#especially with the diphthongs

Text

me casually learning modern greek after studying classical greek in college and the pronunciation of everything throwing me for a loop

#especially with the diphthongs#and η like exsqueeze me#dmitrigirl speaks#should i be funny and tag this as langblr#langblr#😎#greek

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

save me will ramos and elizabeth analyze sleep token's "___" react videos .... save me ...

#im fucking obsessed with analysis videos#especially these two they have such good on camera chemistry + great commentary#i now know what a diphthong is#sleep token

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a wild inflectional system. 25 different inflectional paradigms, but only a very small number of actual suffixes, and a mere six cells in the full paradigm. Just different distributions of the same suffixes

With the exception of class XXV, the plural is marked by -ni or -∅, with all three cases having the same two options (there's a predictable allomorph -i for -ni after -l, -n, and -r but this apparently is without exception). Out of the 8 logical possible combinations, there are 6 found (all but -ni/-∅/-∅ and -ni/-ni/-∅), with a very strong tendency (the only exceptions being class XXIV) for -ni to only be used in the nominative plural if it's also used in the other two cases (the author hypothesizes that there were originally two distinct suffixes, one a general plural and the other specifically a genitive/locative suffix, which phonetically merged in an earlier stage - this seems plausible to me and would make sense of the distribution, but it's speculative), so that one can treat 5 of those patterns as "regular" and 2 (classes XXIV and XXV with -ni/-∅/-ni and -∅/-kä/-ni respectively) as irregular

In the singular, while the nominative consistently has no suffix, the genitive and locative have the same three possibilities: -∅, -kä, and -ä, with all but one logical possibility found (none with -ä for genitive and -∅ for locative; given the rarity of the -ä suffix, this is probably an accidental gap; and indeed the relatively small number of nouns in the corpus used makes me wonder if a larger corpus might actually find a noun with that pattern)

In both the singular and plural there's a strong statistical tendency towards using the same suffix (or lack thereof) for both genitive and locative:

In addition, many nouns (the majority in fact) also have stem changes, which can combine with the various paradigms given above, and also show massive numbers of possibilities (48 different patterns according to this paper - the suffix paradigms and stem paradigms combine to make a total of 208 attested patterns among the 252 nouns in this corpus!). Stem alternations can occur between cases and between singular and plural - up to a maximum of five stems! Alternations may involve vowel length, diphthongization, vowel quality, phonation, and stem-final consonants or combinations of these, and even, for number, suppletion

As with the paradigms for suffixes, there are some statistical tendencies. Genitive and locative frequently have the same stem, for example, so that if there's two stems in either number, it's usually going to be nominative vs genitive/locative - but exceptions exist. These stem alternations interact with the various paradigms to some degree in that stem-changes tend to be associated with zero suffixes and lack of stem-changes tends to be associated with overt suffixes (especially strong for number, where there are only two nouns with zero suffixes and no stem change, thus the singular and plural are almost always distinct whether that's from different stems, affixes, or both)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

訓令式(くんれいしき): the kunrei romanization system

i saw people in the japanblr community talking about this recently, so i thought i'd post a quick explanation in case anyone wasn't already familiar with it!

in any case, you've probably noticed that there is not a consensus on how to write japanese using latin letters, whether it's what letters to use, whether to spell out long vowels, or even where to draw word boundaries. nowadays, people (especially non-japanese people) mostly use the hepburn system, which is quite phonetically intuitive. but there's also an older system called the kunrei system (訓令式)

the kunrei system was invented by the japanese government for official usage inside japan in the 1930s. unlike hepburn, kunrei is NOT based on the sounds of the japanese language but rather the strictest interpretation of its syllabic orthography (that is to say, the kana).

to my understanding the kunrei system is still taught in japanese schools, but it definitely feels old-fashioned (it's actually especially common to see in writing by japanese linguists!). you also may have heard that recently the japanese government is changing their official romanization rules, for exactly the reasons that most people prefer the hepburn system, i.e., kunrei doesn't make much intuitive sense compared to the actual spoken language. but it's still useful to be able to read it!

if you're interested, here are the general rules of the kunrei system:

whichever consonant precedes /a/ in the /aiueo/ vowel order, that consonant should precede all the other vowels as well. so, さ is /sa/, and therefore し is /si/. は is /ha/, and therefore ふ is /hu/. わ is /wa/, and therefore を is /wo/.

in words with little ゃゅょ, that whole kana is always spelled out. so しゃしん becomes /syasin/.

the diphthong おう is interpreted as a long お vowel. so とうきょう becomes /tookyoo/. this reanalysis does not happen for the えい diphthong (for some reason?? lol).

here are some wacky kunrei romanizations:

サーシャ → saasya (my name lol)

不可欠(ふかけつ) → hukaketu

手作り(てづくり) → tedukuri

充実(じゅうじつ) → zyuuzitu

故障中(こしょうちゅう) → kosyootyuu

anyways yeah the kunrei system is nuts....as i said, transcription of any language into a new writing system is never easy, and i think it's really cool to see what the first official steps were towards romanization back in the 1930s!

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I've been working on a conlang that underwent tonogenesis by losing coda non elective stops and becoming high tone (coda elective stops then become plain voiceless, giving a fun way for my language to be divided into different initials and finals) and low tone coming from the coda fricatives [s] [ɕ] and [ʑ], with mid tone happening in open syllables or with coda sonorants (though 2 of those sonorants from the proto lang [r] and [r̥] are now fricatives [ʁ] and [χ]). I'm also debating having intervocalic /s/ debuccalize to [h] and then delete and get contours from those new diphthongs like this: [ˈʊ˩.sə˧.nʊ˩] > [ˈʊ˩.ə˧.nʊ˩] > [ˈʊə˧˥.nʊ˩] > [wə˧˥.nʊ˩] but I'm still not feeling satisfied with this but then I remembered reading yours and Jessie Peterson's posts on instagram about Ts'ítsàsh some months ago where you guys had tonogenesis by consonant loss and also stress and I was curious about how that worked in Ts'ítsàsh because I think that could be what I'm missing, especially because stress in the proto language was based on morae and was therefore not fixed and I want my conlang's tone to be more dynamic. Sorry for the long introduction and thank you for your time.

What is an elective stop...? I've never heard that term.

Essentially, stress is another variable you can play with. You can ignore, as your system here has, or you can add it back in to potentially create even more tonal distinctions in your language. Stress is associated with a number of elements, depending on the language: volume, vowel length, pitch level, or some combination of these. The goal is to somehow give a particular syllable more prominence than other syllables. If stress is associated with pitch, well, tone is also associated with pitch. You can imagine, then, you have two syllables, however this works (i.e. whatever needs to happen to get you these two proto-syllables):

*pat

*ˈpat

Now you've got options. You already know that a loss of something like [t] in coda position results in high tone on the previous syllable. Throw in stress, and you have some options. Here are some examples. First, there's option A, which is what you have above:

*pat > pa˥

*ˈpat > pa˥

That is, stress plays no role, and it's simply the loss of the consonant that gives the syllable tone. Let's call this option B:

*pat > pa˦

*ˈpat > pa˥

This kind of additive tone. The loss of the coda [t] pushes the pitch one point higher, while older stress pushes the pitch one point higher. This results in a high tone and a super high tone, which is now a regular distinction your language makes.

Now here's an option C:

*pat > pa˧˥

*ˈpat > pa˥

Some tone languages don't allow contour tones on short syllables, but if yours does, this is another option. With the loss of [t] and stress you get a solid high tone. The the loss of [t] and no stress, however, the tone is dragged down a bit, resulting in a rising tone.

This is how an older stress system can play into creating a more complex tone system down the line. You have to be meticulous in writing down the rules, and, both Jessie and I can tell you from experience, it's easy to forget them, but it can lead to some more grist, if that's what you're after.

Again, though, this is not something you have to do in creating a tone language. Often stress plays no role in the development of tone.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Navajo Phonology: Vowels

Requested by @okaylinguist | Part 1/2

This does not cover every possible way of expressing sounds, as regional varieties are very diverse, this is just a general guide based on my experiences with my family's language.

Simple Vowels

There are 4 core vowels in Navajo:

A = [ɑ] - Similar to father

E = [ɛ] - Similar to pet

I = [ɪ] - Similar to lip

O = [o] - Similar to boat

These vowels can be modified in three different ways: lengthening, shifting to a high tone, and/or nasalization.

Lengthening is indicated with double letters (aa, ee, ii, oo). The core sound listed in IPA above is maintained for all lengthened/double vowels except for ii, which turns to [i] instead of [ɪ].

A high tone is indicated with an upper accent mark (á, é, í, ó). When applied to a long vowel, it can either affect the whole lengthened sound (áá), or show a rising (aá) or falling (áa) tone.

Nasalization is indicated with a "hook" under the vowel (ą, ę, į, ǫ). Some nasal vowels are not written with the hook (for instance, after the letter 'n' typically). Nasal markings can be combined with the high tone mark (ą́, ę́, į́, ǫ́), and obviously also can apply to lengthened vowels. Though unlike the high tones, which can be over the first letter but not the second and vice versa, nasalization always affects the whole lengthened sequence

Constant tone + nasalization: ą́ą́, ę́ę́, į́į́, ǫ́ǫ́

Rising tone + nasalization: ąą́, ęę́, įį́, ǫǫ́

Falling tone + nasalization: ą́ą, ę́ę, į́į, ǫ́ǫ

Diphthongs

The 4 main diphthongs are:

ai = [aɪ] - Similar to bike

ei = [eɪ] - Similar to wait

ao = [aʊ] - Similar to how

oi = [ʊɪ̯] - Similar to bouy

Similar to the simple vowels, they can also be modified.

When lengthening them, typically the second letter is what is repeated (aii, eii, aoo) however for oi, I mostly only ever see ooi written. Another semi-irregular one is aai - some people I know pronounce it as long [aɪ], while others separate the long aa from the i sound more so. This is a case where the regional variety plays a greater role in my experience, as well as some words just preferring one to the other on a case by case basis, so I recommend just following what your teachers/resources tell you.

Miscellaneous Notes

Some people include subtle little "pauses" in their long vowels - not fully stopping and separating it into two vowels, but having a little dip in their tone, as if bridging a gap between the two vowels, especially if it is in the high tone register.

Did you enjoy this post? Do you want to help protect the Navajo language? Consider donating to my tribes' COVID-19 relief fund. The language cannot survive if Diné elders and youth alike are dying.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sin of Purity, Purity of Sin: Part XI

previous masterlist next

see end note for full content warning

Kiri lay shivering in her cell, huddled under her thin blanket. Autumn was turning into winter, and the nights in the stone room were growing cold. She was almost grateful for it, though—it kept her mind more alert. Some rich lord had been brought to the Chamber of Vessels two nights prior for a private ritual; for the first time in months, when she was at last brought out from the water, she’d not fallen into that hazy, dreamlike place within her own mind. Part of her wished she could simply float away into that state and stay there, where she couldn’t really feel her own terror.

But that was a foolish wish, she knew. She needed to stay sharp; based on the recent messages they’d received, it seemed that their rescue might be coming any day now.

Besides, whenever she’d disappeared into herself, Anden had always looked so relieved whenever she came back. She needed to try harder to not let it happen at all; if the cold helped her stay present in reality, then she should welcome the changing seasons. He was going through enough already, and he didn’t need to be worrying about her.

He did worry about her, though, despite her best efforts not to give him reason to. Over the past few months he’d grown quite attentive toward her, as well more open to her own consideration of him. She wasn’t sure what had caused such a change, but she welcomed it; it made this horrible nightmare a bit more bearable. Each night she had someone with whom to exchange light, distracting stories, or a few kind words. Even on the many days when they were both too exhausted to speak, to simply have someone else there with her, someone who saw her as herself and not an object to be used, had become a selfish source of comfort.

In his cell, Anden was draping his own blanket over himself and gasped at the movement. Kiri winced. He still refused to tell her what exactly Emitis did to him during his half of the private rituals. It wasn’t difficult to guess, though, that it was especially torturous. He groaned as he tried to pull the blanket further up over his shoulders.

“I wish I could do that for you,” she said softly. “I—I wish they would let me take care of you.”

“Not like there’s anything you could do,” he pointed out, not unkindly.

“I suppose not,” she admitted. “Still, though . . . I could sit with you. You could lay your head in my lap, if you’d like, and I could drape my blanket over the both of us. I could run my fingers through your hair until you fell asleep.”

Gods, what was she saying? Her cheeks warmed with embarrassment.

But tentatively, as though he were confessing something secret, Anden whispered, “I’d like that,” and her heart ached with a strange, happy sorrow. After a long moment, he asked, “Could you—could you sing for me?”

Kiri cast her mind about, trying to think of any song she knew that wasn’t a hymn to Vato. Her mother’s clear soprano voice rang out in her memory, and in her own warm alto she began to sing an old northern lullaby. The language had long been lost, but the song had been passed down in her mother’s family for centuries. Though she did not understand the meaning, the diphthongal vowels and lateral consonants of the words held a musical quality; they seemed to create their own melody, which that of the song merely harmonized to.

Her voice rose and fell at length, creating a sense of airy peaks and lush valleys. For a precious moment she was back in her village, singing softly to herself as she lay in her bed, gazing out her window at the surrounding mountains bathed in moonlight. The song's final notes wavered as she held back tears.

Looking over at Anden’s cell, she found him asleep, his expression more peaceful than she’d ever seen it. She wished from the depths of her core that, one day, he would know such peace every night.

Late in the afternoon the following day, a familiar figure came to pray at her pillar in the High Chamber; this time it was the tall woman with the dark braids. As she pressed her hand to Kiri’s before stepping over to Anden’s pillar, Kiri found to her relief that she’d only been handed a note. She’d mastered the art of dropping the tightly-folded slips of parchment into the fold at the side of her gown; it had been nerve-wracking two weeks ago when she’d had to do so with a tiny wooden box. She’d feared the object would prove too large for her makeshift pocket, but with the hints they’d been receiving that rescue was coming soon, she hadn’t dared refuse the item.

Thankfully she’d smuggled it back to the cells without incident, though she and Anden still weren’t certain of its intended use. Inside the box, they’d found a razor blade that they suspected was made of real Amantian steel, a metal rumored to be imbued with magic. Kiri didn’t believe such nonsense—everyone with the least bit of education in history knew that magic had died out from the lands at least a millennium ago. But the tiny blade was indeed remarkable; a bit of experimenting had shown that it cut through even cloth with relative ease. It had the potential to be an extremely useful tool, but to what purpose they couldn’t guess. She hoped that today’s note might prove illuminating.

She hoped, with a more wild and desperate sort of hope, that it might tell them they would be out of this hell of a temple that week, that very night even.

The next worshipper approached her. As he began reciting the prayer of gratitude, she subtly positioned her left fist to hold the folded parchment just above the fold in her draped gown. Just as she started to open her hand to release it, a passing priestess hissed in her ear to stand up straight, startling her.

She dropped the note.

Every fiber of her being was attuned to the subtle shift in the weight of her skirt as the parchment slid down the side of her gown. In a fraction of a second that seemed an eternity, it fell past her thigh, past her knee, until at last it finally dropped all the way to the floor.

She’d dropped the note.

Quickly she schooled her face into a carefully blank expression, but she could not still her shaking hands. Gods, what had she done? She tried to think of some way she could fix this, but panic was coursing through her entire body and she couldn’t think and gods, what had she done?

The notes were always so cryptic, though, she reminded herself; only Anden ever had any idea of their real meanings. Retrieval was surely impossible, but at least if it was found by anyone else, it wouldn’t give away any information. She gripped her skirts, willing herself to calm down. Perhaps if she could somehow slide the note further away from her without anyone seeing, no one would even suspect she’d had anything to do with it.

But where exactly had it landed? She shifted her weight to her right foot as she tried to subtly cast about the floor with her left. At last she felt it underfoot, and relief flooded through her so quickly that she felt her legs grow weak. But she couldn’t afford to fall apart right now. Far too much was at stake. Slowly, she began pulling the note toward the hidden safety of her skirts; she would wait until the temple staff were busy ushering the worshippers out at sunset, she decided, and then she would quietly kick it out toward the center of the chamber. With any luck, whoever found it would assume a worshipper had dropped it and think nothing of it.

But luck was not on her side, it seemed.

Just before she had pulled the note beneath her skirts, she felt a sudden resistance. Startled, she looked down to find an attendant crouched low, his hand pinning the folded parchment to the floor. She froze as he picked it off the ground and straightened back up. Without looking at her, he swiftly made his way to one of the priests at the side of the room.

It had all happened so quickly that the worshipper didn’t seem to have even noticed anything amiss; he continued in his recitation as though nothing had happened. But Kiri knew better. Her entire world had just changed in an instant. Months of multiple people risking their lives to plan an escape, had likely just gone to waste. And it was entirely her fault.

She must never be caught disobeying again.

Her hands began flapping.

She was strapped to the stone table and just below her collarbone her skin was on fire. But even through the anguish of the branding, she could hear Anden’s screams from the next table as the iron was pressed into his flesh.

She couldn’t get enough air, and the entire room was spinning.

She’d tried to run away and they’d marked her like cattle and the pain was excruciating. And he’d simply existed and been labeled the Vessel of Sin and they were doing the same to him.

She could sense Anden’s eyes on her, but she didn’t dare look at him. Had he seen what happened? Did he already know that she’d just doomed them both?

It was her punishment, so it was his punishment, and it was entirely her fault.

Emitis would know what she’d been doing these past months. He’d know that she was trying to run away again. His punishment would be swift and terrible.

Anden’s agonized howl filled the room and it filled her head and it filled her down to her core.

Even worse was the dreadful knowledge that they may never have another chance to escape. Anden may never have another chance—

She must never be caught disobeying again.

—and it was entirely her fault.

But no, she realized. Emitis didn’t know anything. Not yet.

She had to keep it that way.

The final half hour of the day stretched maddeningly, and yet it was over all too soon. As the last of the worshippers were guided out of the temple, Kiri’s anxiety continued to grow until she felt she might vomit. But she could do this. She had to do this. Because what other choice did she have?

Edric came and unlocked the collar that kept her leashed to her pillar. “Heard you’ve been a bad girl,” he said lowly as his fingers brushed the nape of her neck. “I just hope that I can help give you what you deserve.”

She jerked her head to the side as she threw up on the floor. Some of it landed on the left of her gown, and she watched as one glob ran down into the folds of the skirt. Suddenly, she was laughing, and then just as suddenly she was crying.

Pain erupted across the side of her face, and she realized belatedly that Edric had struck her and was now dragging her out the door of the High Chamber, with Anden and his guards hastening to follow. But instead of heading to the back halls, he pulled her along toward the temple’s main entrance before turning into the east wing and stepping into the Chamber of Contrition.

Inside, standing just before the statue of Vato on His throne, stood Emitis.

In his hand was the note.

Kiri was forced to her knees, and soon Anden was down beside her. Neither one of them looked at the other.

Slowly, Emitis unfolded the slip of parchment, and his voice was dangerously calm as he read, “’I’ll meet you at your house tomorrow night, or if I find I can’t get away then I’ll meet with you next year—I still need to return your copy of The Seaman of Oshna.’” He held it up to her for her to read. “What meaning does this hold to you?”

“I—I don’t know what it means.”

“Liar.” He motioned to one of Anden’s guards, who struck Anden so sharp a blow that he fell to the floor.

“Please—please, I don’t know, truly!”

“Rather difficult to believe that’s possible, given the pains you were taking to hide it.” At his gesture, the guard kicked hard at Anden’s stomach, eliciting a low moan. “Tell me.” With Anden’s arms still bound behind him, he could do nothing to protect himself when the next kick hit his chest.

“Stop—stop it, please! I swear, I don’t know!”

Another guard yanked Anden up by the hair while the first punched him hard across the jaw.

Emitis gripped her chin and forced her to look up at him. “Who gave this to you?”

“N—No one.”

“Don’t lie.”

Another blow, and Kiri’s hands flapped in distress. As the interrogation continued, Anden’s groans grew louder and louder, until at last a shout was torn from him that sounded more animal than human.

Emitis’ tugged at her face until she was looking at the ground where Anden lay panting. There was a hard determination in his green eyes, but already one side of his face was swelling, and he was almost doubled over in pain. And she could see from the clench of his jaw that, however stoic he might try to appear, he was just as scared as she was.

“I know how much it grieves you to see him hurt,” Emitis said tenderly. “If you’ll only tell me the truth, you won’t have to hurt him anymore.”

The injustice of the statement broke something loose inside of her; through her tears she snarled, “I am not the one hurting him!”

The High Priest was silent for a moment. “You think not?” His voice took on a dangerous edge that made Kiri’s breath hitch. “Perhaps we must help you understand, then.” He pulled her to her feet, and moments later she was standing face-to-face with Anden.

Whatever was coming next was going to be hell, she knew with terrible certainty. And as she guiltily met Anden’s gaze she could see that, somewhere behind his mask of angry defiance, he knew it too. “I’m so sorry, I’m so sorry,” she whispered in horrified refrain as tears streamed down her face. Had it truly only been last night that she was taking comfort in the thought of escape, and of Anden finding peace somewhere away from all this torment? Such dreams were all but impossible now.

And it was entirely her fault.

Something was pressed into her hand, and she looked down to see that she was holding a small knife. She stared at the blade in bewilderment, finally looking up to see that Anden was being given one, too. The guard who handed it to him warned him not to try anything, and she noticed at last the half dozen guards in the room had surrounded them with weapons drawn. Her stomach began to sink even as her mind was still slowly trying to catch up to what was happening.

“Now then, allow me to explain how we will proceed,” said Emitis, and his eyes gleamed coldly as he fixed his gaze upon her. “I will ask a question, and you will answer. If I do not like your answer, you will make one horizontal cut across the arm of the Vessel of Sin, and he will do the same to you. Should either of you refuse to do so, the guards will be the ones doing the cutting, and they may not be so kind as to stop at only one. Are we clear?”

Kiri looked down at the knife in her hand. And then she looked up at Anden, but she saw him as though from far away. She’d floated away into that hazy place within her own mind, the place where she couldn’t really feel her own terror. Numbly, she wondered if she would ever leave again. Perhaps Anden would no longer care if she didn’t, not after today.

Her heart shattered at the thought, and she didn’t feel a thing.

next

If I get yelled at for this one, I am very aware that I'll deserve it. I promise everything will stop being so terrible...eventually!

Thank you so much for reading!!!

taglist: @starlit-hopes-and-dreams @little-peril-stories

content warning: captivity, religious abuse, restraints, torture, dissociation, victim self-blaming

#whump#whumpblr#whump fic#whump writing#captivity whump#fantasy whump#religious whump#multiple whumpees

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, you're from Georgia, right? And you've seen Glass Onion?

I am also from The South, tho not Georgia, and I thought while watching it that Helen's southern accent was *off* by about the same amount that Blanc's was *off*, just in a different direction. So I thought that the Knives Out universe might be a parallel universe where people from the south just Talk Different.

As someone from Georgia can you confirm? Or was Helen's accent actually really accurate and I'm just used to other southern accents?

No yeah!!! I feel like Helen's accent was about as accurate as Blanc's, which is to say these are not real people voices. These are accents that were pickled, vacuumed sealed, and then released months after fermentation.

Now Daniel Craig is playing in make-believe space. We must be in agreement that Blanc exists in a realm where southern belles were less social convention and more actuality. That's just the character he is inhabiting, I love it and see no issue.

HELEN HOWEVER. Her accent had too much of a pointed twang for me. It lacked the hallmarks of AAVE. She diphthongized the vowels but didn't drop the "t's and d's in her speech ("whuyT" instead of "whuh.") And she emphasized the front of the words instead of the back ("INsane" instead of "inSAANE") ("HA-yer" instead of "hayEH.") If she had softened the end consonants and drawn out the vowels, I think it would've been less jarring. Especially when she switched to her normal speaking voice.

And like, plenty of Black southerners also speak with a twang, but genuine AAVE impacts speech regardless of region. So I would expect Helen to sound similar to Birmingham speakers, as it's a major Black hub in Alabama. I linked a comedian for comparison.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

the rosary in michif

So the way I rewrote this is how to pronounce it with symbols that make sense to me. I also changed the english versions so you know how these things are pronounced.

ɑ = anywhere between father & mop

a = the a in the french la, or anywhere between the a in above & father, (not in between like the way the o in above is in between u from rut & o from mop), except the a in above is more like the u in bun or the e in the, but in the english I started using u to symbolize the u in crutch/a in above/o in above (even tho it is more like the o in mop or the o in more without the w at the end)/e in the

é = the e in met or pen

æ = late, bait, may eidelweiss

i = if, bit, some ppl even use this i in both halves of spirit (if they don't say spyyrit), & sometimes that sound that is like "eu" crossed with "uh" crossed with "o'" crossed with "a" crossed with "e" & you just can't exactly tell what it is

í = eat, feeble, meme

o = anywhere between boat & the first two "ho"s of ho ho ho, it can be the o,w of words like hope, or it can be just the o' like if someone interrupted you before you finished saying "go". It's almost like how er starts with eu & ends with r, this starts with o' & ends with w,

oo = on in french, between boat & boot, it's like the "o" from above was a little more short/fat in your mouth so it is slightly more like a "w" but not quite, & then you do end it with that diphthong w. Like if you end the french garcon with a w as well as an n.

ʊ = oo, like shoe which can be eu'w, or it can be just the w (which is a vowel, the welsh are right), who, the first part of when, or when you say a really elongated "ooh" not just an euw but an euwwwww!, the end of "oh!"

eu = book, look, cook, hurt, the french feu, birch, earl, like take your tongue down from the back there & stop saying the r, it's like how we say "uh" in north america but they spell it "er" in england, they don't mean ir/eur, they mean euh. Like heard in a british accent

ä = a like cat. It was originally written as ae, but ae to me means éy (or ah-y), while in michif according to my legend it is supposed to mean a like ban. I actually do get it being spelled ae, but I used to spell it aa & have taco be spelled ah & lot be spelled aw (cahmmin vs cawmmun being two ways to say common). Anyway this is the a like fabulous or the way your white (not european) grandmother says pasta.

š = technically sh, but I actually often pronounce this as an s. Many cree speakers, especially as they get older, say things with a bit of a lisp, making the s turn into sh, & we have taken that into michif. In fact, the word michif comes from the lisping of the t in metis into ts, & the all-too-common lisping of ts into ch. You can say as s or as sh & it is fine

č = ch, in michif we usually say it more like ch, the "tsh" sound, but in cree it is more like ts, sort of like the japanese tsu. You know how ts is at the very front of your mouth but ch is a little farther back & a little more on the edges? Go halfway in between. Keep a little more contact with either side of the front of your tongue, & say it. Mix ts & ch to get smth halfway between. It's almost like chs in the way it sounds, but more like tch in the way it feels. Evn throw in a bit of soft "th" in there if you need.

I don't think I have ñ, but it is like a "ng" that doesn't quite make contact. It's the french n

r = Two options here. Option 1: earl but hover before you close your teeth on the r. Feel how far back that is in your mouth? Push it a little farther back, push that r a little further in general. Instead of that r being stupidly in your teeth (that's the reason kids way w instead), keep it closer to your throat, more in your soft palate, not where the bone starts. Option 2: khrkhrkhrkhrkhr almost like that arabic crackly h, & it can be voiced or unvoiced. It's a trilled g. Not a trilled d like in spanish though. Make the sound like the dentist's vacuum. It's a fricative.

ž = j, like how ch is just tsh, j is just dj, like how s becomes sh, z becomes zh. It is j without the starting d.

Some of the Gs can also be Ks occasionally, along with many other consonants. t/d, p/b, etc.

In fact, k/p/t are often pronounced softer, less aspirated.

hk can be either h,k or it can be the semitic/celtic ch like in bach or loch. hp can be like the filipino f that they make bilabial instead of labiodental.

I think that's everything. It is a lot more simple than writing it out seems.

Oh & in english I used eth & thorn, eth being bath/thank & thorn being bathe/that

Li Shaplæ - The Holy Rosary

Wíčæwagɑnɑ Tapætamwag –

Apostle's Creed

Ndɑpwæténn li Bonjeu,

li Papa kašokatišidmawači,

kɑkiw kaožitɑt li syél ékwa la tér.

Ndɑpwæténn li Jéyzʊs

kɑgíkičítotɑt péyʊg égo son

Garsoo, kɑnígɑníštamagoyak,

kíošíéw očé

okičitawišokišíwinn avik

ékičitwɑwak Kinígígwann,

ékwa énítawigit očé la Sänt Vyɑrž.

Pontyas Paylat nɑšpič kígwatagíéw

li Bonjeuwa, kíšagawéywag

denn krwa, kínipo, ékwa kínačigɑšo.

Kíšidša'hwawandagɑnipočig,

dɑn la trwazyém žʊrnæ kípašéygo mína.

Dɑn li syél kítotéw,

ékwa kíapígɑšo andɑ

tapiškoč Papa. Mína tapætotéw

čipæwíéšowɑdat kapimɑtišíid

ékwa kɑnipoyit.

Ndɑpwæténn ékičitwɑwak

Kinígígwann, kɑkičitwɑwak liglíz,

kakío kapimičawɑčig li Bonjeu

awɑ dɑn li syél ékwa dɑn la tér kakío

li Bonjeu sa famí, čiponéy čigɑtég

kamačítočigɑtég, li kor číapačipɑt

ékwa čipimɑtišik tapitaw. Answičil.

Aí bilív in God, þa Fɑþer ɑlmaítí,

kríæter av hévén änd eurð.

änd Aí bilív in Jízas kraíst, hiz only San,

äwr Lord, hʊ waz kɑnsívd baí

þa päweur av þa Holí Spírit, änd

born av þa Veurjin Méry.

Hí suffeurd undeur Pɑnčas Paílit

waz krʊsifaíd, daíd, änd waz beuríd.

Hí déséndid tʊ þa déd, änd ɑn

þa ðird dæ hí roz agén. Hí

aséndid intʊ hévin, änd iz sítid

ät þa raít händ uv þa Fɑþeur. Hí

will kum ugén in glorí tʊ juj

þa living änd þa déd.

Aí bilív in þa Holí Spirit, þa holy

käðlik čeurč, þa kommyʊnyeun av

sænts, þa forgivniss av sins, þa

réseurrékšan av þa bɑdy, änd laíf

éveurlästing. ɑmén.

Ton Pérínɑnn - Our Father

Ton Pérínɑnn, dɑn li syél kayɑyénn

kíčitwɑwann ton noo.

Kiya kɑníkɑništamann péytotéíé

kɑndawætamann tɑtočíkatéw

ota dɑn la tér tɑpiškoč dɑn li syél.

Mínɑnn anoč mon pänínɑnn

ponæíminɑnn kamačitotamɑk,

níštanɑnn nkaponæmɑnɑnik

aniké kɑkímaítotɑkoyɑkʊk

kayakočíinɑnn, mɑka

pašpíinɑnn ɑyik očé

mɑčíšíwæpišiwinn.

Kɑníkɑníštamawíɑk,

kišokišíwinn, kɑkičitæmíak

kiya aníé, anoč ékwa takíné. Answičil.

Awr Fɑþeur in Hévin, yor næm

iz holí. Mæ yor kingdeum keum,

änd yor will bí dun ɑn eurð äz

it iz in hévin.

Giv us teudæ þu fʊd þät wí níd

änd forgiv us for aʊr sinz,

just az wí forgiv þoz hʊ sin

ugænst us.

Giv us stréngð to résist témptæšun,

änd kíp us frum ɑll ívil. ɑmén.

Kičítéím Li Bonjeu - Glory Bé

Kičítéím kí Papaínɑnn,

ékwa li Garsoo,

ékwa Ékičitwɑwak Kinígígwann.

Tɑpiškoč kɑmɑčipaíik,

ékwa šæmɑk, ékwa tɑpitaw ~

la tér ékɑ čiponipɑyik. Answičil.

Glorí bí tʊ þa Fathér, änd tʊ

þu Son, änd tʊ þa Holí Spírit, äz

it wuz in þu béginning, iz naw,

änd forévir šäll bí ~ weurld

wiðawt énd. Amén.

O Mon Jéyzʊ - Oh My Jízus

O Mon Jéyzʊs, ponæminɑnn

kɑmačitotamɑk, pašpíinɑnn

dɑn li feu očé dɑn lenfér.

Nígɑníšta kɑkío ninígíawɑnɑnig ékwa anigé nawač kandawéítakig

číkitimɑgæ mɑčig. Answičil.

O mɑy Jízus, forgiv us awr sinz

änd sæv us from þu fɑyrz uv héll.

Líd ɑll soolz tʊ hévin, éspéšullí

þos most in níd uv yor meurcy. Amén.

Kigičítéímitínɑnn Marí - Hail Mary

Kigičítéímitínɑnn Marí,

ékičítéímit, Li Bonjeu wiya

avik twa. ékičítakišoyénn

kiya ki tʊ lí fém, ékwa

kíčitwɑwɑnɑ mawišwɑnɑ

kapimotɑtayénn katɑk Jéyzʊ.

Kíčitwɑwann Marí, Mér di

Bonjeu, ayamíéštémoinɑnn

šæmɑk ékwa atinapoyɑko. Answičil.

Hæl Mærí, full ɑv græs, þu

Lord iz wið yʊ. Bléssid ɑr

yʊ amung wimin, änd

bléssid iz þu frʊt uv yor wʊm

Jízas. Holí Mérí, Muþeur uv Gɑd,

præ for us sinneurs, naw, änd ät

þí aʊr uv awr déð. ɑmén.

Míawɑtann Mɑmaškɑč

i. Li tɑnž Gabríél kípæwítamawéw la Sänt Vyɑrž än pičí Jéyzʊ æwéyɑwat.

ii. La Sänt Vyɑrž kígíogawéw sa koʊzinn ílizabéth.

iii. Li pičí Jéyzʊ natɑwagéw.

iv. Li pičí Jéyzʊ kítotaígɑšo kɑkičitowak la Méyzon.

v. Kímiškɑgɑšo li pičí Jéyzʊ kɑkičotawak la Méyzon égoté žérʊsalém.

Mɑmatawinɑgwanɑ Kɑwašaškotéígé

- þe Luminous Mysteries

i. Jéyzʊs kíšigayatagašo dɑn la rivyér dé žordan.

ii. än nas aštéw én Kana.

iii. Jéyzʊs itwéw kakičitowišid pé ayaw.

iv. Jéyzʊs wapataíwéw ogičitoišíwinn éywɑškošod kíošta'ayik wiya dɑn li montaynn dé Téybor.

v. éškwač Jéyzʊs sʊpí kɑmíčišočig avik wíčéwagana kígímíægonɑnnwiyawɑnn ékwa son sɑn, číwíčéwayak tapitaw. (the institution of the eucharist at the Last Supper. Jesus gives us his body änd blood so that we can choose to receive eternal life.)

Mitɑtætɑgwann Mɑmaškɑč

i. Jéyzʊs kwatagætaw dɑn li žardan.

(I've heard it as "jargin" not just "jardan")

ii. Jéyzʊs kínočígɑšo än fwét kíabačitɑwag ékwa lí ploon égígamogé.(the scourging at the pillar has a much longer name here: he is tied to a pillar & beaten with a whip made with lead)

iii. Jéyzʊs kíačigɑtéw än koronn oči šnélí.

iv. Jéyzʊs kípimíwatægɑšo la krwé. (I'd actually say krwa like krwoa bc it is croix in french, but michif is like cowboy french)

v. Jéyzʊs kíšagɑwéywag dɑn la krwé očičig ékwa očitak.

Mɑtawpayinn dɑn li Syél - Glorious Mysteries

i. Apičípaw Jéyzʊs niponik očé.

ii. Jéyzʊs dɑn li syél itotéw.

iii. ékičitwawišid péítotéw.

iv. La Sänt Vyɑrž šipwétaígašo dɑn li syél.

v. La Sänt Vyɑrž ošigašo la Rénn dɑn li syél.

Kígičítéímitínɑnn Kɑgičitwɑošyénn La Rénn - Hail Holy Queen

Kígičítéímitínɑnn

Kɑgičitwɑošíénn La Rénn,

Mama očé gɑšɑgí'íwét.

Kičítéítɑ mbimɑtišiwinínɑnn,

kɑšíwišíɑk, ékwa

kɑpagošéítamɑk.

Nimɑtonɑnn mon Sänt Vyɑrž

anɑnn očé kɑwæpinigɑšoyak

líz enfen očé ív.

Ota dɑn la valí mɑtowinn, ékwa

kɑgɑškéítamik,

kígagwæčímikawinn

číwíčí'íɑk.

Ayamíéš tamɑwínɑnn

wíjí'ínɑnn čimiškawayɑk

ton garsoo Jéyzʊs. Answičil.

missing in the translation so idk if it is correct: thine eyes of mercy toward us & after this our exile show unto us the blessed fruit of thy woumb, o clement o loving o sweet virgin mary pray for us oh holy mother of got that we may be made worthy of the promises of christ let us pray grant we bessech you that by meditating on the holy mysteries of the most holy rosary of the blessed virgin mary we may both imitate what they contain and obtain what they promise through the same christ our lord amen. It's missing it after it says "pray for us most gracious advocate & help us to know your son jesus" which is skipping the "turn" your eyes & the exile part. It is also missing toe rosary closing which is not technically part of the prayer but I associate it with the salve regina bc that's when I usually say it.

Ayamíɑwinn očé ékičitwɑwak Kinígígwɑnn - Prayer to þa Holy Spirit

Kɑníganíštamɑwíak dɑn li

syél, ana kaočicanawapamigoyɑk,

onígí'igwɑnɑ kɑtɑpwæit

mišíwæayaw ékwa kakío

kégwéy kaítagwak, anda

kaočikičitotagawíak, ékwa

pimɑtišíwinn kɑmí'igoyak;

Pépítigwæ dɑn mon čoér,

kišípégininɑnn

čígɑšíɑpawitayénn ægok

kɑpémačitotamak,

pimɑčitɑ ní'ígígwaínɑnn

kɑkičitowišíénn. Answičil.

Jéyzʊs Mon Bonjeuínɑnn - Jesus prayer (better translates to jesus my God(our's)

Jéyzʊs Mon Bonjeuínɑnn,

li Garsoo kapimɑtišid očé

ton Bonjeuínɑnn,

kitimɑgæminɑnn

kɑmačigækwyʊiɑk,

kiyanɑnn očé kapašpí'íwét. Answičil.

#metis#Métis#michif#michif language#otipemisiwak#rosary#metis folk catholic#metis folk christian#fnmi#folk christianity#folk christian#metis christian#metis catholic#michif rosary#metis rosary#christianity#christian witch#christo#christopagan#christowitch#chaplet#li shaplee#le chaplet#michif prayer#metis religion#linguistics

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do the languages in Yhine sound like, compared to Earth’s languages?

Girun (Giruvin), Omaude (Omauden), and Tetlunen (Tetlen) are all very linguistically related; they don't have a lot of diphthongs, their words tend to be very similar and have a lot of harsher sounds and unvoiced consonants, and they have about the same amount of cross-language understanding as the Romantic languages on Earth do. Omaude has a few more diphthongs and tends to have softer sounds than the other two, but it's not a massive difference.

The spoken language in Wirshirdauwn (Lenshespel) has a ton of different dialects, and some go a little "harsher" in the mouth than others. However, they still all tend to have a lot softer sounds than Girun, Omaude, and Tetlunen do, and they're extremely fond of their diphthongs and their contractions. Underwater, they use a sign language (Seshespel) that has a lot of emphasis on big gestures, and they'll make use of clicking noises and such to add emphasis if they're close enough to each other. Their sign language also has a lot of full body gestures, as underwater, they don't have to worry so much about where their feet are so long as they're able to keep themself from drifting off in the ocean.

Ak'an's language (Ak'ert, literally "Ak's language") is similar to the language in Wirshirdauwn, just with fewer dialects and a lot more harsher and unvoiced consonants (which can be seen even in just their names--"Ak'an" versus "Wirshirdauwn"). There's also multiple formal dialects and multiple informal dialects, and a solid chunk of their comedy is knowing how to use both informal and formal dialects to make each of them sound equally ridiculous. Knowing where to use certain words for certain emphasis, knowing when to use "swears" versus "bad words", knowing when to swap every other word for a different dialect (especially to emphasize confusion or big, "contradicting" emotions), etc etc. Being able to do that efficiently and on the spot as in improv comedy is seen in the same light as being an exceptional voice actor (although, societally, they're both significantly more respected for what they do than they are in our world but whatever.)

The Forebarrier mostly speaks English with a smattering of heavily German- and Spanish-influenced dialects. That it is because it's largely populated by the Constellate, and the Constellate is English-speaking and knows almost an ounce of German and lives in a town with a very high Hispanic population (although it only knows a little bit of Spanish itself off the top of its head, it can usually understand the basic gist and a few details of most things it reads in Spanish).

The Plains don't really have a specific "language"; different villages have all developed their own languages, some more similar than others. Same with The Great Divide. (Note: both of these aren't countries, they are more regions of the world. However, due to their surrounding countries and the natural "borders" in the land, they both earn a place as distinct entities and thus deserve a mention.)

Aaaand... that's about all we know? We don't really talk to folks in the other nations very much, aside from Carmen during continental congregations, although there they all speak Omauden (similar to Giruvin and Tetlen, generally easier to pronounce for native speakers of Ak'ert and Lenshespel) so zhe never really here what the languages of other nations sound like.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Latin: The Basics for Beginners

Introduction

Latin, the ancient language of the Romans, continues to enchant and educate people worldwide. Its influence on languages, literature, and legal systems is undeniable. For beginners eager to embark on the fascinating journey of learning Latin, understanding its grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation is the first step. This post will guide you through these fundamental aspects, providing a solid foundation for your Latin learning adventure.

Understanding Latin Grammar

Latin grammar may seem daunting at first, but it's quite systematic. One of the language's distinctive features is its use of inflections. Words change their form (inflect) based on their role in a sentence. This is crucial for understanding Latin since word order is more flexible than in English.

Nouns and Cases

Latin nouns are categorized into groups called declensions. Each noun has a gender (masculine, feminine, or neuter) and is declined according to case and number. There are five main cases in Latin - Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, and Ablative - each serving a different syntactical purpose. For instance, the Nominative case is typically used for the subject of the sentence, while the Accusative is often the direct object.

Verbs and Conjugations

Latin verbs are conjugated to express tense, mood, voice, number, and person. There are four primary conjugations in Latin, and verbs are grouped into these based on the ending of their second principal part (the infinitive). Learning to conjugate verbs is essential for forming sentences and expressing various actions and states of being.

Adjectives and Agreement

Adjectives in Latin must agree with the nouns they describe in gender, number, and case. This agreement is vital for sentence clarity and coherence.

Building Latin Vocabulary

Expanding your Latin vocabulary is a mix of memorization and recognition of patterns. Many Latin words are the ancestors of English terms, especially those in scientific, legal, and literary contexts. Start with common nouns, verbs, and adjectives, and use flashcards or apps to reinforce your learning. Practice by translating simple sentences from English to Latin and vice versa.

Mastering Latin Pronunciation

Classical Latin pronunciation is somewhat different from the Ecclesiastical (Church) Latin used in religious contexts. Here's a brief guide to classical pronunciation:

Vowels are pronounced more distinctly than in English, with 'a' as in "father," 'e' as in "they," 'i' as in "machine," 'o' as in "fort," and 'u' as in "flute."

Consonants are generally pronounced as in English, but 'v' is pronounced as 'w,' and 'c' and 'g' are always hard, as in "cat" and "get."

Diphthongs like 'ae' and 'oe' are pronounced as 'ai' in "aisle" and 'oi' in "oil," respectively.

Conclusion

Embarking on the journey of learning Latin is not just about mastering a language; it's about connecting with centuries of history, literature, and culture. By grasively embracing Latin's grammar, diligently building your vocabulary, and accurately mastering pronunciation, you're setting a strong foundation for your Latin studies. With patience and practice, you'll unlock the rich and rewarding world of Latin texts and traditions. So, take a deep breath, dive in, and let the language of the ancients guide you through a transformative learning experience.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

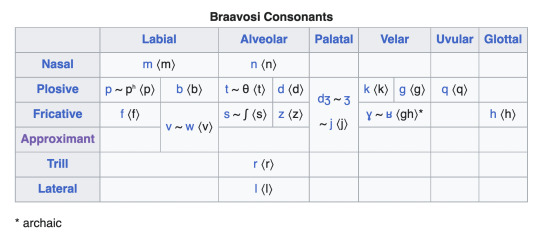

The Titan’s Tongue: The Language and Script of Braavos

Been thinking a lot about Braavos and the writing system of its tongue. Arya and Sam’s chapters exploring the city are so full of flavor and life that I wanted to gain a glimpse into its writing as well, and see what it would be like. We unfortunately have very little information about the Braavosi language, with it being completely absent from the show and only mentioned in passing in the books that the Waif is teaching it to Arya as part of her training in the House of Black and White. What little we know is largely names, but from this we can ascertain a bit about the language, and what we need for the script itself. The language seems to be to High Valyrian what Italian was to Latin: reduced vowel system (no distinction between short and long vowels, similar to Astapori Vayrian), eschewal of consonant clusters in favor of gemination (like in Tagganaro and Bellegere), and preference to end words in vowels.

Over the course of this post I will be trying to determine the sounds we would find in Braavosi and create an alphabet for the city’s people

Phonology

I imagine that the Braavosi have had a script loosely descendant from the High Valyrian writing systems, developed about 400 years ago when the first escaped slaves landed in the shrouded lagoon that is now the city’s harbor. These slaves and Moonsingers would have likely spoken a Low Valyrian tongue absent of some of the sounds that are represented in High Valyrian. By loose descent, I mean essentially that the letters are not necessarily one-to-one drawn from specific Valyrian glyphs (like Phoenician and Egyptian) but instead used as general inspiration. I also imagine that the Braavosi script is rather rounded and elegant, primarily written by quill and inkbrush, unlike Valyrian. Using @dedalvs ‘s wonderfully crafted High Valyrian and its phonology, as well as the phonologies of its descendant tongues in Astapor and Meereen, we can construct the following statements about Proto-Braavosi Low Valyrian:

no [r̥] (merged with r)

no [ʎ] (pronounced instead as [lij] or simply as [l] based on word context)

no [ɲ] (pronounced instead as [nij] or simply as [l] based on word context)

no long vowels (merged with short vowels)

the “gh” sound ([ɣ ~ ʁ]) is present in Proto-Braavosi, but does not seem to persist into modern Braavosi as we will see

Based on the attested spellings of the Braavosi names (factoring the fact that it is filtered through a Westerosi’s ears), we can extract the following information.

Consonants: l qu f g n t r y/j s d b sh th c/k/ch q m z ph h

Vowels: a e i o u y

Diphthongs: aa (Braavos), ae (Baelish), ay (Prestayn), ey (Jeyne, Wendeyne)

Since ph and f seem to be transcribed as distinct (such as in the name Phario Forel) they seem to be phonologically distinct sounds and not simply allophones. Thus, ph can either be an aspirated stop [pʰ] or a bilabial fricative [ɸ]. Since no unvoiced ‘p’ is represented, let us say that this is an allophonic variant of \p\ in Braavosi speech, transcribed by foreigners as “ph.” The “ch” in Tycho Nestoris could be an affricate [t͡ʃ] or a [k]; the latter seemed more natural to me. The “qu” in Allaquo seemed it could simply be represented as [k] + [w] or [q] + [w], or otherwise a labialized [kʷ] or [qʷ]; I think it can be ignored when creating our letters, particularly as it is not attested in High Valyrian. The sound sh ([ʃ]) exists only in the name Baelish, which very well may be Westeros-ized by its speakers, seeing especially as the sound does not exist in High Valyrian; we will thus treat it as an allophone of [s]. Finally, “th” is used to spell many Braavosi names (Uthero, Otherys, Lotho); this may be interpreted as a fricative [θ] or simply as another spelling of [t]; for the sake of simplicity, we will represent this allophone (if it is even an allophone at all) as another variant of “t.” Thus our final consonant inventory is as follows:

Consonants: p/ph b t/th d k/c/ch g q gh* s/sh f v/w z m n l y/j r h

*gh = Proto-Braavosi only

Or, represented in an IPA chart:

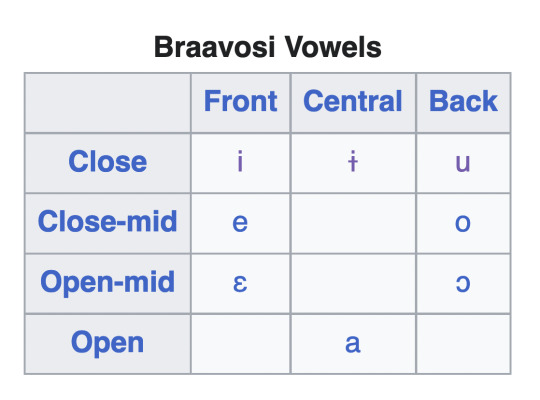

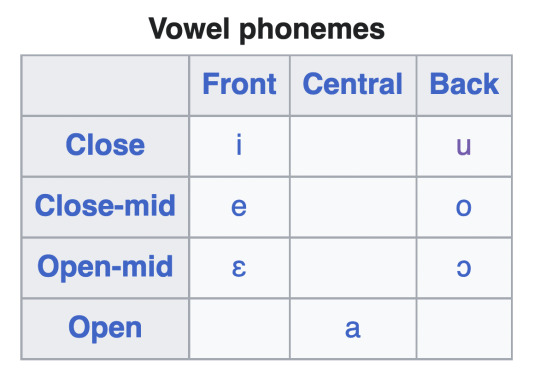

Apart from the loss of distinction in vowel length, there are two changes of note. One is that the rounded close front vowel [y] in Valyrian has shifted to an unrounded close central vowel [ɨ] in Braavosi. Furthermore, although not represented in writing, the vowels ɛ and ɔ are found in Braavosi speech (basically leaning hard on the medieval Florence/Italian parallels).

We are left with the following vowels.

(For context, here is modern Italian phonology lol.)

As for diphthongs, I won’t elaborate too much except to say that they are simply written using a combination of vowels (and the semivowel j/y), though their spelling patterns don’t always match onto their pronunciations. This post dwells little on orthography, but I think with more than 400 years of history the Braavosi script will have had time to develop concrete spelling patterns and crystallized standards which no longer reflect modern speech (though due to the somewhat egalitarian economy and political systems of Braavos, at least compared to Westeros and the other Free Cities, I think the script will not have diverged too radically from “common sense”). For instance due to sound changes representing an older form of Braavosi, a name like “Baelish” would likely be spelled something like “Bayelis,” with the spelled cluster “aye” represent the name.

I think there are two sound changes at play: one from High to Low Valyrian led to the loss of diphthongs (ae => e, so Daenerys => Denerys), and the second one from Low Valyrian to Braavosi which led to the elision of “y” between vowels(aye => ae, so Bayelis => Baelis/Baelish).

Script

With the phonology and basic history of Braavosi speech outlined, we can present the final writing system of the language, which I show in my next post:

https://www.tumblr.com/greenbloods/722222867516915712/the-idea-of-a-braavosi-alphabet-has-been-churning?source=share

Though it is bog-standard for fantasy scripts, I decided to make the writing system a bicameral alphabet, as it would best showcase the aesthetics of the script. I also wanted there to be a feel as if there were some far-back connection between Braavosi and the alphabet of the Common Tongue of Westeros (they would simply be using the Latin alphabet), which is also why I decided to make the “o” letter a blatant imitation of our letter O. The letter f is derived from the letter p as a visual reminder of the “newness” of the letter

Keep in mind that the script is only a snapshot of written conventions in one medium during one period of time, and there may be many variants for the script as well.

#yeah ik ik bicameral scripts get some flak but i think it works#braavos#valyrian#high valyrian#asoiaf#game of thrones#neography#david j peterson#linguistics#my posts

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that’s kind of funny to me is just how long writers in English struggled to come up with a way to represent long vowels. They didn’t bother in Old English--you had to know whether a vowel was long or not, like in Latin, and if you didn’t, or if you’re studying Old English a thousand years later and trying to work out which vowels are long and which vowels are short, well, you can just go fuck yourself, buddy. A lot of scribes over the centuries quite sensibly tried for more phonemic transcriptions of English, with varying success.

The Orrmulum is a good early example of this kind of work. Its author, Orm, came up with a number of innovative spelling practices to represent English unambiguously. Alas, precisely none of these stuck; probably because his text’s most notable feature, using a double consonant to represent a preceding short vowel (since two consonants in the syllable coda reliably indicates a short vowel in most Germanic languages) is simply awful to look at. But god bless the man for trying.

In Middle English, the development of the maximal onset principle, which reallocated which syllable in a word a consonant belonged to in a way which tried to load as many consonants as possible onto the beginning of a syllable, led to the creation of more open syllables; subsequently, the vowels in open syllables were lengthened. This made it much easier to predict where a vowel was long vs where it was short--still not possible with 100% accuracy, since there were lots of closed syllables that retained long vowels (like in child, climb, and old), but this meant that a lot of words ending in vowels, especially -e, definitely had long vowels in them.

This is where we get the “final -e denotes a long vowel in the preceding syllable” spelling convention in English from; it was a sufficiently useful tool that even words which never had a final -e came to be spelled with one, to indicate a preceding long vowel, and even once this final -e fell silent (as it was starting to in the Middle English period), it was still written to indicate a preceding vowel. And we have retained it to this day--despite the fact that it arguably became mostly superfluous with the Great Vowel Shift, which diphthongized a bunch of long vowels! We could spell the vowel of “site” with no ambiguity as “sait” (indeed, that is approximately how you would transcribe it in the IPA), or the vowel of “fight” (which indicates the long vowel differently, using the silencing of the sound represented by <gh> with the attendant compensatory lengthening of the previous vowel) as “fait,” but instead we use a hodgepodge of centuries-old phonetic spelling techniques and kludgy workarounds, because English orthography has never been good at being simple.

A modern, cross-dialectical orthography of English (so, one that wanted to suffice for most North American, and British, and other regional varieties without too much ambiguity) would have almost no trouble with long vowels--with the exception of non-rhotic varieties there is no actual phonemic contrast purely in vowel length, and if you were creating a novel English orthography from scratch, I don’t think non-rhotic speakers would complain about keeping the rhotic spellings in, since they’re used to them. But English spelling reform is a thousand years too late--even by Orm’s day, the literary culture was already too much of a muddle of dialects and divergent spelling conventions to fix, and it has only become worse since.

No, better to learn from English’s mistakes--like the Icelandic scribes did, by putting a little tick mark over the long vowels way back in the 1300s, a system that has worked perfectly well for the language even through all the subsequent sound changes in the seven centuries since.

#it's not like the old english scribes were averse to diacritics#they used them all the time for scribal abbreviations!#they just never thought to use them for long vowels

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

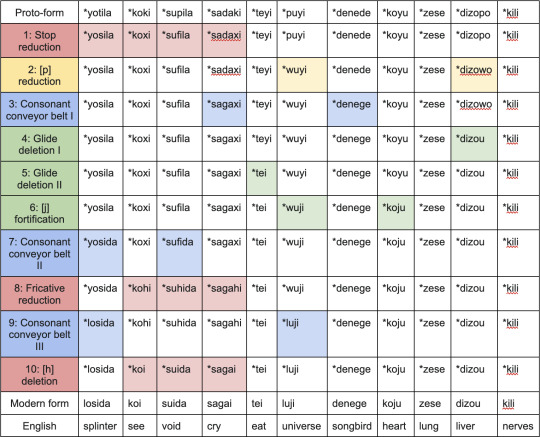

Conlang Year Days 31–33

At long last and after an uphill battle, I have a finalized list of ten sound changes (several of which are actually groups of similar processes affecting different but similar sounds) in order. There's a chance—though not a good one—that I might prod at a couple changes (specifically those in the glide-deleting vein) in the coming days, but what I have right now is solid enough.

Ten sounds like a lot given I've never tried anything similar to this before, but nearly all the sound changes I implemented fall under one of three different multi-step processes, so I'm really just doing four things that all need to be a little spread out. The processes in question:

Stop reduction. For the purposes of creating a few diphthongs, voiceless stops sometimes reduce, very slowly, to nothing at all.

All glides must die. We hardly knew ye. (You may recall that the original phonology only had one glide, [j]. We'll get to that.)

The Consonant Conveyor Belt. An only slightly shaky series of sounds shifting to fill gaps left by those behind them. I must have had something against [g] at the start of the year that I don't have now, and I wanted it back.

Bonus—clean up the ugly sounds. I find [pu] to be an unattractive syllable. That's not the only thing this one gets rid of, but it's most of it.

Complete and lengthy detail under the cut.

Day 31

All three days kind of bled into one another—especially the first two—but day 31 was the one where we were supposed to have a full list of sound changes, if not necessarily an ordered one. I ended up making a few edits yesterday and today, so here's the most current list of sound changes:

Voiceless stops [p] [t] and [k] reduce to [f] [s] and [x] respectively in contexts [a_i], [u_i] and [o_i].

[p] becomes [w] before [u], and before [o] in unstressed syllables.

[d] becomes [g] before [a] and [o], and before [e] in unstressed syllables.

[owo] and [owu] become [ou]. [uwo] and [uwu] become [uo]. [awo] becomes [ao]. [eje] becomes [ei].

[j] vanishes in contexts [a_i], [e_i], and [o_i], as well as [i_o], [i_e], and [i_a]

[j] becomes [ʑ] before high vowels and after [i].

[l] fortifies to [d] before [a] and [o].

[f] and [x] reduce to [h] everywhere they occur.

Glides fortify to [l] anywhere they persist.

[h] is deleted universally where possible. Where not possible, it changes to [ɕ].

If you're looking closely, you might notice a few things:

Why [ɕ] and [ʑ] rather than [ʃ] and [ʒ]? Couple reasons. First, unashamedly, they're fun to say, even if they're not quite sounds I'm all too familiar with in the wild (and I can't distinguish between the two when listening too well...). They're also not sounds I've used in a conlang before—Yvelse has [ ʃ], and I think a couple projects I've left by the wayside did as well. The... interesting conlang idea I mentioned a while back has all four of these, but that's just a concept right now, so it doesn't count. Second, it just made a bit more sense for the sound created in step 10 to be palatal, and I was not about to have two similar sounds in two different places of articulation, one voiceless and one voiced, when I could just put them together. Also, this way the final form of the language uses all the same places of articulation as the original did!

Some of these steps look like they're going to end up tripping over themselves, Strix—unless you want triphthongs or something. Yes. Yes they do (look like that) and yes they do (interfere with themselves). We'll get to that. Incidentally, this is the same force behind that last little bit in step 10.

What do you mean by "where not possible?" Diphthongs are allowed—the set of diphthongs created by these changes is the same as the set of allowable diphthongs—but more than two vowels in a row is forbidden. That little clause is there to stop that from happening if something weird happens between steps 1 and 10.

Hey, you never said anything about where stress goes, but now you're referencing it! I did not! In the proto-forms, primary stress falls as close to the antepenultimate syllable as it can, and secondary stresses radiate out from there, every other syllable. When a word has two syllables, stress lands on the first syllable. I'm ignoring secondary stress when I talk about stress-based sound changes.

Day 32

This was the day where we were supposed to start testing out the changes—though I did a lot of that the day before. I've got a color-coded table where I test a few of the proto-forms I already created—but first, the rules, and some of these are pretty important. For one thing, we can say goodbye to IPA now—at least for the finalized forms of words. Any rules that were only added today (as in, during the "break things" phase) will be in bold.

[j] is represented by y, [ʑ] by j, and [ɕ] by c

Stress-based changes look only to primary stress

Diphthongs shift stress to themselves as soon as they occur (not as though that changes anything, but as a note)

Vowels within diphthongs do not count as single vowels for deletion purposes. They may be considered as single vowels for fortification purposes (the only other context-dependent change that occurs after formation of diphthongs).

If a single step affects multiple parts of a word, work from beginning to end.

And the final phonology:

Day 33

Today's goal was to make a few new forms to "test" sound changes. Of course, "test" as used here means "do your best to break." As such, you'll notice that most of the new forms have three syllables to fit in as many bumps as possible, and the final versions are very diphthong-heavy—every diphthong that wasn't represented in the original chart gets to show up here.

They also tend to hit up several different sound changes. *mijena is maybe the only root that's still pretty similar at the end to the beginning, as opposed to the initial table, where several roots go through only one sound change or none at all.

In my doc, the roots still use IPA as I've been doing for the previous days. Here, I've switched fully to the same romanization system as in the table above, for ease of reading.

*miyena: Companion animal ⇒ miena

*yupuki: Friend ⇒ juoci (This is where that [ɕ] clause comes from.)

*tiyola: Bone ⇒ tioda

*sodeye: Limbless creature (why not?) ⇒ sogei

*kiyapo: Fire ⇒ kijao (Here's where that weirdly specific diphthong rule comes from)

*zapiyo: Time machine (obviously this is a basic root) ⇒ zacio

*lokiye: Tooth ⇒ docie

*dayi: Grain (mass) ⇒ gai

*yupo: Sun ⇒ juo

*yayiyo : Moon ⇒ laijo (And this is why you have to work from start to finish in step 5. This one was fun.)

*nopula: Sky ⇒ nouda

*siyapo: Hair or analogue (as it's possible for an intelligent species to have feathers or somesuch instead of fur) ⇒ sialo

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I am loving Ts' Íts' àsh and how it’s spoken! I’d love to know if you plan on releasing a full breakdown/alphabet type thing because I would love to learn more about it and how to speak it! I’m already learning parts of it and implementing it into my daily speech to get better at speaking it, especially ashfa. Would love to learn more soon!

Best regards, Samuel

If you're talking about the orthography, I did that here. If you mean the sound system and the romanization, I can do that.

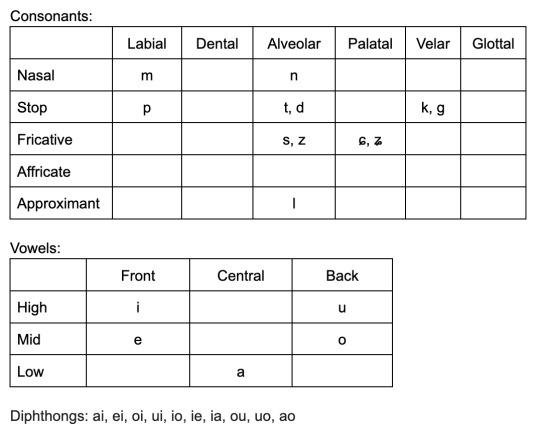

Ts'íts'àsh doesn't have a ton of consonants—very few, in fact. They are as follows (romanized form [IPA]: notes [if any]):

p [p]

b [b]

t [t]

d [d]

t' [t']: this is an ejective consonant

k [k]

k' [k']: this is also an ejective consonant

f [ɸ]: this is a bilabial sound

s [s]

sh [ʃ]

kh [x]

r [r/ɾ]: pronounced like a trill at the beginning or end of a word; otherwise pronounced like a flap

That's it! Nothing too complex. Then there are only four true monophthong vowels:

a [a]

i [i]

o [o]

u [u]

Now this is where things get complicated. Any of the four vowels above or any of the fricatives above can serve as a nucleus. This means you can have a word tkh, psh, or even ss. All of those are licit. You can also have any two vowels in a nucleus—including the fricatives. So while you can only have CVV, you can actually have words like tsá, kshí, or even pskh.

(Small aside: If one of these nucleic fricatives follows an ejective, the ejective marking moves to the right of all the consonants. So a word that begins with k' and then has a nucleus of fó is spelled and pronounced kf'ó.)

There are a number of rules for what happens when two vowels (with vowels including fricatives) come next to one another. The result is too complex to list out in text, so I'm afraid I have to do a table, and since Tumblr doesn't do tables, it has to be visual. Here it is:

So, green means the sequences of vowels are allowed to go together without anything changing. Yellow means the sequence is allowed, but some sort of phonological change occurs. Red means the sequence is disallowed. There is also a general prohibition against three of the same sound in a row, even if one is an onset and two are nuclei. Thus, while ss is licit, sss is forbidden. It is worth noting that several of these vowel-vowel sequences result in monophthongs. This is important for the phonology when it comes to tone assignment. The monophthong sequences are:

*aa > a

*ai > e

*ao/*au > o

*ou/*oo > u

This means that certain instances of the vowels [a], [o], and [u] are phonologically long, and the vowel [e] is also phonologically long (and also brings it up to a five vowel system!). Some other interesting notes:

Long high vowels broke, as in English (so *ii > ai and *uu > au).

The first element of opening diphthongs fortify into a fricative (so *iV sequences become shV and *uV/*oa sequences become fV/fa).

Any time s and sh come next to each other the result is ssh (i.e. [ʃʃ]).

The only consonant f can occur next to as a part of the nucleus is f.

Now, the tones are fairly simple. There are three tones:

High Tone [´]: The vowel is pronounced with high pitch—much the way a vowel is in English when it's stressed.

Low Tone [`]: The vowel is pronounced with low pitch—much the way a vowel is in English when it's unstressed (and also not in front of a stressed vowel).

Falling Tone [ˆ]: The pitch starts off high and falls before leaving the vowel—like when you see a kitty and go, "Awwwwwww!"

How tone is assigned is complex. Good news is if the nucleus is consonantal (just fricatives), there's no tone. Fricatives don't bear tone in Ts'íts'àsh.

The short story for tone is that tone in Ts'íts'àsh came from a combination of an older stress system and cues from onset and coda consonants. An older stressed syllable is called a blaze syllable, and an older unstressed syllable is called a smolder syllable. A smolder syllable will always have low tone unless it has a current or former coda voiceless stop. Then it will have high tone. A blaze syllable can have any tone, but the tone it's assigned depends on the surrounding consonants. Some rules:

If the blaze syllable is open, its tone will be high, unless it begins with a voiced consonant, in which case the tone will be low.

A syllable with one vowel that ends in a voiceless stop will have high tone.

Otherwise, a syllable with a voiced consonant onset will have low tone. The sole exception is a syllable beginning with a voiced consonant that has two vowels and a voiceless stop coda. That syllable will have low tone on the first vowel and high on the second (unless the VV sequence results in a monophthong, in which case the tone is high).

Sequences of two vowels generally have a high-low sequence. The same goes for phonologically long monophthongs.

Coda fricatives will drag tone down.

VV sequences in blaze syllables reduce to singletons in smolder syllables when syllable type shifts in a word (e.g. due to affixation).

And that's all there is to it! It might seem tough to pronounce some sequences we don't have in English, but once you let yourself go and lean into it, it's kind of fun! Jessie and I were both really pleased at how well it was carried off by the actors. They really did a great job!

Thanks for the ask!

#conlang#language#elemental#pixar#pixar elemental#elemental pixar#tsitsash#ts'its'ash#ts'íts'àsh#phonology#phonetics#sir-samuel-iii

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

i love Tauriel as a character concept and generally i’m quite impressed with the Quenya and Sindarin in the Peter Jackson films, but it’s been bugging me for a While that the name Tauriel just. doesn’t work

we have taur, the Sindarin word for “forest”, and -iel, a feminine suffix meaning “daughter”. that’s all well and good. but in Sindarin, the [au] diphthong becomes [o] in polysyllabic words, so it should be Toriel, or possibly Tóriel since the syllable the [au] is in is stressed and it’s followed by a single consonant

but wait! we have Sindarin words like tauron “forester” that keep the [au] diphthong!

that’s true, but that is one of several examples where the [au] is not simplified due to a short [o] or [u] is in another syllable in the word.

there are some examples of words where the [au] is not simplified for no discernible reason, like Naugrim vs Nogrod, both from naug “dwarf”, so it’s possible that this is simply an aesthetic choice, as elves are known to do that especially with names

except that none of that matters because in the Woodland Realm they speak the Silvan dialect of Sindarin, and furthermore Tauriel is Silvan, so really it should be Tawariel

#sindarin#tolkien linguistics#brought to you by#i read the grammar and phonetics sections on eldamo in my free time

44 notes

·

View notes