#laissez faire capitalism

Photo

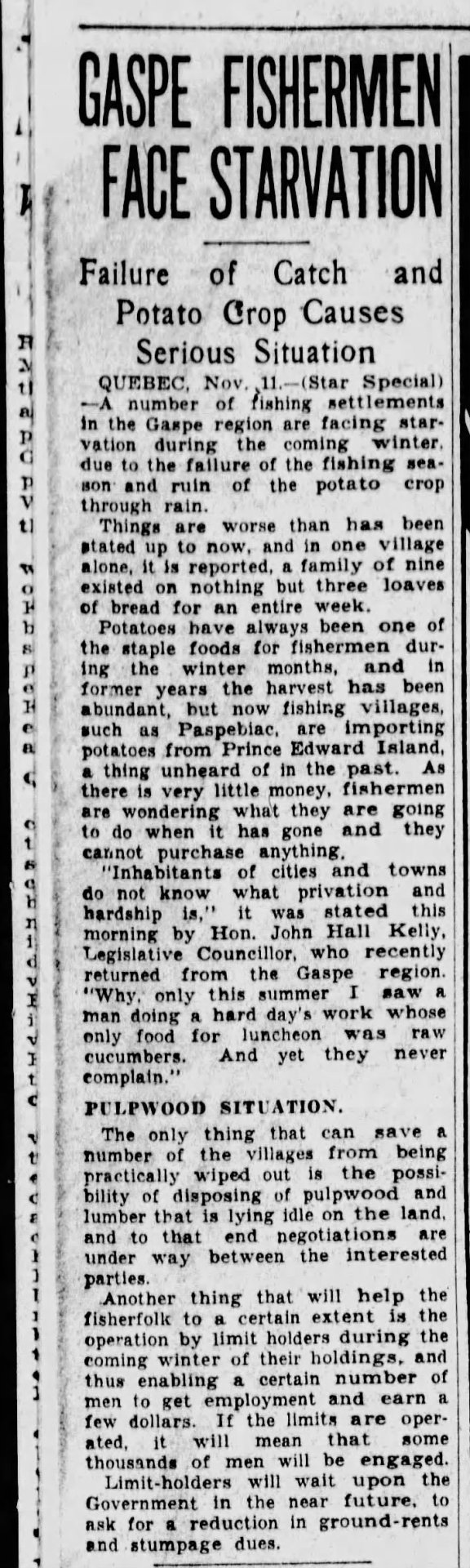

“Gaspe Fishermen Face Starvation,” Montreal Star. November 11, 1932. Page 21.

---

Failure of Catch and Potato Crop Causes Serious Situation

----

QUEBEC, Nov 11— (Star Special) —A number of fishing settlements in the Gaspe region are facing starvation during the coming winter, due to the failure of the fishing season and ruin of the potato crop through rain.

Things are worse than has been stated up to now, and in one village alone, it is reported a family of nine existed on nothing but three loaves of bread for an entire week.

Potatoes have always been one of the staple foods for fishermen during the winter months and in former years the harvest has been abundant but now fishing villages, such as Paspebiac, are importing potatoes from Prince Edward Island, a thing unheard of in the past. As there la very little money, fisherman are wondering what they are going to do when it has gone and they cannot purchase anything.

“Inhabitant of cities and towns do not know what privation and hardship is," it was stated this morning by Hon.John Hall Kelley, Legislative Counselor who recently returned from the Gaspe region. "Why, only this summer I saw a man doing a hard day work whose only food for luncheon was' raw cucumber. And yet they never complain." r

PULPWOOD SITUATION

The only thing that can save a number of the villages from being practically wiped out is the possibility of disposing of pulpwood and ‘umber that is lying idle on the land, and to that end, negotiations are under way between the interested parties.

Another thing that will help the fisherfolk to a certain extent is the operation by limit holders during the coming winter of their holdings and thus enabling a certain number of men to get employment and earn a few dollars. If the limits are operated, it will mean that some thousands of men will be engaged. Limit-holders will wait upon the Government In the near future to ask for a reduction In ground-rents and stumpage dues.

#gaspésie#gaspe#crop failure#famine#rural poverty#fisherfolk#subsistence farming#farming in canada#lumber industry#capitalism in crisis#laissez faire capitalism#seasonal workers#precarious labour#rural québec#great depression in canada

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't hate being human. I truly don't.

Yes. I'd much rather be furred and possess a tail and fly through taiga snows on four limbs in the night. But I don't hate humans or even the condition of being human.

Humans are... adorable. Innovative. Compassionate. Playful. Their cognition, their self-awareness, their capacity for consciousness and higher order thinking... all lends itself to a fascinating, introspective social species. Their drive to promote welfare transcends the self, even blood relation, and even species. There's pride to be had in being human.

"Human being" as a noun and even as a verb, "human-being": the activity of existing as a human. Human-being: being... human.

I hate the Protestant work ethic-- notion that life is best spent on maximal labor in the name of a merciful God. I hate the modern secular work ethic-- notion that life is best spent on maximal labor for... self-fulfillment.

I hate exchange culture-- definition of identity and relationships by (material) input and output. Laisser-faire exchange systems.

I hate vertical, hierarchical arrangements of control. Individualist culture within vertical power structures-- the antisocialism inherent to every institution and organization; its strong incentive for antisocial behavior and catastrophic consequences for prosocial behavior.

Humans are not defined by these things-- a globe of 7 billion of them and counting live this way or similar. Circumstance is not to be conflated with nature.

The humans who uphold these institutions, attitudes, expectations, and values have every motive to make you believe that these are the only ones-- the one true way, the supreme state of human being.

They have everything to gain from you resigning yourself to this "truth". They have everything to gain from having everyone believe their human-being is the correct way to human-be. That their human is the only human.

But the real truth is that you are human. I am human.

I do not hate being human.

I hate being as their human.

#just a. half-vent I guess#antiwork#guillotine the rich#fuck capitalism#leftblr#abolish work#abolish capitalism#cultural orientation#vertical individualism#laissez-faire#posts that are just oddly comforting?? in a way you can't articulate#ecofascism

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are their thoughts on Wondertainment

Negative. They have extremely low opinions of capitalism, and of what they perceived – not wrongly – as flagrant irresponsibility

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

crazy what advocates of the free market do when the market behaves… freely?

#like damn what happened to ur rhetoric about letting consumers decide what succeeds or fails in the marketplace#not very laissez-faire capitalism of u. COMMIT TO THE BIT U COWARDS!!

0 notes

Text

the funniest part of american politics is when people refer to democrats as "the left" ex. "the right and left have both done nothing on this issue" like girl the democratic party is center-right at best, just look at other countries' political landscapes. any gains made by members of that party in favor of the people is basically a fluke atp and rarely occurs at the national level. there are actual left-wing groups here but generally they are not on tv jacking off about what john adams would have wanted

0 notes

Text

Paul Ryan is the speaker of the house of Dres.”

#TEXT#DAY 0#Paul ryan 😜😍laissez faire 😱😱capitalism 😩😩👌🏾👌🏾👌🏾🤤🤤💦💦Kentucky senator 😱tea ☕️🍵party🎉🎊DEREGULATION 😝😋‼️⚠️‼️Reaganomics 😩😩🙏🏾🙏🏾Austerity 😍🤤😛the

0 notes

Text

Disco Elysium's setting was formerly the site of a communist revolution that established the Commune of Revachol. It didn't last long. The Coalition of Nations brutally put the communists down, divided the city among themselves, and enforced a free market capitalist system. The results are depressingly apparent in Revachol's dilapidated district of Martinaise. "The literacy rate is around 45% west of the river," Joyce Messier, a negotiator sent to parley with Martinaise's striking union, tells our protagonist. "Fifty years of occupation have left these people in an *oblivion* of poverty."

This state of affairs is overseen by the Moralist International, a union of centre-left and centre-right parties that professes to represent the cause of humanism, but whose primary concern is transparently the preservation of capitalist interest – a Coalition official happily tells us that "the Coalition is only looking out for *ze price stabilitié*", arguing that inflation in Revachol must be prevented, comparing it to a heart disease that could block the "normal circulation of the economy". The people of Revachol don't matter. Their suffering and oppression is only significant as a necessary symptom of the system functioning as intended.

The most biting aspect of this critique of capitalist exploitation can be found in the cynicism of those who represent Moralism, or at least, its interests. The aforementioned Joyce Messier is its perfect embodiment. She does not believe in the facade of humanity Moralism presents to the world, and is under no illusions about what it has done to the people of Martinaise. She tells you how bad things are, freely admitting that the pieces of legislation put in place by the Moralist Coalition to govern Revachol are there to keep "the city in a [...] laissez-faire stasis to the benefit of foreign capital". This corrosion of belief via cynicism, this depiction of a system that continues to operate unimpeded despite few believing in it, feels all too familiar.

This critique of liberal capitalism's hypocrisy, cynicism, exploitation and deep-rooted connections to colonialism, is particularly powerful in recognising the precarious position it finds itself in. It has reached a stasis that seems, paradoxically, both insurmountable, and on the verge of collapse. Moralism relies on this contradiction. It's unofficial motto, "for a moment, there was hope", underlines the degree to which its dominance depends on the preclusion of the idea that a better world is possible, that there is no alternative, echoing the End of History sentiment that created the (rapidly disintegrating) political consensus of our lived reality.

Despite growing dissatisfaction with the status quo in the real world, it has, indeed, proved difficult to imagine an alternative. The oft-repeated phrase attributed to literary critic and political theorist Fredric Jameson, that is is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of capitalism, has almost become a cliché. However, the mistake Joyce makes, and one that we should avoid, is to assume that this means an alternative won't emerge nonetheless.

[...]

In a world where everyone is encouraged to look out for themselves, Disco Elysium suggests we should remember the value of collectivity, camaraderie and community. The Deserter has forgotten that though the communism he identified with is dead, the values that brought people to its cause in search of a better world remain as valid as ever. Bleak as it is, those values exist in Martinaise. They exist in us. Their latent power has the potential to lead us towards better horizons.

681 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do economists need to shut up about mercantilism, as you alluded to in your post about Louis XIV's chief ministers?

In part due to their supposed intellectual descent from Adam Smith and the other classical economists, contemporary economists are pretty uniformly hostile to mercantilism, seeing it as a wrong-headed political economy that held back human progress until it was replaced by that best of all ideas: capitalism.

As a student of economic history and the history of political economy, I find that economists generally have a pretty poor understanding of what mercantilists actually believed and what economic policies they actually supported. In reality, a lot of the things that economists see as key advances in the creation of capitalism - the invention of the joint-stock company, the creation of financial markets, etc. - were all accomplishments of mercantiism.

Rather than the crude stereotype of mercantilists as a bunch of monetary weirdos who thought the secret to prosperity was the hoarding of precious metals, mercantilists were actually lazer-focused on economic development. The whole business about trying to achieve a positive balance of trade and financial liquidity and restraining wages was all a means to an end of economic development. Trade surpluses could be invested in manufacturing and shipping, gold reserves played an important role in deepening capital pools and thus increasing levels of investment at lower interest rates that could support larger-scale and more capital intensive enterprises, and so forth.

Indeed, the arch-sin of mercantilism in the eyes of classical and contemporary economists, their interference in free trade through tariffs, monopolies, and other interventions, was all directed at the overriding economic goal of climbing the value-added ladder.

Thus, England (and later Britain) put a tariff on foreign textiles and an export tax on raw wool and forbade the emigration of skilled workers (while supporting the immigration of skilled workers to England) and other mercantilist policies to move up from being exporters of raw wool (which meant that most of the profits from the higher value-added part of the industry went to Burgundy) to being exporters of cheap wool cloth to being exporters of more advanced textiles. Hell, even Adam Smith saw the logic of the Navigation Acts!

And this is what brings me to the most devastating critique of the standard economist narrative about mercantilism: the majority of the countries that successfully industrialized did so using mercantilist principles rather than laissez-faire principles:

When England became the first industrial economy, it did so under strict protectionist policies and only converted to free trade once it had gained enough of a technological and economic advantage over its competitors that it didn't need protectionism any more.

When the United States industrialized in the 19th century and transformed itself into the largest economy in the world, it did so from behind high tariff walls.

When Germany made itself the leading industrial power on the Continent, it did so by rejecting English free trade economics and having the state invest heavily in coal, steel, and railroads. Free trade was only for within the Zollverein, not with the outside world.

And as Dani Rodrik, Ha-Joon Chang, and others have pointed out, you see the same thing with Japan, South Korea, China...everywhere you look, you see protectionism as the means of achieving economic development, and then free trade only working for already-developed economies.

#political economy#mercantilism#economic development#early modern state-building#early modern period#laissez-faire#classical liberalism#classical economics#economics#economic history

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, it looks to me about like this.

Classical liberals say that central planning is fundamentally flawed because the economic calculation problem can't be solved, and they're basically right.

Marxists say that laissez-faire capitalism is fundamentally flawed because it leads inexorably to wage slavery, and they're basically right.

Anarchists say "fuck it, free for all (+mutual aid)", but then you run into the tragedy of the commons.

Welfarist liberals have a vision of the economy cobbled together with sticks and duct tape, but at a crude level it does work.

There are a bunch of funkier proposals out there, from Georgism to "free-market anti-capitalism", that mostly seem like linear combinations of bits and pieces of the above systems and as a consequence inherit many of their faults.

Nobody's got anything good. Or, people have good ideas but they're held back by overconfidence or underdefinition. I need to read more, study the extant proposals and extract what can be extracted from them.

I'm not really interested in arguing the above points. I mean, I am, but not here. I'm confident enough in my assessment of the general lay of the land that a random tumblr argument does not seem likely to present me with something new that I have not considered (at least as far as the banally ideological goes). If anyone has been reading or thinking about something really new, I want to hear it.

I'll keep contemplating, and generating proposals, and asking questions. Maybe that will continue to incite knowledgeable people to contribute in the way that I am looking for. Hmm.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.5 What about the lack of enclosures in the Americas?

The enclosure movement was but one part of a wide-reaching process of state intervention in creating capitalism. Moreover, it is just one way of creating the “land monopoly” which ensured the creation of a working class. The circumstances facing the ruling class in the Americas were distinctly different than in the Old World and so the “land monopoly” took a different form there. In the Americas, enclosures were unimportant as customary land rights did not really exist (at least once the Native Americans were eliminated by violence). Here the problem was that (after the original users of the land were eliminated) there were vast tracts of land available for people to use. Other forms of state intervention were similar to that applied under mercantilism in Europe (such as tariffs, government spending, use of unfree labour and state repression of workers and their organisations and so on). All had one aim, to enrich and power the masters and dispossess the actual producers of the means of life (land and means of production).

Unsurprisingly, due to the abundance of land, there was a movement towards independent farming in the early years of the American colonies and subsequent Republic and this pushed up the price of remaining labour on the market by reducing the supply. Capitalists found it difficult to find workers willing to work for them at wages low enough to provide them with sufficient profits. It was due to the difficulty in finding cheap enough labour that capitalists in America turned to slavery. All things being equal, wage labour is more productive than slavery but in early America all things were not equal. Having access to cheap (indeed, free) land meant that working people had a choice, and few desired to become wage slaves and so because of this, capitalists turned to slavery in the South and the “land monopoly” in the North.

This was because, in the words of Maurice Dobb, it “became clear to those who wished to reproduce capitalist relations of production in the new country that the foundation-stone of their endeavour must be the restriction of land-ownership to a minority and the exclusion of the majority from any share in [productive] property.” [Studies in Capitalist Development, pp. 221–2] As one radical historian puts it, ”[w]hen land is ‘free’ or ‘cheap’. as it was in different regions of the United States before the 1830s, there was no compulsion for farmers to introduce labour-saving technology. As a result, ‘independent household production’ … hindered the development of capitalism … [by] allowing large portions of the population to escape wage labour.” [Charlie Post, “The ‘Agricultural Revolution’ in the United States”, pp. 216–228, Science and Society, vol. 61, no. 2, p. 221]

It was precisely this option (i.e. of independent production) that had to be destroyed in order for capitalist industry to develop. The state had to violate the holy laws of “supply and demand” by controlling the access to land in order to ensure the normal workings of “supply and demand” in the labour market (i.e. that the bargaining position favoured employer over employee). Once this situation became the typical one (i.e., when the option of self-employment was effectively eliminated) a more (protectionist based) “laissez-faire” approach could be adopted, with state action used indirectly to favour the capitalists and landlords (and readily available to protect private property from the actions of the dispossessed).

So how was this transformation of land ownership achieved?

Instead of allowing settlers to appropriate their own farms as was often the case before the 1830s, the state stepped in once the army had cleared out (usually by genocide) the original users. Its first major role was to enforce legal rights of property on unused land. Land stolen from the Native Americans was sold at auction to the highest bidders, namely speculators, who then sold it on to farmers. This process started right “after the revolution, [when] huge sections of land were bought up by rich speculators” and their claims supported by the law. [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 125] Thus land which should have been free was sold to land-hungry farmers and the few enriched themselves at the expense of the many. Not only did this increase inequality within society, it also encouraged the development of wage labour — having to pay for land would have ensured that many immigrants remained on the East Coast until they had enough money. Thus a pool of people with little option but to sell their labour was increased due to state protection of unoccupied land. That the land usually ended up in the hands of farmers did not (could not) countermand the shift in class forces that this policy created.

This was also the essential role of the various “Homesteading Acts” and, in general, the “Federal land law in the 19th century provided for the sale of most of the public domain at public auction to the higher bidder … Actual settlers were forced to buy land from speculators, at prices considerably above the federal minimal price.” (which few people could afford anyway). [Charlie Post, Op. Cit., p. 222] This is confirmed by Howard Zinn who notes that 1862 Homestead Act “gave 160 acres of western land, unoccupied and publicly owned, to anyone who would cultivate it for five years … Few ordinary people had the $200 necessary to do this; speculators moved in and bought up much of the land. Homestead land added up to 50 million acres. But during the Civil War, over 100 million acres were given by Congress and the President to various railroads, free of charge.” [Op. Cit., p. 233] Little wonder the Individualist Anarchists supported an “occupancy and use” system of land ownership as a key way of stopping capitalist and landlord usury as well as the development of capitalism itself.

This change in the appropriation of land had significant effects on agriculture and the desirability of taking up farming for immigrants. As Post notes, ”[w]hen the social conditions for obtaining and maintaining possession of land change, as they did in the Midwest between 1830 and 1840, pursuing the goal of preserving [family ownership and control] .. . produced very different results. In order to pay growing mortgages, debts and taxes, family farmers were compelled to specialise production toward cash crops and to market more and more of their output.” [Op. Cit., p. 221–2]

So, in order to pay for land which was formerly free, farmers got themselves into debt and increasingly turned to the market to pay it off. Thus, the “Federal land system, by transforming land into a commodity and stimulating land speculation, made the Midwestern farmers dependent upon markets for the continual possession of their farms.” Once on the market, farmers had to invest in new machinery and this also got them into debt. In the face of a bad harvest or market glut, they could not repay their loans and their farms had to be sold to so do so. By 1880, 25% of all farms were rented by tenants, and the numbers kept rising. In addition, the “transformation of social property relations in northern agriculture set the stage for the ‘agricultural revolution’ of the 1840s and 1850s … [R]ising debts and taxes forced Midwestern family farmers to compete as commodity producers in order to maintain their land-holding … The transformation … was the central precondition for the development of industrial capitalism in the United States.” [Charlie Post, Op. Cit., p. 223 and p. 226]

It should be noted that feudal land owning was enforced in many areas of the colonies and the early Republic. Landlords had their holdings protected by the state and their demands for rent had the full backing of the state. This lead to numerous anti-rent conflicts. [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 84 and pp. 206–11] Such struggles helped end such arrangements, with landlords being “encouraged” to allow the farmers to buy the land which was rightfully theirs. The wealth appropriated from the farmers in the form of rent and the price of the land could then be invested in industry so transforming feudal relations on the land into capitalist relations in industry (and, eventually, back on the land when the farmers succumbed to the pressures of the capitalist market and debt forced them to sell).

This means that Murray Rothbard’s comment that “once the land was purchased by the settler, the injustice disappeared” is nonsense — the injustice was transmitted to other parts of society and this, the wider legacy of the original injustice, lived on and helped transform society towards capitalism. In addition, his comment about “the establishment in North America of a truly libertarian land system” would be one the Individualist Anarchists of the period would have seriously disagreed with! [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 73] Rothbard, at times, seems to be vaguely aware of the importance of land as the basis of freedom in early America. For example, he notes in passing that “the abundance of fertile virgin land in a vast territory enabled individualism to come to full flower in many areas.” [Conceived in Liberty, vol. 2, p. 186] Yet he did not ponder the transformation in social relationships which would result when that land was gone. In fact, he was blasé about it. “If latecomers are worse off,” he opined, “well then that is their proper assumption of risk in this free and uncertain world. There is no longer a vast frontier in the United States, and there is no point crying over the fact.” [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 240] Unsurprisingly we also find Murray Rothbard commenting that Native Americans “lived under a collectivistic regime that, for land allocation, was scarcely more just than the English governmental land grab.” [Conceived in Liberty, vol. 1, p. 187] That such a regime made for increased individual liberty and that it was precisely the independence from the landlord and bosses this produced which made enclosure and state land grabs such appealing prospects for the ruling class was lost on him.

Unlike capitalist economists, politicians and bosses at the time, Rothbard seemed unaware that this “vast frontier” (like the commons) was viewed as a major problem for maintaining labour discipline and appropriate state action was taken to reduce it by restricting free access to the land in order to ensure that workers were dependent on wage labour. Many early economists recognised this and advocated such action. Edward Wakefield was typical when he complained that “where land is cheap and all are free, where every one who so pleases can easily obtain a piece of land for himself, not only is labour dear, as respects the labourer’s share of the product, but the difficulty is to obtain combined labour at any price.” This resulted in a situation were few “can accumulate great masses of wealth” as workers “cease … to be labourers for hire; they … become independent landowners, if not competitors with their former masters in the labour market.” Unsurprisingly, Wakefield urged state action to reduce this option and ensure that labour become cheap as workers had little choice but to seek a master. One key way was for the state to seize the land and then sell it to the population. This would ensure that “no labourer would be able to procure land until he had worked for money” and this “would produce capital for the employment of more labourers.” [quoted by Marx, Op. Cit., , p. 935, p. 936 and p. 939] Which is precisely what did occur.

At the same time that it excluded the working class from virgin land, the state granted large tracts of land to the privileged classes: to land speculators, logging and mining companies, planters, railroads, and so on. In addition to seizing the land and distributing it in such a way as to benefit capitalist industry, the “government played its part in helping the bankers and hurting the farmers; it kept the amount of money — based in the gold supply — steady while the population rose, so there was less and less money in circulation. The farmer had to pay off his debts in dollars that were harder to get. The bankers, getting loans back, were getting dollars worth more than when they loaned them out — a kind of interest on top of interest. That was why so much of the talk of farmers’ movements in those days had to do with putting more money in circulation.” [Zinn, Op. Cit., p. 278] This was the case with the Individualist Anarchists at the same time, we must add.

Overall, therefore, state action ensured the transformation of America from a society of independent workers to a capitalist one. By creating and enforcing the “land monopoly” (of which state ownership of unoccupied land and its enforcement of landlord rights were the most important) the state ensured that the balance of class forces tipped in favour of the capitalist class. By removing the option of farming your own land, the US government created its own form of enclosure and the creation of a landless workforce with little option but to sell its liberty on the “free market”. They was nothing “natural” about it. Little wonder the Individualist Anarchist J.K. Ingalls attacked the “land monopoly” with the following words:

“The earth, with its vast resources of mineral wealth, its spontaneous productions and its fertile soil, the free gift of God and the common patrimony of mankind, has for long centuries been held in the grasp of one set of oppressors by right of conquest or right of discovery; and it is now held by another, through the right of purchase from them. All of man’s natural possessions … have been claimed as property; nor has man himself escaped the insatiate jaws of greed. The invasion of his rights and possessions has resulted … in clothing property with a power to accumulate an income.” [quoted by James Martin, Men Against the State, p. 142]

Marx, correctly, argued that “the capitalist mode of production and accumulation, and therefore capitalist private property, have for their fundamental condition the annihilation of that private property which rests on the labour of the individual himself; in other words, the expropriation of the worker.” [Capital, Vol. 1, p. 940] He noted that to achieve this, the state is used:

“How then can the anti-capitalistic cancer of the colonies be healed? . .. Let the Government set an artificial price on the virgin soil, a price independent of the law of supply and demand, a price that compels the immigrant to work a long time for wages before he can earn enough money to buy land, and turn himself into an independent farmer.” [Op. Cit., p. 938]

Moreover, tariffs were introduced with “the objective of manufacturing capitalists artificially” for the “system of protection was an artificial means of manufacturing manufacturers, or expropriating independent workers, of capitalising the national means of production and subsistence, and of forcibly cutting short the transition … to the modern mode of production,” to capitalism [Op. Cit., p. 932 and pp. 921–2]

So mercantilism, state aid in capitalist development, was also seen in the United States of America. As Edward Herman points out, the “level of government involvement in business in the United States from the late eighteenth century to the present has followed a U-shaped pattern: There was extensive government intervention in the pre-Civil War period (major subsidies, joint ventures with active government participation and direct government production), then a quasi-laissez faire period between the Civil War and the end of the nineteenth century [a period marked by “the aggressive use of tariff protection” and state supported railway construction, a key factor in capitalist expansion in the USA], followed by a gradual upswing of government intervention in the twentieth century, which accelerated after 1930.” [Corporate Control, Corporate Power, p. 162]

Such intervention ensured that income was transferred from workers to capitalists. Under state protection, America industrialised by forcing the consumer to enrich the capitalists and increase their capital stock. “According to one study, if the tariff had been removed in the 1830s ‘about half the industrial sector of New England would have been bankrupted’ … the tariff became a near-permanent political institution representing government assistance to manufacturing. It kept price levels from being driven down by foreign competition and thereby shifted the distribution of income in favour of owners of industrial property to the disadvantage of workers and customers.” This protection was essential, for the “end of the European wars in 1814 … reopened the United States to a flood of British imports that drove many American competitors out of business. Large portions of the newly expanded manufacturing base were wiped out, bringing a decade of near-stagnation.” Unsurprisingly, the “era of protectionism began in 1816, with northern agitation for higher tariffs.” [Richard B. Du Boff, Accumulation and Power, p. 56, p. 14 and p. 55] Combined with ready repression of the labour movement and government “homesteading” acts (see section F.8.5), tariffs were the American equivalent of mercantilism (which, after all, was above all else a policy of protectionism, i.e. the use of government to stimulate the growth of native industry). Only once America was at the top of the economic pile did it renounce state intervention (just as Britain did, we must note).

This is not to suggest that government aid was limited to tariffs. The state played a key role in the development of industry and manufacturing. As John Zerzan notes, the “role of the State is tellingly reflected by the fact that the ‘armoury system’ now rivals the older ‘American system of manufactures’ term as the more accurate to describe the new system of production methods” developed in the early 1800s. [Elements of Refusal, p. 100] By the middle of the nineteenth century “a distinctive ‘American system of manufactures’ had emerged . .. The lead in technological innovation [during the US Industrial Revolution] came in armaments where assured government orders justified high fixed-cost investments in special-pursue machinery and managerial personnel. Indeed, some of the pioneering effects occurred in government-owned armouries.” Other forms of state aid were used, for example the textile industry “still required tariffs to protect [it] from … British competition.” [William Lazonick, Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 218 and p. 219] The government also “actively furthered this process [of ‘commercial revolution’] with public works in transportation and communication.” In addition to this “physical” aid, “state government provided critical help, with devices like the chartered corporation” [Richard B. Du Boff, Op. Cit., p. 15] As we noted in section B.2.5, there were changes in the legal system which favoured capitalist interests over the rest of society.

Nineteenth-century America also went in heavily for industrial planning — occasionally under that name but more often in the name of national defence. The military was the excuse for what is today termed rebuilding infrastructure, picking winners, promoting research, and co-ordinating industrial growth (as it still is, we should add). As Richard B. Du Boff points out, the “anti-state” backlash of the 1840s onwards in America was highly selective, as the general opinion was that ”[h]enceforth, if governments wished to subsidise private business operations, there would be no objection. But if public power were to be used to control business actions or if the public sector were to undertake economic initiatives on its own, it would run up against the determined opposition of private capital.” [Op. Cit., p. 26]

State intervention was not limited to simply reducing the amount of available land or enforcing a high tariff. “Given the independent spirit of workers in the colonies, capital understood that great profits required the use of unfree labour.” [Michael Perelman, The Invention of Capitalism, p. 246] It was also applied in the labour market as well. Most obviously, it enforced the property rights of slave owners (until the civil war, produced when the pro-free trade policies of the South clashed with the pro-tariff desires of the capitalist North). The evil and horrors of slavery are well documented, as is its key role in building capitalism in America and elsewhere so we will concentrate on other forms of obviously unfree labour. Convict labour in Australia, for example, played an important role in the early days of colonisation while in America indentured servants played a similar role.

Indentured service was a system whereby workers had to labour for a specific number of years usually in return for passage to America with the law requiring the return of runaway servants. In theory, of course, the person was only selling their labour. In practice, indentured servants were basically slaves and the courts enforced the laws that made it so. The treatment of servants was harsh and often as brutal as that inflicted on slaves. Half the servants died in the first two years and unsurprisingly, runaways were frequent. The courts realised this was a problem and started to demand that everyone have identification and travel papers.

It should also be noted that the practice of indentured servants also shows how state intervention in one country can impact on others. This is because people were willing to endure indentured service in the colonies because of how bad their situation was at home. Thus the effects of primitive accumulation in Britain impacted on the development of America as most indentured servants were recruited from the growing number of unemployed people in urban areas there. Dispossessed from their land and unable to find work in the cities, many became indentured servants in order to take passage to the Americas. In fact, between one half to two thirds of all immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants and, at times, three-quarters of the population of some colonies were under contracts of indenture. That this allowed the employing class to overcome their problems in hiring “help” should go without saying, as should its impact on American inequality and the ability of capitalists and landlords to enrich themselves on their servants labour and to invest it profitably.

As well as allowing unfree labour, the American state intervened to ensure that the freedom of wage workers was limited in similar ways as we indicated in section F.8.3. “The changes in social relations of production in artisan trades that took place in the thirty years after 1790,” notes one historian, “and the … trade unionism to which … it gave rise, both replicated in important respects the experience of workers in the artisan trades in Britain over a rather longer period … The juridical responses they provoked likewise reproduced English practice. Beginning in 1806, American courts consciously seized upon English common law precedent to combat journeymen’s associations.” Capitalists in this era tried to “secure profit … through the exercise of disciplinary power over their employees.” To achieve this “employers made a bid for legal aid” and it is here “that the key to law’s role in the process of creating an industrial economy in America lies.” As in the UK, the state invented laws and issues proclamations against workers’ combinations, calling them conspiracies and prosecuting them as such. Trade unionists argued that laws which declared unions as illegal combinations should be repealed as against the Constitution of the USA while “the specific cause of trademens protestations of their right to organise was, unsurprisingly, the willingness of local authorities to renew their resort to conspiracy indictments to countermand the growing power of the union movement.” Using criminal conspiracy to counter combinations among employees was commonplace, with the law viewing a “collective quitting of employment [as] a criminal interference” and combinations to raise the rate of labour “indictable at common law.” [Christopher L. Tomlins, Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic, p. 113, p. 295, p. 159 and p. 213] By the end of the nineteenth century, state repression for conspiracy was replaced by state repression for acting like a trust while actual trusts were ignored and so laws, ostensibly passed (with the help of the unions themselves) to limit the power of capital, were turned against labour (this should be unsurprising as it was a capitalist state which passed them). [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 254]

Another key means to limit the freedom of workers was denying departing workers their wages for the part of the contract they had completed. This “underscored the judiciary’s tendency to articulate their approval” of the hierarchical master/servant relationship in terms of its “social utility: It was a necessary and desirable feature of the social organisation of work … that the employer’s authority be reinforced in this way.” Appeals courts held that “an employment contract was an entire contract, and therefore that no obligation to pay wages existed until the employee had completed the agreed term.” Law suits “by employers seeking damages for an employee’s departure prior to the expiry of an agreed term or for other forms of breach of contract constituted one form of legally sanctioned economic discipline of some importance in shaping the employment relations of the nineteenth century.” Thus the boss could fire the worker without paying their wages while if the worker left the boss he would expect a similar outcome. This was because the courts had decided that the “employer was entitled not only to receipt of the services contracted for in their entirety prior to payment but also to the obedience of the employee in the process of rendering them.” [Tomlins, Op. Cit., pp. 278–9, p. 274, p. 272 and pp. 279–80] The ability of workers to seek self-employment on the farm or workplace or even better conditions and wages were simply abolished by employers turning to the state.

So, in summary, the state could remedy the shortage of cheap wage labour by controlling access to the land, repressing trade unions as conspiracies or trusts and ensuring that workers had to obey their bosses for the full term of their contract (while the bosses could fire them at will). Combine this with the extensive use of tariffs, state funding of industry and infrastructure among many other forms of state aid to capitalists and we have a situation were capitalism was imposed on a pre-capitalist nation at the behest of the wealthy elite by the state, as was the case with all other countries.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

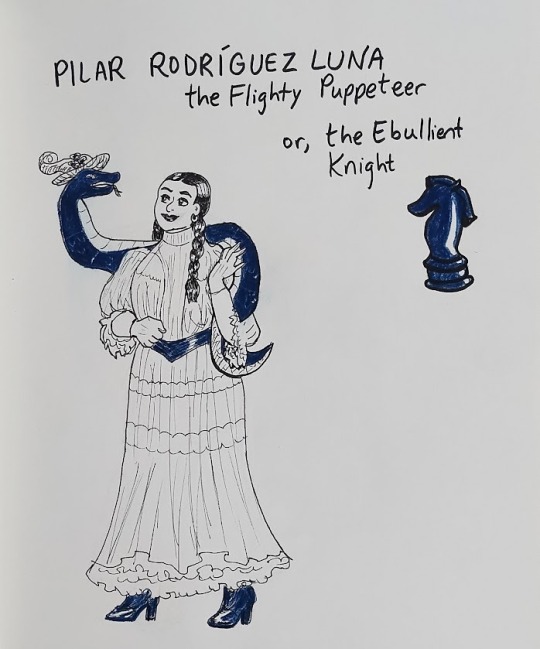

Character Timeline: Pilar Rodriguez Luna

Pilar's timeline goes along with Angeline's, which you can read here!

1868:

Pilar is born to a working-class mestizo family (European and Mixtec ancestry) in Oaxaca, Mexico. She is assigned male at birth and raised as a boy.

She’s educated at parochial school, where she does well, known for her lively intellect and predisposition for music, dancing, and sculpture.

1896:

Pilar goes to the capital, Mexico City, to study law, but while she’s there, she makes tons of friends in the theater scene. She especially develops a taste for puppetry, inspired by the tradition of carnival and mask folk art which originated from Black and Indigenous Mexicans. She learns craftsmanship from artisans and develops a small following among both lower and upper classes.

1898:

As she ages, Pilar discovers that she feels uncomfortable with manhood, and she attributes this to her attraction for both men and women. She begins incorporating female impersonation in some of her acts, and she has relationships with both men and women.

1899:

Pilar gets more involved in leftist anarchist circles, specifically with the Partido Liberal Mexicano. At this point, she’s making a living performing, including for the ruling elite, but revolutionary messages and themes creep into her shows.

(At this time, Mexico was in a period called the Porfiriato, a dictatorship under Porfirio Diaz. Upper and upwardly-mobile classes were prosperous thanks to Diaz’s laissez-faire policies attracting US investors. But the working and lower classes suffered, especially many Indigenous people in the Yucatan, who were basically enslaved.)

1900:

After a Partido Liberal uprising that the military crushes, one of Pilar’s performances is a little too obvious in its symbolism—a herd of pigs stampedes a jaguar, causing other jaguars to send the pigs to their bloody demise. The next day, soldiers search Pilar’s apartment, and she’s banned from performing further.

Pilar continues to perform in secret, but one of her clandestine performances is raided, too, and she’s arrested. The experience leaves her shaken. Her comrades begin to fear for her life. They make arrangements for her to flee to the United States.

One of the operatives who knows about Pilar’s sexuality confides in her that he’s heard that since London was swallowed into the earth, its attitudes regarding sex and gender have loosened up. There’s also something about a Moonlit Chessboard where it’s possible to tip the scales of power in ways that you can’t do in the waking world. Pilar’s interest is piqued, and she asks if she could be sent as an agent there.

For the arduous journey to London, Pilar “disguises” herself as a woman. Then she arrives in London and just…doesn’t take the disguise off. The only puppet she has left with her is a small marionette of a woman that, secretly, is what she’s always hoped to look like.

1899 (1901):

Pilar has started Neath HRT and begun to learn English. To pay the bills, she goes back to puppetry, experimenting with all the new materials and figures available in the Neath. She spends time at Wilmot’s End, studies the mirrors, finds Parabola and the Chessboard.

1899 (1902):

Pilar’s puppetry career has taken off more than ever. She’s always pushing the boundaries of what she can do with both practical effects and Silverer-ing. But she is notoriously difficult to pin down for fans and the press, earning her the moniker “the Flighty Puppeteer.” Though she doesn’t have many close friends, she’s happy enough.

Then she hears that one of her lovers back in Mexico has been killed, jump-starting her Nemesis ambition. And in her dreams of the chessboard, there’s one Red Bishop who, it seems, plans all her moves not to further the Red cause in general—but to corner Pilar.

#pilar rodriguez#angeline hui#my reference people for pilar are: jim henson and chappell roan if that gives you an idea about what she's like lmao#i gotta draw her in some wild looks sometime#police violence

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's also funny that in Victoria 2, if you play as a developing nation outside of the great powers (say, Argentina) and if you implement liberal laissez faire economics, your economy goes to absolute shit. The only good way to play Victoria 2 is with state capitalism or a command economy, because otherwise the invisible hand of the market screws you.

If the Liberals get in charge of Argentina, it ruins the country for generations. 10/10 excellent realism.

#cosas mias#there is no real representation in either Vic2 or 3 about the conservative-liberal-nationalist-progressive generation of 80'#which were a bunch of racist conservative oligarch authoritarians who also wanted to develop the country in their version of liberalism#there is something similar in Vic3 with Brazil but it was a phenomenon in all Latin America#the eurocentric oligarchy who wanted Progress but by imposing capitalist liberalist ideals and supressing democracy and socialism#and also lots of racism. lots of it.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

You should admit that you're a liberal because socialist liberalism is correct and good

I mean, I am a liberal in the sense that I think human rights and rule of law and democracy and free speech and freedom of religion and all that are good. Which is an idea I think a lot of leftists at least pay nominal lip service to! I'm not a liberal in that I don't think extending those ideas to the commercial sphere implies that laissez-faire capitalism is the best mode of production, or the most morally correct. I definitely am not a liberal in that I do not think capitalist parliamentary democracy is the only way to achieve these things, or that the best we can aspire to is to bolt on a thin layer of social democracy. Liberalism-as-she-is-practiced has a lot of ad-hoc exceptions and failures that make it incredibly frustrating you actually care about the values claimed to be central to liberalism, and the struggle to repair those issues seems to me to lead in an inexorably leftist direction.

Favoring workplace democracy and worker's ownership of the means of production (especially through structures like cooperates and nationalizing key industries like healthcare that are either public goods or an awkward fit for markets) certainly firmly puts me outside classical liberalism. I think market socialism is probably the most viable form of socialism given the whole calculation debate? There are also important critiques of the state specifically and of hierarchy generally that means a lot of anarchist writing really resonates with me. It's hard to be a dogmatic anarchist because we have so few examples of anarchist experiments in history (and most flourished only briefly under chaotic wartime conditions). But if I could choose what kind of society to live in and wave a magic wand so that it sprang into existence fully formed, an anarchist one would be very attractive!

#especially a techno-utopian one like in iain banks#i wanna have total morphological freedom and lots of weird sex

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

an example of german laissez-faire economic liberalism under an authoritarian government was the 1930–32 brüning administration. the early nazi privatization wave served the threefold purpose of freeing up state funds for things like remilitarization, bribing economic leaders to fall in line with the regime and transferring public services like welfare into the hands of party auxiliaries. after that though the regime undertook a program of steadily increasing state planning and regulation (again, mostly for the ends of rapid remilitarization), even including the nationalization of the salzgitter steelworks and two railways by the end of the 1930s, which expanded radically during the war into more and more complete state and party regimentation of the economy, despite significant earlier islands of ‘market freedom’ that had remained during the 1930s. nazi economic policy was pragmatic and never developed any very coherent and uniform doctrine but the one thing they were absolutely unambiguous about was that the interests of the state and nation should come before those of private capital. yes, despite having dramatically restricted the independence of big business by the end of the war, and to some extent breaking down the barriers and norms of the old social order (i would point out that the working-class presence in the ss was for a time proportionate to its share of german society as a whole, though arguably this promise of social mobility and upliftment was itself somewhat a heritage of liberalism), the nazis obviously never launched any sort of economic revolution which would have fundamentally challenged relations of production between workers and bosses. but calling them laissez-faire liberals seems deliberately contrarian and ignorant

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is my community college economics class capitalist propaganda? Serious question. Because the way it makes out the economy to be is that the best way forward for the economy is laissez-faire capitalism and that’s abhorrent to every fiber of my being. But also I need to get my degree so like I have to take the class.

All economics classes are capitalist propaganda

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poorly Summarized WIP Poll

I saw @blind-the-winds and so many others doing this tag game, and it looked like so much fun, so I decided to join in ^_^ Open tag as always for those who want to participate!!

Rules: Pick a bunch of your WIPs and summarize them as badly as possible, then ask your followers to vote on which one they'd be most likely to read. Multiple/all/none options are completely optional.

17 notes

·

View notes