#the haymarket affair

Text

This Day in Anarchist History: The Haymarket Affair

youtube

#submedia#history#161#1312#the haymarket affair#haymarket#class war#antifa#chicago#usa news#usa politics#usa#american indian#american#america#antifascist#antifaschistische aktion#antinazi#antiauthoritarian#direct action#activism#all cops are bastards#all cops are bad#anti police#anti colonialism#anti cop#fuck the gop#fuck the idf#fuck the police#fuck the patriarchy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Fake Labor Day, America...

And ofc it has conservatives calling for the murder of innocent labor right's activists...

#america#evil#right wing#capitalism#usa#republicans#labor day#haymarket#the haymarket riots#the haymarket affair#capitalists

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chicago Evangelist Who Held a Gospel Revival to Stop a Strike

Sojourners Magazine - May 1, 2023 - Matt Bernico (link here)

“Dynamite or Gospel” was the choice that some Christian evangelists felt they were facing in 1885. According to The Record of Christian Work, a journal that chronicled the stories of U.S. evangelists like Dwight L. Moody and Charles Spurgeon throughout the late 1800s, evangelists believed they had to intervene in the lower classes, or else these classes could be persuaded to join the ranks of socialists and anarchists, therefore throwing off the stability of major U.S. cities like Chicago. These evangelists were right to worry.

Just a year later, in 1886, one of the most important moments of U.S. labor history took place on May 4 in Chicago: The Haymarket affair. The Haymarket affair started as a rally for an 8-hour workday in the midst of a general strike but it all went sideways when a still unknown person threw a bomb into the crowds, leading to an eruption of violence from both police and protestors.

Historian Timothy E.W. Gloege explains in his book Guaranteed Pure that before the events of Haymarket, Christian evangelist Dwight L. Moody conspired with local capitalists such as Cyrus McCormick Jr., one of the managing partners of International Harvester Company, to thwart the 1886 strike altogether. Within the story of the Haymarket affair, we can find a number of political tensions that are still within Christianity today. One major tension still animating Christian discourse is this: What happens when Christians side with the wealthy instead of the poor and working class?

Chicago, in the 1880s, was the eye of the storm for the struggle between business elites and workers in the United States. The radical energy from the destroyed Paris Commune (a short lived radical working class movement that seized power in Paris) nearly 10 years earlier had carried across the Atlantic and emboldened the rapidly organizing working class in the U.S. In 1884, just two years before the Haymarket affair, Chicago’s working class gave the city’s capitalists an ultimatum: Give workers an 8-hour workday by 1886 or face a general strike.

It is important to understand that the workers’ demand was a direct response to the antagonistic actions of Chicago’s capitalist class — specifically, long work hours and gutted wages. Cyrus McCormick Jr. cut the wages of his workers and reinvested those funds into the mechanization of labor, simplifying the skill of the workers he required, and subsequently widening his labor pool. As a result, he drove wages down and made major profits off the backs of disgruntled and exploited workers.

As the deadline of the general strike grew closer and worker organizing became more militant, the message of evangelizers like Moody began to resonate with Chicago’s capitalist class. Much of Moody’s evangelistic career focused on developing a strategy of preaching the gospel to the unreached and rapidly radicalizing working class communities.

Moody developed a strategy for training “Christian workers” to reach the working class in ways that mainline Protestant churches weren’t doing. At the time, mainline Protestant churches insisted that evangelism was best left to trained professionals with seminary educations. So to have Moody, a layperson, create a program that trained working-class people to evangelize others within their own socioeconomic class didn’t sit well with professional clergy. This approach, Moody believed, would assuage the threat of impending socialist and anarchist uprisings. Gloege suggests that the increasing militancy of radical working class movements created panic among evangelical elites and led to Moody doubling down on his strategy of engaging the working class; Moody decided to expand to the East Coast.

Yet a number of setbacks, like a lack of funding and the inability for Moody’s New York Christian workers to connect with the working class, led Moody to abandon his work on the East Coast, causing him to return to Chicago in early 1886 where he would try again to expand his evangelism work and establish a training institute for Christian workers. Moody’s pitch to Chicago’s capitalists was simple: Based on the overarching fears of a threat to the stability of the capitalist social order, Moody sought $250,000 from Chicago’s businessmen to open an institution that would train people to evangelize to the working class.

Moody argued that “Christianity has been on the defensive long enough,” and “The time has come for a war of aggression.” Facing pushback from mainline denominations, Chicago’s business elites were slow to take Moody up on the offer and, in the end, didn’t give him the funds. Instead, they proposed he hold a week-long revival in May of 1886 to thwart the coordinated labor action and general strike.

The first night of the revival was a flop, and Moody mostly preached to empty seats; he implored the women in attendance “to bring to the meetings the men who [were] on strike.” But Moody’s words went unheeded, and the following day, on May 3, a crowd of 40,000 workers assembled at the gates of McCormick’s factory to protest their unfair treatment. Police confronted the crowd and killed four strikers, injuring many more. The day’s events led to a call for a protest the following day at Haymarket Square. Moody’s revival had failed to reach the workers.

Despite the failed revival and the chaos in Haymarket Square on May 4, Moody used the situation to his advantage by placing himself in the spotlight. Moody told the Chicago Daily Tribune: “I am not speaking disparagingly of the different churches and missions now attempting to reach this class, but anyone with their eyes open can’t fail to see that the masses are not reached. One of two things is absolutely certain: either these people are to be evangelized, or the leaven of communism and infidelity will assume such enormous proportions that it will break out in a reign of terror such as this country has never known.”

These words were in no way a departure from Moody’s previous position, but as Gloege’s work concludes, “It was only Haymarket that opened eyes, ears, and wallets. He [Moody] secured $250,000 and a board of trustees consisting entirely of prominent businessmen. Moody would go on to found the Chicago Evangelization Society, which would then be renamed to the Moody Bible Institute after his death in 1899.”

The use of Moody’s socially conservative evangelism by Chicago’s ruling class is a drastic example of religion being used as an opiate to subdue the masses in the most vulgar sense. Yet many Christians today are not far from Moody’s stance that religion should produce docile and complacent working people who have their eyes on heaven, rather than struggling for the rights of the working class in the here and now.

Christian financial “experts” like Dave Ramsey or prosperity preachers like Joel Osteen are proof enough. Beyond just those figures, there’s a whole cottage industry within more conservative versions of Christianity that give ethical tips to businessmen and apply Christian teachings to be a good capitalist — at the expense of the life and dignity of workers. For example, in 2020, Dave Ramsey went out of his way to shill for Southwest’s CEO while disparaging union workers as being “stupid” for advocating that the company meet the terms of their bargained contract.

But the type of Christianity that is wielded by financial elites and capitalist shills is not the only Christianity possible. On May 1, what’s known across the world as International Workers’ Day, is a day that Christians should remember that Jesus himself was a carpenter, a worker, not one of the bosses. Jesus’ teachings tell us that it's easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for the rich to enter heaven (Luke 18:25). In a time when organized labor is once again on the rise and CEOs are fighting back, Christians must resist the ways CEOs, capitalists, and their fan clubs appropriate Christianity for the oppression of working people.

Related links and notes below

Young Oon Kim on D.L. Moody (November 1973)

Born in 1837 in Northfield, Massachusetts, Moody was known affectionately as "The Commoner of Northfield."...Within days of his conversion, Moody was in Northfield, trying to kindle the faith of his family...Moody decided in 1875 that Northfield would be his new base of operations for the world mission which had fallen to him.

Seeing the need for high school training for Christian work and everyday living, he founded in 1879 Northfield Seminary, a girl's secondary school, and later in 1881 Mt. Hermon, a similar school for boys...During the summers when the girl's school was empty, Moody held conferences in the buildings. The Northfield Conferences were wonderful gatherings of Christians from America and Britain, and were sources of great inspiration.

Frank Buchman of the MRA was organized by Moody’s organization (Revivalists: Marketing the Gospel in English Canada, 1884-1957 By Kevin Kee)

Buchman was intensely pietistic. He had longed to be a minister since childhood and, after secondary school, he attended Mount Airy, a Lutheran theological seminary in Germantown, Pennsylvania. More influential in his spiritual development, however, were his summers in Massachusetts at the Northfield Student Conferences organized by evangelist D.L. Moody. Athe the end of the nineteenth century, at conferences like Northfield, conservative and liberal Protestants worked together to achieve their common goals of converting individuals and Christianizing society. Buchman's theology was formed by the evangelicalism at Northfield.

Recent Union Wins Mean It’s Time for More Organized Religion

Ford OKs Missionary Use By CIA, Hatfield Opposes It (1975)

Say NO to Revival

Magazine Says Tim LaHaye Received Help from Unification Church (1986)

The Unification Church Seeks Influence, Acceptance Among the Political ”Christian” Right (2009)

Evangelicals unaware inaugural event was sponsored by Unification leader (2001)

An Outline of Moon’s Friendship with Jerry Falwell

Moon at the National Prayer Breakfast

Christian Nationalism is Authentically Christian - And According to a New Poll Most White Evangelicals are Supporters

#evangelicalism#evangelism#revival#christianity#religion#labor organizing#anti-leftist#anti-labor#capitalism#history#chicago#The Haymarket affair#anarchism#socialism#anti-capitalism#workers#anti-worker

1 note

·

View note

Text

A friend told me once about one of his professors back in college. She was from South America and taught history here in America. So as a historian, she was exited about a trip to Chicago because it's where the infamous Haymarket Massacre occurred; a bloody incident of labor agitation, police violence, rigged trials, and political persecution that is apparently very well known where she's from.

Imagine this historian's surprise when she found that most people living in the Chicago area have never heard of the Haymarket Massacre or the wider history of Chicago's labor movement. That it's a much more famous story in her country than in the place where it actually happened.

Whenever I remember this I'm really just struck by how much this encapsulates Americans' relationship with their own history.

#History#American History#Haymarket Massacre#Haymarket Affair#Labor Rights#Labor History#Education#Whitewashing

767 notes

·

View notes

Text

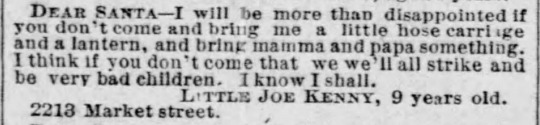

(source: The St. Louis Post Dispatch, December 22, 1887.)

#this was written in the immediate aftermath of the haymarket affair trial#which I suspect was giving young comrade kenny ideas#direct action#kids#dear santa#christmas#1880s#victorian#missouri#st. louis#haymarket affair#labor history

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy birthday to all workers and also to all anarchists

#gonna re-listen to the podcast on the haymarket affair I think#it’s very good#it’s ‘cool people who did cool stuff’ it’s their episode on it

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

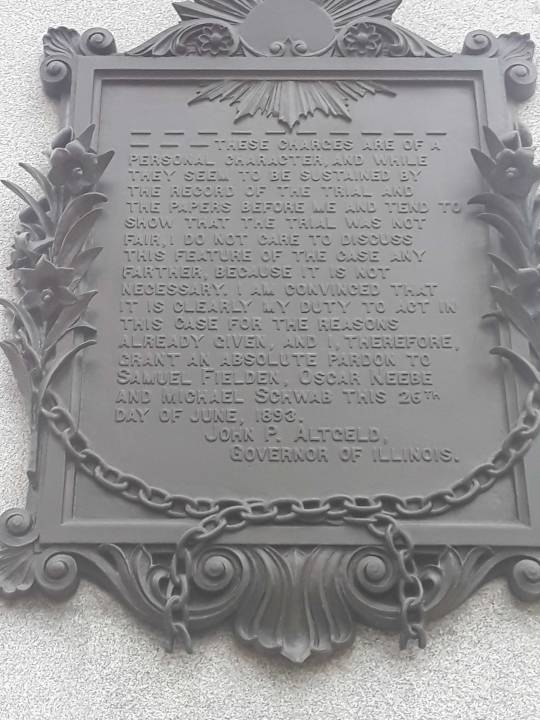

I went to see the haymarket martyrs' memorial

#chicago#forest park#forest home cemetery#cemetery#graveyard#haymarket affair#haymarket#haymarket martyrs memorial#memorial#michael schwab#oscar neebe#samuel fielden#august spies#albert parsons#adolph fischer#louis lingg#george engel#lucy parsons#mark rogovin#frank a pellegrino#bessie pellegrino#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist#communism#socialism#international workers day

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Day in Anarchist History: The Haymarket Affair

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

today is my one year anniversary of working as a lawyer 👍

#it’s so funny that my first day on the job was on Labor Day which isn’t recognized in the US#and I live in Chicago aka where the haymarket affair occurred lol

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Only a week until Labor Day?

Where did this summer go? Next Monday is Labor Day already! It’s the un-official end of summer – but what do you know about Labor Day – other than it’s a good excuse to have a party or cook-out?

Labor Day has some of its roots in the Haymarket Riot of 1886 in Chicago. So definitely NOT a party. And as the word riot implies, there was violence and several deaths. On May 4, 1886, workers from the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"We must now turn to Captain Michael J. Schaack, who dominated the stage after the bombing. In the wake of the bombing, he was assigned to assist the state prosecutor, develop his case, and bring to justice others who were implicated. Schaack may well be called the founding father of modern police anti-radical theory and practice: his operational methods, ideological assumptions, exploitation of mass fear, and use of publicity together form a legacy that became the foundation of a police specialtyin subsequent years.

Subsequent to the bombing, Schaack’s men (they were frequently referred to as his ‘‘boys’’ - the singular, ““Schaack’s man,’’ was used for a close associate, an agent or alter ego) commenced a terror campaign during which well over two hundred sixty individuals were rounded up. They raided and ransacked homes, made illegal arrests, dragged people out of their beds, subjected dragnet victims to intimidation and torture, and bribed several into becoming prosecution witnesses. The justification offered for these tactics was a claimed vast revolutionary conspiracy targeting the city and, ultimately, the nation. One of the hired Pinkerton agents subsequently wrote: ‘The false reports written about anarchists as told me by the writers themselves would make a decent man’s blood boil’ (C. A. Siringo, Two Evil-Isms, Pinkertonism and Anarchism [Chicago: C. A. Siringo, 1915], p. 3).

The Chicago Citizens’ Association and its allies raised funds used by Schaack to bribe witnesses and pay off informers. In addition, it apparently hired Pinkerton agents to assist the police,’ raised over $30,000 to succor the families of the dead and wounded policemen, donated land to the federal government to be used “for military purposes,’’ that is, as a redoubt for rapid troop deployment without delay when needed to curb disturbances in the city, and subsequently, in 1899, collected funds to build an armory for the same purpose.”

As the city writhed in fear, kept at a high pitch by a frenzied press, Schaack took center stage as a detective-hero, casting himself in the role of master detective, a figure that in the nineteenth century gripped the popular imagination, whose daring and skill would unlock mysteries and bring him acclaim as the man who had not only solved ‘‘the crime of the century” but rescued the city and nation from destruction. How could his vision be marred by such piddling details as apprehending the actual bomber? Instead, he bragged unceasingly of his cleverness and courage in rooting out secret conspiracies, confident that no one in the fear ridden city would dare challenge his boastful disclosures, however absurd or incredible.

This self-styled master detective left no stone unturned to keep himself in the public eye. Not only did he falsely announce the discovery of bombs, but he actually sought to set up anarchist cells on his own. Three years after the bombing, on May 10, 1889, Police Chief Frederick Ebersold told the Chicago Times in an interview:

Captain Schaack wanted to keep things stirring. He wanted bombs to be found here, there, all around, everywhere. I thought people would lie down to sleep better if they were not afraid their homes would be blown to pieces any minute. But this man, Schaack . . . wanted none of that policy. . . . After we got the anarchist societies broken up, Schaack wanted to send out people to organize new societies right away. ... He wanted to keep the thing boiling, keep himself prominent before the public.

Ebersold’s charges were probably prompted by Schaack’s attack on him in his book Anarchy and Anarchists, published in February 1889, sixteen months after the Haymarket executions.' This volume was prepared to advance Schaack’s career as a master anarchist hunter and to exploit his national reputation as the hero of Haymarket, and it was circulated by the Pinkerton Agency to induce employers to engage its services. The exaggerations and inventions in the book — admitted by Schaack himself later to be (at least) one-third lies — also reflect the narrative strategies of nineteenth-century police thrillers, and they are clearly intended both to sow and to exploit mass fear. The book is a handsome volume of 697 quarto pages, with 191 illustrations (a great many bomb-related), and its title page blazes with three subtitles: A History of the Red Terror and the Social Revolution in America and Europe; Communism, Socialism and Nihilism, in Doctrine and in Deed; and The Chicago Haymarket Conspiracy, The Detection and Trial of the Conspirators.

Anarchy and Anarchists is embroidered with tales of creepy encounters with strangers, meetings with mysterious women veiled in black, heroic penetrations of clandestine meeting places, anonymous missives, and so on. At the outset, the author startles us with the assurance (p.74) that “Socialism in the United States may be regarded as synonymous with Anarchy.” Well-meaning, naive strikers were duped by the‘’Socialists-Anarchists” in 1886 ‘’to strike a blow which would terrorize the community and inaugurate the rule of the Commune.” Moreover, the bloody streetcar confrontations in the summer of 1885 had not been due to Inspector Bonfield’s detail [of police brutalizing innocent people] at all, but resulted from “prearranged plans” of “the Anarchists and Socialists of Chicago [who] did everything to create a bloody conflict between the police and the strikers.’

Dipping into Social Darwinist wisdom, Schaack treats his readers to an extended paean to the glories of free enterprise and the perils of a socialist, equalitarian society, which not only offers no incentive to great achievements in art, literature, or invention, but places everyone on an equal footing, “the profligate with the provident and the drunken wretch with the industrious’’ (p. 84).

Arrayed against kindly and generous employers are the ‘‘Huns and Vandals of modern civilization,” the socialists and anarchists who demand ten hours’ pay for eight hours’ work in the hope that employer resistance will lead workers who secretly profess socialism “to the point of violence” (p. 103). All of the conflicts preceding Haymarket were planned preliminary stages in a vast takeover conspiracy, culminating in what Schaack repeatedly refers to as the “Monday Night Conspiracy,’” to be ignited by the Haymarket demonstration on the following day. This plot, a product of Schaack’s febrile imagination, was assertedly proposed by Engel and endorsed by Fisher and contemplated that bombs be thrown into police stations; riflemen of the Lehr und Wehr would post themselves outside, and whoever came out of the station would be shot down. They then would come into the heart of the city, where the fight would commence in earnest. When all the conspirators finally reached the center of the city, they would set fire to the most prominent buildings, attack the jail, open the doors, and free the inmates to join them. And why did it not take place? The reason ‘‘is not explicable upon any other hypothesis than that the courage of the trusted leaders failed them at the critical moment.”’

...

Schaack’s prime post-Haymarket objective was to stoke the fires of fear and panic, which the trial and executions might quench. Vigilance cannot be relaxed; the danger is greater than ever. In addition to the 75,000 men, women, and children who are socialists, we must remember the 7,300 dangerous anarchists! (Wholly invented figures, as his book’s appendices show.) He cannot warn us often enough that we must be prepared for a fight to the death:

All over the world the apostles of disorder, rapine and Anarchy are today pressing forward their work of ruin, and preaching their gospel of disasters to all the nations with more fiery energy and a better organized propaganda than was ever known before. People who imagine that the energy of the revolutionists has slackened, or that the determination to wreck all the existing systems has grown less bitter, are deceiving themselves. The conspiracy against society is as determined as it ever was, and among every nation the spirit of revolt is being galvanized into a newer and more dangerous life. (p. 687)

Schaack comes through as the quintessential political sleuth, the forerunner of a long line of zealots who, with the support of the business community, used their counter-subversive specialty to achieve self-promotion, power, fame, and profit. Like the police red-hunters who walked in his tracks, he thirsted, in Shakespeare’s words, for ‘the big wars / That make ambition virtue” (Othello 3.3.349-50).

Schaack and his detail blazed a trail in another area—corruption and greed. While such failings were endemic in the nineteenth-century police world, they were particularly notable in areas where the urban elites of the Gilded Age felt threatened by the unrest of the lower classes and were hence ready to pay whatever was needed—tolerating graft or direct payoffs—to ensure police aggression in restraining troublemakers."

- Frank L. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America. Berkley: University of California Press, 1990. p. 14-16, 18-19.

#chicago#haymarket affair#haymarket massacre#red squad#police spy#detective fiction#anti-communism#fear of a red planet#anarchism#anarchists#academic quote#reading 2024#protectors of privilege#united states history#history of crime and punishment#police corruption#class war

0 notes

Text

From the Seattle IWW, written by FW Noah in 2022: "The True History of May Day."

In the United States and many other countries, there are labor days that celebrate the working class contributions to the economy, the infrastructure, and the nation as a whole. While many of these holidays give great praise and pomp towards working class people, they often overlook the history that led up to the foundation of such celebrations, and what the foundations were really laid upon. Much of the early labor history is filled with great strife, conflict, death and destruction often directed towards working class individuals, who attempted to organize their lives in a way to break off the shackles of exploitation and capitalism as a whole.

May Day began as a remembrance of the Haymarket Affair of 1886, when several anarchists who were supporting a protest for the 8 hour day in the city of Chicago were falsely accused by the police of detonating a bomb, and were executed as a result despite nationwide demands for their clemency. Since that day, every May the 1st became a day of celebrating the toil and contributions of workers in society and the struggle for better working class conditions, and uplifted the voices of those who were often marginalized or ignored by the upper classes. However, the United States of America has a different official Labor Day, established by the federal government in 1894. The change in date was intended to distract workers from the more radical origins of the holiday. This began a trend in the larger labor movement away from uniting the working class as one body with common interests and towards formalizing relations between a disadvantaged class and those with the power and wealth to decide the course of negotiations.

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conclusion: May Day today

The Haymarket Tragedy remains a symbol of countless struggles against capitalism, the State and oppression. Freedoms won in recent times rest on the sacrifices of martyrs like the IWPA anarchists, and the Malawian workers of 1959, 1992 and 1993.

May Day is a symbol of the unshakeable power of working class solidarity, and of remembrance for martyrs. It can serve as a rallying point for new anti-capitalist, participatory-democratic left resistance.

We need to defend and extend the legacy of the Haymarket affair, and to build the working class as a power-from-below for social change.

#history#Malawi#May Day#labor#malawian politics#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

We here at amtrak are not only celebrating our birthday but also the anniversary of the Haymarket affair this year because the only thing I love more than trains is a strong union.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Labor Day

Summer’s final fling has arrived in the form of Labor Day. Yes, most of us get the day off, but this holiday triggers mixed emotions. While summer still has 21 calendar days left, it’s time to get serious. School’s starting and there’s a sense that summer vacation is over. So what’s behind Labor Day — and how did it earn a place as a federal holiday?

Let’s take a look.

When is Labor Day 2024?

Labor Day always falls on the first Monday in September, which means anywhere from September 1 through September 7. This year it's September 2 in the U.S. and Canada. However, this is not the case for most countries — the majority of which celebrate on May 1.

History of Labor Day

Do you get weekends off work? Lunch breaks? Paid vacation? An eight-hour workday? Social security? If you said “yes” to any of these questions, you can thank labor unions and the U.S. labor movement for it. Years of hard-fought battles (and the ensuing legislation they inspired) resulted in many of the most basic benefits we enjoy at our jobs today. On the first Monday in September, we take the day off to celebrate Labor Day and reflect on the American worker’s contributions to our country.

Labor Day History

There’s disagreement over how the holiday began. One version is set in September 1882 with the Knights of Labor, the largest and one of the most important American labor organizations at the time. The Knights in New York City held a public parade featuring various labor organizations on September 5 — with the aid of the fledgling Central Labor Union (CLU) of New York. Subsequently, CLU Secretary Matthew Maguire proposed that a national Labor Day holiday be held on the first Monday of each September to mark this successful public demonstration.

In another version, Labor Day in September was proposed by Peter J. McGuire, a vice president of the American Federation of Labor. In spring 1882, McGuire reportedly proposed a “general holiday for the laboring classes” to the CLU, which would begin with a street parade of organized labor solidarity and end with a picnic fundraiser for local unions. McGuire suggested the first Monday in September as an ideal date for Labor Day because the weather is great at that time of year, and it falls between July 4th and Thanksgiving. Oregon became the first U.S. state to make it an official public holiday. 29 other states had joined by the time the federal government declared it a federal holiday in 1894.

Maguire or McGuire? Read more on this unusual coincidence in our FAQs below.

What is the Haymarket affair?

On May 4, 1886 — at a time when most American laborers worked 18 or even 20 hours a day — tens of thousands of workers protested in cities all across the U.S. to demand an eight-hour workday. Police in Chicago attacked both those peaceful protests and a workers planning meeting two days later, randomly beating and shooting at the planning group and killing six. When outraged Chicagoans attended an initially peaceful protest the next evening in Haymarket Square, police advanced on the crowd again. Someone who was never identified detonated a bomb that killed a police officer, leading cops to open fire on protesters and provoke violence that led to the deaths of about a dozen workers and police.

The Pullman strike

Ironically, Chicago was also the setting for the bloody Pullman strike of 1894, which catalyzed the establishment of an official Labor Day holiday in the U.S. on the first Monday of September.

The strike happened in May in the company town of Pullman, Chicago, a factory location established by luxury railroad car manufacturer the Pullman Company. The inequality of the town was more than apparent. Company owner George Pullman lived in a mansion while most laborers stayed in barracks-style dormitories. When a nationwide depression struck in 1893, Pullman decided to cut costs the way a lot of executives at the time did — by lowering wages by almost 30% while he kept the rent on the dormitories he leased to his workers at pre-depression levels.

Railroad boycott

These conditions ultimately led workers to strike on May 11, 1894. The walkout gained the support of the nationwide American Railroad Union (ARU), which declared that ARU members would no longer work on trains that included Pullman cars. That national boycott would end up bringing the railroads west of Chicago to a standstill and led to 125,000 workers across 29 railroad companies quitting their jobs rather than breaking the boycott.

When the Chicago railroad companies hired strikebreakers as replacements, strikers also took various actions to stop the trains. The General Managers Association, which represented local railroad companies, countered by inducing U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney, a former railroad attorney, to intervene. Indianapolis federal courts granted Olney an injunction against the strike, a move that allowed President Grover Cleveland to send in federal troops to break it up.

A few days later, Cleveland realized that he had to act quickly to appease the country’s increasingly agitated labor movement. But he didn’t want to commemorate the Haymarket incident with a May holiday that would invoke radical worker sentiment. So Cleveland harkened back to the first established September 1882 holiday and signed into law that Labor Day in the U.S. would be celebrated on the first Monday in September.

Labor Day vs. May Day

Communist and socialist factions worldwide eventually chose May 1 as the date to mark the Haymarket affair. A 1904 conference issued a plea that trade unions stage rallies on the first day of May — demanding to make the eight-hour workday standard. They organized the action in the name of “universal peace.” The 1st of May is a national, public holiday in many countries across the world, generally known as “Labour Day,” “International Workers’ Day,” or a similar name – although some countries celebrate a Labor Day on other dates significant to them, such as Canada, which celebrates Labor Day, like the U.S., on the first Monday of September.

Here’s the U.S. Department of Labor’s official tribute to U.S. workers on Labor Day:

“The vital force of labor added materially to the highest standard of living and the greatest production the world has ever known, and has brought us closer to the realization of our traditional ideals of economic and political democracy. It is appropriate, therefore, that the nation pays tribute on Labor Day to the creator of so much of the nation’s strength, freedom, and leadership — the American worker.”

Related Labor Day Content

1) Top Labor Day quotes for your social feeds

Can you guess which president said, “My father taught me to work; he did not teach me to love it”? How about the famous American who uttered “All labor that uplifts humanity has dignity”? We have a list of Labor Day quotes to not only learn about the holiday but to also impress your friends at the barbecue.

2) Fire yourself from your own job

That’s correct. The makers of STōK cold-brew coffees have designed a contest — running through Labor Day — which will give three people $30,000 each in order to take a four-week “STōKbbattical” (from their dreary day jobs) and “make their dreams happen.” It can be anything from rock climbing in Patagonia to setting records for the number of tapas eaten in Spain. No matter what, STōK will help fund it. Unless of course, you’d prefer to spend the next four weeks filling out TPS reports.

3) 8 Labor Day Activities To Enjoy

Whether in the form of a leisurely barbeque, a relaxing swim in the pool, watching a film at a drive-in cinema, or even just relaxing at home with family, there are so many different ways to mark the occasion. We list some activities to try on Labor Day.

Labor Day timeline

1882 It’s Unofficial

10,000 labor workers march through Union Square in New York to protest poor working conditions and low wages.

1884 A Date is Set

The first Monday of September officially becomes Labor Day, with the Central Labor Union pushing other organizations to follow suit and celebrate.

1894 Congress Approves

Labor Day is approved as a national holiday by Congress, and President Grover Cleveland signs it into law.

2009 Let’s Not Forget Women in Labor

President Obama restores the rights of women to sue over pay discrimination with the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

Labor Day Traditions

Much like Memorial Day, which marks the traditional beginning of summer, Labor Day generally signifies that the season has ended — even though the calendar says otherwise. Holiday sales, barbecues, and travel tend to rule the day, while children finally adjust to the harsh reality of the “back-to-school” season. As far as U.S. sports are concerned, Labor Day weekend signals that baseball’s pennant races have entered their final stretch, and tennis fans get an extra day to watch the season’s last Grand Slam event — the U.S. Open in New York City. NFL regular-season games typically begin following Labor Day.

Labor Day by the numbers

162 million – the number of Americans (over 16) in the labor force.

40% – the percentage of U.S. workers who belonged to labor unions in the 1950s (that dropped to 11% by 2018).

1894 – the year Congress officially made Labor Day a federal holiday.

86% – the percentage of Americans planning Labor Day weekend travel who will do so by car.

41% – the percentage of Americans who plan to barbecue over Labor Day Weekend.

818 – the number of U.S. hot dogs eaten every second from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

$685 – the average kid’s back-to-school expenses.

$55,000 – the median U.S. household income.

705 million – the total number of U.S. unused vacation days (2017).

80% – the percentage of Americans who would take time off if their boss were more supportive.

— courtesy WalletHub ©2018

Labor Day FAQs

What does Labor Day really mean?

Americans, as well as workers around the world, celebrate Labor Day by reflecting on all the contributions everyday workers have made to society. Not all countries observe Labor Day on the same date though.

When is Labor Day 2020?

The U.S. observed Labor Day 2020 on Monday, September 2. It’s a federal holiday. Financial markets are closed. There is no mail delivery. Post offices and libraries are closed. Most retail businesses will remain open.

Who invented Labor Day?

It’s more confusing than you might think. The Labor Department explains it this way:

While most sources, including the U.S. Department of Labor, credit Peter McGuire with the origination of Labor Day, recent evidence suggests that the true father of Labor Day may, in fact, be another famous union leader of the 19th century, Matthew Maguire.

Maguire held some political beliefs that were considered fairly radical for the day and also for Samuel Gompers and his American Federation of Labor. Allegedly, Gompers, who co-founded the AFL along with his friend McGuire, did not want Labor Day to become associated with the sort of “radical” politics of Matthew Maguire. So in an 1897 interview, Gompers’ close friend Peter J. McGuire was assigned the credit for the origination of Labor Day.

What's the difference between Labor Day and May Day (May 1)

May 1 (or May Day) is a more radicalized version of Labor Day in many countries. The date recalls Chicago’s Haymarket affair in 1886. American workers, tired of 18-hour days, staged a protest. Police eventually fired on the workers — killing eight. The following night, May 4, another rally turned violent when someone threw a bomb at police officers. An estimated 11 people died and scores more were injured. Communist and socialist political parties eventually chose May 1 as the date to honor the dead and injured workers.

Labor Day Activities

Read up on the history of Labor Day

Buy an American-made product

Watch a movie about labor unions

Labor Day has a rich history that directly impacts the working conditions we experience today. So in between rounds of BBQ at your Labor Day celebration, take the time to discuss the U.S. labor movement and its contribution to our country's current work culture.

When you're doing your Labor Day shopping, take the time to read the labels. Consider buying products that say "Made in the USA" to show your support for American workers.

Many of us get Labor Day off. What better way to relax than to stretch out on the couch and watch a movie about the American labor movement? There are tons of union-themed movies to choose from. "Norma Rae" ring a bell? Side note: Unions play a major role in the entertainment industry.

5 Labor Day Facts Everyone Should Know!

It’s on May 1 in other countries

Stores remain open

Third most popular holiday for outdoor cookouts

Labor Day marks the unofficial NFL kickoff

Union members today

Most countries around the world celebrate Labor Day on May 1, and it is called International Workers’ Day.

While most schools and offices are closed on Labor Day, retail workers and shopkeepers don’t get the same break, as the holiday is huge for sales and shopping.

Labor Day is right behind the Fourth of July and Memorial Day in being the most popular holiday for barbecues and cookouts.

99.4% of the time, the NFL’s first official game of the season is on the Thursday following Labor Day.

In 2017, there were 14.8 million union members, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while in 1983, there were 17.7 million.

Why We Love Labor Day

We're hard workers — we deserve the day off

It's one last chance to grill

It's the reason we can say TGIF

Statistics show that Americans work longer hours than citizens of most other countries — 137 more hours per year than Japan, 260 more per year than the U.K., and 499 more than France. And our productivity is high — 400% higher than it was in 1950, to be exact. So we totally deserve that day off.

Labor Day is widely considered to be the unofficial last day of summer. Before the air turns cold and the leaves start to fall, it's our last chance to grill some steaks and wear shorts.

Labor Day is a time to celebrate the benefits we enjoy at our jobs — including weekends off. The concept of American workers taking days off dates back to 1791, when a group of carpenters in Philadelphia went on strike to demand a shorter workweek (10-hour days, to be exact). It wasn't until 1836 that workers started demanding eight-hour workdays. So nine to five doesn't sound so bad after all.

Source

#Edmonton#Sparwood#Coal Miner#British Columbia#Terex 33-19 Titan#USA#Canada#Labor Day#First Monday in September#2 September 2024#LaborDay#Logger by Joerg Jung#Prospector and his dog by Chuck Buchanan#Stampeder Statue by Peter Lucchetti#Skagway Centennial Statue by Chuck Buchanan#Standing Together by John Greer#Anonymity of Prevention by Derek Lo and Lana Winkler#Whitehorse#travel#original photography#tourist attraction#landmark#vacation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

before it gets to be too late!

i hope you've all had a happy:

International Worker's Day (began in 1886 after the Haymarket affair)

May Day

Pluto's birthday (well, kind of. the name "Pluto" was officially proposed in 1930)

Anniversary of the recognition of Scotland as an independent state (1328)

Anniversary of England and Scotland becoming Great Britain, ironically (1707)

Abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire (1807)

Anniversary of adhesive postage stamps (1840)

Anniversary of the dedication of the Empire State Building (1931)

Anniversary of the development of the polio vaccine (1956)

Anniversary of the first man to reach the North Pole solo (1978)

Swedish legalization of same-sex marriage (2009)

#may 1st#wild fuckin day in history#the irony of Britain recognizing and retconning Scotland the same day 379 years later#happy birthday to convenient postage stamps

5 notes

·

View notes