#I took a history in spring a history in fall and now a political science class… IM TIRED OF FHIS INFORMATION

Text

I forgot how hard it is to do homework when I could be drawing toby

#I literally don’t CARE ABOUT THE CONSTITUTION#I took a history in spring a history in fall and now a political science class… IM TIRED OF FHIS INFORMATION#chatterbox#summer not fall idk why I said fall…

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republicans clueless as to why they don't have the youth vote . . .

climate protection

reproductive health

student debt

gun safety

affordable healthcare

LGBTQ+ rights

interracial marriage

contraception

voting rights

marijuana

money in politics

police standards

workers’ rights

teaching accurate history, science and biology

strong public schools

support of teachers

immigration issues

* * * *

The Summer of Climate Collapse

[That's Another Fine Mess :: TCinLA]

Fifty years ago, I decided that a Master of Public Administration degree would be useful in my expected career in government. In 1975, I obtained on of the first MPA degrees in the field of “Environmental Management.”

One of the books we read was “The Limits to Growth,” published by the Club of Rome, which detailed current enviornmental problems and forecast where they would be in 30 years of no action was taken, some action was taken, or effective action was taken. I rediscovered that book in a box in my garage 25 years ago and re-read it with the benefit of hindsight, since their 30 year period had just ended. In every case, no action had been taken, and in every case the current situation had been accurately forecast by the contributors to the book.

In 1967, historian Lynn White Jr.'s prescient "The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis" was published in "Science" magazine. His thesis was:

"In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns, and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated. By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects."

Perhaps it’s fitting that during this summer of climate collapse - and if you think it’s something other than that, consider that June was Earth’s hottest month on record since the Permian Collapse - the event that brought on the Age of Dinosaurs after killing off 70% ofr species in the ocean and 80% of those on land - until the end of this month when the record will be broken by July, a record that will likely last another 31 days to the end of August. The atmosphere is warmer now than it’s been in 125,000 years, when our species was a few thousand individuals living a precarious existence on the edge of extinction in what is now South Africa .

That we are all transfixed not by this news but rather by the prospect of the United States falling to the machinations of a tenth-rate failed circus clown demonstrates the problem.

The initial success of Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” suggests Hollywood is finally ready to portray the American development and use of atomic weapons during World War II as something other than an absolute necessity. Unlike past movies, Nolan’s film points out that J. Robert Oppenheimer and many of his contemporaries knew they were ushering in an era where eradicating civilization had never been so easy

The parallels to climate change may not be obvious to people who don’t sit around pondering the end of the world, but I see them. Both climate change and ever-looming nuclear catastrophe are willful human creations driven by “progress” - one by scientific theory and research turbocharged by limitless wartime government resources, the other by oil-fueled industrialization. Both rationalized as necessary evils; climate change as a consequence of endless convenience for the human species, and nukes as guarantor of fragile world peace via “mutual assured destruction.”

It only took nearly 80 years to get to the point that National Mythology can be questioned in a commercially-successful film In all the time scientists have tried to focus our attention on climate change, they’ve had nothing as visually arresting as a single bomb instantly wiping out a city.

That has changed this summer.

We now have a global heat wave few could have envisioned even ten years ago, while the fossil fuel companies driving this destruction are coming off a year of record profits.

I wonder how this will be portrayed on screen 80 years from now.

The World Meteorological Organization expects temperatures in North America, Asia, North Africa and the Mediterranean to be above 40 Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) "for a prolonged number of days this summer." It also expects more frequent heatwaves, spread across the seasons.

The ocean around Florida hit a record temperature of 101 degrees this week. Warm water like that will produce a hurricane that could wipe Miami off the map, the equivalent of a nuclear bomb.

While the Southwest swelters under a heat dome, Vermont saw its second 100-year rainstorm in roughly a decade. Early July brought the hottest day globally since records began, a milestone surpassed the following day. Yesterday there was flooding across the northeast from Wisconsin to Maine.

As these temperature and weather records fall, Earth may be nearing so-called tipping points. A “tipping point” is where incremental steps along the same trajectory could push Earth’s systems into abrupt or irreversible change, leading to transformations that cannot be stopped even if emissions were suddenly halted.

If these tipping points are passed, some effects such as permafrost thawing or the world’s coral reefs dying - both are already happening in Siberia and the Central Pacific - will happen more quickly than expected. We don’t really know when or how fast things will fall apart.

Some natural systems, if upended, could herald a restructuring of the world. Take the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica: It’s about the size of Florida, with a protruding ice shelf impeding the glacier’s flow into the ocean. Although the overall melt is slower than originally predicted, warm water is eating away at it from below, causing deep cracks. At a certain point, that melt may progress to become self-sustaining, which would guarantee the glacier’s eventual collapse. That will affect how much sea levels will rise; 80% of humans live near the ocean.

When melt from Greenland’s glaciers enters the ocean, it alters an important system of currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. The AMOC is a conveyor belt, drawing warm water from the tropics north. The water’s salinity increases as it evaporates, which, among other factors, makes it sink and return south along the ocean floor. As more glacial fresh water enters the system, that conveyor belt will weaken. Right now it’s the weakest it’s been in more than 1,000 years.

The Atlantic Ocean’s sensitive circulation system has become slower and less resilient, according to a new analysis of 150 years of temperature data — raising the possibility that this crucial element of the climate system could collapse within the next few decades.

Consider that: Paris and London are at the same latitude as Hudson’s Bay, yet Europe has the climate it does because of the AMOC - we commonly call it the Gulf Stream - which brings warm water in contact with cold air, resulting in the clouds and rain that provide for all living things there. If that collapses, life in Europe could soon resemble that of northern Canada. Right now, Europe can grow enough food to feed its 740+ million people; if the AMOC was to die, the continent could be plunged into famine in a matter of years.

The study published this last Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications suggests that continued warming will push the AMOC over its “tipping point” around 2050-2080. The shift would be as abrupt and irreversible as turning off a light switch, and it could lead to dramatic changes in weather on both sides of the Atlantic, leading to a drop in temperatures in northern Europe and elevated warming in the tropics, as well as stronger storms on the east coast of North America.

If the temperature of the sea surface changes, precipitation over the Amazon might too, contributing to deforestation, which in turn is linked to snowfall on the Tibetan plateau.

A new study published in Nature Communications last week titled “Warning of a Forthcoming Collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation” reports global warming forced by all the CO2 and methane in our atmosphere - if we action is not taken immediately - could shut down the AMOC as early as 2025 and almost certainly before 2095.

We may not even realize when we start passing points of no return—or if we already have.

James Hansen, one of the early voices on climate and the founder of 350.org, says measures to mitigate the crisis may ironically now contribute to it. A working paper he published this spring suggests that reduction in sulfate aerosol particles—the air pollution associated with burning coal and the global shipping industry—has contributed to warmer temperatures because these particles cause water droplets to multiply, brightening clouds and reflecting solar heat away from the planet’s surface. Hansen predicts that environmentally minded policies to reduce these pollutants will likely cause temperatures to rise 2 degrees Celsius by 2050.

This adds to a growing body of alarming climate science, like the one published last year in the Journal of Climate titled “Sixfold Increase in Historical Northern Hemisphere Concurrent Large Heatwaves Driven by Warming and Changing Atmospheric Circulations,” which indicates we’re much farther down the path of dangerous climate change than even most scientists realized.

That study essentially predicted this year’s shocking Northern Hemisphere heat waves. The lead researcher’s first name is Cassandra.

Perhaps most alarming was a paper published eleven months ago in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) titled “Evidence for Massive Methane Hydrate Destabilization During the Penultimate Interglacial Warming.”

It brings up the topic of the “Clathrate Gun Hypothesis,”which is the absolute worst case scenario for humanity’s future.

Across the planet there are an estimated 1.4 trillion tons of methane gas frozen into a snowcone-like slurry called clathrates or methane hydrates laying on the sea floor off the various continents. When they suddenly melt, that’s the “firing of the gun.” An explosion - in the context of geologic time - of atmospheric gas that’s over 70 times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2. The Clathrate Gun.

The PNAS paper mentioned above concludes that 126,000 years ago there was an event that caused a small amount of these clathrates to warm enough to turn to gas and bubble up out of the seas. The resulting spike in methane gas led to a major warming event worldwide:

“Our results identify an exceptionally large warming of the equatorial Atlantic intermediate waters and strong evidence of methane release and oxidation almost certainly due to massive methane hydrate destabilization during the early part of the penultimate warm episode (126,000 to 125,000 y ago). This major warming was caused by … a brief episode of meltwater-induced weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) and amplified by a warm mean climate.”

The researchers warn we may be looking at a similar event in our time:

“This week, sea surface temperatures along the coasts of Southern Spain and North Africa were 2-4C (3.6-7.2F) higher than they would normally be at this time of year, with some spots 5C (9F) above the long-term average.”

This has never happened before while humans have existed.

The least likely but most dangerous outcome scenario is that the warming ocean might begin a massive melting of those methane hydrate slurries into gas, producing a “burp” of that greenhouse gas into the atmosphere, further adding to global warming, which would then melt even more of the clathrates.

At the end of the Permian, 250 million years ago, this runaway process led to such a violent warming of the planet that it killed over 90 percent of all life in the oceans and 70 percent of all life on land, paving the way for the rise of the dinosaurs, as cold-blooded lizards were among the few survivors. That period is referred to as the Permian Mass Extinction, or, simply, “The Great Dying.” It was the most destructive mass extinction event in Earth’s history.

As the scientists writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences noted:

“The key findings of our study add to a growing body of observational findings strongly supporting the ‘clathrate gun hypothesis.’ … Importantly, the interval we have studied is marked by a mean climate state comparable to future projections of transient global climate warming of 1.3 °C to 3.0 °C.”

We just this year passed 1.3 degrees Celsius of planetary warming: we are now in the territory of the Clathrate Gun Hypothesis if these researchers are right

The last time our planet saw CO2 levels at their current 422 parts-per-million, sea levels were 60 feet higher and forests grew in Antarctica.

Meanwhile, we’re pouring more CO2 into the atmosphere right now than at any time in human history.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Vatican’s Secret Role in the Science of IVF

On a spring day in Rome, 1957—the season of Pope Pius XII’s Ash Wednesday Mass, wisteria blooming by the Spanish Steps—30-year-old Bruno Lunenfeld gave one hell of a presentation.

What he said had the potential to shape the course of history in ways even the Vatican couldn’t foresee.

Inside an imposing L-shaped building that stretched down Via Casilina and then along Via L’Aquila, in a wood-paneled library distinguished by rows of leather-bound books and cream floor tiles spangled with stars, the dozen or so board members of a pharmaceutical company listened as Lunenfeld described his findings.

For four years he had been developing a therapy that would induce ovulation in women struggling with infertility.

What he needed now was the support of the Istituto Farmacologico Serono, whose own staff scientist, Piero Donini, had been working on a similar endeavor, and who had facilitated Lunenfeld’s trip from Israel to Rome.

The men listened politely, but at the end of the presentation they told him, with regret, that they couldn’t help.

They believed certain hurdles to be insurmountable.

It seemed unlikely, for instance, that Serono would be able to procure the vast quantities of one specific essential substance without which the drug couldn’t be made.

Lunenfeld left the library.

Nearly 70 years later, looking back, he won’t be able to remember whether or not he was crying.

What he does recall is that a member of the board by the name of Don Giulio Pacelli—pictures will show the Italian prince to have had the strong features and thick dark hair, receding sharply at the temples, of a Fellini heartthrob—approached him in his despair.

Lunenfeld wasn’t Italian or Catholic.

He didn’t realize the currency of Pacelli’s name in a city like Rome and certainly couldn’t have understood his connection to the pope.

Still, the prince had something else to offer, equally potent and instantly recognizable: belief.

“I have an idea,” he said to Lunenfeld. “Let’s talk.”

30,000 LITERS

“I will tell you exactly the number of nuns we needed for the initial phase,” Lunenfeld says to me.

The 96-year-old endocrinologist is calling from his home on the Florida coast, in Delray Beach, just a short drive from Boca Raton.

He can’t immediately find the figure in his files but, he assures me, he knows he has it somewhere.

I tell him I recall reading that it was 300 nuns.

“Could be, could be,” he says patiently.

Then he locates the slide he was looking for.

“No, I think we only had a hundred nuns.”

Later, that number would expand, but over the first year, he says, “we had a hundred nuns recruited, which gave us 30,000 liters, and the 30,000 liters gave us a hundred milligrams of the substance which we needed. And this was enough to make 9,000 vials of 75 units, sufficient for 450 ovulation induction cycles.”

What Lunenfeld is explaining is that it took 100 postmenopausal nuns one year to produce 30,000 liters of piss.

All that urine, collected and processed by Serono, eventually helped create the drug Pergonal, which aided in the first successful IVF pregnancy in the United States, as well as countless pregnancies, in vitro and otherwise, worldwide.

And in certain ways still does.

Serono phased out Pergonal in 2004.

Later that year, the nearly identical brand-name competitor, Menopur, gained approval for use in the US and remains a leading IVF drug today.

In 2022 Menopur turned $802 million in global sales for Swiss-owned Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

That fall, “changes made in the manufacturing process” of Menopur’s ingredients caused a yearlong global shortage, sending patients scrambling to internet pharmacies and online message boards, desperately searching for vials of the drug.

For now, the supply chain has unkinked—at least, as long as IVF is legal.

In February, Alabama’s Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos are people, with a concurring opinion by Chief Justice Tom Parker that quoted scripture.

To continue IVF while complying with such a ruling would set assisted reproductive technology back decades.

But the ruling is just the latest potential roadblock for a substance that, as Lunenfeld has described it, turned “urine into gold”—on a road dotted, at every turn, with disparate and powerful men.

A thing nobody tells you about trying to get pregnant is all the pee.

There is, of course, the ubiquitous at-home pregnancy test.

If it detects the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin, which the body begins producing shortly after implantation and is excreted in urine, the test flashes a smiley face or darkens a line, the happily ever after of the conception “journey.”

But if you don’t get pregnant the first time you glance unprotected at a penis—as some sixth-grade health classes may lead you to believe—you might purchase an ovulation predictor kit.

The cheapest version of these are small test strips which, when dipped into urine, measure the body’s levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), a rise in which triggers ovulation.

If you purchase a 50-pack on your cell phone late one night, your social media algorithm may start serving you alternative methods of pregnancy prediction, like the scientifically unfounded sugar test (pee on sugar crystals and read them like tea leaves, approximately $5) or more advanced tech, like the Mira, Inito, or Oova, to catch the fertile window by tracking LH, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and more (pee on dipsticks and insert them into a digital device, $150 and up).

Your acupuncturist might suggest the Dutch Urine Test, a $499 panel “that provide[s] a complete evaluation of sex and adrenal hormones.”

The instructions before a pelvic ultrasound will be to drink 32 ounces of water one hour prior, because a full bladder will help reposition the bowels for a clear view of the uterus, but after the external exam the tech will send you to the bathroom to urinate because the intravaginal imaging requires an empty bladder.

On the TryingForABaby Subreddit, a refrain: “Pee on everything!”

THE G CLUB

Bruno Lunenfeld was born in 1927 to a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna; his father, David, was a lawyer whose office represented the House of Habsburg, a fierce opponent of Nazism.

As Adolf Hitler’s influence grew throughout the ’30s, David began making plans for his family to escape the country, only to be detained by Nazi forces.

In 1938, Bruno, a round-faced 11-year-old with wide, inquisitive blue eyes, joined a Kindertransport bound for England.

(He would later learn that Nazi soldiers forced his father and uncle onto a Dachau-bound transport train, and that his uncle was shot and killed en route, while his father was later moved from Dachau to Buchenwald.)

While at a camp in Dovercourt waiting to be placed with a British foster family, Lunenfeld took 10 British pounds secreted into his sock by his mother, bought his own ticket to London, and found a policeman who eventually united him with an uncle living nearby.

He attended various local boarding schools until 1940, when members of the French military reunited him with his parents, who had escaped to Mandatory Palestine—“It was not Israel” at that point, Lunenfeld says—though he never understood how.

At school in Tel Aviv, Lunenfeld struggled to learn Hebrew, having been raised on German and then English.

Following the Italian Air Force’s bombing of the city in September 1940, his parents enrolled him at St. George’s, a British boarding school in Jerusalem.

Lunenfeld became interested in studying medicine after a close friend died of polio, but Israel had no medical school.

He ultimately earned his MD and PhD at the University of Geneva—where, he notes ruefully, he worked in French.

For his doctorate in endocrinology, Lunenfeld studied under Hubert de Watteville and Rudi Borth, who were working with the Swiss pharmaceutical firm CIBA to test an oral drug designed to ease the symptoms of menopause.

During clinical trials on patients experiencing vaginal dryness, hot flashes, and brain fog, Lunenfeld and Borth began experimenting with the patients’ urine, injecting small amounts into immature mice.

(Scientists already knew that urine contained hormones; in one early pregnancy test, developed in the 1930s, doctors injected rabbits with women’s urine, then killed and dissected the animals to examine their ovaries, which developed growths in response to pregnancy hormones.)

Lunenfeld, Borth, and de Watteville hoped that the menopausal urine might hold answers to what caused the unpleasant symptoms.

Instead, the injections caused the mice to ovulate and even “hyperovulate,” in which ovarian follicles develop into not one but multiple mature eggs.

Equally surprising was that after Lunenfeld treated the same menopausal women with a 90-day course of CIBA’s drug, which contained estrogen and testosterone, the women’s urine stopped the mice from becoming fertile.

Lunenfeld and his professors hadn’t simply stumbled upon a potential treatment for women experiencing amenorrhea—a lack of menstruation that can mean they’re not ovulating—they had discovered a contraceptive too.

At the time, the research had limited funds, provided by the Swiss government.

“We had to decide, are we going into the direction of contraception, or are we going in the direction of infertility?” Lunenfeld says. “I was biased, of course. This was just after the war, and so many people got killed. So I thought, Maybe the better thing now is to go into infertility and help women who couldn’t have babies, to have babies.”

But Lunenfeld, Borth, and de Watteville couldn’t simply begin injecting would-be mothers with human waste.

“We had to test biological studies, biochemical studies, biostatistical studies, and so on,” Lunenfeld recalls.

They didn’t have the knowledge or manpower.

At the time, Lunenfeld had just finished consulting on a film for Hoffmann-LaRoche (now known as Roche AG, one of the biggest public pharmaceutical companies in the world).

The producer was a German refugee who’d caught the last train into Switzerland.

Over dinner at a Geneva train station with de Watteville and the producer, Lunenfeld listed the five people in the world who could help them.

The producer made him a bet:

That night Lunenfeld would send five telegrams, inviting them to Geneva.

If they accepted, de Watteville would pay for their travel and accommodations.

If they declined, the producer would buy him two cases of his favorite wine—Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

By the end of the next day, Lunenfeld had received affirmative responses from all but one.

“The guy from Scotland,” Lunenfeld says, “sent it by post.”

In the summer of 1953, Lunenfeld and his adviser had convened a murderers’ row of endocrinologists, chemists, biologists, and others to develop standards, assay procedures, and purification methods for this miracle substance extracted from the urine of postmenopausal women.

What to call it?

The summit landed on “human menopausal gonadotropin,” or hMG. And they decided to call themselves the G Club.

“ALL THE URINE IN THE WORLD”

Nearly three decades prior to Lunenfeld’s research, scientists had discovered gonadotropins, a family of peptide hormones that control ovarian and testicular functioning.

They extracted these hormones from the blood of pregnant horses (dubbed Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin), which could stimulate ovulation in humans when injected.

But women treated with these gonadotropins also formed neutralizing antibodies.

The urine-derived hMG, which contained a naturally occurring combination of FSH and LH, had no such limiting side effect.

In a 2004 issue of the Human Reproductive Update journal, Lunenfeld described the production of hMG as “a relatively simple procedure.”

A chemist mixes menopausal urine with activated kaolin clay—shaken, not stirred.

“The suspension is left to settle at room temperature and then centrifuged.”

Liquid is discarded, kaolin is eluted, proteins are washed, acidified, precipitated, filtered, and treated.

It wasn’t the method of purification but the means of collection that proved challenging.

The average adult produces somewhere around 2 liters of urine per day.

“It takes about a day’s supply of urine from 10 women in order to produce a single therapeutic dose,” Lunenfeld told the Silicon Valley–founded nonprofit Israel 21C in 2012—in other words, one New York City water tower’s worth would be needed to run clinical trials.

To present his findings to Serono that spring day in 1957, the company had agreed to put Lunenfeld up for three nights in a “very nice hotel, a beautiful little thing” owned by the sister of someone in Serono management.

But the discussions between Lunenfeld, Prince Pacelli, and Serono’s chemist Piero Donini required more runway.

For nearly two weeks, Pacelli “took care of everything,” Lunenfeld says, extending his hotel stay with “full board for me.”

Lunenfeld remembers the prince as broad-minded and widely studied.

By day the men talked logistics; in the evening, Lunenfeld joined Donini at his home for dinner presided over by a white-gloved servant.

The head of Serono, Pietro Bertarelli, and his son Fabio (who would become CEO in 1965) were also present for discussions.

A fanciful booklet that Serono produced in 1996, provided by the Merck archive, paints the story of seven people sitting around a table discussing the logistics of the proposed project.

“I need the urine of thousands of menopausal ladies,” an anonymous interlocutor says. “We can collect urine, we will collect urine, we need to collect urine…I need all the urine in the world!”

“There could be no contamination of pregnancy,” Lunenfeld tells me.

The introduction of hormones from even one pregnant person would ruin the batch.

In the immortal words of Mel Brooks: Send in the nuns!

We won’t be hearing from these women, the linchpins to this story.

Details on their exact location and order are lost to the maw of time—or perhaps buried as a line item in the Vatican archives.

(The Vatican did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

Given their already advanced age at the time of Serono’s collection, it’s safe to say that none are alive today and few, if any, are likely to have direct familial descendants.

A representative from Merck Serono declined to answer questions about the women, citing a lack of documentation.

Lunenfeld never met them.

“Nuns present a special case in terms of memory and representation, since often their beliefs cause them to shy away from both,” writes Flora Derounian, a lecturer at the University of Sussex.

Her 2023 book Women’s Work in Post-War Italy includes oral histories of nuns who lived in beautiful apostolic “mother houses” in Rome between 1945 and 1965, two of which functioned as retirement homes, where young novitiates cared for elderly sisters—likely a similar arrangement to the casa di riposo that Serono ended up tapping.

Most would have entered the convent at age 18, having relinquished their given names and taken vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

They slept in single rooms with a bed and a desk, ate simple meals, fasted on Fridays.

They lived regimented days, focused on obedience to the Mother Superior and guided by the tolling of bells.

On a call, Derounian describes the communal wardrobes the women shared, from their black and white habits—some of which included a cornette, an elaborate veil “pointed almost like an admiral’s hat”—down to socks and undergarments.

“Their individuality was subsumed in the congregation,” says Kathleen Sprows Cummings, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who oversees the History of Women Religious, an academic organization devoted to the study of Catholic sisters.

Even so-called “particular attachments” between nuns were discouraged.

In exchange, Sprows Cummings says, they received a path to education and protection from unhappy marriages, divorce, and death by childbirth.

“Not only were they not pregnant, but would have never been pregnant—the vast majority of them, if not all of them.”

Serono’s donors may have dwelled in the quiet halls of a contemplative convent, which emphasized prayer, or an apostolic one, whose sisters served in such roles as teachers, nurses, or seamstresses.

Some made products: herbal medicines, biscuits.

Others, in Rome, cleaned and cooked at the Vatican.

The very elderly of all orders spent much of their time murmuring prayers.

“The structure of convent life would’ve been, at that point, essentially unchanged for centuries,” says Sprows Cummings—and the convents, she says, “were bursting,” their numbers nearing an all-time high.

If the nuns in 1958 were informed of their new ministry, “at a time when everything was on the verge of changing, with the birth control pill,” they might have seen it as “a way to cement the Catholic teaching about how important it is to be open to babies, and to have as many babies as possible.”

According to Lunenfeld, the nuns were Pacelli’s “fantastic” idea.

After days of mulling over logistics—and behind-the-scenes talks to which Lunenfeld was not privy—the prince took the proposal back to the Serono board, joined by Lunenfeld.

“He presented the project to them. And then he said, ‘The pope is interested.’ ”

IL NIPOTISMO

At 5:30 p.m. on March 2, 1939, a puff of white smoke appeared from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel—and then promptly turned black.

Confusion reigned until, according to Inside the Vatican magazine, the secretary of the conclave sent a note to Vatican Radio that regardless of what color the smoke appeared to be, it was white.

The cardinals had elected an inside man, the first Roman pope since the 18th century. Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli took his papal name, Pope Pius XII, on his 63rd birthday.

The Pacellis—Don Giulio included—were members of the black nobility, aristocratic families with titles granted by the Church and deep loyalty to the papacy.

Eugenio’s grandfather, Marcantonio, had served as minister of foreign affairs under Pope Pius IX and in 1861 founded the Vatican newspaper, Osservatore Romano;

Eugenio’s uncle Ernesto had founded the Banco di Roma in 1880.

And in 1929 his elder brother, Francesco, a legal adviser to Pope Pius XI, had negotiated the Lateran Treaty with Benito Mussolini, which granted Vatican City sovereign independence.

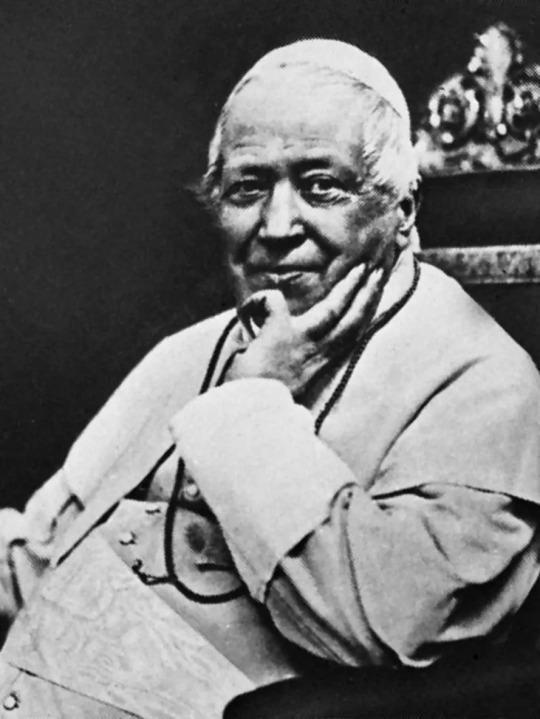

Pius XII had a serious look to him, owllike, with dark eyes made larger behind wire-rimmed glasses.

His pale skin, as correspondent Corrado Pallenberg put it in his 1960 book, Inside the Vatican, “resembled old parchment, yet at the same time it had the surprisingly transparent effect, as if reflecting from the inside a cold, white flame.”

Pius XII had served as an ecclesiastical ambassador to Germany under his predecessor and was widely believed to have been elected due to his experience in diplomacy.

A few days after his election, Pius received a congratulatory telegraph from Hitler.

“A rather cold and uncommunicative person,” Pallenberg wrote of Pius, “he did not feel at ease in the Vatican world, 95 percent of which consisted of easygoing, jovial Italians who enjoyed good food, amusing talk and a bit of gossip.”

As a boy, one of Pius XII’s favorite games had been pretending to give Mass.

He surrounded himself with a group of confidants that included his personal doctors; the Bavarian nun, Mother Pascalina Lehnert, his housekeeper for more than 40 years; and, after Francesco died, his brother’s adult sons.

Plenty of popes kept family close.

The word nepotism stems from Gregorio Leti’s 1667 book Il Nipotismo di Roma, or The History of the Popes’ Nephews, an often-ribald account of the Renaissance-era golden age of popes granting wealth, titles, and special privileges to their relatives.

(Some of whom were whispered to be secret sons of the popes themselves, as in the case of Alexander VI, “a barbarous, lascivious Pope” who took “great delight to be embraced and caress’d by fair Ladies; whence the numbers of his Bastards was very great.”)

Of Pius’s nephews, Carlo, the eldest, was regarded as the favorite.

He alone, wrote Pallenberg, had access to the pope’s apartment for private meetings.

But all enjoyed privileges, some of which began even before their uncle became the Lord’s earthly shepherd.

Marcantonio, the middle brother, presided over a flour mill, a sink and toilet manufacturer, and a real estate and construction empire.

The youngest brother was the one and only Don Giulio Pacelli, “a well known man about the Vatican,” as a reporter once described him.

In 1940, Pius XII officiated Giulio’s wedding in his private chapel; three years later, Giulio named his first son Eugenio, after his uncle.

Giulio was also a lawyer and a colonel in the Noble Guard, a group comprising sons of aristocratic families that saw no active military service (which did not stop him from wearing a uniform of a crisp dark jacket with gilded embellishments and gold fringed epaulets, knee-high leather riding boots, a helmet, and a saber).

Among his business positions (for which he favored the less flamboyant uniform of a dark suit over a white shirt and tie), Giulio was a representative to the administration of the Propaganda Fide, then the Church’s missionary arm; a member of the boards of both the railway Ferrovie del Sud-Est and the Pacelli-founded Banco di Roma;

president of the Swiss arm of that bank;

vice president of an Italian gas company;

papal envoy to Costa Rica;

and an executive committee member of Gherardo Casini Editore (the house that, incidentally, published the Italian version of L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics in 1951).

And for a time he was the president of a company on whose board he served for more than a decade: Istituto Farmacologico Serono.

LAND OF MILK AND HONEY

On December 8, 1953, Pius XII celebrated a new pontifical initiative: the opening of the Church’s inaugural Marian Year, aimed to “revive Catholic Faith and earnest devotion to the Mother of God” that the observant might “conform their lives to the image of the same Virgin.”

The day was a triumph, but a few weeks later Pius XII suffered a debilitating attack of hiccups, vomiting, and nausea, for which he sought treatment from one Paul Niehans. (The Swiss surgeon and former Protestant minister practiced a controversial “rejuvenation treatment.”

At the Clinique La Prairie on Lake Geneva, he injected the buttocks of his famous patients—rumored to include King George VI, Hedda Hopper, and Somerset Maugham—with the cells of fetal lambs and calves, delivered via cesarean section from the bodies of their freshly slaughtered mothers. For the pope, he made house calls.)

By the power of God, Niehans’s ministrations, or pure luck, Pius XII recovered, only for his illness to fell him again in late 1954.

His doctors and nephews arrived at his bedside, believing the end was near.

But a week later the pope was asking for an egg. “Tell him he can have not only one egg, but two,” Time reported a gastrointestinal specialist telling his personal physician, “and have them flipped with Marsala, if he agrees.”

Conception, immaculate and otherwise, was much on Pius XII’s mind in the final years of his life.

The Second World Congress on Fertility and Sterility—for which Lunenfeld’s own Professor de Watteville was one of 12 committee members—convened in Naples on May 18, 1956, for a nine-day summit: some 180 paper presentations, excursions to Amalfi and Pompeii, parties and fashion shows “to entertain the ladies,” and a special pilgrimage to Rome for an address from the pope.

“It is entirely true that your zeal to pursue research on marital infertility and the means to overcome it,” Pius XII told his listeners, as translated from the original Latin by Ronald L. Conte Jr., “engages high spiritual and ethical values, which should be taken into account.” He also said, “As regards artificial fertilization, not only is there need to be extremely reserved, but it must be absolutely excluded.”

A year later, Lunenfeld sat with Giulio Pacelli and Piero Donini, musing over the design needs of the special toilets they planned to install in the convent.

They settled on a teardrop-shaped container akin to a small trash can, lined with a plastic bag.

Throughout 1958, elderly nuns hiked up their habits, crouched over the containers, and voided their bladders.

Serono employees collected the bags of urine and transported them to the Rome laboratory at Via Casilina, where technicians emptied them into metal tanks for processing.

(During a 1930s Netherlands-based urine collection program, the people tasked with picking up donations were called pissmannekes, or “small piss men.”)

By 1959, Serono had harvested enough hMG to begin trials on infertile women.

Lunenfeld, back in Israel, where he was working as a visiting scientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science, wanted to treat his own hypothalamic amenorrheic patients with the drug, hoping to induce ovulation.

The head of the hospital instructed Lunenfeld to inject himself with the substance.

If he didn’t sustain any major side effects, they’d go forward with treatment.

Lunenfeld wasn’t particularly worried about what it might do to his own reproductive health.

For one thing, he says, “I already had a son.”

After the first injection, which an intern administered, Lunenfeld ran a high temperature, an effect of protein buildup in the solution.

He and Donini increased purification methods and Lunenfeld continued to test and burn.

On the fifth attempt, they were in the clear.

Lunenfeld never patented his findings, which could have made him a very rich man.

He says his greatest compensation was the ability to bring the research material and lab equipment to Israel, a “gift” from Serono.

For a short time there, he ran a urine collection program at local elderly care centers, where postmenopausal Israeli women occupied themselves by making baby clothes for the future children their urine would, ideally, help conceive.

In 1962, the first previously amenorrheic, infertile woman treated with hMG gave birth to a healthy baby.

Two more women became pregnant, though they later miscarried.

Still, this was an enormous success, and the Israeli pharmaceutical company Teva Pharmaceutical Industries (today worth $16 billion), working in conjunction with Serono, registered the compound as Pergonal.

That year Lunenfeld became the head of the Institute of Endocrinology at Tel-Hashomer Hospital, now called Sheba Medical Center.

Under his direction, the program grew exponentially, and the institution became a World Health Organization international reference center for fertility-promoting drugs.

One former research assistant, Danny Lieberman, who performed data science in Lunenfeld’s lab in the mid-1970s, describes him as “a paper machine” whose 20-person team published something like 100 research papers in a single year—the entire physics department, by contrast, might produce five.

But what particularly distinguished Lunenfeld, Lieberman remembers, was his broad, inquisitive interest in how science functioned within real human lives.

He once happened upon the nonobservant Lunenfeld, kippah on head, poring over the Torah.

Lunenfeld had been attending weekly study sessions with a rabbi in the hopes that he might learn how to better treat the some 20 percent of his patients who observed the Halakhah, which places constraints on sexual relations according to monthly menstrual cycles.

“I am sad about the suicide which Israel is committing,” Lunenfeld says today.

During his conscription in the Israeli army, he served under Yitzhak Rabin, who would first become prime minister in 1974.

The two remained friends.

When a far-right extremist who opposed Rabin’s signing of the Oslo Accords assassinated the prime minister following what was widely seen as a peace rally, “for me, this was the end of Israel,” Lunenfeld says. “It was not what I fought for.”

The United States granted Lunenfeld a green card in 2001, and for much of the year he resides in Florida, returning to Tel Aviv to visit his children and grandchildren who still live there.

His eldest son, Eitan, is the head of the IVF unit at the teaching hospital for Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

The Lunenfelds are part of a long lineage of fertility specialists in Israel, where the birth rate remains substantially higher than that of other industrialized countries.

Milk and Honey: Technologies of Plenty in the Making of a Holy Land (2023), by Israel-born Tamar Novick, a visiting scholar at the Humboldt University of Berlin, traces a decades-long Judeo-Christian effort to promote fruitfulness in an unfamiliar climate—from Alsatian Christian missionary beekeepers, to dairy farmers during the British mandate, to Israeli scientists, including Lunenfeld—alongside the ways in which the knowledge and practices of the Palestinian people shaped European governance and settlement in the region.

Novick has a fascination with the science of excrement, plus a wry sense of humor; “Taking the Piss” and “Deep Shit” are the titles of two recent presentations.

Her current project is entitled Fountain of Knowledge: How Science Turned Urine Into Gold.

In Milk and Honey, Novick writes that with the Industrial Revolution, “technology did not replace religion as a colonial device but instead was blended with aspirations to salvage the land,” becoming “crucial for seizing control over lands and people.”

Religion, science, and politics intertwined. “Reproduction is such a fertile ground to think about this merging,” she tells me. “Those three elements are always at play.”

DEATH AND TAXES

During the fall of 1958, a depleted Pius XII retired to the papal villa at Castel Gandolfo, the Holy See’s 135-acre summer palace situated high in the hills above Lake Albano, just southeast of Rome.

In the palace courtyard, uniformed schoolchildren gathered to pray, and a knot of reporters set upon the few figures allowed in and out of the residence.

On October 9, while lying in his single brass-frame bed, Pius took his final breaths.

“A small crowd of people was present in the Pope’s bedroom when he died,” reported The Catholic Standard and Times the next day. Among them were princes Carlo, Marcantonio, and Giulio.

The death of a pope is always an upheaval, but in recent decades perhaps for none more personally than the three nephews, who learned firsthand the mortality of blood ties.

Within months, according to one of several articles published by Der Spiegel that year regarding Vatican finances, the commander of the Noble Guard suggested that the Pacelli brothers take a hiatus from their duties within the unit, and the boards of multiple companies requested their resignations.

While abrupt, this was merely the apotheosis of public frustration that had been long brewing around the financial advantages afforded the three men through their relationship to the pope.

And Giulio Pacelli was at the center of the ire, which dated back to his 1946 appointment as papal envoy and plenipotentiary minister of Costa Rica.

The following year, the government had taken aim at tax evasion with an article in the Italian Constitution of 1947 decreeing that “all shall contribute to public expenditure in accordance with their means.”

Pacelli, an Italian citizen, nonetheless hoped to make use of a technicality that exempted diplomatic representatives of foreign powers living in Italy from the tax.

Members of the Vatican State Secretariat obligingly agreed.

The Italian government did not.

For nearly a decade Rome and the Vatican argued the issue, during which time Pacelli’s fortune grew.

In 1955, the Christian Democratic Party minister of finance broke with precedent and popular opinion, officially granting Pacelli immunity.

But by the spring of 1958 (as the nuns diligently urinated), political parties had begun wielding the issue as anticlerical ammunition: “The Pope’s Nephews Don’t Pay Their Taxes” read the headline of L’Espresso, a left-wing weekly.

Later that summer, the same magazine published a list of 11 Catholic laymen who managed the substantial spending power of the Vatican, which included the three Pacellis.

Together, the brothers held positions on some 50 supervisory boards, and their personal combined net worth had dilated to an estimated 18 billion lire, 10 billion of which Giulio held primarily in foreign investments—the equivalent of about $170 million today.

To many, Pius XII’s death marked the beginning of a shift at the Vatican. His successor, John XXIII, convened the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, or Vatican II, which made a crack in the inscrutability of the Church (and coincided with a mass exodus of women religious).

According to Der Spiegel, after learning that certain banks and industrial plants had made overtures to some of his family members in Northern Italy, he forbade his rural relatives from accepting supervisory board positions during his tenure—in response, perhaps, to the complications caused by the Pacelli brothers.

Vatican II heralded larger financial changes.

Back in 1942, Pius XII had created the Istituto per le Opere di Religione, or IOR, to serve as the Vatican’s financial stronghold—the profits of which, under the Lateran Treaty, were exempt from Italian taxation.

A decade later, according to Lunenfeld, the Vatican acquired a 25 percent stake in Istituto Farmacologico Serono.

In 1968, Italy’s parliament voted to resume taxing dividends on stocks held by the Vatican.

Consequently, the Vatican decided it would be prudent to relieve itself of some of its major investments.

The IOR turned to Michele Sindona, a financier with ties to both Hollywood and the Mob, who for years had been insinuating himself into Vatican financial affairs, acquiring banks and holding companies in which the IOR retained significant stakes.

The IOR sloughed Serono off to Sindona as well. By 1971 it still held at least a 3 percent stake in the pharmaceutical company, but that year, Italy approved the marketing of contraceptive pills, and certain church-versus-science discrepancies became too obvious to ignore:

While Serono had been producing a contraceptive called Luteolas for some years, because the pill was illegal, they had billed it as a treatment for “gynecological disorders.”

When the pill went public, according to Der Spiegel, Giulio Pacelli finally resigned as president of the Serono board, citing the Vatican’s firm stance against birth control.

Fabio Bertarelli, who had taken over from his father as CEO of Serono, had been fighting to secure ownership of the company for decades.

As the Italian government issued warrants for Sindona’s arrest in 1974 on charges of fraudulent bankruptcy, the financier fled the country and Bertarelli scooped up his Serono shares, gaining a majority stake in the company.

(After allegedly ordering a Mafia hit on the bankruptcy lawyer tasked with liquidating one of his collapsed banks, Sindona died from cyanide poisoning in an Italian prison.)

By 1990, the company was supplying half the world’s fertility drugs, and Bertarelli was worth $1.5 billion. Upon Fabio’s death in 1996, control of the company moved to his son Ernesto who, four years later, listed its shares on the New York Stock Exchange and in 2007 sold the family’s majority stake to Merck for $13.3 billion. Later that year he commissioned a 318-foot superyacht, the Vava II.

THE FANTASTIC DRUG

In the beginning, Pergonal did its job too well. A 1965 issue of Life described it as “the fantastic drug that creates quintuplets,” as women in California, New York, and Sweden gave birth to sets of many babies.

Urine collectors recruited donors through door-knocking campaigns and made daily drop-offs to plants in Umbria and Benevento; from there, refrigerated trucks transported frozen hormone adsorbate to Rome.

Soon Serono added collection centers in Argentina, the Netherlands, and Spain to the ones in Israel and Italy, with 600 women contributing, which could produce 40,000 ampoules per year—then enough to treat the worldwide population of hypopituitary-hypogonadotropic amenorrheic women.

The introduction of IVF—for which multiple mature eggs are ideal—and new protocols prescribing hMG to patients with tubal factor infertility increased demand.

By 1985, 2,000 women in the US were prescribed the drug. Soon patients worldwide required 30 million liters of urine; when hMG became part of a protocol in male factor infertility, the number ballooned to 70 million.

(Lunenfeld turned his own research to male infertility and founded the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male in 1997.)

In 1995, despite twice-daily pickups from 100,000 urine donors, a shortage of Pergonal caused panicked patients to hoard prescriptions. “I feel like an addict,” one woman told The New York Times.

Eleven years later, Serono phased out Pergonal (focusing instead on another fertility product, Gonal-f, made from hamster ovary cells) and Ferring released Menopur.

Citing proprietary information, a Ferring spokesperson declined to answer detailed questions (including where urine is collected, and whether donors are compensated), and sent a statement which read, in part, “Ferring believes that everyone has the right to build a family and to choose their own path to parenthood. We recognize and work to address diverse family building needs and fertility journeys, including for the LGBTQ+ and ‘single parent by choice’ communities who use in vitro fertilization to start or grow their families.”

(The website of the Swiss pharmaceutical company Institut Biochimique SA, which produces a similar menotropin, Meriofert, is more transparent about its sourcing: “Every day the urine of pregnant or post-menopausal donors is collected in rural Chinese villages.”

A representative for IBSA declined to provide information on donor compensation, stating that “IBSA decides to cover product topics only in scientific journals.”)

In February, Pope Francis, who last year reaffirmed the Vatican’s anti-IVF stance, addressed the general assembly of the Pontifical Academy for Life, a papal-appointed body responsible for developing Catholic teachings and positions on such topics as abortion, artificial intelligence, and IVF. “For those committed to a serious and evangelical renewal of thought,” Francis said, “it is essential to call into question even settled opinions and assumptions that have not been critically examined.”

(A few weeks later Tim Kaine, who is Catholic, brought to the State of the Union, as his guest, Elizabeth Carr—America’s first IVF baby, courtesy of Pergonal.)

While the pope made his address, Lunenfeld and his wife were in the middle of a vacation to celebrate his 97th birthday, beginning with a cruise from Fiji around New Zealand and Australia.

From there he continued to Singapore, where he reunited with old colleagues, including three of Serono’s former Singapore-based representatives.

At one point during our conversations, I ask him about his own relationship to religion.

“This is very strange,” he says, “very strange.”

He has a hard time defining it. His wife, who’s agnostic, calls him religious.

He doesn’t keep kosher, but he prays every morning.

“I believe in God because so many things, good things, happened to me. Thinking of the Kindertransport, something must have helped me, somewhere,” he says. “This is something which is troubling me a lot to understand—and there’s no way to understand.” No small thing for someone whose life’s work has been tracking down answers.

“Everything was miracles.”

0 notes

Text

'With a single tremendous flash across the New Mexico desert, J. Robert Oppenheimer — director of the Manhattan Project to develop the world's first atomic bomb — became the most famous scientist of his generation.

The piercing light, dimming to reveal a terrible fireball growing in the sky above the July 1945 Los Alamos test site, heralded the dawn of the atomic age. A physicist, polymath and mystic, Oppenheimer recalled greeting the mushroom cloud with a line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita that he had taught himself Sanskrit to read: "Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds."

The creation of the atomic bombs and their subsequent devastation of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to World War II, beginning a new era that would transform Oppenheimer into a historical icon. Yet his remorse for what he built and his opposition to its further development drove him into conflict with the U.S. military, and the government revoked his security clearance due to his communist sympathies. Oppenheimer ultimately died a broken man.

Ahead of the July 21 release of Christopher Nolan's biopic "Oppenheimer," Live Science sat down with historian Kai Bird, Oppenheimer's biographer and co-author of "American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer" (Knopf, 2005), the Pulitzer Prize-winning book that inspired the film.

We discussed Oppenheimer's rise and fall, his development of the bomb, and the way he altered human history forever.

Live Science: The Manhattan Project was an immense effort. It took thousands of scientists working tirelessly throughout the war — spending the modern-day equivalent of $24 billion — before it was completed. How instrumental was Oppenheimer in the construction of the bomb? What was his motivation for building it?

Bird: Well, he became the director of the scientific lab for the Manhattan Project, and it was his notion to have the main lab and build the bomb in Los Alamos. He built the gadget in two and a half years, and everyone who worked on it that we interviewed all said that it would never have happened if Oppenheimer had not been the director. He inspired people to work hard and to figure out, in a timely fashion, all the various engineering problems associated with building the bomb.

As for his motivation, it was quite clear. As a young man, he studied quantum physics in Germany under Max Born. While there, he'd attended lectures by [Werner] Heisenberg — the famous German theorist of quantum mechanics' uncertainty principle — and he knew that Heisenberg and other German scientists were just as capable as he was of understanding the physics of the atomic bomb and the potential for a weapon of mass destruction, and he feared that by 1942, the Germans were probably 18 months ahead in the race to build this weapon.

Politically, he was a man of the left. He feared fascism and feared that the German scientists were going to hand this weapon of mass destruction to Hitler, who would use it to win the war. That was his worst nightmare.

Live Science: Yet by the time they had built and successfully tested the bomb, his motives had become muddied. You write that he was anxiously puffing his pipe, repeatedly referring to Hiroshima's citizens as "those poor little people." Yet that same week, he was giving the military precise instructions on how to make the bomb explode over them with maximum efficiency.

Bird: I'm glad you picked up on that. It's a really incisive anecdote that gives you a sense of the man, his complexity and his ambivalence about what he was doing.

By the spring of 1945, all the Los Alamos scientists working so hard to build this gadget knew that the war in Europe was over. So why were they doing it? They actually had a meeting to discuss this difficult political issue. Oppenheimer attended — he stood at the back of the room, listened to the arguments and then stepped forward to quote Niels Bohr.

Bohr had arrived in Los Alamos on the last day of 1943. He greeted Oppenheimer with, "Robert, is it really big enough?" He wanted to know if the gadget was going to be big enough to end all war.

Oppenheimer made this argument to his ambivalent scientists in Los Alamos. He told them that this weapon is known now, there are no secrets behind the physics, and the power and awfulness of this weapon needs to be demonstrated in this war. Otherwise, the next war is going to be fought by nuclear-armed adversaries, and it will end in Armageddon. That was the argument. It was an interesting argument. It was also a rationalization.

Live Science: After the war, Oppenheimer became nuclear weapons' most vocal critic — resisting efforts to make a more powerful hydrogen bomb and referring to the Air Force's plans for massive strategic bombing with nuclear weapons as genocidal. What caused this reversal, and how did the military and intelligence establishments react?

Bird: This is what leads to his downfall. Because very soon after Hiroshima, we know from the letters that Kitty, his wife, wrote to friends that Oppenheimer had plunged into a deep period of depression; he became extremely morose.

Then he went back to Washington, and he learned more about how close the Japanese were to surrendering in September 1945. And he also learned more about the attitude of those in Washington and of the Truman administration to this new weapon — i.e., they want to build more of them and make U.S. national security entirely dependent on a huge arsenal of these weapons.

Oppenheimer thinks this is a mistake. As early as October 1945, he gave a public speech in Philadelphia in which he said that these weapons were weapons for aggressors. They are weapons of terror, they are not weapons for defense and the U.S. needs to find a way to construct an international control mechanism to prevent their proliferation.

He was coming out against the notion that we should rely on these weapons for our defense. And that was a direct threat to the War Department, the Army, the Navy and the Air Force, who all wanted bigger budgets to acquire more of these weapons.

So Oppenheimer became a threat. And this was precisely what led, in late 1953, to the first steps to strip him of his security clearance, put him on trial in a kangaroo court setting and publicly humiliate him.

Live Science: Some of the people who knew Oppenheimer felt he was — in the words of his fellow physicist and friend Isidor Rabi — someone who "never got to be an integrated personality." And Einstein referred to him using the Yiddish word "narr": fool. What were they getting at with these remarks?

Bird: Oppenheimer was a polymath and somewhat of a mystic, and he was attracted to Hindu mysticism, which Rabi thought was a sign of a less-than-integrated personality. But I do think Rabi was onto something. And Einstein too.

Before his trial in 1954, Oppenheimer visits Einstein to explain that he's about to go down to Washington. He tells him he'll be absent from the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton [where Oppenheimer served as director from 1947 to 1966] for some weeks because he's going to be put on trial in this security hearing.

And Einstein turns to him and says something along the lines of, "But, Robert, why are you bothering if they don't want you and your advice anymore? You're Mr. Atomic; just walk away." Oppenheimer replies with, "Oh, you don't understand, Albert. I need to use my status and my platform to influence Washington policymakers and give them my advice. They don't understand this technology, and I need to use my celebrity for a good purpose."

In fact, Oppenheimer was fighting the security hearing precisely because he wanted to be a player. He wanted to be inside the establishment. He wanted to walk the halls of power in Washington and to have meetings with the president in the Oval Office. He was attracted to all of that, and he found it difficult to walk away from. So after Oppenheimer leaves the room, Einstein turns to his secretary and says, "There goes a nar."

And yes, he was being foolish and naive, politically. He had no idea what he was about to walk into. The security hearing in Washington was all rigged against him. He'd made really powerful political enemies in Washington, and he was going to be destroyed. Einstein was right to call him a narr.

Live Science: Oppenheimer's legacy is tied to a terrifying weapon that we have avoided using in war again. Let's say we skip 100 years or so into the future. How do you think people will remember him?

Bird: That depends on what happens and how well we live with the bomb. Say that in the next few years or decades there's another nuclear war. Oppenheimer is going to be seen as the scientist who is responsible for that, too.

The incredible thing is, we will still be talking about him in 100 years. Human beings are increasingly drenched in science and technology. We're now going to be grappling with artificial intelligence. You would think that we would be turning to scientists and technology experts to ask the right questions about how to integrate all the science into our daily lives without destroying our humanity.

And yet, many people seem to have an innate distrust of scientists and expertise. I trace some of that back to the roots of Oppenheimer's public humiliation in 1954. It sent a message to scientists everywhere: Do not get out of your narrow lane, do not become a public intellectual and do not speak out about politics or policy.

But, unfortunately, that's precisely what we need. We need more Oppenheimers who are willing to speak the hard truths about how to integrate science and make it so that it's not destructive but an empathetic part of our human existence.'

#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Einstein

0 notes

Note

Yo, saw your post about levihan prompts:

How about Hange discovering Levi’s secret hobby (of your choice)

Feel free to do whatever you feel like

And I love your work! 💕 have a good day

Hello! So sorry for the delay in this one, but thank you so much for your patience 🙏 I got stuck for such a long time in the middle of this ksksks but it is finally done! I also played around a little bit with the whole...discovering a secret aspect, but I hope you'll enjoy it anyway! And I hope you're ready for some sweet sweet childhood friends levihan~

**

Levi likes photography.

This, in itself, is no great secret. Hange can barely remember a time he wasn't following after her with a camera strapped around his neck, or packed into his bag—always within reach, should something striking catch his eye. A little neon plastic toy, at first; each click of the shutter cycled through preloaded images, expert shots of famous landscapes, places they could only dream of seeing. And then, a polaroid—still a toy, in essence, still plastic, still gaudy, but this one took real pictures in real time, and spit them out into their eager, shaking fingers within seconds.

Hange remembers them ruthlessly wafting the little laminate squares and watching with bated breath as black mottled into foggy grey, as the blurred silhouette of the park bench faded slowly into being. It was a fascinating thing, at the time. Magic at their fingertips. The picture turned out fuzzy and overexposed in places, where the sun had glared in over the corner of the park bench, but Levi had settled the little square on his little palms and looked at it like he held the whole world in his hands.

There were innumerable disposable cameras, too. Light little things with reels of film, never enough for Levi's insatiable desire to snap pictures of every single thing he saw. They spent half their childhood in the chemist, sitting in the hard plastic chairs, wriggling anxiously as they waited for the film to develop. Kuchel always handed them the envelope, fat with prints, with a small smile curling the corner of her mouth and a fond twinkle in her eye, and Levi always took it politely, while Hange gave a boisterous thanks, and the pair of them delved greedily into their spoils.

He was older, in his early teens, when he was gifted his first real camera. It was heavy, compared to all the others, a case made of metal with buttons and gadgets and a fancy screen on the back, to preview each picture he took. Levi was wholly enamoured with it. He spent hours adjusting it, figuring out what each button and knob did, how they affected each picture; took countless shots of the same rock in the park until he'd tested every combination of settings he could think of.

He had cycled through more cameras since then. Grown a small collection, each one a little different, a little more suited to particular shots. Hange understood the concept in theory, but the particulars were lost on her, and Levi never took the time to explain. Not that she minded—Levi's pictures were beautiful, breathtaking in the way he could capture even the most mundane details and make them something wondrous. Perhaps for the first and only time in her life, Hange had no desire for the magician to reveal his tricks.

He has an eye for things that Hange simply cannot see. She is observant—to a fault, at times, intensely analytical and endlessly curious. Everything is a question, an opportunity to research, to learn, but she doesn't see the way Levi does.

Wild daffodil. Narcissus pseudonarcissus. Hange sees a perennial flowering plant, native to Western Europe, classified by its pale yellow petals and elongated central trumpet. She sees phylogeny with a rich taxonomic history; subspecies originating all over the globe, some larger, some smaller, some more vibrant and some more muted. She sees anatomy, science.

Levi sees the way the evening sun rusts the buttery petals until they blush; sees the way dew drops hang like pearls from the tips of the leaves in the early morning, when the light is still smoky and thin. He sees a moment to be captured.

It should be impossible for a picture to hold so much detail. Hange can look at Levi's daffodil and feel the way the spring wind blows gently on her skin, the sun warm but the breeze a little biting, a remnant of the fading winter. She can smell the pollen heavy in the air, feel the tickle of short grass on her ankles, hear the trill of songbirds in the branches of distant trees.

His proclivity for photography grows with them. Hange's interests spear out in a thousand different directions, from physics and chemistry to botany, to engineering, to literature and mathematics, to history, languages and landscapes—life is a limitless source of information and Hange chases it every which way, insatiable.

And wherever she goes, Levi dutifully follows, with his camera in hand.

Until now.

Now, they are eighteen. The summer is lazily drawing to a close, and tomorrow, at 8:45am, Hange will be boarding a plane that will take her to the other side of the world to attend the university of her dreams.

And Levi will be staying here.

Despite Levi's perpetual scowling and indiscriminate grunting, their last evening together had overall been a pleasant one. Levi and Kuchel had worked hard on their meal, and it had been nice in a warm, filling kind of way, to spend her last night at home with the two of them.

Now, she and Levi are holed up in his bedroom, while Kuchel had insisted on doing the clean up herself. Hange's mind has been churning non-stop for weeks now, ramping up with each passing day, and tonight, her thoughts are unstoppable, and they spill from her with giddy, jittery excitement.

"The university is huge, but my course is pretty small—only like, 30 places. It'll be easy to get to know everybody."

"Nn."

"And did I tell you? There's a museum right on campus? They've got a huge collection, and I heard students can access it after the first semester."

"Hm."

"And there's a flower garden, too—they've got species from all over the world, Levi. They'll have plants I've never even heard of."

"You said."

"Oh! And—my accommodation isn't all that far from the coast. The water looks beautiful in all the pictures I've seen—look, see?"

"I know. You showed me already."

Hange looks up from her phone, where the screen is lit with a bright, sunny beach, tan sand and a stark blue ocean. Levi flicks his gaze over it and offers a noncommittal shrug of his shoulder. Hange frowns at him.

"You could at least pretend to be excited, you know."

Levi gives her a deadpan stare.

"It looks...warm."

Hange sits back with a thump, and kicks weakly at Levi's shin. She pouts over at him. "Better than nothing, I guess."

They sit at opposite ends of the window bench in Levi's bedroom, legs tangled haphazardly together in the space between them. The window was thrown open in some vain hope of tempting in a breeze, but the air is thick, and the soft wind that does blow is still stiflingly warm. It sways Levi's fringe against his brow, but does little to stave off the oppressive heat.

The sky outside is dark, but it is alive with stars. They cast bright sparks on an inky black canvas, and there is no moon in sight. Already, Levi has snapped pictures of it, twisted dials and pushed buttons and switched lenses until he was satisfied.

It is a beautiful sight. Infinite.

Hange lets one leg dangle out the open window. Levi gives her a sour look and wordlessly closes one hand around her other ankle. She has a long history of behaving carelessly—Levi has borne witness to one too many slips and stumbles to trust her entirely. It would be just like Hange, to miss her flight in favour of a trip to the emergency room.

His thumb strokes back and forth absently. There is a callus there, rough and catching, that scratches against her sensitive skin.

Her predominant feeling is one of excitement. Studying abroad had been a dream of hers for almost as long as Levi had owned a camera—to travel beyond the bounds of their small rural town, to see more, learn more, fuel the relentless hunger in her. But there is an undercurrent of something else, some squirming discomfort that refuses to settle. It intensifies with every sweep of Levi's thumb against her skin until it sits heavy in her gut.

She looks over at him. His gaze is trained out the window, a small frown furrowing the skin between his brows, but his eyes are glassy, with none of their usual sharp, unwavering focus. Whatever he is looking at, he is not really seeing it.

It would be a lie to say that his silence had not troubled her. He had been quiet throughout dinner, opting instead to listen to Hange and Kuchel's companionable chatter as he pushed his food around his plate, and he had barely said a word since they had cleared the table and retreated to his room. He had hardly even looked her way.

Irritation bubbles within her. Levi is always more subdued than she is, content to sit quietly while Hange babbles endlessly, about anything and everything. But he usually has something to say. His silence, today of all days, makes her angry. They have one night left like this—one more night to talk, face to face, before they will be separated for who knows how long, and Levi is offering her nothing.

"Levi," she says, before she can think. Something in her tone must startle him, for he blinks rapidly, as though pulled out of a daydream, and rolls his eyes to look in her direction. His gaze settles somewhere near her shoulder. She bristles. "Can you at least—"

"Levi?" Kuchel's voice is distant, floating up from the bottom of the stairs. Levi looks at the door instead. "Can you come give me a hand for a minute?"

Hange clamps her jaw shut. Levi casts her another sidelong glance, and ticks his tongue against the back of his teeth. He squeezes her ankle once, then pushes himself to his feet. "Don't fall, idiot. I won't be long."

Hange feels distinctly like a child on the verge of throwing a tantrum. It's immature, and perhaps it's unfair of her, but she had assumed that Levi's invitation for dinner might, at the very least, come with a little conversation.

She takes a deep, steadying breath. They never fight, not really—they bicker endlessly, poke each other's cheeks and pull each other's hair, childish rough housing that they never grew out of. But they don't fight and as grumpy as Hange feels about Levi's near silence, she doesn't want to start now. She runs a hand back through her hair and sweeps her eyes about the room, counting long, even breaths as she does.

Levi's room is immaculately neat and tidy. Everything has its place, on clean, dusted shelves, or stacked in straight, neat piles atop his desk. It is a level of organisation Hange has little energy for; she herself is a hurricane, picking up and dropping off detritus everywhere she goes.

But Levi's borderline obsessive cleanliness makes it easy to spot something that is out of place.

Hange's gaze falls on a drawer in the desk. The drawer itself is as immaculate as everything else, gleaming wood and a reflectively polished brass handle. What catches her eye is the corner of a glossy piece of paper, caught when the drawer had been closed.

Hange is a curious creature. Rarely can she hold herself back from exploring an unknown, and now is no different. She unfolds herself from the bench and stretches to stand, then crosses the room on light, tip-toed feet.

Levi is, by and large, a rather private person. He does not share much of himself openly, hides behind an impassive mask, guards what is dear to him close to his chest. Hange is an exception to this rule, whether Levi wanted her to be or not.

As such, she has no real issue prying the drawer open, and is unsurprised by the predictable contents within.

Photographs.

Of course it was photographs.

Her lips tug up in a fond smile and her eyes roll, but it is as she is reaching in to flatten out the rumpled picture that had been poking out of the drawer, that she notices what they are photographs of.

Her.

Hange picks out a stack and sits cross-legged in the desk chair. She flips through them, eyes growing wider with each new picture she uncovers. Every single one is of her. Some recent, some not so recent—some must be from the very first real camera, for she is still in her braces, all thin, gangly limbs and scruffy hair and taped up glasses.

There are pictures of her in the winter, mitten-clad hands wrapped around a paper cup of hot chocolate, blowing steam into the chill air. She can see in stark clarity, the red tip of her nose and the chill bitten over her cheeks; she can almost feel the cold, taste the cocoa on her tongue.

She finds a picture of her from an autumn years gone by. She remembers it as though it were yesterday—they had spent the whole afternoon raking fallen leaves in the courtyard behind Kuchel's cafe, scooping them into a terribly tempting mound beneath the shedding tree. Hange had been unable to resist. Levi had captured her moments after her dive into the pile, sitting up with her weight propped back on her hands, dry leaves clinging to her messy hair and sticking to the fibres of her cardigan. The sun was low, and it cast her in a golden glow, highlighting the vibrant red and orange of the fall foliage around her, drawing out the auburn undertone in her hair and the amber of her eyes. Her smile is almost blinding.

Another shows her in the spring, laying on her belly in the long grass beside a row of blooming daffodils. There is a book spread open before her and she is, as expected, engrossed in it; Levi has snapped the shutter as she was turning the page, the thin edge of the paper caught between the delicate tips of her fingers.

Hange has never considered herself to be particularly pretty. She is just...Hange, a little bit of wild, a little bit of manic, a lot of clumsy and dirty. Being attractive has never been of much concern.

But there is something in the way Levi has photographed her, time and time again, in the way the light catches her, the candid ease of each new picture, that looks....beautiful, in its own way. Somehow, he has made her mess into a masterpiece.