#formalist theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Feminine Beauty in Art: Evolution and Aesthetics

Throughout the history of art, the concept of feminine beauty has been in a constant state of transformation, evolving alongside the many artistic movements that have defined different epochs.

#abstract concept#aesthetic#aesthetic pleasure#art imitates reality#ARTICLES#artistic movements#beauty in art#classical antiquity#Collections#colour#composition#contemporary art#cultural context#cultural standards#emotional expression#expressive theory#feminine beauty#femininity#formalist theory#historical periods#human experience#mimetic theory#observer&039;s experience#perception of beauty#political movements#Rodrigo Granda#shape#social values#subjective concept

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hi! I don’t know how into philosophy you are (I’m new to your profile, sorry), but I was wondering if you’ve read anything on deconstruction?

yes, while not trained as a philosopher per se but understanding deconstruction in relation to semiotics/textual analysis is a key part of any critical theory/cultural studies education!

Derrida is basically the granddaddy of the movement, and particularly his book Of Grammatology, which I recommend reading slowly and alongside plenty of outside summaries/interpretations to aid in your understanding. basically, Derrida and co argue for a refusal of Platonic Idealism, the idea that there exists an ideal "essence" of things that our terminologies refer back to.

Derrida/deconstructionists, on the other hand, argue for the cultural construction & social contingency of words to their referents; signifiers to the signified, and so on. understanding that language is core to the way we construct our realities, rather than imagining some ur-reality preceding language, is very central to understanding deconstructivism/poststructuralist theory broadly. Deconstructionism in literary theory, similarly, posits that texts don't have inherent, fixed, central "meanings" that can somehow be "mastered" and interpreted "correctly." while this is a very common approach in literary studies now, at the time that it was being developed, it came as quite a shock to more traditional formalist theoreticians.

In addition to the Derrida, Deleuze and Guattari and Foucault are the (very white, very male) titans of postructuralism/deconstruction on philosophical terms. For feminist deconstructivism, you may have already read Judith Butler; also consider Luce Irigaray and Helene Cixous. Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman both approach deconstruction from the perspective of Black literary theory/poetics.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

SEMI-COHERENT MUSINGS ON THE METAPHYSICS OF DELTARUNE

Exploring such topics as: - "what are the Depths?" - "what's with all the water references?" - "why do Darkners know all that stuff?"

Chapters 3 & 4 are fast approaching, the time we have before we’re faced with an influx of novel topics for speculation is running out, and I still have some leftover thoughts on the first two chapters that I'd like to get out there in writing before that happens. These thoughts primarily center around the metaphysics of Deltarune’s diegetic world, and various discursive methods that might be employed to help elucidate its nature.

This will be a loosely structured collection of thoughts that draw heavily from philosophy, literary theory and mythology, so if you don’t like pseudointellectual ramblings this is your warning to close the tab.

All of the points made here will be ancillary to the premises I argue for in my essay titled The Magic Circle. You should probably read it first!

Crossing the Fountain – art vs. byt

Much of my Magic Circle essay is concerned with the almost magical way in which one’s experience of reality is mentally transformed when under the spell of art or fiction. Indeed, this is the source of the essay’s title, and what I argue Darkness in Deltarune represents. I wanted to illustrate this idea a little more.

In the essay, I quoted J. Huizinga’s Homo Ludens – in that book he's talking about games and play specifically, but one of his most salient observations is that play is undergirded by an impulse to abstract from immediate reality that is shared between many branches of culture, including all aesthetic traditions. Huizinga is not the only theorist who noticed that art (which I define to include games and play) is experienced as a break from ‘immediate’ or quotidian experience. Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky posited that art was a transformation of everyday life into its own seperate realm. In his analysis, he put forth an oppositional model between art and what the Formalists called “byt” – an evocative term which could be translated as “life,” but also evokes the way in which life stabilizes into predictable molds.

Within the realm of byt, we experience events causally – and causality, as David Hume famously noted, is at bottom arbitrary. Art, on the other hand, is constructed towards certain ends – it is teleological. In art, essence precedes existence.

In byt, there's material – paper, canvas, film reel, computer code. In art, there are (artistic) devices – stanza, perspective, montage, mechanic.

Byt produces recurring patterns and routines that threaten to turn us into automatons. Art de-familiarizes, jolting us out of the narcotic patterns of everyday experience by presenting us with novelty to reflect on.

Now, you may or may not find this model for understanding art convincing or all-encompassing, but I think it provides a useful idea for understanding Deltarune's metatext.

When we interact with art or fiction, we voluntarily undergo certain illusions. When I read a story, I condition myself to think that I’m reading something that actually happened. When I watch theater, I condition myself to think that the actors are actual people, and the stage is a real environment. When I watch a film, I condition myself to think that the camera doesn’t exist; that it is a window into a different world which is also somehow not of that world. And when I play a (narrative) game, I condition myself to think that I am not interfacing with a program, but a world of its own. Of course, these self-imposed illusions are in no way totalizing. There is always a part of us that remains aware of the artifice. But our experience qua art operates under these illusions – we might say that there is always a part of us experiencing byt too, but this part is marginalized when we’re absorbed in an aesthetic experience.

Some readers might be scratching their heads at what any of this has to do with Deltarune, so I'll make the connection clear: Deltarune itself explicitly formulates Dark and Light – obvious analogues for fiction and reality (or art and byt) – as separate worlds, existing in a similar oppositional balance. Darkness transforms everyday objects – the raw material so to speak – into narrative devices, like characters and settings. In Deltarune there is a dual-reality to everything that comes into contact with Darkness (or the power of art). Might we climb one step up the hierarchy and try to use something akin to this oppositional model to explain the ways in which Deltarune refers to reality from within its fictional domain?

For example, there is the uneasy fact that we are an active force within the narrative, instead of just an invisible spectator. Sidestepping the question of whether the force we’re embodying in the game is supposed to literally be us, the player, at the very least the characters can only understand us in more conceptual terms, as some sort of in-universe deity or anomalous entity. So there’s us – the player – and there’s the Angel – our in-universe embodiment.

So what about the character who contacted us – what about Gaster? In The Magic Circle, I discussed how the information we have about Gaster leads us to think that he exists in some sort of transcendent state as a result of his experiments with Darkness. From that, I extrapolated that Darkness was the fundamental substance underlying Deltarune’s reality (which we can fit into another binary: there’s Darkness, the magical substance that makes up the reality of Deltarune’s world, and there’s what the concept clearly allegorizes: the creative or imaginative capacity of human beings – which is what gave rise to Deltarune, the video game). Gaster’s “transcendent” state trades heavily on video game creepypasta tropes; he’s like a ghost haunting the code of the game. And as it turns out, Deltarune has explicitly made the move to extend its diegesis to its code with the inclusion of a character who seems to be stuck there.

If the code is a part of the diegetic world, we can extrapolate another binary: there’s the code or internal workings of the program, and there’s “the Depths” – a higher (or deeper) metaphysical layer of Deltarune’s world that transcends time and space. Worded differently, the Depths are what we get when the 'eye of the narrative' turns its gaze towards the code of the program.

To close off this section, I want to mention that in Shklovsky’s theories about art and narrative, he makes heavy use of a machine metaphor; he wanted to focus on the ways in which art was a constructed object abiding by its own internal rules. The specific word the Formalists preferred is “device”. In fact, one of Shklovsky’s most well-known essays is titled “Art as Device”. Just something to think about for you Device Theory fans.

Water, Darkness and Chaos as Symbolic Motifs

Water is everywhere in Deltarune. The magical worlds we explore are given form by “fountains” and “geysers”. Onion-san talks of ominous songs under the sea. Ocean.ogg briefly plays after we fall into the supply closet Dark World. And the source image of IMAGE_DEPTH, the background of the GONERMAKER segment, is apparently of an ocean. What gives?

The basic gist is that water has an extremely long and prominent symbolic history in mythology, and figures especially prominently in ancient creation myths. One of the earliest creation myths we have, derived from Enūma Eliš, a Babylonian poem of the 2nd millenium BCE, describes a primordial state consisting of nothing but two deities – Abzu, god of the freshwater ocean, and Tiamat, god of the saltwater sea; from the “comingling of their waters”, all of creation emerges. This is consistent with what we know of ancient near-eastern cosmology in general; they viewed the world as essentially like an air bubble. In the beginning, there was water. Unordered, chaotic, formless. Then, something happens to produce the earth and firmament, both disc-shaped, which separate this cosmic ocean into heavenly waters above the earth (the source of all rain), and lower waters of the deep (the source of all rivers, springs, fountains and geysers).

This cosmological account survives into the Biblical narrative. From Genesis 1:6:

and God said, “Let there be a dome in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.”

The ancient near-eastern flood narrative, which likewise is preserved in the Bible as the story of Noah’s ark, is made less arbitrary with this in consideration; its basis is not merely that drowning in a storm is a scary concept (though it certainly is) – the real symbolic threat of the flood is of a return to pre-creation chaos. The gates of heaven opening and all of creation coming undone. From Genesis 7:11:

In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, in the second month, on the seventeenth day of the month, on that day all the fountains of the great deep burst forth, and the windows of the heavens were opened.

(Sound familiar?)

The idea of water as underlying all reality cropped up not just in religion and mythology, but also philosophy. Thales of Miletus, credited since Aristotle as the world’s first philosopher, famously believed that all of reality was made up of water. Thales and his philosophical successors are sometimes called material monists for their belief that all of reality was composed of a single ultimate substance – the arche from which everything originates.

Thales’s idea was no doubt influenced by the cosmological picture painted by mythology. Though not identical to the near-eastern accounts, the world of ancient Greek mythology is preceded by a state of primordial Chaos – a vast chasm, abyss, or emptiness. Though we in the present day might be tempted to understand Chaos as something like space, ancient commentators such as Pherecydes of Syros interpreted it as water. It was the fluid, formless and undifferentiated nature of water that made it such an enticing candidate for the pre-creation substance.

Chaos was also associated with darkness. Unambiguously born from Chaos are Erebus and Nyx – deified personifications of Darkness and Night. And this is a point of similarity with the ancient near-eastern accounts. From Genesis 1:1-3:

In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.

In short, the primordial state across world mythology tends to be that of an infinitely dark, chaotic ocean.

The parallels to Deltarune are obvious, and having tracked the symbolic history which the game is working with can, I think, lend us a better understanding of "Darkness" as it appears in the game. Needless to say, all of what I've discussed supports the thesis I laid out in The Magic Circle: that Darkness is the arche or prima materia of Deltarune, the underlying substance that its reality is made of. Likewise I think we can intuit what “the Depths” are – simply what in the Hebrew Bible is referred to as “the (great) deep”. A mass accretion of formless Darkness which sits below reality itself. Dark Fountains are formed when the fabric of reality is pierced, creating a gap from which Darkness bursts forth. And since Darkness is the “raw material of reality” so to speak, the Darkness forms a new reality within the old one. But too many holes in reality threaten to “burst the air bubble”, so to speak, and flood the world with Darkness.

I created the above diagram a while back, and used it in The Magic Circle - no doubt you'll notice the similarity between this and the earlier diagram of the Biblical cosmology. The funny thing is that this connection wasn't consciously intended at all; I was barely aware of what the Biblical cosmology was like when I made the first version of this image. That makes me feel like I'm on the right track.

I do want to make something clear; the world of Deltarune isn't necessarily a literal Biblical style air bubble, with a disc-earth and dome sky. The air bubble thing is just for the sake of visualization. I think the Depths are more like a different layer of reality, simultaneously "higher" and "deeper". It's not that there's literally a bunch of dark water under the ground; what Kris is really stabbing is, again, the fabric of "phenomenal" reality itself.

Another thing I want to note; these early mentions by Toby of concepts relating to twilight or the meeting of light and dark have long been a topic of discussion in the community. I want to formulate my understanding of what its significance is.

The first thing God does in the Biblical creation story is summon light. Light meeting the darkness is presented as a precondition to any further creation. Likewise, fiction (darkness) can not exist without an observer in reality (light). The meeting of light and dark is a fundamental condition of art; it can't exist without somone to "shed light on it".

It could also well be referring to the Roaring; when the distinctions between light and dark threaten to dissolve, that is when we must travel to the "edge of the shadow" (the outer boundaries of the dream, near where reality is), and "shatter the twilight reverie" (twilight: when only the sun's afterglow remains) (reverie: being lost in a dream).

On Darkner Knowledge

As established earlier, Darkners are teleological beings whose essence precedes their existence. That is to say, they’re created with an inherent purpose. This purpose is what Ralsei and Queen call “the will of the Fountain” – a guiding force determining the nature of the Dark World and its inhabitants, originating in the Fountain’s creator. In my Magic Circle essay, I used this fact to explain the behavior of Darkners, and why certain ones (like King and Queen) know things that they seemingly shouldn’t (like the fact that the Knight exists, and what their title is). On this latter part, however, I didn’t go into too much detail. Here, I want to elaborate on it a little by invoking an argument made by René Descartes in his Meditations on First Philosophy, known as “the trademark argument”.

(Don’t worry, I’m not actually going to get into the weeds of Descartes’ philosophy. It might be fun to talk about how Descartes’ idea of hierarchical degrees of reality, which consist of infinite substances, finite substances and modes, correspond to Deltarune’s Angel, Lightner, and Darkner hierarchy, but I don’t think it would unearth any particularly useful insights.)

The (very simplified) trademark argument goes something like this: God must exist, because I can conceive of God, his features (that he is an infinite and eternal substance), and the fact that he is altogether more real than I am despite me not possessing this degree of reality. The idea can’t have come from me, but it must have come from somewhere – consequently it must be that I have this idea innately as a sort of “trademark” of my creator.

Now, I very much doubt anyone who's reading this finds the above to be convincing evidence for God’s existence. Thankfully, we aren’t setting out to find out whether God exists or not. The God in this scenario – the Knight – is someone we know exists, and how the relevant knowledge is possessed really does require an explanation (unlike in Descartes' argument, where the notion that an explanation is needed for how we can conceive of the idea of God is dubious at best).

Of course, I don’t mean to imply that the trademark hypothesis is the only possible explanation you could offer. Obviously, you could posit that the Knight entered the Dark Worlds and imparted the knowledge personally. But to do this you’d have to deny the Kris Knight hypothesis, marginalize the religious subtext, assert that there’s no meaning to certain patterns between Chapter 2 and 3 (such as the main Darkner bosses being activated before the Fountain Creation), ignore the latent implications in Queen’s dialogue, among other things – and I’m not interested in doing all that. For the moment, the trademark hypothesis seems much safer, not least of all because it explains other mysterious details too.

Consider the fact that Darkners are aware of the battle system, and know how it works. Do we suppose that someone went around telling each and every Darkner the mechanics of the game? Or does it just make intuitive sense that Darkners would be created with certain ideas that are consistent with their purpose?

Granted, there is still some weirdness left over that we’d have to explain. For example, Darkners – most notably Ralsei but others as well – know about the player’s button configurations. We might be tempted to just chalk this up to the necessities of tutorializing, but the game calls attention to this by having Susie ask questions about it. The trademark hypothesis doesn’t explain why Darkners specifically would be stamped with this knowledge while the Lightners are left out.

The best explanation I can come up with is that since the Dark Worlds are created by Kris, and Kris almost certainly has forbidden meta knowledge imparted by Gaster, the Darkners likewise inherit that knowledge since Kris knows that the player will be controlling them when they go to seal the Fountains, and is aware that we will need some level of guidance.

Conclusion

All right, that’s pretty much everything I wanted to get out there before Chapters 3 & 4 release. Thanks for reading! I hope this wasn’t complete babble to anyone who’s not as knee-deep as I am in random literary theory and philosophy.

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

7, 25, 45

7. What do you like about math?

I like solving the puzzles :3 I love getting intimately familiar with a set of problems, going from groping around in the dark to having an intuitive notion of which avenues are promising to solve a particular problem and which ones would be a waste of time.

I also like carrying around small problems in my mind to solve while walking or in social gatherings where pulling out my phone would be considered a social faux pass.

A neat bonus is using it in videogames! It's nice to optimize my chain of production in Dwarf Fortress and probability is also great in games where outcomes have some uncertainty to them: I've been getting a lot of use out of the notion of expected value and the Law of Large Numbers in Fallen London (whose wiki I recently edited!) for example.

I also love teaching math and using it to help people! When I have some free time I go on reddit and help people with math questions, I especially enjoy when the questions aren't academic in nature. I love when people just need help with math for their everyday life: people trying to use probability to their advantage in some game or people trying to work out dimensions for some home improvement project.

Relatedly, I enjoy teaching math because it almost works the same mind muscles as solving a math problem. Each person that asks a math question usually has some gap in their knowledge or preconception that is hindering their understanding in some way and it's a neat problem to figure out what those are to deliver a tailored explanation to them.

25. Who is your favourite mathematician?

I think as a set theorist my answer is practically forced towards Cantor and Gödel at least. Kunen and Jech are both great too, they each wrote set theory textbooks which are good enough that my cats¹ ² ³ sometimes read them.

For mathematicians I've actually met I'd say my thesis advisor, who is all around a great guy with whom I have a surprising amount of interests in common (besides set theory). Also I have a friend who is easily one of the kindest people I know and she's so unambiguously nice all the time. She's also terminally offline so it's fun to see how shocked she is by the stuff I see here.

45. Are you a Formalist, Logicist or Platonist?

I don't remember the exact definitions of those

¹ Marco reading Kunen's Set Theory

² Pascal absorbing the contents of Kunen's Set Theory via osmosis

³ El Porras doesn't care much for set theory but he throws his weight around over chess boards

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

ask game: 2, 17, 25? 👀

Thank you for asking! 💚

2. Have you ever started a rumour?

Hmmmm no, i don't think so. There are a couple of elaborate lies my friends and i tried to spread but they never really stuck lmao

17. What weird thing do you do when you're alone?

I don't think dancing or having conversations with myself or some imaginary opponent are that weird, right? But maybe i need to start telling myself that the anxious overthinking of my own life and what people think of me is weird, in order to gain some new perspective and stop doing it hmmmm 🤔

25. Favourite niche topic?

Arts, like theatre and film in particular, on an academic level. Like theory and stuff. Not like is it good or not, but like idk formalist film theory or brechtian political theatre, you know? But if you want even more niche than that then i know a lot about the finnish christmas church panics/stampedes of 1669-1882.

Ask me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's a very elementary idea, but there's this thing that plagues me about the need to have a firm knowledge base which is not just the ability to know and recall, but the ability to know that something is wrong.

And that's the thing I keep noticing in the ChatGPT/thinking machines debate. Not just that there's a presumption of consciousness/anthropomorphisation where there isn't, but the reason I'd never put my trust in it is because I would not be able to know when it is wrong all the time, because I have seen it be wrong. I can't learn new topics through it. I'm not diminishing the possibility it may be a tool for those with established knowledge bases (though even in that case I think it could end up being dangerous) and I think, like any other technological shift, there are lots of different human reactions for justifiable reasons, but it does really frighten me that there's this conception of knowledge as a bank in which you store information like a computer (apt!). Stuff goes in, stuff comes out. It's a very reductive view of people and knowledge.

I guess it all comes down to trusting sources as well. You could spend hundreds of hours on YouTube videos and podcasts and reading Reddit forum posts or what have you, and often times it will rarely compare to a few hours spent on a well-written book. Say, you might see people talk about Joseph Campbell; you might see videos made about Joseph Campbell; you might see arguments over the Hero's Journey; you might see critical discussion of the Hero's Journey in other texts; and it will never compare to actually reading the fucking book to know what he's talking about. Same for the male gaze theory (which I've referenced in a similar example before), endlessly, tirelessly brought up over the past decade since seeping into pop cultural consciousness, forum posts and Tumblr posts and video essays expounding upon misogyny in video games and movies and character design etc. etc.: read Visual Pleasure by Laura Mulvey and see if you agree with her. Most of them miss the point. And I think there's an argument to be made that the male gaze isn't inherently evil, either - that is, I disagree with her absolute conclusion and the nature of narrative - which I think is itself interesting! (And in academic discourse this is perfectly permissible: it is not the formalist cure to reading cinema and aesthetics, but obviously there are rightly feminist concerns, which themselves I think suffer from a loss of intellectual inheritance/legacy).

In a way, it's kind of an inevitability of the online information age. So much is available at the touch of a button - and most of it's not very good. It's hard to learn that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. The Politics of Film Theory: From Humanism to Cultural Studies

Prior to its emergence as a distinct academic discipline in the 1970s, film studies could be roughly divided into two distinct but closely-related camps: humanism, which analyzed cinema in terms of its promotion of, or opposition to, classical Enlightenment values (e.g., freedom and progress), and various schools of formalism, which focused on the formal, technical, and structural elements of cinema in general as well as of individual films.[1] As Dana Polan notes, humanist critics frequently vacillated between skepticism toward cinema and profound, even hyperbolic adulation of it (Polan, 1985: 159). To some, film represented “the death of culture for the benefit of a corrupt and debasing mass civilization” (ibid.).[2] To others, film did not kill culture so much as democratize it by destabilizing the privileged, elite status of art (cf., Cavell, 1981). Ultimately, however, “the pro and con positions merge in their common ground of originary presuppositions: they understand art as redemption, transport, utopian offer” (Polan, 1985: 159).

Like the pro-film humanists, formalist critics emphasized the artistic depth and integrity of cinema as genre. (This is especially true of auteur theory, according to which films are expressions of the unique ideas, thoughts, and emotions of their directors; Staples, 1966–67: 1–7.) Unlike humanism, however, formalism was centrally concerned with analyzing the vehicles or mechanisms by which film, as opposed to other artistic genres, generates content. This concern gave rise, in turn, to various evaluative and interpretive theories which privileged the formal elements of film (e.g., cinematography, editing, etc) over and above its narrative or thematic elements (cf., Arnheim, 1997, 1989; Bazin, 1996, 1967; Eiseinstein, 1969; Kracauer, 1997; Mitry, 1997).

In contrast to the optimistic humanists and the apolitical formalists, the Marxist critics of the Frankfurt School analyzed cinema chiefly as a socio-political institution — specifically, as a component of the repressive and mendacious “culture industry.” According to Horkheimer and Adorno, for example, films are no different from automobiles or bombs; they are commodities that are produced in order to be consumed (Horkheimer & Adorno, 1993: 120–67). “The technology of the culture industry,” they write, “[is] no more than the achievement of standardization and mass production, sacrificing whatever involved a distinction between the logic of work and that of the social system” (ibid., 121). Prior to the evolution of this industry, culture operated as a locus of dissent, a buffer between runaway materialism on the one hand and primitive fanaticism on the other. In the wake of its thoroughgoing commodification, culture becomes a mass culture whose movies, television, and newspapers subordinate everyone and everything to the interests of bourgeois capitalism. Mass culture, in turn, replaces the system of labour itself as the principle vehicle of modern alienation and totalization.

By expanding the Marxist-Leninist analysis of capitalism to cover the entire social space, Horkheimer and Adorno severely undermine the possibility of meaningful resistance to it. On their view, the logic of Enlightenment reaches its apex precisely at the moment when everything — including resistance to Enlightenment — becomes yet another spectacle in the parade of culture (ibid., 240–1). Whatever forms of resistance cannot be appropriated are marginalized, relegated to the “lunatic fringe.” The culture industry, meanwhile, produces a constant flow of pleasures intended to inure the masses against any lingering sentiments of dissent or resistance (ibid., 144). The ultimate result, as Todd May notes, is that “positive intervention [is] impossible; all resistance [is] capable either of recuperation within the parameters of capitalism or marginalization [...] there is no outside capitalism, or at least no effective outside” (1994: 26). Absent any program for organized, mass resistance, the only outlet left for the revolutionary subject is art: the creation of quiet, solitary refusals and small, fleeting spaces of individual freedom.[3]

The dominance of humanist and formalist approaches to film was overturned not by Frankfurt School Marxism but by the rise of French structuralist theory in the 1960s and its subsequent infiltration of the humanities both in North America and on the Continent. As Dudley Andrew notes, the various schools of structuralism[4] did not seek to analyze films in terms of formal aesthetic criteria “but rather [...] to ‘read’ them as symptoms of hidden structures” (Andrew, 2000: 343; cf., Jay, 1993: 456–91). By the mid-1970s, he continues, “the most ambitious students were intent on digging beneath the commonplaces of textbooks and ‘theorizing’ the conscious machinations of producers of images and the unconscious ideology of spectators” (ibid.). The result, not surprisingly, was a flood of highly influential books and essays which collectively shaped the direction of film theory over the next two decades.[5]

One of the most important structuralists was, of course, Jacques Derrida. On his view, we do well to recall, a word (or, more generally, a sign) never corresponds to a presence and so is always “playing” off other words or signs (1978: 289; 1976: 50). And because all signs are necessarily trapped within this state or process of play (which Derrida terms “differance”), language as a whole cannot have a fixed, static, determinate — in a word, transcendent meaning; rather, differance “extends the domain and the play of signification infinitely” (ibid, 280). Furthermore, if it is impossible for presence to have meaning apart from language, and if (linguistic) meaning is always in a state of play, it follows that presence itself will be indeterminate — which is, of course, precisely what it cannot be (Derrida, 1981: 119–20). Without an “absolute matrical form of being,” meaning becomes dislodged, fragmented, groundless, and elusive. The famous consequence, of course, is that “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (“There is no outside-text”) (Derrida, 1976: 158). Everything is a text subject to the ambiguity and indeterminacy of language; whatever noumenal existence underlies language is unreadable — hence, unknowable — to us.

In contrast to Marxist, psychoanalytic, and feminist theorists, who generally shared the Frankfurt School’s suspicion towards cinema and the film industry, Derridean critics argued that cinematic “texts” do not contain meanings or structures which can be unequivocally “interpreted” or otherwise determined (cf., Brunette & Wills, 1989). Rather, the content of a film is always and already “deconstructing” — that is, undermining its own internal logic through the play of semiotic differences. As a result, films are “liberated” by their own indeterminacy from the hermeneutics of traditional film criticism, which “repress” their own object precisely by attempting to fix or constitute it (Brunette & Wills, 1989: 34). Spectators, in turn, are free to assign multiple meanings to a given film, none of which can be regarded as the “true” or “authentic” meaning.

This latter ramification proved enormously influential on the discipline of cultural studies, the modus operandi of which was “to discover and interpret the ways disparate disciplinary subjects talk back: how consumers deform and transform the products they use to construct their lives; how ‘natives’ rewrite and trouble the ethnographies of (and to) which they are subject...” (Bérubé, 1994: 138; see also Gans, 1974, 1985: 17–37; Grossberg, 1992; Levine, 1988; Brantlinger, 1990; Aronowitz, 1993; During, 1993; Fiske, 1992; McRobbie, 1993). As Thomas Frank observes,

The signature scholarly gesture of the nineties was not some warmed over aestheticism, but a populist celebration of the power and ‘agency’ of audiences and fans, of their ability to evade the grasp of the makers of mass culture, and of their talent for transforming just about any bit of cultural detritus into an implement of rebellion (Frank, 2000: 282).

Such a gesture is made possible, again, by Derrida’s theory of deconstruction: the absence of determinate meaning and, by extension, intentionality in cultural texts enables consumers to appropriate and assign meaning them for and by themselves. As a result, any theory which assumes that consumers are “necessarily silent, passive, political and cultural dupes” who are tricked or manipulated by the culture industry and other apparatuses of repressive power is rejected as “elitist” (Grossberg, 1992: 64).

A fitting example of the cultural studies approach to cinema is found in Anne Friedberg’s essay “Cinema and the Postmodern Condition,” which argues that film, coupled with the apparatus of the shopping mall, represents a postmodern extension of modern flaneurie (Friedberg, 1997: 59–86). Like Horkheimer and Adorno, Friedberg is not interested in cinema as an art form so much as a commodity or as an apparatus of consumption/desire production. At the same time, however, Friedberg does not regard cinema as principally a vehicle of “mass deception” designed by the culture industry to manipulate the masses and inure them to domination. Although she recognizes the extent to which the transgressive and liberatory “mobilized gaze” of the flaneur is captured and rendered abstract/virtual by the cinematic apparatus of the culture industry (ibid., 67), she nonetheless valorizes this “virtually mobile” mode of spectatorship insofar as it allows postmodern viewers to “try on” identities (just as shoppers “try on” outfits) without any essential commitment (ibid., 69–72).

This kind of approach to analyzing film, though ostensibly “radical” in its political implications, is in fact anything but. As I shall argue in the next section, cultural studies — no less than critical theory — rests on certain presuppositions which have been severely challenged by various theorists. Michel Foucault, in particular, has demonstrated the extent to which we can move beyond linguistic indeterminacy by providing archeological and genealogical analyses of the formation of meaning-producing structures. Such structures, he argues, do not emerge in a vacuum but are produced by historically-situated relations of power. Moreover, power produces the very subjects who alternately affect and are affected by these structures, a notion which undermines the concept of producer/consumer “agency” upon which much of critical theory and cultural studies relies. Though power relations have the potential to be liberating rather than oppressive, such a consequence is not brought about by consumer agency so much as by other power relations which, following Gilles Deleuze, elude and “deterritorialize” oppressive capture mechanisms. As I shall argue, the contemporary cinematic apparatus is without a doubt a form of the latter, but this does not mean that cinema as such is incapable of escaping along liberatory lines of flight.

#cinema#film theory#movies#anarchist film theory#culture industry#culture#deconstruction#humanism#truth#the politics of cinema#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

God I can’t fucking wait for there to be mountains of critical theory about YouTube video essays. I want shit like the YouTube Review. The Journal of YouTube Aesthetic Sociology. I want academic departments. I want 38-page JStor PDFs about heteroglossia in the Roblox oof video. I want Formalist analyses of Innuendo Studios with 55 citations.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been thinking about The Zone of Interest and how its formalist approach is used to to add another layer of meaning to the story or it might actually be the only way through which the story could be understood.

It boils down to stylistic elements like sound editing, shot composion and editing. Perhaps it's easier to understand if I talk about it in opposition to Old Hollywood techniques, but it's more or less the same for current mainstream Hollywood anyway. There's that thing of ''invisible editing'' or more exactly continuity editing. It's made in such a way that the viewer forgets there's cuts in the scene they're watching, creating this illusion of realism in a way. As an audience, we get immersed into the story, without consciously noticing how it's made. Formalist theory in cinema comes in opposition to that, particularly in the second half of the 20th century (French New Wave is a perfect example of playing and changing all the rules).

But coming back to The Zone of Interest, frame composition and editing are done in a way that become not only visible if we pay attention, but they represent the core of it. Almost the entire film is made of full and wide shots, the close-ups are quite rare and the camera is fixed. Apart from one scene in which the camera is following a character in a tracking shot, it's almost always still and from a multitude of angles. It is most visible in the house in which the characters live, with cameras in various places of each room (I think Glazer actually said they added cameras all over the place without any crews around so they captured everything the actors were doing in those spaces, without knowing how they were shot. The had hundreds of hours of footage for editing). This, paired with multiple cuts, shows a deliberate distancing from the characters. It not only brings forth the technicality of the medium, but through that, it reveals the artificiality of the life that is being built there. In a way, we're refused the oportunity to immerse ourselves in something that is actually grotesque and very far from a somewhat idylic or banal life.

Arendt's banality of evil concept has been used for film interpretation many times and has been brought to attention again with The Zone of Interest, but I think it's been misused. There's never the illusion that as evil as it is, those characters are leading a banal life. They are aware that they are trying to build what they consider extraordinary, a new world, one which is adjacent to the horrors that are happening behind the wall that separates them. A wall that that even with the flowers next to it, cannot in any way ''help'' in creating that mundane life because the separation is impossible and the characters are aware of it. It's done very well through sound mixing because its purpose is to reveal the violence auditory. It's constant, day and night, seemingly not affecting those behind the wall, except it does through the constant revving of a motorcycle engine meant to muffle the screaming. There's intent on part of the characters to hide what has it deemed as having no place in their life in that little courtyard with a pool, while through camera angles and sound we're made aware of what is peaking from above or what can be heard constantly. The characters might try to compartmentalize and choose when to engage, but as an audience, we are not in that position.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Arithmetic

The philosophy of arithmetic examines the foundational, conceptual, and metaphysical aspects of arithmetic, which is the branch of mathematics concerned with numbers and the basic operations on them, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Philosophers of arithmetic explore questions related to the nature of numbers, the existence of mathematical objects, the truth of arithmetic propositions, and how arithmetic relates to human cognition and the physical world.

Key Concepts:

The Nature of Numbers:

Platonism: Platonists argue that numbers exist as abstract, timeless entities in a separate realm of reality. According to this view, when we perform arithmetic, we are discovering truths about this independent mathematical world.

Nominalism: Nominalists deny the existence of abstract entities like numbers, suggesting that arithmetic is a human invention, with numbers serving as names or labels for collections of objects.

Constructivism: Constructivists hold that numbers and arithmetic truths are constructed by the mind or through social and linguistic practices. They emphasize the role of mental or practical activities in the creation of arithmetic systems.

Arithmetic and Logic:

Logicism: Logicism is the view that arithmetic is reducible to pure logic. This was famously defended by philosophers like Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell, who attempted to show that all arithmetic truths could be derived from logical principles.

Formalism: In formalism, arithmetic is seen as a formal system, a game with symbols governed by rules. Formalists argue that the truth of arithmetic propositions is based on internal consistency rather than any external reference to numbers or reality.

Intuitionism: Intuitionists, such as L.E.J. Brouwer, argue that arithmetic is based on human intuition and the mental construction of numbers. They reject the notion that arithmetic truths exist independently of the human mind.

Arithmetic Truths:

A Priori Knowledge: Many philosophers, including Immanuel Kant, have argued that arithmetic truths are known a priori, meaning they are knowable through reason alone and do not depend on experience.

Empiricism: Some philosophers, such as John Stuart Mill, have argued that arithmetic is based on empirical observation and abstraction from the physical world. According to this view, arithmetic truths are generalized from our experience with counting physical objects.

Frege's Criticism of Empiricism: Frege rejected the empiricist view, arguing that arithmetic truths are universal and necessary, which cannot be derived from contingent sensory experiences.

The Foundations of Arithmetic:

Frege's Foundations: In his work "The Foundations of Arithmetic," Frege sought to provide a rigorous logical foundation for arithmetic, arguing that numbers are objective and that arithmetic truths are analytic, meaning they are true by definition and based on logical principles.

Russell's Paradox: Bertrand Russell's discovery of a paradox in Frege's system led to questions about the logical consistency of arithmetic and spurred the development of set theory as a new foundation for mathematics.

Arithmetic and Set Theory:

Set-Theoretic Foundations: Modern arithmetic is often grounded in set theory, where numbers are defined as sets. For example, the number 1 can be defined as the set containing the empty set, and the number 2 as the set containing the set of the empty set. This approach raises philosophical questions about whether numbers are truly reducible to sets and what this means for the nature of arithmetic.

Infinity in Arithmetic:

The Infinite: Arithmetic raises questions about the nature of infinity, particularly in the context of number theory. Is infinity a real concept, or is it merely a useful abstraction? The introduction of infinite numbers and the concept of limits in calculus have expanded these questions to new mathematical areas.

Peano Arithmetic: Peano's axioms formalize the arithmetic of natural numbers, raising questions about the nature of induction and the extent to which the system can account for all arithmetic truths, particularly regarding the treatment of infinite sets or sequences.

The Ontology of Arithmetic:

Realism vs. Anti-Realism: Realists believe that numbers and arithmetic truths exist independently of human thought, while anti-realists, such as fictionalists, argue that numbers are useful fictions that help us describe patterns but do not exist independently.

Mathematical Structuralism: Structuralists argue that numbers do not exist as independent objects but only as positions within a structure. For example, the number 2 has no meaning outside of its relation to other numbers (like 1 and 3) within the system of natural numbers.

Cognitive Foundations of Arithmetic:

Psychological Approaches: Some philosophers and cognitive scientists explore how humans develop arithmetic abilities, considering whether arithmetic is innate or learned and how it relates to our cognitive faculties for counting and abstraction.

Embodied Arithmetic: Some theories propose that arithmetic concepts are grounded in physical and bodily experiences, such as counting on fingers or moving objects, challenging the purely abstract view of arithmetic.

Arithmetic in Other Cultures:

Cultural Variability: Different cultures have developed distinct systems of arithmetic, which raises philosophical questions about the universality of arithmetic truths. Is arithmetic a universal language, or are there culturally specific ways of understanding and manipulating numbers?

Historical and Philosophical Insights:

Aristotle and Number as Quantity: Aristotle considered numbers as abstract quantities and explored their relationship to other categories of being. His ideas laid the groundwork for later philosophical reflections on the nature of number and arithmetic.

Leibniz and Binary Arithmetic: Leibniz's work on binary arithmetic (the foundation of modern computing) reflected his belief that arithmetic is deeply tied to logic and that numerical operations can represent fundamental truths about reality.

Kant's Synthetic A Priori: Immanuel Kant argued that arithmetic propositions, such as "7 + 5 = 12," are synthetic a priori, meaning that they are both informative about the world and knowable through reason alone. This idea contrasts with the empiricist view that arithmetic is derived from experience.

Frege and the Logicization of Arithmetic: Frege’s attempt to reduce arithmetic to logic in his Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (Basic Laws of Arithmetic) was a foundational project for 20th-century philosophy of mathematics. Although his project was undermined by Russell’s paradox, it set the stage for later developments in the philosophy of mathematics, including set theory and formal systems.

The philosophy of arithmetic engages with fundamental questions about the nature of numbers, the existence of arithmetic truths, and the relationship between arithmetic and logic. It explores different perspectives on how we understand and apply arithmetic, whether it is an invention of the human mind, a discovery of abstract realities, or a formal system of rules. Through the works of philosophers like Frege, Kant, and Leibniz, arithmetic has become a rich field of philosophical inquiry, raising profound questions about the foundations of mathematics, knowledge, and cognition.

#philosophy#knowledge#epistemology#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#Arithmetic#Philosophy of Mathematics#Number Theory#Logicism#Platonism vs. Nominalism#Formalism#Constructivism#Set Theory#Frege#Kant's Synthetic A Priori#Cognitive Arithmetic

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

god youre so smart and articulate!!!! i wanted to ask if you had any formal higher education, specifically in the arts or philosophy. or have you done any independant readong of your own, specially in regards to the vanguards of the xx century, like the russian formalists? im eerily reminded of them ocasionally when reading your thoughts about art, but maybe thats some programs of a literary theory class coming back to haunt me.

i just have a drawing/painting degree from UNR. thank you though. very kind

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

“Starburster” by Fontaines D.C.

MG:

At the time when I was mostly unfamiliar with both, I felt like Fontaines D.C. was maybe like the post-punk equivalent of the Sally Rooney novels. The Sally Rooney novels, I’d gathered, were like romance novels for the repressed and it was that chilly uptightness that made them debatably literary. Fontaines are like romance music for the fucked up – dark, truculent, wry sense of humor – and after a handful of singles I felt like they were debatably high art. I read Normal People last year and, like, yeah. It is a romance novel for the chronic anxiety and depression set. It’s better than that too – there’s a way that Rooney is able to capture the effete ennui of the rich and the numb rage of the not rich in stylistic choices alone, but you could also just read Edith Wharton because the times they have not changed so much. Fontaines D.C. maybe could be characters in a Sally Rooney novel. They’re entering their fourth album cycle with “Starburster,” a song that is by parts “Radioactive” by Imagine Dragons and “With or Without You” by U2. These are big changes for the band that previously hewed very closely to a formula of a windowless room with an uncomfortable chair and a single lightbulb descending from the ceiling. It’s brighter, more colorful, as the title suggests. But it’s also tinted with a more obvious sense of desperation. For attention, maybe, or an agenda. The song doesn’t hit its stride until it shells its pretense and unfolds like so many soft petals into a sonorous interlude courtesy of Grian Chatten. His voice is simply undeniable, slightly raw and yearning, intimately vulnerable. It’s the stuff of transcendence, rising above class warfare and ill fated soulmates and the politics of the era.

DV:

The only Fontaines D.C. song I know is last year's "Fairlies", which isn't actually by them but did unexpectedly win me over when I gave it a shot. I was expecting something very similar from Chatten's group work, which meant "Starburster" caught me by surprise. But maybe it would have done that anyway - it seems designed to resist expectations, with its false start and the alternate world of its extended bridge. I'm left with the impression that Fontaines D.C. are a band concerned primarily with formalist experiments and less interested in lyrics, the exact opposite idea of them I held after "Fairlies." This is intriguing if true! There aren't that many of those left, let alone putting out compelling music (Gang of Youths comes to mind as an example of one that manages it.) Based on "Starburster", I can only deduce that Fontaines D.C. are like Gang of Youths but more nasally. I will not be confirming this theory through any kind of research beyond this web site.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

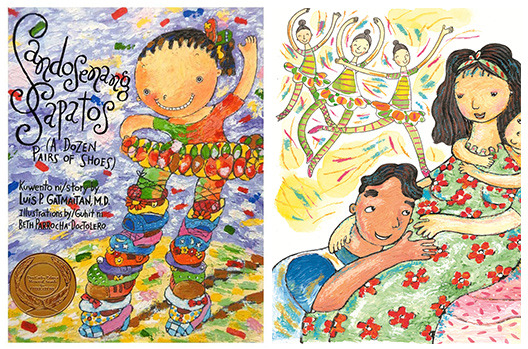

Heart and Sole: A Tri-Theory Literary Critique of Gatmaitan's Sandosenang Sapatos

Written by: Delos Santos, Cindy Etom, Airah Clare Nufable, Cleshen Panal, Mark Jade Pido, Zyron Sabado, Clark Ivan Santos, Hannah Levee

“Alay ko ang kuwentong ito sa lahat ng batang kinapos ng damdamin at kaluluwa, at sa kanilang nagkulang ng isang kamay, isang paa, isang daliri, isang mata. [I dedicate this story to all of the children who are lacking in feeling and soul, and to those who are missing a hand, a foot, a finger, and an eye.]” — Luis P. Gatmaitan, M.D.

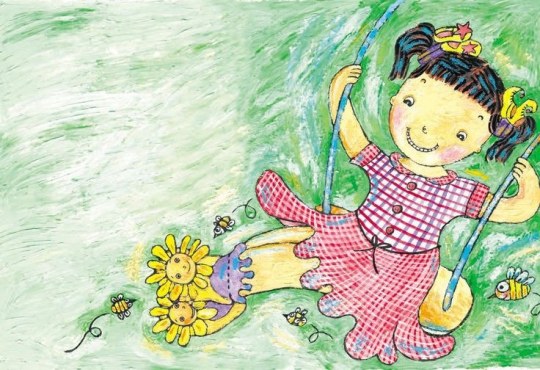

In Gatmaitan's poignant narrative, "Sandosenang Sapatos," the readers are introduced to the world of a character called “Tatay”, a skilled shoemaker renowned in their town for crafting exquisite footwear. The story revolves around the central character, Karina, Tatay's daughter, who grows up surrounded by the intricacies of her father's craft. In this literary critique, the readers will explore the narrative through the lenses of Formalism, Psychological, and Biographical theories, in order to unravel the layers of symbolism, character motivations, and the profound influence of the author's own experiences on the story itself.

Formalism involved scrutinizing the story's structure, language, and stylistic choices. Gatmaitan's portrayal of Tatay's craftsmanship, the vivid descriptions of the shoes, and the recurring motif of footwear become essential elements to explore. On the other hand, through the lens of Psychological theory, the readers analyze the characters' inner workings and motivations. The emotional journey of the characters, especially Susie, Karina's sister who was born without feet, opens avenues to understand the psychological impact of physical differences and the resilience of the human spirit.

Meanwhile, Biographical theory provides a unique perspective as we consider Gatmaitan's own background and experiences. The author, who is also a pediatrician, infuses the narrative with themes of love, acceptance, and the complexities of parenthood. The biographical lens offers insights into how Gatmaitan's professional expertise and personal encounters may have shaped the portrayal of medical challenges and familial bonds within the story.

Through these three lenses, the readers aim to unravel the complexities of "Sandosenang Sapatos," examining not only its formal elements and psychological depth, but also understanding the impact of Gatmaitan's own life experiences on the creation of this heartfelt short story.

First, for the formalistic approach, the short story used the first person as its point of view. It utilized the pronouns “ako [I]”, “ akin [my]”, and “kami [we]” throughout the story. With these pronouns, the readers analyzed that the story was written based on the character’s perspective, which is Karina. Along with this, as the story progresses, the readers observe that the events are based on her experiences with her classmates, other people, and mainly, her family.

For the setting, the story is situated in a town where Karina and her family live. Their home symbolizes love and strength, showing how they support each other despite the challenges. Through the setting, the story explores the contrast between dreams and reality, particularly through Susie's dreams of beautiful shoes and the harsh realities of her disability. The setting not only provides a backdrop but also deeply influences the emotional atmosphere, allowing the readers to empathize with the characters journey of love, loss, and acceptance within their family and community.

For the structure, it is characterized by its plot, set in a town where the characters are introduced. As the plot develops, the readers can gain insights on what is happening in the family and the significance of the shoes as a symbol in the story through the first-point of view of the narrator. The narrator's viewpoint focuses on her interactions with her father and sister, Susie, providing readers with a deeper understanding of the events unfolding within the family. Additionally, symbolism is woven into the narrative, with shoes representing various themes, including identity, hope, and the bond between family members. Also, the setting provides context for the events that unfold, including societal judgment and the challenges faced by Susie's disability. Through its structure, the story effectively conveys its themes and messages, highlighting the importance of unconditional love and acceptance within a family amidst life's trials and tribulations.

For the characters, it involves Karina, her father, her mother, and Susie. Karina, who is the main character and the one who is narrating the story, is a loving daughter and sister. She is willing to do anything to make her family happy, especially her father. She is willing to go beyond her limits just to fulfill her father's dream. This is evident in the part of the story when Susie was born with deformities, and now cannot fulfill her father's dream for her to become a ballerina. Now as a loving daughter, even if she did not like ballet, she still decided to persuade her mother to enroll her in a ballet school. Moreover, Karina is a loving sister. Despite Susie's deformities, she did not treat her differently. She is willing to adjust and stand up for her. She became her wheelchair assistant and defender against her bullies. Furthermore, Susie’s condition never became a hindrance for them to make a strong bond. They found a lot of games that did not require the use of feet. With Karina’s statement, which is “Lagi nga niya akong tinatalo sa sungka, jackstone, scrabble, at pitik-bulag. [She always beats me in sungka, jackstone, scrabble, and pitik-bulag.]”, the readers understood that they really have a good relationship with each other.

In addition, Karina’s father, a supporting character, is a skillful shoemaker. He is well-known in their town for making creative, durable, and excellent shoes. It can be supported with Karina’s statement, which is “Ayon sa mga sabi-sabi, tatalunin pa raw ng mga sapatos ni Tatay ang mga sapatos na gawang-Marikina. [From what we heard, my father’s shoes were so much better than the shoes made in Marikina.]”. Tatay is also a loving father. Aside from the fact that he always made shoes for Karina on different occasions, he showed his love for his family in many ways. He is always willing to protect them from other people, especially when Susie got bullied by a guy when they went on a picnic. He even told Susie one bed time that he and her mother will always love her even if she had no feet. Most importantly, his love is unconditional. Knowing Susie’s condition, he still made shoes for her even if he knows that Susie cannot wear these. With his love and talent for shoemaking, he also wants Susie to be part of what he always does by making her beautiful shoes.

Karina’s mother, who is also a supporting character, is a loving mother. Same with her father, she is willing to keep her family from harm and did not treat Susie differently. The last character, who is Susie, is Karina’s little sister. Even if it is not her perspective, she is also considered as a main character since the story mainly revolves around her. Susie is born with deformities, in which she had no feet. However, her family showered her with the love she needed, and even more. Her family always makes her feel that she is very special and there is nothing wrong with her.

Each character has a significance in the story since each of them contributes to it as a whole. For the plot, the story introduces Karina’s father as a famous shoemaker in their town. His father made her many exceptional shoes for every occasion such as Christmas, birthdays, school openings. Now as the story goes on, it introduces her mother who got pregnant when she was in second grade. After her little sister, Susie, was born, they found out that she had deformities. This marks the beginning of the conflict, as her father's dream for Susie, to become a ballerina, crashes. To sum all things, each character really has a crucial role that makes the story as a whole.

Furthermore, the use of imagery is present in the story. It is highly evident when Karina described the shoes that her father made for Susie. She used the description such as “dilaw na tsarol na may dekorasyong sunflower sa harap [yellow patent leather shoes with sunflower upfront]”, “kulay pulang velvet na may malaking buckle sa tagiliran [red velvet shoes with a big side buckle]”, “asul na sapatos na bukas ang dulo at litaw ang mga daliri [blue open-toed shoes with her own toes peeking through]”, and many more. With this, while the readers were reading the story, the words used by Karina helped them to have an image painted in their minds on what the shoes would look like. Moreover, imagery is also used when Karina and her family went to the park for a picnic, and encountered a guy that criticized Susie for her condition. With the statement “Biglang namula si Tatay sa mga narinig. Tumikom ang mga kamao. [My father turned red. He clenched his fist.]”, the readers can visualize her father’s face in that situation. Through this imagery, the readers can imagine how mad he was with the guy that insulted his daughter.

In summary, "Sandosenang Sapatos" employs a formalistic lens that brings out the narrative's core. The use of first-person perspective, with pronouns like "ako" and "akin," roots the story in Karina's viewpoint, highlighting her experiences with family and the town. The setting, portraying a town marked by love and resilience, contrasts dreams and realities, notably Susie's aspirations against the challenges of her disability. The plot unfolds dynamically, shedding light on family dynamics and the symbolic role of shoes. Characters, from Karina's devotion to her father's shoemaking and Susie's resilience, play essential roles. Imagery, especially in describing Susie's shoes and intense moments, offers a visual connection for readers. "Sandosenang Sapatos" is a straightforward exploration of love, identity, and acceptance, prompting readers to engage with the emotional aspects within family and societal contexts.

Second, looking at the text using a psychological lens imparted to the readers what may be going through the characters' minds as the story progresses, especially the turmoil created by physical differences, and how familial love and the indomitable human will rise above these difficulties.

The characterization of Tatay in the story, particularly his passion for shoemaking and love of family, is a recurring theme, despite people insulting his daughter Susie as seen in the line “Tingnan n’yo o, puwedeng pang-karnabal ‘yung bata!”, or being the topic of gossip, as people try to create fantastical and unbelievable reasons why Susie was born without feet, he continues to create shoes for her regardless, showing his motivation to provide and care for his family, and his motivation to push through struggles in life.

Karina also follows the same thread, and this can be shown through her self-sacrifice, wanting to learn ballet to fulfill the dreams of her father, playing with her sister through games that do not need feet, defending her from bullies, pushing her wheelchair, and generally assisting her. Her dedication and grit once again triumphs over difficulties.

Nanay’s character also shows resilience and love all in the midst of all the adversity. “Nagkaroon kasi ako ng impeksyon anak.” Her inability to stop Susie's illness causes her to feel guilty and sad. She also experiences psychological effects from the gossip and judgment from society over Susie's condition, including a strong desire to protect her daughter from harm and protective instincts.

Susie is portrayed as a strong, creative person who finds comfort and happiness in her aspirations and goals. Susie's fantasies about these intricate and exquisite shoes show the psychological effects of growing up with a physical impairment. She may be using these dreams as a coping method, escaping the confines of her physical reality and finding solace in an idealized version of herself with a perfect pair of feet.

The recurring theme of Susie's dreams about shoes also indicate a longing for a sense of normalcy and the desire to experience activities she might not be able to in reality, such as wearing the ballet shoes her father wants her to have. Her ability to find joy in small moments, and her creative imagination are notable aspects of her character that reflected these coping strategies that yielded her to have a positive outlook in life.

The psychological lens reveals in the narrative the struggle, coping strategies, resilience and love of the characters. Tatay with his undying determination of making shoes for Susie despite her complications, Karina sacrificing her own ideals just to make his father’s wish come true, Nanay grapples with the emotional weight of Susie's condition and societal judgments, while Susie uses her dreams and imagination as a means of navigating and finding happiness in a world that sometimes fails to understand her.

Finally, the readers analyze the short story through the third and last literary theory lens, which is the Biographical Lens. This lens unveils a deeper layer of understanding as the readers examine the author's life, experiences, and personal context. This lens allows proper analysis of how the author's unique background and journey may have influenced the narrative, characters, and thematic elements within the short story. In this case, the readers explore the life of Dr. Luis P. Gatmaitan, the Filipino author of “Sandosenang Sapatos”.

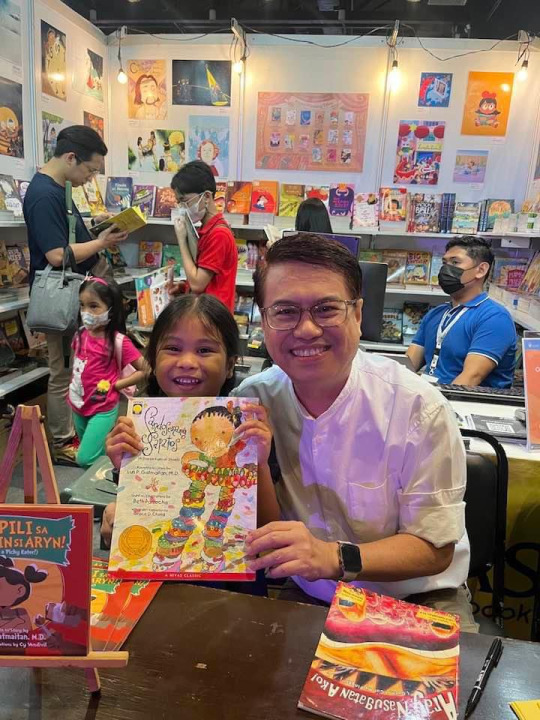

Luis P. Gatmaitan, M.D., widely known as “Tito Dok” to his readers, has written more than 40 children’s books. Aside from being a Filipino children’s author, Tito Dok is also an accomplished medical doctor specializing in pediatrics. Currently, he chairs the Philippine Board on Books for Young People (PBBY), and is part of the National Council for Children’s Television (NCCT) as a child development specialist (Monde, 2022). Both of these positions are highly notable, as they serve as evidence for Tito Dok’s passion for pediatric healthcare and literary education.

Most of Tito Dok’s books contain themes that revolve around differently-abled people, senility, adoption, coping with death, coping with cancer, childhood diseases, and children’s rights. One of his popular works is “Sandosenang Sapatos” or “A Dozen Pairs of Shoes”. This particular book has won him an award in the 2001 Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature, which are a set of literary awards for Philippine writers. Furthermore, “Sandosenang Sapatos” was named the 2005 Outstanding Book for Young People with Disabilities by the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), which showcases the global impact of Tito Dok’s work. Recently, the short story was also featured as a musical play, solidifying its place in the Philippine literary industry.

Tito Dok’s inspiration for writing this short story can be traced back to when he attended a training course in creating non-fiction books for young people in Japan. The author was amazed by how the Japanese people respected those with mobility issues, leading him to have an idea of writing about these kinds of people. One time, he had a patient who was born without feet. Tito Dok then thought, “What if this child was born to a father who worked as a shoemaker?" This then led to the writing of the aforementioned short story.

Tito Dok possesses a wide knowledge of medical information, which was evident in his writing. In his work “Sandosenang Sapatos,” the readers have read the part where Susie’s mother disclosed to her eldest, Karina, that she had German measles while she was carrying Susie, resulting in her youngest daughter to be born without feet. This particular scenario reflects the expertise of the author in the medical field. As a doctor himself, Tito Dok must have studied or witnessed that illnesses during pregnancy, such as German measles, could lead to birth defects (Leonor & Mendez, 2023).

In the short story, despite missing her lower limbs, Susie grew up in a loving and caring family who never treated her less for being differently-abled. The author came up with this particular character trait after observing that “Some children grew up to be physically whole but emotionally disabled, or physically disabled but physically whole”. The author was able to convey this personal message to the readers, instilling hope in others about physically challenged people like the short story’s Susie.

In conclusion, "Sandosenang Sapatos" by Luis P. Gatmaitan is a narrative that explores the concepts of human emotion, resilience, and familial love. The author's dedication, expressed in the heartfelt dedication to children facing physical challenges, sets the tone for a narrative rich in depth and compassion. Through the lenses of Formalism, Psychological theory, and Biographical insights, the readers have unraveled and given an in-depth critique and analysis of the work.

The lens of Formalism unveiled the structure of the story, with a first-person perspective amplifying Karina's experiences, while vivid descriptions of shoes become symbolic threads woven throughout the narrative. Psychological theory invited readers into the minds of characters, exposing their struggles, coping strategies, and unwavering love in the face of adversity. The characters - Karina, Tatay, Nanay, and Susie - each contribute significantly to the plot, portraying a resilient family facing life's trials with unconditional love.

And of course, the Biographical lens adds another layer of understanding, showcasing Dr. Gatmaitan's dual roles as a renowned pediatrician and a prolific children's author. His background in pediatric healthcare is reflected in the narrative's accurate portrayal of medical conditions, emphasizing the author's commitment to educating young minds. The story's origins in Tito Dok's encounter with a patient born without feet add a personal touch, infusing the tale with authenticity and empathy.

"Sandosenang Sapatos" stands as a testament to the power of storytelling to foster understanding, empathy, and hope. Dr. Gatmaitan's masterful blend of literary prowess and medical expertise creates a narrative that resonates beyond its pages, leaving an indelible mark on readers' hearts and minds. Through the holistic combination of formal elements, psychological depths, and biographical influences, the readers gain a comprehensive appreciation for the layers of meaning embedded in this heartfelt short story, celebrating the strength of the human spirit and the enduring bonds of family.

#sandosenangsapatos#literary criticism#literary critique#formalism#psychological approach#biological approach

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

formalists are so. like i love them i think they’re great but girl what the hell. “context matters not only content” is like bad w fiction but WORSE w theory. like, come on, yeah the author was a bit dramatic and got goofy with the absolutes but brother be real wouldn’t you? it’s so much effort to introduce a theory or course of action based on theory and yeah ur probs like excited about it and ur probs gonna say “always” and like formalists or formalist sympathizers are gonna get SO mad a u in a few years but you were just getting goofy!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avatar: The Last Airbender, the Formalist Symbolism of Shot Composition

Link to Video Essay

The series, Avatar: the Last Airbender, remains one of the most critically acclaimed animated shows over a decade after its original debut in 2005. Intricate world-building, an immersive score, and themes of genocide, totalitarianism, Stockholm Syndrome, redemption, and spiritual balance are partially what cultivate and cement ATLA’s memorability to a degree that prompts recognition from outlets such as Vanity Fair, IndieWire, and general audiences years after its premier. It is a heroes’ journey about restoring balance, cross-cultural understanding, and peace after the Fire Nation waged war. However, it is also filled with striking visual storytelling, its awareness of semiotic significance and the delicacy through which it handles visual rhetoric.

While lighting, camera angles, and shot composition are used as formalist signifiers throughout the entire show, I will specifically be focusing on the scene where Zuko visits Iroh in the jail cell. For context, Zuko has been accepted back into the Fire Nation by conforming to their current ideals of ethnocentrism and helping their efforts in the war. Simultaneously, Iroh has been othered and imprisoned for treason because of his rejection of these same ideals. Thus, we know contextually that the two characters are performing and interpreting their racial identities differently. The composition of the scene through its lighting and camera angles, however, adds another layer of commentary to the duality of these two characters. It communicates that while Iroh is physically othered and imprisoned for his enlightened perspective on what it means to perform his racial identity, Zuko is embraced and accepted for his antithetically ignorant perspective on the Fire Nation.

Through its use of light and dark imagery as symbolic concepts within the scene, ATLA demonstrates what Sergei Eisenstein describes as “a cinema that seeks the maximum laconicism in the visual exposition of abstract concepts” in his article, “Beyond the Shot [The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram].”[1] The light streaming in from the small window in Iroh’s prison cell represents the concept of enlightenment and awareness while Zuko kneels helplessly in the shadows. This is a subversion of expectations, as Iroh is imprisoned, looked down on, and othered within his nation, yet the light implies he should be treated antithetically. The role reversal between the isolated yet enlightened prisoner and the idolized yet ignorant prince is further emphasized through the stark duality of light and shadow. Eisenstein describes the composition of shots and visual symbolism as a necessary type of collision, writing “What then characterizes montage and, consequently, its embryo, the shot? Collision. Conflict between two neighboring fragments. Conflict. Collision.”[2] Few visual elements mirrored across hundreds of years of symbolic imagery more aptly demonstrate conflict and collision within a shot than the light and the dark—the collision, conflict, and interplay between shadows and the sun that expels them.

Applying the argument for collision within a shot to lighting specifically, Eisenstein states, “The same applies to the theory of lighting. If we think of lighting as the collision between a beam of light and an obstacle, like a stream of water from a fire hose striking an object, or the wind buffeting a figure, this will give us a quite differently conceived use of light from the play of ‘haze’ or ‘spots.’”[3] Through this framing, there is not only the existence of light and shadow within a shot but a battle between them—an apt description considering the broader plot of war between ethnocentrism and cross-cultural unity that permeates Avatar’s world, as well as Zuko and Iroh’s representations of these ideologies respectively. Light and shadow can coexist, yet this coexistence is constantly implicated with the power struggle between the two. Avatar’s shots in the prison scene put light and dark imagery similarly in conflict, further explaining why one must be othered and the other accepted by their nation.

Eisenstein explains, however, that these abstract concepts necessitate an intertextual basis that grounds them in signified meaning. Speaking to how visual signifiers develop culturally understood meanings over time and in relation to the context clues around them, Eisenstein writes that within forms like the Haiku and Tanka, “The method, reduced to a stock combination of images, carves out a dry definition of the concept from the collision between them.”[4] Avatar’s visual rhetoric plays out similar to poetic communication, drawing on the idea that shadows and light, when placed together create meaning. Bolstering the significance of this collision with the shot is a history of cultural ideas and philosophical texts that perpetuate similar associations. Eisenstein recognizes how this type of intertextuality strengthens symbolism, writing, “The same method, expanded into a wealth of recognized semantic combinations, becomes a profusion of figurative effect.”[5] The integration of atramentous and brightened hues into common modern cultural perceptions is seen through how it manifests in language, with common expressions like being in the dark.

One may question how the depth of the scene's commentary about enlightenment and ignorance can go much further past this stark dichotomy, as the conceptualization of light and darkness arguably only allows for a black-and-white interpretation of Iroh and Zuko's characters. However the meaning behind the use of shadows is strengthened even further when considering what is perhaps the most famous use of dark and light symbolism across millenia—Plato’s acclaimed allegory of the cave. Plato paints a visual picture of prisoners who live in an underground cave and can only see a wall where the shadows of various objects are projected. Thus, they believe shadows to be reality. Once a prisoner escapes and sees not only the objects that were originally creating the shadows, but also the sun above, he is described as enlightened, having a fuller view of reality.