#Japanese government sources

Text

#Self-Defense Forces#SpaceX#Starlink#Satellite constellation#Trial basis#Japanese government sources#Communication capabilities#China#Russia#Attack satellites#High-speed communication service#U.S. space development company#U.S. military satellites#X-band communication satellites#Geostationary orbit#Private-sector satellite constellation#Ground-based jammers#Contingency#Operational issues#Military technology#National security#japan#tokyo#investment

0 notes

Text

found a kirby fanmanga series that does a very deep dive into the lore of forgotten land and im inhaling it all. also all the waddle dees are so so so autistic

#linked in source#its all japanese. as always. sowwy </3#sphere.txt#links.orb#LOVEEEEEEEE the characterizations in this one. intelligence (read 'autism') is off the charts#the handling of language is very very interesting too#im as big of a fan of cute wanya wanya poyo poyo silly whimsical kirby characters as the next person#but it just really gets me when like. for example#magolor asks kirby about the implications of giving the animals the concept of civilization (government trade infrastructure etc)#and warns that history will repeat itself. to which kirby gives an equally intelligent but also very trusting answer#like YESSSS TALK MORE ABOUT PHILOSOPHY. LINGUISTICS. ENGINEERING. FOLKLORE <-those are all in the series btw#its such a combo hit for me i love it#also their interpretation of the differences in kinds of magic that magolor (魔術) and marx (魔法) use is so cool....#inserts directly into brain#also also!!!! suzie (susie?? i forgor) characterization is so on point

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naming International POC Characters: Do Your Research.

This post is part of a double feature for the same ask. First check out Mod Colette's answer to OP's original question at: A Careful Balance: Portraying a Black Character's Relationship with their Hair. Below are notes on character naming from Mod Rina.

~ ~ ~

@writingraccoon said:

My character is black in a dungeons and dragons-like fantasy world. His name is Kazuki Haile (pronounced hay-lee), and his mother is this world's equivalent of Japanese, which is where his first name is from, while his father is this world's equivalent of Ethiopian, which is where his last name is from. He looks much more like his father, and has hair type 4a. [...]

Hold on a sec.

Haile (pronounced hay-lee), [...] [H]is father is this world’s equivalent of Ethiopian, which is where his last name is from.

OP, where did you get this name? Behindthename.com, perhaps?

Note how it says, “Submitted names are contributed by users of this website. Check marks indicate the level to which a name has been verified.” Do you see any check marks, OP?

What language is this, by the way? If we only count official languages, Ethiopia has 5: Afar, Amharic, Oromo, Somali, & Tigrinya. If we count everything native to that region? Over 90 languages. And I haven't even mentioned the dormant/extinct ones. Do you know which language this name comes from? Have you determined Kazuki’s father’s ethnic group, religion, and language(s)? Do you know just how ethnically diverse Ethiopia is?

~ ~ ~

To All Looking for Character Names on the Internet:

Skip the name aggregators and baby name lists. They often do not cite their sources, even if they’re pulling from credible ones, and often copy each other.

If you still wish to use a name website, find a second source that isn’t a name website.

Find at least one real life individual, living or dead, who has this given name or surname. Try Wikipedia’s lists of notable individuals under "List of [ethnicity] people." You can even try searching Facebook! Pay attention to when these people were born for chronological accuracy/believability.

Make sure you know the language the name comes from, and the ethnicity/culture/religion it’s associated with.

Make sure you understand the naming practices of that culture—how many names, where they come from, name order, and other conventions.

Make sure you have the correct pronunciation of the name. Don’t always trust Wikipedia or American pronunciation guides on Youtube. Try to find a native speaker or language lesson source, or review the phonology & orthography and parse out the string one phoneme at a time.

Suggestions for web sources:

Wikipedia! Look for: “List of [language] [masculine/feminine] given names,” “List of most common [language] family names,” “List of most common surnames in [continent],” and "List of [ethnicity] people."

Census data! Harder to find due to language barriers & what governments make public, but these can really nail period accuracy. This may sound obvious, but look at the year of the character's birth, not the year your story takes place.

Forums and Reddit. No really. Multicultural couples and expats will often ask around for what to name their children. There’s also r/namenerds, where so many folks have shared names in their language that they now have “International Name Threads.” These are all great first-hand sources for name connotations—what’s trendy vs. old-fashioned, preppy vs. nerdy, or classic vs. overused vs. obscure.

~ ~ ~

Luckily for OP, I got very curious and did some research. More on Ethiopian & Eritrean naming, plus mixed/intercultural naming and my recommendations for this character, under the cut. It's really interesting, I promise!

Ethiopian and Eritrean Naming Practices

Haile (IPA: /həjlə/ roughly “hy-luh.” Both a & e are /ə/, a central “uh” sound) is a phrase meaning “power of” in Ge’ez, sometimes known as Classical Ethiopic, which is an extinct/dormant Semitic language that is now used as a liturgical language in Ethiopian churches (think of how Latin & Sanskrit are used today). So it's a religious name, and was likely popularized by the regnal name of the last emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie (“Power of the Trinity”). Ironically, for these reasons it is about as nationalistically “Ethiopian” as a name can get.

Haile is one of the most common “surnames” ever in Ethiopia and Eritrea. Why was that in quotes? Because Ethiopians and Eritreans don’t have surnames. Historically, when they needed to distinguish themselves from others with the same given name, they affixed their father’s given name, and then sometimes their grandfather’s. In modern Ethiopia and Eritrea, their given name is followed by a parent’s (usually father’s) name. First-generation diaspora abroad may solidify this name into a legal “surname” which is then consistently passed down to subsequent generations.

Intercultural Marriages and Naming

This means that Kazuki’s parents will have to figure out if there will be a “surname” going forward, and who it applies to. Your easiest and most likely option is that Kazuki’s dad would have chosen to make his second name (Kazuki’s grandpa’s name) the legal “surname.” The mom would have taken this name upon marriage, and Kazuki would inherit it also. Either moving abroad or the circumstances of the intercultural marriage would have motivated this. Thus “Haile” would be grandpa’s name, and Kazuki wouldn’t be taking his “surname” from his dad. This prevents the mom & Kazuki from having different “surnames.” But you will have to understand and explain where the names came from and the decisions dad made to get there. Otherwise, this will ring culturally hollow and indicate a lack of research.

Typically intercultural parents try to

come up with a first name that is pronounceable in both languages,

go with a name that is the dominant language of where they live, or

compromise and pick one parent’s language, depending on the circumstances.

Option 1 and possibly 3 requires figuring out which language is the father’s first language. Unfortunately, because of the aforementioned national ubiquity of Haile, you will have to start from scratch here and figure out his ethnic group, religion (most are Ethiopian Orthodox and some Sunni Muslim), and language(s).

But then again, writing these characters knowledgeably and respectfully also requires figuring out that information anyway.

~ ~ ~

Names and naming practices are so, so diverse. Do research into the culture and language before picking a name, and never go with only one source.

~ Mod Rina

#asks#language#languages#linguistics#east africa#african#immigration#ethiopian#names#naming#research#resources#writeblr#character names#character name ideas#rina says read under the cut. read it

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some differences between modern self-reported supernatural encounters from America vs. Japan, based on my general observations from perusing hundreds of each.

(disclaimer: thanks to the language barrier and all, this is kinda by necessity comparing American stuff from a pretty wide array of sources vs. Japanese stuff that's been put into text on the internet. And then both sets mostly reach me through curators with their own agendas. So don't consider this a 100% representative sample or anything.)

American stuff semi-regularly gets into 'I know it wasn't sleep paralysis and here's why' vs. Japanese stuff seems to have mostly settled on 'sleep paralysis is, itself, a symptom of paranormal things.'

Japanese has the very handy concept of reikan, whereas the idea that only some people can see most ghosts exists in the American side, but is far less prevalent.

The American side absolutely loves UFOs and cryptids, whereas Japan barely touches the former and goes pretty light on the latter.

Meanwhile, ghosts from self-reported American stuff rarely get scarier than 'yeah it moved some stuff around and I saw a bloody guy in the mirror' whereas Japan will readily go into 'here is a list of my friends who got murdered by this ghost, and I'm next.'

The type of people who write American ones seem to be much more willing to talk about, or simply more involved with, alt spirituality stuff, so you're way more likely to get 'and the ghost didn't go away even after I did a cleansing ceremony with my crystals' or whatever.

Similarly, American ones are much more likely to end with roughly 'and it's bullshit that the government/religion/skeptics/whatever are hiding this from us.'

On the other hand, going to monks/priests is practically a staple on the Japanese side, but surprisingly few (modern) American stories seem to involve pulling in a priest at any point.

The Shinto influence on the Japanese side manifests in lots of stories involving 'let me tell you about the weird kami that was enshrined in my hometown' vs. that basically not being a thing on the American side.

'Rural villages are creepy' is basically a whole subgenre in Japan, really, and I can't really name any setting for the American stuff that's quite as prominent.

It might just be up to the fact that the American side uses more of the other categories to begin with, but I feel like there's a lot more 'maybe cryptids are actually aliens and ghosts are just psychic phenomena that manifest around aliens' kinda syncretism there.

742 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made some funny comics a little while ago about the potential effects of Fukuzawa's ability on Chuuya's, and how it perhaps could make it revert to a pre-Arahabaki state.

I realized later that some of you lack the context for where that came from, and that I might be creating confusion, so this is a (hopefully) comprehensive walkthrough of things we learned in Storm Bringer that lead to this conclusion.

tldr; The lab created "Arahabaki" by manipulating an ability into a destructive force. That ability existed before the lab, and the nature of that ability is heavily implied to be the power to enhance other abilities through touch.

Explanation and sources below (so you can judge yourself) ⬇

- spoiler warning for Storm Bringer, hopefully written in a way that you'd understand even if you haven't read it yet -

In Storm Bringer, Chuuya meets the scientist that was responsible for Project Arahabaki, Professor N.

Project Arahabaki, N explains, was the Japanese government's secret project to create an ability singularity they could have control over and freely use as a weapon.

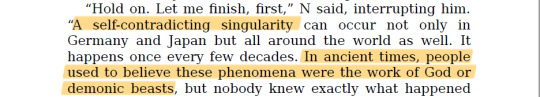

What are singularities? Singularities are what happens when abilities clash in specific ways and create a new, unforeseen reaction. The easiest way to create a singularity is to pit two contradictory abilities against each other to create a paradox; examples included the ability to always deceive and the ability to always perceive the truth, and to have two ability users who can see into the future (*coughs* Oda and Gide) try to one-up each other. The result is usually much more powerful than the original abilities on their own.

Some singularities are said to have been explained as god-like interventions, because of their often destructive nature. This is what inspired the name "Arahabaki", after the mythical being (here's a post of the subject and I'll it link at the end too) These events are described as very rare.

Like mentioned in that passage, there is another way to create a singularity: to have a single ability user use their ability in a way that contradicts itself. This is what the lab was trying to do.

For that explanation, Professor N gives an example. He first shows a video of a child, whose face is hidden from the camera, holding a coin (described as having a certain melancoly to it), with a moon and a fox engraved on it. The video is from one of the lab's tests. The child is made to recite some activation lines, which are directly taken from one of Nakahara Chuuya's poems, Upon the Tainted Sorrow (which does mentions a fox, as a fun fact).

The coin then starts glowing, the glow turns into a black mass, and from there the experimentation goes bad: the coin starts attracting things and absorbing them, the space gets distorted, the child's vitals flatline, panic spreads and someone calls for an emergency stop, we hear a scream. The video ends.

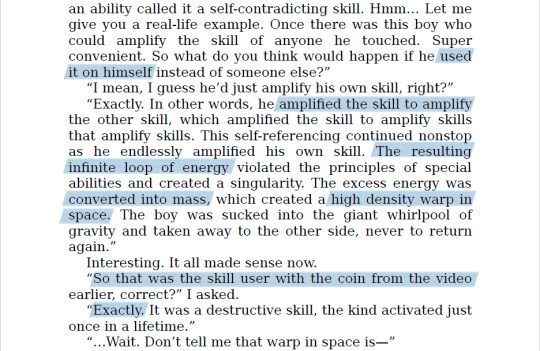

N explains that the child in the video had the ability to enhance the ability of others. That child then used that ability on themselves, effectively enhancing the enhancement which enhanced the enhancing, in an infinite loop. That loop created a lot of energy; the surplus of energy was so intense its mass deformed space (physics!) and it created a black hole.

Here's where it gets tricky: N claims that child died during that accident, that the child was absorbed by the black hole created by their ability. We never actually learn their identity.

But N is a lying liar who lies; he said about one and a half truths the entire book. The only reason he was telling them any of this was that he thought he'd get rid of all of them within the next few minutes. His objective was always to regain control over Chuuya, his pet project.

Plus, during the epilogue, we learn that Chuuya was assumed to have died during the war. That's what his parents think. That's what is officially recorded.

Furthermore.

Project Arahabaki was based off French research papers; someone else had done this kind of experimentation before, and their result was Verlaine.

-

Verlaine's gravity-manipulation is a singularity. Better yet: Verlaine also has a Corruption state, named Brutalization. Their abilities are the same, because the lab copied the techniques that were used to create Verlaine when they worked on Chuuya.

Here's a passage of Dazai nullifying Corruption, at the very end of SB:

"The self-contradicting skill, which was supporting the energy of a singularity". This passage confirms that the source of Chuuya's ability is, in fact, like the child's and Verlaine's, if any doubts remained. "[...] weakening the singularity's output. It wasn't long before it returned to its normal state, and the Gate closed." The Gate refers to releasing Arahabaki, it's basically a limiter, just like the passage above when talking about Brutalization. When Dazai nullifies Corruption, he gives that limiter the opportunity to come back and seal Chuuya's power away again, but does not stop the singularity, only allows it to go back to its stable state.

From all that, we can say that Chuuya's ability wasn't always gravity manipulation, but that it was another, unconfirmed ability that was exploited in such a way that it became a permanent, stable singularity that allowed him to have control over gravity.

-

Bullet point recap:

Chuuya's gravity manipulation comes from a singularity, like Verlaine, like that child;

You need a self-referencing/self-contradicting ability to create that singularity;

Such an event is rare;

There is a substantial amount of time spent describing a "random" child that was experimented on during the war;

That child created a black hole through their singularity;

That singularity was activated using a passage from Nakahara Chuuya's poems, while holding a coin that references it;

That child supposedly died;

Chuuya's parents think he died during the war;

N is a pathological liar with an agenda.

So no, there is no "confirmation" that Chuuya's ability was ability enhancement before the lab took him. But an author writes a story with an intent, so I am asking what Asagiri's intent was when writing all this, and if perhaps we weren't indirectly given the answer already.

-

What is Arahabaki (Fifteen and Storm Bringer lore, with too many citations)

My own perceived timeline of the true events behind Storm Bringer (was originally gonna be part of this part, also with too many citations)

#the dazai parallels are a nice little bonus because we KNOW chuuya as a character was designed to match dazai#he was most literally designed to go with him and contrast him#but that's meta analysis so i didn't include it in the actual post with the rest of the textual evidence#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bungo stray dogs#bsd analysis#bsd theory#bsd meta#bsd chuuya#bsd nakahara chuuya#bsd storm bringer#bsd stormbringer#stormbringer#storm bringer#i'll reblog this to my art blog tomorrow so the people most concerned have more of a chance of seeing it#apparently i talk sometimes

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Slug! If possible could you please translate the new updated timeline from the second guidebook? Thank you so much 🙏

I typically don't want to translate any sort of paid content, but I'll make an exception just this once so we can publicly shame Hypmic for its ludicrous timeline have this as a resource.

The guidebook's timeline is split into two halves corresponding to Chuuouku and the six Divisions featured in the storyline. For ease of reading, I've combined them into one and placed them in order (as much as possible).

The translation is as direct as possible. I do not translate word by word by the dictionary when there are more straightforward or natural-sounding equivalents available, and I do not incorporate features of the source grammar and punctuation that are nonsensical in English. Apart from that, this is super cut-and-dry. It's a timeline lol.

Finally, a note about the "H Age" (H歴) year system: While treated as its own calendar system similar to BCE and CE (or BC/AD), the H Age notation is otherwise similar to Japanese "eras." In real life, a new era corresponds to a new emperor taking the throne, so Otome's rise to power and the subsequent beginning of the H Age marks a paradigm shift. Eras can start in the middle of a calendar year, so Year 1 of the H Age isn't necessarily from January to December (in so much as Hypmic has months anyway). Let's arbitrarily say it started in June 2024. (Did it? No idea. I made this up for argument's sake.) That means Year 1 is June - December of 2024 while "one year prior" is January - May also of 2024. Therefore, "two years prior" is January - December of 2023. And so on and so forth.

Under a cut for length

19 years prior to the H Age

Rei joins a military R&D program.

Otome founds the Party of Words.

13 years prior to the H Age

World War III begins.

11 years prior to the H Age

World War III ends, but smaller violent conflicts continue.

Rei leaves the military and assembles an independent Hypnosis Mic development team.

4 years prior to the H Age

Rei creates a working Hypnosis Mic.

3 years prior to the H Age

Otome purchases the Hypnosis Mics from Rei.

The military creates a working Hypnosis Mic prototype.

Rei begins development of the Hypnosis Canceler.

2 years prior to the H Age

Rei creates a working True Hypnosis Mic.

1 year prior to the H Age

The Party of Words stages a coup d'tat.

Rei creates a working Hypnosis Canceler and gives the first Ramuda to Otome.

Year 1 of the H Age

The H Age begins, ending violent conflict with weapons.

The Party of Words overwhelms the preexisting government, thus subverting the state.

The Party of Words founds Chuuouku and distributes Hypnosis Mics to select candidates.

Ichirou and Kuukou form Naughty Busters.

Samatoki and Sasara form Mad Comic Dialogue.

Ramuda meets Jakurai and Yotsutsuji. The former two go on to form Kuujaku Posse.

Otome purchases the True Hypnosis Mic from Rei.

Ichirou and Kuukou begin working with Mad Comic Dialogue.

Year 2 of the H Age

Ramuda clones use the True Hypnosis Mic to brainwash Sasara and Kuukou. Kuukou tells Ichirou their friendship is over and leaves for Nagoya. Sasara does the same and returns to Osaka.

Ichirou, Samatoki, Ramuda, and Jakurai form The Dirty Dawg.

The Dirty Dawg gains supremacy over every Division in Japan. A Ramuda clone puts Yotsutsuji in a brainwashing-induced coma.

A Ramuda clone brainwashes Nemu. She goes on to join the Party of Words.

Ichirou and Samatoki battle one another in accordance with a Chuuouku plot. At the same time, Jakurai and Ramuda fight over the Yotsutsuji situation. This leads to The Dirty Dawg disbanding.

The Party of Words disables all preexisting Hypnosis Mics distributed [through their program in Year 1] and recalls the mics.

The Party of Words creates the Division Rap Battle program.

Year 3 of the H Age

Ichirou, Samatoki, Ramuda, and Jakurai receive mics from Chuuouku.

The Division Rap Battle program begins.

Ichirou forms the Buster Bros with Jirou and Saburou.

Samatoki forms Mad Trigger Crew with Juuto and Riou.

Jakurai forms Matenrou with Hifumi and Doppo.

Ramuda forms Fling Posse with Gentarou and Dice.

Preliminary matches begin within each Division. The Buster Bros, Mad Trigger Crew, Fling Posse, and Matenrou win their respective preliminaries, thus advancing to the finals.

Ichijiku uses a Hypnosis Canceler for the first time.

In the first DRB tournament, Mad Trigger Crew wins round 1 against the Buster Bros.

In the first DRB tournament, Matenrou wins round 2 against Fling Posse.

In the first DRB tournament, Matenrou wins the final match against Mad Trigger Crew and takes the championship.

Hitaki Tsumabira, Vice Director General of the Criminal Bureau, and the Tobari brothers attempt to lay a trap for the Buster Bros, Mad Trigger Crew, Fling Posse, and Matenrou. Their plot fails.

Ichijiku has Tsumabira purged from the Party of Words for using the Tobari brothers to traffic the Grasshopper drug.

The Party of Words announces the second DRB.

Kuukou and Sasara receive mics from Chuuouku.

Rei meets Sasara and Roshou. The three go on to form Dotsuitare Hompo.

Hitoya introduces Juushi to Kuukou, who takes Juushi under his wing as an apprentice. The three go on to form Bad Ass Temple.

Ichirou notices Nemu's name on a list of missing persons and meets up with Sasara and Roshou to find out more. Rei meets with Jirou and Saburou. He reveals that he is their father and that Ichirou has been lying to them.

Nemu becomes the Vice Director General of the Administrative Inspection Bureau.

Nemu, still brainwashed, shows up in front of Samatoki with other Chuuouku members. Ramuda confesses to Samatoki that he brainwashed her.

Gentarou and Dice learn that Ramuda is a clone.

Chuuouku approaches Jakurai for his crucial assistance in improving the True Hypnosis Mic in order to bring Yotsutsuji out of his coma. Jakurai and Hitoya reunite. Meanwhile, Hifumi and Doppo meet Kuukou and Juushi.

Chuuouku decides to have Ramuda killed. Honobono enlists the Word Wreckers to join her in hunting him down. Gentarou and Dice come to his rescue and spirit him away to safety, but now all three are wanted as outlaws.

Dice performs a trade with Otome, giving her the Chuuouku expose left behind by Gentarou's older brother. Ramuda is allowed to go free, and Fling Posse is granted permission to participate in the second DRB.

Jakurai agrees to cooperate with Chuuouku under certain conditions. Honobono pays a visit to Hifumi's club.

Juuto arrests Sekirei Hanmyou, the man responsible for the drug that led to Juuto's friend and parents' deaths.

Nemu arrests Tsumabira, now escaped from prison, and her coconspirator in crime Misago Haebaru. Honobono rises to position of Vice Director General of the Criminal Bureau in Tsumabira's place.

Ichirou battles Jirou while Saburou battles Rei. The brothers make up afterward.

After receiving advice from Rei, Sasara and Roshou battle one another and come clean about their feelings. With that bad blood washed away, the team comes together stronger than ever.

Juushi comes face to face with the boy who bullied him and took his grandmother's life. Through his own fortitude, Juushi prevails through the mental distress. After talking with Kuukou, Hitoya lets go of the past in seeking revenge for the death of his brother. The team comes together stronger than ever.

The second DRB preliminaries come to an end. The Buster Bros, Mad Trigger Crew, Fling Posse, Matenrou, Dotsuitare Hompo, and Bad Ass Temple advance to the finals.

In the second DRB tournament, the Buster Bros win round 1 against Dotsuitare Hompo.

In the second DRB tournament, Matenrou wins round 2 against Bad Ass Temple.

In the second DRB tournament, Fling Posse wins round 3 against Mad Trigger Crew.

In the second DRB tournament, Fling Posse wins the final match against the Buster Bros and Matenrou, thus claiming the championship.

Sasara and Kuukou learn that they were brainwashed. Ramuda opens up to Jakurai and tells him the truth. Ichirou and Samatoki learn the truth as well, thereby resolving the feuds between the team leaders.

The Party of Words announces the third DRB.

The Party of Words locates and seizes control of Rei's laboratory. In an exchange of hostages, the Party gains control of the True Hypnosis Mic and Ramuda clones.

Otome announces plans for world domination before Rei attempts a coup d'tat. All Hypnosis Mics are disabled, and Otome and Ichijiku are sent to maximum security prison by the very Ramuda clones Rei created.

Public order breaks down following the disabling of the mics.

Ichirou discovers Rei's connection to the Hypnosis Mics due to Gentarou's brother's expose. The main cast, led by Jirou and Saburou, hold a music festival to bring courage to everyone struggling with the political turmoil.

Honobono frees the inmates of Chuuouku's maximum security prison. After staging an attack on the music festival, she disappears from the eye of Chuuouku.

Rei and Ichirou have a fistfight over their respective moral positions. Rei acknowledges his defeat, reconsiders his moral stance, and reactivates all Hypnosis Mics.

Armed with a working mic once more, Nemu takes command and restores order within Chuuouku. Otome decides to step down from her position in government.

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

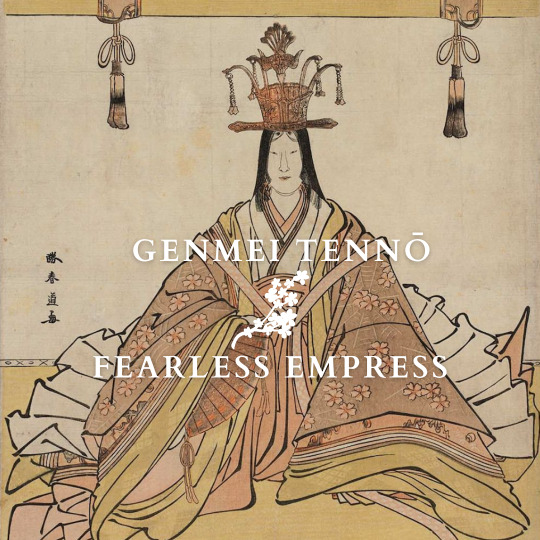

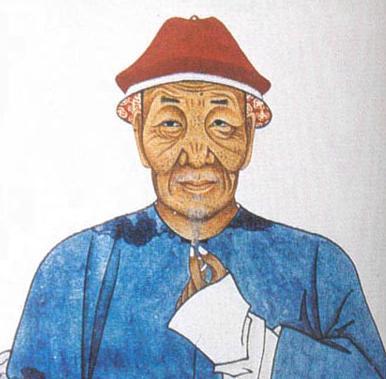

Genmei (661-721) was Japan's fourth empress regnant. She was Empress Jitō's half-sister and her match in terms of ambition and political skills. Her rule was characterized by a development of culture and innovations.

Ruling after her son

Like Jitō (645-703), Genmei was the daughter of Emperor Tenji but was born from a different mother. Jitō was both her half-sister and mother-in-law since Genmei had married the empress’ son, Prince Kusakabe (662-689). She had a son with him, Emperor Monmu (683-707).

Kusakabe died early and never reigned, which led to Jitō's enthronement. The empress was then succeeded by her grandson Monmu. The latter’s reign was short. In his last will, he called for his mother to succeed him in accordance with the “immutable law” of her father Tenji. Genmei accepted.

Steadfast and ambitious

Genmei was made from the same mold as her half-sister. She proved to be a fearless sovereign, undeterred by military crises.

She pursued Jitō's policies, strengthening the central administration and keeping the power in imperial hands. Among her decisions were the proscription of runaway peasants and the restriction of private ownership of mountain and field properties by the nobility and Buddhist temples.

Another of her achievements was transferring the capital at Heijō-kyō (Nara) in 710, turning it into an unprecedented cultural and political center. Her rule saw many innovations. Among them were the first attempt to replace the barter system with the Wadō copper coins, new techniques for making brocade twills and dyeing and the settlement of experimental dairy farmers.

A protector of culture

Genmei sponsored many cultural projects. The first was the Kojiki, written in 712 it told Japan’s history from mythological origins to the current rulers. In its preface, the editor Ō no Yasumaro praised the empress:

“Her Imperial Majesty…illumines the univers…Ruling in the Purple Pavillion, her virtue extends to the limit of the horses’ hoof-prints…It must be saif that her fame is greater than that of Emperor Yü and her virtue surpasses that of Emperor Tang (legendary emperors of China)”.

In 713, she ordered the local governments to collect local legends and oral traditions as well as information about the soil, weather, products and geological and zoological features. Those local gazetteers (Fudoki) were an invaluable source of Japan’s ancient tradition.

Several of Genmei’s poems are included in the Man'yōshū anthology, including a reply by one of the court ladies.

Listen to the sounds of the warriors' elbow-guards;

Our captain must be ranging the shields to drill the troops.

– Genmei Tennō

Reply:

Be not concerned, O my Sovereign;

Am I not here,

I, whom the ancestral gods endowed with life,

Next of kin to yourself

– Minabe-hime

From mother to daughter

Genmei abdicated in 715 and passed the throne to her daughter, empress Genshō (680-748) instead of her sickly grandson prince Obito. This was an unprecedented situation, making the Nara period the pinnacle of female monarchy in Japan.

Genmei would oversee state affairs until she died in 721. Before her death, she shaved her head and became a nun, becoming the first Japanese monarch to take Buddhist vows and establishing a long tradition.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading

Shillony Ben-Ami, Enigma of the Emperors Sacred Subservience in Japanese History

Tsurumi Patricia E., “Japan’s early female emperors”

Aoki Michiko Y., "Jitō Tennō, the female sovereign",in: Mulhern Chieko Irie (ed.), Heroic with grace legendary women of Japan

#history#women in history#women's history#japan#japanese history#empress genmei#japanese empresses#historical figures#historyedit#herstory#nara#japanese art#japanese prints

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

The horse is six feet under at this point I know but I still can't get over the gall of James Somerton correctly! arguing that Disney's lack of queer representation should be blamed solely on the company and not on the Chinese market, only to immediately fuck up any sort of logic he had in saying that by concluding that this is because China should be completely written off as a viable market because the government only lets people watch shows about communism and censors everything else 🤪 source: I shit you not, a right wing conspiracy theorist !! Since he doesn't actually know anything about the subject he's talking about, he's not actually making any arguments. He only mentions Chinese BL because the article he plagiarized did, and even then he has to punctuate it with a "audience of mostly STRAIGHT WOMEN! " of course, even though the article also acknowledges and has multiple interviews with queer Asian people who found comfort in the genre right below all the stuff he copied. There's no mention of queer Chinese artists or lesbian works or any sort of empowerment, probably because he didn't care to learn about any of them, and so rather than ending with what could have been a strong message about the persistence of queer identity even under political oppression, the video fizzles out into nothing with an aftertaste of "so Disney should just say fuck the Chinese and make whatever they want" (because yeah James sure that's the reason why Disney doesn't make gay stuff there's definitely no biases within the company itself or American culture) and "well at least we still have the Japanese and the Thai are making bl now!" Just the epitome of self-centered white saviorism. No real sympathy or respect for queer Asian struggles, just a reframing of a unique struggle with representation into "well I got mine so go get yours somewhere else" while he waits for them to spit out a work that he can regurgitate into a profit on his channel

#also he pronounced weibo as weebo#horrible. straight to the electric chair for that guy#james somerton

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shōgun Historical Shallow-Dive: the Final Part - The Samurai Were Assholes, When 'Accuracy' Isn't Accurate, Beautiful Art, and Where to From Here

Final part. There is an enormous cancer attached to the samurai mythos and James Clavell's orientalism that I need to address. Well, I want to, anyway. In acknowledging how great the 2024 adaptation of Shōgun is, it's important to engage with the fact that it's fiction, and that much of its marketed authenticity is fake. That doesn't take away from it being an excellent work of fiction, but it is a very important distinction to me.

If you want to engage with the cool 'honourable men with swords' trope without thinking any deeper, navigate away now. Beyond here, there are monsters - literal and figurative. If you're interested in how different forms of media are used to manufacture consent and shape national identity, please bear with me.

I think the makers of 2024's Shōgun have done a fantastic job. But there is one underlying problem they never fully wrestled with. It's one that Hiroyuki Sanada, the leading man and face of the production team, is enthusiastically supportive of. And with the recent announcement of Season 2, it's likely to return. You may disagree, but to me, ignoring this dishonours the millions of people who were killed or brutalised by either the samurai class, or people in the 20th century inspired by a constructed idea of them.

Why are we drawn to the samurai?

A pretty badly sourced, but wildly popular history podcast contends that 'The Japanese are just like everybody else, only more so.' I saw a post on here that tried to make the assertion that the show's John Blackthorne would have been exposed to as much violence as he saw in Japan, and wouldn't have found it abnormal.

This is incorrect. Obviously 16th and 17th century Europe were violent places, but they contained violence familiar to Europeans through their cultural lens. Why am I confidently asserting this? We have hundreds of letters, journals and reports from Spaniards, Portuguese, Dutch and English expressing absolute horror about what they encountered. Testing swords on peasants was becoming so common that it would eventually become the law of the land. Crucifixion was enacted as a punishment for Christians - first by the Taiko, then by the Tokugawa shogunate - for irony's sake.

Before the end of the feudal period, battles would end with the taking of heads for washing and display. Depending on who was viewing them, this was either to honour them, or to gloat: 'I'm alive, you're dead.' These things were ritualised to the point of being codified when real-life Toranaga took control. Seppuku started as a cultural meme and ended up being the enforced punishment for any minor mistake for the 260 years the ruling samurai class acted as the nation's bureaucracy. It got more and more ritualised and flowery the more it got divorced from its origin: men being ordered by other men to kill themselves during a period of chaotic warfare. I've read accounts of samurai 'warriors' during the Edo period committing seppuku for being late for work. Not life-and-death warrior work - after Sekigahara, they were just book-keepers. They had desk jobs.

Since Europe's contact with Japan, the samurai myth has fascinated and appalled in equal measure. As time has gone on, the fascination has gone up and the horror has been dialled down. This is not an accident. This isn't just a change in the rest of the world's perception of the samurai. This is the result of approximately 120 years of Japanese government policies. Successive governments - nationalist, military authoritarian, and post-war democratic - began to lionize the samurai as the perfect warrior ideal, and sanitize the history of their origin and their heydey (the period Shōgun covers). It erases the fact that almost all of the fighting of the glorious samurai Sengoku Jidai was done by peasant ashigaru (levies), who had no choice.

It is important to never forget why this was done initially: to form an imagined-historical ideal of a fighting culture. An imagined fighting culture that Japanese invasion forces could emulate to take colonies and subdue foreign populations in WWI, and, much more brutally, in WWII. James Clavell came into contact with it as a Japanese Prisoner of War.

He just didn't have access to the long view, or he didn't care.

The Original Novel - How One Ayn Rand Fan Introduced Japan to America

There's a reason why 1975's Shogun novel contains so many historical anachronisms. James Clavell bought into a bunch of state-sanctioned lies, unachored in history, about the warring states period, the concept of bushido (manufactured after the samurai had stopped fighting), and the samurai class's role in Japanese history.

For the novel, I could go into great depth, but there are three things that stand out.

Never let the truth get in the way of a good story. He's a novelist, and he did what he liked. But Clavell's novel was groundbreaking in the 70's because it was sold as a lightly-fictionalised history of Japan. The unfortunate fact is the official version that was being taught at the time (and now) is horseshit, and used for far-right wing authoritarian/nationalist political projects. The Three Unifiers and the 'honour of the samurai' magnates at the time is a neat package to tell kids and adults, but it was manufactured by an early-20th century Japanese Imperial Government trying to harness nationalism for building up a war-ready population. Any slightly critical reading of the primary sources shows the samurai to be just like any ruling class - brutal, venal, self-interested, and horrifically cruel. Even to their contemporary warrior elites in Korea and China.

Fake history as propraganda. Clavell swallowed and regurgitated the 'death before dishonour', 'loyalty to the cause above all else', 'it's all for the Realm' messages that were deployed to justify Imperial Japanese Army Class-A war crimes during the war in the Pacific and the Creation of the Greater East Asian Co-Properity Sphere. This retroactive samurai ethos was used in the late Meiji restoration and early 20th century nationalist-military governments to radicalise young Japanese men into being willing to die for nothing, and kill without restraint. The best book on this is An Introduction to Japanese Society by Sugimoto Yoshio, but there is a vast corpus of scholarship to back it up.

Clavell's orientalism strays into outright racism. Despite the novel Shōgun undercutting John Blackthorne as a white savior in its final pages - showing him as just a pawn in the game - Clavell's politics come into play in every Asia Saga novel. A white man dominates an Asian culture through the power of capitalism. This is orthagonal to points 1 and 2, but Clavell was a devotee of Ayn Rand. There's a reason his protagonists all appear cut from the same cloth. They thrust their way into an unfamiliar society, they use their knowledge of trade and mercantilism to heroically save the day, they are remarked upon by the Asian characters as braver and stronger, and they are irresistible to the - mostly simpering, extremely submissive - caricatures of Asian women in his novels. Call it a product of its times or a product of Clavell's beliefs, I still find it repulsive. Clavell invents (nearly from whole cloth, actually) the idea that samurai find money repulsive and distasteful, and his Blackthorne shows them the power of commerce and markets. Plus there are numerous other stereotypes (Blackthorne's massive dick! Japanese men have tiny penises! Everyone gets naked and bathes together because they're so sexually free! White guys are automatically cool over there!) that have fuelled the fantasies of generations of non-Japanese men, usually white: Clavell's primary audience of 'dad history' buffs.

2024's Shōgun, as a television adaptation, did a far better job in almost every respect

But the show did much better, right? Yes. Unquestionably. It was an incredible achievement in bringing forward a tired, stereotypical story to add new themes of cultural encounter, questioning one's place in the broader world, and killing your ego. In many ways, the show was the antithesis to Clavell's thesis.

It drastically reigned in the anachronistic, ahistorical referencees to 'bushido' and 'samurai honor', and showed the ruling class of Japan in 1600 much more accurately. John Blackthorne (William Adams) was shown to be an extraordinary person, but he wasn't central to the outcome of the Eastern Army-Western Army civil war. There aren't scenes of him being the best lover every woman he encounters in Japan has ever had (if you haven't read the book, this is not an exaggeration). He doesn't teach Japanese warriors how to use matchlock rifles, which they had been doing for two hundred years. He doesn't change the outcome of enormous events with his thrusting, self-confident individualism. In 2024's Shōgun, Blackthorne is much like his historical counterpart. He was there for fascinating events, but not central. He wasn't teaching Japanese people basic concepts like how to make money or how to make war.

On fake history - the manufactured samurai mythos - it improved on the novel, but didn't overcome the central problems. In many ways, I can't blame the showrunners. Many of the central lies (and they are deliberate lies) constructed around the concept of samurai are hallmarks of the genre. But it's still important to me to notice when it's happening - even while enjoying some of the tropes - without passively accepting it.

'Authenticity' to a precisely manufactured story, not to history

There's a core problem surrounding the promotion and manufactured discussion surrounding 2024's Shōgun. I think it's a disconnect between the creative and marketing teams, but it came up again and again in advertising and promotion for the show: 'It's authentic. It's as real as possible.'

I've only seen this brought up in one article, Shōgun Has a Japanese-Superiority Complex, by Ryu Spaeth:

'The show also valorizes a supreme military power that is tempered by the pursuit of beauty and the highest of cultures, as if that might be a formula for peace. Shōgun displays these two extremes of the Japanese self, the savagery and the refinement, but seems wholly unaware that there may be a connection between them, that the exquisite sensibility Japan is famous for may flow from, and be a mask for, its many uses of atrocious domination.'

Here we come to authenticity.

'The publicity surrounding the series has focused on its fidelity to authenticity: multiple rounds of translation to give the dialogue a “classical” feel; fastidious attention to how katana swords should be slung, how women of the nobility should fold their knees when they sit, how kimonos should be colored and styled; and, crucially, a decentralization of the narrative so that it’s not dominated by the character John Blackthorne.'

It's undeniable that the 2024 production spent enormous amounts of energy on authenticity. But authenticity to what? To traditional depictions of samurai in Japanese media, not to history itself. The experts hired for gestures, movement, costumes, buildings, and every other aspect of the show were experts with decades in experience making Japanese historical dramas 'look right', not experts in Japanese history. But this appeal to 'Japanese authenticity' was made in almost every piece of promotional material.

The show had only one historical advisor on staff, and he was Dutch. The numerous Japanese consultants, experts and specialists brought on board (talked about at length in the show's marketing and behind the scenes) were there to assist with making an accurate Japanese jidaigeki. It's the difference between hiring an experienced BBC period drama consultant, and a historian specialising in the Regency. One knows how to make things look 'right' to a British audience. The other knows what actually happened.

That's fine, but a critical viewing of the show needs to engage with this. It's a stylistically accurate Japanese period drama. It is not an accurate telling of Japanese history around the unification of Japan. If it was, the horses would be the size of ponies, there would be far more malnourished and brutalised peasants, the word samurai would have far less importance as it wasn't yet a rigidly enforced caste, seppuku wouldn't yet be ritualised and performed with as much frequency, and Toranaga - Tokugawa - would be a famously corpulently obese man, pounding the saddle of his horse in frustration at minor setbacks, as he was in history.

The noble picture of restraint, patience, refinement and honour presented by Hiroyuki Sanada as Toranaga/Tokugawa is historical sanitation at its most extreme. Despite being Sanada's personal hero, Tokugawa Ieyasu was a brutal warlord (even for the standards of the time), and he committed acts of horrific cruelty. He ordered many more after gaining ultimate power. Think a miniseries about the Founding Fathers of the United States that doesn't touch upon slavery - I'm sure there have been plenty.

The final myth that 2024's Shōgun leaves us with is that it took a man like Toranaga - Tokugawa Ieyasu - to bring peace to a land ripped assunder by chaos. This plays into 19th century notions of Great Man History, and is a neat story, but the consensus amongst historians is if it wasn't Tokugawa, it would have been some other cunt. In many cases, it very nearly was. His success was historical contingency, not 5D chess.

So how did this image get manufactured, to the point where the Japanese populace - by and large - believes it to be true? Very long story short: after a period of rapid modernisation, Japan embraced nationalism in the late 19th century. It was all the rage. Nationalism depends on a glorified past. The samurai (recently the pariahs of Japanese history) were repurposed as Japan's unique warrior heroes, and woven into state education. This was especially heated in the 1920s and 30s in the lead up to the invasion of Manchuria and Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. Nationalism + militarism = the modern Japanese samurai myth, to prepare men to obey orders unquestioningly from a military dictatorship.

This persists in the postwar period. Every year since 1963, Japan's state broadcaster NHK commissions a historical drama - a Taiga Drama, where many of this show's actors got their starts - that manufactures and re-enforces the idea of samurai as noble, artful, honourable people. Read a book - read a Wikipedia article! - and you'll see that most of it stems from Tokugawa-shogunate era self-propaganda. It's much like the European re-interpretation of chivalry. In Europe's case, chivalry in actual history was a set of guidelines that allowed for the sanctioned mass-rape and murder of civilians, with a side of rules regarding the ransoming of nobles in scorched-earth military campaigns. In Japan's case, historical figures that regularly backstabbed each other, tortured rival warriors and their lessers, and inflicted horrific casualties on the peasants that they owned (we have a term for that) are cast as noble, honourable, dedicated servants of the Empire.

Why does this matter to me? Samurai movies and TV shows are just media, after all. The issue, for me, is that the actors, the producers - including Hiroyuki Sanada - passionately extoll 'accuracy' as if they genuinely believe they're telling history. They talk emotionally about bushido and its special place in Japanese society.

But the entire concept of bushido is a retroactive, post-conflict, samurai construction. Bushio is bullshit. Despite being spoken of as the central tenet of 2024's Shōgun by actors like Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, and Tokuma Nishioka, it simply didn't exist at the time. It was made up after the advent of modern nationalism.

It was used to justify horrendous acts during the late Edo period, the Meiji restoration, and the years leading up to the conclusion of Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. It's still used now by Japan's primarily right-wing government to deny war crimes and justify the horrors unleashed on Asia and the Pacific during World War II as some kind of noble warrior crusade. If you ever want your stomach turned, visit the museum attached to Yasukuni Shrine. It's a theme park dedicated to war crimes denial, linked intimately to Japan's imagined warrior past. Whether or not the production staff, cast, and marketing team of 2024's Shōgun knew they were engaging with a long line of ahistorical bullshit is unknown, but it is important.

It's also important to acknowledge that, having listened to many interviews with Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, they were acutely aware that they weren't Japanese, to claim to be telling an authentically Japanese story would be wrong, and that all they could do was do their best to make an engaging work that plays on ideas of cultural encounter and letting go. I think the 'authenticity!' thing is mostly marketing, and judicious editing of what the creators and writers actually said in interviews.

So... you hate the show, then? What the hell is this all about?

No, I love the show. It's beautiful. But it's a beautiful artwork.

Just as the noh theatre in the show was a twisting of events within the show, so are all works of fiction that take inspiration from history. Some do it better than others. And on balance, in the show, Shōgun did it better than most. But so much of the marketing and the discussion of this adaptation has been on its accuracy. This has been by design - it was the strategy Disney adopted to market the show and give it a unique viewing proposition.

'This time, Shōgun is authentic!*

*an authentic Japanese period drama, but we won't mention that part.

And audiences have conflated that with what actually happened, as opposed to accuracy to a particular form of Japanese propaganda that has been honed over a century. This difference is crucial.

It doesn't detract from my enjoyment of it. Where I view James Clavell's novel as a horrid remnant of an orientalist, racist past, I believe the showrunners of 2024's Shōgun have updated that story to put Japanese characters front and centre, to decentralise the white protagonist to a more accurate place of observation and interest, and do their best to make a compelling subversion of the 'stranger in a strange land' tale.

But I don't want anyone who reads my words or has followed this series to think that the samurai were better than the armed thugs of any society. They weren't more noble, they weren't more honourable, they weren't more restrained. They just had 260 years in which they worked desk-jobs while wearing two swords to write stories about how glorious the good old days were, and how great people were.

Well... that's a bleak note to end on. Where to from here?

There are beautiful works of fiction that engage much closer with the actual truth of the samurai class that I'd recommend. One even stars Hiroyuki Sanada, and is (I think) his finest role.

I'd really encourage anyone who enjoyed Shōgun to check out The Twilight Samurai. That was the reality for the vast majority of post-Sekigahara samurai

For something closer to the period that Shogun is set, the best film is Seppuku (Hara-Kiri in English releases). It is a post-war Japanese film that engages both with the reality of samurai rule, and, through its central themes, how that created mythos was used to radicalise millions of Japanese into senseless death during the war. It is the best possible response to a romanticisation of a brutal, hateful period of history, dominated by cruel men who put power first, every single time.

I want to end this series, if I can, with hope. I hope that reading the novel or watching the 1980 show or the 2024 show has ignited in people an interest in Japanese culture, or society, or history. But don't let that be an end. Go further. There are so many things that aren't whitewashed warlords nobly killing - the social history of Japan is amazing, as is the women's history. A great book for getting an introduction to this is The Japanese: A History in 20 Lives.

And outside of that, there are so many beautiful Japanese movies and shows that don't deal with glorified violence and death. In fact, it makes up the vast majority of Japanese media! Who would have thought! Your Name was the first major work of art to bridge some of the cultural animosity between China and Japan stemming from WW2, and is a goofy time travel love story. Perfect Days is a beautiful movie about the simple joy of living, and it's about the most Tokyo story you can get.

Please go out, read more, watch more. If you can, try and find your way to Japan. It's one of the most beautiful places on earth. The people are kind, the food is delicious, and the culture is very welcoming to foreigners.

2024's Shōgun was great, but please don't let that be the end. Let it be the beginning, and I hope it serves as a gateway for you.

And I hope our little fandom on here remembers this show as a special time, where we came together to talk about something we loved. I'll miss you all.

#shōgun#shogun#shogun fx#toda mariko#john blackthorne#anjin#adaptationsdaily#perioddramasource#hiroyuki sanada#yoshii toranaga#akechi mariko#history#history lesson#japan#world war ii#japanese culture#tokugawa ieyasu#hosokowa gracia#william adams#sengoku jidai#writer stuff#book adaptation#women in history#social history#period drama

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

on my chemical romance's history of racism:

(edit: i wont rewrite anything since that will create discrepancies in reblogs. however, i will include these important additions: post 1 and post 2)

cultural appropriation is a neutral term that turns negative when people co-opt a culture without consideration to its people and history, or their prejudices and privileges. the rising sun japanese flag is an imperialist symbol used during japan's occupation of other countries from 1870 to 1945 (the guardian 2019). unlike other symbols of terror, the rising sun is normalized because of the japanese government's refusal to acknowledge its history. the symbol's meaning was popularized a few years ago when people from south korea protested its legality in the 2020 tokyo olympics (bbc 2020). aware or unaware of its history, americans have long appropriated the rising sun. in part because of their fascination with japanese art, in part because of orientalism -- a fixation on asian cultures that centers "exoticism".

my chemical romance has been associated with the rising sun symbol a couple of times. frank iero used to have a tattoo of it. gerard way designed frank's killjoys outfit to include it (seen in concept art and music videos). it is often used in mcr fanart.

tokenism is when something contains limited diversity to divert criticisms for the lack of it. my chemical romance has had a very white cast of characters in their music videos and stories. in the "i dont love you" music video, a main character is in black body paint. in the casting call, they specifically asked for a white man (there is 100% an online source -- please let me know if you have it). even casting a black person for this role would place him in a video that appropriated his skin color to mark his "difference" from the light-skin female character.

the female character points to the band's main problem with tokenism. if they arent casting a white woman, theyre casting a light-skin asian woman. the woman in the "i dont love you" mv is fetishized for physical traits stereotypically attributed to east asian women: big eyes, daintiness. east asian women feature most prominently aside from the band and main characters in the "welcome to the black parade" music video and photo shoot. the photoshoot is the only place where an ashy-faced black man and ambiguously tribal? brown man are seen (brought in by photographer chris anthony per the "making of the black parade" book). the director antagonist of the danger days music videos (shown in "sing") is a japanese woman. she is the only main character of color in the music videos and the killjoys: california comics. the focus of this post is on my chemical romance, but the comics are important to showcase that the reality is never "color-blind casting" or "limited roles". it's mostly white creatives (band members and directors and artists) who ignore non-white people when they cant use them, reflected as much by gerard way years later (nyt 2019).

"japan takes over the world" is a media trope that is built on the late 20th century fear of the return of imperial japan. this trope frames japanese people as unique aggressors, feeding into "yellow peril" fears of asian people "taking over" the white race. this trope is suggested all over the danger days universe, where the corporation BL/ind overthrows the US government. the appropriation of the japanese modern flag and lettering on the killjoys outfits, the primary BL/ind villain being a japanese person who only speaks japanese in videos, the official BL/ind website having a ".jp" domain and english-japanese translations. japanese people and culture only exist in this universe to decorate and threaten.

the point of this post is not to punish my chemical romance. in the decade+ since, they have made meaningful changes -- the sing it for japan project to aid japan during the 2011 earthquake-tsunami, developing diversity in gerard's comics / tv show, a mexican-american main character in the 2020 summoning video. people of color treated as real goddamn people.

however. all these faults exist in frozen time. there is no discussion attached to the work. so anyone, fan or casual, may come across it and not notice or care for these important issues. i know all this shit and i still fail to see instances of what i highlighted. it's difficult locating not only your own prejudices but those of others. those you look up to.

"my chemical romance" is the product of many people from 2001 to 2013. many of these people were male, white, american, and/or, most radically, liberal. clearly laying out what they did wrong is important. being careful with history and culture and personhood is important. prioritizing growth is important. constantly. forever.

#mcr#this has been weighing on me for a long time. i just didnt know how to say it. why i should say it if someone else already has#and well. thru writing this i figured everyone should say it to really understand it#qessay

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Arka"

Going to post this here since this could also be interesting to the Finnish learners on here (for more Ainu content, I post on @kkulbeolyeonghwa a lot!)

For people who have no idea what Ainu is, it's the one Japanese minority language the Japanese government recognizes. It's spoken in northern Japan, Hokkaido island.

The Finnish word arka and the Ainu word arka have almost exactly the same meaning.

In Finnish, it can mean shy or sensitive, but it also has a meaning of "sore" or "painful to the point you don't dare to touch". It comes from the Proto-Germanic *argaz. (The same root developed to be "eerie" in English)

Jalkani on vähän arka. - My foot is a bit sore.

Haavani on vieläkin arka. - My wound is still sore.

In Ainu, the word arka means "painful" in general, ranging from "sore" to "tired" (of limbs) to actual high pain levels. Nobody knows where this word came from though. I tried looking at other local languages and finding a potential source but couldn't find anything.

Ku=cikirihi ponno arka. - My foot is a bit sore.

Ku=pirihi naa arka. -My wound is still sore.

These words cannot be related to each other, but it's fun to see a similar thing in both languages!

Language geekery over thanks for listening.

#finnish#langblr#langblog#language#finland#suomen kieli#suomi#finnish language#vocabulary#ainu#ainu itak

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source: http://nihongami.blogspot.com/2023/11/blog-post_22.html

Nihongami: Historical Overview - Part 01B

Historical Time Period: Nara Period (710-794 CE)

Hairstyle Name: Zujouni Motodori (頭上二髻) lit. “Two Sky High Topknots"

During the Nara period of Japanese history (710-794 CE), the ancient Japanese government was still experiencing strong Chinese and Korean influences on Japanese clothing and hairstyles.

This is a hairstyle found in haniwa, hollow unglazed terracotta figure from the Kofun period (330-538 CE). The hair tied on top of the head is divided into two and tied into a topknot. In the Manyoshu (8th-century anthology of Japanese poetry), this hairstyle is called "角髪, Kakukami'' (lit. "antler hair") and in later generations, it was called agemaki.

#kimono#nihongami#zujounimotodori#zujouni#motodori#nihongamitimeline01#nihongamitimeline#kofun#kofunperiod#nara#naraperiod

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

soy sauce question: why do you think the limited information on Blanche Appleton indicates some kimd of conspiracy? It doesn't really seem surprising that there's not more information available about her, since she was one of thousands of mid-level bureaucrats trying to figure out how to distribute scarce post-war resources appropriately. Have you found any other signs of a cover-up or yakuza involvement?

Since starting this research the information has steadily been showing a clearer picture; the finer details of it are still pretty vague and blurry, but I've at least nailed down the foundations.

There was a woman named Blanche Appleton, married to Melville Dickinson, who worked for the GHQ-SCAP and the UNRRA during World War II and lived in Japan during the American postwar occupation. Her descendant that I'm in contact with have told me, quote,

"My grandmother spoke fluent Japanese (among many other languages) and did have connections in the business world there although no one in the family knows of their exact nature."

and

This is the first that I have ever heard of any connection to soy sauce or any particular business venture. There was always a family rumor that she was well connected, but that was attributed to my grandfather's position, not hers.

She was given control over the soy sauce industry in Japan via America--sources here, here, and in the Tokyo Institute for International Policy Studies' 2005 meeting, "Upcoming Changes in Japanese Society and

the Future Shape of the Nation". All of these sources not just state that Appleton was involved on the Economics and Scientific team at General Headquarters, they all corroborate and confirm that she, as an individual government worker, was given total control over soy breweries and had power to refuse or grant the materials needed to create soy sauce.

Soy sauce brewed pre-industrialization is considered far superior to the modern techniques which were invented to hasten turnarounds and "waste" less soy beans. From all sources I can find so far, Appleton seems to have had a fundamental disconnect and disbelief about what soy sauce is supposed to be or what it represents, even going so far as to saying that she, quote,

"I want to change Japan's taste preference.”

For the final question regarding proof of yakuza/cover-up, I'm not at liberty to say right now, and I hope you can understand why I might be extremely hesitant and outright unwilling to confirm or deny any of that sort of thing before full publication and complete confidence in something that won't get me sued out of my mind. For legal purposes right now, as I work on this investigation, you can quote me as saying that there is not yet any substantial, non-circumstantial evidence which directly links all three parties of Blanche Appleton, the US government, and the Kikkoman Corporation together in any form of conspiratorial agreement or relationship. I hope that can satisfy you and answer at least some of your questions, just as I hope that you can be satisfied with the reason why I don't feel safe giving anything more than that to the public right now.

#the mysterious appearance of miss appleton#there's also actually a surprising amount of info just not in english channels which tracks i think#rn i'm getting a lot of translations done to get a good idea of what's being said in native language from the nation as a whole

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

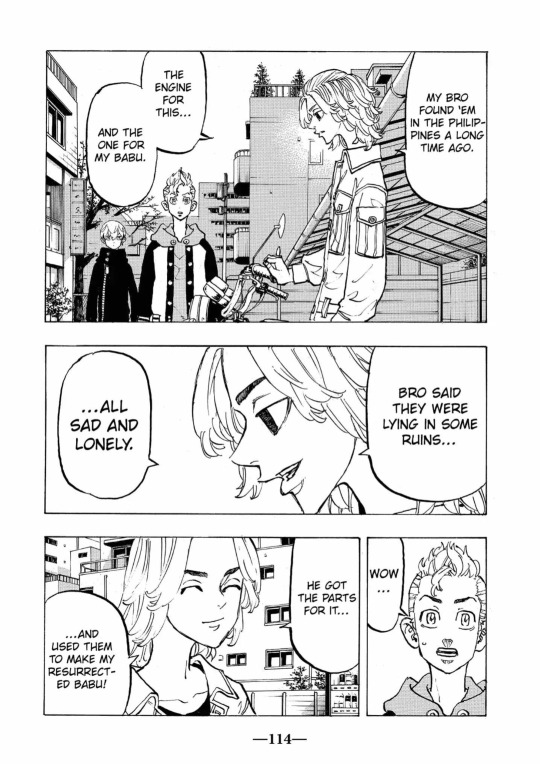

where did shinichiro go during his stay in the philippines?

an. an interesting (and really quick) insight into the story between japan and the philippines included in tokyo revengers! inspired by this @tokyo-daaaamn-ji-gang's post. i saw as i did my research that some people already knew where it was, but without further explanation as to why or any add-ups, so i'll bring what i know to tumblr!

cw: tr spoilers, big analysis post, mentions of war & rape

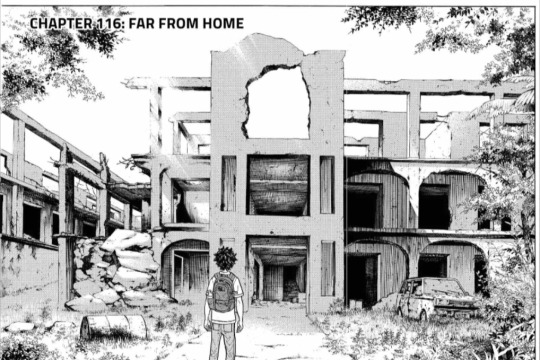

so! manila. mostly known because that's where mikey asks takemichi to meet him in the future and unfortunately dies in one of the bad timelines (chapter 116, black dragon's arc).

but why manila?

that's a fairly easy question. the answer is given three chapters before: this is where shinichiro found the parts for the twin babu bikes. mikey clearly says he wants to go there in the future, probably because that's one of the last places he can associate with his big brother and hasn't been to yet.

the follow-up question is: what was shinichiro doing there?

the manga doesn't give us a clear answer. since izana is half-philipino, we can assume he went there to get more information about his brother's roots: who was his real mother? did he have a family who knew about him there?

this is where things get interesting. because while that was a nice gesture, shinichiro had surely no idea on where to start. his father was dead, karen kurokawa was nowhere to be found and grandpa sano is a useless old hag who never ever served the plot (confirmed by where shinichiro went because it didn't make much sense), leaving him without any info he could use to start looking for izana's potential relatives.

so he turned to a place he knew in the philippines: the corregidor island in manila's bay.

why would shin know about the corregidor island? surprising answer: world war two.

i did not know about it until i did some research for this post (!! you can call me uncultivated), but japan occupied the philippines (among other countires) during the world war two. i did a good amount of research, but i struggled understanding it all (esp because i find wikipedia's navigation confusing on the topic), so i just copy-pasted some parts that hopefully, if my selection is good, explain globally what happened. if you are interested on the topic, i do recommend you to do your own research.

the philippines campaign, also known as the battle of the philippines or the fall of the philippines, was the invasion of the american territory of the philippines by the empire of japan and the defense of the islands by united states and the philippine armies during world war ll.

the japanese planned to occupy the philippines as part of their plan for a "greater east asia war" in which their southern expeditionary army group seized sources of raw materials [in malaya and the netherlands east indies]. captain ishikawa shingo, a hard-liner in the imperial japanese navy, had toured the philippines and other parts of southeast asia in 1936, noting that these countries had raw materials japan needed for its armed forces. this helped further increase their aspiration for colonizing the philippines.

the battle of the philippines resulted from the invasion of the philippine commonwealth by the empire of japan in 1941-42 and the defense of the archipelago by filipino and american troops. this battle resulted in a japanese victory.

(see: battle of bataan). after the flight of the philippine government and the end of the battle bataan on 9 april 1942, the japanese controlled the entire northern part of the philippine archipelago, with the exception of the island of corregidor. the capture of the island was also the condition for the japanese to ensure control of manila bay.

(see: battle of corregidor). corregidor (which included fort mills) was a u.s. army coast artillery corps position defending the entrance to manila bay, part of the harbor defenses of manila and subic bays. it was defended by 11,000 soldiers. some could reach corregidor via the baatan peninsula, where they had escaped the japanese attack. the 59th regiment was able to repel japanese air attacks, shooting down numerous planes. the older stationary batteries with fixed mortars and immense cannon, for defense from attack by sea, were easily put out of commission by japanese bombers. the american soldiers and filipino scouts defended the small fortress until they had little left to wage a defense. on december 29, 1941, the japanese carried out a strategic bombing raid on corregidor, destroying the hospital. until the end of april, the filipino and american defenders of the island resisted attacks by japanese aircraft, which inflicted 614 bombings on them, for a total of 365 tons of explosives. from april 28, the bombings increased in intensity. beginning on may 1, japanese artillery also began firing from bataan. early in 1942, the japanese air command installed oxygen in its bombers to fly higher than the range of the corregidor anti-aircraft batteries, and after that time, heavier bombardment began.

the capture of corregidor marked the final victory of the japanese in the philippines, but contributed, like the battle of bataan, to cost them precious time, handicapping their strategy in the pacific ocean region.

4,000 of the 11,000 filipino and american prisoners were then paraded by the japanese in the streets of manila. several thousand were sent to labor camps (see: baatan death march) and numerous women were forced into sexual slavery by the imperial japanese armed forces (see: comfort women and asia women's fund)

corregidor was recaptured in another battle in 1945, during the liberation of the philippines. a pacific war memorial was later built on corregidor, commemorating the resistance of american and filipino soldiers.

first of all, i really reccomend you the asia women's fund digital museum for information related to comfort women—if it something you can stomach. second of all, i think it's a great addition that wakui included a reference to this in the manga, even if it is in such a discreet way. the corregidor hospital (specific place where takemitchy finds mikey) is very much drawn the same way as it looks in real life, but it is specified nowhere in the series where this is or why this place is chosen, and yet it holds a very important role in japanese history.

(pics from dailytakemitchi on twt, og post + google maps location)

though it is true that japan is known for not recognizing it's war crimes (see: nanjing massacre); certainly here an apology to the philippines was made, but only seventy-two years after the incident, so this issue was most likely very taboo by the time shin went there (which must have been between the time period where he met izana in the orphanage and their fight. judging by shin's haircut (we are working with very little information here ok but he didn't had his punch perm when we see him fiding the bikes so i believe it is around the time he askd mikey if he would like to have an older brother), i'd say 2000-2003ish, when izana was in juive. thanking the gods for this izana's timeline post btw, i actually need one with everyone's tls please-). philipino people were, from what i have understood, a pretty consequent part of the population in the 2000s for the reasons i mentionned just before. wakui must have met a few in his bossozoku days, and from them comes izana. i really like the fact that every one of the inclusions in the manga come from his real-life experience, it adds a lot to his whole universe!!

so yeah, if shin came there, it is probably because he did some research by himself on the philippines &this ended up being one of the first places that came up and catched his attention. like i said, it is likely that he went to the philippines looking for izana's relatives, but it strikes me as weird that he went there since the corregidor island has nothing but ruins to offer. maybe he just did some tourism on his way.

this whole trip didn't end up giving him any more information on izana's family. we don't actually know if izana's mother was in the philippines; karen does say that he is the son of her ex-husband and a filipino woman, but she herself is american and lives in japan. important to note that the ex-husband in question is not makoto sano! i personally had a hard time understanding that(oᗜo;)

this place is said to be haunted by the ghosts of filipino, american and japanese soldiers who died there, especially in the hospital. as for today, it is possible to visit the location, and there are vlog-type articles of people who went there, some quick youtube summaries and a few videos like "spending the night in this haunted island😱😱"

aaand this is pretty much all i had to say about this!! i haven't adressed the twin bikes because it'll be for another post. this post might not be much, esp taking in consideration how much time i took to post it(ᵕ—ᴗ—) but i had fun writting it! hopefully this post will find it's public. if you are still here, thank you so much for reading the whole thing!! i'll be posting some more tr posts like this one, so stay tuned. ( ˶ˆᗜˆ˵ )

#— a post ?! 💤#i mean 'stay tuned' like alastor when he said that and we got the first ep three years later#if anyone wants to be tagged in the future send me a message!#tokyo revengers meta#tokyo revengers headcanons#tokyo revengers#tokyo rev#tokrev#tokyo revengers spoilers#sano shinichiro#shinichiro sano#izana kurokawa#kurokawa izana#mikey sano#manjiro sano#hanagaki takemichi#takemichi hanagaki#takemitchy#tr shinichiro#shinichiro headcannons#izana headcanons#mikey headcanons#tokyo revengers analysis#tokyorev meta

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Roaming into immortality”: Ten Desires and the history of Taoist immortals

As promised last month, following the freshly established tradition I have another Touhou research post to offer. This time, we’ll be looking into the literary traditions focused on Taoist immortals (or, following the Touhou convention, “hermits”, though this is a less suitable translation) and how they influenced Ten Desires. Due to space constraints and thematic coherence, note that only Seiga, Miko and Yoshika will be covered.

Before you'll begin, I need to stress that one of the sections requires a content warning. While all images are safe for viewing, there's a description of a potentially unpleasant episode involving unwanted advances, and various events leading to that; I highlighted that before the relevant paragraphs too just in case.

“Hermit”, “immortal”, “transcendent”

A post about Ten Desires must start with an introduction of the term sen, the Japanese reading of 仙, Chinese xian. Touhou specifically uses its less common derivative 仙人, sennin, though that's just a synonym. Touhou-related sources basically invariably translate this term as “hermit”. While this option can be found elsewhere too, it is not exactly optimal.

“Immortal” is actually the standard translation for both sen/xian and sennin, as far as I am aware. I did a quick survey of recent publications on Brill’s and De Gruyter’s sites and the results were fairly unambiguous, especially for books and articles published after 2000, with “hermit”, “wizard” and other alternatives being quite uncommon. The trend is not new, with sennin already translated as “immortal” in the 1960s.

When it comes to xian/sen, in a few cases arguments were made that “transcendent” or “ascendent” would be a more suitable option as it better illustrates the position of these beings, though this is a relatively recent trend, for now limited to Sinology. The idea behind it is that immortality is just one of multiple characteristics attributed to the xian, and it is ultimately the transcendence to a higher level of existence that’s the key element. I personally think the argument is sound, but not all translators have embraced it, and for now the choice is really a matter of preference. Since “immortal” is more widespread, and most of the sources in the bibliography use it, that’s what I will employ in the rest of the article, save for direct quotes from Touhou, where "hermit" will be used.

Early history of immortality in Chinese sources