#Mercure des Arts

Text

2024年春の仕事

ここへ来てようやく春らしい陽射しが注いでくるようになりました。それまで福岡では、気温は平年と変わらないものの、重い雲が垂れ込め、時折雨風が強くなる日が続いていて、気分も体調も落ち込むことが多かったので嬉しく思っています。学期の始まりの慌ただしさもようやくひと段落し、溜め込んだ仕事に少しずつ取り組んでいるところです。美学と哲学の講義にも、またこれらを深めるゼミにも熱心な学生がいて刺激を受けています。ゼミではエドワード・W・サイードの晩年の著作を読み始めました。彼が何を問い続けてきたのかを顧みることをつうじて、現在の厳しい状況を見通す思考の方途を探れればと思います。

3月8日に広島交響楽団の演奏会を聴くために訪れた広島にて

さて、3月から4月の仕事についてご報告しておきたいと思います。まず、書評紙『週間読書人』の3月1日号に、郁文堂から昨年末に刊行されたヨアヒム・ゼング編/細見和之訳『ア…

View On WordPress

#Béla Bartók#BBC Symphony Orchestra#Bohuslav Martinů#Christopher Noran#Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper#Erika Kobayashi#Goethe Institut Tokyo#Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra#Kazuyuki Hosomi#Kyoko Hayashi#Makoto Oda#Mayumi Kanagawa#Megumi Fukuda#Mercure des Arts#Nishinippon Shimbun Newspaper#Olivier Messiaen#Oppenheimer#Paul Celan#Peter Szondi#Research Group for Theory of Image#Research in Atomic Bomb Literature#Ryoko Aoki#Sayaka Shoji#Silvan Cambreling#Tadashi Tonoshiki#Tamiki Hara#Tatsuya Shimono#Theodor W. Adorno#Tokimate#Toshio Hosokawa

1 note

·

View note

Text

Héloïse, one of my book's MCs

#les larmes de mercure#the tears of mercury#oc#original character#fantasy#knight#digital art#concept art#characterdesign#i'm really happy with the lineart for once#heloise#héloïse

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAKANDAL BRAISE

La Maison des écritures La Rochelle présente l’exposition Makandal Braise du 10 au 27 juin 2024, une rencontre artistique entre Rolaphton Mercure et Jeanty Junior Augustin.

Cette exposition signe la sortie de résidence de Rolaphton Mercure.

“Dans un de ces enfers fait à la main dispersés aux quatre coins du monde, Haïti, veuve sans seins voilée de lierres au cœur de la mer des Caraïbes, l’humain…

View On WordPress

#art#artiste#écriture#exposition#Jeanty Junior Augustin#La Rochelle#maison des ecritures#Makandal Braise#photographie#Rolaphton Mercure

0 notes

Photo

Lugh

Lugh (également Lugus ou Lug) était l'un des dieux celtes les plus importants, en particulier en Irlande, et il représentait le soleil et la lumière. Bien qu'il ait été à l'origine une divinité omnisciente et clairvoyante, Lugh fut ensuite considéré comme un personnage historique, un grand guerrier et un héros de la culture irlandaise. Lugh porte souvent une épithète telle que Lugh Lámfada (ou Lámfhota), qui signifie long bras ou "de la longue main", en référence à ses prouesses avec les armes de jet, ou Lugh Samildánach, qui signifie "habile dans de nombreux arts et métiers". Il est un personnage important dans de nombreux récits de la mythologie irlandaise, où il mène la course des Tuatha Dé Danann à la victoire contre les marins Fomoires lors de la bataille de Mag Tuired. Lugh tue le borgne Balor à l'aide de sa lance ou fronde magique et instaure ainsi un règne de 40 ans de paix et de prospérité. Lugh ressemble à bien des égards au dieu celte Lugus, que les Romains décrivaient comme le Mercure gaulois.

Lire la suite...

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Habit d'Hiver" estampe attribuée à Jean Bérain et Jean Le Pautre publiée dans la revue "Le Mercure Galant" (1678) présenté à la conférence “S'Habiller au XVIIe Siècle” par Marine Chaleroux - Historienne d'Art - de l'association Des Mots et Des Arts, avril 2023.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avec notre vol arrivé aux aurores, nous arrivons pile poil à l’hôtel pour profiter du petit déjeuner ;) Rassasié, nous pouvons maintenant profiter de notre première journée à Santiago. La ville dégage une ambiance très chaleureuse, les gens chantent, dansent, s’amusent. C’est très agréable de flâner dans les rues animées de la Capitale. Nous commençons la journée par une visite haut perchée. Nous montons au sommet de la tour la plus haute d’Amérique du Sud (ci-dessus en bas à gauche et au milieu à droite). Nous avons une vue imprenable sur la métropole. Et de la haut nous remarquons que Santiago est une ville très verte, et cela ce confirme ensuite au sol, nous ne passons pas une rue dans qu’il n’y ait une belle rangée d’arbres et des allées fleuries ! Nous nous dirigeons ensuite vers le quartier historique de la ville, où nous nous arrêtons pour dîner. Nous visitons ensuite la cathédrale et l’ancien marché central, devenu presque trop touristiques. Il ressemble désormais plus à un hall de restauration plutôt qu’à un authentique marché… Notre promenade se poursuit ensuite dans la rue, entre différents étales de marchandises et de nourritures (attention la fraîcheur surtout lorsqu’ils proposent des salades de poulpes alors que le mercure avoisine les 35* 😂😅). Nous arrivons ensuite dans le quartier “Bellavista”, très populaires pour son street-art ! Tous les bâtiments ou presque sont tagués (un aperçu ci-dessus en haut à droite). C’est aussi de ce quartier que part le vieux funiculaire pour la coline San Cristobal, là où ce tient une gigantesque statue de la Vierge Marie qui surplombe Santiago. Nous décidons ensuite de prendre la route pour aller à l’hôtel pour prendre notre douche avant d’aller souper. Hélas, encore fatigué du “décalage horaire” nous nous endormons…

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Talk of nihilism, catalanism, anarchism, and modernism filled the smoky air of Els Quatre Gats, Picasso's main haunt in Barcelona. Els Quatre Gats was from the beginning a huge success, "a Gothic tavern for those in love with the North," where Uerillo staged puppet shows, where Rusinol, Casas, and Nonell, among other painters, showed their work, and where anyone with an apocalyptic gleam in his eye would gravitate to discuss the new ideas. Enthusiasm contended with a sense of futility, and the urge to create with the compulsion to destroy. The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin was one of the imported heroes of Els Quatre Gats: "Let us put our trust in the eternal spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unsearchable and eternally creative source of all life. The urge to destroy is also a creative urge."

Such was the intellectual milk that nourished Picasso in Barcelona at the turn of the century. Uneducated but quick to learn, he devoured ideas and philosophies through his friends who had read and absorbed them. Nietzsche's Will to Power struck an especially powerful chord in Picasso's heart. Power was the only value set up by Nietzsche to take the place of the transcendent values that had lost their meaning for modern man. And Picasso, for whom transcendent values were associated with Spain's repressive Church, found that Nietzsche's philosophy admirably suited his own needs and dreams of power.

(…)

The summer of 1901 was a demonically creative one for Picasso. The art critic Francois Charles cautioned him "for his own good no longer to do a painting a day," but Paris had unleashed a surge of experimentation in him. It was a summer of reveling in the city, of celebrating his freedom from Spanish conventional morality, of flower still-lifes, cancan dancers, the races, pretty children, and fashionable ladies. Yet a noticeable change was beginning to take place in both his mood and his work. "I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green," Van Gogh wrote in 1888, and in 1901 Picasso, spurred by his inner turmoil, switched his focus to the solitude and pain of humanity and tried to express them by means of blue. So began the procession of beggars, lonely harlequins, tormented mothers, the sick, the hungry, and the lame. And in their midst was Picasso himself, his own suffering on display in a blue self-portrait.

In January of 1902 he returned for a time to Barcelona, where the sometimes despairing, sometimes bitterly tender expressionism of the Blue Period became still more intense. The destitute women of Paris appeared in their Barcelona incarnation utterly crushed by life and a hostile world. In Two Sisters, his painting of a whore and a nun, Picasso expressed for all time his starkly divided vision of women as madonnas or whores. And in his life, having idealized his mother to the point where he could not even bear to talk to the real, imperfect Dona Maria, he spent his time watching, sleeping with, and painting women who in his mind occupied the space reserved for whores. Two of the smaller nude drawings he would keep for his Private collection. On one of them he had written, "Cuando tengas ganas de joder, jode"—"When you are in the mood to screw, screw." In his struggle to define himself as a man, lust seemed the most appropriate emotion toward women.

(…)

His despair was there for all to see in his work. Charles Morice focused on it in an essay he wrote for the Mercure de France while the Weill show was still on.

It is extraordinary, this sterile sadness which weighs down the entire work of this very young man. His works are already numberless. … He seems a young god trying to remake the world. But a dark god. Most of the faces he paints grimace; not a smile. His world is no more habitable than lepers' houses. And his painting itself is sick. Is this frighteningly precocious child not fated to bestow the consecration of a masterpiece on the negative sense of living, the illness from which he more than anyone else seems to be suffering?

It was an extraordinarily powerful piece, and it shook Picasso. He wanted to meet Morice, as if the man who had so accurately diagnosed his state of mind might also be able to provide a cure. Morice, a good friend of Paul Gauguin's, introduced him to Noa Noa, Gauguin's autobiographical poem. Picasso's deep-rooted pessimism was pitted against Gauguin's primitive, questing optimism. "Where are we coming from? Who are we? Where are we going?" Gauguin asked, and although Picasso never formulated those questions in words, they were all there in his work and in the restlessness of his life.

(…)

Matisse thought that Picasso and he were "as different as the North Pole is from the South Pole." While Matisse pursued serenity in his life no less than in his art, Picasso was a mirror for the conflicts and anxieties of his age. Matisse's objective was to give expression to what he described as "the religious feeling I have for life. … What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, free of disturbing or disquieting subjects . . . an appeasing influence." Picasso had no clear intellectual objective, only a vague but all-consuming urge to challenge, to shock, to destroy and remake the world. The fascination they extended over each other was the foundation of the relationship that began in Gertrude Stein's living room and that, despite all its up and downs, lasted until Matisse's death, in 1954. It was the fascination of opposites.

(…)

Cubism was not yet born, but in the fall and winter of 1906 Picasso was definitely pregnant with it. And preparations were under way for the momentous event. He had a canvas mounted on specially strong material as reinforcement and ordered a stretcher of massive dimensions. Years later he talked to Andre Malraux of the moment of conception.

All alone in that awful museum with masks, dolls made by the redskins, dusty manikins. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon must have come to me that very day, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism painting -- yes absolutely! … When I went to the old Trocadero, it was disgusting. The Flea Market. The smell. I was all alone. I wanted to get away. But I didn't leave. I stayed. I stayed. I understood that it was very important: something was happening to me, right?

The masks weren't just like any other pieces of sculpture. Not at all. They were magic things. But why weren't the Egyptian pieces or the Chaldean? We hadn't realized it. 'Those were primitive, not magic things. The Negro pieces were intercesseurs, mediators; ever since then I've known the word in French. They were against everything—against unknown, threatening spirits. I always looked at fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I too believe that everything is unknown, that everything is an enemy! Everything! Not the details— women, children, babies, tobacco, playing—but the whole of it! I understood what the Negroes used their sculpture for. Why sculpt like that and not some other way? After all, they weren't Cubists! Since Cubism didn't exist. It was clear that some guys had invented the models, and others had imitated them, right?

Isn't that what we call tradition? But all the fetishes were used for the same thing. They were weapons. To help people avoid coming under the influence of spirits again, to help them become independent. They're tools. If we give spirits a form, we become independent. Spirits, the unconscious (people still weren't talking about that very much), emotion -- they're all the same thing. I understood why I was a painter.

Everything, the whole of creation, was an enemy, and he was a painter in order to fashion not works of art—he despised that term—but weapons: defensive weapons against the spell of the spirit that fills creation, and offensive weapons against everything outside man, against every emotion of belonging in creation, against nature, human nature, and the God who created it all. "Obviously," he said, "nature has to exist so that we may rape it!"

(…)

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon may have come to Picasso in the Trocadero, but there were Iberian influences, Egyptian influences, and many unconscious philosophical influences whose principal perpetrator was a man scarcely five feet tall, with long black hair parted on his large head and falling on his narrow shoulders, and with mad, deep, black eyes. It was Alfred Jarry, the creator of Father Ubu, who in his play Ubu Roi summed up his philosophy of destruction: "Hornsocket! We will not have demolished everything if we don't demolish even the ruins!" Jarry abhorred every aspect of contemporary society -- its bourgeois pretensions, sham, and hypocrisy—and his life no less than his art was devoted to its destruction. He carried a pair of pistols and contrived opportunities to use them to underscore his social role.

Destructiveness was Jarry's rallying call, and a deep, barbaric destructiveness was at the center of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. When Jarry gave Picasso his revolver, he knew that he had found the man who would carry out his mission of destruction. It was a ritual act and was seen as such by all those present at the supper at which Jarry passed on the sacred symbol. "The revolver sought its natural owner," Max Jacob wrote. "It was really the harbinger comet of the new century." So was the explosion that was named Les Demoiselles d'Avignon: five horrifying women, prostitutes who repel rather than attract and whose faces are primitive masks that challenge not only society but humanity itself. Even the Picasso bande was horrified. "It was the ugliness of the faces," the young poet André Salmon wrote, "that froze with horror the half-converted." Apollinaire murmured about revolution, Leo Stein burst into embarrassed, uncomprehending laughter, Gertrude Stein lapsed into unaccustomed silence, Matisse swore revenge on this barbaric mockery of modern painting, and Andre Derain expressed his wry concern that "one day Picasso would be found hanging behind his big picture."

(…)

In The Republic Plato expelled all artists from his ideal state, because they merely copied nature, which, in turn, was only a copy of the ultimate reality. "In fact," Picasso said, "one never copies nature, neither does one imitate it. … For many years, cubism had only one objective: painting for painting's sake. We rejected every element that was not part of essential reality." As Murry put it,"Plato was seeking for a Picasso." When, in 1912, Picasso painted the first collage of the twentieth century, Still-Life With Chair-Caning, with a printed oilcloth across the bottom of an oval canvas and a newspaper, a glass, a pipe, and a sliced lemon, he was no longer imitating reality but displacing it. "When people believed in immortal beauty and all that crap," he would say, "it was simple. But now? . . . The painter takes whatever it is and destroys it. At the same time he gives it another life. For himself. Later on, for other people. But he must pierce through what others see—to the reality of it. He must destroy. He must demolish the framework itself." It was the beginning of synthetic Cubism, along the path Picasso had embarked on toward an art of essentials rather than an art of imitation.

(…)

A grand Picasso retrospective planned to open at the Georges Petit Gallery on June 15, 1932, gave him an opportunity to be surrounded by 236 canvases that had been gathered in Paris from around the globe. In September of the same year, another grand retrospective opened at the Zurich Kunsthaus. One of the 28,000 visitors to see the show was Carl Jung, and the result of his confrontation with an overview of Picasso's oeuvre was a devastating piece that appeared in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on November 13, 1932. Struck by the similarity between Picasso's work and the drawings of his schizophrenic patients, Jung declared Picasso a schizophrenic, expressing in his work a recurrent, characteristic motif "of the descent into hell, into the unconscious, and the farewell to the world above." Comparing the images produced by Picasso to those produced by his patients, he wrote,

Considered from a strictly formal point of view, what predominates in them is the character of mental lacerations, which translate themselves into broken lines, that is, a type of psychological fissures which run through the image. … It is the ugly, the sick, the grotesque, the incomprehensible, the banal that are sought out—not for the purpose of expressing anything, but only in order to obscure; an obscurity, however, which has nothing to conceal, but spreads like a cold fog over desolate moors; the whole thing quite pointless, like a spectacle that can do withhout a spectator.

Whatever the validity of Jung's insights, it was undeniable that as Picasso entered the sixth decade of his life he was further away than ever from his youthful dream of creating a universal art—not just of achieving mastery in any style and any medium he chose but of transcending all styles to create something absolute and ultimate. He had the courage to die to many different artistic expressions and be born to new ones, but he lacked the courage to let go of the trapeze of his monumental egocentricity and his dazzling personality and trust that there was something beyond himself to catch him. No number of magical canvases and sexual acrobatics could shield him, except momentarily, from his all-pervading sense of doom.

(…)

On July 18, 1936, the news reached Paris that civil war had broken out between the Republican government and the insurgent Nationalists, led by Franco. The murder of the poet García Lorca soon after, at the age of thirty-eight, sent shock waves through the art world. "They are killing men here as if they are cutting down trees," Saint-Exupéry wrote. There was no question that Picasso's allegiance belonged immediately and instinctively to the Republicans seeking to put down the military uprising. But it was Eluard who, in their endless conversations, supplied him with the vocabulary of political indignation that he used in declaring himself for the Republic.

For the first time in his life this grand solitary joined the stream of history. From now on his isolation would be laced with a sense of solidarity and belonging. He even accepted, with alacrity, the offer of the Spanish government to become the honorary director of the Prado. It was the first and the last official position he would ever hold, and it was not so much honorary as symbolic. By then the Nationalist troops were only twenty miles from Madrid, and in August, as Franco's planes began bombing the city, the Prado treasures had to be rushed to the relative safety of Valencia.

(…)

Meanwhile, the insurgent generals in Spain were busy creating, as the Nationalist general Emilio Mola put it, "an impression of mastery" over the country. In order to achieve this, according to Mola, it was "necessary to spread an atmosphere of terror." And since the Republicans continued to control Madrid and most of the north and the east, the atrocities calculated to produce an atmosphere of terror became increasingly vicious and widespread. At the beginning of 1937 Picasso wrote a poem full of violent imagery, designed to ridicule Franco, who was presented as a loathsome, barely human, hairy slug. "Dream and Lie of Franco" was written in Spanish, in his automatic style, which eschewed any rules of syntax or grammar. As he had said to Jaume Sabartés, his longtime friend and secretary, "I would prefer to invent a grammar of my own than to bind myself to rules which do not belong to me." The text was illustrated by eighteen etchings of matching violence, fury, and horror. Franco, the beast attacking Spain, was another emissary of Picasso's arch-enemy, fate.

(…)

And now, thanks to Dora, Picasso had found in "Barrault's loft" a space vast enough for his own most celebrated work. He had been commissioned by the Spanish government to produce a canvas for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World's Fair. As usual, hating the sense of obligation engendered by commissions, he procrastinated, worked on other things, refused to fall into step with his commitment. It took the bombing of the historic Basque town of Guernica, on April 26, 1937, to mobilize his creative frenzy, and then the huge canvas, twenty-five feet by eleven feet, was completed in only a month. In fact, many of the "preparatory studies" were done after the work was finished.

It was the first time that Picasso allowed himself an audience while he worked. Dora was a constant companion, photographing successive stages of the work; Eluard was a frequent witness, watching Picasso, brush in hand, sleeves rolled up, commenting on the progress of Guernica or obsessively talking about Goya. The forty-three German planes that had bombed Guernica had killed 1,600 of its 7,000 inhabitants and had destroyed 70 percent of the town, but the impact of this massacre went far beyond the actual damage inflicted. Guernica, with its ancient oak tree under which the first Basque Parliament had met, became a symbol for the triumph of hatred and irrational destruction, and helped convert a large section of Western public opinion to the Republican cause.

Guernica's power was enormous. It was a distillation of forty years of Picasso's art, with the woman, the bull, and the horse horrified companions in a black-and-white nightmare world. The novelist Claude Roy, a law student at the time, saw Guernica at the Paris World's Fair and described it as "a message from another planet." He wrote, "Its violence dumbfounded me, it petrified me with an anxiety I had never experienced before." The Surrealist poet Michel Leiris summed up the sense of despair engendered by Guernica: "In a rectangle of black and white such as that in which ancient tragedy appeared to us, Picasso sends us our announcement of our mourning: all that we love is going to die. …" Herbert Read went even further: all that we love, Picasso is saying, has died.

(…)

War had been in the air for some time, but on August 23, 1939, when Hitler signed a non-aggression pact with Stalin, it became inevitable. Many of Picasso's friends, including Eluard, had left to join their regiments, and those who remained could talk of nothing but the impending war. Picasso was scared, uncertain about his next move, and, to top it all, angry: "If it's to annoy me that they make war, they are carrying it too far, don't you think?" he complained to Sabartés.

As France mobilized for war, Picasso took care of the many details that went with his galloping success, seeing to numerous exhibitions of his work around the world—especially a grand retrospective of forty years of his art that was to open at the New York Museum of Modern Art in November. As part of the attendant publicity he spent a day posing at the rue des Grands-Augustins, at Lipp's, and at the café de Flore, while Brassaï photographed him for Life. Picasso had mastered the publicity game before the world knew that such a game existed. In fact, in many ways he helped to invent and define it. He had always recognized, and every step of his life had confirmed, a very basic correlation between the money fetched by a painting and the legend built around the painter. And money, for Picasso, was not so much a medium of exchange as the only unequivocal barometer of his success.

After the German blitzkrieg had swept through Belgium and moved on to France, the German army threatened Paris, and it became clear that to stay in the city was to court danger. Picasso decided to go to Royan. Once there, he received news from the gardener at Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre that the house had been requisitioned by the Germans. He waited anxiously for more news, full of fear about the fate of his paintings and sculptures. As soon as the gardener called to say that the Germans had gone on army maneuvers, he took Marie-Thérèse and left for Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre. They found the big pieces of furniture moved to the courtyard to serve as a canteen for the soldiers, and sheets, silk dresses, shirts, and baby clothes used as cleaning cloths. But the aim of the first trip was to salvage the paintings and sculptures. After that, each time the Germans left for army maneuvers, they rushed back to steal more things from the thieves.

War was in his pictures—not this war, not any particular war, but the darkness and the anger and the hatred that cause wars. In June the German army marched into Royan and Picasso painted one of his most brutal and vengeful images of womanhood: Dora as the Nude Dressing Her Hair. The brutality was no less present in his life. He often beat Dora, and there were many times when he left her lying unconscious on the floor. The transformation of the princess into a toad and of sensuality into horror was complete. And in the dog-face portraits he painted of Dora, he completed the transformation of woman into servile animal. As the art historian Mary Gedo put it, Dora, like his Afghan hound Kazbek, "came whenever he whistled." More than two thirds of his work during 1939 and 1940 consisted of deformed women, their faces and bodies flayed with fury. His hatred of a specific woman seemed to have become a deep and universal hatred of all women.

(…)

In February of 1944, the same month that Picasso and Françoise set out haltingly on their journey together, Max Jacob was arrested at Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire and sent to the detention camp at Drancy, a stop on the long journey to Auschwitz or Dachau. On his way he wrote to Cocteau: "Dear Jean, I'm writing this on a train out of the kindness of the gendarmes who surround us. We will very soon be in Drancy. This is all I have to say. Sacha, when they talked to him about my sister, said: 'If it was him, I could do something!' Well, it is me. I embrace you. Max." The restraint of his plea made his agony all the more poignant. From Drancy one last appeal reached his friends in Paris: "May Salmon, Picasso, Moricand do something for me."

His friends had already begun to mobilize all the support they could find. Cocteau drew up a moving letter about Jacob, about the reverence in which he wes held by the French youth, about his invention of a new language that dominated French literature, about his renunciation of the world. And in a discreet postscript he added: "Max Jacob has been a Catholic for twenty years." The appeal was personally delivered to von Rose, the counselor in charge of pardons and reprieves at the German embassy, who, miraculously, was a lover of poetry and an admirer of Jacob's work. Conspicuously absent from the petition's signatories was Picasso. His silence in behalf of one of his oldest and most intimate friends was thundering. When Pierre Colle, Jacob's literary executor, went to the rue des Grands-Augustins to ask him to use his considerable authority with the Germans to intervene in Jacob's behalf, he refused, crowning his indifference with a quip: "It is not worth doing anything at all. Max is a little devil. He doesn't need our help to escape from prison."

On March 6 von Rose announced that he had succeeded in obtaining a liberation order signed by the Gestapo, and a few of Jacob's friends left immediately for Drancy. There they were informed that Jacob was dead. He had died the day before of pneumonia, fatally weakened by the conditions in prison and the freezing cold in his damp, filthy cell. The "little devil" had flown out of his prison through death. Did the Germans know that Jacob was dead when they signed the liberation order? Or was this a genuine reprieve that arrived too late? And would Picasso's intervention have made a difference?

Whenever Picasso himself got into trouble during the Occupation, whether because he was eating in a black-market restaurant when it was raided or because he had his sculptures cast in bronze when doing so was illegal, or -- more serious—because he was caught smuggling currency out of the country, someone was able to hush things up for him. If André-Louis Dubois, in the Ministry of the Interior, was not able to help, he would address himself to Otto Abetz, the German ambassador. And if he, too, was powerless, Dubois would go as high as Arno Broker, Hitler's favorite sculptor, who would appeal directly to Himmler's assistant, the SS general Heinrich Müller. "If you lay a hand on Picasso," Breker warned him at the time of the currency incident, "the world's press will cause such an uproar you'll be left dizzy." He added that if Müller did not sign the documents to put an end to any action against Picasso, he would appeal directly to the Führer. Müller, who knew that on the Führer's orders statues from the squares of Paris had been melted down to provide bronze to cast the works of Arno Broker, knew better than to withhold his signature. In his memoirs Breker recorded what Hitler said: "In politics all the artists are innocents, like Parsifal."

The liberation of Paris, proclaimed on August 25, heralded a turning point in Picasso's life. He was no longer just world famous, no longer merely a legend. He became a symbol of the victory over oppression, of survival, and of the glory of old Europe. He was even asked to provide a drawing for the first page of an album of homage offered to General Charles de Gaulle by the poets and painters of the Resistance. He was a celebrity they could co-opt to add more glamour to their triumph. Having always had a strong preference for symbols over reality, he accepted. There were thousands of anonymous heroes in the Resistance, but Picasso, although certainly no hero, was a monument, as well known as the Eiffel Tower and almost as accessible. He posed for photographs with his favorite pigeon perched on his head or on his shoulder; he welcomed hundreds of American GIs who lined up to visit his studio; he said, "Thank you very much," in a charming Franco-Spanish accent, to offerings of chocolate, coffee, fruit, and tins of food; he answered patiently and graciously over and over again all questions about the length of time it took him to paint a picture, how many he did a year, how many he sold and for how much.

An early visitor to the rue des Grands-Augustins was Ernest Hemingway. Picasso was out, and the concierge, used to everybody's leaving presents, asked if he had a gift to leave for Monsieur. Hemingway went back to his car and returned with a case of hand grenades, on which he wrote, "To Picasso from Hemingway."

At Picasso’s studio a month after the liberation, Eluard, full of conspiratorial excitement, whispered in the ear of Roland Penrose, the English Surrealist painter and collector, "I have great news for you: in a week it will be announced publicly that Picasso has joined the Communist Party."

Picasso's entry into the Communist Party turned into a circus, and one of the more entertaining sideshows was the spectacle of Party functionaries going into contortions to demonstrate why his art, which was anathema to all the official canons of Socialist Realism, was nevertheless great art. They gushed and they cooed, and Picasso responded in kind. "All human expression," he once said, "has its stupid side." In his explanations about why he had joined the Communist Party, he proved it: "Joining the Communist Party is the logical conclusion of my whole life, my whole work. … Is it not the Communist Party that works hardest at understanding and molding the world, at helping the people of today and of tomorrow become clear-minded, freer, happier?"

(…)

The artist Picasso most enjoyed discussing aesthetic questions with was Alberto Giacometti, partly because he was too much of a visionary to think of them purely in aesthetic terms. Giacometti had further earned his secret respect by never fawning over him. The two men visited each other often, and sometimes, like naughty schoolboys, they went to a nearby café and pored over the pornographic magazines that Picasso had brought along.

At other times they discussed their work. "He accepted Giacometti's criticisms," the art historian James Lord said, "but at the same time resented having done so, and the perverse side of his nature—always powerful—led him to make fun of Alberto behind his back. … Making light of the sculptor's anxiety and frustration, he said, 'Alberto tries to make us regret the masterpieces he hasn't done.'"

When he was in a mood to be truthful, Picasso conceded that Giacometti's work represented "a new spirit in sculpture." He displayed a gratuitous meanness, however, one day at Giacometti's studio, when such an expression of appreciation could have made all the difference to Giacometti's livelihood. He was there when, unexpectedly, Christian Zervos, who would devote his life to cataloging Picasso's work, arrived with an Italian collector. Three times Zervos asked Picasso if he agreed with him on the merits of a particular sculpture that he hoped the Italian might buy, and three times Picasso refused to reply.

The result was what Picasso knew it would be. Faced with the conspicuous silence of the world's most celebrated painter, the Italian collector left empty-handed. "He amazes me," Giacometti said once. "He amazes me as a monster would, and I think he knows as well as we do that he's a monster."

(…)

Françoise's decision to abandon Picasso as death drew closer was a symbol of life leaving him, of death displacing the vitality that had always been his hallmark. He talked of her treachery to whoever would listen, as if, through venting his anger, he could master his grief. But he suffered alone, and on November 28, a month after his seventy-second birthday, he stopped talking, took his despair in hand, and started working. He worked feverishly, and in just over two months produced 180 drawings. The poet Michel Leiris called the series a "visual diary of a hateful season in hell, a crisis in his private life leading him to question everything." In these confessional drawings he is not only old and grotesque but ugly, dwarfish, flabby, and pathetic, trying to capture through his art the vitality that eludes him in life. He is extremely skillful, a superb craftsman, full of imagination and wit in all the different ways he portrays his model and himself, but an air of meaninglessness hangs over the whole enterprise of his art. And the young woman in the series, the eternal feminine in many different guises and disguises, knows it. She is amused by him but cannot take him seriously as an artist and certainly not as a lover. She is much more delighted playing with a monkey or fondling a cat, with its fur, as Rebecca West wrote, "soft against her smooth flesh, its nervous energy crackling against her serenity, her faculty of acceptance bringing the little animal into unity with herself. She is as strongly affirmative as a Greek goddess. " She is the tree of life and the tree of knowledge. And the painter's despair is not just that he is an old man who must give up "his place at the feast of sensual pleasure"; it is that he is an old man who will die without knowing why he has lived and why he has painted. Neither his gifts nor his endless sexual adventures have brought him any closer to the secret of life that the young woman seems to know and from which she seems to draw her serenity and her deep acceptance of everything, including the absurd little old man.

(…)

“He had a warrior's mentality," Picasso's cousin Manuel Blasco said. "Fight during the day and fornicate at night." In November of 1965, in conspiratorial secrecy, Picasso was taken to the American Hospital in Neuilly for gall-bladder and prostate surgery. From then on there would be only fighting. For a warrior who had worn his virility like a badge, the end of his sexual life was a terrible calamity. It looked as though the operation might signal the end of his fighting days, too. During the rest of 1965 and up to December of 1966 he drew and he etched, but he did no painting. It was the longest he had ever been away from the battlefield. "When a man knows how to do something," he told the bullfighter Luis Miguel Dominguín, "he ceases being a man if he stops doing it."

He had kept death at bay, but not the despised signals of his inescapable mortality. He had had to give up his Gauloises, his life's most constant companion; his failing eyesight meant that his magnetic gaze was more and more often hidden behind glasses; his growing deafness gave him one more reason to avoid people; and the deep scar from the operation, which, once the curtain of secrecy had been lifted, he defiantly displayed to the few still allowed to visit him, was a constant hateful reminder of what he had lost forever. "Whenever I see you," he told Brassaï, "my first impulse is to reach in my pocket to offer you a cigarette, even though I know very well that neither of us smokes any longer. Age has forced us to give it up, but the desire remains! It's the same with making love. We don't do it anymore, but the desire is still with us!"

The desire and the frustration and the rage and the self-lacerating despair were funneled into his work, and sex in anticipation, sex in action, sex in retrospect became the dominant motif of his painting—once he had sufficiently recovered from what he called the "goring" to start painting again. The reports from Notre-Dame-de-Vie were that Picasso was back to normal -- his own extraordinary normal, of course. In the same way that he had all his life pretended to be an excellent swimmer, he now pretended, as best he could, to be untouched by age. "He only knows how to float and splash about a bit along the shore," wrote Roberto Otero, a bullfighting aficionado who had succeeded in penetrating the fortress of Notre-Dame-de-Vie. "Still, the imitation is so realistic that from a distance nobody could tell if his 'swimming' is authentic or not." And his imitation of being "fresh as the morning dew" was so convincing to all those who wanted to be convinced that the myth of the perpetually vital genius lived on. "One is reminded of the last days of some old vaudeville star: everything, creaking now, is still invented as superlative," the art critic John Berger wrote.

The horror of it all is that it is a life without reality. Picasso is only happy when working. Yet he has nothing of his own to work on. He takes up the themes of other painters' pictures. … He decorates pots and plates that other men make for him. He is reduced to playing like a child. He becomes again the child prodigy.

Picasso was sick, and the couples that filled his work in 1969, kissing, copulating, and suffocating each other, bore the stamp of his sickness. His body was a sack of ills and frustrated desires. The body that had for so long served him so admirably had turned against him. He could not see well, he could not hear well, his lungs fought for breath, his limbs fought for the strength to sustain him, and he fought for the unconsciousness of sleep. But a sickness much more frightening than the inevitable sicknesses of a man close to ninety was the soul-sickness of a man close to death and utterly disconnected from the source of life, a man staring at death and seeing his own fearful imaginings.

On June 30, 1972, Picasso faced the terror that consumed him and drew it. It was his last self-portrait. The next day the art historian Pierre Daix came to visit him. "I made a drawing yesterday," he told him. "I think I have touched on something there. … It is not like anything ever done. " He took the drawing and held it up to his face, and then put it down, without comment. It was a face of frozen anguish and primordial horror held next to the mask that he had worn for so long and that had fooled so many. It was the horror he had painted and the anguish he had caused and which, in his own anguish, he continued to cause. Two months after he drew his last self-portrait, Pablito, his first grandson, tried to see him. He arrived on his motorcycle and showed his identity card. He was turned away, and when he persisted, the dogs were let loose on him and his motorcycle was thrown into a ditch.

On April 1, 1973, Picasso wrote to Marie-Thérèse, telling her again that she was the only woman he had loved. Was he seeing her then as she had first been for him—a vision of beauty and purity, a promise of entering together a forbidden world where abandoned sexuality would lead to a heightened state of being? Or was the letter a Mephistophelian April Fool's joke, the last lie with which to secure her bondage to him, disorient her a little more, and put one more nail in her cross? Perhaps he wrote her from mere force of habit. Perhaps he spoke the truth.

(…)

“When I die,” Picasso had prophesied, "It will be a shipwreck, and as when a huge ship sinks, many people all around will be sucked down with it."

On the morning of Picasso's burial Pablito, excluded from his grandfather's funeral, drank a container of potassium-chloride bleach. He was taken to the hospital in Antibes, where the doctors found that it was too late to save his digestive organs. He died three months later, on July 11, 1973, of starvation.

On October 20, 1977, in the year of the fiftieth anniversary of their meeting, Marie-Thérèse hanged herself in the garage of her house in Juan-les-Pins. She was sixty-eight years old. In a farewell letter to Maya, she wrote of an "irresistible compulsion." "You have to know what his life had meant to her," Maya said later "It wasn't just his dying that drove her to it. It was much, much more than that. … Their relationship was crazy. She felt she had to look after him—even when he was dead! She couldn't bear the thought of him alone, his grave surrounded by people who could not possibly give him what she had given him."

Just after midnight on October 15, 1986, Jacqueline called Aurelio Torrente, the director of the Spanish Museum of Contemporary Art, in Madrid, to discuss the final details of the exhibition of her personal selection of Picasso's paintings that was to open in Madrid ten days later. She assured him that she would be there for the opening. At three o'clock in the morning she lay on her bed, pulled the sheet up to her chin, and shot herself in the temple. She had left behind a list of everyone she wanted at her funeral.

These events were part of the dark, tragic legacy Picasso left behind in his life. The legacy of his art has to be seen in conjunction with the legacy of our time. He brought to fullest expression the shattered vision of a century that perhaps could be understood in no other terms; and he brought to painting the vision of disintegration that Schoenberg and Bartók brought to music, Kafka and Beckett to literature. He took to its uttermost conclusion the negative vision of the modernist world—so much that has followed has been footnotes to Picasso. His tragedy was that he longed for the ultimate in painting and died knowing that it had eluded him. Unlike Shakespeare and Mozart, whose prolific creativity he shared, Picasso was not a timeless genius. He was in fact a time-bound genius, a seismograph for the turmoil, doubts, and anguish of the twentieth century. From the time that he shook the art world with Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Picasso was out of love with the world. He saw his role as a painter as fashioning weapons of combat against every emotion of belonging in creation and celebrating life, against nature, human nature, and the God who created it all. "How difficult it is," Picasso had said soon after his eighty-fifth birthday, "to get something of the absolute into the frog pond." But however difficult, is it not the highest function of art to try to get something of the absolute into the frog pond of this world? With prodigious skill, complete mastery of the language of painting, inexhaustible versatility, and monumental virtuosity, ingenuity, and imagination, Picasso showed us the mud in our frog pond and the night over it. Yet there is a sense in all great art that beyond the darkness and the nightmares that it portrays, beyond humanity's anguished cries that it gives voice to, there is harmony, order, and peace. There is fear in Shakespeare's Tempest and in Mozart's Magic Flute, but it is cast out by love; there is horror and ugliness, but a new order of harmony and beauty evolves out of them; there is evil, but it is overcome by good.

Picasso's advanced age was filled with despair and fueled by hatred. As for his art, he had told André Malraux that "he had no need of style, because his rage would become a prime factor in the style of our time." And his rage has become the dominant style of our time. As we move toward the beginning of a new century, what will Picasso, so irrevocably tied to the age that is dying, have to say to the age being born?”

#picasso#pablo#pablo picasso#huffington#arianna huffington#art#cubism#surrealism#ernest hemingway#jean cocteau

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

初夏の仕事

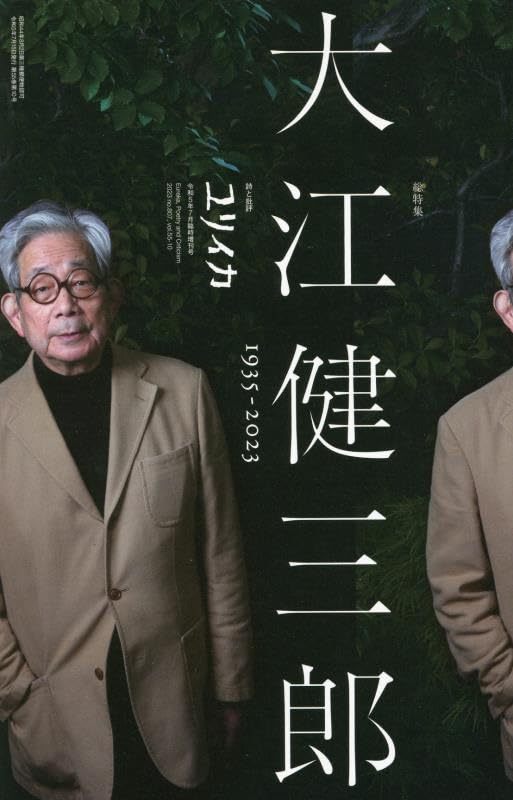

大江健三郎の謦咳に一度だけ接したことがあります。1997年、東京オペラシティのオープニングに際してタケミツ・メモリアルの名を冠したそのコンサートホールで行なわれた作家の講演会を聴きに行ったのでした。当時親交を深めていたエドワード・W・サイードの『音楽のエラボレーション』(大橋洋一訳、みすず書房)の音楽論を大江なりに解きほぐしながら、「エラボレーション」の概念を、テーオドア・W・アドルノがベートーヴェンの音楽について論じていた「晩年様式」の形成とも結びつけていく内容だったと記憶しています。大江自身の問題意識を背景に、サイードの「対位法」の概念にも呼応しつつ、音楽と文学を往還する話は、徐々に沁み入り、心はいつしか熱く満たされていました。

それからおよそ四半世紀以上を経て、今春惜しくも逝去した大江の作品を論じる機会をいただいたことに特別な感慨を抱かざるをえません。6月末に刊行された詩と批評の…

View On WordPress

#Aki Takahashi#Akihisa Kawada#Anton Bruckner#Aoyama Experimental Workshop#Artes Publishing#Ästhetische Anthropologie#Barbara Monk-Feldman#Bildwissenschaft#Christoph Menke#Edward W. Said#Franz Schubert#Jacques Derrida#Kenzaburo Oe#Kraft#Mercure des Arts#Midori Goto#Nobuyuki Kakigi#Seinan Gakuin University#Tadashi Tonoshiki#Tamiki Hara#Tatsuya Shimono#Theodor W. Adorno#Tomohei Hori#Toshio Hosokawa#Walter Benjamin#Wen Yuju#Yuji Numano#Yuji Takahashi

0 notes

Text

UN PRESENTE UN FUTURO Y UN PASADO. Serie de 11 piezas de 3 niveles. 42 x 28 cm c/u Ver +

2024 Desplazamientos, Colectivo A Pie de Página. Banco de Proyectos. FUGA. Bogotá.

2024/23 La Cotidianidad en el Arte, Galería Micelio. Bogotá.

2023 Muestra Soyarte, Cali.

2023 Muestra Soyarte, Casa del Reloj Usaquén. Bogotá.

2022 Exposición Formas y Cromáticas. Hotel Mercure 98, Acero Galería. Bogotá.

2020 Exposición Layover, Maleza Proyectos y Casaducuara, Takaaki KJ Proyectos Curatoriales. Bogotá.

2020 Exposición Bronx la Historia, Espacio Barrio de la Candelaria de la FUGA. Feria Barcú. Bogotá

2020 Exposición Bronx la Historia, Espacio Colección de la FUGA. Feria del Millón. Bogotá.

2020 Exposición BIBLORED Red Distrital de Bibliotecas Públicas de Bogotá. Biblioteca La Marichuela Usme. Bogotá.

2019 Exposición Premio de Fotografía IMAGINARIOS DEL BRONX - Biblioteca Virgilio Barco. Organizado por la Fundación Gilberto Alzate.

2019 Finalista Premio Imaginarios del Bronx, FUGA, Programa Distrital de Estímulos. Bogotá.

0 notes

Text

youtube

A Walking Tour in the Legendary Neighborhood of Montmartre in Paris.

These words come to mind when Paris is mentioned.

travel,blogging,mustafaalgün,vlog,paris,montmartre,walking tour,restaurant,art,accordion,amelie,adele skyfall,bob marley,beauty and the beast,belle et la bete,bakery,bracelet,basilica,dalida,sacre coeur,france,history,sinking house,Rue Foyatier,zaz,je veux,john wick 4,l'amour,moulin rouge,mercure,never again,artists square,125 rue,pink rose,stairs,steps,van gogh,walk around,what to do,where to eat,keanu,loulou,Picasso,love wall,travel guide,travel vlog, alain delon,aligot,anarkia,arc de triomphe,art,baguette,banon,bastille,beaufort,belle,best places,big bus,bisque,bleu d auvergne,blogging,boheme,bohemian,bonaparte,bonjour,bouchees,boudoirs,bouillabaisse,bourguignon,boursin,bretons,brie,brigitte bardot,brocciu,buddha bar,cabecou,caesar,cafe de flore,camembert,canal saint martin,cancoyotte,cassoulet,catacombs,cemetery,cantal,champagne,champs elysees,chapelle,

charcuterie,cheese fondue,cinema,city sightseeing,comte,concorde,creme brulee,croissant,culture,death of diana,day trip,daily trip,daily tour,di,diana,disneyland paris,eiffel,edith piaf,emmental,escargot,esmeralda,eu,europe,elysee palace,exploring,epoisses,fashion,fayette,film,flambee,foie gras,fondue,fourme ambert,fr,france,franciaország,frank,frankreich,frankrijk,francia,fransa,fransa vlog,fransada yaşam,frederic chopin,french cuisine,fromage,galettes,galettes bretonnes,gitanes,gitans,gypsy,gypsies,gallery,gastronomie,gopro,grand palais,grand slam,haute cuisine,henri cartier bresson,hero11,history,holiday,hoponhopoff,invalides,jambon,jean luc godard,jim morrison,la fayette,lachaise,lachaise cemetery,latin quarter,livarot,louvre,louvre pyramid,love,Luxembourg Gardens,lumiere,macaron,marais,maroilles,metro,metropolitain,mimolette,moda,mona lisa,montmartre,montparnasse,moulin rouge,munster,museedorsay,Musée d'Orsay,museum,napoleon,napoleon bonaparte,notre dame,omelette,orangerie,orsay museum,oscar wilde,ossau iraty,palais garnier,palmier,pantheon,paris,parisian,parisienne,paris fashion week,paris france,paris things to do,

#walkingtour#escargot#monalisa#travel#travelvlog#vlogging#travelcontent#gopro#travelvideo#notredame#quasimodo#montmartre#eiffel#louvre#Parisgezirehberi#bestplaces#paristour#vlog#blogging#traveller#seine#seyahat#champselysees#ratatouille#france#wine#parisfrance#parismonamour#napoleon#raclette

1 note

·

View note

Text

神奈川県立音楽堂が主催する「新しい視点 紅葉坂プロジェクトvol.1」に関連するインタビュー記事まとめ。どの記事も、ささきプロジェクトについて言及してくださっています。

2022.5.10 intoxicate 2022 February テキスト:沼野雄司

「神奈川県立音楽堂<新しい視点>ではじまる音楽の逆襲ー音楽の保守性を粉砕して解放する<紅葉坂プロジェクトVol.1>を目撃して欲しい

2022.4.22 FREUDE テキスト:八木宏之

変容を追う 神奈川県立音楽堂シリーズ「新しい視点」紅葉坂プロジェクトVol.1本公演によせて

2022.6.9 ONTOMO テキスト:飯田有抄

新しい発想によるパフォーマンスを公開プレゼン!さらに磨かれた本公演を観に行こう!

下記は講演後のレビュー記事です。

2022.8.15 Mercure des Arts テキスト:齋藤俊夫

神奈川県立音楽堂シリーズ「新しい視点」紅葉坂プロジェクトVol.1

0 notes

Text

Memórias deste Dia: 23 de Abril

Playlist com vídeos deste dia

2022 Viena – Austria

Viena – Hotel Mercure Vienna First

Viena – Câmara Municipal (Wiener Rathaus)

Viena – mumok (Museu de Arte Moderna)

Viena – Museu Leopold

Viena – Biblioteca Nacional Austríaca

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

ARTAIX - les origines

71110 Saône & Loire France

ACCES au NOUVEAU SITE >

Mont Saint Rigaud, Artaix, Saint-Maurice et le Sanctuaire du Mont d’Ajoux

Conférence de Mario Rossi le 01/04/2013 à Propièr

Les Gaulois avaient fondé un sanctuaire au sommet du mont d’Ajoux, aujourd’hui Mont Saint-Rigaud ; ce sanctuaire fut par la suite romanisé. Je voudrais ici tenter d’identifier la divinité à laquelle ce sanctuaire était dédié.

Mais il nous faut retourner en Brionnais, au port d’Artaix sur la Loire.

L’étymologie d’Artaix (M. Rossi 2009, pp. 59-60 et 91-95), prouve que ce fut une fondation consacrée à Mercure, dieu du commerce et des voies d’eau, et qu’Artaix fut un port commercial de toute première importance.

Mais quel dieu gaulois se cache sous le nom du dieu latin Mercure ?

Selon les plus célèbres celtisants actuels (Sergent, Sterckx), ce n’est autre que le grand dieu Lug, connu comme

l’inventeur de tous les arts, dans les mythes celtiques, au même titre que Mercure selon ce que nous en dit César. Ce dieu qui a donné son nom à Lyon, Lugdunum, est également, comme le Mercure latin, le dieu des routes, des voies d’eau, des carrefours et du commerce.

En outre ce dieu Lug, dans la tradition celtique, est nommé Le Voyant. Et dans la tradition gallo-romaine, la compétence de Mercure, donc de Lug, pour la médecine oculaire est bien attestée. Lug, maître de tous les arts, est un dieu polyvalent. Qu’il soit nommé le Voyant n’a rien pour nous étonner car son nom est apparenté à un adjectif gaulois leuk qui signifie brillant. C’est donc Lug qui était, selon toute vraisemblance, la divinité tutélaire de la Fontaine d’Artaix et qui est à l’origine de son nom actuel :

la Fontaine Saint Loup d'Artaix (Fig. 1), fontaine qui est censée guérir les maladies des yeux.

Donc Lug, le Voyant, dieu guérisseur et divinité des sources parce que guérisseur. Mais Saint Loup ? Le nom Lug et le mot gaulois luko, le loup, sont phonétiquement très proches ; leur prononciation, dès le Haut Moyen Age, était dans les deux cas : Leu. Il y eut confusion entre ces deux termes, confusion renforcée par le fait qu’on a cru que le nom du loup, comme celui de Lug, avaient la même origine. Au même titre que Lug, le loup pouvait être considéré comme le Voyant. Ne dit-on pas que le loup, à l’instar du lynx, a une vue perçante ?

Ainsi cette confusion rapprochait Lug de l’Apollon Lumineux, reconnu par les Grecs comme « le maître des loups ».

Cette interprétation Lug-Loup se maintiendra et permettra quelques siècles plus tard, au VII° ou au VIII° siècle, une christianisation de cette source d’Artaix sous le nom de Saint Leu (1), archevêque de Sens (573-623) aujourd’hui connu sous le nom de Saint Loup.

Au Musée de la Tour à Marcigny, on peut voir uns statue de Saint Loup qui porte la mention Saint Loup à l’avers et Lug au revers.

Pour conjurer l’influence néfaste de l’idole, Saint Loup avait, pour les clercs de l’époque, l’avantage d’avoir le même nom et un nom qui laissait espérer des yeux de lynx aux enfants malades.

Mais il y a mieux : parmi ses nombreux miracles, on raconte que le prince Boson se convertit après avoir vu Saint Leu rendre la vue à un aveugle, et après la mort de Saint Leu, une femme aveugle depuis 30 ans recouvra la vue au toucher des reliques du saint (3) !

La christianisation de l’idole Leu en Saint Leu aboutissait ainsi à un échange significatif et donc aisé, pacifique et profitable, échange qui n’empêchait pas, dans les faits, les paysans du coin de continuer leurs pratiques païennes anciennes, puisque le nom de leur idole n’avait pas changé...ou si peu !!!

La continuation des coutumes païennes en effet après la christianisation est chose courante et les fontaines guérisseuses sont encore nombreuses aujourd’hui.

On rencontre ce dieu gaulois Lug ailleurs en Brionnais. On a découvert à Saint-Maurice-lès-Châteauneuf, sur le domaine de La Tour (4), une statue (Fig. 2) et les grands celtisants dont nous avons parlé plus haut ont identifié en cette statue la représentation du dieu Lug (Rossi, 2009, pp. 93-95).

Fig. 2 - Statue du dieu Lug à Saint Maurice-lès-Châteauneuf

.

Fg. 3 - Plan de l’habitat où fut découverte la statue (Fig. 2). Ce sanctuaire semble être la copie conforme du temple gallo-romain de droite.

..

Fig. 4 - Axe sud-est de l’orientation du sanctuaire du dieu Lug à Saint-Maurice.

En pointillés les restes d'une voie antique.

.

Mais il y a mieux. Pourquoi cette ligne vise-t-elle également Chauffailles ?

En réalité, elle vise exactement le Mont Saint-Rigaud (Fig. 5).

.

Existe-t-il une raison à cela ? Voici ce que nous dit l’abbé Comby, selon des notes de l’abbé Louis Chatelet, recueillies en 1942, au sujet du Mont Saint-Rigaud : « Le sommet du Saint Rigaud fut, au temps des Celtes, un des principaux lieux de culte. Tous les ans, il s’y tenait, en été, une grande réunion politique et religieuse. On y venait de grand matin du Beaujolais et du Charolais, on y apportait des offrandes aux dieux, on y exécutait des danses religieuses. Le soir, il y avait réunion et grand conseil entre les chefs de tribus pour discuter des intérêts de la tribu, de la paix ou de la guerre.» (5). Autrement dit le Saint Rigaud, comme Meulin, Milan, etc. était un sanctuaire du Milieu où se réunissaient une fois l’an les tribus des environs.

On y célébrait un culte et, comme à Artaix, il y a là une fontaine guérisseuse dont l’eau possède une « vertu secrète et indéfinie » (Comby, p. 170) !

Ce sanctuaire, comme le prouve l’orientation du temple de St Maurice, devait être consacré lui aussi à Lug-Mercure, Lug guérisseur, tutélaire de la source. Cette orientation du sanctuaire de Saint Maurice vers le sanctuaire du Milieu au Mont d’Ajoux semble montrer en effet qu’il existait un lien étroit entre ces deux pôles, un lien religieux ; il n’est donc pas interdit de penser que le culte à Lug-Mercure au sanctuaire du Milieu du Mont d’Ajoux est antérieur à celui rendu à la source d’Artaix.

On peut alors se poser la question de savoir si on prêtait à la divinité du Mont d’Ajoux le même pouvoir qu’à Lug, le Voyant, à Artaix ?

Il ne semble pas. Comme on l’a vu, Lug, à l’instar de Mercure, était un dieu polyvalent aux multiples pouvoirs ; c’est ce dieu polyvalent qui devait présider à la source dont l’eau avait « une vertu secrète et indéfinie ». Ce sanctuaire a été par la suite romanisé : on peut penser que les Gallo-romains responsables de ce renouveau du culte insistèrent sur le culte à Mercure. On sait en effet que les Arvernes, non loin d’ici, avaient fait construire un Mercure géant au sommet du Puy de Dôme : un Mercure, surnommé roi des Arvernes.

Nous sommes, avec Artaix, La Tour et Saint Rigaud en présence de lieux de culte au grand dieu Lug-Mercure, lieux de culte qui perpétuent la mémoire des mythes celtiques.

Ces sanctuaires, par voie de terre ou par voie fluviale, devaient être en contact permanent à cette époque. La présence de ces lieux de culte est un témoin précieux de la vitalité des échanges culturels et commerciaux entre les Arvernes, les Ségusiaves et les Éduens et sans doute entre Lugdunum, le Mont d’Ajoux, sur la voie de Lugdunum, et les Briennenses.

Ici aussi, comme à Artaix, lors d’une première tentative de christianisation, le Leu gaulois devint Saint Leu, c’est-à-dire Saint Loup !!! Et c’est ce Leu ou Saint Leu que les foules continuaient à vénérer dans le sanctuaire gallo-romain, près de la fontaine guérisseuse, et dont on retrouve le nom beaucoup plus tard, dans Saint Loup d’Aujoux, ou Saint Loup d’Ajoux…sans savoir d’où il venait (Comby, pp. 85, 169) !!! La première christianisation de ce sanctuaire dédié à Lug-Leu dut avoir eu lieu après la mort de Saint Loup, c’est-à-dire entre les années 650 et 700 (voir note 1).

Comme on l’a vu pour Artaix, cette christianisation n’empêchait nullement les paysans de continuer à vénérer leur divinité tutélaire Lug-Mercure : Saint Leu n’était qu’un masque, mais un masque tout à fait adapté à Lug-Mercure. Saint Leu en effet, comme il est écrit dans le Légende dorée, brilla par ses nombreux miracles, en voici un aperçu que l’on peut lire dans la Vie des saints des Bollandistes :

« Et il se fit beaucoup de miracles à son tombeau, une femme aveugle depuis 30 ans y recevra la vue ; une autre femme paralytique y fut guérie ; un prêtre, qui s’était brisé le corps…fut rétabli en parfaite santé. Il est invoqué principalement pour la guérison du mal caduc… et pour le soulagement des entrailles que (sic) souffrent les enfants. » (6).

.

Publication : Patrimoine du Haut Sornin

Acces au site :

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Guillaume Apollinaire, Il Pleut, in Calligrammes. Poemes de la paix et de la guerre (1913-1916) [avec un portrait de lauteur par Pablo Picasso grave sur bois par R. Jaudon], Éditions Mercure de France, Paris, 1918 [Yale University Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, CT]

#graphic design#art#poetry#calligram#book#guillaume apollinaire#pablo picasso#r. jaudon#éditions mercure de france#yale university library#beinecke rare book and manuscript library#1910s

89 notes

·

View notes