#in urdu we say

Text

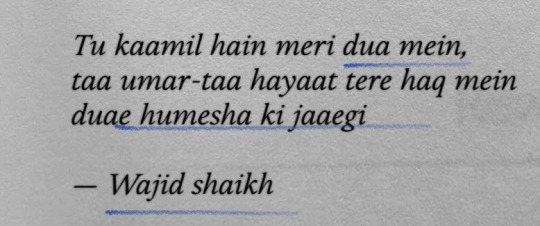

In English we say

you are always in my prayers

But in Urdu

Wajid Shaikh Said

From Book Sukoon 2023,(By Wajid Shaikh ) (Via:- Indo-pak أدب

#wajidshaikhpoetries#shayar#wajidsays#litreature#poetry#jaun eliya#shayari#sukoon#poets#wajid shaikh#In english we say#in urdu we say#Dua#ishq urdu#rekhta

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In English we say: "I've moved on!''

But in Urdu we say:

Waqt ne kiya kya haseen Sitam, Ke woh ab mere ex ban gaye aur ho gaye sare dukh dard Gatam...

🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣😆😆😆

#destiny2shine#quotes#funny#in urdu we say#in english we say#quoteoftheday#reblog#thoughts#sher o shayari#hindi poem#udru poem#love#heartbreak#memes#ex problems#ex bf problems

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

They say : You don’t share much about you

but Wajid Shaikh Said

#wajid shaikh#wajidsays#urdu shayari#urdu sher#shayari#urdulovers#aesthetic#jaun eliya#spotify#wajidshaikhpoetries#aesthetically pleasing#aesthetics#dark aesthetic#dark academia#in english we say#introvert

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

TAR x XINWEER.

For BOYYOFGOD (2023).

#boyyofgod#tar wacharathon#xinweer wutthimeth#tarxinweer#*#faiza gifs#GOD ....... I CANT WAIT FOR THEM THEY HAVE THE 🤌🤌🤌 KUCH BAAT HAIN 🤌🤌🤌 AS WE SAY IN URDU.#ever since i saw the intro story EVERYTIME i see an apple now i think of these 2 and 🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠🫠 BRAIN GOES BRRRRRRR.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it always “but I have got a blank space, baby and I’ll write your name”

And not, kora kagaz tha mann mera likh diya naam uspe tera.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

also. mr sunflower HARDLY knows how to talk in Urdu but HE ASKS ME SO MUCH ABOUT IT AMD TRIES TO TALK TO ME IN URDU I WILL CRY. my heart. he's literally like a small 15cm plushie to me

#something about not using aap with you just feels wrong zainab.#he said stuff like mai har zabaan mai aapse baat karna chahta hu. Har ek#and then hes lkke zImab what do u call topic in urdu#i said mudde#he zaid NO MUDDE IS NOT A ROMANTIC WORD!!!!#pls#and hes from delhi and most people just talk using tum and tu you lnow#bjt i remember when we initially met he used to say tum ajd then slap his mouth and say NO AAP#girl shut up

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

just had a successful interaction on the phone in another language without stuttering or mixing up my words i am Thriving

#do i know what language it was ??? no but idc they understood me well enough so we had to be speaking the same language#i wanna say it was urdu cause that’s more likely and there wasn’t the strong vibes of gujarati so#being able to speak (slightly) and understand multiple similar languages is fun but not being able to differentiate between them is#a thing that constantly haunts me ahsjks it’s why i don’t practice speaking. i should though#faera's

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In English we say:

“Out of all people you misunderstood me”

But in Urdu we say:

“Usay meri baatein ab samajh nahi aati,

Kabhi jo meri khamoshi ki tafseer likha karta tha.”

#urdu lines#dark academia#literature#spilled ink#urdu literature#poetry#writers on tumblr#two line shayari#light academia#izhaar e ishq#urdu poetry#desiblr#urdu aesthetic#artists on tumblr#urdu shayari

437 notes

·

View notes

Note

There is a difference between Bollywood and Bombay cinema?

listen, subcontinental cinema began in bombay; the very first exhibition of the lumieres' cinematographe was held there in 1896, a few months after its debut in paris, 1895. this event predates the discursive existence of bollywood and hollywood. shree pundalik and raja harishchandra, the films that are generally considered the very first subcontinental features were also exhibited there first.

subcontinental cinema under british colonialism was produced in certain metropolitan centers such as lahore, hyderabad, and calcutta; bombay was just one of them. in 1947, when the indian nation state was formally inaugurated, the idea of a "national cinema" began forming, but given the cultural and linguistic heterogeneity of the indian union, this was quite untenable. regional popular cinemas flourished well into the 1950, 60s, 70s, and 80s and various art cinemas began taking shape alongside.

under the economy that i'm going to completely elide as "nehruvian "socialism"" bombay cinema focused on broadly "socialist" themes, think of awara (1951), do beegha zameen (1953), pyaasa (1957), all of which focus on inequality in indian economy and society from different perspectives. these films were peppered in with historical dramas, and adaptations from literature, but the original stories tended towards socialist realism. reformist films centering the family generally waxed poetic on the need to reform the family, but i haven't seen enough of these to really comment on them.

the biggest hit of the 70s, sholay (1975) was about two criminals, posited as heroes fighting gabbar singh who was attacking village folk. deewar (1975) also had two heroes, and the stakes were the two brothers' father's reputation; the father in question was a trade union leader accused of corruption.

"alternative cinema" included mani kaul's uski roti (1969) and Duvidha (1973) both of which were situated away from the city. then there's sayeed mirza and his city films, most of them set in bombay; arvind desai ki ajeeb dastan (1978), albert pinto ko gussa kyun aata hain (1980), saleem langre pe mat ro (1989) which are all extremely socialist films, albert pinto was set in the times of the bombay textiles strike of 1982 and literally quotes marx at one point. my point is that bombay cinema prior to liberalization was varied in its themes and representations, and it wasn't interested in being a "national cinema" very much, it was either interested in maximizing its domestic profits or being high art. note that these are all hindi language films, produced in bombay, or at least using capital from bombay. pyaasa, interestingly enough is set in calcutta, but it was filmed in bombay!

then we come to the 1990s, and i think the ur example of the bollywood film is dilwale dulhania le jayenge (1995) which, in stark contrast to the cinema that preceded it, centered two NRIs, simran and raj, who meet abroad, but epitomize their love in india, and go back to england (america?) as indians with indian culture. this begins a long saga of films originating largely in bombay that target a global audience of both indians and foreigners, in order to export an idea of india to the world. this is crucial for a rapidly neoliberalizing economy, and it coincides with the rise of the hindu right. gradually, urdu recedes from dialogue, the hindi is sankritized and cut with english, the indian family is at the center in a way that's very different for the social reform films of the 50s and 60s. dil chahta hai (2001) happens, where good little indian boys go to indian college, but their careers take them abroad. swadesh (2004) is about shah rukh khan learning that he's needed in india to solve its problems and leaves a job at NASA.

these are incidental, anecdotal illustrations of the differences in narrative for these separate eras of cinema, but let me ground it economically and say that bollywood cinema seeks investments and profits from abroad as well as acclaim and viewership from domestic audiences, in a way that the bombay cinema before it did not, despite the success of shree 420 (1955) in the soviet union; there were outliers, there always have been.

there's also a lot to say about narrative and style in bombay cinema (incredibly diverse) and bollywood cinema (very specific use of hollywood continuity, intercut with musical sequences, also drawn from hollywood). essentially, the histories, political economies, and aesthetics of these cinemas are too differentiated to consider them the same. bombay cinema is further internally differentiated, and that's a different story altogether. look, i could write a monograph on this, but that would take time, so let me add some reading material that will elucidate this without sounding quite as fragmented.

bollywood and globalization: indian popular cinema, nation, and diaspora, rini bhattacharya mehta and rajeshwari v. pandharipande (eds)

ideology of the hindi film: a historical construction, madhav prasad

the 'bollywoodization' of the indian cinema: cultural nationalism in a global arena, ashish rajadhyaksha

the globalization of bollywood: an ethnography of non-elite audiences in india, shakuntala rao

indian film, erik barnouw and s. krishnaswamy (this one's a straight history of subcontinental cinema up to the 60s, nothing to do with bollywood, it's just important because the word bollywood never comes up in it despite the heavy focus on hindi films from bombay, illustrating my point)

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

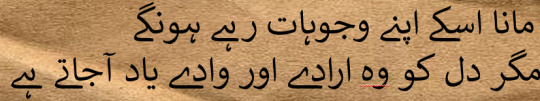

In english we say ,"Let it be, they must have had their own reasons"

But in urdu Someone said,

"Mana uske apne wajuhat rahe honge

magar dil ko woh iraday aur waade yaad aajate ha"

#urdu academia#urdu lines#urdu stuff#jaun elia#poetry#urdu poetry#urdu shayari#70s#spilled thoughts#love poem#spilled ink#desi tumblr#aestheticurdu#urdu#urdu adab#dark academia#اردو#love#heartbroken#light academia#dark acadamia aesthetic#chaotic academia#dark acamedia#romantic academia#classic academia

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

In English we say:

I no longer wait for you.

But in urdu we say:

Na huwa naseeb karaar-e-jaan hawas-e-karaar bhi ab nahi,

Tera intezaar bohot kiya tera intezaar bhi ab nahi.

It's no longer in my fate to find peace of mind, nor do I have the longing for tranquility anymore.I have waited for you a lot; I no longer wait for you.

#jaun elia#desiblr#desi tumblr#desi aesthetic#dark academia#desi academia#urdu lines#urdu poetry#urdu literature#urdu shayari#urdu aesthetic#urdu stuff#dark academia aesthetic#desi people

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

In English they say;

“Lost interests in everything”

But in Urdu we can say;

“Woh silsiley, woh shauq, woh nisbat nahi rahi, woh dil nahi raha, woh tabiyat nahi rahi”

#dark academia#english writing#urdu ghazal#desiblr#desi tumblr#desi tag#urdu stuff#urdu#urdu lines#urdu poetry#urdu adab#rekhta#deep#fav#rekhtashayari#txt post#txt#desi aesthetic#pakistani aesthetics#aesthetics#urdu shayari#urdu posts#urdusadshayari#urdu sad poetry#light academia#choatic academia#desi dark academia#urdualfaz

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

In english we say :

I'll wait no matter what

But in urdu we say :

Sar-e-toor ho, Sar-e-hashr ho, Humein intezar qubool hai

Wo kabhi milein, Wo kahee’n milein , Wo kabhi sahi, Wo kahee’n sahi

#poetry#urdu stuff#urdupoetry#urduquotes#urdu literature#urduadab#urdu lines#urdu ghazal#urduzone#dark academia#peer e kamil

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the West, poetry is written primarily for the afficionado, often other poets. In recent years, I can think of very few poets whose work is on everyone's lips. Perhaps Maya Angelou comes close, maybe Dr. Seuss.

But in Indian culture the situation is different. Tagore's poems - not only his songs, but the words themselves - are known to even the illiterate. Poetry is mass culture.

So it was with Faiz, and before him, Iqbal. Lazard writes:

When he read at a musha'ira, in which poets contended in recitations, fifty thousand people and more gathered to listen, and to participate. People who barely have an education know Faiz's poetry not only because of the songs using his lyrics but also the poems themselves, without musical accompaniment.

But poetry, in these cultures, as in Palestine, has a wide reach, and becomes an instrument of power. Faiz, Iqbal, and Darwish knew it. Like Tagore, they were not merely poets - they sought to transform society.

In an earlier version of the present introduction, written immediately after Faiz's death, Lazard was more personal, more elegiac:

Once when we were saying good-bye after our time in Honolulu I asked for his address. He told me I really didn't need it. A letter would reach him if I simply sent it to Faiz, Pakistan.

The reason - he had helped found the postal workers union. They were his people. They knew where to find him anytime.

So this is where Faiz came from when we met in Honolulu in the winter of 1979.

(Annual of Urdu Studies, v. 5, 1985 p. 103-110)

text from review by Amit Mukherjee of The true subject: selected poems of Faiz Ahmed Faiz translated by Naomi Lazard

363 notes

·

View notes