#or further isolated into the separate horror of a lack of existence

Text

you know there’s a specific kind of horror to sidestep not being Broken, but being Changed in some way. there’s obvious reasons to break, but to change is something else.

change raises questions of why? why were they changed? what is the intended outcome of the change? what specifically was done to incite the change? there’s horror in being changed to someone’s idea of how someone should act/what their personality should be; who they are as defined by someone else. existence dictated by someone else, and furthermore to wonder and live in a way as such to wonder if what came before was “who they are” or what here now is truly the reality.

#i know the game deals w this a lot already but it really Scratched My Brain#bc sidestep is already a construct—the person behind the persona of sidestep and sidestep as the title#both are fabrications. both are changed#one by sidestep’s own hands and the other by outside forces#the horror of being changed once by heartbreak and the horror that lies in the further changes by the farm#how does sidestep define existence on human terms when such things do not belong to them#have they been changed to more resemble the horrors of living as a human#or further isolated into the separate horror of a lack of existence#im thinking too about humans pack bonding with nearly anything#and deep deep down regenes started from somewhere. there was a basis of them#created by human hands. defined by humanity bc that is the only perception humans have of defining the world#in a way then deep down sidestep holds some small spark of humanity#I could say more but y’all gotta wait a month and then I’ll have brainrot again#fallen hero

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 3: Mutual Aid Among Savages

Supposed war of each against all. — Tribal origin of human society. — Late appearance of the separate family. — Bushmen and Hottentots. — Australians, Papuas. — Eskimos, Aleoutes. — Features of savage life difficult to understand for the European. — The Dayak’s conception of justice. — Common law.

The immense part played by mutual aid and mutual support in the evolution of the animal world has been briefly analyzed in the preceding chapters. We have now to cast a glance upon the part played by the same agencies in the evolution of mankind. We saw how few are the animal species which live an isolated life, and how numberless are those which live in societies, either for mutual defence, or for hunting and storing up food, or for rearing their offspring, or simply for enjoying life in common. We also saw that, though a good deal of warfare goes on between different classes of animals, or different species, or even different tribes of the same species, peace and mutual support are the rule within the tribe or the species; and that those species which best know how to combine, and to avoid competition, have the best chances of survival and of a further progressive development. They prosper, while the unsociable species decay.

It is evident that it would be quite contrary to all that we know of nature if men were an exception to so general a rule: if a creature so defenceless as man was at his beginnings should have found his protection and his way to progress, not in mutual support, like other animals, but in a reckless competition for personal advantages, with no regard to the interests of the species. To a mind accustomed to the idea of unity in nature, such a proposition appears utterly indefensible. And yet, improbable and unphilosophical as it is, it has never found a lack of supporters. There always were writers who took a pessimistic view of mankind. They knew it, more or less superficially, through their own limited experience; they knew of history what the annalists, always watchful of wars, cruelty, and oppression, told of it, and little more besides; and they concluded that mankind is nothing but a loose aggregation of beings, always ready to fight with each other, and only prevented from so doing by the intervention of some authority.

Hobbes took that position; and while some of his eighteenth-century followers endeavoured to prove that at no epoch of its existence — not even in its most primitive condition — mankind lived in a state of perpetual warfare; that men have been sociable even in “the state of nature,” and that want of knowledge, rather than the natural bad inclinations of man, brought humanity to all the horrors of its early historical life, — his idea was, on the contrary, that the so-called “state of nature” was nothing but a permanent fight between individuals, accidentally huddled together by the mere caprice of their bestial existence. True, that science has made some progress since Hobbes’s time, and that we have safer ground to stand upon than the speculations of Hobbes or Rousseau. But the Hobbesian philosophy has plenty of admirers still; and we have had of late quite a school of writers who, taking possession of Darwin’s terminology rather than of his leading ideas, made of it an argument in favour of Hobbes’s views upon primitive man, and even succeeded in giving them a scientific appearance. Huxley, as is known, took the lead of that school, and in a paper written in 1888 he represented primitive men as a sort of tigers or lions, deprived of all ethical conceptions, fighting out the struggle for existence to its bitter end, and living a life of “continual free fight”; to quote his own words — “beyond the limited and, temporary relations of the family, the Hobbesian war of each against all was the normal state of existence.”[68]

It has been remarked more than once that the chief error of Hobbes, and the eighteenth-century philosophers as well, was to imagine that mankind began its life in the shape of small straggling families, something like the “limited and temporary” families of the bigger carnivores, while in reality it is now positively known that such was not the case. Of course, we have no direct evidence as to the modes of life of the first man-like beings. We are not yet settled even as to the time of their first appearance, geologists being inclined at present to see their traces in the pliocene, or even the miocene, deposits of the Tertiary period. But we have the indirect method which permits us to throw some light even upon that remote antiquity. A most careful investigation into the social institutions of the lowest races has been carried on during the last forty years, and it has revealed among the present institutions of primitive folk sometraces of still older institutions which have long disappeared, but nevertheless left unmistakable traces of their previous existence. A whole science devoted to the embryology of human institutions has thus developed in the hands of Bachofen, MacLennan, Morgan, Edwin Tylor, Maine, Post, Kovalevsky, Lubbock, and many others. And that science has established beyond any doubt that mankind did not begin its life in the shape of small isolated families.

Far from being a primitive form of organization, the family is a very late product of human evolution. As far as we can go back in the palæo-ethnology of mankind, we find men living in societies — in tribes similar to those of the highest mammals; and an extremely slow and long evolution was required to bring these societies to the gentile, or clan organization, which, in its turn, had to undergo another, also very long evolution, before the first germs of family, polygamous or monogamous, could appear. Societies, bands, or tribes — not families — were thus the primitive form of organization of mankind and its earliest ancestors. That is what ethnology has come to after its painstaking researches. And in so doing it simply came to what might have been foreseen by the zoologist. None of the higher mammals, save a few carnivores and a few undoubtedly-decaying species of apes (orang-outans and gorillas), live in small families, isolatedly straggling in the woods. All others live in societies. And Darwin so well understood that isolately-living apes never could have developed into man-like beings, that he was inclined to consider man as descended from some comparatively weak but social species, like the chimpanzee, rather than from some stronger but unsociable species, like the gorilla.[69] Zoology and palaeo-ethnology are thus agreed in considering that the band, not the family, was the earliest form of social life. The first human societies simply were a further development of those societies which constitute the very essence of life of the higher animals.[70]

If we now go over to positive evidence, we see that the earliest traces of man, dating from the glacial or the early post-glacial period, afford unmistakable proofs of man having lived even then in societies. Isolated finds of stone implements, even from the old stone age, are very rare; on the contrary, wherever one flint implement is discovered others are sure to be found, in most cases in very large quantities. At a time when men were dwelling in caves, or under occasionally protruding rocks, in company with mammals now extinct, and hardly succeeded in making the roughest sorts of flint hatchets, they already knew the advantages of life in societies. In the valleys of the tributaries of the Dordogne, the surface of the rocks is in some places entirely covered with caves which were inhabited by palæolithic men.[71] Sometimes the cave-dwellings are superposed in storeys, and they certainly recall much more the nesting colonies of swallows than the dens of carnivores. As to the flint implements discovered in those caves, to use Lubbock’s words, “one may say without exaggeration that they are numberless.” The same is true of other palæolithic stations. It also appears from Lartet’s investigations that the inhabitants of the Aurignac region in the south of France partook of tribal meals at the burial of their dead. So that men lived in societies, and had germs of a tribal worship, even at that extremely remote epoch.

The same is still better proved as regards the later part of the stone age. Traces of neolithic man have been found in numberless quantities, so that we can reconstitute his manner of life to a great extent. When the ice-cap (which must have spread from the Polar regions as far south as middle France, middle Germany, and middle Russia, and covered Canada as well as a good deal of what is now the United States) began to melt away, the surfaces freed from ice were covered, first, with swamps and marshes, and later on with numberless lakes.[72] Lakes filled all depressions of the valleys before their waters dug out those permanent channels which, during a subsequent epoch, became our rivers. And wherever we explore, in Europe, Asia, or America, the shores of the literally numberless lakes of that period, whose proper name would be the Lacustrine period, we find traces of neolithic man. They are so numerous that we can only wonder at the relative density of population at that time. The “stations” of neolithic man closely follow each other on the terraces which now mark the shores of the old lakes. And at each of those stations stone implements appear in such numbers, that no doubt is possible as to the length of time during which they were inhabited by rather numerous tribes. Whole workshops of flint implements, testifying of the numbers of workers who used to come together, have been discovered by the archæologists.

Traces of a more advanced period, already characterized by the use of some pottery, are found in the shell-heaps of Denmark. They appear, as is well known, in the shape of heaps from five to ten feet thick, from 100 to 200 feet wide, and 1,000 feet or more in length, and they are so common along some parts of the sea-coast that for a long time they were considered as natural growths. And yet they “contain nothing but what has been in some way or other subservient to the use of man,” and they are so densely stuffed with products of human industry that, during a two days’ stay at Milgaard, Lubbock dug out no less than 191 pieces of stone-implements and four fragments of pottery.[73] The very size and extension of the shell heaps prove that for generations and generations the coasts of Denmark were inhabited by hundreds of small tribes which certainly lived as peacefully together as the Fuegian tribes, which also accumulate like shellheaps, are living in our own times.

As to the lake-dwellings of Switzerland, which represent a still further advance in civilization, they yield still better evidence of life and work in societies. It is known that even during the stone age the shores of the Swiss lakes were dotted with a succession of villages, each of which consisted of several huts, and was built upon a platform supported by numberless pillars in the lake. No less than twenty-four, mostly stone age villages, were discovered along the shores of Lake Leman, thirty-two in the Lake of Constance, forty-six in the Lake of Neuchâtel, and so on; and each of them testifies to the immense amount of labour which was spent in common by the tribe, not by the family. It has even been asserted that the life of the lake-dwellers must have been remarkably free of warfare. And so it probably was, especially if we refer to the life of those primitive folk who live until the present time in similar villages built upon pillars on the sea coasts.

It is thus seen, even from the above rapid hints, that our knowledge of primitive man is not so scanty after all, and that, so far as it goes, it is rather opposed than favourable to the Hobbesian speculations. Moreover, it may be supplemented, to a great extent, by the direct observation of such primitive tribes as now stand on the same level of civilization as the inhabitants of Europe stood in prehistoric times.

That these primitive tribes which we find now are not degenerated specimens of mankind who formerly knew a higher civilization, as it has occasionally been maintained, has sufficiently been proved by Edwin Tylor and Lubbock. However, to the arguments already opposed to the degeneration theory, the following may be added. Save a few tribes clustering in the less-accessible highlands, the “savages” represent a girdle which encircles the more or less civilized nations, and they occupy the extremities of our continents, most of which have retained still, or recently were bearing, an early post-glacial character. Such are the Eskimos and their congeners in Greenland, Arctic America, and Northern Siberia; and, in the Southern hemisphere, the Australians, the Papuas, the Fuegians, and, partly, the Bushmen; while within the civilized area, like primitive folk are only found in the Himalayas, the highlands of Australasia, and the plateaus of Brazil. Now it must be borne in mind that the glacial age did not come to an end at once over the whole surface of the earth. It still continues in Greenland. Therefore, at a time when the littoral regions of the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, or the Gulf of Mexico already enjoyed a warmer climate, and became the seats of higher civilizations, immense territories in middle Europe, Siberia, and Northern America, as well as in Patagonia, Southern Africa, and Southern Australasia, remained in early postglacial conditions which rendered them inaccessible to the civilized nations of the torrid and sub-torrid zones. They were at that time what the terrible urmans of North-West Siberia are now, and their population, inaccessible to and untouched by civilization, retained the characters of early post-glacial man. Later on, when desiccation rendered these territories more suitable for agriculture, they were peopled with more civilized immigrants; and while part of their previous inhabitants were assimilated by the new settlers, another part migrated further, and settled where we find them. The territories they inhabit now are still, or recently were, sub-glacial, as to their physical features; their arts and implements are those of the neolithic age; and, notwithstanding their racial differences, and the distances which separate them, their modes of life and social institutions bear a striking likeness. So we cannot but consider them as fragments of the early post-glacial population of the now civilized area.

The first thing which strikes us as soon as we begin studying primitive folk is the complexity of the organization of marriage relations under which they are living. With most of them the family, in the sense we attribute to it, is hardly found in its germs. But they are by no means loose aggregations of men and women coming in a disorderly manner together in conformity with their momentary caprices. All of them are under a certain organization, which has been described by Morgan in its general aspects as the “gentile,” or clan organization.[74]

To tell the matter as briefly as possible, there is little doubt that mankind has passed at its beginnings through a stage which may be described as that of “communal marriage”; that is, the whole tribe had husbands and wives in common with but little regard to consanguinity. But it is also certain that some restrictions to that free intercourse were imposed at a very early period. Inter-marriage was soon prohibited between the sons of one mother and her sisters, granddaughters, and aunts. Later on it was prohibited between the sons and daughters of the same mother, and further limitations did not fail to follow. The idea of a gens, or clan, which embodied all presumed descendants from one stock (or rather all those who gathered in one group) was evolved, and marriage within the clan was entirely prohibited. It still remained “communal,” but the wife or the husband had to be taken from another clan. And when a gens became too numerous, and subdivided into several gentes, each of them was divided into classes (usually four), and marriage was permitted only between certain well-defined classes. That is the stage which we find now among the Kamilaroi-speaking Australians. As to the family, its first germs appeared amidst the clan organization. A woman who was captured in war from some other clan, and who formerly would have belonged to the whole gens, could be kept at a later period by the capturer, under certain obligations towards the tribe. She may be taken by him to a separate hut, after she had paid a certain tribute to the clan, and thus constitute within the gens a separate family, the appearance of which evidently was opening a quite new phase of civilization.[75]

Now, if we take into consideration that this complicated organization developed among men who stood at the lowest known degree of development, and that it maintained itself in societies knowing no kind of authority besides the authority of public opinion, we at once see how deeply inrooted social instincts must have been in human nature, even at its lowest stages. A savage who is capable of living under such an organization, and of freely submitting to rules which continually clash with his personal desires, certainly is not a beast devoid of ethical principles and knowing no rein to its passions. But the fact becomes still more striking if we consider the immense antiquity of the clan organization. It is now known that the primitive Semites, the Greeks of Homer, the prehistoric Romans, the Germans of Tacitus, the early Celts and the early Slavonians, all have had their own period of clan organization, closely analogous to that of the Australians, the Red Indians, the Eskimos, and other inhabitants of the “savage girdle.”[76] So we must admit that either the evolution of marriage laws went on on the same lines among all human races, or the rudiments of the clan rules were developed among some common ancestors of the Semites, the Aryans, the Polynesians, etc., before their differentiation into separate races took place, and that these rules were maintained, until now, among races long ago separated from the common stock. Both alternatives imply, however, an equally striking tenacity of the institution — such a tenacity that no assaults of the individual could break it down through the scores of thousands of years that it was in existence. The very persistence of the clan organization shows how utterly false it is to represent primitive mankind as a disorderly agglomeration of individuals, who only obey their individual passions, and take advantage of their personal force and cunningness against all other representatives of the species. Unbridled individualism is a modern growth, but it is not characteristic of primitive mankind.[77]

Going now over to the existing savages, we may begin with the Bushmen, who stand at a very low level of development — so low indeed that they have no dwellings and sleep in holes dug in the soil, occasionally protected by some screens. It is known that when Europeans settled in their territory and destroyed deer, the Bushmen began stealing the settlers’ cattle, whereupon a war of extermination, too horrible to be related here, was waged against them. Five hundred Bushmen were slaughtered in 1774, three thousand in 1808 and 1809 by the Farmers’ Alliance, and so on. They were poisoned like rats, killed by hunters lying in ambush before the carcass of some animal, killed wherever met with.[78] So that our knowledge of the Bushmen, being chiefly borrowed from those same people who exterminated them, is necessarily limited. But still we know that when the Europeans came, the Bushmen lived in small tribes (or clans), sometimes federated together; that they used to hunt in common, and divided the spoil without quarrelling; that they never abandoned their wounded, and displayed strong affection to their comrades. Lichtenstein has a most touching story about a Bushman, nearly drowned in a river, who was rescued by his companions. They took off their furs to cover him, and shivered themselves; they dried him, rubbed him before the fire, and smeared his body with warm grease till they brought him back to life. And when the Bushmen found, in Johan van der Walt, a man who treated them well, they expressed their thankfulness by a most touching attachment to that man.[79] Burchell and Moffat both represent them as goodhearted, disinterested, true to their promises, and grateful,[80] all qualities which could develop only by being practised within the tribe. As to their love to children, it is sufficient to say that when a European wished to secure a Bushman woman as a slave, he stole her child: the mother was sure to come into slavery to share the fate of her child.[81]

The same social manners characterize the Hottentots, who are but a little more developed than the Bushmen. Lubbock describes them as “the filthiest animals,” and filthy they really are. A fur suspended to the neck and worn till it falls to pieces is all their dress; their huts are a few sticks assembled together and covered with mats, with no kind of furniture within. And though they kept oxen and sheep, and seem to have known the use of iron before they made acquaintance with the Europeans, they still occupy one of the lowest degrees of the human scale. And yet those who knew them highly praised their sociability and readiness to aid each other. If anything is given to a Hottentot, he at once divides it among all present — a habit which, as is known, so much struck Darwin among the Fuegians. He cannot eat alone, and, however hungry, he calls those who pass by to share his food. And when Kolben expressed his astonishment thereat, he received the answer. “That is Hottentot manner.” But this is not Hottentot manner only: it is an all but universal habit among the “savages.” Kolben, who knew the Hottentots well and did not pass by their defects in silence, could not praise their tribal morality highly enough.

“Their word is sacred,” he wrote. They know “nothing of the corruptness and faithless arts of Europe.” “They live in great tranquillity and are seldom at war with their neighbours.” They are “all kindness and goodwill to one another.... One of the greatest pleasures of the Hottentots certainly lies in their gifts and good offices to one another.” “The integrity of the Hottentots, their strictness and celerity in the exercise of justice, and their chastity, are things in which they excel all or most nations in the world.”[82]

Tachart, Barrow, and Moodie[83] fully confirm Kolben’s testimony. Let me only remark that when Kolben wrote that “they are certainly the most friendly, the most liberal and the most benevolent people to one another that ever appeared on the earth” (i. 332), he wrote a sentence which has continually appeared since in the description of savages. When first meeting with primitive races, the Europeans usually make a caricature of their life; but when an intelligent man has stayed among them for a longer time, he generally describes them as the “kindest” or “the gentlest” race on the earth. These very same words have been applied to the Ostyaks, the Samoyedes, the Eskimos, the Dayaks, the Aleoutes, the Papuas, and so on, by the highest authorities. I also remember having read them applied to the Tunguses, the Tchuktchis, the Sioux, and several others. The very frequency of that high commendation already speaks volumes in itself.

The natives of Australia do not stand on a higher level of development than their South African brothers. Their huts are of the same character, very often simple screens are the only protection against cold winds. In their food they are most indifferent: they devour horribly putrefied corpses, and cannibalism is resorted to in times of scarcity. When first discovered by Europeans, they had no implements but in stone or bone, and these were of the roughest description. Some tribes had even no canoes, and did not know barter-trade. And yet, when their manners and customs were carefully studied, they proved to be living under that elaborate clan organization which I have mentioned on a preceding page.[84]

The territory they inhabit is usually allotted between the different gentes or clans; but the hunting and fishing territories of each clan are kept in common, and the produce of fishing and hunting belongs to the whole clan; so also the fishing and hunting implements.[85] The meals are taken in common. Like many other savages, they respect certain regulations as to the seasons when certain gums and grasses may be collected.[86] As to their morality altogether, we cannot do better than transcribe the following answers given to the questions of the Paris Anthropological Society by Lumholtz, a missionary who sojourned in North Queensland:[87]

“The feeling of friendship is known among them; it is strong. Weak people are usually supported; sick people are very well attended to; they never are abandoned or killed. These tribes are cannibals, but they very seldom eat members of their own tribe (when immolated on religious principles, I suppose); they eat strangers only. The parents love their children, play with them, and pet them. Infanticide meets with common approval. Old people are very well treated, never put to death. No religion, no idols, only a fear of death. Polygamous marriage, quarrels arising within the tribe are settled by means of duels fought with wooden swords and shields. No slaves; no culture of any kind; no pottery; no dress, save an apron sometimes worn by women. The clan consists of two hundred individuals, divided into four classes of men and four of women; marriage being only permitted within the usual classes, and never within the gens.”

For the Papuas, closely akin to the above, we have the testimony of G.L. Bink, who stayed in New Guinea, chiefly in Geelwink Bay, from 1871 to 1883. Here is the essence of his answers to the same questioner:[88] —

“They are sociable and cheerful; they laugh very much. Rather timid than courageous. Friendship is relatively strong among persons belonging to different tribes, and still stronger within the tribe. A friend will often pay the debt of his friend, the stipulation being that the latter will repay it without interest to the children of the lender. They take care of the ill and the old; old people are never abandoned, and in no case are they killed — unless it be a slave who was ill for a long time. War prisoners are sometimes eaten. The children are very much petted and loved. Old and feeble war prisoners are killed, the others are sold as slaves. They have no religion, no gods, no idols, no authority of any description; the oldest man in the family is the judge. In cases of adultery a fine is paid, and part of it goes to the negoria (the community). The soil is kept in common, but the crop belongs to those who have grown it. They have pottery, and know barter-trade — the custom being that the merchant gives them the goods, whereupon they return to their houses and bring the native goods required by the merchant; if the latter cannot be obtained, the European goods are returned.[89] They are head-hunters, and in so doing they prosecute blood revenge. ‘Sometimes,’ Finsch says, ‘the affair is referred to the Rajah of Namototte, who terminates it by imposing a fine.’”

When well treated, the Papuas are very kind. Miklukho-Maclay landed on the eastern coast of New Guinea, followed by one single man, stayed for two years among tribes reported to be cannibals, and left them with regret; he returned again to stay one year more among them, and never had he any conflict to complain of. True that his rule was never — under no pretext whatever — to say anything which was not truth, nor make any promise which he could not keep. These poor creatures, who even do not know how to obtain fire, and carefully maintain it in their huts, live under their primitive communism, without any chiefs; and within their villages they have no quarrels worth speaking of. They work in common, just enough to get the food of the day; they rear their children in common; and in the evenings they dress themselves as coquettishly as they can, and dance. Like all savages, they are fond of dancing. Each village has its barla, or balai — the “long house,” “longue maison,” or “grande maison” — for the unmarried men, for social gatherings, and for the discussion of common affairs — again a trait which is common to most inhabitants of the Pacific Islands, the Eskimos, the Red Indians, and so on. Whole groups of villages are on friendly terms, and visit each other en bloc.

Unhappily, feuds are not uncommon — not in consequence of “Overstocking of the area,” or “keen competition,” and like inventions of a mercantile century, but chiefly in consequence of superstition. As soon as any one falls ill, his friends and relatives come together, and deliberately discuss who might be the cause of the illness. All possible enemies are considered, every one confesses of his own petty quarrels, and finally the real cause is discovered. An enemy from the next village has called it down, and a raid upon that village is decided upon. Therefore, feuds are rather frequent, even between the coast villages, not to say a word of the cannibal mountaineers who are considered as real witches and enemies, though, on a closer acquaintance, they prove to be exactly the same sort of people as their neighbours on the seacoast.[90]

Many striking pages could be written about the harmony which prevails in the villages of the Polynesian inhabitants of the Pacific Islands. But they belong to a more advanced stage of civilization. So we shall now take our illustrations from the far north. I must mention, however, before leaving the Southern Hemisphere, that even the Fuegians, whose reputation has been so bad, appear under a much better light since they begin to be better known. A few French missionaries who stay among them “know of no act of malevolence to complain of.” In their clans, consisting of from 120 to 150 souls, they practise the same primitive communism as the Papuas; they share everything in common, and treat their old people very well. Peace prevails among these tribes.[91] With the Eskimos and their nearest congeners, the Thlinkets, the Koloshes, and the Aleoutes, we find one of the nearest illustrations of what man may have been during the glacial age. Their implements hardly differ from those of palæolithic man, and some of their tribes do not yet know fishing: they simply spear the fish with a kind of harpoon.[92] They know the use of iron, but they receive it from the Europeans, or find it on wrecked ships. Their social organization is of a very primitive kind, though they already have emerged from the stage of “communal marriage,” even under the gentile restrictions. They live in families, but the family bonds are often broken; husbands and wives are often exchanged.[93] The families, however, remain united in clans, and how could it be otherwise? How could they sustain the hard struggle for life unless by closely combining their forces? So they do, and the tribal bonds are closest where the struggle for life is hardest, namely, in North-East Greenland. The “long house” is their usual dwelling, and several families lodge in it, separated from each other by small partitions of ragged furs, with a common passage in the front. Sometimes the house has the shape of a cross, and in such case a common fire is kept in the centre. The German Expedition which spent a winter close by one of those “long houses” could ascertain that “no quarrel disturbed the peace, no dispute arose about the use of this narrow space” throughout the long winter. “Scolding, or even unkind words, are considered as a misdemeanour, if not produced under the legal form of process, namely, the nith-song.”[94] Close cohabitation and close interdependence are sufficient for maintaining century after century that deep respect for the interests of the community which is characteristic of Eskimo life. Even in the larger communities of Eskimos, “public opinion formed the real judgment-seat, the general punishment consisting in the offenders being shamed in the eyes of the people.”[95]

Eskimo life is based upon communism. What is obtained by hunting and fishing belongs to the clan. But in several tribes, especially in the West, under the influence of the Danes, private property penetrates into their institutions. However, they have an original means for obviating the inconveniences arising from a personal accumulation of wealth which would soon destroy their tribal unity. When a man has grown rich, he convokes the folk of his clan to a great festival, and, after much eating, distributes among them all his fortune. On the Yukon river, Dall saw an Aleonte family distributing in this way ten guns, ten full fur dresses, 200 strings of beads, numerous blankets, ten wolf furs, 200 beavers, and 500 zibelines. After that they took off their festival dresses, gave them away, and, putting on old ragged furs, addressed a few words to their kinsfolk, saying that though they are now poorer than any one of them, they have won their friendship.[96] Like distributions of wealth appear to be a regular habit with the Eskimos, and to take place at a certain season, after an exhibition of all that has been obtained during the year.[97] In my opinion these distributions reveal a very old institution, contemporaneous with the first apparition of personal wealth; they must have been a means for re-establishing equality among the members of the clan, after it had been disturbed by the enrichment of the few. The periodical redistribution of land and the periodical abandonment of all debts which took place in historical times with so many different races (Semites, Aryans, etc.), must have been a survival of that old custom. And the habit of either burying with the dead, or destroying upon his grave, all that belonged to him personally — a habit which we find among all primitive races — must have had the same origin. In fact, while everything that belongs personally to the dead is burnt or broken upon his grave, nothing is destroyed of what belonged to him in common with the tribe, such as boats, or the communal implements of fishing. The destruction bears upon personal property alone. At a later epoch this habit becomes a religious ceremony. It receives a mystical interpretation, and is imposed by religion, when public opinion alone proves incapable of enforcing its general observance. And, finally, it is substituted by either burning simple models of the dead man’s property (as in China), or by simply carrying his property to the grave and taking it back to his house after the burial ceremony is over — a habit which still prevails with the Europeans as regards swords, crosses, and other marks of public distinction.[98]

The high standard of the tribal morality of the Eskimos has often been mentioned in general literature. Nevertheless the following remarks upon the manners of the Aleoutes — nearly akin to the Eskimos — will better illustrate savage morality as a whole. They were written, after a ten years’ stay among the Aleoutes, by a most remarkable man — the Russian missionary, Veniaminoff. I sum them up, mostly in his own words: —

Endurability (he wrote) is their chief feature. It is simply colossal. Not only do they bathe every morning in the frozen sea, and stand naked on the beach, inhaling the icy wind, but their endurability, even when at hard work on insufficient food, surpasses all that can be imagined. During a protracted scarcity of food, the Aleoute cares first for his children; he gives them all he has, and himself fasts. They are not inclined to stealing; that was remarked even by the first Russian immigrants. Not that they never steal; every Aleoute would confess having sometime stolen something, but it is always a trifle; the whole is so childish. The attachment of the parents to their children is touching, though it is never expressed in words or pettings. The Aleoute is with difficulty moved to make a promise, but once he has made it he will keep it whatever may happen. (An Aleoute made Veniaminoff a gift of dried fish, but it was forgotten on the beach in the hurry of the departure. He took it home. The next occasion to send it to the missionary was in January; and in November and December there was a great scarcity of food in the Aleoute encampment. But the fish was never touched by the starving people, and in January it was sent to its destination.) Their code of morality is both varied and severe. It is considered shameful to be afraid of unavoidable death; to ask pardon from an enemy; to die without ever having killed an enemy; to be convicted of stealing; to capsize a boat in the harbour; to be afraid of going to sea in stormy weather, to be the first in a party on a long journey to become an invalid in case of scarcity of food; to show greediness when spoil is divided, in which case every one gives his own part to the greedy man to shame him; to divulge a public secret to his wife; being two persons on a hunting expedition, not to offer the best game to the partner; to boast of his own deeds, especially of invented ones; to scold any one in scorn. Also to beg; to pet his wife in other people’s presence, and to dance with her; to bargain personally: selling must always be made through a third person, who settles the price. For a woman it is a shame not to know sewing, dancing and all kinds of woman’s work; to pet her husband and children, or even to speak to her husband in the presence of a stranger.[99]

Such is Aleoute morality, which might also be further illustrated by their tales and legends. Let me also add that when Veniaminoff wrote (in 1840) one murder only had been committed since the last century in a population of 60,000 people, and that among 1,800 Aleoutes not one single common law offence had been known for forty years. This will not seem strange if we remark that scolding, scorning, and the use of rough words are absolutely unknown in Aleoute life. Even their children never fight, and never abuse each other in words. All they may say is, “Your mother does not know sewing,” or “Your father is blind of one eye.”[100]

Many features of savage life remain, however, a puzzle to Europeans. The high development of tribal solidarity and the good feelings with which primitive folk are animated towards each other, could be illustrated by any amount of reliable testimony. And yet it is not the less certain that those same savages practise infanticide; that in some cases they abandon their old people, and that they blindly obey the rules of blood-revenge. We must then explain the coexistence of facts which, to the European mind, seem so contradictory at the first sight. I have just mentioned how the Aleoute father starves for days and weeks, and gives everything eatable to his child; and how the Bushman mother becomes a slave to follow her child; and I might fill pages with illustrations of the really tender relations existing among the savages and their children. Travellers continually mention them incidentally. Here you read about the fond love of a mother; there you see a father wildly running through the forest and carrying upon his shoulders his child bitten by a snake; or a missionary tells you the despair of the parents at the loss of a child whom he had saved, a few years before, from being immolated at its birth. You learn that the “savage” mothers usually nurse their children till the age of four, and that, in the New Hebrides, on the loss of a specially beloved child, its mother, or aunt, will kill herself to take care of it in the other world.[101] And so on.

Like facts are met with by the score; so that, when we see that these same loving parents practise infanticide, we are bound to recognize that the habit (whatever its ulterior transformations may be) took its origin under the sheer pressure of necessity, as an obligation towards the tribe, and a means for rearing the already growing children. The savages, as a rule, do not “multiply without stint,” as some English writers put it. On the contrary, they take all kinds of measures for diminishing the birth-rate. A whole series of restrictions, which Europeans certainly would find extravagant, are imposed to that effect, and they are strictly obeyed. But notwithstanding that, primitive folk cannot rear all their children. However, it has been remarked that as soon as they succeed in increasing their regular means of subsistence, they at once begin to abandon the practice of infanticide. On the whole, the parents obey that obligation reluctantly, and as soon as they can afford it they resort to all kinds of compromises to save the lives of their new-born. As has been so well pointed out by my friend Elie Reclus,[102] they invent the lucky and unlucky days of births, and spare the children born on the lucky days; they try to postpone the sentence for a few hours, and then say that if the baby has lived one day it must live all its natural life.[103] They hear the cries of the little ones coming from the forest, and maintain that, if heard, they forbode a misfortune for the tribe; and as they have no baby-farming nor crèches for getting rid of the children, every one of them recoils before the necessity of performing the cruel sentence; they prefer to expose the baby in the wood rather than to take its life by violence. Ignorance, not cruelty, maintains infanticide; and, instead of moralizing the savages with sermons, the missionaries would do better to follow the example of Veniaminoff, who, every year till his old age, crossed the sea of Okhotsk in a miserable boat, or travelled on dogs among his Tchuktchis, supplying them with bread and fishing implements. He thus had really stopped infanticide.

The same is true as regards what superficial observers describe as parricide. We just now saw that the habit of abandoning old people is not so widely spread as some writers have maintained it to be. It has been extremely exaggerated, but it is occasionally met with among nearly all savages; and in such cases it has the same origin as the exposure of children. When a “savage” feels that he is a burden to his tribe; when every morning his share of food is taken from the mouths of the children — and the little ones are not so stoical as their fathers: they cry when they are hungry; when every day he has to be carried across the stony beach, or the virgin forest, on the shoulders of younger people — there are no invalid carriages, nor destitutes to wheel them in savage lands — he begins to repeat what the old Russian peasants say until now-a-day. “Tchujoi vek zayedayu, Pora na pokoi!” (“I live other people’s life: it is time to retire!”) And he retires. He does what the soldier does in a similar case. When the salvation of his detachment depends upon its further advance, and he can move no more, and knows that he must die if left behind, the soldier implores his best friend to render him the last service before leaving the encampment. And the friend, with shivering hands, discharges his gun into the dying body. So the savages do. The old man asks himself to die; he himself insists upon this last duty towards the community, and obtains the consent of the tribe; he digs out his grave; he invites his kinsfolk to the last parting meal. His father has done so, it is now his turn; and he parts with his kinsfolk with marks of affection. The savage so much considers death as part of his duties towards his community, that he not only refuses to be rescued (as Moffat has told), but when a woman who had to be immolated on her husband’s grave was rescued by missionaries, and was taken to an island, she escaped in the night, crossed a broad sea-arm, swimming and rejoined her tribe, to die on the grave.[104] It has become with them a matter of religion. But the savages, as a rule, are so reluctant to take any one’s life otherwise than in fight, that none of them will take upon himself to shed human blood, and they resort to all kinds of stratagems, which have been so falsely interpreted. In most cases, they abandon the old man in the wood, after having given him more than his share of the common food. Arctic expeditions have done the same when they no more could carry their invalid comrades. “Live a few days more! May be there will be some unexpected rescue!”

West European men of science, when coming across these facts, are absolutely unable to stand them; they can not reconcile them with a high development of tribal morality, and they prefer to cast a doubt upon the exactitude of absolutely reliable observers, instead of trying to explain the parallel existence of the two sets of facts: a high tribal morality together with the abandonment of the parents and infanticide. But if these same Europeans were to tell a savage that people, extremely amiable, fond of their own children, and so impressionable that they cry when they see a misfortune simulated on the stage, are living in Europe within a stone’s throw from dens in which children die from sheer want of food, the savage, too, would not understand them. I remember how vainly I tried to make some of my Tungus friends understand our civilization of individualism: they could not, and they resorted to the most fantastical suggestions. The fact is that a savage, brought up in ideas of a tribal solidarity in everything for bad and for good, is as incapable of understanding a “moral” European, who knows nothing of that solidarity, as the average European is incapable of understanding the savage. But if our scientist had lived amidst a half-starving tribe which does not possess among them all one man’s food for so much as a few days to come, he probably might have understood their motives. So also the savage, if he had stayed among us, and received our education, may be, would understand our European indifference towards our neighbours, and our Royal Commissions for the prevention of “babyfarming.” “Stone houses make stony hearts,” the Russian peasants say. But he ought to live in a stone house first.

Similar remarks must be made as regards cannibalism. Taking into account all the facts which were brought to light during a recent controversy on this subject at the Paris Anthropological Society, and many incidental remarks scattered throughout the “savage” literature, we are bound to recognize that that practice was brought into existence by sheer necessity; but that it was further developed by superstition and religion into the proportions it attained in Fiji or in Mexico. It is a fact that until this day many savages are compelled to devour corpses in the most advanced state of putrefaction, and that in cases of absolute scarcity some of them have had to disinter and to feed upon human corpses, even during an epidemic. These are ascertained facts. But if we now transport ourselves to the conditions which man had to face during the glacial period, in a damp and cold climate, with but little vegetable food at his disposal; if we take into account the terrible ravages which scurvy still makes among underfed natives, and remember that meat and fresh blood are the only restoratives which they know, we must admit that man, who formerly was a granivorous animal, became a flesh-eater during the glacial period. He found plenty of deer at that time, but deer often migrate in the Arctic regions, and sometimes they entirely abandon a territory for a number of years. In such cases his last resources disappeared. During like hard trials, cannibalism has been resorted to even by Europeans, and it was resorted to by the savages. Until the present time, they occasionally devour the corpses of their own dead: they must have devoured then the corpses of those who had to die. Old people died, convinced that by their death they were rendering a last service to the tribe. This is why cannibalism is represented by some savages as of divine origin, as something that has been ordered by a messenger from the sky. But later on it lost its character of necessity, and survived as a superstition. Enemies had to be eaten in order to inherit their courage; and, at a still later epoch, the enemy’s eye or heart was eaten for the same purpose; while among other tribes, already having a numerous priesthood and a developed mythology, evil gods, thirsty for human blood, were invented, and human sacrifices required by the priests to appease the gods. In this religious phase of its existence, cannibalism attained its most revolting characters. Mexico is a well-known example; and in Fiji, where the king could eat any one of his subjects, we also find a mighty cast of priests, a complicated theology,[105] and a full development of autocracy. Originated by necessity, cannibalism became, at a later period, a religious institution, and in this form it survived long after it had disappeared from among tribes which certainly practised it in former times, but did not attain the theocratical stage of evolution. The same remark must be made as regards infanticide and the abandonment of parents. In some cases they also have been maintained as a survival of olden times, as a religiously-kept tradition of the past.

I will terminate my remarks by mentioning another custom which also is a source of most erroneous conclusions. I mean the practice of blood-revenge. All savages are under the impression that blood shed must be revenged by blood. If any one has been killed, the murderer must die; if any one has been wounded, the aggressor’s blood must be shed. There is no exception to the rule, not even for animals; so the hunter’s blood is shed on his return to the village when he has shed the blood of an animal. That is the savages’ conception of justice — a conception which yet prevails in Western Europe as regards murder. Now, when both the offender and the offended belong to the same tribe, the tribe and the offended person settle the affair.[106] But when the offender belongs to another tribe, and that tribe, for one reason or another, refuses a compensation, then the offended tribe decides to take the revenge itself. Primitive folk so much consider every one’s acts as a tribal affair, dependent upon tribal approval, that they easily think the clan responsible for every one’s acts. Therefore, the due revenge may be taken upon any member of the offender’s clan or relatives.[107] It may often happen, however, that the retaliation goes further than the offence. In trying to inflict a wound, they may kill the offender, or wound him more than they intended to do, and this becomes a cause for a new feud, so that the primitive legislators were careful in requiring the retaliation to be limited to an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and blood for blood.[108]

It is remarkable, however, that with most primitive folk like feuds are infinitely rarer than might be expected; though with some of them they may attain abnormal proportions, especially with mountaineers who have been driven to the highlands by foreign invaders, such as the mountaineers of Caucasia, and especially those of Borneo — the Dayaks. With the Dayaks — we were told lately — the feuds had gone so far that a young man could neither marry nor be proclaimed of age before he had secured the head of an enemy. This horrid practice was fully described in a modern English work.[109] It appears, however, that this affirmation was a gross exaggeration. Moreover, Dayak “head-hunting” takes quite another aspect when we learn that the supposed “headhunter” is not actuated at all by personal passion. He acts under what he considers as a moral obligation towards his tribe, just as the European judge who, in obedience to the same, evidently wrong, principle of “blood for blood,” hands over the condemned murderer to the hangman. Both the Dayak and the judge would even feel remorse if sympathy moved them to spare the murderer. That is why the Dayaks, apart from the murders they commit when actuated by their conception of justice, are depicted, by all those who know them, as a most sympathetic people. Thus Carl Bock, the same author who has given such a terrible picture of head-hunting, writes:

“As regards morality, I am bound to assign to the Dayaks a high place in the scale of civilization.... Robberies and theft are entirely unknown among them. They also are very truthful.... If I did not always get the ‘whole truth,’ I always got, at least, nothing but the truth from them. I wish I could say the same of the Malays” (pp. 209 and 210).

Bock’s testimony is fully corroborated by that of Ida Pfeiffer. “I fully recognized,” she wrote, “that I should be pleased longer to travel among them. I usually found them honest, good, and reserved... much more so than any other nation I know.”[110] Stoltze used almost the same language when speaking of them. The Dayaks usually have but one wife, and treat her well. They are very sociable, and every morning the whole clan goes out for fishing, hunting, or gardening, in large parties. Their villages consist of big huts, each of which is inhabited by a dozen families, and sometimes by several hundred persons, peacefully living together. They show great respect for their wives, and are fond of their children; and when one of them falls ill, the women nurse him in turn. As a rule they are very moderate in eating and drinking. Such is the Dayak in his real daily life.

It would be a tedious repetition if more illustrations from savage life were given. Wherever we go we find the same sociable manners, the same spirit of solidarity. And when we endeavour to penetrate into the darkness of past ages, we find the same tribal life, the same associations of men, however primitive, for mutual support. Therefore, Darwin was quite right when he saw in man’s social qualities the chief factor for his further evolution, and Darwin’s vulgarizers are entirely wrong when they maintain the contrary.

The small strength and speed of man (he wrote), his want of natural weapons, etc., are more than counterbalanced, firstly, by his intellectual faculties (which, he remarked on another page, have been chiefly or even exclusively gained for the benefit of the community), and secondly, by his social qualities, which led him to give and receive aid from his fellow men.[111]

In the last century the “savage” and his “life in the state of nature” were idealized. But now men of science have gone to the opposite extreme, especially since some of them, anxious to prove the animal origin of man, but not conversant with the social aspects of animal life, began to charge the savage with all imaginable “bestial” features. It is evident, however, that this exaggeration is even more unscientific than Rousseau’s idealization. The savage is not an ideal of virtue, nor is he an ideal of “savagery.” But the primitive man has one quality, elaborated and maintained by the very necessities of his hard struggle for life — he identifies his own existence with that of his tribe; and without that quality mankind never would have attained the level it has attained now.

Primitive folk, as has been already said, so much identify their lives with that of the tribe, that each of their acts, however insignificant, is considered as a tribal affair. Their whole behaviour is regulated by an infinite series of unwritten rules of propriety which are the fruit of their common experience as to what is good or bad — that is, beneficial or harmful for their own tribe. Of course, the reasonings upon which their rules of propriety are based sometimes are absurd in the extreme. Many of them originate in superstition; and altogether, in whatever the savage does, he sees but the immediate consequences of his acts; he cannot foresee their indirect and ulterior consequences — thus simply exaggerating a defect with which Bentham reproached civilized legislators. But, absurd or not, the savage obeys the prescriptions of the common law, however inconvenient they may be. He obeys them even more blindly than the civilized man obeys the prescriptions of the written law. His common law is his religion; it is his very habit of living. The idea of the clan is always present to his mind, and self-restriction and self-sacrifice in the interest of the clan are of daily occurrence. If the savage has infringed one of the smaller tribal rules, he is prosecuted by the mockeries of the women. If the infringement is grave, he is tortured day and night by the fear of having called a calamity upon his tribe. If he has wounded by accident any one of his own clan, and thus has committed the greatest of all crimes, he grows quite miserable: he runs away in the woods, and is ready to commit suicide, unless the tribe absolves him by inflicting upon him a physical pain and sheds some of his own blood.[112] Within the tribe everything is shared in common; every morsel of food is divided among all present; and if the savage is alone in the woods, he does not begin eating before he has loudly shouted thrice an invitation to any one who may hear his voice to share his meal.[113]

In short, within the tribe the rule of “each for all” is supreme, so long as the separate family has not yet broken up the tribal unity. But that rule is not extended to the neighbouring clans, or tribes, even when they are federated for mutual protection. Each tribe, or clan, is a separate unity. Just as among mammals and birds, the territory is roughly allotted among separate tribes, and, except in times of war, the boundaries are respected. On entering the territory of his neighbours one must show that he has no bad intentions. The louder one heralds his coming, the more confidence he wins; and if he enters a house, he must deposit his hatchet at the entrance. But no tribe is bound to share its food with the others: it may do so or it may not. Therefore the life of the savage is divided into two sets of actions, and appears under two different ethical aspects: the relations within the tribe, and the relations with the outsiders; and (like our international law) the “inter-tribal” law widely differs from the common law. Therefore, when it comes to a war the most revolting cruelties may be considered as so many claims upon the admiration of the tribe. This double conception of morality passes through the whole evolution of mankind, and maintains itself until now. We Europeans have realized some progress — not immense, at any rate — in eradicating that double conception of ethics; but it also must be said that while we have in some measure extended our ideas of solidarity — in theory, at least — over the nation, and partly over other nations as well, we have lessened the bonds of solidarity within our own nations, and even within our own families.

The appearance of a separate family amidst the clan necessarily disturbs the established unity. A separate family means separate property and accumulation of wealth. We saw how the Eskimos obviate its inconveniences; and it is one of the most interesting studies to follow in the course of ages the different institutions (village communities, guilds, and so on) by means of which the masses endeavoured to maintain the tribal unity, notwithstanding the agencies which were at work to break it down. On the other hand, the first rudiments of knowledge which appeared at an extremely remote epoch, when they confounded themselves with witchcraft, also became a power in the hands of the individual which could be used against the tribe. They were carefully kept in secrecy, and transmitted to the initiated only, in the secret societies of witches, shamans, and priests, which we find among all savages. By the same time, wars and invasions created military authority, as also castes of warriors, whose associations or clubs acquired great powers. However, at no period of man’s life were wars the normal state of existence. While warriors exterminated each other, and the priests celebrated their massacres, the masses continued to live their daily life, they prosecuted their daily toil. And it is one of the most interesting studies to follow that life of the masses; to study the means by which they maintained their own social organization, which was based upon their own conceptions of equity, mutual aid, and mutual support — of common law, in a word, even when they were submitted to the most ferocious theocracy or autocracy in the State.

#mutual aid#community organizing#anarchism#anarchists#anarchy works#anti capitalism#anti capitalist#communism#daily posts#community building#late stage capitalism#leftism#libraries

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

LO Fans: "I love Lore Olympus because it deals with serious themes, like sexual assault, abuse, gaslighting, trauma, and mental health issues!"

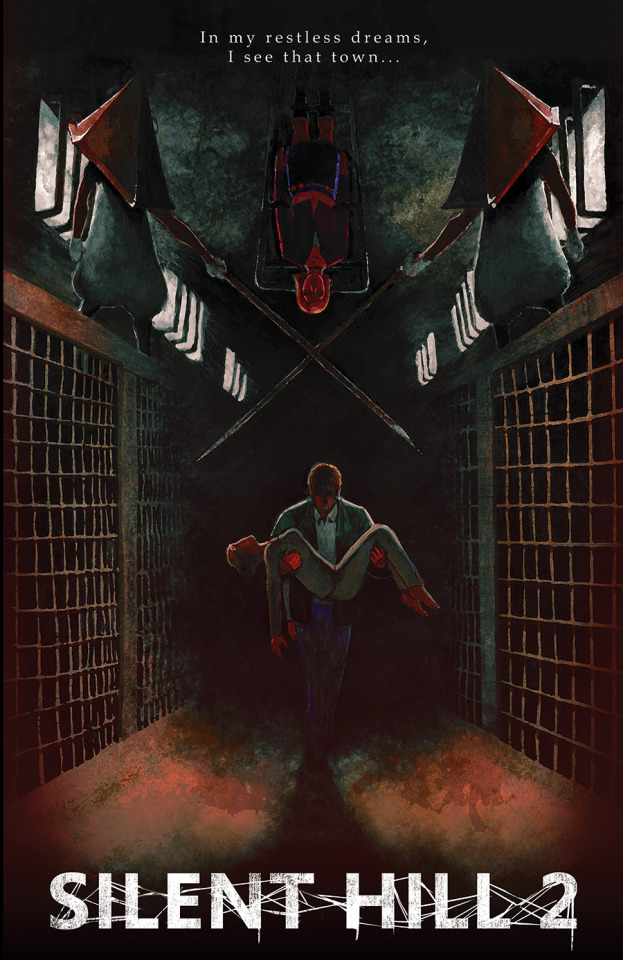

Me, who spent my life discovering and obsessing over masterpieces like this:

"You're gonna have to try a lot harder than that to impress me."

Yeah, I never understood that kind of praise. For one thing, people act like LO is groundbreaking for that reason, despite there being countless movies, books, tv shows, comics, and video games that also deal with the same themes. That isn't to say there can't be more stories like this, however. I, for one, am begging for another video game that comes close to the emotional resonance of Silent Hill 2, or for a faithful adaptation of Dracula and/or Phantom of the Opera, or for a horror movie as unsettling as The Howling! But to say any new story that deals with these themes is unique for doing so, is just simply not true. Lore Olympus is no more unique than any of these stories. Also, I don't understand the praise that Lore Olympus is great just by virtue of having these themes in the first place. Just because a story has serious themes, doesn't automatically make it good. Far too often does LO use its themes as a crutch for a plot that is standard issue among romances, as opposed to stories like The Howling, which has a very intriguing, outlandish plot that serves as a catalyst to explore themes of very real and relatable horror. Lore Olympus, without its intense themes, is just another story about the CEO falling in love with his intern. And don't get me wrong, I LOVE those kinds of stories, but Lore Olympus just doesn't really do it for me. And the poorly executed themes just hamper it even further for me.

If it wasn't already apparent, has anyone noticed a pattern between these titles? All but one are horror stories. In my opinion, that is one of the key differences between them and LO: Horror! The themes within, are ones that illicit terror, and the stories reflect that (even Phantom of the Opera--don't listen to anyone who says it's a romance). Starting with Dracula, one of the scenes that horrified me the most in the book was the one where Count Dracula sneaks into Mina's bedroom. The book describes him slitting open his own vein and forcing her to drink his blood. Mina then expresses feelings of violation, much akin to what rape survivors feel. It doesn't pull any punches in its shocking, horrific portrayal, but it never comes off as exploitative. That's because the best horror stories rely on the audience's empathy. In this case, nobody wants to feel violated, so we feel as horrified as the characters do when we read about this grotesque event. And because it is about illiciting fear through empathy, Dracula succeeds where Lore Olympus fails. Lore Olympus, before all else, is a romance. And rape should not be in a romantic story. Especially not when the narrative of LO uses this trauma to validate the relationship between the two leads. I'm not a fan of stories that use trauma to validate a relationship between romantic interests, and I think that partly stems from reading the Phantom of the Opera.

If you ask me, Phantom of the Opera is one if the best books to discuss abuse and gaslighting ever written! Despite misconceptions generated by the popularity of the musical, PotO is very much a horror story with hardly any romance at all. And it's one of the best examples about why using trauma to validate a romance is a very bad idea! You see, all the conflict of the story begins with The Phantom and his trauma. He was born with multiple physical deformities that cause him to look like a living corpse. Because of this, he is despised and rejected by the world in order to escape the hatred of the world, he commissions the construction of the Paris Opera House, complete with intricate catacombs where he can live out the rest of his miserable days. Then one day, a woman named Christine comes to work at the Opera as a chorus girl. She is sad and alone due to her being orphaned, without a friend in the world. She too is emotionally damaged and the Phantom thinks this means she'll understand him. The trouble begins instantly when he claims to be a character from a folktale that Christine's father used to tell her. This is when the manipulation and gaslighting begins. Part of what makes this so effective is how we see it from an outside perspective. The protagonist, Raoul, is in love with Christine and we get to see his confusion and growing concern when he starts realizing Christine is showing signs of an abusive relationship. What makes the relationship even worse is the fact that Christine actually does understand The Phantom. So she doesn't run away not only out of fear, but also compassion. She knows what it's like to feel isolated and dead to the world and The Phantom uses that against her. The more I describe this, the more parallels I begin to see to Hades' and Minthe's relationship. Yes, Minthe abused Hades in much of the same way as The Phantom abused Christine. Notice how Minthe keeps convincing Hades that they're the only people who understand each other, even going so far as to say, "We're the same." The funny thing is, that's exactly what the narrative uses to validate Hades' and Persephone's relationship! It tries to establish that Hades and Persephone relate to each other and they say, several times, "We're the same," to each other. But this is exactly how Hades got stuck in a toxic relationship with Minthe, so why is it suddenly okay now? Relationships that use shared trauma to validate themselves are almost always doomed to become toxic, in one way or another.

So what about the healthy relationship in Phantom of the Opera? Well, it's kinda interesting actually. You see, Christine eventually comes to realize that she needs help, so she turns to the protagonist, Raoul, to get her away from the Phantom. Raoul has an interesting character arc because he starts the novel being pretty immature and kinda selfish. He doesn't really take Christine's feelings into consideration. It's more like a boy chasing his childhood crush (actually that's exactly what happens). However, over the course of the story, as he becomes increasingly concerned with her well-being, he learns to care more about her feelings and her needs. This culminates in the climax, when he's willing to crawl through hell itself for her sake. I bring all this up because I wanted to compare Raoul with Hades as well. Hades is a very consistent character. He doesn't need an arc like Raoul because, from the very beginning, he's willing to put all of Persephone's needs before his, to a fault! That is his entire purpose within the narrative of LO. He exists to serve Persephone. Raoul didn't exist to serve Christine. He had his own journey of growing and maturing. And Christine didn't exist to serve Raoul either. It bothers me that a novel from 1910 has a more well-rounded relationship than a modern comic! Actually, now that I think about it, isn't Persephone's entire character arc supposed to be her learning that she shouldn't exist to serve others? Well, that totally contradicts Hades' role in the story, doesn't it? He exists to serve her! I guess, in the eyes of LO, it's only okay if men serve women, but not for women to serve men. Newsflash: neither is okay.

Now Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) remains, to this day, one of the most terrifying movies I've ever seen! That's all thanks to its brutal depictions of domestic abuse. So Dr. Henry Jekyll believes the solution to enlightening the human race is to separate the good and evil in our souls. He solves this problem by creating a drug to do just that, which transforms him into Edward Hyde, but he becomes addicted and starts terrorizing a woman who was once a former patient of his. I think what makes this so effective, when compared to LO, is one simple factor: Fear. I am terrified of Edward Hyde, but whenever Apollo shows up, I'm just annoyed. That's because Hyde isn't being used to sell an agenda, while Apoll is. Apollo is all about making a statement about toxic masculinity, which always bothered me from the very beginning! Being an abusive cunt who rapes women has nothing to do with masculinity! It doesn't matter if you're masculine or feminine, anyone can be a cunting abusive rapist. If you are a rapist, it's because you're a monster who lacks empathy, not because of masculinity. And if you think masculinity has something to do with a lack of empathy, fuck off! Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is not about toxic masculinity. It's about how drug addiction can often hurt other people around us just as much, if not moreso, than ourselves. It also doesn't use rape to validate a relationship between characters. I'm sorry, but that is just the laziest storytelling technique. When the antagonist is a rapist OF COURSE the male love interest is going to look better by comparison! But when you take Apollo out of the equation, Hades stops looking like a desirable love interest real fucking quick.

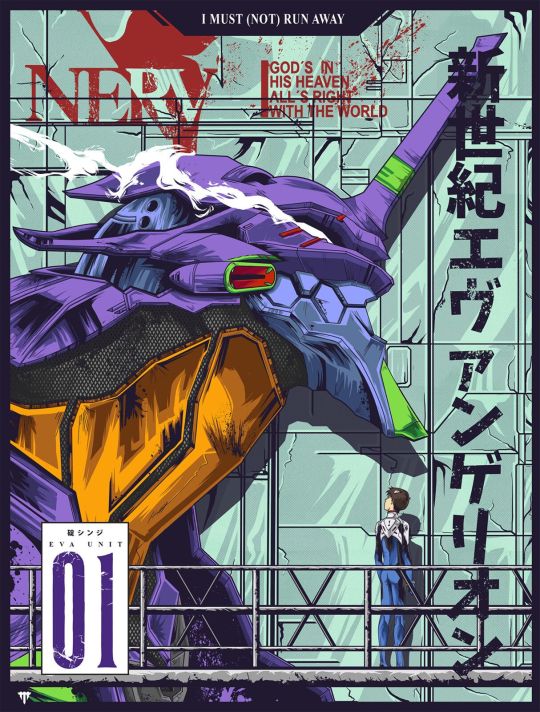

So yeah, I think Hades makes for a bad love interest. That's mostly because he's so much like Shinji Ikari from Neon Genesis Evangelion. Yeah, the one title from the list above that's not a horror, but is no less relevant. The thing is, both Hades and Shinji have a lot in common, such as hating themselves, having a bad relationship with their father, and not caring at all about their own wants and needs. Oh, also Asuka's a better written character than Minthe, but that's a whole other topic. What makes Evangelion work, in my opinion, is that Shinji's whole journey is about learning to love himself, while Hades is portrayed as being perfect the way he is. Hades in LO is like a flawless beacon of virtue, solely because he worships the ground Persephone walks on. But the guy just doesn't care about himself at all! Like I said earlier, Hades guilty of the same self-destructive behaviors as Persephone but he's praised for it, while Persephone is encouraged to look after herself more often. Compare this to Shinji, whose life only gets worse the more he neglects himself. The only time Hades does something beneficial for himself is when he breaks up with Minthe, but immediately after that, he starts devoting every ounce of energy to Persephone! All that matters is her! He doesn't give a single fuck about himself. Sorry, but that's not good qualities in a male love interest. In all fairness, this is a problem with the romance genre as a whole. Most romances give priority to the protagonist (in this case Persephone) while neglecting the love interest (Hades). It's why I have a serious problem with the entire genre.

Now what could Silent Hill 2 have that is in any way relevant to Lore Olympus? Two words: Nightmare Fuel. Personifying trauma as literal demons is one of the smartest ideas anyone's ever had, because speaking from personal experience, that's how it feels. I just don't feel like the trauma experienced by the characters in LO is a waking nightmare like it is in real life. For one, the characters' trauma only pops up when it's convenient for the plot. Like whenever Persephone starts experiencing ptsd, it happens when she's with Hades so we can get a scene with Hades cuddling her. After that, it shows up in a scene to make her look badass by confronting Apollo. No, just no. The Howling did it better too, by making the protagonist's trauma such an inconvenience in her life! I never felt that way in LO. When you uss traumatic encounters to make your character look like a badass, kindly fuck off.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been thinking about Naomi Novik's A Deadly Education via @sortinghatchats. Please enjoy my word vomit.

Orion is such a Lion Lion. At first I thought he might be a Badger primary, because he's very about the inherent value of a human life, and has a lack of curiosity about the potential humanity of the mals he so easily kills. But then I realized Orion doesn't really get that value for human life from his community, who are much choosier about who they choose to value. In fact, Orion feels very separate from his community and is more or less okay with that. He feels isolated because nobody sees the ‘real him’ (internal primary), not because he lacks a community in general. Thus, Lion primary. And then, the charging ahead? His Lion secondary is a no brainer.

Miss Galadriel Higgins is who really fascinates me. El's got a tidy little Bird secondary, which loves to scream at Orion's Lion secondary. "What do you mean you took a shower alone? Why didn't you have someone watch your back? WHERE IS YOUR SYSTEM???" She’s very systematic in the way she goes about her school life, which speaks to how consistently she’s taking in and classifying information to make use of later. But El’s primary is a little more difficult - at least, for her.

El wants to be a Snake primary and truly believes that that's the best way to negotiate the world and her survival in it. And over and over, the book delights in making her choose, will El take an opportunity to further her own goals and those of the people she cares about? Or is she going to do what's right, with no benefit to herself or her circle? El picks the latter, every time, and kicks herself for it. El’s Snake model is so strong because she fully believes she's doing the wrong thing and making the wrong choices with her Lion primary. That's probably why Orion rubs her so wrong at first - he wears his Lion proudly, whereas El hides hers because she knows how costly it can be.

I don’t know that El is a burnt Lion, exactly. She didn’t make a bad decision from her gut that made her question her own instincts, and she doesn’t begrudgingly use a Snake model while longing to be able to trust herself. Instead, she wholeheartedly wishes that she wasn't an idealist while fully committing, without compromise, to upholding her ideals.

The closest thing to a burning El had was that terrible experience when she was a child and her mom was sick. El expected help from others because that's what was right, and when it didn't come it really shook her faith that "right" was something that existed, or at least something she got to be a part of. That’s not what I usually see held up as an example of burning though, so I’m not sure it applies. Maybe a better term would be that she has an immature primary. She uses it, but she wishes she was more like the people she sees succeeding. Over time, perhaps she’ll learn to love her outstanding idealism, the way her friends do.

An overall theme of this first book was very much “Someone with a Snake model so strong they tricked themselves into thinking it was their actual primary discovers their own Lion primary, to their horror.” And I love that.

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

top 5 best hannibal takes and worst hannibal takes. go

okay i’m going to do this generally on what other people’s takes (that i’ve seen or read somewhere) are because none of my hannibal takes are bad.

top 5 best:

that margot should have been butch in the tv show and that the margot/alana romance could have been developed a little more, i’ll elaborate more on the butch angle in top 5 worst, but i think while i enjoy marlana in s3 (who doesn’t) i do think that there could have been a Little More to it, especially since there was admittedly a lot of gratuitous metaphorical work on a visual or verbal level in early s3 that didn’t... really do much after the first few, and that i think bryan fuller definitely got a bit self-indulgent. while i love s3 i think it was weaker because it got quite ensnared in feeling like it had to explain everyone’s individual recovery (not a bad thing necessarily and the looping narrative definitely had this feeling of “time has been changed, mutilated, adjusted after mizumono”, but on a narrative level it could have probably still been achieved but left more room for things to. Happen) and i think that some of the excess could have been trimmed to allow for more margot-alana development beyond simply talking about taking revenge, i would have loved to see some genuine conversation that only affected both of them that made us realise just why alana would raise the child with her, why they would get marriedーalana having very little dating life and presumably trauma around relationships since her immediate ex tried to murder her and is also a serial killer, and margot having been traumatised repeatedly due to being a lesbian in a very homophobic family, they deserved some space in order to explore why exactly they mean a lot to each other. even a singular scene that didn’t depend on taking vengeance on the men who hurt them would have given us enough i think.