Text

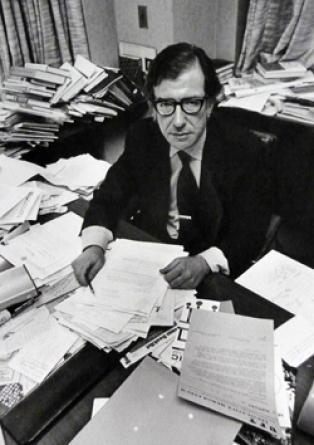

JERALD PODAIR

The UFT Has Made Sausages: an interview with Jerald Podair

In November 2020, the NYC United Federation of Teachers endorsed the Black Lives Matter in Schools campaign. About 90% of the union delegates voted for this. This was a stark contrast to previous years, when the UFT hierarchy plotted to filibuster or derail attempts to have the Delegate Assembly endorse this national campaign for liberation. And this is, unfortunately, a deeply rooted part of the UFT history, from its recent collaboration in ballooning school segregation, back to its battles in Ocean Hill-Brownsville strikes in 1968 and its cold shoulder to the largest student boycott in 1964.

In the following interview, I discuss the UFT’s history with Jerald Podair, the author of the book THE STRIKE THAT CHANGED NEW YORK, we cover topics from the 1968 UFT strike through present-day conflicts over NYC’s unequal schools, considered the most segregated in the country. The 1968 strike pitted Superintendent Rhody McCoy, the black superintendent of the local Brooklyn school board, against Al Shanker, the powerful president of the UFT (and later the American Federation of Teachers). McCoy insisted on his right to fire or at least reassign teachers who openly resisted his afrocentric, liberatory, and postcolonial pedagogical vision. Shanker refused with great zeal, sending the teachers union into a confrontation with the city lasting several months. The media tried to frame the event as a conflict between blacks (the community) and Jews (the teachers). The UFT ultimately was successful and became a stronger force in its role as co-manager of the NYC schools, but the reaction to the UFT’s principles and tactics during the strike has ranged from glowing adoration to harsh critique.

While Podair is ultimately pessimistic about the UFT’s capacity for embracing radical action for social change as a primary priority – and one can’t say he doesn’t have 60-plus years of history to back him up – the recent Delegate Assembly vote on BLM in Schools suggests the UFT may be ripe for a change in attitude and direction. Can the UFT break its 60+ years of following the business unionism model of Samuel Gompers? Can it put educator union power to work in a fight that many NYC communities are ready to join against material and racial inequality? These questions and more are discussed below.

Jerald Podair, professor, historian, and author of numerous books, including THE STRIKE THAT CHANGED NEW YORK. http://jeraldpodair.com/

How did you become interested in and research the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike?

JP: The Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike was almost a part of my DNA because I lived through it as a high school student in the fall of 1968. I was in the New York public school system when the strike occurred, and at the time I didn’t pay all that much attention to it. My main concern was getting out of school, not having to go to school. Ocean Hill-Brownsville basically kept New York City public school students out for about 3 months. I wasn't very political then. It struck me maybe 20-25 years later, when I was thinking of a dissertation topic, that it was really not only an important event in New York City education history, it was really an important event in New York history, general New York City history, and especially racial history. So I guess what I felt and heard and read and listened to during the strike sort of stuck in my DNA. or somehow got hardwired into me, because when I started thinking about a dissertation topic, I was a graduate student in history at Princeton, it's really the first thing I thought up, and so I began researching it.

This was in the 1990s. It was not an easy topic to research, as you might imagine, because emotions were still so raw on each side, and not everybody I wanted to talk to was willing to talk to me. Albert Shanker never talked to me. As I understand it, I gave a presentation at the American historical association convention in the early nineties on Ocean Hill-Brownsville and he went to it. He was the president of the UFT and president of the AFT, at the time. He was in Washington, so he came and apparently he didn't like what I had to say because he had promised to give me an interview. After he heard what I had to say, he didn't want to talk to me. And that’s not the fault of Albert Shanker. He had his position.

It wasn't the easiest topic to research and I found it much easier to just go through a newspaper run and I had to pretty much read every word of the New York Times, the New York Post and The New York Daily News for about a year to get quotes, to get reactions, to get information. Now newspapers are not always the easiest and most reliable sources, as you know. They are known as the first draft of history for a reason. But what I found is that they were more reliable than some of the people who would talk to me because I felt in many ways I was being spinned, again, by both sides, and I was always reminded as I did research of this of the great Japanese film Rashomon; basically people on both sides of the conflict were telling me things that were not necessarily true but we're basically filtered through their own self-interest so just like a little Rashomon the characters were not necessarily lying out right but they were just shaping the truth to fit their own sensibilities and their own agendas and that's what I found when I interviewed both, so for this dissertation I found relying on newspapers and at least what people were quoted as saying was my most reliable source. I went through the papers of the UFT at NYU and also the city board of education at Columbia.

So to make a long story, the PhD dissertation writing took me about 4 years but I had some road blocks along the way I got my notes stolen then it cost me about a year so I would say it took me 6 years to research and write it.

How did the notes get stolen?

JP: It's become a family legend and a legend among my colleagues. We were living in Princeton at the time my wife and I and our daughter and we drove up to the Bronx to visit my parents who still live in the Bronx. I don't know if you've ever been a graduate student or know graduate students but they get very obsessive about things. I took all my notes and I piled in the back of the trunk of the car because I thought I was going to look at them over the weekend, which was unrealistic, and I took basically everything, and the car got stolen and it was pretty horrific to go back to that parking space and not see it there. They found it in the South Bronx completely stripped and everything was gone and the notes were gone as well, so I basically had to start all over. I had to go back to Columbia. I mean it was easier the second time around because I knew where to look but it basically cost me a year and a half, maybe 2 years, of my life. I always heard it said you have to be a little crazy to be a graduate student and write a dissertation and that helped because the same person who would say that would have viewed that lost a dissertation notes as a sign from god and just quit. I didn't.

Otherwise, why was the book hard to write? Basically just because it was hard to get access to people? Was Shanker the only one that didn't give you access?

JP: There were plenty of people who didn't give me access, or gave me only partial access, or they gave me access and didn't really give me what I needed. So the second time, after all my notes were stolen I decided to sit down and go through the Daily News and all the New York City dailies for every day for 1968 and the beginning of 1969, as well as the Times, who's the most accessible, to see what they said. I also feel that my own knowledge of Ocean Hill-Brownsville was so deep, right down to the ground level, and I certainly could tell whether somebody was stating the truth, so access was also complicated by the nature of the dispute. Usually there are heroes and villains in most historical stories – not in this one, because they were you know it was almost like everyone was right and everyone was wrong and I think it's very difficult for historians even today to approach Ocean Hill-Brownsville because it's so paradoxical and doesn't really fit into any sort of a coherent narrative like that all whites are racist or these teachers were racist; it doesn't fit into the narrative that they you know that all blacks were were unrealistic and anarchistic and violent. It fits into some of those categories but it doesn't fit into all of them and so it's not the easiest story to tell and I think what I had to do is sort of leave my own baggage at the door. We are all people, we have backgrounds: we have ethnic backgrounds, religious backgrounds, racial backgrounds. So I tried to leave all of that at the door and try to get into the heads of all of the participants in this, to get into Al Shanker’s, Superintendent McCoy’s, Mayor John Lindsay's heads, and try to do that in a reasonably just passionate way. Hopefully I did a fair job. I think that's a good thing because I think if I surprised and maybe even just made both blacks and whites can I get that meant I was doing a good job and trying at least to be if you want to do a fair job.

Can you explain just a little more why Shanker didn’t want to talk to you? Talk a little bit about why people thought you were black besides just the cover?

JP: Shanker was looking for an exoneration basically and endorsements of pretty much everything he and the union had done during the strike; in other words, journalists who would say this is not about race or the strike is not about race, it is only about due process for teachers who are unfairly fired. To deny that they were racial issues is completely unrealistic. You have to confront those issues in order to do a good job with it historically, so I think what Shanker was looking for and of course he's not an academic historian. I know that many of my fellow historians would agree to disagree with me on that but I think you have to try to hold yourself outside of it, leave your baggage at the door, and try to be fair to both; historians have to criticize, I mean that's our job, but you also have to have some sense of sympathy for a person who is in a position that you are not, in knowing much less than you know 20 or 30 or even 100 years down the line, so you have to both be critical but sympathetic. I understand he would want me to completely exonerate the UFT, but I couldn't do that and I think that's sort of what bothered him. He was emotionally invested in ocean hill Brownsville as much as anything in his entire career. That probably was the most emotionally draining situation that he had been in as the union leader. I can't think of anything else that came close and he was so emotionally invested in it even 25 years later that wounds were still raw. To a lesser extent I got that from a lot of people that I tried to talk to about it: just too emotionally involved.

How do you see the UFT development since then?

JP: The UFT established itself as co-manager of the New York City public school system through the strike. Most of the strikes right now are about money but Ocean Hill Brownsville though was not about money it was about control. It was in 1968 that this strike established the UFT as a co-manager of the public school system which it was not before 1968. Before Shanker and the union leaders’ goal was to get money, but control in many ways was was more important than money; in other words, if Shanker had allowed Lindsay to buy him with money during this trial, if he allowed for everyone in the system to get a check but go back to work, Shanker would have turned that down, because he understood that that would have been a short term victory but the long term goal would have been lost: control.

The same caucus controls the union, the UNITY Caucus, since Shanker was in power.

JP: Really, wow. Didn’t realize that. So they’ve been around over 50 years?

Basically. And they filled a power vacuum left by government purges of “reds” and other socialist-leaning unionists. UNITY Caucus themselves were staunchly anti-communist when they were founded. The previous union, the Teacher’s Union (TU), was actually filled with many socialists and communists and the UFT, led by the UNITY Caucus, filled that void.

JP: You're absolutely right. It’s really crucial to understanding the history of the UFT. They're really tough anti-communists and they were one of several competing associations trying to get collective bargaining power for teachers.

What would it be like if the union had been less opposed to social justice and done less damage to community ties in the 60s in some of those neighborhoods? Is it possible for them to both win protections for the workers and also further social justice in terms of integrating schools and that type of thing and promoting black empowerment.

JP: My book shows how complicated that was for the UFT. First, Shanker and most of the UFT higher ups would say “we are for social justice” and what they would say is “you know we supported Martin Luther King and all of his campaigns. Martin Luther king is a personal friend.” He did address the U.F.T. On many occasions, he supported them when they were establishing their own union, and they supported him at the March on Washington and at Freedom Summer, so they thought they had the social justice bona fide. What what Shanker and other union higher ups would probably say in 1968 is “you don't know what it was like to be a teacher in the New York City public schools in the forties and fifties, but we do and what we know is that teachers had no control, no power, no dignity.” So the UFT was founded to change that – did change that. As for social justice, at Ocean Hill-Brownsville they were asked to make a choice between the 2 and the UFT leaders ended up choosing the power of the union and the power of the teacher over ideals of more radical militants interested in social justice. In other words, they were for social justice but not at their own expense.

Albert Shanker, founder and president of the United Federation of Teachers 1964 to 1985 and president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) from 1974 to 1997.

Wildcat teacher strikes in recent years in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Oakland were fighting for higher wages, benefits, protections, and other working conditions. The LA strike and then the Chicago one in 2019 they were more fighting for expanding funding for the schools and increasing counselors and that type of stuff. Do you think that had Shanker had the union mobilized at that time that they would have fought for those issues? Because public schools in NYC were basically gutted in the 70s and 80s.

JP: Back when Samuel Gompers was the president of the AFL testifying before a congressional committee in the early 1900s and somebody said, “You know Mister Gompers, what does labor want?” and he just says, “More.” That's it. “More.” And that's what Shanker wanted. He wanted more. He wanted more counselors, he wanted more money to be spent on schools. He wanted it for two reasons: he wanted it because I think he was honestly committed to some form of social justice but also he wanted more jobs for his teachers and more power for the union. He did want all those things but what he didn't want to do was cede control over education to a community group or community groups that he felt threatened his teachers and threatened their jobs. All the money in the world, he was very happy to have. The New York City government spent lots of money on teachers, or social justice, to fund counselors, special ed, everything. He wasn't into allowing the community school board to fire one of his teachers. That he would not do, and that's what caused the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike. So you know in many ways as we look at it retrospectively: it didn't have to happen, and that means that if both sides had compromised, it probably would not have happened. But we can't go back. From the standpoint of community people and parents in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community, they see that their children are not getting good education and even more specifically not getting the kind of education the kids in the white middle class areas of New York City are getting, who are getting the better teachers, better facilities. There’s something colloquially called combat pay in the 1960s, where teachers in poor neighborhoods get paid more money and also get a chance to transfer out after like a certain number of years.

There’s something in the most recent UFT contract where if you go to teach at struggling schools in the Bronx or Brooklyn you get higher pay.

JP: In the 1960s there was some sort of a provision where if you put a certain number of years and in those schools then you could leave and what happened in the sixties is that they were trying younger teachers, the beginning teachers (not veteran teachers) to the schools in communities like Ocean Hill-Brownsville, who could see that the education their kids were getting was not the same kind of education that that white middle class kids were getting and they were angry about that and I think justifiably angry about that, and of course Al Shanker would say, “I'm angry about that too and I want to do something about that and the way I want to do something because it is I want the school board to hire more teachers, more counselors, more administrators” and the community said, “well that's that's not really what we had in mind. We want control.” And that’s not what Shanker had in mind and he wouldn’t stand for that.

Now a big fight in New York City schools is over the screening process. Are you aware of this?

JP: I'm actually not really.

So kids take screening tests. The original schools like Bronx Science and Stuyvesant had to take tests to get in, but starting with Guiliani, then it was expanded during Bloomberg. Students take these tests at the end of middle school and there's some schools – like the school where I teach – that are unscreened but there's some schools that are screened, where you have to have a certain test score to get in and those schools are predominantly white and Asian and then you have schools that are unscreened that are predominantly black and brown students, so you really have a segregated school system, arguably the most segregated in the country.

JP: Well I was going to say that at least in the sixties you had the zoned school and Bronx Science, Stuyvesant, only a certain number of students.

So I guess my question, returning to social justice, but through the lens of focusing on teachers' working conditions, and Weingarten and Mulgrew were Shanker’s successors, so I'm just kind of wondering how that fits into this?

JP: They really had the same agenda as Shanker. In other words, they're all tough union bosses who put the interests of their membership above all. The conceit for the UFT all through the years is that the interests of their members coincide with the interests of social justice and you don't have to make the choice between one or the other, but of course that's not always the case as we saw in Ocean Hill-Brownsville. When push comes to shove they're going to protect members; if they have a chance to get more money and more hiring but taxes go up and taxes go up for everybody including poor people they're going to do it because that's what comes first. The social justice component is important but when it collides with the interests of the union members, they come first and. I think most union leaders, even the public sector union leaders who say they're for social justice, they're going to make that calculation.

Do you think we still see some of the same forces at work in the contemporary struggles over education?

JP: From what you've just told me, in New York you have a school system that is more segregated than it may have been even in the 1960s and it's pretty segregated in the 1960s and that was the basis of community control, the philosophical basis of it. African American parents in the mid 1960s basically gave up on the integration struggle because white parents had certainly given up on the integration struggle, and what black parents said is, “Well it looks like our schools are going to be segregated almost permanently and if that's the case, we might as well control it.” They're really being segregated by class, it seems to me, so that is that is going to be the issue going forward now. What is the UFT going to do with that? Well they may want to do something about it but I think again they are beholden to their members and their members may not have that will. Everyone in America says we want to be equal. But when you get into real life situations you sometimes wonder how many Americans really want to be equal, and take it to the UFT I would imagine that the majority of members view themselves as liberals or even on the left, and they vote for Democratic candidates, but when push comes to shove do they want to teach in an unscreened school or a screened school? Well a lot of them are going to make the choice to go to the screened school and they may give you all sorts of justifications that nothing to do with race, but it does come down at least to some extent to race and it also comes down to maybe something inside of them that does not want to be equal, that's wants to be elite or special, and maybe that's part of human nature but I don’t think the UFT itself is going to contribute to breaking down the system because I think in many ways the membership has an interest in perpetuating the system as it is.

You're a labor historian. Can you think of an example of a union or labor movement that was both focused on working conditions for the workers in the union but then also focused as a primary concern on the community or in the society?

JP: The Wobblies was a union that focused not only on working conditions for their members but also wanted to change the entire economic and social structure of the United States.

Poster for the Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies, a trade union across industries that has fought for work protections and power as part of a larger campaign for social revolution. https://iww.org/assets/One-Big-Union.pdf

Similar to the Teachers Union (TU), the socialist and communist -oriented union that came before the UFT and was destroyed by the red scares in the 1940s and 50s.

JP: Yes, and former members of that formed a caucus that was against Shanker’s UNITY caucus in the UFT. They are trying to do that massive social change and that caucus within the UFT opposes the strike from the very beginning and they're saying we have to align ourselves with the communities in which we teach so that we can change them for the better but in a sense they are making choices too. They’re unselfish in the sense that they would say well we're willing to forgo raises to help the community, we're willing to give the community control, in order to get equity and social justice in these neighborhoods. But I would argue that most teachers were not like that; they're much more self interested, much less willing to sacrifice themselves. I think what distinguishes these teachers is they were truly selfless. Because the right has many problems of its own, which we know, but one of the major problems on the left is hypocrisy and the idea that they want other people to do what they themselves will not. You talk the talk, but you don't walk the walk. Well these anti-strike teachers in 1968 in the UFT, they walked the walk. They were willing to make personal sacrifices, not have somebody else do it. Shanker opposed them and tried to destroy the caucus, but I think on some level he had to respect them.

Yeah the caucus I am in, the Movement of Rank and File Educators, is sort of the descendent of that caucus.

JP: The only UFT leader who spoke out at the time was John O’Neil. Also, George Altomare, one of the only living and remaining members of the UFT hierarchy, and I talked to him a couple of years ago and he's the only really high ranking UFT who really tries to settle this and make a compromise and he got estranged from Shanker and the leadership over that. And Shanker basically just kept saying, “Fuck you, we want these teachers back in the classroom now” to the city and the media. And possibly the person who was floating a compromise of reassigning the teachers to other duties was George Altomare. He's the last one left from Ocean Hill-Brownsville who's actually alive as far as I know. He was sort of half in and half out and I think he was trying to be sort of a go between the community and the union hierarchy. Shanker was very absolutist over this and I think they had a falling out over that.

I also found it interesting that you said that your book doesn't really fit comfortably in like a right wing or left wing historical narrative. I took it to show that the UFT failed to work with communities for funding and equality and instead had been focused on working conditions only. What would have happened if the UFT had worked more with communities on more systemic changes that could have been more mutually beneficial?

JP: You could make that argument. But based on my research, I think most city school teachers were and maybe are politically with the cops, the firemen, the sanitation workers. They're just interested in “more”. They're not politically active and what they're worried about are their salaries and their jobs. So when you have a union that is mostly composed of people like that, there's a limit to how far you're going to be able to go in terms of social justice. Again the UFT always said, “We're for integration.” Shanker said all the way through: “We are pro-integration”, but when Bayard Rustin (who I actually wrote a biography of) organized a student boycott and the UFT at least nominally supported that but they were not willing to go to bat for their members who boycotted that day. They said, “Take a sick day” or something like that, and didn't necessarily confront the board of education directly over this. The organizers of the boycott were disappointed in the UFT hierarchy's reaction to it. They didn’t oppose it but they didn’t use work stoppage. The UFT at that time was in favor of school integration. It's not like they were ever, you know, against it. But again, there's you know then idea skin in the game. And resources. I think the UFT was worried about that and the reason they're worried is - it's related to this idea of social justice clashing with the goals of union power -- this is 1964: they're not that powerful a union and they may not want to piss off the board of education with whom they're trying to share power. They're not necessarily a struggling union but they’re young, only like 4 years old, and they may not have wanted to throw in fully. Sometimes you have to to do what you have to do. When I wrote my biography of Rustin, I was struck by an incident in the late 1950s, where Rustin is a close adviser to Martin Luther King, and Rustin helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and probably was going to be the managing director of the SCLC. What happens is Rustin, who is gay, gets caught in rumors of this and they reach Martin Luther King, who cut off Rustin and they reunited for the March on Washington in about 3 years. He basically cut Rustin off, and they don't have all that much contact. I think that King's thinking here is, “I have enough problems with what I'm doing without also having a gay man as the director of the SCLC I'm already being called a communist. I'm already being called an anarchist, a revolutionary. King made a strategic decision and cut this guy off, and that's how it works sometimes. In many ways, the UFT was generally thinking in 1964: “We've got enough problems with the Board of Education, establishing ourselves with the union, do we really, really want to go all in on this boycott and support every teacher? That's probably going to hurt us down the road when it comes to bargaining with them.” There’s that saying that watching legislation get passed is like watching sausages get made. Well, King was making sausages, and so was the UFT.

1 note

·

View note

Text

RICHARD CHIEM

BIO: Richard Chiem is the author of You Private Person (Sorry House Classics, 2017), and the novel, King of Joy (Soft Skull, 2019). His book, You Private Person, was named one of Publishers Weekly’s 10 Essential Books of the American West. His work has been published by NY Tyrant, Fanzine, and The Nervous Breakdown, among many other places. He was named a 2019 Writer to Watch by the Los Angeles Times. He has taught at Hugo House, Catapult, and at the University of Washington Bothell. He lives in Seattle.

>>

1. You have Corvus, the protagonist. You have Tim, a pornographic film director who somewhat takes advantage of her. You have her tragic boyfriend, Perry. You have her close friend Amber. Each of these characters is very fully developed. How did you originally conceive of each of these characters? How did they develop through your drafting of this book? I know in some of your early writing you took inspiration from pop cultural media like television and movies, was there similar inspiration here?

I started writing the novel after watching Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers (2012) and I felt possessed to write one of the first scenes in the book, where Corvus is watching Amber burn down a tree. I am very much a sentence by sentence, sentence level writer, and the film showed me something new about style and plot. In watching the film, I learned that style in a way can transcend form to become story or narrative almost on its own. If something could make emotional sense, it could resonate with the reader. This thinking liberated me and gave me permission to write my weird book. Once I knew who Corvus was, I knew I had a novel project. All the characters are me, or some weird version of me, with inspiration from what I’ve seen in the world. I worked through and processed a lot of grief in writing the novel. I would say I was also very motivated by pop music writing this book, such as listening to a lot of Robyn, Elliott Smith, and Frank Ocean. Movies are also big for me as a model for writing. Films by Robert Bresson, David Cronenberg, Hayao Miyazaki, Wong Kar-Wai, among others. The film Blue Valentine. The novel Breaking & Entering by Joy Williams.

2. Was it weird for you as a male writer to take on the task of exploring a female main character? Did you think about this as you wrote? It’s obviously been done before, and vice versa, and done well many times, but I’m just wondering how self-aware you were about this as you wrote.

I wanted to write a book I wanted to read. I wanted a book that would be hard for me to write with a character I loved with great emotional capacity. I knew I wanted a book about Corvus and her survival, and I knew I wanted the book to feel true to its characters and feel emotionally authentic on the page.

In finding truth in fiction and finding truth in her identity, because I am a cis male and not a woman like Corvus, I had to be accountable to her and her life on the page, so I was very self-aware of her as I was drafting the book. It allowed and motivated me to be constantly asking questions about what story would reveal this truth for her and about her. If I wasn’t doing that precious and crucial work of pushing outside myself, the novel would not have been worth the effort for any reader.

3. Your prose has a deft touch to it, where you pack power into terse but flowing sentences. What writers specifically influenced your stylistic approach to the mechanics of writing, on a sentence-by-sentence level? How do you think your prose has changed since your last book, the story collection YOU PRIVATE PEOPLE?

Thank you so much, Andrew. There are so many writers that have influenced me powerfully, especially on the sentence level, but to start:

Fanny Howe, Rebecca Brown, Dennis Cooper, Joy Williams, Gary Lutz, Renee Gladman, Jean Rhys, Jane Bowles, Agota Kristof, Alissa Nutting, Melissa Broder, Édouard Levé, Unica Zurn, and Blake Butler, to name a few.

I feel as though I am coming into what feels like the height of my powers with prose. Or, the prose feels really good right now. I think what has changed in my prose between the two books is that I have such a stronger sense of what I want to say. Although I am a shadow boxer, I am no longer swinging in the dark, and everything is landing. I am always ready to throw hands.

4. What is your daily life like? How do you organize your time and space around writing and related work?

I would say I try to center my whole life around writing and the writing life. I work an office job (9 to 5) at an accounting department at a book store to pay the rent. I treat my writing time like I treat my sleep: I will take what I can get. I am also an insomniac, so I often write when I can’t find sleep. Otherwise, I try to schedule and manage of an hour of writing or editing every day. But I also allow myself rest when life catches up to me and I just can’t put words to the page. I’ve realized this rest is also crucial to the process and the art of listening to yourself. I also make time to show up for other writers, and I try to attend as many readings as I can, as well as read my peers’ work. I believe this is also crucial to who I am as a writer, being a listener.

5. What kinds of projects are you working on or do you plan to work on now that this book has been published?

I am currently working on a novel, a book of short stories, and a book of poetry. They are tentatively called CAVE ME IN, MESS YOU UP, and NOTHING KILLS ME, respectively. Give me another year or so before one of them is real for the world.

#richard chiem#novel#short story#poetry#real world#office job#dennis cooper#jean rhys#melissa broder#writers#david cronenberg#alissa nutting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joselia Hughes

Joselia "Jo" Hughes is a Black 1.5-generation Cuban-Jamaican-Guyanese-American writer and artist from the Bronx. She lives with Sickle Cell Disease (HBSC) and ADHD.

Where did you find the 3rd grade poem? How did you decide to include it? What other collage or found art/poetry do you like?

The 3rd grade poem was from a collection of student works, Witch’s Brew, released by my grammar school, Horace Mann. I have two issues from 2nd and 3rd grades. Both of my works were quartered in the “Fantasy” section. There was another section called “Feelings” and, I think, The Sky more accurately suggests a feeling. Scratch that: it explicitly discusses a feeling. This misidentification by academic administration/curatorial staff (which doubles as a political demonstration) is telling. I think it explains a lot about the root confusion between what I have felt/feel to know as Experientially True versus what I’m told to know as The Truth. When considering the emotional and material lives of Black femmes, we must remember Black femmes have been historically disallowed, disavowed and dispossessed of creative virtuosity. Too often, we are strapped in the monolith of stereotyped caricature dictated by the manifested destiny written into commandments/constitution of misogynoir. Black femme virtuosity is reappropriated, regesticulated and worn like some earned bloody body wisdom by the Opps (Oppressive Forces). While I didn’t have those terms as a child, I experienced the consequences of misogynoir in conjunction with dis/ableism and classism, which aren’t separate entities but necessary vices that amplify asphyxiation. Is disabled Black femme loneliness only permissible when classified as fantasy? That shit don’t sit right in my spirit. I also used the poem because the title is Witch’s Brew and my zine, Heartbeats But No Air (HBNA), is a kind of exorcism. A few years ago, I pieced together that my maternal grandmother was a covertly practicing Bruja. With the widening reclamation of ancestral wisdom by BIPOC, in an effort to decolonize our existences, I was tapping into that tender tendon of wisdom.

Understanding my grandmother’s practice reminded me that she wanted to name me Darthula Verbena (daughter of God, enchanting and medicinal). I started referring to myself as DV, my pre-name, and inspected my childhood. That’s been a remarkable endeavor. I had to teach myself to play again. Through play, I learned how to feel. Learning feeling meant learning the qualitative and quantitative nature of the labyrinth of my thoughts. Once I learned some of the turns of the labyrinth, I could feel to know how to navigate the terrain without fear and engage in the rigorous study that’s always characterized my central self. Play is a code switch. I often think of code switching as a means to subvert/refigure power differentials. To hide in plain sight by retooling “seeing” to perception/sensing. How much are we perceiving/sensing? How often do we mean perception/sensing yet default to “sight”? Perception/Sensing adds dimensionality that isn’t always articulated with and through “sight” and “seeing”. Ralph Ellison’s identification of “lower frequencies” and J. Halberstam’s configurations of Low Theory do this work. I toy with these multiplicities in the zine. I work low to the ground which means I work close to my heartbeat, my central drum. I work meta; I go beyond. I like to sprinkle codes, tickle clues, tuck in questions, sew in wisdoms so I know what I’m doing, why I’m doing it, who I’m doing it for and to always remember the fun of FLiP (Feeling, Learning, iPlaying).

Some of the works/folks who’ve helped me FLiP are Dana Robinson’s meditative and piercing collages; Zulie’s mind bending, heart wrenching, time suspending zines; Nikki Wallschlaeger’s I HATE TELLING YOU HOW I REALLY FEEL; Seth Graham’s tattoo practice/paintings/unbounded love of outer space (they’ve done 3/4 of my tattoos); Amanda Glassman’s razor sharp poetry and encyclopedic curiosity; L’Rain's music has literally helped me scale the side of a mountain and carried me through hospitalizations; KT PE Benito’s multidisciplinary liberation praxis and collaborative friendship; Zoraida Ingles' holistic creative prowess (a conversation with her is why Heartbeats But No Air, as a title, exists); and Marcus Scott Williams’ writings/video/sculpture work that readily embraces the persistence of ephemera. This isn’t an exhaustive list—I have a solid library of books and papers and zines and tunes at my crib—but, genuinely, I’m inspired by everyone I’ve had the honor to encounter.

There are themes of love and race and beauty and culture and self-transformation in this book. Paired randomly, some pieces may not make as much common sense together, but as a whole, it feels powerful and cohesive. What was the structuring process like for this chapbook? Each zine is different, right?

It is one zine. I find it cool that you consider HBNA a chapbook made up of many zines. The word chapbook had never crossed my mind. I walked into the process with DIY zine logic and HBNA was printed using office photocopiers. I think the feeling of cohesion you mention is what happens when you witness a lot of parts of one person. In this case, you’re witnessing a lot of different parts of me, my thoughts, my actual labor. Whole is the goal ‘cuz people are whole. I am whole. I consider HBNA a single revolution of myself— one big twirl around a fire, a sun. I was in a very strange place. I’d alleviated, with the help of acupuncture and CBD products, a significant amount of the chronic pain I’d been experiencing since August 2014. I fell around love with someone and rose in love to myself (thanks Ms. Morrison and Ms. Stanford!). I was in an unfamiliar painless trance. I created and tinkered with all of those pieces during a very short period of time from Summer 2017 to Summer 2018. HBNA was originally named Girl Pickney (the prose pieces were written under that moniker) and before that NggrGrl (a nod to Dick Gregory). I wrote the poetry in an even shorter period of time—March to July 2018—and the poems are actually part of a full length collection that I wrote in those four months. I didn’t decide on the layout of the zine until I was with two friends formatting it for printing two days before I was going to read at The Strand and sell it. I kept all the pages, the puzzle pieces, in a folder. A lot of book structuring, for me, is based on emotional knowing—when to slap, when to pound, when to breathe, when to confuse, when to stun, when to anger, when to tell, when to soothe. All of my structuring decisions are fly about to get swatted dead but fast enuf to fly away first intuitive. If I’m channeling that intuition, I know I’m in running in the proper heat and lane.

You were in an MFA program at one point. How does this chapbook contrast with your style from before that program and during that program? Did that program have an effect on your writing? This doesn’t feel like the most MFA-y writing, which is why I ask, and which I mean as a compliment.

I’ve attended a few schools. I’ve completed fewer than I’ve attended. Until my late 20s, I was shy and desperate for people, those noun-verbs, to stay. This desire for people to stay meant I spent an inordinate about of time and energy relegating the difficult parts of myself to the margins of the margins and continually stepped into social/academic shoes that did not fit. HBNA was the first fitting of the bespoke shoes I can now emotionally afford to make. The first copies I sold had typos! I misspelled my own pre-name and that’s exactly what I needed to happen. It needed it to happen because I’m full of mistakes and yet! I try! I understand HBNA as a radical refutation of embarrassment. Depending on when you purchased a copy, you’ll see I used white-out to make a few corrections. No two zines are the same; only 80 copies exist. I’m printing 12 more copies (they’ve already been claimed) and then on to new pastures! The zine was printed in three different places (two offices I don’t work in and a local printing shop) and I was lugging around 800 individual sheets of paper that I stapled, numbered, indexed and decorated with stickers by myself…standing barefoot on the carpet of Staples in Co-Op City, listening to Ryo Fukui’s Early Summer on repeat until I finished and then I jetted to the Strand to read. HBNA was how I knew to embody my physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual labor. I’m a goofball with zany ideas, an indifference to external definitions of relevancy, sickled cells and a lot of chaotically grounding love. I write for myself first. Of the school lessons I did receive and learn, there weren’t many I didn’t later disassemble to rebuild, freak unfamiliar or completely misunderstand. J. Halberstam calls this “failing”. Rejigging failure has been such a gift to me. How wonderful! A failure AND still happening? Fuck yeah! I was a wildly uneven student whose knees buckled at mere thought of rigid academic authority. After years of shame and refusal, I can finally admit I am an autodidact. I intentionally get lost and navigate in and to the direction of my own senses. School didn’t teach me to write for myself and that’s who I always have to write for. If that’s selfish, so be it. I am my first audience. If I’m sus of me, then me and myself got foundational problems. I know my writing is non-institutional and that lack of institutional alignment and support, while scary as shit, pushes me to make and take risks to believe beyond the immediate demands/plans/remands of whatever external force I am facing. My writing is constantly colliding into A New I can’t predict. I’m fully committed to unfolding, unraveling, for curiosity’s sake.

What’s a typical day like for you?

My day to day life is as predictable as it is unpredictable. I am formally unemployed and have been for awhile. I live on very little cash and am kept afloat because my mom is a gem and hasn’t kicked me out. My days are 100% influenced by the weather and I spend a good portion of my time negotiating how to minimize the occurrence of vaso-occlusive crises and other complications from the disease I have, Sickle Cell. Between January 2018 and January 2019, I was hospitalized three times. Each hospitalization was about a week long and recovery took significantly longer.

Here’s a sketch of what I call a really great day: I wake up before 10. If the night’s sleep was especially restorative, I can comfortably rise at 8. Depending on how my body feels, depending on how much pain I’m enduring, how much fatigue is shrouding/clouding my faculties, I decide if I have the energy to take a shower. I do the bathroom routine, get a cup of orange juice and take my medications (Endari, sometimes Adderall, Folic Acid). I use the first hours of wakefulness to connect with loved ones via text-phonecalls-DMs and browse the internet for headlines-news-updates-new smiles. I wear my fits comfortable. I call comfort my uniform—upend normcore to body sensible—sweatpants/leggings, pullover, one earring (although I’m leaning to pairs again), handy dandy baseball cap and sneakers. I keep it simple. If the weather is aight—if it isn’t too cold or too hot and if precipitation is mostly at bay and air quality isn’t extremely poor—I go outside and get some living exercise. When able, I take extremely long walks. Once I walked over 50 miles in a week! It’s my preferred form of meditation. Walking/body movement grounds my ADHD symptoms more effectively than stimulants, strengthens my body for potential Sickle Cell episodes and satiates my unyielding need to feel connected to other people. I’m at my best when outside and happening. Illness can create an inescapable interiority. Inside reminds me of the hospital and my relationship with the hospital is, at best, fraught. Walking allows me to follow myself. I engage in peek-a-boo with babies, witness accidents, smile at strangers, duck the eyes of leering people and learn how to love differently too. I go to playgrounds and swing. I take photos and notes. If I’ve got a lil cash, I ride the subway for fun. I poke into shops, admire graffiti and other street signs. I have one woman dance parties on sidewalks. I rest on park benches and read. I pick up grub from hole in the wall spots—you know—I live my life and embrace as much as I can while centering kindness and gentle flow. The walks are my favorite part of my job, which I do not have. When I return home, I rest then get to crafting which I sometimes call spelling. Crafting/Spelling can be anything from adding to my I-Box, spitting verses from the abstract (poetry), spinning short stories, detailing journal entries, doodling, painting, knitting, researching & studying, dancing & stretching, bugging out on Twitter or reading. My bedroom is my studio so I work small yet widely. I intentionally provide myself with many targets so I can a) keep my thoughts and feelings flowing b) find the connections between all of my actions and c) mitigate the stress that sits in the heart of a lone project. I am a multifaceted, multifauceted being. Why not turn on all the taps?

The more long form prose pieces in here have the feel of nice punch-y flash fiction. Are you writing a fiction collection without poems and collage in it? I want to read that, too :)

Hahaha! You’re onto me! Yeah, I am writing another book of poems, a manifesto zine and a collection of fiction. I’ve been writing a collection of fiction since 2012. I had a lot of the difficultly writing the fiction because I was too attached to the title, the characters I conceived needed to grow up with me, and I experienced many years of unremitting and improperly managed mental and physical illness. I was holding onto and telling lies. The shame woven into those lies kept me silent and scared. All of that shit needed to get integrated or dropped. I couldn’t enter the prose/fiction I’m currently writing without learning how to survive myself and the world and bottom-belly-believe in survival too. I’m getting there— healing with primary, secondary and tertiary intentions. Won’t say much about the fiction pieces of than: ~15 stories, lyrically speculative fiction, capital B Black, disabled, and queerfemme parables of creation and destruction and maintenance. My website is in flux but I do readings and performances. Hit me up on Instagram , Twitter or email me at [email protected]. Might take a minute for me to respond because I’m thoughtful yet questionably organized. Now go play, ya’ll!

Unintentionally wrote a poem in the interview. I call it A.B.B in Lieu of A.B.C

beyond

fly, about to get swatted dead but fast enuf to fly away first,

always believe beyond

#joselia hughes#heartbeats but no air#zine#chapbook#poetry#fiction#nonfiction#writing#adhd#sickle cell#verse#abstract#stories#speculative fiction#parables#walking#walks#DIY#ralph ellison#Bruja#prose#MFA

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matthew Bookin

“Honest Days is an unexpected delight. Bookin writes how he sees it — weaving images, dreams, and truth into tight addictive prose. It's a book that captures the haze of the everyday and buffs it into magic.”

-Noah Falck, author of Snowmen Losing Weight and You Are In Nearly Every Future.

“Matthew Bookin is my second favorite dead Russian comedian, and my first favorite living American fiction writer."

-Lucy K. Shaw, author of The Motion and WAVES

How long did it take to write this? When did you know it wasn’t just some unrelated stories but instead a cohesive narrative? Can we call this a novella? Is that OK? I’m OK with it….

I feel very okay calling this a novella.

Fragments of the book were written as early as 2011, but a majority of it was written in 2015. During the summer of 2015 a publisher I really loved approached me about putting out a short story collection. I put one together very quickly and immediately felt like it didn’t work. Over the course of the next six months, I broke the collection apart and turned it into something more cohesive, eventually becoming what the book is now. The book didn’t end up with that particular publisher, but it probably wouldn’t exist at all without their initial interest.

How did you decide on Dostoyevsky Wannabe as publisher for this book? What other books do you like on that press? How did you like working with them?

Dostoyevsky Wannabe was always in the back of my mind as a possibility for the book. I’d been sort of obsessed with DW’s Cassette compilation series ever since it had started and was absolutely in love with the way their books were designed. I eventually contributed to an entry from the Cassette series that Oscar Bruno D’Artois edited and I really loved the experience. After the initial publisher that had shown interest in the book fell through I kind of shelved the book for over a year, opening it up to do a long weekend of edits every few months. In the fall of 2017, shortly after the conclusion of a reading tour I did with some friends, I felt motivated to get the book out into the world again. I sent the manuscript to Dostoyevsky Wannabe and they accepted it less than 24 hours later.

Working with Vikki and Richard was akin to undergoing a very gentle and expedient exorcism, after which a beautiful paperback with a deer on the cover appeared. They’re both incredibly generous and incredibly hardworking. I can’t imagine the book ever having a better home.

Apart from their Cassette series, I’ve really enjoyed Dark Hours by Nadia de Vries, You Are in Nearly Every Future by Noah Falck, and the all the work Shane Jesse Christmass has published with DW.

The novel focuses very much on the everyday and mundane during the first parts, then becomes very absurd and plot-driven in the latter parts. Was this a conscious choice in terms of story development? Or did it happen more naturally? Or was it both? Or neither?

It happened more naturally as a result of its early stages as a short story collection. Most of what I write tends to dip into the surreal, so it’s not something I really consciously make a decision about, it just tends to be the direction I gravitate towards. However, when it was finally complete, I did start editing out some of the more surreal later chapters because I thought it robbed the emotional arc of the book of genuine feeling. Originally there was more sex and more talking animals. And as strange as the book is, I feel like it’s far more tame and straightforward than a lot of DW’s catalogue, which often leans hard into experimental noise punk prose.

What books did you like reading while you were writing this? Did any of them influence you? And if so, how?

The only book I really remember reading during the time Honest Days changed from a collection to a novella is Last Days by Brian Evenson. It’s about a detective who falls into the grips of a cult obsessed with self-amputation. I interpreted the whole thing as a very dark and very funny take on male bonding. Apart from ruthlessly ripping-off its title, I’m not sure how much of an impact it had on my book.

What is your day-to-day life like? What is your writing routine? Or do you not have a routinized schedule?

When I was writing Honest Days I had a schedule that was extremely similar to the narrator’s - I would get up extremely early, usually around 4am, and drive to one of several hospitals in Buffalo to work. The job was pretty much what’s described in the book. Now my life is slightly less ghoulish and a lot more square - I work a pretty standard 9 to 5 office job.

I don’t really have a writing routine. Mostly it’s long periods of compiling notes and fragments of things followed by occasional manic periods of obsessively stringing all the little pieces together.

#matthew bookin#peach mag#lucy k shaw#lk shaw#Andrew Worthington#andrew duncan worthington#brian evenson#novella#novel#fiction#buffalo#honesty#office jobs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sebastian Castillo

Sebastian Castillo’s 49 Venezuelan Novels is a magical book of unique and surreal micro-fiction with a new story on every page. Full of depth and imagination, Castillo uses imagery in a simple yet intense way. From stories of fish markets to spiteful violins, it almost seems that these novels are snippets of family stories long passed down, just now put to paper. With the nature of a born storyteller, Sebastian Castillo provides readers with gorgeous stories.

-from the publisher; buy the book here

How did you plan and edit this book? How did you decide on “49”? How did you decide on “novels”?

I wrote it slowly, piecemeal, like most things I’ve written. I’m not sure when, exactly, I decided to frame them as novels. Right now, I’m remembering how Félix Fénéon’s Novels in Three Lines affected me when I first read it—maybe some of that seeped in. Another big influence was the Borges quote I used as an epigraph: that one could reduce a 500-page book to a few pages. I wanted to push that further by crystalizing a novel in a paragraph, or a sentence. Calling them novels felt right to me—I wanted to believe they were novels, and by believing that for long enough, they became novels. I decided on 49 because the number felt incomplete, like there was something missing which the reader would have to put together, somehow. I wanted to invite the reader to play with me.

There is a constant tension of transition and change in each of these novels. Why is time and its movement so hard for us to grasp?

I’m glad you thought so.

I don’t know if I’ll be able to answer the question well. But I’ll say—one of the things that I’ve struggled with most in my life is accounting for my experience of time. I’ve dealt with a lot of death: several family members, my mother, my friends. I’m sad that things which felt so long, so detailed, so exact, can often wash away the longer you live. There’s entire portions of my life I barely remember! Georges Perec said, “I can’t remember my childhood.” Me neither, and sometimes I would extend that to yesterday.

I had to write my mother’s obituary last year. I was in a state of shock at the time—I think I still am. She was the person I loved most in the world. While writing it, I was heartbroken by how an entire life—with all its flavor and peculiarity—was flattened into a list. It felt both comedic and merciless. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I was drawn to writing fiction: to work in a medium dedicated to damaging time and its dull, insistent violence. If that sounds grandiose and pathetic, it’s because it is. But I have to do something.

There are no markers of products or pop culture allusions in these pieces, and yet we live around popular consumer culture everyday. Why did you decide to disregard these influences in your prose?

There are a few echoes from real life scattered throughout, mostly from my childhood: cheese arepas, Parque Central (the neighborhood where I grew up in Caracas), and maybe one or two other things. I did, however, intentionally limit those real-world markers. I wanted the book, and the world it evokes, to live in a different reality, somewhere between a street corner you can smell and a poorly remembered dream. The “Venezuela” of the book is an imaginary place, I think—one that exists only there.

What is your day to day life like? What’s your work? When do you write?

I’m an adjunct instructor. I teach English and Creative Writing. I used to live in Philadelphia for many years, and I now live in Mount Vernon, NY, where I grew up after leaving Venezuela. I love teaching and hope I can do it indefinitely. In terms of writing: I tend to have periods where I’m working on things consistently, and fallow periods where I’m somewhat ignoring writing. I used to think it was important to write everyday—and I’m sure it is for some people—but I’ve come to accept that it’s not for me. I read every day, and that’s always been more important to me than writing.

What future projects are you working on? Do you see yourself ever returning to this medium of mini concept novels?

I’m not sure if I’ll return to the mini-novel. I tend to build larger projects off a formal conceit, and am frequently prone to starting new things and never finishing them. So I think, at least for now, I’m done with them.

I’m almost finished with my next book, Not I, which is in the tradition of formalist autobiographical texts—things like Joe Brainard’s I Remember, Édouard Levé’s Autoportrait, and Lyn Hejinian’s My Life. I take the 25 most common verbs in the English language and run them through every verb tense with a first-person statement. Here’s an excerpt, from the Simple Future section:

I will be something very small.

I will grow into jealousy.

I will do what has to be done.

I will say plain, nasty things.

I will get what I want.

I will make do.

I will go to the poet’s moon.

I will know too much about the government.

I will take out the trash.

I will see Atlantis, but not for a long time.

I will come when called by my lord, unfortunately.

I will think about serious illness.

I will look up my own skirt.

I will want more when I’m rich and lonely.

I will give coal to both friends and traitors.

I will use your porcelain bathtub now.

I will find the things you’ve been hiding from me.

I will tell your secrets to nationally distributed magazines.

I will ask for nothing in return.

I will work until I can get away with doing nothing.

I will seem suspicious, but please trust me.

I will feel that terrible pressure.

I will try a new path.

I will leave you with this.

I will call the police on myself.

I started working on it a few years ago as a bit of a diversion. But what began as an Oulipean/conceptual exercise became, at least for me, something exciting and playful. I hope to publish it at some point.

The other thing I’m “working” on: an audio commentary for 49 Venezuelan Novels called “The DVD Commentary of 49 Venezuelan Novels Deluxe Edition.” Remember those commentary tracks that used to come with movies on DVDs? Maybe they still have a version of that, but it’s been a while since I’ve seen one. I always liked how they created a separate experience, something distinct from the original movie—watching someone watch something. So I’d like to do a version of that with the book. My plan is to disparage the book and the person who wrote it.

#bottlecap press#andrew duncan worthington#Andrew Worthington#fiction#venezuela#novellas#dvd#english#creative writing#time#change#transition#sebastian castllo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Wehrenberg

Richard Wehrenberg was born in Akron, Ohio and is the author of Abracadabrachrysanthemum (2018), Hands (2015), and River (2014), co-written with Ross Gay. Their work has been published in The Academy of American Poets, Peach Mag, Bad Nudes, Monster House Press, & elsewhere. They are a poet, writer, artist, & designer living in Bloomington, Indiana.

I want to start with the cover. I admire its minimalism but also the way that minimalism allows the title to speak for itself, carrying the reader along as they go to the next page. What are some of your favorite book designs? How has your own design aesthetics changed since you first started designing chapbooks and websites over ten years ago? Do you have any sort of codified process for your design work?

I perceive Text as Image and Image as Text, in a kind of infinite stirring/reworking. My aesthetic/process for design feels necessarily influenced by how my specific body-form perceives/reads the world, via its various miracles and supposed ‘deficiencies’—ie. having one barely-able-to-see (left) eye and one incredibly-over-achieving (right) eye, as well as having benign hand tremors (ie. my hands shake, inexplicably). I understand designing as the praxis of ‘de-signing' (ie. removing the signs from) this Earth/traditions/meanings/images. To quote one of my fav poets, Mahmoud Darwish—“I love your love / freed from itself and its signs,” which to me means: I love you ‘best’ when we shed the layers/masks/images that bury us in stories, when we dwell in our original and base-form—which of course has to be, for me—Love—the desire to see the world as un-riven, as One, despite everything working against the infinite forms love embodies. I feel my design aesthetic as ‘spiritual,’ or at least to me it feels like it springs enigmatically from a spiritual impulse/condition/base. All to say—my style/praxis is mysterious, even to myself, and my design depends on this kind of unknowability/improvisation. For Abracadabrachrysanthemum (and Three Crises by Bella Bravo, which share almost identical design elements), I viewed the circle on the covers to be a kind of gravitational wormhole into the book’s work, like you implied. A simple entranceway that has, like a planet or black hole, its own gravity to pull/cull others in, to merge and connect worlds. As far as design influences—I love love love Quemadura’s work (who you probably know as Wave Books’ designer.) I remember seeing their stark, simple, text-based covers as a younger poet/designer and being moved by space they allow for the text (exterior and interior) to become its own image/meaning apart from other visual suggestions. Also, Mary Austin Speaker’s work—who does design for Milkweed Editions—is always so precise, gorgeous, and enchanting. Outside of the poem-world, I am constantly inspired by fellow Bloomington designers/friends Aaron Denton and Sharnayla. The beauty they channel is astounding. Since I began designing, I feel that I’ve just become better and faster at designing, and my core aesthetic has mostly stayed the same. Being self-taught, you kind of just pick up little preferences, skills, and potentialities randomly along the path of work. I’m in a constant state of knowledge-acquisition re design and thus my process is really just experimentation. One codified process I do have is to meditate on a book’s content, to summon its image by intentionally dwelling on it within an unconscious states of meditation, dream, trance, etc. Usually I can call up a color palette, or image/font/et al that each individual book/design is calling for via these means. I believe in this kind of prayer/listening in my work, and I cite the unconscious as my main source of artistic capacity and production. I’ve also dreamed book covers before. That’s the best.

Many of the poems in this collection have geographic allusion, descriptive precision, and a general sense of place becoming character. This reminds me in many ways of your book RIVER, co-authored with Ross Gay. While that was prose and this is poetry, this is something I have noticed in your writing. How would you describe your aesthetic connection to geography? nature? environment? This book seems to expand beyond America in ways previous writing of yours doesn’t...

I can’t not attempt to constantly locate my Self in this World—can’t not see/feel/attempt to understand where/how/who/why I am in relation to ‘others’—to the land, rivers, oceans, to other animals, to the incredible manifold instantiations of plants, to the water with which without we would vanish, to all the ostensibly separate “I’s” on this shared Earth/consciousness/World surviving, dwelling, praying, creating—Being. I am an empath and embed/imbibe my surroundings almost automatically/unconsciously into myself. I become wherever I am. And thus its violences and gorgeousnesses alike become my own. And thus I speak for them, to them, of them, with them, in service and toward the healing of them/us/I/we. I unbecome my self to reset my churning and lumbering around this planet, to geographize ‘my’ position within this unpositioned House we find our selves. I am also quite of the mind that we are indeed both Here and Not Here. This Not Here is completely devoid of the drama of the body/ego, which we so often encounter and identify with today (and have since arriving on Earth.) My body, it’s specific forms and desires, languages and impulses, with yours, in conflict with theirs, with the scarcity, the low amount, the abundance, the never-ending forsaken nothing-everything, all of it, all the time, ever, ever, never-enough or always-too-much, the never-quite-right. You compared to me, thine in yours with mine of we. In spirit realm, there is no time and ID like we think here. Both Here and Not Here are real/valid places—the corporeal realm and the spirit realm—and I know, at least for now, I live in both places. I realized recently one of my main hopes for my writing is for it to re-embed the divine into the every day, re-pair it with the quotidian—to reunite these worlds-torn. What I mean is: I identify heavily with wherever I am in this 3D reality called life, and also identify heavily with the spirit realm as an (un)geographic place where I also reside. Over-identification with either realm leads to misery/suffering or disassociation/location, to paraphrase A Course In Miracles.

There is a sense of unity between the voice of these poems and everything else in the world, seen best, in my opinion, in “Signifying Brown Bear” wherein a stuffed animal becomes a virtual tunnel into all sorts of real human and existential experiences. Do you think something fundamental has changed in contemporary consumer society from ancient or medieval or even early modern societies, in which we have too many outlets for our emotions and experiences? Maybe too many is good (whatever "good" means)? In this poem, the stuffed bear almost represents your own yearning to connect as fully as you already are with universe around you. It has many of the conceits of a love poem and, at times, a tongue-in-cheek tone. In the end, the poem is what makes us think. You have turned a mirror on the reader. Was this your intention? How do you decide when to write in second-person versus first person etc.? Is any of this interpretation at all on point? In “Signifying Brown Bear,” I am referring to an actual brown bear (ie. Ursus arctos) and the poem is just kind of about how people/entities who I become close with can begin to feel like sweet-tender-almost-cryptozoological-creatures to me and I want to also just be a sweet-tender-almost-cryptozoological-creature—or hell, I’ll settle for even a plant or a rock—back to them. Anything but this warbling, incomplete, stammering-maunderer of a human being! (Exaggeration.) I do not want my humanity at times—my human-being-ing—which has been categorized, documented, and shrink-wrapped for societal use and relation, who is part of the decimation of Earth via capital. I want the freedom (and I’m sure we could say unfreedom) of the brown bear who is in relation to the Sycamore by the river, and the salmon floating above the stones, the water gliding over, ever-thinning rock into sand granules—slowly—and back again—and back. I don’t want to be (and can’t be, is perhaps my thesis) relegated to the realm of signifiers and signs imposed via any of the manifold categorization machines we navigate on the daily to obfuscate these kind of otherworldly, ancient connections I feel as Real. To decimate that last paragraph—I also believe in becoming fully-embodied/present in the form we are in in this life, too. So, it’s confusing, this ever-always-transforming-ing perceptioning. The confusion about what energy/thing I am and what you are is a little about what that poem is about, too. I was reading Agamben’s The Use of Bodies and came across this ancient Greek word, poiesis, which appears in the poem and means, “the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before.” I love that idea, and think it is what we are here to do, in part. So often for me the unprecedented-something we are trying to bring into existence is ourselves and the art/energy we carry in us must be made into song. I want to always make the reader aware of their presence in my writing—to me writing is a collective act and readers are always existent, even if they never ‘read’ your work. The imagined, the dead, the unborn, the spiritually uncanonized, the already-gone-never-was reader, writer, seeker, be-er. I switch between tense often and freely, because in poetry, at least for me, we feel/fall into each word/line we write and there’s less of a need to be ‘coherent’ in the sense of the popular notion of storytelling/fiction, which (I might have another thesis here) feels like a symptom of capitalism, too. Of course it feels really nice to have a coherent story. I love television and pop culture. I want to write for television. I want to be perceived as coherent. But I want to say too: the ‘incoherence’ of poetry is a kind of coherence, a prayer toward a ‘new’ form, if you will, despite being so old itself. Poetry coheres to a perhaps more experimental way of telling a story, a precedentless next-ing, and this variation is vital—these unforeseen forms, stories, ways of being. We are a species that evolves, and because the mouth/mind is the site of evolution now, I am playing accordingly.

What ended up happening with MHP? Why did you decide to stop active involvement in it? What are you doing now in terms of day-to-day life? Monster House Press has evolved through many forms. In 2010, it began, semi-naively, as a collective publisher of zines and chapbooks in the eponymous punk house. It then expanded and evolved into a project I was maintaining, mostly on my own, from 2012-2016 in Bloomington, Indiana. In the summer of 2016, MHP rose again as a officially collective project—an amorphous mass, as we liked to call it—primarily because the workload had become unsustainable for me to do on my own, and we were doing more and more, gaining recognition, et cetera. We decided to lay MHP to rest at the end of the 2018, as many of us involved in keeping it going are moving onto graduate school and/or starting new projects/lives. It felt apt to end this specific instantiation in my career-form of publishing, as I have moved away from the punk/DIY scene from which it was born, and the name itself has too become divorced from its origin and who I/we was/were then. I’m sure I’ll always be editing, publishing, reading, designing and helping steward others’ work in this world, as that impulse is something part and parcel of my being, this collaboration; however, the terms and boundaries within this specific modality as MHP have expired to me. In my day-to-day life, I am a freelance graphic designer, artist, editor, and writer. I usually sit at my house with my dog, working on whatever project I have in my docket at the time, or go out to a coffee or tea house to do work. I also just finished auditing a graduate poetry workshop called Joy & Collaboration with Ross Gay, which was, in a word, divine—and I currently spend my days/time helping out with the growing at a communal greenhouse as well as generally just reading/writing/watching/listening to the Earth/Universe, hoping to be of service, use, and care.

What future projects are you working on? Do you still play music with organized groups? Have you thought of writing long-form fiction?

I’m hoping to start my MFA in Poetry next year. As far as writing projects—I’m writing a collection of sonnets about my alcoholism/being an alcoholic in the United States. (I’ve been sober for 5 years now.) The sonnets are these kind of little, tender love-songs to my alcoholic/former self (who I can never fully extinguish) which—I hope—also reckon with and help shed light on addiction, malevolent masculinity/whiteness, and which also seek to forgive and release—to heal. I also have this big, kind of far off ditty of a dream to open a Poetry Center one day, in the Midwest ideally, kind of a little like Poets House in NYC, where events, workshops, reading, writing, and magic can happen. A hub for poetics/healing/joy/collaboration. There will probably be an herbal/plant element too, somehow, as I love working with/growing plants. And music! I haven’t played music in an organized group in a while, but enjoy being able to play piano and saxophone here and there, when I can, however that happens. I helped transpose, sing, and record a score for a little art movie project, along with Ross Gay and Lauren Harrison, which was super delightful. Music is the literal heart of the world, imo. I listened to 36 days of music this year, ie. for 1/10 of the year I was listening to music, which was kind of staggering and incredible for me to realize. I love writing long and short form fiction, but have found it removes me from the world too intensely, which, I feel I am supposed to stay more rooted/involved in the World in a proactive sense, so I tend to write poetry and other forms over fiction. I am interested in the hybrid essay form—with poetry hidden inside—and creating/seeking new hybridized forms. There’s so much potential for greatness—and so much to come.

#richard wehrenberg#monster house press#hybrid essay#fiction#poetry#ross gay#lauren harrison#music#midwest#mfa#graphic design#wave books#andrew duncan worthington#bloomington#indiana#cleveland#akron

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter BD

as the young man gazed up at the eclipse

he thought

“damn, i’m looking at

the

eclipse”

So begins acclaimed poet Peter BD's dizzying journey into the depths of the textual Self, in which reflexive phrases play off one another like a thousand points of light shining through a fifth of cognac and illume the striving and conniving which defines our current moment. From treatises on chicken to the moral quandaries of Winona Ryder, touchstones of the Now seep through Peter's verse like osmosis like milk through lace like the blinking of your fifth eye. Buoyant humor and steely irony mix together to form a wild combination which goes down easy but lingers with you for the rest of the day.

BUY IT TODAY FROM INPATIENT PRESS

How many of your famous/infamous email letters have you sent out? By your estimation, what's the ratio of positive to negative feedback you have received (could also throw in neutral)? Or is it hard to categorize them as such? What are the most wild responses you have ever gotten? Define 'wild' as you will.

i'm not sure how many stories i've emailed people. i've never kept count. in the beginning i'd write a lot of people things but don't do it now as much as i used to. all i can say is that it's probably a big number overall. or maybe not. sorry for not being able to answer this one. feedback to the stories is either positive, neutral or no response at all. i'd say it's about 60% positive and 40% neutral. this is just going on my responses in my inbox. i don't have any social media besides twitter so unsure what the overall reaction is, if there is any. no one really replies to me in a negative way. i remember one person corrected my grammar once which was funny. i think my most memorable negative response came from you. i sent you a 3 part email and here was your response: FUCK YOU ASSHOLE STOP SENDING ME YOUR FUCKING EMAILS ITS FUCKING FICTION I HATE YOU PEOPLE JUST KIDDING ABOUT ONE OF THOSE PARTS NOT ALL OF THEM FUCKING ASSHOLE I AM UNIMAGINATIVE I STALK PEOPLE GIRLS BOYS WOMEN MEN ANIMALS PLANTS SO FUCK YOU DID YOU HACK MY EMAIL PLEASE DONT IM SORRY I LOVE YOU PLEASE LOVE ME BACK this was one of the most memorable responses because it's around the time i first started doing this and also because it's wild. i guess it's more wild than negative. whatever it is i enjoyed it. i don't receive too many wild responses but one i did enjoy was when this artist named jacob sanders wrote a song about me. i was working this shitty job and was up at 5 am when i received it. it just talked about how i can accomplish whatever i want or something like that. i was really happy at work that day haha. it made feel really good and humbled that someone would do that for me. i think someone sent me a dick pic once. that was wild. another person responded to one of my stories with a story of their own about me that was thousands of words. that was wild as hell.

What was the writing process like for your recently released book? How did you decide on your publisher?