#serbian architecture

Text

Art nouveau synagogue in Subotica, Serbia, built in 1902, project by Marcell Komor and Dezső Jakab.

#synagogue#subotica#serbia#serbian architecture#art nouveau#architecture#1900s architecture#early 20th century#marcell komor#dezsö jakab#paleta post

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

◾The interior of the Visoki Dechani Monastery (Serbian: Манастир Високи Дечани, romanized: Manastir Visoki Dečani) is a medieval Serbian Orthodox Christian monastery located in Metohia region, Southern Serbia. It was founded in the first half of the 14th century by Stefan Dechanski(srb. Стефан Дечански/lat. Stefan Dečanski), King of Serbia.

◾Dechani Monastery is one of four World Heritage medieval monuments in Kosovo and Metohia(Southern Serbia) designated as a heritage site in danger. Since the arrival of KFOR peacekeepers in the region in 1999, attacks on the Monastery have increased. Since 1999 there have been five significant attacks and near miss attacks on the monastery, by Albanians:

1️⃣27 February 2000 – Six grenades hit the Dechani Monastery.

2️⃣22 June 2000 – Nine grenades hit the Dechani Monastery.

3️⃣17 March 2004 – Seven grenades fell around the monastery walls.

4️⃣30 March 2007 – One grenade hit the wall behind the church.

5️⃣1 February 2016 – Four armed suspects in a motor vehicle were detained at the gates of the monastery. A search of their car found an assault rifle, pistol, ammunition and extremist Islamist printed material.

◾Dushan Kozarev, member of government of Serbia had claimed a year earlier that the monastery gates were painted with graffiti that read "ISIS", "Caliphate is coming" and "UCK"(The terrorist organization that was responsible for the ethnic cleansing of Serbs in Kosovo and Metohia. Members of the UČK are many prominent Albanian figures. including Hashim Thaci).

Dečani Monastery is currently under 24/7 guard from KFOR. Of the four medieval monuments in K&M that are designated as a heritage site in danger, Dechani is the only one under direct guard from KFOR. In 2021, Europa Nostra has listed Visoki Dechani as one of the seven most endangered cultural heritage sites in Europe. Despite all of the above, the Albanians claim that the Monastery is theirs and that they built it, although they tried to destroy it on several occasions and caused great damage to this Serbian cultural monument from the 14th century.

#Manastir#Dečani#Dečan#nemanjići#Nemanyitsh dynasty#Serbian#serbian#balkan#europe#serbian traditional clothes#serbian folklor#Serbian tradition#serbian architecture#Serbian aesthetics#Serbian Orthodox#Orthodoxy#Srbija

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

^Home built in the traditional Serbian style

Kadina Luka, Serbia

rayeshistory.com

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belgrade architecture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remarkable oxymoron, deserving the total best, by the Serbian Jupiter Ovprsten, for her second YWAMag selection.

Ruine

Špicer Castle, Beočin, Serbia. © Jupiter Ovprsten :

#jupiter ovprsten#art#femininity#emotions#trees#nature#composition#street photography#serbian photographers#visual art#visual poetry#yes we are magazine#photographers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#talents on tumblr#original content#original photography#architecture#decay#oxymorons

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Church of St John the Baptist, Samodreža

#Church of St John the Baptist#Samodreža#church of st lazar#Vushtrri#kosovo#church#serbian orthodox#wikipedia#wikipedia pictures#architecture#europe#southeast europe

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And only you can still build the pyramids, the cupolas of Kremlin, the stolen obelisk, Moorish palaces, cathedrals of Köln and Burgos, the giddy villas in Barcelona, cedar pagodas, pile dwellings, Guggenheim Museum, the Parliament in the mist, Babylon, Ravenna, Alexandria, Rome!

Raša Livada, The Horse Has Six Legs: An Anthology of Serbian Poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belgrade Serbia - Music, Galleries, History

Triangle of Serbian National Institutions Nikola Pašić Sq.– Elorna

It will be fantastic returning to Belgrade! Mediterranean resort towns like Datça are healthy and relaxing, but after a rejuvenating stay, I’m happy to be back in a city. The trip from Tukey to Serbia will be tiring – Datça – Marmaris – Istanbul – Belgrade – but I’m not complaining. The worst part is packing heavy winter clothes…

View On WordPress

#Belgrade 2024 Parliamentary Election#Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra#Belgrade Serbia#Belgrade Splavs#Block 13 New Belgrade#Branko’s Bridge#Cold War Spy Cellars Belgrade#Council of Europe (CoE)#Datça Turkey#Eugster Museum Belgrade#Galerija ŠTAB#Kosovo#Museum of Contempory Art New Belgrade#New Belgrade Philharmonic Concert Hall#Nikola Pašić Square#Saint Sava Cathedral#Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade#Sava River#Savski Venac Municipality Belgrade#Serbia Against Violence (SPN) Coalition#Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts#Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic#Serbian Progressive Party (SNS)#Stari Grad Municipality Belgrade#Subterranean Walking Tours Belgrade#Ulična Galerija#Ušće Park New Belgrade#Yugoslavia Brutalist Architecture#Zeleni Venac Market Belgrade

0 notes

Text

i've been working as a research assistant on a project looking at media depicting "warchitecture" in the yugoslav wars, chechnya and ukraine, and interpreting that as both historico-cultural semantics and as actual media. the project was inspired by and basically predicated on, the work of architectural philosopher/urban theorist andrew herscher, so i have a lot of the ideas from his work fresh in my mind. so with the ceasefire ending and israel's genocide continuing, i feel like it would be constructive to just share a bit from his book violence taking place: the architecture of the kosovo conflict.

herscher was working on his phd in the late-90s when the international criminal tribunal for the former yugoslavia (ICTY) asked him to join the prosecution and be an expert witness on the destruction of buildings during serbia's ethnic cleansing of kosovo 1998/99. and when working in the balkans collecting evidence and writing reports for the ICTY, he realised that relegating the destruction of architecture to an externality of violence was absent of the fact that the destruction and construction of architecture is a productive medium for expresing historico-cultural and political semantics -- invoking ideas of present and historical material conditions and realities, and enforcing them. in the case of kosovo, this was serbs ensuring the alterity of kosovar-albanians, projecting serbian orthodoxy over kosovar-albanian islam, destroying their communities to ensure they could not retain their autonomy, etc. one of the most common instances hersher encountered were the minarets of mosques being toppled, but the building left otherwise mostly intact. this is violence as performance, and as a means of engaging in a cultural discourse to marginalize and eliminate a community. it's a kind of violence which architecture reciprocates and reproduces meaning in.

attached a bunch of excerpts below. consider gaza and the experience of palestinians, and remember that the yugoslav wars ended with 161 political and military leaders being brought before a judge at the hague.

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the left bank of the Sava River and opposite the old town lies Novi Beograd, New Belgrade, the Serbian capital’s fastest growing municipality. It is a planned city and today’s inhabitants and businesses benefit from its rather modern infrastructure, a distinctive advantage over the old town. Novi Beograd’s construction began in 1948 but especially during 1960s and 1970s the municipality grew and numerous housing blocks and public buildings were erected. Because of these Novi Beograd in recent years has become something of a brutalist icon that is roaming social media platforms but is simultaneously subject to great change due to permanent new construction.

But while most photographers focus on the undeniable appeal of the architecture, Norwegian Marius Svaleng Andresen takes a closer look at the intersection of architecture and everyday life and the architecture in relation to the individual. In his book „Life in the New“, published last years by Kerber Verlag, Andresen explores the actual life going on inside, outside and in between the architecture: in view of the little stories of life the monumental architecture recedes into the background and becomes the stage of day-to-day life. People peeking out from behind the curtain, old men playing cards, a woman cleaning her windows and children running around, all of them populate Andresen’s photographs and bring up the question of what it is actually like to live in Novi Beograd. Apparently the photographer, who is also a journalist, asked himself this question too and met with 12 individuals who tell their own story of living in New Belgrade: there is Mirjana, the widow of a former military airport commander, who has been living in Novi Beograd for more than 50 years and at first didn’t really like it. And there is also Filip, the dog loving graphic designer and rapper, who philosophizes about the stepped volumes of the blocks and how they symbolize his daily struggle to reach the top.

In tandem with his sensible photographs Andersen provides an unusual, more humane portrait of Novi Beograd that is both visually stunning and emotionally touching. A warmly recommended read!

#marius svaleng andresen#architecture#serbia#novi beograd#belgrade#architectural photography#photo book#kerber verlag#book

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

We actually need to talk about how the world genuinely hates balkan people. I made a comment saying how I wished people were more interested in balkan culture and non balkan people got mad over my comment 💀

These people fr can't handle when balkan people are happy and not the laughing stock. Some of them fr said that the balkan contributed nothing to the world....like did these mfs forgot Nikola tesla? Mother Theresa? Alexander the great? Albert Einsteins wife was serbian! AND GREECE ALONE LIKE THERE ARE SO MANY FAMOUS HISTORICAL FIGURES FROM GREECE HOW CAN THESE MFS SAY THAT BALKAN CONTRIBUTED NOTHING TO THE WORLD

Toliko sam ljuta ali zaista sam ljuta. Zašto ovim ljudima smeta ako ja želim da balkan ima više reprezentacije i da nas ljudi više ne mrze.......

tbh people view balkans as a backwater land filled with idiots and silly people who cant think for themselves; term "balkanization" is enough of a proof. its always used with such disgust too. what are we, a bunch of hillbilly balkaners who cant self-govern? (this was hitlers opinion too btw)

greece aside, just yugoslav countries have so much to offer you historically: faust vrančić (first parachute), slavoljub penkala (first pen), croatia had the first hydroelectrane in europe, ruđer boškovićs physics theories.

i always remember that tweet where this guy was like "if someone uses cyrillics, theyre a russian bot" and when someone said "ah yes russia the only nation in the world" the guy replied "people in croatia bosnia and serbia are poor and dont have phones or the internet".

balkans have been so shit on through the history, despite many acchievments of people from here, in culture, architecture, science etc, but there is always this disgust and hatred when people talk about balkans, like we are garbage deponium of history.

uglavnom slažem se, puno pozdrava, biće bolje jednog dana ❤️

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

◾Pirot Fortress or Momchilov grad, Southeastern Serbia 🇷🇸

#Pirot#Fortress#Serbian#Medieval Serbia#europe#serbian#balkan#Serbian architecture#Middle ages#Medieval#Serbian history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOVI SAD, Serbia (JTA) — In the heart of downtown in Serbia’s second-largest city, nestled between brick buildings on a leafy street, sits a large synagogue.

With its 130-foot-high central dome and faded yellow brick facade, along with its Jewish school and offices on either side, the synagogue’s three-building complex has become a must-see tourist attraction, with multilingual panels in its courtyard explaining the area’s Jewish history.

The synagogue was built to accommodate up to 950 worshippers in the first decade of the 20th century. But like the city and Serbia more broadly, the building has clearly seen better days. On two recent days, a family was camped outside the entrance, begging passersby for money.

Before World War II, Novi Sad had roughly 60,000 inhabitants, 4,300 of whom were Jews — about 7% of the total population. Most were affluent merchants, lawyers, doctors and professors. Their wealth was reflected in the city’s opulent synagogue, constructed between 1906 and 1909 by Hungarian Jewish architect Lipot Baumhorn, whose work incorporated elements of the Art Nouveau movement.

Today, however, the prominent building serves a dwindling community that, like others decimated by the Holocaust and further eroded by the Balkan wars of the 1990s, fears for its future as residents disperse abroad. Only about 640 Jews remain in Novi Sad; others have sought a future in Israel or countries that offer more economic opportunity.

“We use our own shul only for Yom Kippur,” said Novi Sad native Ladislav Trajer, the deputy president of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Serbia.

“We get six to 10 people for Shabbat — maybe 15 — but fewer than half are male so we can’t make a minyan,” said Trajer, referencing a Jewish prayer quorum of 10 men. He spent eight years in Israel and also served in the Israel Defense Forces. “Even in Belgrade, which is much larger, the rabbi doesn’t always get a minyan. And nobody here keeps kosher. You can’t get kosher meat.”

Novi Sad was a thriving center of Jewish life in prewar Yugoslavia and the city — now a metropolis of 370,000 sometimes called the “Serbian Athens” — was named a European Culture Capital of 2022 for its arts, food, architecture and other cultural scenes.

But most local Jews see few prospects for themselves in a country beset by economic turmoil. Between 1990 and 2000 — following Yugoslavia’s collapse; the ethnic wars in Croatia, Bosnia and later Kosovo; and the imposition of crippling sanctions by the United States, the European Union and the United Nations — Serbia’s GDP tumbled from $24 billion to $8.7 billion. By 1993, nearly 40% of Serbia’s people were living on less than $2 a day, and at present, the average Serb earns approximately $430 to $540 a month.

Despite those difficulties, Serbia agreed in 2017 to pay just over $1 million annually over the ensuing 25 years to its remaining Jews as compensation for property nationalized by the postwar communist regime. Half of that money goes directly to Jewish community organizations, 20% to Holocaust survivors and the remaining 30% to projects that aim to preserve Jewish traditions.

Since 2012, the Novi Sad community has also earned income by renting out its huge synagogue to the municipality for classical music concerts. In return, the city maintains the complex as a historic monument, and it is now repairing the synagogue’s roof and fixing leaky water pipes.

“These buildings were close to collapse,” said Trajer. He added that the city’s neglected Jewish cemetery can look like a forest. “So we are cutting the trees and struggling to put up fences.”

Although antisemitic incidents are not too common, Serbia, like most other countries in Eastern Europe, also contends with a strong nationalist streak. Trajer, who monitors antisemitism closely, said around 1,500 Serbs belong to extremist groups, of which perhaps 120 are active. Serbian Action, a small group of neo-Nazis, occasionally holds rallies and spray-paints antisemitic, anti-immigrant and anti-gay graffiti on public buildings.

“In high school, my history professor joked that Hitler couldn’t get into an art academy, and that’s why he decided to kill the Jews,” said Teodora Paljic, a 20-year-old Jewish university student. “I don’t talk about these things with people I don’t feel safe around.”

She said that “Life in Serbia is very difficult” because “all the prices have gone up, but salaries haven’t increased since 2019.”

Novi Sad is the capital of Vojvodina, an autonomous province that covers much of northern Serbia, and at the local Jewish community’s zenith, 86 synagogues flourished in the province. Today, only 11 remain standing, and most have fallen into disuse.

Mirko Štark, president of the Jewish Community of Novi Sad, said Jews first settled in the city in the 17th century, shortly after its founding in 1694 under the Hapsburg monarchy.

“When the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where most Ashkenazim lived, introduced new laws that restricted Jews from living in cities, many people ran to the border area, where these laws were not so strictly enforced,” Štark said. Later, when the Serbs captured Vojvodina, those restrictions were rescinded, and the Jewish community blossomed.

Following World War I and the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes — later Yugoslavia — Novi Sad’s Jews enjoyed a cultural and economic renaissance that saw the formation of a Jewish community center, athletic clubs, choirs and several Jewish newspapers.

That renaissance ended abruptly in 1941, when the Hungarian army, in collaboration with Nazi Germany, occupied Novi Sad, making life for Jews intolerable. Over a three-day period in January 1942 now known as the Novi Sad Massacre, the Hungarians rounded up more than 1,400 Jews, seized their property, shot them in their backs and threw them into the freezing Danube River.

After Hungary’s capitulation to Germany, armed guards herded the city’s remaining 1,800 Jews into the synagogue and kept them there for two days in deplorable conditions without food or water. On April 27, 1944, the Nazis marched their weakened Jewish captives to the train station, then forced them on a train to Auschwitz that took two months to arrive due to Allied bombing.

Only 300 of Novi Sad’s Jews survived the Holocaust, and rebuilt the community virtually from scratch in the ensuing postwar chaos.

“There were no religious people anymore, and no rabbi,” said Štark. “Many went to Israel in the first aliyah. The small number of Jews remaining tried to keep the community alive, opening a kitchen to provide food for people who couldn’t buy for themselves. My grandmother survived Auschwitz. She worked in that kitchen.”

According to Trajer, from 1948 to 2022, no Shabbat services were held. These days, Trajer conducts all religious services because he’s the only one who knows the Hebrew prayers fluently.

With 640 members, Novi Sad has the nation’s second-largest Jewish population after Belgrade. The capital is home to more than half of the country’s 3,000 Jews, out of a total population of 7.1 million. Smaller Jewish communities can also be found in Subotica, Niš and other cities. Only the synagogues in Belgrade and Subotica — the latter located a few miles from the Hungarian border — still function.

Most members of the Novi Sad community, including Štark, have married non-Jews.

“My wife is not Jewish. Neither was my mother. Only my father was Jewish,” he said. “After World War II, the choices for finding husbands and wives within the community was limited. For this reason, we accept non-Jewish spouses as members. This is the only way to survive.”

Štark, 70, is a retired professor of media production who worked for years at Novi Sad’s main TV station. He’s also the longtime president of the synagogue’s choir, HaShira, which sings in Hebrew, Ladino and Yiddish and recently won an award for its performances in neighboring Montenegro. Only three of the choir’s 35 members are Jews.

“When I began my mandate as president a year and a half ago, we woke up many activities in the Jewish community that had existed only on a small scale before,” he said.

Besides the choir, these include the Zmaya dance troupe as well as a Jewish culture club that meets every Tuesday at 6 p.m. to discuss books and Israeli movies. There’s also a “baby club” for small children and another club for teens, whose activities are led by two adults. Hanukkah and Passover are celebrated by families together, and on Tu B’Shvat, the community plants trees.

The community is also investing in its members, and Paljic is emblematic of that hope.

Paljic, interviewed at the trendy Café Petrus, a 15-minute walk from Novi Sad’s Jewish cemetery, is the daughter of Jewish parents who met at a Purim party in Belgrade.

“My grandparents were killed in Jasenovac [a notoriously brutal concentration camp], but my best friend’s grandmother survived Auschwitz,” she said. “The problem is, people don’t talk about Judaism because they’re scared. There is still antisemitism. Last year, somebody drew a swastika at the entrance to the Jewish cemetery in Belgrade. We were all shocked.”

This summer, Paljic worked as a counselor at Hungary’s Camp Szarvas, which brings together young Jews from throughout Central and Eastern Europe. The camp welcomed 20 children from Novi Sad this year; the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee paid their tuition.

While she would like to be close to her family, Paljic said she must be practical.

“I want to go somewhere outside Serbia when I finish college,” she said. “I don’t see my career here. I love art history and photography, but there’s no money in that in Serbia.”

Despite the challenges, Štark isn’t ready to say kaddish for Novi Sad’s Jews just yet.

“We will keep the Jewish spirit alive here. We are working hard, starting with the children,” he said. “If we don’t, everything will die in five or 10 years. So it depends on us.”

41 notes

·

View notes

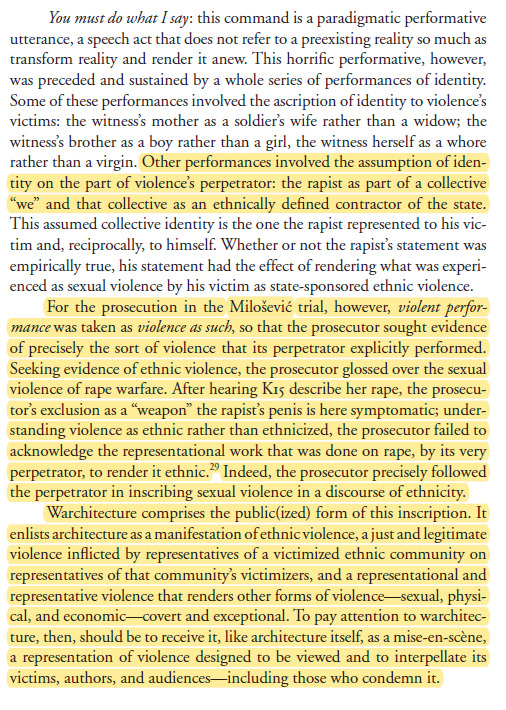

Photo

Dear friends , We are happy to announce that ”Socialist Modernism in Former Yugoslavia”, the photo album/digital guide in 2nd release of @_BA_CU ‘s planned series, is available in 800 copies. Those who are interested in #SocialistModernism are able to order the book on 👉🏻 @UrbanicaGroup @ushopamazon 👈🏻 distributor page, (Link in our profile) ; link: http://urbanicagroup.ro/ushop/ or AMAZON: https://www.amazon.com/s?me=A33QJE9SPOCVM4&marketplaceID=ATVPDKIKX0DER by selecting the Photo album from among the books listed. (Shipping worldwide with DHL) #SocialistModernism #_BA_CU The photo album includes landmarks of socialist modernist architecture in Former Yugoslavia – from the 1950s to 1980s. The preface by prof. Sandra Uskokovic, B.A.C.U. Association explains socialist modernist tendencies, it presents – in color photographs – a functional image of the buildings and their often original elements that synthesize local culture and traditions, while bringing you up to date with their current state of conservation. At the beginning of the book, a map shows the location of each of the buildings described. The 67 landmarks included in this volume have been organized by function, into six sections. The book contains the authors’ view on Former Yugoslav modernist architecture. Print run 800 Pages 192 +1 Spread/ YUGO-SOC MOD Map Croatian, Serbian and English Size 26×28.5 cm Weight 1.25 kg Designed and published by @_BA_CU Association 1: Eastern Gate of Belgrade, Rudo Buildings, (Istočne Kapije) Belgrade, Serbia, 1976, Architect: Vera Ćirković 2.3 5pic: Lamela Bildings - Novobeogradski blokovi / Block 61-64 Belgrade, Serbia,1970s, Urban design Josip Svoboda, Architect Milan Miodragovic - 7 pic: Avala Tower Belgrade, Originally constructed in 1965, rebuilt 2006-2009.. 10 pic: "Genex Tower" Belgrade, Serbia,1977, Architect Mihajlo Mitrović 9 pic “Laza Kostic" primary school, New Belgrade, Serbia. 1974, Architects: Bozidar Jankovic, Branislav Karacic and Aleksandar Stjepanovic https://www.instagram.com/p/Cr0_ctJs58Z/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tri-Weekly Most Successful YWAMag Selection #103 : Ruine, Špicer Castle, Beočin, Serbia. © Jupiter Ovprsten :

The Tri-Weekly Most Successful YWAMag Selection #103 :

Ruine, Špicer Castle, Beočin, Serbia. © Jupiter Ovprsten :

#jupiter ovprsten#the tri weekly most successful YWAMag selection#art#serbian photographers#composition#perfections#decay#talents on tumblr#visual poetry#femininity#oxymorons#visual art#contemporary art#masterpieces#trees#architecture#nature#gifts#magic#art in serbia#artists on tumblr#photographers on tumblr#original photography

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

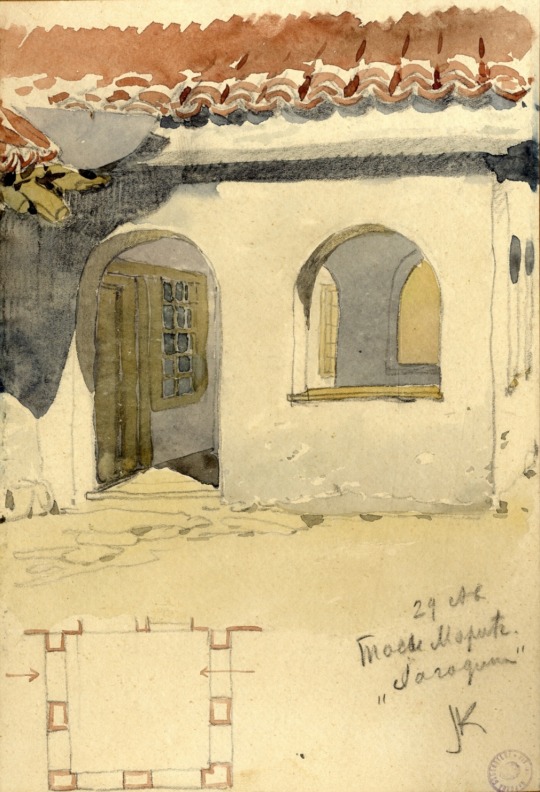

Serbian traditional houses, Illustrated by Nikolai Petrovich Krasnov. Digital National Library of Serbia

He came to Belgrade in 1922 and got a job in the Architectural Department of the Ministry of Construction, where he worked as a contract engineer, construction inspector and head of the Department for Monumental Buildings and Monuments.

Displaying his high creative skill and using it to build the capital of his new homeland, which wholeheartedly accepted him, and soon became a respected state and court architects. In the period from 1923 to 1939, he worked on the design, construction, completion, adaptation and decoration of the most important state buildings, numerous profane buildings, churches and memorials.

He marked an entire period of Serbian architecture with his original treatment of heraldic decoration on the facades of his buildings.

185 notes

·

View notes