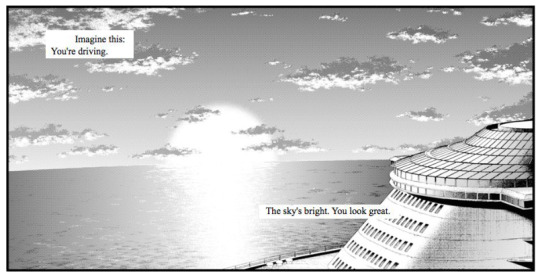

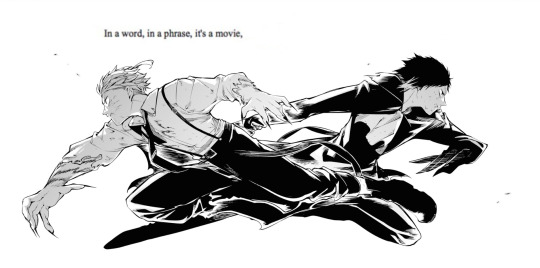

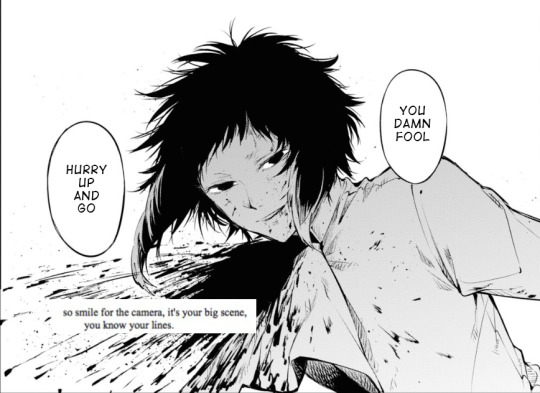

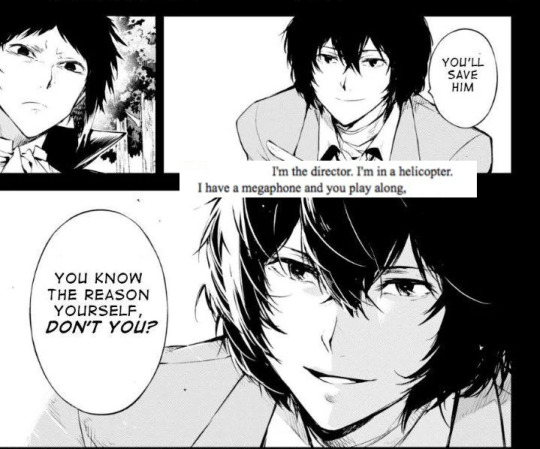

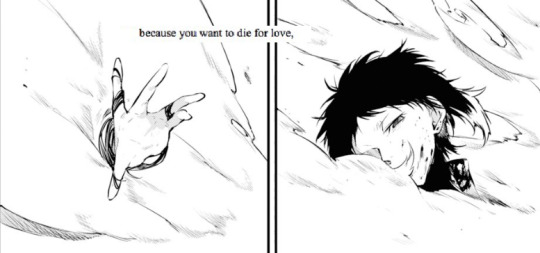

#however the very interesting contrast between “accepting he's going to die for REVENGE for his lost friends”

Text

planet of love

#bsd#bungo stray dogs#akutagawa ryuunosuke#ryuunosuke akutagawa#shin soukoku#sskk#uhmm excuse the fact that the quality on the word fragments is a little bit shit if you look too close#i didn't wanna type it out so i just cropped the lines out of a pic of the poem but obviously that kind of zooming in#doesn't preserve a clean image. i think it looks mostly fine but it could be better#anyway. had a hashtag Thought. do you guys get me#smth smth how we only really see aku express the fact that he cares via being willing to die for people#however the very interesting contrast between “accepting he's going to die for REVENGE for his lost friends”#vs. you know. dying for atsushi to PROTECT him. no vengeance. atsushi is ALIVE and aku dies TO KEEP HIM ALIVE. idk#the difference between protection and vengeance but both times it's love expressed as the intention to die IDK IDK IDKKKKK#DO Y'ALL GET ME#oh btw poem used is planet of love by richard siken. i think we here all on the sad gays website know that already but just in case

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

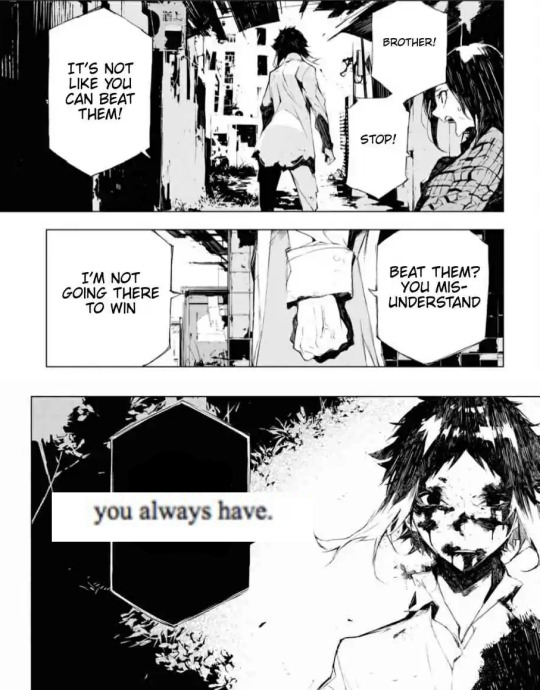

Why is shinobu such a great character? I love her, shes my favorite pillar.

I think the single best thing about Shinobu’s character is that she’s a bitch. Wait, wait, no get back here I’m going to explain myself. I think what makes Shinobu great is that she’s THAT BITCH.

There’s a pressure for characters, especially female characters to be written with no real substantial flaws. At best they have job interview flaws, they are clumsy, oblivious, or they’re just too giving towards people. They’re too empathic. They’re too nice and they let people walk all over them, but to no real consequences.

Often characters are written to be likable, rather than to be complex and flawed. They’re written in a way that they will be likably received by an audience. Which is why the rough edges of them tend to get sanded down. I think this is a problem for both male and female characters by the way, that characters are reduced to bland characterizations as opposed to complex ones.

It’s like the difference between Uraraka and Himiko in MHA, a shonen manga that runs within the same magazine. Himiko as a character is far more developed because she is allowed to have flaws and get in the middle of bloody confrontations. Uraraka is a character who could be interesting: a hero motivated by personal greed, a child who feels that they burden they’re parents, someone perceptive and empathic but who always keeps her mouth shut for fear of tripping on other people’s feelings. She has complex flaws, but priority is given on making Uraraka look like a nice girl. Himiko isn’t nice, but she gets to like... do things.

Shinobu has flaws, and she holds onto the ugliest parts of herself, her anger, her desire for violent revenge, and refuses to improve as a person and ultimately dies to those flaws and that’s what makes her so unique and interesting. I’ll go over those underneath the cut.

1. Medicine and Poison

Shinobu’s entire character is written around this dual meaning: basically, medicine is something that both heals and hurts. Most people think of medicine as something that is comforting and nurturing, but too much medicine can become a poison that destroys the body instead. Often many drugs we use for medication are toxic in excessive amounts.

Shinobu is a character who toes the lie between a healer, which is how everyone expects her to act, and a poisoner which is what Shinobu regards herself as. She is someone capable of both. She can heal and nurture others, she can also destroy them with horrible poison. However, her arc in the story shows more and more that she chooses to poison and destroy because she doesn’t see herself as someone capable of healing.

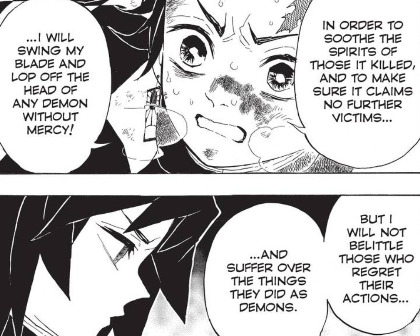

Demons were once human. They are still capable of human feelings. They all have human desires and fell into demonhood for very human reasons.

Tanjiro is someone who ultimately rejects the actions of Demons, but also sympathizes with their humanity. He doesn’t want to kill. He acknowledges that he has to due to circumstances, but no matter what he cannot stop seeing the humanity inside of the demons he is fighting against. Tanjiro is a merciful killer.

Shinobu is introduced right after we see Tanjiro introduced to the idea that demons have feelings and motivations and grapples with that and his own empathy. Shinobu is presented to us as a character without any empathy for demons. She is a merciless killer.

Shinobu wants to repay cruelty with cruelty. She relishes in the chance. She likse feeling more powerful than the demons that victimized her. Tanjiro and Shinobu’s methods of dealing with demons are deliberately contrasted to show how different they are. Shinobu doesn’t see demons as humans, just as things, that need to be punished. She’s not wrong for thinking that demons need to be stopped and killed in order to prevent them from hurting innocent people, but torture is bad yo.

It’s even shown that Tanjiro is much more willing to accept demons who genuinely are repetant for what they did in the past like Tamayo. Whereas, Shinobu does work with Tamayo she mistrusts her and resents her the entire time. Shinobu’s view of the world is black and white, where she is the personal judge, jury and executioner of demons. Yes, that’s how most of the demon slayer pillars are introduced to us, but it’s especially drawn attention to in Shinobu’s case with her introduction, and her comparisons to Tanjiro.

Basically Tanjiro’s stance is I’m not going to belittle those who regret their actions, and see the humanity in demons. Shinobu’s response is I’m going to belittle the HELL out of them.

Shinobu mocks, teases and belittles because she’s someone incapable of being sincere. The main difference between Shinobu and Tanjiro, is that Shinobu’s sister is dead, and Tanjiro isn’t. Tanjiro still sees himself as fighting to protect someone whereas Shinobu only lives to pay back the damage that’s been done on the world.

Shinobu serves a dual role in the series. She’s the one who nurtures and heals everyone on the butterfly estate. She’s also the most remorseless killer of demons who physically enjoys the slaughter. She is medicine, but she is also poison.

Shinobu’s anger is a very poisonous part of her personality, but rather than deal with it, and attempt to be better she’d much rather put on a fake smile and let the poison flow. We’re given a reason why. Ever since her sister died Shinobu felt like everything that’s good about her died with her sister, and now she’s indulging in the worst of herself.

If Tanjiro is someone who fights out of their love for other people, then Shinobu is someone who fights out of hatred. She hangs onto that hatred because she feels like that’s the only real part of herself and she can’t be good like her sister.

There’s a reason that Shinobu is paralleled to Doma and it’s because everything that’s positive about her, her gentle nature, her smiling, her empathy is completely faked. It’s an act that she puts on to be more like her sister while holding her resentments deep in her heart. She could be medicine or poison, and chooses to be poison.

Shinobu could have chosen the path of healing or forgiveness, but she didn’t want to. She chose to die, angry and fighting instead. Her last action is tantamount to suicide. She chooses to die poisoning another, rather than try to live healing herself because she thinks she is incapable of living without her loved ones in her life. It’s not a happy ending, but it’s a powerful writing choice. The choice not to forgive. The choice to stay angry. Shinobu is a character written with powerful emotions behind her, hiding just underneath the surface which is all fake smiles and friendly pleasantries, and that’s what makes her a compelling character.

#Anonymous#metasks#kocho shinobu#shinobu kouchou#kny meta#kimetsu no yaiba#kimetsu no yaiba character analysis#kimetsu no yaiba theory#shinobu meta

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

hot take on the recent chapters

I came up with this while I was on too little sleep & after a friend caught up to the manga, it’s really long and I hope it makes sense - so, enjoy!

I think what is happening right now, might be Ymir trying to re-establish her former form.

Because Eren has three out of nine titans right now - Attack, Founding, Warhammer. The Founding Titan was the very first of all titans before Ymir started gathering/creating all those other abilities.

We currently have this written/known about it specifically on the official wiki page:

Its Scream can create and control other Titans, and modify the memories and body compositions of the Subjects of Ymir, but this power can only be used by the royal family under normal circumstances.

According to Marley's Titan Biology Research Society, the Founding Titan is the point where the paths that connect all Subjects of Ymir and Titans cross.

We have been known that only the royal family can properly use it, which is why Eren only managed to use the Founding when touching Dina Fritz's titan (the one that ate his mother) to protect Mikasa after Hannes was devoured and then when coming in contact with Zeke, seeing as he is from royal blood as well. However, the royal family is bound by a vow and the ideology of Karl Fritz - basically, he wanted the Eldians to be locked up and separated from the world because they had been too involved in wars before. So he wanted to protect them, essentially.

The vow is renouncing war to stop Eldia from using the Founding Titan to devastate the world ever again and it possesses the individual to follow the idea. That is why Frieda, even though she viewed the Eldians as sinners, still followed that protocol.

Now, with Grisha devouring Frieda and gaining the Founding Titan and passing it on to Eren, the chain of royal blood inheritors was broken. Which is why, paired with Erens own ideology to go behind the walls and see the world, Ymir zeroed her interest in him as it's seen in the recent chapters.

She herself wasn't of royal blood and being used to fight wars for that king in the backstory most likely built a hatred for humanity in her view - she was viewed as that slave, of which Eren broke her free. He's the only inheritor that hasn't been shaped and controlled by that ideology of King Fritz that she could get her hands on, so she can twist his views or add her own to it in having to destroy the world and humanity in it.

I think that she's using Eren as a vessel to collect all titans. He already has three, and with every other shifter present right now - Armin (colossal), Reiner (armored), Annie (female), Falco (jaw), Pieck (cart) and Zeke (Beast) - she can take them prisoner and force them to join with Eren.

She basically already has Zeke in her control, having lured him into paths with Eren, and she just took Armin prisoner with another previous titan. Why else would she take him prisoner and bring him to "Eren's ass" as Levi said and separate them by a hoard of powerful, controlled titan shifters if not to ensure they don't get him back until she has taken all of them captive? She knows how powerful Levi and Mikasa are - most likely through Eren's memories. She most likely wants to create a vessel with all nine titans again to merge with Eren fully, maybe even devour him herself, to use her full former strength to get back on humanity and make them pay.

In the first chapter about her backstory it's shown that she was being punished and chased to her "death" because she let the pigs escape - in the last chapter 135, however, in the very first panel, it's shown that she willingly opened the gate to let them escape. She wanted them to run away. Whether or not it was planned that she'd be chased like that and would tumble into the tree trunk is questionable, but I think it has to do with it.

To add to my suspicion of not killing the current inheritors of the nine titans because she needs them later on, look at chapters 114-115 specifically.

Zeke blew himself up in the scene with Levi, and that entirely. He was torn in half. His spine was destroyed and therefore the titan in him "lost" because he had no one to pass it on to. He accepted that he'd die, told himself that. He did die.

But Ymir brought him back. She rebuilt his body and brought him back to life - if she really did that out of pure selflessness and devotion to her people, why didn't she do it with Levi? He's Eldian, too, technically, even if he's an Ackermann.

But Ackermanns are a byproduct and made to protect the royal family, and if we follow my thing right here, then she hated the royal family - she was forced to marry the king and give him offspring, after all. And she was nothing but a child. And she knew how dangerous Levi was - so she planned for him to die while rescuing Zeke, because she had a plan for him while Levi would have only endangered that.

In chapter 110, Zacharias refuses Mikasa and Armin to go see Eren - and promptly dies in an explosion. This might be a hot take, but I think Eren might have ordered someone to do so (because Ymir made him?) - because she needed to split the bond between them. And afterward, Eren escaped. Maybe it was used as a maneuver to get the attention off of him.

In chapter 112 he returns to meet Mikasa and Armin in the table scene - already threatening to transform if they make any move. "I am free. Whatever I do, whatever I choose. I do it out of my own free will."

That's what he says, entirely unprompted really. He proceeds to tell Armin that he's the one being controlled by Bertholt, and I think that mirrors the situation properly. Because it could serve as a parallel that it's not Armin but Eren controlled by "the enemy".

In that chapter, Eren effectively cuts all of the bonds to his friends even though in a few chapters before (when discussing who will inherit his titan once his time is over) he claims to care about them more than anything. And he does. He cares incredibly, he's a very emotional person - but suddenly, all of his emotions are gone. Seems fishy. ‘

He cuts Mikasa off by telling her he's hated her for his whole life, knowing it's her weak spot. He beats Armin up, knowing it's his weak spot because Eren was always there to take hits for him when he got beaten up as a child.

Once again, I think that's Ymir taking control of his memories and using them against him. That, or Eren used those purposefully to get them away from him and out of the danger zone, knowing that he's a time bomb.

In that chapter, it is thickly laid on that Eren "hates" slaves. "Do you know what I hate most in this world? Anyone who isn't free. That, or cattle. Just looking at them made me so angry, now I finally understand why. I couldn't stand to look at an undoubting slave who only ever followed orders."

Maybe, once again, that is Ymir speaking - she was reduced to a slave, and her creation of a titan made to fight was broken down by a vow the Eldian King created. The following inheritors only ever accepted that fate and didn't do anything to break free from it.

In chapter 130 when Eren tells Historia his plan, he says the following:

"The only way to put a final end to the cycle of revenge born from hate is to remove that history of hate from this world and bury it in the ground, civilisation and all." - he knows it's a repeating process, possibly because of previous memories handed down to him through the Attack Titan and looking through the royal bloodline with the Founding Titan (first seen when he kissed Historia's hand).

The cycle of revenge born from hate - gotta keep that in mind, cause I think it's very important looking at all of his actions.

There's this constant reference with his friends. In so many flashbacks, it tells us that Eren wants his friends to have happy lives. To be free. To live long. He adores his friends and loves them with all of his heart. So why tell them he hates them? Why beat them? Why get them involved in all of this?

Because it isn't him saying those things, and if it is there's more behind it.

In chapter 131 he apologizes to a child for everything he is about to do before it even happens. Maybe because he saw the outcome of it all?

He knows how much he will hurt the world and people, but he does it anyway because he needs this cycle to end.

I'm not fully sure what the rest of his apology means, talking about how he was disappointed learning that people lived in the outside world. But what I do think is important is the last panel in that chapter, this one:

It views Eren with his eyes shut. Just his head. Usually, whenever he controls his titan, his eyes are open. His own body moves to control the titan. Here it isn't, though. I feel like that symbolizes how it's not him.

We established that he's a very emotion bound person that often rejects logic to follow his heart - he doesn't have his heart here. He can't listen to it. If you are manipulated the source of that manipulation always tries to break your mind first. Rob you of your beliefs and make you follow others.

The contrast is right then and there - why would he apologies in tears to a child he doesn't know at all and explain his intentions and beliefs when once it happens, and once the child is murdered, he doesn't show any reaction?

Sure, one could argue that he's not conscious after his head was shot off, but who caused the jump and transformation into the titan if not Eren? Possibly Ymir.

It is shown that the user has to focus on that goal to transform, as in season one with Eren and the well, so either Eren was conscious enough - somewhat doubtful - or Ymir had full control of him then and there already as soon as he stepped into paths.

In chapter 133 Reiner says something important; "If it was me, I'd probably.. want someone else to handle the power of the founder by now. And if I couldn't, I'd want it to be stopped by someone."

There's pretty much a direct contrast once again - are Eren and the Rumbling controlled by someone else? In my opinion, yes.

Does he want someone else to stop it? He most likely does, why else would Mikasa, Armin, and co be able to move freely? Ymir not so much.

I feel like he's putting up a resistance to them, which is why she can't control them properly despite them being Eldians.

They get thrown into paths then, and when they see Eren it's him but his younger version. Around nine or ten, probably.

What I think happened here is that Ymir is keeping him trapped in a younger version of himself - similar to that one time he was wrapped up in blankets in his home and Armin was knocking on the window behind him, trying to shake him awake and conscious again.

She's keeping his conscience reminded of good memories to hold him there and be able to move freely with his body - like I said, she's using him as a vessel to push her actions, her dream, her ideal world and outcome into his hands.

"In order to gain my own freedom, I will take freedom away from the world." Sounds a lot like something Ymir could have been saying, in my opinion. But then again, who knows.

This panel is also important:

Eren, in his young form, is simply standing next to Ymir. And he doesn't do anything. He doesn't react or recognize his friends, and most importantly, he mirrors how Ymir is standing in the exact same way.

She's mirroring herself onto him, projecting her conscience onto his body. It proceeds with "If you want to stop me, then try to stop me from ever taking another breath" - once again, and I cannot stress this enough, Ymir uses Eren's memories against him.

She knows his friends won't risk him dying. She knows they would do anything to protect him. This is her playing it safe; they won't kill him, ergo they won't stop her from continuing her plan by using him.

Now in the recent chapter, she's standing on top of his spine and it becomes very clear that she's controlling it all. She's building former titan shifters from his spine, and controlling them to separate the team from Eren's location - and Armin's, most likely even Zeke's.

She figured out that they won't give up until they found Eren and can talk to him, so she creates that barrier that she's sure they won't manage to surpass. Not with limited supplies.

When Pieck becomes a danger, she eliminates her by impaling her on that trident - but she doesn't injure her beyond conscience or in a threatening state. She specifically uses Galliard and Berthold against Reiner, and throws those two on him to damage him in his abilities and trick his mind, to manipulate him.

Armin says it himself: "If Eren is only attacking onward like he said he would then this resistance is coming from Ymir." If Eren is attacking onward to follow the goal to end the cycle, then Ymir is the one bringing all the complications. They might work hand in hand, but I do strongly believe that all of the complications are solely on Ymir. Eren never wanted to risk hurting his friends.

In fact, and this is if he is conscious enough to pull any strings right now, I think he might be setting things up to ensure that his friends are the ones that kill him.

#attack on titan#shingeki no kyoujin#aot season 4#aot spoilers#snk spoilers#aot 135#snk manga#aot manga#eren jaeger#first post lets see how this goes#did i crack a code? maybe.#i did say hot take

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supernatural season 4 review (part 1)

Link to part 2:

Carly and I have been waiting for this season since we started watching Supernatural. She had been sending me Destiel posts and pictures and telling me about them even before we watched the very first episode, so I had a lot of expectations on this particular season, and on one particular character.

Castiel appears from the very beginning (I thought he wouldn’t come out so early) to explain Dean’s inexplicable resurrection. In fact, Dean died at the end of the third season and at the end of his last year on earth due to the deal to save Sam, but we already knew he would survive because the authors would never let him die at the third season and we are no more surprised by the fact that in Supernatural being dead permanently is more unusual than coming back to life after a while.

The first episode is happy and tragic at the same time: Dean wakes up in his coffin (that was pretty disquieting if you ask me) and he manages to come out and reach Bobby. At first he cannot believe he’s really Dean, but Dean convinces him even without knowing how he was saved from hell. Bobby’s pain for Dean’s death is comprehensible, as he considers him as his son, and so it is the confusion he feels seeing him again, but that’s nothing compared to Sam’s reaction. He’s been deeply broken by Dean’s death and, as it was predictable, tried in every way to take him back, and failed (as most of the fans have noticed, this total impossibility of the brothers to live without each other is quite toxic, but from some point of view their entire life is…). In fact he’s so surprised by Dean coming back from hell he can’t hide the fact that Ruby kind of took his brother’s place. She is an interesting character who emerges properly only in this season and develops through it in a quite complex way: I was never able to tell if she really wanted to help the Winchesters, as it seems in the first place, or if she was only following a mysterious path. By the way, thanks to her help and especially her blood, Sam, without Dean in his life to stop him, persuaded himself that the best way to keep hunting was by enhancing his demonic powers in order to kill demons. I’m quite sure he thinks it’s a good compromise between his two sides, good and evil, but I also think that something happens inside him the exact moment he sees his brother again. He’s so afraid of Dean’s judgement he tries to hide his relationship (also romantic, which is quite creepy) with Ruby, also because deep inside he knows what he’s doing is somehow wrong, even if he’s actually saving people. Of course when Dean finds out he gets mad at him, and that’s understandable considering how suspicious he’s always been about Ruby. However, he himself is never really sincere with Sam about what happened in hell, both because he doesn’t want to remember and somehow feel again all that pain and because he feels deeply guilty for having accepted to torture some souls, even after a long period of resistance. Also, Dean’s pain doesn’t end as he’s back in earth, because he meets again several times Alastair, the powerful demon who tortured him in hell and forced him to torture other souls (and I was quite happy when Dean had the chance to get a little revenge and torture him). Of course these big secrets lead to fights and misunderstandings to which we are used, but those issues could have been solved easily, if only they had spoken to each other from the beginning. After a while they finally do clarify their positions, and that’s a relief for us all. Sam tells Dean what Ruby has done saving him on a lot of occasions and partly persuades him to rely on this good demon, but even after this clarification, the problem is not completely solved because Dean can’t but think Sam has replaced him with Ruby and prefers following her advice rather than keep hunting with him. Deep inside Sam has always the same feeling towards his brother: he doesn’t want Dean to treat him like a child, and his biggest struggle is being considered as the little brother who needs protection. That’s why he wants so bad to break free from Dean. Although, he doesn’t understand that also Ruby is patronizing him and, as he acknowledges at the very end, she’s not doing it because she loves and cares about him, but because she needs him.

I’ll jump quickly to the final episode, as we’re talking about Ruby. The main villain of the previous season, Lilith, was not defeated at all: in the last episode we just get to know Sam can resist her, so she has to find another way to take over him. During all the fourth season we see Lilith breaking the so-called “seals”, which will allow her to free Lucifer from his cage down in hell. The boys struggle with that all the time and they don’t know how to stop her, apart from killing her. At the end, Sam decides to do that all by himself, helped by Ruby and by the demon blood he can’t stop drinking at this point, without knowing that’s exactly what he has to do to bring Lucifer back and Ruby has been cheating on him all the time. I do have to admit it was quite a shock, because I had started to like and trust Ruby and to think Dean was a little too paranoiac, and jealous, about her. Maybe it’s just that I liked to think that someone who’s destined to be a monster, like a demon, can actually have a choice and do the good thing. Also Sam always seems to hope that, because he himself has demon blood in his veins and tries to use his evil powers for the good. He mirrors himself in monsters all the time, as in episode 4, when he tries to convince Dean that a bad creature can really control itself if it wants to, but everything, even in this episode, seems to prove him wrong. Even his blood thirst is insatiable and, although he thinks he can control himself and choose the good side (as he thinks he’s doing when he accidentally frees the Devil), at some point in episode 21 Dean and Bobby feel the need to close him into the panic room to detoxify him from demon blood (and they would have succeeded, if he hadn’t managed to escape).

As I mentioned Bobby, I’d like to point out the fact that the boys seem to consider him only when they’re both alive, while, when one of them is (temporarily) dead, the other one is so lost he cuts every link with other human beings, especially Bobby, who in the contrary is always there for them. I just think he deserves a little more consideration and gratitude, because he loves the boys just as they love him and they don’t seem to realise he suffers so much when one of them dies or if he doesn’t know what’s happening to them.

To go back to the final episode, you may wonder what Dean was doing while Sam was freeing Lucifer and starting the apocalypse… To answer this question we have to go back to the beginning and Castiel.

As I said before, this mysterious character appears as Dean’s saver and presents himself as an “angel of the Lord”. Of course we’re as surprised as Dean is hearing that, because we’ve learnt to think the world is full of evil and there’s no such thing as a good supernatural creature, so we wonder what’s the truth. Well, there’s no contradiction: we soon also learn angels aren’t as good as the Bible teaches us (at least the ones in Supernatural). They do exist, so Castiel is not lying, but they just want to do their own good and they don’t care at all about humans (that’s quite paradoxical, that Sam and Dean care more about protecting humanity than angels, and as far as I know God himself, do). But that’s another thing we get to know as the show goes on and that reaches its apex in the last episode.

Of course I already knew something about Castiel (and his “special relationship” with Dean) as Carly told me a lot about him, but still I found his appearance and the whole angel thing quite interesting, especially because at first Cas tries to be solemn and focused on his duty, which is at first even a bit scary, then quite funny considering how his relationship with the brothers will evolve through the season and through the entire series. His character changes a lot not only in his behaviour towards the Winchesters, but also in his faith in God’s and angels’ plans, as he decides to actually do the right thing against all the odds and against his own father, which must’ve been really hard for him, knowing how blindly faithful he was at first. He decides to put himself into the hands of those two guys without knowing anything but they’re fighting to save as many people as possible, and that’s why we love him and consider him the only angel worth the name. The more the show goes on, the more we see the continuous contrast between Castiel’s attitude (at first just a little uncertain) and the other angels’. I’ll mention just two of them for now, Anna and Zacharia. Anna is a girl who’s perceived as crazy because she says she can hear angels speaking, and of course demons hunt her as a means to find out the angels’ plan. When Sam, Dean and Bobby find her and try to help her, they call Pamela, an old friend of Bobby’s who always helps the boys as best as she can (I think she’s one of the characters that help Sam and Dean more and that they never thank enough, considering she finally sacrifices her life to allow them to conclude a hunt successfully). Pamela makes Anna realise she’s a fallen angel, and that explains why she’s able to hear angels’ voices, and after some time, she can go back to heaven, the place she belongs to (only after having randomly had sex with Dean because why not…). Anna’s story is quite unusual compared to the other angels we met: most of them are just sort of powerful and incorporeal spirits, who, just like demons, need a human body to fit in. We see it in detail in episode 20, in the narration of Castiel’s story. I think this mechanism of appropriation of innocent human beings contributes to Supernatural’s evil connotation of angels, who seem to be even more sneaky than demons, because they take advantage of people’s faith to convince them to hold them in their bodies and do whatever they want once they’re into them. Of course this vision of both angels and demons as villains is clearly made to make us sympathise even more with Castiel, who rebelled, and with the brothers, who seem to be the only ones really caring about mankind.

Angels’ wickedness emerges in all its power in the final episode and in the character of Zacharia. That’s the time when the entire plot is solved: Zacharia, an important angel in heaven hierarchy, keeps Deans locked in a sumptuous room to prevent him from stopping Sam from breaking the last seal. Just as Sam doesn’t know what he’s doing while he thinks he’s saving the world from apocalypse, Dean didn’t know angels actually wanted the apocalypse to happen to purify the world and finally defeat demons and Lucifer. It’s quite shocking for him (and also for us) and, even though he had never liked and trusted angels, he’s led to hate them completely. He thought he was brought back from hell because angels wanted him to help saving the world, but he understands it’s exactly the opposite. In addition, I also think the worst feeling for Dean is feeling useless and not being able to protect someone he loves, especially Sam; that makes his situation even more painful, and Zacharia seems to know it well. At the end, he manages to escape, but he can’t stop Sam from killing Lilith and the brothers can do nothing but acknowledge together the beginning of the apocalypse, which will be the main theme of the following season.

I’ll go rapidly through the single episodes as usual, to highlight some I particularly liked.

I found the fifth episode, the one in which a monster fakes itself into Dracula, quite original and I appreciated the mixture of colored and black-and-white scenes, aimed to mark the difference between “reality” and the movie set up by our Dracula. In the sixth episode we are shown a hidden side of Dean, an uncontrolled fear which is of course aroused by something the brothers are hunting, but which is also credible imagine is actually an emotion Dean constantly feels in his dangerous life but can’t allow himself to show. One of my favourites of the season is episode 8, where all people’s wishes come true, because the scene of the little girl wishing for a giant teddy bear and actually getting it was so funny and scary at the same time. Episode 13 gives us another piece of the puzzle to reconstruct Sam and Dean’s childhood and youth, as they work a case in a school they had attended: apart from blaming John for making his sons change home and school so often they can’t even make friends or built a sort of life, these highlights from the boy’s past provide us even more information to understand how they became the men we see in the present and how they were, and still are, deeply different from one another.

I feel I have to mention a new character, who is quite important for the Winchesters and also recurrent in the show, Adam. He randomly comes out as Sam and Dean’s half-brother, son of John and a local woman he met during a hunt; of course at first the Winchesters don’t believe him, but at some point they have to face the truth and kind of feel sympathetic with him for John’s absence during his growth, because they’ve been through the same issues even if in theory their father lived with them. Moreover, Adam’s appearance testify once again Sam and Dean’s biggest weakness: even if they don’t know Adam at all, they can’t help but try to save him and give him love (especially Sam, I have to say) welcoming him into the family. That’s so cute, but that’s also what keeps bringing them troubles.

I’ll end my review with episode 14: the hunted monster is a siren, which, as you all probably already know, shapes itself as a male federal agent to seduce Dean. “Big hint of Dean’s bisexuality!!”, I can hear some of you scream. What I think is that the explanation the episode gives for it (the siren takes the shape of a man similar to Dean, in other words the type of brother Dean has always wanted) is quite convincing, and is not the strongest element to sustain Dean’s queerness. I’ll impatiently wait for other clues in the next seasons…

- Irene 💕

#Supernatural#spn#Spn season four#spn review#sam#sam winchester#dean#dean winchester#castiel#destiel#deancas#bobby#bobby singer#ruby spn#adam winchester#bi dean#first time watching supernatural

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AN EVEN DEEPER DIVE™ INTO THE THEMATIC SYMMETRY IN MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE.

A Breakdown of the character relationships in Rogue Nation and Fallout

For: @not-too-tall-for-trick

Y’all, I literally spent four days of my spring break working on this Rogue Nation Analysis Video and I also made this post a while ago touching on this subject, but I really can’t stop thinking about this. So here we go diving deeper into the implications of the characterizations of Ethan, Ilsa, Lane, and Benji.

Ethan Hunt will always do good no matter the cost. He disregards his own wellbeing if it means that the world will be safe. This is consistent in his characterization throughout the franchise. Which leads to the tragic implications that Ethan and by extension Team Hunt aren’t fully realized, elf-actualized people. They are tools for the government they work for, even if they are not loyal to that government.

Ethan’s loyalties despite everything he has gone through has always been on the side of protecting human life and the innocent. And he has remained able to keep a steady head on him, unwilling to sacrifice the needs of one over the needs of the many. Hunley even says as much to him in the beginning of Fallout. But never once throughout Rogue Nation and Fallout does the audience ever see Ethan being concerned with his own wellbeing.

When The boat scene in Rogue Nation occurs, Ethan already has made a decision to send Benji away: “I can’t protect you, that’s why I NEED you to leave.” The dialogue here is very significant. It’s not a want, a selfish desire. No. Ethan needs Benji to stay safe which is want informs a majority of the decisions he makes in Rogue Nation especially. The entire plot of Fallout kicks off because he was unwilling to let Luther, his oldest friend, die.

Ethan can never choose between the needs of the few and the needs of the many, at that includes himself.

Ethan, having done this for like some 20 odd years now, understands this. Ilsa however differs, but they go through similar circumstances that parallel and make them interesting to analyze closer.

Ilsa is not a bad character, (morally speaking anyway, her character in the narrative is fucking amazing and I love her and so do all my other film major friends) She has different priorities than Ethan, yet they strive for similar things, making them thematic mirrors/parallels.

Ilsa is put in a similar situation of having to go rogue in order to bring down the syndicate, she is forced to be disloyal to her government in order to live. Ilsa still holds on to her personhood and does not accept that she must be loyal to Lane or Atlee. She and Ethan agree that Lane needs to be stopped and no one will believe them, but she still believes she can walk away from the spy world and become a free woman.

“Lane, Atlee, your government, my government, they’re all the same. We only think we are fighting for the right side because that’s what we choose to believe.”

She is ideologically more aligned with Ethan than she is with Lane. She does not agree with his methods, but she understands why Lane is opposed to his government. She is concerned with survival above all else, which is why in Fallout she must kill Lane. Otherwise, she will never again be able to live in peace.

So, both Ethan and Ilsa experience similar character arcs, but they go about it in different ways making them not foils but parallels of each other. They are on equal standing in the narrative but can’t see eye to eye in a few things.

Contrast that between Lane and Benji. The narrative between both Rogue Nation and Fallout posits them against each other and are in an odd position of being mirrors of the other, as well as being highly antagonistic towards each other to quote my friend @Snovyda

“Which is peculiar, because usually, parallels are drawn between the main villain and the main hero. Not between the villain and the hero's friend.”

They aren’t exactly mirrors, but they are linked thematically, they are connected

See, they are both competing for Ethan’s attention (not in a ship or romantic way, I just don’t have a better way to say that, the English language can only take me so far.)

It’s inferred that Ethan was to be turned to Lane’s side after that whole torture sequence, in which Ethan looks like a whole ass snac (rip sorry it’s just Tom Cruise’s Arms Make me feel safe, amongst other things) Vinter even says “What does He [Lane] see in you, I wonder?” Lane saw protentional in Ethan to become a terrorist (That’s what he is be we don’t really have time to unpack all that.) And Lane was attempting to manipulate Ethan by whichever means to get what he wants, which is ultimately the disk. To him, human nature is something easily manipulated, which is somewhat proven right when Ethan unlocks the disk in order to keep Benji safe.

Lane sees no other way to becoming his own person than through terroristic acts. He also is definitely the leader of The Syndicate; he shoots those he deems have outlived their usefulness and the audience is never shown if he ever takes any advice from those around him. He is violent, cold, calculating. Contrast with Ethan who is caring and compassionate and only managing to get by, but because he values his team’s input, because they are all equals, he prevails.

Benji is competing for Ethan’s attention in that, he wants Ethan to know that he does not need to be alone on his mission to stop The Syndicate. He wants to be seen as just as capable. He and Lane are both monitored intensely by their government, and how they react to this informs the audience of their character’s and make them appear as thematic mirrors of the other. They both rebel against their government, in order to achieve their goals. Benji wants to help Ethan and take down The Syndicate even if he does not come to believe that the syndicate really exists at first.

Lane from the get-go seems to know about Ilsa’s mission to infiltrate his group but still believes in her potential, it is not until he realizes the disk is empty, that he truly turns against her.

In Fallout, Lane who is far more concerned with revenge, states this to Ilsa: “Ethan Hunt will lose everything and everyone that he ever cared about.” And immediately after that, the audience hears Benji’s voice coming from the off-screen space. The editing is very intentional in setting up that Lane is not referring to Ilsa, but Benji. The dialogue choice is very deliberate here. Because first off, the laymen will take “everything” to include “everyone”. The way Lane does this is very reminiscent of their conversation in the graveyard in Rogue Nation. “I’d like to see who you blame for what happens next.”

He is making it clear that whatever is to happen in the following encounter, it is her fault. If Benji dies his blood will be on her hands. This also makes it clear to the audience that Benji, is the “everyone” that Ethan cares about. Which is quite telling and functions on two levels in the narrative.

Firstly, Benji serves as a metonym of the entire conflict that Ethan has throughout the course of the narrative. His Team vs The Mission. Secondly, it reinforces that idea that Lane and Benji are forcibly connected.

Lane attempts to hang Benji, not shoot him or any quicker means of murder. No, he ties a noose around his neck and forcibly hangs him. Benji is the one that got away, the one who lived. Benji is the one Ethan’s attention was on, and how perfect it would be to kill him now that Ethan’s attention lies elsewhere.

The reasoning Lane has however also extends in his logic for tying Ilsa up. While it seems that His revenge is sole focused on quite brutally killing Benji, it isn’t.

Ilsa refuses to kill an ally or any innocent person. Her final test was based on killing both Ethan and Benji after Lane got the disk. Yet she refused. Because he has known her for a longer period of time he is able to use this knowledge in order to enact his revenge.

Vinter says something quite apt in Rogue Nation, that is “People break in different ways” and so the same logic applies here. Lane’s aim here is for Ilsa to be made to feel helpless, making her complicit in Benji’s murder. That’s why Lane gives his whole revenge speech to her. She is not meant to be included in the “everything and everyone”, she is just an observer, forced to watch Benji die, She is apart from them, and Benji, whom Lane knows Ethan would sacrifice anything for, is the one he sets his eyes on to be more brutal.

The Character dynamics between these four are very connected and reinforced through the narratives making them, if not mirrors of each other, then thematically linked at the very least.

#Mission: Impossible#Salty Film Major™#benthan#ethan hunt#ilsa faust#solomon lane#benji dunn#supergeekytoon#rogue nation#mission impossible fallout#this took me less time than i thought#i guess cause i am so used to if by now#anyway let me know what y'all think#i always love feedback

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danganronpa: Parallels Between Class Trials 1 and 5

I’m sure someone far more familiar with Danganronpa has made this observation and has articulated it better, but a certain set of events I’ve noticed in the first game seem to mirror each other. Namely, class trials one and five: the ones where Makoto Naegi is attempted to be framed.

For starters, there’s who the framer is in each situation. For the first trial, Sayaka Maizono is the one who attempted to frame Makoto, even if it went wrong and she died. In the fifth, it’s Kyoko Kirigiri attempting to frame him even if neither actually committed the murder.

It’s interesting that in both instances, the person attempting to frame Makoto is the person he’s closest with at the time, to the point where romantic feelings are implied at some point. Sayaka and Makoto immediately grew close before she was killed, and we see Makoto and Kyoko both grow closer throughout the game, even if the latter tries not to reveal too much about herself.

As we all know, things went very differently for the both of them. Sayaka was hesitant and instead ended up killed by Leon, but since she planned everything Makoto was still framed for her murder and he had to prove everyone otherwise. Kyoko doesn’t die obviously, but actually succeeds even though the position she was placed in was more a matter of circumstance: Makoto purely happened to be the most likely person besides her (even if neither actually committed this murder that wasn’t even new), so she had to make him seem suspicious to survive.

Their motives also actually have a rather interesting contrast. Sayaka was purely scared as anyone reasonably would be, and after seeing the video of her pop group disbanded she felt like she needed to get out at any cost. Including framing the person she is closest to at Hope’s Peak. Basically, there was a more selfish element to her reasoning, even if there was a bit that seemed to be motivated by the people who were basically her best friends breaking up and likely in terrible conditions now.

Kyoko on the other hand is someone determined to uncover the mystery of Hope’s Peak and stop the mastermind. Instead of being driven by fear and despair, she’s being pragmatic. Pragmatic to the point where if someone has to die so that the truth can be uncovered (and therefore, everyone else can stop suffering and this evil can be defeated), she will pursue that path. Sayaka was driven by her intense emotions, Kyoko was putting them aside to pursue what was she viewed as important for everyone as a whole at the time.

Even if her motives are obviously more selfless here, there is still a selfish bent akin to how Sayaka has a slight selfless one: she believes she needs to be alive for the mysteries of Hope Peak to be unraveled. It is somewhat arrogant on her part, yes, but the curious thing is... she’s actually right. In the bad ending where she’s killed instead of Makoto, we see that everyone lives in Hope’s Peak for the rest of their lives and pretty much just accepts it.

Thing is, Makoto needed to survive too. We see this in the climax of the game where he’s necessary to keep hope alive in everyone as Junko reveals the truth about the outside world to them, which honestly would be despair inducing in anyone. When Makoto was sent to be executed and she wasn’t, it not only became clear to her that trial five was indeed set up, but that the Mastermind saw Makoto as a threat too. She recognised she was one piece of the puzzle, but even if she was aware of Makoto’s ideals and optimism, here is when it actually hit her that he was the other piece they needed to get out.

I also think there’s a curious element of hesitation and regret with both of these trials. With Sayaka, she was driven to get out to the point of betraying the person she grew closest to, but I do agree with the idea that she was conflicted about her decision. I mean, Kyoko believes her hesitation is actually what caused her plan to fail and end up with her killed. She didn’t want to frame Makoto and end up with him dead, but she put her survival first. When she was killed by Leon, she very well could’ve spelt out his name as an act of revenge, but obviously doing so would save Makoto and the others. She probably did regret attempting murder in the end, especially after Makoto promised he’d find a way for them to get out together.

With Kyoko, it might not make itself apparent until after Makoto’s attempted execution, but I really doubt she was okay with putting the one person who believed in her, someone who had actually managed to befriend her, under the bus the way she did.

All their interactions before this trial suggested that Kyoko was genuinely warming up to Makoto - I mean, she was pretty clearly upset at him not discussing the possibility of Sakura Ogami being a mole less about the idea that he knew something that she didn’t, but that he offered trust and when having a chance to prove it goes both ways he blows it. Basically, she allowed to open herself up only to feel betrayed. She was upset because she was beginning to see Makoto as a friend and was warming up to him.

She goes back to being her usual more distant self after that brief falling out, but they still spent all this time together and got to know each other. When the fifth trial came, she knew that she may have had to make sacrifices, and of course was able to put any feelings aside to achieve that. She was quite clearly lying to frame Makoto, but she did what she had to for her survival. Thing is... she may be pragmatic enough to achieve this, but deep down I bet she was pretty upset at what she may have had to do to survive.

This all culminates in Makoto’s attempted execution. This is when she realises her mistake of putting her survival (and in her eyes, what’s necessary to uncover the school’s mysteries) first. She may have thrown a wrench into the Mastermind’s game, but this was still a friend she was risking for it all. Sure, she does admit she can’t solve the mysteries of the school alone, but that’s not there all there is to it: Makoto is a friend, possibly her only friend at this point. One she literally just saved from being the actual murder the trial would focus on. The regret is strong enough for her to literally go into a garbage dump to find and rescue Makoto. Not only that, but she’s actually trying to look out for his wellbeing since she brings food and water, and actually is willing top open up about her past to show she’s more trustworthy.

I think there’s also a mirror in regards to trust. With Sayaka, regardless of how conflicted she was with carrying out her plan, she still took advantage of Makoto’s trust in her. A big thing in the first trial was Makoto realising that he needed to put aside his preconceptions to actually face the truth: that Sayaka was attempting to frame him. Here, Makoto was too willing to trust her, and that easily could’ve been his downfall.

With the fifth trial however, Kyoko is quite obviously lying to frame Makoto, and Makoto specifically spots a lie that only he could know in regards to the Monokuma key that can open any door. This is quite clearly a betrayal, but Makoto chooses to trust Kyoko regardless. Why? Well, I mean he wasn’t declared the Ultimate Hope in the game’s climax for nothing.

Instead of a more oblivious trust he placed in Sayaka based more on a small shared past and mutual romantic attraction, the trust he placed in Kyoko was one that proved to work out with experience. Instead of trusting Sayaka because of the relationship they had, the experiences Makoto and Kyoko shared and their working together ended up helping form their very relationship.

I tie this to the Ultimate Hope thing because as Makoto’s optimism is his big thing, he chose to have hope that Kyoko had ulterior motives since they both realised the fifth trial was rigged. He could’ve continued insisting he wasn’t guilty, but he took a massive risk that could’ve ended his own life because he believed Kyoko had a plan as she usually does. And of course, experiencing each other’s methods over the game ended up forming their friendship, and that caused Makoto to trust her not only as someone he worked with, but as a friend.

Makoto’s trust in Kyoko ended up being a gamble that worked because even though neither knew it and this was indeed a massive risk, Makoto was saved by Alter Ego. Here, Makoto’s luck, and more importantly hope, really did win out. Of course, as discussed Kyoko didn’t realise Makoto actually would make it out and really was putting his life on the line, but he still trusted her enough to take what was the biggest risk of his life at that point.

Some smaller things too:

I also noticed that preceding both trials, there is some pretty significant stuff that happens where stuff happens with both Sayaka and Kyoko that is quite concerning and gets Makoto worried: Sayaka has her freak out and goes into panic mode, while Kyoko disappears until the trial actually gets started (though in the anime she actually shows up for the investigation, even if Makoto’s worrying is still there).

Before both murders are discovered, there is a major incident where both Sayaka and Kyoko come to Makoto’s room. Sayaka comes because she claims to be scared of someone breaking into her room, while Kyoko comes over as Makoto is sleeping to save him from being killed by the Mastermind.

This is probably the wildest stretch of them all, but in the events leading up to both of these cases, there is a rather... lewd reference to their potential romantic development in both cases. With Sayaka, it’s the suggestion to sleep in Makoto’s bed, which prompts a brief moment of shock because of the sexual connotations of this act in most cases elsewhere. With Kyoko, it’s when Makoto is diverting Monokuma’s attention, and Monokuma asks what they’re doing in the bathroom, claiming it must be something dirty.

I’m not exactly sure where this is going, but I think this is interesting to look at. I guess if anything, these situations kind of mirror each other as a way to show how both characters Makoto grows close to and their respective relationships with him end up comparing and contrasting? Something like that, if anyone can articulate something better then go ahead.

#honestly this might be more of an infodump than a proper analysis lol#danganronpa#makoto naegi#kyoko kirigiri#sayaka maizono

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

DGM: It's pretty fascinating how the main 4 relate to Death. For all of them it's both simple yet very complex (honestly I wouldn't have room for maybe even one of them). Kanda protects people as best as he can but when they die he moves on very fast accepting that's part of the world he lives in. The only exception is his 'that person' who he refuses to believe is dead despite the possibility of it being so likely. And then it becomes Alma. Ouch. But again Alma dies and Kanda accepts that-

2 being happy things are made right between them before Alma goes and not letting Alma's burden him. In fact he's pushed forward by the restored bond and honest. Out of gratitude, his way of freeing Allen fro m the 14th is death if it comes to that. Kanda making it his priority in fact to be the one to kill Nea for Allen's sake. Alma got to die as himself. So will Allen. Lenalee is the strangest in some ways. She cares so much about her people she feels a part of her world gets destroyed if one-

3 person dies. She's kind of like Kanda though in that she can also move on really fast. She'll feel sad but not broken. Ex, Everyone thought all of the trapped Order members died during the Invasion when the L4 woke up. After Allen and Lenalee found out they survived, Allen broke down sobbing. Lenalee clapped her hands and smiled. 1 reaction seems bigger then the other. Not to say Lenalee can't be broken. Losing Allen nearly sent her comatose. She'd lose her mind if anything happened to Komui-

4 I think like Kanda, Lenalee has just seen so much death she just has to keep moving on fast like that. She's way more openly emotional about it but that sense of acceptance vs unacceptance is always inside her. I feel like Allen and Komui are the 2 people she cannonly can't accept death from because she relies on them too much (contrast to,her thinking Allen died to thinking Kanda died. Its not that she cares less at all but they both have different roles in her life). Lenalee can accept -

5 death and properly mourn a person she loved. But she is terrified of people she loves dying. Dying is more of a trigger death itself. Also let it be known she's ruthless. The only other Exorcist besides her to kill a Third was Sokaro (who implied he had to jump in and do it because Krory couldn't bare to). She hated to do it. But she did it (I don't think I did her justice but lets move on). Lavi. Wow Lavi he's someone who hates death. Like more then anyone. At least he's among the worst -

6 at coping with it. He spent most of his life watching humans massacre each other causing his hatred of humanity to blossom. Then his first real friend (Dug) died and his body became a akuma, forcing Lavi to kill it. But that only enforced Lavi's detached outlook on life. Ink was Ink. For whatever reason, Allen became the first real death he couldn't walk away from. There was actually a lot of things about it that have impacted Lavi's security. 1) Allen showed good humans like him existed -

7 and died unfairly. Things got darker. 2) for the first time Lavi suffered guilt and helplessness. He could have killed the akuma that made off w/Allen but failed. This was probably a 1st for him that a person he liked died (in his view) because he wasn't good enough. 3) it's pretty much canon every time someone he cares for dies Lavi gets triggered remembering the night Allen died. That night symbolized Lavi's humanity and he hates how much it hurts. Death is such a deep issue for Lavi. -

7 Death of himself is scary. But was prepared to kill 'Lavi' the mask if it interfered w/his goals. He was prepared to die to save Allen and Lenalee and beat Road. Death is natural. But humans killing humans is unsettling. Despite being so logical, being helpless to save his friends can make him illogical. All the pent up rage, hatred, despair and loneliness (and I believe a part of Lavi is very lonely) rush forward to the surface. He can become the most revenge driven and will settle things-

8 with death as the answer for the target if he lost something precious enough. Death is Lavi's worst trigger. It reminds him of how powerless and insignificant his own humanity is, no matter how above it he tries to be. In that way he can contrast Kanda who can find strength from death while Lavi finds only weakness. I thought I was going to yak about Allen. But Allen is Waaaay too much. I couldn't even death the surface w/o running out if room. But yeah their dynamic w/death is interesting.

This is fascinating and thank you so much for putting it into words and into my inbox!

I think you’re spot on on everyone and i don’t really know what to add, and going onto Allen would be... boy where to even start, the guy’s story had been kickstarted by the death of his father and the guilt he felt toward it and the whole “i cannot mourn or the Earl will find me”.

In a way, I think all of this adding up makes a really neat tie in with the fact the enemy, the Earl, is weaponizing Death to start with. As in, the Noah don’t just spread death, they use people who died and the grief that comes from it in order to further harm people. Perhaps that’s why the two who were raised inside the Order have a better ability to at least handle it and move on? Because they really have been sent on battlefields when they were children with that very specific mindset and threat of the Earl anytime.

which makes me think, Lenalee especially reacted badly for Allen’s death for the same reason Lavi did: she felt guilty about it. she told him they needed to save Suman, she left him alone to save the little girl, and when Lavi yells at her about “there’s nothing we could have done” we see both the Lavi scene you mention showing he feels guitly the Akuma took Allen away leading him to his death, and Lenalee’s flashback of her moments with Allen. So it’s possible that the guilt that settled after Suman might haunt her for ever about Allen, especially with how much he gives her strength, while for Kanda for exemple, she grew up with him and they probably had a whole “we can die in battle anytime” mentality growing up that she might not have projected on Allen yet. Basically what i’m saying is that she had her whole life to come to term with the fact Kanda might not come back from a battlefield. But for Allen it was barely a couple of months and the guilt that sank in making it all the more difficult.

Anyway back to my point, Lenalee and Kanda specifically having grown up in a war where grief was your greatest enemy’s strength, and who have both been child soldiers with a lot of loss to witness everytime (Lavi meets Lenalee while she’s crying over losses of a newest battle for exemple), so they have to find a way to move on and get used to it somehow. Both however refused to give up on their humanity while doing so: I suspect because both were holding onto the war for very personal feelings reason: Kanda to find That Person, and Lenalee so Komui’s sacrifice of joining the Order for her wouldn’t be in vain.

Thus they have the distachement necessary from growing up in this state, but the emotional attachement needed to not lose completely their sense of humanity- in a way they find a way to ground themselves in the life they have to keep moving on into. It was their way to not let grief find them.

In opposition, even if Allen grew up always knowing of the Earl and after the Mana incident, of Akuma and such, Allen hadn’t grown up in the war. We know Cross rejected the Order’s orders and Allen was more concerned most of the time with the casual nightmare Cross’s life brought up. So Allen’s relationship with grief is one he had to deal with on a personal level (a bit like Kanda regarding Alma, while Kanda did manage to move on more than Allen, there are a lot of things that ties him back to the memories of Alma - it’s just that Kanda could move on by thinking of another alive person while Allen lives on for a memory. The irony is that Kanda’s “alive person” was Alma and now he’s dead, and that Allen lives for a memory of a dead person who is alive and is actually his enemy now. Oops.)

In a way Allen didn’t have to go back into thinking about the casulties of war to such a degree, he didn’t grow up on the battlefield, in a way he was more sheltered than litteral child soldiers who could be sent anywhere anytime. I think it’s interesting too that we’ve seen how Allen’s direct grief after Mana’s death affected him when you can compare to Kanda’s direct grief after Alma’s death for exemple. Allen had the time to freak out, to be a mess, the few flashbacks we have of directly after Mana’s death show that for all the terrible parenting Cross had done he actually gave all the time Allen needed to recover with his freak outs. But with Kanda after having to kill Alma, we don’t have much except that he had to immediatly be on the run with Marie until they could find Tiedoll.And I seriously doubt Kanda would have ever shown the amount of distress Allen had shown afterward - because Kanda was already daily tortured and a product of the war by that point while Allen barely knew about the war at all.

When Allen the dog dies Allen is frustrated that Mana doesn’t show grief. He considers it abnormal. Which now that I think about it can mirror a lot how Kanda thought it wasn’t normal Alma kept on smiling after all the tortures they endured together and that’s why they fought a lot before realizing how much they just coped differently with the same event.

... I lost my point wait.

Anyway yeah so, the thing is, Mana did mention the Earl multiple times before but Allen always thought it was just something weird, and the “I can’t grief or the Earl will find me” thing was something Mana kept repeating but Allen didn’t get until the Earl actually found him. Allen paid the high price from not handling his grief and had since then forced himself to move on as quickly as possible without processing the grief because he’s traumatized by the event. In a way, both Kanda and Lenalee knew enough about the Earl to find another way to process death, and they have seen much more deaths than Allen has during his training with Cross one would assume, so they developped others coping mechanisms where Allen could just focus on the one he inherited from Mana. (and there is also a lot to say about how he is just repeating the same thing Mana used to say - Allen coped by copying Mana in every way after all. Kanda and Lenalee’s rolemodels are unlikely to be the dead person they would have had to kill and grief. Lenalee doesn’t have such a person in her life that we know of and Kanda didn’t take Alma as a rolemodel. So it’s already another aspect of how to relate to death).

Which brings us to Lavi and you’re entierely right about everything, i’m just adding: since Lavi have grown up wars after wars, it was indeed easier for him to deshumanize everyone around him in order to not feel attached. There’s no grief to process when you don’t have the attachement to the people who are dying. Which is already something that opposes the others three who all have clear people they care about so they risk grief, so they have to find a way around it. Lavi tried to protect himself from grief by not caring enough to have any reasons to, which was doomed to fall back against him because he couldn’t just not care for people.

Which now make me think specifically since when did Lavi know about the Earl and the Holy War? After all considering Bookman was on the Noah’s side 40 years ago there’s no way he wouldn’t know that grieving is a major risk in general. Which could add to why the non emotion rule even exist within the Bookmen. I doubt something that huge, that dangerous, wouldn’t be mentioned to a child who is doomed to see grief after grief. But it feels like they took it by the wrong end.

I think it’s that, with Lavi being an observer rather than a soldier, it was far easier to distach himself than for Kanda or Lenalee. Kanda and Lenalee by being on the field are always aware of how the rest of the people may be hurt in a mission. It’s more than likely that at some point, when they were young, some finders may have died because they weren’t quick enough, or died protecting them specifically because they can’t afford losing exorcists. It seems a given. So Kanda and Lenalee specifically has to deal with the fact people can die because of/for them. Lavi (and Allen on that regard) doesn’t. Because he’s not supposed to be on the battlefield enough to develop this sort of thing. So Kanda and Lenalee were in situation where the loss of people they couldn’t save were directly on their conscience and they had to find ways to deal with it. Lavi doesn’t have any reasons to have had this sort of dynamic with anyone on the battlefields he had been into.

and it’s not even mentioning that for Kanda and Lenalee, they grew up in the Order so they know the others soldiers to some degree and know why the soldiers sign up/are forced to join. They know the ultimate goal and had grown used to it.

Lavi meanwhile had seen 49 wars, before the Holy War, he seems he stayed 4 months on each wars’s battlefield. No time to get used to people and to their motivations. so the easier to make it (”humans just like to destroy each other”) the less likely you torture yourself over what those conflicts bring. Which is signifiant that it’s the war he’s been into now for 4 years in canon that is now weighing on him and makes him unable to not face his grief. Except that it’s the very war where giving in to grief isn’t an option.

And I would be really curious about if Lavi grew up with the back on his mind that grief and the Earl was an issue, because therefore just like Allen there would be a deliberate choice tonot let grief get to you, without Lenalee and Kanda’s being forced to see too much grief in order to process it.

... okay for someone who doesnt know what to add i added a lot kjdhfdkjf

But my point, the reason why i ended up developping that while you’ve been perfectly spot on and i feel like i’m just repeating your points, is specifically how relevent it is that the 4 main characters have very specific ways to deal with Grief and Death, while the main villain is constantly weaponizing both Grief and Death. So there is this whole thing too about the degree of awareness about the Earl, and how much the characters had been subjected to grief in order to find their way to cope with it to keep the Earl at bay.

And I think it’s really, really fascinating that they all have their very distinct way to deal with it with different reasons each, and it’s arguably very ironic that Lavi, who’s the one who’s the most distached from the war where grieving is your enemy, that is the one who has never learned to grief properly. Evenmore so when you can argue that all the people who almost died near Lavi enough to push him to complete panic were all people who had been specifically aware of all of that, who all dealt with grief to some extend (Lenalee specifically pushed herself to her limits against Eshii because she still grieved Allen for exemple - Allen’s actions are still shadowed by his grief toward Mana - Even Chomesuke dying add to that considering an Akuma is made of said grief.)

The way Lenalee, Kanda and Allen all deal with grief is super interesting as for what it means to the way they have grown up in the war, and ultimately, the Holy War had been the center of their lives. It never was Lavi’s however, so it is incredible to see how much grief had taken him by surprise and keeps challenging him over and over again, leaving him in complete distress.

The rapport they all have with death is fascinating to me. And it works so so so well with the fact the enemy is specifically using grief as a weapon. It makes such for a strong theme to run through the main characters it’s just. Gahh i’m just repeating myself but i love it.

thank you so much again for the initial ask! this is very spot on on all the characters and it sooo good to read!

#long post for ts#weeee it's just. so much to talk about#ichafantalks dgm#ichameta dgm#Anonymous#ichareply

1 note

·

View note

Text

Desire vs. Responsibility: Joshua and L’Arachel

While these two aren’t a sibling duo like Eirika-Ephraim and Innes-Tana, Joshua and L’Arachel also play important roles in the story as supporting characters.

Joshua is, for all intents and purposes, living exactly the kind of life that Ephraim sought after, and thus has a contrast with Innes that is explored in their supports. L’Arachel has Tana’s outgoing and loud personality, but it hides a more sensitive and emotional side that is like Eirika’s—or, perhaps, even Lyon’s. However, Joshua is driven more by his responsibilities (at least as a pretense), and L’Arachel her desires, which makes them a “balance” between the other two royal sets.

Joshua

Joshua is an interesting mixture of desire and responsibility. His intentions are rooted in his responsibilities, but most (if not all) of his actions in-game are tinged by his desires.

When he was a child, his father died, likely of illness. According his father’s will, his mother, Ismaire, took the throne as queen regent due to Joshua’s age. However, it was hard on her, as indicated by her dialogue with Carlyle about how “It was through your unwavering support alone that I still sit upon the throne,” and her dying apology to Joshua that “I was so intent on being queen that I spared no time to be your mother.” Provided that he’s alive, Joshua will afterwards state:

I’d grown tied of the formality of palace life, so I...just left. I wrote a farewell and left the palace, taking nothing with me. I felt I could never understand the people while I stayed sequestered in a castle. I abandoned my identity and roamed the continent, working where I could. I wanted only to be worthy of becoming king. [...] I was such a child, I see it now. Was I simply rebelling against my mother? Punishing her for tending to her duties?

While Joshua gets to live the life that Ephraim wanted, Joshua left with the intention of doing it to become a better king—though in hindsight, he himself believes he was motivated more by resentment towards his mother’s neglect. Ephraim, meanwhile, had no intention of using new experiences to become a better ruler. He wanted to discard his title completely. Because of this, while Joshua’s situation bears similarity to the situation that Ephraim desires, his objective is more along Innes’ line of thinking. In fact, in their A support, they have this exchange:

Innes: Interesting. I’ve never had any experience with this sort of thing. One only has so much time when he’s groomed to become the king, you know.

Joshua: I can imagine. But a king must have a wide range of knowledge, don’t you think? When I was a journeyman, I lost a lot of money to scams like this. I started learning these tricks so they couldn’t be used on me anymore! It’s all rubbish, innit? But it’s not a bad thing to add to your experience.

Innes: I must hand it to you, you have a point. Some things, you can only learn firsthand, on the field.

Joshua’s side plot bears many similarities to Eirika’s story, so it’s little wonder that we find out about it on her route. Both became/posed as mercenaries after running away from home to avoid being recognized; however, both intended to return to their country to fulfill their duties. Their only remaining parent is slain by Grado’s forces without them able to do anything about it, and they vow to put an end to the war and restore their homelands. Furthermore, they are betrayed by someone who should have been loyal to their cause: Carlyle for Joshua, Orson for Eirika.

Joshua and L’Arachel are mirrors in their implied lonely childhoods; Ismaire was too preoccupied with the court to make time for Joshua, and while L’Arachel has a good relationship with her uncle, she is constantly burdened by the knowledge that her parents died before she could even form memories of them. Eventually, they leave home to go on an adventure.

However, this is just about where their similarities end. Joshua snuck away without anyone knowing and was able to keep up his disguise for around ten years. Meanwhile, L’Arachel demanded that she be allowed to travel on her very-non-anonymous journey. (Her best disguise is the fact that her very existence is practically unknown.) Furthermore, Joshua ran away out of a mixture of disgruntlement towards his home life and to learn more about his people. Though L’Arachel claims to be on a holy mission to exterminate monsters, it becomes quite evident in her supports with Dozla that it is more ego-driven than charity... to speak nothing of the fact that she can’t even fight monsters herself when you meet her.

This isn’t to say Joshua’s a shining model of responsibility. As the game makes clear enough, he has a bad gambling addiction, and as his solo ending tells us, he also has a wanderlust persists for the rest of his life (it only settles in his paired ending with Natasha). Those aren’t exactly qualities you want to find in a future king, and he never really gets penalized for his gambling ways outside of his supports with Gerik and L’Arachel. In Gerik’s, Gerik sees through his trick and calls him out on it; in L’Arachel’s, her divine luck surpasses any attempt of Joshua’s to cheat her out. However, neither of those “lessons” permanently stick on him anyways.

Furthermore, we shouldn’t ignore the fact that Joshua’s been away from home for ten years. After Ismaire’s death, he says, “I knew one day I would return.” Doesn’t sound like he had a plan about when he would return, not to mention that it’s completely possible for him to die before he makes it back. Unlike Innes and L’Arachel, he won’t retreat when he’s gravely injured. He has no true consideration for his mother, nor of the fact that he’s left the throne vacant should Ismaire meet an untimely death. She does, and it’s only by chance that, if he’s alive, Joshua reunites with her as she lays bleeding to death on the floor. It’s after this turn events that Joshua vows to join forces with the other royals put an end to the Demon King’s threat.

Luckily for Joshua, the story isn’t a political one, and the game didn’t want you to lose a unit for their political duties. Realistically, his almost-immediate departure from Jehanna after it just lost its known leaders (Ismaire and Carlyle) would have thrown the country into chaos. (Though, if there are roughly two weeks between each chapter, he may have organized something before leaving.) Of course, this assumes that people would accept Joshua as king to begin with, after his ten-year disappearance. Long in short, Joshua’s irresponsibility gets handwaved in FE8 because politics are nonexistent. Sure, you can disguise yourself among the people to discover how to best rule them, but it’s all for naught if you can’t even get the throne afterwards.

(He’s also lucky that all the other royals, save for Innes, are laid-back people. Being away from the royal court and living as a mercenary for 10 years probably means he’d have a hard time dealing with court intricacies... the very ones that consumed Ismaire to the point that Joshua ran away.)

L’Arachel