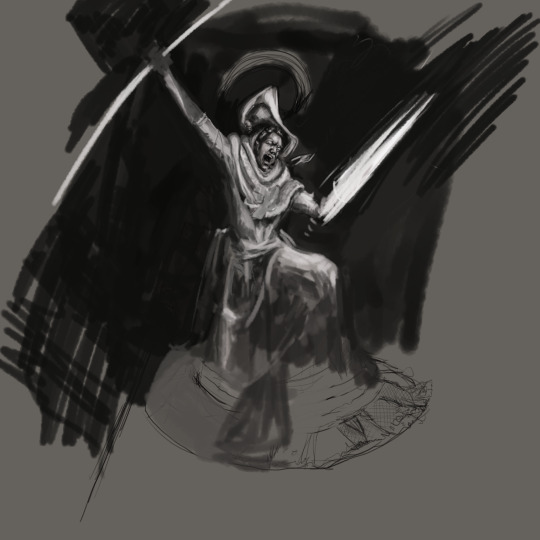

#Project 1837

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#art#digital art#fantasy art#character design#dark fantasy#historical fantasy#Project 1837#rpg#crpg#indie game#indie dev#concept art#dynamic pose#dramatic lighting#magic#heroism#original art#wip#drawing#illustration#game development#worldbuilding#storytelling#sacrifice#glowing weapons#intense emotion

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#art#digital art#indie game#concept art#character design#fantasy art#historical fantasy#dark fantasy#Project 1837#indie dev#indie game development#original art#rpg#crpg#magic#character sketch#wip#worldbuilding#storytelling#creative process#game development#game art#oc#fantasy character#drawing#illustration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let us remember Francis Trollope on the anniversary of her birth

Oil on canvas of Frances Trollope by Auguste Hervieu, c. 1832Born

Born Frances Milton on 10 March 1779 in Bristol, England

Died 6 October 1863 (aged 84) in Florence, Italy

Other names: Fanny Trollope

Occupation: Novelist

Notable work: Domestic Manners of the Americans

Spouse: Thomas Anthony Trollope (m. 1809; died 1835)

Children7; including Thomas, Anthony and Cecilia

Parent(s)William Milton Mary Gresley

Frances Milton Trollope, also known as Fanny Trollope (10 March 1779 – 6 October 1863), was an English novelist who wrote as Mrs. Trollope or Mrs. Frances Trollope. Her book, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), observations from a trip to the United States, is the best known.

She also wrote social novels: one against slavery is said to have influenced Harriet Beecher Stowe, and she also wrote the first industrial novel, and two anti-Catholic novels, which used a Protestant position to examine self-making.

Some recent scholars note that modernist critics have omitted women writers such as Frances Trollope.i n 1839, The New Monthly Magazine claimed, "No other author of the present day has been at once so read, so much admired, and so much abused".

Two of her sons, Thomas Adolphus and Anthony, became writers, as did her daughter-in-law Frances Eleanor Trollope (née Ternan), second wife of Thomas Adolphus Trollope.

Born at Stapleton, Bristol, Frances was the third daughter and middle child of the Reverend William Milton and Mary Milton (née Gresley). Frances was five years old when her mother died in childbirth.[4][5] Her father was remarried to Sarah Partington of Clifton in 1800.[6] She was baptised at St Michael's, Bristol, on 17 March 1779.[7] As a child, Frances read a great amount of English, French and Italian literature. She and her sister later moved to Bloomsbury, London, in 1803 to live with their brother, Henry Milton, who was employed in the War Office.[6]

Marriage and family

In London, she met Thomas Anthony Trollope, a barrister. At the age of 30, she married him on 23 May 1809 in Heckfield, Hampshire. They had four sons and three daughters:[8] Thomas Adolphus, Henry, Arthur (who died in 1824) Emily (who died in a day), Anthony, Cecilia and Emily. When the Trollopes moved to a leased farm at Harrow-on-the-Hill in 1817, they faced financial struggles for lack of agricultural expertise.[6] This was where Frances gave birth to her last two children.[5] Two of her sons and one daughter also became writers. Her eldest surviving son, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, wrote mostly histories: The Girlhood of Catherine de Medici, History of Florence, What I Remember, Life of Pius IX, and some novels. Her fourth son Anthony Trollope became a well-known and received novelist, establishing a strong reputation, especially for his serial novels, such as those set in the fictional county of Barsetshire, and his political series the Palliser novels. Cecilia Trollope Tilley published a novel in 1846.

Despite producing six living children, the Trollopes' marriage was reputedly unhappy.

Move to America

Soon after the move to the leased farm, her marital and financial strains led Frances to seek companionship and aid from Fanny Wright, ward of the French hero Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. In 1824 she visited La Grange, Lafayette's estate in France.[6] Over the next three years, she made several other visits to France and was inspired to take an American excursion with Wright. Frances thought of America as a simple economic venture and figured that she could save money by sending her children through Wright's communal school, as Wright had planned to reform the education of African American children and the formerly enslaved on their property in Tennessee.[9] In November 1827, Frances Trollope went with some of her family to Fanny Wright's utopian community Nashoba Commune in the United States. She took her son, Henry, and her two daughters, Charlotte and Emily. Her husband, Thomas Anthony, and remaining sons, Tom and Anthony, stayed at home and continued their education. In October 1828, Tom and his father joined Frances in Cincinnati, leaving Anthony at boarding school.[10] They returned to England in January 1829.

Arriving in the United States one year earlier than her husband, she developed an intimate relationship with Auguste Hervieu, a collaborator in her venture. (This is not verified.) After the community failed, Trollope moved to Cincinnati, Ohio with her family.[6] She also encouraged the sculptor Hiram Powers to do Dante Alighieri's Commedia in waxworks.

Nonetheless, all the ways she tried to support herself in America were unsuccessful. She found the cultural climate uninteresting and came to resent democracy. Furthermore, after her venture failed, her family was more in debt than when she had migrated there and they were forced to move back to England in 1831.

Return to Europe

From her return at the age of 50 until her death, Trollope's need of an income for her family and to escape her debts led her to begin writing novels, memoirs of her travels, and other shorter pieces, while travelling around Europe. She became well acquainted with elites and figures of Victorian literature including Elizabeth Barrett, Robert Browning, Charles Dickens, Joseph Henry Green and R. W. Thackeray (a relative of William Makepeace Thackeray).

She wrote more than 41 books: six travelogues, 35 novels, countless controversial articles, and poems. In 1843, Frances visited Italy and eventually moved to Florence permanently.

Trollope already gained notice with her first book Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832). She gave an unfavourable, and in the opinions of America's partisans, an exaggerated account. Her novel, The Refugee in America (1832), expressed similar views, prompting Catharine Sedgwick to respond that "Mrs. Trollope, though she has told some disagreeable truths, has for the most part caricatured till the resemblance is lost." She was thought to reflect the disparaging views of American society that were allegedly commonplace at that time among English people of the higher social classes.

Later Trollope wrote further travel works, such as Belgium and Western Germany in 1833 (1834), Paris and the Parisians in 1835 (1836), and Vienna and the Austrians (1838). Among those with whom she became acquainted in Brussels was the future novelist Anna Harriett Drury.

Novels

Next came The Abbess (1833), an anti-Catholic novel, as was Father Eustace (1847). While both borrowed from Victorian Gothic conventions, the scholar Susan Griffin notes that Trollope wrote a Protestant critique of Catholicism that also expressed "a gendered set of possibilities for self-making", which has been little recognised by scholars. She noted that "Modernism's lingering legacy in criticism meant overlooking a woman's nineteenth century studies of religious controversy."[14]

Trollope received more attention in her lifetime for what are considered several strong novels of social protest: Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw (1836) was the first anti-slavery novel, influencing the American Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). It focuses on two powerful families – one that strongly encourages slavery and another that strongly opposes it and provides sanctuary for slave refugees. It antagonizes pro-slavery characters, making them appear foolish and uncultured. Frances also brings out her idea of a stereotypical American by drawing certain characters as shrewd, convincing, sly and greedy.

Published in 1840, Michael Armstrong, the Factory Boy was the first industrial novel to be published in Britain, inspired by Frances's visit to Manchester in 1832, where she examined the conditions of children employed in the textile mills. The story of a factory boy who is rescued by a wealthy benefactor at first, but later returns to the mills, illustrates the misery of factory life and suggests that private philanthropy alone will not solve the widespread misery of factory employment. Other socially conscious novels of hers include The Vicar of Wrexhill (1837, Richard Bentley, London, 3 volumes), which took on the issue of corruption in the Church of England and evangelical circles. Possibly her greatest work is the Widow Barnaby trilogy (1839–1855), which includes the first ever sequel.[18] In particular, Michael Sadleir considers the skilful set-up of Petticoat Government [1850], with its cathedral city, clerical psychology and domineering female, as something of a formative influence on her son's elaborate and colourful cast of characters in Barchester Towers, notably Mrs. Proudie.[19]

In later years Frances Trollope continued to write novels and books on miscellaneous subjects – in all over 100 volumes. In her own time, she was considered to have acute powers of observation and a sharp and caustic wit, but her prolific production coupled with the rise of modernist criticism caused her works to be overlooked in the 20th century. Few of her books are now read, but her first and two others are available on Project Gutenberg.

After the death of her husband and daughter, in 1835 and 1838 respectively, Trollope moved to Florence, Italy, having lived, briefly, at Carleton, Eden in Cumbria, but finding that (in her son Tom's words) "the sun yoked his horses too far from Penrith town."[21] One year, she invited Theodosia Garrow to be her house guest. Garrow married her son Thomas Adolphus, and the three lived together until Trollope's death in 1863.She was buried near four other members of the Trollope household in the English Cemetery of Florence.

#Frances Trollope#women in literature#Women's history month#March 10#Anti catholic#Cecilia Trollope Tilley#Frances Eleanor Trollope#Books by women#Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832)#The Refugee in America (1832)#novelist Anna Harriett Drury#The Abbess (1833)#Father Eustace (1847).#Jonathan Jefferson Whitlaw (1836) was the first anti-slavery novel#Michael aarmstrong the Factory Boy(1840) was the first industrial novel#The Vicar of Wrexhill (1837) discuss religious corruption#Widow Barnaby trilogy (1839–1855) included the first sequel#Petticoat Government [1850]#project gutenberg

0 notes

Text

was thinking about this

To be in "public", you must be a consumer or a laborer.

About control of peoples' movement in space/place. Since the beginning.

"Vagrancy" of 1830s-onward Britain, people criminalized for being outside without being a laborer.

Breaking laws resulted in being sentenced to coerced debtor/convict labor. Coinciding with the 1830-ish climax of the Industrial Revolution and the land enclosure acts (factory labor, poverty, etc., increase), the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 establishes full-time police institution(s) in London. The "Workhouse Act" aka "Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834" forced poor people to work for a minimum number of hours every day. The Irish Constabulary of 1837 sets up a national policing force and the County Police Act of 1839 allows justices of the peace across England to establish policing institutions in their counties (New York City gets a police department in 1844). The major expansion of the "Vagrancy Act" of 1838 made "joblessness" a crime and enhanced its punishment. (Coincidentally, the law's date of royal assent was 27 July 1838, just 5 days before the British government was scheduled to allow fuller emancipation of its technical legal abolition of slavery in the British Caribbean on 1 August 1838.)

---

"Vagrancy" of 1860s-onward United States, people criminalized for being outside while Black.

Widespread emancipation after slavery abolition in 1865 rapidly followed by the outlawing of loitering which de facto outlawed existing as Black in public. Inability to afford fines results in being sentenced to forced labor by working on chain gangs or prisons farms, some built atop plantations.

---

"Vagrancy" of 1870s-onward across empires, people criminalized for being outside while being "foreign" and also being poor generally.

Especially from 1880-ish to 1918-ish, this was an age of widespread mass movement of peoples due to the land dispossession, poverty, and famine induced by global colonial extraction and "market expansion" (Scramble for Africa, US "American West", nation-building, conquering "frontiers"), as agricultural "revolutions" of imperial monoculture cash crop extraction resulted in ecological degradation, and as major imperial infrastructure building projects required a lot of vulnerable "mobile" labor. This coincides with and is facilitated by new railroad networks and telegraphs, leading to imperial implementation or expansion of identity documents, strict work contracts, passports, immigration surveillance, and border checkpoints.

All of this in just a few short years: In 1877, British administrators in India develop what would become the Henry Classification System of taking and keeping fingerprints for use in binding colonial Indians to legal contracts. That same year during the 1877 Great Railroad Strike, and in response to white anxiety about Black residents coming to the city during Great Migration, Chicago's policing institutions exponentially expand surveillance and pioneer "intelligence card" registers for tracking labor union organizing and Black movement, as Chicago's experiments become adopted by US military and expanded nationwide, later used by US forces monitoring dissent in colonial Philippines and Cuba. Japan based its 1880 Penal Code anti-vagrancy statutes on French models, and introduced "koseki" register to track poor/vagrant domestic citizens as Tokyo's Governor Matsuda segregates classes, and the nation introduces "modern police forces". In 1882, the United States passes the Chinese Exclusion Act. In 1884, the Ottoman government enacts major "Passport Nizamnamesi" legislation requiring passports. In 1885, the racist expulsion of the "Tacoma riot".

Punished for being Algerian in France. Punished for being Chinese in San Francisco. Punished for being Korean in Japan. Punished for crossing Ottoman borders without correct paperwork. Arrested for whatever, then sent to do convict labor. A poor person in the Punjab, starving during a catastrophic famine, might be coerced into a work contract by British authorities. They will have to travel, shipped off to build a railroad. But now they have to work. Now they are bound. They will be punished for being Punjabi and trying to walk away from Britain's tea plantations in Assam or Britain's rubber plantations in Malaya.

Mobility and confinement, the empire manipulates each.

---

"Vagrancy" amidst all of this, people also criminalized for being outside while "unsightly" and merely even superficially appearing to be poor. San Francisco introduced the notorious "ugly law" in 1867, making it illegal for "any person, who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or deformed in any way, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, to expose himself or herself to public view". Today, if you walk into a building looking a little "weird" (poor, Black, ill, disabled, etc.), you are given seething spiteful glares and asked to leave. De facto criminalized for simply going for a stroll without downloading the coffee shop's exclusive menu app.

Too ill, too poor, too exhausted, too indebted to move, you are trapped. Physical barriers (borders), legal barriers (identity documents), financial barriers (debt). "Vagrancy" everywhere in the United States, a combination of all of the above. "Vagrancy" since at least early nineteenth century Europe. About the control of movement through and access to space/place. Concretizing and weaponizing caste, corralling people, anchoring them in place, extracting their wealth and labor.

You are permitted to exist only as a paying customer or an employee.

#get to work or else you will be put to work#sorry#intimacies of four continents#tidalectics#abolition

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

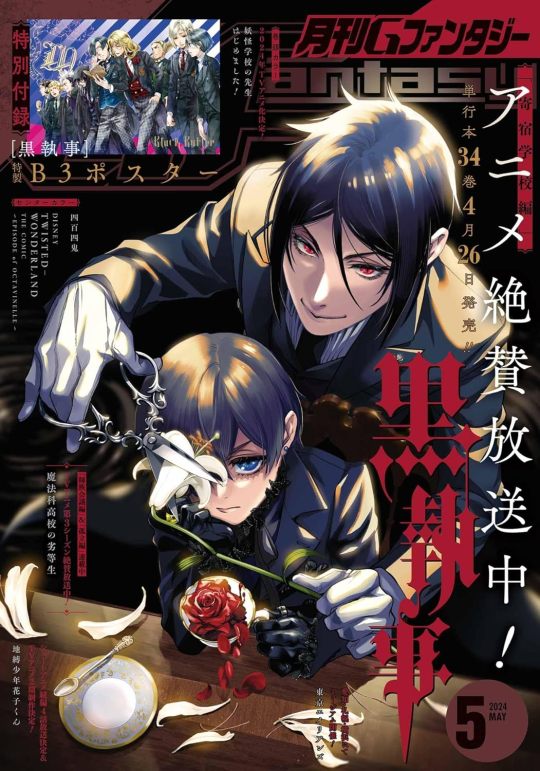

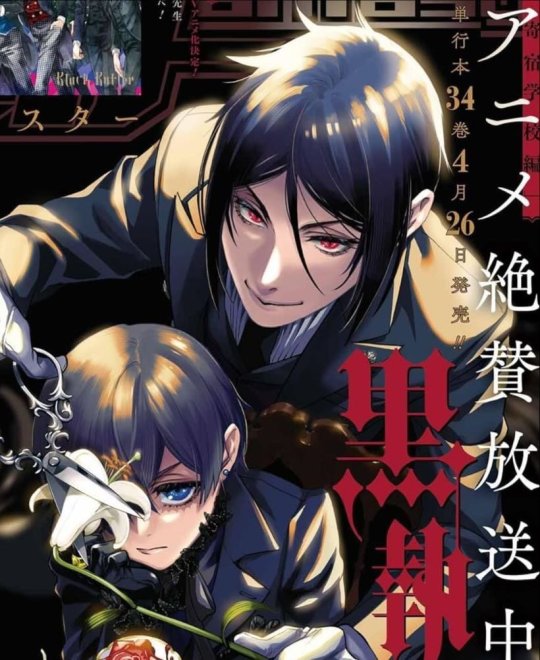

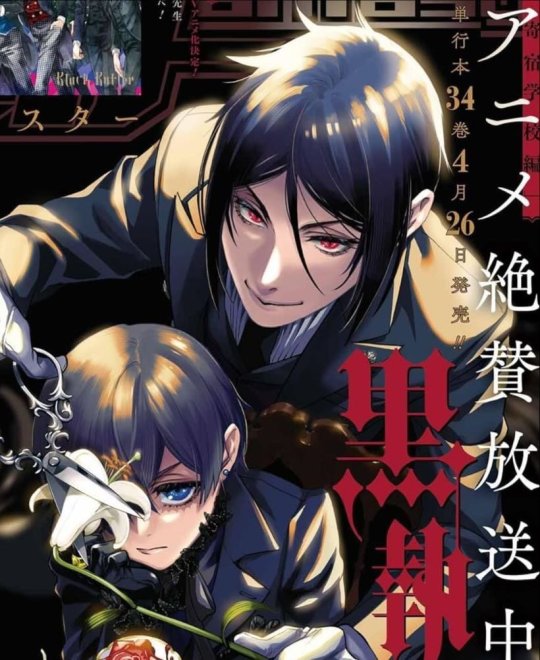

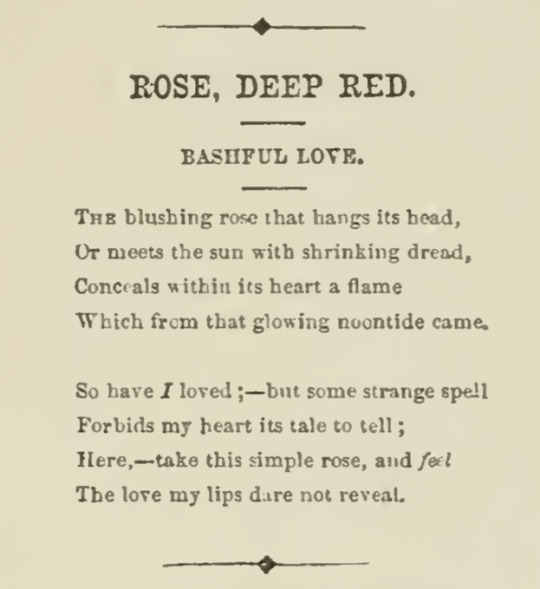

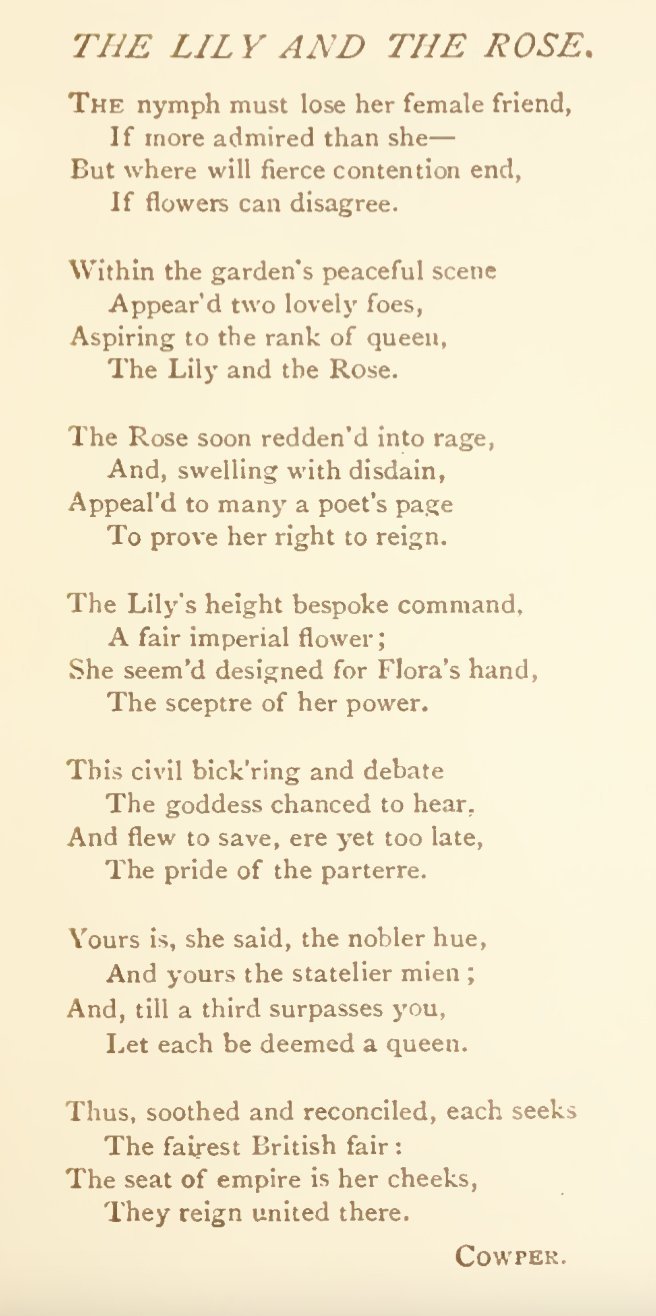

— A surprisingly long and in depth look about symbolism in the recent G-Fantasy cover by Yana Toboso ✦

Including references, flower language, how to decode the meaning of flowers, and a little too much brainrot. As well my personal interpretation drawn from all the sources I looked at. And of course what all of means (and maybe hints at?) for Sebastian and Ciel… and maybe even Sebaciel?

Originally posted as a twitter thread, but threads suck and I forgot a couple things. so here now.

Disclaimer :

I don’t know FOR SURE that all these things were directly referenced by Yana when creating this art. But being a fan of her work for over a decade I've become familiar with her use of symbolism and reference, and believe myself to have a good eye for it at this point! I'm also pretty familiar with the use of flower language, including different languages, due to having been involved in a project about it and having to read wayyy too much about this.

Some of it also includes my own personal interpretation, but the meanings and info I based myself off of ARE factual. I think I made it pretty clear when referencing my personal interpretation. You're welcome to reach your own interpretation based off of the stuff provided!

And lastly, I'm not a sebaciel shipper. I'm not an anti (the complete opposite, actually) and have nothing against the ship, I like the narrative around them and how they're written but I don’t actively ship them romantically or sexually. So I'd say this is actually a pretty unbiased interpretation. Personal taste is one thing, but I don’t deny the author's intention and whats written in front of me! That is what this post is about.

Kuroshitsuji takes place in the Victorian period (1837~1901) in 1889.

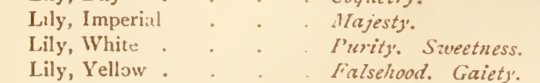

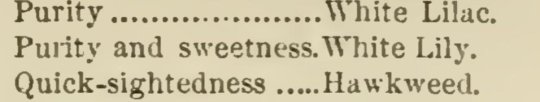

The following are both important Victorian books on the language of flowers that I will be basing myself off of.

Language of Flowers by Greenaway Kate (1884), and The Language of flowers: An Alphabet of Floral Emblems (1857).

(Also, I’m treating Ciel’s rose as a deep red rose. Which is a bit different than red roses. But I am adding some relevant information about roses in general, anyway.

Now, on what they say about these flowers.

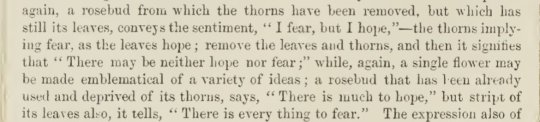

Deep rose, meaning "bashful shame". White lily, meaning "Purity and sweetness."

— The White Lily

Most people assume that the lily refers to Ciel's purity, and that’s a fair assumption. But I disagree.

Firstly, the one holding the lily is Sebastian. Holding it on his right hand, tilted towards the right. However what's relevant here is the VIEWER. From the viewer's POV he's holding it to the left. Note he also holds the scissors on his left hand, where he bears HIS contract seal.

How you hold a flower, what position you give it to someone in, changes the meaning of the flower. These context clues are very important. It tells us that 'purity and sweetness' doesn’t refer to Ciel, but actually refers to Sebastian (…sorta).

This may be a little confusing. Purity and sweetness, Sebastian?! I know, I know. bear with me.

These books provide poems to help us understand how you may interpret the intended meaning. The lily poem is about enduring trials out of love because of the purity and sweetness he sees in his lover's eyes and soul. I believe Yana directly references the poems I will include in this post in her new artwork.

— My Interpretation

the meaning of Sebastian's lily is:

"I do all out of love for the sweetness and purity within you."

Him holding it to the contact seal and cutting the flower could stand for him destroying this sentiment (affection within himself) that has arisen in him as a result of their contract by destroying the sweetness and purity—the source of it—within Ciel (consuming his soul).

Note: This is debatable, as 'reversed' almost always means upside down. But if you consider the lily facing away from the viewer as reversed then it could mean "impurity and bitterness" which fits pretty well with Ciel, and it being held against the contract seal which is a physical representation of his impurity, brought on by his bitterness.

— The Deep Red Rose

There something I find very interesting. The rose is in a teacup, standing in for tea (I think there's even tea alongside it in the cup.) From Yana herself we know that Sebastian's eyes are a reference to the reddish brown colour of tea.

Like I said, I believe this rose to be a deep red rose, which is a bit more specific than the meaning given to red roses. However I think the poem included for roses in general very much applies here.

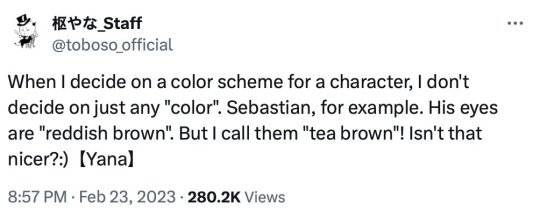

I was going to add my thoughts but I found this interpretation that sums it up pretty well if you replace the carpe diem theme with a more "running out of time" or "impending death" theme, which seems to be a more accurate reading for this artwork.

Looking at the rose itself, it has no thorns or leaves.

It is not a youthful rose as its already fully open and losing petals. "No hope, and no fear" fits with the poem, the rose is basically an hourglass referring to Ciel. His fate is unavoidable, but this isn't a deterrent. He's dancing on the ledge.

The deep red rose means 'bashful shame'.

When you compare it to the lily, which is a direct proclamation, the deep red rose is a quiet confession one cannot verbalize.

Debatable, to be fair but given the tie in to Sebastian's eye colour and the fact that he is always the one pouring tea for Ciel, I believe the Sebastian to be the speaker here too, but this time speaking on Ciel's feelings (Hence why he's the one holding it) rather than Sebastian's own.

— My Interpretation

The meaning of the deep red rose Ciel holds, speaking about Ciel's feelings of guardedness, and in response saying:

"Abandon your bashful shame, and let yourself be admired without expectations (hope) or fear"

Sebastian speaks about Ciel's feelings, the deep red rose acknowledges his feelings but they remain unspoken.

The Waller poem is a plead for his beloved to seize the day, for time is short, and allow herself to be loved completely.

Her beauty is one to be appreciated, she is not meant to be a rose unacknowledged (unloved) in the desert.

Regarding 'expectations', I think this is more about rigid ideas of how 'appreciation' or 'admiration, might be shown or received. Sebastian and Ciel's relationship defies normality or 'expectations'. So this, too, would defy expectations a young boy like Ciel, or a traumatised boy like Ciel, may have.

From Yana herself, we know Sebastian's dedication and how highly he holds 'beauty', specifically Ciel's beauty.

The author of the poem proclaims that beauty not appreciated is not beautiful indeeed, and so he calls his beloved to come to him and be appreciated wholly during the invaluable, limited time they have.

We see the deep red rose's petals fall away, in my opinion not only symbolising the withering away of time, but also the crumbling away of this "bashful shame" that Sebastian ascribes to Ciel.

How Sebastian wishes to "appreciate" this beauty is debatable. How he wants to "admire" and "desire" (per the poem) Ciel is rather open ended. Wether it be in a romantic way, a sexual way or by consuming his soul.

However, I don’t think these are mutually exclusive. And consuming Ciel can easily be a metaphor for the former two.

— The Lily and The Rose

The Greeneaway book has this poem which im sure was directly referenced. This poem speaks about the lily and the rose in a direct power struggle and fight for dominance, until they eventually unite and reign as one.

Now when speaking about this "union", you could say it refers to their contract, but I don’t think so.

The contract ties them to each other, but it doesn’t necessarily unite them. So I believe 'unity' to be about the appreciation Sebastian speaks of Ciel opening up to.

"The Lily" and "The Rose" might be interpreted as directly representing Sebastian and Ciel, and the unity that would come from them joining and becoming a truly complimentary pair. I think a power struggle and fight for being the one in control is very accurate way to describe their current dynamic in canon.

It may also be interpreted as "The Lily" and "The Rose" as being representations of their feelings and ideals previously. And then it would represent these two conflicting expressions—a loud unrelenting and destructive devotion, and a guarded, bashful, unspoken reluctance— coming together and turning from conflicting to complimentary.

Or as it tends to be with these things, both!

Either way all of this is expressed under the sense of impending doom created by their circumstances and the contract. So there's a sense of urgency permeating all of it.

Also clear to me is a sense of internal conflictedness coming from Sebastian's message that is usually only hinted at like this, and some people end up overlooking.

Sebastian desires Ciel deeply, but having him would also mean not being able to have him anymore.

Sebastian is torn and that’s why he attempts to cut the root of his wavering feelings represented by the lily.

All of this makes me wonder about what's next, and if we will see these things said more blatantly. Foreshadowing with flower language and references like this, isn't exactly rare for Yana. I wonder if we will see this 'unity' come to be, and what necessary development Sebastian and Ciel will need to undergo to make it possible. As well as what shape it will take.

I also wonder very much about Ciel's perspective in all of this, as this was almost entirely from Sebastian's POV, but I think that's intentional. Ciel has his own goals and a lot on his mind. Sebastian's goal IS Ciel. So I assume he spends a lot more time thinking about Ciel and this kind of thing.

Thank you if you read the whole way through. Like I said before, even though the sources defending it are, my interpretation is not law and you're welcome to reach your own with the things presented.

Links for sources, including free public domain PDFs of the books mentioned are found at the end of my twitter thread.

— Thanks for reading! —

#sebaciel shipper friendly post#kuroshitsuji#black butler#sebastian michaelis#ciel phantomhive#sebastian black butler#ciel black butler#sebaciel#please refrain from ship discourse on my post. I don't care if fictional characters upset you. I'm looking at the source material here.

350 notes

·

View notes

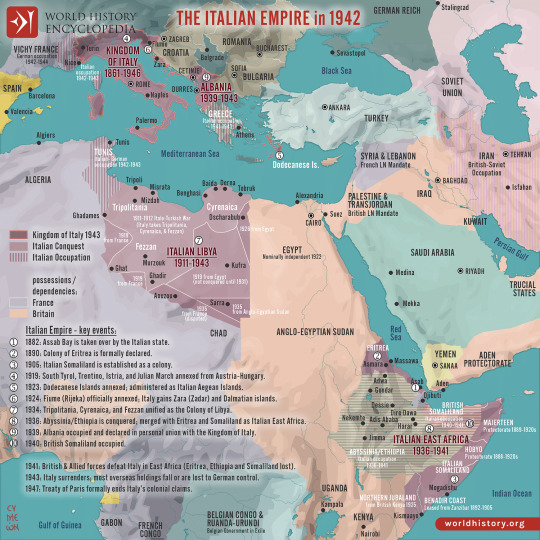

Photo

Italian Colonialism in Libya

One of the most coveted projects of Italian colonial policy was to secure an African colony in the Mediterranean. For this reason, Italy fought and won the Italo-Turkish war of 1911-1912 for the control of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. These two possessions in Northern Africa were later unified in 1934 to form the colony of Libya, which remained under Italian control until 1943.

Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were characterised by continuous clashes between the Italians and Libyan resistance movements. The conflict lasted until 1932, when a ‘pacification’ campaign conducted during Benito Mussolini's (1883-1945) fascist rule violently repressed the rebellion.

The Diplomatic Preparation For Invasion

One of the long-term aims of Italy’s colonial plans was an expansion on the other shore of the Mediterranean. Italian appetites were first directed towards Tunisia, but in 1881 France imposed a protectorate there, frustrating Italian ambitions. The French move was perceived as a humiliation, hence it was often referred to as ‘the slap of Tunis’, and it diminished the possibilities of finding a suitable alternative for an Italian outpost in North Africa. Attention was, therefore, shifted towards Tripolitania, selected because it was one of the few places free from the control of other European powers and because it could constitute a strategically useful naval base in the Mediterranean. Tripolitania corresponds to the northern and coastal part of modern-day Libya but was then a semi-autonomous province (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire (circa 1299 - 1922).

Ottoman suzerainty was more nominal than effective: between 1711 and 1835 the region was virtually independent under the rule of the local Karamanli dynasty. Even after the Ottomans had restored control in 1835, Tripolitania was under the influence of a political-religious fraternity called the Sanusiyya. This brotherhood was established in 1837 by Muhammad Ibn 'Ali Al-Senussi (1787-1859), an Algerian mystic who aimed to restore Islam to its early practice. Thanks to a successful integration within the Libyan tribal system, the Sanusiyya soon became an important centre of power, one that would later coordinate the resistance against the Italian invasion.

Returning to Italy, nationalistic press of the late-19th century emphasised the possibility of transforming Libya into a flourishing land for Italian emigrants, imagining the area as the future centre of trade across Africa. However, the Italian government was well aware that Libya had few natural resources - oil would only be discovered in 1955 - and a demographic colonisation would have been an arduous project. Moreover, at the time of the invasion, there were fewer than 1,000 Italians settled in Libya. Consequently, it was impossible to justify a war as a way to protect Italians abroad. As it was for Italian colonialism in Eritrea, the main justification was one of prestige and so Italy could sit at the table of the Great Power. The first military plans for an intervention in Libya came immediately after the ‘slap of Tunis’, then a tide of consequent events drove Italian action.

Nonetheless, it was fundamental to accompany the military preparation with diplomatic efforts to justify any Italian move on Libya. At the time, Italy was part of the Triple Alliance, together with the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the German Empire, who had been allies since 1879. This new military pact, another consequence of the ‘slap of Tunis’, was secured in 1882, and officially marked the end of a long period of friendship between the Kingdom of Italy and France. Even though the Italians received, in 1891, reassurances from their new allies regarding support for colonial claims, it was impossible to gain any progress in the Mediterranean without the consent of the true powers of the Mediterranean: France and Great Britain. Moreover, at the time Italy had to reassess its colonial policy after the defeat at Adwa in 1896 against the Ethiopian Empire, which blocked Italian expansionism in the Horn of Africa. The Mediterranean became, then, even more important for the Italian navy, due to the uncertainty of the situation in the Red Sea. France and Great Britain had already agreed on their respective areas of influence with the Anglo-French Convention of 1890. Therefore, Italy was forced to search for a rapprochement towards France and a series of diplomatic contacts culminated in the Italo-French agreement of 1901. This was followed by a similar Anglo-Italian agreement in 1902. This triangulation gave Italy a free hand in Tripolitania in exchange for Italian non-interference in any British interests in the Mediterranean and French claims in Morocco.

The international preparation was accompanied by a pervasive domestic policy. The topic of Libya was pushed by pro-colonialists and newspapers. The Banco di Roma, one of the main Italian banks, started to invest significantly in Tripolitania. To this must also be added the internal political calculations of the Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti (1842-1928). One of the most important political leaders, Giolitti's tenure witnessed economic expansion and progressive social reforms, such as the introduction of universal male suffrage in 1912. In addition, he was politically unscrupulous and his trasformismo was noted, that is, the political art to create (too) flexible coalitions of government. Giolitti was also frequently associated with episodes of corruption. The war in Libya was one way to strengthen his government by seeking the support of the nationalists and the liberal conservatives.

Another important factor was the Ottoman Empire. In 1876, Abdul Hamid II (1842-1918) became sultan, paving the way for decades of absolutist rule. There was a broad opposition movement to the sultan, called the Young Turks, that was advocating for a constitution. Their revolution against the sultan in 1908 led to a period of restored parliamentary rule in the empire, but also brought internal instability and international weakness. In 1908, Bulgaria declared its independence from Ottoman rule, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, sharpening the tensions in the Balkans which became one of the major causes of WWI (1914-18).

Read More

⇒ Italian Colonialism in Libya

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

January 26, 2025

Heather Cox Richardson

Jan 26, 2025

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln rose before the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, to make a speech. Just 28 years old, Lincoln had begun to practice law and had political ambitions. But he was worried that his generation might not preserve the republic that the founders had handed to it for transmission to yet another generation. He took as his topic for that January evening, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.”

Lincoln saw trouble coming, but not from a foreign power, as other countries feared. The destruction of the United States, he warned, could come only from within. “If destruction be our lot,” he said, “we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

The trouble Lincoln perceived stemmed from the growing lawlessness in the country as men ignored the rule of law and acted on their passions, imposing their will on their neighbors through violence. He pointed specifically to two recent events: the 1836 lynching of free Black man Francis McIntosh in St. Louis, Missouri, and the 1837 murder of white abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy by a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois.

But the problem of lawlessness was not limited to individual instances, he said. A public practice of ignoring the law eventually broke down all the guardrails designed to protect individuals, while lawbreakers, going unpunished, became convinced they were entitled to act without restraint. “Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane,” Lincoln said, “they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much as its total annihilation.”

The only way to guard against such destruction, Lincoln said, was to protect the rule of law on which the country was founded. “As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor…. Let reverence for the laws…become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.”

Lincoln was quick to clarify that he was not saying all laws were good. Indeed, he said, bad laws should be challenged and repealed. But the underlying structure of the rule of law, based in the Constitution, could not be abandoned without losing democracy.

Lincoln didn’t stop there. He warned that the very success of the American republic threatened its continuation. “[M]en of ambition and talents” could no longer make their name by building the nation—that glory had already been won. Their ambition could not be served simply by preserving what those before them had created, so they would achieve distinction through destruction.

For such a man, Lincoln said, “Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.” With no dangerous foreign power to turn people’s passions against, people would turn from the project of “establishing and maintaining civil and religious liberty” and would instead turn against each other.

Lincoln reminded his audience that the torch of American democracy had been passed to them. The Founders had used their passions to create a system of laws, but the time for passion had passed, lest it tear the nation apart. The next generation must support democracy through “sober reason,” he said. He called for Americans to exercise “general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws.”

“Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’”

What became known as the Lyceum Address is one of the earliest speeches of Lincoln’s to have been preserved, and at the time it established him as a rising politician and political thinker. But his recognition, in a time of religious fervor and moral crusades, that the law must prevail over individual passions reverberates far beyond the specific crises of the 1830s.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Abraham Lincoln#reason#Democracy#civil war#the US Constitution

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte would sign the decree for the construction of a temple in honor of the glory of the French army: “...it will be the most august and the most imposing of all...Reward with which the victor of kings and peoples "The founder of empires rewards his army."

A competition was called and the project of the architect Pierre-Alexandre Vignon was chosen for the construction of the Church of the Madeleine, Paris. Today considered one of the best examples of neoclassical architecture, its model was the Maison Carré (Roman era).

Neoclassicism disappears when you enter its interior, where the baroque surrounds the walls, only the coffered vaults remind us of the majestic Pantheon of Agrippa.

Its construction lasted eighty-five years due to political instability in France at the end of the 19th century 18th and early 19th. The political changes of the time caused its use to be modified several times. It was about to be a railway station. Between 1835 and 1837, Jules-Claude Ziegler painted “L'Histoire du christianisme” in the apse and between 1835 and 1857, the Paris-based Italian sculptor Marochetti carved the figure of Mary Magdalene for the altar.

One of the most important pieces of the church is the organ from 1846, the work of Aristide Gavillé-Coll.On the outside, the 52 Corinthian columns give it an imposing appearance and support the pediment, the work of the sculptor P. Lemaire, which represents The Last Judgment, which was made in 1833.

Fhoto ©️Buiron Christophe

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 26, 2025

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

JAN 27

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln rose before the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, to make a speech. Just 28 years old, Lincoln had begun to practice law and had political ambitions. But he was worried that his generation might not preserve the republic that the founders had handed to it for transmission to yet another generation. He took as his topic for that January evening, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.”

Lincoln saw trouble coming, but not from a foreign power, as other countries feared. The destruction of the United States, he warned, could come only from within. “If destruction be our lot,” he said, “we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

The trouble Lincoln perceived stemmed from the growing lawlessness in the country as men ignored the rule of law and acted on their passions, imposing their will on their neighbors through violence. He pointed specifically to two recent events: the 1836 lynching of free Black man Francis McIntosh in St. Louis, Missouri, and the 1837 murder of white abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy by a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois.

But the problem of lawlessness was not limited to individual instances, he said. A public practice of ignoring the law eventually broke down all the guardrails designed to protect individuals, while lawbreakers, going unpunished, became convinced they were entitled to act without restraint. “Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane,” Lincoln said, “they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much as its total annihilation.”

The only way to guard against such destruction, Lincoln said, was to protect the rule of law on which the country was founded. “As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor…. Let reverence for the laws…become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.”

Lincoln was quick to clarify that he was not saying all laws were good. Indeed, he said, bad laws should be challenged and repealed. But the underlying structure of the rule of law, based in the Constitution, could not be abandoned without losing democracy.

Lincoln didn’t stop there. He warned that the very success of the American republic threatened its continuation. “[M]en of ambition and talents” could no longer make their name by building the nation—that glory had already been won. Their ambition could not be served simply by preserving what those before them had created, so they would achieve distinction through destruction.

For such a man, Lincoln said, “Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.” With no dangerous foreign power to turn people’s passions against, people would turn from the project of “establishing and maintaining civil and religious liberty” and would instead turn against each other.

Lincoln reminded his audience that the torch of American democracy had been passed to them. The Founders had used their passions to create a system of laws, but the time for passion had passed, lest it tear the nation apart. The next generation must support democracy through “sober reason,” he said. He called for Americans to exercise “general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws.”

“Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’”

What became known as the Lyceum Address is one of the earliest speeches of Lincoln’s to have been preserved, and at the time it established him as a rising politician and political thinker. But his recognition, in a time of religious fervor and moral crusades, that the law must prevail over individual passions reverberates far beyond the specific crises of the 1830s.

—

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#art#digital art#indie game#indie dev#game design#fantasy art#character design#dark fantasy#historical fantasy#Project 1837#rpg#crpg#magic#pixel art inspiration#concept art#sketch#work in progress#indie devlog#creative process#worldbuilding#fantasy character#magic design#original character#oc#game dev#drawing#art sketch

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP Progress Check ☕️

Added: 1837 words

New total: 3948 words

So….. it’s been longer than I wanted it to be. Sorry about that 😩 I thought this was going to be the end of this chapter, but I feel like it’s too short so I’m merging it with the next chapter to beef it up a bit. So, pros, longer chapter and it’ll have a lil spice to it, which it otherwise wouldn’t have had. Cons, you’ll have to wait a bit longer.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

interesting things I read this week.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson

January 26, 2025

Heather Cox Richardson

Jan 27

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln rose before the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, to make a speech. Just 28 years old, Lincoln had begun to practice law and had political ambitions. But he was worried that his generation might not preserve the republic that the founders had handed to it for transmission to yet another generation. He took as his topic for that January evening, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.”

Lincoln saw trouble coming, but not from a foreign power, as other countries feared. The destruction of the United States, he warned, could come only from within. “If destruction be our lot,” he said, “we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

The trouble Lincoln perceived stemmed from the growing lawlessness in the country as men ignored the rule of law and acted on their passions, imposing their will on their neighbors through violence. He pointed specifically to two recent events: the 1836 lynching of free Black man Francis McIntosh in St. Louis, Missouri, and the 1837 murder of white abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy by a proslavery mob in Alton, Illinois.

But the problem of lawlessness was not limited to individual instances, he said. A public practice of ignoring the law eventually broke down all the guardrails designed to protect individuals, while lawbreakers, going unpunished, became convinced they were entitled to act without restraint. “Having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane,” Lincoln said, “they make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations; and pray for nothing so much as its total annihilation.”

The only way to guard against such destruction, Lincoln said, was to protect the rule of law on which the country was founded. “As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor…. Let reverence for the laws…become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.”

Lincoln was quick to clarify that he was not saying all laws were good. Indeed, he said, bad laws should be challenged and repealed. But the underlying structure of the rule of law, based in the Constitution, could not be abandoned without losing democracy.

Lincoln didn’t stop there. He warned that the very success of the American republic threatened its continuation. “[M]en of ambition and talents” could no longer make their name by building the nation—that glory had already been won. Their ambition could not be served simply by preserving what those before them had created, so they would achieve distinction through destruction.

For such a man, Lincoln said, “Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.” With no dangerous foreign power to turn people’s passions against, people would turn from the project of “establishing and maintaining civil and religious liberty” and would instead turn against each other.

Lincoln reminded his audience that the torch of American democracy had been passed to them. The Founders had used their passions to create a system of laws, but the time for passion had passed, lest it tear the nation apart. The next generation must support democracy through “sober reason,” he said. He called for Americans to exercise “general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws.”

“Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’”

What became known as the Lyceum Address is one of the earliest speeches of Lincoln’s to have been preserved, and at the time it established him as a rising politician and political thinker. But his recognition, in a time of religious fervor and moral crusades, that the law must prevail over individual passions reverberates far beyond the specific crises of the 1830s.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

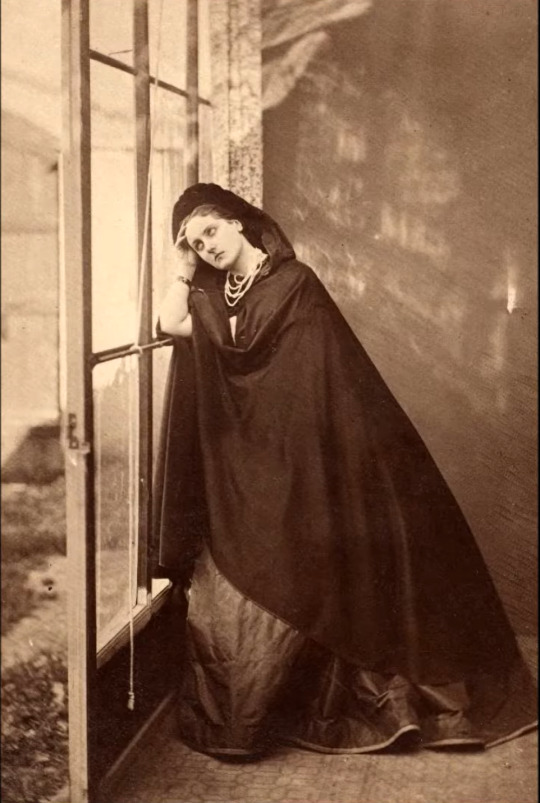

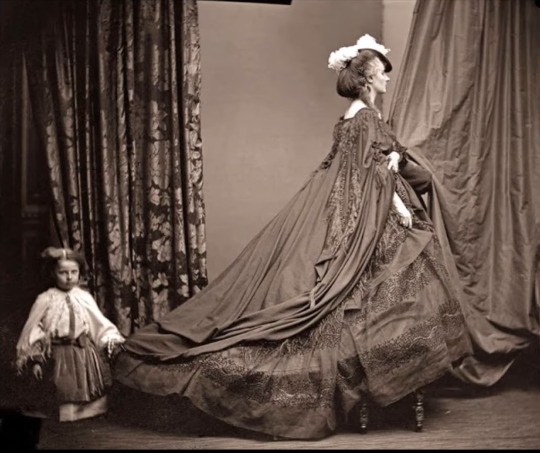

A Real-Life Barefoot Contessa

Well, what can I say. She's fabulous.

The Fabulous She I refer to above is the Contessa di Castiglione, who, were she living today, would be making millions on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and a gazillion other social media platforms. Being that she lived during the 19th century (1837-99), the Contessa had to settle for the reproductive mass media tool of her time—Photography. It was a medium with which she became familiar and whose function, beyond that of utility, she grasped profoundly. But not as a mere recorder of reality. No, for her it was an instrument of fantasy: Of role-play and the projection of a kind of imaginative truth—the truth of the Inner Self. That Being we see not in the mirror or in the eyes of others, but in our minds. The Self not known to mundane existence but as the most personal, intimate, and rarefied form of Art.

Over the course of some thirty-odd years, the Contessa had about 700 photographs taken of herself, in all sorts of costumes, in all sorts of poses, in all sorts of moods. She would wear her most extravagant gowns, she would stage herself in tableaux taken from history, theater, literature, and from her own life; she would present her bodily parts (mainly bare feet and legs) as brazenly fetishized objects; and she would frequently be seen gazing—at the camera, towards the distance, and at herself, reflected in hand mirrors and pier glasses. She fashioned herself as a self-image within another self-image, a self-referential, self-knowing portrait of who and what she was—a creator of herself as an Object of Art.

Our Contessa did have an interesting, pre-photography history. Born Virginia Oldoini Rapallini to minor Italian nobility, she was wedded, not of her choice, at age 17 to the some-12-years-older Count Castiglione, a union that produced one son and much unhappiness for an ill-matched pair. But when, at the urging of a diplomatic cousin, the Contessa arrived, in 1856, at the court of Emperor Napoleon III, to argue for the cause of Italian unification, she came into her own. Beautiful (extremely), witty, willful, and daring, the Contessa quickly slipped between the Emperor's sheets, while titillating the French aristocracy with her flamboyance, her outrageous fashions, and, even then, her complete self-absorption. You could call her the Kardashian of her time, except the Contessa was (and is) way too cool; no vulgar Kardash of today has one tittle of the Contessa's elegance, style, taste, and her utter sense of being—Fabulous.

Such Fabulousness, however, then as now, had a price. In a matter of months, the Contessa's affair with the emperor had fizzled, her husband had separated from her, and various scandals (mainly to do with her dramatic costuming, or presumed lack thereof) sent her packing from the Court. Within a few years, she had retired to a solitary anonymity in the Parisian suburbs. Although she continued to correspond with influential friends and lovers, she was soon forgotten by a world she had once dazzled.

But it was then she began her real vocation: To have herself—her life, career, legend, her imagined Being—inscribed in the most sophisticated recording medium of her era. With her reproduced images being sent to family, lovers, and friends, it was thus the myth of the Contessa was born—leaving to posterity, in nearly 700 photographic images, her tribute to the Self, a paean to Narcissism, as complete, obsessive, and solipsistic a voyage of Self-Creation as can be imagined. For which we can all be grateful.

Even when the lady had passed on, to that great photographic studio in the sky, recording media was still obsessed with the Contessa. The 20th century has taken advantage of her legend and allure to construct several films around her life, two of which I have seen. Both these films—La Contessa Castiglione of 1942, and The Contessa's Secret (also known as La Contessa di Castiglione) of 1954—follow her pre-photographic activities at the French court and her relationship with Napoleon III, while also touching on the cause of Italian unification (the putative reason for her Imperial seduction). Not that the Contessa lacks for other company; in each film a dashing young beau makes sure she's never at a loss during her down times. Another kind of Unification comes to the fore here.

I can't say how accurate either film is about history or biography, as each one (made in Europe) is dubbed in non-subtitled Italian, a language I don't know. I suspect, however, that for each History is merely an armature, a tailor's dummy (almost literally) to display the Contessa's stunning costumes, hair styles, jewelry, and fabled beauty. What the films lack in concrete Risorgiomento history is more than made up in their imaginative recreations of Risorgiomento fashions, style, and manners, an emphasis filtered, I sense, through a box-office consciousness of where audience interest will lie.

Such interest is foregrounded in the two actresses who portray the Contessa—Doris Duranti in 1942, Yvonne de Carlo in 1954. Both are amazingly beautiful women (which, no doubt, would have pleased the real Contessa), yet each one in her film is different in her look, performance, and image. They're almost reverse copies of each other: The slender Duranti is as pale as a Wili, with the delicacy of antique lace and the brittleness of an embroidery needle; whereas the fleshy de Carlo is dark, round, and energetic, an endearing touch of middle-classness in her style. The performances may not be the same, yet each one individually satisfies a fantasy of High Romance: If Duranti is a drooping lily, too frail and exquisite for everyday mucking-about, de Carlo is fiery, eager, sincere, an American-Canadian housewife's ideal of aristocratic passion, adventure, and glamour.

Is either portrayal anywhere like the real Contessa? I suspect not. Each performance arises from a 20th-century notion of Romance as portrayed in the Woman's Film genre—in which Life is a serial melodrama, a self-absorbed Theater of Emotion enacting scenes of Love, Passion, Despair, Renunciation, and Transcendence. Neither film touches on the Contessa's later career as a self-acting photographic model, yet curiously, each film does refer to Acting. In the 1942 film the Contessa is seen posing in what look like tableaux staged for the amusement of the French court; in the 1954 version she's seen attending elaborate theatrical performances. Artifice, as well as Art, is never far from the glittering boundaries of the Contessa's imaged self.

I'm guessing such scenes were inserted as commentary on the dramatic situations within each film. Yet, from another perspective, they can also be (foreshadowing) critiques of the Contessa's later photographic obsession, in which she depicted herself in scenes of what can be called a private Theater of the Mind: Portraying herself as gay, solemn, seductive, pensive, flirtatious, and, perhaps most alluringly—as detached; a distant object whose cool, blank gaze at the camera (and spectator) seduces us by its very remoteness. Gazing ourselves at these self-acted scenes, we might ask—how much of what we see is the actual Contessa, and how much is what we project onto her? Is the Contessa acting out self-fantasies for her own secret pleasure? Or is she 'acting,' as did Duranti and de Carlo, for a possible public, to view and witness her images, which become in turn embedded in our own fantasies of who this fabulous being is?

I've no doubt were she alive today, the Contessa would be making videos of herself on YouTube, home movies, as it were; creating, once again, a self-image for her admirers, aided by the marvelous additions of motion, color, and sound. What would they look like? What facets of this complex, complicated personality would be on view? Would they be bold, opinionated, spontaneous? Would she be commenting on current events, or indulging in gossip, or handing out beauty tips for self-improvement of the masses? Or would they be like her photos—silent, mysterious, teasing, contemplative, self-absorbed; indeed, self-enchanted with her changing, changeable, yet somehow always unchanging Self? We can only fantasize ourselves as to what they would be. As well as to what we would, within our own minds—see.

You can view more photographic images of the Contessa here. I've also written more on the Contessa di Castiglione, and the two films on her life, here at my Grand Old Movies blog. Because someone so Fabulous deserves to be written more about.

#Contessa di Castiglione#black and white photography#photography#19th century#Risorgiomento#Napoleon III#melodrama#woman's film#history#2nd Thoughts#self portrait#self love

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Thomson (1837-1921) | uitzicht op de rivier de Min (China) | 1873

Lees de vos van vandaag: 'Hoe het leven een project werd'

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deconstruct and Reconstruct Work in Progress I forgot to post

Tiffany & Co. Brand Deconstruction and Reconstruction

Company Overview: Tiffany & Co., founded in 1837, is a globally recognized luxury jewelry brand, celebrated for its exquisite craftsmanship and timeless designs. The company offers a wide range of products, including engagement rings, sterling silver pieces, watches, and specialty accessories. Known for its signature “Tiffany Blue” colour and iconic motifs like the heart-shaped key and "Return to Tiffany" tag, the brand has established itself as a symbol of elegance and sophistication.

Creative Strategy: For this project, I aimed to reinterpret the Tiffany & Co. logo using the style of mid-century graphic design, a period known for its bold use of typography, clean lines, and minimalist approach. I wanted to capture a sense of nostalgia while introducing a fresh, softer aesthetic. The reconstructed logo incorporates sketch-like elements and playful illustrations that evoke the classic feel of mid-century advertisements, blending them with Tiffany’s iconic symbols such as the heart key. The use of hand-drawn elements and a monochromatic palette creates a feminine and delicate appeal, aligning with the brand’s essence while making it feel more accessible and contemporary.

2 notes

·

View notes