#eb bartels

Text

Wellesley Writes It: Conversation with Sumita Chakraborty '08 (@notsumatra), author of ARROW

Sumita Chakraborty is a poet, essayist, scholar, and a graduate of Wellesley College, class of 2008. Her debut collection of poetry, Arrow, was released in September 2020 with Alice James Books in the United States and Carcanet Press in the United Kingdom, and has received coverage in The New York Times, NPR, and The Guardian. Her first scholarly book, tentatively titled Grave Dangers: Death, Ethics, and Poetics in the Anthropocene, is in progress. She is Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry at the University of Michigan - Ann Arbor, where she teaches in literary studies and creative writing.

Sumita’s poetry appears or is forthcoming in POETRY, The American Poetry Review, Best American Poetry 2019, the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, and elsewhere. Her essays most recently appear in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her scholarship appears or is forthcoming in Cultural Critique, Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment (ISLE), Modernism/modernity, College Literature, and elsewhere. Previously, she was Visiting Assistant Professor in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, as well as Lecturer in English and Creative Writing, at Emory University.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10, had the chance to chat with Sumita about publishing, reading, and writing. E.B. is grateful to Sumita for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series in the middle of her book debut!

EB: Thank you so much for being part of the Wellesley Writes It series, Sumita! I’m excited to get to talk to you about writing in general, but especially your debut collection Arrow. Can you start off speaking a bit about how this book came about?

SC: Thank YOU so much! This is such a joy.

The book that’s now Arrow went through about seven prior full versions.

EB: Oh my gosh! Wow.

SC: While there’s a lot going on in there, the most fundamental story I wanted to tell was that of the experience of living in the aftermath of severe domestic violence, other entangled forms of assault, and grief (in my case, particularly for my sister, who died in 2014 at the age of 24). The word “aftermath” is a tricky one, because there is no neat and tidy “after” violence or grief, particularly when one considers the varying scales on which various devastations and mournings take place. One of the main narrative arcs of the collection, though, is that of becoming someone who can embrace love and joy and care and kinship even when those concepts have been weaponized or altogether foreclosed for all of one’s childhood and adolescence. And that’s a narrative that requires a sense of an “after” that I am deeply fortunate to have personally experienced. That’s the main tightrope the collection is invested in walking, which forms the through-line around which and with which its other preoccupations and obsessions orbit and collide.

EB: Wow, thank you so much for sharing all that, Sumita. I especially like what you said about the lack of a “neat and tidy” ending -- isn’t that always the case when it comes to writing about things from our own lives? We want real-life closure but sometimes have to settle for just narrative closure instead.

I meant to say also congratulations on the publication of your collection not only in the US but in the UK as well! What was it like to put that version together? The same? Different?

SC: I was wildly lucky in this regard. Some years ago, I published the poem “Dear, beloved” in Poetry, before it was in Arrow—and in fact before this version of Arrow even existed. At that point, the editor of Carcanet reached out to me to say that the press would be interested in bringing out my collection in the UK. I kind of panicked!

EB: I totally would have, too!

SC: As I mentioned, there was no Arrow yet. I was on a much earlier version that was “complete,” but when I looked at it, I knew: This ain’t it. And querying US presses was therefore not something I was prepared to do at that time; UK publication was even less within the realm of my imagination. I essentially told them the manuscript was in progress and asked if I could reach back out when it was ready and if I had secured a US publisher. Some years later, the collection was picked up by Alice James in the States and I reached back out to Carcanet to see if they were still interested, and they were! Alice James and Carcanet worked together during the production process, so while there were certainly some differences in approaches across either side of the pond, much of it was really streamlined, and that is all thanks to the outstanding and immense labor of the extraordinary editors and staffs at both publishers.

EB: How did you begin writing poetry in the first place? What was your path to becoming a writer?

SC: I didn’t come into much of a sense that I was interested in poetry and in literature until college. When I got there, I didn’t have a sense of really any passions and skills that I had, and that’s not imposter syndrome speaking—it’s because I had a terrible record in high school and found nothing inspirational there, and I was also pretty busy attempting to survive the violence I was experiencing at home and working toward moving out, which I did before college. In my first year and my sophomore fall at Wellesley, I took a really broad smattering of courses, including (with wild, and probably inappropriate, disregard for prerequisites in both cases) Advanced Shakespeare with William Cain and Advanced Poetry Writing with Frank Bidart. I was very much not good enough for both of those courses! But even as I was flailing around in them, something in my mind clicked: this was something I was willing to be terrible at until I started to understand it a bit better. These were puzzles that I liked, questions I liked, problems I cared about dwelling with. It was pretty much “love at first confusion.”

EB: I love that idea: “this was something I was willing to be terrible at.” That 100% nails how I feel about writing, too.

So, obviously, as you just said, Wellesley was very important in your trajectory as a poet -- the title of your book is a reference to a Frank Bidart poem! Which other faculty, staff, fellow students have influenced or inspired you? Are there any professors or classes you would tell young Wellesley writers that they 100% have to take?

SC: Following “love at first confusion,” I essentially made a second home of the first floor of Founders, so my answer to who at Wellesley influenced or inspired me could fill multiple pages!

EB: I love Founders. I miss Founders.

SC: I will invariably accidentally leave someone out and feel guilty, so I offer my mea culpas in advance. In addition to Bill Cain and Frank Bidart, I am beyond grateful to Dan Chiasson, with whom I worked on both my literary studies (including my thesis) and my poetry, and who graciously offered me more mentorship than I’d ever experienced in my life before that point; to Kate Brogan, from whom I got the bug for twentieth-century poetics, which remains the focus of my literary studies research; to Yoon Sun Lee, who taught the theory class when I took it, and planted a hugely important seed that I didn’t even know had been planted until much later simply by being a brilliant Asian American literary scholar (not a role I had ever before seen filled by someone of this subject position); to Larry Rosenwald, who was the first person I had ever met in a literary context who both knew that English was not my heritage language and, in his infinite and genuine passion for multilingualism, viewed that fact as a strength.

I wish I’d had more of a chance to get to know my peers while actually at Wellesley—my life circumstances while I was in college differed from the typical Wellesley experience in ways that made doing so challenging (for one, I worked multiple jobs the entire way through), but I’ve gotten to better know many people I knew at Wellesley more in the years since and that’s been a wonderful experience.

EB: I’ve also made a lot of Wellesley friends post-Wellesley. The Wellesley experience never ends, in that way.

SC: Since I’ve already spoken to the coursework that inspired me, I’m going to zig a bit where your last question zags: there isn’t a single course I would tell young Wellesley writers or literary enthusiasts that they 100% have to take. I don’t think one could go wrong with anyone I’ve named here (and I’ve been really excited to learn about the new additions to the English department: I would have loved to have learned from Cord Whitaker and Octavio González, and have heard wonderful things about both!). But I think that what made the Wellesley experience truly influential for me was that I had the opportunity, like Whitman’s “Noiseless Patient Spider” (though, um, not very noiselessly or patiently), to “launch’d forth filament, filament, filament,” and really listen to what spoke to me. I came in with no preconceptions, no expectations, no firm career plan (or even career plan). Knowing what undergraduates at environments like Wellesley frequently pressure themselves or feel pressured to do (or achieve or produce or attain), I don’t want to offer advice along the lines of a “must-do.” Rather, try things out and truly listen to yourself. What’s your “love at first confusion”?

EB: I know from personal experience that writing can be a really lonely practice. Who did you rely on for support during those really frustrating writing moments? Other writers? Your spouse? Friends? Fellow Wellesley grads? What does your writing/artistic community look like?

SC: All of the above! The thing is, for me, I don’t think writing is a lonely practice. When I feel most energized about writing, it is because I feel like I am in a conversation—or, to put a finer point on it, when I’m in a conversation that is nestled within hundreds of thousands of other conversations that have happened for millennia, are currently happening all around me, and will continue to happen after I’m a hunk of dirt. Tapping into that is often what brings me to the page in the first place.

EB: That’s such a good point.

SC: So when students, for example, feel really isolated or alone in their writing life, my first recommendation is to remind themselves of their beloveds. These may be actual living ride-or-die humans in their lives; these may be ghosts of writers and artists past that are important to them; they might be their most frequently bustling group text or their favorite TV show. Honestly, if one’s thinking of this question as broadly as I recommend, those beloveds probably belong to all of the above categories, to some degree. When you write, even if none of these beloveds are your subject or your audience or anything quite that easily analogous to the process, they are with you, and they have formed who you are before you’ve even picked up a pen or turned your computer on, so they are with you when you are writing, too.

EB: What is it like to now be teaching poetry to undergrads? Are you channeling your inner Dan Chiasson?

SC: Ha! Thank you for that—I just got a visual of myself trying to go as Dan for Halloween and I cracked myself up. (Dan, if you’re reading this: sorry!) I teach undergraduates and graduate students at Michigan, both in literary studies and in creative writing, and I love it very, very much. My students of all levels are brilliant, thoughtful, curious, and wildly imaginative people who often help bolster my faith in the ongoing importance of literary work. Honestly, particularly during this year, I have frequently been in awe of my students and have felt overwhelmingly lucky to be able to work with them.

EB: I know that you are also currently working on your first scholarly book, Grave Dangers: Death, Ethics, and Poetics in the Anthropocene. How do you approach writing poetry vs. writing an academic work? How is your creative process similar or different?

SC: For me the two have been inseparable since Wellesley. I essentially ask similar questions and have similar preoccupations no matter what genre I write; in terms of deciding which thought belongs to which genre, or which project a particular moment is better suited to, that’s often a matter of thinking carefully of what shapes that I want the questions to take, and what kinds of “answers”—in quotation marks because I don’t strive at certainty or mastery in either genre, or in anything for that matter—for which I imagine reaching or searching. For me, the processes for writing both are very, very similar: I draft wildly and edit painstakingly. It’s more a matter of closely listening to my patterns of thinking on any given subject or day in order to find out if the rhetorical patterns of academic prose would better suit them or if the rhetorical patterns of poetry would better suit them.

EB: What are you currently reading, and/or what have you read recently that you’ve really enjoyed? What would you recommend to read while we (are continuing to) lay low during this pandemic?

SC: 2020 was such an incredible year for books! Which feels somewhat perverse to say, considering everything else was dismal and it was hardly an easy year to put out a book, either. In terms of new poetry releases—and this is not a comprehensive list, so my mea culpas here too to the many that I have loved and will end up accidentally leaving off—I have this year read and loved: Taylor Johnson’s Inheritance, francine j. harris’s Here is the Sweet Hand, Craig Santos Perez’s Habitat Threshold, Jihyun Yun’s Some Are Always Hungry, Eduardo Corral’s Guillotine, Rick Barot’s The Galleons, Jericho Brown’s The Tradition, Shane McCrae’s Sometimes I Never Suffered, Victoria Chang’s Obit, Danez Smith’s Homie, Aricka Foreman’s Salt Body Shimmer, and Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem. Two prior-to-2020 poetry collections that I reread every year are Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s Song and Lucille Clifton’s The Book of Light. I’m currently reading Claudia Rankine’s Just Us and Alice Oswald’s Nobody.

EB: Also what about Lucie Brock-Broido? I know she was a teacher of yours at one time, and she was a professor in my MFA program. I had the pleasure of once sitting in on her lecture, and it was life-changing. Are there any particular poems of hers you would suggest?

SC: I joined Lucie’s summer workshop held at her home in Cambridge, MA the summer after my sophomore year at Wellesley, and I stayed in it until I moved to Atlanta for graduate school in 2012. “Life-changing” is right—in fact, it feels a little too modest. She was transformative. A cosmos-realigner. A hilarious, brilliant, extraordinarily kind meteor. A fox with wings. A unicorn. I could go on, and on. For a reader new to her work, I’d recommend starting with her posthumously published “Giraffe” in The New Yorker. I think “A Girl Ago” and “You Have Harnessed Yourself Ridiculously to This World” from Stay, Illusion (2015) are also remarkable entry points. After that, I would probably recommend reading her collections in this order: first Stay, Illusion; then A Hunger (1988); then The Master Letters (1997); and finally Trouble in Mind (2005). The sequencing here isn’t intended as a ranking in the least—my own personal favorites toggle back and forth depending on where my own “trouble in mind” lives, and each collection is dazzlingly strong and has its own raison d’être—but rather because I think the story those collections tell in that order would let a new reader have a full sense of Lucie’s poetics outside of the story that mere chronology can tell.

EB: Any advice for aspiring young poets?

SC: Filament, filament, filament. Let your writing life be as huge and wild and disparate as the whole person you are—don’t feel like there’s only a part of you that’s “worthy of poetry,” and don’t let anyone else tell you what kind of writer you should or shouldn’t be.

EB: Thank you, Sumita! That was wonderful.

#wellesley writes it#wellesleywritesit#wellesley#wellesley underground#wellesleyunderground#sumita chakraborty#eb bartels#e.b. bartels#class of 2008#class of 2010#poet#poetry#writer#writers

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: Liz Scott

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: Liz Scott

For the full interview, see it on Fiction Advocate.

Published on February 11, 2020.

—

Liz Scott is the author of This Never Happened: A Memoir and Lies: The Truth about the Self-Deception That Limits Your Life. Her essays have been published on The Millions, the Powell’s Book Blog, and The Next Best Book Blog, and her fiction piece “Solstice” was the winner of the 2018 Berkeley Fiction Review Sud…

View On WordPress

#2020#author#authors#book#books#Brian Hurley#clinical psychologist#creative non-fiction#creative nonfiction#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#Elizabeth Scott#Fiction Advocate#licensed clinical psychologist#Lies: The Truth about the Self-Deception That Limits Your Life#Liz Scott#memoir#memoirs#non-fiction#Non-Fiction by Non-Men#nonfiction#OR#Oregon#Portland#Powell&039;s Book Blog#Solstice#The Millions#The Next Best Book Blog#This Never Happened#winner of the 2018 Berkeley Fiction Review Sudden Fiction contest

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I decided that I would do a weekly recap, and link up with The Sunday Post, which is a weekly meme hosted by Kimba @ hosted by Caffeinated Book Reviewer, that was inspired in part by In My Mailbox. It’s a post to recap the past week, showcase books and things we have received and share news about what is coming up for the week on our blog.

The past couple weeks have been pretty much the same. However, they’ve also been pretty busy. Last weekend I attended AMC Theater’s annual Best Picture Showcase. Like last year, my friend and I decided to do the two-part viewing instead of the 24-hour. We’re just too old to hang, and that’s way too much sitting. The first Saturday we watched The Phantom Thread, Lady Bird, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, and The Shape of Water. My favorite was Three Billboards, followed by Lady Bird. The other two were just weird, though beautiful in their own way and well acted.

During the week, work was very busy. I had to finish report cards since the grading period ended. I also had to get the kids prepared for a field trip this Wednesday, and parent conferences this week. Then on Thursday, we had a Lockdown Drill focused on an active shooter on campus. Fun! There’s nothing like terrifying 1st graders into being silent while admin bangs on doors and try to get into the classroom. Friday was Read Across America Day, so my little people and I did loads of Dr. Seuss themed activities. It was a crazy, but fun day.

Yesterday was part-two of the AMCBPS. I finally got a chance to see Dunkirk, The Darkest Hour, Call Me By Your Name, and The Post. The final film of the night was Get Out, but I’ve already seen it, and it’s currently on HBO so I decided to leave early for home. I could have stayed as I actually liked that film, but since I slept through much of The Post, it just didn’t make any sense to stay. Staying up super late reading the night before a movie marathon wasn’t the smartest decision I made all week. Instead, I drove home without eating dinner, crawled in the bed, and fell asleep.

Predictions

Best Picture: Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Best Actor: Gary Oldman, Darkest Hour

Best Actress: Francis McDormand, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Supporting Actor: Sam Rockwell, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Supporting Actress: ?

Directing: Jordan Peele, Get Out

Cinematography: Dan Laustsen, The Shape of Water

Music: Alexandre Desplat, The Shape of Water

book haul

last 2 weeks on the blog

[wrap-up-posts week=”7″ year=”2018″ listtype=”ul”]

[wrap-up-posts week=”8″ year=”2018″ listtype=”ul”]

this week on the blog

Book Review: Iron Gold (Red Rising #4) by Pierce Brown

Top Ten Tuesday: Favorite Book Quotes

Book Review: Mr. Murder by Dean Koontz

Book Review: Bennett (The Uncompromising Series) by Sybil Bartel

THE WEEKs IN REVIEW: "And the Winner Is... Pt. 2" (FEBRUARY 18TH – March 3) #TheSundayPost #SundayPost #AMCBPS I decided that I would do a weekly recap, and link up with The Sunday Post, which is a weekly meme hosted by Kimba @ hosted by

0 notes

Text

February 17 in Music History

1444 Birth of Dutch organist Rudolph Agricola aka Roelof Huysman.

1652 Death of Italian priest, singer, and composer Gregorio Allegri.

1653 Birth of Italian composer Arcangelo Corelli in Fusignano near Milan.

1654 Death of composer Michael Lohr, at age 62.

1667 Birth of German composer Georg Bronner.

1675 Birth of German composer Johann Melchior Conradi.

1696 Birth of composer Baron Ernst Gottlieb.

1697 Birth of French composer Louis-Maurice de La Pierre.

1728 FP of G. F. Handel's opera Siroe, re di Persia 'Cyrus, King of Persia' at the King's Theater in the Haymarket, in London.

1732 Death of French organist and composer Louis Marchand.

1747 Birth of Spanish composer Narciso Casanovas.

1751 Birth of tenor and composer Domenico Mombelli in Villanova.

1754 Birth of Czech composer Jan Jachym Kopriva.

1792 FP of F. J. Haydn's Symphony No. 93. Was conducted by Haydn at the Hanover-Square Concert Rooms in London.

1796 Birth of Italian composer Giovanni Pacini in Catania.

1807 FP of Etienne Mehul's opera Joseph in Paris.

1813 Birth of baritone Giovanni Belletti in Sarzana.

1815 Death of composer Franz Gotz, at age 59.

1816 Birth of composer Friedrich Wilhelm Markkula.

1820 Birth of French composer Henri Vieuxtemps, in Verviers, Belgium.

1831 Birth of composer Francisco Salvador Daniel.

1841 Death of Italian composer and guitarist Ferdinando Carulli.

1847 Birth of soprano Mathilde Mallinger in Agram.

1850 Birth of German composer Anton Urspruch in Frankfurt Germany.

1855 Birth of baritone Antonio Magini-Coletti in Ancona.

1855 FP of Franz Liszt's Piano Concerto No. 1 in Eb. Liszt was soloist with Hector Berlioz conducting in Weimar.

1856 Death of English composer and tenor John Braham, in London.

1858 Birth of conductor and composer Ernest Ford.

1859 FP of Verdi opera Un Ballo in Maschera, based on the murder of Gustavus, King of Sweden, at the Teatro Apollo in Rome.

1860 Birth of baritone Max Dawison in Schwedt.

1862 Birth of English composer Edward German.

1862 Death of mezzo-soprano Ann Maria Tree.

1870 Birth of soprano Riza Eibenschutz in Budapest.

1882 Birth of German composer Kurt Schindler.

1883 Death of French guitarist and composer Napoleon Coste, at age 76.

1884 Birth of German-American conductor Hans Lange.

1887 Birth of Finnish composer Leevi Madetoja in Oulu.

1887 Birth of bass-baritone Wilhelm Rode in Hanover.

1889 Birth of English composer and conductor Geoffrey Toye in Winchester.

1889 FP of Cesar Franck's d minor symphony, in Paris.

1896 Birth of mezzo-soprano Gertrud Wettergren in Esloev, Sweden.

1900 Birth of soprano Oxana Petrusenko in Kharkiv.

1901 FP of Mahler's Das Klagende Lied, in Vienna.

1901 Death of American composer and pianist Ethelbert Woodbridge Nevin.

1902 Birth of soprano Leila Ben Sedira in Algeria.

1903 Death of Welsh composer Joseph Parry, at age 61 in Penarth, England.

1904 FP of Puccini's Madama Butterfly, at La Scala in Milan.

1906 Birth of composer and violinist Ramon Tapales.

1909 Birth of Australian operatic soprano Marjorie Lawrence.

1910 Birth of composer Alfred Mendelsohn.

1913 Birth of Polish-French conductor and composer Rene Leibowitz.

1914 FP of Ernst von Dohnányi's Variations on a Nursery Song for piano and orchestra. The composer was soloist in Berlin.

1915 Birth of composer Homer Keller.

1920 Birth of American composer Paul Felter in Philadelphia, PA.1920 Death of baritone Karel Kral.

1924 Death of Finnish composer Oskar Merikanto at age 55 in Hausjärvi-Oiti.

1925 Death of soprano Alwina Valleria.

1926 Birth of American pianist and composer Lee Hoiby in Madison, WI.

1926 Birth of Austrian Avant-garde composer Friedrich Cerha in Vienna.

1927 FP of Deems Taylor's opera The King's Henchmen at the Metropolitan Opera in NYC.

1929 Birth of composer Eugene V. Hancock.

1930 Death of mezzo-soprano Louise Kirkby-Lunn.

1933 Death of Dutch composer and conductor Henri Viotta.

1943 FP of Aaron Copland's Music for Movies. Town Hall Forum concert in NYC.

1944 Birth of Dutch cellist Anner Bylsma.

1944 Birth of Welsh composer Karl Jenkins.

1944 Birth of soprano Ellen Shade in New York City.

1947 FP of Aaron Copland's orchestral Danzón Cubano. Baltimore Symphony.

1948 FP of David Diamond's Violin Sonata No. 1. Joseph Szigeti, violin and Josef Lhevinne, piano at Carnegie Hall in NYC.

1949 Birth of English composer Fred Frith in Heathfield.

1950 Death of soprano Anna Bartels.

1951 Death of composer Nikoghayos Fadeyi Tigranyan.

1952 FP of H. Henze's opera Boulevard Solitude.

1955 Death of Hungarian-American musicologist Otto J. Gombosi, at age 52.

1959 Birth of American composer Robert Scott Thompson in CA.

1961 FP of Elie Siegmeister's Flute Concerto, in Oklahoma City, OK.

1962 Death of conductor Bruno Walter at age 85 in Beverly Hills, CA.

1970 Death of American composer and film conductor Alfred Newman.

1972 Death of Russian composer Gavril Nikolayevich Popov.

1973 Birth of American composer Michelle McQuade Dewhirst.

1974 Death of mezzo-soprano Conchita Velasquez.

1977 FP of Elliott Carter's A Symphony of Three Orchestra. New York Philharmonic, Pierre Boulez conducting.

1982 FP of George Perle's Ballade for piano. Richard Goode, piano at Alice Tully Hall in NYC.

1983 Death of bass Tancredi Pasero.

1991 Death of soprano Gitta Alpar.

1995 Death of soprano Uta Graf.

1999 Death of soprano Sabine Hass.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wellesley Writes It: E.B. Bartels ’10 (@eb_bartels) on financial privilege and writing

From the new series on Fiction Advocate --

How I Got Here: You Learn, I Pay

Privilege is a topic that doesn’t always receive the subjectivity and nuance it deserves. In “How I Got Here,” writers reflect on their experience of privilege (or lack thereof) in their writing careers. We hope these personal essays will help us appreciate the complexities of individual experience and view each other in a clearer light.

An MFA is a shot in the dark. It is a degree that costs thousands and thousands of dollars to pursue and yet has absolutely zero (0) guarantee of any type of employment. You get an MFA out of sheer love or delusion. When I applied to writing programs in the fall of 2011, I did so simply because I knew I loved writing and wanted to get better at it. I also applied because I had, and have had for my entire life, my own personal patrons of the arts.

There have been many calls lately for writers and artists to be more transparent about their financial situations, from the Twitter hashtag #PublishingPaidMe to essay collections to this very series. I remember when I first read Ann Bauer’s essay on Salon about how her heart surgeon husband “sponsors” her writing career and how much I appreciated her honesty. So, let me lay it all out there for you. When it comes to education, the rule in my family is: they pay, no questions asked. It’s like that scene in The Sopranos, when Meadow’s boyfriend tries to pay for Tony’s dinner and Tony is pissed. But instead of “You eat, I pay,” it’s: “You learn, I pay.”

Education has always been a big deal in my family. Both of my parents have Master’s degrees, my mother’s specifically in Music Education, which she used as a piano teacher. Both of my grandmothers achieved higher ed degrees at a time when it wasn’t common for women to even complete high school. My paternal grandfather nearly completed a PhD from MIT in engineering (everything but the dissertation); my maternal grandfather dropped out of law school, but he did so to take over a local driving school because he loved to teach kids how to use cars. Classes, studying, learning, teaching, books—I was taught that these were the most valuable types of currency. I knew from a very young age that there were limits to what I was allowed to ask for in a toy store or a clothing boutique, but the local bookstore? The word “no” did not exist there. In middle school, I memorized my dad’s credit card number so I could order books on the Barnes & Noble website without bothering him (so advanced for 1998!), and he never questioned what I was buying, as long as it was books. He also never questioned how much I was buying because he had access to that other, more literal type of currency—money.

Read the rest of the essay on Fiction Advocate.

#eb bartels#e.b. bartels#wellesley#wellesleyunderground#wellesleywritesit#wellesley writes it#writing#the writing life#money#financial privilege#transparency#fiction advocate#how I got here#you learn I pay

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

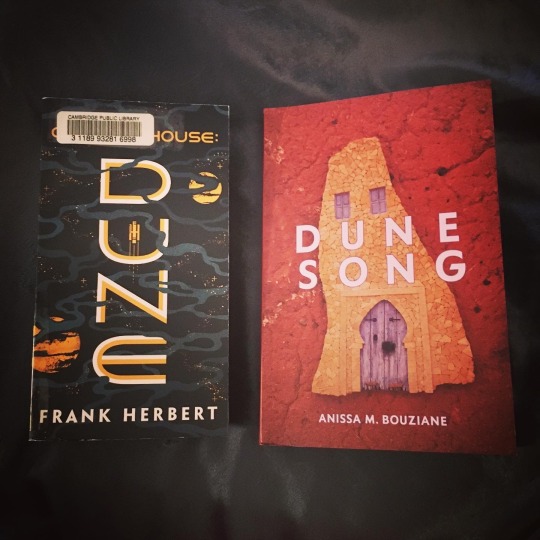

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 (@AnissaBouziane), author of DUNE SONG

Anissa M. Bouziane ’87 was born in Tennessee, the daughter of a Moroccan father and a French mother. She grew up in Morocco, but returned to the United States to attend Wellesley College, and went on to earn an MFA in fiction writing from Columbia University and a Certificate in Film from NYU. Currently, Anissa works and teaches in Paris, as she works to finish a PhD in Creative Writing at The University of Warwick in the UK. Dune Song is her debut novel. Follow her on Twitter: @AnissaBouziane.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10 (who also got her MFA in writing from Columbia, albeit in creative nonfiction), had the chance to chat with Anissa via email about Dune Song, doing research, publishing in translation, forming a writing community, and catching up on reading while in quarantine. E.B. is especially grateful to Anissa for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series while we are in the middle of a global pandemic.

And if you like the interview and want to hear more from Anissa, you can attend her virtual talk at The American Library tomorrow (Tuesday, May 26, 2020) at 17h00 (Central European Time). RSVP here.

EB: First, thank you for being part of this series! I loved getting to read Dune Song, especially right now with everything going on. I loved getting to escape into Jeehan’s worlds, though sort of depressing to think of post-9/11-NYC as a “simpler time” to escape to. My first question is: Reading your biography, I know that you, much like Jeehan, have moved back and forth between the United States and Morocco––born in the U.S.A., grew up in Morocco, and then back to the U.S.A. for college. You’ve also mentioned elsewhere that this book was rooted in your own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. How much of your own life story inspired Dune Song?

AMB: Indeed, Dune Song is rooted in my own experience of witnessing the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. As a New Yorker, who experienced the tragedy of that now infamous Tuesday in September almost 19 years ago, I would not have chosen the collapse of the World Trade Center as the inciting incident of my novel had I not lived through those events myself. So yes, much of what Jeehan, Dune Song’s protagonist, goes through in NYC is rooted in my own life experience. Nonetheless the book is not an autobiography — I would consider it more of an auto-fiction, that is a fiction with deep roots in the author’s experience. The New York passages speak of the difficulties of coming to terms with the tragedy that was 9/11 — out of principle, I would not have chosen 9/11 as the inciting incident of my novel if I did not have first hand experience of the trauma which I recount.

EB: Thanks for saying that. I feel like there is a whole genre of 9/11 novels out there now and a lot of them make me uncomfortable because it feels like they are exploiting a tragedy. Dune Song did not feel that way to me. It felt genuine, like it was written by someone who had lived through it.

AMB: As for the desert passage that take place in Morocco, though I am extremely familiar with the Moroccan desert — and have traveled extensively from the dunes of Merzouga to the oasis of Zagora — this portion of the novel is totally fictional. That being said, I am one of those writers who rides the line between fiction and reality very closely, so if you ask me if I ever let myself be buried up to my neck in a dune, the answer would be: yes.

EB: How did the rest of the story come about? When and how did you decide to contrast the stories of the aftermath of 9/11 with human trafficking in the Moroccan desert?

AMB: Less than six months after 9/11, in March of 2002 I was invited back to Morocco by the Al Akhawayn University, an international university in the Atlas Mountains near the city of Fez. There I gave a talk which would ultimately provide me with the core of Dune Song: the chapter that takes place in the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, where following a mass in commemoration of the victims of the 9/11 attacks, an Imam from a Mosque in Queens was asked to recite a few verses from the Holy Quran. The Moroccan artists and academics present that day were deeply moved by my talk (which in fact simply recounted my lived experience); they told me that I should turn my talk into a novel. I thought the idea interesting and began to write, but within a year the Iraq War was launched and suddenly a story promoting dialogue and mutual understanding between the Islamic World and the West seemed to interest few, so I moved on to other things. Nonetheless, the core of Dune Song stayed with me.

Years later, as I re-examined that early draft, I realized that if I was to turn it into a novel, it had to transcend my life experience — and that is when I turned to my knowledge of the Moroccan desert and my longstanding interest in illegal trafficking across the Sahara desert. I returned to Morocco from the USA in 2003 thanks to Wellesley’s Mary Elvira Stevens Alumnae Traveling Fellowship to research what will soon be my second novel, but truth be told I got the grant on my second try. My first try in the mid-90s had been a proposal to explore the phenomenon of South-North migration across the Sahara and the Mediterranean. I remained an active observer of issues around Trans-Saharan migration, but I went to the desert three or four times on my return to Morocco before I understood that this was where Jeehan too must travel. My decision to bring Jeehan there probably emanated out of the serenity that I experienced when in the desert, but if Dune Song was to be more than just a cathartic work, I realized it should also attempt to draw a cartography of a better tomorrow — and so Jeehan would have to go to battle for others whose fate was in jeopardy because of a continued injustice overlooked by many. It seemed clear to me that Jeehan’s path and those of the victims of human trafficking had to cross. Her quest for meaning in the wake of the 9/11’s senseless loss of life depended on it.

EB: I really loved the structure of the book––the braided narratives, moving back and forth between New York and Morocco. How did you decide on this structure? And how and why did you choose to have the Morocco chapters move forward chronologically, while the New York chapters bounce around in time? To me it felt reflective of the way that we try to make sense of a traumatic event––rethinking and obsessing over small details, trying to make sense of chaos, all the pieces slowing coming together.

AMB: Fragmented narratives have always been my thing, probably because, as someone who straddles many cultures and who feels rooted in many geographies, I felt early on that fragmented forms leant themselves to the multi-layered stories that emanated out of me. My MFA thesis was an as-yet-unpublished novel entitled: Fragments from a Transparent Page (inspired by Jean Genet’s posthumous novel). Even my early work in experimental cinema was obsessed with fragmentation — in large part because I believe that though we experience life through the linear chronology of time, we remember our lives in far-less linear fashion. I agree with you that trauma further disrupts our attempts at streamlining memory. The manner in which we remember, and how the act of remembering — or forgetting — shapes the very content of our memory is essential to my work as a novelist, for I believe it is essential to our act of making meaning of our lived experience.

In Dune Song the reader watches Jeehan travel deep into the Moroccan desert. We also watch her remember what has come before. And we witness her struggle with her memories, which is why the New York chapters bounce around in time. The thing she is frightened of most — her memories of seeing the Towers crumble, knowing countless souls are being lost before her eyes — this she cannot remember, or refuses to remember clearly. And it is not until she is in the heart of the desert and is confronted with the images of the collapse of the WTC as beamed through a small TV screen in Fatima’s kitchen, that she takes the reader with her into the recollection of that trauma. Once that remembering is done, her healing can truly begin — and the time of the novel heads in a more chronological direction.

EB: While this is a work of fiction, I imagine that a significant amount of research went into writing this book, especially concerning the horrors of human trafficking. What sorts of research did you do for Dune Song?

AMB: As I mentioned earlier, beginning in the mid-nineties, the issue of human trafficking across the Sarah became a subject of academic and moral concern to me. But the fact that I grew up in Morocco, and spent many of my summers in my paternal grandmother’s house in Tangier, sensitized me to this topic very early on. Tangier, is located at the most northern-western tip of the African continent, and therefore it is a weigh station for many who aim to cross the Straits of Gibraltar with hopes of getting to Spain, to Europe. I recall a moment when as a teenager I gazed out over the Straits from the cliff of Café Hafa, where Paul Bowles used to write, and imagined that the body of water before me as a watery Berlin Wall. One of my unpublished screenplays, entitled Tangier, focused on the tragedy of those who risked their lives to cross the Straits. So, did I do research to write Dune Song? You bet — I folded into Dune Song topics that had been in the forefront of my consciousness for years.

EB: I know that Dune Song has been published in Morocco by Les Editions Le Fennec, published in the United Kingdom by Sandstone Press, published in France by Les Editions du Mauconduit, and published in the U.S.A. by Interlink Books. What was the experience like, having your book published in different languages and in different countries? Were any changes made to the novel between editions?

AMB: Dune Song was first published in Morocco in an early French translation. Initially this was out of desperation, not choice. I wrote Dune Song in English, and I shopped the English manuscript in the UK and the US to no avail. I was told by people who mattered in literary circles that the book was too transgressive to be published in either the US or UK markets. Suggestion was made to me that I remove all the New York passages from the book if I was to stand a chance of having it hit the English speaking market. I refused to do so and instead worked with my friend and translator, Laurence Larsen to come up with a French version. That being done, I shopped it around in France only to be told that a translation couldn’t be published before the original. Dismissively, I was told to seek-out who might benefit from an author like me existing. The comment hit me like a slap across the face, and I sincerely thought of giving up on the work all together — more than that, I thought I might give up on writing — but my students (who have always been a source of support for me — more on that later) convinced me not to trow in the towel. Once I had the courage to re-examine the question posed to me by the French, I realized that there was a viable answer: the Moroccans. That’s when I contacted Layla Chaouni, celebrated French-language publisher in Casablanca, and asked her if she might want to consider Dune Song for Le Fennec.

Layla’s enthusiasm for the novel marked a huge shift in Dune Song’s fortunes: the book was published in Morocco, won the Special Jury Prize for the Prix Sofitel Tour Blanche, was selected to represent Morocco at the Paris Book fair in 2017, which then lead me (through my Wellesley connections) to gain representation by famed New York literary agent Claire Roberts. It was Claire who got me a contract with Sandstone as well as with Interlink and with Mauconduit — she has been an unconditional champion of my work, and for this I will be eternally grateful. It must be noted that when the book got to Sandstone, I believe it was ‘wounded’ — it had gone through many incarnations, but I was not thrilled with the final outcome. My editor at Sandstone, the fantastic Moria Forsyth gave me the space and guidance to “heal” the manuscript — that is, she identified what was not working and sent me off to fix things, with the promise of publication as a reward for this one last push. The result was the English version that everyone is reading today (published in the UK by Sandstone and in the US by Interlink Publishing). My translator, Laurence Larsen worked diligently to upgrade the French translation for Mauconduit.

It has been a long journey, at times dispiriting, at time exhilarating. I am terribly excited that today, my Dune Song has been published in four countries, and there is hope for more. In the darkest hours of the process, I gave myself permission to give up. “You’ve come to the end of the line,” I told myself, “it’s okay if your stop writing altogether.” In hindsight, hitting rock bottom was essential, because the answer that came back to me was NO. No, I won’t stop writing. I accepted that I might never be published, but I refused to stop writing, for to do so would be to give up on the one action that brought meaning to my life.

EB: You’ve mentioned that Dune Song was originally written in English, though I am guessing, based on your background and reading the book, that you also speak Arabic and French. How and why did you decide to write Dune Song in English? And did you translate the work yourself into the French edition?

AMB: Yes, Dune Song was originally written in English. Though I speak French and Moroccan Arabic (Darija) fluently, my imagination has always constructed itself in English. Growing up in Morocco as of the age of eight, I considered English to be my secret garden — the material of which my invented worlds were made. I had often thought that my return to the United States, at the age of 18 to attend Wellesley, was an attempt to find a home for my words. Even today, living in Paris, I continue to write in English.

I chose not to translate Dune Song into French myself, primarily because my French does not resemble my English — it exists in a different sphere belonging more to the spoken word. I wanted a translator to show me what my literary voice might sound like in French. I have done a fair amount of literary translation, but always from French into English, and not the other way around. Nonetheless, as you rightly noted, I have actively wanted to give my readers the illusion of hearing Arabic and French when reading Dune Song. I like to refer to this as creating Linguistic Polyphony: were the base language (in this case English) is made to sing in different cords. I think my French translator, Laurence Larsen was able to reverse this process and give the French text the illusion of hearing English and Arabic.

EB: In addition to your research, what other books influenced or inspired Dune Song? My fiancé, Richie, happened to be reading the Dune chronicles by Frank Herbert while I was reading your book, and then I laughed to myself when I saw you reference them on page 56.

AMB: The Dune Chronicles, of course! Picture this: a teenage me reading Frank Herbert’s Dune while waiting at the Odaïa Café on the old pirate ramparts of Rabat while my mother was shopping in the medina. I read twelve volumes of the Chronicles. Reading voraciously in English while growing up in Morocco was one of the ways for me to always ensure that my imagination was powering up in English. You’ll note that I give Jeehan this same passion for books. Many of the books that she turns to in her time of need are the books that have shaped who I am and how I see the world: Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Allende’s House of Spirits, Okri’s The Famished Road, Calvino’s The Colven Vicount, Aristotle’s The Poetics, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry…

EB: What are you currently reading, and/or what have you read recently that you’ve really enjoyed? What would you recommend we all read while laying low in quarantine?

AMB: I’m one of those people who reads many books (fiction, non-fiction, and poetry) at the same time. If I look at my night stand right now, here are the titles I see: in English — Hannah Assadi’s Sonora, Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, Du Pontes Peebles’ The Air You Breathe, and Margo Berdeshevsky’s poetry collection: Before the Drought, in French — Santiago Amigorena’s Le Ghetto intérieur, and Mahi Binebine’s La Rue du pardon.

In quarantine, Margo’s poetry has provided me with a level of stillness and insight I did not realize I longed for — and has seemed prescient in its understanding of humanity’s relationship to our planet.

EB: On your website, you mention you are also a filmmaker, an artist, and an educator in addition to being a writer. How do you think working in those other fields/mediums influences your writing? How do you think being a writer influences those other pursuits?

AMB: Writing as an act of meaning making is the mantra I constantly recite to my students. In my moment of greatest despair, they echoed it back to me. Why do I allow myself this type of discourse with my students? Because as a high school teacher of English and Literature, my speciality is the teaching of writing. While at Columbia University, though enrolled in a Masters of Fine Arts in Fiction at the School of the Arts, I had a fellowship at Columbia Teachers College, specifically with The Writing Project lead by Lucy Calkins (today known as The Reading and Writing Project). There I worked as a staff developer in the NYC Public School system and conducted research that contributed to Lucy’s seminal text, The Art of Teaching Writing. Over the years my students have helped me realize why we bother to tell stories and how elemental writing is to our very humanity. I could never divorce my writing from the act of teaching.

Regarding cinema, as I mentioned earlier, my frustration with how to translate multi-lingual texts into one language is what originally drove me to experiment with film. What I discovered as I dove deeper into the medium, was how key images are to the act of storytelling. Once I returned to writing literature, I retained this awareness of the centrality images in the transmission of lived experience. I smile when readers of Dune Song point out how cinematic my writing is — film and fiction should not stand in opposition one to the other.

EB: Writing a book takes a really long time and can be a really lonely and frustrating experience. Who did you rely on for support during the process? Other writers? Family? Friends? Fellow Wellesley grads? What does your writing/artistic community look like?

AMB: It took me over ten years to write and publish Dune Song. The tale of how it came to be is almost worthy of a novel itself. When things were at their most arduous, I went back to reading Tillie Olsen’s Silences, about how challenging it is for women to write and publish — it was a book I had been asked to read the summer before my Freshman year. Though I won’t tell the full story here — I must acknowledge that without the support of my sister, Yasmina, and my parents, as well as essential and amazing women in my life, many of them from Wellesley, Dune Song would never have seen the light of day. Sally Katz ‘78, has been my fairy-godmother, all good things come to me from her, plus other members of the astounding Wellesley Club of France, especially its current president, my dear classmate, Pamela Boulet ‘87. I must thank my earliest Wellesley friend, Piya Chatterjee ’87, who plowed through voluminous and flawed drafts. Karen E. Smith ’87, who reminded me of my creative abilities when I seemed to have forgotten, and who brought her daughter to my London book launch. Dawn Norfleet ’87 who collaborated with me on my film work when we were both at Columbia, and Rebecca Gregory ’87, with who was first in line to buy Dune Song at WH Smith Rue de Rivoli, and Kimberly Dozier ’87, who raised a glass of champagne with me in Casablanca when the book first came back from the printers. The list of those who helped me get this far and who continue to help me as I forge ahead is long - and for this I am grateful… writing is a thrilling but difficult endeavor, and without community and friendship, it becomes harder.

And since the book has been published, the Wellesley community has been there for me in ways big and small, even in this time of COVID. Out in Los Angeles, Judy Lee ’87 inspired her fellow alums to read Dune Song by raffling a copy off a year ago — and now, they have invited me to speak to their club on a Zoom get-together in June!

EB: Speaking of Wellesley, and since this is an interview for Wellesley Underground, were there any Wellesley professors or staff or courses that were particularly formative to you as a writer? Anyone you want to shout out here?

AMB: When a student at Wellesley, a number of Professors where particularly supportive of me and my work. At the time, I was a Political Science and Anthropology major; Linda Miller and Lois Wasserspring of the Poli-Sci department were influential and present even long after I graduated, and Sally Merri and Anne Marie Shimony of the Anthropology department helped shape the way I see the world.

Any mention of my early Wellesley influences must include Sylvia Heistand, at Salter International Center, and my Wellesley host-mother, Helen O’Connor — who still stands in for my mother when needed!

More recently, Selwyn Cudjoe and the entire Africana Studies Department, have become champions of my work. Thanks to their enthusiasm for Dune Song, I was able to present the novel at Harambee House last October and engage in dialogue about my work with current Wellesley students and faculty. This was a remarkable experience which gave me a beautiful sense of closure regarding the ten-year project that has been Dune Song. Merci Selwyn!

I speak of closure, but my Dune Song journey continues, just before the pandemic, thanks to the Wellesley Club of France and Laura Adamczyk ’87, I was able to meet President Johnson and give her a copy of Dune Song!

EB: Is there anything else you’d like the Wellesley community to know about Dune Song, your other projects, or you in general?

AMB: Way back at the start of the millennium, when the Wellesley awarded me the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship, I set out to excavate family secrets and explore the non-verbal ways in which generation upon generation of mothers transmit traumatic memories to their daughters. My research took me many more years than expected, but I am now in the process of writing that novel, along with a doctoral thesis on Trauma and Memory.

In conjunction with this second novel, I am working with Rebecca Gregory ’87, to produce a large-scale installation piece exploring the manner in which the stories of women’s lives are measured and told.

EB: Thank you for being part of Wellesley Writes It!

#wellesley writes it#wellesleywritesit#Anissa M. Bouziane#Anissa Bouziane#class of 1987#EB Bartels#E.B. Bartels#class of 2020#wellesley#wellesley college#Dune Song#France#Morocco#New York#USA#book#books#novel#novels#wellesley '87#wellesley '10

1 note

·

View note

Text

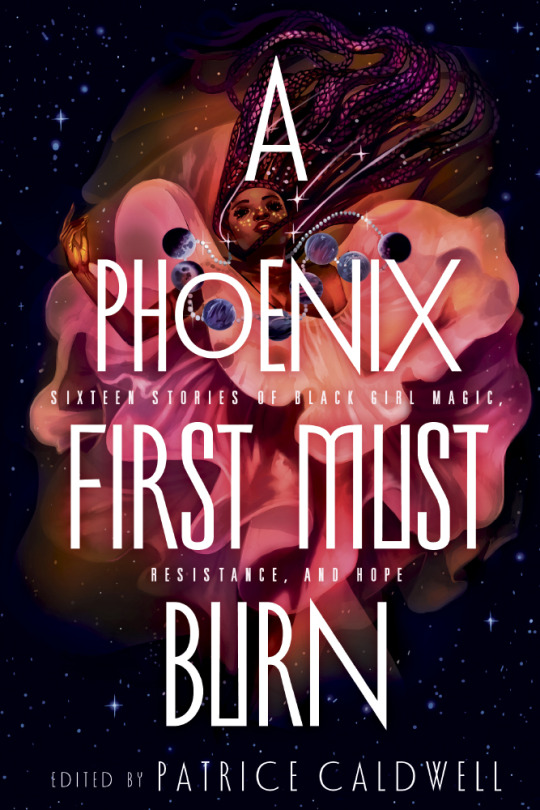

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Patrice Caldwell ’15, Founder of People of Color in Publishing

Patrice Caldwell ’15 is the founder & fundraising chair of People of Color in Publishing – a grassroots organization dedicated to supporting, empowering, and uplifting racially and ethnically marginalized members of the book publishing industry. Born and raised in Texas, Patrice was a children’s book editor before shifting to be a literary agent at Howard Morhaim Literary Agency.

In 2018, she was named a Publishers Weekly Star Watch honoree and featured on The Writer’s Digest podcast and Bustle’s inaugural “Lit List” as one of ten women changing the book world.

Her anthology, A Phoenix First Must Burn – 16 stories of Black girl magic, resistance, and hope – is out March 10, 2020 from Viking Books for Young Readers/Penguin Teen in the US/Canada and Hot Key Books in the UK! Visit Patrice online at patricecaldwell.com, Twitter @whimsicallyours, and Instagram @whimsicalaquarian.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10, had the chance to converse with Patrice via email about publishing, reading, and writing. E.B. is grateful to Patrice for willing to be part of the Wellesley Writes It series, even with everything else she has going on!

EB: When did you first become interested in going into writing and publishing? Did something at Wellesley spark that interest?

PC: For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved writing. It’s how I best express myself. That love pretty naturally grew into creating stories. I’ve always had a very vivid imagination. I’ve also always been pretty aware that publishers exist. I remember at a young age noticing the logos on the spines of books (notating the imprint/publisher), so by the time I was a teen I could recall which publishers published my favorite books (served me very well in interviews, haha) and was curious about that process. But I was a theater kid, intensely, that’s what I thought I would do, but then I decided to go to Wellesley and majored in political science (especially theory—I took ever class Professor Grattan, she’s brilliant) but then dabbled in a bunch of other subjects, including English. I think English courses definitely strengthened my critical thinking, but I absolutely do not think you have to be an English or creative writing major in order to work in publishing or be a writer. My theater background is just as helpful as is my political theory one. (I have friends who are best-selling authors who did MFA programs and others who never went to college.)

Wellesley was my safe space. I came back to myself while at Wellesley. I wrote three (unpublished) manuscripts during my time there, starting the summer after my first year, and I held publishing and writing related internships. I also took a fantastic children’s literature course taught by Susan Meyer (who’s a children’s author herself!) that changed my world. I highly recommend it. We studied children’s literature, got to talk to an author and a literary agent, and we wrote our own stories. I later did a creative writing independent study with her, and I truly thank Professor Meyer for expanding my interest in writing and publishing.

EB: How did People in Color Publishing come about? What goals do you have for the organization? What would you like people to know about it?

PC: I founded People of Color in Publishing in August 2016 to allow people of color clearer access into the book publishing industry, better support networks, and professional development opportunities. It really is about sending the elevator back down for others after climbing (& maybe even assembling) the stairs.

We’re currently working towards nonprofit status. You can learn more about us and our initiatives at https://www.pocinpublishing.com/ and sign up for our newsletter, which is incredibly well done. As you’ll see when you visit the site, the organization really is a team effort. I don’t and couldn’t do this alone; I’ve had an amazing team with me from day one. We each play to our strengths and work really well together. (The org is very active on Instagram and Twitter, too!)

EB: I am really excited about your collection A Phoenix First Must Burn, coming out from Penguin Random House on March 10, 2020. What inspired you to put together that anthology? What was challenging about the process of compiling the anthology, and what was rewarding about it?

PC: Thank you; I’m so excited for it as well. I talk about this more in the book’s introduction, but I was inspired by my eternal love for Octavia Butler—the title even comes from a passage in Parable of the Talents—as well as similar adult market anthologies like Sheree R. Thomas’s Dark Matter, and wondering what one for teens would look like. The answer is power and imagination like I’ve never before seen, in the form of a kick-ass, #BlackGirlMagic anthology that’s hella queer—I love it and wouldn’t have it any other way.

Before I became a literary agent, I was a children’s book editor. The editing of these stories was the easy part. It was super fun. The hard part was wrangling of everyone, haha. Thankfully they were amazing to work with and I wasn’t doing it alone—my then editor Kendra Levin also has a fantastic editorial eye.

As for what was rewarding, my younger self needed this. Like I said, it’s Black and queer. Since Toni Morrison passed, a day hasn’t gone by in which I’ve thought, about how she wrote for Black people, especially Black women, unapologetically. I feel that deeply. I got to work with some of my favorite writers writing today. How often does someone get to say that, you know. And, I grew a lot as a writer. I never thought I could write a short story, but I did. We’ve been getting some really great early reviews (like this beautifully-written starred review from Kirkus, OMG!) But going back to how my younger self needed this, the most rewarding thing has been the people who’ve reached out how excited they are to read it and how much they’ve been craving a book like this. It’s a dream come true. A dream I strategized to reach, worked my butt off on, and so yeah, I’m over the moon.

EB: You're also the author of a YA fantasy book (publication date TBD) in addition to the anthology. How is the experience of writing a fantasy novel different and/or similar to compiling an anthology? What advice would you give to someone writing their own book (of any genre)?

PC: It’s such a different experience in that writing this novel is all me, especially because it hasn’t sold yet (I’m finishing revising it now). My agents are amazing, with an excellent editorial skills, and so they’re certainly there to help and advise me should I need them—and then I have author friends I can ask for advice too—but ultimately if I don’t write this book, it doesn’t get written. There’s no one else to nudge.

The similarities, however, between novels and short stories are that ultimately, I’m the same writer, I’m the same person. For instance, I love experimenting with structure. My story for A Phoenix First Must Burnbegins in the present, goes back in time, and ends again at the present. The story I just wrote, for Dahlia Adler’s Shakespeare-inspired anthology, is epistolary—told partially in journal entries, and my third short story (for an unannounced thing) takes place partially on the set of a scripted reality TV show, so there’s definitely going to be script excerpts throughout. My novel is similar in that it’s told through three women, but two of them are narrated in first present tense (like, I am) whereas one is in third past (she was). And then every few chapters I have an excerpt of something from this fantasy world’s archives—oral myths passed down about various gods, peace treaties made over the years, accounts from the war that just ended, etc. It’s been a huge challenge and lot of fun.

I didn’t have the skills to pull this book off when I started writing it, which is something I think a lot of writers deal with at some point. Therefore, I had two options: put the book down and write something more manageable or take the time it took to write this. Neither option is better than the other—the best option is what’s right for you, and I didn’t have anything more manageable that I was as passionate about, so I had to write through it. When you’ve tried everything you can possibly try (including breaks, they’re important!) to unstick your story, you have to write through it. You have to deal with the voices (including sometimes your own) saying you can’t, and the only way to truly deal with those voices is to show up to the paper, the screen, whatever it is, and write. In writing and believing in my own work before anyone else has, I’ve found my confidence. Confidence in your own writing is key because only you can write the book you want to write <3.

EB: What are you currently reading?

PC: Realm of Ash by Tasha Suri. I just loved herdebut novel, Empire of Sand, and I’m so pumped to be diving into this one. Badass women, incredibly rich worldbuilding, and very cool magic as well as a lot about access to forgotten history and assimilation into other cultures.

My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell. It is getting fantastic early reviews and was pitched as a 21stcentury Lolita (by one of my agents who sold it actually) and given all the #MeToo conversations, it has ended up being super timely. I hated Lolita (could not finish), and I love this book. Oh, and Stephen King loved it, which for me is an auto-buy. It’s out March 10, 2020.

The Midnight Lie by Marie Rutkoski. You definitely don’t have to love someone’s books to be friends with them, but in this case, Marie is a friend whose work I’m obsessed with. It’s set in the same world as another one of her series—one of my favorite series that’s like game theory in a fantasy world and begins with The Winner’s Curse. Marie is brilliant, this book is brilliant, and it’s also very queer. It’s out March 3, 2020.

Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik. This book has been getting the best of reviews and praise, so it’s been at the top of my to-reads list for a while, but I started reading it because a friend mentioned that it has multiple POVs all in first person (which is very unusual), and like I said, I love playing around with stuff like that. This is book is a masterpiece.

As you can tell, I love reading books. I also love book hopping, so I’m always reading a bunch at once. I’m on a bit of a fantasy streak right now. But from October to December 2019 I read like a romance novel a week (sometimes three a week, haha) and revisited my favorite urban fantasy series, so if you’re into those check out Chloe Neill’s Chicagoland Vampires + Heirs of Chicagoland series, Tessa Dare’s Girl Meets Duke series and of course our very own Jasmine Guillory, my favorite of hers thus far is The Wedding Party). After I’m done with my revisions, I wanna take a writing break and sink into Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey and Dan Jones’s The Wars of the Roses: The Fall of the Plantagenets and the Rise of the Tudors.

EB: What future projects/goals do you have for yourself and your career?

PC: I spent most of Wellesley working towards two goals: being published and working in publishing. In doing so, I accomplished a lot in a very short time, and I totally wrecked my mental health—it took most of 2019 to rebuild that. I’m trying to live more in the present and enjoy that. Career wise, I’m just gonna trust that I’m already doing the work I need to do and that I have the support systems I need to help me keep doing that. And for a personal goal, I have been wanting to spend more time in Paris—I went back for the first time in ten years for all of February 2019, and just loved it. My whole soul felt at home, so I’d like to take some French lessons to fill in the gaps (I took French from middle school through sophomore year at Wellesley and achieved proficiency, but I want to become fluent). And then I want to visit more for longer and see where that takes me.

EB: I so admire your freelance hustle, and as someone attempting it myself, too, I know that sometimes it feels like you have to work 24/7 to make it possible. How do you set boundaries for yourself and your work? How do you take care of yourself?

PC: So, I’m a literary agent and a writer, which means my entire income comes from commission I make from the writer client projects I work on and sell as an agent and advance payments (and hopefully royalties down the line) as a writer. That said, I didn’t become a literary agent until June 2019, and didn’t get the first payment from a client book I sold until November, so most my income is still coming from writing (for reference, I received my first advance check in fall of 2018).

As of now, balancing the two isn’t that hard for me. But you have to understand that I was first an editor and a writer, so I had to do most of the deadlines for A Phoenix First Must Burn while also going into an office 5 days a week, from 10-7/8pm. Now, I manage my own schedule.

My main “freelance life” struggle was that I was diagnosed with ADHD this year. When I left my full-time, salaried job, at the end of 2018, I didn’t realize just how helpful that structure had been. To me, that structure was only ever a limitation. I felt like it was ridiculous with all of this technology that we all had to be in NYC, I felt like editors needed to be more proactive, I preferred to travel to book festivals and teach at workshops and meet writers where they are, etc. etc. But then, without that structure, everything fell apart. Suddenly, tasks that used to take me five minutes could actually take me five hours because I only had myself to answer to. I would hyper-focus on everything but what I needed to be doing. It was a really hard time for me because I had all of these things I wanted to do now that I finally had more time to do them, but ADHD had other plans—I constantly felt like I wasn’t achieving what I knew I could because I had done it before.

I had to learn to forgive myself. This is how my brain works, and there are a lot of strengths to it (like if I remove distractions like the internet, I can hyper-focus for hours, I’m a fantastic problem solver, and I thrive in chaos—all things that help me excel at my work). Learning to forgive yourself for not accomplishing all the things, whether you have a mental illness or not, is really important.

You also have to be hyper-aware of your strengths and weaknesses. What are things you know you’re just not good at? Can you pay someone else to do it? Is there an app you can download that can make that task easier? I delegate and outsource every detail-level thing that I can because I’m horrible at details and I’ve finally accepted that that’s okay. One person cannot do everything forever; it’s not sustainable.

And then you also have to say no. If you can afford to say no to something that doesn’t really interest you / have a high payoff, do so. That is how you set boundaries. My health has become so much better ever since I started saying no to more things. Why? It gives me time to do other things, those things I’ve been saying forever I’m going to make more time for (like French lessons and reading books for fun). Now, my evenings and weekends are for non-work things. I love my jobs they’re still jobs.

Trust that you’re on the right path. Trust that you have the support systems you need and if you aren’t or don’t, dream and strategize towards those.

Ultimately, I am the happiest I’ve ever been and that’s because I finally stopped focusing my whole life around my jobs, stopped caring what people who aren’t paying my bills think, and started living my actual life.

EB: What else would you like our readers to know about you and/or your work?

PC: I have a website, Twitter, Instagram, and a newsletter. If you enjoyed this interview, definitely sign up for my newsletter (& check out past issues) as I always give creative life pep talks, share recipes and what books and tv shows I’m loving. I think of my newsletter as a longer form version of my Twitter. My website is a pretty standard website—you can find out more about my own books, my clients, events I’m attending, etc. there. And my Instagram is slightly more personal, with pretty pictures of my face and my book haha, and I share daily/weekly updates about my writing there via IG stories.

And, of course, buy my book: https://patricecaldwell.com/a-phoenix-first-must-burn

Thank you so much for having me and for reading. Happy New Year!

#wellesleywritesit#Wellesley Writes It#Wellesley#Wellesley College#Wellesley Underground#wellesleyunderground#Patrice Caldwell#EB Bartels#E.B. Bartels#class of 2010#class of 2015#Wellesley '15#Wellesley '10#People of Color in Publishing#publishing#writing#people of color#PoC

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Nina MacLaughlin on The Believer Logger!

Interview with Nina MacLaughlin on The Believer Logger!

For the full interview, see it on The Believer.

Published on February 5, 2020.

—

I cannot tell you how excited I am to have an interview with Nina MacLaughlin up on The Believer Logger today. Nina has been a role model and inspiration to me since I first met her in spring 2015, right before the debut of her memoir, Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter. It was such a pleasure to talk to Nina…

View On WordPress

#a very popular $12 magazine#Bojack Horseman#Boston#Cambridge#carpenter#carpenters#carpentry#carving#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#epic poem#Farrar Straus and Giroux#FSG Originals#Hayden Bennett#MA#MacKenzie Wolf#Macmillian Publishers#Massachusetts#Metamorphoses#MeToo#MW Literary#MWLit#Nina MacLaughlin#Noble & Greenough School#Nobles#Nobles grads#Ovid#Ovid Resung#poem#poems

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writers You Should Know: Elizabeth Chiles Shelburne

Writers You Should Know: Elizabeth Chiles Shelburne

Happy publication day to Elizabeth Chiles Shelburne and her beautiful, dark, devastating book, Holding On To Nothing, which is out today from Blair! Everyone go buy a copy and read it right now and I am not just saying that because ECS thanked me in the acknowledgments (my first time ever appearing in book acknowledgments!?!) but that definitely didn’t hurt. 🍾💙✨📚🎉🥃❤️📝💫🖤🍻🥰🍷💚🐕🔫🧡

Congratulations,…

View On WordPress

#badass woman#badass women#Blair#Blair Publishing#book#books#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#Elizabeth Chiles Shelburne#Elizabeth Shelburne#essay#essays#fall#fiction#friend#friends#Holding On To Nothing#novel#novels#Tennessee#woman#woman writer#women#women writers#writer#writers#writing by friends

1 note

·

View note

Text

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: Cameron Dezen Hammon

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: Cameron Dezen Hammon

For the full interview, see it on Fiction Advocate.

Published on October 22, 2019.

—

Cameron Dezen Hammon’s writing has appeared in Ecotone, The Rumpus, The Literary Review, The Houston Chronicle, and elsewhere. Her essay “Infirmary Music” was named a notable in The Best American Essays 2017, and she is a contributor to The Kiss: Intimacies from Writers (W.W. Norton), My Caesarean: Twenty Mothers…

View On WordPress

#2019#author#authors#book#books#Brian Hurley#Cameron Dezen Hammon#Cameron Hammon#Common Prayer#creative non-fiction#creative nonfiction#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#Ecotone#Fiction Advocate#Houston#Intimacies from Writers#Lookout Books#memoir#memoirs#My Caesarean#New York City#non-fiction#Non-Fiction by Non-Men#nonfiction#NYC#podcast#Reflections on Episcopal Worship#stories#story

1 note

·

View note

Photo

BBF Unbound: Creature Feature! Come listen to me talk to some brilliant people about what it's like to write nonfiction about animals at the…

#02119#2300 Washington St#abortion#animal#animals#BBF#BBF 2019#BBF Unbound#book#book festival#books#Boston#Boston Book Fest#Boston Book Fest 2019#Boston Book Festival#Boston Book Festival 2019#Creature Feature#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#Grace Talusan#Jessie Male#MA#Massachusetts#Matthew Gilbert#October 20#Roxbury#Roxbury Innovation Center#Roxbury Innovation Center Multipurpose Room#Sangamithra Iyer

1 note

·

View note

Text

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: T Kira Madden

Non-Fiction by Non-Men: T Kira Madden

For the full interview, see it on Fiction Advocate.

Published on September 24, 2019.

—

T Kira Madden is a lesbian APIA writer, photographer, and amateur magician living in New York City. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College and serves as the founding Editor-in-chief of No Tokens, a magazine of literature and art. A 2017 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in nonfiction literature…

View On WordPress

#2019#APIA writer#APIA writers#author#authors#book#books#Brian Hurley#creative non-fiction#creative nonfiction#E.B. Bartels#EB Bartels#Fiction Advocate#Hedgebrook#lesbian writer#lesbian writers#Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls#magic#magician#magicians#memoir#memoirs#New York City#No Tokens#non-fiction#Non-Fiction by Non-Men#nonfiction#NYC#photographer#photographers

1 note

·

View note

Text

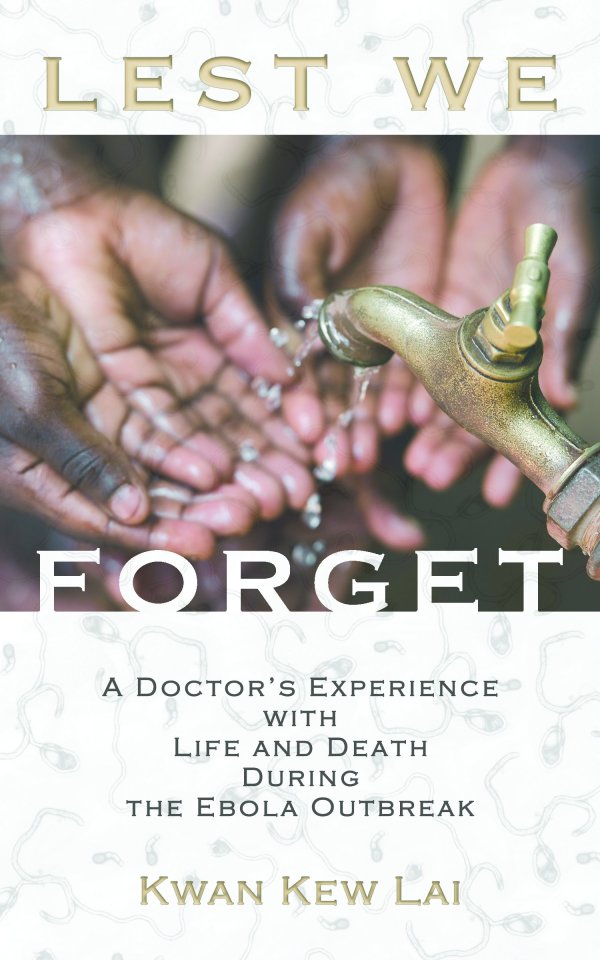

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Kwan Kew Lai ’74 (@KwanKew), infectious disease physician & author of LEST WE FORGET: A DOCTOR’S EXPERIENCE WITH LIFE AND DEATH DURING THE EBOLA OUTBREAK

Kwan Kew Lai ’74, M.D., D.M.D., is an infectious disease specialist who has volunteered her medical services all over the world and the author of Lest We Forget: A Doctor’s Experience with Life and Death During the Ebola Outbreak. In 2004, after the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, she spent three weeks in India, caring for survivors. She soon left her position as a full-time Professor of Medicine in Infectious Diseases and Internal Medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center and created a half-time position as a clinician, dedicating the other half of her time to humanitarian work.

Since 2005, Lai has volunteered as a mentor to health workers addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Vietnam, Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Nigeria, Malawi and has provided earthquake relief in Haiti and Nepal, hurricane relief in the Philippines and drought and famine relief in Kenya and the Somalian border. She has also worked with refugees of the Democratic Republic of Congo and internally displaced people in Libya during the Arab Spring and South Sudan after the civil war and treated Ebola patients in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Most recently, she served as a medical volunteer in the Syrian refugee camps in mainland Greece and in Moria refugee camp on Lesvos, Greece for refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and the countries of the Sub-Saharan Africa and in the world’s biggest refugee camps for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Lai has blogged extensively about her experiences.

Originally from Penang, Malaysia, Lai came to the United States after receiving a scholarship to attend Wellesley, where she studied molecular biology. “Without that open door I would not have gone on to become a doctor,” Lai wrote in her Doctors Without Borders bio.

Lai has received numerous awards for her work, which include being a three-time recipient of the President’s Volunteer Service Award. In 2017, she was awarded Wellesley College Alumnae Achievement Award. In addition, Lai is the lead author of many publications and presentations. Her research has included HIV studies, infection control, hospital epidemiology, and antibiotic trials. She has served on many committees, task forces, and boards, including the Governor’s Advisory Board for the Elimination of Tuberculosis in Massachusetts. She is also an avid marathon runner and paints when she is inspired.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10, had the chance to converse with Lai via email about Lest We Forget and about her experiences at Wellesley and beyond. E.B. would also like to make note that Lai made time to answer these questions even while busy with her 45th Wellesley Reunion!

EB: How did Lest We Forget come about? What inspired you to write the book?

KKL: I first became aware of the Ebola outbreak in March of 2014, I began to follow it very closely. I read about Ebola when I was in my training as an infectious disease specialist. It is a deadly viral infection but it usually occurs in Africa and I knew that it would be unlikely for me to see a patient with this infection. In the summer of 2014 when WHO finally acknowledged the seriousness of the situation, the nightly TV images of people desperate to get into a hospital and bodies lying in the streets because they were too infectious to be touched, moved me. I knew I had to be in West Africa to volunteer.