#soviet invasion of germany

Text

Poet Yevgeniy Dolmatovsky poses with a bronze bust of Adolf Hitler in Berlin, May 1945

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland. Hitler was already conducting an invasion from the west and Stalin joined him by invading Poland from the east.

This double invasion was part of the agreement drawn up by the foreign ministers of Nazi Germany and the USSR less than a month before.

As a result of the double invasion, the two worst people in the 20th century got to divide Eastern Europe between themselves.

Of course dictators do not necessarily stick to agreements with each other. On 22 June 1941 Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact became null and void.

History reverberates – more so in Eastern Europe than in most places.

What the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact tells us about today’s war in Ukraine

Here's a vid made by Poland's Ministry of Foreign Affairs about a year ago.

youtube

#poland#polska#soviet invasion of poland#ussr#russian imperialism#russia#molotov-ribbentrop pact#vyacheslav molotov#joseph stalin#joachim von ribbentrop#adolph hitler#nazi germany#invasion of ukraine#vladimir putin#вячеслав молотов#иосиф сталин#пакт молотова-риббентропа#ссср#россия#владимир путин#путин хуйло#русский империализм#военные преступления#вторгнення оркостану в україну#деокупація#слава україні!#героям слава!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, two colossal pavilions faced each other down. One was Hitler’s Germany, crowned with a Nazi eagle. The other was Stalin’s Soviet Union, crowned with a statue of a worker and a peasant holding hands. It was a symbolic clash at a moment when right and left were fighting to the death in Spain. But somewhere inside the Soviet pavilion, among all the socialist realism, were drawings of fabulous beasts and flowers filled with a raw folkloric magic. They subverted the age of the dictators with nothing less than a triumph of the human imagination over terror and mass death.

These sublime creations were the work of a Ukrainian artist, Maria Prymachenko, who has once again become a symbol of survival in the midst of a dictator’s war. Prymachenko, who died in 1997, is the best-loved artist of the besieged country, a national symbol whose work has appeared on its postage stamps, and her likeness on its money. Ukrainian astronomer Klim Churyumov even named a planet after her.

When the Museum of Local History in Ivankiv caught fire under Russian bombardment, a Ukrainian man risked his life to rescue 25 works by her. But Prymachenko’s entire life’s work is now under much greater threat. As Kyiv endures heavy attacks, 650 paintings and drawings by the artist held in the National Folk Decorative Art Museum are at risk, along with everything and everyone in the capital.

‘A murderous intruder in Eden’ … another of Prymachenko’s grotesque creatures. Photograph: Prymachenko Foundation

It’s said that, when some of Prymachenko’s paintings were shown in Paris in 1937, her brilliance was hailed by Picasso, who said: “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian.” It would make artistic sense. For this young peasant, who never had a lesson in her life, was unleashing monsters and collating fables that chimed with the work of Picasso, and his friends the surrealists. While the dictatorships duked it out architecturally at that International Exhibition, Picasso unveiled Guernica at the Spanish pavilion, using the imagery of the bullfight to capture war’s horrors. Prymachenko, too, dredged up primal myths to tackle the terrifying experiences of Ukrainians.

Her pictures from the 1930s are savage slices of farmyard vitality. In one of them, a beautiful peacock-like bird with yellow body and blue wings perches on the back of a brown, crawling creature and regurgitates food into its mouth. Why is the glorious bird feeding this flightless monster? Is it an act of mercy – or a product of grotesque delusion? In another drawing, an equally colourful bird appears to have its own young in its mouth. Carrying it tenderly, you might think, but only if you know nothing of the history of Ukraine.

At first sight, Prymachenko might seem just colourful, decorative and “naive”, a folkloric artist with a strong sense of pattern. Certainly, her later post-1945 works are brighter, more formal and relaxing. But there is a much darker undertow to her earlier creations. For Prymachenko became an artist in the decade when Stalin set out to destroy Ukraine’s peasants. Rural people starved to death in their millions in the famine he consciously inflicted on Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933.

Had she been an ‘intellectual’, she could have ended up in a gulag or worse …Prymachenko.

Initially, food supplies failed because of the sudden, ruthless attempt to “collectivise” agriculture. Peasants were no longer allowed to farm for themselves but were made to join collectives in a draconian policy that was meant to provide food for a new urban proletariat. Ukraine was, and is, a great grain-growing country but the shock of collectivisation threw agriculture into chaos. The Holodomor, as this terror-famine is now called, is widely seen as genocide: Stalin knew what was happening and yet doubled down, denying relief, having peasants arrested or worse if they begged in cities or sought state aid. In a chilling presage of Putin’s own logic and arguments, this cruelty was driven by the ludicrous notion that the hungry were in fact Ukrainian nationalists trying to undermine Soviet rule.

“It seems reasonable,” writes historian Timothy Snyder in his indispensable book Bloodlands, “to propose a figure of approximately 3.3 million deaths by starvation and hunger-related disease in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-1933”. These were not pretty deaths and they took place all around Prymachenko in her village of Bolotnya. Some people were driven to cannibalism before they died. The corpses of the starved in turn became food.

Born in 1908, Prymachenko was in her early 20s when she witnessed this vision of hell on Earth – and survived it to become an artist. But the fear did not end when the famine did. Just as her work was sent to Paris in 1937, Stalin’s Great Terror was raging. It is often pictured as a butchery of urban intellectuals and politicians – but it came to the Ukrainian countryside, too.

So it would take a very complacent eye not to see the disturbing side of Prymachenko’s early art. The bird in its parent’s mouth, the peacock feeding a brute. Maybe there is also survivor guilt, and a feeling of alienation from a destroyed habitat, in such images of strange misbegotten creatures lost in a nature they can’t work and don’t comprehend. One of her fantastic beasts appears blind, its toothy mouth open in a sad lamentation, as it stumbles through a garden on four numbed clodhopping feet. A serpent and a many-headed hydra also appear among the flowers, like deceptively beautiful, yet murderous intruders in Eden. In another of these mid-1930s works, a glorious bird rears back in fear as a smaller one perches on its breast, beak open.

There’s nothing decorative or reassuring about the images that got this brave artist noticed. Far from innocently reviving traditional folk art, her lonely or murderous monsters exist in a nature poisoned by violence. Yet she got away with it – and was even officially promoted right in the middle of Stalin’s Terror, when millions were being killed on the merest suspicion of independent thought. Perhaps this was because even paranoid Stalinists didn’t think a peasant woman posed a threat.

Her spirit survives … a rally for peace in San Francisco, recreating a work by Prymachenko called A Dove Has Spread Her Wings and Asks for Peace. Photograph: John G Mabanglo/EPA

Prymachenko remembered that, as a child, she was one day tending animals when she “began to draw real and imaginary flowers with a stick on the sand”. It’s an image that recurs in folk art – this was also how the great medieval painter Giotto started. But it was Prymachenko’s embroidery, a skill passed on by her mother, that first got her noticed and invited to participate in an art workshop in Kyiv. Such origins would inevitably have meant being patronisingly classed by the Soviet system as a peasant artist. An “intellectual” who produced such work could have ended up in the gulag or worse.

Yet, to see the sheer miracle of her achievement, you must also set Prymachenko in her time as well as her place. The Soviet Union in the 1930s was relentlessly crushing imagination as Stalin imposed absolute conformity. The Ukrainian writer Mikhail Bulgakov couldn’t get his surreal fantasies published, even though, in a tyrannical whim, Stalin read them himself and spared the writer’s life. But the apparent rustic naivety of Prymackenko’s work let her create mysterious, insidiously macabre art that had more in common with surrealism than socialist realism.

Then, incredibly, life in Ukraine got worse. Prymachenko had found images to answer famine but she fell silent in the second world war, when Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union made Ukraine one of the first places Jews were murdered en masse. In September 1941, 33,771 Kyiv Jews were shot and their bodies tossed into a ravine outside their city. Prymachenko was working on a collective farm and had no colours to paint.

In the 1960s, she was the subject of a liberating revival, her folk designs helping to seed a new Ukrainian consciousness. There’s an almost hippy quality to her 60s art. You can see how it appealed to a younger audience, keen to reconnect with their Ukrainian identity.

The country has other artists to be proud of, not least Kazimir Malevich, a titan of the avant garde famous for Black Square, the first time a painting wasn’t a painting of something. Yet you can see why Prymachenko is so loved. Her art, with its rustic roots, expresses the hope and pride of a nation. But the past she evokes is no innocent age of happy rural harmony. What she would make of Putin’s terror one can only guess and fear.

#studyblr#history#military history#art#art history#ukrainian art#communism#agriculture#collectivization#soviet famine of 1930-1933#holodomor#exposition internationale des arts et techniques dans la vie moderne#spanish civil war#bombing of guernica#great purge#ww2#holocaust#babi yar massacre#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#ussr#ukraine#russia#germany#nazi germany#spain#maria prymachenko#klim churyumov#pablo picasso#josef stalin

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

"Warszawskie dzieci" or "Warsaw Children" is a song about the bravery of the young Polish children who faced the horrors of war. From August 1, 1944, these children, alongside the adult resistance fighters, fearlessly defended their beloved city during the Warsaw Uprising from Nazi invasion and occupation.

#youtube#europe#poland#history#ww2#wwii#stop germany#stop ussr#stop nazi gerrmany#war#conflict#stop invasion#stop war#stop soviets#stop nazis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird Soviet Invasion Dream

Dream begins with Parents reminiscing of time I burnt a man alive, something happens and time skip to me being sent to a military base for training. The military school is kinda academy style. Class begins and teacher asks the various students about their school plans. One student talks about their school wide random date show for the festival. Other kid comments about how he wouldn't attend even it was a date with his dog. Another kid calls him a furry and class is asked to raise hands if they think he's a furry. Everyone does except kid. I comment an apology but say I have to raise my hand. I’m asked to read a poem aloud to the class which is for some reason is in English and German. I struggle a bit but ultimately show impressive German skills. Teacher/General who is famous hero from the last war comments begins revealing the truth that she started out the war as an anti-war peace protester. Throughout this whole class I’ve been having involuntary jittering, teacher comments on it, I’m a bit sick and I’m sent out to rest for a bit. As I'm outside one of the entrances to the school/military base, a poorly trained spy approaches me who for some reason has an English accent. He seems desperate to get in, he notices I’m sick and offers to not shoot me if I let him through. He appears from his demeanor to want me to spread my sickness within the base. I refuse and he asks again, this repeats twice. I threaten to call for help. He comments how no one will hear me from this distance. I yell multiple times for help, someone arrives. Arguing continues for short while as it becomes clear why he's so desperate to get in due to sound of yelling and troop movements in n the background. We both desperately run inside to escape troops. Somehow troops are quickly onto us and inside the building despite seemingly being a great distance away a few moments ago. I attempt to climb the mesh wire fence that lines the walls as a means to escape. The Soviet Russian troops shoot me and a number of fleeing military academy students. I fall into some sort of moat or water and see corpse of fellow student. I somehow get up and escape school for nearby woods. Students are fleeing the academy in all directions generally, I make my way towards the woods but come upon a residential neighborhood. I can hear more Soviet troops movements fighting in the nearby urban area. I remember an old trail that will lead deep into woods, I decide to flee there and hide until conflict is over, though I am concerned others could have the same idea. I begin waking up and still partially asleep self decides to save dream video game style and load it later because it was super cool, as I reach the mostly awake point I realize I can't load a dream, I attempt to fall fully back asleep nevertheless and reload it, I obviously fail, and so I began writing this.

0 notes

Text

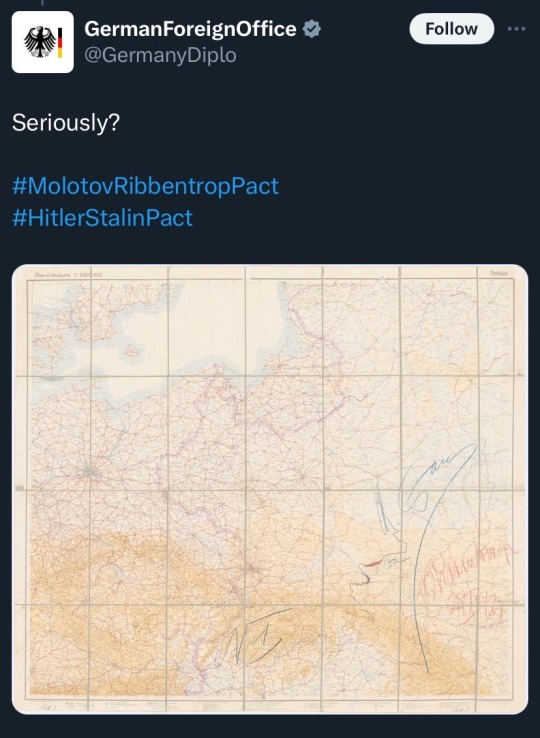

Russia trying to claim the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland was actually a humanitarian operation meant to stop a made-up genocide, only for Germany to come out with a map presented to fucking Hitler of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which effectively set the stage for the combined invasion of the country and its partition between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, has to be the best destruction of modern state propaga I’ve ever seen!

436 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any good reads on the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact? I don’t trust wikipedia on this because all sources are from anglo-american sources and one is from radio free europe lol

I'm bad at giving reading references, but in brief: the USSR first approached each of the western powers and attempted to form an anti-Nazi alliance, but none of them aggreed, because they wanted the Nazis to weaken or outright destroy the USSR, and kill two birds with one stone (hence the 'appeasement' period); all the other powers had their own treaties with Germany that were generally equivalent wrt non-aggression; and the USSR eventually formed its own non-aggression treaty with Germany *because* they and everyone else knew Germany was planning to invade and genocide the USSR, so they needed as much time as possible to prepare their defences (for their piece, the Nazis would expect increased war preparations on the part of the USSR to actually *benefit* their invasion, as they hoped that the USSR would dedicate all its forces to its western border, and have them decisively encircled and destroyed all at once with the initial, speedy push - the USSR showed great restraint and forced Germany instead to commit to a lengthy, protracted invasion to fight the bulk of the Soviet army in its own depth). The Soviet occupation of Poland, while having its obvious negative aspects, also prevented further Nazi advance, and prevented the Nazi occupation of half of Poland, during which time Polish jews were able to be evacuated - and lest we forget that Poland itself was an extremely reactionary, antisemitic state at the time already. The USSR only occupied Polish territory once it became clear that the Nazis would not stop at the part of Poland designated to be in 'their sphere', and would continue to occupy the part that was technically protected in the treaty by being designated as part of the 'Soviet sphere'. The idea of a 'Nazi-Soviet alliance' that carved up Poland is a key piece of ideological justification for the equivocation of fascism and communism, and, along with the 'double genocide' myth, was perpetrated directly by the Nazis themselves.

504 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding your post on Stalin and Lenin, I want to ask in good faith: how can honest Communists, in good conscience, acknowledge the material harm and the death tolls of the deportations of the Crimean Tatars, Soviet Koreans, and Chechens + Ingush carried out by Stalin's administration?

I at least understand why Marxist-Leninists dispute calling the Holodomor and Kazakh famines genocides, on the grounds that they came about as a mix of failed policy, bad weather, and unintended consequences.

However, while Stalin's influence on the Famines is debatable, allowing the deportations to be carried out (which DO constitute a genocide) must certainly fall on his head. This is doubly so because Lavrentiy Beria - the principal architect of the Crimean Tatar and Chechen deportations - was a close ally of Stalin.

A big reason I ask this is because I frequently see other communists either gloss over the material harm of these deportations, or treat them as a regrettable footnote in an otherwise proud career. I find both approaches problematic, because I do not see them as an honest assessment of Stalin's wrongdoing with regards to ethnic minorities within the Soviet Union.

I thank you for your time, and I look forward to reading your assessment, should you chose to answer it. Have a good day.

[context]

I'll get to the ask itself in a moment, but first I want to point out how you're doing exactly what the post you're replying to is criticizing, how every mistake and imperfect policy of the USSR between 1924 and 1953 is scapegoated to Stalin. You're ignoring both the very important structures of democracy and accountability within the party as well as in the administration of the state. He wasn't a dictator and policy was not a direct extension of the man's thoughts. The party leadership was a collective organ made up of at least a dozen people, of which Stalin was simply the chairman, with the same vote as everyone else. And every single one of these members were beholden to democratic recall at any time.

Let's start on the common ground, we understand that the famine which struck Ukraine, southern Russia and western Kazakhstan in the early 1930s has a context of cyclical famines, grain hoarding, rushed collectivization, and bad weather. There has been a strong effort on the part of capitalist powers to both exaggerate the effects of the famine and to place it all with intent to exterminate Ukranians specifically. The policy of collectivization and antagonism towards the grain-hoarding rich peasants was one approved by and carried out by hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions. We can debate the degree of maliciousness, the severity of its effects, etc. But what is indisputable once you know just a little of how the USSR worked, to pretend that it could all be carried out by Stalin's sole will is absurd.

And what is the context of the deportations? The fascist invasion of the USSR. This is an extraordinary circumstance, every facet of the USSR was being attacked and threatened with sabotage. It wasn't even the first time they had had to deal with internal sabotage, like it was revealed in the trials following the assassination of Kirov. Throughout the 30s, Nazi Germany's strongarm diplomacy was practically enabled by their ability to create fifth columns, to instigate conflict and to infiltrate. They were in the process of setting up a coup d'etat in Lithuania when, with only a week to spare, it was voted that Lithuania would join the USSR. So, the fear that, as the front advanced, the nazis would do everything in their power to turn the tapestry of nationalities close to the front against the USSR, wasn't only unfounded, it was certain. Fascists are also quite famously brutal against the minorities in the territories they conquered. Their modus operandi whenever they captured a population was to kill any elected leaders and start to instigate anti-semitism.

This was the rationale that drove the policy of resettlement. It was a rushed wartime decision, such was the context, and people definitely died unnecessarily in transport. They decided that the negative consequences of resettlement outweighed the risk of sabotage, destroyed supply lines, and of a completely certain brutal destiny for these minorities if the front advanced past them. It was not a genocide, and it had nothing to do with whatever personal relationship you think Stalin had with Beria. (As a tangent, in this interview, Stalin's bodyguard said that Beria was "neither his [Stalin's] right hand man or left hand man"). I reiterate though, the personal relationships of one man did not dictate the policy decided on democratically by the CPSU.

I don't see the problem in understanding the context of these decisions and understanding the rationale behind them without kneejerking into discounting Stalin's competency. It's very easy to criticize a decision with 80 years of hindsight, without the pressure of the largest land invasion ever carried out advancing steadily. You can't understand the policies of a country containing hundreds of millions of people and hundreds of nationalities through the lens of a single man's personal failings, especially in wartime. Admitting these mistakes, but understanding the context in which they were made, is the only way to learn from other attempts at developing socialism. What is not productive is to insist on pinning every mistake, every unnecessary pain, every inefficiency, as the wrongdoings of a single man. It's dishonest to both the past, and to how communists organize today.

#ask#anon#seriousposting#re-reading this and I want to make my tone clear#I'm not trying to be aggressive towards you anon#I'm just trying to use clear language and be direct about this topic#I really appreciate the question and you clear efforts to be level-headed about this

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

German soldiers surrender to the Red Army, East Prussia.

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the bad old days of communism, Checkpoint Charlie was a crossing point between West Berlin and Soviet occupied East Berlin. It was one of the few openings in the Berlin Wall. However East Germans were not allowed to use these portals because their Soviet puppet government feared losing its population to the West.

Nowadays at the site of the old checkpoint is a museum and some souvenir shops. For this holiday season there is also a Christmas tree decorated with Ukrainian flags. It acts as a reminder that the threat of Russian imperialism is not just something in the past.

Vladimir Putin was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet secret police (the KGB). In the 1980s he was stationed in East Germany. So in addition to showing support for Ukraine, this pro-Ukraine Christmas tree could be seen as a dig at Putin.

The flag of Ukraine is distinctive and simple. If you wish to add one or more to your own holiday decorations, the color codes can be found here.

#berlin#christmas tree#checkpoint charlie#berlin wall#the cold war#east germany#flag of ukraine#weihnachtsbaum#berliner mauer#ddr#soviet union#ussr#kgb#vladimir putin#russia#invasion of ukraine#владимир путин#россия#ссср#вторгнення оркостану в україну#флаг#путин хуйло#руки прочь от украины!#україна переможе#слава україні!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When most Americans think of fascism, they picture a Hitlerian hellscape of dramatic action: police raids, violent coups, mass executions. Indeed, such was the savagery of Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and Vichy France. But what many people don’t appreciate about tyranny is its “banality,” Timothy Snyder tells me. “We don’t imagine how a regime change is going to be at the dinner table. The regime change is going to be on the sidewalk. It’s going to be in your whole life.”

Snyder, a Yale history professor and leading scholar of Soviet Russia, was patching into Zoom from a hotel room in Kyiv, where the specter of authoritarianism looms large as Ukraine remains steeped in a yearslong military siege by Vladimir Putin. It was late at night and he was still winding down from, and gearing up for, a packed schedule—from launching an institution dedicated to the documentation of the war, to fundraising for robotic-demining development, to organizing a conference for a new Ukrainian history project. “I’ve had kind of a long day and a long week, and if this were going to be my sartorial first appearance in Vanity Fair, I would really want it to go otherwise,” he joked.

But the rest of our conversation was no laughing matter. It largely centered, to little surprise, on Donald Trump and how the former president has put America on a glide path to fascism. Too many commentators were late to realize this. Snyder, however, has been sounding the alarm since the dawn of Trumpism itself, invoking the cautionary tales of fascist history in his 2017 book, On Tyranny, and in The Road to Unfreedom the year after. It’s been six years since the latter, and Snyder is now out with a new book, On Freedom, a personal and philosophical attempt to flip the valence of America’s most lauded—and loaded—word. “We Americans tend to think that freedom is a matter of things being cleared away, and that capitalism does that work for us. It is a trap to believe in this,” he writes. “Freedom is not an absence but a presence, a life in which we choose multiple commitments and realize combinations of them in the world.”

In an interview with Vanity Fair, which has been edited for length and clarity, Snyder unpacks America’s “strongman fantasy,” encourages Democrats to reclaim the concept of freedom, and critiques journalists for pushing a “war fatigue” narrative about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “There’s just something so odd about Americans being tired of this war. We can get bored of it or whatever, but how can we be tired?” he asks. “We’re not doing a damn thing.”

Vanity Fair: The things we associate with freedom—free speech, religious liberty—have been co-opted by the Republican Party. Do you think you could walk me through how that happened historically and how Democrats could take that word back?

Timothy Snyder: Yeah. I think the way it happened historically is actually quite dark there. There’s an innocent way of talking about this, which is to say, “Oh, some people believe in negative freedom and some people believe in positive freedom—and negative freedom just means less government and positive freedom means more government.” And when you say it like that, it just sounds like a question of taste. And who knows who’s right?

Whereas historically speaking, to answer your question, the reason why people believe in negative freedom is that they’re enslaving other people, or they are oppressing women, or both. The reason why you say freedom is just keeping the government off my back is that the central government is the only force that’s ever going to enfranchise those slaves. It’s the only force which is ever going to give votes to those women. And so that’s where negative freedom comes from. I’m not saying that everybody who believes in negative freedom now owns slaves or oppresses women, but that’s the tradition. That’s the reason why you would think freedom is negative, which on its face is a totally implausible idea. I mean, the notion that you can just be free because there’s no government makes no sense, unless you’re a heavily drugged anarchist.

And so, as the Republican Party has also become the party of race in our country, it’s become the party of small government. Unfortunately, this idea of freedom then goes along for the ride, because freedom becomes freedom from government. And then the next step is freedom becomes freedom for the market. That seems like a small step, but it’s a huge step because if we believe in free markets, that means that we actually have duties to the market. And Americans have by and large accepted that, even pretty far into the center or into the left. If you say that term, “free market,” Americans pretty generally won’t stop you and say, “Oh, there’s something problematic about that.” But there really is: If the market is free, that means that you have a duty to the market, and the duty is to make sure the government doesn’t intervene in it. And once you make that step, you suddenly find yourself willing to accept that, well, everybody of course has a right to advertise, and I don’t have a right to be free of it. Or freedom of speech isn’t really for me; freedom of speech is for the internet.

And that’s, to a large measure, the world we live in.

You have a quote in the book about this that distills it well: “The countries where people tend to think of freedom as freedom to are doing better by our own measures, which tend to focus on freedom from.”

Yeah, thanks for pulling that out. Even I was a little bit struck by that one. Because if you’re American and you talk about freedom all the time and you also spend all your time judging other countries on freedom, and you decide what the measures are, then you should be close to the top of the list—but you’re not. And then you ask, “Why is that?” When you look at countries like Sweden, Norway, Denmark, France, Germany, or Ireland—that are way ahead of us—they’re having a different conversation about freedom. They don’t seem to talk about freedom as much as we do, but then when they do, they talk about it in terms of enabling people to do things.

And then you realize that an enabled population, a population that has health care and retirement and reliable schools, may be better at defending things like the right to vote and the right to freedom of religion and the right to freedom of speech—the things that we think are essential to freedom. And then you realize, Oh, wait, there can be a positive loop between freedom to and freedom from. And this is the big thing that Americans get a hundred percent wrong. We think there’s a tragic choice between freedom from and freedom to—that you’ve got to choose between negative freedom and positive freedom. And that’s entirely wrong.

What do you make of Kamala Harris’s attempt to redeem the word?

It makes me happy if it’s at the center of a political discussion. And by the way, going back to your first question, it’s interesting how the American right has actually retreated from freedom. It has been central for them for half a century, but they are now actually retreating from it, and they’ve left the ground open for the Democrats. So, politically, I’m glad they’re seizing it—not just because I want them to win, but also because I think on the center left or wherever she is, there’s more of a chance for the word to take on a fuller meaning. Because so long as the Republicans can control the word, it’s always going to mean negative freedom.

I can’t judge the politics that well, but I think it’s philosophically correct and I think we end up being truer to ourselves. Because my big underlying concern as an American is that we have this word which we’ve boxed into a corner and then beaten the pulp out of, and it really doesn’t mean anything anymore. And yet it’s the only imaginable central concept I can think of for American political theory or American political life.

Yeah, it’s conducive to the joy-and-optimism approach that the Democrats are taking to the campaign. Freedom to is about enfranchisement; it’s about empowerment; it’s about mobility.

Totally. Can I jump in there with another thought?

Of course.

I think JD Vance is the logical extension of where freedom as freedom from gets you. Because one of the things you say when freedom is negative—when it’s just freedom from—is that the government is bad, right? You say the government is bad because it’s suppressive. But then you also say government is bad because it can’t do anything. It’s incompetent and it’s dysfunctional. And it’s a small step from there to a JD Vance–type figure who is a doomer, right? He’s a doomer about everything. His politics is a politics of impotence. His whole idea is that government will fail at everything—that there’s no point using government, and in fact, life is just sort of terrible in general. And the only way to lead in life is to kind of be snarky about other people. That’s the whole JD Vance political philosophy. It’s like, “I’m impotent. You’re impotent. We’re all impotent. And therefore let’s be angry.”

Did you watch the debate?

No, I’m afraid I didn’t. I’m in the wrong time zone.

There was a moment that struck me, and I think it would strike you too: Donald Trump openly praised Viktor Orbán, as he has done repeatedly in the past. But he said, explicitly, Orbán is a good guy because he’s a “strongman,” which is a word that he clearly takes to be a compliment, not derogatory. You’ve written about the strongman fantasy in your Substack, so I’m curious: What do you think Trump is appealing to here?

Well, I’m going to answer it in a slightly different way, and then I’ll go back to the way you mean it. I think he’s tapping into one of his own inner fantasies. I think he looks around the world and he sees that there’s a person like Orbán, who’s taken a constitutional system and climbed out of it and has managed to go from being a normal prime minister to essentially being an extraconstitutional figure. And I think that’s what Trump wants for himself. And then, of course, the next step is a Putin-type figure, where he’s now an unquestioned dictator.

For the rest of us, I think he’s tapping—in a minor key—into inexperience, and that was my strongman piece that you kindly mentioned. Americans don’t really think through what it would mean to have a government without the rule of law and the possibility of throwing the bums out. I think we just haven’t thought that through in all of its banality: the neighbors denouncing you, your kids not having social mobility because you maybe did something wrong, having to be afraid all the damn time. African Americans and some immigrants have a sense of this, but in general, Americans don’t get that. They don’t get what that would be like.

So that’s a minor key. The major key, though, is the 20% or so of Americans who really, I think, authentically do want an authoritarian regime, because they would prefer to identify personally with a leader figure and feel good about it rather than enjoy freedom.

You mentioned the word banality, which makes me think of Hannah Arendt’s theory of the “banality of evil.” What would the banality of authoritarianism look like in America?

So let me first talk about the nonbanality of evil, because our version of evil is something like, and I don’t want to be too mean, but it’s something like this: A giant monster rises out of the ocean and then we get it with our F-16s or F-35s or whatever. That’s our version of evil. It’s corporeal, it’s obviously bad, and it can be defeated by dramatic acts of violence.

And we apply that to figures like Hitler or Stalin, and we think, Okay, what happened with Hitler was that he was suddenly defeated by a war. Of course he was defeated by a war, but he did some dramatic and violent things to come to power, but his coming to power also involved a million banalities. It involved a million assimilations, a million changes of what we think of as normal. And it’s our ability to make things normal and abnormal which is so terrifying. It’s like an animal instinct on our part: We can tell what the power wants us to do, and if we don’t think about it, we then do it. In authoritarian conditions, this means that we realize, Oh, the law doesn’t really apply anymore. That means my neighbor could have denounced me for anything, and so I better denounce my neighbor first. And before you know it, you’re in a completely different society, and the banality here is that instead of just walking down the street thinking about your own stuff, you’re thinking, Wait a minute, which of my neighbors is going to denounce me?

Americans think all the time about getting their kids into the right school. What happens in an authoritarian country is that all of that access to social mobility becomes determined by obedience. And as a parent, suddenly you realize you have to be publicly loyal all the time, because one little black mark against you ruins your child’s future. And that’s the banality right there. In Russia, everybody lives like that, because any little thing you do wrong, and your kid has no chance. They get thrown out of school; they can’t go to university.

We don’t imagine how a regime change is going to be at the dinner table. The regime change is going to be on the sidewalk. It’s going to be in your whole life. It’s not going to be some external thing. It’s not like this strongman is just going to be some bad person in the White House, and then eventually the good guys will come and knock him out. When the regime changes, you change and you adapt, and you look around as everyone else is adapting and you realize, Well, everyone else adapting is a new reality for me, and I’m probably going to have to adapt too. Trump wants to be a strongman. He’s already tried a coup d’état. He makes it clear that he wants to be a different regime. And so if you vote him in, you’re basically saying, “Okay, strongman, tell me how to adapt.”

Yeah, we could talk about Project 2025 all day. This new effort to bureaucratize tyranny—which was not in place in 2020—could really make the banal aspect a reality because it’s enforced by the administrative state, which is going to be felt by Americans at a quotidian level.

I agree with what you say. If I were in business, I would be terrified of Project 2025 because what it’s going to lead to is favoritism. You’re never going to get approvals for your stuff unless you’re politically close to administration. It’s going to push us toward a more Hungary-like situation, where the president’s pals’ or Jared Kushner’s pals’ companies are going to do fine. But everybody else is going to have to pay bribes. Everyone else is going to have to make friends.

It’s anticompetitive.

Yeah, it’s going to generate a very, very uneven playing field where certain people are going to be favored and become oligarchs. And most of the rest of us are going to have a hard time. Also, the 40,000 [loyalists Trump wants to replace the administrative state with] are going to be completely incompetent. When people stop getting their Social Security checks, they’re going to realize that the federal government—which they’ve been told is so dysfunctional—actually did do some things. It’s going to be chaos. The only way to get anything done is to have a phone number where you can call somebody at someplace in the government and say, “Make my thing a priority.” The chaos of the administration state feeds into the strongman thing. And since that’s true, the strongman view starts to become natural for you because it’s the only way to get anything done.

You’ve studied Russian information warfare pretty extensively. A few weeks ago the Justice Department indicted two employees of the Russian state media outlet RT for their role in surreptitiously funding a right-wing US media outfit as part of a foreign-influence-peddling scheme, which saw them pull the wool over a bunch of right-wing media personalities. Do you think this type of thing is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Russian information warfare?

Of course. It’s the tip of the iceberg, and I want to refer back to 2016. It was much bigger in 2016 than we recognized at the time. The things that the Obama administration was concerned with—like the actual penetration of state voting systems and stuff—that was really just nothing compared to all of the internet stuff they had going. And we basically caught zilcho of that before the election itself. And I think the federal government is more aware of it this time, but also the Russians are doing different things this time, no doubt.

I’m afraid what I think is that there are probably an awful lot of people who are doing this—including people who are much more important in the media than those guys—and that there’s just no way we’re going to catch very many of them before November. That’s my gut feeling.

While we’re on Russia, I do want to talk about Ukraine, especially since you’re there right now. I think one of the most unfortunate aspects of [the media’s coverage of] foreign wars—the Ukraine war and also the Israel-Hamas war—is just the way they inevitably fade into the background of the American news cycle, especially if no American boots are on the ground. I’m curious if this dynamic frustrates you as a historian.

Oh, a couple points there. One is, I’m going to point out slightly mean-spiritedly that the stories about war fatigue in Ukraine began in March 2022. As a historian, I am a little bit upset at journalists. I don’t mean the good ones. I don’t mean the guys I just saw who just came back from the front. [I mean] the people who are sitting in DC or New York or wherever, who immediately ginned up this notion of war fatigue and kept asking everybody from the beginning, “When are you going to get tired of this war?” We turned war fatigue into a topos almost instantaneously. And I found that really irresponsible because you’re affecting the discourse. But also, I feel like there was a kind of inbuilt laziness into it. If war fatigue sets in right away, then you have an excuse never to go to the country, and you have an excuse never to figure out what’s going on, and you have an excuse never to figure out why it’s important.

So I was really upset by that, and also because there’s just something so odd about Americans being tired of this war. We can get bored of it or whatever, but how can we be tired? We’re not doing a damn thing. We’re doing nothing. I mean, there’s some great individual Americans who are volunteering and giving supplies and stuff, but as a country, we’re not doing a damn thing. I mean, a tiny percentage of our defense budget—which would be going to other stuff anyway—insead goes to Ukraine.

And by the way, Ukrainians understand that Americans have other things to think about. I was not very far from the front three days ago talking to soldiers, and their basic attitude about the election and us was, like, “Yeah, you got your own things to think about. We understand. It’s not your war.” But as a historian, the thing which troubles me is pace, because with time, all kinds of resources wear down. And the most painful is the Ukrainian human resource. That’s probably a terribly euphemistic word, but people die and people get wounded and people get traumatized. Your own side runs out of stuff.

We were played by the Russians, psychologically, about the way wars are fought. And that stretched out the war. That’s the thing which bothers me most. You win wars with pace and you win wars with surprise. You don’t win wars by allowing the other side to dictate what the rules are and stretching everything out, which is basically what’s happened. And with that has come a certain amount of American distraction and changing the subject and impatience. I think journalists have made a mistake by making it into a kind of consumer thing where they’re sort of instructing the public that it’s okay to be bored or fatigued. And then I think the Biden administration made a mistake by not doing things at pace and allowing every decision to take weeks and months and so on.

What do you think another Trump presidency would mean for the war and for America’s commitment to Ukraine?

I think Trump switches sides and puts American power on the Russian side, effectively. I think Trump cuts off. He’s a bad dealmaker—that’s the problem. I mean, he’s a good entertainer. He’s very talented; he’s very charismatic. In his way, he’s very intelligent, but he’s not a good dealmaker. And a) ending wars is not a deal the way that buying a building is a deal, and b) even if it were, he’s consistently made bad deals his whole career and lost out and gone bankrupt.

So you can’t really trust him with something like this, even if his intentions were good—and I don’t think his intentions are good. Going back to the strongman thing, I think he believes that it’s right and good that the strong defeat and dominate the weak. And I think in his instinctual view of the world, Putin is pretty much the paradigmatic strongman—the one that he admires the most. And because he thinks Putin is strong, Putin will win. The sad irony of all this is that we are so much stronger than Russia. And in my view, the only way Russia can really win is if we flip or if we do nothing. So, because Trump himself is so psychologically weak and wants to look up to another strongman, I think he’s going to flip. But even if I’m wrong about that, I think he’s incompetent to deal with a situation like this. Because he wants the quick affirmation of a deal. And if the other side knows you’re in a hurry, then you’ve already lost from the beginning.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harbingers in an unhinged modern-day AU I just cooked up:

Pierro - Bitter ex-minister of the German empire. Tried to prevent ww1 and failed miserably. Went into exile during the years of the Weimar Republic. Current prime minister of the Russian Federation.

Dottore - Infamous Egyptian scientist. Expelled from multiple universities due to faults against ethics. Currently wanted by the egyptian government. Fled the country with the help of the CIA. Later, they betrayed them for the KGB. May or may not have been involved in the creation of supersoldiers Capitano and Columbina as well as the tampering with decomisoned Android model Scaramouche.

Capitano - Early soviet attempt at the creation of a supersoldier following the devastation of ww2 and the tensions of the cold war. Unconfirmed involvement in the soviet invasion of Afghanistan during the 80s and the russian invasion of Ukraine.

Columbina - Escaped soviet experiment. Thought to be an attempt at a new generation of supersoldier. Abandoned after the collapse of the soviet union due to a lack of funding. Subsequently, It escaped russian facilities and presumably remained at large.

Arlecchino - French ww2 orphan. Recruited as a Paris based spy by the KGB during the cold war. Alleged mass murderer. Current director of russian espionage after allegedly murdering the previous director.

Pulcinella - Ex-communist sellout. Has been the mayor of Moscow for many, many years. Regularly accused of electoral fraud.

Scaramouche - Runaway android. Created by the founder of Shogun Robotics. Declared faulty and destined for decommissioning. Vanished from Japan years ago and may have been found in Russia and tampered with by Dottore. Shogun Robotics has since forgotten about this failed model and now produces the aptly named "Shogun" model.

Signora - Former German academic turned mass murderer following the death of her husband, who was a soldier in the French front of ww1. On an unrelated note, the russian ambassador to Germany has an uncanny resemblance to her.

Sandrone - Founder, CEO, and senior engineer of Marionette Technologies. Her technology and weapons manufacturing empire has the russian federation as its biggest client. Her personal information remains a mystery since she does not appear in public. Rival firm of Shogun Robotics.

Pantalone - Current governor of the Central Bank of Russia and former economy minister of the Russian Federation. Has a distinct and fierce hatred of Chinese economic policy. Labeled an oligarch by Western observations. The single wealthiest man in all of Russia.

Childe - Formerly a normal russian kid living in the Ural's region. He became extremely violent and bloodthirsty after an accident where he got lost in the mountains due to heavy blizzards. Eagerly joined the russian armed forces and has since become their poster boy. Has an unwavering loyalty for Russia and it's president.

Tsaritza - Current president of the Russian Federation. Her ancestors were nobility in the times of the russian empire. Is mockingly called "the Tsaritza" by political adversaries and Western press.

#fatui harbingers#genshin impact#genshin pierro#il dottore#il capitano#arlecchino#columbina#pulcinella#genshin scara#la signora#sandrone#pantalone#childe tartagalia#text post#au idea#modern day au

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any headcanons for Pav? :)

yes

war and motherland

termina is anachronistic of course, so i am allowing any holes to thrive comfortably

i place his age during termina at 33 and his enlistment in his teens. i play around with him enlisting at 16. this would mean 17 years of service, which makes sense for a lieutenant colonel. this would also mean he enlisted sometime in the late 1920s when doing so voluntarily was possible and when kaiser was rising to power.

pav is the funger equivalent of belarusian. this is because i know more about belarus than other former soviet nations, and i am more comfortable writing what i know. (he speaks russian in one of my old posts, and i wish i could change it) this headcanon is also why i was very happy to draw pav in vyshyvanka for anon

we know that pav lost his family through an invasion during the first great war; belarus was invaded by germany in WWI, and many lives were lost.

youth and family

i believe pav's parents had him when they were older, and that he has an elder sister who left home as soon as he entered adolescence. his friends and relatives lived in the village with him. he spent his childhood roughhousing with his male cousins. the women he knew best were older women with traditional worldviews he had disdain for and a hormonal teenage sister he did not get along with. with these combined factors in mind, he developed sexist attitudes in his youth.

pav was easy to get along with as a child. he was brave and adventurous, even if he was not very talkative with strangers. he was happy with his village & the forests that surrounded it. he didn't really dream of travelling beyond. his teen years were soured by the great war and he underwent a transformation into a jaded and disconnected person. because, really, he would have gone crazy otherwise

i think it makes sense for him to be raised by worshippers of alll-mer but that his family's religion isn't very relevant to his upbringing besides sundays at the orthodox church and of course it fostering some core tenets of his worldview. as religion does. i do believe if this was the case, he would lose faith during the war or at least would not hold back his criticism of the religion.

gender and sexuality

there is a joke on my blog that pav is aroace. i did this because i am aroace. i do not believe it is true for him, but i do think he would have an aversion to sex & romance and that his behavior in the game is performative and caricaturistic. so that's where the joke comes from.

i believe pav is a cisgender man with attitudes typical of the time and a strange flamboyant flair that he easily abandons under duress. his sexuality could really be anything; it isn't very relevant to his character overall.

random

he likes nutty ice creams, nutmeg and chocolate

his favorite color once was green

he doesn't like alcohol much

he remembers people's names but not their faces. this is the case for one of his late friends

if he lived long enough to see the beatles he would not like them

he likes elk

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think a lot of people don't realize the Pax Americana, the massive decline in the frequency and severity of interstate wars since the end of the Second World War, is not a coincidence or happenstance. It is not an act of G-d, an unalterable status quo, or an accident. It is the product of decades of careful, hard work by diplomats, world leaders, civil servants, and political figures. And the primary guarantor of this peace, the product of their hard work is:

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

And NATO is precisely what Vladimir Putin is waging a targeted hybrid war to destroy.

The binding principle of NATO, of course, is that an attack against one is an attack against all. An assault against Poland will get America, Britain, Canada, Germany, and all of the other 32 member states to respond. This creates a tangible disincentive to attack, obviously. To be in NATO is to be assured that when shit hits the fan, you have the most powerful military in the history of mankind on your side, that you are protected from any expansionist neighbors. All across the world are nations that would likely be subject to hostile takeovers if their larger neighbors felt free to invade—Taiwan, Poland, the Baltics, Israel, Finland, etc. Some of these nations are not in NATO, but they are all American allies, and the American military is the bedrock of global peace today. You ever wonder why the US spends so much on a massive military in peacetime? Because they're paying for the defense of themselves, and Western Europe, ANDcontributing to the self defense capabilities of their allies—many of whom do have competent militaries of their own, but mutually benefit from the American security umbrella.

Today, of course, we're dealing with the problem of an expansionist Russia guided by an irredentist ideology that views Russia as holding a unique, privileged position between the decadent, declining West (Europe) and the foolish, ungovernable Asia. Eurasianism holds that Russia is the center of both worlds, and is both destined and obligated to take the reins of Europe and Asia and guide it to Russian-approved greatness. The Russian government systematically denies the legitimacy of Eastern Europe's national aspirations and cultures, arguing that it is no different from Russian culture and therefore deserves Russian governance. And if they can't take over these nations by unequal treaties and puppet regimes and troll farms, they'll do it directly with force.

But, of course, there's a problem. NATO. NATO is the obstacle in Putin's plans. A war with NATO would be, well, World War III. Russia can't afford to go to war with NATO, and they know that.

But what if... they could make NATO politically irrelevant?

And this is what brings us to our good friends Donald Trump and the Republican Party. The links between the Republican Party and the Russian state apparatus are a bit lengthy for the scope of this post, but the point is, Donald Trump has displayed a consistent admiration for Vladimir Putin, and a derision for NATO unheard of for any American president since 1949. Trump has described NATO as "obsolete" and even stated he would allow Russia to "do whatever they wanted" to nations that don't pay enough into NATO.

This is bad. Real bad.

Trump is doing what is in Putin's interest and trying to turn back the clock to the pre-NATO days—where nations were invaded by stronger neighbors, and there was no massive military alliance to block it. Putin is working to undo the Long Peace and create the circumstances that would allow him to bring back the dead Soviet empire by force. Yes, NATO would intervene if Russian troops set foot in Poland, but that will mean a lot less if the main backbone of NATO, the United States, has announced to the world that it will abandon its allies.

This is what makes European leaders so invested in the 2024 presidential election, and why the invasion of Ukraine shocked them so much—Putin was demonstrating he seriously wants to wage war for territorial expansion, and is willing to kill to do so. If Trump wins in 2024, not only will he enact Project 2025 and cause all kinds of damage to the United States' democracy, he will also create a world where autocrats are free to invade their neighbors if they want. China can invade Taiwan. Russia can invade the Baltics. North Korea can invade South Korea. Venezuela can invade Guyana. Azerbaijan can invade Armenia. He won't bring about World War III, he'll bring about a bunch of smaller wars, all over the world.

If you want peace and democracy, vote for Harris. If you want war and authoritarianism, vote for Trump.

It's as simple as that.

#discourse#disc horse#please vote#long post#ukraine#russia#russo ukrainian war#politics#world politics#american politics#us politics#NATO#trump#kamala harris#can you tell im a political science and ir major

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

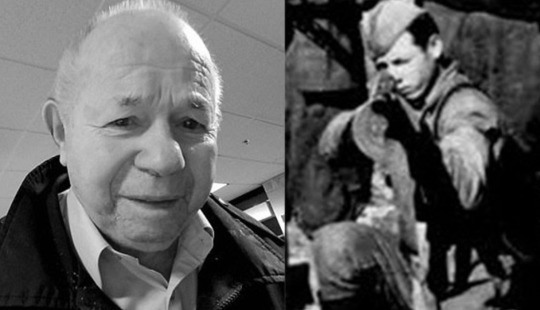

THURSDAY HERO: Benjamin Levin

Killing Nazis at age 14

Benjamin Levin was a young resistance fighter who, as one of the notorious “Avengers,” spent World War II hiding in a Lithuanian forest, emerging only to kill Nazis or bomb their supply chains.

Benjamin was born in Vilna in 1927. His father Chaim was a successful businessman and the family lived a comfortable life. In 1941, however, Chaim was tipped off that Nazi Germany was about to invade Lithuania. As Jews, that meant the Levins’ days were numbered. Chaim quickly sold his business at a loss, used the proceeds to buy weapons, and went into hiding with his family.

At the time, Benjamin was a 14 year old juvenile delinquent who’d started smoking at age 8 and was member of a street gang. After the German invasion, he chose not to stay with his parents in their hiding place, instead joining the fierce resistance group known as the “Avengers” led by Abba Kovner. Benjamin was an immediate asset to the group due to his unique combination of exceptional bravery and diminutive size. His baby face and unassuming appearance enabled him to avoid attracting attention, even in enemy territory.

Hidden in a Lithuanian forest, the teenager and his fellow Avengers killed Nazis, bombed their transportation lines, and smuggled life-saving food and medicine into the Jewish ghettoes. It was later estimated that the brave band of guerrilla fighters had killed 212 Nazis. Their policy was “take no prisoners.” In 1944, the Jewish fighters helped the Russian army liberate Vilna, after which they marched through town looking for Nazi collaborators to execute.

Benjamin’s parents survived the war in hiding, but when they returned to Vilna to reclaim their home, their former neighbors murdered them on the spot. With nothing to keep them in Europe, Benjamin and his sister moved to pre-state Israel, where he joined the Jewish militant group Irgun, fighting the British occupation of Palestine. Benjamin was in charge of helping Jewish survivors in Europe relocate to Israel. Benjamin’s street smarts and people skills served him well as he traveled through Turkey and Syria with European Holocaust survivors.

The Soviet army did not appreciate Benjamin’s work rescuing Jews from behind the Iron Curtain, and in 1947 he was arrested and sent to a Siberian gulag. After a year, Benjamin was released from the gulag and hitchhiked his way to Southern Europe, where he reconnected with the Irgun in Italy. The organization arranged for him to enroll in college and earn a degree in mechanical engineering. He was assigned to the engine room of a ship that sailed around the world, collecting money, weapons and volunteers to fight for the Jewish state.

The ship was called Altalena, and headed to Israel with hundreds of Holocaust survivors on board, as well as Jewish volunteers from around the world, and a cache of heavy ammunition secretly donated by France. When the Altalena reached Tel Aviv and tried to dock, the ship came under fire by the Haganah, a rival military group. Under machine-gun fire, young Benjamin leapt off the ship and swam to shore, then snuck into the country unnoticed. He had been through so much in the previous several years, had lived so many lives and assumed so many identities, that he actually forgot his own birthday. Later, he decided to make Passover – the festival of freedom – his official birthday.

Benjamin met his wife Sara, a Hungarian immigrant, in Israel, and ironically she was serving with the Haganah when they fired on the Altalena. Together they had two children, and moved to New York in 1967, where Benjamin worked as a mechanic and owned a gas station. In the 1990’s, Benjamin was interviewed extensively by Steven Spielberg as part of the Shoah Foundation oral history project.

For decades, Benjamin was an in-demand public speaker at New York high schools, where he spoke about the Holocaust and his remarkable life. Toward the end of his life, Benjamin was unable to speak, but he insisted on continuing his school appearances, with his son Chaim – named for Benjamin’s father – doing the speaking for him. Chaim remembered how much Benjamin loved interacting with students, and described his father as having “an enormous amount of energy and joy and love.”

Benjamin Levin died on April 13, 2020 at age 93. The last survivor of the Avengers, Benjamin died during Passover – his adopted birthday.

For heroically fighting Nazis and saving European Jews, and for educating generations of New York schoolchildren about the Holocaust, we honor Benjamin Levin as this week’s Thursday Hero.

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished The Wages of Destruction.

Solid 9/10.

Core ideas to take away:

work creation was a minor element of Nazi economic policy, a distant secondary concern after rearmament

rearmament had widespread public support in germany

shifting to autarky took extremely hacky and likely long-run unsustainable export controls, and even *export subsidies* because imports were still an inescapably vital input to industrial production in

controlling big business was largely a "soft co-opting" project while the agriculturalists were insane morons who were much more staunchly pro-nazi

once at war, Germany was going for broke from the very beginning and there was near-zero slack they could've squeezed out more war production from

truly pitiful productivity rate from Germany's conquered continental empire - the workers were far far more productive if deported to Germany than working in home countries

German surface navy seems useless, they didn't even have the oil to run the ships, and metal would've been better used elsewhere

Speer was a shit, Tooze hates hates him

bombing campaign actually was successful! specifically taking out the Ruhr

"blitzkrieg" doctrine was developed as they went; original 1940 invasion of France battleplan was to go "right up the center" not through the Ardennes and pre-battle production focused on heavy artillery ammunition

Bigger points: German "Strategy"

Germany escalated from diplomatic crisis to war with Poland/UK/France, and to war with the Soviet Union, and then America, out of a series of perceived closing windows of opportunity. First one was seeing UK/French production overtaking them in rates and catching up on stocks. In 1940 the US fully commits to aiding Britain, creating sense of "the bombers are coming eventually" and need to gain immediate advantage by conquering the Soviet Union.

Bizarrely, German production was focused on the Luftwaffe in preparation for fighting US/UK air war as Germany was getting ready for Barbarossa!

Declaration of war on US pitched as confirming alliance with Japan, but still feels stupid. Germany could just stay quiet and force US to either engineer entry to European conflict another way or stay out. Still seems less stupid, considering this is at a time when Barbarossa is coming apart.

But overall, a sound if massively risky plan assuming you accept the insane basic assumptions. Hitler's strategic vision often gets assumed to be terrible out of disgust for the consequences of his actions and their failure.

I really do wonder what the vibe was among German economic elite from 1942 onwards, it's obvious the war is not winnable, that you're very fucked, and that everyone is coming to kill you.

Anyways, good book and worth reading/listening to. Tooze could've slimmed down on the pre-war stuff. I find him vaguely irritating with how he brings up irrelevant things just to show how smart he is but that's probably just envy.

P.S.

The original Volkswagen was just a massive scam with no actual civilian cars being produced despite taking all the payments for the vehicles. Possibly suggests two dominant strains of conservatism? Former is old aristocratic conservatism of the nobility or classic US elite; latter is the populist oppositional culture right-wingism which is about 64% scam artists.

70 notes

·

View notes