#freya stark

Text

On the whole, age comes more gently to those who have some doorway into an abstract world-art, or philosophy, or learning-regions where the years are scarcely noticed and the young and old can meet in a pale truthful light.

— Freya Stark, Perseus in the Wind: A Life of Travel (John Murray, 1948)

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non ci può essere felicità se le cose in cui crediamo sono diverse dalle cose che facciamo.

Freya Stark

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inspired by British-Italian explorer Freya Stark, Elise Wortley traveled through Iran's Valley of Assassins for three weeks in the spring of 2022.

via Smithsonian

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I had to write a decalogue for journeys, eight out of the ten virtues should be moral, and I should put first of all a temper as serene at the end as at the beginning of the day. Then would come the capacity to accept values and to judge by standards other than our own. The rapid judgement of character; and a love of nature which must include human nature also. The power to dissociate oneself from one’s own bodily sensations. A knowledge of the local history and language. A leisurely and uncensorious mind. A tolerable constitution and the capacity to eat and sleep at any moment. And lastly, and especially here, a ready quickness in repartee.

- Freya Stark, A Winter in Arabia: A Journey Through Yemen

#stark#freya stark#quote#travel#desert#exploration#explore#femme#icon#journey#arabia#yemen#middle east#Author#wanderlust

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

31st January

“To awaken quite alone in a strange town is one of the most pleasant sensations in the world. You are surrounded by adventure.”

- Freya Stark

Happy birthday Freya!

0 notes

Text

There can be no happiness if the things we believe in are different from the things we do.

Freya Stark

0 notes

Text

Quotes To Live By: Freya Stark

“There can be no happiness if the things we believe in are different from the things we do.”

Freya Stark

Image: Canva

View On WordPress

#Canva#everydayinspiration#grounded#groundedafrican#happiness#quoteoftheday#saturdayquote#wisdom#alignment#Book Quotes#follow your heart#Freya Stark#The Journey’s Echo

0 notes

Text

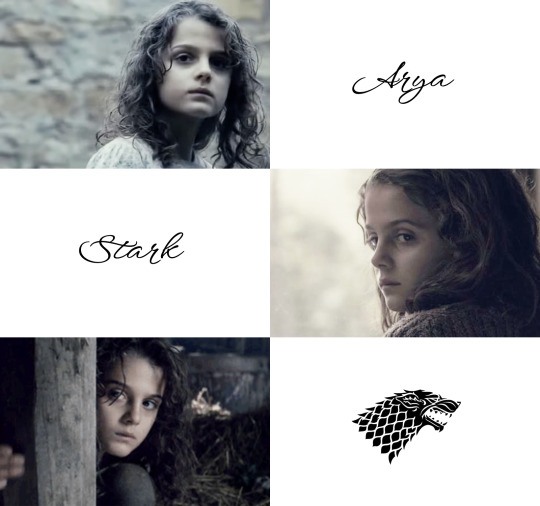

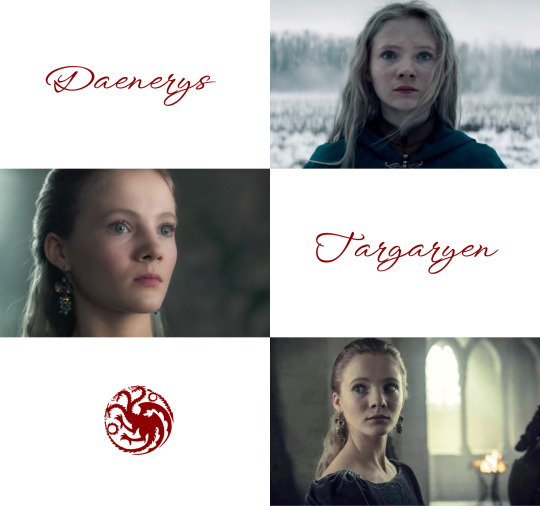

— Daenerys & Arya Parallels 🐉🐺

A Clash of Kings - Daenerys I / A Game of Thrones - Arya II / A Dance with Dragons - Daenerys III / A Feast for Crows - Arya II

#daenerys targaryen#arya stark#canondany#canonarya#house targaryen#house stark#daenerystargeryenedit#aryastarkedit#a song of ice and fire#asoiaf#asoiafedit#canon asoiaf#asoiafwomensource#daenerys fc: freya allan/elle fanning/gaia weiss#arya fc: rebecca emilie sattrup/raffey cassidy/mackenzie foy#lynesse fc: rosamund pike#lyanna fc: olivia hussey

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

REDRAW TIME!

3-year difference ;0;!

#You don't know how proud I am of myself#I CAN SEE IMPROVEMENT AAAHH#I haven't really had this feeling much about my art#yeah I know I've come far but this is the literal first time in years I've redrawn a piece and....#gosh#I'm so fuckin' proud of myself dude#yeah I need to work on humans bc this in comparison to my human art is really a stark difference lmfao#but jesus christ dude I feel down about my art so much that seeing this and getting a reality check marks this as my favourite piece of thi#year by FAR GAHHH#freya crescent#final fantasy#final fantasy 9#final fantasy ix#ff9#ffix#my art

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 - Three Very Important Words

Part 20

The Last Velaryon

Tag list @rise-my-angel @cdragons @kmc1989 @starkleila

Spinning around on my feet throwing my hair over my shoulders I eyed my husband seeing his hands clenched at his sides. “Robb, please don’t be angry with me over speaking to Walder Frey without telling you I was going to in the first place.”

“Oh I have every right to be angry with you. We’re supposed to be a team, Haelesa.”

I parted my lips, releasing a breath. “We are still a team, Robb.”

“It didn’t appear that we were out there in front of Walder Frey and his household. It looked like we had completely different plans in mind and didn’t communicate that to one another.” He threw his hands away from his sides in frustration.

“I’ll take full responsibility for the miscommunication. With that said, may I tell you of my plan that I wanted to propose to him?”

Robb gestures with his right hand. “Continue, my lady.”

“Robb, those girls all deserve an escape from that man. I mean he's old and has had four different wives over how many years. I'm afraid if young wives of other houses stop sending their daughters to him, then he might start making babies with his own children.”

Robb pointed out. “Like the Targaryen's did to keep their bloodline supposedly pure.”

“Exactly. I - I want to help then escape from him in some way. I know that there can’t possibly be that many lords wanting to be married to the Freys but it would be a start and create the loyalty between your two houses once again.”

Robb ran a hand over the growing beard on his chin, thinking in deep thoughts. “There’s a few sons of my bannermen who are not wed off just yet. My uncle Edmure of House Tully has no wife either.”

“My brother has borne some bastards but since you’re a King now you can make them into official members of our house. Unless of course you aren’t truly open to this idea at all.”

The young wolf glanced at me, closing most of the distance between us taking my hands in his larger ones. “Whatever you want to do, we shall do to the best of our abilities. So he also has another daughter the age of nine and ten named Rosaline. We could wed her to my uncle.”

“That’s a good start. For the other girls I think we should help find husbands for Merry, Freya, Marianne and then I can take little Shirei under my wing. I was raised by someone who wasn’t my mother and I’m terrified to think of who will talk with her about her bleeding among other things.”

Robb kissed my forehead once cupping my face in his gloved hands. “Your heart is one of the things I love about you.”

“Did you just say you love me?” I drew my head back slightly with a curious look.

Robb smiled down at me longingly. “Yes, I did.”

“Say it again, Stark.”

He nuzzled his nose against mine with a cheeky grin spread across his face when he uttered the words a few more times. “I love you. Do you hear me, I love you. I will always love you, Haelesa.”

“I think I love you too, Robb.” I grinned at him feeling overjoyed at this moment. I knew if I told him now he wouldn’t let Jaime live another night so it was best to keep the secret from him and visit a Maester here before we left. If I don’t know who the father could be after that the Moon Tea was my only option left that I had in my back pocket. “Robb, there’s something you should know along with me loving you. I think I am pregnant with Jaime’s-“

Robb connected my lips with his wrapping one arm around my waist bringing me in as close as possible. Wrapping my arms around his neck I deepened the already heated kiss. He threaded his other hand into my silver locks of hair that cascaded down my back and we would have remained that way if it wasn’t for someone knocking on the closed door peeking their head inside revealing none other than his mother Catelyn. “Robb, Lord Frey is getting tired of waiting for your girl to finish whatever her plan is for his daughters and granddaughters. What would you wish me to tell him?”

“Tell him we’ll be out in a minute to tell him our offer. Thank you, mother.” He glanced over his shoulder responding to her.

She nodded, closing the door when shen left. “Of course.”

“On your lead, my king.” I extended my right hand to him waiting for him in return to which he looped his larger one with my small palm.

“On our lead, my queen. Now and always.”

Together we exited the chamber room making our way into the throne seeing all eyes shift to us regardless of Lord Frey being the one to speak first and break the uncomfortable silence that had surrounded us the second we had left moments ago. “So Lord Stark, what has your lady wife come up with for our two houses to become united once more?”

“Lord Frey, we have come up with a solution. We will choose some of your granddaughters to choose which of my unwed bannermen to try and form a connection with them. But under no circumstances will we force them into an arranged marriage where they aren’t happy.” Robb explained to the elderly lord before our eyes.

Lord Frey eyed his uncle Edmure. “I’ll agree to that on one condition. We shall join house Tully and house Frey through Edmure and my daughter Roslin who was supposed to marry you, young wolf.”

“That can be done, my lord. You have my word.” Robb bowed his head.

Lord Frey clasped his hands together. “Then it’s settled then.”

“We did it. Ahh!” I squealed caught off guard when my husband scooped me up into his muscular arms twirling me around in circles of laughter briefly sitting me back down on my feet.

Robb put one hand on my hip and his other on my stomach grinning ear to ear. “Now all we need is a baby of our own.”

“Actually there’s something I’ve been needing to tell you about. I told you before that I gave my maidenhood to Jaime, that was true but there’s more to it. Robb, I think I’m pregnant except it might not - urgh!” I grunted grabbing at my belly feeling serious pain with a liquid falling down in between my legs.

Robb's face went flushed with fear. “Haelesa?”

“What’s wrong with her, son?” Catelyn came over to where we stood.

Chezney ran over where I grabbed her shoulder for balance until she bent down seeing something staining on the stone floor. “That can’t be too good.”

“Is that blood?” I cried, feeling tears welling in my eyes.

Robb shouted at the people in the room scooping me up into his arms where I winced feeling more pain spreading through my belly. “We need a Maester!” I was rushed into the nearest available room and empty bed with no clue of what was happening to me and my secret baby growing inside of me.

#robb stark fanfic#robb stark fic#robb stark fanfiction#robb stark x oc#robb stark#robb stark x reader#wattpad fanfiction#ask box is open for feedback#comments really appreciated#freya allan#richard madden#game of thrones fic#game of thrones fanfiction#game of thrones masterlist#game of thrones x reader#got fandom#got fic#got fanfiction#house velaryon#house stark#house lannister#jaime lannister x oc#catelyn stark#edmure tully#house frey#walder frey#oc : haelesa velaryon#robb stark fluff#robb stark smut

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

~GENERAL MASTERLIST~

[my works are also avaiable on Ao3: Samiere and on wattpad: _Saelin

Also on fanfiction net: Samiere (just "Born in Flames")]

Fandoms masterlists:

-> Game of Thrones/House of the Dragon

-> Star Wars

-> God of War: Ragnarök

List of boys I can write one-shots with:

—"Game of Thrones"/"House of the Dragon": Robb Stark • Jaime Lannister • Daario Naharis • Arthur Dayne • Daemon Targaryen • Aemond Targaryen • Jacaerys Velaryon

—"Star Wars": Anakin Skywalker • Qimir • Luke Skywalker • Han Solo • Cal Kestis • Din Djarin • Poe Dameron • Kylo Ren

—Other: Corrick [Defy the Night] • Heimdall [God of War: Ragnarök] • Kyle Crane [Dying Light]

#heimdall x reader#gow heimdall#heimdall#god of war heimdall#heimdall god of war#god of war ragnarok#god of war#baldur gow#freya gow#kratos gow#heimdall fanfiction#heimdall smut#daemon targaryen#aemond targaryen#rhaenyra targaryen#alicent hightower#kratos#freya#daemon targaryen x oc#aemond targaryen x oc#house of the dragon#game of thrones#robb stark#robb stark x oc#robb stark deserves more love#robb stark deserve better#robb stark game of thrones#game of thrones robb stark#robb stark smut#luke skywalker

163 notes

·

View notes

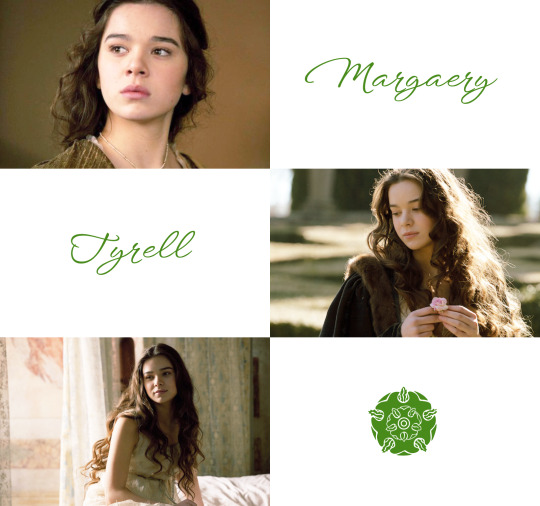

Text

#game of thrones#asoiaf#arya stark#daenerys targaryen#margaery tyrell#myrcella baratheon#sansa stark#meera reed#arya fancast#greta zuccheri montanari#daenerys fancast#freya allan#margaery fancast#hailee steinfeld#myrcella fancast#elle fanning#sansa fancast#dakota blue richards#meera fancast#georgie henley

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

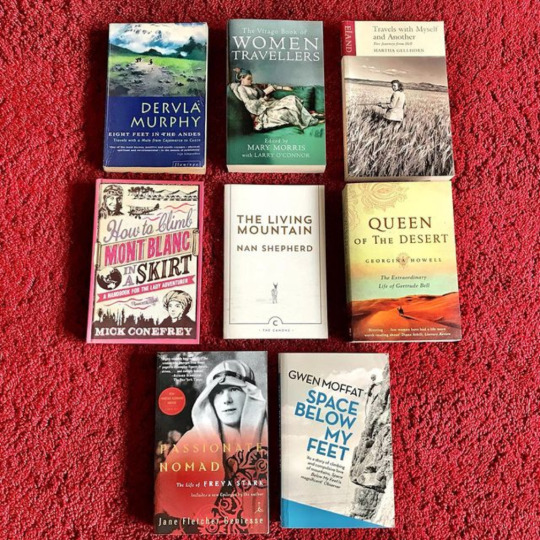

Anonymous asked: I always enjoy posts about women explorers and travel. Can you recommend travel books written by women or about iconic women explorers? I think you would be better qualified than most armchair enthusiasts since you are well traveled, conversant in several languages, and a rugged mountaineer and hiker.

I don’t know about being qualified more than any anyone else. Traveling and exploring isn’t quite the same as hiking or mountaineering of course but I understand your sentiment.

I can say reading about pioneering women explorers and travelers has only inspired me to get off my arse and just go and do it. Perhaps it’s being raised overseas in several cultures and exploring those fabulous countries and regions that has always left with a travel itch to scratch.

Perhaps it’s the Norwegian or the military DNA on my Anglo-Scots side that I have a strong passion for hiking and mountaineering. These days if I do any serious hiking or mountaineering, I tag along with ex-army friends who are incredibly fit and accomplished climbers and hikers.

There are many books and each is a worthy recommendation but here are a few. It’s not an exhaustive list but a good start. I only hope they give you a sense of wanderlust as they continue to inspire me.

Eight Feet in the Andes: Travels with a Mule from Ecuador to Cuzco by Dervla Murphy (1983)

Dervla Murphy’s adventures are mind boggling, and she makes it sound so easy. Even in the mid ‘60s cycling alone through Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan was a bit dodge apart from the fact that there are mountains i.e. uphill cycling. This book is not her most famous one but it’s still worth a read. I put here because it brings memory of my time traveling with my father and elder brother and sister as a 10 year old in the Andes. In 1979 Dervla Murphy and her 9 year old daughter walked with their mule Juana from Cajamarca (northern Peru) to Cusco (far to the south) following as much as possible the Camino Real (the Inca Royal road) along the spine of the second highest mountain range in the world. It took them just over 3 months. Eight Feet in the Andes is a day by day journal of that incredible journey with all its splendour, risks and adventures. The Murphys travel light, most often camping in their small tent and not always sure where their next meal will come from. They endure blizzards, precipitous paths, bogs, heat, theft and find help when most needed and generous (if often taciturn) hospitality.

Reading the book years after I had done a similar trek I realised just how more luxurious our travel was in comparison to Dervla and her daughter who were more rustic in their trekking and hiking. That’s not say we weren’t hiking rough and hard (both my father and eldest brother did their stint in the army as officers) and so I had to keep up. But still, looking back I remember I had a comfortable bed to sleep in and I was well fed. I did have similar experiences of meeting amazing Andean people who are so different from urban Peruvians. The other thing that sticks out in this book is how prescient it is to realise that trekking 15-25 miles per day with the world's most uncomplaining 9-year old in tow would be considered child abuse today. I remember crying, getting blisters, and then toughing it out because I didn’t want to let the side down. So chapeau to Rachel Murphy for being so stoic and brave. As rough as the terrain was for them, there is undoubted warmth and humour in this book.

The Virago Book of Women Travellers, edited Mary Morris & Larry O’Connor (1994)

The Virago Book of Women Travellers captures 300 years of wanderlust. Some of the women are observers of the world in which they wander and others are more active. Often they are storytellers, weaving tales about the people they encounter. Whether it is curiosity about the world or escape from personal tragedy, these women approached their journeys with wit, intelligence, compassion and empathy for the lives of others. Because it’s a collection of women and their wanderlust, it’s not the kind of book you can read cover to cover or even in one sitting. It’s a good book to dip into as the mood pleases. As such it serves as a good introduction to how varied the experiences of women travellers and writers has been. I didn’t feel guilty about skipping certain parts because I found the writing turgid and boring, but that is the nature of an anthology, some you like and others less so.

In the introduction to this anthology, Mary Morris writes that “women’s literature from Austen to Woolf is by and large a literature about waiting, usually for love”. The writers selected here are the ones who didn’t wait: they set out, by boat or bicycle, camel or dugout canoe, and sought their own adventures. The collection covers some 300 years of travel writing, beginning with the extraordinary Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), who had just - scandalously - made the journey from London to Constantinople alone, and finishing with the American writer Leila Philip, an apprentice potter in early 1980s Japan, learning the art of harvesting rice by hand with a sickle. The range, in terms of location, style and mood, is vast.

So we meet independent travellers and those on the road with family, women on long epic journeys or more focussed trips, famous names and obscure, mountaineers and motorcyclists, aviators and anthropologists, those treading well-kept routes and brave pioneers, young women and old, but all intelligent and good writers. Many of the women were traveling alone during times when traveling wasn't very easy and certainly wasn't something many women did on their own, and they were traveling to places all over the world. The majority of the essays are about Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Many of the women travellers are familiar such as Dervla Murphy, Rebecca West, Beryl Markham - and the other usual suspects.

There were a few about traveling to colonial America and one about traveling to the wilds of Ohio written by Anthony Trollope's mother that was hilarious. An extract from Frances Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) demonstrates a satirical eye her son clearly inherited: “She lived but a short distance from us, and I am sure intended to be a very good neighbour; but her violent intimacy made me dread to pass her door”. Some other pieces are les scathing and more lyrical: M. F. K. Fisher brings Dijon to life through the battling scents of the city’s famous mustard, gingerbread and the fragrant altar smoke billowing from a church door; Vita Sackville-West conjures the fading light of a picturesque Persian garden at dusk.

Many of the women faced sexism along the way and had to fight to go certain places and some even face sexual harassment on their travels. But mercifully these experiences are few and far between. There were a few many wonderful writers I stumbled across of whom I’d never heard – such as Flora Tristan, Frances Trollope, Isabelle Eberhardt (whose packed and tragically short life is worth reading up on), and many others. Maud Parrish writes exhilaratingly about adventures in Yukon and Alaska, the intriguing Mrs F D Bridges (about whom we know little as she travelled in the shadow of her husband) describes nineteenth century Mormonism compellingly. Emily Hahn, I did know about as her writings I was familiar with when I was growing up in Shanghai. Hahn writes vividly about her opium addiction in China (one of a few women to focus heavily on addictions).

However uneven anthologies can be, they still can serve as a good starting place to discover further a favourite writer and traveler. And if it can do that then an anthology will have served its purpose.

Travels With Myself and Another: Five Journeys from Hell by Martha Gellhorn (1978)

Although Martha Gellhorn was principally a war correspondent but seems to have travelled widely for most of her life. Her book was originally subtitled Five Journeys from Hell, which provides a not very subtle clue about her travel experiences. It describes her journeys in China with the unnamed other (1941), the Caribbean (1942), Africa (1962), Russia (1972) and Israel (1971). She says that this is not a proper travel book – ‘I rarely read travel books myself. I prefer to travel’. And it’s clear that she spent most of her life travelling, with an impressive list of places she has visited. It’s a difficult book to categorise, and that’s perhaps also true of its author. She clearly had a strong spirit of adventure, and as someone who covered every major conflict from the Spanish Civil War to the American invasion of Panama in 1989, she cannot have lacked courage or determination.

The writing is excellent, with lots of very funny, self-deprecating, black humour, and witty observations about the pitfalls of travelling generally. Many things infuriated Gellhorn - injustice, cruelty, stupidity - but on a personal level, nothing made her more incensed than having her name linked with that of the man she was married for less than five of her almost ninety years, Ernest Hemingway. Although Travels with Myself and Another is subtitled as a memoir, the most famous of her three husbands appears in just one essay under the initials of U.C. (Unwilling Companion), probably only because he provides extensive comic relief for a writer “who cherishes...disasters” and is immensely fond of black humour.

The only trouble is that her accounts of her journeys focus largely on her feelings of boredom, fear, exhaustion, hunger, anger and so on, with rare uplifting moments between. She also seems to have little fellow feeling for the people she comes across, and there are flashes of racism and intolerance. As her companion in China says, ‘Martha loves humanity but can’t stand people’. Still Gellhorn relishes mishaps in her journeys because that is where the story lies--and since her journeys are invariably far off the map, mishaps are always there, waiting for her acerbic descriptions.

Of all the travels that she has chosen to relive, her journey to China in 1941 is easily the most hair-raising and hysterically funny. As someone who grew up in Shanghai as a girl, China in 1941 is still firmly etched into Chinese history and culture. The legacy of the Japanese war - the sheer brutality of it which many Europeans have blithely ignored - remains a ghost in the collective memory of the Chinese and is a regular staple as a setting for its many television soap operas.

Anyway, in this book, Gellhorn is determined to witness the Sino-Japanese War first-hand shortly after Japan joins Italy and Germany in the Axis. “All I had to do is get to China,” she says blithely, and as part of her preparations for this odyssey she persuades U.C. (Ernest Hemingway) to go with her. Embarking from San Francisco to Honolulu by ship, a voyage that “lasted roughly forever,” Gellhorn and U.C. then fly from Hawaii to Hong Kong, “all day in roomy comfort”, landing at an island where passengers spend the night before arriving in Hong Kong. “Air travel,” she says, “was not always disgusting.”

As a war correspondent for Collier’s, Gellhorn insists upon getting as close to the war as she can. Traveling by plane, truck, boat, and “awful little horses”, she and U.C. find the troops of the Chinese Army and their hard-drinking generals (who almost vanquish U.C. in their alcoholic prowess), Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang (“who,” Gellhorn fumes, “ was charming to U.C. and civil to me”), and, through a cloak-and-dagger encounter in a Chungking market, Chou Enlai (“this entrancing man,” Gellhorn confesses, “the one really good man we’d met in China”). Although she and U.C. barely escape cholera, hypothermia, food poisoning, and the hazards of drinking snake wine, by the end of their journey Gellhorn contracts a vicious case of “China Rot,” an ailment resembling athlete’s foot that’s highly contagious. U.C.’s commiseration is heartwarming: “Honest to God, M., you brought this on yourself. I told you not to wash.”

On their last night, hot and steaming in the humidity of Rangoon, Gellhorn is overwhelmed with gratitude that U.C. has stuck with her through “a season in hell.” She reaches out, touches his shoulder, and murmurs her thanks, “while he wrenched away, shouting “Take your filthy dirty hands off me!” “We looked at each other, laughing in our separate pools of sweat.” “The real life of the East is agony to watch and horror to share,” Gellhorn wrote somewhat melodramatically to her mother. Years later, she concludes “I was right about one thing; in the Orient a world ended.” From Gellhorn’s sharp-eyed and sharp-tongued point of view, that ending was nothing to mourn. Gellhorn is captivating, bold, reckless, romantic, and deeply, powerfully, and hypnotically inspired to help the world despite her own personal flaws.

How to Climb Mont Blanc in a Skirt: A Handbook for the Lady Adventurer by Mick Conefrey (2011)

I had second thoughts about including this book but it is easily the most readable and therefore the most accessible introduction to women explorers and travellers….and yet it’s written by a man. Hmmm. Bear with me. I was given this book as a birthday gift and dutifully I read it and even I was surprised that there were some women explorers I hadn’t known about in amongst the usual suspects of Freya Stark, Gertrude Bell and Jeanne de Clisson. The book overviews female explorers and adventurers from the 1800’s through the 2000’s. It is a collection of short anecdotes, ranging between one paragraph and three pages in length.

There aren’t traditional chapters, but the book is sectioned off by different questions. The arrangement of the book makes reading straightforward and simple. I suppose there is no correct answer to questions like “why do women adventure?” and “how do women adventure differently to men?”. Conefrey is visibly careful not to generalise. However, he does compare them a lot. Some women appear only in tandem with their husbands, some feel like an offshoot of their husband and there’s an entire chapter comparing women adventurers to either their male expedition partner or the man who did the most similar expedition or adventure, usually before the woman did it. I did find myself wondering if we needed quite so many men in a book that’s supposed to be exclusively about women.

The majority of the women who appear were doing their adventures a couple of centuries ago, when vast swathes of the world were mysterious and unknown, when it was acceptable to hire or occasionally coerce fifty locals to carry your luggage or occasionally to carry you in a bath chair, when people routinely carried an entire arsenal with them, and yes, when women were doing this kind of adventuring in all sorts of skirts.

These are not then full biographies. Some names appear again and again. Freya Stark, Gertrude Bell, Mary Kingsley as well as other ones like Rosita Forbes, Mary Hall, Ella Maillart, Annie Smith Peck, and Jeanne de Clisson. Clearly bigger stories to tell about them. They went off to places women just didn’t go to in those days and did things women just didn’t do. But the book does serve as a jumping board to explore further any explorer that captures your attention. In the end it’s something to read on an idle rainy day and can be read in bedtime-reading sized chunks. Rather than a deep trek, it’s the equivalent of a well written jog through a brief explanation of the journeys and personalities of some rather interesting women.

The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland by Nan Shepherd (1977)

If you’re Scottish then you have no excuse not knowing who Nan Shepherd was - her face has been on the Scottish five pound note. As strange as it sounds, being Anglo-Scots on my father’s side, I first heard her name when living on the other side of the world. Only when I came home to see my family clan we would walk in the Cairngorms and her spirit would be invoked with reverence and awe. For a long time in Scottish arts and letters she was known only as a minor writer of the early 20th century Scottish Renaissance. Between 1928 and 1935 she published three modernist novels – The Quarry Wood being superlative - and one book of poetry. From then until her death in 1981, she published only one more, The Living Mountain. It was written during the latter years of the World War Two but, following advice of novelist Neil Gunn, left in a drawer. No publisher would take a punt on such an unusual book, he argued. In 1977, it was unearthed and Aberdeen University Press published it. This prose-poem about the Cairngorms quickly became a cult classic among wanderers and mountaineers, as important as anything written by WH Murray.

In this masterpiece of nature writing, Nan Shepherd describes her journeys into the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland. There she encounters a world that can be breathtakingly beautiful at times and shockingly harsh at others. Her intense, poetic prose explores and records the rocks, rivers, creatures and hidden aspects of this remarkable landscape. Reading it has become a rite of passage for anyone wishing to understand the Scottish mountains, the literary equivalent of a hillwalker spending the night under the Shelter Stone at the head of Loch Avon. Both pursuits are likely to keep you up all night. From its first sentence, "Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge”. The Living Mountain draws you in with the feyness of its vision, the lucidity of its prose and Shepherd’s refreshing philosophy that mountains are more than peaks to be scaled. In writing the book, her aim was to uncover the "essential nature" of the mountains, and understand her place in them.

Nature writing these days is as much about the person as the place. Refreshingly, Shepherd is not there as a personality, rather a human presence in the landscape, complete with roving eye and senses wide open. She understood nature’s ultimate indifference (it doesn’t care who you are), yet also how much she was a part of it. She had a keen sense of ecology, an understanding that to "deeply" know a place was to know something of the whole world. Her chapters, for example, move through every element of the mountains, from water to earth, on to golden eagles and down to the tiniest mountain flowers, like the genista or birdsfoot trefoil. Robert McFarlane, one of my favourite writers today, has argued that is why she is a truly universal writer.

Nan Shepherd spent a lifetime in search of the ‘essential nature’ of the Cairngorms; her quest led her to write this classic meditation on the magnificence of mountains, and on our imaginative relationship with the wild world around us. It is a very short book at around 100 pages but it can feel like a thousand when you immerse yourself in the beauty of her prose and wisdom. Bonus tip: the edition with has Robert Macfarlane’s introduction and an afterword written by Jeanette Winterson. What I love about this book is that you don’t have to travel to exotic far flung places to appreciate mountains or nature in general. For most of us it can be in easy reach from our door steps.

Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations by Georgina Howell (2007)

If you follow my blog then you know I have made a lot of posts about one of my heroines, Gertrude Bell. I’m not going to rehash all that I’ve posted here. Just type in ‘gertrude bell’ into the search box.

Gertrude Bell is commonly referred to as ‘the female Lawrence of Arabia’ and that really explains in a nutshell how she’s been screwed over by history. If we could be more fair minded and reasonable, T.E. Lawrence would be called ‘the male Gertrude Bell’ and Gertrude would have the four-hour Oscar award-winning biopic that everyone would watch at Christmas time. But always no, and because of this, T.E. Lawrence is a household name and Gertrude Bell is a footnote in his story. To this day it ticks me off that Gertrude Bell gets no mention in David Lean’s magisterial Lawrence of Arabia. It’s one of my favourite films of all time but it grates that she didn’t even feature in one scene.

Suffice it to say, Gertrude Bell was one of those rare figures for whom the expression “larger than life” is too small. In an age when women were expected to stay close to husband and hearth, she explored uncharted deserts and ascended previously unclimbed mountains…in Edwardian skirts. Bell was full of firsts. She began marching to a different drummer at Oxford University, which was scarcely comfortable with women in the 1880s. A professor asked Bell and the few other female students for their reaction to his lecture. “Green eyes flashing, Gertrude retorted loudly: `I don’t think we learned anything new today. I don’t think you added anything to what you wrote in your book,'” Howell says. She was the first woman to get a First in modern history at Oxford.

As a highly respected archaeologist, she made important archaeological discoveries in an era when the methodology involved bribing local nabobs and packing a gun lest the natives not be friendly. A linguistic polymath, she translated the love lyrics of medieval Persian poet Hafiz. She was friends and colleague of T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). She was every inch - and more - her colleague and friend’s equal in intellect and action. Bell was to achieve seniority in the British military intelligence and diplomatic service. The in-depth knowledge and contacts she acquired through long and arduous travels in then Greater Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and Arabia, shaped British imperial policy-making. More successful than Lawrence, she shaped the making of the modern east after the First World War. Indeed she ran Iraq when Britain, which won World War I, cobbled together that country out of bits and pieces of the Turkish Empire, which lost the war.

A daughter of the English industrial class, she fell in love with the parched landscapes of the Middle East and went native, albeit loading her caravans with fine china and formal gowns. She so mastered the language and culture of the Bedouins that members of the Beni Sakhr, a tribe not well-disposed toward outsiders, saluted her as one of their own. “`Mashallah! Bint Arab,’ they declared - `As God has willed it: a daughter of the desert,'” Georgina Howell writes in Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations.

I could easily point you to her own book, ‘Letters of Gertrude Bell’ which are cherished part of my library. But that might not be the best entry point into the extraordinary life of Gertrude Bell. To date Georgina Howell has probably done the best biography of this amazing woman - Janet Wallach’s Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell is another one but Howell’s is better. Bell was constantly writing letters about her adventures, and Howell quotes them extensively throughout the book - which makes Bell much more dynamic. The scope of Howell’s book is also wider - while Wallach’s book focused mainly on Bell’s work in the Middle East later in her life, Howell seems to be trying to give equal attention to all the phases of Bell’s life

So my reservations about Howell’s book should be taken with a pinch of salt. Howell’s book certainly delves into the primary sources more head on. It’s a good book but the pity is that Howell’s literary skills are not always up to those of her subject. Yet such was likely to be the case no matter who her biographer might have been.

Howell doesn’t help herself by fretting about marginal issues like why Bell wasn’t more of a feminist. Honorary secretary of the Anti-Suffrage League, Bell organised a massive petition drive, which netted 250,000 signatures, against giving women the vote. Since Bell set so many firsts for her sex, why shouldn’t she also have been the Emily Pankhurst of her era?

Early on, Howell’s narrative gets bogged down in a recitation of Bell’s ancestors and social-set contemporaries. Many have hyphenated names bound to be lost on readers without ears trained since childhood for such aristocratic nuances. The great love of her life was Maj. Charles Hotham Montagu Doughty-Wylie of the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Friends called him Dick. When they met, he was married and she was a virgin,“For Gertrude, intrepid as she was, sex was the final frontier,” Howell writes. In her mid-40s, Bell couldn’t bring herself to cross that border with her beloved, though furtive attempts were made. He went off to serve and die in Britain’s ill-fated Gallipoli campaign, carrying only a walking stick into battle against Turkish gunners. Howell also doesn’t really address why Bell would want to take her own life. Also missing from the Howell biography is Bell’s early disdainful attitude for the Middle Eastern locals she encounters.

Overall Howell’s obvious fondness for her subject hampers her ability to construct a more objective and nuanced portrait of Gertrude Bell. Readers are, however, indebted to Howell for her decision to allow Bell to speak for herself by including quotations from many of Bell’s letters. Summing up the state of Iraqi affairs in spring 1920, Bell admits that events on the ground have overwhelmed British intentions. “We are now in the middle of a full-blown Jihad . . . Which means that it’s no longer a question of reason . . . The credit of European civilization is gone . . . How can we, who have managed our own affairs so badly, claim to teach others to manage theirs better?"

Passionate Nomad: The Life of Freya Stark by Jane Fletcher Geniesse (1999)

Like Gertrude Bell, I’ve posted a lot on Freya Stark (1893-1993). Again, one can search my blog for her posts. It has to be said that Freya Stark, much like Gertrude Bell, was not the most cuddliest women one could warm to. Both could be demanding and dominant with others by having an iron will determination that their way was best. And both were friendless with other women whilst also having the most tragic luck in their romantic lives. Needless to say both were fascinatingly complex and complicated women of renown. Ex-New York Times writer, Jean Fletcher Geniesse, makes a fine stab at giving us a biography worthy of Stark’s amazing life, warts and all. Her book is excellent and offers a psychologically astute chronicle of the adventurous life of this intrepid traveler of the Middle East.

Freya Stark lived a truly remarkable life. Born in Paris to an English father and an Italian mother of Polish/German descent, she was raised in Italy, chafing under the impositions of her vain, rather selfish mother who had left her husband to his bourgeois English life. Freya was largely self-taught, learning Arabic and Persian for fun, always fascinated by the Orient. Which was just as well as she had a miserable family life. her overbearing mother had left Freya’s father for an Italian count, who would later marry Freya’s sister. Geniesse describes this suffocating domestic atmosphere in vivid detail, arguing that it helped trigger Stark’s desire for a life of picturesque adventure.

At age 13, Stark was disfigured in a horrible industrial factory accident. Stark began studying Arabic in London and in her mid-30s. By 1927 she was on a ship bound for Lebanon. Stark immediately fell in love with the Middle East, becoming “fascinated by the ancient hatreds among” the region’s different tribes and religious sects. As an Arabist proud of her British heritage, Stark was in the difficult position of justifying British colonialism to the freedom-loving natives. During WWII, she worked for Britain’s Ministry of Information in the role of propagandist. She collaborated with native groups in Egypt and Iraq, drumming up support for the Allied powers. She quickly found she was very good at her double vocation, as intrepid explorer and eloquent letter-writer, then pursued and built on these skills through two glorious decades, achieving stellar literary fame, and moved effortlessly in the company of the high and mighty.

Stark would travel on foot, by donkey or camel into some of the most inaccessible regions of the Middle East, places that scarcely saw Westerners, let alone single Western women. She would infiltrate mosques and harems, climb mountains, uncover ruined cities, live amongst the simple people of the deserts, sleeping under the stars or in Bedouin tents. When Freya traveled, she liked to stay where the local people stayed, and ate their food, drank their water, and talked to them. She learned many different languages and dialects throughout her travels.

She was a mountain climber, scaling the Matterhorn, and other peaks. Since she didn’t take any precautions with food or water, she was constantly ill, and she survived many different diseases: typhoid, dysentery, and malaria, to name a few. Contrary to what many might think she wasn’t the best organised of travellers. She would often plan haphazardly and rely on her skill and luck to be at the place she wanted to be.

She wrote numerous travel books, becoming one of the foremost experts on Islamic history and peoples. Her early books on Yemen and the ancient cult of the Assassins won her plaudits from the public and the Royal Geographic Society. Indeed the published accounts of her travels quickly became the most popular reads of the day, not only for the thrilling adventures she undertook but also for her incredible writing. Freya Stark kept meticulous notes about her travels and the lands she explored, and these were instrumental in updating the maps used by the Royal Geographic Society and the British Government. Freya was also plagued by the same concerns as her contemporary, Gertrude Bell, and wrestled with contradictory feelings as a proud British citizen regarding the government’s policies toward a region she admired and even loved.

Despite her growing fame, her personal life remained unfulfilling. She fell in love with a British colonial officer who “brusquely rejected” her. After the war, at the age of 54, she married a minor colonial official who, after their wedding, revealed he was a homosexual (or rather, she could no longer pretend not to see it). Because of her factory accident as a child, she had a desire for love and to be beautiful, which lead to intense jealousy of younger and prettier women.

It’s a captivating book about one of the great English-language interpreters of the Middle East, and one in which draws on the huge and expressive bulk of Freya Stark's letters to paint a personal and professional portrait of rare accomplishment. This biography is no hagiography, exposing Freya warts and all - her bravery, independence, sense of adventure and fun is all laid out alongside her tendency to imperiousness, her habit of using people who could be helpful to her, her neediness and desperate longing to be loved. Geniesse successfully explores Stark’s fascinating psychological makeup, her mixture of insecurity and total fearlessness. Throughout, the author skilfully details the people, places, and ideas that shaped her subject’s life. Although Stark could be amazingly kind to Iraqi Bedouins or Druze tribesmen, she took the smallest slights to her dignity as personal affronts.

Freya Stark comes across as a fascinating person, a woman who never let convention stand in the way of what she wanted, a true traveller keenly interested in everyone she came across, but somehow a woman who, whilst comfortable in any kind of surrounding, was never truly comfortable in herself. In all, the evocation of a world only sixty years back but so removed from ours in its rhythms and its concerns - with the intense letter writing, the extended visits to country houses, and the imperatives of empire - will keep the attention of the reader.

Overall it’s worthwhile, stylish, and thoroughly researched biography of a fascinatingly complex, often exasperating woman. Dame Freya Stark started traveling at the age of 22 and didn't quit until she was in her 90s - perhaps no finer example of wanderlust.

Space Below My Feet by Gwen Moffat (1961)

Gwen Moffat is little known amongst the general population but to the wider mountaineering community she has a rightful place as one of Britain’s foremost female climber in the post-war world. She has the distinction of being Britain’s first female professional mountain guide and also a prolific writer of over 30 books. This entertaining memoir roughly covers the years 1945-1955, when Gwen was in her twenties. Gwen Moffat is unorthodox, uncompromising, honest, charming, and a born rebel. Moffat was an Army driver in the Auxiliary Territorial Service, stationed in North Wales after the end of the Second World War, when she met a climber who introduced her to climbing in the Welsh Hills and a bohemian lifestyle. As a conscientious objector she found the army was not her cup of tea. She especially found army life too stiff and constraining the more she climbed around Wales, where she was stationed.

From that moment her entire life unfolds against a background of mountains, and she takes us with her. We follow Gwen in her hobo existence in a shack in Cornwall, in cottages in Wales and Scotland, on a fishing boat or when the money ran out, she worked as a forester, went winkle-picking on the Isle of Skye, acted as the helmsman of a schooner, and did a stint as an artist's model. To keep alive and support her little daughter in the meantime she has followed a number of other trades, all with a mountain background except for a job in a theatre: running a Youth Hostel in Wales, driving a travelling store on lonely roads in the Scottish Highlands, acting as a maid of all work in a hotel in the British Lakes.

There is no deeper truth for Gwen, just a frugal, bohemian life singularly devoted to climbing crags and mountains. Most of the action is situated in Wales and Scotland and it helps to have a rough idea of the topography as the narrative is littered with exotic toponyms referring to the innumerable cliffs, buttresses and arêtes climbed by Moffat. A few chapters deal with her climbing adventures in the Alps (Chamonix, Zermatt, Dolomites).

She is a skilled writer as she is a climber. Anyone reading her will experience a novice’s thrills during her first climbs, bare-footed, on the Welsh slabs; we go through hairbreadth escapes, and the climbing goes on: difficult, severe, very severe. When we finally part from her and her husband on the summit of the Breithorn after 12 hours on the Younggrat, she is a fully qualified guide. From time to time we are taken for exciting adventures on the Continent, to Chamonix, Zermatt and the Dolomites. To this reader however, the most fascinating parts of the book are the descriptions of the mountains Gwen Moffat knows best, the Welsh and Scottish Hills, and the enchanting island of Skye. People of all sorts come and go in the pages, but they are secondary to the main theme of a human being and her endeavours in high places.

The great attraction of Space below my Feet is the writer’s power to conjure up mountain scenes, moods and weather and her own reactions to them. This is an intensely personal book and may be frowned on by those who like their mountains to be viewed objectively. Mountains are her passion: through them she found freedom and her true self, and she feels she can best express herself climbing among them. The objective mountain worshipper is often personally inarticulate; he or she dwindles into insignificance beside the beloved object and is rather guilt-stricken about obtruding their own feelings in descriptions of climbs. Gwen Moffat though can articulate the unspoken onto the page. It’s her searing honesty and vividness as a writer that makes this book well worth reading.

Thanks for your question

#ask#question#explorers#exploration#travel#travellers#women#femme#nan shepherd#martha gellhorn#gertrude bell#freya stark#gwen moffat#dervla murphy#books#reading#wanderlust#mountaineering#hiking#trekking#personal

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

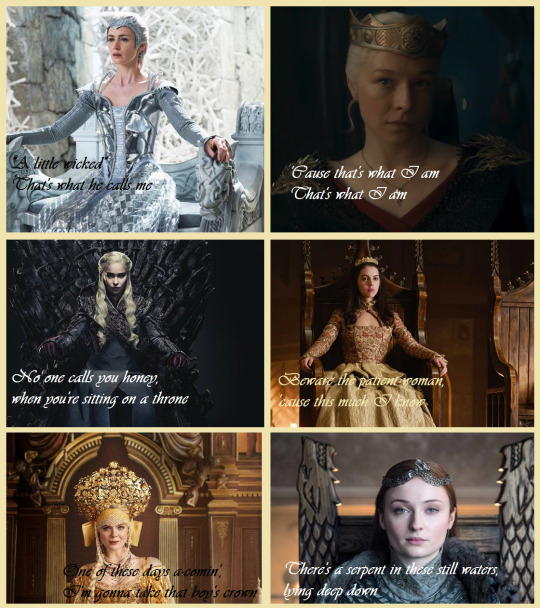

Remember, it doesn't matter what those scared boys with no self-confidence say. You have the right to be Queen. You have the right to be strong and independent. You have the right to look for a man who will be your knight, not your executioner.

"A little wicked"

That's what he calls me

'Cause that's what I am

That's what I am

No one calls you honey, when you're sitting on a throne

No one calls you honey, when you're sitting on a throne

Beware the patient woman, 'cause this much I know

No one calls you honey, when you're sitting on a throne

One of these days a-comin', I'm gonna take that boy's crown

There's a serpent in these still waters, lying deep down

To that king I will bow, at least for now

One of these days a-comin', I'm gonna take that boy's crown

#queens#girls power#strong women#the huntsman#queen freya#the game of thrones#queen daenerys#sansa stark#queen of north#house of the dragon#rhaenyra targaryen#the great#queen catherine#reign#mary stuart#fuck#traditional gender roles#male leadership#fucking#obeyhim#submissivewife

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, here’s the thing…we all LOVE Ser Harwin Strong. But, Ryan Corr would have been amazing as Cregan Stark. He looks like a Stark. And the voice. His. Voice.

I made a post about this earlier today!🤣 so I wholeheartedly agree!

14 notes

·

View notes