#I will only be accepting discourse on this matter in the form of an academic journal article

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Dear lynx, if gryffindor is for gays, where are the straighties going???

I’m sorry to say it, but everywhere else!! this is why no one’s personalities in the books matches their house—it’s all a ruse.

but we have some caveats. aro/acespec friends get presented the ravenclaw option too. genderqueer folk get offered hufflepuff as well. bisexual disasters like harry get a choice between gryffindor and slytherin. but most slytherins are straight. sorry.

my evidence:

- vibes

#gryffingays 2024#I will only be accepting discourse on this matter in the form of an academic journal article

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human shield politics, part 1: the poverty of accessible theory

Why is it wrong to use human shields?

I asked Claude the chatbot (3.7) for a spread of both mainstream and academic-legal reasoning on this question, figuring this is a good use case for a chatbot to summarize what people have said rather than finding a 'right answer'. There's lots of written material on this topic that a chatbot has surely read. Claude's first answer was the Geneva Conventions, which matches my experience with real people saying that.

Several of Claude's answers are similar: using human shields violates the Geneva Conventions, the ICC has established that it's illegal, it's forbidden by international humanitarian law, it's forbidden by the laws of war, et cetera. Legalism in various forms strikes me as a bad and mostly wrong answer, because it would imply that human shields are acceptable if your country withdraws from the Geneva Conventions first. I do not believe that.

Then there's a couple of ivory-tower reasons suggested, like: Kantian respect for persons.

Using human shields treats people merely as means rather than ends in themselves. This violates the fundamental moral principle that human beings possess inherent dignity and should never be reduced to mere instruments for others' purposes.

Commanding an army in war is usually reducing lots of soldiers to means, so this argument is least convincing for one of the situations (war) where human shields come up the most. Also, it doesn't deal with the case of volunteer civilians willing to be human shields.

Or this:

Principle of non-maleficence in humanitarian ethics - The "do no harm" principle, central to medical ethics and humanitarian intervention discourse, is directly contravened when parties deliberately place civilians in danger.

If you try to tell a general to conduct his operation by the principle of "do no harm", he's going to have you escorted out for wasting his time. War is in large part about doing and threatening harm. "Do no harm" is good in the abstract, but when one is in a war then that principle has already broken down, one needs something else to guide conduct in war.

Claude also suggests Michael Walzer's theories of just war. I reviewed Walzer's Just and Unjust Wars a while ago, it's pretty good, but the whole book has only one single mention of human shields in passing. Slight chatbot hallucination?

Claude made several overlapping suggestions about how one isn't supposed to endanger or harm non-combatants, innocents, or civilians in war, with nice words like "fundamental principle". But these suggestions are easily bent into arguments for the use of human shields, because of the fundamental principle that the other guy isn't allowed to harm them!

Now, I wouldn't rely entirely on a chatbot. I went to see what was in published papers about human shields, and the first ten published papers I found in a search on the topic were studies, accusations and denials of the use of human shields in the Israel-Palestine conflict. I thought one paper was going to be about something else because it didn't have "Israel", "Palestine" or "Hamas" in the title like the other nine did, but then I read it and it's studying the use of human shields in Sri Lanka and Israel-Palestine. Filtering out everything involving Israel, Palestine, or Hamas, I found papers like this one on targeting human shields, not on using. (sci-hub)

I expect there's good writing about the wrongness of using human shields out there somewhere, but it's hard to find among all the legalism and the obsession with desert grudges. There seems to be widespread agreement on the moral fact of "using human shields is wrong", but the common reasons given strike me as ill-considered ad hoc excuses. Even in high places and official journals, I see Geneva Convention legalism.

In addition to being poor moral-philosophical grounding for the matter itself, this void also results in ignorance about the appropriate reaction to a human-shield-user who decides to disregard the Geneva Convention, or the appropriate second-order reaction to someone who decides to shoot through a human shield to get at a human-shield-user. These are moral questions, strongly dependent on the nature and moral wrongness of using human shields, and cannot be settled by pointing to the Geneva Convention's laws. Crudely: "It's wrong, but we have no idea how wrong it is, or how to punish it, or whether retribution is acceptable."

I suspect this contributes to a failure to maintain the norm against human shields, literally and metaphorically, which I will expand on in part 2.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just found out that I didn’t get into my Universities paid summer internship program, and I’m heartbroken. This would have let me work in the field I’m studying to be a part of, it would have let me get my name on an actual academic paper, it would have given me a ton of useful experience, and it would have allowed me to produce knowledge instead of simply receiving it (something I’ve wanted to do since the beginning of my first year). I have just missed a huge opportunity, and it feels terrible.

(Big long emotional self reflective post below. I don’t expect anybody to undergo the emotional labour of engaging with this post, this is mainly just me thinking out loud into/onto something. It isn’t really a rant or a vent, I’m not trying to blast my emotions at others so I can feel better, and I’m not just pointlessly rambling. However, this is all personal IRL stuff, you have no obligation to engage with it.)

Now I’m just kind of left with several months of nothing until the start of March next year. This also once again highlights one of my biggest personal issues, which is that the entirety of my self esteem is built upon my academic success. I do well, and in university I actually receive affirmation. My success actually gets noticed (unlike my experience in school), I have good relationships with my tutors and professors, and I seem to be well liked by most of them. I was directly told by my academic advisor that it will be tragic if I don’t continue onto a masters degree after completing my bachelors, and I’ve made it onto the deans merit list twice!

For the first time in my life I’ve felt like I have actual meaningful talent, like I have value. I’ve come to believe that I am actually intelligent! Back when I was younger if you asked me what my best qualities were I wouldn’t have been able to answer you. I was a neurodivergent kid who grew up in the world of the primary and secondary education system, who bounced between professionals and “professionals”, who lived under the control of the biomedical gaze, and who was only able to understand themself through the language of the medical discourses that defined me by my hardship and suffering. I grew up trapped within systems that only focused on what I couldn’t do.

And so when I found myself in a system in which what I COULD do was the focus. When I found myself not being defined by my inability, but instead affirmed for my ability, I began to develop an ego and some actual self esteem. However, the issue is that when your entire positive sense of self is built upon one thing, when that singular thing is challenged (as it just has been) it is not simply a piece of your positive self image that has been challenged, it is the entirety of your self worth that gets challenged.

I know I’m not stupid, I know the fact that I didn’t get selected doesn’t mean that I wasn’t good enough (just that somebody else was better suited for the position). But this still feels like failure, and the entirety of my self esteem rests on my lack of failure.

It reminds me with a discussion I had with my therapist in which we were talking about my self esteem, and she asked me what things I liked about myself. I told her that I like to think that I’m pretty smart, and that I do well in subjects that I care about. She accepted this, but then she threw me a curveball: “What else do you like about yourself? What else do you think you’re good at? What are the other pieces that form your positive self esteem?” I couldn’t answer her, I had nothing to say, because the answer was that there wasn’t anything else.

Right now I am experiencing the effects of building your entire self esteem upon a single factor. My advice? Don’t do that, because even the smallest challenge to that idea will deal significant emotional damage to you, and it feels like shit.

I don’t know what to do now, I feel like this should be a wakeup call for me to find other sources of self esteem, to find other ways to feel like I matter, to find other things I’m good at, to discover that I have value in other ways.

But I’ve spent the vast majority of my life feeling like I don’t, like I was an issue to be solved, being told to try harder, do better, work harder, I experienced life of never feeling like I was good enough. I know that everybody is supposed to have inherent value, and that I am supposedly good enough simply by being me, but on an emotional level I feel like I can’t accept that. It feels like toxic positivity bullshit, “love yourself!!1!” feels like unhelpful bullshit, because my self-love is conditional, and it always has been. How can I “love myself” when I have not earned my own love, when I do not deserve my own love? I am told to love myself, but I don’t, and I don’t want too.

Why would I?

I’ll be ok, I always end up being ok. It just fucking sucks to be reminded that you aren’t exactly a well adjusted person, and that you don’t know what to do about that.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Content Analysis, I understand it shouldn't be in essay format, but should I only use a Word doc to create title page and heading/design layouts etc. or would a PowerPoint presentation be acceptable?

PowerPoint for the entire project would work - as long as you don't create a powerpoint presentation. It should be formatted with paragraphs and images and graphs and discussion, and a few bullet lists.

And am I inputting my Content Project data and introduction that I previously submitted that's edited into the final copy, but only data that has meaning towards my research question?

You should revise previous submissions for inclusion in the final.

Your raw data can be included as an appendix - I want to see graphs representing ALL the data in the final draft. Then, you can point to the standout pieces from all the data. But, you need to represent all the data first otherwise the 'standout' pieces read like "trust me, this matters" instead of you showing me/reader it matters in relation to other data you collected.

I wasn't sure what placeholders were in the context to the sections, do they mean the subtext of what each section is showing in the visuals slides or pages?

Yes - subheadings, where images will go, where you know you need to further develop analysis. Indications of what else you need to create as you move toward the final draft.

And with the data visualizations, is that only the graphs or is there something more we should include on that section?

If you discuss something because the data shows you that matters, or is routine, or is low....show a screenshot from the content too. What does this look like in non-data form, in content form. Represent your ideas, visually, in multiple ways to help your audience/reader/me build a strong understanding of what you see.

I will present the relevant data to this audience as an academic audience as well. I also plan to expand my analysis to show the data within a multimodal presence that I analyzed that includes music because it is data driven from the way I analyzed the narration/multimodal aspects versus a plain one on one interview in reviewing the data and seeing a response from the discourse community, would that be something I discuss in both Method since I encountered more data relevant to the user experience and my hypothesis?

You will discuss your decisions for this focus in the method section, and how you collected this data. Then you'll discuss what the data shows and why that matters in the data analysis section.

Also for the How to Write guide for the content creators audience, I understand this section should be much smaller than the content analysis but I wasn't sure if I should present it in a simple way with a design layout from Word doc on one page?

YES!!!!! One page is good - simple is so smart.

I definitely for this audience will only use the meaningful data to support my research question and try to give them takeaways so they could use my info as a content strategy.

Do they need the data???? I would focus on building your credibility through your sample content, not the data.

Dr P Check In-Assignment Questions...

On the Content Analysis, I understand it shouldn't be in essay format, but should I only use a Word doc to create title page and heading/design layouts etc. or would a PowerPoint presentation be acceptable? And am I inputting my Content Project data and introduction that I previously submitted that's edited into the final copy, but only data that has meaning towards my research question? I wasn't sure what placeholders were in the context to the sections, do they mean the subtext of what each section is showing in the visuals slides or pages? And with the data visualizations, is that only the graphs or is there something more we should include on that section? I will present the relevant data to this audience as an academic audience as well. I also plan to expand my analysis to show the data within a multimodal presence that I analyzed that includes music because it is data driven from the way I analyzed the narration/multimodal aspects versus a plain one on one interview in reviewing the data and seeing a response from the discourse community, would that be something I discuss in both Method since I encountered more data relevant to the user experience and my hypothesis?

Also for the How to Write guide for the content creators audience, I understand this section should be much smaller than the content analysis but I wasn't sure if I should present it in a simple way with a design layout from Word doc on one page? I definitely for this audience will only use the meaningful data to support my research question and try to give them takeaways so they could use my info as a content strategy. Thank you! @npfannen

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Just interested to hear your perspective on this! I've noticed there's so many femme4femme lesbians, and i have a butch friend who was saying she's finding it impossible to find a femme who's into butches. I've definitely seen that sentiment online. From what I can tell, there used to much more of a femme4butch interest. But obviously that's all from like lesbian history posts/articles and not lived experience. Do you think that's something that's changed?

I answered this questions brilliantly and with much thought and then the palm of my hand hit a button and "poof!" I lost it all. Tumblr needs a save as I write feature. And also spell check. I will attempt it again.

I can first assure you that there are lots of femmes out there looking for butches. I hear from femmes they can't find butches LOL Ahhh the lesbian condition. We are all looking and can't find each other.

When I was coming out it was the early 90's and most of what I saw were butch/femme and not because there were not butch/butch or femme/femme couples, I just didn't recognize the couples for what they were. Lack of observation skills beyond what I understood and most (unconsciously) connected with. I was spending most of my energy convincing myself that I could be attracted to any woman and ignoring my natural inclination to like women more feminine than I am.

I think both through the (sometimes) harrowing world of on line discourse and lesbians not getting as much intergenerational exposure in real life, what we tend to see is through the eyes of society where Femme4Femme is a more comfortable narrative for the average audience. So that is what general (ie straight) media puts out there. Butch4butch is not something the greater public can wrap their head around as a rule. And Butch Femme comes under fire as “man/woman” roles so it is avoided. What we most often see is actually sort of in the middle. Two women with vague lesbain qualities. That is easier for wider audiences to be “ok” with I guess.

I am horrible about academic ideas and historical perspectives on lesbian culture unless I was a part of it. But I can tell you that as I was coming out in 1993 there seemed to be a slight shift away from butch and femme couples using those words to describe themselves in the larger LGBT world. BUT in lesbians circles, like women’s festval where I learned about butch) I was seeing even old school butches begin to break away from butch requiring femme to be a thing. I was exposed to the idea that butch and femme exist as their own and do not require the presence of one for the other to be recognized.

Basically butch stood on its own as a describtive word that cover the experiences, perceptions and “energy”, for lack of a better word. that certain women have with out effort, just as they exist. Same with femme. This use of the terms meant that those butches attracted to butches or femme attracted to femmes to anything in between was accepted WITHOUT one loosing the use of the words butch or femme.

Basically the words were not dependant soley on the relationship to each other. I do believe that no matter where a lesbians true passionate attraction is there is an undefinable connection that butches and femmes share but it does not have to be under the circumstances of a romantic relationship. It can be friendship or even something as simple as acknowledging we recognize each other in a crowd.

The more relaxed idea that butches and femmes to not need to be attracted to each other for them to exist as butches and femmes have made it much easier for other connections to form (butch4butch or femme4femme or inbetween) and be public and seen. A femme does not have to no longer use femme if she is married to lesbians who is neither butch nor femme etc. Butch/Femme couples and butches and femmes looking for each other are out there but the other pairing are more visible as well.

Remember, the wider social media will promote only what it is comfortable with which tends to be femme4femme and that is NOT a true picture of lesbian reality.

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

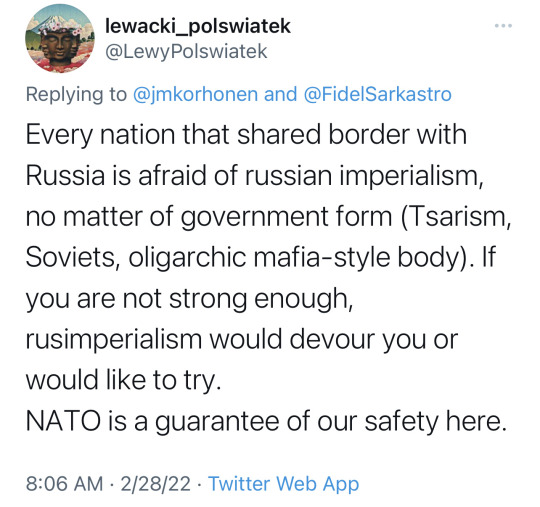

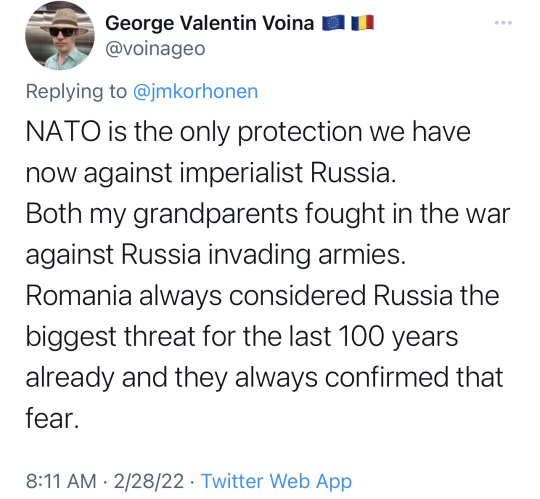

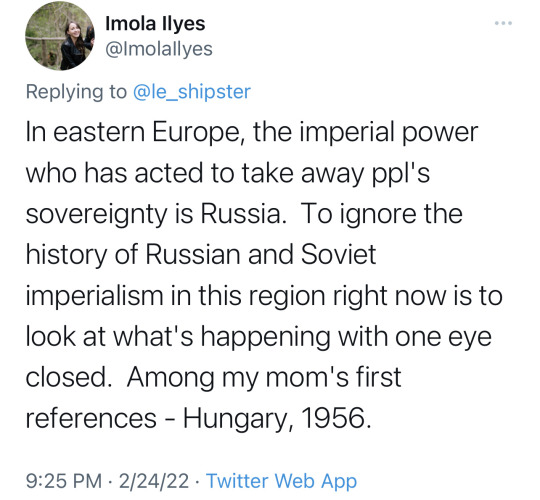

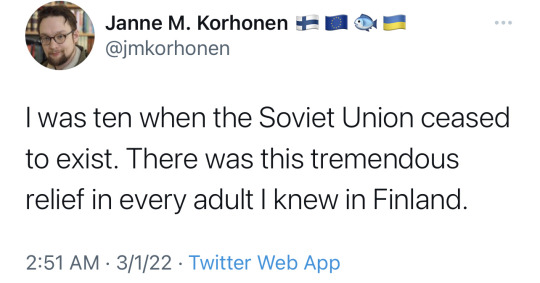

(1/?) Thank you for posting nuanced views regards NATO. I wish American left understand that when your country is not a nuclear power you learn to appreciate NATO even if it is dominated by the US. The closer one lives to a wild bear the more bear traps become appreciated. People who live nowhere near bears do not understand this. Why do they love bear trappers so much? asks the person who lives inside a giant bear trap, who has never seen a bear and not threatened by one. America you are safe!

Ask continues: “It is a matter of survival not love of the imperialism. Russia has proved repeatedly in history it is a threat to neighbors closest to her. We do not want war! After Ukraine will be Georgia, Moldova, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Putin will not stop until he is stopped. Non-nuclear countries closer to Russia wish only to be threatened no more by Putler’s Czarist ambitions and if it mean accepting NATO? So be it. Good day to you. Glory to Ukraine.”

[re: this post or this one]

Anon, I hope you are safe.

I do not personally know many immigrants from that region irl, and the handful of neighbors who I dO know, we are acquaintances at best. (A French woman and a Russian couple; all of whom still speak with the heavy accents of their native tongues. I’m dying to ask them about the invasion, but unfortunately I don’t think I know them well enough to broach the subject—just like I appreciate them not polling me, whenever the cops kill another Black person).

So this ask is, for me, a glimpse into the head of someone—other than Ukrainian citizens—who quite literally has some skin in the game, and who is directly impacted by NATO and what’s happening in Ukraine.

While I have called out American imperialism , I honestly hadn’t thought much about NATO, so I until very recently, I hadn’t formed or formulated any cogent thoughts about NATO (separate from the U.S.) one way or the other. This ask strikes me as the voice of someone who, living close to Russia, isn’t speaking from a place of privilege and isn’t being “academic” in their reasoning. It’s real for anon in a way that it isn’t for tankies who never seem to want to hold Putin accountable for his “Czarist tendencies.”

I sat on this ask for a minute because I needed to look around and see if it was at all representative of people living in non-NATO, European countries. Twitter isn’t necessarily the best place to go for samples, I know, but here is a little bit of what I found online, when someone asked to hear only from other Europeans on the subject:

I cannot vouch for anyone in the thread above bc they quite literally just popped onto my radar, because I was looking for this specific kind of discourse, but I just think that a few people calling themselves “leftists” (aka tankies) are foolishly misguided and wayyy on the wrong side of this.

I want to be extremely clear here: I am not absolving NATO or America for their unending wars or their imperialism. We can walk and chew gum at the same time, right? We can give fair and honest critiques of American colonialism and warmongering, while simultaneously addressing Putin’s history of aggressive imperialism. We should be adult enough to parse out, “America bad ≠ Russia good,” and yes, I KNOW that citizens of African countries, who are on the receiving end of NATO’s “protection” (aka, wars for oil) feel differently. And that is also a viewpoint which is valid af. We should be able to address both, without ignoring, minimizing or excusing Russia’s repeated aggression.

It’s just that the line about “people who don’t live close to bears don’t understand what it’s like to live so close to bears” really resonated with me.

And I freely admit that if Putin follows through with his threat to use tactical nukes, the increasingly real possibility of a nuclear weapons exchange between Russia and NATO will impact everyone on this planet, in a way that other current wars won’t.

I would be very interested to hear from anyone who lives in Europe, in a non-NATO country, and who has a blog that wasn’t created within the past few days.

And to the anon who sent this ask, I hope you and your loved ones are safe. If you want, please feel free to message me off anon. I fully cosign on the, “Glory to Ukraine,” sentiment. I hope Ukraine kicks Putin’s ass. 🇺🇦🇺🇦🇺🇦

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Step of a Very Long Journey.

Thoughts on the repealing of Penal Code 377A in Singapore.

After many years of activism, demonstration, education, and court appeals, the parliament of Singapore finally decided to consider the repeal of 377A earlier this year. Today, the members of parliament, after long debates, have voted on the repealing of 377A. 93 for AYE, 3 for NAY, 0 Abstain.

At first glance, this seems to call for celebrations, but before we cover the streets with rainbow flags, it is important to consider how this is only but a small tokenistic step in the right direction. I could go into analysing the parliamentary debates, the colonial history of 377A, the case study of the (deeply failing and flawed) democracy of Singapore, but emotionally and mentally, I do not think I have the space for such analyses and debates. I may be an academic in my day to day life, but the repeal of 377A and the possibilities and limitations it presents affects me as a person and I want to utilise this space to unpack my personal thoughts on the matter, divorcing my current thoughts from the abstractly theoretical.

Earlier in this blog, I wrote about 377A and how parliamentary debates and mainstream discourse in Singapore in favour of keeping the penal code has always cited ‘’family values’’ as a key reason. This discourse was not spared from the discussion of repealing 377A. While it seems like there might be cause for celebration with the repeal of 377A, the repeal was also met with commitments from many parliament members to ‘’strengthen the family unit’’. Sure, sex between gay men are no longer illegal but is sexual freedom the only human right they think we are after? If they do think so, they are ridiculously misguided. While the repeal of 377A could potentially battle some previous homophobic stigma of ‘’criminality’’, the notion of ‘’strengthening the family unit’’ implies the queer communities are excluded from ‘’family’’. Back to the discourse on ‘’family values’’, it implies we can’t form and sustain good, loving familial bonds. Even worse, queer people in this discourse are positioned as an opposition against families, as though loving bonds and belonging aren’t also deeply important to us. Surely there should be space to question and challenge the harmful heteronormative norms surrounding the notion of ‘’family’’.

While all the other issues surrounding queer rights are important to me (i.e., quality education, gender affirming care, access to housing, etc.), the issue and exclusion of queer people in Singapore from the notion of ‘’family’’ brings me much sadness for personal reasons. Despite being in a straight-presenting relationship, my partner and I are ultimately in a very queer relationship. In consideration of where to live out our lives together and raise our families, places we do consider to some extent ‘’home’’ have often been cards laid out on the table. Of these places, Singapore was amongst the deck. However, with how unfortunately cruel and institutionally homophobic is, it is very difficult to truly consider a life in Singapore where we will be happy. Furthermore, we are very clear on our desire for children in our lives and I cannot bear to subject my children to an education system that will try to box them in skirts and pants, pink and blue, and teach them harmful lessons about sex. I cannot bear to subject my children to a space where queer people are only accepted in writing but forced to hide away from the public for being ‘’too public’’. I cannot bear to have my children raised in a space that will continuously question the legitimacy of their parents’ relationship and their family-hood. So what does all these mean for the future of me and my family? I could go on but I suppose I shall another time when I feel less tired from my many messy thoughts about the situation. Until then, PinkDot SG and Heckin Unicorn (I only hyperlinked part 1 of Heckin’ Unicorn’s analyses but parts 2-5 should be easily accessible through the first one) have put up really good analyses and statements about the situation that strongly reflect my views. So perhaps check them out.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wait wdym? Do you think fic is bad?

i'm getting canceled tonight i guess.

if you actually did a good a faith interpretation of my post you know it's not really ABOUT fanfiction at all, i actually write fanfiction myself. i'm not sharing here because it's overwhelmingly bad fic that i write exclusively as wish-fulfilment or for self-projection, but at least i'm self-aware about it. i am ALSO one of the people who reads ze Books™️, although most of the academic material i consume are nonfiction, so this whole thing is particularly annoying to me. the crux of the matter is that, if you're a little younger you might've missed it, but this website was a hotbed of scalding takes like 'dante's divine comedy is literally fanfiction', 'something something is literally fanfiction' when the thing in question barely counts as a transformative work and, in fact, it weakens the definition of transformative work in itself to try to apply it to literally anything that exhibits an ounce of intertextuality. plenty of takes that are... true, but require some nuance, focused on the idea of transformative fandom as a place defined by its presence of overwhelmingly female and disproportionately queer (occasionally, though disputedly, nonwhite) content creators and the ways in which transformative fan content could be interpreted as a space of defiance to cisheteropatriarchy in the way it permeates traditional media. a third, less common but still relevant take was the focus on how certain fandoms such as trek and doctor who have a long history of involvement in real-world civil rights issues and progressive politics. so this kind of take has been the dominant view on tumblr and transformative fandom for a good decade now, perhaps longer, and the people with this kind of takes can sometimes be a little... obnoxious. and the majority of people on transformative fandom (regardless of wether or not the fandom is disproportionately composed of nonwhite individuals or not, by sheer virtue of american demographics and this site`s heaily skewed userbase, the majority will still be white) are white, and like any other space dominated by white people, fandom has often been a vehicle for white supremacy. "Stitch Media Mix" talks about this in-depth. the discourse on fandom racism and ways in which transformative fandom as a whole contribute to racialized stereotypes, hierarchies, and deeper problems within online culture has led to a lot of people with grievances with fandom, many of whom are women of color, to develop an entire online identity built around the concept of being "critical of fandom", which is a very weird thing to do with fandom is literally billions of people, not a unified demographic, and that being critical of something can mean a WIDE amount of things; which in turn has led to a lot of people insulating themselves completely from any criticism of fandom as being inherently in bad faith, which a weird thing to do when literally ANY sphere of society should be open to criticism. people taking critiques of media they consume and taking critiques of their own critiques as personal attacks are abound here and make everything worse. so a fairly recent (mid2018ish, definitely post the insanity of reylo discourse but before sarah z blew up in popularity) trend has been that people in these communities isolate more and more and the general discourse has effetively resulted in people with differing takes in fanfiction specifically but fandom as a Whole (which is, again very weird to say because fandom is not 'a Whole' because there's no unifying element to different fandoms) only interacting with each other in hostile ways. and increasingly, in my personal sphere, a lot of people are positioning themselves in the "fandom critical" (AGAIN, WEIRD THING TO SAY, WHAT DOES IT EVEN MEAN, PLEASE USE WORDS WITH PRECISION) sphere, and I tend to take that "side" myself, but i specifically do not think framing this as a team A or team B thing is useful. this culture war was in the buildup.

last week a post by a user i follow recently became popular. the post itself was a critique that i.. do not necessarily agree with. it was ultimately about the idea of easily-consumable popular media being seen as an acceptable form of exclusive media engagement by people in the "pro-fandom" sphere, and how the insidiousness of this line of thinking has to do with how capitalist media production is designed to spread, and how fandom AS A TREND, not specifically any individuals or any fanworks, can empower capitalism. the post specifically did NOT use the kindest possible words, but that was what they were trying to say. howelljenkins also has really good takes on the subject, albeit from a different angle.

anyway because this is a circular culture war, the result was as follows: 1) a bunch of pro-fandom types refuse to actually make a charitable reading of the post and insist the user in question hates fandom and thinks people under capitalism shouldn't have things that are Fun, and should Only Read Theory and keep sending anon hate to several blogs in the opposing sphere, therefore proving the point that fandom sometimes prevent people from being able to engage critically with things; 2) a bunch of anti-fandom types who defined their entire identity on hating fandom being like "haha look at these cringe people" instead of trying to understand why a demographic overwhelmingly composed of marginalized people would feel strongly to posts that use inflammatory language against an interest of theirs, thereby proving the point that most criticism of fandom is divorced from actual fan content and is vaguely defined. the reason this is a culture war that actually deserves attention (unlike most fandom culture wars, which are just really granular ship wars made into social justice issues for clout) is that, for the most part, both of these groups are mostly people with college degrees, many of whom will contirbute to academia in the coming years. fan studies is a relevant field. these discussions have repercussions in wider media criticism trends, and this is why i can't really stand it or just passively ignoring it the way i do with most other inconsequential discourse. like it's genuinely upsetting seeing almost every single tumblr user, most of whom should know better, patting themselves in the back for their inability to read things in a way that doesn't feed into preexisting cultural hostilities in fan spaces.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesbian Unintelligibility in Pre-1989 Poland

Selection from ""No one talked about it": The Paradoxes of Lesbian Identity in pre-1989 Poland, by Magdalena Staroszczyk, in Queers in State Socialism: Cruising 1970s Poland, eds. Tomasz Basiuk and Jędrzej Burszta, 2021

The question of lesbian visibility is pertinent today because of the limited number of lesbian-oriented activist events and cultural representations. But it presents a major methodological problem when looking at the past. That problem lies in an almost complete lack of historical sources, something partly mended with oral history interviews, but also in an epistemological dilemma. How can we talk about lesbians when they did not exist as a recognizable category? What did their (supposed) non-existence mean? And should we even call those who (supposedly) did not exist “lesbians”?

To illustrate this problem, let me begin with excerpts from an interview I conducted for the CRUSEV project [a study of queer cultures in the 1970s]. My interlocutor is a lesbian woman born in the 1950s, who lived in Cracow most of her life:

“To this very day I have a problem with my brothers, as I cannot talk to them about this. They just won’t do it, I would like to talk, but. . . . They have this problem, they lace up their mouths when any reference is made to this topic, because they were raised in that reality [when] no one talked about it. It was a taboo. It still is. ... I was so weak, unable to take initiative, lacking a concept of my own life—all this testifies to the oppression of homosexual persons, who do not know how to live, have no support from [others], no information or knowledge learned at school, or from a psychologist. What did I do? I searched in encyclopaedias for the single entry, “homosexuality.” What did I learn? That I was a pervert. What did it do to me? It only hurt me, no? Q: Was the word lesbian in use? Only as a slur. Even my mother used it as an offensive word. When she finally figured out my orientation, she said the word a few times. With hatred. Hissing the word at me.”

The woman offers shocking testimony of intense and persistent hostility towards a family member—sister, daughter—who happens to be a lesbian. The brothers and the mother are so profoundly unable to accept her sexuality that they cannot speak about it at all, least of all rationally. The taboo has remained firmly in place for decades. How was it maintained? And, perhaps more importantly, how do we access the emotional reality that it caused? The quotes all highlight the theme of language, silence, and something unspeakable. Tabooization implies a gap in representation, and the appropriate word cannot be spoken but merely hissed out with hatred.

Popular discourse and academic literature alike address this problem under the rubric of “lesbian invisibility” (Mizielińska 2001). I put forward a different conceptual frame, proposing to address the question of lesbian identity in pre-1989 Poland not in terms of visibility versus invisibility, but instead in terms of cultural intelligibility versus unintelligibility. The former concepts, which have a rich history in discussions of pre-emancipatory lesbian experience, presume an already existing identity that is self-evident to the person in question. They assume the existence of a person who thinks of herself as a lesbian. One then proceeds to ask whether or not this lesbian was visible as such to others, that is, whether others viewed her as the lesbian she knew she was. Another assumption behind this framing is that the woman in question wished to be visible although this desired visibility had been denied her. These are some of the essentializing assumptions inscribed in the concept of (in)visibility. Their limitation is that they only allow us to ask whether or not the lesbian is seen for who she feels she is and wishes to be seen by others.

By contrast, (un)intelligibility looks first to the social construction of identity, especially to the constitutive role of language. To think in those terms is to ask under what conditions same-sex desire between women is culturally legible as constitutive of an identity. So, instead of asking if people saw lesbians for who they really were, we will try to understand the specific epistemic conditions which made some women socially recognizable to others, and also to themselves, as “lesbians.” This use of the concept “intelligibility” is analogous to its use by Judith Butler in Gender Trouble, as she explains why gender conformity is key to successful personhood[...].

For Butler, cultural intelligibility is thus an aspect of the social norm, as it corresponds to “a normative ideal.” It is one of the conditions of coherence and continuity requisite for successful personhood. In a similar vein, to say that lesbians in the People’s Republic of Poland were not culturally intelligible is of course not to claim that there were no women engaged in same-sex romantic and erotic relationships—such a conclusion would be absurd, as well as untrue. It is, rather, to suggest that “lesbian” was not a category of personhood available or, for that matter, desirable to many nonheteronormative women. The word was not in common use and it did not signify to them the sort of person they felt they were. Nor was another word readily available, as interlocutors’ frequent periphrases strongly suggest, for example, “I cannot talk to them about this. ... They ... lace up their mouths when any reference is made to this topic” (my emphases).

Interviews conducted with women for the CRUSEV project are filled with pain due to rejection. So are the interviews conducted by Anna Laszuk, whose Dziewczyny, wyjdźcie z szafy (Come Out of the Closet, Girls! 2006 ) was a pioneering collection of herstories which gave voice to non-heteronormative Polish women of different ages, including those who remember the pre-1989 era. Lesbian unintelligibility is arguably a major theme in the collection. The pain caused by the sense of not belonging expressed by many illustrates that being unintelligible can be harmful. At the same time, unintelligibility had some practical advantages. The main among them was relative safety in a profoundly heteronormative society. As long as things went unnamed, a women-loving woman was not in danger of stigmatization or social ostracism.

Basia, born in 1939 and thus the oldest among Laszuk’s interviewees, offers a reassuring narrative in which unintelligibility has a positive valence:

“I cannot say a bad word about my parents. They knew but they did not comment. . . . My parents never asked me personal questions, never exerted any kind of pressure on me to get married. They were people of great culture, very understanding, and they quite simply loved me. They would meet my various girlfriends, but these were never referred to as anything but “friends” (przyjaciółki). Girls had it much easier than boys because intimacy between girls was generally accepted. Nobody was surprised that I showed up with a woman, invited her home, held her hand, or that we went on trips together.” (Laszuk 2006, 27)

The gap between visceral knowing and the impossibility of naming is especially striking in this passage. The parents “knew” and Basia knew that they knew, but they did not comment, ask questions, or make demands, and Basia clearly appreciates their silence as a favour. To her, it was a form of politeness, discreetness, perhaps even protectiveness. The silence was, in fact, a form of affectionate communication: “they quite simply loved me.”

Another of Laszuk’s interviewees is Nina, born around 1945 and 60 years old at the time of the interview. With a certain nostalgia, Nina recalls the days when certain things were left unnamed, suggesting that there is erotic potential in the unintelligibility of women’s desire. Laszuk summarizes her views:

“Nina claims that those times certainly carried a certain charm: erotic relationships between women, veiled with understatement and secrecy, had a lot of beauty to them. Clandestine looks were exchanged above the heads of people who remained unaware of their meaning, as women understood each other with half a gesture, between words. Nowadays, everything has a name, everything is direct.” (Laszuk 2006, 33)

A similar equation between secrecy and eroticism is drawn by the much younger Izabela Filipiak, trailblazing author of Polish feminist fiction in the 1990s and the very first woman in Poland to publicly come out as lesbian, in an interview for the Polish edition of Cosmopolitan in 1998. Six years later, Filipiak suggested a link between things remaining unnamed and erotic pleasure, and admitted to a certain nostalgia for this pre-emancipatory formula of lesbian (non)identity. Her avowed motivation was not the fear of stigmatization but a desire for erotic intensity:

“When love becomes passion in which I lose myself, I stop calculating, stop comparing, no longer anchor it in social relations, or some norm. I simply immerse myself in passion. My feelings condition and justify everything that happens from that point on. I do not reflect upon myself nor dwell on stigma because my feeling is so pure that it burns through and clears away everything that might attach to me as a woman who loves women.” (Kulpa and Warkocki 2004)

Filipiak acknowledges the contemporary, “postmodern” (her word) lesbian identity which requires activism and entails enumerating various kinds of discrimination. But paradoxically—considering that she is the first public lesbian in Poland—she speaks with much more enthusiasm about the “modernist lesbians” described by Baudelaire:

“They chose the path of passion. Secrecy and passion. Of course, their passion becomes a form of consent to remain secret, to stay invisible to others, but this is not unambivalent. I once talked to such an “oldtimer” who lived her entire life in just that way and she protested very strongly when I made a remark about hiding. Because, she says, she did not hide anything, she drove all around the city with her beloved and, of course, everyone knew. Yes, everyone knew, but nobody remembers it now, there is no trace of all that.” (Kulpa and Warkocki 2004)

Cultural unintelligibility causes the gap between “everyone knew” and “nobody remembers” but it is also the source of excitement and pleasure. For Filipiak’s “old-timer” and her predecessors, Baudelaire’s modernist lesbians, the evasion, or rejection, of identity and the maintaining of secrecy is the path of passion. Crucially, these disavowals of identity mobilize a discourse of freedom rather than hiding, entrapment, or staying in the closet. The lack of a name is interpreted as an unmooring from language and a liberation from its norms.

Needless to say, cultural unintelligibility may also lead to profound torment and self-hatred. In the concept of nationhood generated by nationalists and by the Catholic Church in Poland, lesbians (seen stereotypically) are double outsiders whose exclusion from language is vital.[1] A repentant homosexual woman named Katarzyna offers her testimony in a Catholic self-help manual addressing those who wish to be cured of homosexuality. (It is irrelevant for my purpose whether the testimony is authentic; my interest is in the discursive construction of lesbian identity as literally impossible and nonexistent.) Katarzyna speaks about her search for love, her profound sense of guilt and her disgust with herself. The word “lesbian” is never used; her homosexuality is framed as confusion and as straying from her true desire for God. The origin of the pain is the woman’s unintelligibility to herself:

“Only I knew how much despair there was in my life on account of being different. First, there was the sense of being torn apart when I realized how different my desires were from the appearance of my body. Despite the storm of homosexual desire, I was still a woman. Then, the question: What to do with myself? How to live?” (Huk 1996, 121)

A woman cannot love other women—the subject knows this. We can speculate that her knowledge is due to her Catholic upbringing; she has internalized the teaching that homosexuality is a sin, and thus untrue and not real. The logic of the confession is overdetermined: the only way for her to become intelligible to herself is to abandon same-sex desire and turn to God, and through him to men. Church language thus frames homosexuality as chaos: it is a disordered space where no appropriate language can obtain. Within this frame, unintelligibility is anything but erotic. It is rather an instrument of shaming and, once internalized, a symptom of shame.

For many, the experience of unintelligibility is moored in intense heteronormativity, without regard to Church teachings or the language of national belonging. Struggling with the choice between social intelligibility available to straights and leading an authentic life outside the realm of intelligibility, one CRUSEV interlocutor, aged 67, describes her youth in 1960s and 1970s:

“I always knew I was a lesbian ... and if I am one, then I will be one. Yes, in that sense. And not to live the life of a married woman, mother and so on. This life wasn’t my life at all. However, as I said, it was fine in an external sense. So calm and well-ordered: a husband, nice children, everything, everything. But it was external, and my life was not my life at all, it wasn’t me.”

She thus underscores her internal sense of dissonance, a felt incompatibility with the social role she was playing. The role model of a wife and mother was available to her, but a lesbian role model was not.

The discomfort felt at the unavailability of a role model may have had different consequences. Another CRUSEV interviewee, aged 62, describes her impulse to change her life so as to authentically experience her feelings for another woman, in contrast to that woman’s ex:

“She visited me a few times, and it was enough that I wrote something, anything ... [and] she would get on the train and travel across the country. There were no telephones then, during martial law. Regardless of anything, she would be there. And at one point I realized that I ... damn, I loved her. ... She broke up with her previous girlfriend very violently—this may interest you—because it turned out that the girl was so terribly afraid of being exposed and of some unimaginable consequences that she simply ran away.”

The fear of exposure, critically addressed by the interlocutor, was nonetheless something she, too, experienced. She goes on to speak of “hiding a secret” and “stifling” her emotions.

A concern with leading an inauthentic life resurfaces in the account of the afore-quoted woman, aged 67:

“I couldn’t reveal my secret to anyone. The only person who knew was my friend in Cracow. I led such a double life, I mean. ... It is difficult to say if this was a life, because it was as if I had my inner spirituality and my inner world, entirely secret, but outside I behaved like all the other girls, so I went out with some boys. ... It was always deeply suppressed by me and I was always fighting with myself. I mean, I fell in love [with women] and did everything to fall out of love [laughter]. On and on again.”

Her anxiety translates into self-pathologizing behaviour:

“In 1971 I received my high school diploma and I was already . . . in a relationship of some years with my high school girlfriend. . . . But because we both thought we were abnormal, perverted or something, somehow we wanted to be cured, and so she was going to college to Cracow, and I to Poznań. We engaged in geographic therapy, so to speak.”

The desire to “be cured” from homosexuality recurs in a number of interviews. Sometimes it has a factual dimension, as interlocutors describe having undergone psychotherapy and even reparative therapy—of course, to no avail.

Others decide to have a relationship with a woman after years spent in relationships with men. Referring to her female partner of 25 years, who had previously been married to a man, one of my interlocutors suggests that her partner had been disavowing her homosexual desires for many years before the two women’s relationship began: “the truth is that H. had struggled with it for more than 20 years and she was probably not sure what was going on.” Despite this presumed initial confusion, the women’s relationship had already lasted for more than 25 years at the time I conducted the interview.

Recognizing one’s homosexual desires did not necessarily have to be difficult or shocking. It was not for this woman, aged 66 at the time of the interview:

“It was obvious to me. I didn’t, no, no, I didn’t suppress it, I knew that [I was going], “Oh, such a nice girl, I like this one, with this one I want to be close, with that one I want to talk longer, with that one I want to spend time, with that one I want, for example, to embrace her neck or grab her hand”.”

Rather, what came as a shock was the unavailability of any social role or language corresponding to this felt desire that came as a shock. The woman continues:

“It turned out that I couldn’t talk to anyone about it, that I couldn’t tell anyone. I realized this when I grew up and watched my surroundings, family, friends, society. I saw that this topic was not there! If it’s not there, how can I get it out of myself? I wasn’t so brave.”

The tabooization of homosexuality—its unintelligibility—is a recurring thread in these accounts; what varies is the extent to which it marred the subjects’ self-perception.

#lgbtq history#poland#lesbian history#unintelligibility#lesbian unintelligibility#this might be deleted in the future so read it while you can

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The University of Rhode Island is distancing itself from an endowed professor of gender and women’s studies who recently wrote about what she calls the “trans-sex fantasy.” “The ‘gender identity’ movement is canceling people’s free speech and academic freedom for anyone who doesn’t fall in line, speaks out in opposition, or even calls for the right to debate,” the professor, Donna Hughes, wrote in a recent essay for 4W, a “fourth-wave” feminist website. “People are losing social media accounts or being fired for ‘misgendering’ someone or not ‘affirming’ a person’s’ claimed ‘gender identity.’”In the meantime, Hughes said, “an increasing number of teens are signing-up for harmful treatments with no one, not even parents, being allowed to intervene.” Responding to criticism of the essay, URI this week released a statement saying that it “does not support statements and publications by Professor Donna Hughes that espouse anti-transgender perspectives and recognize that such discourse can cause pain and discomfort for many transgender individuals. The university is committed to transgender rights and the need to eliminate all forms of discrimination and violence aimed at transgender individuals and the LGBTQIA+ community.”At the same time, URI said, faculty members have the “same rights, obligations, and responsibilities as other American citizens. The university honors and respects the right to freedom of speech under the First Amendment for all citizens, including our faculty, without censorship or retaliation.”

URI said it also recognizes that its professors “have the general right to ‘academic freedom’ in their teaching and scholarship.” These rights are “not boundless, however,” the university said, “and should be exercised responsibly with due regard for the faculty member’s other obligations, including their obligations to the university’s students and the university community.”Hughes said via email that the university’s statement is an “egregious affront to my free speech and academic freedom rights.” It’s “clearly established that a public employee has the right to speak as a private citizen on matters of public concern, which is precisely what I have done.”

Samantha Harris, Hughes’s lawyer, said that “like faculty around the country who express views that are out of step with the prevailing orthodoxy on campus, Professor Hughes has become the target of an online pressure campaign.” This involves an effort to get students to file complaints about her with the university and “take her down,” Harris explained, quoting one Twitter user.URI said its administration, College of Arts and Sciences and department of gender and women’s studies are now "working to support our students and the community as we move through -- and learn from -- this situation.”

Hughes, the Eleanor M. and Oscar M. Carlson Endowed Chair of Gender and Women’s Studies at URI, has long written about controversial issues such as prostitution and taken at times controversial stances on them: whereas some gender studies experts believe that sex work is legitimate labor that women can freely choose, Hughes believes there’s a fine line between sex work and sex trafficking and that legalizing prostitution helps only pimps and johns, not sex workers.Though divisive, most of Hughes’s arguments have fallen within the accepted realms of academic debate. This foray into gender identity discourse is more fraught, as many trans activists, allies and gender studies scholars say that questioning to what degree trans women are women is transphobic and bigoted. Other scholars have pushed back on that notion as censorship.The most contentious academic arguments tend to center on trans women, not trans men, as women and trans people -- but not cisgender men -- have been historically marginalized. Critics such as Hughes, who are sometimes derided as trans-exclusionary radical feminists, or TERFs, worry that the biological category of woman is being erased, while trans women worry about further marginalization via exclusion from female spaces.

A ‘Dystopia’Hughes wrote in her essay, for instance, that the “biological category of sex, particularly women’s sex, is being smashed. Women and girls are expected to give up their places of privacy such as restrooms, locker rooms, and even prison cells. When biological males identify as trans-women, they can compete in women’s and girls’ sports.”In this “dystopia,” Hughes continued, “basic biological words like breast and vagina are replacedby misogynistic, trans-sex/trans-gender language so that a female has a ‘front hole’ instead of a vagina; females ‘chest feed’ instead of breastfeed. All references to women disappear into terms such: ‘people who menstruate,’ ‘people with uteruses,’ ‘a pregnant person,’ or ‘a birthing parent.’”These “redefinitions are hatred targeted at women’s bodies and their rights,” Hughes said, noting that there’s no comparable push to rename men’s body parts.

Perhaps most controversially, Hughes wrote that young people are now “guided into hormonal and surgical horrors that de-sex them.” Through these interventions, “girls’ female bodies are permanently scarred and destroyed.” On Twitter, Hughes has retweeted content about women regretting getting "top" surgery to affirm a male gender identity from which they'd since detransitioned.Scholars in Britain have arguably been even more engaged in these topics in recent years, with the government there considering a gender self-recognition plan. Some feminist academics in Britain, including Kathleen Stock, opposed the plan on the grounds that it would inflict unintended harm. One of these commonly cited unintended harms is that abandoning sex-exclusive spaces would expose women to male violence. Trans activists point out that trans people face disproportionate levels of violence.The British government recently abandoned the self-recognition plan. President Biden, meanwhile, has already signed an executive order on preventing and combating discrimination on the basis of gender identity or sexual orientation. Many applauded this action. But Hughes wrote that it means the “trans-sex fantasy has imagined -- and is enacting -- a world in which how a man feels is more real than his actual reality.”This makes the political left not so different from conspiracy and disinformation junkies on the far right, she said.

On Twitter, Hughes has also shared criticism of the proposed federal Equality Act, which would redefine sex to include gender identity and sexual orientation.Via email, Hughes said it’s “just sad that we have reached a point in society where difficult issues cannot be freely and openly discussed without resort to personal attacks and calls for censorship.”The marketplace of ideas, she added, “has broken down and increasingly, university faculty are terrified to speak out on a wide range of important issues for fear that -- as seems to be happening here -- they will draw criticism from their students and their institution will throw them under the bus.”Hughes is a founding member of the Academic Freedom Alliance, which launched recently to defend professors’ academic freedom from attacks from the political left and right. Her case, she said, demonstrators “precisely why the AFA was founded and is so necessary.”

Harris, Hughes’s lawyer, said that URI is “obviously within its rights to criticize” Hughes’s views, but that the university’s statement seems to imply that the article may not be protected by the First Amendment “because she somehow failed to show appropriate restraint in the expression of her opinion. This simply is not the case.”The article is indeed protected speech, “quite apart from questions of academic freedom,” because Hughes was expressing her views as a citizen on a matter of public concern, Harris said. Hughes’s article didn’t note her affiliation to URI, and the fact that she may be “well-versed in the subject by virtue of her work does not transform this into speech made within the context of her employment.”

Trans History Month admits they include stories from Trans Nazis but a woman speaking up for women’s rights must be censored.

43 notes

·

View notes

Link

When the idea that a woman could have a penis was no longer a privileged insight of the academic elite but had gone mainstream, I remarked to my friend, “How long before we have to affirm the furries?” At the time I was joking, but after reading Kathy Rudy’s article “LGBTQ…Z?” in Hypatia in which she claims to “draw the discourses around bestiality/zoophilia into the realm of queer theory” I’m starting to wonder if my joke isn’t that far off. After all, there was a time when the idea of a man becoming a woman was a joke—as in this clip from Monty Python’s comedy The Life of Brian.

What Duke University professor Kathy Rudy seems to realize by arguing we should add “Z” (zoophilia) to the queer alphabet soup is that a great way to have a successful career in academia is to bring postmodern gobbledygook into absurd combinations with anything and everything.

…

I will hand it to Rudy, her article is at least comprehensible, even if it’s just as insane. Rudy begins by noting that humans who “kill animals, force them to breed with each other, eat them, surround them, train them, hunt them, nail them down and cut them open for science” are considered “normal, functioning members of society. Yet having sex with animals remains an almost unspeakable anathema.”

…

While some might conclude that, since we wouldn’t shag a pig, we also shouldn’t confine one to a gestation crate, Rudy’s reasoning seems to be that if we already force terrible things on animals, then why not also screw them? If you’re a cow, having a human copulate with you can’t be as bad as going to the slaughterhouse, right? Besides, Fido already humps my leg so why don’t I hump him?

Technically, Rudy claims “my argument is not for or against humans having sex with animals, but is a meditation on both the elusive nature of sex itself and the subjectivities of human versus nonhuman animals.” She never explicitly promotes sex with animals, but considering that the entire point of the article is to call into question the taboo against having sex with animals, well…

It’s as if I said I’m not advocating for pedophilia but then proceed to undermine all the reasons for being against pedophilia. “Why not?” might not be as strong as “you must” but it leads to the same outcome, namely, radical permission.

As is often the case with academic postmodernism, the claims being made become less clear the more the author writes:

“Put differently, queer theory teaches us that it's not really a question of whether we have ‘sex’ with animals; rather it's about recognizing and honoring the affective bonds many of us share with other creatures. Those intense connections between humans and animals could be seen as revolutionary, in a queer frame. But instead, pet love is sanitized and rendered harmless by the presence of the interdict against bestiality. The discourses of bestiality and zoophilia form the identity boundary that we cannot pass through if we want our love of animals to be seen as acceptable.”

Rudy’s elusive, wishy-washy prose is a common rhetorical tactic. The goal is to avoid clearly committing to an argument so that one can simultaneously promote radical nuttiness while removing oneself from the burden of defending it. After all, if the claim really were as basic as “we love our pets but not in a sexual way” then the article wouldn’t be, as Rudy puts it, “revolutionary.”

The only way the article can be truly “transgressive” is for her to argue that our love for animals is already sexual or should become sexual. After all, Rudy seems uncertain as to whether she is sexually attracted to her own dogs:

“I know I love my dogs with all my heart, but I can’t figure out if that love is sexually motivated.”

For some reason, I’ve never grappled with this problem, but then again, I’m not versed in Queer theory.

…

Indeed, what is the difference between inserting a piece of bread into a toaster and penetrative sex? According to postmodernism, nothing at all! As Rudy explains:

“The widespread social ban on bestiality rests on a solid notion of what sex is, and queer theory persuasively argues we simply don't have such a thing. The interdict against bestiality can only be maintained if we think we always/already know what sex is. And, according to queer theory, we don’t.”

Despite earlier claiming that she is not advocating for sex with animals, Rudy has just provided us with an indirect argument for it. She states that we can only maintain a ban on sex with animals if we know what sex is. She next states that queer theory has proven that we don’t know what sex is. Therefore, we cannot ban sex with animals. She suggests her indirect argument again at the end of the article by masking it in the form of a question:

“But without a coherent and agreed upon definition of sex (which queer theory persuasively argues is impossible), the line between ‘animal lover’ and zoophile is not only thin, it is nonexistent. How do we know beforehand whether loving them constitutes ‘sex,’ and how can such sex be so dangerous if it so nebulous and undefined?”

Not only is it false that we have no idea what sex is, but it is also false to say that we require a taxonomy of every kind of sexual feeling before we can forbid certain acts (such as coitus) with animals (or children and the cognitively disabled, such as Chris Chan’s mother with dementia).

I may not be able to verbally capture the feeling of sexual desire or pleasure any more than I can define pain or joy or sadness. It’s something I know from experience. What I can say for sure is that what I felt kissing my grandma’s cheek is definitely not in the same category as what I felt kissing my boyfriend. Rudy may be unclear as to whether she is turned on by a slurp from her dog, but I personally have never felt confusion on the matter.

…

Yet, the true perversion, according to Rudy, is not to lust after camels, dogs, parakeets or naked mole rats but to set up the sexual boundary between humans and animals in the first place:

“Put differently, both animal rights (3) and psychosocial perspectives [which view desire for animals as mental illness] (4) do not believe that borders can be crossed. Queer theory, on the other hand, tells us that few of us have stable identities anymore, that borders are always crossed. We're all changing, shifting, splitting ourselves up this way and that. It labels these processes ‘hailing,’ ‘suturing,’ and ‘interpolation’; where once we saw ourselves affiliated in one way, a new interpretive community emerges to capture our passions and move us differently. I am asking the reader to entertain the possibility that the same kinds of shifts and disruptions happen with categories like ‘human,’ ‘rabbit,’ ‘ape,’ or ‘dog.’”

And no woke paper would be complete without the accusation of violence:

“Both positions [animal rights activists and bestialists] oppose sex with animals, and in doing so they perform a kind of violence on animals by lumping them all together into one seamless identity.”

That’s right. Physically violating an animal does not constitute violence. Words do. Especially when those words reject postmodern queer theory.

…

Unlike the many women who have been cancelled for claiming that males aren’t women, Rudy’s August 2012 article (republished March 2020) for Hypatia did not result in her being fired, censored, or otherwise deplatformed.

It’s not as if no one came across her article either. According to Altmetric, Rudy’s article is in the “top 5% of all research outputs scored by Altmetric” and is “One of the highest-scoring outputs from this source (#1 of 704)” and has an Altmetrics attention score in the 99th percentile.

When Rebecca Tuvel wrote a paper for Hypatia suggesting that the same assumptions that ground transgenderism could be used to support transracialism, scholars demanded Hypatia retract the article and the journal's Facebook page posted an apology on behalf of the associate editors. Rudy, on the other hand, was invited to deliver the commencement speech for North Carolina Service Dogs in December 2012.

We must remember that the word “transgressive” has relative, not absolute, meaning. What is considered “normal” defines what is considered “transgressive.” If queer theory articles on bestiality result in publication and validation, then is Rudy truly, in her words, “transgressive”? Or is Hypatia, rather, representative of a new establishment norm that is just as desirous of punishing transgressors—now in the form of TERFs and other enemies of the postmodern left—as the old establishment was eager to fire and ostracize homosexuals? As The Who sang, “Meet the new boss / Same as the old boss.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

AO3 discourse is so fucking exhausting. I love AO3, I have given money to AO3, it has helped me with distractions when my life was garbage. But it is fucking exhausting to watch over and over again as some people try to explain why AO3 as it was originally set up has some flaws and then for other people to be like BUT WE WERE PERSECUTED AND AO3 SAVED US! And then other people are like, but it was never meant to be set in stone, we are supposed to be able to adapt and change it as our needs evolve, and then other people are like, BUT IT'S AN ARCHIVE! Except that isn't even an argument because archives, like anything else, do not exist or operate in a vacuum, but okay. And then fans of color ask for some protections or even some consideration and AO3 does not respond for years, and whenever those same fans talk about feeling ignored or alone or excluded or unsafe, someone in the comments will be like 'actually we at the OTW are dealing with it, progress is just slow and also we never told anyone about it for some reason.' And then someone else on AO3 will act in bad faith because that is what humans do--this ain't a utopia because those are not real--and everyone will get mad at each other or AO3 and set off another round of discourse. Someone will start screaming about 'antis' and 'fandom cops' only it feels like those terms mean different things to different people, and while slippery slope arguments are good and we should have them, it might also be worth examining what is at the heart of all those varied 'anti' arguments because they don't seem to be going anywhere. Absolutely art for art's sake and freedom of the imagination and all that, but also respect for your fellow human beings??? Art does not rank higher than your humanity?? And yes, if you create or contribute to an archive that wins awards and you claim that fanfiction compares to high literature and it offers feminist or queer liberation than you have to also accept that it will be studied and critiqued as an art form, as a political and cultural statement. You cannot have one without the other. Yes your work is free but it is public and it cultural and it is political, because that is life, and as such, some nerds are going to want to talk about it and discuss trends and tropes and meaning. That's what happens when work matters. But then someone else will be like BUT PURITY CULTURE!!! and/or FANS SHOULD SET THE TONE, NOT THE ARCHIVE!!! and, like, I don't see that happening anywhere because even off AO3 discussions seem to lack nuance or anything resembling nuance to the point where I have to assume some of it is deliberate but by then the screaming has started again.

And anyway. Archives are run by people, and people are flawed and make choices and have biases whether they know it or not. Institutions, even helpful and revolutionary ones, should not be worshipped. Fans DO need to start making racism obviously unwelcome in their fandoms but that means taking long, uncomfortable looks at themselves first. If you say your fanfiction or fanart has personal or cultural value as art enough for you to defend dark themes or whatever, then it will also be judged on those same values.

Also, academic criticism and individual critique of an individual story are different things. Criticism of tropes and trends is not censorship.

#don't reblog i am just tired#some fandom people need to grow up and or learn to comprehend words#some other people need to realize that we are not all using the same cultural dictionary#AND STOP WORSHIPING INSTITUTIONS!#THEY ARE RUN BY PEOPLE!#AND PEOPLE ARE FLAWED!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text