#podocarp

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

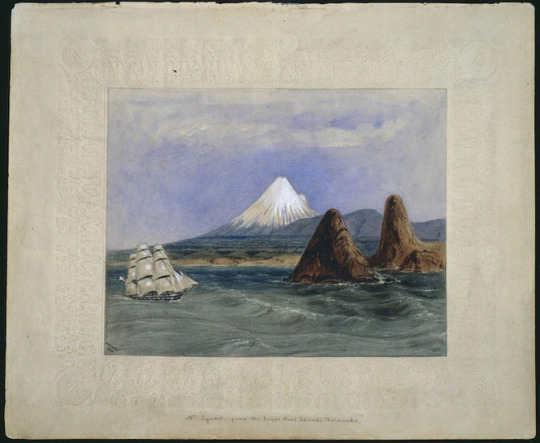

The Great ACT-NSW-NZ Trip, 2023-2024 - Taranaki Maunga

A 2,518 metres (8,261 ft) tall stratovolcano, ideally positioned to catch every change in the weather coming off the Tasman. As a result it gets up to 11 meters of rain a year, and the winds between the peak and the remains of its predecessor can exceed 130kph.

Naturally, of great importance to the local iwi, and it certainly made an impression of the Europeans too - although a lot of early paintings exaggerate the height.

watercolour by Charles Heaphy, some time between 1839 and 1849.

They named it Mt Egmont, although happily the original name is back to being the official one.

The volcano erupts, on average, every 90 years, with major eruptions every 500. Of considerably more concern are the repeated catastrophic cone collapses that turn most of the volcano into gigantic landslides sweeping fridge-sized boulders and smaller debris dozens of kilometers away from the volcano, and well past the current coastline.

Anyway, while we wait for it to go bang again, visitors can enjoy the fascinating change in vegetation as you go up the mountain. As you get higher and higher, the coastal vegetation is replaced by the goblin forests, contorted mossy woods dominated by Kamahi (Weinmannia racemosa), that developed after eruptions destroyed the preexisting podocarp and Nothofagus forest, and as you go higher the trees are replaced by tussock grasses and later alpine plants.

There are still kiwi in the national park, which is one reason dogs are strictly banned. The introduced stoats continue to be a problem - we saw one on one of the tracks.

There was also this building, a corrugated iron structure noteworthy for being the oldest such building left anywhere in the world. It was originally a fort, and still has gun slits. The windows are new.

Most of the species I saw around the visitors center are were new to me - I could have spent a week just phtographing the incredible lichens in the goblin forest. Here's some that weren't new.

And a few lichens I don't have an ID on.

#taranaki#new zealand volcano#mount taranaki#taranaki maunga#orocrambus#new zealand moth#crambidae#miro#podocarp#new zealand plant#Pectinopitys#podocarpaceae#asteraceae#Olearia#kamahi#Weinmannia#Cunoniaceae#Charles Heaphy#asplenium#new zealand fern#aspleniaceae#spleenwort#goblin forest

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiwi (Apteryx) - a genus of flightless birds endemic to New Zealand. They're the smallest of the ratites, a group that includes ostriches, emus, cassowaries, the extinct moas and elephant birds - kiwi's closest relatives, with both lineages diverging 54 million years ago. There are five species of kiwi found in habitats ranging from subalpine scrub to podocarp forests throughout New Zealand. While none overlap today, they were widespread before the introduction of mammals such as stoats, the kiwi's main predator, and several species coexisted.

Despite differences in size, colour and habitat, all kiwi species share traits such as sexual dimorphism; females are larger than males, reliance on hearing and smell rather than sight, an omnivorous diet, and a nocturnal lifestyle; possibly a result of mammalian predators.

Kiwis were thought to be closely related to the extinct moa due to shared traits. However, DNA studies show they're closer to Madagascar's elephant birds, rather than to the moa, with which they shared New Zealand. The kiwi's massive eggs were once thought to be a shared trait with its relatives, the elephant birds; which laid the largest eggs ever recorded. However, it's now thought to be an adaptation for precocity, allowing the chicks to hatch mobile with yolk to sustain them. Fossils of the extinct genus of kiwi - Proapteryx, suggest that their ancestors were capable of flight and lost this ability after reaching New Zealand. This also suggests that kiwis arrived in New Zealand independently and much later than the Moas, which were already there.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Lying on a tree fern stalk is a small Procolophon. Below it is fallen debris consisting of primitive conifer leaves (podocarp) along with Ginkgo leaves and fruit. Procolophon reached lengths of approximately 30 cms (1 ft)."

From Dinosaurs: A Global View (1990) by Sylvia J. Czerkas & Stephen A. Czerkas. Illustrated by Douglas Henderson, Mark Hallett, John Sibbick.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tree Tops Mashup

Something I drew years ago, inspired by listening to the music in the Tree Tops level in Spyro 1. I had used what were then new coloring pencils and a new mixed media pad though I wish I had run through with the pencils for a second time to fill in the white spaces.

This here is a depiction of the tree villages of the enigmatic Night Dragons, who make their homes amidst the towering Beech and Podocarp conifer trees inland from Wijenborg Bay on West Antarctica. The local dragons practice their magic and ancient ways of life largely in isolation from the outside world, under the protection of the mighty Laio-Ulchan Empire, where their villages are hard for most incapable of flight to reach. On some of the great branches and trunks of the trees, the dragons have built great temples and palaces, primarily from wood, and their villages prosper even in the cold dark of the winters. Local legends tell that the great trees were tampered with by the dragons, to escape the attacks by marauding saurian tribes innumerable millennia ago and they now stand as the tallest beings on earth, dwarfing the mighty redwoods and cedars of the American Pacific coast.

#my art#art#dragon#dragons#dragon art#fantasy#giant trees#tree village#fantasy art#traditional drawing#traditional art#pencil drawing#colored pencil

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A writer’s guide to forests: From the poles to tropics, part 2

Dearest writers, and all who find this guide, big shout out to you. Now let’s get back into things and move ever closer to the equator.

Temperate rainforest

While most people think of rainforests as being a purely tropical environment, several exist in more seasonal areas of the planet.

Location- Coastal regions. The North American temperate rainforest is a thin belt stretching from California, through British Columbia and up into southern Alaska. In the southern hemisphere, the largest forest is found along the southern stretches of the Andes.

Climate- Temperate to subpolar. Conditions are wet, with moisture coming in the form of rain and sea mist. Seasons are variable, with summers being warm and winters cold and snowy.

Plant life- Conifers dominate these forests, with deciduous trees restricted to lower altitudes. In the north, the primary species are Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, red cedar, western hemlock, and giant redwoods. Southern forests are dominated by Podocarps, Monkey puzzle, and southern beech. High humidity means that moss, lichens and ferns grow amongst tree trunks and the forest floor.

Animal life- Whilst more densely populated than the boreal forests, the amount of wildlife is limited by resinous conifer needles, and the lack of plants on the forest floor in denser areas. Most species are arboreal, with weasels, squirrels, and various birds along up the majority of life. Moist conditions mean that there are many types of amphibians and invertebrates that live on the forest floor. Southern hemisphere forests have become host to many invasive species, such as deer, beavers, rats, and ferrets.

How the forest affects the story- The most obvious challenge for characters will be the changing of the seasons. What do your characters do as the days grow shorter and colder? And let’s not forget that rain and mist are common. Damp conditions are a breeding ground for mold and rot, so people will have to come up with ways of keeping them and their possessions dry.Then comes the vegetation. What kind of culture would develop among the tallest trees in the world? Do they live on the forest floor or up in the trees? The density of the canopy can make farming impractical, unless done in clearings or tree top platforms. If your characters and their society are arboreal, then how do they travel between trees? Bridges? Zip-lines? Or do they take inspiration from nature and glide between trees? Imagine if people on the ground meet those from up above. How would these two cultures be different? Would interactions be peaceful, antagonistic, or do they have no contact (at least until the plot requires it)? Being close to the coast, does the sea have an influence on characters and their culture? How would you explain this to someone not familiar with this environment? And you are not limited to the Earth. Remember, the California forests were the stand-in for the forest moon of Endor from Star Wars.

#writing#creative writing#writing guide#writing inspiration#writing prompts#writer on tumblr#writeblr

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝚍𝚎𝚟𝚕𝚘𝚐_𝟶𝟸.𝟷

Moa's Ark & Zealandia

https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/moas-ark-1990/series

Moa's Ark (1990s TV series) opening animation. It was during the 90's that scientists formulated the "Zealandia" protocontinent theory and complexity of how species migrated over time, putting the last nail in the coffin of the idea that everyone got a free ride over on a piece of Australia. Going through Aotearoa's natural history doco archives has been a lot of fun.

Hello again! I took a bit of a break in posting long- form updates, but I think there's enough on my mind for a second batch of posts this week. After that there will again just be small updates on the Instagram until May - when I may have some sort of concept media for the sim to show off. For now I'll aim for a focused peek into a couple of aspects of it as usual.

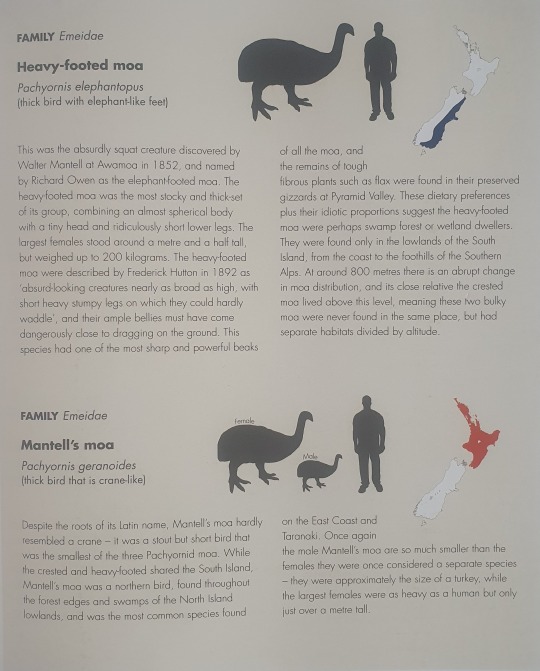

This post is going to be all about the Moa, the species that got me hooked on this project. It's also going to be about species variation, and the tension between scientific accuracy and visual accessibility.

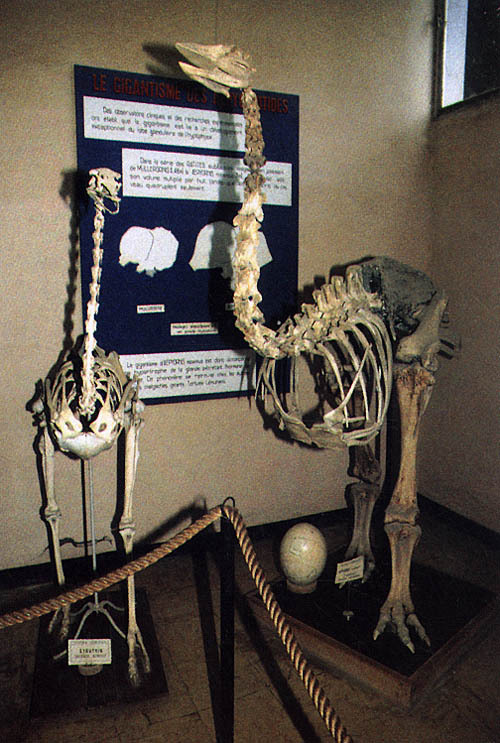

Moa skeletal reconstitutions at Te Papa Tongarewa, Museum of New Zealand.

A couple of interesting facts about the moa;

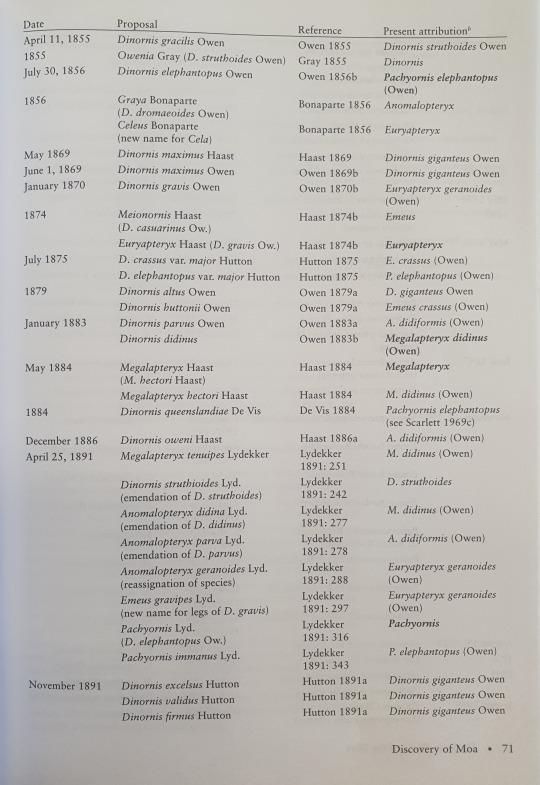

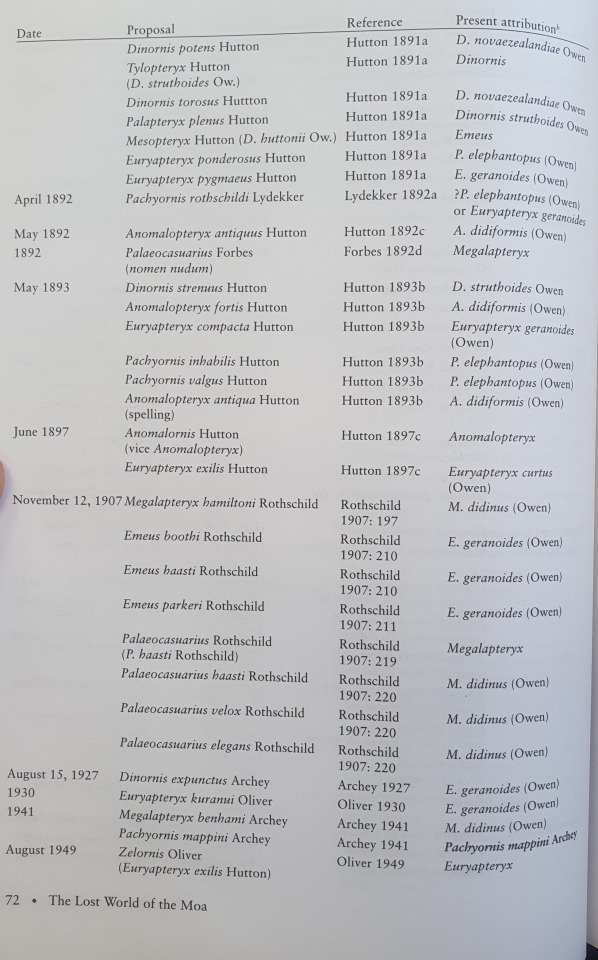

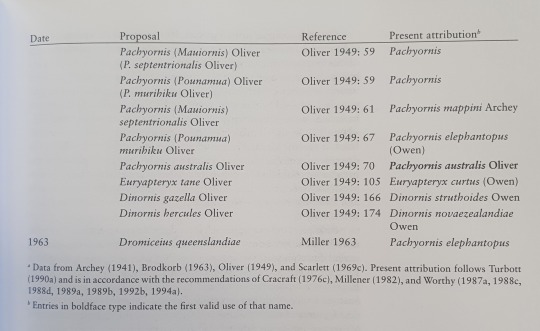

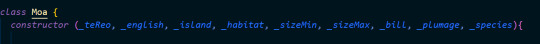

-We currently classify them as nine species. Here is a full catalog of every time someone thought they'd found a new one:

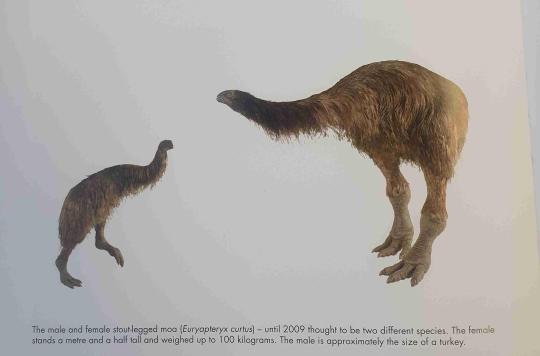

-Within many species, female moa can be more than twice the size of males (yes, this is one reason so many moa "species" were identified)

-Moa are unique in that they had no wings (not even the kiwi's tiny t-rex stubs) and, thank goodness because so many NZ species can be traced back to evolving from Australian fauna, their closest past relatives are South American tinamous rather than the emu.

-They also got a bad wrap for their past perception as tall, emu- like, big dumb grass grazers. Actually, while they're nowhere near as smart as multi-sense-foraging kiwi, they could identify and feast on a whole variety of twigs, herbs, leaves and berries - most of which were found in the more common forest than grassland.

This is why they have a bulky build and head-forward posture (until kinda recently, museum curators tended to give them that tall, emu/giraffe like posture, even adding extra vertebrae for show.)

Whanganui Regional Museum (This isn't close to the worst examples)

So; how do I even begin to approach the scope, as well as potential uncertainty, of data we have on the Moa?

Here's one way: Oversimplification!

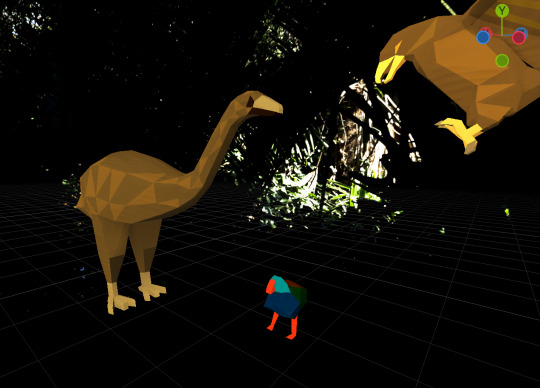

Screenshots from Godot editor & runtime previews for compatibility (web) mode and forward+ (basically more shaders) renderer. The camera is RTS- style; getting the runtime shots was a bit finnicky.

I've started to build low-poly models in Blender for the fauna, which in the future I'd love to rig for animation and get super technical with appearance variation. For now I'll focus on the system for placing them in the right biome and basic pathing behaviour, and the Moa will be a North Island giant moa based vaguely off this model for an AR national park exhibit: https://moaparkotorohanga.wordpress.com/2014/07/08/a-collection-of-moa-feedback-from-trevor-worthy-and-lizzy-perrett/

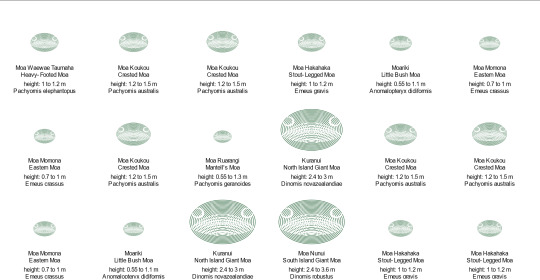

While I'm not working directly on the simulator for the next while, I am building this 2D tool to represent the moa's species variation; it is *incredibly* helpful to have just set up a system where I can add and edit instances of a broader Moa "class", and I'm looking forward to giving each species its visual character (the main creative liberty I'll be taking is colour coding from grey to brown to communicate which of New Zealand's islands each species populated, as well as their preferred biome (there's 3 main ones: subalpine mountain, wet podocarp forest, dry forest/ lowland)

Moa "collection" project at time of writing.

If this exercise has highlighted anything though, it's just how difficult it is to reduce life's complexities to a single shape that represents a single numeric value. Those who read my last posts may remember that any given moa species' size may have varied over time and with temperature, (generally bigger during ice ages and smaller out of them) along altitude, (generally bigger and bulkier higher up) and just within species based on how they adapted to any given place. Not to mention the relatively massive lady moa.

And since we're only working with what's left of them all - the only intact gizzard samples proving that whole diet theory, and most of the remains we have to work with, are those found in Pyramid Valley in Canterbury (a swamp with surrounding mosaic of vegetation and forest) - who knows how to truly depict what life was like tens of thousands of years ago.

From the Moa book by Quinn Berentson

A very cursed JavaScript "spreadsheet".

So, very long-winded post. I hope you found something interesting within! Something that made you think about nature's craziness maybe. I meant to get across just how much there is to scientific communication, and I barely touched on how I aim to keep the overall narrative in focus (or basically be aware of it.)

I can't wait to work on this more collaboratively, with folks who really know their stuff about ecology and the cultural aspects of Aotearoa - I think the potential for collaboration and education is what's keeping me going with this project.

Until next time ! - here's some of my highlights from a trip to the Zealandia ecosanctuary.

Kia hora te marino

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana

Hei huarahi mā tātou i te rangi nei

Aroha atu, aroha mai

Tātou i a tātou katoa

Hui e! Tāiki e!

May peace be widespread

May the sea be like greenstone

A pathway for us all this day

Let us show respect for each other

For one another

Bind us all together!

#devlog#gamedev#indiedev#programming#birblr#moss#plants#aotearoa#oceania#natural history#nature#godot engine#javascript#ecology#science

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Green (and white) Antarctica

The allochiropterid Chimil kaslem, from the Oligocene of Antarctica. Here depicted with speculative structural colours like those of mandrill faces, exhibitting for a potential mate. By hodarinundu

Through most of the Phanerozoic (that’s fancy for all the time span between the Cambrian and today) the South Pole has been much warmer than it is today (barring a short lived glaciation at the Devonian/Permian boundary) Even as recently as 5 million years ago our timeline’s Antarctica bore southern beech and conifer forests. The complete freezing was a very young and aberrant process, even if mild glaciations previously existed.

The nature of Antarctica’s white death is generally attributed to the complete isolation of the continent, the formation of the Drake Passage allowing cold waters to cycle viciously and sucking out all warmth and preventing warmer waters from arriving southwards. However, recent studies show that the main culprit was a decline in CO2 levels, and that full blown glaciation only happened when things were cold enough, a while after the Drake Passage formed as the first paragraph study shows.

In this timeline, the Azolla Event did not happen, and so atmospheric CO2 levels remained higher. Antarctica’s freezing was thus delayed, but the climatic drops at the Grand Coupure still left an impact.

In our world, the Eocene La Meseta formation bears the bulk of Antarctic Cenozoic fossils. Here, the suceeding Bay Formation picks up where it left off, bearing an unique mammalian fauna absence in our timeline. The formation seems to represent a southern forest ecosystem, but one drier than the La Meseta Formation. Conifers are the dominant trees, but southern beeches and ferns are present to lesser degrees. Temperatures were similar to those of modern Patagonia, though perhaps warmer and wetter near the coast.

Here, the dominant terrestrial mammals are notoptilodontoideans and leonardids, generalist groups, mirroring the dominance of small to mid-sized marsupials in our timeline’s Eocene (this timeline’s Eocene Antarctica was much warmer and tropical, btw). Several clades have continuity from the Eocene, but there is a drastic diversity drop by 45%, suggesting that the colder and drier environments were progressively less rich in biodiversity. Notoptilodontoideans seem to have dominated carnivorous and durophagous niches, while leonardids were mostly omnivorous generalists or insectivores. Examples of the former include Rageowrapper badenala, an ocelote sized predator with long, fang-like secondary plagiaulacoids, and Laga robana, a wolverine sized robust species with smaller fang plagiaulacoids but massive and brick-like normal ones; examples of the latter include O’tr ul, a mole-like necrolestid, and C’al anika, a deer-sized sengi-like omnivore.

Flying mammals are represented primarily by pteroectypodids, whose “feathered” wings gave them an advantage over other flying mammals in colder climates, and by allochiropterids, which evolved in Antarctica and thus maintained a higher species diversity here. It is here where we find the largest Oligocene members of either group, some reaching wingspans of two meters. A similar dichotomy occurs between them and their flightless cousins, which pteroectypodids being more raptorial, granivorous, molluscivorous or weird wood-chewing forms analogous to woodpeckers, while allochiropterids remain mostly either insectivores or generalists, with a few remaining frugivores feeding on podocarp fruits. Neither group appears to have been migratory, suggesting either year round foraging or hibernation, though there is currently no evidence of the latter. Aside from frugivorous allochiropterids, flying mammal diversity seems to increase by 30%, likely due to less competition from flightless species and because flight allows for covering larger distances in search of food.

Besides those, some fragmentary remains of gigantic acamapichtliids (+6 meter wingspans) and of insulonycteriids (+5 meter wingspans) are also present, suggesting that these giantic flyers were summertime visitors or even permanent residents, though only at large sizes and low diversities to cope with the colder, less biodiverse environment.

The most strongly affected groups were mesungulatids and gondwanatheres, more specialised and more vulnerable to the collapse of Eocene forests into these new colder ones. Ferugliotheriidae is only represented by one taxon, K’terrernen ultima, a hare sized generalistic herbivore in a place where tougher vegetation like grass has started to dominate. One sudamericid, Moinee antarcticus, was a sheep sized grazer, while two greniodontid genera, Yarramundi and Guwayana, appear to have been mixed grazer browsers, the former represented by five hare to sheep sized species and the latter by one boar-sized one, G. koolmatrie. The largest herbivore of the assemblage is Austrocamellus nungeena, an herbivorous mesungulatid weighting a mere 500 kg, a positive dwarf compared to its brethren further north. The apex predator was also a mesungulatid, Tarrabah semifrons, about as large as a striped hyena.

No herpetofauna aside from some tuatara-like sphenodontians, one small meiolaniid and rhinodermatid and leiopelmatid frogs survived, all represented by fragmentary remains. Some ratite like palaeognaths and giant flying pelagornithids are present, but the reccord for terrestrial birds is even scarcer.

By contrast, the surrounding oceans appear to have thrived with life. Both penguins, choristoderes and marine mammals – all groups, with monotremes and marine necrolestids in particular being quite diverse due to these being their ancestral homewaters – appear in great abundance in the coastoal deposits, the colder waters being more nutrient rich than tropical ones. Rockeries of millions of flightless seabirds and mammals littered the beaches, breeding even during winter months. The largest mammal of the Oligocene Antarctic is Soorts giganteus, a taeniolabidid as large as a Steller’s Sea Cow that foraged in the rich kelp forests, which compose its many known coprolites.

In this timeline, Antarctica thus remained hospitable for longer. True, the colder climate did make things harder for its terrestrial inhabittants, but while the old order of gondwanatheres, mesungulatids, ratites and herpetofauna (choristoderes aside at least) is on its way out, the generalists and sea dwellers keep going. And given that the Miocene will see a rise in temperatures, who knows what weird directions the southernmost continent will take, now that its future is not bleak?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

More at Wisley - Waterfall Hill Garden

Dry sunny rock garden. This made me think I should redo the slope to the side yard at home with a waterfall. The sound of water is good.

Can not find in US...but love the gray spineyness of this.

Erodium is a type of geranium. These are alkaline-loving and long summer bloom time. Typically they like alpine conditions so that is why I love them, I cannot grow them here.

Incised Fumewort or Corydalis decipiens is "a spring-blooming, tuberous perennial with attractive purple flowers and ferny foliage, typically found in woodland settings" and is available in the US and it is adaptable. Below left is Galanthus which I forgot, is Snowdrops. I don't have any of these and I won't start now because they are so aggressive.

Above right, available at Brent and Becky's bulbs and one I will get: Often misnamed ‘Autumn Crocus’, cup-shaped flowers on naked stems; poisonous and tastes bad to critters that may be tempted to eat them; flowers appear in the fall and foliage, which resembles hosta leaves, appear in the spring; prefers rich, well drained soil and partial shade to full sun; many are species and are variable in their color and growth habit. Bloom mid-late fall; can bloom without being planted in soil; 3 per sq. ft; WHZ 4–8; 13/+ cm unless otherwise noted. Colchicum are long term perennial bulbs that get better each year.

Persicaria (below) is a weed here so I'd hesitate to plant this but it is super interesting leaf color and shape. It is for shade.

Andromeda polifolia is Blue Ice Bog Rosemary and I LOVE IT. "A very small shrub for detail use in gardens, icy blue needle-like foliage and pink urn-shaped flowers in spring; very fastidious as to growing conditions, needs ample consistent moisture and highly organic soils, will not tolerate alkaline soil." The bloom photo is from the internet search. Available by mail order and I think I'll try it if it can handle the heat in MD. More good GRAY foliage that I need! Really expensive and fussy.

This leaf color is so cool for a peony. It is a Majorcan Peony, for rock gardens in Mediterranean climate. I'll keep an eye out for it but not easily found in the US.

This was fun to explore and I needed more time...maybe another visit.

This little grouping was so gorgeous. The white flowers of mossy rockfoil saxifage are sweet. It is an alpine rock garden plant that would not like it here. I think I have tried it unsuccessfully in the past.

Above top middle of photo, the weird needle/leaves caught my eye. It is ridiculous here since it is supposed to be a giant conifer eventually. From Wikipedia:

"Phyllocladus alpinus, the mountain toatoa or mountain celery pine, is a species of conifer in the family Podocarpaceae. It is found only in New Zealand. The form of this plant ranges from a shrub to a small tree of up to seven metres in height. This species is found in both the North and South Islands. An example occurrence of P. alpinus is within the understory of beech/podocarp forests in the north part of South Island, New Zealand."

I like artemesia- Dusty Miller - but it never lasts long in the garden.

I wonder if this is true of silver gray foliage in general? I'll try it again. Santolina died out in the sideyard garage garden. It looked really good there so I need to try for that gray again.

This is Common Everlasting, I think. It is a pacific native and the best texture for summer gardens? Lathyrus vernus has a tag but the plant is not present. "Lathyrus vernus is a non-climbing perennial sweet pea. It is a multi-stemmed, clump-forming plant with a bushy habit which typically grows to 12" high. Typical pea-like flowers (3/4") are borne in axillary racemes (5-8 flowers each) in April. Flowers are reddish purple with red veins, becoming more violet-blue as they mature. Pinnate, light green leaves (each divided into 2-3 pairs of 3" long, ovate leaflets) lack tendrils." Worth trying.

Below is another good gray groundcover that will not like the humidity here. Basket of gold is common but nice.

This yellow-green (below) is so good to cut the blue greens. Common name is box-leaved Honeysuckle or Privet and both names are scary.

MOBOT: 'Twiggy' is a compact yellow-leaved sport of 'Baggesen's Gold'. It typically matures over time to only 2-3' tall. This shrub features drooping, twiggy branches clad with tiny, golden yellow, evergreen leaves. White flowers in spring. Purple black berries in fall. Yellow leaves take on bronze tones in winter in areas where plants are evergreen (USDA Zones 8 and 9), but will drop to the ground where deciduous (Zones 6 and 7).

Snow in Summer, ubiquitous ground cover in midwest suburban gardens, Greg makes it look good.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Text

#2405 - Pectinopitys ferruginea - Miro

AKA Prumnopitys ferruginea, and originally Podocarpus ferrugineus. 'ferruginea' derives from the rusty colour of dried herbarium specimens. Miro comes from the Proto-Polynesian word milo - the Pacific rosewood (Thespesia populnea) found on tropical islands far to the north.

A podocarp endemic to New Zealand, growing in lowland terrain and on hill slopes throughout the two main islands and on Stewart Island.

It can live to about 600 years in age, and 25m in height, with a trunk up to 1.3 m diameter. Like other podocarps, the fruit is fleshy and berrylike, and spread by birds such as the New Zealand Pigeon.

Lake Mangamahoe, Taranaki Ringplain, New Zealand

#Pectinopitys#Prumnopitys#miro#podocarp#new zealand tree#podocarpaceae#lake mangamahoe#taranaki ringplain

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Photo

We all know what conifers are, don’t we? They’re evergreens with needles rather than leaves. But what about larches? They’re not evergreen. And cypresses have scale-like leaves, not needles. And let’s not even talk about monkey puzzle trees! The answer to the question “what are conifers” isn’t so clear. These plants are actually defined by their method of reproduction, not their foliage. Many species are indeed evergreens with needle-like foliage, but not all. What they all have in common is that they produce reproductive cones instead of flowers. I live in one of the most conifer-dense regions in the world, and I’ve developed a deep fascination for these plants. Not only do many of them look lush and green even during the winter, but they need hardly any maintenance at all in the garden. I’m just dying to discuss even more about conifers, so without further ado, here’s what we’ll be going over: What Are Conifers? There is one characteristic that defines these plants and it’s not the presence of needles or whether or not they are evergreen. All of them bear cones with seeds inside. In fact, that’s what the word conifer means. It’s Latin for conus, meaning cone, and ferre, meaning bearing. It’s a cone-bearing plant. They all have two types of cones: females and males. The male cones are small, soft, and contain pollen. The female cones are larger, woody, and contain the seeds. In many species, the pollen is carried a short distance by the wind. Male and female cones on a mugo pine. Conifers are gymnosperms, meaning they are woody, seed-bearing plants. All of the about 650 existing species within seven genera are woody perennials that are either trees or shrubs. The vast majority have a single main trunk. They can be low-growing and under nine inches tall, like dwarf Japanese juniper (Juniperus procumbens), and over 300 feet tall in the case of coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens). Most prefer full sun and somewhat dry soil, and all are wind-pollinated. The leaves are typically needle-like or scale-like, with the needles in either linear or acicular shapes. Most are evergreen, but others are deciduous. When we say “evergreen” it doesn’t mean they hold their needles indefinitely, they just don’t shed them all at once like deciduous types do. Instead, they drop a few here and there that are constantly being replaced, giving the appearance of having persistent needles that last forever. Many conifers produce sap, also called resin or pitch, which is a natural protection against pathogens and pests. Many pests are put off by the fragrance of the resin, but they can also become trapped in it if they try to feed on the plant. If one of these plants is wounded, it sends resin to the area to flood out pests and pathogens that might cause infestation or infection. Some conifers want to attract birds to their cones to help spread the seeds. These will typically grow upright cones with short or non-existent stems. That allows the birds to easily perch on the branch and feed. Some Examples The pine (Pinaceae), podocarp (Podocarpaceae), and cypress (Cupressaceae) families make up the largest conifer families, but there are also the Araucariaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, and Taxaceae families. All the needle-laden trees like cedars, Douglas firs, true cypress, firs, junipers, kauri (Agathis), larches, pines, hemlocks, redwoods, spruces, and yews are conifers. There are deciduous types, including some larches, bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), and dawn redwoods (Metasequoia spp.). These will lose their foliage in the fall and develop new leaves in the spring. When it comes to conifers in the garden, pines, cypress, yews, and junipers are the most popular in North America. Where Do They Grow Wild? After the last ice age, many conifer species became extinct because flowering plants, which are better adapted to the warmer conditions of the modern climate, took over. But there are still a few areas where flowering plants haven’t managed to outcompete with conifers. The Pacific Northwest is one area where conifers thrive and that’s because evergreen leaves need a climate with a long, mild growing season. They also do well in areas that have little moisture in the summer and ample moisture the rest of the year. They’ve also adapted to grow in poor soil where flowering trees and shrubs fail to thrive. You mostly find conifers in colder regions in northern latitudes. The two cold-hardiest trees in the world, the Dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii) and the Siberian larch (L. sibirica) are conifers. The rarest type in the world, the Monterey cypress, comes from a tiny corner of southwest Oregon and northwest California. There are just a handful native to the Southern Hemisphere. These belong to the Araucaria, Podocarpus, and Agathis genera. Form and Reproduction Most conifers, at least in their natural form, have a conical shape with a strong central leader. This shape maximizes the light exposure available to the branches and needles. As mentioned, what sets conifers apart from flowering plants is how they reproduce. These plants have petalless flowers on inflorescences that make up the immature cones. All conifers have male cones that contain the pollen and female cones that hold the flowers and seeds. The male cones are typically soft, with scales that hold the pollen inside until it’s ready to release. Once it releases, it’s carried on the wind, water, or by animals and there can be an impressive amount. If you’ve ever stepped outside to find everything covered in yellow powder, you’re probably looking at pollen from a nearby conifer, like a pine tree (Pinus spp.). The pollen finds a female cone, which is usually soft when young, becoming woody when mature and pollinated. The scales open to allow the pollen to find the seeds inside, and they’ll often exude a bit of resin that helps the pollen stick. Then, the scales close back up to protect the pollinated seed. Some seeds are winged so they can be carried on the wind and others wait for birds or other hungry animals to eat them and carry them far and wide. If you go for a walk in a coniferous forest in the spring, you’ll likely notice the seedlings popping up all over the place. Most cones are pollinated and drop from the tree in the same year, but quite a few take two or even three years to release the seeds. You might hear some cones referred to as “fruits,” such as those on junipers and yews, but they aren’t technically fruits. They’re cones, they just have fleshy scales. Quick Guide to Identification It can be hard to tell all the various conifers apart. Although it’s a lot more complicated than this, you can generally determine which type it is based on how the needles attach to the stalk. If the needles wrap around the twig, it’s likely either a yew (Taxaceae family) or a cypress (Cupressaceae family). Needles with a round base that leave behind round scars when they fall or are torn off are true firs (Abies spp.). Soft needles in clusters of 15 or more that attach together at the base via a spur are larches (Larix spp.), while 15 or more stiff needles on a spur are true cedars (Cedrus spp.). Needles in groups of two, three, or five with a papery envelope at the base, it’ll be a pine (Pinaceae family). Scales attached to the stem are junipers (Juniperus spp.). If the needles attach via a small peg perpendicular to the stem, you’re probably looking at a spruce (Picea spp.). If there’s a tiny perpendicular stem, it’s likely a Douglas fir. Finally, if the needle has a bit of stem that grows parallel to the main stem, it’s a hemlock (subfamily Abietoideae). You can learn more in our guide to conifer identification here. Conifers Are So Cool! I really think these plants are so cool – they have some really fascinating adaptations. Wait, now as I’m reading that sentence, I’m realizing that I am officially a plant nerd. I can’t be the only certified conifer nerd. What do you like about these plants? Which are your favorites? Let us know in the comments section below! And if you love conifers as much as I do, you’ll likely want to learn more about them. Add these guides to your reading list next: © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. !function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', ' fbq('init', '176410929431717'); fbq('track', 'PageView'); Source link

0 notes

Text

the idea being "what if Starflight from Wings of Fire if he was a total beefcake inspired by fanart of R63 Cynder?" and, well, the result speaks for itself.

This fellow here is a Night Dragon, mysterious inhabitants of the towering beech and Podocarp forests of western Antarctica, renown for the wooden cities they have built upon the trunks and branches of the gigantic trees and for their prowess in magic. He is a scholar, trained in the arcane and in combat with spear, bow, and axe; a horrific accident resulted in his blinding but he has persevered and continues his work even with his inability to see. Originally, I thought of him being just athletic but I did end up drawing him pretty buff though I did run into trouble drawing his shoulders and arms right, until I looked at someone's artwork of a wolf with a sword to get it right. Said wolf was the right physique, strong but with no bulging abs or biceps, which is what this dragon ended up being.

The real obstacle was the coloring; previously, whenever I tried to color something that's supposed to be dark grey or black, it just ends up being a mass where you can barely see the details. So my solution was to apply the dark grey lightly while adding silver and light grey to the detailing and then layering purple on top of the darker greys. It definitely worked for the most part and I'm happy that I can see the detailing lines on this guy.

#art#bellumsaur#dragon#anthro dragon#scaly oc#scaly#scaly art#scalie#anthro#furry#furry art#anthropomorphic#male#man#muscle#athletic#muscular#spear#blind#traditional drawing#traditional art#colored pencil#pencil drawing#pencil art

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo