#partly because critical role but also there's about 4 other things that are contributing to my general wildness at this moment

Text

*running in circles, bouncing off the walls*

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

I am having many Emotions.

#I am having emotions I was not prepared for#morrigan.text#where's that meme that's like ?#that's me right now#partly because critical role but also there's about 4 other things that are contributing to my general wildness at this moment#and those would be:#1) I missed a conversation about the Grishaverse in a discord serve I'm in which prompted my Many Opinions to rise to the surface#2) I answered an ask earlier that's scheduled for tomorrow that's about how my OCs define love. It breaks me a little.#3) I'm still not over Doctor Who and I saw my post about Smile and Thin Ice and I was reminded of my Many Thoughts about season 10's finale#4) I have just been generally emotionally unstable the past couple days and that is probably (definitely) playing a part in this

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whatever Happened to: Sheska?

So, as promised, the first of hopefully many posts of the ‘Whatever Happened to’ series, where I bring up characters that just, fell off the map. For our first one we will begin with a character disappearance that always confused me, Sheska from Fullmetal Alchemist Manga and the Brotherhood anime

There will be Spoilers for the story so if you haven’t read/watched it then...maybe you should

When was she last Seen?

While in the 2003 anime series Sheska maintained a recurring role as Winry’s female friend and helping uncover the dirty secrets hidden by the Homunculi and in turn the Military.

However, in the Manga and Brotherhood anime, Sheska is last seen in Chapter 34/Episode 16, both titled ‘Footsteps of a Comrade-in-Arms’. In it she is revealed to be covering for Mustang as he digs for information regarding Hughes’ death - mainly out of solidarity since Hughes did give her the job that pays her bills and keeps her mother in a nice home, and the least she can do is assist in helping find the culprit. She unfortunately lets this slip to ‘Captain Focker/Fokker’ who is Envy in disguise (but still a Focker if you ask me), which leads to the whole Maria Ross frame-up.

From there we never see or hear from Sheska again, we don’t see her at Central when it’s attacked by Briggs, we don’t see her fall victim of the countrywide transmutation circle and do not we see her in the Chapter 107 splash

Which, frankly, is ridiculous given that characters dead, alive and barely in the story like Sheska was are here, including Fu, Hughes, Grumman, some no-names in the bottom and one no-name at the top right corner, Rebecca, Mustang’s old Ishval squad and Henschel. An oversight maybe, but it still leaves the question mark, what DID happen to Sheska?

Theory 1: Sheska was Murdered

Leaking that she knew about Mustang’s digging, covering for him and her photographic memory is two very dangerous tidbits of knowledge for one person to have, even if the Homunculi look down on humans up to this point they have been extremely efficient in not leaking their own information. So a worst case scenario could be that the Homunculi killed Sheska, quietly disposing of her and maybe even covering it up, she was on a heavy workload and could’ve ‘crumbled’ and disappeared to work in a nice undisclosed village. The fortunate thing that goes against this theory is that Mustang would notice, and since Hughes’ death she had been a lot more relaxed with her workload, it would also be in the Homunculi’s nature to only take care of things when it looks like a critical moment.

Another plausible way Sheska may’ve died is via the Mannequins or when Our Father freaking Kamehameha’d half of Central Command, but then she would have to be fighting the Mannequins and not escaped Central when the Briggs soldiers gave them a chance, and Sheska would run if she were there. She may’ve also suffocated under a mountain of books like how she almost did when we first saw her, if she ever actually gets to go home anymore.

Theory 2: Sheska was Dishonorably Discharged

Given that Mustang is treated with contempt for digging into the Hughes case and his actions in making people believe that he scorched Maria Ross, it would be possible that the higher ups would use this as an excuse to discharge her from the military, to sever a connection Mustang would have in Central who could provide him information on Father’s plans. Envy may’ve been a lighter hand as Focker but Focker himself or any other members of Bradley’s high council may opt to picture it as harboring criminal activity. Sheska isn’t exactly one to come crying to the Elrics about this either so it’s not like it’d be huge news, the reason this may not work however is that Sheska still has all the dots Hughes had, she just hasn’t connected them yet, and the Homunculi keep tabs on people like that.

Theory 3: Sheska was Transferred

Like most of Mustang’s crew, Sheska may’ve been moved by association. Her absence from Central Command would fuel this and after she’s finished completing all the records there’s not much else she is useful for in the eyes of the military. Since she has no career goals, she could’ve simply been moved to a smaller military office - her ignorance to the happenings protecting her from being in warzones but not out of the country circle’s range. She may’ve also been transferred normally, maybe another library got burned down or maybe they rebuilt the Central Library and had her repopulate that with all the normal books and secret alchemy cookbooks and actually declutter her apartment with all the books that are there (okay it bothers me, where does she sleep? Does she have a book bed, next to her book oven and book fridge and cooks book eggs for bookfast in her book pan in her book kitchen?).

Theory 4: Sheska left the Military on her own accord

While she never expressed displeasure in working for the Military we leave Sheska in a pivotal moment in the plot, the next episode/chapter Mustang supposedly burns Maria Ross to a crisp. Not knowing it part of the plan, Sheska may’ve felt partly responsible in the ‘murder’ of Ross and disgusted by Mustang’s actions, which could have led her to leave the military.

There are other reasons she may’ve quit her job also, she may’ve found a new calling or as said before the Library could’ve been rebuilt and she could’ve gotten her old job back from that or another closer-to-mother library/general job, she may’ve left to tend to her ill mother if her condition worsened or simply moved to a job with a career track - hell if you wanna go wild maybe she went to become an Alchemist, that photographic memory would be handy if she had the aptitude. The backdrop of this like the previous theory of her leaving the military is that this’d prevent the Homunculi from keeping tabs on her, while it is possible that Ross’ death would’ve prompted her to leave, the military may’ve offered an alternative of transfer or another government job so to keep and eye on her.

Theory 5: Sheska slept through the whole thing

A comical theory, but the records department isn’t something one would frequent in a lot, I mean Mustang was able to sleep in a storeroom for a bit completely undetected. It would be funny if Sheska did miss all the action from falling into a comatose sleep in a basement or something having been overworked, and given the isolated placement completely missed the Mannequin Soldiers, thought the Circle stealing her soul was a nightmare and then napped again through the whole Father fight. This is unlikely because it obviously didn’t happen, as I said Sheska’s workload doesn’t take a huge toll on her anymore so she wouldn’t pass out...not until after the Father Fight when she has to rewrite all the paperwork destroyed by Father’s Kamehameha, it’d be a good laugh though.

Theory 6: Sheska was there, you just didn’t see her

One of the most plausible theories is simply that it happened but there was no need to focus on Sheska while it was happening. Falman also had a great memory and worked with the Briggs men and the Armstrongs had worked in Central for months, so her talents weren’t exactly needed for the situation, she likely escaped the mannequins and left Central Command intact. It’s likely but it’s still annoying, we could have shown her in this scenario, even if it’s when Buccaneer saved those women (imaged in manga since I couldn’t find a screen of the scene in anime) they could’ve thrown in Sheska, could’ve shown her losing and regaining her soul, at least some closure on that would’ve been nice given that we saw every other player and the people of Liore during the Promised Day.

Theory 7: Sheska still works for the Military, she just wasn’t There

The final theory that is as plausible as the prior, Sheska was basically away that day. We saw it with Brosh who only arrived at the scene because he was disgusted by Mustang and then elated that Ross was alive, a ‘bookworm’ like Sheska may’ve taken time off to witness an eclipse, and if she didn’t she may’ve simply had the day off. Another thing she could’ve done is gone on holiday, I doubt she went to Xing to meet the Armstrongs while they were statue hunting but maybe she went out of Central. She could’ve visited her mother, visited other family, gone to a place with other libraries and stuff she may have hobbies in. The downfall of this theory is that none of it escapes the circle, hostilities with Creta, Aurego and Drachma mean the only way out of the country is by crossing the desert, which doesn’t seem up Sheska’s alley, which means we circle back to why didn’t we show her? We showed Liore, Kanama, Resembool and Rush Valley, the latter just to specifically show Paninya - someone who had less screen time than Sheska, no offence to Paninya but if we gave time for her lying on a random floor (lucky she wasn’t fixing a roof) we could’ve just put Sheska in a room face first in a book for a second and that’d be that.

So yeah, the mystery of Sheska racks my brain, mainly out of desire for closure but also because she still played a valid part in Ed and Al’s journey. Without her they would’ve never obtained Marcoh’s notes, which meant they would never have found out the properties of a stone, they would’ve never gone to the Fifth Laboratory and thus never learned about the Homunculi marking them as a sacrifice - since Ross got framed because of her, Ed would’ve never gone to Xerxes either, meaning he wouldn’t have figured out the transmutation circle or found the Ishvalan slum to discover that Scar killed the Rockbells, that discovery led to the confrontation that became a turning point for Scar’s redemption arc too. Sheska also inadvertently was necessary for Mustang’s plot also; had the brothers not gone to the Fifth Laboratory they would’ve never gotten Barry the Chopper as an ally (who in turn busted Ling out of jail, meaning everything Ling contributes to is a byproduct of Sheska’s action) but if she hadn’t have told Envy about Mustang’s digging they would’ve never framed Ross, which meant that they never would’ve had opportunity to capture Gluttony, kill Lust or discover that Bradley was Wrath.

These are big things as well! Could someone just like, poke Arakawa for an answer? Or are we just gonna expect a Launch situation (save her for another day).

Out of the 7 theories I would rank them as

Most to Least Likely: 6, 7, 3, 4, 2, 1, 5

Most to Least Preferred: 3, 5, 7, 4, 6, 2, 1

Maybe one day we’ll find out, but for now it’s all headcanon, but whatever did happen to her, she is not forgotten.

#fma#fmab#fullmetal alchimist brotherhood#fullmetal alchemist#theories#sheska#fullmetal alchemist brotherhood

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I’m gonna do the thing and just get my complaints with the show out, if you’re not interested in reading criticisms (half of which are just being attached to the way things were in the book) please ignore this, I’m going to say all sorts of nice things in a minute. Also please don’t rb this one. If we’ve talked before feel free to comment or disagree, if we haven’t please don’t just this once—I’m usually happy to have people jump off things, but I just got back and I’m not in the mood to start any Discussions just now. Cool thanks!

1. I’m not saying that the show going in for more angst and making some of the central characters more insecure and making Aziraphale and Crowley’s relationship more tenuous and uncertain was *objectively* the wrong choice. I mean I could argue that it was but ultimately it’s probably more just different than right or wrong. But it did make me realize how much I had appreciated having a fandom that was built around material that for all its angst potential (which I also enjoyed) was so fundamentally cozy.

2. Yes I am of course going to take issue with Anathema and Newt. For the record I found Newt notably more likable in the show than the book, even if watching Anathema have sex with a guy she had shown no interest in just because a book told her to was even more uncomfortable than reading it. And there was more of a sense of mutuality in the show—partly because of Adria Arjona playing Anathema as genuinely liking and being charmed by Newt at times, and partly because Newt actually does offer her emotional support and contributes to decision-making at several points instead of only with the “do you want to be a descendent for the rest of your life” line at the end. And that’s nice—mutuality in a relationship is important! The lack of it is one of my biggest issues with their relationship in the book! What really gets to me here is that they got to that mutuality not through strengthening Newt’s character but by weakening Anathema’s—by making her more uncertain and insecure so that Newt could sweep in to support her. And look—obviously there’s nothing wrong with female characters having insecurities and needing support, like everyone does. But we’ve got an awful shortage of weird-looking female characters who swagger around with breadknives and bucketloads of well-earned confidence and decide to try and stop the apocalypse without being told because it’s worth a shot, and the fact that they seem to have undercut her confidence and independence specifically so that she would have to lean on the sub-par dude she’s saddled with as a love-interest reeeally rubs me the wrong way. (Shoutout to my brother for pinpointing this before I was able figure out exactly what was bothering me).

3. Okay and while I’m on the topic of Anathema, the way they played up the whole ‘professional descendent’ thing? Hmmmm, not a fan. I think I kinda get why they did it, (it makes her fit more neatly into the ‘people breaking out of their prescribed roles’ theme), but they make it into a sort of ‘chosen one’ storyline where she was ‘fated’ to help stop the end of the world, which is fine, I guess? But to me one of the central appeals of the book is a motley crew motivated not by duty or predestination but instead by love of the earth and plain old selfish, stubborn attachment to the lives they had built there going ‘okay realistically there is no way we, of all people, can keep the world from ending, but I guess we’re just gonna try anyway!!!’ Making Anathema some sort of prophesied savior sort of removed her from that narrative, and reduced the strength of that narrative thread overall.

4. Oh and I think I’m in the minority here but I also did not enjoy the kids getting stabby with the horsepeople. There were some great elements to the scene for sure, but that just didn’t feel good to me. The children felt a little more ... protected from enacting that kind of violence in the book, and while there could be legitimate reason for changing it, on a thematic level it also took attention away from the whole ‘power of human belief’ thing, so it felt unnecessary and weaker as well as harsher.

5. I’m not ... actually particularly bothered by any of the changes to Aziraphale? I mean don’t get me wrong I do miss him being a much more overt bastard who is comfortable in his own skin, who collects blasphemous Bibles and is rude to customers and still walks around with his sanctimonious Holier Than Thou convictions because he is THE WORST. But tv Aziraphale is still a proper bastard, even if you’ve got to pay attention a bit more to see it, and I do rather like the way his softness is in itself framed as a rebellion against Heaven. So yeah, I think the changes they made worked and were compelling, and I don’t really have comprehensive complaints about his character. HOWEVER I did not like him indirectly killing the executioner. Having a scene where he indirectly but intentionally causes a death was a good idea in concept, but to my mind it was the wrong circumstances, wrong target, and wrong tone for the scene. Still, it doesn’t bother me that much because it just felt SO off that it feels kinda laughable and my mind just cheerily decided that the filmmakers were misinformed and that did not actually happen.

6. Crowley’s changes I’m having a bit of a harder time reconciling myself to, although I’m having a bit of a hard time pinpointing why? Some of the changes are of the ‘I don’t prefer the change but that’s more personal preference and attachment to my initial vision of the character than critique’ variety, like the ways in which his fear manifests less as anxiety and more as anger in the show. But if I had one central complaint (and this might sound weird at first) I think it would be the way that his world is reduced to Aziraphale. And okay, let me explain—I’m not complaining that their relationship was more emphasized in the show, which I actually loved, and also this is probably a bit hypocritical coming from me when 80% of my posts are about their relationship. The thing is, I find romances more interesting and compelling and moving when both parties have defined personalities and interests and attachments and character arcs outside of one another. And Aziraphale did have that—arguably he has a more defined and complete arc than in the book, in fact. And Crowley definitely has a defined personality. But besides the Bently, what does he love? What are his interests? How does he feel about humanity and the earth? Why does he prefer the earth to hell beyond ‘hell sucks’? How does he feel about his fellow demons? Why does he want to save the earth? Does he care about saving the earth, or is it really only about saving and being with Aziraphale? Idk, I’m exaggerating a bit here, and certain answers to these questions can definitely be inferred. But I miss the Crowley who loves humanity in all its mess, who finds in it an alternative to the restrictive roles demanded by heaven and hell alike, and who has his own arc of going from knowing that he is harming humanity but not doing anything about it, to facing Satan with a tire iron because Aziraphale convinces him to face up to the harm he has caused and do something about it, even if the odds are impossible.

7. I cannot BELIEVE they took out Tim.

8. And I’m running out of steam here so I’m not fully going into it, but it did feel like the show lost a bit of its sense of the earth in all its disastrous glory. I mean, there are plenty of stories that compare Heaven and Hell, but part of what set Good Omens apart for me was the particular way it triangulates Heaven vs Hell vs earth. I haven’t read enough similar fiction to know if it does this in an especially complex or unique way, but what comes of it is this gloriously defiant optimism. The show goes further into Heaven vs Hell (which I enjoyed) but it felt to me as if the earth was a little (although certainly not entirely) lost in the mix.

9. Also definitely not a fan on how hard Crowley pushes for child murder as long as he’s not the one doing it, but so far as I’ve seen the fandom has chosen to collectively forget those lines in favor of ‘you can’t kill kids,’ ‘I’m not personally up for killing kids,’ and THE LULLABY, so I’m the end those lines aren’t anything like the disaster they could have been. Good going, folks.

10. There are of course big-picture things like racism and sexism and homophobia that are. there in varying degrees. Not necessarily more than average, though that’s an even more depressing sentence. But for some of those things I’m not the best person to dissect them, and for the rest I’m tired and I don’t wanna.

11. In conclusion I have a pithy line that encapsulates what I’m having a hard time adjusting to in the show, but I’m pretty sure the first clause would annoy one half of the fandom, and the second clause would annoy the other half, so I’m gonna to cut my losses and shut up now.

#don't rb#if people start reblogging this i will just delete it#also this is very long i don't actually expect people to read this#i'm just exorcising my annoyances all at once#because talking about them day-to-day makes me anxious

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wings / Strengths Weaknesses

To save everyone (and myself) time... [I shortened these from here.] I basically use these as shorthand to type characters from.

Gut Types:

1w9 - Seeking Rightness and Peace

Calm although eruptions of temper are possible. Detached quality. Tendency to formulate and embrace principles that have little human content, but this is also their strength. When awakened, may be objective and balanced, cool and moderate in their evaluations. More unhealthy, might have perfectionistic expectations not humanly possible to meet. May hold social or political opinions that are supremely logical but ultimately heartless and draconian. The rules come first no matter what. Can be merciless or unwittingly cruel. Often a little colorless in their personal appearance. Many Ones with this wing are plain dressers, preferring functional clothing that is appropriate to context but not flashy. The emphasis on function may extend to their general lifestyle. Practicality is highly valued.

1w2 - Seeking Rightness and Love

This wing generally brings more interpersonal warmth. High standards are tempered by humanism. May understand and partly forgive humanity for not doing its best. Work hard to improve the conditions of others, sacrificing time and energy to do good works. When more unhealthy, can be volatile and self-righteous. Authoritarian inflation and moral vanity on the low side. Can give scolding lectures or display a kind of touchy emotionalism. “Do as I say, not as I do” attitudes possible. Hypocrisy likely because the person is so convinced they have moral good intentions. Overlook inconsistencies in their own behavior. Dependency in relationships. Far more likely to be a jealous intimate subtype than Ones with a 9 wing.

8w7 - Seeking Power and Stimulation

Expansive, and powerful. Gregarious and generous, they may display a cheerful bravado. Can be forceful but with a light touch, funny. Often have a sense of humor about themselves. Extroverted, ambitious, materialistic. May talk loud and be sociable partygoers. Driven to bring the new into being. Can be visionary, idealistic, enterprising. Willing to take risks. 7 wing brings an intellectual capacity. Aggression combines with gluttony to form an virulent tendency to addiction. Prone to temperamental ups and downs—can be moody, egocentric, quick to anger. Tendency to court chaos, inflate themselves narcissistically. Some are ruthlessly materialistic. Can use people up, suck them dry. Maybe be explosive or violent, prone to distorted overreaction.

8w9 - Seeking Power and Peace

Aura of preternatural calm, no self doubt. Take their authority for granted. Gentle, kind-hearted, quieter. Often nurturing, protective parents; steady, supportive friends. Informal and unpretentious, patient, laconic, somewhat introverted. A dry or ironic sense of humor. Aura of implicit, simmering anger. Slow to erupt but when they do it’s sudden and explosive. When unhealthy, callous numbness. They can be oblivious to the force of their anger until after they’ve hurt someone. Calmly dominating, colder; may have an indifference to softer emotions. If very unhealthy, they can be mean without remorse or aggressive in the service of stupid ends. Paranoid plotting, muddled thinking, moral laziness. Can be vengeful in ill-conceived ways, abuse those they love, don’t know when to quit.

9w8 - Seeking Peace and Power

Modest, steady, receptive core. Great force of will. Get things done, make good leaders. May have an animal magnetism of which they are only partly aware. Can seem highly centered, take what they do seriously but remain unimpressed with themselves. Strong internal sense of direction. Relatively fearless and highly intuitive. Not intellectual unless they have it in their background. When more unhealthy, they manifest contradictions. Can be passively amiable then horribly blunt. May be slow to anger and then explode. Or angry but don’t know it; may confuse being assertive with being rude. Placidly callous—both styles support numbness. Tactless and indiscriminate and indiscreet. May be unwittingly disloyal, spilling everyone’s secrets. Sexual confusion, sometimes they are driven by lust.

9w1 - Seeking Peace and Rightness

Model children. Virtuous, orderly, and little trouble. Great moral authority plus good-hearted peacemaking tendencies. Often have a sense of mission, public or private. Principled expression of love. Desire to contribute, do little harm. May be well-liked, modest, endearing, gentle yet firm. Great grace and composure, bursts of spontaneity and sweetness. Elegant simplicity. When unhealthy, they self-neglect. Dutiful to what they shouldn’t be. Play the good child, settle for being overlooked. Passive tolerance of absurd or damaging situations. One-sided relationships where the Nine gives too much. Rationalize, minimize, tell themselves they everything’s fine. Placid numbness creeps over them. Intolerance of their own emotions. Gradually deaden their soul.

Heart Types:

2w1 - Seeking Love and Rightness

Conscience and emotional containment. When healthy, they act from general principles about the value of serving others. Ethics come before pride. May hold themselves to high standards. Discreet and respectful of other people’s boundaries. When upset, tend to go quiet and experience strong emotions internally. More melancholy than Twos with a 3 wing. When less healthy and unhealthy, tend to confuse their sense of mission with self-centered needs. Go blind to their own motives; invade and dominate others. Believe their actions are perfectly justified by their ethic of helping. May repress their personal desires and focus on others as a way to avoid guilty dilemma between the rules and their inner needs. If really blind they will warp their ethics crazily to justify personal selfishness and prideful hostility.

2w3 - Seeking Love and Image

This wing brings Twos an extra measure of sociability and the capacity to make things happen. When healthy, can be charming, good-natured and heartfelt. Really get things done, serve effectively on projects that involve the well-being of others. Thrive on group process and are generally good communicators. Enjoy keeping several threads or projects going at once. Unhealthy Twos with a 3 wing can be quite emotionally competitive and controlling. 3 wing brings a double dose of vanity. Strong tendency to live in one’s images. May grow brazenly deluded, preferring their glamorous, self-important scenarios to reality. Tendencies to deceit and emotional calculation. Highly manipulative. This wing is also more extroverted; dramatization of feeling in the form of hysterical snit-fits is far more possible.

3w2 - Seeking Image and Love

Highly gregarious. Tendency towards playing a role. Social perception, prestige and recognition important. Personal warmth, leadership qualities. Sincere desire to do well by others; may be genuinely nice. If they have achieved success, generous in their mentorships. When unhealthy, they are preoccupied with seeming ideal. This can extend to friendships, family, work. Want to seem a perfect spouse, friend, parent, employee, good child. Strong social focus because they need validation from others. Preening and boastful behavior possible. Bursts of egotism. Wanting to be on top, better than others. Slip into impersonation easily, may falsify feeling and not know it themselves. Deep emotional self-recognition is lost. Malicious intentional deceit is possible. Behavior of con-artists and sociopaths.

3w4 - Seeking Image and Identity

Less image-conscious or project an image more implicit and subtle. 4 wing brings a degree of introversion. May measure themselves more by their creations, artistic or social. Compete with themselves more than with other people. Motivation and ability to work on oneself. May accomplish everything they set out to do, then embark on self-analysis. Will still like a challenge, but thoughtful, intuitive or humanistic concerns of prime interest. The low side of this wing can bring a haunted, self-tormented quality or a haughty, competitive pretentiousness. Might be snobs or accuse critics of being too plebian to appreciate them. Cool, hard shell. In private, can lapse into self-questioning and melodrama. Instability and moodiness can be factors. Unrealistic grandiosity.

4w3 - Seeking Identity and Image

Outgoing, sense of humor and style. Prize being creative and effective. Intuitive and ambitious; may have good imaginations, often talented. Colorful, fancy dressers, make a distinct impression. Self-knowledge combines well with social and organizational skills. When unhealthy, have a public/private split. Conceals feelings in public then goes home to loneliness. Can enjoy their work and be dissatisfied in love. Tendency to melodrama and flamboyance; true feelings often hide. Competitive, sneaky, aware of how they look. Some have bad taste. May be fickle in love, drawn to romantic images that they have projected onto others. Could have a dull spouse, then fantasize about glamorous strangers. Achievements can be tainted by jealousy, revenge, or a desire to prove the crowd wrong.

4w5 - Seeking Identity and Knowledge

Withdrawn, complex creativity. Intellectual, exceptional depth of feeling and insight. Very much their own person; original and idiosyncratic. Have a spiritual and aesthetic openness. Will find multiple levels of meaning. May have a strong need and ability to pour themselves into artistic creations. Loners; enigmatic and hard to read. Externally reserved, internally resonant. When they open up it can be sudden and total. When unhealthy or defensive, easily alienated and depressed. Many have a sense of not belonging. Can get lost in their process, drown in their ocean. Whiny, ruminate and relive past experience. Prone to shame. Air of sullen, withdrawn disappointment. May live within a private mythology of pain and loss. Can get deeply morbid and fall in love with death.

Head Types:

5w4 - Seeking Knowledge and Identity

Abstract, intuitive cast of thought, as though thinking in geometric shapes instead of words or realistic images. May be talented artistically and inhabit moods. Combine intellectual and emotional imagination. Enjoy the realm of philosophy and beautiful constructs. The marriage of mental perspective and aesthetics. Fluctuate between impersonal withdrawal and bursts of friendly caring. Can get floaty and abstract. Act like they’re inside a bubble, sometimes with an air of implicit superiority. Cliché of the “absentminded professor” applies especially to Fives with this wing. Environmentally sensitive and subject at times to total overwhelm. Touchy about criticism. Can be slow to recover from traumatic events. Melancholy isolation and bleak existential depression are possible pitfalls.

5w6 - Seeking Knowledge and Security

Detail, technical knowledge, thinks in logical sequence. Intellectual, extremely analytical. Loyal friends, offering strong behind-the-scenes support. Kind, patient teachers, skillful experts. Sense of mission and work hard. Project an aura of sensitive nerdiness, clumsy social skills. When defensive, unnerved by others’ expectations. May like people but avoid them. Sensitive to social indebtedness. Has trouble saying “thank you.” Fear of taking action, develop “information addiction” instead. Asks lots of questions but doesn't get around to deciding. When unhealthy, they suspiciously scrutinize other people’s motives but can blindly follow. Misanthropic and Scrooge-like when defensive. Cuts off their feelings consistently. Cold, skeptical, ironic, and disassociated.

6w5 - Seeking Security and Knowledge

Introverted, intellectual. Many interests, competencies and skills. Original, idiosyncratic point of view. Bookish; interested in history or feel rooted in the past or related to a long tradition. Good at predicting the future. May test friends for a long time but become a friend for life. When unhealthy, project a willed remoteness. Hidden dimensions, intensity and activity. Tension between needing to be seen and withdrawing for protection. Might act arrogant, cryptic or cynical when afraid. Can be diplomatic and say things without saying them. Counterphobics are cool loners or argumentative and violent. Can brood over injustices, entertain conspiracy theories, spend time alone building cases. Paranoid. Sneaky vengeance, passive/aggressive toward others, self-attacking and self-destructive at home.

6w7 - Seeking Security and Stimulation

Outgoing, nervous. Want to be liked, pursues others. Can be charming, sociable, ingratiating. Fast tempo. Personal warmth. Cheerful, forward-looking drive, disarmingly funny. Self-effacing, gracious, curious. When unhealthy, may be self-contradicting and want two things at once. Sometimes test others overtly, drive you crazy with mixed messages. It may be hard to follow what they’re saying. When threatened, impossible to please. When counterphobic, accusative. Some get caught up in big plans they hope will result in material security. Insecure, irritable, petty, irrational, chaotic. Mood swings, inferiority complexes, runaway fears. Hair-trigger paranoid flare-ups . Falsely accuse others and not realize it. Other times plead to be taken care of. Conservative in their lifestyle.

7w6 - Seeking Stimulation and Security

Responsible, faithful, lovable, nervous and funny. Oriented to relationships, want acceptance. Steady, willing to stick with commitments. Openly vulnerable, unguarded, tender sweetness. Has trouble expressing anger. May evade authority but are still aware of it. Canny and practical, they look for deals and loopholes. When unhealthy, may have episodes of sensitivity or insecurity. Get their feelings easily hurt. Sensitive to comparisons. May avoid testing themselves. Grow dependent and addicted to other people, afraid to be alone, suspicious and skittish. Easily feels guilt, may act irresponsibly. Shallow, falls in and out of love easily. Breezily betray others by running away. Can be reckless, unstable, and self-destructive. Hates to be told what to do.

7w8 - Seeking Stimulation and Power

Generous, gregarious, expansive. Loyal to their friends. Leaps aggressively to their defense. Loud or boisterous, urbane and witty. Enjoy social celebrations, storytelling, jokes, food and travel. Self-confidence for worldly matters and getting what they want. Talent for making something out of nothing. Shares what they have, wants others to share their interests. When unhealthy, demanding, selfish, impatient. Self-justifying narcissism. Wants what they want right now. Aggressive, greedy for money, pleasure, recognition. Can demand others say only what they want to hear—sugarcoated truths. Lashes out angrily if reality doesn’t meet their expectations; sometimes vengeful. Moralize to others while being irresponsible. Amnesia for promises. Particular difficulty with sexual fidelity.

- ENFP Mod

630 notes

·

View notes

Text

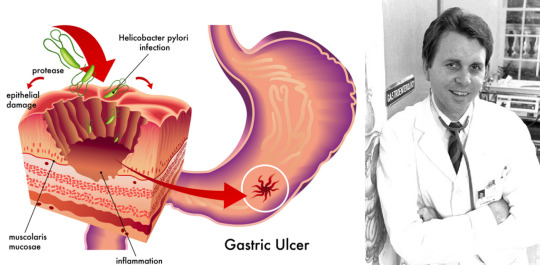

Challenging Science’s Status-Quo: The tale of Barry Marshall

He even downed a liquid shot of bacteria to give himself an ulcer… Just to prove the link.

This is a story of perseverance and the “never give up” attitude of a Western Australian by the name of Barry Marshall, who won a Nobel Prize in 2005 for his work linking stomach ulcers with the bacterium Helicobacter Pylori. He had to drink a shot of the bacteria, and rely on a tabloid to champion his research, to get there.

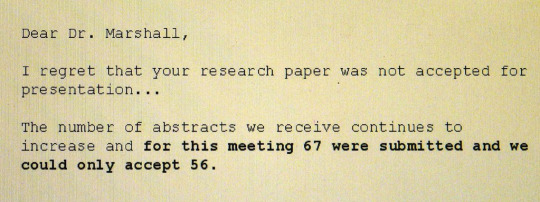

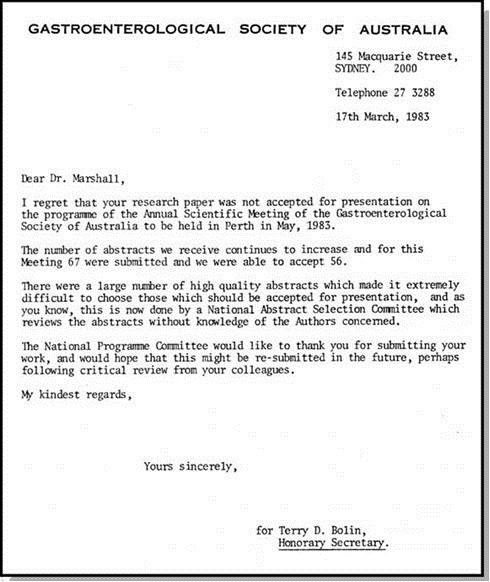

Around 20 years earlier, he was humiliated. His discovery and research linking this spiral-shaped bug with ulcers of the stomach and duodenum received very little attention from the scientific community. He didn’t even make the best 56 of 67 abstracts to be presented at a meeting run by Australia’s Gastroenterological Society:

“To gastroenterologists, the concept of a germ causing ulcers was like saying that the Earth is flat. After that I realized my paper was going to have difficulty being accepted. You think, “It’s science; it’s got to be accepted.” But it’s not an absolute given. The idea was too weird.”

A harsh verdict for Barry Marshall, who ranked in the bottom 20% of submitted abstracts for what he judged to be pioneering work. It wasn’t just his work, of course. The Western Australian was training as a gastroenterology doctor and encountered Dr Robin Warren, a pathologist who was trying to find out the cause of painful stomach ulcers, and had in particularly found a bacteria was present in biopsies of almost every patient who had these: Helicobacter Pylori. Not only stomach ulcers, this same bacteria were also seen on biopsies of stomach cancer patients.

Marshall was very interested in Warren’s findings, and opened the history books to investigate this spiral bug which was first described in 1893, and even suggested to have a link with ulcers back in 1940. Why had the theory linking it with ulcers disappeared in the forties? The answer is that the doctor who suspected this, again based on patients who had the organism, was encouraged to stop his research because it “wasn’t easy to prove” to the scientific community. The consensus was that bacteria couldn’t survive and thrive in the stomach acid, so would there’s no way that it could contribute to ulcer formation. Imagine if this link had been discovered four decades before.

Ulcers were caused by stress — this was the status quo. Other challengers over the decades came and went. One of these, John Lykoudos, was fined by Greek health authorities when he refused to stop giving people with ulcers antibiotics.

But Marshall and Warren did not mind being scientific pariahs. They believed that this perception was wrong. Marshall would not give up on the hypothesis that these bacteria cause gastric ulcers, and increase the risk for stomach cancer.

“If I was right, then treatment for ulcer disease would be revolutionized. It would be simple, cheap and it would be a cure. It seemed to me that for the sake of patients this research had to be fast tracked. The sense of urgency and frustration with the medical community was partly due to my disposition and age. However, the primary reason was a practical one. I was driven to get this theory proven quickly to provide curative treatment for the millions of people suffering with ulcers around the world.”

However, Marshall’s work was met with scepticism wherever he went.

“There was interest and support from a few but most of my work was rejected for publication and even accepted papers were significantly delayed. I was met with constant criticism that my conclusions were premature and not well supported. When the work was presented, my results were disputed and disbelieved, not on the basis of science but because they simply could not be true. It was often said that no one was able to replicate my results. This was untrue but became part of the folklore of the period. I was told that the bacteria were either contaminants or harmless commensals”.

There was, of course, another motivation to the lack of interest with Marshall’s work.

“I tapped all the drug companies to request research funding for a computer. They all wrote back saying how difficult times were and they didn’t have any research money. But they were making a billion dollars a year for the antacid drug Zantac and another billion for Tagamet. You could make a patient feel better by removing the acid. Treated, most patients didn’t die from their ulcer and didn’t need surgery, so it was worth $100 a month per patient, a hell of a lot of money in those days. In America in the 1980s, 2–4% of the population had Tagamet tablets in their pocket. There was no incentive to find a cure… I had this discovery that could undermine a $3 billion industry, not just the drugs but the entire field of endoscopy. Every gastroenterologist was doing 20 or 30 patients a week who might have ulcers, and 25 percent of them would. Because it was a recurring disease that you could never cure, the patients kept coming back”

These portentous pecuniary walls did not faze Marshall. With immense commitment to his cause, he decided to take things a step further. He stuck to his guns and took a shot of H.Pylori himself, stirring the bug which he took from the gut of a sick patient into a broth.

“I swizzled the organisms around in a cloudy broth and drank it the next morning”

He did not know what to expect, and was fine for a few days. But then he started vomiting and his breath became awful, and he started feeling exhausted. His wife found out, which didn’t rule out the stress hypothesis, but these were the first time he had experienced stomach inflammation symptoms in his life. He arranged an endoscopic biopsy on himself to confirm the diagnosis, treated himself with antibiotics and was cured with no lasting effects. He was convinced.

But unfortunately, others weren’t. Marshall’s research was on the verge of obscurity. In 1984, Aussie Tabloid The Star caught wind of this. Previously the domain of alien abduction and celebrity gossip, they printed the headline:

“Guinea-pig doctor discovers new cure for ulcers … and the cause”

Amazingly, this headline from a tabloid newspaper piqued the interest of scientists and funding providers, and gradually incepted the idea that this might be something worth looking into. Patients starting hearing about it, and came to Marshall asking to be given antibiotics. It took a few more years for enough other doctors to try out the “charlatan” treatment suggested in the rag and asked for by their patients, and be shocked and swayed by the results. It’s hard to find another example of tabloid health journalism having such a positive long-term impact.

Over ten years after his paper was first rejected, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a summit and released a statement to say:

The key to treatment of duodenal and gastric ulcer was detection and eradication of Helicobacter pylori.

Eleven years after that, Marshall and Warren were given a Nobel Prize “for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease”. Ulcers were transformed from a chronic and disabling condition to a much more curable one. The standard of care for an ulcer is now treatment with an antibiotic, and stomach cancer is all but eradicated from the Western world.

Marshall’s figurative middle finger to the scientific community underlined the point that people shouldn’t just reject a theory because it contradicts what was previously believed. If medical journals are gatekeepers for the status quo, maybe something needed to change.

Question everything: Science should be a constant process of curiosity and re-evaluation. Marshall had to drink a shot of spiral-shaped bugs and get picked up by a tabloid paper to show that.

#science#health#medicine#nobel#nobel prize#healthcare#ulcers#stomach ulcers#status quo#medical#doctors#doctor#med school#medical school#inspiration#motivation#question everything#questions

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thomas Douglas, The dual-use problem, scientific isolationism and the division of moral labour, 32 Monash Bioeth Rev 86 (2014)

Abstract

The dual-use problem is an ethical quandary sometimes faced by scientists and others in a position to influence the creation or dissemination of scientific knowledge. It arises when (i) an agent is considering whether to pursue some project likely to result in the creation or dissemination of scientific knowledge, (ii) that knowledge could be used in both morally desirable and morally undesirable ways, and (iii) the risk of undesirable use is sufficiently high that it is not clear that the agent may permissibly pursue the project or policy. Agents said to be faced with dual-use problems have frequently responded by appealing to a view that I call scientific isolationism. This is, roughly, the view that scientific decisions may be made without morally appraising the likely uses of the scientific knowledge whose production or dissemination is at stake. I consider whether scientific isolationism can be justified in a form that would indeed provide a way out of dual-use problems. I first argue for a presumption against a strong form of isolationism, and then examine four arguments that might be thought to override this presumption. The most promising of these arguments appeals to the idea of a division of moral labour, but I argue that even this argument can sustain at most a highly attenuated form of scientific isolationism and that this variant of isolationism has little practical import for discussions of the dual-use problem.

The dual-use problem

Some nuclear physicists working in the first half of last century found themselves confronted with an ethical quandary. As they saw it, there were good reasons to seek the knowledge that they sought: not only was there a case for regarding that knowledge as valuable in itself, it was also plausible that the knowledge would have desirable applications, for example, in deterring warfare. However, there were reasons to refrain from seeking this knowledge too, since there was a risk that it would be misused, for example in unjustified nuclear attacks. Some physicists were sufficiently concerned about the risk of misuse that they were uncertain whether they ought to continue with their scientific work. There is, for example, evidence that several participants and potential participants in the Manhattan Project—the United States effort which lead to the development of the atomic bomb—were sufficiently concerned about the risk of misuse that they were ambivalent about whether they ought to be participating in the project.1

These physicists took themselves to be confronted with a quandary that has recently become known as the dual-use problem.2 We can understand this as the quandary arising whenever

An agent faces a choice whether to pursue P, where P is a policy or project such that pursuing P is likely to result in (i) the creation of new scientific knowledge, or (ii) the wider dissemination of existing scientific knowledge, and

The knowledge whose creation or dissemination is at stake could be used in both morally desirable and morally undesirable ways, and

The risk that this knowledge will be misused (that is, used in morally undesirable ways) is sufficiently serious that it is unclear whether the agent is morally permitted to pursue P.3

Note that although this formulation of the dual-use problem, like many other formulations in the literature, explicitly refers only to two conflicting values—morally desirable uses of knowledge, and morally undesirable uses—other considerations could potentially contribute to the problem. Whether the risk of misuse is sufficiently high that it is unclear whether the agent should pursue P may depend not only on how the risk of misuse compares to the prospect of morally desirable uses, but also, for example, on whether the knowledge will be valuable in itself, on whether the agent has made commitments to or not to pursue P, and various other factors.4

Some further brief clarifications may be helpful. First, the dual-use problem can, on the above formulation, arise both in relation to the creation of new scientific knowledge and the dissemination of existing scientific knowledge. Second, although this problem is often exemplified by reference to decisions faced by individual scientists, on the above formulation it can also arise for other individual agents (for example, science policymakers and journal editors) and, and, assuming collective agency is possible, for collectives (perhaps including the scientific community, national governments and society-at-large). Note also that the choice faced by the agent could be a choice about a particular project (for example, a particular scientific study) or about a general policy (for example, a choice about whether to require censorship of scientific journals or ‘classification’ of certain scientific information). The dual-use problem can thus arise at multiple levels.

It can also arise in otherwise very different areas of intellectual inquiry. The classic examples of the dual-use problem come from early and mid-twentieth century nuclear physics. However, recent ethical discussion of the dilemma has focused on the life sciences. It has been suggested that some research in molecular biology poses dual-use problems because the knowledge it produces could be used to create human pathogens or other biological agents whose intentional or negligent release into the environment would have devastating consequences. Discussion of this concern was triggered in part by developments in genome synthesis which have been taken to hold out the prospect of creating ‘designer’ pathogens or recreating historical pathogens, such as the smallpox virus or the 1918 Spanish Influenza virus, to which most people are no longer likely to be immune.5 Discussion has been stimulated further by two studies which resulted in the creation of variants of the H5N1 influenza virus that were transmissible by air between ferrets (and thus, perhaps, between humans).6

Neuroscience is another scientific area in which dual-use problems have been thought to arise (Dando 2005, 2011; Marks 2010). For example, rapid development recently in neuroimaging—particularly in functional magnetic resonance imaging—has provided new research tools for neuroscientists, and new diagnostic and prognostic tools for clinicians. But it is possible that new imaging technologies will also have applications in lie-detection. There are thus concerns that they might be used to violate privacy, perhaps as an aid to unethical interrogation practices (Wolpe et al. 2010). Neuroscientists are also beginning to understand the neural bases of various human behaviours. For example, there has been a flurry or work recently on the role of the hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin in facilitating trust and other so-called ‘pro-social’ behaviours (e.g., Kosfeld et al. 2005; Baumgartner et al. 2008; De Dreu et al. 2011), and it has been suggested that this work could be misused, for example, by those who wish to covertly manipulate the behaviour of others (Dando 2011).

Scientific isolationism

An agent who takes herself to be faced with a dual-use problem, or who is reasonably thought to by others to face one, plausibly bears a deliberative burden. She may not simply ignore the putative problem; she must address it in some way.

There are two obvious ways in which she might discharge this burden. First, she might attempt to resolve the problem by conducting what I will call a use assessment. This would involve determining the likely uses of the knowledge at stake and then determining, partly on the basis of this assessment, whether she is morally permitted to proceed. Second, she might attempt to escape the problem. That is, she may attempt to change her circumstances such that the problem no longer arises. For example, it may sometimes be possible to escape a dual-use problem by developing some new means for preventing the misuse of the knowledge whose creation or dissemination is at stake without thereby foregoing desirable uses of the knowledge. Concerns about the misuse of scientific knowledge may then no longer provide any reason to refrain from pursuing P.

Historically, however, many agents who have been confronted with dual-use problems have neither sought to resolve them, nor to escape them, nor indeed to discharge the putative deliberative obligation in any other way. Instead, they have sought to deny that any such obligation exists, maintaining that they may continue to promote scientific knowledge without resolving or escaping the problem. Often this claim is made rather obliquely. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the Manhattan project who himself expressed ambivalence about his work said, in attempting to justify it, “[i]t is my judgment in these things that when you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success”.7 This is ostensibly a purely descriptive claim. But given that it was intended partly to diffuse moral criticism, it is clearly meant to imply that scientists should or at least may permissibly ‘go ahead’ and argue about it later.

In other cases agents confronted with dual-use problems have come closer to flatly denying that they are under any obligation to assess the likely uses of the scientific knowledge whose creation or dissemination is at stake. Some, for instance, have sought to draw a clear distinction between science and technology, or between research and development, maintaining that questions about morally desirable and undesirable applications become relevant only in the realm of development or technology. For example, in response to the publication of a story about cruise missile technology in the science section of Time, the Nobel Laureate Roger Guillemin stated that “[w]hat is going on there [cruise missile development] is not science but technology and engineering…. The use, including misuse or ill use, of… knowledge is the realm of politicians, engineers and technologists”.8 Guillemin can plausibly be interpreted as claiming here that only in the realm of technology need one appraise the uses of scientific knowledge. The implication is that in science, use assessments can be eschewed; choices about which scientific project(s) if any to pursue or promote may be made purely on the basis of scientific considerations, for example, whether a given piece of knowledge is intrinsically or theoretically interesting.9 I will refer to this view as scientific isolationism,since it holds that decisions about the direction of science can be made in isolation from certain moral, nonscientific considerations.

If scientific isolationism is correct, then an agent reasonably supposed to be faced with a dual-use problem can simply deny that she needs to address that putative problem, since she is permitted to ignore the likely applications of a piece of knowledge in deciding whether to contribute to its production or dissemination. She is thus permitted to ignore the very factor—risk of morally undesirable uses—that is thought to generate the problem. The thought would presumably be either that how scientific knowledge will be used has no bearing on the moral permissibility of the agent’s actions, so that there is no real problem at all, or that it is has a bearing, but one that the agent is morally permitted to ignore in her deliberations.

Scientific isolationism has implications that extend beyond debates regarding the dual-use problem and the misuse of science. Indeed, the view has perhaps most frequently been invoked not in defence of science that may be used in morally undesirable ways, but in defence of science deemed to have no plausible morally desirable uses. Marie Curie famously reminded an audience at Vassar College that

We must not forget that when radium was discovered no one knew that it would prove useful in hospitals. The work was one of pure science. And this is a proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of the direct usefulness of it. It must be done for itself, for the beauty of science, and then there is always the chance that a scientific discovery may become like the radium a benefit for humanity.10

Curie is here invoking a variant of scientific isolationism to defend the pursuit of basic science that will not clearly yield any social benefit.

In what follows, however, I will focus on the implications of scientific isolationism for scientific work that is amenable to misuse. I will consider whether it is possible to defend a form of scientific isolationism that does indeed allow agents putatively faced with dual-use problems to eschew any appraisal of the likely uses of the scientific knowledge at stake.

Clarifications

Before proceeding to the argument proper, however, it will be necessary to offer some further preliminary remarks on scientific isolationism.

First, scientific isolationism should be distinguished from a different view with which it is frequently coupled. This is view that the state, and others outside the scientific community, ought to leave those within it a wide domain of freedom in selecting their scientific aims, and their means to achieving them (see, e.g., Bush 1945, pp. 234–235). Let us call this view scientific libertarianism.11 Scientific isolationism and scientific libertarianism are frequently defended together. For example, in his classic discussion, Bush (1945) moves directly from the claim that “[w]e must remove the rigid controls which we have had to impose [during World War Two], and recover freedom of inquiry”, an expression of scientific libertarianism, to the claim that “[s]cientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity for exploration of the unknown”, arguably an expression of scientific isolationism (1945: 235). Indeed, the two views can plausibly be regarded as two aspects of the same, broader model of the relationship between science and society—a model that is often associated with the Enlightenment.12 According to this model, science should be autonomous from the rest of society. One statement of the view has it that “the only scientific citizens are scientists themselves” and that “for science to engage in the production of properly scientific knowledge it must live in a ‘free state’ and in a domain apart from the rest of society” (Elam and Bertilson 2002, p. 133). We could perhaps aptly characterise this model as the conjunction of scientific libertarianism—which asserts that science should be granted political autonomy from the rest of society—and scientific isolationism—which grants it a kind of moral autonomy.

Nevertheless, scientific libertarianism and scientific isolationism are distinct views, and they have different implications for dual-use problems. Scientific libertarianism might be drawn upon to resolve certain dual-use problems. Consider a case where a government is deciding whether to institute state censorship of scientific publications in a sensitive area, such as synthetic biology, and is reasonably deemed to be faced with a dual-use problem. Perhaps the government can resolve this putative problem by appealing to scientific libertarianism. If that view is correct, then clearly state censorship would be unjustified. However, though scientific libertarianism may allow agents to resolve dual-use problems in some circumstances, it will not enable the resolution of all such problems. Suppose that an individual scientist is considering whether to disseminate some item of scientific knowledge, free from any legal impediment to doing so, and takes herself to be faced with a dual-use problem. Here, scientific libertarianism will provide no guidance, for there is no question of constraining scientific freedom in this case; the issue what the scientist should do given the freedom she has been granted.

So scientific libertarianism does not allow us to resolve all dual-use problems. Scientific isolationism does, however, potentially provide a way out of all dual-use problems, for it denies that the consideration that generates such problems—the risk that scientific knowledge will be misused—needs to be considered.

But is scientific isolationism itself justified? In what follows I subject the view to critical scrutiny. I take as my initial target the following, rather strong variant of scientific isolationism:

Full Isolationism. For any policy or project P, moral agents considering whether to pursue P are not morally required to assess the likely uses of the scientific knowledge at stake (that is, the knowledge whose creation or dissemination is likely to be affected by the agent’s choice whether to pursue P).

This variant of isolationism is strong in two respects. First, it deems that agents may always permissibly ignore the use of the knowledge they produce. Second, Full Isolationism applies to all agents, regardless of their institutional role. For example, it applies to scientists, university administrators, government executives, and members of the general public. It also applies to both individual and collective agents, assuming that there are collective agents. Thus, it may apply to science funders, universities and governments.

It might seem uncharitable to take, as my target, such a strong version of scientific isolationism. However, I begin with this strong variant not because I wish to exclude weaker, and perhaps more plausible, variants; indeed I will turn to consider weaker variants of scientific isolationism in Sects. 6, 7 and 8. Rather, I begin with this strong variant because this will enable me to approach the assessment of scientific isolationism in a systematic way. My assessment proceeds in three steps. First, I set up a presumption against Full Isolationism. Second, I consider two arguments that might be thought to override this presumption and thus justify Full Isolationism. I argue that both fail. Finally, I consider whether it might be possible to defend a weaker version of scientific isolationism that can nevertheless do the work that has been asked of stronger versions. The aim of the subsequent discussion is thus not only (and indeed is not primarily) to assess Full Isolationism, but also to determine whether it is possible to defend any version of scientific isolationism that will allow those faced with putative dual-use problems to deny an obligation to resolve or escape those problems. I believe that this aim is one that is worth pursuing even if Full Isolationism is implausible. It would, after all, be quite consistent to hold that Full Isolationism is implausible while also suspecting that it might contain a kernel of truth, and perhaps a kernel that will be helpful to those faced with dual-use problems.

The presumption against Full Isolationism

The argument for a presumption against Full Isolationism begins from a parallel between science and other domains. Outside of the realm of science, we generally think that, when an agent is deciding whether to facilitate the production or dissemination of a tool that is amenable to both morally desirable and undesirable uses, that agent should take into account its likely uses.

Consider the case of arms manufacturers. Most would judge that, in deciding whether to produce certain kinds of weapons, or to sell them to certain kinds of customer, arms manufacturers should consider the risk of misuse. Similarly, most would judge that in deciding whether to permit or support the production and sales of such arms, governments should take the possible misuse of those weapons into account.

It might be thought that weapons are a special case because they are so clearly amenable to misuse. But note that we would probably take a similar view about items whose potential for misuse is less obvious. For example, we would think that risk of misuse ought to be taken into account by those who manufacture and sell components that could be used to produce weapons, but which are primarily used for morally desirable or neutral purposes. And we would think that governments should consider risk of misuse in deciding how to regulate the production and sale of such components.

Similarly, consider those who manufacture and sell chemicals with legitimate uses (such as household cleaning agents) but which can also be used to manufacture unsafe and illicit drugs. Again, most would think that, in considering whether to manufacture such chemicals, and whether to sell them to certain kinds of customer, the manufacturers ought to consider the risk of misuse. Similarly, we would think that the government should take the risk of misuse into account in deciding whether and how to regulate the production and sale of such chemicals.

More generally, when tools are amenable to both morally desirable and undesirable uses, we generally judge that their likely uses should, at least in some cases, be taken into account when decisions that affect the creation or dissemination of those tools are made. We think that some rudimentary form of use assessment should be conducted. This, I suggest, creates a presumption in favour of the parallel view regarding scientific knowledge which is, after all, also a tool amenable to both morally desirable and undesirable uses.

It is true that those who produce tools amenable to both good and bad uses sometimes seek to deny any obligation to perform a use assessment. For example, arms manufacturers may claim that they need not consider the possible uses (including misuse) of the arms they produce and sell because they are not directly responsible for the misuse of those arms. Nor do they intend the arms to be misused.13 Such appeals are, however, widely regarded as unpersuasive. The facts that arms manufacturers do not intend misuse, and are not directly responsible for it, may somewhat weaken their obligation to conduct use assessments. But most of us nevertheless think that, at least in some cases, such an obligation is present.

The noninstrumental value of knowledge

I have been arguing for a presumption against Full Isolationism. In this section and the next I consider two arguments for Full Isolationism that might be thought to override this presumption.

The first of these arguments appeals to the view that scientific knowledge has noninstrumental value—value that does not derive from its tendency to produce other things of value. This view has frequently been invoked by those who wish to defend their participation in the production or dissemination of knowledge that is prone to misuse (Glover 1999, p. 102), and one can see how it might function in a defence of Full Isolationism. The thought could be that pursuing a project or policy P that is likely to result in the creation or dissemination of scientific knowledge is morally permissible just in case the scientific knowledge at stake has (a sufficient degree of) noninstrumental value, so there is no need for those deciding whether to promote the creation or dissemination of knowledge to consider what instrumental value or disvalue it might have in virtue of the ways in which it will be used. Consideration of instrumental value would be superfluous. Indeed, it might be worse than superfluous; it might potentially distract those considering whether to pursue P from the more important matter of determining the likely noninstrumental value of the scientific knowledge at stake.

This argument depends on two claims. First, that knowledge is (or at least can be) noninstrumentally valuable. And second, that the noninstrumental value of a piece of knowledge is the sole determinant of whether it would be justified to pursue a project or policy likely to result in the creation or dissemination of scientific knowledge. But note that the second of these claims does not follow from the first. One could hold that knowledge is noninstrumentally valuable, but that its instrumental value is also relevant to decisions regarding whether to pursue P. Indeed, if knowledge has both instrumental and noninstrumental value, the natural position to hold would be that both types of value bear on such decisions. The view that instrumental value is irrelevant would be plausible only if the noninstrumental value of knowledge were a trump value, one that always over-rides the sorts of value or disvalue attached to good or bad applications of that knowledge—or at least a value that will have overriding force in all but extra-ordinary circumstances. But it is not clear why is should be so. Indeed, accepting that the noninstrumental value of knowledge is a trump value would have implausible implications. It would arguably imply, for example, that compared to the status quo, vastly greater resources should be expended on supporting science, and vastly fewer on other projects. Healthcare, education, social security, defence and so on should be supported only insofar as they are conducive to scientific progress.

Uncertainty

A second argument for Full Isolationism would appeal to the uncertainty that will afflict any attempt to conduct what I earlier called ‘use assessments’—that is, attempts to determine the likely applications of the scientific knowledge whose creation or dissemination is likely to be affected by the decision whether to pursue P, and a determination, partly on the basis of this assessment, of whether it is morally permissible to pursue P. This uncertainty could stem from at least two sources. First, there is the problem that it will often be unclear in advance what knowledge will be created or disseminated through pursuit of P.14 Thus, suppose that an individual scientist is considering whether to pursue some project investigating x. It will presumably be somewhat predictable that this project could yield knowledge concerning x. But the content of that knowledge will generally not be clear in advance. If it were, there would be no need to pursue the knowledge. Similarly, it may be quite likely that the project will in fact yield knowledge about some other topic, y. Thus, when a scientist is faced with a question about whether to seek to produce knowledge of a certain kind, there will typically be uncertainty about what knowledge will actually be produced. (The same kind of uncertainty will not exist, or not to the same degree, in relation to the dissemination of existing knowledge.) Second, there will typically be uncertainty about how a given item of knowledge will be used. The possible applications of a given item of knowledge will often be unclear, and highly dependent on unpredictable contextual factors (such as which people acquire the knowledge).15

We can distinguish two different ways in which these concerns about uncertainty might figure in an argument for Full Isolationism. First, they might be invoked in support of the claim that attempting to determine the uses of scientific knowledge is always futile.16 It never has any predictive value regarding how the knowledge that would in fact be created or disseminated due to pursuit of P would in fact be used. Second, they might be invoked in support of the claim that the costs of attempting to engage in such use assessments outweigh the benefits.

The first of these arguments seems difficult to sustain. Suppose scientists are considering whether to disseminate some piece of knowledge from, say, nuclear physics or synthetic biology. Suppose further that there is a clear mechanism via which the scientific knowledge might be used to produce weapons as well as clear evidence that some individuals or groups are interested in producing and using such weapons for the purposes of terrorism. We would, I think, be inclined to judge that the scientific knowledge in question is, ceteris paribus, more likely to be used for terrorist purposes than knowledge in relation to which we know of no similar mechanisms and motivations. It would be implausible to suggest that information about these mechanisms and motivations has no predictive value.17

At this point, a defender of Full Isolationism might retreat to the second of the two arguments mentioned above. She might concede that concerns regarding uncertainty do not render use assessments entirely futile, but claim that they do substantially diminish the payoffs from attempting to make such assessments, and substantially enough that the costs of making the assessments outweigh the benefits. This supporter of Full Isolationism might note that attempts to conduct use assessments are likely to come at considerable cost; to make these assessments well, it is likely that significant time, effort, expertise and financial resources would be required—all resources that could otherwise be devoted to other worthwhile activities. And if those use assessments would in any case be plagued by substantial uncertainty, the costs of conducting them might outweigh the benefits.

Concerns about the costliness of use assessments are likely to be particularly serious in the case of individual scientists. If individual scientists were to conduct use assessments in relation to each experiment they undertook or paper that they published, this would be highly burdensome and would significantly reduce the time available for doing scientific work. Note, however, that this concern could be significantly mitigated by outsourcing much of the necessary work to external agencies. One can imagine a situation in which scientists could consult an agency whose sole role was to provide specialist advice on how various types of scientific knowledge are likely to be used, as well, perhaps, as evaluations of how these different uses bear, morally, on the scientist. Individual scientists would then be left only with the tasks of predicting what knowledge their work might produce and deciding whether to rely on the assessments of the specialist agency. This agency could also provide assessments to policymakers, journal editors and other individual and collective agents in a position to influence the creation and dissemination of scientific knowledge.18

Note also that rejecting Full Isolationism does not commit one to the view that use assessments must be formed on the basis of explicit calculation and reasoning. Rejecting Full Isolationism entails accepting that use assessments should sometimes be made, but this is consistent with believing that those assessments could be made on the basis of simple heuristics (e.g. ‘research with obvious applications in warfare is, other things being equal, more likely to be used for military purposes than other research’) or even intuition, and if decisions were made in these ways it is not clear that they would be associated with substantial costs.

I have been presenting some grounds for doubting that (1) making use assessments in relation to scientific knowledge is futile, and (2) the costs of making such estimates are outweighed by the benefits. There is, moreover, some reason to suppose that these doubts are decisive. This can be seen by returning to the analogy between scientific knowledge and other tools amenable to both morally desirable and undesirable uses. The arguments concerning uncertainty that I offered above would, it seems to me, apply with equal force to certain other instances in which one agent contributes to the production or dissemination of a tool amenable to both good and bad uses. Suppose the government is considering whether to allow arms manufacturers within its jurisdiction to sell weapons to rebels in a country currently in the midst of a civil war. The complexities that typify such conflicts will likely introduce a high degree of uncertainty regarding how any weapons sold might be used, particularly if, as it seems we should, we take long term uses into account. Nevertheless, few would argue that, in such a situation, the government could plausibly ignore the likely uses of the arms whose sale is in question. We would not think, in such a situation, that uncertainty is sufficiently great so as to make use assessments futile, and moreover we would likely assume there to be ways of making such assessments such that their benefits will outweigh their costs. It is not obvious that the degree of uncertainty involved in use assessments in relation to scientific knowledge are substantially greater than those involved in this case—particularly if we limit ourselves to the applied sciences, where uncertainty regarding potential applications is arguably lessened. Thus, our intuition that uncertainty does not provide a decisive ground for eschewing use assessments in the arms sale case plausibly provides some evidence for the view that it does not constitute a decisive ground in the scientific knowledge case either.19

Weakening scientific isolationism

I have argued that there should be a presumption against Full Isolationism, and I have been unable to identify any argument capable of overriding that presumption. But I now want to consider whether it might be possible to salvage some kernel of truth from scientific isolationism. Consider the following, weaker variant of the principle:

Restricted Isolationism. For any policy or project P, individual researchers and research groups considering whether to pursue P are not morally required to morally appraise the likely uses of the scientific knowledge at stake.

This principle differs from Full Isolationism in that it applies only to individual researchers and individual research groups. It does not apply, for example, to the scientific community as a whole, to governments, or to humanity as a whole. One might think that Oppenheimer, Guillemin, Curie, and other scientists who have asserted similar views, had no stronger variant of scientific isolationism in mind than Restricted Isolationism, for they do not explicitly include governments or other institutions within the scope of their comments. Moreover, restricting the scope of scientific isolationism in this way arguably renders it more plausible. It allows us to avail ourselves of at least two arguments that were not previously available.

Lack of influence

The first of these arguments maintains that individual scientists and research institutions need not engage in use assessments because any action based on such assessments would be futile: individual scientists and research institutions cannot significantly alter the rate of knowledge production or dissemination. If one scientist or institution decides to abstain from producing or disseminating some piece of scientific knowledge because of the risk of misuse, this same knowledge will shortly be produced or disseminated by someone else.20