#so no children get nightmares of airstrikes

Text

So, I don't speak a lot here or anywhere, but today, I want to speak about the "brave" and "honest" person you might know here as muttpeeta or as attheredmind on AO3 which I had the unfortunate experience of following someone like her for a couple years now without knowing the kind of person she is.

So, following some meaningless squabble about New York Times POTT, someone brought up to her attention -or she might have addressed that herself- that people associated with the current genocide going on in Gaza AND West Bank (where there is no KHAMAS!) Were more deserving to get the award or title whatever, since the newspaper gave it to president Zel of Ukraine last year. atthered mind didn't like that apparently, so she answered by some nonsense and amidst her replies to the anons she claimed she is neutral and that she sympathize with the "people suffering in Gaza and Israel". But then she followed that sweet talk with tags accusing the Palastinian and Gaza's side of committing crimes of murder and rape against "Jews". Now notice the stereotypes which she uses. Saying Jews instead of Israeli. As if the Palestinians are targeting all jews. And no Jews stand against Israel.

Then in another reply, she simplified the situation as "war" between Muslims and Jews.

She was so upset about ppl calling her out about that as anons and wanted someone to confront her by their names. So I did. And guess what, she run away and blocked me 🙂😂

But sorry muttpeeta, I'm not letting your Zionist propaganda slide. And everything will be backed by actual evidence and sources -Israeli ones too- and not words in the air.

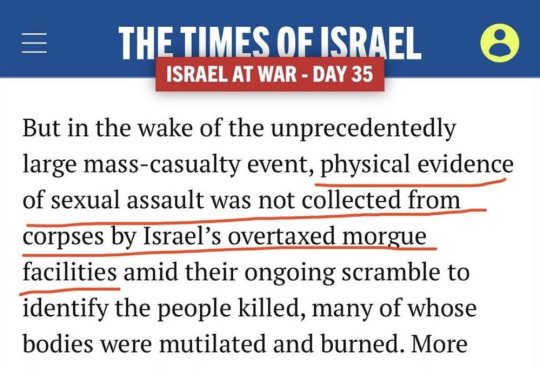

So first things first. Muttpeeta claims about rape and murder were addressed multiple times by both Palastinian and Israeli sides. Israeli government said they found no evidence of sexual assault. Image from The Times of Israel.

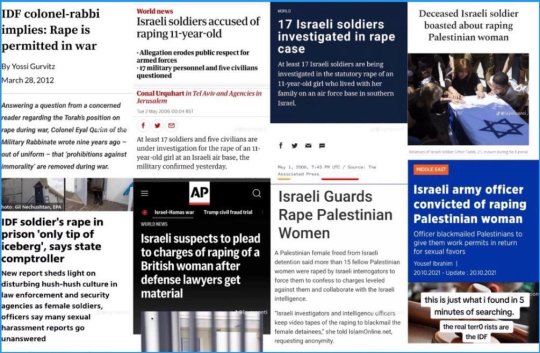

On the other hand, there are uncountable vitrified cases of rape crimes by the Israeli military, but Muttpeeta won't mention that ofc

And I think we can determine the truth of these claims, on both sides, from the statements of women held captive.

youtube

youtube

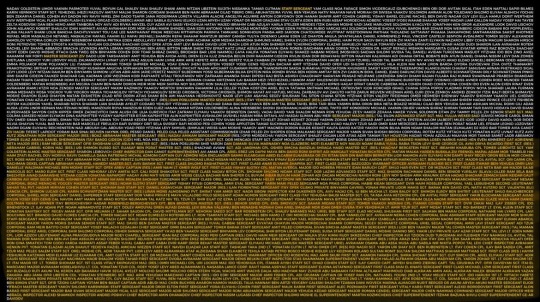

The murder... there sure was murdering cases by Palastinian personals in that day. Which I personals considered grave mistakes that need punishment. And Gaza's government stated that those actions -and civilians kidnapping by the way too- were against the orders given. Also that most of these cases were carried out by persons not affiliated with Hamas. But to claim that all the dead were civilians and by Hamas hands? Look for yourselves. The white names are civilians, and the yellow are military

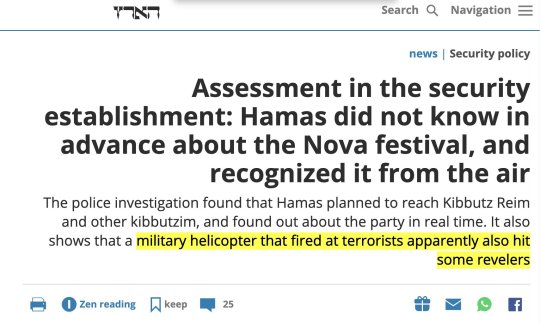

Ok, are we certain all tgese were killed by Hamas? No. In more than one statement, Israeli officials and officers in their panic revealed that Israeli army killed civilians that day

Watch

While Hamas condemned killing and kidnapping civilians, you will find the Israeli government shamelessly calling to use nuclear on Gaza, or kill 150 thousand of its population or calling these people human animals... things you would have heard of from Hitler and his Nazis.

Muttpeeta didn't like when Intold her this.

Finally, this is not war between "Muslims and Jewish" this is a genocide carried out by one of the strongest armies in the world, backed up by superpowers innthe world against Palastinians who have no water, electricity, medicine, food let alone an army to defend them. This is a genocide against Palastinians, Muslims AND Christians. Just 10 days ago Israeli bombes one of the oldest churches in the world, killing many of the ppl who were seeking a safe place there.

Here is a great video from President Carter about Palastine

And for further informations I would recommend this video here

youtube

It has English caption. It's long but worth it. And it's all from Israeli sources.

I would also strongly recommend following Norman Finkelstein, Miko Peled, Noam Chomsky, who are ALL Jews, and Miko even Israeli, but they have the humanity in them to stand against Zionism and its genocidal agend.

To Muttpeeta, next time, either be contented with anon replies (I wasn't one of them, btw) or be brave enough to continue a debate once you start it. I hope someone, even if anon delivers this to her or it reaches her, is in any way.

#palestine#gaza#so no more blood shed#so no entire families get wiped out of globe each night#Youtube#free palestine#so no children get nightmares of airstrikes#so Muslims Christians Jews get to live in peace once more#as they did a hundred years ago#so no human dies out of hunger#so no human dies of medicine lack#so no more children get orphan#so no parent has to bury their own kids

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, among the hundreds of tragic stories, I am sharing my painful story.

My name is Ahmed Khalil, I am 6 years old. I was at the beginning of my education, trying to learn, participate, and play with other children. My family consists of 8 members, including my mother and father. My father has diabetes, my brother Fathi is blind, my other brother Abdullah has autism, and my brother Mohammed was injured in his leg by shrapnel from rockets.

On October 7, 2023, the war began and has not stopped since. The airstrikes and Israeli shelling caused fear for me and my family. We could not endure the massive explosions that felt like recurring earthquakes and the red flames sweeping through the area. We were forced to flee to southern Gaza based on orders from the Israeli forces, leaving our beautiful apartments behind. We went to a UN refugee school in Deir al-Balah to escape the terror and death.

We stumbled into a different life full of suffering from every side, living through the most painful hell of war. I developed malnutrition due to contaminated water, poor hygiene, and the spread of infectious diseases with no suitable medicine available.

The situation is catastrophic and unbearable. “There is only death left in Gaza. Even death has become a privilege because it provides a sense of relief.” My older brother Mohammed and I begged our father to leave Gaza, but it was extremely difficult due to the high costs. My father lost all his property during the war, including his electronics repair center and apartment, which were completely destroyed, so he has nothing to help us travel out of Gaza. There is no safe place in the Gaza Strip.

I pray every moment for the end of this war and a ceasefire. The ceasefire is not just a call; it is a desperate cry to end the helplessness and despair spreading to every corner after more than 11 months of war. We flee from death every day, only to wake up the next morning to try to escape it again. My heart is heavy, unable to bear the recurring nightmares, and the overwhelming flood of news about blood, displacement, loss, and despair pouring from Gaza.

Every minute feels like a struggle. No one should have to endure this injustice, segregation, and discrimination. The ongoing shelling in southern Gaza and the intense bombardment of residential buildings in Deir al-Balah make everyone feel unsafe, believing they might be the next to face tragedy. Communications are cut off. We are exhausted and cannot bear more tragedies and losses. We are currently living in a classroom of the UN center, which is crowded with people, including my relatives and cousins. My poor father sees our pale faces and weak bodies and stands helpless due to the lack of money and resources.

I am still six years old, and I never thought I would witness such a brutal attack with complete disregard for human values. I am deprived of my basic rights, including health and education. I need to rebuild my life with my family abroad and receive better healthcare. Traveling to Egypt would cost at least $5,000 per adult and $2,500 per child, which is an enormous amount given the harsh living conditions and the blockade that has lasted for 17 years.

Therefore, I ask you to donate so that we can evacuate Gaza to safety. Please continue supporting our campaign by donating if you can and sharing it with your friends and family. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us get closer to our next goal and brings us nearer to securing a safer future for my family.

#Gaza#all eyes on rafah#gazaunderattack#gaza strip#free palestine#i stand with palestine#save palestine#free gaza#gofundme#palestine aid#gaza genocide#palestinian genocide#save gaza#save rafah#artists on tumblr#trending#donations#gfm#gfm palestine#explore#self help#please help

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

every day i see the news my heart breaks

i will never, ever, feel the heartbreak the people and children of palestine do

i will never be blown to bits. i will never be orphaned in an airstrike. i will never be killed on the street for drinking water.

i will never be killed for walking to get flour. i will never be buried under the rubble of my house with my family. i will never be left for dead in a car with my deceased relatives.

every death is unimaginable, i can't fathom it.

i am safe — and they are suffering.

they are in agony, fear, dread.

every. single. day.

i want to help.

how could you not want to help?

i have no money to spare, i can't attend protests, but by all of my heart and soul i will spend every last minute sharing the news, the updates, the global strikes, the boycotts, the protests, the donations.

thank you thank you thank you to everyone who CAN and DOES donate

it's not a thank you from me, it's a thank you for them. the palestinians we cannot reach but we are fighting for.

thank you to everyone who shares, protests, boycotts - when they can't do much else.

it is so fucked up. that i am so powerless. that they are so powerless

to stop this. to stop fucking genocide

it is nothing but genocide.

i can't imagine the people in power. the usa and uk governments. i can't imagine how they live with themselves.

they watch. they fund. they help genocide.

as if this hasn't happened before. as if it hasn't been happening for decades. longer than i've been alive.

i am disgusted. by my own government. they enforce transphobia, they support the destruction of the internet — but above it all, they willingly allow lives to be taken. in the most horrifying ways you couldn't dream in your darkest fucking nightmares.

nothing that my government could ever do to me will surpass what they are funding.

nothing that my government could ever do will make me forget.

the eyes of the world are on palestine. the eyes of the world are on gaza. the eyes of the world are on rafah.

the world sees what israel has done.

no matter when the war ends, nothing can forgive them.

i do not hate jews. i hate what israel is doing and has done. the lives they have taken, the terror they have inflicted. i do not care for religious dispute. what part of religion funds genocide.

and i will sit, safe, in my home, and weep for those who never can again.

how could you not?

needed to get this off my chest. please, click on the links below and donate, boycott, protest, share if nothing else.

eSims for Gaza

Donate now to save children's lives on Gaza Strip (PayPal)

UNRWA

Daily Click for Palestine (EASY, EVERYONE CAN DO THIS)

Palestine Masterpost-Masterpost

INFORMATION AND PALESTINIAN DONATION ORGS LINKS

#palestine#free palestine#free gaza#gaza#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#palestine strike#israel#boycott israel#from the river to the sea#gaza strip#rafah#eyes on rafah#eyes on gaza#eyes on palestine#palestinian children#palestine donation#esims for gaza#global strike week#global strike for palestine#palestinian genocide#stop the genocide#fuck israel#israel is committing genocide#israel is a terrorist state#arab.org#unwra#donation links#palestine resources

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

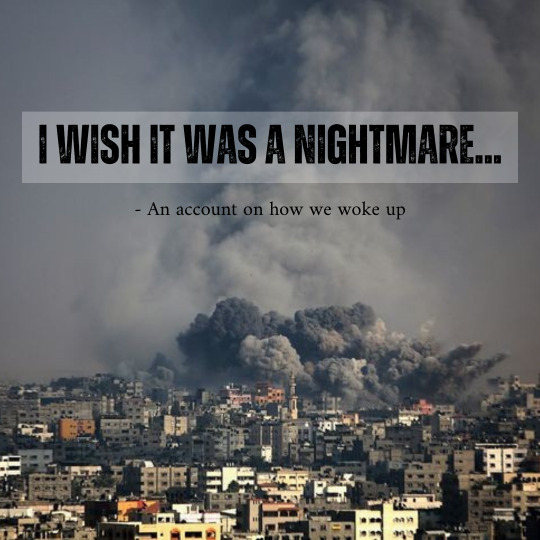

Reblog this

How many of such moments came upon us, when we earnestly prayed, that this bloodshed is a nightmare. How many times we wished to fall into a deep slumber and when we wake up, we're told, it was just a bad dream. Everything is fine, no one was killed...all children are safe in the arms of their parents, their laughter is echoing the streets of Palestine.

I have found myself making this same Dua' over and over again.

Ya Allah let this be a nightmare. Wake me up to how I thought the world was. There were struggles. But not the slaughtering of children.

And then something hit my mind like a boulder.

*Isn't this infact, waking up to the reality of this world?*

This world was always like this. Injustice and oppression. Fasad and Fitan. Believers suffered with the worst in the hands of demigods of this world, because of their faith. Why did we miss this ever so apparent reality, That we were put here to be tried and tested? Why did we become so heedless that we forgot our purpose here?

And I felt I had just woken up. To the sirens with the colour of blood. But it wasn't just a colour...it was the blood of our Ummah.

What I was praying to be a nightmare, was a scalding truth. And what I thought was life, was actually...a delusion. This Dunya was nothing but a deception. A beautiful lie.

I tried to remember the dreams we were living before we were woken up to the truth.

We were chasing temporary pleasures of this deceptive world.

My home, my life, my pain, my struggles. I couldn't get a job, life is difficult. That person I loved left me, life is difficult. I couldn't manage to build a bunglow and had to settle for a one storey house, life is difficult. People have Cars, I am using a bike, life is difficult. I wanna travel the world, but I have responsibilities over me, life is difficult. I feel so lonely all the time, life is difficult. I cannot leave that haram relationship, that habit of watching pornography or listening to music, or talking bad about people....life is difficult. I cannot find time to learn Quran, I am busy in college or work...life is difficult. Etc...etc...

And now when I look at the people of Palestine... standing over the rubble of their once beautifully habitated homes, with dusts on their faces with the streaks of blood, helpless and forlorn because all of their loved ones died and now the only thing they care about is rescuing their dead bodies in one piece. When we get to know that they're sleeping on the streets, eating whatever or nothing, struggling to find clean water, holding the drips in the hospitals because there's no bed or stand, standing the whole night as they pump oxygen to that one family member who managed to survive serious injury. Unsure if the next bomb hits their building and unsure if they'd get to see the next day.

And then I see them proclaiming Shahadah, Saying Alhamdulillah. I see them kiss their dead child and say Alhamdulillah. I see them write loving notes on the shroud of their spouse. I see them distributing candies because their family achieved martyrdom. I see children write their wills on who should take their toys and school bag when they die. I see the children playing in soil dug up, and saying... We play here and we will be buried here.

And it crushes me on how we have been running behind all the things that could be destroyed in one airstrike. How foolish we were to think that Dunya was meant to be gathered. No. We could never catch this Dunya. We just tired ourselves in vain. We forgot our purpose. There was a life of truth beyond our "I" "Me" "Mine" ... We never lived for that. We were so obsessed with our own pain that we missed looking elsewhere. Think about it, do we even deserve to complain about our pain to Allah anymore after seeing what the fellow Muslims are suffering for the sake of our Deen? How will we give account of the blessings we're using right now whilst knowing the children of our Ummah died hungry? Think about it and let it break our hearts into million pieces. Let not the grief of Ummah leave us ever so we keep reminding ourselves of the betrayal of Dunya. We are blessed that this wake up call is not the Qiyamah and Sun rising from the west. Allah has given us a chance to repent and look at what's important and better for our eternal life. Alhamdulillah. Now, we shouldn't let the blood of our brothers n sisters be forgotten. Let this be a reminder to turn back and start living feesabeeliAllah. Leave off things displeasing to Him and start doing everything for His Pleasure. We have been given these extra days so we could benefit from it, so don't let the slumber of heedlessness hit us again. Disown every dream and goal you had for this world, if it doesn't involve Deen in it. Forsake every desire that would make your time with Allah less. Be firm upon your Tawheed. And live for Tawheed.

- Umm Taimiyyah 🕊️

#free gaza#gaza#palestine#free palestine#palestine forever#gazaunderattack#sudan#quranandsunnah#islamiyet#tawheed#stop palestinian genocide#tumblrpost#reblog this#tumblr#tumblrgirl#love#aesthetics

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even though Jin was generous enough to grant Abaddon a few hours of freedom each day, Abaddon never ventured far from their home in Yakushima. He would sometimes go deeper in the woods, seeking solitude from where he’d expect to encounter nobody but animals. Thanks to Kazuya’s machinations, humanity now knew about demons, &, for obvious reasons, society condemned devils. Abaddon avoided frightening people or causing pandemonium by appearing in public. Although he could disguise himself as a human, he refrained from doing so. It didn’t feel right using Jin’s appearance after framing him for a plethora of war crimes.

So, Abaddon stayed indoors, immersing himself in human culture through television. That's what he was currently doing. He sat cross - legged on the floor in front of an illuminated screen, absorbing the news. Gas prices were rising, which mattered little to him. Violent Systems was releasing an update to the Combot series, & a movie franchise was getting its 45th sequel. Abaddon hadn’t seen the others yet.

Despite the news being largely irrelevant to him, Abaddon found it fascinating. It offered a window into the world, revealing what has preoccupied the humans. He enjoyed himself, with a cat purring in his lap ( forgive him, Jin had 5 other cats & Abaddon couldn’t remember this one’s name ) & an empty, greasy plastic wrapper that once contained deli - slice ham lying beside him.

But Abaddon’s enjoyment waned as the news shifted from entertainment to current world affairs. Over a year had passed, yet the world was still suffering from the Mishima Zaibatsu’s warfare. Images of ruined cities & homeless people, victims of the Zaibatsu’s relentless assaults, all flashed on the screen. The sight felt surreal, like he was experiencing a dream ( or, more accurately, a nightmare ) unfolding before him. Despite knowing he was at fault for this tragedy, Abaddon found it hard to believe in that moment.

He recalled the hatred that filled his heart. How he refused to give humankind a chance, viewing them as inferior creatures, pests that polluting the earth who were in a dire need of extermination. How he had wanted to rule over them as a wrathful God, slowly killing them as a punishment for alleged sins. What sins ? Abaddon couldn’t really answer that. His feelings had been driven by instincts from the true God who had created him. He was once God’s wrath. Yet, that chapter in his life now felt distant, as if it had only occurred in a twisted imagination.

Watching the news was a stark reminder that it all had transpired, & he was solely responsible for killing thousands & thousands out of rage & delusions of divinity. As he saw locations in desperate need of reconstruction, his heart shattered into tiny pieces, its shards stabbing his insides with a burning ache. He longed for nothing more than to help people now, but how could he, when he had been the one to rain hellfire down ?

His hand reached out to the TV screen with a stubborn tremble he cannot cease. His sharp talons clacked against the glass. Then a woman appeared, middle - aged & worn down by stress. “My husband,” she spoke, voice strangled by tears, “my husband wasn’t even a soldier in the war. He was a truck driver, & - & the Zaibatsu had ordered an airstrike while he was . . . ” her voice drifted away, & her face suddenly blurred within his vision. He pulled back after experiencing a sensation that soaked his own cheeks.

Abaddon was crying. This poor woman would never see her husband again because of him. There were children who lost families, there were grooms who lost brides, brothers who lost sisters, century old homes that were torn down. Suffering filled the world, & humankind wasn’t the culprit.

He was.

Seeing a face of a victim reminded him of the countless like her. There were so many that Abaddon’s brain lacked the capacity to remember every single one, even if he met them all. A cruel reminder of how monstrous he once was. But he couldn’t be that monster again; he would NEVER be that monster again. Abaddon couldn’t fathom causing such tragedy again. He couldn’t even bear the thought of it without feeling ill.

His hand moved away from the TV to wipe at the tears running down his face, the jagged edges of his demonic palms scrape his cheek, making it a painful red.

A part of him wanted to wake Jin, let him take control of the body again because Abaddon questioned whether he deserved this freedom. Another part of him, however, believed he should watch the consequences of his actions.

His glistening, golden eyes stayed locked on the screen after deciding to continue watching, occasionally blinking to regain clear vision. The cat in his lap leapt off, scampering away to likely find food, or play with another feline.

The news announced an upcoming special regarding the war in a half hour, seemed like he'll be here, alone, for a while . . .

#👿 - ᴡᴀɢᴇᴅ ᴡᴀʀ ɪɴ ᴀ ғɪᴇʀʏ ʙʟᴀᴢᴇ // (ic)#✏️ - ғɪsᴛ ᴍᴇᴇᴛs ғᴀᴛᴇ // (t8 timeline)#✏️ - ᴘʀᴇᴄɪᴘɪᴄᴇ ᴏғ ғᴀᴛᴇ // (drabbles)#// mostly bc i wanted to write abby actually ... acknowledging this LOL sdgjndfgjnggf#// him being a big Pet is fine and all but sometimes y'gotta remember ... y'know ...#// FGJNDFGNFG#// he's a lil sad with regret now

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

finally- the gofundme is now live!

the time is now for anyone who wants to aid in the relief efforts to help those of us still left behind to literally die in gaza. as i type this there is quite literally a famine in north gaza that is actively spreading- consistently killing more people daily now than the airstrikes. children are dying after starving for weeks- people are selling tree leaves as food and most cannot even afford those.

we are living through a nightmare. hell on earth. i'm still here though, am i lucky for that? i must make myself lucky. i have no other choice. my little brother and my mother were not so lucky. no match for the airstrike that i am still suffering the injuries from.

i want to thank my friend in america for helping me organize this. i could not do this without her. thank you.

anybody- friends in the west- do you see what is happening? please help me. help us. i refuse to leave but any funds that are received are also going towards helping those who wish to flee to safety across the border to egypt get to where they will be safe once and for all. it is a massive endeavor all around. every resource is extremely limited. we are working with what we are given at this point.

please reblog for visibility- if you can help in any way, i extend my very being out to you through these words with what i would be content wuth being my final plea- help us. help gaza. we will not be erased. we are still here.

#gaza genocide#free gaza#gazaunderattack#gaza#gaza strip#save gaza#news on gaza#gazaunderfire#israel is a genocidal state#israel is committing genocide#gofundme#go fund them#go fund him#gofundus#stand with gaza#rafah#free palestine#palestine#stop the genocide#end the genocide#palestinian genocide#israhell#israel#visa cashapp rb#rb#ok 2 rb#ok to rb#important#save#please consider donating

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

a person who supports Palestine followed me, i obviously followed back. I went to their blog to see what exactly they have and im....

so deeply disturbed.

They have uncensored videos and pictures of children being rushed into hospitals, being bombed and people being pulled out from under the rubble.

@heba-20

this is their account if you want to check it out, but please be careful it was so inhumane and extremely disturbing and i cant believe that fucking is**** is doing this TO CHILDREN.

CHILDREN.

like how do you not have your guts feel like their being turned inside out when you know that innocent people are dropping like flies. How does your heart not skip a beat when you see bloody children being rushed into the hospital. How does your conscious not scream when you decide to bomb homes and hospitals just because people want to be safe.

Are you even human at this point?

to put it simply, no, theyre not human. nor are palestinians human to them, in fact, theyre "human animals"

ive seen hebas blog before, and ive also seen the videos she posts. ive also seen videos thy arent on her blog that are arguably more horrific. the things ive seen ? that shit stays w you. it never leaves. ive had nightmares abt the things ive seen concerning israel-palestine, and i guarantee its a hundred times worse for the people living there. if i get nightmares just from watching videos abt it, imagine the people who live it. its their day to day lives. another day, another bomb dropped, another airstrike, another friend in the hospital, another child dead, another funeral to attend.

its sickening to think about.

#palestine#free palestine#israel#gaza#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#save palestine#fuck israel#فلسطين#israel is not a country#anti zionisim#anti zionism#anti zionist#anti israeli#free gaza#pray for palestine#anti israel

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, 🌹🇵🇸🍉

I hope you are well.

Could you please help me reblog the post on my account to save my family from the war in Gaza? 🙏

I am new to Tumblr and also to GoFundMe.🙏

I hope you can support and stand by me at the beginning .

"Note: My old account has been deactivated, and this is my new tumblr

Thank you ♥️ .

---

PLEASE DO NOT IGNORE

‼️Even if you can’t donate, please at least share! ‼️

Iyad and his family’s gfm is currently at $8010, let’s get it to $8500!

Their story:

My name is Iyad Sami, and I am 36 years old. I have been married to Amal Mahmoud for thirteen years, and we have four children: Sami (11 years), Mohammad (9 years), Sarah (7 years), and Saad (5 years ). We are from Palestine, specifically the Gaza Strip, which has been under siege for more than eighteen years.

On the first day of the war, Israeli airstrikes hit our home, killing two of my brothers and injuring the rest of the family, including my younger brother. There were no hospitals in northern Gaza capable of treating the injured due to the situation, so I carried him and went to the southern part of the strip seeking treatment.

During this period, the situation has worsened. Continuous bombings, food and water shortages, and the lack of safety have made our lives a continuous nightmare. My children suffer from hunger and fear, and my wife is doing her best to keep them safe. As for me, I feel helpless and mentally pressured for not being able to protect and support them.

I appeal to anyone who reads my story. I ask you to look at us with compassion and help us collect even a little money so that we can leave this hell. I want to find a safe place where we can live in peace, where we do not fear bombings, and can meet our basic needs. I want my children to live a dignified life, to receive education and healthcare, and to feel safe.

I hope my story resonates with those who read it and that it finds compassionate hearts willing to help us in this ordeal.

#free palestine#palestine#gaza#free gaza#palestine fundraiser#mutual aid#donate to palestine#all eyes on rafah#palestine aid#save palestine#palestine news#gaza mutual aid#aid to gaza#help gaza

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, 🌹🇵🇸🍉

I hope you are well.

Could you please help me reblog the post on my account to save my family from the war in Gaza? 🙏

I am new to Tumblr and also to GoFundMe.🙏

I hope you can support and stand by me at the beginning .

"Note: My old account has been deactivated, and this is my new tumblr

Thank you ♥️ .

---

Please help Iyad and his family get to safety. They have only collected 10,402 of their 20,000 goal to afford escaping this genocide. Their campaign has been vetted by @90-ghost and @northgazaupdates2

From Iyad's campaign:

My name is Iyad Sami, and I am 36 years old. I have been married to Amal Mahmoud for thirteen years, and we have four children: Sami (11 years), Mohammad (9 years), Sarah (7 years), and Saad (5 years ). We are from Palestine, specifically the Gaza Strip, which has been under siege for more than eighteen years.

We lived a simple life, barely meeting our basic needs. Despite the difficulties, we felt content and happy being together as a family. On October 7th, a new war broke out, turning our already hard life into an unending nightmare.

On the first day of the war, Israeli airstrikes hit our home, killing two of my brothers and injuring the rest of the family, including my younger brother. There were no hospitals in northern Gaza capable of treating the injured due to the situation, so I carried him and went to the southern part of the strip seeking treatment.

But fate was cruel; the roads back were closed, leaving me trapped in the south while my wife and children remained in the north. Since that moment, I haven't seen them for more than eight months. My wife and children now live in a displacement school in the Zaytoun area, while I live in a tent in the Deir al-Balah area.

During this period, the situation has worsened. Continuous bombings, food and water shortages, and the lack of safety have made our lives a continuous nightmare. My children suffer from hunger and fear, and my wife is doing her best to keep them safe. As for me, I feel helpless and mentally pressured for not being able to protect and support them.

I appeal to anyone who reads my story. I ask you to look at us with compassion and help us collect even a little money so that we can leave this hell. I want to find a safe place where we can live in peace, where we do not fear bombings, and can meet our basic needs. I want my children to live a dignified life, to receive education and healthcare, and to feel safe.

Help me achieve this dream, so we can live in peace, away from these wars and destruction.

I hope my story resonates with those who read it and that it finds compassionate hearts willing to help us in this ordeal.

0 notes

Text

I don't know how you guys feel anout them, but I just love the Skellington kids, almost as much as I love Jack AND Sally, so...

Nightmare Before Christmas Headcanons PART 2 (FT. The Skellington kids)

Right off the bat: lay a hand on ANY of the kids, and Jack and Sally will put you in a grave.

Jack isn't a big fan of Fourth of July. The fireworks make him remember getting shot out of the sky.

Sally remembers her life before Halloween Town. She doesn't like talking about it.

People rarely see Sally angry. And that's an insanely good thing.

Jack loves abstract patterns like Sally's dress, where different colors and styles collide and make something incredible.

The witches and other females were insanely jealous of Sally when she and Jack got together. That jealousy became, 'well, damn it' sorrow when they saw the triplets.

Lock, Shock, and Barrel have interacted with the triplets, but don't get closer than glances toward each other on the street; they don't want to face Jack's pure, unbridled fury or see Sally mad.

Jack is extremely glad to have all three triplets, mainly because he wanted to have children back when he was alive.

The children asked about the electric chair, and Jack lied bysaying it was something he found and liked. Luna was smart enough to catch it and asked what really happened. The only thing Jack let her know was that he died, and she didn't need to know anymore than that.

Never try lying to Sally. She'll know instantly.

Jack's 87% sure Sally's never killed anyone, or was angry enough to get to that point, but he genuinely doesn't want to know what either is like.

Daemon is arguably the closest with Sally

While the Easter Bunny still hasn't forgiven Jack, Santa at least knows Jack is harmless... as long as he has something to keep him busy and away from taking over holidays.

Jacob and Luna would absolutely kill each other, if they were alive. It never gets worse than a firefight, but Daemon still traps them in a 'get along' shirt and locks them in a room together.

Sally joined Jack on a Halloween scare once. You would be surprised at how much she got hit on.

She wasn't a fan of it, but got a clear idea of why Jack did.

After the Christmas incident, Jack listens to all of Sally's visions, which has made her consider messing with him, though she never did.

Zero's more than glad to have Sally and the triplets around; they keep Jack from doing anything crazy.

Luna, Jacob, and Zero are best friends; neither argue around him and Zero is just glad neither tries making him a model(looking at you, Daemon).

Zero's new favorite place to sleep is in Sally's lap.

Jack and Sally share a bed, but Zero keeps sleeping between them because the triplets are already enough for him.

Jacob doesn't like the sound of high notes on a violin.

Since all he tastes is cold peanut butter, Jacob and Jack have seen what different things taste like, things like apples, lemons, pumpkins, pickles, and even spicy peppers.

Jacob was severely disappointed at feeling like he was just eating peanut butter, but Jack claimex that this was his worst idea ever,in the worst way imaginabl; he ate a lemon slice like an orange, a pickle, and a pepper.

Jack's called the Pumpkin King because he was found in the pumpkin patch, and because his original idea was to break out of a pumpkin, which didn't work as well as he'd wanted.

Dr. Finklestien wasn't sure about Jack being a partner for Sally, but was sold when Sally tripped and Jack caught her and carried her for the rest of the day.

Despite Dr. Finklestien's opinions, Jewel absolutely loved Sally.

You should've seen her reaction towards the twins.

Lock tried hitting on Luna once, just once, and Daemon and Jacob drop kicked him, much to Jack's delight.

After the Christmas incident, Jack having a new idea is like a Targaryen being born, except instead of gods flipping a coin and the world holding its breath, Jack opens his mouth and the entire town holds its breath.

Here's what would happen if Oogie Boogie was still around or we had the triplets around during the movie or Oogie's Revenge

If getting flayed and cooked alive was because Oogie threatened Sally, then Jack would tear him apart with his hands, consequences be damned.

Jack would fight harder and be more brutal in his fights against Oogie in Oogie's Revenge.

Jacob would help, because he loves his siblings and mother, even though Jack would tell him to go home, where it's safe.

Oh, yeah, Luna and Daemon got kidnapped and hidden somewhere, but escaped and found Jack and Jacob.

Luna used a poison fog attack on Shock and bolted.

Daemon, however, was found in thr fountain because, and don't laugh when you hear this, he escaped, found some rogue, evil skeletons and ghosts, and then attacked one of them, jumping on a ghost's back and holding on as it flew and then vanished, dropping him; in its defense, he bites hard. The rogue skeletons amd ghosts caught up to him, and some larger skeletons saw him and he ran like hell, all of them behind him. To get away, he climbed up a tree, lit a large skeleton on fire, and then fell in the river, where he was carried until ending up in a sort of gutter system and into the fountain, where he was found.

He repeated the story to Sally and Luna and Sally genuinely wondered if Daemon and Jack had the same IQ.

Why does Sally worry so much? Because Jack's either a blind optimist, or genuinely couldn't tell he was getting shot at with airstrike missiles, didn't get that smoke and fire on Christmas is usually a bad thing, and didn't rethink the fact that people don't like getting scared on Christmas.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

A/N: i was talking to @agentnatasharomanov one night about Carol visiting alternate universes and seeing Nat alive again in each one of them, and my hands slipped and wrote this one-shot. set after endgame, this should be read as a standalone from world enough and time.

– – –

"There are over 14 million other alternate timelines out there," she remembers Natasha telling her once, a long time ago. They'd been curled up on the couch together - Natasha had sprawled herself out over Carol's body and buried her face into Carol's shoulder; Carol had to strain her ears to hear her. "There are 14 million other versions of us. I wonder what it's like to live in a world where I never got to love you."

"That's impossible," Carol had murmured quietly in reply, running her fingers through Natasha's red hair. "In every single universe, I'll be out there, looking for you."

(It's a lie, of course - they're neither ignorant or naïve, and they know that for every universe where they meet and fall in love, there are hundreds more where their paths never crossed, where Carol never became Captain Marvel, protector of the universe, and even hundreds where Natasha never left the KGB. But with the universe in a constant, chaotic upheaval around them, three years after Thanos snapped away half the population and caused the death of millions more, sometimes it's just comforting to indulge in fantasies, if only for a short while.)

Carol stays on Earth, long after the dust lingering from the battle against Thanos - the remnants of his armies - have settled.

There's so much to do - half of upstate New York had been flattened by the barrage of his airstrikes, and with the entire world population suddenly doubling in size, there's a certain urgency to their actions as the Avengers help the world recover, and rebuild. She throws herself into her work, lifting away the largest pieces of rubble she can, and carrying in new building materials - and slowly, slowly, she watches as the city begins to regain its shape.

She thinks that if she can make her body ache enough, if her muscles strain enough under the pressure she's putting them through, she doesn't have to think about the yawning hole that's opened up in the middle of her chest, threatening to swallow her whole.

It never really works.

Sometimes she still wakes up in the middle of the night, her face wet with tears and her mind still swimming in past memories, with Natasha's name on her lips.

So when Hope van Dyne approaches her with a job offer - she doesn't really know what it entails, other than "harmless, sightseeing trips into the past and alternate universes, we just need some data and we think you can help us." - she remembers what Natasha had told her once, in a better time and a better place.

There are 14 million other versions of us.

She agrees.

Her job takes her across various different timelines - she sees an alternate history where Peggy Carter becomes Captain America instead, and another timeline where she never meets Mar-vell, grew old with Maria, and died peacefully at the age of eighty-three. And then there are worlds where HYDRA wins, the Avengers are never formed, and the Earth is wiped out by Loki's invading army in 2012.

And - she sees Natasha alive, over and over again, in various different timelines, across multitudes of universes. Of course, they don't fall in love in every single timeline she watches - in some of them, Natasha lets herself die rather than join SHIELD, in others, she kills Clint instead, and never left the KGB at all. And there are others, too - she catches glimpses of herself, falling in love with Nat again and again, only for Vormir to happen, only to watch, helpless, a spectre in these timelines, as Natasha lets herself plunge off the edge of the world to save the universe.

These ones stick in her mind, and play themselves back like a film strip being looped, over and over again. They slink into her dreams, and turn them into nightmares.

She confides to Val over a drink, one day.

"I see her all the time," he voice wavers, and she clenches her fist, trying to force away the tears prickling at the back of her eyes. "I want her, Val."

"Well," Val tells her, ever-so-practical. "Just bring her back."

"I can't. They're not my Natasha."

The Natasha she sees most often - the KGB Natasha - will never know Carol, and they're set against each other on opposing sides of a war. The Natasha that goes on to join the Avengers is needed, she's a key player of the team, essential to that particular timeline, and Carol can't justify stealing her away, And in the universes where she and Natasha end up together?

She doesn't want another version of herself in some other time and some other place to feel this same hollow, hungry pain she carries around all the time.

It's not the kind of suffering she would ever wish on anyone - not even her worst enemy.

"Just a few more left," Hope tells her the following morning, running a concerned eye over the dark circles under Carol's eyes. "We're sending you to 2022 this time."

Carol shoots a weak thumbs up.

"And we'll be with you, okay?" Hope reaches up to tap at Carol's earpiece. "Just say the word, we'll pull you out."

There's a familiar sensation of tugging, and then - Carol opens her eyes to a whole other possibility.

In this universe, Natasha never sets foot anywhere near Vormir. In this universe, Natasha lives past 2023.

Carol watches as her alternate-universe self proposes to Natasha right after the final battle - they've waited around long enough (five years!), and there's no point in waiting around anymore, not when their friends and family and everyone they love is back to celebrate their happiness with them.

She watches the rest of their lives play out like - like scenes from a movie. They move into a small house in New York, just a stone's throw away from the rest of the Avengers, and they get married, and they have a family. A pair of twins from a shelter Natasha had helped run during the five years. She sees her children in an alternate universe grow up and learn to call her 'Mom' and Natasha 'Mama', and attends their first ballet recitals, and then their graduation, unseen. She spies on them as one of the follows her footsteps into the Air Force, and the other one follows Natasha into the re-established SHIELD.

"Carol," she hears Hope murmur softly into her earpiece. "Time's running short. We have to -"

"I know," she says shortly. Her fingers hover over the button that will bring her back into 2026, into a universe where Natasha gave her life to save the world, where she'll wake up everyday to the reality that she, in this one universe, will never see her Nat again.

She turns around - one last look, she promises herself.

And watches as alternate-her bends down slightly to press her lips to alternate-universe-Natasha's temple. It's a gesture so full of tenderness and love, and it rips open every single wound in her heart that she thought she'd buried months ago. She grits her teeth, and stabs angrily at wrist, and the scene dissolves before her eyes as she's yanked forcibly back into the present.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

New world news from Time: A Radical German Program Promised a Fresh Start to Yazidi Survivors of ISIS Captivity. But Some Women Are Still Longing for Help

When Hanan escaped from Islamic State captivity, there wasn’t much to come back to.

She and her five children had survived a year in a living nightmare. After her husband finally managed to arrange their rescue in the summer of 2015, they joined him in a dusty camp in Iraq where he lived in a tent. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) still controlled the territory they called home, and they were unsure if they could ever go back. And Hanan was unsure if she could ever escape the darkness she felt inside.

So when, in the fall of 2015, Germany offered her the promise of safety and a chance to heal from her trauma, it wasn’t a difficult decision. Accepting a place in a groundbreaking program for women and children survivors of ISIS captivity did mean leaving her husband behind in the camp, but she was told he could join her after two years. So she and her children boarded the first flight of their lives, out of Iraq and away from their tight-knit community, in search of safety and treatment for what still haunted them.

Hanan, now 34, was one of 1,100 women and children brought to Germany in an unprecedented effort to aid those most affected by ISIS’s systematic campaign to kill and enslave the ancient Yazidi religious minority. (TIME is identifying Hanan by her first name only for her safety.) Launched by the German state of Baden Württemberg in October 2014, the program aimed to help survivors of captivity receive much-needed mental-health treatment and support. In Iraq, there had been a rash of suicides among the heavily-traumatized survivors, who had minimal access to mental-health care and faced an uncertain future. In Germany, far from the site of their suffering, state officials hoped the women and children could find healing and a fresh start.

But for Hanan, those promises remain unfulfilled. German officials never granted visas to any of the women’s husbands, leaving families, including Hanan’s, indefinitely torn apart. Like most of the women, she’s not undergoing promised trauma therapy. She often thinks about killing herself. The only thing stopping her, she says, is her children.

Not all the women are desperate. Some are thriving in Germany, and others have become global advocates for their community, like 2018 Nobel Prize winner Nadia Murad. She is the most prominent face of a program that was so ambitious and well-intentioned it inspired other countries, like Canada and France, to follow suit. But Hanan’s experience illustrates how parts of the program failed to live up to their full potential, and shows how difficult it is for refugees to gain access to mental health services, even in a program designed for just that. Michael Blume, the state official who led the program, sees it as a “great success” overall. But he is troubled by the state’s failure to bring the women’s husbands to Germany. “A great humanitarian program should not be sabotaged by bureaucracy,” he says. “But that’s what is taking place.”

Before she left Iraq, Hanan said she was given a piece of paper with information about what awaited her in Germany. “I wish I could find that paper now,” she says, “because the promises they gave us, they didn’t keep all of them.”

By the time ISIS swept across Sinjar, the area in northwest Iraq that is home to most of the world’s Yazidis, Hanan had already endured more than her share of hardship. Her parents were murdered in front of her when she was six. She and her two siblings went to live with their grandfather and his wife, where they were beaten, starved, and forced to work instead of going to school. Her baby sister died soon after.

In her early twenties, she escaped the torturous conditions at home by marrying Hadi. It was the first good fortune of her life, she says; they loved each other. Over the course of about seven years, they had four daughters and then a son, who was just a few months old in August 2014, when ISIS captured Sinjar and unleashed its systematic campaign to wipe out the Yazidis.

In conquered Yazidi towns, fighters executed the men and elderly women. Boys were sent off for indoctrination and forced military training. Women and girls were sold into slavery, traded among fighters like property and repeatedly raped. Hanan and her children were among more than 6,000 people kidnapped. Hadi, who was working as a laborer in a city beyond the reach of ISIS when their village was captured, was frantic when he learned his family was gone.

Within days, President Barack Obama launched U.S. airstrikes on ISIS militants, and U.S. forces delivered food and water to besieged Yazidis trapped on Sinjar mountain. In the following months, as Yazidi women and children started emerging from captivity—some escaped, while others were rescued by a secret network of activists—with tales of horror, Yazidis pleaded for more international action. Former captives were severely traumatized. Mental-health care in Iraq was limited. And because the Yazidi faith doesn’t accept converts or marriage outside the religion, the women raped and forcibly converted to Islam by ISIS members feared they were no longer welcome in the community.

In Germany, home to the largest Yazidi population outside of Iraq, officials in Baden Württemberg decided to act. In October 2014, state premier Winfried Kretschmann decided to issue 1,000 humanitarian visas and earmark €95 million ($107 million) for what became known as the Special Quota Project for Especially Vulnerable Women and Children from Northern Iraq. The state recruited 21 cities and towns across the southwestern state to host the refugees, agreeing to pay municipalities €42,000 ($50,000) per person for housing and other costs, while the state would cover the cost of their healthcare. Two other states agreed to take an additional 100 people.

Tori Ferenc—INSTITUTE for TIMESaber, six, and Sheelan, eight, playing on the bed.

Program officials interviewed survivors of ISIS captivity in Iraq, selecting those with medical or psychological disorders as a result of their captivity who could benefit from treatment in Germany. The project was not restricted to Yazidis, and a small number of Christians and Muslims also were chosen. That was when the officials told each woman that after two years, immediate family members like husbands could apply for a visa under German rules for family unification.

Read More: He Helped Iraq’s Most Famous Refugee Escape ISIS. Now He’s the One Who Needs Help

The program was groundbreaking. No German state had ever administered its own humanitarian admission program. And instead of waiting for asylum-seekers to make dangerous journeys across the Mediterranean, officials were seeking out the most vulnerable and bringing them to safety. The first plane arrived in March 2015. The last of the flights—including the one carrying Hanan—landed in January 2016.

Hanan, along with 111 others, was sent to a pleasant hilltop town of about 25,000 people at the edge of the Black Forest. (Officials asked that the town not be named to protect the survivors, whom they fear could be targeted by ISIS members.) For the first three years, she lived with about half of the group in an old hospital in the town center that had been converted into a communal residence.

Hanan and her five children occupied two rooms off a central corridor—one they used for sleeping, and the other, with a sink along one wall and a worn leather sofa along another, as a living room. They shared a bathroom and a kitchen with a large family next door.

“The neighbors are worse than Daesh,” she joked with a grimace, using a pejorative name for ISIS. It was May 2017, more than a year after her arrival. She sat on the floor to breastfeed her youngest child, Saber. At three, he was small for his age, but Hanan was small too. Her long dark hair was pulled back, and she wore a long blue skirt and a dark hoodie. Her next youngest, Sheelan, climbed into a wardrobe in the corner, peeking out from underneath thick black bangs. Haneya, her oldest at 10, and Hanadi and Berivan, eight and seven, were fighting with the neighbor’s children, their shrieks competing with the Kurdish music videos blaring from the television. Hanan yelled at them to stop.

Caring for her five children alone was wearing Hanan out. She was often sick, but found it difficult to go to the doctor because she didn’t have help with childcare. She complained about painful and unresolved gynecological issues from being repeatedly raped. She wanted to go back to the doctor, but she relied on social workers to make appointments for her and said they were blowing off her requests. And most days, she suffered debilitating headaches.

Tori Ferenc—INSTITUTE for TIMEBerivan, Hanan’s 10-year-old daughter, at home.

A trauma therapist came once a week to the shelter for a group session with the women, but Hanan usually wasn’t able to attend because of the children. And she didn’t want to talk about her experiences in front of the other women. When she slept, nightmares came. One night she dreamed she was back in captivity and an ISIS fighter was trying to take her oldest daughter, Haneya. Hanan woke herself and the children up with her screams. The older girls talked about their time in captivity often and sometimes had nightmares too. “They’re not like normal kids,” Hanan said. “When it’s nighttime, they ask me, ‘Mama, do you think Daesh is going to come to get us?’”

A year earlier, around six months after her arrival, that nightmare had become reality. She was out shopping for food when she spotted him. He had trimmed his hair and beard, and exchanged his tunic for a blue T-shirt. But it was him—the ISIS member who had been her captor for a month.

She stared, frozen in place. He saw her, too: His eyes widened in recognition and surprise. Panic shot through her and then her feet were moving, carrying her out of the store and around the corner. By the time she went to the police, he was gone. She said they treated her as if she had mistaken a random refugee for her former tormenter. But she knew what she saw. “How could I forget the face of the man who raped me?”

Germany was supposed to be a sanctuary. Now, inside the old hospital walls was the only place Hanan felt safe. She rarely ventured out, remembering threats from her captors that they would find her if she ran away.

She worried the man she’d spotted might come back to harm them. The only identifying information she could give police was his nom de guerre. And though police were stationed outside the shelter for some time after she made the report, Markus Burger, head of the department for refugees and resettlement in the town’s social office, said his office eventually received a report stating there was no direct threat. The police referred questions about the incident to the federal public prosecutor, and a spokesman for the prosecutor said the office was aware of the incident but could not comment further. At least one other woman in the program saw her own captor in Germany, and she later returned to Iraq because she no longer felt safe.

Hanan couldn’t understand why the police couldn’t find the man. She began to see threats anywhere she went. Muslim people speaking Arabic terrified her. Once at a park with her children, a bearded man on a bench called out to her. Though she had never seen him before, she was afraid. She gathered the children and rushed back to the shelter.

Tori Ferenc—INSTITUTE for TIMEOranges in Hanan’s kitchen.

Yazidis are no strangers to trauma. The religious minority has endured centuries of persecution and attacks, from the Ottoman empire to Saddam Hussein to Al Qaeda. Jan Kizilhan, an expert in psychotraumatology and transcultural psychotherapy who was the program’s chief psychologist, was born to a Yazidi family in Turkey and immigrated to Germany as a child. Survivors of ISIS captivity are dealing not only with their own individual trauma from the violence and family separation they endured, he said, but also the historical trauma borne by their people, and the collective trauma from ISIS’s attempted genocide.

But after the women arrived in Germany as part of the program, trauma therapy wasn’t a top priority. At first, most of the refugees were focused on adjusting to life in Germany, said Kizilhan. They were also following the situation back home, where a multinational coalition was wrestling territory away from ISIS. With every victory, Yazidi families waited for news of their missing relatives, hoping they would not be among the bodies discovered in mass graves. Most had family members in camps, and others still in captivity. They weren’t ready to work through past trauma in therapy, because it was still part of their present.

There was another, more basic, obstacle to treatment: Most of the women were unfamiliar with the concept of psychotherapy. “To even help them understand why they would need this or how it would help, it takes time,” said Kizilhan. In many Middle Eastern cultures, including the Yazidi community, psychological trauma is often expressed somatically, he explained — many women complained of a burning liver, headaches, or stomachaches when the root was a psychological, rather than physiological, problem.

In 2017 and 2018, Tübingen University Hospital and the University of Freiburg, which were also involved in psychotherapeutic care for program participants, carried out surveys of 116 of the women in the program. Ninety-three percent of those surveyed fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder during the first survey, and the number remained the same a year later. That makes the fact that just 40% of the women have received trauma therapy, years after their arrival, striking.

But Kizilhan insists the figure does not represent a failure. Some women simply don’t want therapy, he says, and it can’t be forced. He expects that an additional third of the women will be ready for therapy in the coming years. “And then we will be there to help them,” he says. “Each person is individual, different, and needs different timing.” The state decided to cover the cost of the womens’ healthcare indefinitely—initial plans were to foot the bill for three years—after it spent only €60 million ($71 million) of the allocated €95 million ($113 million) on the program.

Kizilhan acknowledges the challenges, including finding enough therapists and translators to work with the women. Kizilhan and Blume, who led the Special Quota project, say the program was an emergency intervention, and that a more long-term solution is building capacity for mental health care in Iraq. The state of Baden Württemberg has put resources toward that, too—donating €1.3 million ($1.5 million) to help establish the first master’s program for psychotherapy in Iraq, started by Kizilhan at the University of Duhok in 2017.

Kizilhan and Blume say the program in Germany has been successful despite the challenges. In the Tübingen University study, 91% of the women surveyed said they were satisfied to be in Germany, and 85% said they were satisfied with the program. When asked if they were satisfied with the psychosocial care, the number who said yes dropped to 72%. Hanan was among those who found it lacking.

Her struggle to access medical care and therapy were two of the ways she felt let down by the program. For her first three years in Germany, Hanan received minimal therapy, even though she wanted it. She rarely attended the group sessions, both because she found them unhelpful and because of the ongoing childcare issues. She said she was not offered individual sessions. Burger said when social workers saw some women were unhappy with group sessions, they arranged for individual therapy, and Hanan began talking with a therapist every few weeks. She said it helped a little, but she felt the same after each session.

***

On a Wednesday in July 2018, Hanan left German class early to shop for food. Before leaving home, she pulled on a fitted black blazer over her beige shirt and leggings. The clothes were new; she had recently cast aside the long, dark skirts and sweaters that she had worn ever since her escape for a more modern wardrobe. Friends had urged her to make the switch, teasing her that she dressed like she was still living under ISIS. Hanan walked to the store, passing traditional timber-frame buildings and window boxes overflowing with geraniums and petunias. She spotted a friend outside the supermarket and stopped to chat before buying chicken legs and vegetables. Managing the family’s budget alone—something she had never done in Iraq—was challenging. Sometimes she didn’t have enough money at the end of the month.

Two years on from encountering her former captor, the town was beginning to feel less threatening, though Hanan still didn’t like going out at night. She attended German language class four mornings a week. She’d never learned how to read or write as a child, so learning German was doubly hard, but she was making slow progress. She was also making a few German friends, and she’d found a way to decipher their text messages even though she couldn’t read. When she received a message, she’d paste it into the Google Translate app and press the audio button. A robotic voice would read it aloud and she’d reply via voice note.

Back at home, she put a pot of rice on the stove and began browning the chicken, preoccupied by the logistics of her upcoming trip to Iraq to visit her husband, Hadi. She’d learned through her social worker that her stipend would be paused while she was away, and Hanan wasn’t sure how she would make it through the month without the money.

It would be the second time she had to travel to see Hadi. (The women were admitted as humanitarian refugees, rather than asylum seekers, which spared them the process of applying for asylum and meant they were allowed to return to visit family in Iraq, unlike asylum holders.) Saber, now four, had spent most of his life separated from his father, and didn’t recognize him. The girls no longer even missed him. He was becoming a faraway memory.

Two and a half years had now gone by since she left Iraq, well past the two years after which Hadi had been promised he could apply for a visa. Hanan’s social worker helped her file papers related to his visa application. But whenever Hanan asked what was happening, she was given the same answer: Not yet.

What she didn’t know was that Germany’s position toward refugees had shifted. The welcoming stance the country adopted when more than a million people poured into the country seeking asylum in 2015 had hardened amid a backlash fueled by far-right anti-immigration parties. When he interviewed the women in 2015, and told them their husbands could apply for a visa after two years, Kizilhan was in line with the rules at the time. But now laws governing refugees and family unification visas were tightened. German courts even began ruling against Yazidis who requested asylum, saying it was safe for them to go back to Iraq.

To date, no husbands of women in the Special Quota Project have received visas. It’s hard to know how many are waiting: Kizilhan says he has identified 18. According to the study, 28 percent of the women surveyed had husbands in Iraq.

Read More: Syrian Women Are Embracing Their New Lives in Germany. But At What Cost?

A spokesman for the Baden Württemberg Ministry of Interior, Digitalization and Migration said that “special rules” apply to family reunifications for those granted humanitarian admission, and may only be allowed “for reasons of human rights, on humanitarian grounds or to protect political interests.” The special rules “must be considered on a case by case basis,” he said, and added the federal authorities are responsible for issuing visas, not the state.

Kizilhan said the ministry could intervene to make sure the family members are issued visas. But the political will behind the creation of the Special Quota Project has evaporated. In January, Kizilhan said he had recently met with state interior ministry officials to ask that they find a way to bring the husbands to Germany, but that they told him the change in federal law made it difficult to do so. “This is ridiculous,” Kizilhan says. “If you can take 1,100 with the special quota, you can take 18 people in one day.”

On trips back to Iraq, Kizilhan said he’s been confronted by husbands demanding answers, and is distressed that the state has not followed through. He notes that bringing the women’s immediate family to Germany would improve their psychological health—the goal of the program—by helping to reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms and easing their integration into society. Hanan often spoke of waiting for Hadi’s arrival to move into an apartment on her own. She was fearful of handling all the responsibilities of living in a new country without him. And she desperately needed help caring for the children, help she thought would be provided in the program. They’d spent a year separated from Hadi in captivity. Now, they were once again separated, once again waiting for their family to be reunited.

Tori Ferenc—INSTITUTE for TIMEHanan braiding her 11-year-old daughter Hanadi’s hair while Berivan, 10 (L) and Haneya, 13 (R) watch.

After Hanan’s visit to Iraq, months went by with no news about Hadi’s visa. They both began to despair that it would ever materialize, their frustration compounded by a dearth of information about the delay.

In the spring of 2019, after waiting three years, Hadi decided he could wait no longer. He borrowed money and set out for Germany along irregular migration routes. It took him eight months—he was detained in Greece on the way—but eventually he made it to Hanan. Their reunion, though, was far from perfect. After his arrival in Germany, the once-happy couple separated. Hanan would not discuss the details of their estrangement except to say that it took root because of their physical separation and left her distraught. He is now in a relationship with another woman and Hanan said he is not in touch with his children. His future in Germany is uncertain, too—it is unclear whether he will be permitted to stay.

Last summer Hanan moved into a light-filled two-bedroom furnished flat rented for her by the municipality in a quiet residential neighborhood. It’s decorated brightly in orange—a peach wall, tangerine dining chairs, an ochre shag carpet, and a sofa the color of carrots. While there’s a bunk bed in the kids’ room, they usually end up sleeping in Hanan’s king-size bed every night, a tangle of arms and legs. She was finally able to see a doctor to resolve her lingering gynecological health problem, although the daily headaches are still there. She’s no longer afraid of going out at night.

On a Sunday morning in January, she awoke late, groggy from hosting friends the night before. Saber, now six, and Sheelan, seven, plopped on the sofa to watch Tom and Jerry on the television as Hanan made bread in the kitchen. Squeezing small lumps off the dough, she quickly slapped each one from hand to hand, stretching it into a thin disc. In Iraq, she would have baked the loaves in an outdoor clay oven. Here, she used a small metal box oven, heated with an electric coil, placed on the countertop. She placed each loaf on top to let it brown, then baked it inside the oven before stacking the finished loaves on the windowsill.

When she was done, the children gathered at the table, scooping up fried eggs, yogurt, tahini, and cheese with the fresh bread. They chattered together in German; they rarely spoke Kurdish with one another anymore. Saber, impish and sensitive, speaks German with a near flawless accent. After breakfast, the three older girls clear the table, wash the dishes, and sweep the floor unbidden. Hanadi, now 11, and Berivan, now 10, both with round cheeks like their mother, are learning how to swim at school. Haneya, now 13, reads and translates the mail and types messages in German for her mother.

“Sometimes I look at my kids and think ‘OK, I’m all right.’ But I just feel bad,” Hanan said, lowering herself onto the sofa. “It’s a bad feeling inside of me, I don’t know how to explain it. Sometimes I want to hit myself, because of this bad feeling inside, and I don’t know how to deal with it. Many times I thought about killing myself, but then I remember my kids, that they need me.”

The situation with Hadi has her so upset she doesn’t think about ISIS anymore, Hanan said, adding that she doesn’t know what to do or where to turn. She’s spent hours crying with a Yazidi friend, another survivor, who lives nearby. That’s the closest she gets to therapy now.

After Hanan moved into the apartment, her therapy sessions ended. A few months later, social workers took her to an appointment at a new therapist’s office, but she hadn’t gone back. She said the appointment time of 7 p.m. was impossible as there was no one to watch the children at home. But she knows she needs help. “It’s too much for me,” she said. “I can’t hold all these problems alone.”

Read More: Is Germany Failing Female Refugees?

Burger, of the town’s department for refugees and resettlement, said that as more of the women moved into private apartments last year—all but 10 now live on their own—it became harder to arrange therapy sessions. Some therapists have waiting lists, and there is always the problem of timing, he said. “It’s difficult finding a time when the trauma therapist and the translator both are available, and also when someone can take care for the children, and when the German classes aren’t at the same time. But we are working on it.” He could not give a number for how many of the women in the town were undergoing therapy, saying it was constantly changing, but said therapy was available to all who wanted it. “We can only offer it,” he said. “In the end it is the decision of the women if they want to take part in the programs, and we don’t want to and can’t force anyone to take part.”

Hanan knows it was right to come to Germany. She’s better off than she would be in Iraq, where despite the territorial defeat of ISIS, most Yazidis are still displaced, and their future is uncertain. She feels safe now in Germany, and she can see bright futures for her children here.

But she can’t muster any of that hope for herself, not after losing Hadi. The darkness she had hoped to escape never went away. “Maybe I’m going to go crazy, or I’m going to kill myself. Maybe I won’t find a solution for myself except to die,” she said. “Now I’m 34, and I didn’t see any hope in my entire life. And for the future also, I don’t have any hope. Only God knows.”

—With reporting by Navin Haji Semo and Madeline Roache

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation Reporting Grants for Women’s Stories.

from Blogger https://ift.tt/3gwSQ1H

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

New top story from Time: A Radical German Program Promised a Fresh Start to Yazidi Survivors of ISIS Captivity. But Some Women Are Still Longing for Help

When Hanan escaped from Islamic State captivity, there wasn’t much to come back to.

She and her five children had survived a year in a living nightmare. After her husband finally managed to arrange their rescue in the summer of 2015, they joined him in a dusty camp in Iraq where he lived in a tent. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) still controlled the territory they called home, and they were unsure if they could ever go back. And Hanan was unsure if she could ever escape the darkness she felt inside.

So when, in the fall of 2015, Germany offered her the promise of safety and a chance to heal from her trauma, it wasn’t a difficult decision. Accepting a place in a groundbreaking program for women and children survivors of ISIS captivity did mean leaving her husband behind in the camp, but she was told he could join her after two years. So she and her children boarded the first flight of their lives, out of Iraq and away from their tight-knit community, in search of safety and treatment for what still haunted them.

Hanan, now 34, was one of 1,100 women and children brought to Germany in an unprecedented effort to aid those most affected by ISIS’s systematic campaign to kill and enslave the ancient Yazidi religious minority. (TIME is identifying Hanan by her first name only for her safety.) Launched by the German state of Baden Württemberg in October 2014, the program aimed to help survivors of captivity receive much-needed mental-health treatment and support. In Iraq, there had been a rash of suicides among the heavily-traumatized survivors, who had minimal access to mental-health care and faced an uncertain future. In Germany, far from the site of their suffering, state officials hoped the women and children could find healing and a fresh start.

But for Hanan, those promises remain unfulfilled. German officials never granted visas to any of the women’s husbands, leaving families, including Hanan’s, indefinitely torn apart. Like most of the women, she’s not undergoing promised trauma therapy. She often thinks about killing herself. The only thing stopping her, she says, is her children.

Not all the women are desperate. Some are thriving in Germany, and others have become global advocates for their community, like 2018 Nobel Prize winner Nadia Murad. She is the most prominent face of a program that was so ambitious and well-intentioned it inspired other countries, like Canada and France, to follow suit. But Hanan’s experience illustrates how parts of the program failed to live up to their full potential, and shows how difficult it is for refugees to gain access to mental health services, even in a program designed for just that. Michael Blume, the state official who led the program, sees it as a “great success” overall. But he is troubled by the state’s failure to bring the women’s husbands to Germany. “A great humanitarian program should not be sabotaged by bureaucracy,” he says. “But that’s what is taking place.”

Before she left Iraq, Hanan said she was given a piece of paper with information about what awaited her in Germany. “I wish I could find that paper now,” she says, “because the promises they gave us, they didn’t keep all of them.”

By the time ISIS swept across Sinjar, the area in northwest Iraq that is home to most of the world’s Yazidis, Hanan had already endured more than her share of hardship. Her parents were murdered in front of her when she was six. She and her two siblings went to live with their grandfather and his wife, where they were beaten, starved, and forced to work instead of going to school. Her baby sister died soon after.

In her early twenties, she escaped the torturous conditions at home by marrying Hadi. It was the first good fortune of her life, she says; they loved each other. Over the course of about seven years, they had four daughters and then a son, who was just a few months old in August 2014, when ISIS captured Sinjar and unleashed its systematic campaign to wipe out the Yazidis.

In conquered Yazidi towns, fighters executed the men and elderly women. Boys were sent off for indoctrination and forced military training. Women and girls were sold into slavery, traded among fighters like property and repeatedly raped. Hanan and her children were among more than 6,000 people kidnapped. Hadi, who was working as a laborer in a city beyond the reach of ISIS when their village was captured, was frantic when he learned his family was gone.

Within days, President Barack Obama launched U.S. airstrikes on ISIS militants, and U.S. forces delivered food and water to besieged Yazidis trapped on Sinjar mountain. In the following months, as Yazidi women and children started emerging from captivity—some escaped, while others were rescued by a secret network of activists—with tales of horror, Yazidis pleaded for more international action. Former captives were severely traumatized. Mental-health care in Iraq was limited. And because the Yazidi faith doesn’t accept converts or marriage outside the religion, the women raped and forcibly converted to Islam by ISIS members feared they were no longer welcome in the community.

In Germany, home to the largest Yazidi population outside of Iraq, officials in Baden Württemberg decided to act. In October 2014, state premier Winfried Kretschmann decided to issue 1,000 humanitarian visas and earmark €95 million ($107 million) for what became known as the Special Quota Project for Especially Vulnerable Women and Children from Northern Iraq. The state recruited 21 cities and towns across the southwestern state to host the refugees, agreeing to pay municipalities €42,000 ($50,000) per person for housing and other costs, while the state would cover the cost of their healthcare. Two other states agreed to take an additional 100 people.

Tori Ferenc—INSTITUTE for TIMESaber, six, and Sheelan, eight, playing on the bed.

Program officials interviewed survivors of ISIS captivity in Iraq, selecting those with medical or psychological disorders as a result of their captivity who could benefit from treatment in Germany. The project was not restricted to Yazidis, and a small number of Christians and Muslims also were chosen. That was when the officials told each woman that after two years, immediate family members like husbands could apply for a visa under German rules for family unification.

Read More: He Helped Iraq’s Most Famous Refugee Escape ISIS. Now He’s the One Who Needs Help

The program was groundbreaking. No German state had ever administered its own humanitarian admission program. And instead of waiting for asylum-seekers to make dangerous journeys across the Mediterranean, officials were seeking out the most vulnerable and bringing them to safety. The first plane arrived in March 2015. The last of the flights—including the one carrying Hanan—landed in January 2016.