#220 bce

Photo

Barberini Faun, 220 BCE

Glyptothek, Munich

#barberini faun#glyptothek museum#glyptothek#munich#germany#europe#travel#travelling#museum#gallery#art#art history#220 bce#bce#my photos

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ceramic dancing figures from China. 206 BCE-220 CE, now housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art

More: https://thetravelbible.com/museum-of-artifacts/

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Yin and Yang

It's always occured to me that Miraculous Ladybug is based on Yin and Yang philosophy but at the same time it's really not.

Both the symbol of the black cat and the ladybug acquired their meanings around the same time in medieval Europe. Superstitions about black cats originated during the period of witch hunts, which began in the early 13th century in Europe.The name "ladybug" comes from medieval European farmers who would pray to the Virgin Mary for good harvests. Ladybugs feed on pests that destroy crops, so their appearance was seen as a sign that their prayers had been answered.

However, Yin and Yang philosophy came from ancient China and this concept has its own symbols.

There're no records about this concept being used by ancient Chinese alchemists. However, the concepts of essences is a part of Neidan branch of alchemy, whereas experimenting with minerals and something material is a part of Waidan alchemy. So, miraculouses might be the result of combination of two of these branches.

First notice of Waidan alchemy was made during Han Dynasty (206 BCE���220 CE) and gradually declined until the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Neidan was arguably first mentioned in in Jin dynasty (266-420). Also Ying and Yan philosophy was first mention in the 16 century. So, creation of the miraculouses should have taken place between the 16 century and the 17 century.

Dragon as the symbol of Yang, the Sun and it is connected with masculine energy, so this is considered to be a miraculous for males.

Tiger as the symbol of Yin, the Moon, on the contrary, is considered to be a miraculous for females.

Both of them are in the beginning of their way for Balance. Marinette will go through Red Dragon phase before becoming Golden Dragon. While Adrien will go through Black Tiger phase before becoming Golden Tiger.

But I.. couldn't come up with their names

#Dragon and Tiger AU#art#artists on tumblr#artwork#my art#digital art#mlb fanart#mlb#mlb fandom#mlb au#miraculous#miraculous lb#miraculous fanart#miraculous ladybug#miraculous au#adrien agreste#mlb adrien#mlb marinette#marinette dupain cheng#Au info

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In historical context though-"

This book has potatoes and chilis in supply and demand when these were not traded until the late 15th century... and not used for cuisine and a foods crop cultivator in China well into the 17th and 18th century almost 200 years later. Folding fans that are seen abundantly were not popularized until the 13th century. Taoism was at its largest during the Warring States period of 450 BCE–c. 300 BCE with the epigram of Tao Te Ching. Confucianism became the abundant practice as of 206 BCE to 220 BCE with the authoring of The Analects. It uses fabricated province names for real world Chinese provinces that are relegated to a simple five, when there are of 22 (claimed) and have been the most stable to survive since the Yuan dynasty 1271-1368. Idioms used vary through the centuries and are still a staple of modern day vernacular. The version of futou Jin Guangyao alone wears was a wushamao (乌纱帽), used in the Ming dynasty 1368-1398. Futou was made a part of ministerial and court attire during the reign of Emperor Wu 560 BCE.

The author has said it has no standing Imperial Dynasty it takes place in and has borrowed aesthetics from the Han, Wei-Jin, Song, Tang, Ming and even Qing. All of which had seen several turns of dynasty from Han to Mongol to Han divine rulings. So no, there is no historical context to take in regard when it comes to Madam Yu's overt abuse, to Jiang Cheng's abuse, the clan's classisms and hypocrisy.

It was written in an alternate fantasy of China without this context of real world history and through the lens of modernity of its author. Do not use a history that does not pertain to a novel that is not has not and was never called historical.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unknown Chinese Artist; Rhinoceros/Mythical Beast, c. 206 BCE - 220 CE

Earthenware

608 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fooduary Day 10: Dragon's Beard Candy

Happy Lunar New Year!!! This one probably doesn’t seem very obvious but a white-candy version would be terribly unlucky!! (And I need all the luck I can get). So I tried to make the lantern slightly reminiscent of the treat while the character is styled in Han Dynasty fashion. According to the legend-history of dragon’s beard candy it was invented in the Han Dynasty (202 BCE 220 CE) which makes it our oldest dessert yet! And yeah, I went off script for this one. Day 10 was supposed to be Cinnamon rolls but I’m moving some stuff around because I so rarely get the chance to post something to celebrate.

I am the artist! Do not post without permission & credit! Thank you! Come visit me over on: instagram, tiktok or check out my coloring book available now \ („• ֊ •„) /

https://linktr.ee/ellen.artistic

#dragon's beard candy#han dynasty clothing#fooduary#art challenge#historical fashion#ellenart#lnart#character design#digital illustration#historically inspired#fooduary2024#dragons beard#hanfu#happy CNY#happy lunar new year#year of the dragon#chinese new year

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

My revamp of the sculpture, Sleeping Satyr / Barberini Faun, by Unknown Artist, circa 220 BCE

#astrazero#gaygoth#gaywitch#gayartist#darkart#gayart#queerartist#vampire#astra zero#darkartists#gay historical inspired art#gay historical art

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA - Don't Treat JTTW As Modern Fiction

This is a public service announcement reminding JTTW fans to not treat the work as modern fiction. The novel was not the product of a singular author; instead, it's the culmination of a centuries-old story cycle informed by history, folklore, and religious mythology. It's important to remember this when discussing events from the standard 1592 narrative.

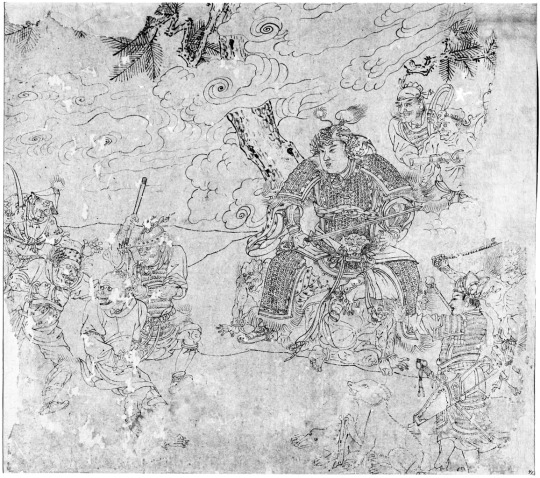

Case in point is the battle between Sun Wukong and Erlang. A friend of a friend claims with all their heart that the Monkey King would win in a one-on-one battle. They cite the fact that Erlang requires help from other Buddho-Daoist deities to finish the job. But this ignores the religious history underlying the conflict. I explained the following to my acquaintance:

I hate to break it to you [name of person], but Erlang would win a million times out of a million. This is tied to religious mythology. Erlang was originally a hunting deity in Sichuan during the Han (202 BCE-220 CE), but after receiving royal patronage during the Later Shu (934-965) and Song (960-1279), his cult grew to absorb the mythos of other divine heroes. This included the story of Yang Youji, an ape-sniping archer, leading to Erlang's association with quelling primate demons. See here for a broader discussion.

This is exemplified by a 13th-century album leaf painting. The deity (right) oversees spirit-soldiers binding and threatening an ape demon (left).

Erlang was connected to the JTTW story cycle at some point, leading to a late-Yuan or early-Ming zaju play called The God Erlang Captures the Great Sage Equaling Heaven (二郎神鎖齊天大聖). In addition, The Precious Scroll of Erlang (二郎寳卷, 1562), a holy text that predates the 1592 JTTW by decades, states that the deity defeats Monkey and tosses him under Tai Mountain.

So it doesn't matter how equal their battle starts off in JTTW, or that other deities join the fray, Erlang ultimately wins because that is what history and religion expects him to do.

And as I previously mentioned, Erlang has royal patronage. This means he was considered an established god in dynastic China. Sun Wukong, on the other hand, never received this badge of legitimacy. This was no doubt because he's famous for rebelling against the Jade Emperor, the highest authority. No human monarch in their right mind would publicly support that. Therefore, you can look at the Erlang-Sun Wukong confrontation as an established deity submitting a demon.

I'm sad to say that my acquaintance immediately ignored everything I said and continued debating the subject based on the standard narrative. That's when I left the conversation. It's clear that they don't respect the novel; it's nothing more than fodder for battleboarding.

I understand their mindset, though. I love Sun Wukong more than just about anyone. I too once believed that he was the toughest, the strongest, and the fastest. But learning more about the novel and its multifaceted influences has opened my eyes. I now have a deeper appreciation for Monkey and his character arc. Sure, he's a badass, but he's not an omnipotent deity in the story. There is a reason that the Buddha so easily defeats him.

In closing, please remember that JTTW did not develop in a vacuum. It may be widely viewed around the world as "fiction," but it's more of a cultural encyclopedia of history, folklore, and religious mythology. Realizing this and learning more about it ultimately helps explain why certain things happen in the tale.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#jttw#Erlang#Erlang shen#Buddhism#Taoism#Chinese mythology#Chinese religion

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sleeping Satyr(Sátiro Adormecido), c.220 BCE Glyptothek Museum of Greek and Roman Sculptures, Munich

#dark academia#dark aesthetic#dark acadamia aesthetic#grunge#book quotes#books#coffee#poets on tumblr#academia#books & libraries#mythologie#norse mythology#celtic mythology#mythological#mythology greek

993 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History of Buddhism

Buddhism was established in India by Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha, l. c. 563-c. 483 BCE) and developed between c. 400 BCE and 383 BCE before it spread to other regions through the efforts of the Mauryan king Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE). Understood as both a philosophy and a religion, Buddhism today attracts adherents around the world.

Continue reading...

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female Europid Mummy from the Necropolis of Subexi III, Grave M6, Turfan District, Xinjiang. 5th-3rd C. BCE. Source: Baumer, Christoph.The history of Central Asia. Vol.1. The age of the steppe warriors. London : I.B. Tauris, 2012. pg. 218 left DS329.4 .B38 2012. Image via University of Pennsylvania. See maps in the post before this one for a better understanding of the geography discussed.

"Section 26 – The Kingdom of Nearer [i.e. Southern] Jushi 車師前 (Turfan)

1. ‘Nearer Jushi’ 車師前 refers to the kingdom or state centered in the Turfan oasis or, sometimes, to the tribe which controlled it. There can be no question that Nearer Jushi refers here to the Turfan Oasis. See for example: CICA, p. 183, n. 618; also note 1.5 above. For the etymology of the name Turfan see Bailey (1985), pp. 99-100, which is summed up in his sentence: “The name turpana- is then from *druva-pāna- ‘having safe protection’, a name suitable for a walled place.”

“One other oasis town is currently under excavation. At Yarghul (Jiaohe), 10 km (16 miles) [sic – this should read 10 miles (16 km)] west of Turpan, archaeologists have been excavating remains of the old Jushi capital, a long (1,700 m (5,580 ft)) but narrow (200 m (656 ft)) town between two rivers. From the Han period they uncovered vast collective shaft tombs (one was nearly 10 m (33 ft) deep). The bodies had apparently already been removed from these tombs but accompanying them were other pits containing form one to four horse sacrifices, with tens of horses for each of the larger burials.” Mallory and Mair (2000), pp. 165 and 167.

“Some 300 km (186 miles) to the west of Qumul [Hami] lie [mummy] sites in the vicinity of the Turpan oasis that have been assigned to the Ayding Lake (Aidinghu) culture. The lake itself occupies the lowest point in the Turpan region (at 156 m (512 ft) below sea level it is the lowest spot on earth after the Dead Sea). According to accounts of the historical period, this was later the territory of the Gushi, a people who ‘lived in tents, followed the grasses and waters, and had considerable knowledge of agriculture. They owned cattle, horses, camels, sheep and goats. They were proficient with bows and arrows.’ They were also noted for harassing travellers moving northwards along the Silk Road from Krorän, and the territories of the Gushi and the kingdom of Krorän were linked in the account of Zhang Qian, presumably because both were under the control of the Xiongnu. In the years around 60 BC, Gushi fell to the Chinese and was subsequently known as Jushi (a different transcription of the same name).” Mallory and Mair (2000), pp. 143-144.

“History records that in 108 BC Turpan was inhabited by farmers and traders of Indo-European stock who spoke a language belonging to the Tokharian group, an extinct Indo-Persian language [actually more closely related to Celtic languages]. Whoever occupied the oasis commanded the northern trade route and the rich caravans that passed through annually. During the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) control over the route see-sawed between Xiongnu and Han. Until the fifth century, the capital of this kingdom was Jiaohe.” Bonavia (1988), p. 131.

“Turpan is principally an agricultural oasis, famed for its grape products – seedless white raisins (which are exported internationally) and wines (mostly sweet). It is some 80 metres (260 feet) below sea level, and nearby Aiding Lake, at 154 metres (505 feet) below sea level, is the lowest continental point in the world.” Ibid. p. 137.

“The toponym Turfan is also a variation of Tuharan. Along the routes of Eurasia there are many other place names recorded in various Chinese forms that are actually variations of Tuharan.” Liu (2001), p. 268."

-Notes to The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Second Edition (Extensively Revised and Expanded). John E. Hill. University of Washington.

#tocharian#celtic#indo european#tarim basin#xinjiang#chinese history#mummies#history#ancient history#archaeology#anthropology#silk road#pagan

462 notes

·

View notes

Photo

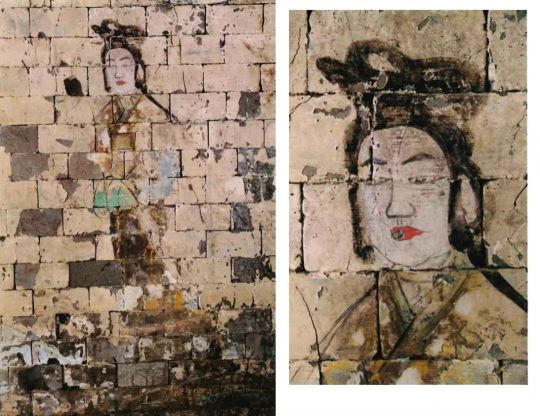

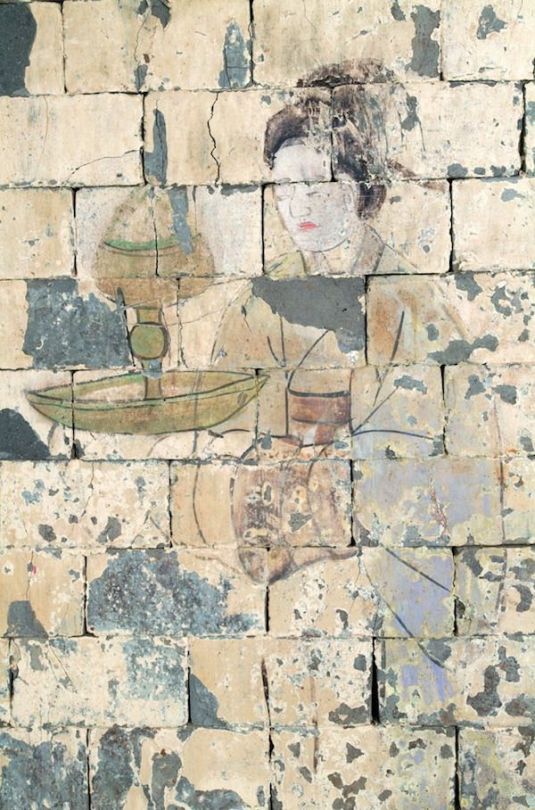

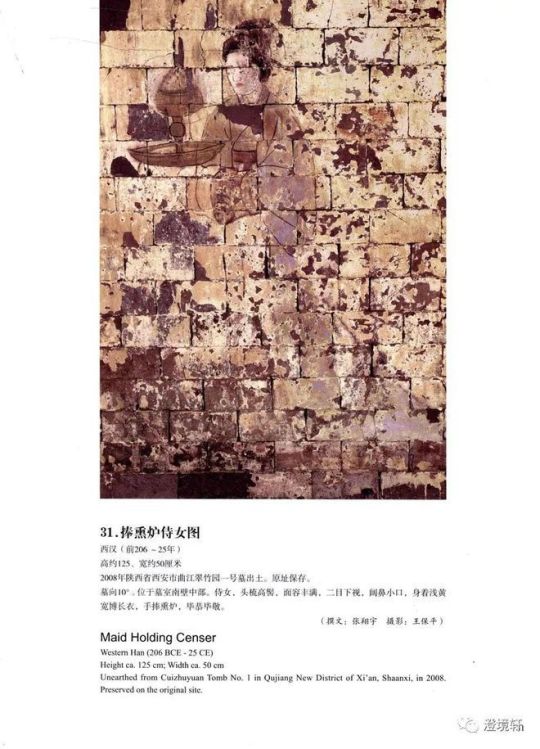

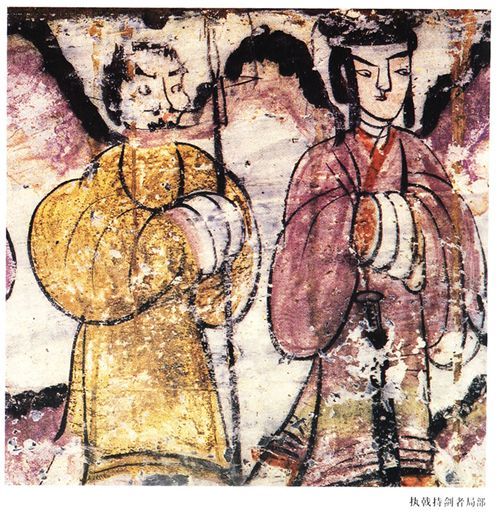

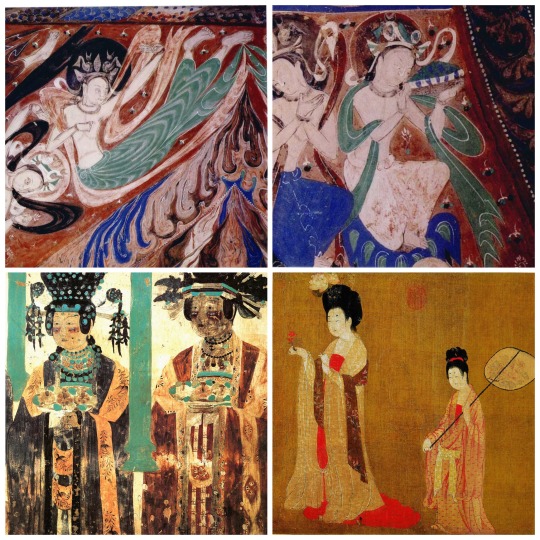

【Han Dynasty Historical Reference Artifacts】:

As early as the late Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE-25S CE), the High hair bun became popular, and it was no longer limited to the low hairstyle like early Western Han Dynasty (put the hair down and tied behind the back). Moreover, high hair bun it has been popular until the Eastern Han Dynasty(25–220) and Wei & Jin Dynasty.

According to the "Ballad in the City《城中谣》" of the Han Dynasty:

城中好高髻,四方高一尺。

城中好广眉,四方且半额。

城中好大袖,四方全匹帛。

【Translate】

High buns are popular in the city, and people all over the world have buns that are one foot taller.

Wide eyebrow are popular in the city, and people in the world draw(eyebrow) half their foreheads.

Big sleeves are popular in the city, and people all over the world use whole pieces of cloth to make them.

※" Ballad in the City 《城中谣》" is a folk song in "Yuefu Poetry Collection Miscellaneous Songs and Ballads《乐府诗集·杂歌谣辞》". On the surface, it talks about the fashion and its variation in the Han Dynasty, but actually satirizes the social atmosphere of blindly following the trend at that time.

---------

In addition, There were also changes in the way of dressing in the Western Han Dynasty and Eastern Han Dynasty Period.

Left:Murals of the Eastern Han Dynasty from Dahuting Han tombs

Right: female pottery figurines of the Western Han Dynasty (presumably early Western Han Dynasty)

------------

Western Han Dynasty Mural Tomb unearthed from Xi'an University of Technology↓

Western Han Dynasty Mural,Unearthed from Cuizhuyuan Tomb No lin Qujiang New District of Xi'an, Shaanxi, in 2008

Western Han Dynasty Murals, Luoyang Museum Collection

Eastern Han Dynasty Mural in Lujiazhuang, Anping County/安平县逯家庄东汉壁画墓

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Photoshoot

_______

📸Photo:@松果sir

👗Hanfu:@桑纈

📍Filming Location: Minhou, Fuzhou,China

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/3250619702/N4GoJiBmz

_______

#chinese hanfu#Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 A.D.)#western han dynasty#chinese history#chinese traditional clothing#hanfu history#chinese archeology#chinese#chinese historical fashion#hanfu#hanfu photoshoot#China History#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#漢服#汉服#松果sir#桑纈

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earring, Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). Gold with turquoise inlays.

Excavated in 1996, from Tomb I. Gouxi, the Ancient City of Jiaohe.

Collection of Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology.

From 'Mountain Tianshan. Ancient Roads. The Meeting of East and West:

The Extraordinary Cultural Relics from the Silk Road in Xinjiang', 2002.

Courtesy Alain Truong

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

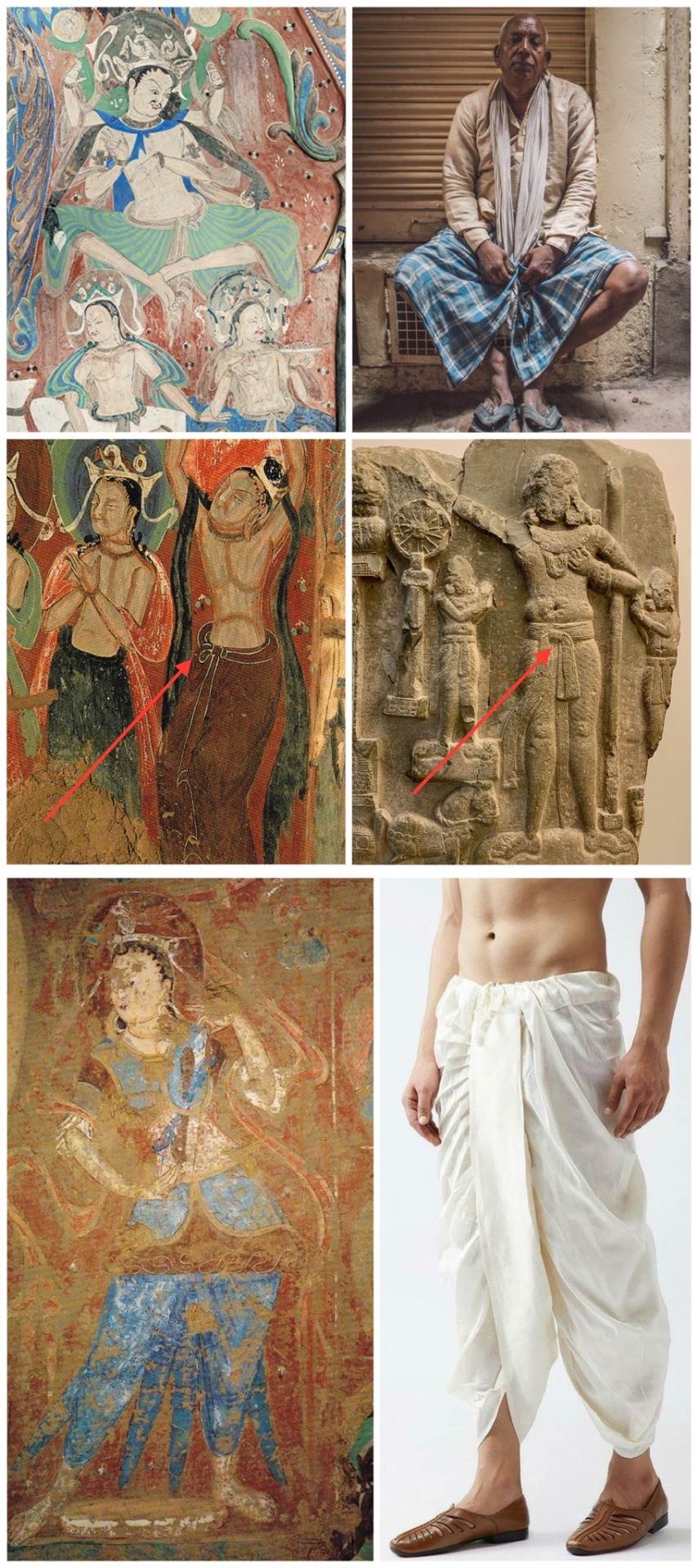

Origins of the Pibo: Let’s take a trip along the Silk Road.

1. Introduction to the garment:

Pibo 披帛 refers to a very thin and long shawl worn by women in ancient East Asia approximately between the 5th to 13th centuries CE. Pibo is a modern name and its historical counterpart was pei 帔. But I’ll use pibo as to not confuse it with Ming dynasty’s xiapei 霞帔 and a much shorter shawl worn in ancient times also called pei.

Below is a ceramic representation of the popular pibo.

A sancai-glazed figure of a court lady, Tang Dynasty (618–690, 705–907 CE) from the Sze Yuan Tang Collection. Artist unknown. Sotheby’s [image source].

Although some internet sources claim that pibo in China can be traced as far back as the Qin (221-206 BCE) or Han (202 BCE–9 CE; 25–220 CE) dynasties, we don’t start seeing it be depicted as we know it today until the Northern and Southern dynasties period (420-589 CE). This has led to scholars placing pibo’s introduction to East Asia until after Buddhism was introduced in China. Despite the earliest art representations of the long scarf-like shawl coming from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, the pibo reached its popularity apex in the Tang Dynasty (618–690 CE: 705–907 CE).

Academic consensus: Introduction via the Silk Road.

The definitive academic consensus is that pibo evolved from the dajin 搭巾 (a long and thin scarf) worn by Buddhist icons introduced to China via the Silk Road from West Asia.

披帛是通过丝绸之路传入中国的西亚文化, 与中国服饰发展的内因相结合而流行开来的一种"时世妆" 的形式. 沿丝绸之路所发现的披帛, 反映了丝绸贸易的活跃.

[Trans] Pibo (a long piece of cloth covering the back of the shoulders) was a popular female fashion period accessory introduced to China by West Asian cultures by way of the Silk Road and the development of Chinese costumes. The brocade scarves found along the Silk Road reflect the prosperity of the silk trade that flourished in China's past (Lu & Xu, 2015).

I want to add to the above theory my own speculation that, what the Chinese considered to be dajin, was most likely an ancient Indian garment called uttariya उत्तरीय.

2. Personal conjecture: Uttariya as a tentative origin to pibo.

In India, since Vedic times (1500-500 BCE), we see mentions in records describing women and men wearing a thin scarf-like garment called “uttariya”. It is a precursor of the now famous sari. Although the most famous depiction of uttariya is when it is wrapped around the left arm in a loop, we do have other representations where it is draped over the shoulders and cubital area (reverse of the elbow).

Left: Hindu sculpture “Mother Goddess (Matrika)”, mid 6th century CE, gray schist. Artist unknown. Looted from Rajasthan (Tanesara), India. Photo credit to Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States [image source].

Right: Rear view of female statue possibly representing Kambojika, the Chief Queen of Mahakshatrapa Rajula, ca. 1st century CE. Artist unknown. Found in the Saptarishi Mound, Mathura, India. Government Museum, Mathura [image source].

Buddhism takes many elements from Hindu mythology, including apsaras अप्सरा (water nymphs) and gandharvas गन्धर्व (celestial musicians). The former was translated as feitian 飞天 in China. Hindu deities were depicted wearing clothes similar to what Indian people wore, among which we find uttariya, often portrayed in carvings and sculptures of flying and dancing apsaras or gods to show dynamic movement. Nevertheless, uttariya long predated Buddhism and Hinduism.

Below are carved representation of Indian apsaras and gandharvas. Notice how the uttariya are used.

Upper left: Carved relief of flying celestials (Apsara and Gandharva) in the Chalukyan style, 7th century CE, Chalukyan Dynasty (543-753 CE). Artist Unknown. Aihole, Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source]. The Chalukyan art style was very influential in early Chinese Buddhist art.

Upper right: Carved relief of flying celestials (gandharvas) from the 10th to the 12th centuries CE. Artist unknown. Karnataka, India. National Museum, New Delhi, India [image source].

Bottom: A Viyadhara (wisdom-holder; demi-god) couple, ca. 525 CE. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Nomu420 on May 10, 2014. Sondani, Mandsaur, India [image source].

Below are some of the earliest representations of flying apsaras found in the Mogao Caves, Gansu Province, China. An important pilgrimage site along the Silk Road where East and West met.

Left to right: Cave No. 461, detail of mural in the roof of the cave depicting either a flying apsara or a celestial musician. Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285 flying apsara (feitian) in one of the Mogao Caves. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE), Artist unknown. Photo taken by Keren Su for Getty Images. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 249. Mural painting of feitian playing a flute, Western Wei Dynasty (535-556 CE). Image courtesy by Wang Kefen from The Complete Collection of Dunhuang Grottoes, Vol. 17, Paintings of Dance, The Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 2001, p. 15. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

I theorize that it is likely that the pibo was introduced to China via Buddhism and Buddhist iconography that depicted apsaras (feitian) and other deites wearing uttariya and translated it to dajin.

3. Trickle down fashion: Buddhism’s journey to the East.

However, since Buddhism and its Indian-based fashion spread to West Asia first, to Sassanian Persians and Sogdians, it is likely that, by the time it reached the Han Chinese in the first century CE, it came with Persian and Sogdian influence. Persians’ fashion during the Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE) was influenced by Greeks (hellenization) who also had a a thin long scarf-like garment called an epliblema ἐπίβλημα, often depicted in amphora (vases) of Greek theater scenes and sculptures of deities.

Left to right: Dame Baillehache from Attica, Greece. 3rd century BCE, Hellenistic period (323-30 BCE), terracotta statuette. Photo taken by Hervé Lewandowski. Louvre Museum, Paris, France [image source].

Deatail view of amphora depicting the goddess Artemis by Athenian vase painter, Andokides, ca. 525 BCE, terracotta. Found in Vulci, Italy. Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany [image source].

Statue of a Kore (young girl), ca. 570 BCE, Archaic Period (700-480 BCE), marble. Artist unknown. Uncovered from Attica, Greece. Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece [image source].

Detail view of Panathenaic (Olympic Games) prize amphora with lid, 363–362 BCE, Attributed to the Painter of the Wedding Procession and signed by Nikodemos, terracotta. Uncovered from Athens, Greece. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, United States [image source].

Roman statue depicting Euterpe, muse of lyric poetry and music, ca. 2nd century CE, marble, Artist unknown. From the Villa of G. Cassius Longinus near Tivoli, Italy. Photo taken by Egisto Sani on March 12, 2012, Vatican Museums, Rome, Italy [image source].

Greek (or Italic) tomb mural painting from the Tomb of the Diver, ca. 470 BCE, fresco. Artist unknown. Photo taken by Floriano Rescigno. Necropolis of Paestum, Italy [image source].

Below are Iranian and Iraqi period representations of this long thin scarf.

Left to right: Closeup of ewer likely depicting a female dancer from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia , Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 10, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Ewer with nude dancer probably representing a maenad, companion of Dionysus from the Sasanian Period (224–651 CE) in ancient Persia, Iran, 6th-7th century CE, silver and gilt. Artist unknown. Mary Harrsch. July 16, 2015. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Asian Art, Smithsonian, Washington D.C [image source].

Painting reconstructing the image of unveiled female dancers depicted in a fresco, Early Abbasid period (750-1258 CE), about 836-839 CE from Jawsaq al-Khaqani, Samarra, Iraq. Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul [image source].

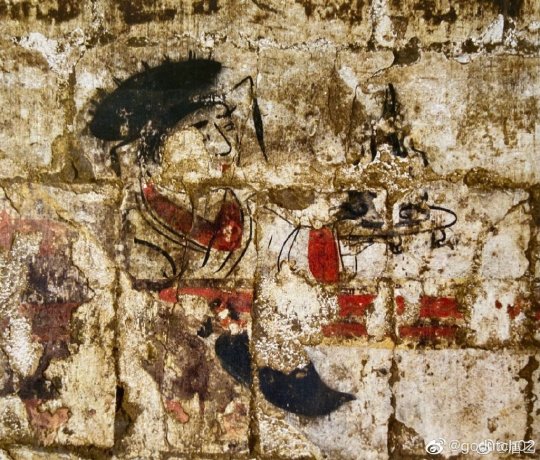

The earliest depictions of Buddha in China, were very similar to West Asian depictions. Ever wonder why Buddha wears a long draped robe similar to a Greek himation (Romans called it toga)?

Take a look below at how much the Greeks influenced the Kushans in their art and fashion. The top left image is one of the earliest depictions of Buddha in China. Note the similarities between it and the Gandhara Buddha on the right.

Left: Seated Buddha, Mahao Cliff Tomb, Sichuan Province, Eastern Han Dynasty, late 2nd century C.E. (photo: Gary Todd, CC0).

Right: Seated Buddha from Gandhara, Pakistan c. 2nd–3rd century C.E., Gandhara, schist (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Standing Bodhisattva Maitreya (Buddha of the Future), ca. 3rd century, gray schist. From Gandhara, Pakistan. Image credit to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States [image source].

Statue of seated goddess Hariti with children, ca. 2nd to 3rd centuries CE, schist. Artist unknown. From Gandhara, Pakistan. The British Museum, London, England [image source].

Before Buddhism spread outside of Northern India (birthplace), Indians never portrayed Buddha in human form.

Early Buddhist art is aniconic, meaning the Buddha is not represented in human form. Instead, Buddha is represented using symbols, such as the Bodhi tree (where he attained enlightenment), a wheel (symbolic of Dharma or the Wheel of Law), and a parasol (symbolic of the Buddha’s royal background), just to name a few. […] One of the earliest images [of Buddha in China] is a carving of a seated Buddha wearing a Gandharan-style robe discovered in a tomb dated to the late 2nd century C.E. (Eastern Han) in Sichuan province. Ancient Gandhara (located in present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India) was a major center for the production of Buddhist sculpture under Kushan patronage. The Kushans occupied portions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and North India from the 1st through the 3rd centuries and were the first to depict the Buddha in human form. Gandharan sculpture combined local Greco-Roman styles with Indian and steppe influences (Chaffin, 2022).

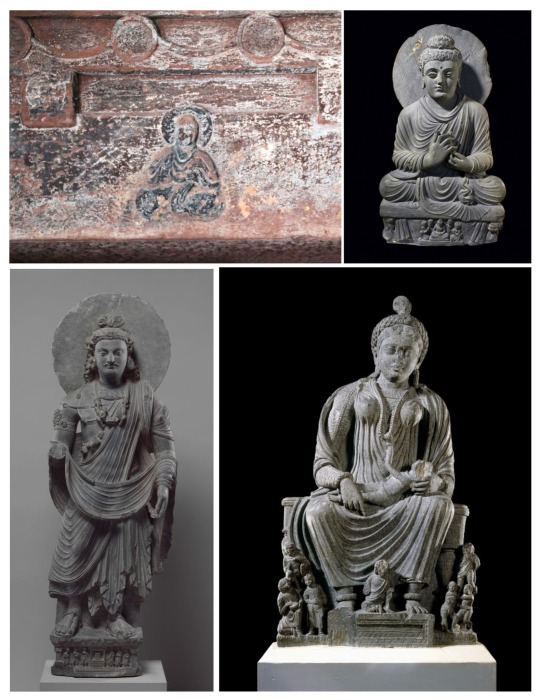

In the Mogao Caves, which contain some of the earliest Buddhist mural paintings in China, we see how initial Chinese Buddhist art depicted Indian fashion as opposed to the later hanfu-inspired garments.

Left to right: Cave 285, detail of wall painting, Western Wei dynasty (535–556 CE). Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Courtesy the Dunhuang Academy [image source]. Note the clothes the man is wearing. It looks very similar to a lungi (a long men’s skirt).

Photo of Indian man sitting next to closed store wearing shirt, scarf, lungi and slippers. Paul Prescott. February 20, 2015. Varanasi, India [image source].

Cave 285, mural depiction of worshipping bodhisattvas, 6th century CE, Wei Dynasty (535-556 A.D.), Unknown artist. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. Notice the half bow on his hips. That is a common style of tying patka (also known as pataka; cloth sashes) that we see throughout Indian history. Many of early Chinese Buddhist paintings feature it, including the ones at Mogao Caves.

Indian relief of Ashoka wearing dhoti and patka, ca. 1st century BC, Unknown artist. From the Amaravathi village, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Currently at the Guimet Museum, Paris [image source].

Cave 263. Mural showing underlying painting, Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535 CE). Artist Unknown. Picture taken November 29, 2011, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source]. Note the pants that look to be dhoti.

Comparison photo of modern dhoti advertisement from Etsy [image source].

Spread of Buddhism to East Asia.

Map depicting the spread of Buddhism from Northern India to the rest of Asia. Gunawan Kartapranata. January 31, 2014 [image source]. Note how Mahayana Buddhism arrived to China after passing through Kushan, Bactrean, and nomadic steppe lands, absorbing elements of each culture along the way.

Wealthy Buddhist female patrons emulated the fantasy fashion worn by apsaras, specifically, the uttariya/dajin and adopted it as an everyday component of their fashion.

Cave 285. feitian mural painting on the west wall, Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 285. Detail view of offering bodhisattvas (bodhisattvas making offers to Buddha) next to the phoenix chariot on the Western wall of the cave. Western Wei Dynasty (535–556 CE). Artist unknown. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Cave 61 Khotanese (from the kingdom of Khotan 于阗 [56–1006 CE]) donor ladies, ca. 10th century CE, Five Dynasties period (907 to 979 CE). Artist unknown. Picture scanned from Zhang Weiwen’s Les oeuvres remarquables de l'art de Dunhuang, 2007, p. 128. Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons on October 11, 2012 by Ismoon. Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China [image source].

Detail view of Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers 簪花仕女图, late 8th to early 9th century CE, handscroll, ink and color on silk, Zhou Fang 周昉 (730-800 AD). Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China [image source].

Therefore, the theory I propose of how the pibo entered East Asia is:

India —> Greek influenced West Asia (Sassanian Persians, Sogdians, Kushans, etc…) —> Han China —> Rest of East Asia (Three Kingdoms Korea, Asuka Japan, etc…)

Thus, the most likely theory, in my person opinion, is Buddhist iconography depicting uttariya encountered Greek-influenced West Asian Persian, Sogdian, and Kushan shawls, which combined arrived to China but wouldn’t become commonplace there until the explosion in popularity of Buddhism from the periods of Northern and Southern Dynasties to Song.

References:

盧秀文; 徐會貞. 《披帛與絲路文化交流》 [The brocade scarf and the cultural exchanges along the Silk Road]. 敦煌研究 (中國: 敦煌研究編輯部). 2015-06: 22 – 29. ISSN 1000-4106.

#hanfu#chinese culture#chinese history#buddhism#persian#sogdian#kushan#gandhara#indian fashion#uttariya#pibo#history#asian culture#asian art#asian history#asian fashion#east asia#south asia#india#pakistan#iraq#afghanistan#sassanian#silk road#fashion history#tang dynasty#eastern han dynasty#cultural exchange#greek fashion#mogao caves

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tianlong 天龍 "Heavenly Dragon"

Talon Abraxas

Among Chinese classic texts, tian "heaven" and long "dragon" were first used together in Zhou Dynasty (1122 BCE – 256 BCE) writings, but the word tianlong was not recorded until the Han Dynasty (207 BCE – 220 CE).

The ancient Yijing "Book of Changes" exemplifies using tian "heaven" and long "dragon" together. Qian 乾 "The Creative", the first hexagram, says:

九五,飞龙在天,利见大人

Nine (it stands for a solid horizontal line that symbolizes the yang. Why nine is used is unclear.) in the fifth place means: Flying dragons in the heavens. It furthers one to see the great man.

— Qian 乾 "The Creative", Yijing

46 notes

·

View notes