#Hubei Provincial Museum

Text

"My boss wanted us to make a promotion video with the elements of loong" A promotion video for the Hubei Provincial Museum.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Late Warring States period(475–221 BC) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Based On Chu (state)Historical Artifacts

【Historical Artifact Reference】:

Late Warring States period(475–221 BC):Two conjoined jade dancers unearthed from Jincun, Luoyang,collected by Freer Museum of Art

A similar jade dancer was also unearthed from the tomb of Haihunhou, the richest royal family member in the Han Dynasty, and was one of his treasures.

Warring States period, Eastern Zhou dynasty, 475-221 BCE,jade dancer by Freer Gallery of Art Collection.

Warring States period(475–221 BC)·Silver Head Figurine Bronze Lamp.Unearthed from the Wangcuo Tomb in Zhongshan state during the Warring States Period and collected by the Hebei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology

The figurine of a man dressed as a woman holds a snake in his hand, and 3 snakes correspond to 3 lamps.

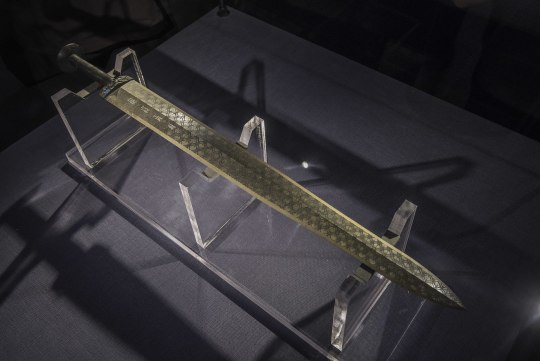

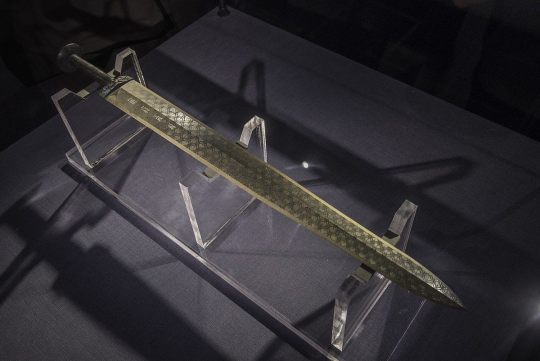

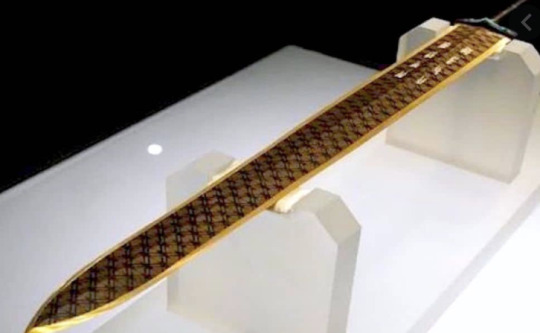

Sword of Goujian/越王勾践剑:

The Sword of Goujian (Chinese: 越王勾践剑; pinyin: Yuèwáng Gōujiàn jiàn) is a tin bronze sword, renowned for its unusual sharpness, intricate design and resistance to tarnish rarely seen in artifacts of similar age. The sword is generally attributed to Goujian, one of the last kings of Yue during the Spring and Autumn period.

In 1965, the sword was found in an ancient tomb in Hubei. It is currently in the possession of the Hubei Provincial Museum.

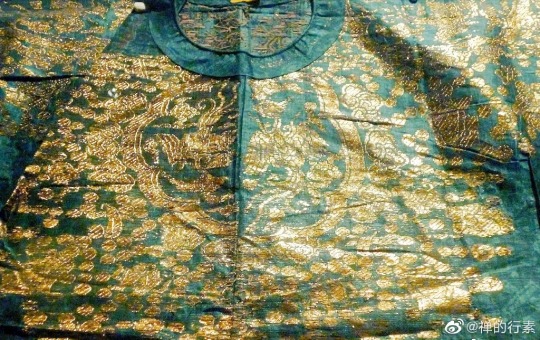

【Histoty Note】Late Warring States Period·Noble Women Fashion

The attire of noblewomen in the late Warring States period, as reconstructed in this collection, is based on a comprehensive examination of garments and textiles unearthed from the Chu Tomb No. 1 at Mashan, Jiangling, as well as other artifacts from the same period.

During the late Warring States period, both noble men and women favored wearing robes that were connected from top to bottom. These garments were predominantly made of gauze, silk, brocade, and satin, with silk edging. From the Chu Tomb No. 1 at Mashan, there were discoveries of robes entirely embroidered or embroidered fragments. The embroidery technique employed was known as "locked stitches," which gave the patterns a three-dimensional, lively appearance, rich in decoration.

The two reconstructed robes in this collection consist of an inner robe made of plain silk with striped silk edging, and an outer robe made of brocade, embroidered with phoenixes and floral patterns, with embroidered satin edging. Following the structural design of clothing found in the Mashan Chu Tomb, rectangular fabric pieces were inserted at the junction of the main body, sleeves, and lower garment of the robe. Additionally, an overlap was made at the front of the main body and the lower garment to enlarge the internal space for better wrapping around the body curves. Furthermore, the waistline of the lower garment was not horizontal but inclined upward at an angle, allowing the lower hem to naturally overlap, forming an "enter" shape, facilitating movement.

The layered edging of the collars and sleeves of both inner and outer robes creates a sense of rhythm, with the two types of brocade patterns complementing each other, resulting in a harmonious effect. Apart from the robes, a wide brocade belt was worn around the waist, fastened with jade buckle hooks, and adorned with jade pendants, presenting an elegant and noble figure.

The reconstructed hairstyle draws inspiration from artifacts such as the jade dancer from the late Warring States period unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun Tomb in Nanchang, and the jade dancer from the Warring States period unearthed at Jin Village in Luoyang. It features a fan-shaped voluminous hairdo on the crown, with curled hair falling on both sides, and braided hair gathered at the back. The Book of Songs, "Xiao Ya: Duren Shi," vividly depicts the flowing curls of noblewomen during that period. Their images of curly-haired figures in long robes were also depicted in jade artifacts and other relics, becoming emblematic artistic representations.

The maturity and richness of clothing art in the late Warring States period were unparalleled in contemporary world civilizations, far beyond imagination. It witnessed the transition of Chinese civilization into the Middle Ages. The creatively styled garments and intricate fabric patterns from the Warring States period carry the unique essence, mysterious imagination, and ultimate romanticism of that era, serving as an endless source of artistic inspiration.

--------

Recreation Work by : @裝束复原

Weibo 🔗:https://weibo.com/1656910125/O6cUMBa1j

--------

#chinese hanfu#Late Warring States Period#Warring States period(475–221 BC)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#chinese traditional clothing#hanfu_challenge#chinese#china#historical#historical fashion#chinese history#china history#漢服#汉服#中華風#裝束复原

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

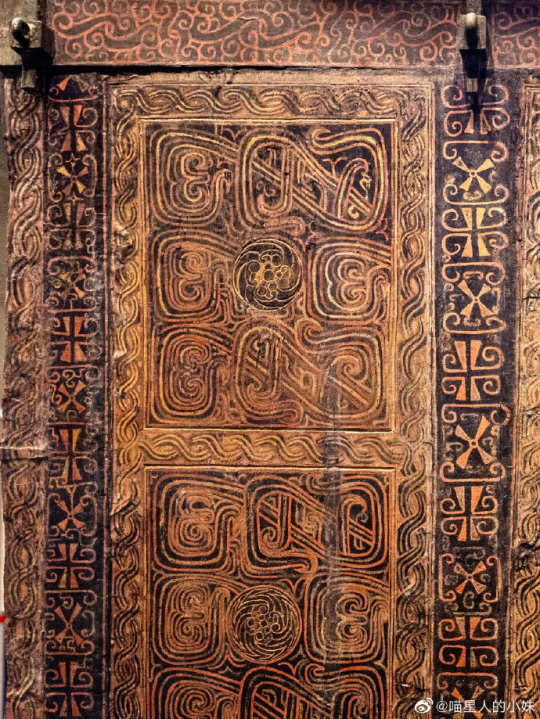

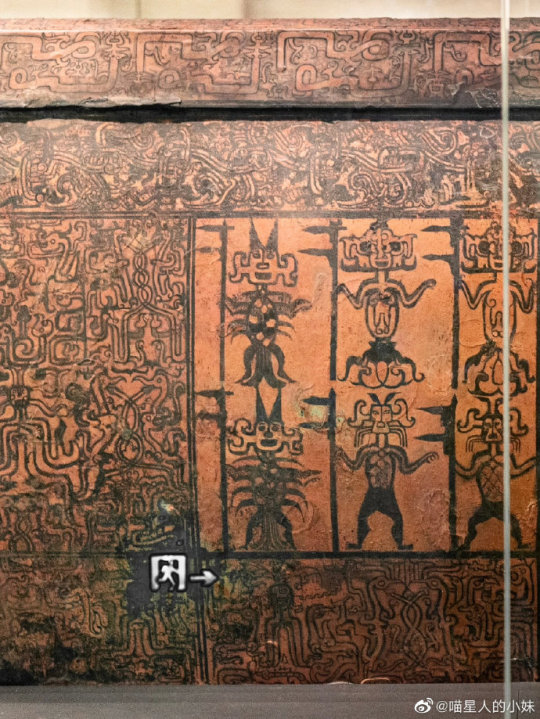

Luxury Lacquered Coffin of Marquis Yi: Largest in History

The coffin of the Warring States period was unearthed from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (曾侯乙) in Leigudun (擂鼓墩), Suizhou, Hubei, in 1978.

The outer coffin is 3.2 meters long, 2.1 meters wide, 2.2 meters high, and weighs about 7 tons. It is composed of 10 copper columns embedded within 10 wooden boards of the same height. The painting on the surface of one of the coffins depicts weird and armed anthro-zoomorphic beings.

Displayed in Hubei Provincial Museum (湖北省博物馆).

Photo: ©喵星人的小姐

#ancient china#chinese culture#chinese art#chinese history#coffin#ancient tomb#burial#warring states period#warring states era#artefact#lacquer#曾侯乙墓#laquerware#tomb art#archeology#chinese customs

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

kinda random but seeing all the ppl in the notes of this post from the hubei provincial museum saying "yean this promo worked on me" makes me smile bc. i've been to that museum and it really is great. my mom's parents live in wuhan so we visited there a bunch when i was younger and that museum was always a place i looked forward to going (and i got to go to one of their chime shows once too!) it's genuinely such an awesome place, the artifacts are stunning and the presentation is beautiful, and the whole place is full of gorgeous cultural history. i really want to go back now that i'm an adult and can better appreciate it all. mutuals we are taking a trip there together etc etc

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Stuff #10: Daoist Elements and More in The Untamed/MDZS Part 2 - Weapons and Magical Objects

(Part 1 Here) (Super-long post ahead!)

Talismans/Charms/符箓/符咒

The talismans in both the live-action and animated shows originate from Daoist talismans, which in turn developed from early shamanistic traditions. Like what Lan Wangji tells Jiang Cheng in the show, real life Daoist talismans are usually made for beneficial purposes, one of which being to ward off evil spirits. Other purposes of such talismans include everything from curing illnesses to controlling floods to communicating with the gods. In order to call forth gods to accomplish these goals, writing/drawing on the talismans usually include “incantations” that start with “勅令”, or “command”, on the very top. The word can be traced back to 敕令, which refers to orders from an emperor, but since 敕 is traditionally reserved for the emperor, Daoists use 勅 on their talismans. The meaning is also slightly changed, as 敕 has 攵 on the right, implying the order is written; meanwhile 勅 has 力/force on the right, implying the order is executed by “force”.

The body of the talisman sometimes include complex combinations of Chinese characters (合体字/複文) that are more like visual symbols and do not have their own pronunciations. On a talisman these “combination characters” are usually arranged in a specific pattern. These combination characters aren’t exclusive to Daoism, however. Below is a well-known combination character created from the word 招財進寶 (lit: “gaining wealth and attracting riches”), commonly seen pasted on doors and windows around Chinese New Year for luck.

Other elements of a talisman are mostly made up of symbols such as the yinyang symbol, eight trigrams, and special strokes that also hold symbolic meaning.

A fun detail from the animated show: in the scene where Jiang Cheng shows the inverted evil-warding talisman to Lan Wangji, we can see that WWX’s addition in blood near the top turns the 人 part into 夷, as in 夷陵老祖/”Yiling Founder”, giving the viewer a solid hint as to who changed the talismans.

Sword (Jian)/剑

Jian sword refers specifically to pointed double-edged one-handed straight swords. The sword is important to religious Daoism, but its origin as a culturally-significant symbol lies in history.

The sword was an actual weapon used on the battlefield before Han dynasty (before 202 BC), and it was that time, long long ago, that the sword was associated with certain human qualities, such as an unyielding sense of justice. From there, the jian sword eventually became an ornamental item symbolizing high social status. Evidences of this can be found in the Book of Rites (《禮記》), a book detailing etiquettes and rituals for nobles of Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC). For example, a chapter mentioned “when looking upon a gentleman’s attire, sword, and carriage horse, do not gossip about their value” (“觀君子之衣服,服劍,乘馬,弗賈”). One such decorative jian sword artifact even survived to this day:

Sword of Goujian, King of Yue (越王勾践剑), part of the collection of Hubei Provincial Museum. Note: the engraved “bird-worm seal script” (鳥蟲篆; basically a highly decorative font) text says “Goujian, King of Yue, made this sword for his personal use” (戉王鸠浅,自乍用鐱).

By the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 AD), Daoism had established itself as a folk religion. Many of the customs and etiquettes passed down from pre-Qin dynasty times were mystified and given religious importance in the then newly-established Daoist belief system, including the aforementioned etiquettes involving the jian sword. People came to believe the jian sword as holding magical properties, a weapon gifted by heaven itself, allowing its wielder (usually a Daoist priest) to fight and triumph over demonic spirits. As the jian sword became more and more of a Daoist ceremonial item than an actual weapon, it also slowly changed to this familiar form today:

(Modern ceremonial Daoist jian swords. Fun fact: it is widely believed that jian swords made entirely of peach wood have better demon-banishing abilities than regular swords, since peach trees were said to have demon-warding effects.)

So, a sword that was worn to show respect, used to showcase social status AND have demon-warding powers? Does that sound familiar?

It was no accident that the day WWX refused to take his sword with him (since he gave his core to Jiang Cheng so Jiang Cheng could continue to use swords) was also the day the other sects/clans started to alienate him. The sword symbolized status, and WWX was only the son of a servant, a “lone genius” (一枝独秀/”a lone blooming branch”, in the words of Jiang Cheng) among all the young nobles, so it was fitting that WWX abandoned the “righteous” sword path to walk a new and unique path in order to reach his full potential.

“Fly whisk”/“duster”/fu chen/拂尘

Remember the funny-looking duster-like objects that Song Lan and Xiao Xingchen held in the live action series? Those are called fu chen, or “拂尘” in Chinese, and hold symbolic meaning in Daoism. To explore that meaning, let’s first explain the name “fu chen”. Fu chen literally means “brush dust”, so the Chinese meaning is really more like “duster” than the common English translation of “fly whisk”. But then what sort of “dust” is it really “brushing”?

The concept of “dust” (尘) in both Daoism and Chinese Buddhism refers to the normal secular human society, with all of its material objects and worldly wants and worries. Thus, the symbolic meaning of fu chen/“duster” is to clear these worries and wants--in other words, worldly attachments--from one’s mind, allowing one to exit the secular world. For this reason, in China, the process of abandoning one’s normal life in society for the life of a Daoist priest or Buddhist monk is called “出家” (lit. “exiting home”) or “出世” (lit. “exiting world”; world here meaning society).

Since both Song Lan and Xiao Xingchen are Daoist priests (they were both referred to as “道长”), and both wandered through the world banishing evil rather than settling down somewhere and integrating into society, it was a nice choice to have them each hold a fu chen.

"Stygian Tiger Seal" or “Yin Tiger Seal”/阴虎符

This one is a non-Daoist reference, but it’s still rooted in Chinese history, so here we go.

The fact that the Stygian Tiger seal is called a “tiger seal”/虎符 and has two halves that unleash powerful resentment energy when fitted together (this mechanism is present in both book and live-action but is absent in the animated show, where the two halves appear to be conjoined), points to the inspiration being the tiger amulet. In imperial China, tiger amulets/虎符 are metal tiger figurines that split into halves lengthwise, and serve the important purpose of approving military deployment. The imperial court would hold the right half, while the left half would be issued to military officials.

When army deployment is needed, the official would bring the left half of the figurine to the imperial court, and if it combines with the right half into a whole figurine, then the military deployment would be officially approved. Historically, tiger amulets are a security measure designed to give the imperial court control over the military.

Finally, some joke talismans I found on the web:

Translation: “No need to work overtime”; “hold the talisman and chant ‘PIKA PIKA’”, “will confuse your boss so you can get off work early”.

Translation: “passes exam without studying”, “bullshitting it”, “no need to study”. (I think I’ll need one of these lol................................)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sword of Goujian was found in 1965 in Hubei, China. Cast in tin bronze, it is renowned for its unusual sharpness and resistance to tarnish rarely seen in artifacts so old. This historical artifact of ancient China is currently in the possession of the Hubei Provincial Museum.

The sword was found sheathed in a wooden scabbard finished in black lacquer. The scabbard had an almost air-tight fit with the sword body. Unsheathing the sword revealed an untarnished blade, despite the tomb being soaked in underground water for over 2,000 years.

Spring and Autumn period (771 to 476 BCE)

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hubei Provincial Museum China

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wuhan Park - Tingtao Scenic Area

东湖听涛景区紧邻湖

East Lake Tingtao Scenic Area is adjacent to Hubei Provincial Museum. After visiting Shengbo, walk about 500 meters along the Oriole Road, which is shaded by ancient trees in the sky, and you can see the main entrance of Tingtao Scenic Area.

The scenic spot has been free for many years. If you enter the gate, you can see the East Lake Lotus Pond on the left.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Pierres, feuilles, repros ». Quelques réflexions sur le patrimoine et l’écrit dans les bibliothèques chinoises

Lou Delaveau effectue son stage de 4e année à la Bibliothèque de l'Université Wuhan. Voir la carte des stages

J’ai posé pour la première fois un pied en Chine le 14 septembre 2018. Mon stage de deux mois et demi avait pour objectif de me faire découvrir plus particulièrement la bibliothèque de l’Université de Wuhan (WHU ou Wuhan Daxue -« Wuda »). Cette Université, dont le magnifique campus arboré occupe une large partie de la ville, rassemble quatre bibliothèques principales pouvant accueillir près de 5500 lecteurs : la « Main Library », que j’ai surtout fréquentée, et trois bibliothèques « de branches » consacrées à des disciplines scientifiques.

Main Library de l’Université de Wuhan

D’autre part, plusieurs visites de la Bibliothèque du Hubei, province dont Wuhan est la capitale, m’ont offert un contrepoint passionnant en matière d’accueil du public. En outre, j’ai eu la chance, à l’occasion d’un séjour d’une semaine à Beijing, de pousser la porte de la Bibliothèque de l’Université du Peuple (Renmin University-RUC) et surtout de la Bibliothèque nationale. Ce billet de blog synthétise quelques particularités de la conservation des collections livresques en Chine, qui, en raison d’approches bibliothéconomiques différentes, avaient suscité, parfois, mon étonnement, et, toujours, mon intérêt.

La conservation des collections au cœur des bibliothèques chinoises

La question de la place du patrimoine écrit ancien s’est spontanément posée à moi lorsque j’ai franchi le seuil de la Bibliothèque de l’Université de Wuhan. Cette dernière possède en effet des collections remarquables : 200 000 ouvrages anciens dont plus de 300 inscrits au catalogue des livres chinois rares et anciens (Catalogue of Ancient Chinese Rare Books) et 66 à l’index des livres rares et anciens d’envergure nationale (National Rare Ancient Books Directory). Lors de mon stage, je n’ai donc pas été surprise de constater la présence d’un atelier de restauration prenant entièrement en charge la préservation des collections anciennes de la bibliothèque[1].

Salle de consultation de la Réserve des livres rares à la Bibliothèque universitaire de Wuhan

Dans les magasins de la Réserve, des étagères en bois de camphrier préservent les pages vénérables de l’humidité et des moisissures

Si de telles mesures n’ont rien d’étonnant dans le cadre de la protection des exemplaires anciens, rares ou précieux, il est tout aussi intéressant de considérer le sort réservé aux ouvrages « courants ». La préservation des collections a en effet traditionnellement été privilégiée dans les bibliothèques chinoises, quitte à supplanter parfois l’accueil des lecteurs, ainsi que le souligne Jing Liao dans un article rédigé en 2004[2] . Bien que des efforts importants aient été entrepris pour développer les services à destination des usagers, notamment à partir des années 1980[3] , encore aujourd’hui, le soin apporté à la conservation est décelable jusque dans le traitement des collections courantes et le processus d’acquisition. À la bibliothèque de WHU, plusieurs exemplaires sont systématiquement achetés, du moins lorsqu’il s’agit de livres édités en Chine, lesquels sont beaucoup moins onéreux que les ouvrages occidentaux[4] : l’un des exemplaires rejoint les étagères d’une Preserved area[5] tandis que les autres restent empruntables pour une longue durée. De semblables Preserved areas existent à la Bibliothèque de l’Université du Peuple, à la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei, mais aussi à la Bibliothèque nationale où tout lecteur peut emprunter des ouvrages ! Que l’emprunt de ces livres courants mais « préservés » soit impossible, réduit ou sujet à négociation[6], les Preserved areas ont pour but de rassembler en un même endroit l’ensemble des collections de l’institution afin de ne pas désavantager les lecteurs désireux de consulter un ouvrage dont l’exemplaire « de circulation libre » aurait été prêté. Cette volonté de « concentration/conservation des ouvrages » à l’intérieur de la bibliothèque, qui –il me semble- serait davantage, en France, l’apanage des bibliothèques patrimoniales, réconcilie en Chine (p)réservation des collections et attention aux besoins des usagers.

Qu’en est-il du sort des ouvrages dormant sur les étagères sans attirer l’attention des lecteurs ? Pour ce qui est de la question du « désherbage » qui me paraissait a priori centrale dans le cadre d’une bibliothèque universitaire[7], il m’a été difficile de me faire une opinion compte tenu de la divergence des réponses que j’ai récoltées dans les différentes bibliothèques. Quoi qu’il en soit, la destruction des exemplaires non consultés semble soulever d’âpres problématiques éthiques : le don de collections à des bibliothèques défavorisées, ou encore la conservation de ces exemplaires en compactus semble largement privilégiés.

Musée-Bibliothèque et Bibliothèque-Musée

À mi-chemin entre les collections précieuses des Réserves et les collections courantes se trouvent certains fonds spécialisés. La Bibliothèque de Renmin, par exemple, apporte un grand soin à la collecte des ouvrages écrits par les professeurs ou anciens élèves de l’Université : ces exemplaires, conservés dans des armoires vitrées, portent les dédicaces de leurs auteurs et il n’est, bien entendu, pas possible de les emprunter. Le lecteur doit laisser ses affaires dans des casiers avant de pénétrer dans la salle de lecture. Celle-ci comporte également quelques vitrines renfermant des médailles, des objets et autres témoins du prestige de l’Université. Ainsi, une telle salle de lecture associe à la fonction première de consultation (mise à disposition au lecteur) l’ «exposition» de ses documents.

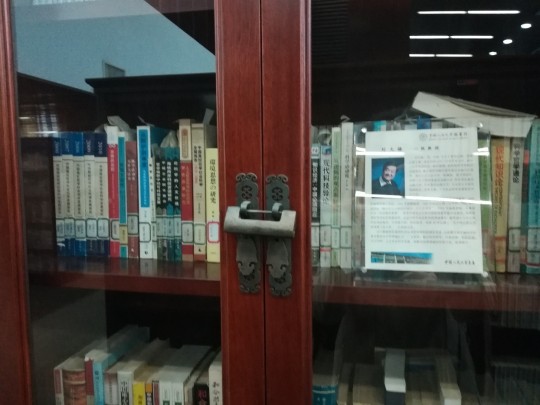

Les armoires mettent en valeur les œuvres de chercheurs issus de l’Université de Renmin dont des plaquettes exposent le parcours.

Revenons maintenant aux collections « anciennes, rares et/ou précieuses » et examinons quelques exemples de la mise en scène du patrimoine écrit au sein des bibliothèques chinoises que j’ai eu la chance de visiter. Je ne donnerai qu’un exemple pour ce qui concerne les fonds remarquables de la Bibliothèque Universitaire de Wuhan : il s’agit de la collection Nüshu donnée par le Professeur Gong Zhe Bing. Ces documents, qui ne se limitent pas, d’ailleurs, à des supports manuscrits, ainsi que le prouvent les photographies ci-dessous, proviennent de la province du Hunan et forment un témoignage exceptionnel de la mise au point par des communautés féminines d’un système d’écriture original et propice aux messages codés. Bien que sa naissance reste difficilement datable, l’écriture Nüshu semble avoir connu son apogée sous la dynastie des Qing (1644–1911). Aujourd’hui, le Nüshu apparaît comme un patrimoine en péril menacé par l’oubli et la mort des dernières femmes capables d’en maitriser le tracé mystérieux[8].

Les caractères Nüshu, dont les déliés sont parfaitement adaptés à la broderie, s’étalent sur des carnets aux couvertures en tissu, sur des objets (éventails, mouchoirs…) ou sur de petites feuilles. On distingue sur ces dernières les sceaux rouges des émettrices de ces messages (… secrets ?)

La salle dans laquelle sont conservés ces trésors renferme également quelques accessoires d’un film chinois dont l’intrigue se fonde sur l’héritage Nüshu et dont le titre anglais est Snowflower and the Secret Fan[9].

Néanmoins, la salle de la collection Nüshu n’est pas ouverte au public. Si la bibliothèque de Wuhan possède un petit espace muséal dans lequel sont présentés des catalogues manuscrits ou d’anciennes pièces de mobilier, celui-ci reste réduit et n’est pas prévu pour accueillir une exposition de grande ampleur. Je n’ai pas remarqué d’autre espace dédié à la présentation des livres anciens de la bibliothèque. En revanche, M. Wang Xincai, conservateur en chef, m’a parlé de certaines coopérations avec le Musée provincial du Hubei.

Petit « Library Museum » de l’Université de Wuhan dans l’angle de la salle de lecture A1

En revanche, il est possible de visiter une exposition sur l’histoire de l’Université dans le sous-sol de la Bibliothèque ancienne. Cette dernière, construite en 1935, ne remplit plus son rôle premier depuis la construction de la Main Library en 1985.

La Bibliothèque ancienne de l’Université de Wuhan, bibliothèque sans lecteur, bibliothèque-musée…muséifiée !

Elle sert en revanche d’écrin à des conférences et fait désormais figure de lieu de commémoration ou de prestige, ce dont atteste la présence de l’exposition. Celle-ci retrace à l’aide de panneaux la chronologie de l’Université de Wuhan et offre aux yeux des visiteurs quelques documents sous vitrines. Cependant, ces derniers ne sont pas des originaux mais des fac-similés.

Importance et dignité des fac-similés dans les bibliothèques chinoises

La présence de copies est une caractéristique récurrente des expositions d’ouvrages dans les bibliothèques que j’ai visitées. Le petit musée d’histoire du livre (Museum of Classic Books) qui occupe le cinquième étage de la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei ne présente que des fac-similés. Toutefois, lors de l’inauguration en décembre 2017, c’étaient bien les originaux que les visiteurs pouvaient admirer sous les vitrines ! [10]

Première salle du Museum of Classic Books de la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei

Salle de consultation de la Réserve des livres rares à la Bibliothèque nationale de Chine. Les armoires renferment les fac-similés, lesquels se retrouvent placés en regard des liseuses de microfilms

En outre, l’usage de fac-similés semble largement répandu chez les chercheurs en histoire du livre. À la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei comme à la Bibliothèque nationale à Beijing, une partie importante des salles de lecture des Réserves est occupée par les armoires renfermant les fac-similés d’ouvrages anciens. À ces copies imprimées s’ajoutent bien entendu les numérisations, notamment dans le cas des fonds Minguo[11], dont le papier est particulièrement acide : à la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei, la numérisation des ouvrages permet en même temps la réalisation de microfilms. La constitution de bibliothèques numériques et de bases de données d’images reste bien entendu un enjeu majeur. Des bornes permettent aux visiteurs d’accéder à des fac-similés numériques ou à des représentations d’objets en 3D.

Bornes proposant une sélection d’archives en divers styles calligraphiques aux lecteurs de la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei

Écrire, copier, décalquer le patrimoine

Mais ce n’est pas tout ! Les fac-similés recèlent des richesses inattendues : de copies ils peuvent eux-mêmes devenir modèles ! L’équipe du département Reference and Promotion de l’Université de Wuhan m’a parlé d’une activité dénommée WHU-ink and pen ripple : près de 2000 étudiants, à la suite du Conservateur en chef, ont participé à des copies à plusieurs mains d’ouvrages de la bibliothèque. Ceux-ci allaient du recueil épistolaire 84, Charing Cross Road d’Hélène Hanff aux analectes de Confucius. Certaines copies ont été effectuées au stylo bille sur de banals carnets. D’autres, réalisées à partir de fac-similés de livres anciens, ont été soigneusement calligraphiées sur des pages assemblées de manière traditionnelle.

Pages de la copie manuscrite réalisée lors de l’activité WHU-ink and pen ripple à partir d’un fac-similé conservé à la Réserve des livres rares (à droite). Il s’agit des œuvres de Lui Zongyuan, écrivain de la dynastie Tang (773-819). L’étiquette de la couverture du fac-similé porte les mots 唐柳先生外集 Tang Liu xiansheng waiji (« Supplément au recueil des œuvres complètes de Monsieur Tang Lui »[12])

S’il était besoin de le rappeler, les réalisations calligraphiques sont, en Chine, considérées comme des œuvres d’art à part entière. Cela implique parfois un statut ambigu des collections : ainsi, l’érudit et professeur Xu Xingke, dont la Bibliothèque provinciale du Hubei honore la mémoire dans un petit musée-mausolée, légua à celle-ci sa collection d’ouvrages mais réserva ses estampes et calligraphies au Musée de la province ! Or, la calligraphie a bien entendu toute sa place en bibliothèque, ce dont témoigne la création d’un espace singulier au sein de la salle des thèses et mémoires de la Main Library de WHU. Les lecteurs peuvent y manier le pinceau afin d’apaiser leur âme tourmentée par les affres de la recherche. Grâce à un papier spécial, il est possible de tracer les caractères avec de l’eau qui, une fois évaporée, laisse la page immaculée[13]. Littérature grise, geste artistique et pratique de l’écriture se combinent alors pour offrir aux étudiants une parenthèse ludique qui ne semble pas étrangère au concept de bibliothèque-troisième lieu.

Espace de calligraphie dans la salle des thèses et mémoires de la BU de Wuhan

Outre la calligraphie, l’exemple des stèles gravées questionne encore le statut ambigu du patrimoine écrit. La pierre capture le geste de l’écriture tout en sauvegardant la lettre des textes. Un musée tel que le Beilin Museum de Xi’an dont la « forêt des stèles » rassemble 3000 œuvres, fait figure de véritable bibliothèque lapidaire. À une échelle bien plus modeste, les actions menées par l’équipe des restauratrices de la Bibliothèque universitaire de Wuhan témoignent d’une conception étendue du devoir de préservation du patrimoine écrit. Des estampages traditionnels sont en effet réalisés dans le campus afin de décalquer le texte des stèles commémorant la fondation des bâtiments de l’Université. Le procédé repose sur une méthode stricte. Après avoir été plié en accordéon et humidifié, le papier est déployé à la surface de la pierre. On en chasse l’eau à l’aide d’un pinceau en fibres de palmier avant d’apposer l’encre de manière progressive grâce à des tampons sphériques en tissu. Sous les yeux étonnés de quelques passants qui craignent que le frottement des balles n’endommage les plaques -et que les restauratrices se chargent de rassurer-, les caractères émergent par contraste d’un arrière-plan minutieusement noirci. Le martèlement du « copiste-estampeur » fait réapparaître sur le papier le geste sous-jacent à l’écriture, réactualise le tracé dont la pierre se faisait le témoin. Et c’est à cette re-naissance des mots, qui ne laisserait aucun(e) archiviste paléographe indifférent(e) que j’ai eu la chance de participer.

Notes

Et ce depuis une expérience décevante ayant impliqué une entreprise tierce…

LIAO (Jing), “A historical perspective: the root cause of the underdevelopment of user services in Chinese academic libraries”, in The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 30 : 2, 2004, p. 109-115.

Voir la synthèse bibliographique de JIAO (Shuqin), ZHUO (Fu), ZHOU (Liming) et ZHOU (Xiaoying), “Chinese academic libraries from the perspective of international students studying in China”, in The International Information & Library Review, 41:1, 2009, p. 1-11 [en ligne : <https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2009.10762792 >]

Afin de donner à notre lecteur un ordre de grandeur, la plupart du temps, le prix d’un livre chinois, dont la couverture est souvent brochée, reste très largement inférieur à 100 RMB (soit 13 euros environ). Le transport des ouvrages occidentaux contribue bien entendu à accroitre les frais

À la Main Library de Wuhan University, l’espace des Preserved books (à ne pas confondre, bien entendu, avec la Réserve des livres rares !) correspond aux salles de lecture C, par opposition à la Circulation area dont les exemplaires sont empruntables sur la longue durée (salles de lectures A)

Dans cette même bibliothèque, les collections de l’aire C ne sont empruntables que pour une durée de 7 jours tandis que celles de l’espace A peuvent être conservées un mois, voire davantage. D’autre part, les élèves doivent laisser leurs effets personnels à l’entrée de la « Preserved area », ce qui n’est pas le cas lorsqu’ils travaillent dans la « Circulation area »

Du moins selon les enseignements tirés d’une précédente expérience de stage en bibliothèque universitaire de médecine, dont les annales de PACES se caractérisaient par une durée de vie assez limitée…

Sur les écritures Nüshu, voir par exemple le site internet mis au point par Orie Endo, professeur de socio-linguistique à Bunkyo University au Japon [< http://nushu.world.coocan.jp/>] et celui, en français, de Martine Saussure-Young qui les avaient étudiées dans le cadre de ses mémoires de Master à l’INALCO [<http://www.nushu.fr/>] (liens vérifiés le 05/12/2018)

Snowflower and the Secret Fan de Wayne Wang (2011) avec Gianna Jun, Li Bingbing, Archie Kao, Vivian Wu et Hugh Jackman. Le film, dont on pourra consulter la fiche à l’adresse suivante [<http://www.allocine.fr/film/fichefilm_gen_cfilm=174938.html>] est l’adaptation de l’ouvrage éponyme de l’auteure américaine Lisa See (2005)

Voir l’article du journal Changjiang weekly en date du 5 janvier 2018 : « Hubei Museum of Classic Books opens » [en ligne : <http://cjweek.cjn.cn/images/2018-01/05/12/12.pdf>, lien vérifié le 06/12/2018]

Période succédant à l’effondrement du régime impérial et précédant l’avènement de la République populaire de Chine, soit 1912-1949

Je remercie Adrien Dupuis pour la transcription et la traduction !

Cette pratique n’est pas sans rappeler la calligraphie « Dishu » qui consiste à tracer avec de l’eau des caractères éphémères en milieu urbain !

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Blue and white pottery(在 Hubei Provincial Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/CY8pi5KrArU/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

致敬舍身救人的医务工作者(在 Hubei Provincial Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/CUHo3oxl00V/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

Hanfu Relics:

1.绿罗织金凤纹袍/Green Luo Weave Gold Phoenix Gown,Collection of Shandong Museum

2. 暗绿地织金纱云肩翔凤短衫,Confucius Museum

Chinese Ming Dynasty Painting attributed to Tang Yin(唐寅)

Chinese Ming Dynasty Hair Accessories Relics:

1. 火焰纹金顶簪/Gold hairpin with flame pattern,Nanjing Municipal Museum

2. 蓮花紋金挑心/Lotus pattern gold hairpin,Nanjing Municipal Museum

3. 金凤簪/golden phoenix hairpin,Hubei Provincial Museum

Chinese Ming Dynasty Portrait(hairstyle reference):

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Photoshoot References to Ming Dynasty Relics

————————

Planning and production: @成都临溪摄影

🧚🏻♀️Model: @木景抒

📸Photo: 逮逮

💄Makeup∶ 百丽

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1648616372/Mf8kCAh9C

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD)#chinese traditional clothing#chinese fashion history#China History#hanfu artifacts#chinese#historical fashion#Chinese Costume#Chinese Culture#hanfu history#hanfu art#hanfu#hanfu accessories#chinese fashion#china#漢服#汉服

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bird, Tiger, Serpents and a Pair of Antlers: Warring States Art Device

Another remarkable sur of the pre-Taoist period.

The sculptural group is dominated by a mighty Bird, whose wings are complemented by antlers. Some have rashly classified it as the Phoenix, according to another version it is a Crane. However, I would warn against light-minded ornithological typing. The thumbnail Tiger serves as a pedestal for the Bird, pressing two serpentine bodies with its paws. The coiled snakes are devouring a pair of fliers.

The artifact may turn out to be a drum stand common at the time. Other figurines of antlered birds standing on tigers are known. This common motif unites the spiritual animals of the Lower and Upper Worlds. The amalgamous zoomorphic imagery is probably of shamanic origin.

Antlered and winged beings were also a widespread pattern in depiction of the zhenmushou (鎮墓獸), tomb guardians. The solemn or ferocious creatures served as the owner's spiritual animals in the afterlife and guides on the ascent to Heavens.

The entire lacquered wood sculpture group is painted black with subtle gold and red ornamentation. The object was unearthed from the Tomb No. 1 in Jiuliandun (九連墩1號墓), Zaoyang, Hubei. Now it is in Hubei Provincial Museum (湖北省族館).

Photo: ©湖北省族館

#ancient china#chinese culture#chinese mythology#chinese art#warring states era#warring states period#tomb art#ancient tomb#zhenmushou#zoomorphic#spiritual animal#totem pole#totem#bird art#bird#Phoenix#tiger#lacquer#lacquerware#burial#sculpture#statues#wooden sculpture#surrealism#surreal art#animal figurine

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the Hubei Provincial Museum, located in Hubei Province in eastern central China, a perfectly preserved bronze sword from the Fifth century BC is displayed among the permanent collections.

The sword was discovered in 1965 during an archaeological excavation at the Zhang River Reservoir in Jingzhou. Nearly fifty tombs were found, yielding over 2,000 artifacts, among them the Sword of Goujian.

The weapon is 22 inches long with a repeating dark-colored pattern of rhombi engraved into the blade and is inlaid with turquoise.

https://www.thevintagenews.com/2019/02/22/goujian/

I really like this sword’s design because of the colours and blade design. I really like the engravings on the blade and how they are coloured to contrast the colour of the non engraved areas. While I do like the design not having a cross guard handle, I think it would have looked better with one.

I would use a design similar to this for my sword but I won’t show a lot of the blade in the way I would like to display it.

0 notes

Text

Wacth As A Museum In China Put Up Africans Alongside Animals For Exhibition

On exhibit at the Hubei Provincial Museum is a photo series meant to celebrate the harmony between man and nature, as captured by a photographer and businessman during his travels to Africa over the past decade. The exhibition,

“This is Africa,” includes the typical shots of elephants, cheetahs, and sunsets over the savanna, but makes one crucial miscalculation. A section titled, “One’s heart makes one’s appearance” features portraits of African children and adults next to animals.

In one, a photo of an elderly man is placed next to that of a monkey. In another, the image of a young African man looking over his shoulder sits next to a photo of a cheetah in the same pose. A child with an open mouth is placed next to a gorilla. Among photos of the exhibit circulating African student groups in China is one of Chinese children posing underneath the image, making similar expressions. The student who shared the photos asked not to be named for fear of being targeted by immigration officials.

After receiving complaints from the African community, the museum removed the photos. African students complained to their university deans while others petitioned their embassies, according to students and professionals in these circles. The exhibit has been on display since late last month in honor of China’s eight-day National Day holiday when the museum received some 133,000 (link in Chinese) visitors.

“It’s not shocking. Africans are not strangers to racism here in China or elsewhere. But it is sad that despite deepening economic connections and interactions between Chinese and Africans, there’s still clearly so much racism and lack of cultural understanding,” says Zahra Baitie, a Ghanaian master’s student at Tsinghua University studying global affairs.

In a statement sent to Quartz today (Oct. 13), the exhibit’s planner Wang Yuejun said “the museum fully understands” the complaints. He also tried to justify what he sees as a cultural misunderstanding. “The exhibit’s main audience is Chinese. In the Chinese esthetic, comparing people to animals is not offensive,” he said.

Wang pointed that the Chinese have worshiped animal totems and that in the Chinese zodiac system, one’s birth year is associated with an animal. Defending the photographer’s decision to compare the facial features of animals with that of humans, he said. “It’s to remind people that we shouldn’t forget where we come from.”

The photographer, Yu Huiping who is also the chairman of a local construction company, has previously said the goal of his work is to explore the connections between nature and man. Reflecting on his visits to Africa, he told Chinese media ahead of the exhibit’s opening, “I often wonder, how do we build an order and balance the ecology system between human and nature? I think, record, explore, and communicate with the unique perspective and sensitivity of a photographer.”

This isn’t the first time that racism towards Africans has reared its head in China.

WeChat apologized earlier this week after users discovered the app’s translation for hei laowai, or “black foreigner,” into English was “nigger.” Last year, Qiaobi, a home care company famously ran a television ad in which a black man put into a washing machine comes out Asian, thanks to Qiaobi’s extra strong detergent.

Not everyone believes the exhibit should be taken so seriously. Sam Haguru, a teacher who tried to go see the exhibit after the photos had already been taken down, says that while he disagreed with the exhibit, it shouldn’t color people’s perceptions of the entire country.

“China is a great country and an individual’s mistake should not be used to castigate the whole of China. China remains a second home to me,” he says. “Personally, I have been treated with respect and love by the Chinese people whom I have met.”

Read the full article

0 notes