#Ordovices

Text

Mogeko March 2023 (1)

#海底囚人#funamusea#okegom#taffy (mogeko)#zero (mogeko)#fumus (mogeko)#aes (mogeko)#rosemary (mogeko)#more ordovices#inga (mogeko)#yuu (mogeko)#moge ko#emalf (mogeko)#rock (mogeko)#fukami (watgbs)#sullivan (mogeko)#youran (mogeko)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue Bloods/Black Bloods

#art#oc#original characters#original character#transcendence#Cornovii#Ordovice#sketch#scribble#rkgk#digital art#iPad art#Apple Pencil#procreate art#procreate

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I imaging you know, but do you think people generally know that the Cambrian with all its funky animals is named for Wales? I feel like it is an underutilized fact. (granted they didn't know about the funky animals when they named it)

Probably not. The Silurian and Ordovician eras too, actually - the Silures were the Insular Celtic tribe that lived in South Wales, the Ordovices in mid-Wales. Wales does a very good line in Rocks.

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mogeko Castle location + Kurokawa [thesis]

Amongst all the puzzling, mystifying things DSP has about their characters, worlds and relationships to one, something thing that has always stuck out to me, and to a lot of other people, is the fact that apparently, contrary to popular belief, Mogeko Castle is not located in the Pitch Black World/Land of Roots, but somewhere else entirely. Sure begs the question - where is it then?

Well, one of its potential locations could possibly be in More Ordovices’ (aka. Tapir God’s) world.

The very first image that comes to mind is the one where he’s seen pouring from this mug; an alligator and a bunny type of creature + a mogeko.

Nataka Kurokawa & Imika Yuhijma are the only ones who are seen riding on the train with Yonaka at the beginning of the game, and not any of the other characters. We don’t know how it traveled from the human world to Mogeko Castle specifically, possibly by either some magic intervention, or the human world where Yonaka is from (seeing as there is more than one - Victor Flankenstein, for example, lived on an entirely different human world before it was destroyed) is specifically connected to Tapir World.

Another familiar, recognizable character, yet from different places; Why is Kurokawa, the mysterious, largely unknown entity, in Tapir world specifically, and not anywhere else? We can assume Kurokawa & Nataka are connected to one another with their similar appearance & the exact same surname.

I would not put it past for Nataka to eventually have gone through with it and actually have committed suicide at some point, considering how often she’s depicted with suicidal/self-harming imagery.

(The hand reaching out to her could be someone offering her a change at starting over her life?)

If they are one and the same, then why are Nataka & Kurokawa being shown as two separate characters instead of one individual? On the character page of Funa's website, Kurokawa is in the 'unknown' category, while Nataka is in the 'human' one. We’ve already seen reincarnation is possible in DSP’s worlds. (The TGG ancestors as an example; on a fundamental level, their descendants are technically the same persons as they are, while the gray village girls are still their own person and not just a copy of their ancestors.) As such, Kurokawa might be a reincarnation of Nataka, but now that she's More Ordovices' creation, she isn't fully 'human' like she was before.

The creatures in More's world are mostly based off of fairytale characters, so it feels Like an ‘Alice in Wonderland’ type of situation for Nataka, except less child friendly for obvious reasons.

A popular running theory that used to float around in early days of Funa fandom was the idea that Rose Murder and Imika Yuhjima are related to one another, taking into account some of their physical/visual similarities. Similar deadpan expression, similar eyes, similar hair.

If Rose Murder is in Tapir world, then Imika could have received the aid from Rose to resurrect Nataka and bring her over to a different world. Imika has a canonical crush on Nataka, so aside from just being friends, Imika has another reason to go to extreme lengths to want to bring her back.

That being said, Nataka and Imika being on the train together at the beginning of Mogeko Castle could be a subtle hint towards the possibility of them having a connection to Tapir World.

it's possible the world surrounding Mogeko Castle isn't ruled by a God at all, but only by king mogeko. It's not entirely clear how massive the land surrounding Mogeko Castle is, as Yonaka spends majority of time inside the castle, and only goes on a somewhat linear path towards it at the beginning of the game. There is no way to explore anything beyond that, unlike in The Gray Garden.

If it isn't located in any specific world, then that opens up an entire can of worms to try to unravel, but might also explain why the ending sequence after Yonaka exits the castle on floor seven doesn't follow a linear path of time; waking up at the train again and seeing Defect Mogeko's blood on her hand. (unless you believe the theory that she just hallucinated the entire encounter with her brother.)

So, passage of time might work differently in a world not reigned over by a god.

In conclusion, my money is on either:

1) Mogeko Castle is located in the Tapir World.

2) Mogeko Castle is not located in any world ruled over by a God. It is instead entirely its own land under the reign of King mogeko (or Lord Proscuitto, depending on the ending/timeline).

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOODHOUND KNIGHTS - INFERENCES & TRIVIA

A follow up to my previous Bloodhound Knights post, this time, as the name of this post suggests, focusing on things that aren’t explicitly stated, even if they are likely, as well as just bits of trivia. Outright theories and headcanons will be relegated to another post. Again, a bit long, so this is going under the cut.

Bloodhound Knight locations total to 8. There is 1 in Limgrave, 1 in Caelid, 3 in Liurnia, and 3 on Mt. Gelmir.

The Bloodhound Knight that can be summoned by Rennala in her second phase was quite possibly a late addition to her fight, along with the wolves, as neither summon has associated dialogue, unlike the dragon and troll. Additionally, there is cut dialogue for Rennala summoning Blaidd. This implies the Bloodhound Knight and/or wolves were added to replace the cut Blaidd summon, but it is unclear why this decision was made.

Darriwil and Floh seem to be named after the Darriwilian and Floian stages of the Ordovician period. There are 7 total stages in this period, and with 8 total Bloodhound Knights, this further supports the idea of Rennala’s summon possibly being a late addition, as the adjacent Silurian period has 8 stages.

The other 5 stages of the Ordovician are the Tremadocian, Dapingian, Sandbian, Katian, and Hirnantian. It is worth noting that Elden Ring characters named after geologic time scales are directly named after the time scale instead of what that name is derrived from (e.g. Floh, Ordovis, and Siluria are named such instead of Flo, Ordovices, and Silures respectively).

Floh is also the German word for flea, though it’s unlikely this was an intentional factor in his name given the stronger connection to geological stage.

It’s all but explicitly stated that Darriwil directly served Ranni, or at least the Carian royal family in general, due to Blaidd referring to him as a traitor. Though, the fact that Darriwil is a traitor in the first place is odd, as the description of the Bloodhound Knight Set states they are “loyal for life”.

The meaning of the word forlorn has potentially interesting implications for Darriwil, with his imprisonment in the Forlorn Hound Evergaol. Merriam-Webster lists the meanings of (1a) “bereft, forsaken”, (1b) “sad and lonely because of isolation or desertion, desolate”, (2) “being in poor condition, miserable, wretched”, and (3) “nearly hopeless”.

#elden ring#bloodhound knights#bloodhound knight darriwil#bloodhound knight floh#placeholder talking tag

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#prehistoric#prehistory#rhinogs#rhinogau#northwales#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#ice age#Ordovices#stone age#bronze age#standing stones#stone circle#cairn#cromlech#dolmen#creative#education#creative writing#community#identity#belonging

36 notes

·

View notes

Link

Just posted a new poem on my companion site if you would like to take a look. :)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“the branwens are native bc they’re a tribe!!”

raven & qrow are literally snow white. their last name is also BRANWEN. a celtic name of welsh origin. you know what else the celts had?

tribes.

plenty of them.

in fact by the by the time the romans invaded britain, there were four major tribes in the area known as modern day wales. the ordovices, deceangli, demetae & silures. instead of going for a harmful native savage allegory in the branwen tribe who are a bunch of murderers, thieves & pillagers; you could just acknowledge the celtic origins of the branwen twins & their tribe. same with acknowledging rwby’s orientalism with raven in putting her in japanese attire when she’s meant to be a white character in every other aspect. especially with the fact that japanese society was buit on clans, not tribes.

#rwby#raven branwen#qrow branwen#branwen tribe#owl.txt#im begging the fandom to think through the unfortunate implications#of their headcanons for FIVE minutes

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caratacus, sometimes known as Caractacus, was an ancient British king of the Catuvellauni tribe.

He is best known for his pivotal role in resisting the Roman invasion of 43 CE. However, it may indeed been Caratacus himself who triggered the invasion in the first place, though it must be said that the Romans were already looking for an excuse to invade anyway.

In the decades prior to the Roman invasion in 43 CE, the Catuvellauni appeared to have expanded, growing to become the dominant tribe in south-eastern Britain.

Some of this expansion came at the expense of the neighbouring Atrebates. The war was started by Caratacus’ father Cunobelinus, continued by his uncle Epaticcus and finished by Caratacus himself. The conquest of the Atrebates led their king, Verica, to flee to Rome where he requested assistance in regaining his throne and thereby giving the Romans the excuse they sought.

40,000 Roman troops landed on the south coast. Caratacus and his brother Togodumnus became the leaders of the resistance and they met the Romans in battle along the Medway and Thames rivers. Defeated both times, the territory of the Catuvellauni was conquered. But Caratacus himself was not.

He fled to the Silures in southern Wales. Together with the nearby Ordovices, Caratacus continued to resist the Romans, this time with greater success. Seven years later, the new Roman governor finally managed to bring Caratacus to battle and defeated him, though the man himself once again escaped.

This time he fled north to the formidable Brigantes, the most powerful tribe in southern Britain. But their Queen Cartimandua was in no mood to fight the Romans. She handed Caratcus over to his great enemy.

Caratacus was sent to Rome as a war prize, something that typically ends with ritual strangulation. However, for unknown reasons Caratacus was allowed to speak to the Senate, including Emperor Claudius himself.

Apparently he made such an impression that he was pardoned and allowed to live in relative comfort in Rome for the rest of his life.

Upon exploring Rome, Caratacus is said to have asked “And can you, then, who have such possessions and so many of them, still covet our poor huts?”

#history#real history#military history#ancient history#ancient rome#roman empire#roman history#rome#british history#ROMA series

62 notes

·

View notes

Link

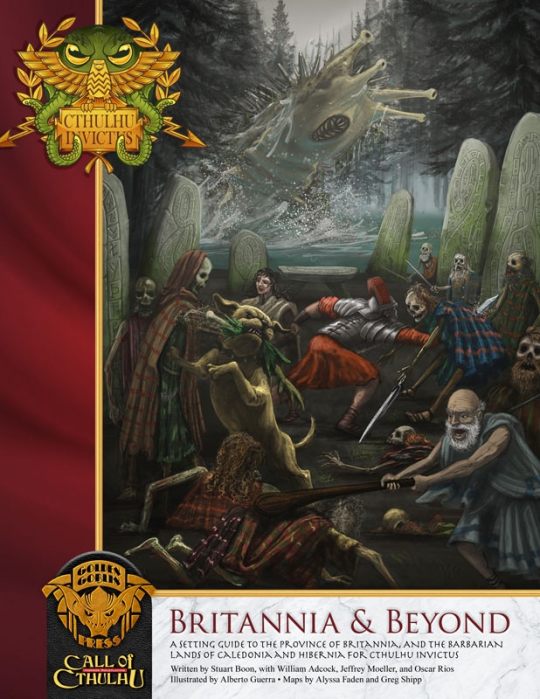

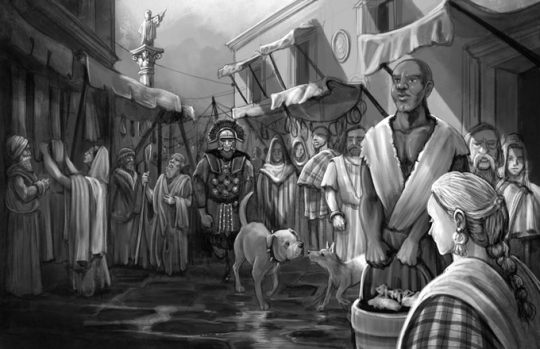

Welcome to Britannia and Beyond!

A regional guide for the Cthulhu Invictus™ setting detailing the province of Britannia, and the barbarian lands of Caledonia and Hibernia

‘Britannia is the border, the furthest outpost of Empire, bounded by cruel Oceania on all sides… what lies beyond that border, what crosses and passes unseen… those things concern me more than any barbarian tribe, more than any army of men… yes, you are right to worry about approaching that border, for what waits in Britannia and beyond… is said to be the doom of Rome.’ – Vatia of Rhodes, 54 AD

The earliest accounts of Briton the Romans saw were from Greek writers, such as Horace, who wrote ‘the shores of the distant Britons’ lay where ‘the real world came to an end and the world of unknown peoples and mythical creatures began.’ To even approach those shores, Horace writes, the Romans would have to cross ‘the stream of Oceanus, filled with large numbers of sea-monsters.’ And so, the island remained a complete mystery, shrouded in shadow and fog.

But eventually the expanding Roman Empire crossed that ocean, and through hard battles and bitter campaigns enveloped Britannia into its borders. Today (96 CE to 180 CE) the province of Britannia is a place of contradictions, a clash of peoples, cultures, and ideologies. It is a land marked by conquest and brutal oppression, but also by peace, productivity, and great progress. Its citizens enjoy prosperity and health, but to most Romans Britons are still seen as unwashed and uncivilized barbarians, the ‘Britunculli’ or ‘nasty little Britons.’ It is a land, and a people, who are slowly forming a new identity, often at odds with themselves.

But there is another truth, another history: one that predates human existence which is unseen by all except a chosen few. The Shadow War. Humanity’s battle against alien gods, their servitor monsters, and the depraved humans who serve them both or exploited them for personal gain, has raged on for millennia. For centuries, this war in Britannia was mostly contained, the dark forces kept dormant through a combination of rituals, ancient magics, and powerful seals erected over the doors of various mystical prisons.

But the coming of the Romans and their Empire changed all that. With the destruction of the druids and their faith, a darkness long kept at bay is now returning. Spells and rituals are no longer performed, protective groves have been burned, sacred stones toppled, and the prison doors to many dark gods now stand open. These entities seek to spread their dark influence, from the new “colony” cities and wealthy villas to the simplest villages of thatch roof huts and century old farms, from the most powerful elite to the lowliest of slaves. Nowhere and no one is safe from their vile machinations.

This misty, mysterious island is the latest front line of the Shadow War. At the edge of the Empire, a new history waits to be written: one of adventure, but also madness, of glory, but also unspeakable horror. Welcome to Britannia and Beyond.

Three years and five Kickstarters ago we were lucky enough to bring Cthulhu Invictus back to the world of Call of Cthulhu, updating it for 7th Edition. That book proved to be quite difficult and time consuming, but the end result proved worth all the effort. We are deeply proud and grateful that it was honored with the 2019 Silver ENnie for Best Supplement at Gencon.

We caught our breath to play with some cats (Tails of Valor), make a stand for justice (An Inner Darkness), and remember our childhood (The Lovecraft Country Holiday Collection), but through it all, we planned our return to the setting we hold so dear. That time has come at last. The Shadow War never ends, and dark things stir on this rainy island on the edge of the known world. It’s time to set sail for Britannia and Beyond!

The scholar Zosimos, Lady Dexia of the Vestal Virgins, and the centurion Galarius Rufus along with his loyal hound Brita sail towards Portus Dubris, and the misty, mysterious province of Britannia. For Brita, the war dog, this is a homecoming of sorts.

For our first setting book for Cthulhu Invictus, Britannia was an obvious choice. With the rich, often tragic, history of the Roman conquest and colonization of Britannia, the fascinating cultural and social results of the blending of so many diverse cultures, and the enchanting folklore of the ancient Celts… one might ask, how could we NOT start with Britannia? From the Roman baths at, well, Bath, to the Antonine (and yes, Hadrian’s) Wall(s) in the north, from Stonehenge, to London (or is that Londinium?), Tír na nÓg and the Sidhe, the savage Picts of Caledonia in the north and bloodthirsty Hibernian raiders from across the western sea, to the dark tapestry of Great Old Ones connected with Britain (especially its Severn Valley). The attraction to delve into these things and create a version of what Britannia is like in the world of Cthulhu Invictus was completely irresistible. So, here we are!

This well researched and comprehensive guide will provide keepers everything they need to take their Cthulhu Invictus campaign to the province of Britannia, and possibly beyond. The book covers:

1. A detailed history of Britannia, from pre-history to the end of the Antonine Period of the Roman Empire (180 CE).

2. Details on Britannia’s climate, geography, natural resources, and economy.

Today, the streets of a rebuilt Londinium look much like any other provincial capital in the Empire, maybe a bit cloudier than most.

3. Information on the Roman government, including the military legions stationed there, including both past and current client kingdoms.

4. Tips for creating characters living in Britannia, from Roman settlers, to Romano-Celtic natives (Latinized natives), and native Celts, with a list of Celtic names and gender-naming conventions.

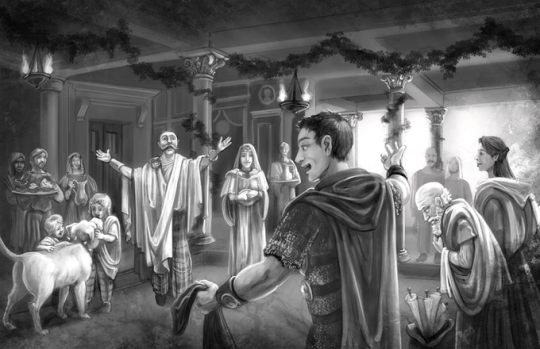

Our heroes and heroines arrive at the home of Veldicius, an old friend of Galarius Rufus from their days serving with the Legio XX, many years ago.

5. A guide to the province of Britannia by region, describing its distinct cultural outlook, the tribes native to the region (and their attitudes towards Rome), important cities and towns, notable sites, sinister seeds, mythos threats, and more.

Paying a courtesy visit to (and seeking advice from) Queen Caratacae of the Dobunni, ruler of one of the few remaining client kingdoms of Britannia.

6. Information on the religion, folklore, myths, magic, temples, and sacred sites associated with Britannia, including Druidism and new rules for creating Druid characters.

7. A collection of patrons, investigator organizations, and sinister cults located across Britannia.

8. The Britannia Bestiary, a listing of the native plants and animals, as well as mythos entities drawn from traditional folklore viewed through cosmic horror colored glasses.

The wilds of Britannia can be a dangerous place, with forests old and dark, where older and darker things lurk.

9. The Dark Gods of Britannia, a discussion of the most iconic Great Old Ones and Outer Gods found across the province, including Eihort, Gla'aki, Y’golonac, Byatis, Yegg-Ha, The Keeper of the Moon Lens, and more.

Britannia is home to many dark and dangerous gods, and since the coming of the Romans, the powers of those gods are not only growing, but spreading.

10. A discussion of The Dreamlands, Tír na nÓg, and the mysterious Sidhe.

11. A listing of new mythos tomes, magical artifacts, and spells.

New Roman roads are only a good idea if they avoid places no one should ever go. Getting the engineers and bureaucrats to change their "well laid out plans" is seldom an easy task.

12. Beyond the Wall and Across the Sea: the barbarian lands of Caledonia (Scotland) and Hibernia (Ireland), detailing their people, the conditions there, and the rules for creating characters from these far off lands.

Walls alone won't protect the Empire from its enemies, human and otherwise. Sometimes, it take courage, steel, arrows, and a fair amount of blood!

13. A pair of scenarios set in Britannia, allowing Keepers and players to dive right into daring and horrifying adventures in this misty land on the edge of the empire.

A Mortal Harvest by Oscar Rios - Shortly before harvest, three villages of the Ordovices suddenly abandon their homes and head towards the city of Viroconium. The investigators must delve into this refugee crisis and get the Ordovices to return to their homes and bring in their crops, lest they face starvation come winter. The Ordovices are too terrified to do so because of a mysterious figure singing haunting ballads under the cover of night. He strums upon a harp, singing a tale of an army of the dead serving a dark god, and warning of their impending doom should they remain.

The Long Dark by Oscar Rios - Just south of the Antonine Wall, in the village of Trimontium, an old friend needs help. An old army buddy, Caito Lupis, retired from the legions and settled down. He's gotten married and begun farming on the land given to him in return for his 25 years of service. At least, that's what he's trying to do. For the Romans, it is time to harvest, but for the natives it's a sacred time, the start of their New Year, a time when ghoulies and ghosties and long legged beasties are free to enter our world. It seems that some of these creatures are set on ruining your friend's harvest and driving him off his land.

==========================================================

Kickstarter campaign ends: Mon, April 13 2020 5:00 AM BST

Website: [Golden Goblin Press] [facebook] [twitter]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s talk tactics: Highland Charge

The Scottish Highlands historically has maintained its own unique culture which touches on virtually all aspects of life, food, drink, fashion, family, religion and even warfare. In the art of warfare the Scottish Highlands contributed in two ways one its rugged topography leading to a guerilla style of warfare and two in its infantry tactics and one that conjures almost a romantic vision, the Highland Charge. Before we discuss the tactic itself, we need to know the history of the region from ancient times until the modern era and how topography and tradition shaped the Highland Charge.

Historically, Scotland has been viewed by many an invader to be wild and untamed land. This was true of the Romans during the age of Roman Britain from the 1st-4th centuries AD. The Roman legions encountered a number of various Celtic tribes that caused them troubles in the modern day regions of England, Wales and the Lowlands of Scotland. The areas that often leant the Romans the most difficulty were areas of rugged topography, namely the Britons of Wales in particular the Ordovices and Silures of the mountains of North Wales and valleys of South Wales respectively. Topography in war is a sometimes underappreciated part of strategy and it took many years and much loss of life and the development of forts and garrisons to finally subdue these tribes in Wales. The same can be said of the Highlands of Scotland. The Lowlands known to the Romans as Caledonia was conquered but this remained the greatest extent of Rome’s northward expansion. To the north in the Highlands with its rugged mountains, hills and many glens were a related but distinct Celtic people, the Picts, who spoke a language identified as Celtic but somewhat distant from the Common Brittonic southern tribes.

The Romans associated the Picts as pirates in later Roman Britain along the coasts and fierce warriors in the interior of the country, conducting raids and disappearing into the Highlands before the Romans could send legions after them. Rome’s response to this was to build and garrison Hadrian’s Wall along the modern English/Scottish border. The Picts were never subdued by Rome unlike the rest of Britain and this was to have a ramifications overtime and echoes throughout history in the Highlands in which they resided.

In time as the lower portions of Britain saw the Romans retreat, leaving the Romano-Britons to their own defense and the subsequent establishment of the Welsh and Cornish as distinct Celtic nations so to would the Picts meld with their fellow Gaels from Ireland and Western islands of Scotland’s coast giving birth to the modern Scots. While the southern Britons in the start of the Middle Ages faced the Anglo-Saxon threat. The Scots merged into their own kingdoms with the Gaels becoming overlords of the Picts and eventually both Celtic confederations synthesizing into one distinct entity.

In time Scotland, like the rest of British Isles was subject to Viking raids and the establishment of Viking petty kingdoms, but unlike England and even parts of Ireland, Scotland’s Viking rule was largely relegated to the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland islands on its periphery, the Highlands and much of lower Scotland remained the Scots Gaelic speaking land that forged out of the blending with the Picts. The topography of the Highlands as always contributed to this isolation.

As the Middle Ages wore on, the Kingdom of England would see troubles in its attempts to subdue Scotland, especially of note was the Scottish Wars of Independence against England under Edward I and Edward II of England. Despite some English successes their overall rule of Scotland remained somewhat limited due to in part to Scotland’s difficult to manage geography and its Clan system.

The Clan system had been a tradition found in Scotland and Ireland throughout the centuries, an important dynamic that social groups were built around. The Highland clans had a fierce sense of independence from both the English and Scottish crowns and from each other at times, alliances were formed and rivalries as well. Murder, warfare alternating with peace and cooperation were part of Clan lifestyle throughout the centuries. The romantic and distinct image of the kilt and tartan clad Highlander Clans really forged in the 15th-17th centuries. Gradually, English rule, settlement and influence over the Lowlands of Scotland lead to the spread of the English language being spoken along with a distinct derivative Germanic language called simply “Scots” quite separate from this the Highlanders retained their Scots Gaelic language and Celtic traditions. Once again geographic isolation a contributing factor.

The Highlander Clans alternated their allegiance to the Crown of Scotland when it suited them. Some clans would rebel against the Crown while others supported them, less out of honor bound duty to the king and more pragmatically for the chance to rid themselves of a rival and gain riches and territorial expansion for their own clan. Clans were led by chieftains who in time were granted titles of nobility and rewarded with wealth and land for their service to the Crown. Highlander Scots became famed for their prowess in combat and became mercenaries throughout Europe, serving in various armies at various times. Some Highlanders became involved in England’s conquest of Ireland, namely after the Elizabethan era establishment of the Plantation of Ulster in the North of Ireland, Highlanders would side with both the native Gaelic Irish and English and Lowlander Scots depending on motivation ranging from cultural and familial ties to money and the promise of wealth. Ultimately, the English gained control over Ireland and the Scottish Highlanders added to the mix with Lowlanders and English to form the Scots-Irish or Ulster-Scots community of Northern Ireland.

By the late 17th century Scotland had much upheaval due to Stuarts of Scotland becoming the royal dynasty of England as well. They remained separate kingdoms under one monarch. The War of Three Kingdoms and the English Civil War along with religious fervor all caused Highlanders to alternatively suffer and profit, largely depending on which winner they would back. By the year 1688, James II of England/VII of Scotland with his Catholic leanings was overthrown and in the so called Glorious Revolution by his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband and his Dutch nephew and her cousin William, Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. They were crowned William and Mary of England and a de-facto personal union now existed between the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, Ireland and the Dutch Republic. James II/VII fled to France and later to Ireland to conjure up support among the Irish Catholic populace in hopes of regaining the throne, he also raised some support from loyal Scots and French soldiers too. This started the Williamite War, the British theater of the Nine Years War. William III of England now forged an army of Protestant forces made of English, Scottish, Irish, French, Dutch and Danish troops. Famously in 1690 at the Boyne River north of Dublin, Ireland, James and William’s armies met. However, the better trained Protestant forces won the day and James fled Ireland ultimately returning to France. However, he never accepted in theory that he or his direct Catholic descendants were not the rightful rulers of Britain. This was to have repercussions in the form of the Jacobite Rebellions and it would play out its final stages with the Highlander Scots and the famed Highlander charge.

The House of Stuart tried to regain the British throne in exile with French support in the early 18th century. William and Mary had no children and they were succeeded by James other daughter, Anne. Anne like Mary and William was raised Protestant and under her rule Great Britain was formed with the 1707 merging of the Crowns of Scotland and England officially as one with a single parliament based in London as opposed to a separate Scottish one as had been the case for the last century. Anne in turn passed away without an heir and was replaced by her closest Protestant relative, the Elector of Hanover from Germany, now George I of Great Britain.

The Jacobites were supporters of the Stuart royalist cause in exile and hoped to restore them to the throne of Britain. Jacobites were so named for the Latin name for James was Jacobus. Jacobitism as an ideology had Stuart restoration as it central tenant but the individual motivations were varied largely depending on the country the Jacobite supporter was located in. In Ireland, it was support for a Catholic monarch in and the promise of religious toleration that James II had granted earlier. In England and Wales a Catholic minority showed Jacobite support but largely its greatest support was found among royalist conservatives or Tories who believed in the divine rights of kings and felt the Glorious Revolution had been an unlawful usurpation and was in violation of what they saw as God’s natural order. Nevertheless, the vast majority of England and Wales were Protestant and anti-Catholic so it is a matter of academic debate among historians just how strong Tory support of Jacobitism really was. In Scotland the reasons were also varied. For some, the Jacobite cause was in solidarity amongst the Scottish Catholic minority. For Highlanders, their own feudal Clan system prized a tradition of feudal service to a landlord, namely the King. Despite the Highlanders varied legacy of service and opposition to the King was a matter of pragmatism but the essential relationship between Highlander Clans and the Crown was still rooted in a traditional belief in the divine rights of a monarch as feudal landlord of all Scotland and the Clan chieftains were loyal subjects granted a certain degree of autonomy in exchange for their recognition of King’s nominal authority and service to the Crown in times of need. This established a looser form of nobility than the later English influenced tradition. However, the traditional ideological and religious causes were in reality only the surface for Highlander support for the Stuart cause, as always economics, a sense of autonomy coupled with what they saw as a defense against an encroachment on their way of life was the primary motivation. Opposition to the Act of Union 1707 which united Scotland and England into one nation under a common monarch and Parliament was viewed by some Highlander Clans, particularly in the northwest of Scotland as to the detriment of Scotland namely for economic reasons and due to certain laws barring Scottish nobility from serving in the House of Lords in London, opposition to the Union was also strong in Edinburgh, the modern capital of Scotland and seat of its own Parliament.

From their positions in France and later Rome, Italy the Catholic Stuarts with French funding often tried to stir rebellions to their cause back in Britain. From 1689-1745 a number of Jacobite Rebellions occurred with the goal of Stuart restoration being central to their goals. 1715 and the final one of 1745-46 were the most notable, particularly for their support among the Highlander Scots.

1715′s rebellion was a clash of Highlanders in some ways. Under John Erksine, 6th Earl of Mar Highlander clans were rallied to the Jacobite cause and army was assembled with took over the Highlands and spread on down to Stirling Castle in the heart of Scotland. They had declared James II’s son James Francis Edward Stuart the new King of Scots, he was also referred to as the “Old Pretender”. In opposition to him was the Hanoverian British government and its commander in Scotland, John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll. Campbell was a well known Highlander Clan with the Earls and Dukes of Argyll as its primary chieftain, the Campbells of Argyle had become very wealthy and politically well connected, perhaps the most well connected Highlander Clan in Scotland by the 18th century. Argyll led his force against Mar the Battle of Sheriffmuir in November of 1715. Both sides would claim victory but it was inconclusive, the Highlanders fought on both sides of the battle, largely depending on which clan one was a member. Ultimately, the Jacobites were beaten at the later Battle of Preston and the cause was frustrated in its goal once more.

1745 would see the most famous Jacobite Rebellion, it was an outgrowth of the concurrent War of the Austrian Succession. During the greater European wide War of the Austrian Succession, France and Prussia formed a coalition with Spain and other German and Italian states against Austria, Great Britain, the Electorate of Hanover and the Dutch Republic with other German supporters and limited Russian support. The new Jacobite leader was Charles Edward Stuart, known to the Jacobites as the “Young Pretender” after his father and to the Scots he was affectionately called “Bonnie Prince Charlie”. Charles was smuggled into Scotland to start an uprising when British military power there was weakest due to the bulk of Britain’s military being on the continent in war against the French coalition. Charles had hoped for French support to help knock Britain out of the war and raise him to the throne but bad weather prevented this from happening. Nevertheless, he gathered local support mostly from the Highlanders of northwestern Scotland.

He captured Edinburgh and was declared King and subsequently the Highlander Jacobites routed the Hanoverian British government forces in September 1745 at the Battle of Prestonpans, thanks to the Highland Charge. Further success was later had at Falkirk Muir in January 1746, once again the Highland Charge was instrumental to Jacobite success. However, by spring of 1746 the good fortunes of the Jacobite cause was fading. That winter they had marched into England toward London which caused a panic. They made it as far as Derby but realizing the French support they long hoped for never materialized and now facing a large, disciplined and experienced government army fresh from war on the continent, under the command of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland and son of King George II, the Jacobites returned to Scotland in high spirits but achieving no last strategic outcome. With Cumberland in pursuit the Jacobites retreated to the Highlands themselves, there they hoped to blend in and lead the government force on to ground of their own choosing where they could defeat them decisively.

Since 1689, government forces had been often been overrun by the Highland charge tactic in battle. Largely this was due to lack of discipline in government troops and the Highlanders fighting on topography of that catered to their advantage. The Duke of Cumberland was aware that these elements had lead to government defeat in the past, he was not apt to repeat the mistake of past commanders. The battle that finally took place in April 1746, known as the Battle of Culloden, fought near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands was not fought in the hilly or mountainous terrain that favored the Highlanders but instead on a boggy moor ground which slowed their advance in the face of modern weaponry (muskets and canister shot from cannons), the result was an hour long battle culminating in the last Highland Charge in history and the last major battle on British soil. It ended in bloody fashion for the Jacobites, Charles was thoroughly defeated, though he escaped Scotland back to the continent, disguised in drag. His Highlander force was butchered in the aftermath of the battle and so with Culloden died the Highland Charge tactic and effectively the Jacobite cause with which it had become so linked...

The Highland Charge tactic itself was essentially a infantry shock tactic. It required speed and relied on overwhelming force, it was psychological weapon as much as a physical weapon. Enhancement to its success was the charge being initiated downhill from the high ground head on into the enemy’s front or flank. The Scottish Highlands being rife with hilly and mountainous countryside, were a logistical nightmare for large armies used to fighting pitched battles, a lesson the Romans on down to the English had learned. In turn, they were the perfect place for a loose fighting formation like the Highlander Clans which operated as functionally a guerilla army against their opponents, they possessed local knowledge of the terrain and could blend in to hide from the enemy and then ambush and disappear seemingly at will. The tactic developed overtime from the original Scottish Highland tactic of fighting in tight formation. The Scots overwhelmed the enemy with their ferocity in battle, heavy weaponry and unsettling war cries. in battle they fought with battle axes or two-handed heavy swords called claymores. By the 17th century with weapons shifting to gunpowder based firearms and artillery, these tight formations were becoming vulnerable to ranged weapons which could cause many casualties at a distance. The Highlanders instead adapted the formation to one more reliant on terrain, looser and faster in format overall but still using the goal of traditional overwhelming force with unsettling war cries. The weapons and clothing were also adapted to better accommodate the charge. Instead of a claymore, the Highlanders carried a single handed broadsword which was large but lighter, they also carried a targe shield for defense and a smaller dirk thrusting dagger. Their clothing below the waist was reduced to a kilt.

The Highland charge was launched downhill on firm open ground at great speed in a wedge formation with loud war cries to raise the attacker’s morale as well as frighten a hopefully inexperienced and ill-disciplined enemy. The charge was meant to hit the enemy as high speed and break their lines with the “savagery” of their fighting, sometimes the mere sight and sound was enough unnerve and overrun the enemy. The Highland charge always anticipated a number of casualties due to a initial musket volley from the enemy, but the speed would be too much for them to reload in an era of single shot firearms. By the time the enemy was reloading they were struggling unnerved by the wails of the Highlanders and already being engaged with swords and dagger hacking and stabbing them to death. In many cases like at Killiecrankie, Prestonpans and Falkirk Muir the charge was successful due to the essential elements, speed, terrain and ill-disciplined enemies. Psychologically terrifying and well timed it proved to be a classic shock tactic. It shortcomings however were the danger of modern ranged weapons like artillery and muskets hitting the enemy at range, especially those fired by a professional disciplined army not inclined to turn and run at the sound and fury of the charge. Additionally, its implementation over broken ground or flat terrain or a combination of two in the face of modern weaponry like at Culloden could yield fatal consequences. The Highland charge has its roots and a resemblance in the ancient shock charge tactics of the Scots Celtic forbearers of Britain against Roman legions and other enemies. It embodied an ancestral connection and became a romantic image in and of itself, forever etched in the minds of historical memory when we think of the Scottish Highlands, kilted-tartan clad men running at full speed with sword, shield and dagger in hand, screaming like a banshee right into the enemy’s front, cutting down their opponent with fierce and wild abandon. The ultimate image of the barbarian fighting to preserve his way of life and freedom in the face of modernity. That’s the kind of image Killiecrankie and Culloden conjure, the image Walter Scott in the later Victorian era somewhat revived. The ultimate picture of Scottish romanticism on the battlefield...

#military history#scotland#romanticism#culloden#jacobites#highlands#1745#1715#1689#britain#celts#infantry tactics#shock tactic#highlander

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#art#sketch#Scribble#rkgk#oc#original character#original characters#transcendence#ordovice#digital art#procreate art#procreate#apple pencil#iPad art

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The geological timescale: Yanks VS Brits

The geological timescale is broken down into geochronologic segments, time periods based upon the continuity of rock strata and the relative time relationship between these strata. But what concerns us today is – where did the names of these time periods come from and who named more? Brits or Yanks?

I am a Brit and a strong believer that sulphur should be spelt with a ‘ph’ so the recent change of foetus to the American fetus has duly irked me. But it got me thinking; how many of the geological Eons, Eras and Periods have been named by Brits and how many by Americans? America beats us on size, population, wealth and any Olympic sport which doesn’t require sitting down but do they beat us on Geology? The Eons are all named after Greek words. We start with the Hadean (4.6 - 4Ga) named after Hades by American Preston Cloud. Britain 0 – 1 America.

This was followed by the Archean or Acheanozoic (Ancient or Ancient Life 4 – 2.5Ga), Proterozoic (Earlier Life 2500 - 541ma) and finally Phanaerozoic (Visible life 541ma – present day). Not one scientist has been accredited for naming these Eons so the score remains Britain 0 – 1 America.

The oldest verified period is also the last before the beginning of the Phanerozoic and start of the Cambrian explosion. The Ediacaran (645 - 542ma) was named after the Ediacara Hills in Australia and was first proposed to be a period by Martin Glaessner (Austro-Hungarian who escaped the persecution of the Jews by working for the soon to be BP). No points awarded

The Phanaerozoic Eon is split up into a number of Eras which follow a similar trend, Palaeozoic (Old life 541 – 252ma) (Brit John Phillips 1841), Mesozoic (252 – 66ma)(Brit John Phillips 1841) and finally Cenozoic (New Life 66ma – Present day). This leaves the score at Britain 2 – 1 America

The Eras in turn are split up into Periods and the names start to get a bit more interesting.

The Cambrian (542- 488.3ma) – Named in 1835 after the Latin name for Wales (Cambria) by a brit called Adam Sedgwick. Britain 3 –1 America

The Ordovician (488.3 – 443.7ma) – Named by Brit Charles Lapworth in 1879 after a tribe of Welsh Celts (the Ordovices) that inhabited Britain before the Romans. Britain 4 – 1 America.

The Silurian (443.7ma – 420ma) – Named by Scot (still a Brit) Roderick Murchison in 1835 after another tribe of Welsh Celts (the Silures, famous for Caratacus) that resisted Roman rule for 30 years. Britain 5 – 1 America.

The Devonian (420 – 359ma) – Named after a county in western England by William Buckland and Roderick Murchison (both Brits). Britain 6 – 1 America

The Carboniferous (359 – 299ma) – Named for the large coal bearing seams found associated with the time period. It is generally agreed that British geologists were the ones to name this period. Britain 7 – 1 America.

The Permian (299ma – 252ma) – Named in 1841 by the now Sir Roderick Murchinson after the ancient kingdom of Permia (a medieval state that existed in what is now Russia). Britain 8 – America 1.

The Triassic (252 – 201ma) – Named in 1834 by German Friedrich von Alberti after the 3 rock units that make up the period in Germany; the Bundsandstein, Muschelkalk and Keuper. Nil points awarded.

The Jurassic (201 – 145ma) – Named after the Jura Mountains by either (differing sources give different names) Alexandre Brongniart (French) or Leopold von Buch (German). Nil Points.

The Cretaceous (201 – 66ma) – Named after the Latin word for chalk ‘Creta’ and defined in 1822 by Jean d’Omalius d’Halloy (Belgian). Nil points.

The Paleogene (66 – 23ma) named after the Greek for ‘old born’ and The Neogene (23ma – 5ma) named after the Greek ‘new born’. Once again there is no record of a single person or body that named them. Nil points.

This takes us to a final score of Britain 8 - 1 America and concludes that, at least to begin with, geology was a very British passtime. Even if a lot of the names were pilfered from the greeks!

More importantly it gave me an opportunity to geek out over the geological column which I hope you enjoyed!

Watson

References: United States Geological Survey:http://www.geosociety.org/science/timescale/

British Geological Survey: http://www.bgs.ac.uk/discoveringGeology/time/timechart/home.html

International Commission on Stratigraphy: http://www.stratigraphy.org/

Further Reading: http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/help/timeform.php

Image Credit: USGS

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Geological Timescale: Yanks Vs Brits!

The geological timescale is broken down into geochronologic segments, time periods based upon the continuity of rock strata and the relative time relationship between these strata. But what concerns us today is – where did the names of these time periods come from and who named more? Brits or Yanks?

I am a Brit and a strong believer that sulphur should be spelt with a ‘ph’ so the recent change of foetus to the American fetus has duly irked me. But it got me thinking; how many of the geological Eons, Eras and Periods have been named by Brits and how many by Americans? America beats us on size, population, wealth and any Olympic sport which doesn’t require sitting down but do they beat us on Geology?

The Eons are all named after Greek words. We start with the Hadean (4.6 - 4Ga) named after Hades by American Preston Cloud. Britain 0 – 1 America.

This was followed by the Archean or Acheanozoic (Ancient or Ancient Life 4 – 2.5Ga), Proterozoic (Earlier Life 2500 - 541ma) and finally Phanaerozoic (Visible life 541ma – present day). Not one scientist has been accredited for naming these Eons so the score remains Britain 0 – 1 America.

The oldest verified period is also the last before the beginning of the Phanerozoic and start of the Cambrian explosion. The Ediacaran (645 - 542ma) was named after the Ediacara Hills in Australia and was first proposed to be a period by Martin Glaessner (Austro-Hungarian who escaped the persecution of the Jews by working for the soon to be BP). No points awarded

The Phanaerozoic Eon is split up into a number of Eras which follow a similar trend, Palaeozoic (Old life 541 – 252ma) (Brit John Phillips 1841), Mesozoic (252 – 66ma)(Brit John Phillips 1841) and finally Cenozoic (New Life 66ma – Present day). This leaves the score at Britain 2 – 1 America

The Eras in turn are split up into Periods and the names start to get a bit more interesting.

The Cambrian (542- 488.3ma) – Named in 1835 after the Latin name for Wales (Cambria) by a brit called Adam Sedgwick. Britain 3 –1 America

The Ordovician (488.3 – 443.7ma) – Named by Brit Charles Lapworth in 1879 after a tribe of Welsh Celts (the Ordovices) that inhabited Britain before the Romans. Britain 4 – 1 America.

The Silurian (443.7ma – 420ma) – Named by Scot (still a Brit) Roderick Murchison in 1835 after another tribe of Welsh Celts (the Silures, famous for Caratacus) that resisted Roman rule for 30 years. Britain 5 – 1 America.

The Devonian (420 – 359ma) – Named after a county in western England by William Buckland and Roderick Murchison (both Brits). Britain 6 – 1 America

The Carboniferous (359 – 299ma) – Named for the large coal bearing seams found associated with the time period. It is generally agreed that British geologists were the ones to name this period. Britain 7 – 1 America.

The Permian (299ma – 252ma) – Named in 1841 by the now Sir Roderick Murchinson after the ancient kingdom of Permia (a medieval state that existed in what is now Russia). Britain 8 – America 1.

The Triassic (252 – 201ma) – Named in 1834 by German Friedrich von Alberti after the 3 rock units that make up the period in Germany; the Bundsandstein, Muschelkalk and Keuper. Nil points awarded.

The Jurassic (201 – 145ma) – Named after the Jura Mountains by either (differing sources give different names) Alexandre Brongniart (French) or Leopold von Buch (German). Nil Points.

The Cretaceous (201 – 66ma) – Named after the Latin word for chalk ‘Creta’ and defined in 1822 by Jean d’Omalius d’Halloy (Belgian). Nil points.

The Paleogene (66 – 23ma) named after the Greek for ‘old born’ and The Neogene (23ma – 5ma) named after the Greek ‘new born’. Once again there is no record of a single person or body that named them. Nil points.

This takes us to a final score of Britain 8 - 1 America and concludes that, at least to begin with, geology was a very British passtime. Even if a lot of the names were pilfered from the greeks!

More importantly it gave me an opportunity to geek out over the geological column which I hope you enjoyed!

— The Earth Story

1 note

·

View note

Photo

‘Ordovices’ Poem

Written by The Silicon Tribesman, All Rights Reserved, 2018.

#poetry#poetrynow#spilledink#poetryriot#poetryslam#poets on tumblr#poets on poetry#poetsociety#poet#prehistoric#prehistory#ordovices#north wales#rhinogau#settlement#hillfort#creative#education#poems on tumblr#poems on nature#poems on the past#ritual#community#identity#belonging#standing stones#stone circle

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iron Age/Celtic Tribal Accounting Methods?

Does anyone know of any historical accounting methods among Iron Age (particularly Celtic) tribes? Doesn’t matter if it’s Gaulish, Iberian, Brythonic, Manx, etc. Other civilizations in Ancient China, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece for example had innovative methods of accounting or tracking trade goods, food stores, livestock, et cetera. Granted those civilizations evoke imagery of large developed cities with monumental buildings — a concept not quite as prevalent with Iron Age tribes like the Eblani or Ordovices.

In the case of Irish tribes I realized: they probably DIDN'T have a method of accounting. They would suddenly realize "hey, we don't have enough livestock to make it through winter; time for another cattle raid!" Hardly a working hypothesis, but that's all I can think of.

Ogham wasn’t developed until nearly the end of the Iron Age. Even then the known inscriptions are mostly boundary markers or bear names of those who carved it or who are memorialized by it. Using ogham as numerals didn’t even appear until a medieval monk wrote them in a manuscript. If there ever was a method of accounting, even in Ireland where the bogs preserve everything, I can’t find any evidence of accounting as a concept.

Hence the cattle raids.

4 notes

·

View notes