#lower Miocene fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Crepidula Fossil Bivalve – Lower Miocene, Clallam Formation, Washington USA, Genuine Specimen

A genuine and well-preserved Crepidula fossil bivalve from the Lower Miocene epoch, approximately 16–20 million years old. This fossil was discovered in the Clallam Formation of Northwestern Washington, USA, an important geological unit known for preserving a diverse assemblage of marine molluscs.

The genus Crepidula, commonly known as slipper shells, is a marine gastropod mollusc (often mistaken for a bivalve due to its shell shape) with a distinctive internal shelf structure. This specimen reflects the shallow marine environments of the early Miocene in the Pacific Northwest.

Fossil Type: Gastropod (commonly called a slipper shell, not a true bivalve)

Genus: Crepidula

Geological Age: Lower Miocene (approx. 16–20 million years ago)

Formation: Clallam Formation

Depositional Environment: The Clallam Formation was deposited in a shallow, warm marine setting with good water circulation, supporting abundant marine life. The sediments include sandstone and siltstone beds that preserved mollusc shells in fine detail.

Morphological Features:

Convex outer shell with a smooth to slightly ridged surface

Internal “shelf” typical of Crepidula species visible in some specimens

Preservation may include original shell material or internal moulds

Notable:

Authentic specimen from the Clallam Formation, Washington State

A well-known genus with evolutionary and ecological interest

Ideal for fossil collectors, educators, and marine paleontology enthusiasts

Actual item shown – photo depicts the exact specimen you will receive

Authenticity: All of our fossils are 100% genuine natural specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity. The photo includes a 1cm scale cube for reference – please view the image for accurate sizing.

Add this genuine Crepidula fossil to your collection – a classic marine mollusc from the Lower Miocene seas of the Pacific Northwest, showcasing a beautifully preserved snapshot of ancient ocean life.

#Crepidula fossil#Miocene bivalve fossil#Clallam Formation fossil#Washington state fossil#fossil mollusc#fossil slipper shell#Crepidula fornicata#USA bivalve fossil#authentic fossil bivalve#collector fossil shell#fossil clam#lower Miocene fossil#Pacific Northwest fossil

0 notes

Text

Deinosuchus: Giant Alligator or something older?

I know the title sucks, I couldn't think of anything poetic or clever ok? Anyways, still catching up on croc papers to summarize and this one did make a few waves when it was published about a week ago.

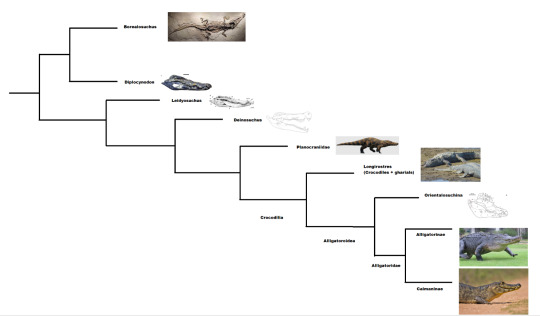

"Expanded phylogeny elucidates Deinosuchus relationships, crocodylian osmoregulation and body-size evolution" is a new paper by Walter, Massonne, Paiva, Martin, Delfino and Rabi, with quite a few of these authors having considerable experience with crocodile research. The thesis of the study is both simple and unusual. They suggest that several crocodilians traditionally held as stem-alligators, namely Deinosuchus, Leidyosuchus and Diplocynodon, weren't alligatoroids at all. In fact, if the study holds up they might not have been true crocodilians.

Ok, lets take a step back and briefly look at our main three subjects. Deinosuchus of course needs no introduction, a titan of the Cretaceous also known as the terror crocodile in some more casual sources, its easily one of the most iconic fossil crocodiles. It lived on either side of the Western Interior Seaway during the Campanian, fed on giant turtles and dinosaurs and with size estimates of up to 12 meters its easily among the largest crocodylomorphs who have ever lived.

Artwork by Brian Engh

Leidyosuchus also lived during the Campanian in North America and I would argue is iconic in its own right, albeit in a different way. It's historic to say the least and once housed a whole plethora of species, but has recently fallen on hard times in the sense that most of said species have since then been transferred to the genus Borealosuchus.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe

Finally there's Diplocynodon, the quintessential croc of Cenozoic Europe. With around a dozen species found from the Paleocene to the Miocene all across Europe, it might be one of the most well studied fossil crocs there is, even if its less well known by the public due to its relatively unimpressive size range.

Artwork by Paleocreations

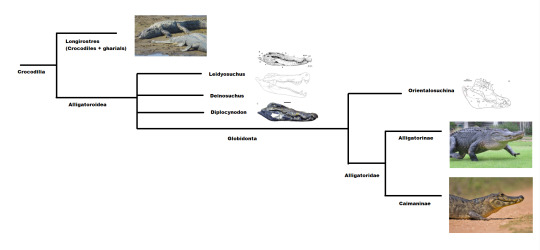

All three of these have traditionally been regarded as early members of the Alligatoroidea, one of the three main branches that form Crocodilia. In these older studies, Alligatoroidea can be broken up into three groups nested within one another. Obviously the crown is formed by the two living subfamilies, Alligatorinae and Caimaninae, both of which fall into the family Alligatoridae. If you take a step further out you get to the clade Globidonta, which in addition to proper Alligatorids also includes some basal forms with blunt cheek teeth as well as Orientalosuchina, tho jury's still out on whether or not they are truly alligator-relatives. And if you take a final step back and view Alligatoroidea as a whole, then you got our three main subjects neatly lined up outside of Globidonta in varying positions.

Below a highly simplified depiction of previous phylogenies. Deinosuchus, Leidyosuchus and Diplocynodon are often regarded as non-globidontan alligatoroids.

This new study however changes that long standing concensus. The team argues that several features we once thought defined alligatoroids are actually way more common across Crocodilia and even outside of it while also leverging some of the features of Deinosuchus and co. that have always been out of the ordinary. For instance, early alligatoroids are generally characterized as being comparably small, having had short, rounded heads, the afforementioned globular cheek teeth and of course the feature that still allows us to differentiate them from true crocodiles, the fact that they have a clear overbite. Now Leidyosuchus, Deinosuchus and Diplocynodon all have proportionally longer snouts than alligatoroids, their teeth interfinger like in crocodiles and most prominently (and namegiving for Diplocynodon) there is a large notch behind the snout tip that serves to receive two enlarged teeth of the lower jaw. These are of course just superficial examples, but if you wanna get into the nitty gritty check out the paper.

Below a simplified version of the papers phylogeny. Borealosuchus clades with Diplocynodon and Leidyosuchus and Deinosuchus are successive taxa. Planocraniidae are the sister to Crocodilia, which consists of Crocodyloids, Gavialoids (together Longirostres) and Alligatoroids.

Something also worth addressing in light of these results is salt tolerance in crocodilians and paleogeography. Basically, if you ignore Deinosuchus and co. (or well, just follow this new paper), then it is most likely that alligatoroids originated on the continent of Laramidia, i.e. the western half of America back when it was bisected by an enormous inland sea. Today, alligatoroids are famously intolerant of saltwater, yes, there are instances where alligators have been known to enter coastal waters, but its a far cry from what true crocodiles can achieve (just an example here's my recent post on Caribbean crocodiles). Given that alligatoroids don't appear on Appalachia, the other half of North America, until after the inland sea closes, this very much suggest that this intolerance goes way back. This has however always been at odds with Deinosuchus, which famously showed up along both the eastern and the western coast of the inland sea and at least lived close enough to the coast to leave its mark on the shells of sea turtles. We know it inhabited various near-shore environments and even stable isotope analysis of its teeth points towards it consuming either saltwater or prey that lives in the ocean. To a lesser degree its worth mentioning Diplocynodon, which though usually a freshwater animal has at least one species from coastal deposits. Now I do think its worth highlighting that just being salt tolerant doesn't necessarily mean they can't have been alligatoroids, given that salt glands could have easily been lost after Deinosuchus split off from other alligatoroids. Nevertheless, a position as a stem-crocodilian does add up with it being salt tolerant, with the assumption being that being tolerant to saltwater is basal to crocodilians as a whole and was simply lost in a select few lineages such as alligatoroids.

Given that its range spanned both coastlines of the Western Interior Seaway as well as direct evidence for interactions with marine life, Deinosuchus likely ventured out into the sea from time to time like some modern crocodiles.

There's also the matter of timing. When alligatoroids first appeared 82 million years ago, we already see the classic blunt-snouted morphotype with Brachychampsa and our dear giant Deinosuchus. Now if both were alligatoroids, this would suggest that they've been separate quite some time before that to bring forth these drastically different forms, yet attempts to estimate the divergence date suggest that they split no earlier than 90 million years ago. So if Deinosuchus is not an alligatoroid, then the timeline adds up a bit better. However I think the best example of this new topology really explaining an evolutionary mystery doesn't come from Deinosuchus, but from Diplocynodon. Those that know me might remember that I started working on researching Diplocynodon for Wikipedia, a process that's been slow and painfull both due to the 200 years of research history and the good dozen or so species placed in this genus. Tangent aside, one big mystery around Diplocynodon is its origin. They first appear in the Paleocene and survive till the Miocene, tend to stick to freshwater and oh yeah, species of this genus are endemic to Europe. Given that previous studies recovered them as alligatoroids, nobody was quite sure where Diplocynodon came from. Did they originate in North America and cross the Atlantic? Where they salt tolerant before and simply stuck to freshwater once in Europe? Or are they a much older alligatoroid lineage that entered Europe via Asia after having crossed Beringia. You know, the kind of headbreaking stuff we get when the fossil record is incomplete. But this new study recovers Diplocynodon as being closely related to the non-crocodilian Borealosuchus from the Cretaceous to Paleogene of North America. And that makes some sense, historically the two have been noted to be similar, hell there were even cases when Borealosuchus remains were thought to be North American examples of Diplocynodon. And Borealosuchus has the same double caniniforms as the other crocs we discussed so far. So when our three former alligatoroids got pushed outside of Crocodilia, Diplocynodon ended up forming a clade with Borealosuchus. And since Borealosuchus was wide spread in America by the late Cretaceous, and possibly salt tolerant, then it could have easily spread across Greenland and Scandinavia after the impact, giving rise to Diplocynodon.

The results of this study seem to suggest that Borealosuchus and Diplocynodon are more closely related that previously thought.

And since this is a Deinosuchus paper...of course theres discussion about its size. A point raised by the authors is that previous estimates typically employ the length of the skull or lower jaw to estimate body length, which might not be ideal and is something I definitely agree with. The problem is that skull length can vary DRASTICALLY. Some animals like early alligatoroids have very short skulls, but then you have animals in gharials in which the snout is highly elongated in connection to their ecology. Given that Deinosuchus has a relatively long snout compared to early alligatoroids, size estimates based on this might very well overestimate its length, while the team argues that head width would yield a more reasonable results. Previous size estimates have ranged from as low as 8 meters to as large as 12, which generally made it the largest croc to have ever existed. Now in addition to using head width, the team furthermote made use of whats known as the phylgenetic approach, which essentially bypasses the problem of a single modern analogue with peculariar proportions influencing the result. Now there is a bunch more that went into the conclusion, but ultimately the authors conclude that in their opinion, the most likely length for the studied Deinosuchus riograndensis specimen was a mere 7.66 meters in total length. And before you jump to any conclusions, DEINOSUCHUS WOULD HAVE GOTTEN BIGGER TRUST ME. I know having read "12 meter upper estimate" earlier is quite a contrast with the resulting 7.66 meters, but keep in mind this latter estimate is just one specimen. A specimen that in previous studies was estimated to have grown to a length of somewhere between 8.4 - 9.8 meters. Now yes, this is still a downsize overall, but also given that this specimen is far from the largest Deinosuchus we have, this means that other individuals would have certainly grown larger. Maybe not those mythical 12 meters, but still very large. So please keep that in mind.

Two different interpretations of the same specimen of Deinosuchus. Top a proportionally larger-headed reconstruction by randomdinos, bottom a smaller-headed reconstruction by Fadeno. I do not care to weigh in on the debate other than to say that size tends to fluctuate a lot between studies and that I'm sure this won't be the last up or downsize we see.

Regardless of the details, this would put Deinosuchus in the "giant" size category of 7+ meters, while early alligatoroids generally fall into the small (<1.5 meters) or medium (1.5-4 meters) size categories. The authors make an interesting observation relating to gigantism in crocs at this point in the paper. Prevously, temperature and lifestyle were considered important factors in crocs obtaining such large sizes, but the team adds to that the overall nature of the available ecosystem. In the case of Deinosuchus, it inhabited enormous coastal wetlands under favorable temperature conditions and with abundant large sized prey, a perfect combination for an animal to grow to an enormous size. And this appears to be a repeated pattern that is so common its pretty much regarded as a constant. To quote the authors, "a world with enormous crocodyliforms may have been rather the norm than the exception in the last ~ 130 million years." For other examples look no further than the Miocene of South America, the extensive wetlands of Cretaceous North Africa or even Pleistocene Kenya.

One striking example for repeated gigantism in crocodilians can be found in Miocene South America, when the caimans Purussaurus and Mourasuchus both independently reached large sizes alongside the gharial Gryposcuhus. The illustration below by Joschua Knüppe features some of the smaller earlier members of these species in the Pebas Megawetlands.

So that's it then, case closed. Deinosuchus and co aren't salt-tolerant alligators, they are stem-crocodilians. Deinosuchus was smaller than previously thought and Diplocynodon diverged from Borealosuchus. Leidyosuchus is also there. It all adds up, right? Well not quite. This all is a massive upheaval from what has previously been accepted and while there were outliers before, the alligatoroid affinities of these animals were the concensus for a long time. Future studies will need to repeat the process, analyse the data and the anatomical features and replicate the results before we can be sure that this isn't just a surprisingly logical outlier. Already I heard some doubts from croc researchers, so time will tell if Deinosuchus truly was some ancient crocodilian-cousin or if previous researchers were correct in considering it a stem-alligator. I for one will keep my eyes peeled.

#pseudosuchia#crocodylomorph#eusuchia#crocodilia#crocodile#alligator#deinosuchus#leidyosuchus#diplocynodon#palaeoblr#cretaceous#fossils#prehistory#extinct#long post#science news#croc#gator#borealosuchus#evolution

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ninoziphius platyrostris was an early beaked whale that lived during the late Miocene (~6 million years ago) in warm coastal waters covering what is now southwestern Peru. Its ancestors appear to have branched off from all other beaked whales very early in the group's history, indicating a "ghost lineage" going back to at least 17 million years ago.

About 4.4m long (~14'5"), it was less specialized for suction feeding and deep diving than modern beaked whales. Also unlike most modern species its jaws were lined with numerous interlocking teeth, with heavy wear suggesting it may have hunted close to the seafloor, where disturbed sand and grit would have regularly ended up in its mouth along with its prey and steadily ground down its teeth during its lifetime.

Males had a pair of stout tusks at the tip of their upward-curving lower jaw, with possibly a second smaller set of tusks behind them, which were probably used for fighting each other like in modern beaked whales.

Its shallow water habitat and more abrasive diet suggest Ninoziphius' lifestyle was much more like modern dolphins than modern beaked whales, and other early beaked whales like Messapicetus similarly seem to have occupied dolphin-like ecological niches.

These dolphin-like forms disappeared around the same time that true dolphins began to diversify, possibly struggling to compete for the same food sources, while other beaked whales that had begun to specialize for deep sea diving survived and thrived. Interestingly this ecological shift seems to have happened twice, in two separate beaked whale lineages – although only one of them still survives today – with bizarre bony "internal antlers" even independently evolving in both groups.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Bianucci, Giovanni, et al. "New beaked whales from the late Miocene of Peru and evidence for convergent evolution in stem and crown Ziphiidae (Cetacea, Odontoceti)." PeerJ 4 (2016): e2479. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2479

Bianucci, Giovanni, et al. A new Late Miocene beaked whale (Cetacea, Odontoceti) from the Pisco Formation, and a revised age for the fossil Ziphiidae of Peru. Bollettino della Societa Paleontologica Italiana 63.1 (2024): 21-43. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380459192_A_new_Late_Miocene_beaked_whale_Cetacea_Odontoceti_from_the_Pisco_Formation_and_a_revised_age_for_the_fossil_Ziphiidae_of_Peru

Gol'din, Pavel. "‘Antlers inside’: are the skull structures of beaked whales (Cetacea: Ziphiidae) used for echoic imaging and visual display?." Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 113.2 (2014): 510-515. https://doi.org/10.1111/bij.12337

Lambert, Olivier, Christian De Muizon, and Giovanni Bianucci. "The most basal beaked whale Ninoziphius platyrostris Muizon, 1983: clues on the evolutionary history of the family Ziphiidae (Cetacea: Odontoceti)." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 167.4 (2013): 569-598. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12018

Lambert, Olivier, et al. "No deep diving: evidence of predation on epipelagic fish for a stem beaked whale from the Late Miocene of Peru." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282.1815 (2015): 20151530. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1530

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ninoziphius#ziphiidae#beaked whale#odontoceti#toothed whale#cetacean#whale#artiodactyla#ungulate#mammal#art

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Mammalia - Diprotodontia

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our last order of marsupials, and possibly the first order of marsupials that comes to mind for most people, is Diprotodontia. Diprotodontia is the largest living order of marsupials, containing the families Phascolarctidae (“Koala”), Vombatidae (“wombats”), Burramyidae (“pygmy possums”), Phalangeridae (“brushtail possums” and “cuscuses”), Pseudocheiridae (“ringtailed possums” and kin), Petauridae (“trioks”, “gliders”, and kin), Hypsiprymnodontidae (“Musky Rat-kangaroo”), Macropodidae (“kangaroos”, “wallabies”, “tree-kangaroos”, “wallaroos”, “pademelons”, “quokkas”, and kin), and Potoroidae (“bettongs”, “potoroos”, and “rat-kangaroos”).

"Diprotodont" means “two front teeth”, and refers to the pair of large incisors on these animals’ lower jaws. Another characteristic of diprotodonts is "syndactyly": the second and third digits of the foot up to the base of the claws are fused, leaving the claws themselves separate. The fifth digit is usually absent, and the fourth digit is often greatly enlarged. This diverse marsupial order is restricted to Australasia, filling many of its large mammal niches. Most living diprotodonts are herbivores, though there are a few that are insectivorous or omnivorous.

Like other marsupials, diprotodonts give birth very early in gestation, and the newborns must crawl from their mothers vagina into her pouch and attach themselves to a teat. Mothers often lick their fur to leave a trail of scent for the newborn to follow to increase their chances of reaching the pouch. Joeys will finish their development within their mother’s pouch, eventually venturing out for short periods and returning to her pouch for warmth, protection, and nourishment until they are weaned. Diprotodonts usually only have one to two joeys at a time.

The earliest known fossil of Diprotodontia dates back to the Late Oligocene (23.03 - 28.4 million years ago), and the earliest identifiable species is Hypsiprymnodon bartholomaii from the Early Miocene. Many of the largest diprotodonts (along with a wide range of other Australian megafauna) became extinct when humans first arrived in Australia about 50,000 years ago.

Propaganda under the cut:

The name "wombat" comes from the now nearly extinct Dharug language spoken by the Dharug People, who originally inhabited the Sydney area. The spelling went through many variants over the years, including "wambat", "whombat", "womat", "wombach", and "womback", possibly reflecting dialectal differences in the Dharug language.

The primary defense of wombats is their toughened rear hide, with most of their posterior made of cartilage. When attacked, wombats dive into a nearby tunnel, using their rumps to block a pursuing attacker. There is an urban legend that wombats will sometimes allow an intruder to force its head over the wombat's back, and then use its powerful legs to crush the skull of the predator against the roof of the tunnel, but there is no evidence to support this.

Wombats are known for leaving distinctive cubic faeces. As wombats arrange these feces to mark territories and attract mates, it is believed that the cubic shape makes them more stackable and less likely to roll. It is not well understood how they produce feces in this shape!

Common Wombats (Vombatus ursinus) can be described as ecological engineers, as their burrow building results in soil turnover and aeration, which assists plant growth, and provides habitat for a range of different species, including insects, reptiles, rodents, echidnas, wallabies, and koalas.

The critically endangered Northern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii) is one of the rarest land mammals in the world, but thankfully their population is slowly rising thanks to dedicated conservation efforts. Classified as vermin and wiped out by farmers and feral predators, they were once considered extinct, but a population of about 30 individuals was discovered in the 1930s. Predator-proof fences were built around the wombat’s habitat in 2002, and insurance populations have been established in other locations. Today, there are over 400 total Northern Hairy-nosed Wombats.

The Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) (image 1) has the most effective insulating back fur of any marsupial and is resilient to wind and rain, while the belly fur can reflect solar radiation.

The word "koala" comes from the Dharug gula, meaning 'no water'. This is because koalas do not need to drink often, as they get enough water from their leafy diet (though larger males may additionally drink water found on the ground or in tree hollows).

The Koala has a good sense of smell, and it is known to sniff the oils of individual eucalyptus branchlets to assess their edibility.

Koalas possess unique folds in the velum (soft palate), known as velar vocal folds, in addition to the typical vocal folds of the larynx. These features allow the koala to produce deeper sounds that would otherwise be impossible for their size.

The Koala is classified as vulnerable, however, it is endangered in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales, and Queensland as of February 2022, due to climate-change-induced bushfires. There are concerns that these populations may not survive another round of heavy bushfires.

Female Coppery Brushtail Possums (Trichosurus johnstonii) tend to be dominant over males.

The Common Brushtail Possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) is an omnivore. While eucalyptus leaves are a significant part of its diet, it is also known to eat eggs, grubs, and even small mammals such as mice and rats.

The Common Brushtail Possum is one of few marsupials that thrive in cities and a wide range of natural and human-modified environments. Around human habitations, common brushtails are inventive and determined foragers with a liking for fruit trees, vegetable gardens, and kitchen raids.

The critically endangered Talaud Bear Cuscus (Ailurops melanotis) is endemic only to a few islands within the Talaud Islands, Indonesia. It is considered a “Cinderella Species,” one that is aesthetically appealing but generally overlooked and unknown by conservationists, researchers, and the public alike. The conservations that do know of its plight are working with local youths, traditional and religious leaders, and community members on Salibabu Island to change the perception of the species, which faces heavy pressures due to hunting and habitat loss. One of the best ways to support the cuscus, and other endangered animals like it, is through ecotourism. If tourists come to see the rare cuscus, while also supporting local businesses, the community will come to realize the economic benefit as well as the ecological benefit of the animal.

The endangered Woodlark Cuscus (Phalanger lullulae) is the largest mammal living on Woodlark Island, a part of the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. Its fur is marble-like, with a mix of white, dark brown, and ginger spots on its back and a white underbelly. No two Woodlark Cuscus have the same pattern.

The Common Spotted Cuscus (Spilocuscus maculatus) is typically shy, sluggish, and sloth-like in behavior. However, they can be very territorial, and fights, especially between competing males, can be aggressive and confrontational. If males encounter another male in their area, they make barking, snarling, and hissing noises, and stand upright to defend their territories. They will also scratch, bite, and kick potential predators.

The mouse-sized, critically endangered Mountain Pygmy Possum (Burramys parvus) is the only Australian mammal restricted to an alpine habitat. They feed on fruits, nuts, nectar, and seeds, but about a third of their diet consists of Bogong Moths (Agrotis infusa). These moths migrate to the high alpine mountainous regions during the Spring and Summer months. During these months, Mountain Pygmy Possums utilise Bogong Moths as their main food source. Scientists observed a catastrophic drop in Bogong Moth numbers in the summer of 2018–2019, due to climate-change-induced droughts in the moth's breeding areas. With the lack of moths as a food source during the breeding season, the possums lost litters due to inadequate nourishment. The possums are also threatened by habitat destruction and fragmentation, as well as predation by domestic cats and invasive red foxes. The construction of ski resorts in the alpine regions in which the mountain pygmy possums inhabit has been one of the greatest factors attributed to population decline. At Mount Higginbotham, a major road constructed to the Mount Hotham ski resort prevented male Mountain Pygmy Possums from migrating to the female nesting sites during the breeding season. This physical barrier was noted to markedly increase winter mortality in the Mount Higginbotham population. In response to this, a tunnel was constructed which provided male pygmy possums with an alternative migratory route.

Unusually for possums, Common Ringtail Possums (Pseudocheirus peregrinus) live a gregarious lifestyle which centres on their communal nests, called dreys. A communal nest is made up of an adult female and an adult male, their dependant offspring, and their immature offspring of the previous year. A group of Ringtail Possums may build several dreys at different sites. Ringtail Possums are territorial and will drive away any strangers from their nests.

The Honey Possum (Tarsipes rostratus) is a tiny possum which feeds on nectar and pollen. It is an important pollinator for the Candlestick Banksia (Banksia attenuata), Scarlet Banksia (Banksia coccinea), and the Coastal Jugflower (Adenanthos cuneatus).

Similar to an Aye-aye, the Striped Possum’s (Dactylopsila trivirgata) fourth finger is elongated and is used to detect and pull beetle larvae and caterpillars from tree bark.

The critically endangered Leadbeater's Possum (Gymnobelideus leadbeateri) was the 7,000th animal photographed for The Photo Ark by Joel Sartore.

Members of the Petaurus genus are popular in the exotic pet trade, and the Sugar Glider (Petaurus breviceps) is one of the most popular pet marsupials. However, recent evidence points to most captive gliders, at least in the United States, being Krefft's Gliders (Petaurus notatus), as they are thought to have been captured in West Papua. Either way, both glider species are wild animals that should not be kept as pets, and trade in gliders has a history of cruelty. They have complex needs which can not be adequately met in an individual’s home.

Feathertail Gliders (Acrobates pygmaeus) have fine skin ridges and sweat on their toes that allow their feet to function as suction cups, and they have even proven able to climb vertical panes of glass.

The evolution of tree-kangaroos is particularly convoluted. It appears that the animals were arboreal at some time in the far distant past, moving afterward to the ground and gaining long kangaroo-like feet in the process. Eventually they returned to the trees, where they further developed a shortening and broadening of the hind feet and a novel climbing method.

Bennett's Tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus bennettianus) are known to be very agile, able to leap 9 metres (30 ft) down to another branch, and have been known to drop as far as 18 metres (59 ft) to the ground without injury.

The endangered Dingiso (Dendrolagus mbaiso) is a tree-kangaroo which is sacred to the Moni People, seen as spirits of their ancestors.

The White-striped Dorcopsis (Dorcopsis hageni) feeds on the fruiting bodies of fungi and may play a part in spreading spores and thus maintaining healthy mycorrhizal communities in the forest.

The Rufous Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes hirsutus) was once widespread in the central and western deserts of Australia, but predation by domestic cats and red foxes, alongside destructive wildfires, caused the last wild population on mainland Australia to go extinct in the early 1990s. However, the mainland subspecies persisted in captivity, and have recently been reintroduced to predator-exclusion zones in the Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary and Dirk Hartog Island.

For the Anangu People, the Mala or "hare-wallaby people" are important ancestral beings. For tens of thousands of years, the Mala have watched over them from rocks and caves and walls, guiding them on their relationships with people, plants, and animals, and imparted rules for living and caring for country. Mala Tjukurpa, the Mala Law, is central to their living culture and celebrated in story, song, dance and ceremony.

The Western Grey Kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus) has the nickname “stinker” because mature males have a distinctive curry-like odour.

The highest ever recorded speed of any kangaroo was 64 km/h (40 mph) set by a large female Eastern Grey Kangaroo (Macropus giganteus).

Red-necked Wallabies (Notamacropus rufogriseus) are mainly solitary but will gather together when there is an abundance of resources. One study demonstrated that these wallabies are able to manage conflict via reconciliation, involving post-conflict reunions after low-intensity fights. However, the wallabies did not reconcile after high-intensity fights, showing that peace-making behavior was dependent on context.

The shy, nocturnal, endangered Black-flanked Rock-wallaby (Petrogale lateralis) lives in colonies and forms lifelong pair bonds, though females will mate with other males. Open relationship icons.

The shy, solitary Black Wallaroo (Osphranter bernardus), the tall and slender Antilopine Kangaroo (Osphranter antilopinus), and the Common Wallaroo (Osphranter robustus) may sometimes group together for safety, especially when gathering to drink at waterholes.

The largest known marsupial of all time was the giant, rhinoceros-sized Diprotodon, which lived 1.77 million to 40,000 years ago and was related to wombats and koalas.

The largest living marsupial, and the largest terrestrial mammal native to Australia, is the Red Kangaroo (Osphranter rufus). Large mature males can stand more than 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) tall to the top of the head in upright posture, with the largest confirmed one having been around 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) tall and weighing 91 kg (201 lb). However, the average Red Kangaroo stands approximately 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall.

Red Kangaroos have been observed to engage in alloparental care, a behaviour in which a female may adopt another female's joey.

#lots of propaganda cause there are so many of these guys and I wanted to get a wide spread this took me hours rip#animal polls#round 3#mammalia

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miochelidon eschata Volkova, 2024 (new genus and species)

(Type coracoid [shoulder bone] of Miochelidon eschata [scale bars = 2 mm], from Volkova, 2024)

Meaning of name: Miochelidon = Miocene swallow [in Greek]; eschata = distant [in Greek]

Age: Miocene (Burdigalian), about 16.3–16.5 million years ago

Where found: Tagay Formation, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia

How much is known: A partial coracoid (shoulder bone) and ulna (forearm bone). It is unknown whether both bones belonged to the same individual.

Notes: Miochelidon was a swallow. It represents the oldest fossil swallow known, but it is unclear which modern swallow species it is most closely related to.

Reference: Volkova, N.V. 2024. The oldest swallow (Aves: Passeriformes: Hirundinidae) from the upper lower Miocene of Southeastern Siberia. Doklady Biological Sciences advance online publication. doi: 10.1134/S0012496624600258

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

A worn fossilized shark tooth of a great white shark, or Carcharodon carcharias from the Naarai Formation in Cape Nagasakibana, Choshi City, Chiba, Japan. Fossils from this deposit are between the Upper Miocene to Lower Pliocene in age. The Japanese name for this world famous shark is "hohojirozame" which literally translates to "white-cheeked shark" (not the confused with the whitecheek shark, Carcharhinus dussumieri).

#fish#shark#chondrichthyan#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#carcharodon#great white shark#miocene#pliocene#cenozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#ホホジロザメ#カルカロドン#ネズミザメ科#サメ#化石#古生物学

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the earliest known felid? Like at what point do scientists determine that this beast can now be roughly called a Cat?

the diagnostic criteria for what makes a cat a cat is a little murky toward the earlier end of the lineage, partially because the specimens of animals this old tend to be very fragmentary and partially because evolution from Not Cat into Cat was a very slow gradient. it’s hard to draw a line through one specific period of their evolution and call it a taxonomic boundary, since there isn’t really any rhyme or reason as to why certain traits evolve other than It Works Good. however, a few generally accepted requirements for an animal to be a felid (true cat) are as follows:

-digitigrade (toe walking) stance, wherein the heels of the feet do not touch the ground most of the time while the animal walks.

-fully protractile claws that, when relaxed, sit safely inside the digit’s flesh and off the ground. when they are needed, the claws are actively extended out through the use of flexor muscles.

-three-lobed paw pads that form a vaguely triangular shape, with the middle lobe sitting more forward than the side lobes.

-thirty teeth, with the upper third premolar and the lower molar modified into carnassial teeth for meat processing.

-no sweet taste receptors (tragic)

-rough, sandpaper-like tongue papillae used for self grooming and for scraping meat off of bones.

obviously, a lot of these features can’t be preserved in fossils, so complex probability and ratio formulas need to be used to speculate about what an animal may have been like when it was alive. despite these challenges, the earliest agreed upon true cat is generally accepted to be proailurus lemanensis, aka “leman’s dawn cat”. pro is the greek prefix for “before”, and ailuros is greek for cat.

proailurus as a whole genus is known from between 30.8-25 million years ago in oligocene/miocene eurasia. most species were small, only weighing around 20lbs (though some species could get as large as clouded leopards at around 50-60lbs). they had big eyes and long tails like modern arboreal cats, and were likely nocturnal and spent at least some of their lives up in the trees.

the genus proailurus had an entire subfamily named after it, the proailurinae, of which there are no living members.

the cat lineage can be divided into four subfamilies. proailurinae (first cats), machairodontinae (saber cats), felinae (little cats), and pantherinae (big cats). unfortunately, both proailurinae and machairodontinae have no living members, but these early cat dynasties paved the way for felids to become dominant hypercarnivores in almost every biome! may they rest well-remembered <3

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zealanditheria: an island of misfits

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Miocene… for now)

Zealanditherium worthyi by Dylan Bajda.

In our world, the Saint Bathans Fauna provided a mandible and femur belong to a non-therian mammal, on the Miocene of New Zealand. In our world, this was merely a curiosity of time, as these unique creatures did not make it past to our present. But in this timeline, they achieved dominance over the island continent of Aotearoa.

Most of their anatomy here is inferred. Like other non-therian mammals they presumably had tarsal spurs, a cloaca, a two-headed penis and epipubic bones. Therefore, this will inform how these animals are depicted in this project. What were do know from our few fossils is that they had an erect gait and proeminent incisors and canines on the lower jaw.

Because New Zealand’s terrestrial fossil reccord is restricted so far to the mid-Miocene, we’ll discuss forms from the Saint Bathans formation for now.

Around 45 species are known, ranging in size from small shrew like forms to heavy one ton herbivores, taking the ecological niche of the moa in our timeline. A leopard sized apex predator, Reparo whiro, dominated as the top carnivore of this assemblage. On the trees, five forms similar to opossums took the canopies, while on the ground long tailed herbivores demonstrated rabbit-like saltitation. In the waters, the otter-like Waitoreke anciens hunted for fish, alongside otter-like dagontheriid multituberculates.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underground River

Puerto Princesa City,

Palawan, Philippines

The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP) according to Palawan Provincial Government, is one of the most important protected areas of the Philippines. It features a spectacular limestone or karst landscape with one of the most complex cave systems. It contains an 8.2 km long underground river that flows directly to the sea. The lower half of the river is brackish and is affected by the ocean’s tide. An underground river directly flowing into the sea, and the associated tidal influence, makes it a significant natural phenomenon. The discovery of at least 11 minerals, crystal and egg shape rock formations, and a 20 million year old Miocene age serenia fossil in the cave further add to its scientific value. The Puerto Princesa Underground River is declared as one of the New 7 Wonders of Nature.

The PPSRNP contains a full mountain to the sea ecosystem and protects forests, which are among the most significant in Asia. It represents significant habitat that is important for biodiversity conservation.

In recognition of the PPSRNP’s globally significant natural value, it was inscribed to the List of World Heritage Sites on December 4, 1999. Inscription on the list confirms the outstanding universal value of the Park and its well integrated state of conservation.

The PPSRNP is managed by the City Government of Puerto Princesa based on a program centered on environmental conservation and sustainable development. It has the distinction of being the first national park devolved and successfully managed by a Local Government Unit.

It is managed by the City thru a Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), multi-sector body that provides policy direction and other oversight functions. It is a model for effective protected area management and sustainable tourism in the Philippines.

The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park is a source of pride, and a key element in the identity of the people of Puerto Princesa in particular, and of the Philippines as a whole. The conservation of the Park is a symbol of commitment by the Filipino people in the global efforts to conserve our natural heritage.

0 notes

Text

komodo dragon evolution

Ancestors of the Komodo Dragon

The Komodo dragon is an ancient reptile belonging to the Varanidae family. Scientists believe that their ancestors can be traced back tens of millions of years and share a common ancestry with the giant lizards of the dinosaur era. Fossil evidence shows that Varanidae existed in the Miocene (about 25 million years ago) and evolved in various forms in different environments.

The direct ancestors of the Komodo dragon may have originated in Australia, and then with changes in sea level and crustal movement, they spread to the Indonesian archipelago and eventually thrived on Komodo Island and its surrounding islands. Due to the lack of large carnivorous mammals in the area, the Komodo dragon gradually became the top predator on the island and dominated the ecosystem.

Evolutionary characteristics adapted to the island environment

The Komodo dragon has evolved a variety of unique physiological characteristics to adapt to the needs of survival in the isolated island environment. First, they are huge, growing up to 3 meters long and weighing more than 70 kilograms. This phenomenon of "largeness" is called "Island Gigantism", which is mainly caused by the lack of competitors and stable food sources.

Second, Komodo dragons have an extremely keen sense of smell and can detect the smell of prey from several kilometers away. They contain poison glands in their mouths, and the venom they secrete can lower the blood pressure of prey and cause shock, allowing them to easily prey on animals larger than themselves, such as deer and wild boars.

In addition, the reproduction method of Komodo dragons is also quite special. Female individuals can reproduce through parthenogenesis, and even without male mates, they can give birth to the next generation under certain circumstances. This feature greatly improves their chances of survival in island environments with limited resources.

Human Impact and Modern Conservation

Despite the evolutionary success of the Komodo dragon, modern human activities pose a threat to its survival. Habitat destruction, poaching, and rising sea levels caused by climate change have all had an adverse impact on the future of the Komodo dragon. Currently, the Komodo dragon has been listed as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and is strictly protected by the Indonesian government.

At the same time, Komodo Dragon Sculpture has also become an important art form to show the charm of this ancient creature. Many zoos, museums and artists have created exquisite Komodo dragon sculptures to remind people to pay attention to the survival status of this legendary creature and pass on its natural beauty through art.

The Future of Komodo Dragon

The evolution of the Komodo dragon is a model of adaptation to environmental changes, but in the face of modern ecological challenges, their future is still full of uncertainty. Humans must ensure that this ancient creature will not disappear from the earth through scientific research and ecological protection measures. At the same time, Komodo Dragon Sculpture will continue to serve as a combination of art and nature, reminding people to protect these magical creatures and let their legends continue to be passed on.

0 notes

Text

Taylor & Francis publications 27th July 2023- 1st August 2023

There have been a lot of interesting documents released between 27th July-1st August on the Taylor & Francis website; i decided to include the released papers' doi here.

Feel free to read them if you are interested, i have marked the papers available free to read and the others that require payment. (open access = Blue, payment required = red)

Copy the doi link or title into your search engine and you should be brought to the document.

A new amphibamiform (Temnospondyli: Branchiosauridae) from the lower Permian of the Czech Boskovice Basin

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2231994

A fossil viper (Serpentes: Viperidae) from the Early Pleistocene of the Crimean Peninsula

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241059

Unusual cystoporate? bryozoan from the Upper Ordovician of Siljan District, Dalarna, central Sweden

doi.org/10.1080/11035897.2023.2223579

Early Devonian Ostracoda from the Norton Gully Sandstone, southeastern Australia

doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2023.2223658

Eocene Araucariaceae in Europe: additional evidence from a new Baltic amber species of the genus Oxycraspedus Kuschel, 1955 (Coleoptera: Belidae)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237984

Skeletal taphonomy of the water frogs (Amphibia: Anura) from the Pit 7/8 of the Pliocene Camp dels Ninots site (Caldes de Malavella, NE Spain)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237998

Tapejarine pterosaur from the late Albian Paw Paw Formation of Texas, USA, with extensive feeding traces of multiple scavengers

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241044

The first American occurrence of Phoenicopteridae fossil egg and its palaeobiogeographical and palaeoenvironmental implications

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241050

Eocene (Ypresian-Lutetian) mammals from Cerro Pan de Azúcar (Gaiman, Chubut Province, Argentina)

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241054

Turtle tracks from the middle Jurassic Yaopo formation in Beijing, China

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2241064

The earliest occurrence of Equus in South Asia

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2227236

Early Cretaceous radiation of teleosts recorded by the otolith-based ichthyofauna from the Valanginian of Wąwał, central Poland

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2232008

A stem therian mammal from the Lower Cretaceous of Germany

doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2023.2224848

Vertebrate ichnology and palaeoenvironmental associations of Alaska’s largest known dinosaur tracksite in the Cretaceous Cantwell Formation (Maastrichtian) of Denali National Park and Preserve

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2221267

Biostratigraphical and paleoenvironmental studies of some Miocene‒Pliocene successions in Northwestern Nile Delta, Egypt

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2231978

Hyena and ‘false’ sabre-toothed cat coprolites from the late Middle Miocene of south-eastern Austria

doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2237979

Source:

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Platybelodon was previously believed to have fed in the swampy areas of grassy savannas, using its teeth to shovel up acquatic and semi-aquatic vegetation. However, wear patterns on the teeth suggest that it used its lower tusks to strip bark from trees, and may have used the sharp incisors that formed the edge of the "shovel" more like a modern-day scythe, grasping branches with its trunk and rubbing them against the lower teeth to cut it from a tree. Adult animals in particular might have eaten coarser vegetation more frequently than juveniles."

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Blender 3.3 LTS on Linux Mint 20.3

#platybelodon

#3d #blender3d #paleoart #art #sculpting #scultura #sculpture #actionfigure #modellismo #model #blender3d #Linux #debian #animals #preistoria #prehistoric #proboscidea #miocene #asia #caucaso #fossil #bones #skeleton

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Insular Sebecids of the Caribbean

Still catching up with posts I need to write given that the past two weeks were just major paper after major paper. Given that the last two I did were on the recently named sebecoid Tewkensuchus (more here) and on the unrecognized diversity that slumbers among modern American crocodiles (see here), it sure would be convenient if there was one that sorta ties into both of those....

Oh yeah, what convenient timing for "A South American sebecid from the Miocene of Hispaniola documents the presence of apex predators in early West Indies ecosystems", written by Lázaro W. Viñola López and colleagues and published literally just last night as of the time I'm writing this.

What's this paper about? Simple, the description of sebecid fossil remains from the island of Hispaniola. Sebecids of course being terrestrial crocodile relatives that lived throughout much of the early Cenozoic in South America. The remains admittedly aren't anything to write home about, consisting of two vertebrae and a tooth with the group's iconic blade-like serrated morphology (aka ziphodonty), but the implications are nonetheless quite interesting. Not only is it the best evidence we have for insular sebecids and would have been the islands apex predator, but it also extends the survival of Sebecidae by perhaps up to 5 million years. This means the group might have survived until the Early Pliocene.

The Hispaniola sebecid, tentatively assigned to Sebecus sp., as illustrated by Machuky Paleoart

Now full disclosure, these remains are NOT the first evidence of what could be sebecids from the Caribbean. Previous discoveries include teeth from the early Miocene of Cuba as well as the early Oligocene of Puerto Rico. However, what makes the Hispaniola remains so much more important is surprisingly the presence of vertebrae. Hear me out. Sure, the teeth are iconic and easily identifyable, however, ziphodont teeth are not unique to sebecids and have also evolved independently in more "modern" crocodiles such as planocraniids and mekosuchines. Sure, mekosuchines were definitely not hanging out on Hispaniola and planocraniids are accepted to have died out during the Eocene, but nonetheless this means that ziphodont teeth could also belong to another type of croc. HOWEVER, the vertebrae from Hispaniola are described as amphicoelous, while animals closer to todays crocs would have procoelous vertebrae. Ergo, ziphodont teeth + amphicoelous vertebrae = sebecid, making these remains the first unambiguous evidence for Caribbean sebecids.

A simplified phylogeny showing the repeated evolution of ziphodont teeth in crocodyliforms while also highlighting the diferences in notosuchian and eusuchian vertebrae.

Case and point for why thats important? Well while the remains from Cuba and Puerto Rico are most likely also sebecids based on their age and geography, there are even older fossil remains of a ziphodont croc from the Middle Eocene of Jamaica. While sebecids were already around back then, so were the planocraniids, hooved crocodile-relatives found across North America and Eurasia. And since Eocene Jamaica has faunal similarities with North America, this particular ziphodont is more likely to be a planocraniid than a sebecid.

While the Cuban and Puerto Rican teeth are likely those of sebecids, the Eocene Jaimacan ziphodont croc could have easily been a planocraniid similar to the widespread genus Boverisuchus, illustrated here by Corbin Rainbolt.

Those that read my post on Tewkensuchus might remember my barely coherent ramblings about how confusing and poorly understood the paleogeography of sebecids is. Well for what its worth, if we ignore all the chaos caused by Europe's part in the equation, the South American history is relatively straight forward. The Paleogene record spans both remains found in the far South as well as Eocene records further north at lower latitudes. It's not entirely clear how sebecids got to the islands, but it is speculated that they could have rafted or even traveled across temporary land bridges that formed at times of lower sea levels. Whatever the case, by the early Oligocene sebecids seem to have made it to Puerto Rico and would have likely been isolated from the mainland and from other island populations when various marine passages opened, splitting the island chains. This may have been a blessing in disguise, as by the Miocene sebecids were restricted to tropical environments at low and mid latitudes and further habitat collapse, tied in part to the disappearance of the Pebas Mega Wetlands, eventually lead to their extinction on the mainland by the early Late Miocene.

But if the fossils from Hispaniola are anything to go by, then they clung onto life for another 5 million years in the Caribbean, retaining their spot as the islands apex predators until possibly as late as the Early Pliocene. Alas, they couldn't evoid extinction forever and unless we find even younger remains the Hispaniola sebecid represents the last hold out of the once diverse group Notosuchia.

Predator guilds and their distribution in South America throughout the Paleogene (a), Neogene (b) and late Quaternary (c).

But in a way, they didn't go without leaving their mark on the island. After sebecids went extinct, there seems to have been a push by native birds towards more terrestrial life, with some species losing the ability to fly alltogether. Some birds of prey seem to have taken up the mantle of terrestrial predator, leading to owls like Ornimegalonyx on Cuba and even the only distantly related Cuban crocodile threw its hat into the ring when it came for the spot of apex predator.

Top: A cuban crocodile hunting a small species of ground sloth, illustrated by Manusuchus Bottom: A general overview of the fauna found on Cuba during the Pleistocene, including flightless birds, cuban crocodiles and terrestrial owls, illustrated by Joschua Knüppe

#sebecidae#sebecus#sebecosuchia#notosuchia#pliocene#palaeoblr#prehistory#croc#crocodile#cuban crocodile#planocraniidae#pseudosuchia#long post#science news

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kogiopsis floridana was a physeteroid whale that lived near the coast of the southeastern United States from the mid-Miocene to the early Pliocene, about 14-4 million years ago.

Known just from fossilized lower jaws and teeth, with some teeth up to nearly 13cm long (~5"), its full life appearance and size are uncertain – but it may have been slightly larger than a modern bottlenose dolphin at around 4.5m long (~14'9"). It's traditionally been considered to be part of the kogiid family, closely related to modern pygmy and dwarf sperm whales, but some studies disagree with that classification and instead place it in the true sperm whale lineage.

It was probably a predator in a similar ecological role to modern orcas, adapted for hunting prey like squid, fish, and smaller marine mammals. But unlike orcas it wouldn't have been the apex predator of its ecosystem, subject to predation pressure by even larger carnivores like macroraptorial sperm whales and everyone's favorite ridiculously huge shark – and as a result it probably had a "live fast and die young" lifestyle similar to modern kogiids and other small-to-medium-sized Miocene physeteroids, rapidly maturing and only living to around 20 years old.

I've reconstructed Kogiopsis here as a kogiid-like animal, with a similar sort of shark-like head shape and "false gill" markings. In the background a second individual is depicted displaying "inking" behavior, releasing a defensive cloud of reddish-brown fluid from a specialized sac in its colon.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#kogiopsis#kogiidae#maybe#physeteroidea#odontoceti#toothed whale#cetacean#whale#whippomorpha#artiodactyla#ungulate#mammal#art#speculative behavior#inking#convergent evolution

224 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Is an extinct species of mackerel shark that lived approximately 23 to 3.6 million years ago (Mya), from the Early Miocene to the Pliocene epochs. It was formerly thought to be a member of the family Lamnidae and a close relative of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). However, it is now classified into the extinct family Otodontidae, which diverged from the great white shark during the Early Cretaceous. While regarded as one of the largest and most powerful predators to have ever lived, the megalodon is only known from fragmentary remains, and its appearance and maximum size are uncertain. Scientists differ on whether it would have more closely resembled a stockier version of the great white shark, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) or the sand tiger shark (Carcharias taurus). The most recent estimate with the least error range suggests a maximum length estimate up to 20 meters (66 ft), although the modal lengths are estimated at 10.5 meters (34 ft). Estimates suggest that a megalodon about 16 meters (52 ft) long weighs up to 48 metric tons (53 short tons), 17 meters (56 ft) long weighs up to 59 metric tons (65 short tons), and 20.3 meters (67 ft) long (the maximum length) weighs up to 103 metric tons (114 short tons). Their teeth were thick and robust, built for grabbing prey and breaking bone, and their large jaws could exert a bite force of up to 108,500 to 182,200 newtons (24,400 to 41,000 lbf). Megalodon probably had a major impact on the structure of marine communities. The fossil record indicates that it had a cosmopolitan distribution. It probably targeted large prey, such as whales, seals and sea turtles. Juveniles inhabited warm coastal waters and fed on fish and small whales. Unlike the great white, which attacks prey from the soft underside, megalodon probably used its strong jaws to break through the chest cavity and puncture the heart and lungs of its prey. The animal faced competition from whale-eating cetaceans, such as Livyatan and other macroraptorial sperm whales and possibly smaller ancestral killer whales. As the shark preferred warmer waters, it is thought that oceanic cooling associated with the onset of the ice ages, coupled with the lowering of sea levels and resulting loss of suitable nursery areas, may have also contributed to its decline. A reduction in the diversity of baleen whales and a shift in their distribution toward polar regions may have reduced megalodon's primary food source. The shark's extinction coincides with a gigantism trend in baleen whales.

Carnivore

Megalodon (c) The Meg Art (c) reneg661

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dryornis hatcheri Degrange, 2022 (new species)

(Type humerus of Dryornis hatcheri [scale bars = 1 cm], from Degrange, 2022)

Meaning of name: hatcheri = for John B. Hatcher [collector of the original fossil]

Age: Miocene (Burdigalian)

Where found: Santa Cruz Formation, Santa Cruz, Argentina

How much is known: A partial left humerus (upper arm bone).

Notes: D. hatcheri was an American vulture. The type specimen was originally collected in 1899 and thought to have come from a phorusrhacid (terror bird), an assignment that is now considered unlikely given that phorusrhacids were generally flightless birds with very reduced wings. Although the fossil is very fragmentary, it exhibits characteristic features of the genus Dryornis. The only other species of Dryornis that had been previously named was the younger D. pampeanus from the Pliocene of Argentina. Whereas D. pampeanus was the largest known American vulture (estimated as having weighed around 26 kg), D. hatcheri was probably smaller than extant condors, albeit still bigger than most other American vultures.

Reference: Degrange, F.J. 2022. A new species of Dryornis (Aves, Cathartiformes) from the Santa Cruz Formation (lower Miocene), Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2021.2008411

38 notes

·

View notes