#ngram viewer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

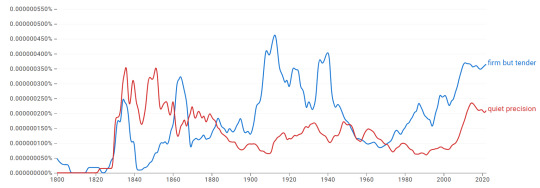

So, Google has this thing called ngram viewer. It searches books for words or phrases to see how common they've been over time. (https://books.google.com/ngrams/info) To save space I threw both "firm but tender" and "quiet precision" in to see what their usage over time looks like. https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=firm+but+tender%2C+quiet+precision&year_start=1800&year_end=2022&corpus=en&smoothing=3

The X-axis is what percentage of 3 word phrases/2 word phrases these make up of the available books from the years on the Y-axis.

There's a post going around about a specific alleged AI fanfic. The author of the post lists a lot of reasons why they believe the fic is AI. Not linking to the post and not commenting on its conclusion, but.

But.

People.

These???? Are all ABSOLUTELY VALID analogies/expressions???

"her nimble fingers worked with quiet precision"

"his grip firm but tender"

"her gown pooling around her like embers"

But the post says that:

fingers don't make sound, so what does quiet precision mean? as opposed to what? her joints cracking with every movement? how is a grip firm but tender? what does that mean? since when do embers pool? the entire fic is littered with these adjectives that contradict each other or just straight up do not make sense, because all an ai does is generate descriptive language with no understanding of what the words it's spitting out actually mean

Come on, man. These are perfectly serviceable! Quiet precision and firm but tender are bog standard fictional expressions. Granted, I've never seen the simile of a dress pooling like embers, but I like it! It evokes!

They are absolutely something that an actual living breathing person would write! (In fact they're so serviceable that if the fic is AI they're probably plagiarised) (although firm but tender is SO common I'm not sure it can be plagiarised? It's like 'toeing off his shoes').

Like, yeah, AI sucks. I agree it sucks.

But analogies or expressions that aren't a one to one match for truth (reality? observable fact? whatever, you get what I mean) are not bad?? They don't mean a fic was written with AI?? They're what makes writing GOOD. Makes it interesting.

Sure, 'her nimble fingers moved like bones and tendons covered by skin because they were bones and tendons covered in skin, but her movements were so expertly precise that no one noticed just how super precise they were' might be entertaining. briefly.

But the whole POINT of metaphor and simile is to evoke a reaction. An emotion.

There's a post by silentwalrus that I cannot find (thanks tumblr search), and it's pissing me off, because they perfectly talked about this! About metaphor and how to write original and effective ones (something they're VERY good at). The example was something like 'he did a thing like a scorpion hidden under a bush' and pointing out that if you looked at it too close it didn't make sense, but it evoked a reaction.*

A clever or strange or evocative analogy or expression does not mean it was written by AI.

____________________________

*I may be misremembering the details, and if so I apologise; it was a long time ago, but I'm positive it involved a scorpion.

#ngram viewer#it's super useful for looking at language trends#but also at shifts in spelling#you can also throw in names#there are ways to restrict or expand the search#basically if you like language this is a fun toy#I use it for editing when I want to know which version of a word that has multiple accepted spellings is the best one

919 notes

·

View notes

Text

god, I love leftovers. Thank you, refrigerators and freezers, microwaves, etc., for the ability to make one of the five dishes I willingly consume and eat it the entire goddamn week.

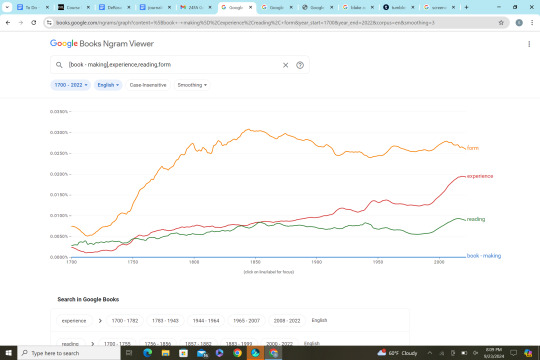

#refrigerator appreciation post#freezer appreciation post#I wrote a whole list of questions I have about the development of the concept of “leftovers” but I scrapped it because too goddamn long#like no one wants to hear me ask a bunch of questions I could answer but won't because that requires finding and reading research or source#because I can't let myself be inaccurate can i#no I am compelled to be as accurate as possible in my dumbass rabbithole expolorations and that takes too many characters#I had two screenshots of the Google Ngram Viewer

0 notes

Text

Fun fact "epilept" as a noun for an epileptic person seems almost wholly unattested; it has no Wiktionary entry and, looking a Google ngram viewer, there are a tiny number of occurrences of the word "epilept" in books and none of them seem to be using it as a noun (for example, many are just citing it as a Greek root). Now, my powerful Language Organ with a deep grasp of English grammar knows that, if you wanted a slightly outdated and non-PC sounding term for "epileptic person", "epilept" is what you would go with. Even kind of makes you sound like a prophet or some kind of psychic. So I've introduced it to this discursive ecosystem but I just want you all to know I deserve credit for this shit.

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

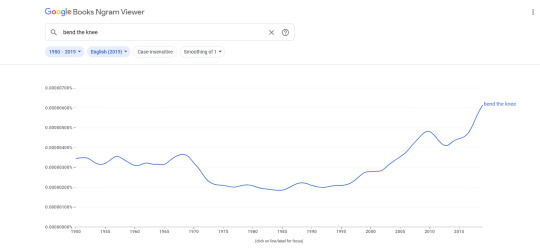

I'm not sure it's as clear cut as all that. I think you've run into an issue with case sensitivity. Using "bend the knee", no caps:

Using the case-insensitive option:

There, the orange line for "Bend the Knee", that's the big bump you have. (Though far less huge with a more comparative vertical scale.)

There is a distinct rise in the use of the expression around the time of the show's start, but it was popularly used well before that.

The expression "bend the knee" certainly existed long before ASoIaF. But since the first book was published on 06 August 1996 its use in English has soared.

Google Books Ngram Viewer, of course, only covers books. So there was a dip after the publication of A Dance of Dragons in 2011. Though because of the HBO series the expression has entered the general lexicon and is being used by people who've neither read ASoIaF nor seen GoT. So as of 2019, the current end date of Ngram searching, it was moderately trending upwards again.

The mass worldwide web, at least Net 1.0, began around 1995. That's slightly before the time A Game of Thrones was published. So there's not much data prior to its publication to compare online use of "bend the knee" before its release and after. But use of the phrase is now extremely common – particularly in political discussions. Mainstream legit news media use it unselfconsciously.

It seems to be used particularly often in connection with a certain US political figure.

However, with several criminal cases facing him this year, another GoT phrase may apply to him: Winter is Coming for Donald Trump.

#that vertical scale is a hell of a thing#asoiaf#grrm#bend the knee#expressions#politics#google books ngram viewer#infographics#interesting stuff#queue and me we're in this together now

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

It wasn’t so long ago that respectable psychologists didn’t really talk about “brainwashing.” The term had the slightly kitschy flavor of other Cold War embarrassments—C.I.A. spy cats and Reds-under-the-bed paranoia. But Google’s indispensable Ngram Viewer, which analyzes how frequently phrases appear in printed texts, confirms that the past two decades have seen an uptick in the word’s usage. What’s bringing brainwashing back?

One potential answer is the rise of technologies suspected of having mind-controlling powers, chief among them social media. Another is the entrenched political polarization of our time. When the cousin you kicked a soccer ball around with as a child starts spouting unhinged certainties about viruses, vaccines, and climate change—beliefs he treats as beyond debate—you might wonder: What happened to him? This isn’t just an ordinary disagreement. Could he have been . . . brainwashed?

Don’t get smug; he’s wondering the same thing about you. A few years ago, Psychology Today posted a checklist under the headline “Your Friend Might Be Politically Brainwashed If . . .” The last item on the list: “They assume that everyone who disagrees with them must be brainwashed.” So wait—does entertaining the possibility of having been brainwashed mean that you haven’t been? Or is that too easy?

Several recent books have taken up the subject of brainwashing—among them Daniel Pick’s “Brainwashed: A New History of Thought Control” (Profile), Joel E. Dimsdale’s “Dark Persuasion: A History of Brainwashing from Pavlov to Social Media” (Yale), and Andreas Killen’s “Nervous Systems: Brain Science in the Early Cold War” (HarperCollins). They share a scholarly squeamishness about the word they are forced to use for their subject matter. “Yes, the term brainwashing is silly and unscientific,” Dimsdale writes. “No one ever meant it literally, but the metaphor is a powerful one.”

In the new book “The Instability of Truth: Brainwashing, Mind Control, and Hyper-Persuasion” (Norton), Rebecca Lemov, a historian of science at Harvard, takes a different approach. She is often asked, she says, whether brainwashing really exists. “The answer is yes,” she writes, without any it-depends-what-you-mean-by hedging. In fact, she continues, “what we call brainwashing is not rare but common.”

Of course, words like “brainwashing” have no fixed meaning independent of their usage, which can be imprecise and expansive. When Frantz Fanon wrote of colonial efforts at lavage de cerveau in Algeria, or when a commentator in the seventies accused President Richard Nixon of having “brainwashed” white workers into fearing Communist infiltration, the word was gesturing at something, however loosely defined.

Yet the term’s recent resurgence raises suspicions. Accusations of brainwashing aren’t neutral claims; they offer a particular explanation for why someone holds beliefs we find preposterous. That explanation attributes those beliefs to deliberate manipulation instead of rational argument or personal conviction. In doing so, it may recast those with “deplorable” beliefs as victims rather than agents, deserving of not just condemnation but sympathy—and, perhaps, treatment. In the seventies heyday of the cults, that treatment was called “deprogramming.” Is this what our addled cousins need? A systematic re-indoctrination into conventionality?

The earliest appearances of the concept “brainwashing,” Lemov writes, occurred in the mid-twentieth century, in the files of the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor of the C.I.A. The term came to prominence owing in large part to the writings of an American journalist named Edward Hunter. He claimed that it was a rendering of a Chinese phrase, but it may have been, as he elsewhere claimed, a coinage of his own to describe Chinese persuasion techniques.

These techniques were most famously applied during the Korean War. As a prisoner of war, Morris R. Wills faced a gamut of privations—he was left malnourished and consigned to filthy conditions amid the ever-present threat of execution. Horror alternated with boredom. Conditions improved when Wills was transferred to what was called Camp One. The food got better, letters could be sent home, and there were even volleyball games.

That was, it seems, an early stage of a procedure known as reëducation. Wills was identified as a member of the exploited classes, a promising target for the method. Reflecting on his experiences many years later, he said, “Brainwashing is not done with electrodes stuck to your head.” It was, rather, “a long, horrible process by which a man slowly—step by step, idea by idea—becomes totally convinced, as I was, that the Chinese Communists have unlocked the secret to man’s happiness and that the United States is run by rich bankers, McCarthy types, and ‘imperialist aggressors.’ ”

The theory behind this method, as articulated by Chairman Mao, didn’t sound so bad. People could not be forced to become Marxists, Mao wrote. He recommended, instead, “democratic” methods of “discussion, criticism, persuasion, and education.” An important stage of the process was called “speaking bitterness.” American G.I.s, like the Chinese peasants on whom the method had first been tried, had a great deal of bitterness to speak: of racism and poverty back home, and of discrimination within the armed forces. Wills was made to introspect, to write an autobiography. He and other P.O.W.s were subjected to hours of lectures on Marxist theory.

Faced with the demand to justify “the American system,” Wills—unable to articulate what that even was—found himself moving in what his captors called a Progressive (as opposed to Reactionary) direction. American society was rotting, he came to believe; the Chinese way was the future. He chose not to be repatriated. But, where other prisoners who made the same decision were sent to work on farms and in paper mills, he was sent to the People’s University in Beijing.

The brainwashing process was never complete. Ostentatious acts of “repentance” were repeatedly demanded—Wills had already had to participate in “self-criticism” seminars. He was now taught more about Marxism and the history of China. He even witnessed a public execution. But he ended up staying in China for twelve years.

Wills’s retrospective accounts of his experience, once he was back in the United States and in a position to reflect on what had been done to him, are illuminating. It is plain that his Chinese captors had succeeded, at least for a time, in producing a genuine change of mind. He was, as he himself put it, “totally convinced.”

If we take Wills at his word, we might wonder about Mao’s claim that nobody can be coerced into sincere belief. In professing this, Mao echoes an old idea within modern European thought, one given its most influential expression in John Locke’s 1689 tract, “A Letter Concerning Toleration.” Locke condemned the use of coercion in matters of faith—the sort of thing we now associate with the Spanish Inquisitors—and among his arguments was that it simply couldn’t work. Real belief is a product of the “inward persuasion of the mind,” he wrote. An effective torturer can make his victims move their limbs as he tells them to, or even say the words—professions of faith, confessions of guilt—that he whispers into their ears. But “such is the nature of the understanding, that it cannot be compelled to the belief of anything by outward force.”

Locke’s point is connected to a more general philosophical claim about belief: that no one can just decide to believe something. Try believing, for instance, that the magazine (or computer or tablet or phone) in front of you is a venomous snake, or that your coffee mug is made of molten lava. You can cry out, if you like, but your steady heart rate will give you away.

For all that, you can surely be forced into situations where the desired conviction comes unbidden. Even in the seventeenth century, people saw the limitations of Locke’s view. An Oxford churchman named Jonas Proast agreed that belief could not be coerced directly, but, in his chilling words, the magistrate might lay “such Penalties upon those who refuse to embrace their Doctrine . . . as may make them bethink themselves.”

To force someone to believe something requires the concealment of the role that force has played in the process. The brainwashed can’t conceive of themselves as brainwashed; to do so would indicate that the brain remains unwashed. They can only coherently describe their experience as one of seeing the light, having their consciousness raised, being red-pilled. As Lemov quotes someone telling her about brainwashing: if the method works, it “erases itself.”

So, if your environment was tailored to exclude alternative views, should we say that you were being forced to believe something? Whether we call this coerced belief is a matter of terminological preference. Ways of making people believe things don’t divide neatly into the persuasive and the coercive—the brainwashing model gives the lie to that distinction. As Lemov writes, echoing the psychologist Edgar Schein, it is “neither pure persuasion nor sheer coercion but both: coercive persuasion.”

The phrase “coercive persuasion” effectively conveys the core objection to what it describes. It suppresses the fundamental exercise of human autonomy—it prevents you from making up your own mind. If that’s the case, would the criminal courts find you responsible for what you do when you’ve been brainwashed?

This question was decisively answered during the trial of Patricia (Patty) Hearst, in 1976. Two years earlier, Hearst, a granddaughter of the press magnate William Randolph Hearst, was an undergraduate at Berkeley. Her life changed forever when she caught the eyes of members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, an anti-capitalist guerrilla group. They abducted her and held her in a closet, blindfolded, for nearly two months. She was raped multiple times by the group’s leaders while in captivity, having been told that it would be “uncomradely” to refuse consent.

Shortly afterward, she was offered a nominal choice. Would she join them? Or did she wish to be freed? It was clear to her that the appearance of choice was illusory, that she was choosing between joining the group and being killed. She chose life. Or, as she later put it, “I accommodated my thoughts to coincide with theirs.” As with the Korean War P.O.W.s before her, mere pretense was not, under the circumstances, a real option. “By the time they had finished with me,” she later reflected, “I was, in fact, a soldier in the Symbionese Liberation Army.”

A little more than two months after her abduction, surveillance cameras captured Hearst robbing a bank in San Francisco, gun in hand. When she was eventually arrested, she weighed eighty-seven pounds and was—in the assessment of the psychologist Margaret Singer—“a low-I.Q., low-affect zombie.” The Yale psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton interviewed Hearst for about fifteen hours and then declared her a “classic case” of brainwashing. During her time in custody, she repudiated her allegiance to the S.L.A. When she stood trial for her role in the bank robbery, her attorneys argued that she was a victim of coercion and duress.

It was a risky strategy. “I was brainwashed” was not a legally recognized defense. As Lemov, recounting the episode, points out, one of the psychiatrists who testified as an expert witness for the defense did Hearst no favors by admitting blithely that “brainwashing” was not a term of “any medical significance.” It had become, he said, “a sort of a grab bag to describe any kind of influence exerted by a captor over a captive, but that isn’t very accurate from the scientific or the medical point of view.”

The defense failed. Patty Hearst was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison. After she had completed nearly two, President Jimmy Carter commuted the sentence to “time served.” It was only on Bill Clinton’s last day in office, in 2001, that she received a full pardon.

Why, Lemov asks, have lawyers found brainwashing “impossible to deploy as a legal exculpatory framework”? The concept evidently places defense lawyers in a double bind. If brainwashing doesn’t work, defendants can hardly claim it as a defense. But, if it does work, the defendants are acting on their own beliefs and no longer being coerced. An NPR interviewer forty years after the Hearst trial put the question in a revealing way: “Was she coerced, or did she become a believer?” Lemov rightly asks why it couldn’t be both. Why not say that “Hearst was coerced into becoming a true believer”?

The problem, as Lemov sees it, is that our intuitive model for thinking about brainwashing diagnoses it as a “rational, cognitive malfunction.” Hence the mockery to which the brainwashed are frequently subjected. The brainwashed soldiers of the Korean War were thought of as hapless dupes who “fell for” Communism, Lemov says. She invites us to consider a twenty-first-century parallel: the scorn directed at people who lose their savings to a cryptocurrency cult.

Lemov thinks that this perception shifts once we acknowledge the role of trauma in brainwashing. Maybe so. But how does this claim square with her broader hypothesis that “what we call brainwashing is not rare but common”? If trauma is a necessary condition for brainwashing, as she suggests, it follows that trauma is more widespread than we might assume. Yet she insists that she is not among the credulous sentimentalists who “see trauma everywhere.” How common, then, is brainwashing?

For recent historians of brainwashing, the issue carries high contemporary stakes. Joel Dimsdale, in “Dark Persuasion,” relates the disturbing case of Alexander Urtula, who took his life after receiving a staggering forty-seven thousand text messages from his girlfriend, who kept urging him to do so. Dimsdale asks, “If you can use social media to persuade an individual you know well to do something awful, can you persuade a wider circle of friends and acquaintances?” Given the resources—for instance, “troll farms” of the kind that state actors can muster—it appears that you sometimes can.

The power of such trolls lies in their ability to manipulate the epistemic environment. What was once a lone voice ranting at a street corner becomes a mutually reinforcing chorus. “When observers receive the same message from multiple sources,” Dimsdale writes, “they find the messages more believable, even if they are preposterous.” When President Trump tells us that “a lot of people are saying . . . ,” this claim, at least, is true.

There was outrage when it was revealed that Facebook researchers were tinkering with users’ emotions—making tiny tweaks to their feeds in what Lemov calls “massive-scale emotional engineering.” But she notes that the backlash didn’t stop the researchers from running these experiments; it just made them more reticent about their results. One researcher on the project said that the response amounted to people thinking, “You can’t mess with my emotions. It’s like messing with me. It’s mind control.”

And, in a sense, it is mind control. But that phrase, much like “brainwashing,” runs into a tricky question: Isn’t everything that shapes our thoughts, desires, or feelings a form of mind control? Lurking behind our unease is a fantasy of total, unshackled cognitive freedom. Any deviation from that ideal gets labelled as manipulation. If we cling to that standard, then, sure, we’re all brainwashed. But the standard is an absurdity. It’s obvious that our minds are shaped by the world we live in, including what others say. This isn’t what we have in mind when we talk about mind control.

Our idea, instead, is that to be free is not to be subject to the will of another. Lemov quotes an impassioned remark made by the Princeton sociologist Zeynep Tufekci about how online corporate power enlists “new tools and stealth methods to quietly model our personality, our vulnerabilities, identify our networks, and effectively nudge and shape our ideas, desires and dreams.” That’s the real worry these days—not just influence but control that’s hidden and personal.

Lemov’s emphasis on trauma suggests that the concept of brainwashing may not be all that helpful in understanding whatever it is that social media does to its users. Morris Wills was starved and terrified as a P.O.W. Patty Hearst was locked in a closet and sexually assaulted. Contemporary sociology invites us, perhaps rightly, to extend the traditional concept to include the working-class experience of deindustrialization and the precarity of the white-collar knowledge worker denied a secure job. The question still arises: What has your average TikTok user been subjected to that is remotely comparable to what Wills and Hearst endured?

There’s another irony here. Much of what Wills came to believe when he lived in China—that socialism is superior to capitalism, that the United States is an imperialist power run by a class of kleptocratic oligarchs—is shared by many young people today who were subjected to nothing more traumatic than a typical liberal-arts education. Their professors would, of course, balk at the implication that they’ve brainwashed their students, but that’s exactly what their critics in the conservative media have long been accusing them of.

It’s a familiar pattern in our polarized age. The right accuses the left of using the institutions it dominates—the federal bureaucracy, nonprofits, universities, Hollywood, and “legacy” media—to brainwash the public. The left, in turn, levels the same charge against the right, pointing to talk radio, partisan television networks, and manosphere podcasts. (Each side condemns the other’s social-media activity.) Naturally, no one admits to doing what they denounce in their opponents. But that’s to be expected: persuasion is what we do; brainwashing is what they do.

Does the case of the radical professor fit into this model of malign manipulation? Come to think of it, what exactly should we make of the Communists who brainwashed the American soldiers? Or the members of the Symbionese Liberation Army—mainly white, middle-class, and well educated—who appeared quite sincerely to believe their rhetoric calling for “death to the fascist insect that preys upon the life of the people”? Were they brainwashed into their beliefs, too? Or did they form them in the way that we all do—as the result of some half-conscious process only half mindful of evidence and truth?

We can grant that the term “brainwashing” has some utility as an explanation for what happened to certain individuals who were subjected to extraordinary stress and strenuous efforts at reëducation. But we needn’t reach for it when we seek to describe, and understand, the masses of people who fail to see what we find clear-cut. There are simply too many other ways of making sense of their beliefs.

Heterodox views—particularly antinomian ones—are attractive in part because they are at odds with the obvious. If our beliefs were obvious, how could we use them to distinguish our group from others? How could our beliefs be used to demarcate a social identity? Even in more mainstream precincts, plenty of our avowed beliefs—“our diversity is our strength”—may not be real beliefs at all, if belief is something that holds itself accountable to fact. In ways the philosopher Daniel Williams has explored, they are better understood as shibboleths, tribal anthems, expressions of commitment so deep that we cannot conceive of doubting them. Insofar as these clichés don’t express factual propositions, we shouldn’t apply to them the explanatory frameworks designed to tell us how people come to credit outlandish things.

We may be better served by looking to more conventional human motivations: our desire for approval from those around us, and the way social incentives can reward the outrageous and punish the reasonable. Social media strengthens these tendencies by indulging them and allowing them to operate on an unprecedented scope. Ordinary forces working on a vast scale often produce the effect of an extraordinary force.

Although beliefs can be badges—tribal markers chosen less for their empirical accuracy than for what they signal about us—plenty of people do buy into outlandish factual views. It’s not a cope, or a flex; it’s what they take to be reality. How about them?

There’s a well-meaning, if patronizing, ethical impulse behind our propensity to blame brainwashing for others’ convictions, whether they’re expressions of allegiance, hard factual commitments, or something in between. Labelling people as brainwashed casts them as one of the damned—lost souls whom we, as saviors, must redeem. Yet it might be our own savior complexes that we need to shed.

The philosopher Karl Popper, writing in 1960, suggested that the temptation to attribute misguided beliefs to sinister manipulation came from a mistaken assumption: that “truth is manifest.” If the truth were manifest, it would follow that the failure to grasp it must reflect “the work of powers conspiring to keep us in ignorance, to poison our minds by filling them with falsehood.”

But, even when confronted with a world of people holding views we find baffling, why assume that they’re victims of a grand conspiracy—or victims at all? Perhaps truth isn’t so obvious. Uncovering it demands effort and a bit of luck. Other people will take different things to be true because their paths—owing to differences in diligence or chance—diverged from ours. That conspiracy-minded cousin isn’t necessarily a casualty of mind control; he may simply have wandered down intellectual rabbit holes where evidence matters less than belonging. To depict him as a victim of manipulation grants him an unearned absolution. The most disturbing possibility isn’t that millions have been brainwashed. It’s that they haven’t.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's linguistics adventure: early uses of the word "blog".

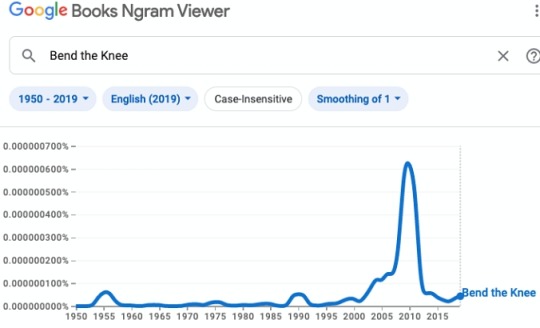

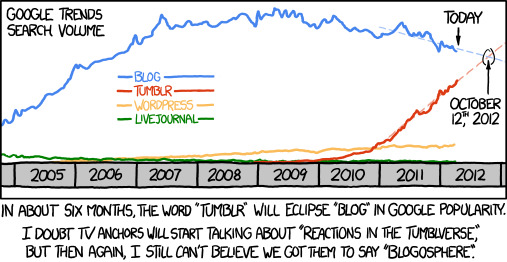

I was back-browsing xkcd, as you do, and 1043 is this:

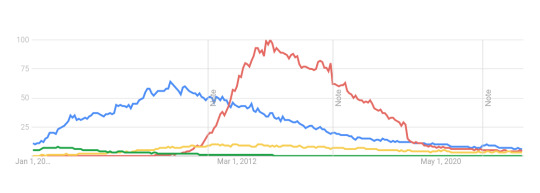

And given the...subsequent developments about Tumblr, I decided to make the equivalent graph today. I eventually found Google Trends, which I don't think is tracking exactly the same thing, but seems pretty compatible:

(And it's surprising to me, how long and how late Tumblr had more google searches than blog. I guess people stopped searching "blog" because everything was a blog?)

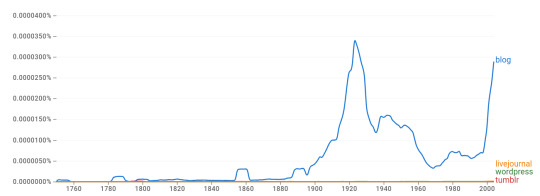

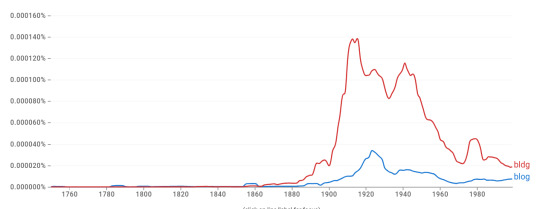

But before that I reached for ngram viewer, and got something interesting.

In this case, the interesting thing isn't the comparison; everything except blog is a visual flatline.

The interesting thing is, this search defaults to start from 1800. Why are there any hits at all? What's going on with that bump in the 1920s? (And a smaller one in the 1860s.)

Let's trim the ending of the series. We get this:

(Note this means that "blog" was more popular in the corpus in 1920 than in 2004, which seems rather improbable.)

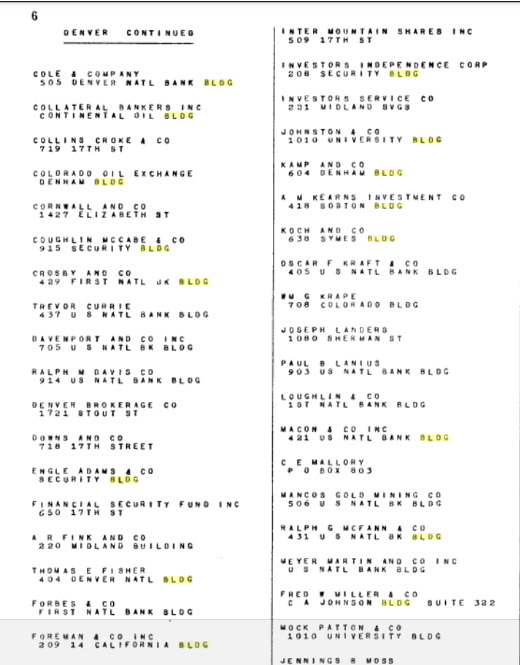

Ngram viewer is drawing from the Google Books corpus, which is, you know, directly searchable. So I looked for hits for "blog" between 1900 and 1940. And the first valid-looking hit is from page 6 of that classic work of literature, Over-the-counter Brokers and Dealers Registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as of January 31, 1936:

Ah. Problem solved?

Almost! But now I wanna know what those other two, earlier bumps, are. In 1822 there's an arithmetic book that has stuff like this:

and it does seem like there are a lot more hits like that; I don't know why they're localized to the 1800s though. I think all the early bumps might be from that, though.

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

BG3 Withers dialogue writing resources

Withers seems to be one of the more difficult characters to write in fanfic because of his archaic way of speaking. But since he's pretty significant in the fanfic I'm working on, I've been going through the datamined game transcripts reviewing all of his lines in attempt to synthesize a Withers Style Guide:

Pronouns: "The Basics of Shakespeare Pronouns: Thee, Thy, Thou, Thine, Ye" explains it better than I can (caveat: Withers doesn't use "ye").

Contractions: He almost never uses them. The only examples I could find were I'd (1), ne'er (3), shan't (1), 'til (5), and upon't (1).

Auxiliary verbs: He seems to use them whenever grammatically possible, sometimes with modern spellings (am, are, be, is, must, shall, will) and sometimes with archaic spellings (canst, didst, dost, doth, hast, hast, hath, mayest, needeth, needst, shouldst, wilt, wouldst).

Verb conjugations: The game writers weren't terribly consistent with these, but he tends to conjugate second person singular verbs with -est/-st endings and the third person verbs with -eth/-th endings. He seems to use mostly modern conjugations when speaking in the first person.

Vocabulary: He peppers his speech with dated terminology like bosom companion, cleave, forsooth, pittance, proffer, seneschal, yoke, etc. (Google Books Ngram Viewer is a good tool for checking how dated a term is.)

Verbosity: Withers is generally quite terse. If the rule of thumb for writing Gale is use twice as many words as necessary, then the rule of thumb for writing Withers is to use as few words as possible (with the aforementioned exceptions of no contractions and lots of auxiliary verbs). Or simply have him refuse to elaborate as that is very in-character for him.

Complete corpus: I went through the datamined files and copypasted all of Withers' lines into a Google Doc because I personally find it useful to immerse myself in a single character's voice before attempting to write them. Please note that it includes cut content as well as MAJOR SPOILERS FOR EVERYTHING because he narrates the epilogue. I included the file names as headers in case you want to refer back to the datamined dialogue for the context in which he says a particular line.

#BG3#Baldur's Gate 3#bg3 fanfic writing resources#Withers#Withers BG3#BG3 Withers#Jergal#Jergal BG3#BG3 Jergal#the autism won today

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

The "Middle West"

I was recently watching Trump speak (not something I typically do 🤢), and the most interesting thing he said had nothing to do with anything he was actually talking about: It was that he used the term Middle West to refer to that generally north-central part of the United States, centered on the Mississippi River, that is neither the South nor the Northeast (nor the Mid-Atlantic, but that's really just a subcategory of the Northeast that Northeasterns use to not get lumped in with each other).

We all know it today as the Midwest. But in times past it was much more commonly known as the Middle West.

(Tangent: It is also one of many geographical region-name reminders of our national East Coast beginnings, as America has like six different kinds of "West": the Midwest, the Southwest, the (Pacific) Northwest, the Mountain West / Interior West, the West Coast / Pacific West—and that's not counting the deprecated terms (such as "Far West," i.e. distinguished from the Midwest) or the old Northwest (which would've referred to places like Ohio and (what we know as) West Virginia)!)

Over the course of the 20th century, "Midwest" became an increasingly common form of the term, eventually overtaking "Middle West" in popularity and, by our lifetimes, completely replacing it. The only people who still use "Middle West" today are very old. I'm only aware of the term's existence because I'm a fan of midcentury media and if you go watch (for example) old Dragnet episodes from the 1950s you'll hear the term used.

I was looking at the Google Ngram Viewer to get a sense of the relative usage frequencies of these terms, and I noticed something interesting: Not only has "Middle West" been driven almost extinct from active usage, but "Midwest" itself has also declined precipitously in the 21st century. People today are not calling the Midwest the "Midwest," at least not with the frequency and relevancy they once did. I was curious if this was another permutation of the usage, so I also looked up "Midwestern" (which I included in the link above), thinking that maybe people nowadays are calling it the clunkier "the Midwestern states" / "the Midwestern US," but the adjectival has declined in step with "Midwest." It really does seem to be that people are just using this geographical category less often.

Perhaps unsurprisingly: the sociopolitical cohesiveness of the Midwest has significantly diminished over time. I think most Midwesterners would still recognize and affiliate with the term if you applied it of them to their faces, but increasingly I think many of them do not think of it in their daily lives as a personal or cultural identifier. Which has many fascinating implications that I'm not going to get into.

(Another Tangent: I feel like I've talked about specifically this "Middle West / Midwest" thing on Tumblr before, but I feel that way about half of everything because after all I've been writing down my thoughts for over 20 years and I've been having thoughts for considerably longer than that, and it's often not clear to me what I've talked about publicly and where.)

Anyway, this entire post is really just me scratching the itch of verbal brain noise about the orange guy using a term in a public address that I never hear people use in the present day. A little piece of lost language, hearkening back to a completely different era and world.

#To be fair America also has like four “Easts”#The Northeast and the Southeast and the Eastern Seaboard and of course the East Coast#And several “Norths” albeit rarely in name which I guess is actually kinda standout#Including the Upper Midwest and New England and the aforementioned Northeast and the Industrial / Rust Belt#BUT ONLY ONE “THE SOUTH”#Well not counting Southwest#Which is more commonly associated with barbecue and airplanes and sagHWWaro cacti#And the Southeast#Which is really just a polite term for “The States Where People Go to Lose Their Damn Minds"#“And Where Horrifying New Superbugs Evolve Every 10 Minutes”#Hot Dish

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

get a load of this butthurt yankee who believes language is static. according to the google ngram viewer "crack whore" wasn't a real term until the 1990s, and "USAmerican" appears in literature about a decade earlier than that colorful insult

Also you missed a "will" between "never" and "be". If you're gonna be an ass about the correct use of language at least proofread your tantrums

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Steve Stewart-Williams

Published: Nov 25, 2025

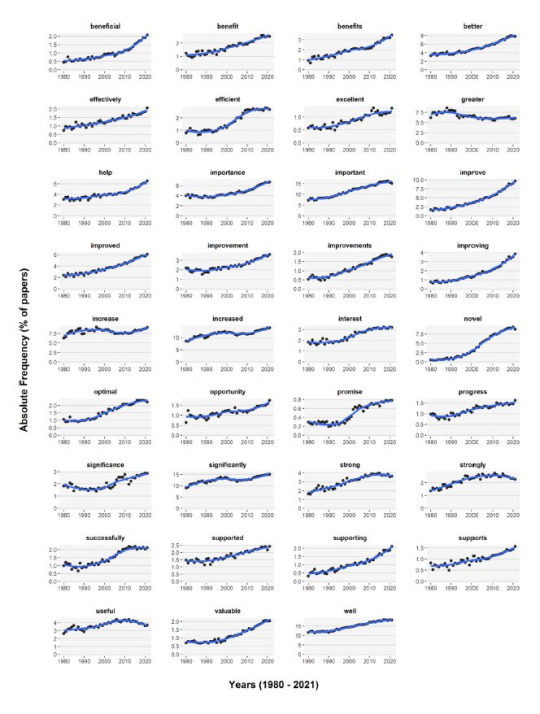

An analysis of 2,300,000 abstracts from scientific papers shows that scientists are increasingly hyping their findings. The graph below shows the frequency of 35 words indicative of hype from 1980 to 2020.

Curiously, the trend is more pronounced in psychology than in biology or physics.

The graph is from a new paper in Scientometrics by Moritz Edlinger, Finn Buchrieser, and Guilherme Wood, titled “Presence and Consequences of Positive Words in Scientific Abstracts.” Here’s the abstract (an abstract about abstracts):

Abstracts are the showcase of scientific studies, crafted to make an impression on the reader within a limited space and to determine the amount of attention each study receives. Systemic conditions in the sciences may change the expressive norm and incentive scientists to hype abstracts to promote their work and career. Previous studies found that terms such as “unprecedented”, “novel” and “unique” have been used increasingly in recent history, to describe one’s own research findings. The present study investigates the use of valence-loaded scientific jargon in the abstracts of scientific articles. Sentiment analysis with dictionaries specifically attuned to detect valence-loaded scientific jargon was employed to analyze more than 2,300,000 MEDLINE abstracts from the fields of psychology, biology, and physics. Results show that over the last four decades, abstracts have contained an increasing amount of valence-loaded scientific jargon, as previously observed in earlier studies. Moreover, our results reveal that the positive emotional content of abstracts is increasing in a way that cannot be accounted for by the increase in text length, which has also been observed in the same time period. There were small differences between scientific disciplines. A detailed analysis of the distribution of valence-loaded scientific jargon within abstracts reveals a strong concentration towards the end of the text. We discuss these results in light of psychological evidence relating positive emotions with the propensity to overestimate the value of information to inform judgment and the increase in the competition for attention due to a pressure to publish.

--

See also:

Abstract

Objective To investigate whether language used in science abstracts can skew towards the use of strikingly positive and negative words over time.

Design Retrospective analysis of all scientific abstracts in PubMed between 1974 and 2014.

Methods The yearly frequencies of positive, negative, and neutral words (25 preselected words in each category), plus 100 randomly selected words were normalised for the total number of abstracts. Subanalyses included pattern quantification of individual words, specificity for selected high impact journals, and comparison between author affiliations within or outside countries with English as the official majority language. Frequency patterns were compared with 4% of all books ever printed and digitised by use of Google Books Ngram Viewer.

Main outcome measures Frequencies of positive and negative words in abstracts compared with frequencies of words with a neutral and random connotation, expressed as relative change since 1980.

Results The absolute frequency of positive words increased from 2.0% (1974-80) to 17.5% (2014), a relative increase of 880% over four decades. All 25 individual positive words contributed to the increase, particularly the words “robust,” “novel,” “innovative,” and “unprecedented,” which increased in relative frequency up to 15 000%. Comparable but less pronounced results were obtained when restricting the analysis to selected journals with high impact factors. Authors affiliated to an institute in a non-English speaking country used significantly more positive words. Negative word frequencies increased from 1.3% (1974-80) to 3.2% (2014), a relative increase of 257%. Over the same time period, no apparent increase was found in neutral or random word use, or in the frequency of positive word use in published books.

Conclusions Our lexicographic analysis indicates that scientific abstracts are currently written with more positive and negative words, and provides an insight into the evolution of scientific writing. Apparently scientists look on the bright side of research results. But whether this perception fits reality should be questioned.

#Steve Stewart Williams#hype#scientific paper#scientific journal#science#scientific study#science hype#religion is a mental illness

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

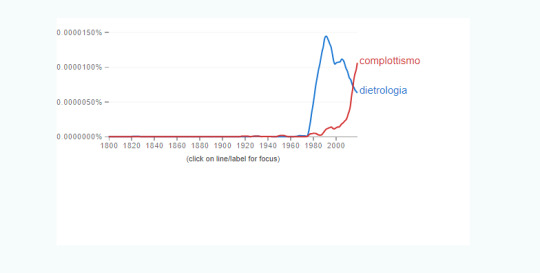

IL SORPASSO.

Frequenza dell'uso dei termini "complottismo" e "dietrologia" - il nome che gli si dava nel secolo scorso - secondo Google Ngram Viewer, il servizio di Google che misura le occorrenze delle parole nei libri pubblicati in una data lingua sui libri digitalizzati fino al 2019.

Via https://www.ilpost.it/2024/02/08/sgobba-quando-il-complottismo-si-chiamava-dietrologia/

Della parola “complottismo”, prima degli anni Ottanta non ci sono occorrenze. “Complotto” è un francesismo che all’inizio era semplicemente sinonimo di “folla”, poi venne usato al posto di “congiura” o “cospirazione”, si diffuse negli anni Venti attraverso l’espressione “complotto giudaico”.

«(Dietrologia é) parola sconosciuta in altre lingue. (E') la convinzione che quel che si vede, si legge e si sente dire non è la verità, ma che essa sta dietro, sotto, sopra, accanto, al di là – comunque non esposta agli occhi dell’uomo della strada», scriveva nel 2001 lo storico della letteratura italiana Joseph Farrell. A quel tempo "dietrologia" era termine dismissivo usato da decenni dai conservatori - Indro Montanelli il principale - per descrivere la mentalità "vi stanno fregando di nascosto, non ci cascate" tipica della sinistra ruspante d'allora.

Complottismo supera e rimpiazza dietrologia per via internazionale. Siamo nel 2015, l’anno delle campagne elettorali Brexit e dell’elezione di Donald Trump. Dopo la "first reaction, choc" (cit. Renzi) del mainstream media a quei due accadimenti nefasti (per loro), parte la delegittimazione.

Ironia del destino cinico e baro: prima la "dietrologia" distingueva la sinistra, ora essa subisce il complottismo, senza rendersi conto che sono loro, elite e affluent, ad essersi spostati (dal popolazzo alla turris eburnea). Alcuni reagiscono: pur essendo ora elite non è il caso di togliersi un'arma così potente. I chierici dell'ortodossia del Wu Ming 1 propongono di distinguere tra ipotesi di complotto (specifiche, confutabili, limitate nel tempo) e fantasie di complotto (universali, inconfutabili, eterne). Molto logico sul piano teorico, solo che sul piano pratico si esercita mediante presidi "fact checking": carubbaneri al posto di blocco lungo la circolazione delle idee, patente e libretto.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas words: Christmas card

At Christmas time, it always felt like every surface of my grandparents house was covered in Christmas cards. Cards from family and friends and from all corners of the world. My grandfather enjoyed writing and sending many cards, as well as receiving many in return.

I really love the tradition of Christmas cards, although I only have the enthusiasm to send them to close family and friends. It's one of the few times of the year I still take the time to make use of the postal service for social correspondence.

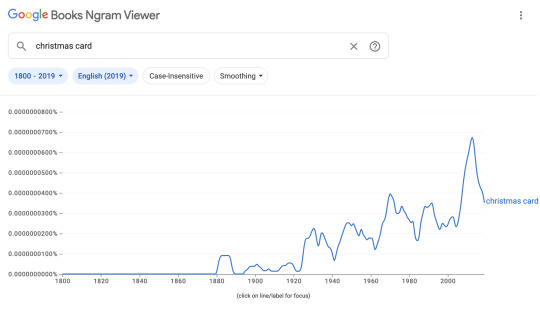

Like many things I think of as canonically Christmas, seasonal greetings cards are only a tradition from the last couple of centuries. The earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary for Christmas cards is from 1860. You can also see from Google ngrams viewer (screenshot below) that the phrase 'Christmas card' took a while to pick up in written English.

Christmas cards are such a wonderful reflection of the aesthetic, concerns and sometimes the sense of humour of a particular era. There's a great range of Christmas cards on the relevant Wikipedia page, including these charming marching frogs.

Christmas card by Louis Prang, showing a group of anthropomorphized frogs parading with banner and band. Via Wikipedia.

At Superlinguo, I celebrate the silly season with Christmasy words. The full list is here. If you’ve got a Christmas word you’re curious about, let me know!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

This tool(Ngram Viewer) is hard to use when looking up specific books, but when looking up words relating to concepts that we have covered so far this year you can see some diversity in the graph. You can also go to the bottom of the page and see how the words manifested in literary works over a certain time period. You can then compare the literary works over a different time period and how they have changed as well as compare the different input words over the same time period. This allows you to look at the progression of literary works in relation to the words that you input and can help the user to get a different of better perspective on the progression of literature over time.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Google Ngram viewer

This tool allows you to search words or phrases that appear in books over a time period in years that you choose. It then graphs them by frequency and charts and compares different authors. You can also add tags to narrow or expand your search. In terms of using this to aid literary criticism it should allow the user to search words or phrases that can track trends in literature or the rise/fall of certain topics.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi guru!! i don’t have a chance to read thru everything going on but if im seeing correctly it sucks yo see you’re getting hate, i know not everyone is a big fan of the medieval vibes (honestly i didnt even think i was going to be) and everyone has their opinions but spreading hate vs sharing your opinion respectfully is a big difference and i dont think anyone should go into someone else’s platform and just spread hate abt their work 😭😭

but anyway i actually have a few questions for you!! first one is abt king harry and i was wondering this last night after i saw one of your anon asks and its of you like looked up any vocabulary on what english people said in the 1800s or like watched any shows and just got it from that? andddd second question is just me wondering since we got part 2 of pornstar harry this week is there gonna be a part 2 to alpha harry?

that’s it tho! hope you’re having a great day and if you need me to beat any anons up i will 🙂↕️ (i haven’t been to the gym in a year and i can’t even stomp on a spider)

HII!

Oh the negativity is just part of this I guess. I try not to put any stock in what some people say so it's fine! I'm really not upset over it. I just move on. There will always be people who are miserable and want to make others around them miserable. I choose to enjoy life and appreciate things around me instead.

So for your questions about kingrry - YES. I've looked up vocabulary from multiple sources and have read a bunch of old articles and perused old Victorian books/stories to get a feel for things.

I also use THIS and the Google Books Ngram Viewer to gauge what verbiage was used when to assist. Plus a lot of googling random things and photos of Victorian era foods, castle interiors, clothing, etc. It has been a lot of work to be honest.

To your other question... I do plan to give y'all another part to alpharry (it's been requested)! Maybe next week even (or week after).

I'm having a good day, thank you! About to take an exam and then make some dinner and try to get to editing HDYP 7 so I can post for y'all tonight!

And thank you 🤣 Appreciate it haha 🤭

xoxo

0 notes