteristics of comics.

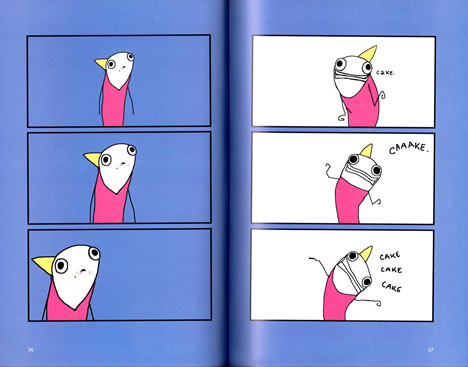

Text, images, and some semblance of sequential flow in time and space are the most major markers of comics, utilized throughout history, found in ancient work like Egyptian tomb paintings all the way up to modern comics and manga. Speech bubbles erupt from the mouths of static character images, narration is often delineated by straight-lined boxes and a change in tone, real movement through space and time happens in the empty “gutters” between panels. Although illustrated novels and comics are constructed differently, they are still processed in the brain in fundamentally the same way. Children’s literacy researcher, Evelyn Arizpe, notes that when reading illustrated stories, regardless of form (comics or traditional storybooks), “the eye moves between one part of the picture and another, piecing together the image like a puzzle.” If picture books and comics are processed in the brain in the same way, why are they considered different mediums? Linguist and cognitive scientist, Neil Cohn, applies his academic specialties to comics, attributing the difference to things like panel placement and what he calls “navigational structure,” the direction our eyes track when piecing images in a comic together to create a sense of coherence when reading.

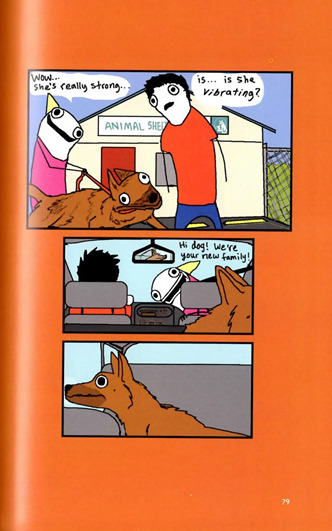

Traditional storybooks, unlike comics, typically utilize one image per page to convey everything from character relationships to arrested motion; comics achieve a more fluid and nuanced version of this by using panels as snapshots or windows into character worlds. Where then does the illustrated novel fall between these two states, and where does Hyperbole and a Half land? Illustrated novels rely more heavily on the text narrative of the story and the readers imagination, associated images usually only serve to enhance the story world or solidify ideas and images that would otherwise be difficult to conceptualize or to emphasize an exciting or emotional moment in the narrative. Hyperbole and a Half leans more heavily toward the multiple-panel style of comics to help amplify the narrative. Perhaps this stems from the novel’s genesis as a blog-turned-book. In 2009, Hyperbole and a Half author, Allie Brosh began a blog of the same name, where she chronicled events from her personal life, like the adoption of one of her two dogs; illustrated pet peeves, like the internet usage of “alot,” a misspelling of “a lot,” personified as a shaggy, fang-toothed monster; or her fear of spiders, captured by an image of an oval with spindly appendages replete with strapped-on knives, guns, and a swastika tattooed above the eyes. Brosh’s book maintains the same familiar tone, regularly interspersing images meticulously drawn by the author herself. Her use of illustrated images that convey character motion, emotional state, and even dialogue exchanges are reminiscent of both regular comics and contemporary memes.

In Brosh’s chapter titled “Motivation,” she chronicles her own struggle with self-starting and follow-through. She illustrates a frequent conversation she has between the “her” who knows she must complete a task, and the “her” who continues to procrastinate for no conceivable reason. Instead of floating thought bubbles, she makes this conversation concrete by utilizing a kind of split screen effect,where both versions of herself take up space within the same panel, as does their dialogue.

Most of Brosh’s panels behave in the same way, providing the reader with concrete examples of often abstract concepts, like internal monologue and discussions with oneself.

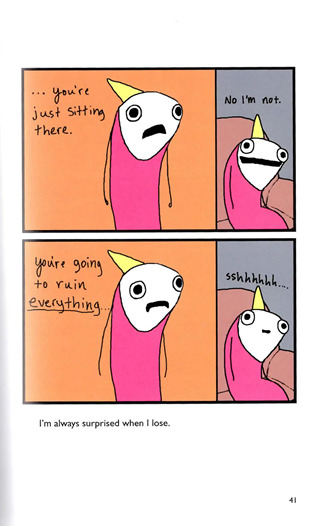

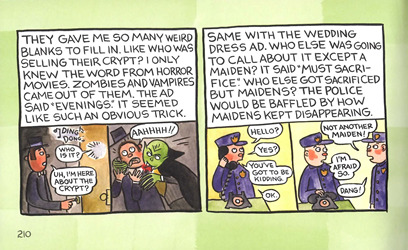

One! Hundred! Demons!author, Lynda Barry, achieves this same concept by forcefully changing the reader’s perspective. As she reveals the story of her struggle with impostor syndrome as an author and her childhood tendency to let her imagination run away with the descriptions in the Classified section of the newspaper, the reader follows her through her childhood musings and is dropped into the middle of one of her fantastical plots.

Only when Barry transitions back to a narrative focused on her own more present-tense position as a narrator do we as readers get dragged back into the present-past-tense of her childhood self.

Brosh maintains a slightly smoother sense of temporal immediacy by clumping her panels in “Motivation” together, as one “Motivation Game.” Readers are taken along the same journey, into and back out of, the author’s imagination and altered psychological state, but Barry’s follows tactics familiar to comic readers, while Brosh blurs those lines a bit for readers unused to comics.

This difference in delivery of the protagonist’s inner-world carries over into the way dialogue is associated with each character as well. In the above examples, from One! Hundred! Demons!, Barry uses the classic speech bubbles historically associated with comics; Brosh, on the other hand, utilizes both classic speech bubbles as well as free-floating text that the reader infers to be audible speech through context clues.

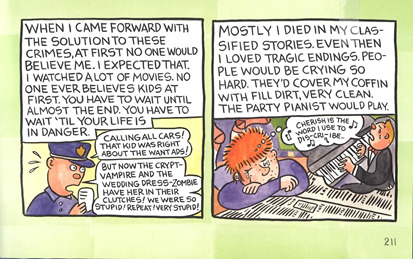

In the chapter “The Helper Dog is an Asshole,” Brosh retells the story of her and her partner’s adoption of a second issue-riddled shelter dog. She uses both dialogue vehicles on one page, in succession, the traditional speech bubbles allow each character in the top panel to convey separate thoughts, while the speech in the middle panel is only spoken by Brosh’s caricature of herself, as she is the only character “facing” the audience.

Brosh utilizes a similarly comic-style tactic when expressing active motion or a change in mental or emotional state. In “The God of Cake,” she recounts a childhood obsession with conquering her mothers demands that she not decimate her grandfather’s homemade birthday cake with her youthful inability to control her own sugar intake. She masterfully illustrates this rapid descent into the kind of one-track-minded madness only children ever master with a four-page sequence of successively blurry panels.

No, that’s not a mistake of my scanner, it’s printed that way in the book; while a little difficult to read, I think it conveys an emotional whirlwind with an immediacy that helps the reader understand just how much untamed tenacity is bubbling beneath the surface for this child character through the remainder of this chapter.

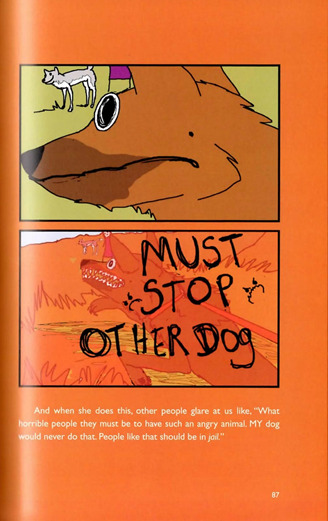

Another tactic that Brosh employs, that seems like a holdover from her work’s origin as an online blog, is her use of a colored filter over a panel to illustrate distress or another intense emotion. In the same chapter retelling her story of the “helper dog,” Brosh lists the myriad and often confounding behavior issues the new dog frequently displays, like her visceral and adverse reaction to other dogs. Brosh posits that the new dog must simply be unable to comprehend or abide by the fundamental existence of other dogs in the world. To depict the abrupt and unpredictable change in this dog’s mental state, Brosh uses a red tinted filter, along with grumpy-looking smiley faces and hand-written text over her base illustration of her new dog lunging toward another dog in the distance, teeth bared.

You can almost hear the Kill Bill sirens going off in the background.

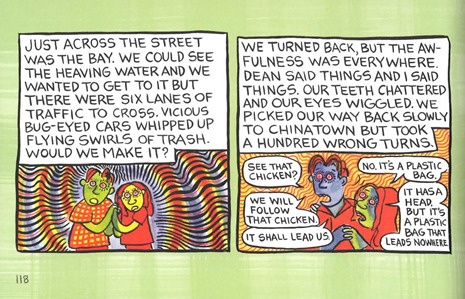

While Brosh’s artistic approach is reminiscent of internet memes, it also resembles the cartoon-y illustrated style of altered mental states in comics. In One! Hundred! Demons!, Barry juxtaposes alternating bright contrasting colors with radiating squiggly lines in a few of her panels to symbolize the acid trip she and her truncated crush are having on their roam through China Town and Skid Row.

Instead of giving the audience a sense of almost seeing through the perspective of her dog’s psyche, like Brosh does, Barry’s interpretation of her own childhood experience makes the reader feel a little like a sober friend along for the ride, understanding what’s happening, but not able to reach quite the same level of empathy.

Although comics are typically regarded as a reading material relegated to childhood hobbies, books that fall between the borders of comics and illustrated novels, like Hyperbole and a Half, prove their usefulness as a narrative medium, and for readers afraid of being seen reading a full-blown comic—or have never even attempted it, can consider them the shallow end of the comics pool, a lighter commitment than the image-heavy ocean of traditional comics.

Brosh, Allie. Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened. Gallery Books, 2019.

ISBN: 978-1-4767-6459-7

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marona’s Fantastic Tale (2019, France)

Before delving into the thick of this review, I have a few personal biases to reveal. First, I am not a “dog person”, let alone a “pet person”. I understand why people adore dogs, but I have long been uncomfortable around them – small, energetic ones especially. In addition, I tend to view the subgenre of animal movies (dogs, cats, horses, etc.) as littered with saccharine, but nevertheless watchable, dreck. Reading back those last few sentences, you may conclude that I am describing a heartless monster that should not be trusted with living things. So be it.

Anca Damian’s Marona’s Fantastic Tale, also known by its original French title L'extraordinaire Voyage de Marona, avoids the common traps of this subgenre. It, too, happens to be an animated film. Damian, a Romanian-French filmmaker, has previously only directed two animated features, both documentaries: Crulic – The Path to Beyond (2011, Romania/Poland) and The Magic Mountain (2015, Romania/Poland/France). She is, foremost, a dramatist concerned with humanist ideas and values. Damian and screenwriter Anghel Damian (her son) treat the title character – also called three other names – as maturely as any human character in this film, where other filmmakers in this subgenre might only do so superficially, to elicit obligatory “awws”. Marona’s Fantastic Tale artfully depicts the perspective of its canine star through the chapters of her life. These life chapters are laden with ambiguous resolutions and important conversations and decisions withheld from the viewer – moments where love, responsibility, and survival intertwine or clash.

The film begins with the female dog’s death. She (voiced by Lizzie Brocheré) has been hit by a car, and narrates the rest of the film, framed as a recollection of her most potent memories. Her first given name is “Nine”, as she is the last of nine puppies between a mixed-breed dog and a purebred Dogo Argentino. Nine is shortly adopted and immediately abandoned. As a stray, she is adopted by a struggling acrobat named Manole, and given the name “Ana”. Happy though their initial time together may be, Ana recognizes she is an impediment to his financial situation, and runs away. Slumbering at a construction site, she is grateful for the warmth of architect Istvan, who always brings her food. Istvan, who calls her “Sara”, eventually brings her home to his manipulative wife who abhors Sara. Lastly, our protagonist will be adopted by a little girl named Solange, who names her “Marona” (from the French word marron, meaning brown; I will refer to the protagonist by her final name for the remainder of this review). Solange’s overworked single mother and irascible grandfather oppose the impromptu adoption for differing reasons, but eventually accept the new addition to their household.

I may not know much French, but Lizzie Brocheré (The Magic Mountain, 2017′s Rings) is a wonderful narrator. At least half of the film’s lines come from Marona narrating her unfolding life. In her voice, Brocheré captures numerous emotions: joy, regret, indignity, confusion, yearning. Marona, whose understanding of the world is similar to that of a young child, is devoid of enmity – even when faced with humans showing little concern or dismissive of her well-being. The film keeps Marona’s narration to a certain register, leaving the greatest narrative subjectivity to the film’s visuals and not Marona herself. Marona’s narration reveals how she interprets the world around her:

[Dogs] want things to stay exactly as they are... Humans always want what they don't have. They call it dreaming. I call it not knowing how to be happy.

Marona’s Fantastic Tale employs various animation styles in ways that may not feel sensible at first. Humans do not look like humans. They come in all colors of skin (blue, green, incomplete black crayon upon white construction paper etc.) and impossible figures (Manole, the acrobat drawn in yellow and red stripes, has stretchable, tubular limbs that any real-life acrobat would envy; other characters appear anything but humanoid). The most conventionally “human”-drawn characters in Damian’s film are those closest to Marona during her life – namely Istvan, Solange, and Solange’s mother. Marona, and the viewer, find comfort in these familiarly-shaped humans. Istvan’s predominant blue skin is a cool color, contrasting against his wife’s vaguely ostrich-like yellow-and-black appearance – attributes shared by her gossiping and materialistic lady friends, all of whom may need to see the doctor for possible jaundice. Like any animation director, Damian uses the character animation in this film to code viewers’ perceptions on a character. But the abstraction of Marona’s Fantastic Tale means she and her animators can further exaggerate characters’ physical aspects and experiment with color. The film’s backgrounds are a mesmerizing interplay of hand-drawn and CGI animation. Depending on where the camera is approaching, the apparently 2D backgrounds might unfold into layers of CGI, and vice versa.

These effects are bewildering. They appear as one might imagine a small dog might understand humanity’s vastness of appearance and personality, as well as the sprawling natural and man-made world they occupy.

youtube

Even more abstract through Marona’s eyes are the concepts of memory and time. On occasion, Damian has Marona reminisce about her past – an abstract flashback within a larger flashback. That past is filled with heartache – of being separated from her litter, her multiple abandonments. But in the confusion of understanding human motivation, Marona’s unconditional love for her mother and siblings and those who have taken care of her shines through. Hers is a melancholic loyalty, abiding despite abandonment. Time’s passage in the film is linear but inconsistent, leaving the viewer to make inferences for themselves. As a being with a short life, Marona has little time to find the most fulfilling, profound moments of her life in things that a human might deem mundane (in an occasionally funny piece of narration, she says, “A good sense of smell is worth a thousand words.”)

Every human in Marona’s Fantastic Tale is beset with character flaws and, with the exception of Manole, difficult familial lives. Their flaws may manifest themselves towards Marona, other humans, or both. Marona observes human frustration, jealousy, and pettiness and can always sense the unspoken tension that precedes a fateful action. Here, the film plays out not only as a simple flashback, but as a sort of dying wish. Marona, who we know is dying or is en route to what happens after death, appeals to the viewers without so much directly addressing them. It is an appeal for understanding: to realize our personal faults and to exemplify the consideration and goodwill that makes living worthwhile.

Some Western viewers might be irked that Marona dies in the film and that her death does overhang the proceedings. (They may be too accustomed to the excessively manipulative and stereotypical death fake-out so common in dog movies. Picture, if you will: a dog is shown to be in peril, the human characters hang their hands down acknowledging the likelihood of a dog’s death, but there is sudden uplift when, against all odds, the dog protagonist comes over the hill or rounds the corner and leaps into the arms of his caretakers.) But Anca and Anghel Damian have taken care to ensure that Marona’s death is handled as non-sensationally and abstractly as the rest of the film. Morbid it is not. That is no easy feat for any filmmaker, whether working in a live-action or animated format.

Marona’s Fantastic Tale does assume some life experience and contains presumed moments of cruelty, so I would hesitate to show the film to very young children. But the film should play well to slightly older children and, of course, open-minded adults. Marona’s Fantastic Tale is a film concerned about how time claims all, how dogs and humans might leave behind an example of love that sustains even in our darkest moments. That it does so convincingly through Marona drives this film’s beauty.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Marona's Fantastic Tale#L'extraordinaire Voyage de Marona#Anca Damian#Anghel Damian#Lizzie Brocheré#Pablo Pico#My Movie Odyssey

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Body Shaming in 'Harry Potter'

Re-reading the beginning of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, I’m surprised by how much I sympathize with the Dursleys. I don’t particularly like them in the general sense, but considering the scene where the Weasleys come to pick up Harry from their perspective, and Dudley’s perspective in particular, it becomes incredibly difficult to imagine a world in which they weren’t deeply skeptical and suspicious of magic. Magic, for the Dursleys, is scary and destructive, and for Dudley, in particular, has enacted much violence upon his body.

It is no secret that I have been a long-time fan of the Harry Potter series, as something that I have held near and dear to my heart for a long time, and at certain points in my life it has filled the religious and spiritual void that I felt within myself. And yet, as much as I often treat the series as a sacred text, there are a great many failings, and nowhere do I feel that is more clear than in the vicious attacks that are made against those who do not fit into the conventional molds of body image. The narration of the text uses the description of the body as a weapon, and a proxy for how we are meant to feel about a given character.

This is not uncommon in storytelling, and not unique to Harry Potter. The common narrative that society tells us is that pretty people are good and ugly people are bad, and society also tends to have pretty strict and nasty ways of describing who fits into either of those categories. The Harry Potter series is one in which there are very few characters where their race is explicitly stated, which is good because it means that there is room for interpretation. But one thing that is often explicitly stated in the text is when a character is being described negatively, they are given a value judgment based on their appearance and how they achieved that appearance. And nowhere is that more clear than with Dudley Dursley.

From the moment that we are introduced to Dudley, we are given the impression that he is a misbehaving child — the first word his says is either “shan’t” or “won’t” depending on your edition and he is described as “kicking and screaming for sweets.” He’s called a “beach ball” and a “pig in a wig.” Again and again the reader is hit over the head with the fact that Dudley — who is bad — is fat, while Harry — who is good — is skinny. Dudley is spoiled and petulant, and yes, he’s a bit of a horrible kid, but also he has really horrible parents. Dumbledore is not wrong in book six when he says that Vernon and Petunia have done a disservice to Dudley in treating him the way that they have. But Dudley is also mistreated by wizards. Hagrid gives Dudley a pig’s tail — was intending to turn him into a pig completely — and knows that he cannot reverse that. He never does reverse it, and by telling Harry not to tell anyone (protecting his own interests since Hagrid is not supposed to use magic) Hagrid dooms Dudley to needing to get the tail surgically removed by Muggle means, which was no doubt expensive, humiliating, and painful.

The ton-tongue toffee incident, which is what prompted me to ruminate on all this again, I found to be just so cruel. Because Dudley is on this incredibly forced and restrictive diet, being taunted by Harry — who is not following it at all — and is basically going cold turkey on all the foods he has normally had. His whole worldview has shifted when his version of normal (although it was anything but) changed. He’s not actually starving, but he probably feels like it, because it is such an abrupt shift in his eating habits. And here are the first sweets he has seen in probably months, and they cause this horribly, physically, and psychologically painful incident.

Then, only a year later Dudley has the experience with the dementor, a monster that almost sucked out his soul. This is often remarked upon as the turning point, where Dudley starts to evaluate his actions and change his ways. And yet this change is due to a real violence by magic, and as a whole magic has not been kind to Dudley. Nonetheless, at the start of the seventh book he was able to make an effort to reach out to Harry. The problem is that it’s framed as though Dudley only gets to make this transformation into a better person once he has matured enough to start getting into a “better” physical shape. Once he takes up boxing, and becomes athletic, his bulk is attributed to muscle rather than fat. Only then is he allowed to be something akin to a better person.

All over the Harry Potter canon we see unpleasant people described as being ugly. Pansy pug-faced Parkinson. Umbridge the toad. These are the people we are clearly supposed to dislike, and these traits are not assigned to antagonists as a way to set them apart. But the way it works with fatness is a bit different, because for all that Vernon and Dudley are called out for their weight, the characters we are supposed to like, even if they share a somewhat similar physical shape, don’t get this treatment. Neville, for example, is simply called a “round-faced boy.” But the actors who play Neville and Dudley looked so similar to each other when I watched Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone for the first time at age five that I got confused and thought Dudley had somehow ended up at Hogwarts. And Mrs. Weasley is described as being “plump.” Ludo Bagman, who is a character we are meant to both dislike and sympathize with, is described in middling terms.

“He had the look of a powerfully built man gone slightly to seed; the robes were stretched tightly across a large belly he surely had not had in the days when he had played Quidditch for England. His nose was squashed (probably broken by a stray Bludger, Harry thought), but his round blue eyes, short blond hair and rosy complexion made him look like a very overgrown schoolboy.” — Chapter Seven ‘Bagman and Crouch.’

These small moments in the way characters are introduced make the characters memorable, but they are also slightly insidious, and not at all kind when the narrator doesn’t want to be.

All told, fitting the conventional mold is not a universally bad thing, but the way this is portrayed is problematic because the way in which certain characters but not others are shamed for their weight/appearance seems to promote the idea that being treated with respect regarding one's body is a privilege that can be revoked in response to bad behavior, rather than the basic human right that it should be. This falls into a pattern of privilege where some privileges, like how Dudley is spoiled by Vernon and Petunia, are things that no one should have, whereas the privilege of being afforded basic respect regardless of one’s body type is a privilege that everyone should have.

There are also many slights against people who are perceived as thinner too. Petunia, for example, is often contrasted against Vernon as being quite thin. In their first introduction, they are compared as having “hardly any neck” and “nearly twice the usual amount of neck” respectively. The critique of Petunia’s size is on the opposite side of the spectrum, but it’s there, and it shows that the body-shaming in the series is across all body types, and in particular, directly correlated with a character’s likeability.

I’m not capable of cancelling in its entirety something so fundamental to my worldview as the Harry Potter series. But the more often I return to the text as an adult, the more flaws I find. In a way, that is almost a good thing, because in finding the parts of Harry Potter that don’t hold up to scrutiny, I am able to hold a mirror to the ways society as a whole does not hold up to scrutiny. At the same time, I can’t say that in good faith, because Harry Potter is a book series targeted at children, who can through the lens of these books (as well as the rest of society’s pressures) internalize the idea that it’s OK to make value judgments about someone based on their body, which is simply not true. We must imagine people complexly. And I guess that means we have to imagine books complexly too.

Header image via Wizarding World

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

BBC’s The War Of The Worlds blog - Episode 3

(SPOILER WARNING: The following is an in-depth critical analysis. If you haven’t seen this episode yet, you may want to before reading this review)

You know, people often ask me why I get so angry when I’m reviewing BBC shows. I mean yes I give Disney and Marvel a hard time too, but they don’t get nearly as much bile and venom as I give the BBC. Well that’s because, unlike Disney and Marvel, BBC shows are funded by the British taxpayer through our TV licence fees. I’m effectively paying for them to make this crap. That’s what pisses me off more than anything.

Yes we mercifully come to the end of this... this. Episode 1 was a slow, plodding and utterly tedious affair that was about as exciting as an Amish bachelor party. Episode 2 was even worse thanks to its poor narrative structure, terrible characterisation and less than subtle allegories. Now Harness has come to hammer the final nail in the coffin with Episode 3. Is it bad?

...

You’re right, that’s a stupid question. A more apt question would be how bad is it. Very, very bad is the answer. Very, very bad indeed.

Lets start with the obvious problem. The non-linear narrative introduced in the previous episode. The stupid early reveal that the Martians ultimately lose and that Amy survives completely destroyed any and all tension and suspense thanks to Peter Harness desperately trying to outwit the audience instead of just telling a story. Now, bizarrely, he tries to reintroduce tension by having the characters umming and arghing about what killed the Martians off and whether this could help stop the Earth from terraforming. One teeny, tiny problem with this though. The audience already know! Even those that never read the original book know how it ended! And even if you didn’t, the episode drops enough hints like great fucking boulders. The prevalence of typhoid throughout the episode and its correlation with the Martians stumbling around like a drunken prom date isn’t exactly hard to miss. Harness’ writing is still as unsubtle as ever. But worse still, he completely undermines and misses the point of the ending to War Of The Worlds.

One of my biggest pet peeves is when people (mostly Americans) criticise the end of the original book for being a deus ex machina. I mean the Martians get killed off by the common cold. How stupid, right? Except it’s not because those people (mostly Americans) are looking at it the wrong way. Your main takeaway shouldn’t be that the Martians were easily killed off by bacteria. Rather that we failed to stop them. The reason humanity prevails in the end is more down to luck than anything else. The narrator even attributes this to being an act of God. But here’s the thing. We didn’t stand a chance against the Martians. We didn’t beat them. They lost because they just happened to catch a cold. Now it’s not hard to imagine a society as scientifically advanced as their’s to be able to find some kind of cure or vaccine for it. And if and when they do, what then? We’d be fucked, wouldn’t we? Should the Martians ever return to finish what they started, the human race would be well and truly doomed. It’s not a deus ex machina. It’s a dire warning of what’s to come. A brief respite before the inevitable. That’s what makes the ending so effective.

The BBC series however completely misunderstands this, changing the story so that Ogilvy (an astronomer, don’t forget) somehow manages to weaponize typhoid in order to kill the red weed, which is presented as some kind of victory, when in reality it’s quite an insulting deviation from the source material. If only the Commonwealth could shake off the remnants of British colonialism as easily as these guys dealt with the red weed. Not to mention it just makes the Martians look really stupid. So they come to Earth, drink our blood, keel over and then... what, they just give up? Are they just waiting for humanity to die by itself? What happens when Mars HQ realises the red weed hasn’t worked? What then? Are they just going to shrug it off? It doesn’t make any sense.

Which brings us to the Martians themselves. The picture above comes from the Jeff Wayne musical version and is without a doubt the most accurate depiction of the Martians from the book. Most of the other adaptations have wildly different interpretations, which isn’t a problem in and of itself provided it works within the context of that particular narrative. However the reason I bring up the original design is so I can talk about what H.G. Wells intended when he came up with them. See, while the Martians are highly intelligent, they’re also presented as being quite vestigial. They’re sluggish thanks to Earth’s heavier gravity, rendered practically deaf thanks to Earth’s dense atmosphere and apparently have no organs with which to digest their food, hence their need to inject human blood directly into themselves for sustenance. The Martians represent what humanity could become as we become more and more reliant on technology. The Industrial Revolution brought about a lot of societal fears and concerns at the time, and the Martians are those fears manifested. Heartless creatures reduced to being simple brains, unable to properly interact with the world around them.

The BBC series goes a very different route. Instead of the giant brains, we instead get giant brown crabs, which, again, isn’t necessarily a problem provided it works in context. And that’s the problem. It doesn’t. The original Wells design told us what we needed to know about their biology, their motivations and their society. What do we learn about the BBC Martians? They’re big, generic monsters that look like rejects from Stranger Things. They don’t even inject blood into themselves. They feed off of us directly, leechlike. They’re more like animals. Not the vast, cold, unsympathetic intellects they were described to be. At no point do you buy that these creatures would be capable of building the Tripods or colonising the Earth. They just exist for some cheap jump scares and horror movie cliches.

What’s worse is that by changing the Martians’ design so drastically, any subtextual allegory gets chucked in the bin. The Martians from the book are meant to represent the British Empire at the height of its power. Merciless tyrants stomping all over the lives and cultures of the so called ‘lesser races,’ changing the environment to suit them rather than adapting to the existing environment. It’s Darwinism crossed with arrogance. And yet, ironically, the oppressors (the Martians) are technically inferior to the natives (the humans) as they are incapable of surviving without the aid of technology. The BBC series is unable to make this allegory, so Harness has to resort to straight up telling the audience the allegory. In by far the clunkiest scene in the entire series, we see George argue with his brother about how the Martians are no different from the Brits in their colonial ways. Not only does this break the ‘show, don’t tell’ rule and stands as a perfect example of bad storytelling, Harness doesn’t even bother to do anything with this other than just making the comparison. It’s been previously established that Amy was born and raised in India. You’d think she’d have something to say about all this, but nope. At the end, she wistfully describes India to her son in the most patronising and insulting way possible. It’s really quite disgusting. I mean H.G. Wells was quite patronising towards the Tasmanians in the book, but in his defence, he was a privileged white man from the 1800s. What’s Peter Harness’ excuse?! Ostensibly he pays lip service to the idea that the Martians are no different from the Brits, but he doesn’t want to really explore it or get us to actually think about it. Probably because it’s all a bit too complicated to get into, but if he’s not confident about exploring such topics, why the fuck is he adapting War Of The Worlds in the first bloody place?! Write something else!

In fact I think this is the root of all the problems with this adaptation. Harness clearly isn’t capable of exploring the complex themes of the source material, so instead he either introduces irrelevant social issues that aren’t nearly as complicated (women’s rights, empires are bad and so on) as a token show of progressiveness, or he goes as far as to uncomplicate themes and ideas to an almost offensive degree. In the book, the narrator is trapped in a church with a priest who is going through a major existential crisis and risks giving away their hiding spot to the Martians, who are busy terraforming the planet. So he resorts to knocking the priest unconscious and watching as the Martians drag his body away. In the BBC series, we see the old woman and the kid get killed off for no reason other than shock value and the characters have nothing to do with their demise, so they’re morally in the clear. The priest meanwhile doesn’t even appear in the scene, instead being relegated to the shitty flash forwards where his faith remains very much intact and even protests against the idea that it’s humanity’s illness that stopped the Martians rather than an act of God (brief side note, would Ogilvy really be this open about not believing in God? At the time of the book’s publication, the scene with the priest losing faith was considered extremely controversial, so this just seems utterly wrong). Plus there’s no tension in wondering what the Martians are doing and whether they’re going to find the characters. In fact there’s no tension whatsoever because we know the Martians have fallen ill and the characters are just hanging around, waiting for the fuckers to die. I cannot stress enough how atrociously awful the writing is in this show. We know the Martians are dying and the episode is about the characters waiting for them to die.

Jesus fucking Christ!

The Artilleryman from the previous episode was the same. In the book he was a deluded crackpot who willingly bought into imperialist dogma, believing that humanity could rebuild underground and eventually rise up and defeat the Martians. In the BBC series, he was a scared, innocent little waif being forced to fight in a war he wants no part of. It’s an incredibly shallow and uninteresting reinterpretation of the source material.

But the worst, the absolute worst, is what Harness does with George.

To be clear, no I’m not upset he gets killed off. I’ve made my views on him quite clear. He cheated on his wife because she was infertile and ran off to make whoopie with some redhead. The bastard deserves everything he gets, frankly. Plus I’ve had enough of Rafe Spall’s gormless acting to last a lifetime, thank you. What I am upset by is the way he gets killed off.

One of the most interesting parts of the original book is the fact that there are no heroes in War Of The Worlds. The Artilleryman is a young, impressionable, nationalist fool, the Priest descends into a pit of nihilistic despair, and the narrator survives only by his cowardice. He even goes as far as to attempt suicide, throwing himself in front of the unbeknownst to him dead Tripod because he cannot bear the idea of living in a world like this. It’s extremely dark and very cynical. The BBC series goes a very different route. We see George slowly become delirious as a result of the typhoid infection he got by drinking the poisoned cup of water in the previous episode (so all that stuff about the Martian terraforming was a load of bollocks) before, realising that he is becoming a burden to Amy, deciding to make the supreme sacrifice and facing the lone Martian alone while she makes a run for it. Not only does this open up a major plot hole - who the fuck was Amy expecting to arrive from the North if George is dead? They try to dismiss this as memory suppression, but I’m pretty sure that doesn’t apply to losing a loved one to a fucking alien - it also completely stands at odds with the themes of the book. When facing annihilation at the hands of a higher power, the arrogant Brits, who previously lived a life of privilege on the backs of millions of subjugated, reveal themselves for who they truly are at their core. The BBC series says yeah, we were a bunch of racist tosspots with delusions of grandeur, but we weren’t all bad. The main takeaway I got from this despicable, badly written series was a three hour pity party about how all those selfish POCs don’t consider the feelings of white people and asking why can’t we all just get along.

Peter Harness’ bastardisation of War Of The Worlds is without a doubt one of the worst adaptations I’ve ever seen. In fact it’s quite possibly one of the worst TV shows I’ve ever seen, period. It’s not just the sheer disregard for the source material that upsets me. It’s also the absolute amateurish nature of the whole fucking thing. This series fails in some of the most basic ways. His writing is truly terrible, somehow getting steadily worse and worse with each episode. It’s not just upsetting to see someone get the fundamental elements of storytelling so spectacularly wrong, it honestly makes me sick to my fucking stomach. Peter Harness, please, for your own sake and my sanity, stop fucking writing. You’re clearly not good at it and I don’t want to see my money go to someone who obviously hasn’t the faintest fucking idea what they’re doing. Enough is enough.

So it would seem that Jeff Wayne’s musical version remains the best adaptation of War Of The Worlds. In fact can we just have a movie adaptation of that please?

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daughter of Dr. Jekyll

John Agar’s in this. So, for that matter, is Gloria Talbott from Girls Town and The Leech Woman, and it was directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, who brought us The Amazing Transparent Man. It was released on a double-bill with The Cyclops, which I’ve already reviewed, and while all that seems to promise us an utter crapfest, the premise at least sounded intriguing. Then I actually pressed play, and was greeted by an opening consisting of gray fog, theremin music, and a bored narrator. Oh, yeah. This is gonna suck.

Said opening narration very (and I mean very) quickly introduces us to the tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, in which a distinguished scientist used a strange potion to turn himself into a werewolf! Wait… that’s not what happened in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at all. Wasn’t it a story about how every person has the capacity for evil and that’s part of what makes us human, and… aw, fuck it, this is a John Agar movie. Okay, sure, a werewolf. Whatever you say, Portentous 50’s Narrator. Moving on.

Janet Smith and her fiancé George Hastings arrive at her family’s palatial home, which she will inherit on her upcoming twenty-first birthday. That’s not all that’s come down the family line, though. Janet’s last name is not Smith, but Jekyll, and she was born after his experiments in lycanthropy had begun. Might she pass it on to her children? Or might Janet herself not be affected? Or is her father’s old friend Dr. Lomas an evil hypnotist using her for his own ends? Wait… what?

After sitting through crap like The Incredible Petrified World and Creatures from the Abyss, I kind of want to give extra points to Daughter of Dr. Jekyll. It’s actually fairly well-constructed for the most part, it’s rarely boring, and the sets representing the Jekyll family estate are very nice. There’s a plot I can follow, I know who the characters are, and so forth… my standards have dropped so low, that’s actually kind of impressive. The creepy delivery guy who hangs around whittling stakes and sowing discontent is pretty effective, himself, even though he’s a very one-dimensional character.

There’s still plenty of badness to be had, of course. The movie appears to be set in the first decade of the twentieth century, but it’s not very committed to that. The sound is frequently weird, from the absolute cacophony of frogs at the opening to musical cues that I swear were stolen from Robot Monster. There’s a random cameo from a very 50’s pin-up girl who appears, gets killed, and vanishes without us ever even learning her name. The climactic fight between George and the werewolf is extremely shatnery and the werewolf makeup is even lamer than in Werewolf in a Girl’s Dormitory.

Even worse, there’s an entire subplot that kind of doesn’t even bother happening. Most movies that are going to involve angry villagers have some scenes in a local pub or something to show the rabble being roused – even The Giant Spider Invasion had that. In Daughter of Dr. Jekyll we hear about angry villagers from a couple of different people but never actually see them until the pitchfork-toting crowd appears out of nowhere at the end. It’s like an angry flash mob. All we needed was a few thirty-second scenes, but I guess this movie couldn’t afford villagers. The whole climax is obscured by fog that makes it very hard to tell who’s who and what’s going on.

As usual, we’re confused about who our main character is supposed to be. The person whose eyes we see the story through is Janet. It’s Janet whose arc we follow, and Janet who we learn the most about, but she’s a very frustrating character because she is entirely without agency. The only choice she appears to make in the entire film is agreeing to marry George, before this story begins. Otherwise, she’s letting him or Lomas tell her what to do, completely incapable of making her own decisions (she even says as much, when George asks her if she’d like to go to London and elope). When the action occurs, she’s drugged with sleeping pills or in Lomas’ hypnotic thrall.

Even the very premise strips Janet of control over her own fate. She is not the heir to a scientific legacy (as other descendants of Henry Jekyll in other movies have been) but to a genetic one. Tanya in Lady Frankenstein chose to continue and improve on her father’s work. She might not have. Janet, on the other hand, cannot opt out of the family’s potentially tainted DNA. This lack of control is reinforced through smaller events as well: George won’t let Janet change her mind about marrying him, and when the young couple tells Lomas they don’t want his money or estate, he reveals that both were actually Janet’s the whole time. Like Eddie in The Beatniks, Janet is basically a victim even when good things are happening – they always happen to her rather than because of her.

The character who actually tries to take control of the situation, and who I think we’re supposed to see as the ‘hero’, is George – but we know nothing about George. He loves Janet and he has terrible fashion sense, and that’s really it. It’s her family we learn about, and her mental disintegration that follows. George spends most of the movie just hovering on the sidelines watching, and even at the end he doesn’t do very much. He explains what’s really going on to Janet and the audience (though we’ve already figured it out) and gets his ass kicked by a geriatric werewolf. The monster is actually killed by the mob of villagers, while George just stands there with Janet sobbing into his shirt. The movie probably wouldn’t have been much different without him.

The thing that really takes the viewer out of the movie, however, and does so repeatedly for its entire seventy-minute running time, is that it can’t make up its mind what its monster is supposed to be. I already mentioned the narrator’s conviction that Mr. Hyde was a werewolf, but it gets way weirder and more confusing than that.

The servants at the Jekyll house also talk about werewolves, and tell Janet and George in threatening voices that they know how to deal with such creatures. On the other hand, when Dr. Lomas himself tells them what happened, he tells the story we’re familiar with: Dr. Jekyll wanted to separate the good and evil parts of a person, and ended up giving the evil in himself a free agency of its own. This made me think maybe the servants were just a bunch of superstitious peasants? Maybe they called Mr. Hyde a werewolf because they didn’t know what else to call him? That almost started to make sense… but then George picks up a book about werewolves, and in its pages he reads that a werewolf leaves its tomb on the night of the full moon so it can drink blood, and can only be killed by a wooden stake through the heart.

Wait. What?

That… that’s not werewolves! Werewolves are killed by silver bullets! Stakes through the heart are vampires! Werewolves don’t have tombs! What is going on here?

By the time the climax rolls around, we’ve already figured out Dr. Lomas’ evil plan, and sure enough, it turns out he’s hypnotizing Janet into believing she’s a werewolf so she will commit suicide and he can have her family’s money. That makes sense in a Scooby-Doo kind of way, I guess, and I can accept it for the sake of the movie… but then he actually turns into a werewolf and goes out to suck blood! What? What? How did that happen? Was he playing with Jekyll’s formula? But Jekyll turned into Hyde when he took the drug, not at the full moon! What the fuck?

The movie never explains itself. We’re just supposed to take this bizarre conflation for granted. But vampires, werewolves, and Mr. Hyde are three totally different types of monster! Vampires are undead corpses who avoid decay and death by sucking blood. Werewolves are living people who transform under the full moon and kill out of animalistic rage. Mr. Hyde was Dr. Jekyll’s repressed evil side given form. You could probably argue that all three have the same root, in our need to conform to certain standards in order to make society work, but Daughter of Dr. Jekyll doesn’t try to do that. It just mixes and matches story bits at all, combining conflicting mythologies and leaving very visible seams. In fact, we may as well consider this a Frankenstein movie, too!

I can only imagine the fun Mike and the Bots would have had with this confusion. I’m picturing a game show in which they must match the weapon with the monster, and if they lose, they get eaten. Tom would have figured out that you survive by picking what ought to be the wrong answer. Crow would not.

The opening narration of Daughter of Dr. Jekyll notes that Robert Louis Stephenson’s book is a classic, and it is so for good reason. It’s an exploration of the evil within us all, the intrusive thoughts and secret desires we would rather attribute to an alter ego than ever admit to anyone, and the fact that the sinner is as much a part of each of us as the saint. Daughter of Dr. Jekyll throws all that out the window by equating its villain with a vampire/werewolf, making him a sort of mindless monster. It’s confusing and annoying, and its compelling source material deserved far better.

#mst3k#reviews#episodes that never were#daughter of dr jekyll#oh shit it's john agar#50s#you is a warwelf#just fuckin weird

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Contention of Voice: Alan Moore’s Reshaping of Mr. Hyde’s Monstrosity ••• By Lissa Heineman

Having now completed The League of Extraordinary Gentleman’s fourth volume, it is possible comic culture’s favorite uncle, Alan Moore, is officially retiring from comics. The graphic novel series is celebrated for its gallery of famous characters from literary history, acting as a new-age compendium for Industrial Revolution-centric anachronisms. It’s both a Lit Degree-er’s nightmare and playground, remixing themes and characteristics from different classic works together. One such example is Moore’s take on the OG, 1800′s Hulk, Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was published in 1886, a time in which the debate around science and religion was intense. Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species had been released in 1859 and made the Victorians begin to question their ‘infallible’ faith in God’s unlimited control, but also be wary of metaphysical sciences — a phenomena that studies the fundamental nature of reality. The book used its main characters to generate discourse about morality, reasoning, science, and faith, while reflecting upon the growing uncertainties that came with fin-de-siecle, or end-of-the-century, culture. To the modern reader, the basic message of Stevenson’s novel is clear: Hyde wasn’t simply a monster, and consequence of metaphysical practices, but a manifestation of Dr. Jekyll’s repressed self. However, this leaves a question of how human Hyde is in comparison to Dr. Jekyll, if they are one in the same. What is Mr. Hyde’s personhood? It is through the introduction of Alan Moore’s take on the character(s), that Mr. Hyde’s own character takes shape. By integrating characteristics of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murder in the Rue Morgue into Hyde’s storyline, Moore argues for Hyde’s personhood and agency, not allowing him to simply be a figure of the Victorian’s metaphysical anxieties.

In Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Jekyll is described as having become “too fanciful… [and going] wrong in mind,” practicing “unscientific balderdash” (Stevenson 12). Jekyll is framed as immoral, particularly in comparison to the book’s protagonists. His ‘science’ is described as “transcendental medicine” (Stevenson 52), ie: metaphysical inquiries. Jekyll’s research, and his addiction to his own chemicals, code him as a heretic. Stevenson indicates that Jekyll, himself, is problematic. Yes, Hyde is young and brutish with more physical capabilities than the older, deteriorating Dr. Jekyll, but he certainly isn’t the degenerative juggernaut illustrated in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Rather, Mr. Hyde is described as “troglodytic” (Stevenson 16), “ape-like” (Stevenson 20), and “a monkey” (Stevenson 39). These descriptions of Mr. Hyde allude to the backwards progression of man’s evolution, as chronicled by Charles Darwin and the likes of Thomas Henry Huxley, reaffirming Jekyll as representative of a bastardization of London’s moral ideals of the time.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen clearly takes some creative liberties with its depiction of Mr. Hyde. In Issue 1, Hyde is seen easily holding Quatermain feet above the ground, close to the ceiling, easily in one hand, fangs barred and tendons and veins practically bursting across his collar and face. Across the same two-page spread, Auguste Dupin attempts to defend himself and Mina Murray from Hyde, shooting the monster in the face. Part of Hyde’s ear is blown off, which only increases Hyde’s anger, emphasized by the all-capitalized dialogue bubbles. Not only does Hyde retain the apishness described in Stevenson’s novel, but it is intensified, as seen via the fangs, flared nostrils, incredible muscle definition, and the overall brownishness of his complexion. He towers over all the other characters dramatically, alluding more to King Kong than how earlier adaptations had illustrated the character, which often emphasized “neanderthal” over “monkey”. Hyde was popularly depicted as an unkempt, twisted, and hunching man across films and drawings. There can be many reasons for this deviation within the comic’s universe, but one of the most obvious links is in how this Hyde is adapted not only from Stevenson’s work, but also Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. The murders attributed to Hyde by Dupin in The League are ones that were committed by the Ourang-Outang in Poe’s short story. Even the way that Hyde’s anger increases when Dupin shoots him mirrors how the Ourang-Outang becomes agitated enough to murder the two women, which occured only when one of the women provoked it by screaming (Poe 35). Moore masterfully blends together Hyde and the Ourang-Outang to display the animalistic qualities of the former character.

However, what is most interesting regarding Hyde in The League is his communication -- his literal ability to speak. Never at a single point in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde does Mr. Hyde speak; we only hear Dr. Jekyll himself talk. A large part of Poe’s Rue Morgue mystery is based in “voices in... contention” (first on Poe 11). Witnesses heard the then-mysterious “arguing” of the deep-voiced French sailor and the shrill shrieking of the Ourang-Outang, and found the ape’s voice to be unidentifiable in gender and nationality. Dupin notes that:

"the voices of madmen, even in their wildest paroxysms, are never found to tally with that peculiar voice heard upon the stairs. Madmen are of some nation, and their language, however incoherent in its words, has always the coherence of syllabification” (Poe 28-29).

Poe introduces the idea that language is a characteristic of a nation, and therefore language being linked to personhood. It is this argument that leads to Dupin’s logical deduction that the murderer couldn’t have been human at all, as he didn’t have language or nation, and it is this language that brings us to question the boundaries between both Stevenson and Moore’s version of Jekyll, Hyde, and their divide.

Stevenson’s Mr. Hyde is a ‘mask’ for Dr. Jekyll; we never engage in Mr. Hyde’s perspective, and while Dr. Jekyll uses the potion to maintain control over both himself and his alternate-persona, we are never given evidence that Hyde himself has his own perspective. Hyde’s activities across the novel are described as bouts of rage that mirror the kind of blind activity that the Ourang-Outang perform: they are mindless performances of heated passion and emotion. On the other hand, Dr. Jekyll’s role is indisputable. In his confession of the murders in Stevenson’s novel he admits that he “mauled the unresisting body” (Stevenson 60), rather than referring to himself as Mr. Hyde, which would relieve himself of blame or control. This reaffirms Hyde as a costume for Jekyll’s depravities. Even in the final chapter, “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case”, where Dr. Hyde’s body is “in control”, the character still refers to himself exclusively as Dr. Jekyll. Dr. Hyde is never autonomous, and he is never a singular being. These facts create a gap in how to read Mr. Hyde at all, because despite his own embodiment, he is very much just Dr. Jekyll.

Despite performing similar brutalities to Poe’s monster, Hyde/Jekyll is very human. However, when he’s offered a voice by Moore, Hyde becomes separate. Jekyll isn’t speaking through Hyde, and Moore’s Hyde becomes a near-replica of the dynamics that Marvel’s Bruce Banner and the Hulk engage with, as well as that of Poe’s Ourang-Outang and the Frenchman, who feared being accused as guilty for the crimes of the ape. Such dynamics are further displayed by Moore in Champion Bond’s explanation of Jekyll/Hyde. He describes Dr. Jekyll as “a highly moral individual” who “become(s) Hyde” whenever he is stressed (Moore Vol. 1). Moore and Stevenson’s characters here are distinctly separated. Moore’s choice to depict Hyde and Jekyll as split shifts the blame of Jekyll/Hyde’s actions away from Stevenson’s intended perpetrator: Jekyll, and onto Hyde, transforming Jekyll into a victim. Jekyll even offers a warning to the League as they approach the Limehouse District. With sweat beading across his forehead he admits “sometimes I’m not myself. I’m not sure I can always be relied on.” Stevenson’s writing posed a message that playing with science can drive a man mad and immoral. With Moore’s Hyde having his own distinctive personhood, Stevenson’s message is removed from the Jekyll/Hyde mythos.

Alan Moore offers an alternative take on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Departing from Stevenson’s classic allegory for the anxieties of scientific advancement, Moore uses the classic Poe story to explore Hyde as a separate force. Monstrosity, in the 19th century, was linked to the degradation of character and religion. However, Moore’s transferral of power over to Mr. Hyde, as suggested by both literal narration and the gift of speech, allows Hyde to take up the true mantle as a monster. Moore points to how this form of remix encourages reshaping perceptions of the familiar. This variation on Jekyll/Hyde can easily parallel the Ourang-Outang and the Frenchmen, Bruce Banner and the Hulk, and even deviating examples of both Frankenstein and his monster and The Fly’s Seth Brundle and Brundlefly, who both exemplify monsters with their own senses of personhood and creators who fall victim to their creations. One can see that Moore’s recharacterization of Hyde makes a classic work feel more approachable and non-other.

__

Works Cited:

Moore, Alan and Kevin O’Neill. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Volume One. California: America’s Best Comics, 2000. Print.

Poe, Edgar Allan. The Murder in Rue Morgue. Feedbooks, 1841. Online. http://www.feedbooks.com/book/795/the-murders-in-the-rue-morgue

Stevenson, Robert Louis., and Roger Luckhurst. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and Other Tales (Oxford world's classics). N.p.: Oxford U Press, 2006. Print.

#lissa heineman#graphicnovel#alan moore#books#the league of extraordinary gentlemen#dr jekyll and mr hyde#literature#comics#adaptation#remix

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Hirohiko Araki Is a Great Writer

Note: add writing saying “I am only going to be addressing JoJo because 1) I have not read his older works, 2) His works before and including Phantom Blood lack what I am talking about here and 3) I include JoJo spin-off manga under the “JoJo” moniker”

As the man behind one of the most influential manga of all time, Hirohiko Araki is already a highly praised writer and artist. However, I believe what lies at the heart of Araki-sensei’s writing style is not explored often enough. What I think are the most important factors in the writing of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure are the extremes to which the author takes his creative freedom and his skill in writing relationships between people.

Phantom Blood is the most conventional part of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. It has a structure very similar to other shounen manga at the time: hero has a rivalry, rival becomes obscenely powerful, hero learns martial art to defeat rival, ally dies, other ally narrates, hero wins etc. Phantom Blood’s writing only succeeds in the outlandish concepts introduced throughout: vampires appearing as a consequence of mayan blood rituals with magical stone masks, vampires somehow sucking blood by introducing their fingers inside a human’s skin, the power of the sun channeled (or created) by breathing, medieval warrior zombies, people being cleft in half by chains… frog punching. What also comes out here is a hint of the strategic battles the series will come to be known for, with Dio’s defeat at the hands of a burning sword.

A lot of the quality of the writing comes in the relationship between Jonathan and Dio, two characters who could not be more polar opposites who supposedly die together. While Jonathan is a typical nice guy shounen protagonist, Dio is a somewhat complex villain; he is irredeemably evil, but not unjustifiably so.

The decision to change protagonists was in itself an unheard of prospect at the time, each part bringing its own atmosphere and self-contained storyline, facts which allow Araki-sensei to explore all of them at length.

In comparison, Battle Tendency goes completely off the rails. If Phantom Blood is a cautious dip into the water, then Battle Tendency is a cannonball jump right into the deep end. This is where JoJo starts going from typical shounen manga to a manga characterized by battles of wits and skill rather than of pure brawn; and this change is reflected in its protagonist. Where Jonathan was the perfect gentleman who would never face his enemy anything less than head-on, Joseph likes to screw with his opponents’ heads. To show this change in character, his first major fight is against an enemy comparable to Dio, who is taken out a lot more easily thanks to Joseph’s fighting style. The insanity present in Phantom Blood is taken up to 11: the vampires are mere distractions to the new Pillar Men, Nazis are turned into Cyborgs and Hamon now apparently works on bubbles.

The relationship built between Joseph and Caesar is perhaps the most natural growth displayed in the series until this point. Their friendship grows gradually and culminates not with perfect teamwork, but with a realistic ideological fight between the two, one that Joseph would come to regret for many years to come. Caesar’s death is one of the most natural and powerful scenes in manga history, from the desperate dedication he displays even in his final moments, to Wamuu’s respect for him and to Joseph’s desperate cry for his best friend.

Stardust Crusaders is the start of Araki-sensei’s complete creative control. Stands now allow him to explore any fun and interesting idea he has in battles and to make stands that fit with their characters. The change of the format from single story to monster of the week supports the author’s writing style of throwing ideas at the wall and expanding them to his heart’s content. However, the clunkiness of his inexperience with such creative control is obvious. He is obviously pressured to come up with cool designs and powers for the stands (some of which he will later forget). In the second half of Part 3, getting used to the concept of stands, he starts writing interesting and fun ideas for his battles, like the D’Arby Brothers and Vanilla Ice. The insanity is punctuated by the increasing number of musical references (from Captain Tennille to Oingo Boingo).

Sadly, the characters take a backseat for the duration of this Part. Except for certain minor moments between the Crusaders, the characters don’t really have arcs (except for perhaps Iggy and Polnareff). For this reason, Jotaro, Kakyoin and Avdol are often criticized for having little to no character, which is a fair point. Jotaro himself is more of a superpowered version of the most barebone characteristics of Sherlock Holmes.