#early bronze age

Text

sundown at solstice (2223BCE)

merry midwinter folks!!

#winter solstice#oc art#stonehenge#folk art#the chief#chief’s life and lore#digital illustration#artists on tumblr#original comic#the lonely barrow#celtic folklore#bronze age#early bronze age#late Neolithic#happy solstice

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Stargazer", a statuette of a woman (c. 3300–1200 BCE) from Western Anatolia

(more info)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Say hello to an ancestoress

More than 4,000 years ago, a young woman who died in what is now Scotland was buried in a crouched position within a stone-lined grave. She remained buried for millennia, until excavators at a stone quarry unexpectedly unearthed her bones in 1997.

Little is known about the woman — dubbed Upper Largie Woman after the Upper Largie Quarry — but now, a new bust-like reconstruction reveals how she may have looked during the Early Bronze Age.

The reconstruction, which went on display Sept. 3 at the Kilmartin Museum in Scotland, shows a young woman with dark braided hair who is wearing a deer-skin outfit. And she appears to be looking at someone nearby.

"Making a reconstruction I usually think that we are looking into their world, [meaning] they don't see us," Oscar Nilsson, a forensic artist based in Sweden who crafted the woman's likeness, told Live Science in an email. "I thought it could be an interesting idea to twist this a bit, and actually thinking that she can see us. And as you can see, she looks a bit critical to us (I don't blame her for that...)!"

Upper Largie woman, who died in her 20s, lived during the early Bronze Age of Scotland. (Image credit: Oscar Nilsson)

After the discovery of Upper Largie Woman, a skeletal and dental analysis revealed that she likely died in her 20s and experienced periods of illness or malnutrition. Radiocarbon dating found that she lived between 1500 B.C. and 2200 B.C., during the Early Bronze Age, according to the museum. Meanwhile, a look at different isotopes, or versions of strontium and oxygen from her remains suggested that she grew up locally in Scotland, but the team wasn't able to extract her DNA, so her ethnic heritage, including her skin, eye and hair color, is unknown.

However, archaeologists found sherds of Beaker pottery in her grave, hinting that she was part of the Beaker culture, named for its peoples' bell-shaped beakers. Research suggests that the Beaker culture started in Central Europe with people whose ancestors came from the Eurasian Steppe. Eventually, the Beaker culture reached Britain in about 2400 B.C. DNA evidence indicates that the Beaker culture replaced most of Britain's inhabitants, including the Neolithic communities that had built monuments such as Stonehenge.

"The carbon dating suggests she might be a descendant of the first Beaker newcomers," Sharon Webb, director and curator of Kilmartin Museum, told Live Science in an email.

For the reconstruction of Upper Largie Woman, her skull was CT (computed tomography) scanned and then 3D printed in Scotland. However, "she lacked her mandible [lower jaw], and her left side of the cranium was in a quite fragmented condition," Nilsson said. "So, the first thing I had to do was to rebuild the left side of her cranium. And then to create a mandible, a rather speculative issue of course."

Then, Nilsson took her age, sex, weight and ethnicity into account, as these factors help determine tissue thickness. "So, in this case: a woman, about 20-30 years of age, signs of undernourishment in a period of her life, and a probable origin from the region," he said.

Nilsson pulled from a chart of modern individuals who fit these characteristics, then used their tissue measurements to begin sculpting the reconstruction. Pegs placed on the replica skull helped him measure the tissue depth, which he then covered with plasticine clay as he molded the facial muscles. Based on her skull's contours, he noted that Upper Largie Woman's eyes were wide set and that her nose was broad and "probably a bit turned upwards." She also had a rounded forehead and a broad mouth.

"I found it interesting that once she was reconstructed, I did not see that much of her malnutrition," Nilsson said. "She had a very rounded facial skeleton, which helped her looking a bit more healthy than she may have been."

However, he was clear that "the colors were all qualified guesses, based on other burials from the time and the region, where the DNA was in better shape than this one."

Webb called the reconstruction "absolutely amazing, we wanted her expression to be asking questions of the visitor, wondering who they are, and what their lives were like so that visitors might also ponder her life."

Upper Largie Woman's remains are now "sensitively 'reburied'" in the same position and orientation she was likely buried in 4,000 years ago, Webb said. Visitors can see her reconstruction at the museum's permanent exhibit.

#Women in history#scotland#Upper largie Woman#Kilmartin Museum#I don't blame her either#Oscar Nilsson#Early Bronze Age#Beaker culture

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

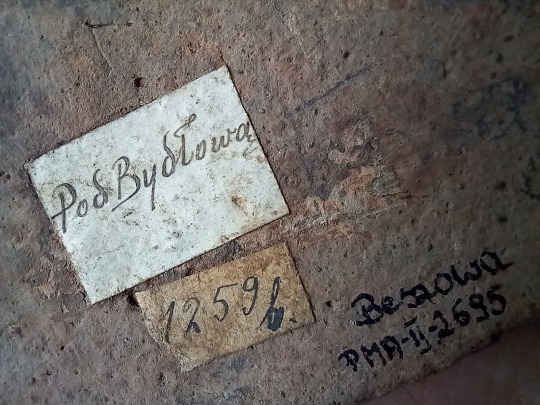

My pottery (part of it, from one box). i'm faster now and can do 70 fragments in 4 hours - thats still not very fast

very beautiful handwriting. nobody writes so neatly today :(

my pottery was found by the father of polish archaeology Erazm Majewski in the last decade of 19th century (or rather by peasant children who were given money to look each year gor artefacts uncovered by wind on sand dunes - he wanted to make a map of all sites in that area). surprisingly it survived both world wars - it's almost a miracle, bc the majority of artefacts in collection of archaeological museum was destroyed during the uprising.

inside the boxes there are small pieces of paper with notes written in ink by Erazm Majewski himself, i suppose. it's really cool. field notes written on fragments of packs of really old cigarettes

4100 years in the ground, 130 years in museum storeroom, and now it's in my hand :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knossian Board Game

This is modeled after an ancient bronze age artefact unearthed at Knossos, believed by archeologists to be an early board game.

The game is a chess clone and playing it will increase the logic skill.

Make sure when you are placing the object in build mode, you first attach chairs to the board game itself, and then place a table of your choosing underneath the game (using the commands testingcheats true and then bb.moveobjects on). If you do not follow these steps, the sims will not be able to sit and play!

BOARD GAME DOWNLOAD - Dropbox (no ads)

#my cc#my bb cc#sims 4 cc#sims 4 mods#sims 4 buy cc#sims 4 buy mode#sims 4 build and buy#minoan#knossos#bronze age#ts4cc#ts4mm#ts4 history#ts4 early history#ts4 ancient history#ts4 historical#ts4 historical cc#s4cc#ts4 cc

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Necklace of assorted beads.

Culture: Early Aegean, Minoan

Period: Bronze Age, Middle Minoan Period

Date: 1800–1550 B.C.

Medium: Stone and gold

#ancient#ancient art#ancient jewelry#jewelry#necklace#necklace of assorted beads#minoan#early Aegean#bronze age#gold#1800 b.c.#1550 b.c.#history#archeology#museum

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

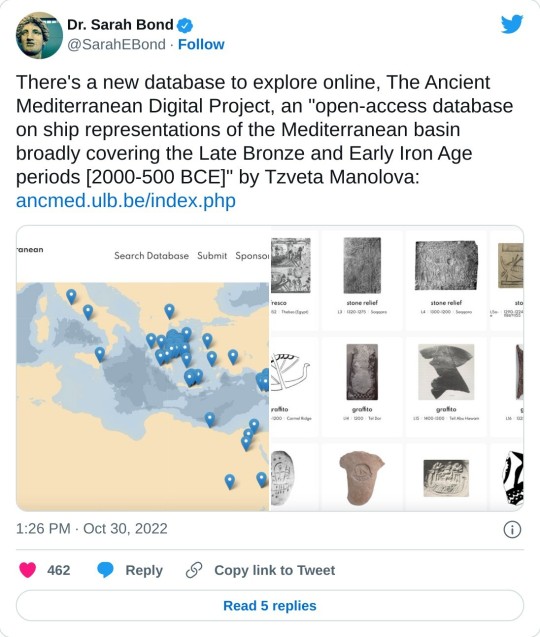

#tagamemnon#bit ill so lazily scrolling thru twt pt 2#ancient greece#ancient rome#late bronze age#early iron age#resources

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Marton Pool Logboat, Bronze Age to Early Medieval, Shrewsbury Museum, England

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#copper age#iron age#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#prehistoric#prehistory#logboat#early travel#early transport#ancient living#ancient craft#ancient cultures#Shrewsbury#woodwork#boat#archaeology

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Travel Question 22: Ancient History X and Earlier

These Questions are the result of suggestions from the previous iteration.

This category may include suggestions made too late to fall into the correct grouping.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration. All cultures and time periods welcome.

#Crinoids#Time Travel#Paleozoic#Proto-Indoeuropean#Ancient Religion#Neolithic#The Land of Punt#Ancient World#Linguistics#Early Humans#Tocharian#Indo-European#Yuezhi#Chinese History#Tarim Basin#Steppe Nomads#The Bronze Age#Cretaceous#Pharaoh Hatshepsut#Ancient Egypt#Wu Zetian#Minoans

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish dress history sources online:

A list of sources for Irish dress history research that free to access on the internet:

Primary and period sources:

Text Sources:

Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT): a database of historical texts from or about Ireland. Most have both their original text and, where applicable, an English translation. Authors include: Francisco de Cuellar, Luke Gernon, John Dymmok, Thomas Gainsford, Fynes Moryson, Edmund Spenser, Laurent Vital, Tadhg Dall Ó hUiginn

Images:

The Edwin Rae Collection: A collection of photographs of Irish carvings dating 1300-1600 taken by art historian Edwin Rae in the mid-20th c. Includes tomb effigies and other figural art.

National Library of Ireland: Has a nice collection of 18th-20th c. Irish art and photographs. Search their catalog or browse their flickr.

Irish Script on Screen: A collection of scans of medieval Irish manuscripts, including The Book of Ballymote.

The Book of Kells: Scans of the whole thing.

The Image of Irelande, with a Discoverie of Woodkarne by John Derricke published 1581. A piece of anti-Irish propaganda that should be used with caution. Illustrations. Complete text.

Secondary sources:

Irish History from Contemporary Sources (1509-1610) by Constantia Maxwell published 1923. Contains a nice collection of primary source quotes, but it sometimes modernizes the 16th c. English in ways that are detrimental to the accuracy, like changing 'cote' to 'coat'. The original text for many of them can be found on CELT, archive.org, or google books.

An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish By Joseph Cooper Walker published 1788. Makes admirable use of primary sources, but because of Walker's assumption that Irish dress didn't change for the entirety of the Middle Ages, it is significantly flawed in a lot of its conclusions. Mostly only useful now for historiography. I discussed the images in this book here.

Chapter 18: Dress and Personal Adornment from A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland by P. W. Joyce published 1906. Suffers from similar problems to An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish.

Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland Susan Flavin's 2011 doctoral thesis. A valuable source on the kinds of materials that were available in 16th c Ireland.

A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy Volumes 1 and 2 by William Wilde, published 1863. Obviously outdated, and some of Wilde's conclusions are wrong, because archaeologists didn't know how to date things in the 19th century, but his descriptions of the individual artifacts are worthwhile. Frustratingly, this is still the best catalog available to the public for the National Museum of Ireland Archaeology. Idk why the NMI doesn't have an online catalog, a lot museums do nowadays.

Volume I: Articles of stone, earthen, vegetable and animal materials; and of copper and bronze

Volume 2: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities of Gold in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy

A Horsehair Woven Band from County Antrim, Ireland: Clues to the

Past from a Later Bronze Age Masterwork by Elizabeth Wincott Heckett 1998

Jewellery, art and symbolism in Medieval Irish society by Mary Deevy in Art and Symbolism in Medieval Europe- Papers of the 'Medieval Europe Brugge 1997' Conference (page 77 of PDF)

Looking the part: dress and civic status and ethnicity in early-modern Ireland by Brid McGrath 2018

Irish Mantles, English Nationalism: Apparel and National Identity in Early Modern English and Irish Texts by John R Ziegler 2013

Dress and ornament in early medieval Ireland - exploring the evidence by Maureen Doyle 2014

Dress and accessories in the early Irish tale, ‘The Wooing of Becfhola’ by Niamh Whitfield 2006

A tenth century cloth from Bogstown Co. Meath by Elizabeth Wincott Heckett 2004

Tertiary Sources:

Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia edited by Sean Duffy published 2005

Re-Examining the Evidence: A Study of Medieval Irish Women's Dress from 750 to 900 CE by Alexandra McConnell

#resources#dress history#irish dress#irish history#early medieval#bronze age#textile history#late medieval#16th century#historical dress

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am obsessed with how fixated spideyblr is with the comics coffee bean gang and iterations of it — like we're objectively correct, but it's wild how other corners of the spider-man fandom see that part of the canon as ancient, obscure, and cringe?

#it's so strange to be talking to ppl who are spider-man ppl irl and they barely know the early stuff beyond references in modern runs#when i'm like canon peaked in the silver and bronze age and the later bronze age is on thin ice tbh

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

(via) This paper (preprint) essentially argues that the Indo-European expansion into Europe was accompanied by zoonotic plagues which arose in the Steppe, to which the IEs were adjusted (gently, via "long-term continuous exposure") and the Early European Farmers (the neolithic inhabitants of Europe) were not. They analogize this to the plagues which afflicted the Americas after the arrival of Europeans, correlating it with "increased genetic turnover" (population replacement) in Europe.

(So, two instances of Indo-Europeans conquering a continent in the wake of apocalyptic plagues. Which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened twice.)

Their method is to check for microbial DNA in samples of human remains. What they demonstrate, afaict, is:

a) Zoonotic diseases first appeared around the time of the IE migrations, being first detected in samples from 6,500 BP and peaking around 5,000 BP.

b) IEs are consistently more likely to be infected with zoonotic diseases than non-IEs. (This greater incidence of infection seems to persist throughout the period.) This "suggests that the cultural practices and living conditions of the former might have been more conducive to the emergence of novel zoonotic pathogens." (14)

So they don't directly demonstrate that EEFs were ultimately hit harder by these illnesses, they just say that it would make sense for IEs to have adapted to them. As far as I can tell, this is fair; they cite a paper which claims that increased disease pressure may have resulted in adaptations to multiple sclerosis in the Steppe and another which suggests a similar trend among Amerindians after the Columbian Exchange.

Things I don't know:

In a population being ravaged by epidemics, would you would expect the infection rate to remain lower than that of a (more) immune population, or would you expect the infection rates to equalize? Would you expect to see spikes in one population and a more consistent line in the other, or some other indicator of differential impact? I suppose you'd just need comparative evidence, presumably from the Americas.

As lifestyles equalized (until you're comparing an 80% IE and a 40% IE guy who live in adjacent villages in Italy 500 BC), why would the IE effect persist? Wouldn't you expect the correlation to fall over time?

Do pastoralists we can directly observe have higher rates of zoonotic disease than animal-having agriculturalists or animal-eating hunter-gatherers? That seems to have pretty direct bearing on their lifestyle hypothesis.

Is there a similar effect in other places where IEs migrated during the Bronze Age (say, India or Iran), or other places within Eurasia where agriculturalists came into contact with Steppe peoples? They have a couple of data points in Iran and Anatolia and a bunch in SE Asia (for some reason), but everything else is in Europe and central Asia/Siberia.

There's also an odd effect where the two major genetic contributors to the IE population have different effects, Caucasus hunter-gatherer descent being associated with all the zoonotic diseases and Eastern HG being associated mostly with black plague, which is sort of odd, if these are one population with similarly disease-fostering lifestyles.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

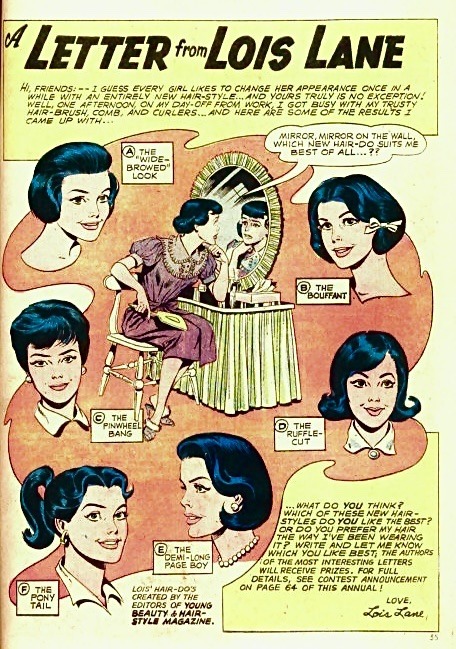

The 1962 Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane Annual 1 had a competition for Lois's new hairstyle (which they waiting another 5 years before integrating). This came after decades of her wearing her hair the same way in basically every issue since her conception (occasionally changed for fancy in-story events, and gradually shortening through the golden/silver age transition). After years of constant letters to editor complaining about her "old fashioned" and "stagnant" look, they put it to a vote...

The one they went with back then (after 5 more years of her classic look):

This was the first page of her new look in Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane #75 (July 1967), and some other examples from Kurt Schaffenburger (resident Lois artist):

And here are some other artist's interpretations of her base style in the years that followed!

#personally I LOVE the pony tail look and think it really would have fit her personality too#I do really like the pinwheel as well and they did give her a similar style in the late 80s/early 90s!#dc comics#superman#lois lane#superman's girlfriend lois lane#silver age dc#bronze age dc

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goat, Wolf, Raven - How we might've gotten gods

Okay, let me quickly talk about another very interesting mythology thing. I brought this up when talking about Pan, but it is very much worth an entry on its own.

People in the Stray Gods fandom have wondered, why Pan has so many animal features. And the answer is: Because he is a super early god predating most of the Greek pantheon. But of course for that to make sense, you also need to understand something else: The fact that most gods have started out as animals. Probably, at least. It is what we are guessing, but there is in fact a ton of evidence for it.

If you have ever ventured in any sorts of indigenous mythology - be it American, be it African, or be it South Asian - you will find that a lot of the characters are actually animals. There might be some humanoid deities around, but some deities or at least characters comparative to deities are animals.

We also know that this holds true for the cultures that first started building stuff. Because at those archeological sites we can find tons of animal idols, with good evidence, that some of those were worshipped.

In fact it is on those archeological sites that we also can at times see some of the animals taking on more and more humanoid features, often ending up as beings that are part animal, part human.

The probably widest known example of this is the Egyptian mythology with all the animal-headed gods. Which fits very well with this idea, given that indeed the creation of the Egyptian mythology falls into the timeframe during which we assume that this change took place in some places (between 5000 and 3000 BC).

As that autistic kid with a massive obsession on Egyptian mythology I can tell you: It was so weird to me back then, because I obviously lacked the comparative understanding, as my only reference points were Christian mythology and some smitherings of Greek and Roman stuff.

It was only much later that I started to understand this.

The thing is, that the probable reason why we got mythology and religion in the first place is, that our human brains just love pattern matching and they love trying to understand intent. Because we are just so well evolved for that. So, we watched nature and we saw patterns and intent.

A very probably understanding is, that we then also saw behavior in certain animals linked to stuff like weather events and the like and were like: "Yo, do you think that animal has something to do with that draught happening?" And hence turning those animals into characters and on the long term deities.

Why those animal deities got more human? Well, that is hotly debated. The explanation I find most likely is... Well, we see that shift into more humanoid deities around the time that more and more humans settled down, meaning that the societies people lived in also grew. While before those large settlements humans lived in groups ranging in size between a few dozen people to maybe three hundred, suddenly there were settlements with thousands of people creating the need for more complex tools of organizing human cohabitation. And... I think the shift from animal gods that were more forces of nature to more humanoid godly characters happened partly as a form of political tool.

But that is just me speculating. But it would explain the rise of more humanoid gods being linked to larger settlements. It would also explain why a lot of cultures that did not create large settlements had fewer humanoid gods. Don't get me wrong, they often had some humanoid deities... but also a ton of just animals doing their thing.

Funnily enough... We actually can find some of that stuff still in the Abrahamitic texts. Contrary to popular believe the snake in the garden of eden is never stated to be Satan or... anyone really. It's just a snake. So that snake actually might just be a leftover trickster character. Just as we have a couple of references in the Abrahamitic texts towards some people actually worshipping animal deities.

So, why is Pan part-goat? Well, because he is one of those transitional characters and people were like: "He is fine, we will just continue to worship this part-goat character. :D"

Fun fact: There are a ton of hints that at least one aspect of (so one deity merged into) Apollo was a wolf-trickster :D

#stray gods#comparative mythology#mythology#early humans#neolithic#stone age#bronze age#animal gods#egyptian gods#egyptian mythology

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

fascinating

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sphinx’s Son

The sandstone lions that guarded the Great Temple had human faces that were carved to look stern and imposing, but Arus thought that the statues just looked sad. They had his mother’s face, though the masons who had carved the human-headed lions had lived more than two centuries ago. Coincidence or the timelessness of a standard of beauty, the boy could not say which. Arus traced the names of the master stonemasons where the signatures were tucked away on the back heel of the statues, hidden in their cool shadows. The ridge of stone of the carved tail made a perfect bench for him to sit.

The temple processions, carried out by fifty people of various ages, marched on in loops between the temple colonnades. Ganreh, the favorite student of the head priest, led today’s procession, sweat dripping down his shaved head and wilting the starched linen of his tabard. The clinking sistrum dictated the cadence of the march, and the pinched expression of intense concentration on Ganreh’s face to keep the metronomic chinking of rattled metal beads consistent made Arus choke back laughter. Ganreh was too kind for scolding, but Head Priestess We-se would box his ears for disrupting the ceremony. The chanting combined with the sistrum to make a pleasant if monotonous song. Arus wondered if the real purpose was to soothe the gods to sleep with such droning lullaby-like music.

The attendant priestesses carrying the smoke-filled braziers noticed where Arus sat waiting for today’s procession to finish –the second of a six-day ceremony– but as Arus was silent and sitting clear of the path and not yet necessary for any of the rituals, their side-eyes were of measured approval instead of mistrustful scorn. Arus’s siblings were too young to sit quietly through any long religious ceremony and had been left in the care of palace nannies, but he was old enough to observe ceremonies. Not join them. Yet. Maybe. Arus had yet to show definitive proof that he had inherited his mother’s gift.

Sehmket walked between an entourage of priests and priestesses, their feathered staffs and leopard robes penning her in as she performed her role. Small statues of the deities were carried before and behind her, and a cloud of incense clouded her. Inside the temple the statues were milky stone, but when the procession exited into the afternoon sun of the courtyard, sharp light reflected off of the translucent quartz of the gods and the crushed mica of the priestly face paint. Each quartz statue of a god, goddess, or divine beast was carried on a bronze platter by an attendant priest or priestess, except for one. Two strong priests carried the litter bearing the largest of the holy statues, that of the winged warrior magician goddess O-sesmiat-et. Supposedly it was a replica of the main statue at the furthest altar of the temple, the one that only Ganreh and the Head Priest and Priestesses attended. The winged goddess with her tall crown had a carved face that mimicked the faces of the stone lions but whose expression remained fathomless. Arus wondered who carved the image of the goddess, the only statue chiseled from precious blue stone instead of semi-transparent quartz. Privately he thought that the craftsman was not as skilled as Abidus or Senos-se, the names carved on the heel of the guardian lion statues. A large fan of dropping white feathers angled to further shade the pair of litter bearers of O-sesmiat-et from the sun, but the fan bearer was a short apprentice that struggled to keep the correct angle. In the morning the apprentice had no difficulty with his task, but hours later the heat was affecting him. The two stout litter bearers seemed not to mind, but surely their shoulders ached by now.

In their own way the marching priests were as impressive as the soldiers drilling in the royal barracks.

Arus waved at his mother each time that the ritual brought her to the outer temple courtyard with its stone lion guardians. A silent wave, for the boy was mindful not to interrupt the chanting prayers of the priests and priestesses. Each time a small smile graced his mother’s thin lips. She would not wave back, as that would be unbecoming of dignity and disrupt the careful folds of the heavy cloak around her body and the long train that dragged behind her, the many gemstones and painted feathers that decorated her singular regalia scooting along after each small gliding step that Sehmket took to preserve the illusion that she was gliding like a windborn barque across the giant sandstone paving stones, her feet hidden by reed-thin folds of a long linen shift. Dressing his mother in her ceremonial regalia and laundering the expensive garments required the skills of two priestesses that focused on nothing else but the special garments of the highest priesthood and Arus’s mother. That Sehmket was mindful of her duties was a great irony, for she had a pivotal role in the assassination of the previous high priest and the uncovering of the great conspiracy among the temples and the altering of religious teachings.

The long six-day ceremony was one of the results of the purging and purification of the faith, to restore old ceremonies and old rituals of performing them. How Sehmket was included in them was not an old process restored, though the chant was something transcribed off of a once-forgotten and half-buried tomb wall dating back two dynasties. The priesthood enthusiastically searched for the old methods to honor the gods, eager to reform the lies of their forebears and restore trust in the gods and their chosen representatives. Arus’s mother was the lynchpin to their efforts, however uneasy the truth of the alliance.

His mother was no prisoner, however much Arus sometimes felt that she might be, but he knew that the trust given to Sehmket was conditional. Revered asset instead of hounded traitor, but he was old enough to understand the looks that others bestowed upon his mother, from priest and noble down to the day-laborers of the city. Awe and fear, and the cautious pride that one gave to a tamed hunting cheetah.

A woman that could transform herself into a divine sphinx would always inspire fear.

The first statue in the procession was the only one carved after Arus’s birth, the newest and the only without a holy name. It was of the sphinx, winged cat with the face and chest of a woman. The rosettes of the body had been carefully chiseled, and that was how Arus knew the statue represented his mother’s divine transformation, even though the statue’s nondescript face had closed eyes and full lips. And large breasts. The old artistic representations of sphinxes on the wall reliefs of the main palace, temples, and tombs had lion bodies - all but one painting in the palace complex that dated back to the first dynasty. Prince Hama discovered the painting of the spotted sphinx and had artisans reproduce it across the kingdom. The Master of Scribes bragged that the revived old sphinx design was the most popular tapestry sold throughout the eight cities. Mehbebli was more honest with Arus, explaining that the true sphinx was seen as the most fitting burial shroud for fallen soldiers, in honor of his mother’s divine strength and her efforts to safeguard their kingdom. O-Sehmket transformed had the dappled pelt of a leopard below her waist, of fur the palest gold and darkest bronze, and her wings were the bright green of papyrus sedge. The statue did not include the horns, each as green as fresh reeds: two that curved around her ears to rest against her cheekbones like those of a ram and the four that spiraled out like the addax to give the divine beast a crown. Horns were hinted at via a single wavy shape on that old painting. The toll of his mother’s magic weighed too heavily on her health to be used in frivolous displays, but only those new to the capital or as young as Arus’s second sister had never seen the divine sphinx form of O-Sehmket. Two years ago Sehmket had transformed at the great plaza, careful to lessen the divine storm that accompanied her accession, and hovered above the palace walls, all to prove to the ambassador from Kirop that the tales of the divinity that protected the Kingdom of the Glass Mountain was no mere exaggeration.

The old priesthood had branded his mother a monstrous mockery because of the discrepancies in known form. Head Priestess We-se called it yet more proof of how deeply the priesthood had strayed from the strictures established during the reign of the first dynasty. And their foolishness: O-Sehmket guarded the subjects of Prince Hama, frightening his enemies and strengthening his rule, and brought pilgrims to the temples. Only the army loved her more, for the destruction she could wrought and the peace that she brokered with the griffins.

Arus’s mother was no prisoner, for it would be nigh on impossible to imprison a woman that could transform into a giant chimeric beast of divine powers and flight. But their rulers could not afford to lose their leash on Sehmket, too dangerous an enemy and too vital to their safety.

Magical chains were forged, invisible ones crafted by links more precious than metal: lodgings within the palace complex, amnesty for her murders, reforms among the priesthood and the ousting of corrupt ministers, new laws to protect the slaves and widows, the safe borders of the kingdom and the prosperity and happiness of the common subjects, and the preferential alliance with the griffins of the northern mountains. All to hold Sehmket here and summit to the parades around the temple colonnade and transform into the sphinx when demanded.

The strongest chain, Arus knew, was himself and his sisters.

#original fic#my fic#the sphinx's bastard son#took a break from other projects to do something very self-indulgent#this is the other HW AU transplanted to a brand new fantasy setting#early bronze age fantasy silliness instead of llamasward this time#probably only four or five parts to this the story in my head only has one meaty scene#but i like world-building and here's the excuse to dump all the lion-griffin-sphinx-harpy non-dragon magical critter fantasy flavors#wip

12 notes

·

View notes