#in a modern Dickens style tv show

Text

Finished watching The Artful Dodger and, honestly?

I need a season 2. Pronto.

#this show is such a weird mix#its a period piece#a medical drama#criminal heist#historical romance#in a modern Dickens style tv show#based on character from Oliver Twist#set in Australia#and it all freaking works#ok Belle was a tiny bit annoying at first#and there's one character twist that I hate#(seriously that was so not needed)#but over all its a great show#really hope for a season 2#the artful dodger#tv shows#things i like

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a not yet fully formed thought about how Grant Morrison ties into all of this that I’ll share when I actually finish Doom Patrol and the Invisibles, but suffice to say for now I share your m ambivalence about the Simpsons, and really that whole style of comedy. It is a mistake to only read the show as nihilist, but the particular brand of middlebrow nihilism it expounded when not being sentimental has been enormously corrosive. I suspect it all goes back to Pynchon, or at least a kind of lazy misreading of what’s going on in those early Pynchon novels. (I’m tempted to say that the entire middlebrow read of literary pomo as a bunch of sniggering male nihilists is wrong as well, although I frankly don’t have the education or quite the breadth of reading to make that pronouncement in any authoritative way) There’s a way that postmodernism should have been and I think could and can still be freeing, can offer us avenues of escape from the repetition of immemorial tradition or the totalizing machine eye of modernisms old and new, but not like that, not when all there is is a couch and a television set to mock at the end of the world.

I think the key to Pynchon, Morrison, and The Simpsons is the way the nihilism comes packaged with the sentimentalism, each incomplete without the other, the two extremes of an exclusively extreme artistic experience. These works lack the middle range of thought-feeling: the affectionate rather than corrosive irony with which one customarily handles the inexorable contingency of one's nonetheless absolute commitments. There are hints of this bifurcation earlier, though, in basically everything you could call proto-postmodern in the tradition, from Chaucer to Sterne to Dickens to Joyce. We seem to have some perennial problem integrating thought and feeling, exacerbated by an artist's heightened awareness of rhetoric or medium. Under the influence of this hyper-awareness, everything, including love and death, begins to look already like a dated quotation or picture of itself. With the last century's unprecedented expansion of media, this condition has become much more universal (as you say "middlebrow"), disqualifying outright the openly passionate or wisdom-seeking work. The disqualification strands the sincere work in the realm of kitsch, where it lacks the inherent non-cynical irony-as-polysemy attaching to all literature qua literature. Hard Times becomes The Simpsons; Jane Eyre becomes Twilight. Many older writers successfully negotiated their work through the problem and out to the other shore in various ways—DeLillo's treating the surface of the spectacle from TV screen to supermarket as no less numinous than a cathedral, for example, or Ishiguro's use of popular genre tropes (detective, clone, dragon, robot) with unsmirking decorum and sincerity—but for the 60-and-under set, Wallace's death in the labyrinth seems sadly emblematic.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gothic Literature

The key characteristics of Gothic literature includes: the threat of supernatural events and the theme of the past (e.g castles and old run-down buildings used in the setting of the book). Usually Gothic stories serve as a metaphorical expression for social or psychological conflicts and in the 19th century many texts mentioned demons/ demonic possessions and ghosts or evil spirits. This style of literature became more widely used by writers in the 1780's however, by the Victorian era, the genre had stopped being the most dominant in England and was replaced by historical fiction. Gothic short stories still continued to be popular as they were still getting published in penny dreadfuls, one of the most influential author of this period was American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

Some examples of Gothic literature are: "Dracula" (1897) by Bram Stoker, "Frankenstein" (1818) by Mary Shelly, "Great Expectations" (1861) by Charles Dickens, "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843) by Edgar Allan Poe and "The strange case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde" (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Over time, Gothic themes have been translated into other modern medias including TV shows, games and even music, meaning the influence of Gothic fiction never truly ended after the 19th century but was just adapted to be used today in modern society, ultimately keeping the original characteristics and values that make it so iconic.

0 notes

Text

My Hypothetical Bookshelves

Since y’all are clearly never going to see a real picture of my messy-ass / overstuffed / entirely disorganized shelves, what if I showed you my work-in-progress list of hypothetical organizational categories I would make if I had as many spare rooms and shelves as I needed for what I currently own.

Small Books

Mostly vintage Scholastics (the mass-market Tab editions), a handful of mass-market adult fiction, a few gift books -- though I supposed I’d actually move the latter wherever I had small bits of shelf space. Or maybe I have enough of them for a whole shelf?

YA

Self-explanatory, my YA from 2000-today as roughly mocked up in a previous post (90% contemporary, occasional horror/thriller or historical mixed in). Might split by hardcover vs. paperback, or sequester the ex-library discards I don’t want to take the wrapping & stickers off of, on their own shelf.

Retro Teen

For my older teen books, like 70s to 2000. They just Look Different, uniformly skinnier and, in the case of the paperbacks, typically more mass-market sized.

My handful of vintage adult books may be here too, based on their similar size.

Lynn Hall

She’s the author I own the most books from (23), so though they range from 60-page illustrated children’s mysteries to teen fiction plus an adult novel, I think I would like to display the collection all in one special section, increasing by age range.

Marguerite Henry

She comes second, so I think I’d like to do the same, with my prized hardcovers first and then paperbacks, plus all the horse books together and then the others.

Vintage Children’s & Teen Books

Separated by content: wildlife; dogs; horses**; then general teen and other non-animal-centric ones.

**but maybe ALL the horse and dog books should be in their own sections regardless of era...? I do in fact have a few (even several) modern ones. dilemmaaaa!

Children’s / Middle Grade Hardcover

For the real nice-looking modern ones.

Apple/Troll/Yearling/Scholastic Paperbacks

The most uniform shelf! From 80s-today, by the edition publication date if not the original.

+ Ideally I’d put these near the bottom, and then on the actual bottom shelf, have some of those cloth shelf bins to stack my children’s series books in. I don’t feel like those really need to be on display standing up even with unlimited space; I prefer the idea of them nestled in stacks inside cubes with just an identifying label on the front.

Picture Books

Fancy hardcovers with dust jackets, floppy paperbacks, and Little Golden Books. A few oversized ones like Animalia and A Year at Maple Hill Farm would have to go live with the Tall Nonfiction like they do now.

Adult Fiction

Mostly contemporary/women’s fiction/romance; a handful of thrillers and historical, but overall I don’t think I have enough of them to separate this further by genre (and by “not enough” I mean I probably have less than 60 total). [edit: false! 75 exactly. excluding the mass markets and classics and the vintage ones, anyway]

Classics (depending on size/style…)

Jane Austen collection

Jane Eyre & Wuthering Heights

Scarlet Letter

Frankenstein

Little Women

House of Mirth

sweet I think those are all the classics I own (Black Beauty goes w/ the vintage horse books)

edit: nope forgot about the 3 Dickens books from college. dang, I was doing so well on owning only classics by or about women

Fantasy

Harry Potter (OG hardcovers and the 3-book supplemental library), Twilight (paperbacks), Miss Peregrine, Inkheart trilogy, and Tamora Pierce’s books... I think that’s all? Oh no wait, Land of Stories! and Fire Bringer proudly being my one standalone, besides a couple of mass markets that would go with their own kind. Speaking of...

TV Tie-In Novels

Doctor Who; X-Files; The O.C.; Glee; and any CSI-verse novels if I find the few that were memorable. Would consider putting the nonfiction TV stuff on the same shelf.

Memoirs

Of people (mostly celebrities or veterinarians), then pets

Small Coffee Table Books - longer than they are tall

An eclectic mix of travel books, photo essay books, the Grffin & Sabine series; I actually should collect these for a photo op because it’s such a hodgepodge.

Oh man, somewhere in here I’d need to designate a space for all my pretty blank books/journals, too. Most of which have nothing written in them. But they’d look nice.

Nonfiction: Other

Subdivided into the following categories, and separated onto at least two shelves to accommodate normal sized books vs. the VERY TALL/HEAVY ones (i.e. my various horse & dog breed/care encyclopedias)

Horses

Dogs

Cats

Wildlife

TV/Film

Fashion

Organizing (we stan irony)

Home Decor/Architecture

Yearbooks

and maybe just for fun if I had a wild amount of space, the incomplete set of 1950s World Book encyclopedias from my dad’s childhood that I grew up fascinated by and still adore for their beautiful illustrations

0 notes

Note

Ok, I'll bite. What *is* the difference between Bridgerton and Jane Austen in relationship to their skirts?

Oh! Not in their costuming, just in their general *waves hands* everything. It's a comment I see a lot about Bridgerton: "Well, it's not much like Austen, is it?"

That's because there are 200 years of literary history between the two, and they have not been empty!

This ended up being 1.5k words, but when I put stuff under a readmore, people don't actually read it and then just yell at me because of a misread of the 1/10th of the post they did read. Press j to skip or get ready to do a lot of scrolling (It takes four generous flicks to get past on my iPhone).

First I'll say my perspective on this is hugely shaped by Sherwood Smith, who has done a lot of research on silver fork novels and the way the Regency has been remembered in the romance genre.

The Regency and Napoleonic eras stretch from basically the 1790s to 1820, and after that, it was hard to ignore the amount of social change happening in Britain and Europe. The real watershed moment is the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, where 60,000 working-class people protesting for political change were attacked by a militia. The issues of poverty, class, industrialization, and social change are inescapable, and we end up with things like the 1832 Reform Act and 1834 Poor Law.

This is why later novelists, like Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, are so concerned with the experiences of the urban poor. Gaskell's North and South has been accurately described as "Pride and Prejudice for socialists."

So almost as soon as it ended, people started to look back and mythologize the Regency as a halcyon era, back when rich people could just live their rich lives and fret about "only" having three hundred pounds a year to live on. Back when London society was the domain of hereditary landowners, when you weren't constantly meeting with jumped-up industrialists and colonials.

Jane Austen is kind of perfect for this because she comes at the very end of the long eighteenth century, and her novels show hints of the tremors that are about to completely reshape England, but still comfortably sit in the old world. ("The Musgroves, like their houses, were in a state of alteration, perhaps of improvement. The father and mother were in the old English style, and the young people in the new. Mr and Mrs Musgrove were a very good sort of people; friendly and hospitable, not much educated, and not at all elegant. Their children had more modern minds and manners.")

Sherwood Smith covers the writers who birthed the Silver Fork genre in detail, but there's one name that stands out in its history more than any other: Georgette Heyer.

Georgette Heyer basically single-handedly established the Regency Romance as we know it today. Between 1935 and 1972, she published 26 novels set in a meticulously researched version of London of the late 18th and early 19th century. She took Silver Fork settings and characters and turned them into a highly recognizable set of tropes, conventions, and types. (As Sherwood points out, her fictional Regency England isn't actually very similar to the period as it really happened; it's like Arthurian Camelot, a mythical confection with a dash of truth for zest.)

Regency Romance is an escapist genre in which a happy, prosperous married life is an attainable prize that will solve everything for you. Georgette Heyer's novels are bright, sparkling, delightful romps through a beautiful and exotic world. Her female characters have spirit and vivacity, and are allowed to have flaws and make mistakes without being puritanically punished for them. Her romances have real unique sparks to them. She's able to write a formula over and over without it becoming dull.

And.... well. The essay that introduced me to Heyer still, in my opinion, says it best:

Here's the thing about Georgette Heyer: she hates you. Or, okay, she doesn't hate you, exactly. It's just that unless you are white, English, and upper class (and hale, and hearty, and straight, and and and), she thinks you are a lesser being.

[...W]ith Heyer, I knew where I stood: somewhere way below the bottom rung of humanity. Along with everyone else in the world except Prince William and four of his friends from Eton, which really took away the sting.

But my point is: if you are not that white British upper-class person of good stock and hearty bluffness and a large country estate, the only question for you is which book will contain a grimly bigoted caricature of you featuring every single stereotyped trait ever associated with your particular group. (You have to decide for yourself if really wonderful female characters and great writing are worth the rest of it.)

So Heyer created the genre, but she exacerbated the flaw that was always at the heart of fiction about the Regency, was that its appeal was not having to deal with the inherent rot of the British aristocracy. I think part of why it's such a popular genre in North America specifically is that we often don't know much British history, so we can focus more on the perfume and less on the dank odor it's hiding.

And like, escapism is not a bad thing. Romance writers as a community have sat down and said: We are an escapist genre. The Romance Writers of America, one of the biggest author associations out there, back when they were good, have foundationally said: "Two basic elements comprise every romance novel: a central love story and an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending." A strong part of the community argue that publishing in the genre is a "contract" between author and reader: If it's marketed as a romance book, there's a Happily Ever After. If there's no Happily Ever After, it's not romance.

It's important for people to be able to take a break from the stresses of their lives and do things that are enjoyable. But the big question the romance genre in particular has to deal with is, who should be allowed to escape? Is it really "escapist" if only white, straight, upper class, able-bodied thin cis people get to escape into it? In historical romance, this is especially an issue for POC and LGBTQ+ people. It's taken a lot of work, in a genre dominated by the Georgette Heyers of the world, to try to hew out the space for optimistic romances for people of colour or LGBTQ+ people. These are minority groups that deal with a literally damaging amount of stress in real lives; they are in especial need of sources of comfort, refuge, community, and encouragement. For brief introductions to the issue, I can give you Talia Hibbert on race, and KJ Charles on LGBTQ+ issues.

Up until the 1990s, the romance genre evolved slowly. It did evolve; Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan's Beyond Heaving Bosoms charts the demise of the "bodice-ripper" genre as it became more acceptable for women to have and enjoy sex. The historical romance genre became more accommodating to non-aristocratic heroines, or ones that weren't thin or conventionally pretty. The first Bridgerton book, The Duke and I, was published in 2000, and has that kind of vibe: Its characters are all white but not all of them are aristocrats, its heroines are frequently not conventionally beautiful and occasionally plump, and its cultivation to modern sensibility is reflected in its titles, which reference popular media of today.

This is just my impression, but I think that while traditional mainstream publishing was beginning to diversify in the 1990s, the Internet was what really made diverse romance take off. Readers, reviewers, and authors could talk more freely on the internet, which allowed books to become unlikely successes even if their publishers didn't promote them very much. Then e-publishing meant that authors could market directly to their readers without the filter of a publishing house, and things exploded. Indie ebooks proved that there was a huge untapped market.

One of my favourite books, Zen Cho's Sorcerer to the Crown, is an example of what historical romance is like today; it's a direct callback and reclamation of Georgette Heyer, with a dash of "Fuck you and all your prejudices" on top of it. It fearlessly weaves magic into a classic Heyer plot, maintaining the essential structure while putting power into the hands of people of colour and non-Western cultures, enjoying the delights of London society while pointing out and dodging around the rot. It doesn't erase the ugliness, but imagines a Britain that is made better because its poor, its immigrants, its people of colour, and the foreign countries it interacts with have more power to make their voices heard and to enforce their wills. Another book I've loved that does the same thing is Courtney Milan's The Duke Who Didn't.

So then... Bridgerton the TV show is trying to take a book series with a very middle-of-the-road approach to diversity, differing from Heyer but not really critiquing her, and giving it a facelift to bring it up to date.

So to be honest, although it's set in the same time period as Austen, it's not in the least her literary successor. It's infinitely more "about" the past 30 years of conversation and art in the romance genre than it is about books written 200 years ago.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Book Asks (I'm looking for new books ♥): 4, 11, 39, 58, 60

Thank you!

4 - what is your favorite book this year - gonna interpret it as “What’s my favorite book I read this year” for inability to form preferences reason - and it’s def Lolita (V. Nakobov). I had read it before, but in Italian and as a teenager so there’s a lot that went over my head in term of style, of the intricacies of the unreliable narration and of what an hauntingly tragic character Dolly actually is beyond all the narration to make her look like the most awful girl in the world.

11 Favorite authors - In term of “people from whom I really really liked more than one book” - classics Dickens, Doyle, Dostojevskij, Agatha Christie. Modern Tracy Chevalier, Bianca Pitzorno, Khaled Hosseini, GRRM

39 Favourite book to movie/TV show adaptation? - Mhhh. This is a bit rough as I generally really dislike these (and I’m obviously not counting plays so Zeffirelli is out). Idk if The Breadwinner counts since it’s animated but I really did love it in spite of all the liberties it took.

58 A book that emotionally wrecked you? - ooooh ahah. Well most recently A Clash of Kings, that can always be trusted for emotional wreckage

60 - Mhhh, random recs of imho underrated books by the Tumblr community that would be right up its alley:

- An unsuitable job for a woman (P.D James) - Lovely murder mystery with a very interesting female detective, a dark academia flavor, lots of ethical implication and a really nice coming of age/self discovery path

- The Pillars of Earth (Ken Follett) - historical fiction about the power of devotion and belief, involves family drama and political intrigue from all social classes and some really nice competence porn from people who can do their jobs really well

- Graceling (Kristin Cashore) - loosely connected fantasy trilogy that joins three quite different genres (Graceling is a spy/adventure novel that’s like a Sarah J Maas book was well written and had healthy enemies to lovers romance, Fire is high/epic fantasy, Bitterblue is essentially a mystery novel) in the same worldbuilding and with the same common themes of healing, rebirth and self discovery. Really nice disability rep

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Now and Then’ - current state of play

My film is a re-imagining of the site of Brighton General Hospital next to my home. Until around 70 years ago, a workhouse operated on the site (for details, see: Gardner, J, (2012) A History of the Brighton Workhouses). Aspects of the austere workhouse are still evident on the site today. I began to think about the stories of the residents of the workhouse – what did they have to endure? With this in mind, I bought the above book by a local author about the history of workhouses in Brighton.

I have always been fascinated by the idea that traumatic events in a particular location can be recorded and replayed at a later time in history and that this might be a basis for ghosts and hauntings – for example, in the blockbuster, Poltergeist, and the BBC drama from the 1970’s The Stone Tapes (Sasdy, 1972). This is one of the key concepts behind the film.

After a lot of thought, I settled on the story of the workhouse being told by a single woman, Agatha, whose infant child was taken from her illegally and sold to a rich couple living in Brighton. This is a variation on the common Victorian practice of unmarried women being compelled to give their children to a foundling home.

The film starts with Aggie telling her story in largely neutral terms and comparing the workhouse and the site’s positive use today as a hospital, but it climaxes with Aggie screaming with the loss of her child, and we see that she is a tormented spectre.The film ends with her anguish fading into a sign on the present site, promoting a nursery for infant children.

The film will be around 5-6 minutes long and will consist of edited original footage taken on the site in the present day. The film will be treated with video effects to alter the pacing, colour and atmosphere of the original footage. I have asked for a drama-trained friend to narrate the film as Aggie and will be using original and library sound effects and music motifs, or possibly drones to punctuate the soundtrack.

Now and Then – influences from other artists

1. Brian Percival - About a Girl

Female voice-over revealing a terrifying truth about motherhood at the end of the film. This film gives a cold dead feeling inside from the casual yet downcast demeanor as the leading character talks about her dysfunctional life and especially the ending, where the girl is revealed to have secretly miscarried a baby and we see her dump it into the canal (“I’ve become good at hiding things”). Both my film and About A Girl attempt to humanise the female main character outside of their tragedies.

2. Tobe Hooper - director of Poltergeist

Paranormal activity centred around past events and the presence of aggrieved spirits. This was a film that made an impact on me from its non-stop tension, even before the presence of the supernatural becomes apparent. Tobe Hooper, ever since creating The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) has achieved many awards, and after this film, it is easy to see why. It also has a similar plot to my initial idea for my film - where a great wrong done in the past creates a ‘haunting’ by aggrieved spirit(s)..

3. Peter Sasdy – Director of The Stone Tape (1972)

The original idea from the film was stones “recording” traumatic events from the past. While the current draft has drifted away from this concept, it still lives on with how Agatha remembers everything about the past as if she died yesterday, despite the superficial veneer of the current day hospital. However, Agatha is a real soul though in my film.

4. David Lynch - Eraserhead, The Elephant Man

His black and white films – particularly The Elephant Man

In the latter, view of Victorian England shot in black and white featuring cruelty and time-specific sounds, sights and atmospheres.

The film always seems to have a sense of foreboding, even when the scene is uneventful, and with a deeply engaging soundtrack. Eraserhead will always always be an influence due to its deliberate disturbing monochrome style, investigation of altered perception and the anxieties of parenthood.

5. James Gardener- Author of: A Complete History Of Brighton Workhouses

A detailed and easy-to-understand book centred around the original workhouse in my area. It includes the Brighton General Hospital Site. It helped give a real-life grounding to my supernatural tale.

6. Richard Boden - director of the Blackadder series 4 finale, Goodbyeee

The series as a whole has very little to do with my film, but this is a powerful episode whose fade-out ending and closing-sound inspired the cross-dissolve effects and soundscape in my film - coincidentally both are centered with the cruelty of the past and atmospheric sound. Present and past merge at this point. One of the most popular scenes in TV drama/comedy and understandably so too.

7. Piotr Obal – various films and still images

Obal is an independent artist who works with art, music and still photography. Occasionally, he teaches youths how to work at the computer like me (!) when he was helping out with an arts award I was studying for. Below is one of his images that has been an influence on me and the film. I love his Photoshop collages and the wonderful images he posts from his native Poland.

Work by Piotr Obal

8. Nalini Malani- for her immersive installations, ‘disgraced’ women under partiarchy, history and mythology, miscarriages of justice.

I found out about Malini when I was writing my essay on her work in the Diversity module: what started off as just finding out about an artist for the sake of my writing became a long-lasting admiration and inspiration from an artist who not only knows where she is coming from (from her upbringing hugely affected by India and Pakistan’s partition) but willingly sticks her neck out for those oppressed by society and history, and confidently shows her creations to the world. A particularly relevant aspect of her work is her use of the supernatural and mythology stories and myths to highlight aspects of women’s oppression throughout history.

9. Chris Butler- director of ParaNorman

A key influence, supposedly aimed at children, I used the same of the spectre in this moving animation, and I was influenced by its themes about the cruelties of humanity and how we “moved on”. The spectre is a ghost of a falsely accused of being a ‘witch’ who wreaks her revenge on those who persecuted her.

It was also a strong influence that is more powerful at its climax and twist. In-depth look at how prejudice destroys lives that are never regained - even death provides no relief. Butler is a part of Studio Laika, creating animated films that go beyond the norm.

10. Jacqueline Wilson - the writer of the Hetty Feather trilogy and other such Victorian novels such as Clover Moon.

A part of Jacqueline’s writings is her commentary about how unjust the past could be compared to today: even though her protagonists speak in ways that were customary to Victorians, she keeps them relatable the same way she keeps her modern-day protagonists relatable. The writing style of her books inspired certain characteristics of Agatha’s narration, because it was easy to understand yet engaging.

11. David Lean - Director of Great Expectations (1946)

This film, based on the Dickens book, also brought to mind the cruel period of the Victorian era, and the acting and emotions continued that spirit and my inspiration around my project. I love that it is black and white as well as dialog-centred - I particularly like the formal style of speech - even to express negative emotions- for example:

“Let me point out the topic that in London it is not the custom to put the knife in the mouth for fear of accidents. It's scarcely worth mentioning, Only it's as well to do as others do”.

Miss Havisham, an almost ghostly older woman, in a similar way to Agatha cannot move beyond the terrible wrong done to her - she was left at the alter and devoted her life to training her adopted daughter, Estella, to get revenge on men.I use s similar obsessive, sing-minded hatred to motivate Agatha.

12. Sunset Boulevard (1950)

This film involve a man becoming the object of affection of a former silent movie star, Norma Desmond who overtake his life little by little until she kills him. Norma suffered with the times when silent movies went out of fashion and she is unable to move on, alone in her great house: people told Norma that she had no value and it had an impact on her psyche. She loses all sanity when arrested for killing Joe Gillis as she believes she is back in show business.

The film also explores facades; Norma may live a glamorous if not lonely life, but her mental state torments her, like Aggie has with hers as she wanders around the hospital site driven ‘mad’ with grief and anger.

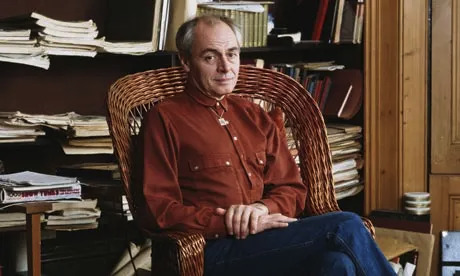

13. R D Laing: ‘anti-psychiatrist’

'Here was someone explaining madness, showing how the fragmentation of the person was an intelligible response to an intolerable pressure”

Quote from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/25/rd-laing-aaron-esterson-mental-illness

In discussing the concept of my film with a member of my family, I was directed to the psychiatrist/anti-psychiatrist, RD Laing. In the 1960’s and early 1970’s Laing wrote about how a person’s so-called ‘mad’ behaviour was in fact intelligible when their entire situation and experience was taken into account. He and other writers (like David Cooper) talked about the concept of the ‘double-bind’ where a person’s opportunity to make a decision to resolve the way they were being treated was blocked – perhaps by a member of their family saying that it was not in their personality to be assertive or angry.

This reminded me very much of Agatha; she tries to express her outrage at the great wrong done to her, but she is judged as unworthy and undeserving, so the wrong is seen as justified and her punishment for being the ‘low-life’ who would have a child and have to live in a workhouse. It is circular – she is treated badly because she deserves to be treated badly and so this means that her hatred and insanity brings the great wrong up herself.

Laing is largely forgotten today, but his ideas resonate with certain ideas in feminism and anti-racism. ‘Gaslighting’ is everywhere, both back then and now.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NnBonXPLJM

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acts of Translation

Late in February 2021, I was walking through the Long Island Pine Barrens, along the beginning of the Paumanok Trail. The snow-covered path was marked by the patterned boot tracks of other hikers (only two or three at the most) and the cloven hoof-marks of deer. The sky above the trees was pale blue, tinged with gray. The air was cool, crisp, dry. With each step, my boots compacted the icy slush and sometimes my boot would shift, sliding on the heavy, dense snowpack so that I’d have to compensate with a movement of my upper body and arms to keep my balance and to prevent myself from slipping.

The fourth branch of Jacques Roubaud’s “the great fire of London”, a volume called Poésie: (récit) — I prefer the French title since Poetry: (a story) is less poetic and loses a sense of meaning that I think should be there, poésie to my ear implies a movement that is lost in the more static English word, poetry, and récit (and perhaps this is peculiar to me and has nothing to do with actual French) suggests narration closer to that when a storyteller speaks to a listener who receives the récit and so completes the action, a story doesn’t necessarily require a reader — begins with the Narrator (Roubaud) moving through space, in this case, the space is urban, the streets Paris.

Early in December 1994, I was walking in Paris. The sky was gray, low, the air humid, warm.

For walking in Paris, I wear a blue K-way jacket, and a cap, also blue. The K-way was a gift, not something I’d picked out. It was light, blue, waterproof, costly.

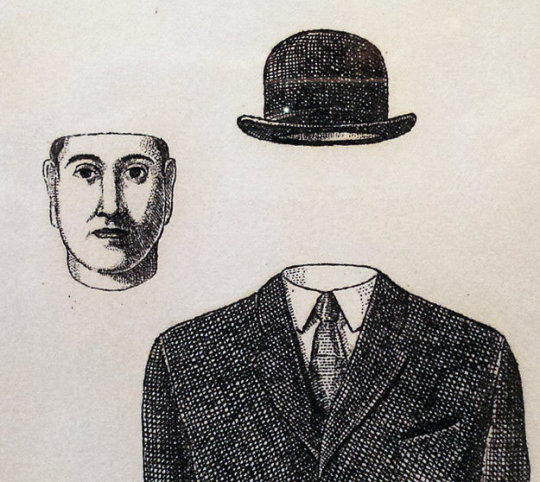

For walking in the woods, I wear an olive green jacket made by Patagonia that zips up the front and has a little pocket over the left breast where I can store my phone for easy access. Around my neck, I wear my “Doctor Who scarf” knitted by my mother. (The scarf isn’t a replica of any of the long scarves worn by the Fourth Doctor, played by actor Tom Baker, but a spirited recreation of the sort that anyone familiar with the various scarves featured in Season 12 through 17 of the TV show would immediately recognize.) On my head I wear a black bowler hat I purchased at the museum shop of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2018 when I took my mother and son to the Magritte exhibit. (The next summer, I would take my wife and son to Brussels to tour the permanent Magritte exhibit at the Musée de Beaux Arts. The study of Magritte’s art and writing is a principal concern of my Project.) The clerk at the shop said this style of bowler hat is the exact same one worn by René Magritte when he was alive. So it should be no surprise that I’m pleased with it and wear it every opportunity I get, and especially when I’m out on my daily walk.

Before the pandemic, I walked every afternoon through the pine barrens. This was easy enough since the office where I perform my paid work (not at all literary) is located in the middle of the pine barrens. There are a network of trails that lead through the woods that are immediately accessible from the back door of the building where I work. A year ago, my office was closed, so that I now work from home. Now my afternoon walks (usually) are taken along the streets in the neighborhood where I live in the village of Long Neck. I’ve become a familiar sight in the neighborhood as the man in the bowler hat. My neighbors wave to me and sometimes will view my unusual headwear as an occasion for conversation. What kind of hat is that? asked one neighbor. Another fellow walker assumed I’m a fan of Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, a novel by Anthony Burgess. I’m more a fan of the book than I am a fan of the movie, but my bowler hat is most deliberately a nod to Magritte and not to Alex and his three droogs. Throughout the pandemic, Magritte and his art has been my life line.

On his walks in Paris, Roubaud doesn’t wear a bowler — his cap is of a different sort.

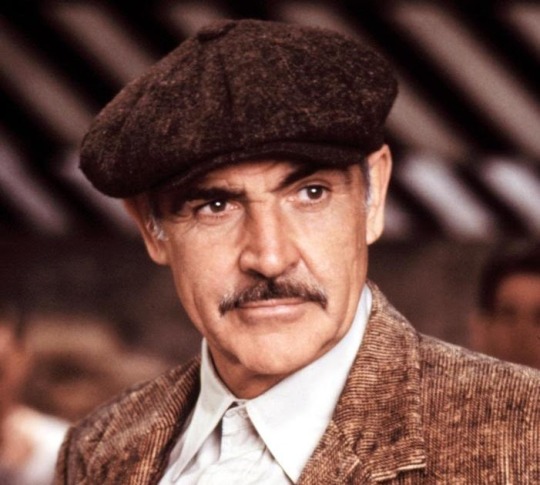

I bought the cap in New York, at J.J. Hat Center, at the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street. It’s a hat made in Scotland and the salesperson assured me that it was the same exact style of cap worn by Sean Connery in the film The Untouchables. It’s no surprise that I’m happy with it.

After I’m vaccinated and I feel like taking the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station again, maybe I’ll go to the J.J. Hat Center myself and shop for a hat. Although according to “the internet” J.J. Hat Center is now located at 310 Fifth Ave (between 31st & 32nd), not far from Penn at all. If/when I do go in to the city, I’ll want to pay a visit to the Fountain Pen Hospital. A man can never have too many hats or too many fountain pens.

I could go along in this vein for quite some time, this leisurely stroll through Roubaud’s Poésie: (récit) allowing his text to guide my own thoughts, reveries, musings, etc. The resulting text would function as a companion text. I’m walking along with Roubaud in Paris as he moves from the National Library, past familiar restaurants, along familiar streets…

I passed between the tops or periscopes of the licorice icebergs of the Buren columns, making sure not to slip on their outgrowths/extensions [? the French word is excroissances, but it’s not obvious to me what these outgrowths or extensions might be], on the damp grills, slimy, soaped with crushed beige leaves. And I made it through with no accidents to Place Colette, on the right side of the Théâtre-Français. This route was well known to me.

...but Roubaud himself is not walking with me, only his text, or perhaps he is with me as an invented copy of an imaginary Roubaud that I carry within myself as I read and as I walk along the snow-covered Paumanok Trail thinking of his book, or books (one book in seven volumes called collectively “the great fire of London”).

I read the first two and a half branches (the first three volumes to be translated into English), starting with Branch One: Destruction in the fall of 2018. Without really intending to, I wrote a little book of jottings while reading Roubaud’s novel. I called my little book, In the Labyrinth of Forking Paths, since “the great fire of London” is “a story with interpolations and bifurcations” with actual links indicating different narrative paths the reader can take during their wandering reading. I was reminded (though only a little) of the choose-your-own-adventure books (published by Bantam) I read when I was a kid. One of my early attempts at writing fiction was a “literary” choose-your-own-adventure called (imaginatively enough) Into the Labyrinth (a slight variation on a title of one of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s novels, Dans le labyrinthe, with whose hyper-descriptive nouveau roman style I’d become bewitched, a style ideally suited to such text adventures). (I published my Into the Labyrinth as an interactive fiction designed for a media platform that worked only on those early generation iPods. I have no idea if anyone ever read/played my interactive fiction even though according to the app, mine was the most downloaded story. It was certainly the longest.) I won’t claim that I have been waiting for the remaining four volumes to be translated into English. In fact, I felt a certain level of contentment with the artificial truncation of the novel — I had read all that I could, all that was available in English, so now I could move on to other things, like reading the works of Miklós Szentkuthy. Procuring and reading the rest of “the great fire of London” wasn’t a tempting prospect until Anthony, author of the blog, Time’s Flow, mentioned that he’d purchased the remaining volumes in French and would be making an attempt to read them. That was all it took. If Anthony was going to do it, then so would I. I ordered copies from a bookseller in France and they arrived last Friday in the post. So when did I get the idea to translate these remaining four volumes into English myself? Was it a serious idea or just another of my fanciful projects? Project 7139: translated two thousand pages of Jacques Roubaud’s “the great fire of London” into English. (For the record, I’m currently working on Project 3 which I started twenty years ago. Project 4 is “write a masterpiece that will establish my literary reputation.” That one might take awhile.) Certainly, I would read these other branches. Or would I? My track record for finishing big projects is not stellar. (The first time I read Proust, it took me ten years.)

While walking in the snow in the pine barrens, I thought about why I was being pulled back into Roubaud’s book. What was it about his very long prose that attracted me? Was this a momentary literary crush or had I fallen for “the great fire of London”? If this were a romance, you could say that Roubaud and I met in the fall of 2018 and spent some time together, mostly walking. We shared our mutual interests, talking about poetry, literature, and mathematics. I learned a great deal about haikai (haiku and haibun), gained a new appreciation of the works of Charles Dickens, and was introduced to Nicholas Bourbaki, and then resumed my own mathematical studies after a hiatus of twenty years, this time beginning with set theory and topology. And then it was over. He had to go. We parted ways.

Then two and half years later, Roubaud pops up again at a party hosted by a friend, this time we’re speaking French — my French is better now, so it’s much easier for us to talk and now I feel something different than I did before. We’re making a real connection. I can feel it. And Roubaud seems somehow changed. When we first met, I was the one who was paying attention to Roubaud, accompanying a new master, and learning new things. Now, this new Roubaud, this French-speaking Roubaud is interested in me, keeps asking me questions, asking for my opinion. Then it dawns on me. Roubaud has chosen me. You’re the one, he says. I’ve picked you.

Of course, this isn’t an exclusive relationship. Such is the way with authors and their books. Readers must share the objects of their affection, but still it feels different when a book chooses you rather than you choosing it.

I’m choosing you. I’m ready whenever you are. Shall we begin?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Bolin, The Ethical Dilemma of Highbrow True Crime, Vulture (August 1, 2018)

The “true-crime boom” of the mid- to late 2010s is a strange pop-culture phenomenon, given that it is not so much a new type of programming as an acknowledgement of a centuries-long obsession: People love true stories about murder and other brands of brutality and grift, and they have gorged on them particularly since the beginning of modern journalism. The serial fiction of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins was influenced by the British public’s obsessive tracking of sensational true-crime cases in daily papers, and since then, we have hoarded gory details in tabloids and pulp paperbacks and nightly news shows and Wikipedia articles and Reddit threads.

I don’t deny these stories have proliferated in the past five years. Since the secret is out — “Oh you love murder? Me too!” — entire TV networks, podcast genres, and countless limited-run docuseries have arisen to satisfy this rumbling hunger. It is tempting to call this true-crime boom new because of the prestige sheen of many of its artifacts — Serial and Dirty John and The Jinx and Wild, Wild Country are all conspicuously well made, with lovely visuals and strong reporting. They have subtle senses of theme and character, and they often feel professional, pensive, quiet — so far from vulgar or sensational.

But well-told stories about crime are not really new, and neither is their popularity. In Cold Blood is a classic of American literature and The Executioner’s Song won the Pulitzer; Errol Morris has used crime again and again in his documentaries to probe ideas like fame, desire, corruption, and justice. The new true-crime boom is more simply a matter of volume and shamelessness: the wide array of crime stories we can now openly indulge in, with conventions of the true-crime genre more emphatically repeated and codified, more creatively expanded and trespassed against. In 2016, after two critically acclaimed series about the O.J. Simpson trial, there was talk that the 1996 murder of Colorado 6-year-old JonBenét Ramsey would be the next case to get the same treatment. It was odd, hearing O.J.: Made in America, the epic and depressing account of race and celebrity that won the Academy Award for Best Documentary, discussed in the same breath with the half-dozen unnecessary TV specials dredging up the Ramsey case. Despite my avowed love of Dateline, I would not have watched these JonBenét specials had a magazine not paid me to, and suffice it to say they did very little either to solve the 20-year-old crime (ha!) or examine our collective obsession with it.

Clearly, the insight, production values, or cultural capital of its shiniest products are not what drives this new wave of crime stories. O.J.: Made in America happened to be great and the JonBenét specials happened to be terrible, but producers saw them as part of the same trend because they knew they would appeal to at least part of the same audience. I’ve been thinking a lot about these gaps between high and low, since there are people who consume all murder content indiscriminately, and another subset who only allow themselves to enjoy the “smart” kind. The difference between highbrow and lowbrow in the new true crime is often purely aesthetic. It is easier than ever for producers to create stories that look good and seem serious, especially because there are templates now for a style and voice that make horrifying stories go down easy and leave the viewer wanting more. But for these so-called prestige true-crime offerings, the question of ethics — of the potential to interfere in real criminal cases and real people’s lives — is even more important, precisely because they are taken seriously.

Like the sensational tone, disturbing, clinical detail, and authoritarian subtext that have long defined schlocky true crime as “trash,” the prestige true-crime subgenre has developed its own shorthand, a language to tell its audience they’re consuming something thoughtful, college-educated, public-radio influenced. In addition to slick and creative production, highbrow true crime focuses on character sketches instead of police procedure. “We’re public radio producers who are curious about why people do what they do,” Phoebe Judge, the host of the podcast Criminal, said. Judge has interviewed criminals (a bank robber, a marijuana brownie dealer), victims, and investigators, using crime as a very simple window into some of the most interesting and complicated lives on the planet.

Highbrow true crime is often explicitly about the piece’s creator, a meta-commentary about the process of researching and reporting such consequential stories. Serial’s Sarah Koenig and The Jinx’s Andrew Jarecki wrestle with their boundaries with the subjects (Adnan Syed and Robert Durst, respectively, both of whom have been tried for murder) and whether they believe them. They sift through evidence and reconstruct timelines as they try to create a coherent narrative from fragments.

I remember saying years ago that people who liked Serial should try watching Dateline, and my friend joked in reply, “Yeah, but Dateline isn’t hosted by my friend Sarah.” One reason for the first season of Serial’s insane success — it is still the most-downloaded podcast of all time — is the intimacy audiences felt with Koenig as she documented her investigation of a Baltimore teenager’s murder in real time, keeping us up to date on every vagary of evidence, every interview, every experiment. Like the figure of the detective in many mystery novels, the reporter stands in for the audience, mirroring and orchestrating our shifts in perspective, our cynicism and credulity, our theories, prejudices, frustrations, and breakthroughs.

This is what makes this style of true crime addictive, which is the adjective its makers most crave. The stance of the voyeur, the dispassionate observer, is thrilling without being emotionally taxing for the viewer, who watches from a safe remove. (This fact is subtly skewered in Gay Talese’s creepy 2017 Netflix documentary, Voyeur.) I’m not sure how much of my eye-rolling at the popularity of highbrow true crime has to do with my general distrust of prestige TV and Oscar-bait movies, which are usually designed to be enjoyed in the exact same way and for the exact same reasons as any other entertainment, but also to make the viewer feel good about themselves for watching. When I wrote earlier that there are viewers who consume all true crime, and those who only consume “smart” true crime, I thought, “And there must be some people who only like dumb true crime.” Then I realized that I am sort of one of them.

There are specimens of highbrow true crime that I love, Criminal and O.J.: Made in America among them, but I truly enjoy Dateline much more than I do Serial, which in my mind is tedious to the edge of pointlessness. I find myself perversely complaining that good true crime is no fun — as self-conscious as it may be, it will never be as entertaining as the Investigation Discovery network’s output, most of which is painfully serious. (The list of ID shows is one of the most amusing artifacts on the internet, including shows called Bride Killas, Momsters: Moms Who Murder, and Sex Sent Me to the Slammer.) Susan Sontag famously defined camp as “seriousness that fails,” and camp is obviously part of the appeal of a show called Sinister Ministers or Southern Fried Homicide. Network news magazine shows like Dateline and 48 Hours are somber and melodramatic, often literally starting voice-overs on their true-crime episodes with variations of “it was a dark and stormy night.” They trade in archetypes — the perfect father, the sweet girl with big dreams, the divorcee looking for a second chance — and stick to a predetermined narrative of the case they’re focusing on, unconcerned about accusations of bias. They are sentimental and yet utterly graphic, clinical in their depiction of brutal crimes.

It’s always talked around in discussions of why people like true crime: It is … funny? The comedy in horror movies seems like a given, but it is hardly permitted to say that you are amused by true disturbing stories, out of respect for victims. But in reducing victims and their families to stock characters, in exaggerating murderers to superhuman monsters, in valorizing police and forensic scientists as heroic Everymen, there is dark humor in how cheesy and misguided these pulpy shows are, how bad we are at talking about crime and drawing conclusions from it, how many ways we find to distance ourselves from the pain of victims and survivors, even when we think we are honoring them. (The jokey titles and tongue-in-cheek tone of some ID shows seem to indicate more awareness of the inherent humor, but in general, the channel’s programming is almost all derivative of network TV specials.) I’m not saying I’m proud of it, but in its obvious failures, I enjoy this brand of true crime more straightforwardly than its voyeuristic, documentary counterpart, which, in its dignified guise, has maybe only perfected a method of making us feel less gross about consuming real people’s pain for fun.

Crime stories also might be less risky when they are more stilted, more clinical. To be blunt, what makes a crime story less satisfying are often the ethical guidelines that help reporters avoid ruining people’s lives. With the popularity of the podcasts S-Town and Missing Richard Simmons, there were conversations about the ethics of appropriating another person’s story, particularly when they won’t (or can’t) participate in your version of it. The questions of ethics and appropriation are even heavier when stories intersect with their subjects’ criminal cases, because journalism has always had a reciprocal relationship with the justice system. Part of the exhilarating intimacy of the first season of Serial was Koenig’s speculation about people who never agreed to be part of the show, the theories and rabbit holes she went through, the risks she took to get answers. But there is a reason most reporters do all their research, then write their story. It is inappropriate, and potentially libelous, to let your readers in on every unverified theory about your subject that occurs to you, particularly when wondering about a private citizen’s innocence or guilt in a horrific crime.

Koenig’s off-the-cuff tone had other consequences, too, in the form of amateur sleuths on Reddit who tracked down people involved with the case, pored over court transcripts, and reviewed cellular tower evidence, forming a shadow army of investigators taking up what they saw as the gauntlet thrown down by the show. The journalist often takes on the stance of the professional amateur, a citizen providing information in the public interest and using the resources at hand to get answers. At times during the first season of Serial, Koenig’s methods are laughably amateurish, like when she drives from the victim’s high school to the scene of the crime, a Best Buy, to see if it was possible to do it in the stated timeline. She is able to do it, which means very little, since the crime occurred 15 years earlier. Because so many of her investigative tools were also ones available to listeners at home, some took that as an invitation to play along.

This blurred line between professional and amateur, reporter and private investigator, has plagued journalists since the dawn of modern crime reporting. In 1897, amid a frenzied rivalry between newspaper barons William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, true crime coverage was so popular that Hearst formed a group of reporters to investigate criminal cases called the “Murder Squad.” They wore badges and carried guns, forming essentially an extralegal police force who both assisted and muddled official investigations. Seeking to get a better story and sell more papers, it was common for reporters to trample crime scenes, plant evidence, and produce dubious witnesses whose accounts fit their preferred version of the case. And they were trying to get audiences hooked in very similar ways, by crowdsourcing information and encouraging readers to send in tips.

Of course the producers of Serial never did anything so questionable as the Murder Squad, though there are interesting parallels between the true-crime podcast and crime coverage in early daily newspapers. They were both innovations in the ways information was delivered to the public that sparked unexpectedly personal, participatory, and impassioned responses from their audiences. It’s tempting to say that we’ve come full circle, with a new true-crime boom that is victim to some of the same ethical pitfalls of the first one: Is crime journalism another industry deregulated by the anarchy of the internet? But as Michelle Dean wrote of Serial, “This is exactly the problem with doing journalism at all … You might think you are doing a simple crime podcast … and then you become a sensation, as Serial has, and the story falls to the mercy of the thousands, even millions, of bored and curious people on the internet.”

Simply by merit of their popularity, highbrow crime stories are often riskier than their lowbrow counterparts. Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker about the ways the makers of the Netflix series Making a Murderer, in their attempt to advocate for the convicted murderer Steven Avery, omit evidence that incriminates him and put forth an incoherent argument for his innocence. Advocacy and intervention are complicated actions for journalists to undertake, though they are not novel. Schulz points to a scene in Making a Murderer where a Dateline producer who is covering Avery is shown saying, “Right now murder is hot.” In this moment the creators of Making a Murderer are drawing a distinction between themselves and Dateline, as Schulz writes, implying that, “unlike traditional true-crime shows … their work is too intellectually serious to be thoughtless, too morally worthy to be cruel.” But they were not only trying to invalidate Avery’s conviction; they (like Dateline, but more effectively) were also creating an addictive product, a compelling story.

That is maybe what irks me the most about true crime with highbrow pretensions. It appeals to the same vices as traditional true crime, and often trades in the same melodrama and selective storytelling, but its consequences can be more extreme. Adnan Syed was granted a new trial after Serial brought attention to his case; Avery was denied his appeal, but people involved in his case have nevertheless been doxxed and threatened. I’ve come to believe that addictiveness and advocacy are rarely compatible. If they were, why would the creators of Making a Murderer have advocated for one white man, when the story of being victimized by a corrupt police force is common to so many people across the U.S., particularly people of color?

It does feel like a shame that so many resources are going to create slick, smart true crime that asks the wrong questions, focusing our energy on individual stories instead of the systemic problems they represent. But in truth, this is is probably a feature, not a bug. I suspect the new true-crime obsession has something to do with the massive, terrifying problems we face as a society: government corruption, mass violence, corporate greed, income inequality, police brutality, environmental degradation, human-rights violations. These are large-scale crimes whose resolutions, though not mysterious, are also not forthcoming. Focusing on one case, bearing down on its minutia and discovering who is to blame, serves as both an escape and a means of feeling in control, giving us an arena where justice is possible.

Skepticism about whether journalists appropriate their subjects’ stories, about high and low, and about why we enjoy the crime stories we do, all swirl through what I think of as the post–true-crime moment. Post–true crime is explicitly or implicity about the popularity of the new true-crime wave, questioning its place in our culture, and resisting or responding to its conventions. One interesting document of post–true crime is My Favorite Murder and other “comedy murder podcasts,” which, in retelling stories murder buffs have heard on one million Investigation Discovery shows, unpack the ham-fisted clichés of the true-crime genre. They show how these stories appeal to the most gruesome sides of our personalities and address the obvious but unspoken fact that true crime is entertainment, and often the kind that is as mindless as a sitcom. Even more cutting is the Netflix parody American Vandal, which both codifies and spoofs the conventions of the new highbrow true crime, roasting the genre’s earnest tone in its depiction of a Serial-like investigation of some lewd graffiti.

There is also the trend in the post–true-crime era of dramatizing famous crime stories, like in The Bling Ring; I, Tonya; and Ryan Murphy’s anthology series American Crime Story, all of which dwell not only on the stories of infamous crimes but also why they captured the public imagination. There is a camp element in these retellings, particularly when famous actors like John Travolta and Sarah Paulson are hamming it up in ridiculous wigs. But this self-consciousness often works to these projects’ advantage, allowing them to show heightened versions of the cultural moments that led to the most outsize tabloid crime stories. Many of these fictionalized versions take journalistic accounts as their source material, like Nancy Jo Sales’s reporting in Vanity Fair for The Bling Ring and ESPN’s documentary on Tonya Harding, The Price of Gold, for I, Tonya. This seems like a best-case scenario for prestige true crime to me: parsing famous cases from multiple angles and in multiple genres, trying to understand them both on the level of individual choices and cultural forces.

Perhaps the most significant contributions to post–true crime, though, are the recent wave of personal accounts about murder and crime: literary memoirs like Down City by Leah Carroll, Mean by Myriam Gurba, The Hot One by Carolyn Murnick, After the Eclipse by Sarah Perry, and We Are All Shipwrecks by Kelly Grey Carlisle all tell the stories of murder seen from close-up. (It is significant that all of these books are by women. Carroll, Perry, and Carlisle all write about their mothers’ murders, placing them in the tradition of James Ellroy’s great memoir My Dark Places, but without the tortured, fetish-y tone.) This is not a voyeuristic first person, and the reader can’t detach and find joy in procedure; we are finally confronted with the truth of lives upended by violence and grief. There’s also Ear Hustle, the brilliant podcast produced by the inmates of San Quentin State Prison. The makers of Ear Hustle sometimes contemplate the bad luck and bad decisions that led them to be incarcerated, but more often they discuss the concerns of daily life in prison, like food, sex, and how to make mascara from an inky page from a magazine. This is a crime podcast that is the opposite of sensational, addressing the systemic truth of crime and the justice system, in stories that are mundane, profound, and, yes, addictive.

#true crime#adnan syed#media#ethics#The Way We Live Now#culture#andrew jarecki#james ellroy#criminal justice#detective fiction

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

In many ways, the horrible wig was the best thing to happen to Harry Lloyd.

The shock of platinum blonde hair, slashed to a sensible bob at his shoulders like a high-fashion Legolas, was the coif that tied Lloyd’s indelible, insufferable Game of Thrones character together: Viserys Targaryen, the petulant narcissist whose play for the Iron Throne melts along with the rest of him under a pot of molten metal poured over his head, one of the show’s first and most iconic gruesome death scenes.

The splashy HBO production was the biggest job the young actor had ever landed, and as a character with an unmistakable, unforgettable look, to boot— the better to sear into TV fans’ consciousness.

Blessedly, that unmistakable, unforgettable look in no way actually resembled him, a then-27-year-old rising star with short, dark brown hair and alabaster complexion. He played one of the most memorable characters in recent TV history on possibly the last truly massive global TV phenomenon, yet, by the grace of a wig, he was still unrecognizable.

“I kind of loved that,” Lloyd tells The Daily Beast over Zoom from the loft study in his North London home. “And I kind of loved that he died. He had this lovely arc, and he still has his place in this enormous and infamous canon.”

Given how vivid that arc is in Thrones lore, it’s almost startling to remember that he was only on five episodes of the show.

“I had my go,” he says. “I got in early and I got out early. And he didn’t look like me, which, number one, is good because he is a little shit. And so I was happy to not have people throwing stuff at me in the streets. But number two, and I didn’t notice at the time, but it has since become the biggest show on TV. It doesn’t make me worry about being typecast so much.”

In the years since becoming a scalded puddle of boiling jewels and flesh, Lloyd has been able to shapeshift through an impressive résumé of prestige TV series and award-nominated films—Manhattan, Wolf Hall, Counterpart, Legion, The Theory of Everything—relieved of the kind of limitations actors who play little shits in garish white wigs on TV’s biggest show typically shoulder.

The occasion for our conversation is yet another transformation, as Bernard Marx in Brave New World, the splashy adaptation of Aldous Huxley’s 1932 dystopian sci-fi novel. The series is the marquee original offering for Wednesday’s launch of the new Peacock streaming service, casting Downton Abbey alum Jessica Brown Findlay and Han Solo himself, Alden Ehrenreich, alongside Lloyd in an updated take on the classic work.

Brave New World thwarts the idea of a restrictive, Orwellian dystopia with one in which society is instead forced into surrendering their inhibitions. “Welcome to New London,” a prologue explains. “We have three rules. No privacy. No family. No monogamy. Everyone is very happy.”

The new series boasts modernized flourishes when it comes to style—if there had been this much sex in Huxley’s book, we would have paid far more attention to it in high school—and sensibility; some of the problematically racist and misogynistic themes and plot points have been corrected.

Lloyd’s Bernard is an upper echelon member of society, called an Alpha-Plus, whose job is to maintain social order. Throughout the series, he experiences a crisis of conscience, an existential awakening at odds with the blissful stasis he’s meant to both control and enjoy.

If a narrow escape from typecasting and a career playing snooty, megalomaniacal manchildren has meant a diverse array of opportunity for Lloyd, then Brave New World marks more new territory: It’s his first outright leading role.

Lloyd had never read Huxley’s book before being cast, but was impressed by the ambition of the script, “almost like a mega tentpole movie in scale” but esoteric and satirical at the same time. “I was like, this has the whole package if they can shoot this, but I don’t think they can.”

It took one day on set for him to catch wise to the technical prowess at play. “I was like, wow, this really is a brave new world,” he says.

Don’t worry. He promptly scoffed at himself and rolled his eyes.

It is one of the best opening lines to a profile that I’ve read, from a 2011 feature on Lloyd that ran in Britain’s The Independent: “There was a time when Harry Lloyd worried that he was forever going to be typecast—as a woman.”

It was in reference to Lloyd’s days as a student at Eton College, where the young teen’s voice had not yet broken and he was cast as women in a slew of all-male Shakespeare productions.

Here we were prepping to engage with Lloyd about the perils of typecasting following his Thrones stint, ignorant of the fact that he had already confronted the issue decades earlier.

Lloyd laughs good-naturedly when the era of fake bras and bonnets is brought up.

“I hated it,” he says. Just when he had vowed never to agree to it again, in his last year at school he was asked to play Rosalind in As You Like It, by all counts a fantastic leading part. He nailed it, and earned raves. “At an all-boys boarding school, it took balls to put on tights, as it was.” A perfectly-earned smirk at his own joke follows.

The truth is that being typecast or pigeon-holed is a stressor that followed Lloyd, who grew up in London with parents who worked in the book industry. “Sometimes it’s just the face you have at a certain age…” he says.

His first major role came at age 15 in the BBC’s 1999 adaptation of David Copperfield, opposite Daniel Radcliffe. (Adding another fascinating layer to the trivia: Lloyd himself is the great-great-great grandson of Charles Dickens.) One of his first jobs after that was playing a bullying prefect in the series Goodbye, Mr. Chips.

“I guess that’s what I looked like, and I did that a couple of times,” he says. “Then I was like, I don’t really want to just be that guy. He’s a bit of a dick. And then I think next up I played the murderer in some procedural police thing, some young kid that’s gone sideways.”

Each time he felt a box starting to close its sides around him, he actively sought out something different. Having Great Expectations, in which he played Herbert Pocket, “the loveliest, most benign chap you’d ever meet,” air months after his Thrones debut was key. But he can’t refute that, with or without a platinum wig, there’s something about the way he looks that telegraphs a certain kind of sinister character.

“If I turn up in a murder thing, it’s often me who’s done it,” he says, grinning. “I don’t want to give anything away from the stuff I’ve been in. But I don’t know, there’s something about my face that is like, ‘He could do it.’”

After he had finished filming his part on Thrones and the series was about to come out, he was cast in the buzzy West End production of the Tony-winning play The Little Dog Laughed.

If you’re familiar with the work, a satire about Hollywood illusion (and delusion) in which an acerbic, big-wig agent crisis manages her rising-star client’s pesky “recurring case of homosexuality,” you understand why it’s a fairly hilarious, if sobering, project to be involved in just as an actor’s own fame and industry profile is about to skyrocket.

“Because I was about to be on Game of Thrones, I thought, this is the time for me to get an American agent,” he recalls. “And so the American agents, when they were in London, would come and see me in this play, which basically looks at agenting and their ways with quite a big, angry magnifying glass. They would come backstage and say, ‘Look, I am not like that…’” He laughs. “It was always quite a funny way to start the proceedings.”

Having starred in episodes of Dr. Who and played Charles Xavier in Legion, not to mention his connection to Thrones, Lloyd has had his taste of the particular brand of rabid, Comic-Con fandom. Though he prefers to classify himself as “adjacent-adjacent” to that world.

While there are certainly those who will know right away that he was a Targaryen, what he gets more of is a “Wait, how do I know you?” awkward conversation. “Genuinely, people are like, ‘Hey, did I go to school with you?’ I’m at that level of renown. You can’t quite place why you might recognize me.”

Asked how life under the coronavirus shutdown has been, Lloyd is very British about the months spent with his wife and their almost-2-year-old. “We’ve done alright,” he says. “We learned how to finally kind of plan our fridge. And now we know how to do our shopping tactically. We cooked some good stuff.”

For fear of sounding “solipsistic,” to use a word employed often in Brave New World, he identifies the extended time home with typical feelings actors have throughout their career.

“You have accelerated times in your life when things happen like a dream,” he says. “Things are so fast and our whole world’s rebuilt entirely every time you get a job. And then is the come-down and the fallout.”

He remembers that feeling from when he was doing plays: the energy and pace of putting on the show, and then a few weeks after it ends there’s a massive crash.

“It feels a bit like you’re in lockdown. You stare around on a Tuesday afternoon. You don’t want to watch anything. You don’t know what to do or who to call, and you kind of lose your style. There’s been a bit of that.”

Just when things got to the point that he felt like he might lose his mind, he was contracted to record an audiobook. So for a couple of days a week, he would sit up in his “sweatbox made out of duvets” and read Great Expectations aloud for Penguin. “That saved me for sure.”

On the subject of works by his great-great-great grandfather, Lloyd used to be at a loss for what to do when people brought it up. Often they would say, “Congratulations!” on the relation, as if he had accomplished something himself by being born into Charles Dickens’ lineage. “But these days, I’ll take it, I’ve decided. ‘Yeah, thank you so much.’ It’s a nice thing to celebrate.”

The 150th anniversary of Dickens’ death was in June. There had been plans for a commemoration ceremony at Westminster Abbey that, because of the shutdown, became a Zoom event instead.

“I don’t know how many people’s deaths get a 150th anniversary,” he says. “The fact that I have any kind of personal connection with that is very much secondary. But something that I’m very proud of.”

At risk of belaboring the point, we ask if working on any of the Dickens adaptations he’s starred in on TV or recording this audiobook makes Lloyd feel any sort of profound or poignant connection to him.

He laughs. “I can’t point to a physical sensation like hairs in the back of my neck standing. ‘I feel him. It’s me and Chucky D in the room right now.’”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My thoughts on Sanditon 1x06 (Beware, here be spoilers...)

Okay, up until now I have been watching Sanditon with mixed feelings, most of it positive, but Sundays episode left me screaming WTF at my tv.

In this house, Andrew Davies is a legend. His television adaptations of the classics has always let me soak into the world of Austen, Dickens etc and has been a welcome escape from the various shitty things in my life. He has been adapting books for tv series for decades and I thought that Sanditon was going to be full of the things I love about Jane Austen’s works and subsequent adaptations (wit, satire, self possessed, independent thinking heroines and intelligent, impeccably behaved heroes) with anything else left strictly to the imagination. Austen’s works have always had elegance and propriety to them (even when dealing with sex and ruin) that simply does not appear in this adaptation. There is such a sense of pandering to modern tastes in this episode of Sanditon that I cannot get past...or forgive. This is not an Austen adaptation and I am a little upset that Andrew Davies has interpreted Austen like this. People like Austen for all the subtlety and repressed sexual tension and although Jane did not write more than 11 chapters of Sanditon, surely Andrew has had enough experience dealing with this genre and original material to have written the rest of the story the way Jane might actually have intended.

Anyway, to the episode. I was literally jumping in my seat at the end of episode 1x05 when Charlotte set off on her plucky adventure to Set Things Right and help bring Georgiana home. But when this episode started, it soon became clear that Charlotte had arrived in London with only the flimsiest scrap of a plan and little to no money! (Note- In the rest of the series, Charlotte can be impulsive, but not stupid). Next, Charlotte is made to demonstrate another act of uncharacteristic stupidity by aimlessly wandering around the back streets and alleyways near the docks acting the fresh country girl ripe for the plucking. And of course, someone grabs her. She is rescued by Sidney, but this trope of stupid, naive country girl puts herself in a dangerous situation and has to be rescued by the hero pisses me off.

Oh, and Fyi costume designer, Charlotte should be wearing her hair up, UP, UUUUUUUUUUUPPPPPPPPPPP!!!

When Sidney tells Charlotte off in the carriage, I kind of thought that he had a point; reminding her that there can be other motives for marriage than love, but her looking shocked that this could be so surprises me as she has not previously written to be so naive. But, if you see it from her point of view, Otis rocked up looking dandy af a couple of episodes ago (I’m assuming that Charlotte thought that Otis might not need Georgiana’s money with that snazzy outfit on) and spouting romantic feelings and the telling of a genuinely funny first meeting with Georgiana made her think that it was for love and that it must be prejudice as his fortune has been made from slavery! Charlotte accuses Sidney of being less than forthcoming about his objections to Otis and he is pissed that his vague af explanation did not satisfy our independent thinking heroine. But as I see it, if you can be a first class asshole and scream into the heroine’s face while losing your temper in the street, you sure as hell can be explicit about why you ask someone to keep an extra eye on your ward. Just saying....

Also, Sidney’s behaviour throughout this series to Charlotte has been so far from an Austen hero and has made me dislike him so intensely that I have rooted for young Stringer as Charlotte’s eventual husband (though we all know that’s not going to happen, don’t we). An Austen hero never lets his anger show too strongly nor bellows at the heroine in the street. But apart from the story, good manners in that era and at that social level would prohibit any true gentleman from doing so.

Andrew, if you are not going to follow Austen’s style, then place it in the proper confines of the period. Good fucking manners always prevail!!!!!!!!!

Taking Charlotte to a Brothel?!?!?!?!?!? Gently bred females do not get taken by an Austen hero to a brothel, Jesus Christ! Would this happen in reality? Not really! This scene seems to have been lifted out of the pages of a bodice ripper (not that I have any objection to bodice rippers- I frequently read and love them myself- but in an Austen? No, just no).

Charlotte preventing Sidney from beating the shit out of Otis for ruining Georgiana’s rep with a gentle plea while he reigns in his rage for her by focusing on her face, oh my heart... Still not Austen tho...

There’s finally a flash of the old sensible Charlotte when she figures out that Georgiana might still be held in London, whoops, I sneezed, back to the naive country girl trope that doesn’t fit.

Ewwwww, the fat, misogynistic fucker making a joke about breaking in horses being similar to handling wives while drooling over a forcibly restrained woman just had to be in there didn’t it?

It just bugs me why Clara, Edward and Esther don’t seem to take Lady Denham seriously when she has said repeatedly thought the entire series so far that none of them will benefit monetarily from her death, yet when the will is eventually found, Clara and Edward are outraged when nothing is left to them?

I can’t decide if Charlotte is still the annoying country girl from the beginning of the episode or the plucky heroine determined to find out the truth when she refuses to stay in the carriage when Sidney goes into the brothel where he is clearly a regular member...

‘You haven’t made an honest man of our Mr Parker, have you?’

‘GrAcIOuS NOOOO!’

Sidney’s face. One second of pained outrage. Classic!

Ooooohhhhhhh, a dramatic carriage chase. Area man in a cravat leaping to another carriage to bring the horses to a halt and rescue a girl. Melodrama meets western...

Oh look, Clara has found the hidden will and taken the time to put on a new dress and villain smirk of crazed triumph. Fuck off luv!

Oh. My. God.

Ewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww!!!!!!!!!!!!

Jumping each other and having grunting, rough af sex on the cold marble floor to seal their devils deal? Um, ewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww!