#2020 bookend review

Text

Album Review: 'RAVEN' - Kelela

It’s hard to believe that Kelela, the future-pop auteur who gave us one of the best tracks of the 2010s with ‘A Message,’ would be feeling ‘rusty’ after releasing her critically acclaimed 2017 debut, Take Me Apart.

Partly blaming ‘capitalism’ and ‘white supremacy’ for her creative block, she explained in an interview with the Guardian:

‘Perfectionism, I would say, is one of the central components of the culture of white supremacy […] There’s a way that perfectionism can distort where you’re at,” even if you have “the juice” and are already good at what you do. This idea that: ‘I should be generating more. I should have a larger audience. I should always have more than what I currently have.’

The Ethiopian-American singer soon committed to a personal and creative overhaul. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020 and the waves of Black Lives Matter protests that soon followed, Kelela re-evaluated her professional relationships, sending out a series of letters to industry colleagues outlining her aims and desires as a Black artist. Some contracts were ended earl and a few working ties severed as a result.

Her latest album, RAVEN, continues with this rebirth.

Where Take Me Apart boasted sleek, glossy cuts of throwback RnB, RAVEN confines itself to dark corners and sweaty dancefloors, placing Kelela’s biggest supporters – queer, Black femmes – front and centre.

Tension hums brilliantly beneath undulating basslines and smoky, simmering beats, feeling both subterranean and surreal.

‘Time is surreal, now I'm floating in outer space,’ she sighs on ‘Contact,’ vaporous synths drifting under her bittersweet tone, while first single ‘Washed Away’ turns an ‘ambient heart-check’ into a hypnotic baptism, Kelela finally born anew.

Water is a common motif found throughout RAVEN, whether it be the singer washing away the past or the ‘floody nights’ that pour through her mind on finale, ‘Far Away,’ providing the perfect bookend. Even the drowsy and sinister ‘Fooley’ sees Kelela literally submerged in sound, beats stuttering in the watery gloom. It echoes the album’s ephemeral nature – slow, serene, meditative, where hazy synths float atop liquid basslines.

In contrast, Kelela’s love is restless.

‘But we're too far away,’ she calls out on the garage-indebted ‘Happy Ending,’ ‘I'm reading all the writings on the wall.’ Her longing rolls into the late night cool of ‘Let It Go,’ the singer vibing over punchy drum fills and a soft thrum of bass. Later, she’s ‘On the Run,’ proclaiming ‘I'm ready, but you're takin' too long’ as her insecurities start bubbling to the fore, while on the smoky and hypnotic ‘Closure,’ she gets completely ghosted by a lover.

Cuts like ‘Holier’ and ‘Bruises’ hint at more romantic discord, Kelela not willing to assist in a lover’s self-destruction on the latter, which nicely leads into the glitchy, bass-fuelled melodrama of the title track.

By the time we reach current single, ‘Enough for Love,’ her transformation is almost complete – rougher, stronger and more than prepared to go it alone. Rather than a breakup narrative, RAVEN presents a journey of self-love, the singer embracing identity, friendship and sexuality and the dancefloor in equal measure. ‘They tried to break her,’ she notes halfway through her catharsis. ‘But there’s nothing here to mourn.’

RAVEN is not so much an album but a seductive and sprawling moodboard, assembled with the help of a cooler-than-cool team of producers, including Bambii, Kaytranada, LSDXOXO, Junglepussy and Asmara of Nguzunguzu. It’s something to luxuriate in and might a few listens to fully absorb.

At its best, it’s heady and seductive, creating an otherworldly vibe that’s ripe with heat and lust. Other times, though, it’s to the album’s detriment, resulting in quite a bit of filler in the second half that lurches towards the finish line.

RAVEN also could’ve done more to represent Kelela’s target audience. Other than the addition of trans rapper Rahrah Gabor on ‘Closure,’ there’s not much here to suggest that this album is for the queer, Black femmes in the front row. It really feels like a missed opportunity to showcase more of the LGBT+ talent that’s currently dominating the dance, electronic and alt-RnB scenes.

Hopefully, with future releases, Kelela will realise this vision more and more. But right now, it’s just good to have her back, more polished and rejuvenated than ever.

- Bianca B.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don’t know about you.

Another year, another round up that I felt obligated to write since I basically abandoned this whole thing in 2020. As we are on the cusp of ‘23--I wanted to share some of the things that made ‘22 worth living. Personally speaking, I’m saving about 90% of this year for my memoir; it was a weird one filled with a lot of firsts! Culturally speaking, Will Smith slapped Chris Rock, I finally watched Heat, and we all learned the word polycule.

Let’s get down to business, what did I read, listen to, watch, and generally consume that was noteworthy this year.

Books

I didn’t read as much as I wanted to this year, but two noteworthy novels I finally got to were Mating by Normal Rush and Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzburg. Of contemporary fiction, I was happy for the return of Selin in Either/Or and bookended my year of Emily St. John Mandel with Sea of Tranquility.

Music

Do I even need to say that my most listened to artists of 2023 were Paul Simon, Niia, John Coltrane, Prokofiev, and Steely Dan? However I did also enjoy the new Beach House, of course I listened to Benito and Steve Lacy, there’s too much Antanoff out there but The 1975 seemed to tamp down his worst impulses, and after REAISSANCE came out I stopped playing Break My Soul on repeat and now am a Virgo’s Groove bitch.

Movies

As I noted up top, I plugged a lot of holes in my viewing history this year. Shout out to Blank Check and the Big Pic pods for keeping me in the loop. Movie content and analysis for 2022 is abundant (just see: Fran Mag’s 2022 wrap up), so all I am going to say is, “Hi, I’m Petra’s father.” Oh also: Jenny is the MVP of Banshees or Inisherin, and Eyes Wide Shut.

Podcasts

How Long Gone... How Long Gone? How Long Gone. It turns out I’m exactly that insufferable. I didn’t buy any merch, and I didn’t see them live--but I thought about it, which is bad enough. Besides that I started listening to Celebrity Book Club and I did go to a live taping of Odd Lots. I shed a ton of crooked podcasts (and it feels great). Sorry, but I need smooth brain.

TV

Speaking of smooth brain, White Lotus season two was the perfect mix of stupid and interesting to keep me totally absorbed. Shout out to my GOAT F. Murray Abraham and perfect Italian American Man Michael Imperioli. Both were underutilized. Industry season two was the fish t-shirt representation I needed. The Bear was exactly how I cook, so that’s cool. I finally caught up on Barry; my friend and I binged The Dropout during a bomb cyclone while we were in North Adams; and just like that... we got an SATC sequel (remember that?! It was terrible).

Odds & Ends

By far the most notable point of the year in culture for me was Opulent Tips, Rachel Tashjin Wise’s invite-only newsletter (*flips hair*). Her perspective on style and library of references are neither snobby nor abstruse. She loves self-expression and is generous with her advice. Blackbird Spyplane finally helped me to understand WHY EVERYTHING LOOKS LIKE PUTTY NOW. If you’re not getting your croissants at Brauð & Co in Reykjavik, what are you even doing there? I made a few art acquisitions (quite possibly a cheap Picasso lithograph and a limited edition poster from The Paris Review) my exposed brick looks so Brooklyn it hurts. Out for 2023? West Elm everything ... In for 2023? Taper candles, mercury glass vases, continuing to pile up the LRBs.

That was honestly just a small fraction of the year... but like every year, it’s impossible to pinpoint when the vibe shift happens. It was a weird year! I hope the one to come is filled with even more adventures (I’m going to Switzerland!), fantastic meals (did I mention I got to buy out Laser Wolf for a work event?!), and grailed acquisitions (I FINALLY got a Mimi Vang Olsen x NY Humane Society t-shirt!!!!) for all. I’ll leave with one final note for 2023, we’ll see if any of it comes true.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

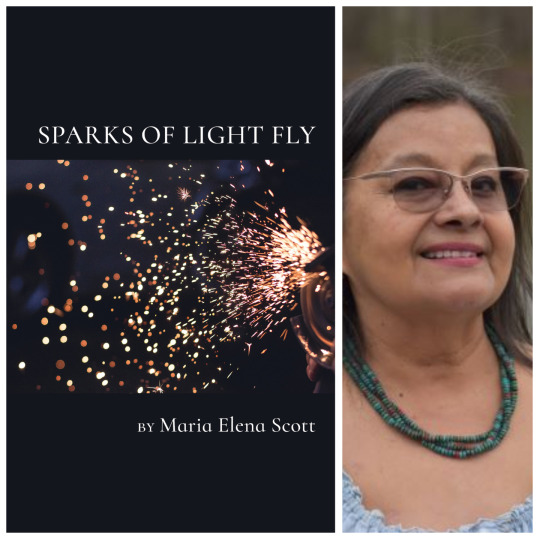

FLP CHAPBOOK OF THE DAY: Sparks of Light Fly by Maria Elena Scott

ADVANCE ORDER: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/sparks-of-light-fly-by-maria-elena-scott/

Maria Elena Tormey Scott is a Mexican American, bilingual writer and poet. A graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison in Education. Former bilingual educator for 25 years Her works can be found in the following: Come Be A Memoirist-Woodland Pattern’s Creativity and Aging Anthology (2010) Each Ear Hears A Different Meaning: Voices of Woodland Pattern’s Wednesday Writers (2013) Great: Poems of Resistance and Fortitude, devoted to November 9, 2016 (2017) Yellow Medicine Review-A journal of Indigenous Literature, Art and Thought (Spring 2019) and (Fall 2019) editions. English Only Has Twenty-Six Letters, an essay published on-line in South Florida Poetry Journal (February 2021.) Frost On the Chrysanthemum- a poem published in Riverwest Currents (September 2021) Love Letter To My Brother Juan, a Memoir In Prose, Poetry and Found Text (February 2022) He Always Climbed Back-an excerpt from Love Letter To My Brother Juan published in Riverwest Currents (March 2022)

PRAISE FOR Sparks of Light Fly by Maria Elena Scott

Sparks of Light Fly shares the full emotional range of a profoundly empathetic speaker wondering “what kind of night-time is it” when we live in a world of “constant pleas for miracles.” These are poems of personal reclamation, social responsibility and belonging, connection with the Earth, hibiscus flowers and “Sister Ocean,” and the urgency of injustice’s many dimensions. “I am your beloved dancer,” Scott writes. “In all directions // Light / Transforms.” There is enough sweetness in these poems to face their sometimes-gutting, necessary truths.

–Freesia McKee, Author of How Distant the City

Bookended by haiku in this collection Maria Elena Scott’s poems ring with music, “sonorous roaring sounds,” and pull you in like the waves of her many ocean odes. Her poems on injustice for families separated at the border, for survivors, among others display the poet’s big heart. Nature runs throughout and the connection the poet makes as in “Fragile Beings Sacrificed,” keeps you in a state of wonder.

–Angela Trudell Vasquez, Author of My People Redux and Madison Poet Laureate 2020-2024

Please share/please repost #flpauthor #preorder #AwesomeCoverArt #poetry #chapbook #read #poems

#poetry#preorder#flp authors#flp#poets on tumblr#american poets#chapbook#leah maines#women poets#chapbooks#finishing line press#small press#book cover#books#publishers#poets#poem#smallpress#poems#binderfullofpoets

0 notes

Photo

NOW IS NOW Nanna Hänninen @nannahanninen Published by @kodoji_press in 2020 Time is the given in Nanna Hänninen’s conceptual photography practice – as it is in all photography. Photography records an instant and marks too that it has passed and is gone. Furthermore, Hänninen’s book NOW IS NOW and the exhibition it accompanied, ‘How about the Future’ at Serlachius Museums Gösta in the pandemic year of 2020, are marked by her investigation of how we conceive of and comprehend time. NOW IS NOW is composed of images by Hänninen, both her own source images and sculptures and works based on found images, interleaved through a text by Finnish philosopher Tuomas Nevanlinna and bookended by an excerpt from curator Laura Kuurne’s essay on Hänninen’s work. Hänninen is moved by climate change to review how we look at the future; her work expresses the urgency of rejecting the methods we habitually employ to consider history and time passing. Instead, she fashions experimental models of what might be to come. "Paging through the book, which fits neatly into the reader’s hand, one encounters a reflection on how the understanding of time has developed in Western thinking, how it might be otherwise, while looking at images marked by their transience, such as sculptures braced around blocks of ice, historic photographs or further works that illustrate an action in two parts." Come Read @bungee.space #nowisnow #nannahänninen #howaboutthefuture #kodojipress #bungeespace #3standardstoppage #3ssstudios (at Stanton Street) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgxoBkvlFDt/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution

Julius S. Scott

Verso, $24.95 (paper)

Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

Vincent Brown

Belknap Press, 2020, $35 (cloth)

The Bloody Flag: Mutiny in the Age of Atlantic Revolution

Niklas Frykman

University of California Press, $32.95 (cloth)

The Age of Revolution (1770–1850), bookended by the American and French Revolutions on the one side and the Revolutions of 1848 on the other, is widely viewed as the progenitor of the modern Euro-Atlantic world. Its intellectual energy fused the liberal and republican ideas of John Locke with the ideals of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment; its political energy fed off the struggles between the bourgeois and their aristocratic enemies. Although visionary hopes could meet crushing defeats—as they did during the popular risings of 1848—by the end, there were new parliamentary regimes, emerging nation-states, declarations of rights, and the eruption of an industrial age.

And yet, this classic narrative leaves out the most radical of the revolutions that exploded neither in continental Europe nor in North or South America, but in the Caribbean, on the island the French called Saint-Domingue and the victorious rebels would call Haiti (Ayiti), after its indigenous name.

Until recently, the Haitian Revolution and other Caribbean slave rebellions have been treated as sidebars to the Age of Revolution. In part this is because of a Eurocentrism that has long diminished the role of Black people in shaping history. But equally important, enslaved people didn’t fit an accepted image of political actors, and thus it was difficult for historians to see them standing alongside the signers of the Declaration of Independence in America, the Jacobins in France, the Bolivareans in Gran Colombia, the Mazzinians in Italy, or the Chartists in England: envisioning, allying, struggling, surmounting. This, despite such works as C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution and W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, which left little doubt about the political capacities of enslaved Blacks.

Nowadays, Eurocentrism is called out for its parochialism as well as its veiled racism. Historians are much more attentive to questions of empire and colonialism, so they place the events of the Age of Revolution in a much broader context. Circum-Atlantic and transnational histories abound and have exerted enormous influence on eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century studies. The Haitian Revolution has itself been the subject of a rapidly growing scholarship, whether looking from the Caribbean out or from the Euro-Atlantic in. And there has been renewed interest in slave systems, the maritime world, and their relation to the development of capitalism.

Still, it is not entirely clear how the pieces of this newly expansive story come together: how we may reimagine and reconceptualize what the Age of Revolution would look like if viewed comprehensively from below and from above, if portrayed with a much larger array of political actors and a much greater sense of the scope and ambitions of international as well as local politics. And if understood as coinciding with—indeed, deeply interconnected to—an age of emancipation in which the most powerful slave regimes in the world were overthrown despite hesitation among Euro-American revolutionaries themselves. The three outstanding volumes under review here offer the materials for just such a reconsideration.

The Common Wind (its title taken from William Wordsworth’s ode to Toussaint Louverture) is a pioneering contribution to our understanding of the place of Haiti in the Age of Revolutions. A revised version of Julius Scott’s 1986 doctoral dissertation (its publication delayed by unexpected circumstances and a determination to get the story right), the book is less about the Haitian Revolution per se than about the circulation of ideas and experiences that both lit the fuse and then sent the explosive results across an immense space. Indeed, Scott’s is a multinational history that suggests how the revolutionary years from 1780 to 1815 might appear if Saint-Domingue and then Haiti were recognized as a hub around which the politics of the period radiated.

Arguing that the commodity-producing slaveocracies of the Caribbean were major sites of trade and migration, Scott draws our attention to the ports rather than the plantations, to the seas rather than the land, and to the “masterless”—sailors, free people of color, runaways, maroons—as much as to the enslaved. They are the keys to understanding how news, rumors, information, and ideas flowed across the Atlantic and around the Caribbean: the ever-thickening veins of commerce that linked Nantes and Bordeaux to Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien), Port-au-Prince, Havana, and Kingston. These trade routes brought thousands of vessels and maritime laborers into the harbors of all of these cities; they also brought fugitives and veterans of battle. Two of eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue’s rebel leaders (Makandal and Boukman) fled there from Jamaica. Henri-Christophe, another leader, was born in St. Kitts. He, Andres Rigaud, and Martial Besse, free men of color who became military leaders, served with the French forces at Savannah during the American Revolution.

As a result, the enslaved and the free people of color in any one place learned of history’s unfolding elsewhere and transformed the languages of revolution that they heard—and, in some cases, read—into their own political vernacular. The radicalism of the Age of Revolution, as Scott so brilliantly shows, was invigorated as it moved from France to Saint-Domingue and then to Jamaica, Cuba, and back. The visions of the Jacobin Republic in France and of the slave rebellion turning revolution in Saint-Domingue were both mutually constitutive and ever expanding.

Like a stone that falls into the water, the rebellion in Saint-Domingue, as Scott demonstrates, had ripple effects going in multiple directions: to other Caribbean islands, to the South American mainland, and, perhaps with greatest effect, to the United States. Beginning in 1793, thousands of slaveholding emigres, their slaves often in tow, headed out of Saint-Domingue to whatever port might offer a measure of safety. Well over 10,000 landed along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America, settling in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, Savannah, Pensacola, Mobile, and especially New Orleans. With them came vital news of rebellion in Saint-Domingue that sent fear through the minds of American slaveholders and hope through the minds of their slaves, who quickly learned that the wealthiest and most powerful slave regime in the world had fallen before the might of their enslaved counterparts.

The consequences would be enormous for the social and political history of the Western Hemisphere and Euro-Atlantic and particularly for what was about to become the new center of the slaveholders’ world: the U.S. South. The rumblings from below were already apparent in the 1790s with slave conspiracies in Louisiana, and then, in the early nineteenth century, with the aborted Gabriel’s Uprising of 1800, the St. John the Baptist Parish revolt of 1811 in Louisiana, and the Denmark Vesey conspiracy of 1822 in Charleston, all of which showed either the direct influence of the emigres or secondhand knowledge of what had transpired in Saint-Domingue. As the cotton economy spread across the Deep South, the enslaved laborers who were driven along with it could now know that slave systems were not cast in stone and timeless, that they were vulnerable and could be destroyed by people like them. As we have come to realize, owing to Scott’s groundbreaking work, there is no way of understanding the history of the United States during the first six decades of the nineteenth century, and especially the emancipation process during the Civil War, without acknowledging the political shadow cast by the Haitian Revolution and the political roles played by previously unrecognized actors: the masterless of the Atlantic and the enslaved workers their enslavers thought they had mastered.

///

During the Haitian Revolution, the rebel armies under the command of Toussaint Louverture not only toppled the slaveholding class of Saint-Domingue; they also defeated the armies of Britain, Spain, and France to secure their victory, freedom, and eventual independence as the Republic of Haiti. Slave rebellions, together with the quotidian struggles in which enslaved people engaged, were nothing less than warfare. And although this might seem apparent on considered reflection, few scholars have taken to the idea and its meaning for the study of slave regimes. Vincent Brown is a notable exception. Slave warfare is one of the central conceptual points in Brown’s extraordinary book on Tacky’s revolt, the massive Jamaican slave rebellion of 1760–61. Indeed, Brown sees the rebellion as more than an episode of Jamaican history and internal warfare; he sees it as part of a multilayered set of wars that encompassed both sides of the Atlantic and involved empires in Africa and Europe. Combining meticulous research in a multitude of national archives and the use of new technologies for visualization, Brown has produced one of the best treatments of slavery ever written.

Enslavement, Brown reminds us, did not simply begin in West Africa and get redeployed in the Western Hemisphere. As a system it was in constant motion, embracing people and states on several continents, trade and commercial relations crisscrossing the Atlantic, and—notably in the eighteenth century—almost continuous warfare as well as brutal regimes of exploitation. Owing to Brown’s success at identifying many of the enslaved participants in the events he recounts, we are able to see how the rebellion in Jamaica was very much an extension of wars erupting in the West African interior, propelled in many cases by the demands of European trade, and involving Africans who went into battle in both places.

Jamaica was Britain’s most lucrative colony and its most formidable military base, a virtual “garrison government” devoted to keeping enslaved laborers in subjection, fierce maroons (fugitive slave communities) in check, and rival empires at bay. The sugar plantations, where half of the enslaved Africans toiled, often took on the appearance—in their architecture and placement—of fortifications, and the work regimens on them showed military-like cadences. Between a half and three-quarters of Jamaica’s slaves in the mid-eighteenth century were African born, often veterans of West African wars, and thus quite aware of the broad context in which their enslavement occurred. Many of them had been forced aboard slave ships along the Gold Coast and became known as Coromantees (perhaps from the English post at Cormantyn), though they had generally been taken captive much farther inland and belonged to a number of different ethnic and linguistic groups. The Coromantees had reputations for their strength, skills, discipline, and rebelliousness: they were simultaneously prized and feared by their enslavers.

With attentiveness to the multiple sources and contending narratives, Brown demonstrates that what the British would call “Tacky’s revolt” was only part—a small and abbreviated part—of a larger “Coromantee war” that engulfed Jamaica for months. Although it is difficult to uncover the scope, timing, and objectives of the plot, Tacky and fellow slaves from the Gold Coast rose in St. Mary’s Parish in early April 1760 and seemed most intent on wresting control of the nearby riverine commercial zones and Fort Haldane from which weapons could be taken (the book’s wonderfully detailed maps help us visualize the revolt’s course). Early success came undone in the face of the British militia and of the maroons who had signed a treaty with the British long before and were ready to fulfill their end of the bargain: secure slavery in return for their independence and autonomy. There were, that is, political fissures of great consequence within the African-descended population. Tacky, it appears, was killed by one of the maroon’s bullets, and his revolt collapsed in short order.

But this was by no means the end. There is some indication that Tacky and his followers—nearly half of whom may have been women—rose too early; that they were to have awaited the arrival of the Whitsun holidays some weeks later to coordinate island-wide. British colonial officials and the slaveholders took no chances; they stretched the trials and executions of the captured rebels out over several weeks to gain more information and set terrifying examples of punishments. It didn’t work. In late May another rising occurred in Westmoreland Parish, the heart of the sugar plantocracy, led in this case by Wager (his African name, Apongo), whose trans-Atlantic story Brown reveals in all its complexity and with imaginative guesswork. The Westmoreland rising did not collapse in short order, even when the British navy became involved (thus linking the Jamaican rising with the Seven Years War) or when Wager was captured and gruesomely executed that summer. Rebel bands continued their struggle into the following year, relying on tactics of guerilla warfare, before some semblance of order was restored. Altogether, the Coromantee war would rank as the largest slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere before the Haitian Revolution. It formed a great peak in what Brown terms an “archipelago” of warfare that stretched from the Gold Coast of West Africa through the plantation zones of Jamaica, “at once an extension of the African conflicts that fed the slave trade, a race war among black slaves and white slaveholders, an imperial conquest, and an internal struggle between black people for control of territory and the establishment of a political legacy.”

///

The tsunamis of revolt and revolution in the second half of the eighteenth century were just that, because the seas were integral to the making and meaning of these convulsive events. The rebels in Jamaica and Saint-Domingue had made many journeys across the Atlantic and around the Caribbean. Their perspectives as to what was possible and how to struggle were informed by their fellow seafarers as well as by the masterless souls who manned the vessels of commerce and warfare and brought news—often embellished with their own interpretations—of political developments in London and Paris, along the Gold Coast and Bight of Benin, and in the ports of Barbados, St. Croix, Cuba, Demerara, and Berbice. And, as Niklas Frykman demonstrates in The Bloody Flag, the crews of the warships of Britain, France, and the Netherlands not only carried stories of multiple rebellions; they engaged in rebellion themselves and thereby expanded the dimensions of a revolutionary age.

The naval fleets of the eighteenth century may seem to pale in comparison to our own world of destroyers, aircraft carriers, and nuclear submarines, but the line-of-battle ships were easily the most powerful weapons of war during that time. They were also enormous sites of social hierarchy and labor exploitation. Building on the foundational studies of Marcus Rediker, Frykman reveals the many ways in which naval vessels were historical bridges between the plantation and the factory: in the hundreds of seamen (in some cases nearing a thousand) who labored in twenty-four-hour cycles; in the national, ethnic, and sometimes racial diversity to be found among them; in the brutal regimens and dangers of the work (a “barbaric industry”); in the surveillance to which the crews were subjected and the almost unlimited power of the ships’ officers; in the punishments that were meted out to those who defied the rules (chiefly flogging but also execution); in the form of resistance most common (running away); in the coercive practices (particularly impressment) that could be used to assemble an adequate crew; and in the demands for better and more equitable pay and treatment that could be raised. The term “strike” is of maritime origin. If nothing else, Frykman’s is a significant contribution to Atlantic labor history.

But much more is offered up. The distinction between a strike and a mutiny may be hazy and potentially shifting, as is true for all types of rebellion. Either form of protest could involve a few seamen or a great many, and could occur in a variety of circumstances and times. The 1790s, however, proved to be an especially turbulent era on the seas as it was on the land. There were, according to Frykman, more than 150 single-ship mutinies together with a half dozen fleet mutinies over the course of the decade; in 1797 alone, the British navy experienced mutinies on more than a hundred of the ships in its fleet involving an astonishing 40,000 men, likely the “largest, best organized, and most sustained working-class offensive in eighteenth century Britain.” Some, echoing the political aspirations of the age, proclaimed a “floating republic.”

Frykman’s is very much an account of class formation and political radicalization. And he recognizes them as closely interconnected and mutually reinforcing. On the one hand, he is attentive to the different national experiences to be found as to the makeup of the crews, the means of recruitment, the relationship between maritime and terrestrial (mostly urban) labor, and participation in the warfare of the 1790s. On the other hand, he demonstrates how a shared consciousness, international in its horizons and reflective of the revolutionary struggles in the Atlantic, developed and made itself felt: revolutionary maritime republicanism, Frykman suggests we term it.

By the early 1800s, the authoritarian paternalism that had long shaped relations between officers and seamen had given way to a new arena of struggle organized around class warfare, though one that never fully displaced the political allegiances of warfare between nations. It was “a deepening division of shipboard society into two sharply defined and opposing classes that found its most striking expression in the adoption of the red flag”—the bloody flag—“as a symbol of permanent struggle between them,” accelerated by global conflict and the intense solidarities fostered by maritime labor. Although the mutinous explosions of the 1790s would be quelled by iron fists of suppression, the fortitude of the crews and the coercive practices that they endured led to anti-impressment campaigns in the new United States, which played an important role in articulating the substance of American independence, as well as in Britain. Leaders of the British anti-impressment campaign, such as Granville Sharp, were already deeply involved in the abolition movement, suggesting how the seaborne struggles of the 1790s contributed both to the age of emancipation and the making of national and international working classes. Small wonder that class-conscious sailors would later rear their heads, to great effect, at Kronstadt, Sevastopol, and Kiel, influencing the course of the Russian Revolution and the collapse of the German Imperial state.

How may these works, distinctive in their own ways, together contribute to new perspectives on this revolutionary age? The Coromantee wars of 1760–61 fall outside the customary chronological markers, yet Vincent Brown suggests how we can rethink the placement of those markers as well as the political currents of the Age of Revolution itself. The wars, Brown writes, “represented a watershed in the course of Atlantic history. Regional political maps had been drawn by the wars that opened new territories for cultivation, stimulated the slave trade, and enhanced state power—but the slave rebellions etched another record of historical movement. They channeled people into new solidarities and gave meaning to categories of belonging, partitioned friends and foes from bystanders, and redirected the priorities of governing authorities.” Not only the eventual leaders of the Haitian Revolution but many of the enslaved outcasts of the Coromantee wars ended up in Saint-Domingue, while the wars became part of the political memory and “radical pedagogy” on Jamaican plantations. These undoubtedly fed subsequent conspiracies there as early as 1776, then the Second Maroon War of 1795–96, and ultimately the great Baptist War of 1831–32, involving as many as 60,000 slaves, which led to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Slave warfare, that is, particularly in its large-scale and organized form, may have constructed the Age of Revolution’s great political arc: beginning in the 1760s and ending in the 1860s, when the most powerful slaveholding class in the world was—as in Saint-Domingue—brought down during a massive war in which the enslaved proved to be fighters, liberators, and carriers of the historical sensibilities that –as Julius Scott demonstrates – grew out of the Haitian Revolution.

Yet an arc of revolution constructed by the struggles of the enslaved also reveals the multiple political threads that composed it. “The Coromantee Wars,” Brown argues, “don’t fit neatly into the prevailing narrative of the rise and progress of liberal freedom”; as best as we know, “the Coromantees did not draw upon the Enlightenment ideas that animated British and French revolutionaries, nor did they create an internationally recognized state.” Although “they undoubtedly wanted liberation from the slaveholders,” it was “rarely as liberal subjects—that is, autonomous and self-determined individuals. Instead, they fought for the space to develop their own notions of belonging, status, and fairness beyond the masters’ reach.”

Indeed, in Jamaica as in revolutionary Saint-Domingue and on the mutinous high seas, we may glimpse a confluence of political dispositions, energized and transfigured, that have been inadequately recognized—ethnic-based identities and hierarchies, slave royalism, radical republicanism, peasant consciousness, early forms of pan-Africanism, and working-class internationalism—and that help us sketch new connections between the Age of Revolution’s first (1760–1804) and last phase (1848–67), and between the Age of Revolution and the socialist and communist revolutionary movements of the twentieth century. Much, of course, is left to be done. But the work of Scott, Brown, and Frykman shows some of the new possibilities and potential rewards of viewing the Age of Revolution from below as well as from above.

- Steven Hahn, “Slave Rebellions and Mutinies Shaped the Age of Revolution.” Boston Review. April 23, 2021.

Image is Nèg Mawon/Le Marron Inconnu statue in Port-au-Prince / Image: Amy Nelson

#haiti#haitian revolution#slave rebellion#slave revolt#naval mutiny#age of revolution#european imperialism#slave trade#british slave trade#french slave trade#atlantic revolution#literature survey#academic quote

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 Book-End Review

Here it is! My 2020 Book-End Review. My only consistent New Years tradition.

HARD COPIES

Kingdom of Copper: The second book in the Daevabad Trilogy. Female protagonist, Islamic influenced fantasy world, love stories (gay and straight). Uhg, this was so good. I literally couldn't put it down and was subsequently sleep deprived for a week. I did get a little confused with all the titles and names, but that's what google is for. I haven’t read the third book yet because I haven’t had the time to completely give myself over.

The City It The Middle of The Night- Charlie Jane Anders: Science fiction with female and non-human protagonists. Themes of colonization, the polarization of government, and human nature. It was so hard to get into, but by the end I was completely enthralled and was wishing for more.

Enchantment by Orson Scott Card: Time travel, fairytale (sleeping beauty), Jewish protagonist. It’s simple and enjoyable. I read most of it in the swimming pool :)

All The Birds in The Sky-Charlie Jane Anders: Again, Ander’s books deal with duality, only this time the duality is magic and technology. This book was easy to get into, complex, and brutal. It was so complex, I think I could read it a few more times and get something out of it each subsequent time.

The Lost Gate-Orson Scott Card: The first book in the Mithermages series. All gods are real, coming from an alternate world where their magic and power originates. The gate between worlds has been closed, so the gods' strength has withered. A young boy, from the norse god family, escapes their abusive clutches and discovers his special strength. Meanwhile, on the other world, a young boy observes the palace intrigue and his own powers. The plot is so strong and enjoyable. It’s easy to read, and is well written, which is such a rare quality.

Loving Across Borders: A book on how to navigate multi-cultural relationships. I was hoping this would be interesting and insightful, but I found it to be dry and obvious. The author didn’t include significant personal stories (which is what I find the most interesting and helpful). Essentially, a summary of the book is: Communicate with people, each situation is different, and set boundaries… Duh.

2020 Audio Books

The Polygamist's Daughter - Anna LeBaron: A memoir told by the daughter of a cult leader. It is told from her adult perspective, remembering her childhood which is full of abuse and neglect, and then working through her trauma with a therapist at the end. It was an interesting enough story, but could probably have benefited from some editing. I honestly wouldn’t recommend it.

The Heart Goes Last: Freaking love this book. A dystopian future where the poor and disenfranchised can sign up to live in a compound with shifts in a utopian world and then in a prison/work compound. In this setting there is love, romance, and DRAMA. I listened to it twice.

Little Fires Everywhere: Socioeconomic differences, race, art, women’s rights, mother daughter relationships, infertility, motherhood. The book is better than the show.

An Easy Death- Charlaine Harris: Book one of the Gunnie Rose series. A little western/gun slinger genre, a little magic, a little alternative history. A hot Russian magician and a female gunslinger protagonist. It’s not a great book, but I bought the second one, so I guess it was good enough.

A Longer Fall- Charlaine Harris: The second Gunnie Rose book. I actually liked this one more than the first book. The characters seemed more flushed out and the story was more complex. The ending left me wanting more, and I’m looking forward to the third book in Feb 2021. Widdershins-Charles Delint: The follow up to The Onion Girl, the background story is a war between native spirits and fairy, while the protagonist Jilly faces the abuse she endured as a child and the guilt she carries for leaving her younger sister in the abusive home in order to survive herself.

His Majesty's Dragon: Book 1 of Temeraire. Alternative history of Napoleonic wars with DRAGONS. A sea captain unexpectedly bonds with a baby dragon, and has to change his whole life to accommodate it. I really enjoyed that this book has almost no romance. It’s just straight up about the relationship between a man and his dragon.

Throne of Jade: Book 2 of Temeraire. The Captain and the Dragon/Temeraire travel on a mission to China, where dragons are treated with respect and care. The dragon/Temeraire is becoming more mature and the disparity between West and East is highlighted, which causes some tension between the captain and the dragon, as well as between the reader and the book (at least for me).

Black Powder War: Book 3 of Temeraire. I gave up on this series with this book. The main human character’s inability to stand up to society and the government to demand that they treat his his dragon (who’s basically a soulmate) as a whole and independent being was too frustrating.

Moonheart -Charles Delint: This is the third time I tried to read this book, and I didn’t finish it. I just can not get into it. I love Charles Delint, but this book isn’t for me.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone: I love Harry Potter, and with the quarantine, listening to the whole series was the best mental comfort food. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets:Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Midnight Sun: LOL, sorry not sorry. This is trash and I love trash. However, Edward is super self-pitying and creepy. I knew that from the original series, but reading it from his perspective made that feel even more clear. I spent a lot of time making rude comments about Edward under my breath. I’d honestly listen to or read the rest of the Twilight series again, but I’d skip this one.

The Witch's Daughter: Female protagonist, with an immortal witch, and a young female apprentice. I had to force my way through it until the last quarter, and then I was really engrossed. The ending was nicely wrapped up, and I don't feel the need to read the sequel. Interestingly, I really disliked the narrator's voice, but it was the only audiobook I’ve listened to that Kal didn't mind. (Because he hates the sound of audio book I usually use my headphones).

Too Much And Never Enough: Donald Trump’s niece exposes their shared, terrible, abusive, and sad family history. It sheds some light on who Donald Trump is as a person. The psychological background doesn’t make his actions any better, but it helped me to understand how he could be the way he is. Honestly, this book was good for my mental health.

A Deadly Education-Naomi Novik: I LOVED THIS BOOK. In a world where the magicaly gifted are hunted by terrible monsters, magical children go to a school where they have to fight to live. It deals with how inequality in socioeconomic standing impacts students and their ability to succeed… with magic and romance.

The Betrayals: This book started a little slow. The characters are all flawed and make terrible mistakes because they are too proud. There is romance, magic, and redemption; I enjoyed the ending, but there were so many emotionally tense moments I wouldn’t say I enjoyed the book as a whole.

Caraval: Sisters escape their abusive father to become embroiled in a magical game where what is real and what is fake is unclear. Magic, romance, sisterly love, and mystery. The writing isn’t perfect, but I enjoyed the ride of this book.

Currently Reading:

Hard Copy: The Gate Thief, Book 2 of the Mithermage Series.

Audiobook: Legendary, Book 2 of the Caraval Series.

Poetry: Salt

I read/listened to 29 books this year. I'm tempted to try to finish a 30th before my 30th birthday on Monday. We'll see if I make it :)

#book review#2020 bookend review#2020#2020 books#2020 book review#end of year book review#caraval#harry potter#the betrayals#a deadly education#Too much and never enough#the witches daughter#midnight sun#temeraire#Gunny rose#the mithermage#little fires everywhere#the city in the middle of the night#all the birds in the sky#Kingdom of copper

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best Documentary Short Film Nominees for the 93rd Academy Awards (2021, listed in order of appearance in the shorts package)

NOTE: For viewers in the United States (continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawai’i) who would like to watch the Oscar-nominated short film packages, click here. For virtual cinemas, you can purchase the packages individually or all three at once. You can find info about reopened theaters that are playing the packages in that link. Because moviegoing carries risks at this time, please remember to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by your local, regional, and national health guidelines.

A Love Song for Latasha (2019)

On March 16, 1991, Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old African-American girl, was murdered by Soon Ja Du at Du’s convenience store in Los Angeles. The murder, which occurred almost two weeks after Rodney King’s beating at the hands of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), contributed to the start of the 1992 LA riots one year later. Directed by Sophia Nahli Allison, A Love Song for Latasha is an avant grade film that intercuts statements by Latasha’s friends and family about the young girl they cared deeply for. Alongside reenacted scenes of childhood, of black girls frolicking on the Californian coastline and the streets of Los Angeles, the film serves as an intimate eulogy for Latasha – one delivered as memories about her become less immediate.

Whatever justified rage the Los Angeles rioters might have felt in 1992 is not the dominant force in Allison’s film. A Love Song for Latasha is foremost a cinematic lament rather than a political polemic. With the reenacted scenes edited and appearing as if it resembling a home movie, this piece appears like a visualization of the memories that the interviewees are recalling. When Latasha was murdered, she ceased to be just a daughter or a friend. A Love Song for Latasha, thirty years on, seeks to reclaim those distinctions for those who knew her best – something, given the significance of Latasha’s murder in history, that may never happen.

My rating: 6.5/10

Do Not Split (2020, Norway)

From Norwegian documentarian-journalist Anders Hammer comes Do Not Split, a street-level glimpse into the protests against the 2019 Extradition Law Amendment Bill (ELAB) that inspired the passage of the 2020 Hong Kong national security law. The events depicted in Hammer’s film include the Hong Kong police’s sieges of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and Hong Kong Polytechnic University, in addition to small-scale clashes between protesters and police, as well as mainland Chinese instigating confrontations. Hammer’s footage is harrowing material, a collection of violent imagery with few moments of individual revelation or introspection outside of the presence of Michigan-born activist Joey Siu. Do Not Split decides not to attempt a dialectic of why the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Hong Kong Legislative Council (LegCo) are pursuing these changes and are brutalizing the protesters, depriving this film of the context that less knowledgeable viewers might need. For those who have been keeping at least superficially aware of events in Hong Kong, there is never any question on which side Hammer is on – despite Hammer’s journalistic background, this is not a piece of objective journalism.

Yet this is not agitprop due to the politics left mostly unexplained, and none of Do Not Split’s flaws take away from the rawness of the protesters’ desperation and the cynicism of the police and government officials enacting the crackdown. Despite the repetitive nature of the footage by the time it reaches the final stages of its thirty-five-minute runtime, Do Not Split contains excellent, crisp hand-held footage that makes immediate sense of the space and time of the depicted violence.

My rating: 8/10

Hunger Ward (2020)

For Pluto TV (some cord-cutting television service I was not familiar with until I started writing this) and MTV Films and directed by Skye Fitzgerald (2018 Oscar-nominated short film Lifeboat), Hunger Ward follows doctor Aida Al-sadeeq and nurse Mekkia Mahdi as they treat malnourished children in the midst of ongoing the Yemeni famine. The famine, directly related to the civil war that began in late 2014, has seen almost a hundred thousand children die in what UNICEF describes as, “the largest humanitarian crisis in the world.” Fitzgerald film works best when focusing on Al-sadeeq and Mahdi, as they describe the heartbreak conditions of the hunger ward and their experiences since the famine began. However, much of Hunger Ward’s footage is too in-your-face with footage of the mothers’ grieving and the last moments of several children. It appears almost as if gawking at the desperation and death that occurs every day in this hospital.

This is not to say that there is no revelation in the image of a child with their eyes glazed in lifelessness or the unearthly wails of a mother overtaken by grief. Fitzgerald edits and shoots their film in a way that makes this process – a child in their last moments of care, a declaration of death, a shot of the child’s corpse, a cut to the mother inside or arriving to the deathbed, and the echoing despair – occur tediously in their movie. Hunger Ward never breaks from this tedious formula. The film is redeemed only by withholding its slings and arrows until some text prior to the end credits, correctly assigning responsibility with Western nations that have enabled and abetted the violence in Yemen.

My rating: 6/10

Colette (2020)

Colette Marin-Catherine is in her twilight years and, upon first appearances, one might not predict the incredible life story that she has to tell. She was a French Resistance member, and French Resistance narratives tend to be sidelined in favor of those depicting Allied soldiers liberating France instead. But Anthony Giacchino’s (the brother of composer Michael Giacchino) film, distributed by British newspaper The Guardian and made for an extra feature of the virtual reality (VR) video game Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond, decides to linger on the memories of Colette’s murdered brother, who died at Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp in Germany, instead. At the urging and with the assistance of the young historian Lucie Fouble, who is interested in telling Colette’s story (although technically this is not Colette’s story), Colette travels to Germany to visit the site of Mittelbau-Dora so that Colette can… spill out her feelings?

It is self-evident that Colette does not see the academic or personal value of such a trip, but the irascible subject of this short film will nevertheless humor Fouble – her intentions genuine, her approach questionable. Colette, who cannot forget the loss of brother but has not been dwelling on his death, is emotionally vulnerable throughout the trip to Germany, and the audience learns little about Colette, German atrocities, or her brother. Even in these moments, she remains a compelling figure on-screen, but this movie is a disservice to its eponymous subject – one who deserves more credit as a member of the French Resistance, as someone not defined by the worst thing that had ever happened to her.

My rating: 6/10

A Concerto Is a Conversation (2020)

Distributed by The New York Times and executive produced by Ava DuVernay, Ben Proudfoot and Kris Bower direct a deeply personal documentary short film to bookend this slate of five. A Concerto Is a Conversation contains a conversation between Kris Bowers (composer on 2018’s Green Book and 2021’s The United States vs. Billie Holiday) and his grandfather, Horace Bowers Sr., before the premiere of Bower’s concerto at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. What follows is a disjointed film with sketches of Jim Crow-era America from Horace’s past to the anxiety-laden self-questioning of Kris’ present. Kris, as a black man, is questioning his place in the classical music world – which has, justifiably in some ways, been seen as staid and white. If A Concerto Is Not a Conversation can bridge the differences between Horace and Kris’ stories, it barely does so thank to the scattershot editing.

Yet Kris and Horace’s conversation is wholesome, admiring, loving. This is Kris’ way to show his appreciation for his grandfather and the struggles that he endured for most of his life. The out-of-focus background makes A Concerto Is Not a Conversation seem almost like a dream, a meeting that almost should not be happening. And in honoring Kris’ profession and the piece that is set to debut, the film is divided into noticeable thirds – just like a concerto’s three movements. A Concerto Is Not a Conversation might not make for the most cohesive viewing, but it is a celebration of a profound bond, tied together by forces that defy even the most eloquent words: music and love.

My rating: 6.5/10

^ All ratings based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

From previous years: 88th Academy Awards (2016), 89th (2017), 90th (2018), 91st (2019) and 92nd (2020).

#A Love Song for Latasha#Do Not Split#Hunger Ward#Colette#A Concerto Is a Conversation#Sophia Nahli Allison#Anders Hammer#Skye Fitzgerald#Michael Shueuerman#Anthony Giacchino#Ben Proudfoot#Kris Bowers#Latasha Harlins#Hong Kong#Yemen#Ava DuVernay#93rd Academy Awards#Oscars#31 Days of Oscar#My Movie Odyssey

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Few Thoughts About the Current Run

I feel like I ought to say a few things about my feelings on Zdarsky’s run, as of right now (August 2020, pre-Annual-- that may be important). I haven’t said much about this run, and I should admit that I actually stopped reading it for a while. At a certain point, I realized I was dreading the release of each preview, and took that as a sign that maybe I should take a break and just re-read some back issues instead. This is, above all, supposed to be fun; I never, ever want reading DD to feel like a chore.

That said, I am now caught up and feel ready to begin untangling exactly why this run is so distasteful to me. I’ve been fortunate to have other DD fans to chat with about this, which has helped me to pinpoint what my problems are... because on paper, this run seems like something I’d enjoy. Matt accidentally kills a guy; that’s always fun. Marco Checchetto is great. The story explores Daredevil’s relationship with the citizens of Hell’s Kitchen, which I love. Foggy helps Matt with an action-y Daredevil thing; that’s awesome. There are some very cool fights. Elektra is in it. Stilt-Man is (briefly) in it. It has all the trappings of an interesting narrative. But there is a giant hole in the middle of this run, and that hole is Matt Murdock-shaped and impossible to ignore.

I read Daredevil comics for a lot of things (anyone who’s been following me for the past few years might think I read Daredevil comics for Mike Murdock, and you may have a point there) but first and foremost, I read them for Matt. There is a lot that makes a good DD story great-- historically, the comic has featured great supporting casts, and that’s another problem with this run that I’ll get back to in a minute-- but Matt is always the anchor. One of the greatest strengths in Daredevil comes from the fact that the protagonist is such a compelling character. You are interested in what he’s doing. You want to follow his story. You enjoy being inside his head. I’m not saying that you can’t write a good Matt-free Daredevil story-- you definitely can. But if Matt is present and written poorly, the whole story will collapse around him, and that’s been my experience with Zdarsky’s run. Part of the reason I’ve taken so long to write this post is because I’ve been trying to figure out if my complaint comes from my own personal taste-- which is not a basis on which I can critique this comic-- or whether the problem is inherent in the work itself. Having discussed it with other people, I feel comfortable saying that I think the problem is in the writing.

Zdarsky’s Matt feels profoundly unfamiliar to me, and that in itself isn’t necessarily a problem, but I don’t find this new version of my favorite superhero interesting. I actually find him a little repellant. If this run had been my introduction to Daredevil, I would’ve said “Nope” and read something else. Matt is a character with depth. He is intensely multifaceted. His relationship to superheroing is complicated, his views on justice and morality are rich and often contradictory. Zdarsky somehow missed all of that and has crafted a one-dimensional character with a blatantly black-and-white sense of morality. Matt’s reaction to accidentally killing someone seems to be to decide that all superheroes are bad-- something I complained about at the beginning of the run and which, unfortunately, only grew more annoying as the story progressed. Zdarsky’s Matt is painfully self-righteous, to a degree that makes him extremely unlikeable (at least to me). And yes, Matt has been written as unlikeable before. I actually love when Matt behaves badly; I find that fascinating from a narrative perspective. But I’ve realized that the key reason that has been effective in the past is because the story has never condoned that behavior. When Matt was emotionally abusive toward Heather Glenn, Frank Miller went out of his way to show us-- via the side characters, via blatant expressions of Heather’s pain-- that Matt was in the wrong. When Matt was a jerk in Bendis’ and Brubaker’s runs, when he drove his friends away, when he acted irrationally and harmfully, the narrative commented on that jerkiness and irrationality.

But Zdarsky does not do that in his run. He presents Matt’s irrational and jerkish behavior without comment or nuance, as if it’s a perfectly normal, reasonable way for Matt to act under the circumstances, and I have been surprised to realize how distasteful I find that, and how bad it makes Matt look. There’s a difference between having a character who is comfortably flawed-- whose behavior you’re supposed to occasionally question-- and a character who is just unpleasant and unlikeable, seemingly by accident. In the most recent issue (#21), Matt has an extremely upsetting interaction with Spider-Man, one of his oldest friends, and Matt is positioned as heroic for behaving this way, and it made me feel a little ill, because there’s no textual examination or questioning of this behavior. It’s just Matt, pushing people away, being Angsty(TM) and Gritty(TM) and lone wolf-y just because, in a way that is grating and unpleasant and completely lacks nuance.

The other major element of Zdarsky’s characterization of Matt is religion. I’ve mentioned before (as have other DD fans before me) that Matt is not generally written as religious, and it’s a strange phenomenon that this characterization has appeared in multiple adaptations (the movie and the Netflix show) while having very little actual presence in the source material. But it was a key theme in the Netflix show, and while hopefully that influence will disappear from the comics as more time passes, we are still in a honeymoon phase wherein MCU elements are still popping up in the 616 universe. It’s clear that Zdarsky really liked the show, and Soule as well; I’m certainly not letting Soule off the hook here, because the idea of Matt being devoutly Christian showed up his run first. But there, you could get away from it if it wasn’t your thing (which, for me, it’s not). Soule had whole story arcs that didn’t mention it. But Zdarsky has made it 75% of Matt’s personality. When he isn’t fighting or sleeping with someone in this run, Matt is angsting about God.

I hesitate to complain about this because it’s Zdarsky’s right as a DD writer to change the protagonist however he likes. It’s frustrating, yes, but not actually a sign of bad writing per se. Plus, not everyone is me. Many people-- probably including many people who were fans of the Netflix show and are entering the comics via that connection (which seems to be the target audience for this run)-- may be religious and may connect to MCU/Zdarsky Matt in that way. And that’s wonderful. I want to be very clear: it’s not the religiousness itself that I’m complaining about. My complaint is this: if you’re going to drastically alter a character, you need to back it up. You need to dig into it, make that new personality element feel powerful and real, and integrate it into the character’s pre-existing personality. And if you’re going to base the entirety of that character’s emotional journey on that new trait, you need to work to make sure it’s accessible to your readership. I, as a non-religious person, have no sense of why Matt is so upset about God. I have no frame of reference for his pain, either from my own experiences or from previous Daredevil continuity, and Zdarsky does nothing to develop or explore the basis of Matt’s faith, and so it all just falls flat. I feel alienated by this run. I see an angsty, self-righteous, prickly jerk ranting about needing to do God’s will, and then I put the issue down and read some She-Hulk instead. If Zdarsky (or Soule-- again, he could have done this too) had made an effort to actually explore and explain Matt’s feelings about his religion, rather than lazily shoving that characterization in there and assuming readers will just accept it, it wouldn’t bother me nearly as much as it has.

Also, I feel I have to mention; this is a fantasy universe. Matt went to Hell and yelled at Mephisto in Nocenti’s run, and it was awesome. Maybe this is just me, but if you’re going to bring in religion, at least have some fun with it! Bookend Nocenti’s run: Matt goes to Heaven, runs into God, and she gives him some free therapy and a souvenir t-shirt (or, I don’t know, something). To give Zdarsky credit, he did at least hint at that sort of thing in Matt’s conversation with Reed Richards in #9.

I'm going to cut this post short, because I really don’t enjoy writing negative reviews. I’d much rather post about things I love, and over the next few weeks I do plan to highlight aspects of this run that I’ve enjoyed. But I’ll end by saying that the weaknesses in Matt’s characterization could have been mitigated by a great supporting cast. Having prominent secondary protagonists would have provided outside perspectives on Matt’s behavior and given the reader other characters to root for when he got too out-of-hand. They would have drawn out the human elements in Matt’s character and helped give him that nuance he so desperately needs. But this run, just like Soule’s before it, is woefully underpopulated. Foggy’s presence is extremely weak and his appearances far too infrequent. Apart from brief cameos in MacKay’s Man Without Fear mini, Kirsten McDuffie and Sam Chung have both vanished, and I’m worried that Kirsten might have joined Milla Donovan in the limbo of still-living-but-permanently-benched ex-love interests. The women in this run are all either villains or people for Matt to sleep with (I was pumped about Elektra’s return and the idea of her training Matt, but her characterization was disappointing (I may write a separate post about this), and Mindy Libris could have been really compelling as a moral person trying to survive life in a crime family, but instead she was just a one-note, underdeveloped victim for Matt to lust after). To Zdarsky’s credit, he has clearly been trying to give the Kingpin a humanizing story arc, but even that I haven’t found compelling enough to want to keep reading (though that could just be me). Cole North was intriguing at first, but he ended up feeling more like a concept than an actual person. And none of these characters engage with Matt on a human, emotional level, which is what a good supporting cast needs to do. I commented early-on that this run felt like all flash and no bang (Is that a term? It is now.) and I think I still stand by that-- it’s all bombastic plot concepts and big ideas without any of the actual development or nuance necessary to make them work. There is nothing in this run that has pulled me in and held my interest; in the absence of a Matt I can connect to, I need something, and so far I haven’t found it.

I could go on, but I think I’ve made my point. This run was nominated for an Eisner for best ongoing series, so apparently someone likes it, but it has become clear that-- so far, anyway-- it’s just not right for me.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Track review-- A deeper look at: Lyle Mays “Eberhard” (Self produced, 2021)

Lyle Mays (piano, keyboards, synthesizers), Bob Sheppard (sax and woodwinds), Steve Rodby (acoustic bass), Jimmy Johnson (electric bass), Alex Acuña (drums and percussion), Jimmy Branly (drums and percussion), Wade Culbreath (vibraphone and marimba), Bill Frisell (guitar), Mitchel Forman (Hammond B3 organ, Wurlitzer electric piano), Aubrey Johnson (vocals), Rosana Eckert (vocals), Gary Eckert (vocals), Timothy Loo (cello), Erika Duke-Kirkpatrick (cello), Eric Byers (cello) and Armen Ksajikian (cello)

When pianist, synthesist and composer Lyle Mays passed on February 10, 2020 from a lengthy battle with an undisclosed illness, to say it was shocking to all those who enjoyed both his work with the Pat Metheny Group (1978-2005, with officially undocumented Japanese and European tours during 2009-10) and his small catalog as a bandleader was an understatement. The word genius is overused in the music and entertainment industry but Mays truly was a genius in every sense of the word. Not only was he a fabulous musician and composer, but he was multi-talented. Among his many interests outside music: architecture, he had designed his own Los Angeles house as well as one for his sister in Wisconsin; he was a soccer enthusiast that while he was with the PMG actually taught and coached a local team a distinct Brazilian style of play, he was a computer programmer, and a billiards player who played on the professional circuit. Above all, Mays’ attention to structure, detail and compositional drama was a hallmark of his own work, and his brilliant harmonic mind always contributed effervescent improvisational ideas. While he possessed chops in spades, the keyboardist always used them in a meaningful way. As a synthesist Mays was the most significant musician after Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul as a player in the “jazz” field.

Eberhard, composed in 2009 for the Zeltsman Marimba Festival, is a tribute to one of Mays’ greatest influences: the bassist Eberhard Weber. The 13 minute track, which is being released world wide as a single on CD, LP and streaming formats is in many ways a perfect bookend to Lyle Mays (Warner Bros/Metheny Group Productions, 1986) the titular debut record that, while sounding quite unique from anything in the so called “fusion” field was critically panned at the time. In the decades since, the album has gained a cult following as a bonafide classic. The remainder of Mays’ catalog (including a 1993 quartet concert released 22 years later The Ludwigsburg Concert) has broad reach that in its totality represented restless exploration and traversed multiple trails simultaneously.

After the PMG’s The Way Up however, Mays had reservations about where the music industry was going and retired from the music industry instead working a regular position as a software engineer. He also couldn’t deal with the rigors of touring and after the aforementioned PMG Songbook tour of Europe and Japan during 2009-10, Mays had had enough. Though there were rumblings of Metheny and Mays writing for a new Group record a few years later, ultimately the plans were scrapped and the keyboardist made relatively few live appearances, instead focusing on a few teaching appearances co lead with collaborator and sound designer Bob Rice (most known as a Synclavier operator for Frank Zappa) and a widely viewed TED Talks appearance. Mays had also become an endorsee for synthesizer companies Arturia and Trillian Spectrasonics.

Sometime in 2019 Mays’ health began to worsen and decided he needed to record Eberhard so it is not a traditional posthumous release because he was involved in every aspect of playing, composing, recording, orchestrating and producing. As an associate producer, long time PMG band mate, acoustic bassist on the track and best friend Steve Rodby says in the liners, Eberhard was not to be the last work of Lyle Mays and he had plans for more. After Mays’ death, on the Pat Metheny website, the guitarist posted some words about his long time musical compatriot and indicated that he and Mays had been talking about a wacky idea of which he could not reveal the details, but that it was something related to a sequel of their classic As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (ECM, 1981). Eberhard is significant for being the largest ensemble Mays ever led, at 16 members bringing back Alex Acuna and Bill Frisell from the first album, Steve Rodby on acousic bass (who appeared on 1988’s Street Dreams) and featuring mallet player Wade Culbreath, electric bassist Jimmy Johnson, vocalists Rosanna and Gary Eckhart as well as Mays’ niece the rising Aubrey Johnson. A string quartet, Bob Sheppard on reeds, Mitchel Forman on Hammond B-3 organ and Wurlitzer electric piano, and second drummer Jimmy Branly round out the group besides Mays’ piano and keyboards.

Mays’ connection to Weber’s music goes back further than the 2009 composition, which has roots decades before in 1983. While Mays appeared on the bassist’s wonderful Later That Evening (ECM, 1982) Weber had appeared on Pat Metheny’s Watercolors (ECM, 1977) forming the backbone along with drummer Danny Gottlieb of what could be considered a Pat Metheny Group prototype, and the tracks Mays appeared, are really a prequel to Pat Metheny Group (ECM, 1978). Weber remained a profound influence on the keyboardist’s composing, and when the PMG’s swan song The Way Up (Nonesuch/Metheny Group Productions, 2005) was released, the melancholy bass melody of “Part 2” was a direct reference to Weber.

The piece begins with an marimba ostinato from Culbreath, a two note motif with a touching chord progression. Mays states a few of the melodic ideas with his signature piano reverberating in the atmosphere with trademark subtle layers of keyboards and percussion from Acuna. It’s important to note the striking similarities in style between Mays and Weber keyboardist Rainer Bruninghaus. Mays and Bruninghaus, it must be said conjecturally, seem to have explored parallel paths in their harmonic styles and solo wise. Jimmy Johnson’s fretless bass then takes center stage for a bass melody redolent of Weber, before things really begin to percolate with minimalist motifs that are quite influenced by Indonesian Gamelan music (shades of the title track to Imaginary Day) and Steve Reich. Flutes state a motif taken directly from Weber’s “T. On A White Horse” on The Following Morning (ECM, 1974) and the first bits of wordless vocals appear with the motif, the percussive vocal effects that appear from the far left and right parts of the sound stage are reminiscent of the synth effects Mays used on “Northern Lights”, the first movement of the “Alaskan Suite” from Lyle Mays. There are also musique concrete sonic collages that frame the eerie dream like sequences much like the first two parts of Street Dreams (Warner Bros./Metheny Group Productions, 1988).

Mays takes a solo that builds in intensity and arc before the main musical kernel melodically is revealed behind Acuna’s drums and the wordless vocals from the Eckhart’s and Johnson. During a further development of this section, Mays and Johnson engage in an awe inspiring duo with Johnson’s vocals in unison with his keyboards. It is here and only here, for a couple of bars does Mays signature ocarina like synth lead appear, more as a texture placed in the mix alongside other sounds. Bob Sheppard, ace LA studio player and longtime associate of the keyboardist takes a searing tenor sax solo buoyed by Rodby’s inimitable bass and surging intensity from the rest of the ensemble. An intriguing aspect of Mays’ comping behind Sheppard revolves around a device he loved to use, where rhythmically his lines “pulse” much like the way Stravinsky has rhythmic pulsing in pieces like The Rite Of Spring and The Firebird. Another fine example of this style of comping would be the way Mays comps behind Pat Metheny’s guitar synthesizer solo on “As It Is” from Speaking of Now (Warner Bros. Metheny Group Productions, 2002) though there are numerous other examples of Mays doing this in other tracks throughout his discography. Once things reach the point of no return in terms of build, the piece ends as quietly as it began. The marimba ostinato returns behind the subtle synth underpinning and the piece achieves an utterly satisfying resolution. It is remarkable that in 13 minutes the piece travels as much territory as it does, it feels as if the listener has been on a much longer journey.

Sound:

Recorded, mixed and mastered by Rich Breen, Eberhard was recorded during the latter parts of 2019 up through January 2020. The familiar hand of Steve Rodby served alongside Bob Rice as associate producers and sonically the piece is full and dynamic covering the entire sound stage. Production wise, the album falls between Lyle Mays and Street Dreams. As with those albums, Frisell is a textural voice in the mix as opposed to a lead voice, and he seamlessly blends into the soundscape in a way the listener may not notice. Mays’ piano is at once gleaming but also relatively dark in timbre but is so resonant across the sound stage with reverb. Drums, and bass all sound accurate and have appropriate punch, and new details in the sub mix reveal themselves over time upon multiple listening.

Concluding Thoughts:

In a cultural era where the light music brings is needed more than ever Eberhard is simply a gift. Mays’ entire catalog is worth investigation, but there is something about the piece that places it near the top, it is perhaps barring none, the finest compositional achievement of his entire career. On its own terms it is wondrous, for those who have missed Mays’ contributions to the Metheny Group this will fill a much needed hole, but in terms of the keyboardist/composers’ oeuvre as a leader this quite simply is the piece de resistance and easily fits as the bookend to the self titled opus and a perfect capstone to a remarkable career and life.

Music: 10/10

Sound: 9.5/10

Equipment used for review:

HP Pavilion X360 laptop (for digital promo streaming)

Marantz NR1200 stereo receiver (used as preamp)

Marantz MM 7025 power amplifier with AKM 4000 series dual DAC’s

Focal Chora 826 speakers

Beyerdynamic DT 770 Pro headphones

Audioquest Forest and Golden Gate cables

Canare 4S11 speaker cable

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Lowdown: Once again, Taylor Swift was lying when she told us there was “not a lot going on at the moment.” Once again, she’s dropped a carefully curated collection of songs unraveling both her extremely public exterior and deeply personal interior life. And once again, it’s an album that acts as a remarkable exercise in lyricism. It’s not just a worthy follow-up to July’s folklore; it’s a mirror, a companion, and a bookend. Taylor had a few more things to say. The fable wasn’t finished yet.

Like folklore, evermore was announced hours before release, framed as a “sister” project to the summer album that gave us the latest reinvention of Taylor Swift and successfully cemented her, even in many previously unconvinced eyes, as one of the strongest songwriters working today. evermore picks up where folklore left off, and it would’ve been easy to believe that all the songs across both projects were written at the same time had Miss Swift not logged onto YouTube and replied to a comment, sharing that she’d finished one track, “happiness”, just last week. She meant it when she said she just couldn’t stop writing songs.

evermore doesn’t necessarily add anything new to the conversation its older sister started, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that if this collection had been released first, it would have been received nearly as positively as its predecessor. There’s a chance we all adjusted to this era of woodsy cottages, lakeside fires, and misty forests so naturally that returning to it was as easy as slipping into a favorite sweater

The Good: evermore allows Taylor to continue doing what she does best, which is share stories, both real and imagined. This record further establishes her identity as a modern poet, and the allusions to writers of old are tucked throughout. On “happiness”, Taylor conjures imagery of the gothic and macabre: “Past the blood and bruise/ Past the curses and cries/ Beyond the terror in the nightfall/ Haunted by the look in my eyes.” Later in the same track, she echoes Daisy Buchanan’s iconic words in The Great Gatsby when she bitterly sings, “I hope she’ll be your beautiful fool.” Taylor’s narrative storytelling is on full display with “tolerate it”, a quietly devastating domestic portrait of a relationship that has dissolved into ruins. (F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote The Great Gatsby, but could he have written the bridge of this song? Unlikely!)

The turns of phrase are relentless and piercing across the 15 tracks, almost difficult to keep up with, passing in a flash and registering like aftershocks moments later. “ivy” wraps the listener in an embrace tinged with the melancholy associated with bluegrass; “‘tis the damn season” couldn’t have arrived at a better time, unpacking the feelings of returning to a hometown inextricably tied to memories of a youthful romance.

The glimmering “gold rush”, co-produced with trusted collaborator Jack Antonoff, is a bright standout. It’s immaculately produced and slight, barely three minutes long, flickering to life and whisking the listener into a starlit night without wasting a moment. The light pulse and breathy, layered vocals pair with playful verses. Though not as unstructured and unbound as some later tracks (with the titular and expansive “evermore” coming to mind in particular), “gold rush” feels almost conversational, a rambling confession of love in a doorway. There’s something about Taylor Swift’s music that makes such earnest moments believable.