#the extraordinaries trilogy

Text

A world without hope isn’t a world at all. Hope is a boon. Hope is a necessity. Hope, when need be, is a weapon, one to be wielded with a firm but just hand.

T. J. Klune, Flash Fire

#razreads#book quote#t j klune#flash fire#the extraordinaries trilogy#hope#optimism#queue have a good day now

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

EIGHT VICTORIOUS POVS PER THE NEWSLETTER

#scared tbh#Victor Sydney June. Mitch?..Eli.... Charlotte? another ExtraOrdinary character? ...Rios I bet.#and then one or two ghosts or new characters#probably new characters but ough how i want Dominic back or even Angie !!! hell#vicious#villains series#villains duology#villains trilogy

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

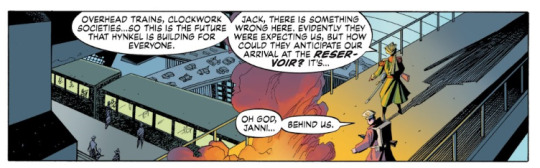

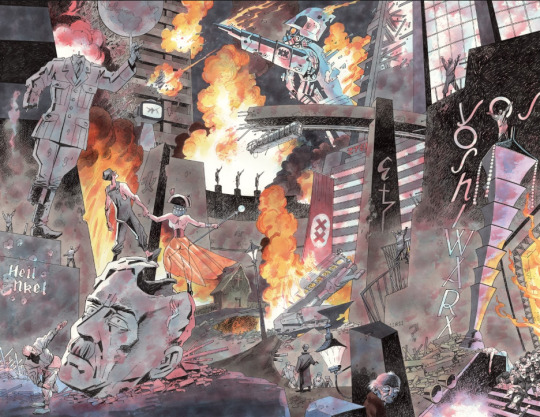

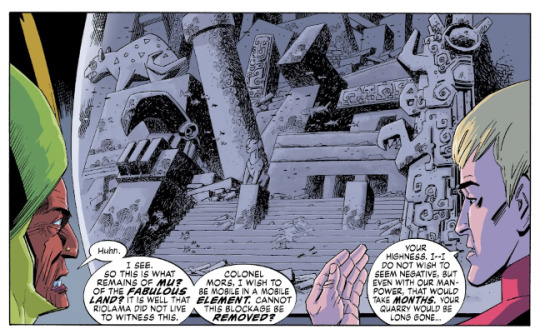

The fascinating thing about The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen at least for me is how it manages to perfectly balance having a premise that invites fandom hype at every cameo and somehow managing to piss off every fandom that's featured by almost always fundamentally getting something wrong about the source material in an attempt to be edgy.

Like were I still in my extremely embarrassing 15-year-old phase of 'Alan Moore can do nothing wrong' I'd call it a deliberate reflection on every Event Comic ever, but honestly I think it may be even more impressive that he did it by accident.

#league of extraordinary gentlemen#lxg#prime examples of this:#everything about Mina's on-page characterisation and what it says about Jonathan off-page#the fact that Godzilla gets taken out like a chump to hype up the Nemo trilogy#and me personally I'm still annoyed about the Will Stanton at Hogwarts thing#the dark is rising

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Public Domain and Creative Bankruptcy, How To Get the Most Out Of It?

The Public Domain and Commodification:

So 2024 started, with a lot of buzz around the public domain and the world’s most famous mouse, no I’m not talking about Basil the Great Mouse Detective. At the start of this year, the copyright on Steamboat Willie and thus the first designs of Mickey Mouse expired, and much like when Winnie the Pooh entered the public domain in the US in 2022, several…

View On WordPress

#Abigail Thorn#Alan Moore#Alice#Alice in Wonderland#American McGee#Blood and Honey#Dracula#eldritch horror#Frank Beddor#Frankenstein and Faust#H.P. Lovecraft#Hellsing#horror#Kuota Hirano#League of Extraordinary Gentlemen#Lewis Carroll#Looking Glass War#Looking Glass War Trilogy#Lovecraft Country#Madness Returns#Mickey Mouse#Mickey&039;s Mouse Trap#public domain#public domain horror#Shakespeare#Steamboat Willie#The Prince#Winnie the Pooh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m at Barnes and Noble with two of my friends and they’re not even going to get any books. It’s a bookstore, you get books at it.

#i’m buying the extraordinaries trilogy#hmph#barnes and noble#barnes and nobels books#the extraordinaries

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

bed covered in books feeling fucking fanTASTIC

#READING IS SUCH A THRILL DID Y'ALL KNOW ABOUT THIS#i've acquired two books off that queerplatonic ace rep rec list so far and i am. thrilled about it#the first one is not like. Extraordinary haha but i read like two hundred and sixty pages last night and it was enjoyable!#i have to remember that ya fiction is ya fiction sometimes. haha#but!!! ordered another one online (first one is a library book which was SO fulfilling to go grab) and it got here today and i'm SO pumped#reviews online were largely positive + complimented the like. visuals and dark fairy tale feel to it#and while one review said that the prose wasn't that good (i am always looking for writing that is Technically good)#(technically as in like. the technical aspects of it are well done. it's well executed)#i am still excited about the kind of character dynamics it promises me#i'll take some clumsy prose if it gets me platonic intimacy. i swear to god i will#ALSO IT'S ABOUT THE WILD HUNT AND I AM SO OBSESSED WITH THE WILDHUNT#and i was promised nonbinary knight character??? so. new fixation incoming perhaps#only choice now is whether to finish the first one or jump right into the next haha#i have what. less than a hundred pages of not even bones to finish?#i should get through that one haha#apparently it's a trilogy and the qpr comes in later so :rolling_eyes:#we'll see if i'm invested enough#or i'll read the webtoon or smth haha#I FUCKING LOVE THE LIBRARY I CAN REQUEST + HOLD THE NEXT TWO BOOKS#god. using public utilities is such a rush#anyway!!!! excited excited :)#valentine notes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

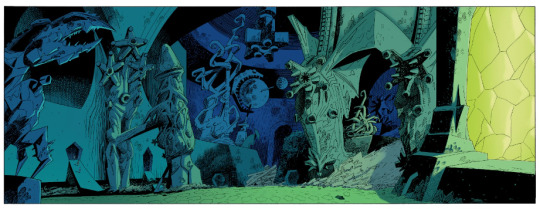

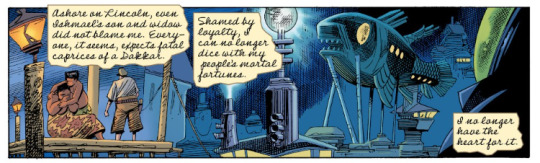

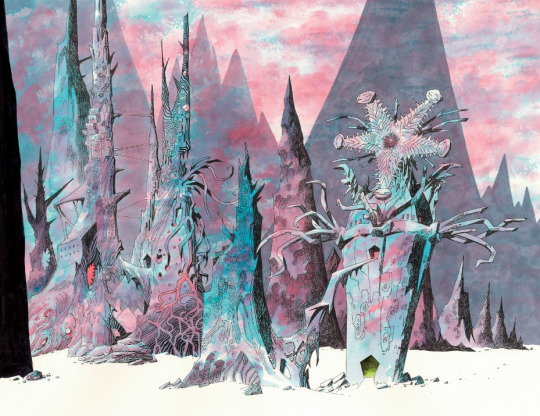

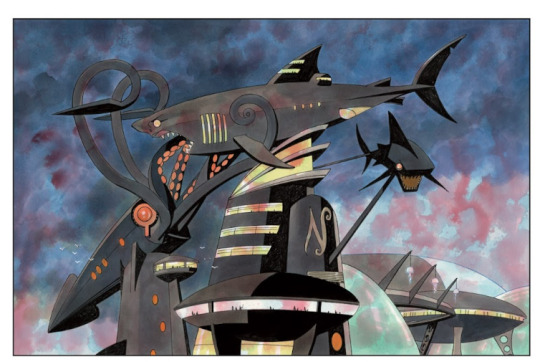

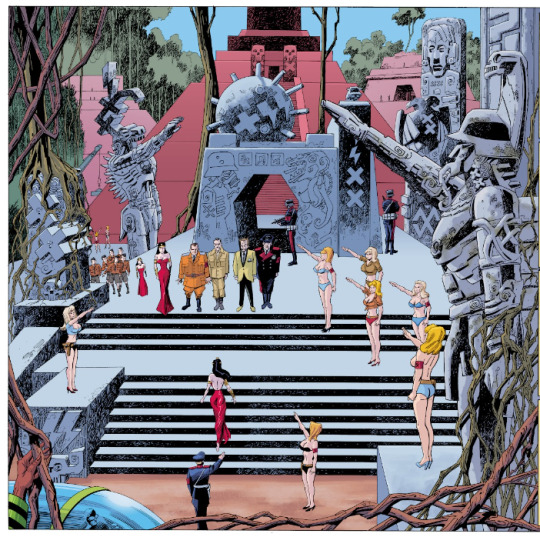

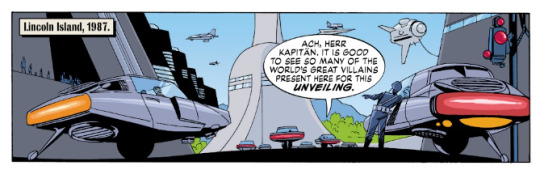

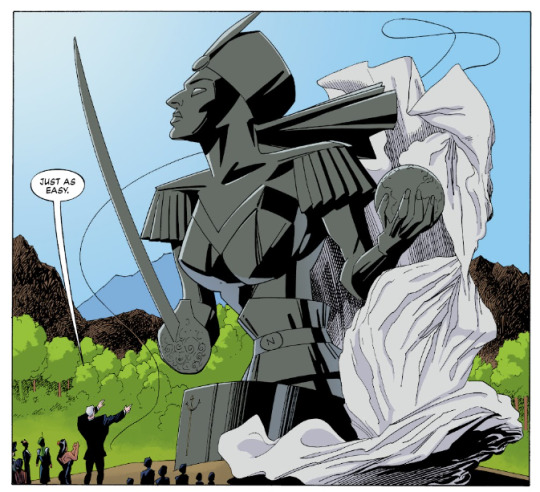

Architecture from The Nemo Trilogy

Written by Alan Moore

Art by Kevin O'Neill

#league of extraordinary gentlemen#loeg#comics architecture#nemo#nemo trilogy#alan moore#kevin o'neill#comics

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have bookmarked to start reading it once I return from Xmas food :3 Oh and I love male-to-male-survivor solidarity. Hope it exists in the comic too. Dracula's torture had left Jonathan on the brink of madness and starvation for months, and while Holt suffered for less time in the thrall it was unsubtle from the start. (I'd say Mina understands too, she had Dracula bleeding her then darkening, haunting and trying to control her mind 24/7 for a month.)

Also link it to the re:dracula podcast discord, there's hundreds of members!

Merry crimson. Thank you for the... ENTIRE NOVELLE. Bookbind the trilogy.

Oh, it's absolutely a heart-to-heart Harkers-to-Holt lovefest going on. While their friends are, of course, nothing but supportive, they also don't have the same kind of context or experience that Mina, Jonathan, and Robert have. Finding that mirrored connection and trauma in each other is, if not a relief, then a sort of mutual decompression; there's only so much you can talk about to someone who can't really understand that kind of abuse. Holt and the Harkers would lock onto each other in an instant.

Much as I love to wave my stuff in people's faces--and you can bet money I'm going to spam the dashboard with this Brick of a Fic--I don't want to just dump it in a Discord I've never been in before :c Anyone who thinks it'll be a good fit there should feel free to link it, but I don't want to be some goon who busts into someone else's party to start waving my work around

Merry Chrysanthemum, you're welcome for the reading homework

Also holy shit I could technically claim this as a legit trilogy, they're all public domain characters. I could one-up Goncharov with this. Hmm. Hmmmm.

👀

Thoughts, @mayhemchicken-artblog?

#that would be a trip wouldn't it?#Dracula Daily -> Mayhem Chicken inspiration -> League of Extraordinary Gentlefolk idea -> Fanfic inspired by unmade comic -> AU Trilogy#... -> Actual novellas apparently#something to ponder#anyway#my writing#robert holt#the beetle#jonathan harker#mina harker#dracula#the league of extraordinary gentlefolk

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

gotta love how the shadow and bone tv show was like hey let's combine these two stories set in the same world so that they're happening at the same time and the characters all meet and hang out and are friends :) and in doing so they absolutely butchered all of those incredible characters, bulldozed through the storylines, and left off in such a nonsensical position that there's simply nothing compelling left to be said lmao

#like the three most interesting things in Alina's trilogy are#morozova wasnt a fucking fabrikator: he was just Grisha#he wasnt beholden to the split of manipulating flesh/the elements/material#he just did it#and they ignored that entirely#second was the concept of sainthood#what does it mean to be venerated as a saint when youre still alive#saints are always martyrs! its not possible to be a living saint!#and when you finally get morozova's story#well#he wasnt a saint#he was a person who happened to have extraordinary abilities#but in every other sense was just an ordinary human being#and alina struggles herself with being worshipped when shes just a girl#how can you be a living martyr? how can you be a god when you still have a human heart beating in your chest?#meanwhile the show is like oh hey heres another saint lmao isnt it cool how powerful and Girlboss she is lmao#and alina acting like sankta is a title instead of an albatross#anyway the third thing is alina's entire relationship with the darkling which was wasted so thoroughly#truly an awful time#i wont even go into the crows because like#six of crows is a PERFECT story#exceptional characters#believable people with believable flaws who do incredible things anyway#a story that fucks so hard i still haven't stopped thinking about it years later#and they destroyed it!!! they ruindd it!!!!#agh im so mad about it#shadow and bone tv

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterlist

Below are all the fics, both one-shots and multichapter, that I have written. It will be updated regularly.

I tend to write about The Exorcist (TV show), Bates Motel, Hannibal, Marvel Cinematic Universe, and Grimm. However, you will also find I have written about Supernatural, Supergirl, Zoey's Extraordinary Playlist, Timeless, and Black Sails.

Whether you are reading these for the first time or returning to your favorites, I hope you enjoy! Feel free to leave comments on AO3, if you wish!

One-shots

The Morning After (The Exorcist)

Dream a Little Dream of Me (Bates Motel)

Dark Roast My Heart (Hannibal)

Broken (Timeless)

Song For a Winter's Night (Hannibal)

Love.Sex.Angel.Baby. (Supernatural)

Some Enchanted Evening (Bates Motel)

Zoey's Extraordinary Second Chance (Zoey's Extraordinary Playlist)

Bury the Past (Marvel Cinematic Universe)

No Greater Force (Star Wars sequel trilogy)

Multichapter

The Trials of Tomas Ortega (The Exorcist)

The Very Thought of You (Bates Motel)

Through a Glass, Darkly (The Exorcist)

The Odyssey (Bates Motel)

A Taste Before Dying (Hannibal)

God Only Knows (The Exorcist)

Ready For You (Bates Motel)

Yea, Though I Walk Through the Valley (The Exorcist)

Underneath Your Skin (Supergirl)

And Then He Kissed Me (Grimm)

From the Ashes (Hannibal)

It's True That I Was Made For You (The Exorcist)

Holiday Hallmark with Smut anthology

All I Want For Christmas With You (The Exorcist)

Wrapped In Red (Bates Motel)

Maybe This Christmas (Supernatural)

Santa Grimm Is Comin' To Town (Grimm)

Unwrap My Heart (Black Sails)

Marvel, Actually (Marvel Cinematic Universe)

Endgame? What Endgame? MCU series

Mad Boy's Love Song

Nat & Maria's Emotional, Sexual Bender

In My Soul, In My Throat

This Is Where We Begin

Maria and the Weird, Unexpected, Totally Awesome Pre-Birthday Adventure

Love, Sex, and the Whole Damn Thing

#masterlist#bates motel#the exorcist#hannibal#grimm#marvel cinematic universe#black sails#supernatural#timeless#zoeys extraordinary playlist#star wars sequel trilogy#my fic#am writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ep79 Evan's Last Hurrah w/ Andrew Leeds! (Hollywood!)

3 dudes are in a room bitchin' as we're joined by Mr. Andrew Leeds - who's gone from strength-to-strength since debuting on Broadway as a 6-year-old! (Say what?!) This week, we bid fare-thee-well to Evan with the final part of the Falsetto's trilogy, Falsettoland, as well as Adalitas Way and their self-titled album.

Plus we chat the Falsettos movie that never was, Mandy Patinkin, Zoey's Extraordinary Playlist- and other titles, Groundlings, as well as gender-swap the characters in Marvin's trilogy- among so much more!

www.twitter.com/LeedsAndrew

#Groundlings#Andrew Leeds#Andrew Harrison Leeds#Zoey's Extraordinary Playlist#Zoey's#Falsettos#Falsettoland#William Finn#March of the Falsettos#The Marvin Trilogy#Falsettos Trilogy#Music#Comedy#Broadway#Metal#Heavy Metal#Musicals#Critique#Reviews#Musical Theatre#West End#Aussie#Podcast#Commentary#Prog Rock#Prog Metal#Progressive Metal#Thrash#Thrash Metal#Thrash 'n Treasure

1 note

·

View note

Text

Love […] was like trust: a fragile thing that needed time to grow. But the more it did, the stronger it became.

T.J. Klune, Heat Wave

#razreads#book quote#t j klune#heat wave#the extraordinaries trilogy#love#time#strength#growth#queue have a good day now

0 notes

Text

Extraordinary redraw.

#as much as they would not fucking look like that I'm obsessed with this panel#tw extraordinary#victor vale#eli ever#angie knight#vicious#ve schwab#villains series#villains duology#villains trilogy#vicious ve schwab

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

new video about Edgar Wright's Cornetto Trilogy, and how everyone* keeps getting them wrong! this video is sponsored by Nebula, a place where you can watch the original version of this video before I had to tweak it for YouTube's copyright bots. (by clicking that link, you can get an annual subscription for 40% off.) or you can just back me on Patreon, which is also cool and good.

transcript below the cut.

I adore Edgar Wright’s Cornetto Trilogy. I flirted with making a video about it ages ago, had a draft of a script, but ultimately decided it wasn’t about anything except “here’s a thing I like, and here are its (I thought) very obvious themes.” So I shelved it. But, in the years since, I have seen multiple video essayists on this here website claim that these movies are about growing up and taking responsibility. (I say “multiple.” It’s not a lot. But it’s more than one! And that’s enough.)

These people are 100% wrong.

Lemme lay it out: the Cornetto Trilogy is not about growing up. It is not about taking responsibility. It is the exact opposite, and that’s not subtext. It is three movies about stunted manchildren thrust into extraordinary circumstances, and each, in the end, is saved - is redeemed - by abandoning his character arc and failing to grow or change. It is a three-part love letter to immaturity.

And I guess I have to set the record straight.

Sometimes making a video about a thing you love is an act of appreciation. And sometimes it’s out of spite.

The Cornetto Trilogy is three movies: Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and The World’s End. All three are written by Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright; Pegg stars, and Wright directs; all three center on a relationship between Pegg and real-life best friend Nick Frost, which makes each film a reunion of the core team behind Spaced (excepting, but for a small role in Shaun of the Dead, Jessica Hynes). The three films span three genres: zombie apocalypse, buddy cop, alien invasion; each features a Cornetto ice cream cone: strawberry to represent blood, original blue to represent the police, and mint to represent little green men; this is a joking nod to Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Trois Couleur films, Bleu, Blanc, and Rouge, which were based on the colors and themes of the French flag (I don’t care what you say, Emily: #TeamRouge); that nod is funny because Trois Couleur is high-art drama and these are comedies. All three are parodies of, tributes to, and actually surprisingly good executions of their respective genres. And the hook, the gag at the center of all these movies, is that Simon Pegg plays a character wholly unsuited to be starring in this kind of film.

Shaun, the burnout, is the wrong person to survive the zombie apocalypse; by-the-book British bobby Nicholas is the wrong person to lead an American-style bombastic actioner; and alcoholic asshole Gary is the last person to save the world from aliens.

And I think that’s where people get stuck. Because “schlub finds himself protagonist of a genre film” is the elevator pitch for like a dozen Adam Sandler movies. The genre trappings may be as mundane as parenthood or mandated anger management classes, or as high-concept as action movie, whodunnit, or time travel It’s a Wonderful Life if Clarence were Christopher Walken as the angel of death (that… that makes it sound good, it’s not, don’t see Click; leave Frank Capra alone, Adam). But all these movies have the same basic shape: an extraordinary situation forces a guy to confront his shortcomings, which always stem from having never grown up. And you probably haven’t seen all of these movies, but if you’ve seen any, I bet you have assumptions about how the rest end: even though “Adam Sandler acts like a child” is generally the selling point of an Adam Sandler movie, they all end with some lip service toward becoming an adult: hey man, grow up a bit; appreciate your family a little more; square your shoulders; clean your room. This is so standard, it was parodied mercilessly in Funny People.

And this was a formative microgenre for my generation! Whole universe turns itself upside down to teach some shitty dude to, like, do the dishes and pay his wife a compliment now and then - Liar Liar, Bruce and Evan Almighty (all directed by the same guy, by the way). So I don’t blame people of a certain age for seeing the first act of Shaun of the Dead and thinking “I know where this is going.” And when, at the last minute, it swerves and goes someplace else, you could read that as a gag, a final subversion of expectation, still the same basic shape. But no! No! Once is a gag - thrice??? Thrice is a thematic statement!

So lemme make my case. I’ma take you through these movies one by one - we’ll talk about the manchildren and the expectations set by the genre, and then we’ll talk about that last-minute swerve and what it means. And then you’ll tell me I’m right and apologize!

Shaun of the Dead:

Shaun is a man in his twenties. What kind of manchild is he? He’s the slacker.

What is his problem? He needs to sort his life out. Shaun doesn’t know how to take action. He hasn’t advanced since college - he’s been working the kind of job a teen takes over the summer for like a decade, lives with the same best friend, has the same petty fights with his stepdad, goes to the same pub every week with the same group of people. He can’t make a reservation, he can’t manage a calendar, he’s a washup. This makes his girlfriend, Liz, feel stifled, trapped; he is a weight around her ankle, taking her on the same date week after week, keeping her from living her own dreams, having her own adventures. She gives him one last chance to prove he can sort his life out, and he blows it, and she dumps him.

And then: a zombie movie happens.

The genre forces him to confront his shortcomings: to survive, and save his loved ones, he’ll have to take action, make plans, be decisive. This is a common fantasy: when you feel ground down by the mundanity of life, you might imagine, oh, if only a crisis would happen, like a zombie virus outbreak, where my normal-life problems like “am I gonna make rent,” “is my girl gonna take me back,” “is my roommate gonna kick out my stoner buddy who’s crashing on the couch” become meaningless, and it’s immediately clear what’s really important, what matters. Then I’d know exactly what to do. It’s why disaster movies work as escapism: a necromantic plague - or at least the fantasy of one - is sometime preferable to normal life.

Hot Fuzz:

Nicholas is a man in his thirties. What kind of manchild is he? He’s the hall monitor.

What is his problem? He can’t switch off. He is a hypercompetant police officer with a rulebook where his brain should be. He’s so good at being a cop that he’s spotting and unraveling crimes even on his day off. He can’t maintain a relationship, has no friends, all his coworkers hate him because he keeps finishing their work for them, and his stats show up the rest of the force so badly that they scuttle him out to the country.

Now you might be thinking, “Mmm. A fastidious police officer who can’t have fun? How is that a manchild? Sounds pretty grown-up to me. You’re reaching, bud.” Ohhhh ho ho, smartass, do you remember this scene? [bar scene] Yeah! Nicholas Angel has a five-year-old’s notion of law and order. He’s still playing cops and robbers.

And that’s a problem, because then: an action movie happens.

It doesn’t happen all at once: he goes out to the country and finds they do things a bit differently there. They are (ostensibly) less concerned with rules than what than the rules are for: if the purpose of drinking laws is to keep the streets safe and orderly, and letting some people off with a warning or allowing kids drink so long as they do it inside achieves that end, the rule can be bent. That’s a judgment grown-ups can make; I mean, they’re the ones who wrote the rules in the first place. So be lenient with shoplifters, don’t hassle people for speeding; this isn’t the Big City, you can use your better judgment. But Nicholas never got past doing whatever Mom & Dad said; obedience, and trusting whoever’s up the chain, is his entire moral framework. He can’t accept that bending the law could be more righteous than following it.

But also maybe there’s a criminal conspiracy murdering people and writing it off as accidents and the police chief might be in on it. Or maybe Nicholas is so desperate for a big case with no moral ambiguity that he’s seeing things where they aren’t.

The genre forces him to confront his shortcomings: either there’s nothing going on and he needs to chill out about procedure, or the department is corrupt and he’ll have to go rogue like it’s Point Break - and this is how he experiences Point Break. [“paperwork”]

No matter what, he’ll have to bend the rules, which he constitutionally cannot do.

The World’s End:

Gary is a man in his forties. What kind of manchild is he? He’s the delinquent.

What’s his problem? Pfffft. What isn’t his problem? Gary is a manipulative, narcissistic, lying, self-destructive, ignorant, violent, thieving, shit-talking, unapologetic asshole who peaked in high school when being all those things was still kind of badass. The greatest night of his life was the drunken pub crawl after graduation he and his friends didn’t even finish, and he’s been tumbling downhill ever since. He’s spent his life ruining everyone who knows him until there’s no one left to ruin but Gary King. So now it’s time to bully the old gang into going back home with him to relive that night by finishing the pub crawl, because, in his own words, it’s all he’s got. And he and his friends have to confront how home has changed since they left - the bars have gentrified, not everyone recognizes them; the defining, epic deeds of Gary’s youth have been forgotten. You can’t actually go back because that place doesn’t exist anymore.

And then: a sci-fi movie happens.

Turns out the town’s been taken over by aliens, and all the people who couldn’t conform to their new order have been replaced with robots! That’s why no one recognizes them! And that’s why the pubs all look the same: the aliens are homogenizing everything! And it’s clear, if they can’t get Gary and his friends to play ball, they’ll roboticize them as well! The obvious move is to get the hell out of town, but Gary keeps inventing excuses to stay and finish the pub crawl, and they sound pretty sensible because the group’s already five pints in. The genre forces him to confront his shortcomings: sooner or later he’s gonna have to give up on recapturing his youth and do what’s best for him and his friends now, even if it means running back to the city where all his problems live.

So there we have it: the characters cross the threshold into an unfamiliar world where an external conflict cannot be addressed without resolving the tension within. The slacker will have to get his shit sorted, the hall monitor will have to break the rules, and the delinquent will have to do what’s good for him. And, to an extent, all three know this! The movies Wright and Pegg pay homage to exist in these stories - Shaun knows what a zombie is, Danny keeps Nicholas up watching Point Break and Bad Boys II, and Gary and friends know bodysnatcher movies so well they have philosophical debates with the robots about whether “robot” is the PC term.

So, yeah, if you turned the movies off there, I could forgive you for thinking that’s where they’re headed. But you goofballs watched them to the end and then made content about them, what is wrong with you???

What actually happens in the second halves of these movies?

Shaun twigs that he’s in a zombie movie and, at first, tries to play the part - his survival plans are miniature hero’s journeys with him as protagonist, wherein he’ll save the day by neatly confronting all his flaws. He’ll resolve parental conflict by saving his mom from his zombified stepdad, resolve romantic conflict by showing his girl he can come through when it counts, and resolve internal conflict by being a man who saves the day. And all his plans suck! It’s just the same plan he always comes up with! Dragging around the same useless liability of a bestie, collecting the same group of people, and holing up in the same pub! He doesn’t save his mom: his stepdad apologizes, resolving their conflict for him, and then survives in zombie form but Shaun’s mom gets killed; most of the friend group gets killed because the crisis does not actually suspend but in fact amplifies their personal grievances; and he doesn’t save the day, just manages not to die long enough for the military to show up.

But… well, Liz wanted adventure and now she’s had enough for a lifetime, so… she’s down to just be boring with him for a while - sit on the couch, watch TV, hit the pub. Beats running for your life. Tensions with the roommate are gone cuz roommate died, but rent is covered cuz Liz moved in. Zombies don’t get eradicated, just folded into normal life, so Shaun can mindlessly play video games with his bestie forever, and it’s not a problem that bestie doesn’t have an income cuz he doesn’t need food or shelter.

The zombie apocalypse doesn’t make Shaun sort his life out, it changes the world til he doesn’t have to.

When Nicholas discovers that, yes, there is definitely a murderous criminal conspiracy inside the police department, he recognizes the only way to bring about justice is to become what Danny has always wanted and go Dirty Harry on the town. It’s either that or just swallow the crimes. But he does neither. He and Danny go on an epic shooting spree, recreating famous movie scenes, taking out the entire criminal organization against all odds, and spouting badass one-liners… but everyone who helps them is a cop, they don’t actually kill anyone, all perps are formally arrested, and they fill out all the paperwork. I think he even properly signs out the weapons. He never switches off, never breaks a rule, does absolutely everything by the book, only… louder. And this violent showdown saves him from the chill town with lax rules he thought he’d moved to. Now he, with his five-year-old notion of right and wrong, is in charge of the police department.

The buddy cop actioner doesn’t make Nicholas bend the rules, it changes the world til he doesn’t have to.

Gary knows exactly how a movie of this sort is supposed to go and spends the whole movie running from it. Friends and secondary characters keep sharing these poignant moments with him, because they know this story, too: yeah, he’s gonna reject help at first, but sooner or later he’ll hit rock bottom and then someone will get through to him. And, as the night goes on, and the characters get drunker and drunker, and Gary passes up more and more opportunities to abandon the pub crawl and go home, these moments take a tone of desperation. They start to sound more like interventions; like, Gary, we all know you’re going to come to your senses but could you hurry up with it??? How many of your friends need to literally die for you to shape up? Are you gonna get them all killed?

And the answer is: Gary will never shape up! To Gary the Human Dril Tweet, his friends trying to save him, psychiatrists trying to treat him, and aliens trying to assimilate him are all the same thing. He doggedly makes it to the end of the pub crawl and confronts the alien overlord who tells him all the technological advancements of the past few decades - all the efficiency and homogenization that’ve changed the face of his home town - are their doing. The Information Age is an intervention on behalf of Earth, a pan-galactic effort to save humanity from itself. And the reason they’ve been replacing people with robots is some people are too fucked up to go along with it.

And here’s Gary, King of the Fuckups, brashly declaring that fucking up is what makes us human. There is no freedom without the freedom to ruin your life. We are endowed by our creator with the right to be drunken, ornery pieces of shit.

He tells the aliens to piss off and he’s so fucking annoying that they do, and they take the Information Age with them.

Now… I know… ugh… I know a lot of people love this movie, say it’s the best of the three. Some friends who’ve struggled with mental health or just being an adult under late capitalism really identify with Gary, and the valorization of being a mess. I see you, you’re not wrong, I get it, I really do. But can we just… not “but” but “also” can we… can we also admit that this ending is… this is Space Brexit.

Like, literally it’s an alien invasion but symbolically this is Gary rejecting the adult world of rules and authority and doing what’s best for the community and that’s how Brexiters view the EU. And people keep telling him “Gary, this is in your best interest” and Gary says, I don’t want my best interest! I am registered in the anti-Gary’s Face Party and I will cast my vote by cutting my nose! I choose to do what’s bad for me.

And, like a true Brexiter, he chooses for everybody.

Now tell me that’s a movie about growing up. Gary collapses human civilization in its entirety rather than change, and in the world that follows, he thrives… by being an immature, irresponsible bag of garbage.

To Wright and Pegg, growing up is death, and these are movies about being alive. These characters don’t cross the threshold back into the ordinary world with the ultimate boon of character growth; all three stay in the extraordinary world. The zombies remain, the robots remain, Nicholas is offered his London job back and chooses to stay in the country. These are stories about normal life spontaneously turning into a genre film, and they are made with deep love for those genres; why would they end with leaving those genres behind? Because it’s what Adam Sandler would do?

So there you have it. I rest my case.

“Okay Ian. Why does this matter?”

…what was that?

“You’ve made your point: these movies aren’t about growing up or taking responsibility. So what?”

Uhhhh.

“Bring it home for us.”

…

“Why do you care so much?

[breath]

I wrote the first draft of this script when I was around Shaun and Nicholas’ age, and “so what?” is why I shelved it. Now I’m Gary’s age, this video’s been in the back of my brain the whole time, but I got this far and “so what” is where I got stuck, again. This is why the CO-VIDs came out quicker, cuz I let myself end with “so that’s interesting!” and got on with my life. But there’s clearly something sticky here, more than “someone is wrong on the internet.” (Also, to the YouTubers I’m vaguebooking, who said these were movies about growing up - I’m way more annoyed at the folks I’ve argued with on Twitter about this, you just made a better rhetorical device; you do not owe me an apology!) (Also, to the commentariat: I am not extrapolating this from like two data points, this is chronic and recurring and has been bothering me for years.)

There are a few directions I could take this to give it some “cultural weight.” I could put on my social justice hat and talk about how the “crisis of adulthood” doesn’t play as broad comedy unless you look like Adam Sandler or Simon Pegg, or put on my class analysis hat and talk about how signifiers of adulthood are, traditionally, ways of spending and accruing capital which are, today, often inaccessible to people under 40.

And that’s all legit, but here’s the real deal: I’m just mad at Gary. The world changed around Shaun such that he could stay a child. And Nicholas ended up somewhere he could stay a child. If you missed that, you’re wrong, but whatever. But to say that Gary grew up grinds me, because Gary chose this. The whole movie is people telling him to grow up, and he says no! He says it out loud! He says it to the literal end of the world. To walk out of the theater and say “that’s a movie about growing up” is more than a mistake, it’s a refusal. It’s trying to “fix” the movie by fitting it into a more familiar shape, so it doesn’t say what it says, so Gary isn’t who he is, who he chooses to be.

I’m being cheeky when I say this because he’s a fictional character, but saying Gary grew up is enabling.

Gary says there’s no freedom without the freedom to ruin your life, which is the problem with alcoholics and libertarians: it’s not just your life, Gary! You live in a community, a culture, and an ecosystem! Your actions - everybody’s actions - impact other people! That’s just the way the world is! You can’t shit yourself at the bar without other people having to smell it. We’re all fuckin’ connected, man! You don’t want anyone’s will imposed on you; you spend the whole movie imposing your will on everyone else! You say humans don’t wanna be told what to do, and then you decide humanity’s future by yourself with no input or consent from anyone!

People point to Gary ordering water in the last scene instead of beer as evidence that he got sober, like that’s proof that he did grow up in the end, which are you fucking joking??? Getting sober is a shorthand for maturity the way buying a house is, it doesn’t signify anything in and of itself! Gary drank to escape the adult world of rules and responsibilities! So, yeah, under normal circumstances getting sober would mean he’s made peace with that world and is ready to integrate. But that’s not what happened! The thing he was escaping doesn’t exist anymore! He literally destroyed it!! People died! Probably millions! Now he lives a happy life LARPing as Omega Doom - no I don’t expect you to catch that reference! He doesn’t need to drink! He is literally reliving the best day of his life forever. And even if it did mean personal growth, the idea that a person could make what would be, unequivocally, the most selfish decision in human history, and then spend his life celebrating the outcome, oh but if he overcame a personal demon in the process then on balance that’s maturity? That is lightspeed solipsism! Who are you if you think that way? Are you all Adam Sandler???

And none of that makes this a bad ending, or Gary a bad character. I mean, he is the reason The World’s End is my least favorite, and I don’t like the ending, but I don’t think it’s bad that I don’t like the ending. Rather than watch another addict pull his life together or destroy himself, we watch a downward spiral with so much gravity the whole world self-destructs alongside him. And that’s why The World’s End is the most interesting of the three: it is a bold choice, and I think we are free to feel however we want about the conclusion Gary engineered for himself. I don’t think it’s valid to pretend it didn’t happen.

In the context of the trilogy, we see that Shaun’s immaturity is mostly a problem for Shaun: he would be, at worst, a footnote in the lives of the people who love him; “yeah, I liked Shaun a lot, but I couldn’t carry him through life anymore.” Nicholas is the kind of overachiever that is useful if pointed in the right direction; juvenile code of ethics aside, he is, empirically, helping the community (within the entirely fictional framework where that’s a thing police do). If the world hadn’t changed to turn their flaws into strengths, they would still be relatively harmless. Gary is what happens when immaturity isn’t harmless, and shows us how a world built by that immaturity would look.

There is an appeal to Gary King, a wish fulfillment. Letting your id fully off the leash because you no longer care what anybody thinks - it’s why some people drink, and it’s why some people would like to drink with Gary. But if that’s not just your Friday night, not just your twenties, but that’s your life? There is a destination at the end of that road, and it’s Gary doing something truly ugly. And we see that ugly thing the way Gary sees it: as awesome. But then you see the reality: the Monday morning after the Friday night. We went out with Gary and he did something terrible.

And I’m not telling you to hate Gary for it; I’m not saying Gary can’t be forgiven. In fact, seeing it for what it is is the only way Gary could be forgiven, because, if he “grew up and took responsibility,” there’s nothing to forgive.

I think this is the only way the trilogy could have ended. I mean, you make stories about boys who get older and older and don’t grow up, it eventually becomes a problem. There’s only two ways to resolve it: you either end with a guy actually sorting his shit out, or you go for broke and show what happens if he doesn’t. And I think some of us boys saw that and said, “no, noooo, they did grow up! all three of them!” rather than say, “haha! hahaaa! ……………shit.”

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Your sister found me because she was ready.”

Kara frowns. “Ready for what?”

“For the truth.” Lena replies simply. “To wake up and leave the lie behind.”

“The lie?” Lena’s words bring back echoes of Alex’s message. The Matrix still has you… You’ll find me, if you’re ready to wake up. “You mean… the Matrix?”

“Yes.”

Kara leans forward, her attention caught. “What is the Matrix?”

Lena sighs, her eyes clouding over. “I’m afraid no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself. Right now, all I can tell you is that the Matrix is everywhere. It’s all around us. It’s in the air we breathe, in everything we touch…”

Lena ventures a hand between them to touch Kara’s, their hands connecting in the slightest. And even though she knows that she’s not really touching Kara’s hand, her mind feeds her the sensations of it — the softness of Kara’s skin, the gentle press of her flesh under Lena’s fingers.

Lena draws her hand away, and Kara follows it avidly with her eyes. “For you to know what the Matrix is, I have to go back to the beginning. Or at least, to where it begins for us.”

Or, the Supercorp Matrix AU

[So I found an old Matrix AU from a different fandom while I was rooting through my drive, and I thought it could be retooled into a Supercorp AU. Little did I know what I was inviting into my brain, but here we are suffering the consequences. (And now I have 2 different supercorp Matrix AUs. Great.) Spoilers ahead for the OG trilogy.]

In the movies, Neo is the One, but there are other Potentials. Each Potential displays extraordinary abilities beyond the standards of normal. Kara and Lena are both Potentials. Either one of them could be the One.

It begins in the Matrix, when Lena gets adopted by the Luthors as a little girl.

The Luthors are a picture-perfect family. Powerful, affluent, and respected. The father, the mother and the golden son. And Lena - smart, angelic and pretty, the perfect daughter - is the ideal addition to make their picturesque family complete.

Except when she's about 4 or so, it becomes apparent that Lena is not like other children.

It's immediately clear that her intellect far surpasses people four, five times her age. Lena is sharp and brilliant, able to grasp complex concepts most adults cannot. She seems to see the world around her in a different way.

The Luthors are no strangers to gifted children, their son Lex was deemed a prodigy at around the same age. At first, Lionel and Lillian take this as yet another proof of how exceptional Luthors are, and Lena is proudly displayed as their indigo child.

But Lena's talent develops as fast as she does.

Soon, she begins to exhibit strange, unexplained abilities. An expensive Waterford crystal goblet in Lionel's hand explodes when Lena has a tantrum. Once, Lillian walks into her playroom to find Lena having tea with her dolls, and when Lillian enters, all heads turn to her. Lena's and all four of her Madame Alexander dolls.

Her intellect begins to surpass what defines “normal” intelligence. She predicts and successfully foils an assassination attempt against Lionel. She prevents Lex from getting hit by a driver in a car chase five blocks away.

The last straw comes when Lena finds out that the cleaning lady's five year old son has cancer.

Lena convinces Alma to take her to see him. Five hours later, a tearful Alma brings the little girl back with something akin to wonder in her eyes. "Your little girl is an angel, Mr. Luthor. Bendecida por la Virgen. She cured my Carlos! She took away his sickness! Ella es un milagro de Dios!”

However, far from seeing it as a miracle, the Luthors circle the wagons. The next day, Lena finds out Alma has been dismissed, and a shift occurs in the Luthor household.

When Lena's abilities were within the parameters of "normal", they were good, something to be proud of. But now that her gifts have proven to be beyond that, they become alien, freakish. Something to be hidden. People would be asking too many questions, and Luthors do not permit those.

Suddenly, instead of being lauded for what she is able to do, Lena is now scrutinized and examined to find out what's "wrong" with her. It begins to strain the family that is obsessed with order and perfection.

They take Lena to various doctors and put her through all sorts of tests, but none of them seem able to find an explanation for Lena’s strange abilities.

Until they meet Rhea, an educator who runs an exclusive facility for “gifted” children.

An elegant and well-spoken woman, Rhea seems fascinated by Lena. Her teaching “methods” seem vague, but out of all the specialists Lena has seen so far, she is the only one who seems to understand and make a connection with her. At the very least, they seem to speak the same language. Rhea knows about this Matrix Lena has been talking about.

Rhea asks Lena if she wants to find out what the Matrix truly is. And when Lena agrees, Rhea takes the little girl to the Oracle to confirm her suspicions that she is a Potential.

Lena is taken to a tall building, riding all the way to the top floor with her little hand in Rhea’s. On the 64th floor, they enter a glass office in which an imperious looking blond woman sits, watching her with a piercing eye.

“Leave us.”

The woman orders sharply, slanting a glare at Rhea. She is at least 6 inches shorter than Rhea, even in heels, but her tone and her face brook no argument. Rhea retreats with a seething sneer, but she complies.

“Now, you,” the woman turns to Lena with a dark look and a raised brow. It fails to intimidate Lena, who has lived with Lillian Luthor’s pointed glares for the past three years of her life. “Do you know why you’re here?”

Lena merely blinks at her. “Because I know things.”

The woman scoffs. “So do I. Doesn’t make you special.” She gestures around her at her office with a spectacular view. “I know things too.”

Lena’s eyebrows rise as well. “Not everything.”

The woman’s glare intensifies, but Lena stares her down. After a moment, a corner of the woman’s mouth lifts, and she barks out a laugh. “You’re a smart one, aren’t you?”

Lena clasps her hands behind her back. “So I’ve been told.”

“Do you know who I am?”

Lena nods. “You’re the Oracle.”

The woman snorts delicately. “Did Rhea tell you that?”

Lena regards her solemnly. “She didn’t have to.”

The woman’s eyes narrow at her, but Lena says nothing more. She is scrutinized for another moment before the woman smirks. “Alright. Since you’re so smart, why don’t you tell me what you already know.”

Lena blinks at her, responding to the woman’s scrutinizing gaze in kind. “I know that you’re not human.”

Another laugh, this time louder. Piercing blue eyes gain a twinkle of mirth. “Very good. What else?”

“I know that you’re not real.”

The woman scoffs disdainfully. “Real is an abstract concept.”

“I know that I’m dreaming, and none of this is real.”

The mirth suddenly vanishes from the woman’s gaze, and her blue eyes stare at Lena intently. “What do you mean?”

Lena sweeps her little arms across the room. “This. All of this. Everything. It’s not real. It’s just a dream.”

The woman is leaning forward now. It looks to Lena as if she is holding her breath. “And what makes you think that?”

Lena chews thoughtfully on her lower lip. “Have you ever read Plato’s allegory of the cave?”

The woman’s eyebrows rise and an amused smile dances over her lips. “Of course.”

“It feels like that. Like the people chained to the walls of the cave, watching just shadows and reflections. Other people — even my parents, even Lex — they look around them and think that this is the real thing. But all we’re seeing are just shadows. Sometimes it makes me feel confused and blurry, like I’m dreaming, but I can’t wake up.”

The woman hums and her hands form a steeple under her chin as she continues to observe Lena.

"In the story, the prisoner who is freed into the sunlight was angry and in great pain after being in the dark for so long. Why would they go through that? Why not stay in the comfort of the darkness that they’ve known all their lives?”

Lena’s gaze doesn’t waver. “Because they would finally know the truth. They wouldn’t be living in a lie anymore. They would be free.”

A smile spreads across the woman’s face, and the nod she gives is almost approving. “Is that what you want?”

“Only if you tell me the truth.” Lena nods solemnly. “Will you tell me the truth, Oracle?”

“I’ll tell you everything you need to know.” The woman chuckles. “And one more thing. Call me Cat.”

Despite their animosity toward each other, both Cat and Rhea decide that Lena is more than ready for extraction.

The only problem is that Lena, at 6 years old, is one of the youngest children to be extracted so far. Because she’s so young, it’s decided that her family should be brought with her too. Lex, by then a teenager, is given a choice: to stay in the Matrix, or go down the rabbit hole, as it were.

Lex chooses to follow his family, and the Luthors are extracted by Rhea. They are brought on-board her ship, the Daxam. All four Luthors are taken to Zion, and told the truth about everything — the lie of the Matrix, the human harvest fields, and the fact that there is no going back.

That’s when it all goes to hell.

Lionel barely lasts three months.

Unable to accept the truth that his life of power and control was all a lie, and unwilling to believe that he now exists in a world where his name holds no weight, he somehow escapes Zion and finds his way to a human pod to try to inject himself back into the Matrix.

They search for him for weeks, and eventually they find him in the pod, impaled on the metal breathing hose stuffed into his mouth with the end sticking out the back of his head.

Lillian lasts longer, but this is no comfort.

Torn from her privileged life, her resentment begins to build and build, as she’s forced to accept her new reality.

Her perfect life was stolen from her. The high-paying job, the distinguished career, the unlimited influence, the beautiful house, the comfortable lifestyle — all gone. All apparently just a dream.

And now, Lillian has woken up to the dirt and drab and heat and toil of Zion’s underground, with nothing to show for her former life but the daughter she didn’t even ask for. The same daughter who is the very reason she’s trapped here now with no chance of going back.

She refuses to reconcile with her new reality, but she is no weakling like her husband. Instead, she lets the ugly, bitter ire fester inside her over the years, until it finally comes out.

One night, Lillian enters the rough, tiny cave that has become her unwilling home, creeps into the alcove carved into rock where her teenaged daughter sleeps and pours acid over her.

Lena’s screams wake others in the neighboring dwelling, and healers are immediately dispatched to tend to her wounds. Thankfully, Lena was turned away in her sleep, and the burns were limited to her back.

By the time her condition is pronounced stable, Lillian is gone.

Without her parents, Lena is taken in by Rhea to live with her, her husband Lar Gand and their infant son, Mon-El.

Rhea keeps Lena very close, almost jealously so. She prizes the young girl above all else in their household. Most of her time is devoted to teaching Lena, training her using the fight simulations and programs on the Daxam, instructing her on how to pilot the ship.

For Lena — who had grown up under Lillian’s growing resentment and bitterness, who had just survived a horrific attack on her by her own mother — Rhea is a godsend. Under Rhea’s maternal affection, Lena thrives. She pushes her own limits during her training, masters techniques with unparalleled speed and unerring accuracy, devours knowledge programs downloaded into her mind every time she’s plugged in. She blooms under Rhea’s freely-given praise, and works harder, starved as she was for acknowledgment and affection over the years.

As Rhea’s son, young Mon-El, grows up without displaying any unique abilities, he is often shunted to the side. Despite their age-difference, Lena makes a conscious effort to spend time with him, to give him the same nurturing Rhea is giving her.

She teaches Mon-El how to make repairs to the ship, explains how the thrusters work, how the pads keep the ship in balance. He’s most fascinated by the robotic armed exoskeletons that are kept at the dock for the city’s defense. He often asks Lena to take him to the bridge to watch them, and the two of them watch the exoskeletons being loaded, Lena leaning on the top rail, and Mon-El perched on the middle one, his skinny legs swinging in the air. As Lena smiles, the young boy boldly tells her that one day, he’ll pilot one of those.

It feels… nice. Almost like having a brother again. It feels like a second chance

After all, her own brother — well, that bridge was burned a long time ago, and Lena tries not to think about it.

But it’s hard to forget when she sees him all time, a nightmare come to life, whenever she’s plugged into the Matrix.

Lena will never forget the first time she saw her brother there.

Lex had abandoned them, had left his mother and sister in Zion years ago, as soon as he was of age. She’d tried to find him, had spent weeks, months, looking for him, to no avail.

Finally, Lena had been forced to accept that Lex had met their father’s fate. He could’ve been attacked by sentinels, gotten lost in the mechanical sewers, or worse, attempted the same thing Lionel had.

Either way, the result was the same, and the guilt and pain of it had been agony, but Lena had accepted it.

Until the day she met the Agent.

Most agents were already nigh indestructible, with their speed and brute strength, not to mention the internal communication they kept with each other through the program.

But this one… this one stayed on Lena’s tail with a dogged, malicious ferocity that she couldn’t shake off. It had been dangerously close several times already as he chased her throughout the dark, rain-soaked city streets. She couldn’t get a good lock on him, and it was all she could do to follow Jack’s instructions to the nearest extraction point.

Lena’s almost there, sliding into the booth, hand outstretched to grab the phone — when she sees it.

The Agent wearing her brother’s face, a feral smile stretching his lips as his fingertips brush the corner of her dark coat. The grin turns into a snarl as Lena lifts the phone to her ear, and he misses her by a millimeter.

It had been only a second, but… it was Lex.

Lena was sure of it. So sure that she had spent months hacking into the system with Brainy’s help, trying to find out what the hell was going on.

It takes six months of hacking into the mainframe to discover the truth. Lex had succeeded where their father had not. The son had surpassed the father.

Not only had Lex somehow managed to get himself reinserted into the Matrix, the anomaly of his presence in the code had also caused a glitch in the system itself.

It takes another encounter with Lex — in his new regalia of a generic black suit, bland tie and FBI-issued sunglasses — sneering at her as he points a gun at her head, to realize yet another knife-wound truth.

Her brother has become a virus in the Matrix.

________

Kara’s experience in the Matrix could not have been more different from Lena’s.

More than a decade before Lena was born, Kara Zorel was like any normal thirteen year old girl. She went to school, hung out with her friends, had a crush on the boy living next door. She got straight A’s, and volunteered at the local senior home.

Her quicksilver mind that could spot things others couldn’t was easily considered as part of her intelligence. She was a very smart girl, after all. Her obsession with puzzles and codes was easily filed away as a quirk or a phase she was going through until she found a new hobby.

Everything about her life seemed to be on track to become ordinary, until the day of the accident.

At least, they told her it was an accident. Kara doesn’t remember any of it. All she really remembers is waiting for a train at a subway station. She remembers her father mentioning a Trainmaster who would take them away, somewhere new. To a new home, her mother had said. [This is from the 3rd movie]

And then nothing.

Kara thinks she must have been dreaming, because she can remember being left alone in that subway station — the walls were blank and a sterile white, with nothing to indicate the presence of life except Kara herself sitting on the otherwise empty bench. She can remember the feeling of waiting, waiting endlessly for the nothing that would come — no trains, no other passengers, no one else at the station with her. She can remember running along the platform tirelessly, only to end up in the same place she’d started from. She remembers the feeling of being left behind and trapped and scared. Mostly scared.

And then the next thing she knows, she’s awake on a hospital bed with Eliza Danvers sleeping on the chair next to her.

The Danvers had found her on the train platform, curled up, unconscious, on the same bench she’d dreamed of. They’d thought she was a runaway, or a missing child, but the FBI agents who had come to Kara’s hospital room had told her that her parents were dead.

An accident, they’d said. A subway malfunction that had taken out a whole car. Under investigation, the man in sunglasses and a dark suit had reassured Jeremiah and Eliza in a monotonous voice.

With no one to claim her, no other family to speak of, Kara is taken in by the Danvers. They’re good people, kind and understanding when Kara wakes up in the middle of the night with nightmares of being trapped in a white sea of nothingness.

When Kara wakes up crying and sweating, Eliza is there to soothe her and rock her in her arms until she fell asleep again. When she tells Jeremiah that everything is too loud and bright, he sits her down and teaches her to calm her thoughts and meditate.

Alex, who had gone from being an only child to having an anxious, high-maintenance little intruder in her room, is less than happy about the situation. She keeps her distance, and gives Kara cold glares from across the bedroom or ignores her completely.

Until one night when Alex sneaks back into their room from the concert she’d snuck out to earlier, and finds Kara sitting on one corner of her bed with her knees curled up. With Alex gone for most of the night, Kara had been alone and had refused to fall asleep, terrified of having nightmares again.

With only a little bit of grumbling, Alex tosses all their pillows and blankets onto the floor, and drapes one of her sheets over both their beds to make their first blanket fort. The first of many.

Curled up on the floor next to Alex, Kara sleeps soundly through the night for the first time since waking up without her parents.

Still, despite slowly settling in with the Danvers, Kara can’t shake the feeling that something is off.

It feels as if everything around her is just a little bit off-kilter. As if the world had somehow changed in the time she’d been unconscious. Or maybe she had. Either way, it feels as if both Kara and the world around her know on some level that she’s not supposed to be here. Perhaps it’s because she was meant to die along with her parents. But by some unknown anomaly, here she is, half of her present, half of her straining to join her mother and father wherever they are.

It’s not a reflection on the Danvers. Kara couldn’t have asked for a better family to care for her. And she cares for them too. Over time, Kara gains a sister she would die for in a heartbeat, instead of a roommate who barely tolerated her presence when she first arrived. Her definition of ‘mother’ slowly expands and makes room for Eliza in her heart. She finds a man to respect and admire in Jeremiah.

Still, the feeling of being out of place persists throughout the years, always in the back of Kara’s mind.

Tragedy strikes when Jeremiah disappears.

It happens quickly, too quickly. One day her foster father is there, the next he’s gone. The only clue the police get is the last voicemail on Jeremiah’s phone.

The message starts with Jeremiah’s voice, reminding Alex that he’ll be picking her up from softball practice later, then it cuts off abruptly without warning.

Ten seconds later, another voice is heard through the other end, this time a smooth monotone. It sounds nothing at all like Jeremiah, and it sends a chill down Kara’s spine.

“The Luthor girl escaped again. She has eluded us one too many times for a human. She cannot avoid the inevitable…. Send the Brother. Next time, she dies.”

Nothing is found at the scene but Jeremiah’s phone. No evidence, no ransom note, no explanation for the strange message, nothing to trace, nothing to at all to suggest that Jeremiah Danvers was there. The blank-faced FBI agents offer no sympathy when they inform Eliza of the news in a smooth, apathetic monotone.

[[In case it’s not clear, Jeremiah got turned into an agent by the other agents who were chasing Lena during one of the times she was plugged into the Matrix]]

Their little family is shocked and reeling, but they cling to one another in their grief. Kara remembers something her mother always used to say. Stronger together, Kara. Life is hard, and we cannot face it alone. We must be each other’s strengths. We are always stronger together.

Still, life goes on. Keeps moving on, even after tragedy and loss. Sometimes, Kara feels as if the world is in constant motion, its inertia having no time to waste on a young girl who feels as if she has been left behind.

The sense of alienation increases, and Kara is diagnosed with depression. Which only serves to increase her family’s concern, and puts a near-permanent look of worry in Eliza’s eyes.

So Kara puts on her brightest smile and hugs her foster mother. She talks more, smiles wider, laughs louder, and makes more friends to go out with so she’s not at home alone in her room which no longer has Alex in it.

Alex goes to college, then med school, the chip on her shoulder large enough to be seen from space. She’s determined to find out what really happened to her father, and Kara knows how stubborn she is.

But she only really finds out how serious Alex is when her older sister declares that she’s joining the FBI, and no amount of talking from either Kara or Eliza can dissuade her.

And it’s not as if Kara has a leg to stand on. At least Alex has a purpose, a direction. Meanwhile, Kara has no idea what she wants to do with her life. She meanders around after college, a little bit lost and floundering. She’s intelligent, her professors said, but she lacks focus.

Eventually, she gets hired at Catco as an assistant to the big boss herself, Cat Grant.

All of 5’4” in heels, the woman herself strikes fear into the heart of every intern roaming the halls. It’s impossible not to snap to attention when her private elevator dings and she steps out. Each click of her heels is a reminder of the power she wields, and honestly, Kara is a little terrified of her.

But she straightens her spine and her glasses, tucks her hair behind her ear, and refuses to be cowed.

And it’s as if Miss Grant takes it as a challenge to break her, because her demands become more and more unrealistic, more and more impossible. But something inside Kara tells her not to back down, to stare her right back, and wait her out. Cat Grant is a puzzle, and Kara has always been good at puzzles.

The key comes in the form of Carter Grant.

Cat tasks Kara to pick her son up from school one afternoon, and Kara finds the young boy waiting for her right outside the school gates. He’s a very sweet boy, a little shy, but he eventually tells Kara about this comic he’s been reading about a young superhero named Supergirl.

As he begins to brighten up talking about his new favorite character, Carter doesn’t notice the car coming from the other side of the street. Neither does Kara at first. But something inside her tells her to turn around.

Maybe it was a sound, an instinct, and unconscious observation too quick for her mind to consciously process. Whatever it was, it had her turning just in time to see the car heading straight for Carter.

She barely has time to pull the boy back to the sidewalk, and the car almost clips him. Almost.

“Are you okay??” Kara hurriedly checks Carter for any injuries or signs that he’s shaken up. Other than the boy’s wide eyes, he seems to be fine.

“That- that was amazing! You were so fast, Kara! You were like Supergirl! How did you do that?”

As they walk back home, Cart gushes about how awesome Kara’s save was, how she was as fast and strong as Supergirl. Kara laughs it off, but the relief that the boy is okay lingers.

The second the front door closes behind Kara, Carter pulls out a phone and scrolls through the contact list until he finds ‘Mom’.

When Cat answers, he whispers excitedly into the phone. “She did it! She was even faster than Lena by 0.02 seconds!”

“Good. Did she say anything else?”

“She mentioned her sister. Are you going to tell the Manhunter? Is J’onn going to pull them out? Or maybe Lena can come? I like it when she comes to visit.”

A rustle of paper in the background, and Cat drawls in an almost bored voice. “Not yet. She’s not ready.”

[[In this AU, Carter is a computer program designed to assist the Oracle. Kinda like Seraph in the movies. He and Cat have a very unusual relationship. He was just supposed to be a simple program to help ward her, but he was designed to be charming in an innocent and disarming way to help distract from his real purpose. Cat developed a fondness for him, so when he tries to protect her when she’s in danger, she ends up shoving him behind her and protecting him.]]

On the anniversary of Jeremiah’s disappearance, another tragedy rocks the Danvers family.

Alex Danvers disappears.

Eliza is inconsolable, but Kara… Kara is numb, at first. Denial is always the first instinct of the human mind when a shock is delivered to its system. There’s talk of a search, trying to find out where she might have gone, her usual routine, any places Alex frequents — it all rolls over Kara’s head. They’re looking for a body, but that’s not how Alex is gonna be found.

Unlike Jeremiah’s disappearance, Alex’s is not without a trail. She is an FBI agent after all. There will always be a trail, and like in most FBI cases, it can be found in the absence of one.

In this case, it’s Alex’s computer. It’s missing.

The more Kara thinks about it, the more it galvanizes her. Kara knows Alex, knows her quirks and her habits. She didn’t have many friends outside of work, mostly people from med school she’s since lost touch with. No, anything that happened to Alex would be connected to her work, and Alex kept all her work files in that computer.

She throws herself into finding it. Find it, and she finds Alex.

For months, Kara follows every lead, every loose thread she can find, all in the hope of finding the computer. Every time she comes across a dead end, she doggedly retraces her steps until she can find another lead. The chalkboard in the kitchen that used to house her grocery list desk becomes a list of all possible locations. Her desk at Catco is a disaster of papers and post-it notes — a receipt from Cat’s dry cleaners here, the number for Annie Leibovitz’s assistant there, and Alex’s bank statements piled on top.

All the while, Cat watches her. Observes her tenacity, her ability to find patterns that no one else would’ve noticed, her keen attention that allows her to find details that other people would’ve ignored.

Finally, after nearly a year of looking, Kara finds Alex’s computer in a security deposit box under the alias Alice Liddell.

It takes her all night, but Kara manages to gain access to Alex’s documents. She finds file after file on Alex’s investigation into Jeremiah’s disappearance. Articles on similar disappearances all over the world. Some incidents are identical to Jeremiah’s, some with more of a trail. The victimology is all over the place, but in certain cases, there is a disturbing pattern.

A number of the disappearances occur in National City, and nearly all of them have one thing in common. They’ve all been patients or relatives of patients at the Luthor Family Hospital — a stroke patient and his fiancee, a woman in a car accident, a man with a gunshot wound, an old lady with Alzheimer's and her widow, even three children from the cancer ward and one of their mothers. Most of these people were deceased, but there must have been some reason Alex thought otherwise. And if she was right, then there is something very disturbing going on in the Luthor Family Hospital.

Kara keeps searching the files, and finds a certain devolution in Alex’s notes. Towards the end, she seemed more and more disorganized, her thoughts more and more disjointed. And Kara feels a terrible sense of guilt at not noticing what her sister was going through.

Throughout the files, she finds multiple references Alex made to something called the Matrix. She stumbles upon a mess of a pdf that she’d originally thought was gibberish, but upon closer inspection actually more closely resembles computer code. And in the middle of the unintelligible tangle of letters and symbols, she finds a question.

What is the Matrix?

Just as Kara is trying to make sense of the question, a new message alert appears in Alex’s inbox. Kara stares at the screen. It originated from Alex’s own email. Frowning, she clicks on the message, and her eyes widen as she reads.

I’m alive.

Kara springs forward so fast, she almost dislodges the laptop from her kitchen counter. She tries multiple times to reply to the message, but nothing happens. Kara growls, and almost as if the computer can sense her frustration, another message appears.

I’m alive and I’m out.

Kara’s brows furrow. What? What the hell?

The Matrix still has you, Kara.

Kara’s frown deepens and she looks around her, checks the computer. Is this some kind of prank?

I’m sorry I had to leave, but you can’t follow. Not until you’re ready.

Ready for what, Kara thinks.

Ready to give it all up. Ready to wake up. You told me once that you felt like everything since you woke up in the subway station has felt strange, like a dream. You were right, it is. And you’ll find me, if you’re ready to wake up.

Kara’s jaw drops in shock.

Follow the white rabbit.

The message flashes across the screen for a moment, then the monitor goes black. Kara snaps it shut and pushes it as far away from her as she can.

That — what was that? A-a trick? A hallucination brought on by the lack of sleep and her hyperfixation?

She could check it again, turn the laptop back on and click on the messages again — but suddenly Kara is gripped by fear, and denial feels more like a comfort.

She packs away the computer, stowing it under the desk where she can’t see it, and goes to bed. She doesn’t sleep until 3 AM.

But of course, Kara is no coward. She’s never been one to back down to her fears. In the morning, armed with a cup of Noonan’s coffee and a clearer mind, she opens the laptop again.

She doesn’t quite have the courage to check the messages yet, but she finds another article. This time, about the [head] of the Luthor Family Hospital, a woman named Lena Luthor.

It takes no time at all for her quick mind to make a connection, but it takes a while for the rest of her conscious brain to catch up.

Luthor. She’d heard that name before. In a voicemail, the only thing left of Jeremiah Danvers. “The Luthor girl got away again.”

Lena Luthor.

That can’t be a coincidence. Alex had been looking into their dad’s disappearance, and the Luthor name has already come up more than once, and now a female Luthor.

All the research she does on Lena Luthor comes up with next to nothing. Other than business articles and some papers in several scientific journals, there’s very little mention of the woman. So far, all Kara knows is that Lena Luthor is the CEO of one of the leading tech companies in the world, dedicated to providing accessible technology and communication devices to billions of people all over the globe — their new L-Phones are popping up everywhere. She’s also apparently a brilliant scientist and researcher, invested in scientific research to help prevent and cure diseases. She also owns and is directly involved in the running of the Luthor Family Hospital, a facility known for innovative and experimental medicine.

And for all of her work and accolades, there has never been a single photograph of this woman past the age of 6. Nothing. This woman’s image has never been recorded in any way, in any kind of media, in any event, in all the years that she has been running L-Corp. How is that even possible?

Now, Kara’s definitely suspicious.

Three days after the computer is found — plenty of time for thinking, but not too much time to do something stupid, she thinks — Cat makes her move.

She summons Kara to her office and delivers her ultimatum, in the form of an offer.

“Y- You think I have what it takes to be a reporter?”

“You’re an intelligent woman, Keira. But more than that, you can see things others can’t. You observe far more than people give you credit for. You could have a bright future here at Catco.”

Cat surveys her intently over her glasses. “It’s your choice. You can take the job, or you can keep wasting your life going down this rabbit hole.”

Cat gestures toward Kara’s messy desk, but again Kara’s quick mind gives her a nudge. That’s the third reference she’s heard in as many days. Rabbit hole. Alice. White rabbit.

Kara asks Cat for time to think about it, but really, she’s already made her decision. She uses her connect as Cat’s assistant to set up an appointment, introducing herself as Kara Danvers from Catco, writing an article about the Luthor Family Hospital.

The assistant confirms that Miss Luthor would be delighted to give Catco a glimpse into the facility to bring awareness of the work they do, and confirms the time.

When Kara arrives, she is directed to the children’s cancer center. When she sees the whimsical mural of a white rabbit hopping along a trail on the walls, she knows she’s at the right place.

Kara follows the mural until she reaches a room at the end of the hall. A soft feminine voice floats down the hallway and reaches Kara’s ears.

“To begin with, tell me, do you think that these men would have seen anything of themselves or of one another except the shadows cast from the fire on the wall of the cave that fronted them?

How could they, he said, if they were compelled to hold their heads unmoved through life?”

Kara walks closer, drawn to the sound. She stops just outside the door to what is clearly a child’s hospital room. A little girl in white pajamas and a colorful bonnet sits cross-legged in the middle of the bed, listening to the dark-haired woman sitting on the chair by her side. The woman’s back is turned to Kara, but she can see the book she’s reading from. Plato.

“By Zeus, I do not, said he.

Then in every way such prisoners would deem reality to be nothing else than the shadows of the artificial objects.”

“Quite inevitably.” The little girl on the bed quotes with a smile. Kara hears a soft, amused hum from the woman.

“Consider, then, what would be the manner of the release and healing from these bonds… When one was freed from his fetters and compelled to stand up suddenly and turn his head around… and lift up his eyes to the light, and in doing all this, felt pain…”

Kara sees the moment the reader realizes that she’s there. The woman’s head turns just the slightest, and Kara can see her sharp, elegant profile silhouetted in the light. She keeps reading, but at this point, they both know she’s aware of Kara’s presence. Kara continues to listen silently.

“What do you suppose would be his answer if someone told him that what he had seen before was all a cheat and an illusion… But that now, being nearer to reality and turned toward more real things, he saw more truly?”

Just then, the little girl’s eyes snap up to meet Kara’s, and big black eyes blink owlishly at her. “Miss Lena, we have a visitor.”

The woman finally turns, and Kara gets her first glimpse of Lena Luthor. Cut-glass green eyes are perceptive as they take Kara in, and a small smile plays on the corner of red lips.

“So we do, Zuri.”

She sets the book down on the bed beside the child and rises from her seat, a pale hand extended. "Kara Danvers, I presume?"

It takes Kara a second to reply, unable to take her eyes off the woman. There’s something arresting about her, something that could probably stop anyone in their tracks. Even the way she tips her head to survey Kara is fluid and mesmerizing.

Clearing her throat, Kara takes Lena Luthor’s proffered hand. “Yeah – uh, yes.”

The woman's smile grows. "I've been expecting you."

For a moment, the words make Kara's stomach flutter, then the 'duh' moment hits her. Of course she'd been expecting her, they had an appointment. Kara's face flushes red. "I've been looking forward to meeting you, Miss Luthor."

Green eyes gain a look of amusement and crinkle at the corners. Lena Luthor looks as if she has a secret, or like she’s in on a joke Kara doesn't know. "Not as much as I have, I'm sure."

Kara's brows furrow in confusion, but before she can ask the woman what she means, the Luthor bends down and kisses the top of the child's head, before heading out the door and gesturing for Kara to follow.

[[I just love the idea of Lena reading the Allegory of the Cave to the children like she did when she was a kid, as her way of preparing them, a way of telling them that yes, extraction will hurt, it won't be easy to accept the truth, but they will be free].

[Also in this AU, the extraction points used to be the pay phones like in the movie, except those got phased out once the machines figured out that’s what the resistance was using. So Lena developed the L-phones, and made it so one would always be easily accessible. That’s the work she does at L-Corp]]

After their tour of the hospital concludes, Lena watches Kara walk out through the double doors, throwing a friendly wave behind her. As soon as she's out of sight, she pulls out an L-phone.

"Well, she’s persistent, I'll give you that."

"Told you. Who do you think she got it from?”

“I see stubbornness runs in the family.” Lena hums in amusement.

A chuckle from the other end of the line. “You have no idea.”

"How close is she?"

Alex’s voice turns business-like. "Well, she’s made the connection to you, and Kelly’s seeing some sizeable fluctuations in the code, so I'd say she’s getting there. J’onn thinks she might be ready soon. He says she’s responding quickly for someone who hasn’t had as long to adjust. Sooner if you prepare her, probably.”

“That won’t be a problem.”

“Rhea,” Lena can hear the seething disdain Alex’s voice, and thinks her mentor is probably standing over Alex’s shoulder as they speak. “Would like me to remind you that the sooner we pull out my sister —“ Lena can almost see her glare at Rhea. “The sooner you can get back to the Daxam, and this can ‘all be over with’.”

Lena shakes her head. “I’m not pulling her out before she’s ready. The consequences could be disastrous.”

“Yeah? Try telling that to your Captain.”

They’re interrupted by an excited young voice. “Hi, Lena!”

“Mon-El?”

Alex snorts over the line. “Yeah, can you believe her? She brought the kid over just to get you to ‘speed things up’.”

“When are you coming back, Lena? I miss you! I snuck into the dock last week, but M’gann caught me. She said she’d teach me how to make shells if I promised not to go past the bridge again. And Imra asked if she could come with us the next time we go to the bridge to see the loaders, I told her yeah. That’s okay, right?”

Despite the seriousness of their situation, Lena can’t help but smile a bit at the young boy’s enthusiasm. “Of course she can. I’ll be back soon, Mon-El. Stay out of trouble, and do what your ranking officer says.”

“Okay, kid, you heard the lady. Go bother Brainy and Kelly at operations. It's about time you learn to read code anyway."

Lena can hear the boy grumbling in the background, but he obeys. As soon as he's out of earshot, Lena goes back to business.

“Start a trace for Kara's pod location, and standby. Be ready to plug in when I tell you to.”

"Copy. J’onn’s gonna try to get us as close as he can, but it's the fields. We can never be too careful. And Lena…? Try to make it easy for her."