#Was Frankenstein Not the Monster?

Text

While I’m still sitting here waiting for my copyright confirmation to come back from the war, I figured there should be the equivalent of some thematic tunes to fill the time as we’re metaphorically left on hold with the publication process.

To that end, have some soundtracks.

The Vampyres

The ideal playlist to seduce, slaughter, or run for your unlife to. And…

Was Frankenstein Not the Monster?

The perfect soundtrack for some alchemically eldritch menace wrapped around the lively carcass of a novel which also had its birthday in the stormy summer of 1816 alongside a certain Vampyre. Give or take some appearances from other eerie neighbors. (Machen and Chambers say hello.)

And, seeing as we are all playing the waiting game with our bastard of a bloodsucker and his grim shadow, how about some new reading material?

If you’re interested in a preview of Was Frankenstein Not the Monster?, take a look here or on my website, here.

#hope you enjoy the tunes :)#the vampyres#was frankenstein not the monster?#my writing#music#spotify#Spotify

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

mary shelley writing about a monster rejected and abandoned by its creator and dedicating it to her own father i need to smoke a blunt with her i need to give her head

#there are parallels even in the creature’s journey to geneva to find frankenstein and matilda’s fantasies of a pilgrimage across the world#in search of her father#searching for eden finding yourself in hell#the fall into monsterous womanhood#and so on

86K notes

·

View notes

Text

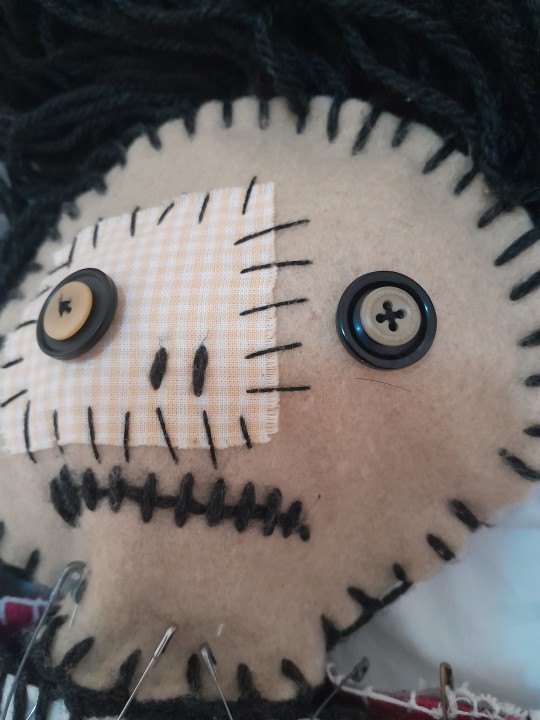

I'd like to introduce to everyone this horrid thing I created about a year ago but haven't shown many people yet (probably for the best).

This is Baby. AKA The Monster. AKA Sight Tremendous and Abhorred, AKA Vile Insect, AKA A Thing Such As Even Dante Could Not Have Conceived, etc, etc. It's made from bits of scrap fabric I scrounged from various sources and is roughly the size of a human toddler. Its design is based on Mary Shelly's original descriptions of Frankenstein's creature.

But that's not all! Behold!

You can dissect this little abomination to reveal a full set of crocheted, knitted, and scrap fabric organs, all hand-stitched by yours truly!

It has a heart, stomach, lungs, liver, small and large intestine, kidneys, bladder, and, of course, a brain! So it can ponder the horrors of its own existence!

I used this pattern by Less Than Three for the heart. I ended up felting it because I screwed up most of the stitches (I was relatively new to crochet at the time). The result was a bit of a blobby mess, but oh well.

So yeah. This thing lives in my house now (my family hates it). I have yet to reap the full consequences of my hubris.

#frankenstein#crafts#sewing#crochet#knitting#craftblr#yarn#creepy cute#horror dolls#hand stitching#little guy#creature#anatomy#monster#gore#kind of

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

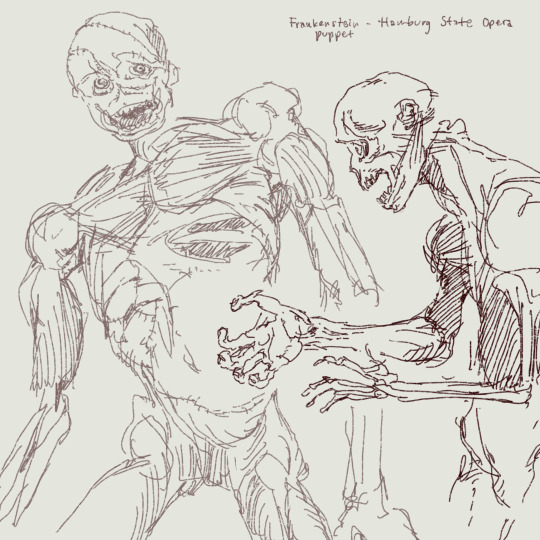

The Creature from Frankenstein at Hamburg State Opera

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched Lisa Frankenstein 6 times in the last 48 hours. This movie...

Pose ref under cut

#lisa frankenstein#lisa swallows#the creature#frankenstiensmonster#frankenstein#jennifers body#monster romance#lers fucking go#this movie is so t4t

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Weird thing enjoyer found another weird thing to enjoy

Various Frankenstein doodlings. Abt half were from reference half from imagination.

Most of these are related to the Royal Ballet version which I watched a video of the other day. So good and such a wild combination. The elegant medium and the grotesque subject matter.

I also had to draw that amazing puppet version that was made for the Hamburg state opera. lil cutie he is

#my art#frankenstein#victor frankenstein#frankenstein ballet#the royal ballet#creature design#sketches#digital sketch#monster art#monster#horror art#gesture drawing#gesture study#gesture sketches#gothic literature#gothic lit art#frankenstein fanart

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

YALL asked for more lisa frankenstein fanart

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

A genius scientist who became a vampire after an accident & A monster friend who keeps being altered her body by the scientist to avoid death (they used to be normal human best friends)

#milsae#ocs#original#vampire#frankenstein monster#both women#i already love them so much haha#need to draw more of them!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

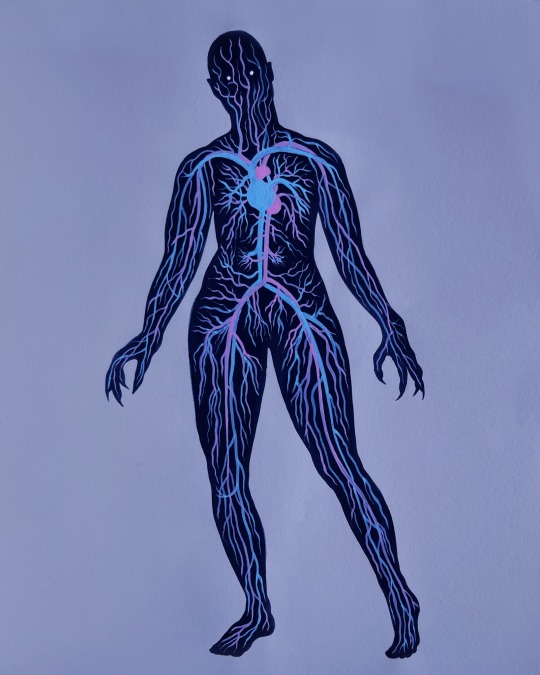

The Making of a Monster

#frankenstein#monsters#anatomical art#scientific art#painting#art#gouache#acryla gouache#mary shelly's frankenstein#sketchbook#illustration#traditional painting#watercolor

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Beware; for I am fearless, and therefore powerful.

#frankenstein#mary shelley#gothic literature#monster#gothic lit#gothic art#illustration#my art#Alternative caption: he asked for no pickles >:(#I wanted to get a more clear lightning theme in here but eh I think it turned out well enough#victors face says: yes I made this abomination against nature. and what?#ok enough of them getting along time to return to the insanity and violence

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Was Frankenstein Not the Monster? PILOT

A fire of too many colors swallows a manor in the countryside and descends into a pit.

An occult detective's prying leads to revelations far more volatile than the mere aftermath of a nightmare.

Men and monsters circle at the edge of a legend that should have died in the cold almost 100 years ago.

And in the dark beyond that edge, strange Creatures watch and work and wait.

…Such is the stage set for a new piece under the working title of Was Frankenstein Not the Monster? I make no promises—certainly none the size of Barking Harker—but at the moment, this project has been eating up much of the time I’ve spent while juggling the publication of The Vampyres. As it stands, I think I might be making another book.

If you’re interested, the preview is below the cut, but also available here and through a link in my website, here.

Was Frankenstein Not the Monster?

C.R. Kane

Every muscle palpitates, every nerve goes tense—then the body rises from the ground, not slowly, limb by limb, but thrown straight up from the earth all at once. He did not yet look alive, but like someone who was now dying. Still pale and stiff, he stands dumbstruck at being thrust back into the world. But no sound comes from his closed mouth; his voice and tongue are only allowed to answer.

—Scene of a necromantic conjuring by Erichtho, as depicted in Lucan’s Pharsalia.

“I see by your eagerness and the wonder and hope which your eyes express, my friend, that you expect to be informed of the secret with which I am acquainted; that cannot be; listen patiently until the end of my story, and you will easily perceive why I am reserved upon the subject. I will not lead you on, unguarded and ardent as I then was, to your destruction and infallible misery.”

—Victor Frankenstein, as penned by Capt. Robert Walton, edited and distributed by M. Wulstan, in the epistolatory document referred to alternately as The Legend of Frankenstein, ‘The Walton Letters,’ or, ‘Lament of the Modern Prometheus.’

THE MODERN PROMETHEUS! THE MANMADE WRETCH!

WHO IS THE MONSTER?

THE HORROR, THE HUBRIS, THE HAVOC!

ALL COME TO ELECTRIFYING LIFE IN…

THE NIGHTMARE OF DR. FRANKENSTEIN!

Based on the lauded literary terror penned by the late Robert Walton and brought to public light by M. Wulfstan, The Legend of Frankenstein.

The Apollo Crest Opera House presents the most harrowing take on the mad doctor and his marvel of creation to date.

Featuring up-to-date theatrical effects and the most stunning visuals ever seen on the stage, this is a show to whiten the locks and deliver endless shocks.

Come to GASP, to WEEP, to SWOON, and above all, ladies and gentlemen, to PONDER the century-old query beneath the fear in this tale of a creature crafted from the dead and the proud madman who dragged it into the world!

When the passerby corrects you, claiming the scientist is Frankenstein rather than the monster, remember to ask in turn:

WAS FRANKENSTEIN NOT THE MONSTER?

1

The Inferno of Erichtho

While Dyson’s was one of many heads turned by the events surrounding the housefire of Dr. Richard Geber, he was one of few interested parties who arranged a stay in Surrey’s countryside to ogle the site in person. The other who rode with him was, stunningly, Ambrose, one of his oldest friends and the staunchest recluse he had ever known. Dyson had suggested they try to wheedle Cotgrave, Phillips, and Salisbury all together for a full holiday, if only half in jest.

But where eager Cotgrave was anchored by familial obligations, Phillips and Salisbury were merely hesitant in matters of the uncanny. In truth, the latter pair had positively gawped at him. Their eyes asked wordlessly if the stamp of inhuman horror had magically been blotted out of his memory or if he’d simply abandoned sense altogether. Dyson laughed at the looks, especially Salisbury’s. He of the straight-lined life and the wincing insistence that Dyson keep all answers to himself when it came to the mystery of Dr. Black and the query of Q, only to come slinking curiously back with questions upon seeing Dyson’s haggard mien post-discovery.

As if reading the memory in him, Salisbury’s face flamed and turned away while Dyson continued, “My friends, I would no sooner part with the haunting of those experiences than a writer of penny horrors would relinquish the muse of his nightmares. Ambrose here will rightly call it perverse with you—he is the adept where I am the amateur—but he knows the worth of retaining the proofs of what he calls ‘sin’ and we politely deem merely the ‘weird’ or the ‘supernatural.’ Cotgrave, dear fellow, you at least have an open mind on the subject. If we can manage it, would you appreciate a souvenir of the strange ash for your desk?”

“Cotgrave,” Phillips had cut in with an aridity to dry the ocean, “has not been put into contact with anything more harrowing than some poor child’s grotesque diary. He and I,” he’d nodded to Salisbury who was muffling himself with the wineglass, “had the dubious fortune to play witness to the far end of your direct jabbing at the unknown, neither of which bore anything but blighted fruit. The sight of that miserable treasure hunter’s golden relic was more than enough for me. Salisbury, for his trouble, had enough poisonous proof poured in his ear as thirdhand storytelling to make him rightly uneasy, followed by wondering whether you had been struck by some ailment after prying too far.” He’d turned fully to Salisbury. “Has Dyson ever breathed a word of what it was that shocked that new white up his temple after chasing the scrap of a cipher and Dr. Black’s work?”

It was Dyson’s turn to look away. He had not told Salisbury about Travers’ shop. Certainly not about the opal and what it held. Nor would he ever. He knew even the most sublime prose would fail to do the spectacle or its horror justice. Salisbury would suffer for it, as most of his friends would, and so he burned his tongue with holding the story in. For the most part.

He’d broken enough to recite the event to Ambrose in tragically plain terms. Ambrose had nodded, recorded his statement in one of many journals kept for the purpose of notes and scrapbooking, and shelved it away with the rest of the flotsam that clogged the bookcases which stood in for his walls. The recluse gave his oath not to breathe a word of the case’s final act to another.

“At least not until you are too dead to speak on your own behalf,” Ambrose had added. Dyson found the terms satisfactory.

Yet the fact of his having an encounter so disturbing he’d not even shared it with his most sober of friends still managed to work against his invitation to the strange scene in Surrey. Even Cotgrave shook his head.

“No need of the ash, my friend. I will settle for a description of whatever you dredge up in those hills.” Dyson noted the sickish pallor that washed over him as he pronounced the last word. Phillips shifted uncomfortably in his own seat. Salisbury ran out of wine to nurse and set his glass aside.

“I will be curious of whatever account you bring back,” came his intonation, “if only to know whether you are treading on more tangible toes than some unseen wraith’s.” Salisbury had canted his gaze sharply at Dyson. “No, you have not told me what it was you did upon following the trail of breadcrumbs I mistakenly revealed to you. But I would be a fool not to assume you went and did something unwise regarding the business of those strangers in the note. Q and friends and whoever else. They are real people. Just as Dr. Steven Black was. Just as Phillips and the whole of London recalls the late Sir Thomas Vivian being quite real, and more immediately dangerous than any bogeyman lurking beyond our respective brushes with the so-called supernatural.”

“Sinful,” Ambrose corrected over the rim of his own glass.

“Indeed,” Salisbury sighed. Dyson did feel a trifle apologetic toward the man. He seemed to have aged a decade since he’d stepped back into his life. “But be they supernatural or sinful or just plain mad, human monsters are the more prolific villain of the world, and far easier to cross paths with. Dr. Richard Geber was a man of considerable notoriety with, I would wager, any number of watchful vultures in the branches of the family tree and as many serpents playing patron to his less savory works at the roots.” He’d leaned in, regarding Dyson and Ambrose in the same plea. “Do your sightseeing if you must, but be wary of what prying you do whilst playing occult detectives. A man seeing a nuisance is far more likely to take action against it than any monster.”

Dyson sadly lost his opportunity to assure Salisbury and the rest of his planned caution, as Salisbury had used the word ‘occult’ and set off a fresh avalanche from Ambrose. Talk plunged into proper distinctions of the extraordinary and the eerie, somehow managing to trip into a round of storytelling that marched through the suicide epidemic of certain well-off young men who he theorized had each encountered the same unearthly stimulus whose knowledge could not be lived with, around to an ugly room in a rented country house with a habit of seeding a mirrored insanity in wives and daughters who spent too long in the sight of its irregular damask walls, and all the way to the facts in the case of the pseudonymous M. Valdemar, that mesmeric scandal that might not have been half so sensationalized as cynics might declare…

Salisbury had put his head in his hands while Dyson, Cotgrave, and Phillips settled in for the monologue, feeding the orator only what flints of dialogue were needed to roll him further on. Were he onstage, Ambrose would have deserved a lozenge, a bouquet, and ten minutes’ applause.

That was then.

In the now, Dyson and Ambrose sat in their car, preemptively swaddled against the first drifting motes of snow. November seemed only to have warmth enough left with which to give Geber’s estate its theatrical sendoff with its roiling thunderheads and dancing lightning. With that performance done, the sky handed its reins off to winter’s sedate styling. The train drew itself along under a ceiling of gauze and into the broad country whose rumpled hills and evergreen treetops were already hiding themselves in caps of cold white. Not that such seasonal flurries would have been any more help to the roasted manor than the downpour of the incendiary night had been.

Dyson riffled out the sections of newsprint he had brought along for the trip.

Headlines bellowed across the earliest of them:

STORM-STRUCK IN SURREY!

SPARKS FLY OVER GEBER’S BLAZE!

BLINDING FIRE DEVOURS MANOR OVERNIGHT!

And so forth.

The sum of these pieces was a remarkable series of witness reports from the staff who’d escaped the building before they could burn with it. Miraculously, every member of staff had made it out with barely a scorch mark between them. Even the horses, hens, and hounds of the estate were unscathed. It was only Dr. Geber and, the staff declared, a number of colleagues who had remained inside. Corroboration from the nearest towns confirmed that Geber was indeed housing several ‘learned gentlemen’ under his expansive roof for the purpose of some private experiment being undertaken in his home laboratory.

All that saved the staff from especially sharp scrutiny was the likewise-confirmed evidence of just where that laboratory was located.

“Geber had it all built underground,” claimed more than one servant. “He up and abandoned the one he kept at the top of the house half a decade back. Had a whole little nest of catacombs hollowed out lower than the cellar, moved in all sorts of equipment and chemicals and such. We saw it all go through the big double doors he had set in the back of the house. Figured him and his fellows would come up by that way or the little stairwell indoors. Whoever wasn’t eaten up by the blast, at least.”

The blast which had not come from the heavens by way of the frantic lightning that night, but from right under the floorboards. One poor girl, Elsa Godwin, had gone down to fetch a jar of preserves and been the first to hear a series of what sounded like detonations rattling up from the ground. A distant crackle, a hair-prickling hum, a string of boom-boom-boom, all muffled by earth and concrete. That, and men screaming. There was barely time to hear as much before she also got to play first witness to the memorable fire; a blaze that begun at once to eat holes through the floor and western wall of the cellar.

“I thought I was dreaming at first,” to quote Miss Godwin. “It all felt too impossible to be happening while I was awake. The fire only made it seem less real. Real fire isn’t supposed to work that way, you see? Real fire, it meets a solid wall of dirt or rock and that’s as far as it goes. Singes it, maybe, but it can’t just go burning through everything like it’s a paper dollhouse. But that was just what it did. While it was eating its way up the stairs to the doctors’ laboratory, it punched on through to the cellar. And even that I may have accepted as real enough, but for the look of it.”

The look of that fire was described by her, by her coworkers, by those who rode up to gawk in person or make a feeble attempt at playing fire brigade, and even by a number of technical witnesses who could see the glimmer of it from their far-off windows, all in varying states of poetry or dumbstruck curtness.

The fire had not been orange.

The fire had been black. And white. And yellow. And red. All of these at once, every flame throwing its improbable light as if it fell through some nebulous crystal. Its palette might have been more enchanting if it weren’t for the fact that it was, as Miss Godwin and many more would claim, a fantastically voracious thing. So much so that Miss Godwin had scarcely made it back up the steps to shout the alarm before tongues of fire were poking up through the floor.

It truly was a miracle that everyone aboveground had fled in time. The second miracle had come from the fact that, even lightning-struck as the roof was, it remained mercifully solid while the multihued fire ate up the lower floors. So solid that Fate kindly used it as the hand to snuff the monstrous blaze. The walls turned out to be so quickly enfeebled by their change to ash that they could no longer support the heavy slants and shingles. So the roof had crushed the creeping flames under its lid, dousing the fire with sheer speed, weight, and luck. It was as unlikely a thing as a man crushing a viper’s head flat with his fist before it could bite.

Another bittersweet bout of good fortune came from the positioning of the laboratory itself. Whatever state the subterranean workings had been in post-explosion, they apparently made for an efficient ashpit. When the roof slammed down, it compacted everything below directly into the waiting pocket of hollowed earth. What could have been a conflagration was tucked tidily away almost as soon as the proverbial match was struck. Though it had doubtlessly come at the cause and cost of the very men who had sparked the fire with some experiment gone awry.

“Some manner of chemical flame, a catastrophic bungling of electrical tinkering, or both,” professed numerous experts hunted down in their own labs and campuses. Dyson imagined they were perhaps a bit put out that Geber had done them the simultaneous mercy and unspoken insult of not inviting them to join whatever it was he and his colleagues had been dabbling with. An experiment of such secrecy and apparent potency that the man had not only tunneled out a buried laboratory for it, not only erected new stone walls and double-locked iron gates around his home, not only scoured fields across the scientific spectrum to people its undertaking—for chemists, engineers, technologists, surgeons, and sundry in-betweens were numbered among the missing and/or immolated dead—but even hired on a number of ‘attendants’ that the surviving staff recalled as having staggering guardsman physiques.

All this to keep the experiment hermetically sealed and shielded.

All this, only for a number of ears at the nearest pubs and markets to catch wind of the thing’s name anyway: Project Erichtho.

A secret experiment named for the necromancing witch of legend could only be yet another spur to the public imagination, turning a noteworthy housefire into a potential hellish horror story. Requisite headlines included:

FRANKENSTEIN’S ACOLYTE, ERICHTHO’S ECHO—DR. GEBER’S UNHOLY HEROES!

PROJECT ERICHTHO’S PARANORMAL PYRE!

SORDID SECRETS AND A DOCTOR’S DEADLY DESIGN: THE KINDLING FOR THE INFERNO OF ERICHTHO?

“It could be he’s gone on to join his heroes in a sordid afterlife,” some would say in tones that alternately scorned or cooed. “Faustus and Frankenstein may have a place waiting for him in a deeper inferno. It’s the sort of thing one gets from prying too far into Nature’s business, after all.”

So on and so on. Dyson had clipped everything of interest and strung the whole thing into a sort of haphazard file in contrast to Ambrose’s tidier pasting. Ambrose was even polite enough to feign renewed interest in the piecemeal newsprint despite the information being doubtlessly memorized already.

“Not memorized,” Ambrose said over a headline declaring Geber had conjured the Devil in his cellar. He opened his coat as if displaying illicit wares, flashing the holster where he kept a waiting notepad and pen. His was an especially tailored overcoat with a number of buttoned and hidden pockets for all his necessities. One might think he hardly needed his luggage but for a change of clothes. “My cheats are simply copied out and kept close like a good pupil’s before an exam.” He patted the lapel back in place. “I am not a man made to leave his cave often, Dyson. Therefore I must wrap myself as much in my mobile cave as I can.”

“Would that not make it your shell?”

“I suppose it would. It is a difficult thing for a snail or tortoise to be robbed of his home. Unless the thief is some errant bird after the homeowner, of course. But for all that I have my faiths and proofs in the uncanny, your Salisbury was right. Men are the most common threat to a man. They rob one of goods and life at a moment’s notice far more than any aberration.”

“Ah, that begs a question I’ve meant to ask.” Dyson waved his helping of papers as a baton. “You know the reality of seemingly unreal things. What you call your sinful, wrong, not-meant-to-be sort of phenomena and entities. Were you to find yourself cornered in the proverbial dark alley with an ordinary mortal cutthroat at one end and an unearthly bogeyman at the other, which villain would you risk?”

Ambrose offered a sliver of a smile and turned his attention back to the snow flitting by the window. He passed his helping of newsprint back blindly.

“You have only listened to my rambles with half an ear,” he said. “It’s true that what you would dub the supernatural I would call sinful, but I have yet to declare such things innately villainous. Otherworldly, yes. Eldritch is a decent term. Unwelcome too, at least in what we deem sane and right by the laws of Nature or our manmade structures. Or, to satisfy the macabre itch, yes, I would deem the whole breadth of it horrific. And yet, for all that we have assembled a fair collection of events that ended in death or worse as a result of crossing bizarre influences—indeed, enough to condemn many in, say, the demoniac terms of evil—the fact remains that even a living horror is not guaranteed to be villainous. To that end, let us look at your scenario. If I knew for a fact the ordinary man at one end of my alley intended absolutely to kill me, knife ready for my throat whether or not I handed over my money, whereas the horror at the other end was a complete enigma? I would simply have no choice but to remain still.”

Dyson lost himself to a laugh and crowed, “That is no answer! The scenario was a choice. Who do you risk pushing past? The common murderer or the uncommon enigma?”

“The threat,” Ambrose pronounced carefully, “of a horror is in the uncertainty of what it is and what such a thing is capable of. The cutthroat means to kill me, yes. But the horror? It may mean to end me as well, but in a far more hideous way. In fact, it may intend to inflict something far more unthinkable than the mercy of mere execution, such that the cutthroat would be a blessing of euthanasia by comparison.”

“Ah,” Dyson jabbed his paper baton again, “so you would take the cutthroat for the certainty of him.”

“No. I would remain still.”

“Ambrose—,”

But Ambrose held up his hand.

“I would remain still until one or the other proved himself the lesser evil. For the horror at the other end of the alley may have no ill design whatsoever. Being frightening does not immediately qualify the monster in question as a villain. After all, how many legendary monsters of old have we revealed as mere animals? How many unfortunate souls are there in the world, born with off-putting ailments or disfigured by circumstance, who possess the purest of Good Samaritan character? By the same measure, how many are there with the faces of Venus and Adonis who scatter only petty cruelties in their wake? Even creatures as humble as the common spider will terrorize some of the hardiest men as much or more than their wives. Yet the spider is there to help, tidying flying pests from the home just as the pretty housecat unsheathes her teeth and claws only to bloody her keeper’s hand.

“In short, a horror will horrify, naturally. A horror is capable of far worse things than any human effort. But a horror is not inherently a villain. I am happy to keep things in the hypothetical until I am faced with the awful choice in person, but should I choose to wait, to remain still and force one or the other to make his move, I am certain the motives of the inhuman party would be made clear. It would strike, or retreat, or…”

“Or what?”

“Or it would do as the first horrors of Creation did and be as an angel. Fallen or otherwise.” The topic clipped there as the station came into view.

Fighting the frost and the numb-faced arrival at their rented lodgings sponged up the rest of the day’s energy between the two of them. A hasty dusk and a heavy supper knocked both men back in their chairs and soon the ruddy comforts of the inn dragged them down into an early night.

Ambrose, Dyson was unsurprised to see, had turned into an insomniac so far from his preferred den. He was at the window puffing at the little ember in the clay bowl and staring out at the dark when Dyson finally surrendered to his bed midnight. Come morning, Dyson found he remained at his perch, puffing still.

“I did sleep,” Ambrose assured before the other could speak. “On and off. My dry eyes played traitor and made me lose watch for a few hours at a time.”

Dyson stilled in the effort of lacing his boots. He saw that the faint pouches that had been under his friend’s eyes last night had only deepened. The ashtray set on the windowsill was full.

“Geber’s housefire notwithstanding, I can’t imagine there’s anything worth spying on in these parts. Especially not on a moonless night.”

“It wasn’t moonless,” Ambrose said as he rubbed crust from either eye. His head gradually creaked away from the window to face Dyson. “I saw it come out in cracked clouds here and there. It helped somewhat, but I could still make out a little of the show either way.”

“What show was that?”

“I’m not certain. Some kind of domestic dispute? It involved either a very mad or a very sad individual on a rooftop.”

“What?”

“He got down alright. A giant came to gather him up and bring him indoors.”

“…How much did you have to drink after I went to bed?”

“Not a drop. The whole of it took place with that little house out toward the east there. You see?” Dyson followed where Ambrose pointed. There were numerous petite houses sprinkled along the crest of a far cluster of hills. He was about to point out the issue when his gaze caught on one that stood out from its siblings. Ambrose defined it at the same time, “It has its fresh cap of snow all ruined by their footprints. The man’s little pinpricks and the giant’s awl marks, so to speak. It happened that as I was woolgathering, a yellow light came on in the upper window. The shape of a man blotted it for a moment before the window swung open and the fellow climbed out.

“It wasn’t a pleasant sight even at a distance. He didn’t move like any climber I ever saw. More like,” Ambrose made a face, “I don’t know. An animal? An insect? Something like that. Whatever he was, he made it up there. So I assumed by how the darkness erased him when he skittered up. The first crack in the clouds helped me here, for it dropped a yellow beam on the house and showed the man standing on the very top of the roof. This he did while wearing no more than a pair of trousers and a coat that hung on him like drapes. A lone stick figure balanced on the ridge. Then a moment later, the giant came.”

“Not bounding over the hills, I take it?”

“No. He blocked the entirety of the lit window before he contorted himself out and climbed up after the man. His motion was a far more fluid thing, if likewise strange in how he placed his limbs. Were my eyes a little poorer, I might have mistaken him for some massive panther scaling a mountainside. But he was human enough seen from my seat. Just outlandish in his size and proportions. A hulking figure, yet corded and angled in a way you seldom see with men we might take for a contemporary Goliath.”

“I see. And what happened when he reached David?”

“The moon ducked out of sight for the first moment. It took a minute before it peeked through again to offer a silhouette of the meeting. Man and giant were facing each other with the giant seeming the most animated of the two. He gesticulated first with frantic violence, then as if he were beckoning the man like a stray from a gutter, and ultimately coaxed his frailer counterpart to extend a twig of an arm. The giant clamped onto it and seemed prepared to yank the man from his perch. But the man pointed with his free hand at the moon. This made the giant pause. The boulder of a head turned up. They stared together at the great ivory ball. But sense eventually overruled wonder and the giant maneuvered them both back in the window. The curtains were drawn. I figured that was the end of it.”

Dyson had by now fully dressed and packed for the day. He paused to raise a brow.

“Was it not?”

“No. Some while later, a light glowed in a lower window. David and Goliath walked outside. At least I assume it was David with Goliath. The spindly figure was erased in a massive clot of coats and blankets, it seemed, and so almost passed for a full-bodied individual. The giant shadowed him and forced a cup on him that I imagined must be steaming as it rose and fell from the man’s face. The moon was polite enough to show itself a few more times through the filmier clouds. Even the stars made some appearances. By dawn much of the clouds had broken up so that they skimmed across a half-clean sky. I saw the Morning Star hover in the horizon. The man pointed to this or the molten sunrise. The giant nodded and looked with him, patient as anything. Then David was herded back inside and I saw no more.”

Dyson hummed at all this and eyed the little house again. It really was a fair space away.

“Are you certain you saw a man and a giant? At this distance could it not have been some fevered child and his father?”

“If I were using my eyes alone, I might concede the possibility. Except.” Dyson watched him dig in his coat and produce a collapsed spyglass. “I have brought the full accoutrement of the hermit along, my friend. Its details were few, but far crisper than our sight alone.” A specter of mingled thrill and discomfort twitched along his lips. The former won just enough to pin the mouth up at one corner. “Though I wonder if that was a mistake.”

“Afraid they spied your spying? The threadbare David sounds like a stargazer. Perhaps he swung his lens around to find you in the dark.” Dyson spoke only to rib him. Instead he seemed to strike Ambrose like a lead weight. A greyish tinge passed in and out of his face as his gaze flicked back to the window. “Come now, there was no light on in here. Even if the pair had an astronomer’s lens between them, they’d never know you’d spotted their nocturnal theatre.”

“They had no lens at all,” Ambrose said. His lips still held in the unhappy upward curl. “Yet they did turn to look at this window. David first. Then Goliath. I cannot say whether they saw me, but…” Ambrose rolled the spyglass in his hand before replacing it in its pocket. “I saw a hint of their faces. Just the eyes. I may have imagined it. Some illusion of moonlight or sunrise. But the illusion was very crisp.”

“The illusion being what?”

“They were yellow, Dyson,” he almost chuckled. “Like the stare of animals caught in firelight. Bright as the lamps. And they did not turn from their staring in this direction until after I set the spyglass down.” Ambrose looked up at him. The whites of the man’s own eyes had gone rose-pink. “We’ve not yet set foot on Geber’s ash pile and already I have something for my notes.”

“Perhaps,” Dyson nodded carefully. “Perhaps you do. Or else a late night played on your conscience and sharpened your subjects into things that could chide you at a distance for spying. I have no such conscience on that subject and so might have missed their flashing eyes. Still, it is something for the diary. But only after breakfast.”

2

Dead, Buried

Breakfast came, breakfast went. Ambrose’s state barely loosened from its troubled knot. By the time they set out to poke around the week-old ruin under a dusting of snow, Dyson noted only a half-return to the man’s usual ease. He thought to remind him of the unhappy adventure involving the cruelly departed Agnes Black, to commiserate over the difference between the aftermath of the strange compared to meeting eyes with it, but swallowed it all down. Such talk would only rip up the scab, not plaster it.

In this mood, they took their way to the housefire’s wreckage with thin conversation. It only thickened again as the coach let them out at the site’s gates. They had been locked over again by the authorities and yesterday’s powder had made the surprisingly tidy mound and its rooftop cap into an anonymous lump of debris. Hardly worth the trip. But the sight of the ruin was only a fraction of their purpose there.

Dyson instructed the coachman to return in an hour to the same spot to retrieve them. The coachman eyed the two warily. He’d no doubt seen more than his fair helping of journalists and policemen in the past seven days than any soul ought to deal with. But pay was pay and he seemed content to reappear in roughly an hour’s time, sirs, give or take another customer’s route. Dyson and Ambrose waited until the horse-drawn speck was almost out of sight before they began their march around the the high stone wall that passed for the ex-manor’s fence. Their breath trailed after them in white streams.

“He really had the place made up like a fortress, didn’t he?” Dyson observed. “Look here. Even the ornaments along the top are like spires. No one could go hopping in or out without undoing the seams of his skin in the attempt.”

“Project Erichtho was a thing to covet as much as conjure.” Ambrose dug again in his coat, this time bringing out his notepad. He thumbed to one close-scribbled page. “Do you know, this manor was his for less than a decade? He took the place seven years ago and left behind a far more metropolitan estate. A handsome spot, but not half so private or titanic as this.” Ambrose knocked his knuckles against the stonework.

Dyson knocked his shoulder in turn, “I see you go a-haunting places other than your home while our backs are turned. You are a fraud of a recluse.”

“On special occasions, yes.”

“And the timeline of Geber’s road to the freakish blaze meets your standards.”

“Very much so. You see, he had his career in the city, for all its lauded highs and scandalous lows. And his one trip out of that area was also his first and last trip out of the country. I was told he took a holiday up to Switzerland.”

“Told by who?”

“Former staff. All the ones in the manor were local hands. The original workers say he returned home from his holiday with a wild new passion—,” Ambrose paused to catch Dyson’s eye, “—and a souvenir. One that they never saw removed from its massive box. The nearest guess anyone could make was that it must be one of those majestic Swiss clocks or perhaps some statue bought on a whim. None would it put it past him to purchase a likeness of his spiritual muse, or maybe a rendering of the latter’s infamous creation. But no one ever saw the contents in person. He had this thing moved into his upstairs laboratory, locked the door, and neither butler nor maid was permitted to set foot in the room for the rest of the year.”

“Mysterious enough,” Dyson agreed while shaking a snow clump off his boot. “Though I can hardly picture Switzerland as possessing any equivalent to Pandora’s Box.”

“Nor could the staff. But they never did wring an answer from Geber. No more than they ever confirmed what all his latest experiments were in that locked room. Whatever they were, the staff thought there must have been some noise to muffle. Geber started playing his phonograph whenever he set foot inside, letting the opera warble over whatever din went on in his work.” Ambrose tucked the notepad away and tugged at his glove. “When it came time for his sudden exodus to the far-off manor, the movers discovered the box was nailed shut again, offering no one even a parting peek at the treasure.”

“And what is the import of this crate, exactly?” Dyson asked, even as he guessed. It was hard to avoid, keeping his steps aligned with Ambrose’s as they circled to the rear of the estate. The trees loomed with their snowy crowns sawing against the blue-white sky. They were close to where the acreage sloped into woodlands.

“None of the new staff mentioned its arrival or its being toted down with the rest of Project Erichtho’s flotsam. In fairness, the interviewed parties likely had far more on their minds than the exact nature of their employer’s bric-a-brac. Especially when the project appears to have begun in earnest four years ago.”

“But,” Dyson intercepted, “the staff in the city dwelling remembered his fixation with the thing seven years prior. And if the manor’s fresher workers could remember that his other scientific oddments were loaded underground, surely they’d recall him fussing about the box.”

“Such is my guess,” nodded Ambrose. He stopped them both short as the exact back end of the stone wall came into view. “Geber likely would’ve clung like a shadow to the movers whether they brought it by the inner stairs or through the back entry. Yet there was no mention of it in their accounts. Almost as if he couldn’t bear to have more eyes upon it than absolutely necessary. And, naturally, there is the issue no other paper or ponderer has mentioned regarding the novelty of a subterranean workplace.” Here, at last, Ambrose began to grin. “One that even the miner or a digger of catacombs needn’t bother themselves over.”

“Because the men in the mines and catacombs don’t have to work within a hermetic seal,” Dyson concluded, beaming back. “They have a way constantly open to the air. The staff claim that the entryways into the laboratory were always shut and guarded by a boredly vigilant set of guards. A tricky area to provide ventilation for with no opening. Unless there was a third threshold somewhere that Geber neglected to mention to the house staff. Say,” he waved a glove at the waiting woods, “hidden in some convenient cover of wilderness.”

“It’s where I would hide a second backdoor in his position,” Ambrose agreed as he ogled the rear of the stone wall and the adjacent trees. “If the back of the manor was here,” he marched with measured steps to the back gate, likewise locked, and regarded the ashes beyond the iron, “then the broader outdoor entrance was likely slotted there with it. A tunnel connected to the underground work area would not be situated far off. So…” He turned and traced an invisible line from the ashes to the woods and away to the west. “A straight route from here on is likely to bear fruit.”

“Would it not be simpler to circle around?” Dyson asked this of the waiting trees as much as his friend. “If Geber’s precious crate was also moved in by this hidden corridor, surely it would be someplace near the edge of this tangled patch. It’s no narrow copse, but I’d rather amble around it rather than risk the trudge inside.”

“Normally I would agree. However.” Ambrose stomped purposefully along the slope, leaving clear tracks as he went. “If we want better odds against our own amateur detective work being spied on, we must take advantage of what little cover we can. Salisbury would tell you so.”

“Salisbury would be down with a skull-cracking headache over the prospect from any angle,” Dyson countered. But they went through the woods just the same. The snow had come in lightly through the coniferous canopy and it traded their softer snow-plush tracks for a brittle thudding along frozen earth. A quarter of an hour’s search and a number of brambles later they came upon a clearing cluttered with large stones. Dyson felt Ambrose bristle at his side. Not from the cold.

He had read the precious and painful little green book Ambrose regarded as one of his truest treasures. The book that contained the child-ramblings of a lost girl, of strange white figures, of stones carved and twisting with ancient unholy influence. Mercifully, the mystique was soon spoiled.

The clearing had let in a little more of the snow through the gap in the canopy and when the powder was brushed aside it revealed nothing but moss and bird droppings on every rock. Another glance showed a number of stunted logs also strewn about. A makeshift sitting area. Ambrose took a spot on one of the logs and set to picking burrs from his trousers. Dyson thought he looked a little ruddier for having seen the rocks were plain.

“Well, convenience dictates that a secret entrance would be around here.” He pointed to what would be a few minutes’ walk to where the open light of a meadow waited. “Any closer to the edge and it wouldn’t be hidden at all.”

“True, true,” Ambrose nodded, removing his hat to shake off the frost and pine needles. “But even if we were on top of the thing, there’d be the second trouble of spotting it while it’s disguised. There was likely one or more guards on duty. On the off-chance that some wanderer came by they’d need to have some way to mask the opening.”

Dyson thought as much too and had been scrutinizing the ground. He’d found a good stick to claw up the dirt with. So far, no convenient trapdoor presented itself. As he prodded, he caught himself mulling over the hypothetical guards themselves. Surely they couldn’t have been caught in the blaze. Even if they’d been struck by a heroic urge, there wouldn’t have been time to rush to the manor and attempt a rescue. Yet he recalled no interview with any such person in the aftermath of the pyre, only those domestic staff who minded the house itself. So where had they gone?

The answer was hidden under a rock.

Specifically, the largest of the rocks in the clearing. Dyson’s stick came to a stop in its shadow as the branch suddenly dipped an inch into the ground where he’d dragged it. The snowfall masked it, but not well enough.

“Ambrose.” He patted the broad rock. “This stone isn’t supposed to be here.”

“What?”

“Look here.” He dragged his stick back and forth over the hidden groove beneath the powder. “It was moved out of place.”

Dyson and Ambrose eyed this only a moment before taking position on the stone’s opposite side. Together, after many a shove and as many curses, the rock budged. Not all at once, but in bursts. Between lurches they agreed that it had to have been put in place by far stouter strongmen than themselves. Their thoughts broke away at the same time when their next push dropped a leg from each of them down into the earth. There was much floundering and flopping aside to save themselves from slipping entirely into the hollow. When they’d recovered themselves, they peered down into the new opening. A wisp of daylight revealed hints of the interior. Shards of wood. The angles of a short staircase. And there, laying at the foot of the steps—

“Oh,” Dyson breathed. “Oh, God.”

“I fear He isn’t involved here,” Ambrose murmured back.

They lurched the stone the rest of the way, moving with caution until the entire hole was revealed. A square of earth had been cut away for the tunnel’s mouth. A set of heavy mangled hinges showed where a crude but sturdy door had been bolted into place. The door itself was the source of the wood shards, the largest of them showing they’d had a covering of dirt, leaves, twigs, and pebbles all pasted on to mask it. To judge by the frame, the door was meant to be pulled up rather than pushed in. As the stone was flat on the bottom, it could only be surmised that someone had smashed the timber in rather than bother with the lock.

Perhaps that was why the guards had died. They hadn’t been quick enough to offer a key.

Two men of powerful build were left crumpled at the bottom of the steps like ragdolls. One had his head wrenched entirely around on his shoulders. The other had his head crushed in like an eggshell. Whoever had done the work, they’d also seen fit to strip the broken-necked man of all but his underclothes, even down to his shoes. The man with the pulped skull had lost only a coat.

“I believe this is where our investigative ghost story hits a snag,” Dyson said, if only because someone needed to speak. The words did little to settle the chill now twining up his back. “We need to have the police up here.”

“We will,” Ambrose said, digging in his coat. Out came his matches. “But first.” He struck a light. “Recall that we are not here in search of ghosts. Ghosts are vapor. Their only weight is given to them by the storytelling.” He flicked the match into the tunnel so that it soared over the corpses. Dyson followed its glow with wide eyes. “Whereas the party responsible here exists with or without fireside theatre.” Dyson was already inclined to believe him. The sight revealed by the match merely forged faith into knowledge.

On the night of the fire there had been a positive torrent to go with the thunder and lightning. Once the guards and door were brutalized out of commission and left broken on the tunnel steps, a river of mud had dribbled in after the intruder. In the carpet of now-dried muck were smeared remnants of footprints. Most were colossal and led two ways, going forward and back. Whoever had made them was large enough to dwarf the dead men. A second set of footprints tramped back with these first massive soles, the barefoot steps looking far closer to human dimensions.

Beyond these smeared prints and just out of reach of the match’s light was the outline of a wide cart.

“Spare another?” Ambrose passed Dyson the matches. Dyson descended and made a rush to the cart. A match struck and showed the contents was discarded linen tarps all mottled with stains dark as rust. In the very center of the rumpled sheets, pointing to him, was a single rotten human finger.

The match went out.

Dyson raced back up to the daylit earth and rattled off the find to Ambrose.

“It does line up. An experiment named after Erichtho could hardly earn the title without doing something unwholesome with corpses.” Ambrose inclined his head at the tunnel. “It’s certainly not the kind of material Geber would want the house staff spying on its way down to the lab.”

“I wonder about that.” Dyson righted himself and squinted up at the sun behind a veil of new clouds. “Who’s to say that the finger was already rotten when it lost its owner? Surely the towns would have something in the news about graverobbers pillaging their cemeteries for convenient goods.”

“True.” The word was small. Dyson looked to Ambrose as the man paused in jotting something in his notes. His gaze was suddenly very far, hooked on some unknown point in the trees. “Quite true. After all,” he slowly closed the notepad and tucked it away with gloves that trembled, “it’s only worthy of newsprint if the dead go missing. The living disappear every day.” Dyson watch his throat work strangely behind his scarf. His breath came in very brisk puffs. “Such is hardly worth a blink these days. What’s the time, Dyson?” Dyson checked his watch. They’d eaten up most of an hour and he said so. “Then we’d best head down to meet our coach. Now.”

“Should we replace the stone? What if some animal gets in and—,”

Ambrose seized his shoulder. His head still hadn’t turned away from the trees. His voice came out so low there was almost no breath to whiten.

“Dyson. Now. Quick, but—but do not run.” His Adam’s apple seemed about to leap up through his mouth. “Now.” Dyson tried to follow Ambrose’s line of sight, but his friend was already dragging him like an errant sheep. Rather than take their original route, Ambrose shepherded them towards the nearest edge of the woodlands, out to the open snow.

“What happened to discretion?” Dyson asked in his own low pitch. Ambrose shook his head without fully taking his gaze away from the abruptly-fascinating patch of trees.

“We’ll be bringing authorities around here anyway. It hardly matters. Go. Just go. Once we get out in the open, we should—,” Behind them, a heavy branch snapped. To Dyson’s ears it sounded loud as breaking bone. Ambrose’s clutching hand became a vise. “Run.”

They did.

The gloom behind them snapped and rustled in a straight line after their heels. More, the ground itself twitched with the bounding of some unthinkable weight. Dyson thought ludicrously of bears or lions somehow migrating their way to this mild crumb of Surrey’s landscape. Yet he heard no animal snarl. Only the unimpeded breaking of the trees’ quiet as something titanic loped after its quarries.

Ambrose and Dyson broke out into the open meadow after a minute that felt like half an hour. They raced across the slope and around toward the fenced-in ruin of the manor at a frantic pace. Relief barely flickered in them as they saw the coach trotting up to the front gates. Their own tread was too wild to register if their pursuer was still galloping after them, but Dyson now felt the presence of eyes on him as surely as he’d feel the trundling of beetles along his neck.

The dead men flashed in his mind. Twisted and mashed and tossed in a pit. There was plenty of room to spare down there. New tenants welcome. And the coachman was so far, so far—

He stepped on one of his own bootlaces and went sprawling. When he moved to catch himself on his hands, his palm landed on something slicker than the snow, fumbling him so that he landed with elbow and cheek in the frost. It really was a pitiful layer of powder, he noted as his arm and face throbbed against the stiff ground. Ambrose skidded to a halt with him, almost falling as he scrambled on the frost. He might have shouted Dyson’s name. Dyson couldn’t be sure as he was peeling up the thing his hand had slid with. A leatherbound book with its cover lacquered in congealed mud.

“Dyson,” he heard Ambrose puff again. His breath was labored, but no longer a shout. “Dyson, can you stand?” Dyson looked up to see Ambrose’s attention was split between him and the trees. Nothing else was behind them. Dyson fixed his laces and regained his feet without releasing the book. “I think we can go at an easier pace now.”

“Yes. Possibly.”

Their new gait was not a sprint, but still a fair way ahead of anything leisurely. The driver looked at them oddly as they jogged over, at least until they gave him pay and directions for a trip to the nearest police station. Then his caterpillar brows shot up.

“Come across some trouble up there?”

“The human trouble has been and gone,” Dyson told him. “But they may want hunting rifles at hand for whatever creatures are roaming around in there.” The driver snorted at that.

“What creatures are those? Worst we’ve got in these parts are the damned foxes and a few snakes. Biggest thing I’ve seen was a buck that ran around last year. Had antlers two men wide.”

“It was no deer,” Ambrose assured him even as he craned his head again to face the trees. Dyson saw him fondling the part of his coat that held the spyglass. “In any case, it is a matter that would be helped by having a marksman ready.” The driver got no more from them as Dyson and Ambrose bundled themselves inside the coach. Ambrose hastily fumbled out the spyglass and watched the woods through his window until the treetops were out of sight.

“Not a deer, you say,” Dyson spoke as much to his mud-crusted souvenir as to the back of Ambrose’s head. “What then? I had no time to catch a glimpse.” Ambrose let out a breath as he collapsed the spyglass, fidgeting with the cylinder rather than tucking it away.

“Speaking frankly, I didn’t either. All I could spot in the gloom was the flash of bright eyes.” His throat twitched. “A gleam of yellow.” Dyson paused in his picking at the shell of hardened mud.

“Last night’s Goliath?”

“I don’t know. I cannot say with certainty whether the eyes belonged to a human shape or a creature on its haunches. Only that it was still as a statue in the gloom back there. Staring at us.” Ambrose shivered either from memory or cold and tucked the spyglass away in favor of his notes. He sketched rather than wrote. Scrawled across a clean page was the impression of two huge coins floating in a scribbled ink-shadow. The eyes featured pupils of a distinctly non-human make. “I am no artist, but this is roughly the look I caught watching us. They turned in the dark when we started for the trees’ edge. Then the eyes came forward.” He clapped the notes shut. “I found I was far more eager to be out of reach than to wait and see the eyes’ owner.” Ambrose gave him a tired smile. “I feel I’m halfway to a hypocrite after this. True, there was no alley and no waiting cutthroat, but I did run from the unknown when it came running.”

“Nonsense,” Dyson huffed. “Those eyes no doubt belonged to some exotic beast that escaped its pen in a zoo or some fool’s private menagerie. Nice open country like this is just the place you’ll find people with deep coffers and shallow sense hoarding pretty predators as though they were collecting pedigree hounds and cats. You wait, we’ll see something in the papers about somebody’s missing leopard or tiger prowling around the hills. Now, if that beast had cleared its throat in the dark and shouted at us in plain English to get out of its woods, there might be grounds to point and go a-ha! But as it had nothing to say and neither of us was polite enough to stand still and get mauled, the matter remains unsettled. Say, have you got a handkerchief you don’t mind ruining?”

Ambrose handed him one, his face finally regaining some tint as he puzzled over Dyson’s prize.

“It would be an opportune thing to be in a ghost story,” he sighed while Dyson scraped at the mud. “If we are, that will turn out to be a conveniently abandoned diary illustrating every move Geber made leading up to the fire, replete with his devilish experiments and all the lost spirits it conjured up. At the very least it will contain the chemical formula that led to such a unique blaze.”

Dyson scoured away most of the muck and frowned.

“Not a diary. Not even a tome of unholy scripture.”

“No?”

Dyson held the book up for him to see. Ambrose frowned back at him.

“No.”

The book was a leatherbound copy of The Legend of Frankenstein. What had been a luxurious volume had apparently been mangled by elements, animals, or else someone with a distinct loathing of the tale. Dyson had wondered at the lightness of the book and found that much of the pages were either shredded or torn out entirely. The inner cover alone had been spared attack, though it still boasted a minor bit of vandalism within:

There are not words enough to voice proper gratitude to the Muse, the Master, the Miracle. For lifetimes to come, even the finest poets of the world shall struggle to meet the task. Here and now, the most that can be said is thank you. Thank you for all that you have done, all that you are, all that is yet to come. A toast to the teachings of Prometheus, to Prima Materia, to the Magnum Opus realized!

—R.G.

Below this, a single line:

Mortui vivos docent.

“The dead teach the living. Interesting choice of postscript.”

“That isn’t all of it.” Ambrose took back the handkerchief and chipped further at a smear of muck still gripping the cover. It crumbled away to show words that had been stained into the board with a different pen. Almost carved.

Prometheus had nothing to teach. He stole the lightning for Man’s fire. The only worthwhile lesson of his myth was taught by the Eagle.

Erichtho might have had teachings to spare. The gods were wise enough to harken to her and know to quail. Yet mortal men care only for the dead’s secrets and the boons they might grant. These you will have. May the knowledge serve you as well as it has me.

No initial or signature was jotted with it, though some rough symbol was gouged below. A thing that curved and went straight at once, vaguely serpentine and somehow unpleasant in both its shape and the depth of its coarse engraving. As though the artist had been both incapable of finesse and insistent on carving the image regardless. Dyson and Ambrose each had a good squint at it and decided it was something related to a caduceus, the sign of medicine.

“The alchemic variant seems just as likely, if we’re to chase Geber’s words to their logical end,” Ambrose said in a tone that heartened as much as frustrated Dyson to hear. It meant the man’s nerves were settling, but also that his mind was now wandering down avenues several leagues away from the present, no doubt combing an internal library of references. Dyson flattered himself to know that he too had some scraps of intel to turn over. He recognized the Magnum Opus as referring to a ‘Great Work’ just as prima materia was a term for a sort of primal matter from which life and the universe was meant to be concocted. But no more than that. He’d need to dust off some old books or wait for Ambrose’s own ramble before he could scrounge up any deeper details.

As it turned out, Ambrose had sealed himself up in his head for the moment.

A moment which lasted long enough to get within talking distance of the police. They described the tunnel and what was in it. There was scarcely time to stretch their legs before they were riding along with the uniformed men, each thankfully armed. Sunset was almost racing them to the horizon by the time they trudged back to the clearing with lanterns in hand. Both men froze upon discovering it. When asked why:

“We didn’t leave it like this,” Dyson heard himself croak.

“How so?”

“The stone. We left it pushed aside when we left. The tunnel was still uncovered.”

Now the boulder was planted right back where it had been.

A hasty examination was made for tell-tale shoe prints, to little avail. New snow was fluttering down and filling things in with an accomplice’s speed. Giving it up, the group of them carefully shouldered the rock aside. Their caution’s reward was a column of acrid smoke that wafted up and plugged every unfortunate nose in reach. The last embers of a fire were dying down inside the tunnel.

The two corpses were roasted. The cart was a cinder. The tunnel’s floor had been glazed with oil and set alight until the whole bottom of the chute was a long black stream at least halfway to the underground entry point of the manor. Investigation to that farthest end revealed a pair of melted metal doors with burst windows. Beyond them there was only packed-in ash.

Dyson made no more mention of his hypothetical escaped animal.

Ambrose was not only silent about the Goliath seen from the window, but went so far as to draw his curtains before bed.

#Was Frankenstein Not the Monster?#frankenstein#mary shelley#arthur machen#the inmost light#the red hand#my writing#horror#hope you guys dig it#my art

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A gothic literature hyperfixation has possessed me so I made this

(This took way longer to make than it reasonably should have)

#gothic literature#classic lit#gothic lit meme#gothic lit art#classic literature#frankenstein#victor frankenstein#the strange case of dr jekyll and mr hyde#edward hyde#henry jekyll#henry wotton#the picture of dorian gray#dracula#lucy westenra#gabriel john utterson#mr utterson#jekyll and hyde#dr jekyll and mr hyde#henry clerval#mary shelley#bram stoker#robert louis stevenson#oscar wilde#art#the creature#frankensteins monster

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

watched a lot of movies this week with franken ppl & I felt like putting them together like this was my mission

#frankie stein#monster high#monster high frankie#lisa frankenstein#frankenstein#frankenstein monster#hotel transylvania#😭

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

happy halloween!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Monsters are a Ghoul’s Best Friend 💕

IG: Battydeville

#my art#artists on tumblr#illustration#battydeville#digital art#pinup#pinup art#50s pinup#vintage aesthetic#classic monsters#classic movies#universal monsters#creature from the black lagoon#gill man#dracula#bela lugosi#frankenstein#the invisible man#nosferatu#the wolf man#horror pinup#vintage art#horror#classic horror#diamonds are a girls best friend#marilyn monroe#count orlok

4K notes

·

View notes