#Social contract theory Locke

Text

"A Foundation of Modern Political Thought: A Review of John Locke's Second Treatise of Government"

John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" stands as a cornerstone of modern political philosophy, presenting a compelling argument for the principles of natural rights, social contract theory, and limited government. Written against the backdrop of political upheaval in 17th-century England, Locke's treatise remains as relevant and influential today as it was upon its publication.

At the heart of Locke's work lies the concept of natural rights, wherein he asserts that all individuals are born with inherent rights to life, liberty, and property. Locke argues that these rights are not granted by governments but are instead derived from the natural state of humanity. Through logical reasoning and appeals to natural law, Locke lays the groundwork for the assertion of individual rights as fundamental to the legitimacy of government.

Central to Locke's political theory is the notion of the social contract, wherein individuals voluntarily enter into a political community to secure their rights and promote their common interests. According to Locke, legitimate government arises from the consent of the governed, and its authority is derived from its ability to protect the rights of its citizens. This contract between rulers and the ruled establishes the basis for legitimate political authority and provides a framework for assessing the legitimacy of governmental actions.

Locke's treatise also advocates for the principle of limited government, arguing that the powers of government should be strictly defined and circumscribed to prevent tyranny and abuse of authority. He contends that governments exist to serve the interests of the people and should be subject to checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a few. Locke's advocacy for a separation of powers and the rule of law laid the groundwork for modern democratic governance and constitutionalism.

Moreover, Locke's emphasis on the right to revolution remains a contentious and influential aspect of his political philosophy. He argues that when governments fail to fulfill their obligations to protect the rights of citizens, individuals have the right to resist and overthrow oppressive regimes. This revolutionary doctrine has inspired movements for political reform and self-determination throughout history, serving as a rallying cry for those seeking to challenge unjust authority.

In conclusion, John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" is a seminal work that continues to shape the discourse on political theory and governance. Through his eloquent prose and rigorous argumentation, Locke presents a compelling vision of a just and legitimate political order grounded in the principles of natural rights, social contract, and limited government. His ideas have left an indelible mark on the development of liberal democracy and remain essential reading for anyone interested in understanding the foundations of modern political thought.

John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" is available in Amazon in paperback 12.99$ and hardcover 19.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 181

Language: English

Rating: 9/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Second Treatise of Government#John Locke political theory#Natural rights philosophy#Social contract theory Locke#Limited government principles#Individual liberty Locke#Government legitimacy theory#Consent of the governed#Locke's political philosophy#Locke's theory of government#Locke's political ideas#Locke's philosophy of freedom#Locke's view on governance#Locke's theory of sovereignty#Locke's concept of property rights#Locke's influence on democracy#Enlightenment political thought#Liberal democracy Locke#Civil liberties in Locke's theory#Separation of powers Locke#Rule of law Locke#Right to revolution theory#Constitutionalism Locke#Political reform ideas#Tyranny resistance Locke#Locke's concept of equality#Locke's principles of justice#Government accountability Locke#Freedom of expression Locke#Civic duty in Locke's theory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A Foundation of Modern Political Thought: A Review of John Locke's Second Treatise of Government"

John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" stands as a cornerstone of modern political philosophy, presenting a compelling argument for the principles of natural rights, social contract theory, and limited government. Written against the backdrop of political upheaval in 17th-century England, Locke's treatise remains as relevant and influential today as it was upon its publication.

At the heart of Locke's work lies the concept of natural rights, wherein he asserts that all individuals are born with inherent rights to life, liberty, and property. Locke argues that these rights are not granted by governments but are instead derived from the natural state of humanity. Through logical reasoning and appeals to natural law, Locke lays the groundwork for the assertion of individual rights as fundamental to the legitimacy of government.

Central to Locke's political theory is the notion of the social contract, wherein individuals voluntarily enter into a political community to secure their rights and promote their common interests. According to Locke, legitimate government arises from the consent of the governed, and its authority is derived from its ability to protect the rights of its citizens. This contract between rulers and the ruled establishes the basis for legitimate political authority and provides a framework for assessing the legitimacy of governmental actions.

Locke's treatise also advocates for the principle of limited government, arguing that the powers of government should be strictly defined and circumscribed to prevent tyranny and abuse of authority. He contends that governments exist to serve the interests of the people and should be subject to checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a few. Locke's advocacy for a separation of powers and the rule of law laid the groundwork for modern democratic governance and constitutionalism.

Moreover, Locke's emphasis on the right to revolution remains a contentious and influential aspect of his political philosophy. He argues that when governments fail to fulfill their obligations to protect the rights of citizens, individuals have the right to resist and overthrow oppressive regimes. This revolutionary doctrine has inspired movements for political reform and self-determination throughout history, serving as a rallying cry for those seeking to challenge unjust authority.

In conclusion, John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" is a seminal work that continues to shape the discourse on political theory and governance. Through his eloquent prose and rigorous argumentation, Locke presents a compelling vision of a just and legitimate political order grounded in the principles of natural rights, social contract, and limited government. His ideas have left an indelible mark on the development of liberal democracy and remain essential reading for anyone interested in understanding the foundations of modern political thought.

John Locke's "Second Treatise of Government" is available in Amazon in paperback 12.99$ and hardcover 19.99$ editions.

Number of pages: 181

Language: English

Rating: 9/10

Link of the book!

Review By: King's Cat

#Second Treatise of Government#John Locke political theory#Natural rights philosophy#Social contract theory Locke#Limited government principles#Individual liberty Locke#Government legitimacy theory#Consent of the governed#Locke's political philosophy#Locke's theory of government#Locke's political ideas#Locke's philosophy of freedom#Locke's view on governance#Locke's theory of sovereignty#Locke's concept of property rights#Locke's influence on democracy#Enlightenment political thought#Liberal democracy Locke#Civil liberties in Locke's theory#Separation of powers Locke#Rule of law Locke#Right to revolution theory#Constitutionalism Locke#Political reform ideas#Tyranny resistance Locke#Locke's concept of equality#Locke's principles of justice#Government accountability Locke#Freedom of expression Locke#Civic duty in Locke's theory

0 notes

Text

The Implicit Contract in Social Contract Theory

Social contract theory is a foundational concept in political philosophy that explores the origin and legitimacy of political authority and the rights and duties of individuals within a society. At the heart of social contract theory is the idea of an implicit contract between individuals and the state. This implicit contract outlines the mutual obligations and expectations that form the basis of a stable and just society.

Key Elements of the Social Contract

State of Nature:

Social contract theorists often begin with a hypothetical "state of nature," a pre-political condition where individuals exist without an established government or social order. The state of nature is used to illustrate the problems and challenges that lead individuals to form a social contract.

Mutual Agreement:

The social contract is an agreement among individuals to create and recognize a governing authority. This agreement is often seen as implicit, meaning it is not an actual historical event but a theoretical construct that explains the origin of political society.

Surrender of Certain Freedoms:

Individuals agree to surrender some of their natural freedoms and submit to the authority of the state in exchange for protection and the benefits of organized society. This surrender is necessary to achieve security, order, and the enforcement of laws.

Protection of Rights:

In return for their submission, individuals expect the state to protect their remaining rights, such as the rights to life, liberty, and property. The state’s primary role is to ensure the safety and well-being of its citizens.

Legitimacy of Authority:

The legitimacy of political authority is derived from the consent of the governed. The state's power is justified because it is based on the collective agreement of individuals to form a government that serves their interests.

Major Theorists and Their Views

Thomas Hobbes:

In his work "Leviathan," Hobbes describes the state of nature as a condition of perpetual conflict and insecurity, where life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." To escape this, individuals collectively agree to create a powerful sovereign authority to enforce peace and prevent chaos. The social contract, in Hobbes' view, involves individuals giving up all their rights to the sovereign in exchange for security.

John Locke:

Locke's version of the social contract, as outlined in "Two Treatises of Government," presents a more optimistic view of the state of nature, where individuals possess natural rights to life, liberty, and property. Locke argues that individuals consent to form a government primarily to protect these rights. If the government fails to protect these rights or becomes tyrannical, individuals have the right to revolt and establish a new government.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau:

In "The Social Contract," Rousseau argues that the state of nature was a peaceful and harmonious condition but became corrupt with the advent of private property. Rousseau's social contract aims to restore freedom and equality by creating a collective "general will" that represents the common interests of all individuals. The government’s role is to implement the general will, and individuals must adhere to it for the common good.

Implications of the Social Contract

Rights and Duties:

The social contract establishes the rights and duties of both individuals and the state. Individuals are expected to obey the laws and contribute to the common good, while the state is obligated to protect the rights and interests of its citizens.

Political Obligation:

The concept of political obligation arises from the social contract. Individuals have a moral and legal duty to obey the laws and support the government because they have consented to its authority.

Legitimacy and Justice:

The legitimacy of a government is based on its adherence to the terms of the social contract. A just government is one that respects and protects the rights of individuals, fulfills its obligations, and operates with the consent of the governed.

Revolution and Reform:

If a government fails to uphold its end of the social contract, individuals have the right to seek reform or, in extreme cases, to overthrow the government. This principle underpins many democratic movements and revolutions throughout history.

The implicit contract between individuals and the state in social contract theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the foundations of political authority and the relationship between citizens and their government. By exploring the mutual obligations and expectations that form the basis of this contract, social contract theory offers insights into the principles of justice, legitimacy, and the rights and duties that sustain a stable and just society.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#politics#Social Contract Theory#Political Philosophy#Thomas Hobbes#John Locke#Jean-Jacques Rousseau#State of Nature#Political Authority#Consent of the Governed#Rights and Duties#Political Obligation

0 notes

Text

America's largest hospital chain has an algorithmic death panel

It’s not that conservatives aren’t sometimes right — it’s that even when they’re right, they’re highly selective about it. Take the hoary chestnut that “incentives matter,” trotted out to deny humane benefits to poor people on the grounds that “free money” makes people “workshy.”

There’s a whole body of conservative economic orthodoxy, Public Choice Theory, that concerns itself with the motives of callow, easily corrupted regulators, legislators and civil servants, and how they might be tempted to distort markets.

But the same people who obsess over our fallible public institutions are convinced that private institutions will never yield to temptation, because the fear of competition keeps temptation at bay. It’s this belief that leads the right to embrace monopolies as “efficient”: “A company’s dominance is evidence of its quality. Customers flock to it, and competitors fail to lure them away, therefore monopolies are the public’s best friend.”

But this only makes sense if you don’t understand how monopolies can prevent competitors. Think of Uber, lighting $31b of its investors’ cash on fire, losing 41 cents on every dollar it brought in, in a bid to drive out competitors and make public transit seem like a bad investment.

Or think of Big Tech, locking up whole swathes of your life inside their silos, so that changing mobile OSes means abandoning your iMessage contacts; or changing social media platforms means abandoning your friends, or blocking Google surveillance means losing your email address, or breaking up with Amazon means losing all your ebooks and audiobooks:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

Businesspeople understand the risks of competition, which is why they seek to extinguish it. The harder it is for your customers to leave — because of a lack of competitors or because of lock-in — the worse you can treat them without risking their departure. This is the core of enshittification: a company that is neither disciplined by competition nor regulation can abuse its customers and suppliers over long timescales without losing either:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

It’s not that public institutions can’t betray they public interest. It’s just that public institutions can be made democratically accountable, rather than financially accountable. When a company betrays you, you can only punish it by “voting with your wallet.” In that system, the people with the fattest wallets get the most votes.

When public institutions fail you, you can vote with your ballot. Admittedly, that doesn’t always work, but one of the major predictors of whether it will work is how big and concentrated the private sector is. Regulatory capture isn’t automatic: it’s what you get when companies are bigger than governments.

If you want small governments, in other words, you need small companies. Even if you think the only role for the state is in enforcing contracts, the state needs to be more powerful than the companies issuing those contracts. The bigger the companies are, the bigger the government has to be:

https://doctorow.medium.com/regulatory-capture-59b2013e2526

Companies can suborn the government to help them abuse the public, but whether public institutions can resist them is more a matter of how powerful those companies are than how fallible a public servant is. Our plutocratic, monopolized, unequal society is the worst of both worlds. Because companies are so big, they abuse us with impunity — and they are able to suborn the state to help them do it:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/testing-theories-of-american-politics-elites-interest-groups-and-average-citizens/62327F513959D0A304D4893B382B992B

This is the dimension that’s so often missing from the discussion of why Americans pay more for healthcare to get worse outcomes from health-care workers who labor under worse conditions than their cousins abroad. Yes, the government can abet this, as when it lets privatizers into the Medicare system to loot it and maim its patients:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-01-patient-zero-tom-scully/

But the answer to this isn’t more privatization. Remember Sarah Palin’s scare-stories about how government health care would have “death panels” where unaccountable officials decided whether your life was worth saving?

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26195604/

The reason “death panels” resounded so thoroughly — and stuck around through the years — is that we all understand, at some deep level, that health care will always be rationed. When you show up at the Emergency Room, they have to triage you. Even if you’re in unbearable agony, you might have to wait, and wait, and wait, because other people (even people who arrive after you do) have it worse.

In America, health care is mostly rationed based on your ability to pay. Emergency room triage is one of the only truly meritocratic institutions in the American health system, where your treatment is based on urgency, not cash. Of course, you can buy your way out of that too, with concierge doctors. And the ER system itself has been infested with Private Equity parasites:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/17/the-doctor-will-fleece-you-now/#pe-in-full-effect

Wealth-based health-care rationing is bad enough, but when it’s combined with the public purse, a bad system becomes a nightmare. Take hospice care: private equity funds have rolled up huge numbers of hospices across the USA and turned them into rigged — and lethal — games:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/26/death-panels/#what-the-heck-is-going-on-with-CMS

Medicare will pay a hospice $203-$1,462 to care for a dying person, amounting to $22.4b/year in public funds transfered to the private sector. Incentives matter: the less a hospice does for their patients, the more profits they reap. And the private hospice system is administered with the lightest of touches: at the $203/day level, a private hospice has no mandatory duties to their patients.

You can set up a California hospice for the price of a $3,000 filing fee (which is mostly optional, since it’s never checked). You will have a facility inspection, but don’t worry, there’s no followup to make sure you remediate any failing elements. And no one at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services tracks complaints.

So PE-owned hospices pressure largely healthy people to go into “hospice care” — from home. Then they do nothing for them, including continuing whatever medical care they were depending on. After the patient generates $32,000 in billings for the PE company, they hit the cap and are “live discharged” and must go through a bureaucratic nightmare to re-establish their Medicare eligibility, because once you go into hospice, Medicare assumes you are dying and halts your care.

PE-owned hospices bribe doctors to refer patients to them. Sometimes, these sham hospices deliberately induce overdoses in their patients in a bid to make it look like they’re actually in the business of caring for the dying. Incentives matter:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/12/05/how-hospice-became-a-for-profit-hustle

Now, hospice care — and its relative, palliative care — is a crucial part of any humane medical system. In his essential book, Being Mortal, Atul Gawande describes how end-of-life care that centers a dying person’s priorities can make death a dignified and even satisfying process for the patient and their loved ones:

https://atulgawande.com/book/being-mortal/

But that dignity comes from a patient-centered approach, not a profit-centered one. Doctors are required to put their patients’ interests first, and while they sometimes fail at this (everyone is fallible), the professionalization of medicine, through which doctors were held to ethical standards ahead of monetary considerations, proved remarkable durable.

Partly that was because doctors generally worked for themselves — or for other doctors. In most states, it is illegal for medical practices to be owned by non-MDs, and historically, only a small fraction of doctors worked for hospitals, subject to administration by businesspeople rather than medical professionals.

But that was radically altered by the entry of private equity into the medical system, with the attending waves of consolidation that saw local hospitals merged into massive national chains, and private practices scooped up and turned into profit-maximizers, not health-maximizers:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-02-qa-corporate-medicine-destroys-doctors/

Today, doctors are being proletarianized, joining the ranks of nurses, physicians’ assistants and other health workers. In 2012, 60% of practices were doctor-owned and only 5.6% of docs worked for hospitals. Today, that’s up by 1,000%, with 52.1% of docs working for hospitals, mostly giant corporate chains:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-04-when-mds-go-union/

The paperclip-maximizing, grandparent-devouring transhuman colony organism that calls itself a Private Equity fund is endlessly inventive in finding ways to increase its profits by harming the rest of us. It’s not just hospices — it’s also palliative care.

Writing for NBC News, Gretchen Morgenson describes how HCA Healthcare — the nation’s largest hospital chain — outsourced its death panels to IBM Watson, whose algorithmic determinations override MDs’ judgment to send patients to palliative care, withdrawing their care and leaving them to die:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/doctors-say-hca-hospitals-push-patients-hospice-care-rcna81599

Incentives matter. When HCA hospitals send patients to die somewhere else to die, it jukes their stats, reducing the average length of stay for patients, a key metric used by HCA that has the twin benefits of making the hospital seem like a place where people get well quickly, while freeing up beds for more profitable patients.

Goodhart’s Law holds that “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Give an MBA within HCA a metric (“get patients out of bed quicker”) and they will find a way to hit that metric (“send patients off to die somewhere else, even if their doctors think they could recover”):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goodhart%27s_law

Incentives matter! Any corporate measure immediately becomes a target. Tell Warners to decrease costs, and they will turn around and declare the writers’ strike to be a $100m “cost savings,” despite the fact that this “savings” comes from ceasing production on the shows that will bring in all of next year’s revenue:

https://deadline.com/2023/08/warner-bros-discovery-david-zaslav-gunnar-wiedenfels-strikes-1235453950/

Incentivize a company to eat its seed-corn and it will chow down.

Only one of HCA’s doctors was willing to go on record about its death panels: Ghasan Tabel of Riverside Community Hospital (motto: “Above all else, we are committed to the care and improvement of human life”). Tabel sued Riverside after the hospital retaliated against him when he refused to follow the algorithm’s orders to send his patients for palliative care.

Tabel is the only doc on record willing to discuss this, but 26 other doctors talked to Morgenson on background about the practice, asking for anonymity out of fear of retaliation from the nation’s largest hospital chain, a “Wall Street darling” with $5.6b in earnings in 2022.

HCA already has a reputation as a slaughterhouse that puts profits before patients, with “severe understaffing”:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/workers-us-hospital-giant-hca-say-puts-profits-patient-care-rcna64122

and rotting, undermaintained facililties:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/roaches-operating-room-hca-hospital-florida-rcna69563

But while cutting staff and leaving hospitals to crumble are inarguable malpractice, the palliative care scam is harder to pin down. By using “AI” to decide when patients are beyond help, HCA can employ empiricism-washing, declaring the matter to be the factual — and unquestionable — conclusion of a mathematical process, not mere profit-seeking:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/26/dictators-dilemma/ggarbage-in-garbage-out-garbage-back-in

But this empirical facewash evaporates when confronted with whistleblower accounts of hospital administrators who have no medical credentials berating doctors for a “missed hospice opportunity” when a physician opts to keep a patient under their care despite the algorithm’s determination.

This is the true “AI Safety” risk. It’s not that a chatbot will become sentient and take over the world — it’s that the original artificial lifeform, the limited liability company, will use “AI” to accelerate its murderous shell-game until we can’t spot the trick:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/10/in-the-dumps-2/

The risk is real. A 2020 study in the Journal of Healthcare Management concluded that the cash incentives for shipping patients to palliatve care “may induce deceiving changes in mortality reporting in several high-volume hospital diagnoses”:

https://journals.lww.com/jhmonline/Fulltext/2020/04000/The_Association_of_Increasing_Hospice_Use_With.7.aspx

Incentives matter. In a private market, it’s always more profitable to deny care than to provide it, and any metric we bolt onto that system to prevent cheating will immediately become a target. For-profit healthcare is an oxymoron, a prelude to death panels that will kill you for a nickel.

Morgenson is an incisive commentator on for-profit looting. Her recent book These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs — and Wrecks — America (co-written with Joshua Rosner) is a must-read:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/02/plunderers/#farben

I’m kickstarting the audiobook for “The Internet Con: How To Seize the Means of Computation,” a Big Tech disassembly manual to disenshittify the web and bring back the old, good internet. It’s a DRM-free book, which means Audible won’t carry it, so this crowdfunder is essential. Back now to get the audio, Verso hardcover and ebook:

http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/05/any-metric-becomes-a-target/#hca

[Image ID: An industrial meat-grinder. A sick man, propped up with pillows, is being carried up its conveyor towards its hopper. Ground meat comes out of the other end. It bears the logo of HCA healthcare. A pool of blood spreads out below it.]

Image:

Seydelmann (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GW300_1.jpg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#hca healthcare#Gretchen Morgenson incentives matter#death panels#medicare for all#ibm watson#the algorithm#algorithmic harms#palliative care#hospice#hospice care#business#incentives matter#any metric becomes a target#goodhart's law

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the level of political theory, it is my contention that so long as "liberty" claims remain central to the political agenda of western liberalism, feminists and civil libertarians will remain locked in conflict. This contention has two aspects. First, I contend that not only do women presently have less "liberty" than do men in the liberal state, but that men have never been able to imagine "liberty" without assuming the oppression of women. If there were no women (socially or sexually), then men could not experience that state or condition they call liberty. Second, contemporary attempts to achieve the liberal ideal—the perfection of "liberty"—cannot be accomplished without the continued subjugation of women, and in particular, without such subjugating practices as rape, so-called surrogacy arrangements, pornography, and prostitution.

The concept of liberty was originally devised by men during the bourgeois revolution that began in Europe in the 1600s. The purpose of the bourgeois revolution was to promote wider distribution of political and economic power among male members of the state: in effect, "liberty" was a theory of affirmative action for nonaristocratic men (Kathleen Lahey, 1983). Early liberal theory is sometimes described as antipatriarchal, since it rejected feudal patriarchy as the organizing basis of the social order. However, this antipatriarchalism did not extend to the organization of the family or to the status of women, either within the family or within the larger social context (Zillah Eisenstein, 1981). Although newly formulated liberty claims legitimated egalitarianism among males, these liberty claims depended upon the continuing inequality of women to make liberty meaningful for men.

Support for this reading of early liberal theory is not difficult to find. The practices of the Marquis de Sade, which continue to define the essence of liberty for contemporary civil libertarians ranging from Susan Sontag to Larry Flynt, included rape, sexual torture, pornography, and prostitution. Sexual practices and preferences of libertarians aside, political economists such as John Locke conceptualized property and liberty in a way that assumed the continuing male appropriation of women's productive and reproductive energies, and treated as reductio ad absurdum any suggestion that women should be treated as equals or as self-determining persons in the emerging liberal state (Kathleen Lahey, 1983).

Indeed, if the ability to engage in economic and sexual exploitation is the essence of the liberal bourgeois revolution, then women can only now be said to be emerging from feudalism. And not surprisingly, our bourgeois revolution looks a lot like the last one. Women now can—and do—play the Marquis to our sisters, whether we are lesbian or heterosexual women, inflicting pain on others for our own (and allegedly for their) sexual gratification, all in the name of sexual freedom. Women now can—and do—purchase the reproductive capacities of other women, in the name of freedom of contract. Women now can— and do—defend our rights to serve (or even to become) pimps and johns, in the name of freedom of choice. Women now can—and do—define equality as men's rights to everything that women have—including pregnancy leave, child custody, and mother's allowances—at the same time that they define women's equality claims—such as the claim that pornography harms women—as infringements on the principle of freedom of speech or expression.

In our liberal moments, we women—along with all other civil libertarians—are busily engaged in justifying the continuing inequality of some women on the basis of sex; romanticizing emotional independence as the defining core of individualism; eroticizing instrumental rationality as the way to get off sexually; and identifying "the state," rather than male supremacy in its entirety, as the source of our oppression.

-Kathleen A. Lahey, “Women and Civil Liberties” in The Sexual Liberals and the Attack on Feminism

#Kathleen A. Lahey#liberalism#civil libertarianism#radical feminist theory#liberty#female oppression#patriarchy#feudalism

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

what would you put on a political theory syllabus if you could

like an intro/survey course? so the conventional theory class in Anglo-American poli-phil goes roughly like this: Plato/Aristotle -> Machiavelli (if you fuck nasty) -> Hobbes/Locke/Rousseau -> J.S. Mill -> Marx (sometimes, and only with the disclaimer that this guy needs to lighten up!) -> omission of like 120 years of global thought, including the shifts wrought by two World Wars, postcolonialism, and 1968 -> Rawls. there's usually, but not consistently, some idiosyncratic liberal picks from the various omitted periods/regions based on whatever the academic in question is preoccupied with, or attempts (sometimes sincere, sometimes half-hearted) to add some diversity to the lineup, most typically some form of liberal-leaning writings on feminism or racism or occasionally postcolonialism.

I think this abridged history is like, okay but not great (Charles Mills' Decolonizing Political Philosophy is a great piece on why). it’s produced by a combination of both the discipline's narrow post-Rawls liberal paradigm, and the constraints of intro/survey courses, which aim for breadth rather than depth (which I think is generally reasonable at least on its face), so the trick I would want to pull off is making something that works within the latter constraint while not succumbing to the paradigm.

the question sort of demands interrogating what a theory class is for in the ideal sense, what it uniquely can offer (so, going beyond specific skills that can be developed in other ways, like learning to write, understand, critique, and respond to long-form argument, or the more cynical pipeline-to-labor stuff like credentialing).

I think some main goals would be 1) contextualizing your existence in the world as a political subject, 2) be able to pass an ideological Turing test, i.e. accurately represent the substance of different perspectives and worldviews such that you could "pass" for the authentic thing [so I would include writers/writings that I detest for KYE reasons], 3) increase your autonomy as a political agent and ability to recognize how these various concepts and systems underlie the fabric of our political language and practice and how you can apply them in reality in collaboration with others.

an extension of these goals, imo, is that political thought without a history is dead in the water - this is why I have kind of a hardline opposition to trying to learn political theory mostly through social media and why "leftist theory recs" on here usually drive me absolutely crazy. so any teaching of these readings would probably require a decent level of contextualization.

then there's a question of structure. my intro class was actually pretty enjoyable despite following the pattern described above, as my prof centered the class around different chapters of Plato's Republic, using each chapter as a jumping off point to talk about connections with a more modern political thinker while also incorporating some short fiction of Octavia Butler. cool stuff! I think organizing around theme is edifying. there's tradeoffs to doing chronological vs thematic organization of readings though, which I want to keep in mind

so with all that I think it would look roughly like this (though frankly my reach might be exceeding my grasp), and you could pretty much reorganize the readings to be chronological if you wanted:

"The Political"/Power: I think spending some time on "metapolitics" is important, like what politics is and what the function of political philosophy is. So start with some different perspectives on realism vs. idealism (the Republic, the Melian dialogue, The Prince) and sliding into competing definitions of politics as conflict vs consensus (the Arendt/Fanon and Schmitt/Benjamin "debates")

Authority: Hobbes/Rousseau/Hume on the social contract, the Crito/Thoreau/MLK on civil disobedience, ideally an anarchist of some stripe (would rather include Bakunin or Kropotkin but R.P. Wolff might be the more cohesive move)

Equality/Property: Locke's Second Treatise, Rousseau's Discourse on Inequality, The Communist Manifesto and/or Marx on primitive accumulation as an alternative genealogy of property/money, Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morality as illustrative of a reactionary/aristocratic perspective on equality (you could swap in Aristotle instead for a different take), Fanon in Black Skins White Masks

Justice: Plato, Rawls on distributive justice, Nussbaum on capabilities/global justice, Mills on the racial contract

Freedom: Mill's On Liberty, Marcuse's "Critique of Pure Tolerance," some chapters from Capital V1, "Throwing Like a Girl" by Young (plus maybe some Beauvoir/Wittig). work in Berlin and Pettit's competing ideas of liberty

then maybe end on Foucault writing in a broad mode about subjectivity OR Benjamin's "On the Concept of History" - either would be good for a kind of "call to action" that I like in a politics class

there are some concepts that might warrant their own segment (domination, violence, sovereignty, revolution, security, progress - I waffled on making "property" its own unit), but I'm trying to not go too crazy (and it's possible they could get folded into other concepts as corollaries). I'm also leaving out various authors that I do think merit inclusion (Adorno, Dewey, D&G, Lenin & Mao, Althusser, Davis, various contemporary writers), but I would probably follow the path of my Middle Eastern Politics professor - put supplemental/suggested readings in there for the freaks that like this stuff.

and finally I think the above is more tailored to be an introduction (if a somewhat sweeping one), you could take an alternative tack and construct "contemporary issues in political theory" (e.g. migration/refugees, climate, economic crisis, security state/surveillance) and I think that would also be a rewarding survey

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.2.2 Do “libertarian”-capitalists support slavery?

Yes. It may come as a surprise to many people, but right-“Libertarianism” is one of the few political theories that justifies slavery. For example, Robert Nozick asks whether “a free system would allow [the individual] to sell himself into slavery” and he answers “I believe that it would.” [Anarchy, State and Utopia, p. 371] While some right-“libertarians” do not agree with Nozick, there is no logical basis in their ideology for such disagreement.

This can be seen from “anarcho”-capitalist Walter Block, who, like Nozick, supports voluntary slavery. As he puts it, “if I own something, I can sell it (and should be allowed by law to do so). If I can’t sell, then, and to that extent, I really don’t own it.” Thus agreeing to sell yourself for a lifetime “is a bona fide contract” which, if “abrogated, theft occurs.” He critiques those other right-wing “libertarians” (like Murray Rothbard) who oppose voluntary slavery as being inconsistent to their principles. Block, in his words, seeks to make “a tiny adjustment” which “strengthens libertarianism by making it more internally consistent.” He argues that his position shows “that contract, predicated on private property [can] reach to the furthest realms of human interaction, even to voluntary slave contracts.” [“Towards a Libertarian Theory of Inalienability: A Critique of Rothbard, Barnett, Smith, Kinsella, Gordon, and Epstein,” pp. 39–85, Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, p. 44, p. 48, p. 82 and p. 46]

So the logic is simple, you cannot really own something unless you can sell it. Self-ownership is one of the cornerstones of laissez-faire capitalist ideology. Therefore, since you own yourself you can sell yourself.

This defence of slavery should not come as a surprise to any one familiar with classical liberalism. An elitist ideology, its main rationale is to defend the liberty and power of property owners and justify unfree social relationships (such as government and wage labour) in terms of “consent.” Nozick and Block just takes it to its logical conclusion. This is because his position is not new but, as with so many other right-“libertarian” ones, can be found in John Locke’s work. The key difference is that Locke refused the term “slavery” and favoured “drudgery” as, for him, slavery mean a relationship “between a lawful conqueror and a captive” where the former has the power of life and death over the latter. Once a “compact” is agreed between them, “an agreement for a limited power on the one side, and obedience on the other … slavery ceases.” As long as the master could not kill the slave, then it was “drudgery.” Like Nozick, he acknowledges that “men did sell themselves; but, it is plain, this was only to drudgery, not to slavery: for, it is evident, the person sold was not under an absolute, arbitrary, despotical power: for the master could not have power to kill him, at any time, whom, at a certain time, he was obliged to let go free out of his service.” [Locke, Second Treatise of Government, Section 24] In other words, voluntary slavery was fine but just call it something else.

Not that Locke was bothered by involuntary slavery. He was heavily involved in the slave trade. He owned shares in the “Royal Africa Company” which carried on the slave trade for England, making a profit when he sold them. He also held a significant share in another slave company, the “Bahama Adventurers.” In the “Second Treatise”, Locke justified slavery in terms of “Captives taken in a just war,” a war waged against aggressors. [Section 85] That, of course, had nothing to do with the actual slavery Locke profited from (slave raids were common, for example). Nor did his “liberal” principles stop him suggesting a constitution that would ensure that “every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his Negro slaves.” The constitution itself was typically autocratic and hierarchical, designed explicitly to “avoid erecting a numerous democracy.” [The Works of John Locke, vol. X, p. 196]

So the notion of contractual slavery has a long history within right-wing liberalism, although most refuse to call it by that name. It is of course simply embarrassment that stops many right-“libertarians” calling a spade a spade. They incorrectly assume that slavery has to be involuntary. In fact, historically, voluntary slave contracts have been common (David Ellerman’s Property and Contract in Economics has an excellent overview). Any new form of voluntary slavery would be a “civilised” form of slavery and could occur when an individual would “agree” to sell their lifetime’s labour to another (as when a starving worker would “agree” to become a slave in return for food). In addition, the contract would be able to be broken under certain conditions (perhaps in return for breaking the contract, the former slave would have pay damages to his or her master for the labour their master would lose — a sizeable amount no doubt and such a payment could result in debt slavery, which is the most common form of “civilised” slavery. Such damages may be agreed in the contract as a “performance bond” or “conditional exchange.”

In summary, right-“libertarians” are talking about “civilised” slavery (or, in other words, civil slavery) and not forced slavery. While some may have reservations about calling it slavery, they agree with the basic concept that since people own themselves they can sell themselves, that is sell their labour for a lifetime rather than piecemeal.

We must stress that this is no academic debate. “Voluntary” slavery has been a problem in many societies and still exists in many countries today (particularly third world ones where bonded labour — i.e. where debt is used to enslave people — is the most common form). With the rise of sweat shops and child labour in many “developed” countries such as the USA, “voluntary” slavery (perhaps via debt and bonded labour) may become common in all parts of the world — an ironic (if not surprising) result of “freeing” the market and being indifferent to the actual freedom of those within it.

Some right-“libertarians” are obviously uneasy with the logical conclusion of their definition of freedom. Murray Rothbard, for example, stressed the “unenforceability, in libertarian theory, of voluntary slave contracts.” Of course, other “libertarian” theorists claim the exact opposite, so “libertarian theory” makes no such claim, but never mind! Essentially, his objection revolves around the assertion that a person “cannot, in nature, sell himself into slavery and have this sale enforced — for this would mean that his future will over his own body was being surrendered in advance” and that if a “labourer remains totally subservient to his master’s will voluntarily, he is not yet a slave since his submission is voluntary.” However, as we noted in section F.2, Rothbard emphasis on quitting fails to recognise the actual denial of will and control over ones own body that is explicit in wage labour. It is this failure that pro-slave contract “libertarians” stress — they consider the slave contract as an extended wage contract. Moreover, a modern slave contract would likely take the form of a “performance bond,” on which Rothbard laments about its “unfortunate suppression” by the state. In such a system, the slave could agree to perform X years labour or pay their master substantial damages if they fail to do so. It is the threat of damages that enforces the contract and such a “contract” Rothbard does agree is enforceable. Another means of creating slave contracts would be “conditional exchange” which Rothbard also supports. As for debt bondage, that too, seems acceptable. He surreally notes that paying damages and debts in such contracts is fine as “money, of course, is alienable” and so forgets that it needs to be earned by labour which, he asserts, is not alienable! [The Ethics of Liberty, pp. 134–135, p. 40, pp. 136–9, p. 141 and p. 138]

It should be noted that the slavery contract cannot be null and void because it is unenforceable, as Rothbard suggests. This is because the doctrine of specific performance applies to all contracts, not just to labour contracts. This is because all contracts specify some future performance. In the case of the lifetime labour contract, then it can be broken as long as the slave pays any appropriate damages. As Rothbard puts it elsewhere, “if A has agreed to work for life for B in exchange for 10,000 grams of gold, he will have to return the proportionate amount of property if he terminates the arrangement and ceases to work.” [Man, Economy, and State, vol. I , p. 441] This is understandable, as the law generally allows material damages for breached contracts, as does Rothbard in his support for the “performance bond” and “conditional exchange.” Needless to say, having to pay such damages (either as a lump sum or over a period of time) could turn the worker into the most common type of modern slave, the debt-slave.

And it is interesting to note that even Murray Rothbard is not against the selling of humans. He argued that children are the property of their parents who can (bar actually murdering them by violence) do whatever they please with them, even sell them on a “flourishing free child market.” [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 102] Combined with a whole hearted support for child labour (after all, the child can leave its parents if it objects to working for them) such a “free child market” could easily become a “child slave market” — with entrepreneurs making a healthy profit selling infants and children or their labour to capitalists (as did occur in 19th century Britain). Unsurprisingly, Rothbard ignores the possible nasty aspects of such a market in human flesh (such as children being sold to work in factories, homes and brothels). But this is besides the point.

Of course, this theoretical justification for slavery at the heart of an ideology calling itself “libertarianism” is hard for many right-“libertarians” to accept and so they argue that such contracts would be very hard to enforce. This attempt to get out of the contradiction fails simply because it ignores the nature of the capitalist market. If there is a demand for slave contracts to be enforced, then companies will develop to provide that “service” (and it would be interesting to see how two “protection” firms, one defending slave contracts and another not, could compromise and reach a peaceful agreement over whether slave contracts were valid). Thus we could see a so-called “free” society producing companies whose specific purpose was to hunt down escaped slaves (i.e. individuals in slave contracts who have not paid damages to their owners for freedom). Of course, perhaps Rothbard would claim that such slave contracts would be “outlawed” under his “general libertarian law code” but this is a denial of market “freedom”. If slave contracts are “banned” then surely this is paternalism, stopping individuals from contracting out their “labour services” to whom and however long they “desire”. You cannot have it both ways.

So, ironically, an ideology proclaiming itself to support “liberty” ends up justifying and defending slavery. Indeed, for the right-“libertarian” the slave contract is an exemplification, not the denial, of the individual’s liberty! How is this possible? How can slavery be supported as an expression of liberty? Simple, right-“libertarian” support for slavery is a symptom of a deeper authoritarianism, namely their uncritical acceptance of contract theory. The central claim of contract theory is that contract is the means to secure and enhance individual freedom. Slavery is the antithesis to freedom and so, in theory, contract and slavery must be mutually exclusive. However, as indicated above, some contract theorists (past and present) have included slave contracts among legitimate contracts. This suggests that contract theory cannot provide the theoretical support needed to secure and enhance individual freedom.

As Carole Pateman argues, “contract theory is primarily about a way of creating social relations constituted by subordination, not about exchange.” Rather than undermining subordination, contract theorists justify modern subjection — “contract doctrine has proclaimed that subjection to a master — a boss, a husband — is freedom.” [The Sexual Contract, p. 40 and p. 146] The question central to contract theory (and so right-Libertarianism) is not “are people free” (as one would expect) but “are people free to subordinate themselves in any manner they please.” A radically different question and one only fitting to someone who does not know what liberty means.

Anarchists argue that not all contracts are legitimate and no free individual can make a contract that denies his or her own freedom. If an individual is able to express themselves by making free agreements then those free agreements must also be based upon freedom internally as well. Any agreement that creates domination or hierarchy negates the assumptions underlying the agreement and makes itself null and void. In other words, voluntary government is still government and a defining characteristic of an anarchy must be, surely, “no government” and “no rulers.”

This is most easily seen in the extreme case of the slave contract. John Stuart Mill stated that such a contract would be “null and void.” He argued that an individual may voluntarily choose to enter such a contract but in so doing “he abdicates his liberty; he foregoes any future use of it beyond that single act. He therefore defeats, in his own case, the very purpose which is the justification of allowing him to dispose of himself…The principle of freedom cannot require that he should be free not to be free. It is not freedom, to be allowed to alienate his freedom.” He adds that “these reasons, the force of which is so conspicuous in this particular case, are evidently of far wider application.” [quoted by Pateman, Op. Cit., pp. 171–2]

And it is such an application that defenders of capitalism fear (Mill did in fact apply these reasons wider and unsurprisingly became a supporter of a market syndicalist form of socialism). If we reject slave contracts as illegitimate then, logically, we must also reject all contracts that express qualities similar to slavery (i.e. deny freedom) including wage slavery. Given that, as David Ellerman points out, “the voluntary slave … and the employee cannot in fact take their will out of their intentional actions so that they could be ‘employed’ by the master or employer” we are left with “the rather implausible assertion that a person can vacate his or her will for eight or so hours a day for weeks, months, or years on end but cannot do so for a working lifetime.” [Property and Contract in Economics, p. 58] This is Rothbard’s position.

The implications of supporting voluntary slavery is quite devastating for all forms of right-wing “libertarianism.” This was proven by Ellerman when he wrote an extremely robust defence of it under the pseudonym “J. Philmore” called The Libertarian Case for Slavery (first published in The Philosophical Forum, xiv, 1982). This classic rebuttal takes the form of “proof by contradiction” (or reductio ad absurdum) whereby he takes the arguments of right-libertarianism to their logical end and shows how they reach the memorably conclusion that the “time has come for liberal economic and political thinkers to stop dodging this issue and to critically re-examine their shared prejudices about certain voluntary social institutions … this critical process will inexorably drive liberalism to its only logical conclusion: libertarianism that finally lays the true moral foundation for economic and political slavery.” Ellerman shows how, from a right-“libertarian” perspective there is a “fundamental contradiction” in a modern liberal society for the state to prohibit slave contracts. He notes that there “seems to be a basic shared prejudice of liberalism that slavery is inherently involuntary, so the issue of genuinely voluntary slavery has received little scrutiny. The perfectly valid liberal argument that involuntary slavery is inherently unjust is thus taken to include voluntary slavery (in which case, the argument, by definition, does not apply). This has resulted in an abridgement of the freedom of contract in modern liberal society.” Thus it is possible to argue for a “civilised form of contractual slavery.” [“J. Philmore,”, Op. Cit.]

So accurate and logical was Ellerman’s article that many of its readers were convinced it was written by a right-“libertarian” (including, we have to say, us!). One such writer was Carole Pateman, who correctly noted that ”[t]here is a nice historical irony here. In the American South, slaves were emancipated and turned into wage labourers, and now American contractarians argue that all workers should have the opportunity to turn themselves into civil slaves.” [Op. Cit., p. 63]).

The aim of Ellerman’s article was to show the problems that employment (wage labour) presents for the concept of self-government and how contract need not result in social relationships based on freedom. As “Philmore” put it, ”[a]ny thorough and decisive critique of voluntary slavery or constitutional non-democratic government would carry over to the employment contract — which is the voluntary contractual basis for the free-market free-enterprise system. Such a critique would thus be a reductio ad absurdum.” As “contractual slavery” is an “extension of the employer-employee contract,” he shows that the difference between wage labour and slavery is the time scale rather than the principle or social relationships involved. [Op. Cit.] This explains why the early workers’ movement called capitalism “wage slavery” and why anarchists still do. It exposes the unfree nature of capitalism and the poverty of its vision of freedom. While it is possible to present wage labour as “freedom” due to its “consensual” nature, it becomes much harder to do so when talking about slavery or dictatorship (and let us not forget that Nozick also had no problem with autocracy — see section B.4). Then the contradictions are exposed for all to see and be horrified by.

All this does not mean that we must reject free agreement. Far from it! Free agreement is essential for a society based upon individual dignity and liberty. There are a variety of forms of free agreement and anarchists support those based upon co-operation and self-management (i.e. individuals working together as equals). Anarchists desire to create relationships which reflect (and so express) the liberty that is the basis of free agreement. Capitalism creates relationships that deny liberty. The opposition between autonomy and subjection can only be maintained by modifying or rejecting contract theory, something that capitalism cannot do and so the right-wing “libertarian” rejects autonomy in favour of subjection (and so rejects socialism in favour of capitalism).

So the real contrast between genuine libertarians and right-“libertarians” is best expressed in their respective opinions on slavery. Anarchism is based upon the individual whose individuality depends upon the maintenance of free relationships with other individuals. If individuals deny their capacities for self-government through a contract the individuals bring about a qualitative change in their relationship to others — freedom is turned into mastery and subordination. For the anarchist, slavery is thus the paradigm of what freedom is not, instead of an exemplification of what it is (as right-“libertarians” state). As Proudhon argued:

“If I were asked to answer the following question: What is slavery? and I should answer in one word, It is murder, my meaning would be understood at once. No extended argument would be required to show that the power to take from a man his thought, his will, his personality, is a power of life and death; and that to enslave a man is to kill him.” [What is Property?, p. 37]

In contrast, the right-“libertarian” effectively argues that “I support slavery because I believe in liberty.” It is a sad reflection of the ethical and intellectual bankruptcy of our society that such an “argument” is actually proposed by some people under the name of liberty. The concept of “slavery as freedom” is far too Orwellian to warrant a critique — we will leave it up to right-“libertarians” to corrupt our language and ethical standards with an attempt to prove it.

From the basic insight that slavery is the opposite of freedom, the anarchist rejection of authoritarian social relations quickly follows:

“Liberty is inviolable. I can neither sell nor alienate my liberty; every contract, every condition of a contract, which has in view the alienation or suspension of liberty, is null: the slave, when he plants his foot upon the soil of liberty, at that moment becomes a free man .. . Liberty is the original condition of man; to renounce liberty is to renounce the nature of man: after that, how could we perform the acts of man?” [P.J. Proudhon, Op. Cit., p. 67]

The employment contract (i.e. wage slavery) abrogates liberty. It is based upon inequality of power and “exploitation is a consequence of the fact that the sale of labour power entails the worker’s subordination.” [Carole Pateman, Op. Cit., p. 149] Hence Proudhon’s support for self-management and opposition to capitalism — any relationship that resembles slavery is illegitimate and no contract that creates a relationship of subordination is valid. Thus in a truly anarchistic society, slave contracts would be unenforceable — people in a truly free (i.e. non-capitalist) society would never tolerate such a horrible institution or consider it a valid agreement. If someone was silly enough to sign such a contract, they would simply have to say they now rejected it in order to be free — such contracts are made to be broken and without the force of a law system (and private defence firms) to back it up, such contracts will stay broken.

The right-“libertarian” support for slave contracts (and wage slavery) indicates that their ideology has little to do with liberty and far more to do with justifying property and the oppression and exploitation it produces. Their theoretical support for permanent and temporary voluntary slavery and autocracy indicates a deeper authoritarianism which negates their claims to be libertarians.

#libertarians#libertarianism#libertarian capitalism#slavery#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dunbar Amnesia Novel Philosophical Concepts--The Ones I Tried To Include and Address

Essentially, in creating it, I wanted to discuss the concepts of free will, responsibility, virtue, and memory as it relates to identity. The initial premise (as you'll discover in later chapters) is: what defines a person? Is it actions, ideas, or something else? The main question I have later is: is someone responsible for actions they commit, if they have no memory of taking these actions?

I mean to supersede the idea that it was a voluntary lack of memory, such as getting blackout drunk (one chooses to do this). In the Dunbar amnesia case, Dunbar's amnesia isn't a choice he made. Does he still have responsibility for actions that he took during this time? In order to appropriately address this question, some of the works I read/re-read included pieces on Locke's concept of free will, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, Scanlon's 'What We Owe To Each Other', and Rousseau's social contract. There were a few others, but these were my main ones. Arguably, some of these are more political philosophies than thought-pieces, but I would argue they're every bit as relevant.

In the question of 'what defines a person', I wanted to look at concepts of virtues. Aristotle argues that moral virtues are not inherently held, but are gained through making choices which support them (i.e. someone can be brave, but only once they've made enough 'brave' decisions that they achieve a brave character). He also makes a claim that virtues support his concept of eudaimonia, or a virtuous and fulfilling life, 'flourishing'. So then, I ask: if decisions make up who someone is, and many decisions develop their character, if someone has no memory of these decisions---does that change who they are? In the amnesia novel, I address this by Dunbar's desire to discover 'what happened' during the forgotten years. While some of it is certainly to understand the actual events that occurred, another huge part is discovering who he'd become in that missing time. After all, waking up in a plush office with his name on a plaque is something that he considers out-of-character for himself. That's the impetus for asking: "what have I become"?

Of course, his perception of himself is exactly the same as it was seven years prior, because that's what he last remembers. Is a person's being only something they perceive, or is it a sum of how others perceive them? (E.x. if I consider myself to be noble, but my actions are terrible and others see me as awful, which am I? Noble, or terrible?) The same applies in the amnesia novel: is Dunbar the person who others see him as, or does who he is exist only within his frame of reference? Initially, I argue, that he would prefer it be the former, although it's likely the latter. Personally, I subscribe to Reader Response Theory, or the idea that each piece of writing is interpreted inherently by the readers, and the meaning was always meant to exist within their interpretation (outside exclusively what the writer intended). Why not apply the same to actions, and the being of a person? Every action has the ability to be interpreted by others, and although intentions are highly relevant (see: Scanlon), who we are as people is at least somewhat defined through how others see us.

In matters of memory, amnesia challenges the fundamental idea that you're made up of your actions, or that you're defined by how others see you. It suggests that because you still have a sense of self and a being, even if you cannot remember your actions for, say, the last seven years, something is still making up you. A question: if you cannot remember the virtuous actions you took, are you still a virtuous person? Is part of what made you virtuous the fact that you had the capacity to take those actions? If people perceive you as having virtue but you can't remember being virtuous, does it still count? These questions are not answered, but I do argue in the novel that there's a greater essence that defines you, and it lies in the decisions you make and determine in the present--outside of external or past judgements and decisions.

As an aside that's a little bit further apart from my whole essay-portion here, I've intended different characters to have specific philosophical viewpoints. The Clevinger/Dunbar line-up has a few different dichotomies that I think enhance the plot if you read the characters as adhering to these different principles, whether knowingly or not. While I'd like to say that at least one of them follows deontology (actually... hm. I'm going to go ahead and say Clevinger likes to think he's a deontologist), I know that Dunbar at the very least is a consequentialist (NOT subscribing to utilitarianism). I think that's very relevant for him in the amnesia novel, as it explains why he experiences cognitive dissonance between the actions he took that he can't remember and the consequences of these actions.

Already, you have their line-up between idealistic optimism/nihilistic pessimism, deontology/consequentialism, existentialism/pragmatism, and a few others. The amnesia novel almost serves as a thought experiment in regard to these, and the benefit to having characters with different moral structures allows for debate and evaluation of the situations from multiple philosophical perspectives.

#obviously there is more but i just wanted to get my thoughts out#my writing#amnesia novel#catchllection#uhhh i'm gonna be annoying and put this in the tag#catch 22#philosophy#for those of you who have the tag blacklisted

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

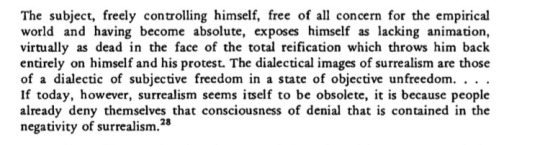

SOME ADORNO SHIT 😱😱😱

Happy Feodor Friday!

Theodor W. Adorno, praise be his name, quoted in Bürger 🍔, Theory of the Avant-Garde:

Adorno here saying that surrealism is artificial. No dip sure lock! Nah it’s like this. Adorno is a vehement evangelist for the avant garde in the arts; but for Adorno, the avant garde still has to express what is true: in fact, this is why Adorno advocates for the avant garde. For Adorno, the world is one of ‘objective unfreedom’ — more particularly, the crushing and fascistic sameness and fungibility of all things as they must bend to the iron law of exchange value. You might then think that Adorno would hold that only art works which somehow convey or portray that objective unfreedom are ‘true’ in his sense. Yes and no: for if that were only the case, then Adorno would have no problem with pictorial painting that portrays quotidian tyranny and subjugation, or, in music which was his specialty, any schmaltzy gothic or warlike triumphalist music would pass muster. No, for Adorno, somewhat paradoxically and perhaps simply nonsensically on his part, an autonomous art work is itself something of liberation.

An atonal serialist piece of music (Schoenberg, etc) or an expressionist painting (Kandinsky) or avant garde work of literature (Joyce) — these things, for Adorno, mark truth in the sense precisely that they subvert the world of exchange, that they refuse harmony and embrace dissonance and ‘laceration.’ Because what the ‘culture industry’ sells is escape, escape into a comforting and thought terminating sameness, the comfort of representation and repetition. That which is lacerated, dissonant, atonal etc reflects what is wholly ‘true’ in being itself as against being a facsimile of the world sold back to us. This is closely related to Adorno’s critique of Enlightenment modernity’s replacement of the qualitative with the quantitative. From the magisterial essay The Concept of Enlightenment (with M. Horkheimer):

Do you get it? I’ll translate, I’m used to this guy. The illusion of magic he refers to here is the socially inscribed primitive process of endowing some particular thing, like one single tree, with its own essence and quality, or mana. As this vanishes with enlightenment modernity, quantitative repetition reigns: a tree is only a specimen of the scientific object called ‘trees’ (yeah they’re just called trees dude, no Latin.) But note the highlighted section here: very importantly, he emphasizes how this notion of the ‘return of the same’ is already implicit in myth (or in totemic society.) Adorno doesn’t wish, then, to ‘return’ to the animism and ‘essentialism’ (in the sense of ‘an essence’) that came with primitive myth.

So the standard for truthful art can’t be that the work of art answer only to its own qualitative internal logic. Rather, it is ‘mediated,’ a fancy dialectics term that essentially means that the thing in question does not simply stand on its own unmolested by anything—it is always necessarily mediated by social conditions. I think the key to this puzzle is this: an art work cannot help but be mediated. Once a painting hangs in a gallery or a song plays at a concert, it is no longer answering only to itself, rather, it, as a work of art, is changed by the interaction it has with what is not-it, by what is outside of it and helping thereby to constitute it as such. The question then becomes, of course, by what is an art work mediated? By consumer society? So you can see perhaps now how it comes around: an art work which pushes towards subversive form and content, it is thereby far less likely to be effaced by the mediation of Capital or of ‘mass culture.’ Safeguarding against the latter is no easy task (take it from me, I am swamped in interview requests, book deals, and big music label contract offers!) That’s why Adorno is such a snobby bitch with the rigorous twelve-tone atonal music stuff and all that. It resists being…listenable…imagine if Gerwig pitched the Barbie movie where Barbie is an electrical wire hanging out of the dirt and all that happens is that an eyeless medieval police officer shouts “BARB!” into a megaphone. You know

So let’s get to the surrealism thing in brief, from the Peter Bürger 🍔 citation up top. There are radically different modes of surrealism that I believe pass muster varyingly with Adorno’s aesthetico-political concerns. And I’m gonna illustrate that with some pictures.

In my head canon I very reductively sometimes split early 20th century surrealist paintings into the Mexican and the European schools. Just as a shorthand. The two paintings below come from the former school, the first (left) by Max Ernst, who was a part of the Mexican ‘scene’ with his wife Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, and the painter of the second of the ‘Mexican’ pieces here, Remedios Varo.

Now I love this shit, of course, but it’s easy to see why Adorno would not be as enthused about the radical potential in this (very broad) style (that I’m simplifying for brevity and effect.) Ernst portrays two giant beasts, a multiple-eyed chicken-like thing and a frighteningly shrouded Beast Witch; in Varo’s, a solemn sorceress mixes a potion that fuels the rotation of parchment upon which dead faced women servants write incantations, all in a tower looming atop a hilltop village that appears to be waning into the abyss. There’s obviously an element of fantasy, of imagined dream-magic and atavism that one might suspect would fall too easily into the ‘escapist’ sort of category for Adorno.

This next set, the ‘Europeans,’ is two paintings by the classic era surrealist Kay Sage, and the contemporary artist Claire Trotignon (one of my very favorite contemporary visual artists):

Kay Sage, drawing upon de Chirico before her, as well as her husband Yves Tanguy, paints these haunted, uncanny landscapes without determinate objects. The forms and contours of the modern, enlightened built world, stripped of their signification, stripped violently and denuded of their ostensible promise to be a site of human freedom. Trotignon’s pieces simultaneously erect and dismantle structures of ambiguity, emptiness and dissonance — similarly to Sage’s. They harrowingly and somewhat beautifully express Adorno’s “negative” dialectic — wherein, again, “a consciousness of denial” is at issue in the mediate artist-viewer co-constitution. They resist being iterations of something by resisting being something, apart from that lost or negated sense of rational sensibility that recedes into the abyss in capitalist modernity.

#Adorno#critical theory#feodoradornofridays#abstract art#hiremejuxtapoz#artforum#needworkfrieze#avant garde#kay sage#max ernst#remedios varo#claire trotingnon#Peter burger

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORTIMER ADLER’S READING LIST (PART 2)

Reading list from “How To Read a Book” by Mortimer Adler (1972 edition).

Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism; Rape of the Lock; Essay on Man

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters; Spirit of Laws

Voltaire: Letters on the English; Candide; Philosophical Dictionary

Henry Fielding: Joseph Andrews; Tom Jones

Samuel Johnson: The Vanity of Human Wishes; Dictionary; Rasselas; The Lives of the Poets

David Hume: Treatise on Human Nature; Essays Moral and Political; An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: On the Origin of Inequality; On the Political Economy; Emile, The Social Contract

Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy

Adam Smith: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; The Wealth of Nations

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason; Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals; Critique of Practical Reason; The Science of Right; Critique of Judgment; Perpetual Peace

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Autobiography

James Boswell: Journal; Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier: Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry)

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Federalist Papers

Jeremy Bentham: Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Theory of Fictions

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust; Poetry and Truth

Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier: Analytical Theory of Heat

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit; Philosophy of Right; Lectures on the Philosophy of History

William Wordsworth: Poems

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Poems; Biographia Literaria

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice; Emma

Carl von Clausewitz: On War

Stendhal: The Red and the Black; The Charterhouse of Parma; On Love

Lord Byron: Don Juan

Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism

Michael Faraday: Chemical History of a Candle; Experimental Researches in Electricity

Charles Lyell: Principles of Geology

Auguste Comte: The Positive Philosophy

Honore de Balzac: Père Goriot; Eugenie Grandet

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Representative Men; Essays; Journal

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

John Stuart Mill: A System of Logic; On Liberty; Representative Government; Utilitarianism; The Subjection of Women; Autobiography

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species; The Descent of Man; Autobiography

Charles Dickens: Pickwick Papers; David Copperfield; Hard Times

Claude Bernard: Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience; Walden

Karl Marx: Capital; Communist Manifesto

George Eliot: Adam Bede; Middlemarch

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick; Billy Budd

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment; The Idiot; The Brothers Karamazov

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary; Three Stories

Henrik Ibsen: Plays

Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Anna Karenina; What is Art?; Twenty-Three Tales

Mark Twain: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; The Mysterious Stranger

William James: The Principles of Psychology; The Varieties of Religious Experience; Pragmatism; Essays in Radical Empiricism

Henry James: The American; ‘The Ambassadors

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Beyond Good and Evil; The Genealogy of Morals; The Will to Power

Jules Henri Poincare: Science and Hypothesis; Science and Method

Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; Civilization and Its Discontents; New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

George Bernard Shaw: Plays and Prefaces

Max Planck: Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory; Where Is Science Going?; Scientific Autobiography

Henri Bergson: Time and Free Will; Matter and Memory; Creative Evolution; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion

John Dewey: How We Think; Democracy and Education; Experience and Nature; Logic; the Theory of Inquiry

Alfred North Whitehead: An Introduction to Mathematics; Science and the Modern World; The Aims of Education and Other Essays; Adventures of Ideas

George Santayana: The Life of Reason; Skepticism and Animal Faith; Persons and Places

Lenin: The State and Revolution

Marcel Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy; The Analysis of Mind; An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth; Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain; Joseph and His Brothers

Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; The Evolution of Physics